Abstract

Introduction

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC) has proven to be effective in other patient groups, but the effectiveness in girls with Turner syndrome (TS) is still unclear. Guidelines for counselling about OTC in TS are lacking. The aim of this study was to gain insight into the experiences of patients, parents, and healthcare providers with the decision-making process regarding OTC in girls with TS.

Methods

Within a year after counselling, a survey was sent to 132 girls with TS and their parents. Furthermore, focus groups were conducted with (1) gynaecologists with subspeciality reproductive medicine, (2) paediatric endocrinologists, (3) parents of girls aged 2–12, and (4) parents of girls aged 13–18. Transcripts were analysed using a thematic analysis approach.

Results

The response rate of the survey was 45%. Of the survey respondents, 90% appreciated counselling regarding their future parenting options and considered it an addition to existing healthcare. Girls with TS and their parents indicated that the option of OTC raised hope for future genetic offspring and instantly made them feel that their only option was to seize this opportunity. Gynaecologists and paediatricians found it challenging to truly make families grasp a realistic perspective of OTC in girls with TS.

Discussion and Conclusion

Offering young girls with TS the possibility of fertility preservation in an experimental setting raised high hopes and led to challenges for healthcare providers in ensuring a considered decision. The appropriate moment for counselling should be tailored to the individual and discussed with patient, parents, and paediatrician.

Keywords: Turner syndrome, Decision-making, Ovarian tissue cryopreservation, Counselling, Fertility preservation

Introduction

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC) is increasingly used in medical care for women facing iatrogenic premature ovarian insufficiency, such as patients awaiting fertility-threatening chemo- or radiation therapy [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Autologous transplantation of ovarian tissue after OTC has proven to be effective in restoring fertility, with a life birth rate of 30.6% and more than 200 live births reported [6]. Currently, OTC is also offered in a research setting to patients with a genetic cause of premature ovarian insufficiency, including girls with Turner syndrome (TS) [7, 8, 9]. TS is a condition that affects 1 in 2,500 live-born girls [10]. In TS, one of the sex chromosomes is (partially) missing or rearranged, leading to gonadal dysgenesis or a rapid decline of the ovarian reserve. Some girls with TS are born with complete exhaustion of their ovarian follicles, while others show a more gradual depletion. Pubertal development is often hampered, and spontaneous pregnancies in women with TS are rare (2.0–7.6%) [10, 11, 12, 13]. Infertility is a major concern of girls with TS and their parents [14], and the desire for new options to increase the odds of having genetic offspring is evident [15]. The only current option to preserve fertility for girls with TS is oocyte preservation; however, this option requires a menstrual cycle and sexual maturity [16]. Although OTC is considered experimental for girls with TS [9, 17, 18, 19], this fertility preservation technique could be an option for prepubescent girls with TS [5, 8, 20].

However, healthcare providers and scientists are still reluctant to offer OTC to girls with TS, since it requires an invasive surgical procedure without clear predictors of whether primordial follicles will actually be found [7, 15]. At the same time, there is uncertainty about the developmental capacity of the preserved ovarian tissue [15, 21]. Moreover, women with TS have a higher incidence of miscarriages and severe pregnancy complications, such as preeclampsia and aortic dissection [8, 10, 22]. With the exception of severe aortic dilatation, cardiac malformations are not an absolute contraindication for pregnancy in women with TS according to the international guidelines [16]. Nevertheless, girls with TS would appreciate further research on whether OTC could be a valid option for them [15].

A multidisciplinary expert panel supported the use of OTC for girls with TS on condition that it is offered in a safe, controlled study setting with adequate counselling and shared decision-making [23]. The panel emphasized that three items were important during the counselling process of girls with TS: (1) a dedicated multidisciplinary team, (2) active involvement of girls, regardless of their age, and (3) to discuss alternative options for future parenthood. Even though international guidelines recommend that girls with TS should be counselled about fertility and fertility preservation [16], it appeared that only 9–10% of girls are actually referred to a fertility specialist [14, 24, 25]. Although it has not yet been studied in girls with TS, several studies in children and adults facing gonadotoxic treatments have reported about counselling regarding OTC and showed that it ensures less decision regret and a feeling of being in control [2, 26]. In certain respects, there is a similarity between girls with TS and girls that undergo gonadotoxic treatments: both have a high likelihood on infertility, and both are often too young to decide or co-decide about fertility preservation, for psychological as well as legal reasons [2, 5, 26, 27, 28]. This poses challenges when counselling girls regarding OTC.

The efficacy of OTC in girls with TS aged 2–18 years is currently being investigated in the TurnerFertility study at Radboudumc in the Netherlands (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03381300) [9]. We noticed that the counselling as well as decision-making was a challenge for girls with TS, parents, and healthcare providers. This led to the initiative for the current study, which aimed to evaluate the decision-making process regarding OTC during the TurnerFertility study. Its central question was as follows: what are the experiences of patients, parents, and healthcare providers with the decision-making process regarding OTC in girls with TS?

Methods

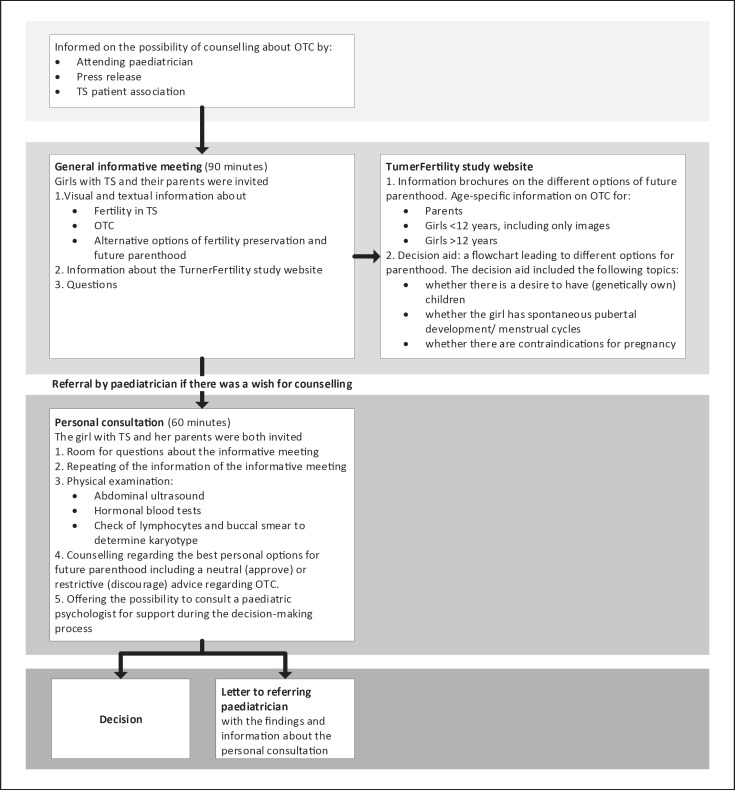

This mixed-method, interpretivist study is a sub-study of a prospective intervention study, the TurnerFertility study [9]. Prior to participation in the TurnerFertility study, girls with TS and their parents were counselled about OTC and other options for future parenthood. Since there were no evidence-based parameters for finding oocytes, all girls with TS could be included in the TurnerFertility study. Counselling consisted of a general informative meeting and a personal consultation. Information about TS, options of future parenthood, and a decision aid was available on our website. More details on the counselling process are shown in Figure 1. To gain insight into the experiences with the decision-making process, families received a survey one year after counselling. In addition, four focus group interviews were conducted. The study was designed by the TurnerFertility team, which consisted of two gynaecologists with subspeciality reproductive medicine, a paediatric endocrinologist, a biologist with subspeciality in reproductive medicine, a medical ethicist, and three PhD candidates who also worked as physicians in reproductive medicine.

Fig. 1.

A flowchart on the counselling process regarding OTC in girls with TS.

Survey

Between January 2018 and January 2019, 132 girls and their parents visited one of the informative meetings and individual consultations about the TurnerFertility study. Of these families, 79 opted for OTC. All 132 families received a survey (additional file 1) by mail. The survey was addressed to the parents if the patient was under 12 years of age, to the patient and their parents if the patient was between 12 and 16 years old, and only to the patient when they were 16 years or older.

Survey questions were developed in multiple rounds by the TurnerFertility team. Survey questions were based on experiences of the TurnerFertility team and research regarding decision-making in children [2, 5, 8, 18]. The survey included both closed (n = 17) and open questions (n = 13) about demographics and experiences with the different counselling phases. Survey answers were linked to data from the electronic patient file (e.g., current age, age at diagnosis, karyotype of lymphocytes, educational level, and medical history) and subsequently pseudonymized.

Focus Groups

A total of four focus groups took place. Focus group 1 (FG1) included four gynaecologists with subspeciality reproductive medicine and one physician in reproductive medicine. In the remainder of this manuscript, we will refer to them as “gynaecologists.” Three of these gynaecologists were part of the TurnerFertility team and were not only counsellors, but also performed the surgery and informed families whether oocytes were found in the ovarian tissue. Participants of FG1 were selected using purposive sampling, considering their different opinions about the TurnerFertility study. Focus group 2 (FG2) included five paediatric endocrinologists and two paediatricians with experience in care for girls with TS. In the remainder of this manuscript, we will refer to them as “paediatricians.” None of these paediatricians were a member of the TurnerFertility team. All paediatricians had referred girls with TS for counselling for the TurnerFertility study. The paediatric psychologist involved was interviewed individually. Participants of FG2 were selected using convenience sampling. Focus group 3 (FG3) consisted of parents of girls with TS between the ages of 2 and 12 and focus group 4 (FG4) of parents of girls with TS between the ages of 13 and 18. Families could indicate in the survey whether they wanted to be approached for a focus group. Participants of FG3 and FG4 were selected using purposive sampling to ensure a diverse group based on age, level of education, and different decisions made about OTC. No incentives were offered for participation. Initially, a fifth focus group was planned with girls with TS between the ages of 15 and 18. However, only three girls agreed to participate in FG5, and therefore, this focus group was cancelled.

Focus group guides were designed by A.O. and S.C. and critically reviewed by the TurnerFertility team. Questions were based on survey results, literature, and experiences of the TurnerFertility team. The questions contained domains about information and counselling, about how the decision was influenced, about emotions and feelings, and about the daughter's involvement. Questions were designed to elicit a discussion among participants. All focus group interviews were conducted by an experienced moderator (A.O.) and assisted by an observer (S.C.) taking field notes. The moderator and observer were not involved in the care for the girls with TS.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data of the survey were collected in Castor EDC (V.1.4.1) and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V. 22.0, Armonk, NY, USA). The audio recordings of the focus group interviews were transcribed verbatim, and the transcripts were subsequently anonymized. The transcripts of the open survey questions and focus group interviews were analysed using qualitative research software ATLAS.ti (v8.2, Berlin). The transcripts were independently coded by two researchers (S.C. and A.O.) using a thematic analysis approach [29]. Firstly, transcripts were coded with words used by the participants (open coding), after which these codes were grouped into subthemes using axial coding. These subthemes were regularly discussed and merged into broader themes in consultation with the TurnerFertility team. More details about the methods used in this study can be found in the COREQ checklist in additional file 2 [30].

Results

Of the 132 surveys sent, 60 were returned. A flowchart of survey respondents can be found in additional file 3. Family characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of the respondents, 45 families (75%) opted for OTC. Of the responding parents, 57% were highly educated and 18% had undergone assisted reproductive technology themselves. The results with regard to the experiences with the counselling are summarized in Table 2. Most families (64%) had been informed by their paediatrician about the TurnerFertility study and the possibility of in-depth counselling regarding future parenthood. The majority (90%) felt that counselling contributed (substantially) to the existing care for girls with TS. 66% of respondents felt that the individual consultation contributed most.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants of the survey, FG3 and FG4

| Variable | Survey, n (%) |

FG3, n (%) |

FG4, n (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 60 | n = 9 | n = 3 | ||||

| Characteristics girls | ||||||

| Final decision | ||||||

| OTC | 45 | (75) | 7 | (78) | 2 | (67) |

| Expectative | 3 | (5) | 1 | (11) | ||

| Not decided | 5 | (8) | 1 | (33) | ||

| Other* | 7 | (12) | 1 | (11) | ||

| Age in years | ||||||

| 0–6 | 13 | (22) | 2 | (22) | ||

| 7–12 | 20 | (33) | 7 | (88) | ||

| 13–15 | 18 | (30) | 1 | (33) | ||

| 16–18 | 9 | (15) | 2 | (67) | ||

| Years since diagnosis | ||||||

| ≤3 | 21 | (35) | ||||

| >3 | 39 | (65) | ||||

| Karyotype monosomy | 25 | (42) | 3 | (33) | 1 | (33) |

| Characteristics parents | ||||||

| Highest level of education | ||||||

| Unknown | 3 | (3) | ||||

| Elementary school | 10 | (8) | ||||

| Preparatory secondary vocational education | 6 | (5) | 1 | (11) | ||

| Secondary vocational education | 33 | (28) | 3 | (33) | 1 | (33) |

| Higher professional education | 43 | (36) | 3 | (33) | 1 | (33) |

| University education | 25 | (21) | 2 | (22) | 1 | (33) |

| Fertility problems | 11 | (18) | ||||

FG3, focus group 3, parents of girls with TS between 2 and 12 years; FG4, focus group 4, parents of girls with TS between 13 and 18 years.

Adoption, foster care, surrogacy, gamete donation.

Table 2.

Survey results: experiences with counselling (n = 59)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| General impression of counselling | |

| Very contributing | 19 (32) |

| Contributing | 34 (58) |

| Neutral | 4 (7) |

| Little contributing | 2 (3) |

| Most contributing to decision* | |

| Individual consultation | 39 (66) |

| Informative meeting | 22 (37) |

| Decision aid | 2 (3) |

| Informed about counselling by (n = 58)* | |

| Paediatrician | 37 (64) |

| Item national news | 15 (26) |

| TS patient association | 8 (14) |

| Other** | 11 (19) |

Some respondents checked multiple options.

Website Radboudumc, social media.

All of the invited gynaecologists (5) and paediatricians (7) participated in FG1 and FG2, respectively. About half of the survey respondents (48%) were willing to participate in a focus group interview. FG3 included 6 mothers and 3 fathers of 7 girls (3–12 years old). FG4 included 3 mothers of 3 girls (14–17 years old). 4 other parents cancelled due to illness (2) and family circumstances (2). Of all participating parents in FG3 and FG4, 4 daughters had undergone the surgical procedure, 3 were on the waiting list, 2 had opted not to undergo OTC, and 1 was undecided. The remaining participant characteristics of FG3 and FG4 are shown in Table 1.

Qualitative Results

Results of the open survey questions and the focus group interviews were labelled with 95 different codes. Subsequently, seven broad themes emerged from the analysis: information, motivation, importance of counselling, influencing factors, family characteristics that influence counselling, strengths of counselling, and weaknesses of counselling. All major themes are discussed below from the perspectives of girls, parents, and healthcare providers.

Perspective of Girls and Parents

All focus group participants stated that they had received sufficient information to make an informed decision. They highly valued the individual consultation, during which they were able to ask personal questions. In addition, participants were provided with information of the informative meeting for a second time. Most focus group participants mentioned that they had not consulted the information on the TurnerFertility study website, since they had already received enough information during the individual consultation and informative meeting, or had already made a decision. Parents indicated that they wanted to be informed about the odds and possible outcome of OTC, and that they would like to have an estimation of their daughter's ovarian function and its decline. Besides, they requested information about the surgical procedure, including anaesthesia, duration of hospitalization, recovery, and follow-up after surgery. Parents mentioned that their decision-making was complicated by a variety of uncertainties and that they asked themselves several questions, including will oocytes be present, what is the quality of the oocytes, will the tissue remain viable after thawing and transplantation, and what would the natural course be if we do not opt for OTC?

Both parents and girls appreciated the TurnerFertility study for the attempt to preserve fertility. The option of undergoing OTC procedure for fertility preservation increased hope for future offspring and provides clarity regarding the ovarian reserve. Opting for OTC gave them the feeling that they had exhausted every option, a feeling of control. Many indicated that the odds of success did not influence the decision, since the odds of genetic offspring had previously been nil. As one mother described it:

“There is a possibility […] and you really want to seize any possibility with both hands.” [FG3 − Mother of 11-year-old girl]

Therefore, parents indicated that it did not feel as if they had to make an actual choice. They felt that the rapid decline of the ovarian reserve was inevitable, and that they now had a chance to preserve the fertility. A secondary motive to participate was that they contributed to scientific knowledge about TS in this way. Moreover, some participants indicated that they hoped that future scientific developments might make it possible to use the frozen tissue in other ways, such as in vitro maturation of oocytes.

The girls and their parents who ultimately decided not to have OTC performed cited the invasiveness of the procedure and the small chance of pregnancy as their main argument. Another reason for not participating in the TurnerFertility study was the fact that OTC would bring infertility back to the forefront. Some parents felt that this emotionally charged topic was too confronting.

“It's also a kind of grieving process you go through. A future that won't be. It sounds a bit heavy maybe, but that's how I experienced it. And then all of a sudden it's like ‘oh something new could happen.’” [FG4 − Mother of 17-year-old girl]

Parents indicated that their decision was based as much as possible on their daughter's opinion. Parents of older girls stressed the importance of active involvement of their daughter in the individual consultation. Nevertheless, several parents were concerned about their daughter's decision to refrain from OTC out of fear for the procedure, while at the same time they were unable to oversee the long-term consequences of this decision. In addition, parents of girls younger than 12 felt that their daughters were too young to decide, and that they had to make the decision for their daughters. Some parents were afraid that they might at a later stage regret their decision to decline OTC. As one father said:

“My child is 10, and I think when she turns 18, I do not want her to have to say to me, ‘why didn't you do this?’ […] so, do you really have a choice? I don't think so.” [FG3 − Father of 10-year-old girl]

Most parents attended the informative meeting and personal consultation together with their daughter. During the personal consultation, some families were strongly advised not to subject their daughter to OTC or a future pregnancy because of medical reasons. Therefore, some of those parents would have preferred an individual consultation without their daughter present before involving her, since that could have prevented their daughter from getting false hope. As one girl with TS described it:

“I found it difficult to talk about it, I had been told that becoming pregnant myself is not an option. This study gave me a little hope, but it was for nothing.” [Survey − 13-year-old girl]

Finally, the focus group interviews and the survey revealed that some parents and some older girls felt time pressure because of the limited number of study participants and the feeling that they were running out of ovarian reserve.

Perspective of Healthcare Providers

All healthcare providers considered it essential that families were thoroughly counselled about the (dis)advantages of participation in the TurnerFertility study, the physical and psychological risks, the alternative options for future parenthood, and the differences between standard care and participation in the TurnerFertility study. As mentioned by gynaecologists, some families had never thought about the different options for parenthood and had “just accepted” the infertility. One paediatrician struggled with the extent to which she/he had to inform families about possible complications and the postoperative course, such as the risk of menopausal symptoms. Gynaecologists and paediatricians had difficulty finding the right balance between preventing undue anxiety and providing the necessary information:

“It remains an invasive procedure, and it might not have any effect […] with a risk of complications. I noticed that I emphasized this to people whose […] chances were much smaller to start with, that I would point that out to them very clearly. That it remains an intervention that might not change anything.” [FG1 − Gynaecologist 1]

Gynaecologists described that their manner of counselling depended on various factors, such as age, karyotype, and endocrine markers of the girl, but also on social factors such as parental education level and the family's preparation for the consultation. Gynaecologists felt that many families had high hopes and that it was of major importance to temper those expectations in order to enable them to make a deliberate decision. According to healthcare providers, counselling should provide families with a realistic perspective.

“Because people come here so focused on with the hope that this will solve everything or that they might clutch at last straws that will cause something to change.” [FG1 − Gynaecologist 5]

The paediatric psychologist indicated that it is important to emphasize that postponing the decision is also one of the options. Instead of refusing OTC, the daughter can wait until she is older to participate in the decision. Even before the informative meeting took place, some families were very determined in their decision for OTC. Gynaecologists had a hard time presenting these families with both perspectives and explaining to them what the negative aspects are.

“I think it's difficult for most parents to decide not to give it a try. Because they feel that they should take this chance. No matter how small. So, when children are younger, and their parents make the decision, I notice that a lot of parents want to have given it a try at least, so to speak.” [FG2 − Paediatrician 4]

Some healthcare providers worried that the study would lead to unnecessary harm and psychological stress in cases where it was almost clear from the beginning that the odds of finding oocytes were close to zero. At the same time, they understood the need for more scientific knowledge to identify parameters to predict the presence of follicles in girls with TS. Gynaecologists and paediatricians indicated that they had difficulty with offering hope to families that had already accepted the fact that having genetic offspring was not possible and then having to take that hope away again in case no oocytes were found during the procedure. As one gynaecologist said:

“What bothers me most is the psychological part, so there are girls and families that have come to terms with the idea of, well, ‘they won't conceive naturally’ and these families have also communicated that to their child. And now that idea has to be reversed. Because otherwise you have no reason to do surgery. And then, for the most part, you have to deal that blow again. ‘It really is not going to happen.’ By then they have already done a lot of processing and you are bringing it all up again and then squashing all hope again. I find that quite difficult.” [FG1 − Gynaecologist 3].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first mixed-method study that gives insight into the experiences of patients, parents, and healthcare providers with the decision-making process regarding OTC in girls with TS. Our results underline that counselling for OTC and options for future parenthood were highly valuated by girls with TS and their parents. Undergoing the process of counselling for OTC creates hope, but it also gives many patients a feeling that they have no other choice. For healthcare providers, guidance of families is challenging because expectations have to be placed in the right perspective to make a considered decision.

New medical technologies may have an imperative character: their availability creates the desire to use them [27, 31]. This also holds true for the TurnerFertility study: many families indicated that this new option raised hope for future genetic offspring and immediately gave them the feeling that they had no other option than to seize this opportunity. The desire to have exhausted every possible option outweighs the uncertain outcome and potential burden of the intervention. Furthermore, the responsibility for this decision about an invasive procedure largely rests with the parents. In some parents' stories, we recognized anticipated decision regret as an important motivation to participate [32]: acting out of a desire to avoid future regret or even being blamed by their daughter for not having participated in the TurnerFertility study when they had the chance.

These mechanisms posed challenges during counselling of families for the healthcare providers in our study. Making a considered decision about study participation requires being fully informed and being able to understand the consequences of the decision, including the possible risks of anaesthesia and pregnancy in later life, especially in the case of cardiac comorbidities [10]. Healthcare providers counselled families, while the effectiveness of OTC in TS still remained unclear, which further complicated the information process. Some healthcare providers were worried whether families who had made their decision prior to counselling had truly made a well-considered and informed decision. Therefore, families should be offered multiple contact moments with the counsellor to prevent them from making rash decisions.

Another barrier in the decision-making process was the dual role of healthcare providers as scientists and physicians. In the Netherlands, OTC in girls with TS is only performed in a research setting [23]. The research Ethics Committee and a board of patients and patient representatives approved the TurnerFertility study on the condition that all girls with TS are offered OTC, including those with a monosomic karyotype. Despite the small chances of success in this patient group, literature about finding oocytes in girls with a monosomic karyotype has been published [7, 15, 33, 34]. In some cases, healthcare providers had difficulty with the idea of performing an invasive procedure when the odds of success in restoring fertility were small. This dual role led to a conflict of duties in some cases. Healthcare providers recognized the scientific relevance for the TS population, but they sometimes had difficulty justifying the disproportionate burden for some individual patients.

Research in oncological patients suggests that making an active decision about fertility preservation leads to more autonomy and acceptance of the decision, reduces future psychological stress, and ensures less decision regret [2, 35, 36]. However, oncology patients differ from girls with TS. Firstly, fertility preservation in girls with TS is less urgent because the window of exhaustion of the ovarian reserve is much broader. Secondly, performing fertility preservation in oncology patients means a semi-acute intervention and delay of the subsequent cancer treatment [2, 5]. Finally, oncology patients often receive a diagnosis just a few weeks before deciding about fertility preservation which makes them more emotional and more vulnerable compared to girls with TS [2, 5, 26, 27]. Nevertheless, an international expert panel on OTC in girls with TS advised that girls with TS should be fully involved in counselling about fertility and fertility preservation, regardless of their age [23]. However, our results are more nuanced: parents of young girls or girls who received a negative advice on OTC preferred to have had the counselling without their daughter present in order to protect them from disappointment. Nonetheless, many parents and girls were glad to have had the counselling about future options for parenthood, regardless of their decision. For some young girls, we suggest to counsel at first with superficial information with only pictures and, if needed, later in life, a second more extensive consultation.

In our opinion, the results of our qualitative study are relevant for healthcare providers of girls with TS in particular, but also for healthcare providers that implement new technologies in clinical practice in general. Our results highlighted that patients' opinions prior to counselling can greatly influence the final counselling and decision. In order to achieve an optimal informed consent process, our clinical recommendations are (1) encourage both parents and children to receive counselling and consult parents about the appropriate timing for counselling, (2) organize counselling in phases consisting of multiple personal contact moments with the counsellor, (3) be aware of the families' feeling that they have “no choice” by making it a subject of discussion, and (4) when counselling families, emphasize the experimental nature of OTC and the conflicting duties of scientist and healthcare provider.

The validity and data quality of this study have been safeguarded by four aspects: firstly, through triangulation from different perspectives; secondly, by involving healthcare providers who are not part of the TurnerFertility team and healthcare providers who are more critical of the study; thirdly, the survey provided input from a large anonymous population; and fourthly, focus group interviews allowed participants to interact and challenged them to reflect on their opinion and argue their point of view [37, 38]. Nonetheless, the results from our study must be interpreted with caution, since parental focus group participants were self-registered, which might have introduced selection bias. Families with a positive experience and families who opted for OTC seemed more willing to participate in the survey and focus groups, which caused underrepresentation of families who decided for alternative options. Besides, it is appropriate that we acknowledge the low number of participants of FG4, due to the withdrawal of four participants. However, these results give insight into a unique cohort of parents of girls with TS who are allowed to co-decide or decide by themselves. Unfortunately, there were too few girls with TS between the ages of 15 and 18 who wanted to participate, which is why we decided to cancel FG5. We did not invite girls with TS younger than 15 for a focus group interview, as their age and associated psychosocial challenges might make them feel uncomfortable when talking about difficult subjects with other participants. Since we only have survey results from girls with TS and did not interview them, it is possible that we may have missed data that matters in the counselling process. Therefore, a follow-up study will be performed in order to individually interview girls with TS between the ages of 12 and 18 and their parents. Also, both those who have had counselling and those who declined counselling should be included.

Conclusions

International guidelines recommend fertility counselling in TS at a young age to allow girls to make an active decision [16]. This study has shown that early counselling about options for future parenthood was highly valued. Hope and anticipated decision regret may be strong driving forces behind the decision to choose OTC to preserve fertility in girls with TS. Therefore, counselling children and parents in experimental care can be challenging for healthcare providers because of uncertain success rates and the responsibility to ensure a considered decision of the families. Implementing the outcomes of our study in daily practice could lead to a substantial improvement and more patient-centred care in girls with TS.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the research Ethics Committee Arnhem-Nijmegen, approval number [2018-4945]. All participants gave their written informed consent.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

Unconditional grant was received from Merck B.V. (A16-1395), Goodlife, and Ferring.

Author Contributions

Sanne van der Coelen contributed to planning, design, data collection, data interpretation, analysing, original draft, and writing − review and editing. Sapthami Nadesapillai, Myra Schleedoorn, Ron Peek, Didi Braat, Janielle van der Velden, and Kathrin Fleischer contributed to design, data interpretation, analysing, and writing − review and supervision. Anke Oerlemans contributed to planning, design, data collection, data interpretation, analysing, and writing − review, editing, and supervision. All the authors gave their final approval of the article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author Sanne van der Coelen upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants of the survey and focus group interviews for their very valuable contribution to this research.

Funding Statement

Unconditional grant was received from Merck B.V. (A16-1395), Goodlife, and Ferring.

References

- 1.van den Berg H, Repping S, van der Veen F. Parental desire and acceptability of spermatogonial stem cell cryopreservation in boys with cancer. Hum Reprod. 2007 Feb;22((2)):594–597. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benedict C, Thom B, Kelvin JF. Young adult female cancer survivors' decision regret about fertility preservation. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2015 Dec;4((4)):213–218. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2015.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demeestere I, Simon P, Dedeken L, Moffa F, Tsépélidis S, Brachet C, et al. Live birth after autograft of ovarian tissue cryopreserved during childhood. Hum Reprod. 2015 Sep;30((9)):2107–2109. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Fertility preservation in women. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 26;377((17)):1657–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1614676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan-Pyke CS, Carlson CA, Prewitt M, Gracia CR, Ginsberg JP. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC) in prepubertal girls and young women: an analysis of parents' and patients' decision-making. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018 Apr;35((4)):593–600. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1123-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolmans MM, von Wolff M, Poirot C, Diaz-Garcia C, Cacciottola L, Boissel N, et al. Transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in a series of 285 women: a review of five leading European centers. Fertil Steril. 2021 May;115((5)):1102–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hreinsson JG, Otala M, Fridström M, Borgström B, Rasmussen C, Lundqvist M, et al. Follicles are found in the ovaries of adolescent girls with Turner's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002 Aug;87((8)):3618–3623. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.8.8753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grynberg M, Bidet M, Benard J, Poulain M, Sonigo C, Cédrin-Durnerin I, et al. Fertility preservation in Turner syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2016 Jan;105((1)):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schleedoorn M, van der Velden J, Braat D, Beerendonk I, van Golde R, Peek R, et al. TurnerFertility trial: PROTOCOL for an observational cohort study to describe the efficacy of ovarian tissue cryopreservation for fertility preservation in females with Turner syndrome. BMJ Open. 2019 Dec 11;9((12)):e030855. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stochholm K, Juul S, Juel K, Naeraa RW, Gravholt CH. Prevalence, incidence, diagnostic delay, and mortality in Turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Oct;91((10)):3897–3902. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elsheikh M, Dunger DB, Conway GS, Wass JA. Turner's syndrome in adulthood. Endocr Rev. 2002 Feb;23((1)):120–140. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.1.0457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karnis MF. Fertility, pregnancy, and medical management of Turner syndrome in the reproductive years. Fertil Steril. 2012 Oct;98((4)):787–791. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernard V, Donadille B, Zenaty D, Courtillot C, Salenave S, Brac de la Perrière A, et al. Spontaneous fertility and pregnancy outcomes amongst 480 women with Turner syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2016 Apr;31((4)):782–788. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutton EJ, McInerney-Leo A, Bondy CA, Gollust SE, King D, Biesecker B. Turner syndrome: four challenges across the lifespan. Am J Med Genet A. 2005 Dec 1;139a((2)):57–66. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borgström B, Hreinsson J, Rasmussen C, Sheikhi M, Fried G, Keros V, et al. Fertility preservation in girls with turner syndrome: prognostic signs of the presence of ovarian follicles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94((1)):74–80. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gravholt CH, Andersen NH, Conway GS, Dekkers OM, Geffner ME, Klein KO, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: proceedings from the 2016 Cincinnati International Turner Syndrome Meeting. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017 Sep;177((3)):G1–g70. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prasath EB, Chan ML, Wong WH, Lim CJ, Tharmalingam MD, Hendricks M, et al. First pregnancy and live birth resulting from cryopreserved embryos obtained from in vitro matured oocytes after oophorectomy in an ovarian cancer patient. Hum Reprod. 2014 Feb;29((2)):276–278. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oktay K, Bedoschi G, Berkowitz K, Bronson R, Kashani B, McGovern P, et al. Fertility preservation in women with turner syndrome: a comprehensive review and practical guidelines. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016 Oct;29((5)):409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nawroth F, Schüring AN, von Wolff M. The indication for fertility preservation in women with Turner syndrome should not only be based on the ovarian reserve but also on the genotype and expected future health status. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020 Dec;99((12)):1579–1583. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schleedoorn MJ, van der Velden A, Braat DDM, Peek R, Fleischer K. To Freeze or not to freeze? An update on fertility preservation in females with Turner syndrome. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2019 Mar;16((3)):369–382. doi: 10.17458/per.vol16.2019.svb.tofreezeornot. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peek R, Schleedoorn M, Smeets D, van de Zande G, Groenman F, Braat D, et al. Ovarian follicles of young patients with Turner's syndrome contain normal oocytes but monosomic 45,X granulosa cells. Hum Reprod. 2019 Sep 29;34((9)):1686–1696. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wasserman D, Asch A. Reproductive medicine and Turner syndrome: ethical issues. Fertil Steril. 2012 Oct;98((4)):792–796. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schleedoorn MJ, Mulder BH, Braat DDM, Beerendonk CCM, Peek R, Nelen W, et al. International consensus: ovarian tissue cryopreservation in young Turner syndrome patients: outcomes of an ethical Delphi study including 55 experts from 16 different countries. Hum Reprod. 2020 Apr;35:1061–1072. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan TL, Kapa HM, Crerand CE, Kremen J, Tishelman A, Davis S, et al. Fertility counseling and preservation discussions for females with Turner syndrome in pediatric centers: practice patterns and predictors. Fertil Steril. 2019 Oct;112((4)):740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitz VW, Law JR, Peavey M. Karyotype is associated with timing of ovarian failure in women with Turner syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2021 Mar 26;34((3)):319–323. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2020-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li N, Jayasinghe Y, Kemertzis MA, Moore P, Peate M. Fertility preservation in pediatric and adolescent oncology patients: the decision-making process of parents. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017 Jun;6((2)):213–222. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2016.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan SW, Cipres D, Katz A, Niemasik EE, Kao CN, Rosen MP. Patient satisfaction is best predicted by low decisional regret among women with cancer seeking fertility preservation counseling (FPC) Fertil Sterility. 2014;102((3)):e162. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDougall RJ, Gillam L, Delany C, Jayasinghe Y. Ethics of fertility preservation for prepubertal children: should clinicians offer procedures where efficacy is largely unproven? J Med Ethics. 2018 Jan;44((1)):27–31. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-104042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006 2006/01/01;3((2)):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007 Dec;19((6)):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tymstra T. The imperative character of medical technology and the meaning of “anticipated decision regret”. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1989;5((2)):207–213. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300006437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamama-Raz Y, Ginossar-David E, Ben-Ezra M. Parental regret regarding children's vaccines-the correlation between anticipated regret, altruism, coping strategies and attitudes toward vaccines. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2016;5:55. doi: 10.1186/s13584-016-0116-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vergier J, Bottin P, Saias J, Reynaud R, Guillemain C, Courbiere B. Fertility preservation in Turner syndrome: karyotype does not predict ovarian response to stimulation. Clin Endocrinol. 2019 Nov;91((5)):646–651. doi: 10.1111/cen.14076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nadesapillai S, van der Velden J, Smeets D, van de Zande G, Braat D, Fleischer K, et al. Why are some patients with 45,X Turner syndrome fertile? A young girl with classical 45,X Turner syndrome and a cryptic mosaicism in the ovary. Fertil Steril. 2021;115((5)):1280–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Letourneau JM, Ebbel EE, Katz PP, Katz A, Ai WZ, Chien AJ, et al. Pretreatment fertility counseling and fertility preservation improve quality of life in reproductive age women with cancer. Cancer. 2012 Mar 15;118((6)):1710–1717. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wyns C, Collienne C, Shenfield F, Robert A, Laurent P, Roegiers L, et al. Fertility preservation in the male pediatric population: factors influencing the decision of parents and children. Hum Reprod. 2015 Sep;30((9)):2022–2030. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000 Jan 1;320((7226)):50–52. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mason J. Generating qualitative data: observation, documents and visual data. Sage Publications Inc; 2002. Qualitative researching. Chapter 4. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author Sanne van der Coelen upon reasonable request.