Abstract

Annually approximately 2–3 million Americans are so severely injured that they require inpatient hospitalization. The study team, which includes patients, clinical researchers, front-line provider and policy maker stakeholders, has been working together for over a decade to develop interventions that target improvements for US trauma care systems nationally. This pragmatic randomized trial compares a multidisciplinary team collaborative care intervention that integrates front-line trauma center staff with peer interventionists, versus trauma team notification of patient emotional distress with mental health consultation as enhanced usual care. The peer-integrated collaborative care intervention will be supported by a novel emergency department exchange health information technology platform. A total of 424 patients will be randomized to peer-integrated collaborative care (n=212) and surgical team notification (n=212) conditions. The study hypothesizes that patient’s randomized to peer integrated collaborative care intervention will demonstrate significant reductions in emergency department health service utilization, severity of patient concerns, post traumatic stress disorder symptoms, and physical limitations when compared to surgical team notification. These four primary outcomes will be followed-up at 1– 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-months after injury for all patients. The Rapid Assessment Procedure Informed Clinical Ethnography (RAPICE) method will be used to assess implementation processes. Data from the primary outcome analysis and implementation process assessment will be used to inform an end-of-study policy summit with the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. The policy summit will facilitate acute care practice changes related to patient-centered care transitions over the course of a single 5-year funding cycle.

Keywords: Peer, Patient-Centered Care, Collaborative Care, PTSD, Emergency Department Information Exchange, Trauma Care Systems

INTRODUCTION

Physical injury constitutes a major public health problem for US trauma-exposed patients.1-3 Each year in the United States between 2–3 million Americans are so severely injured that they require inpatient hospitalization.1,2,4,5 Injured trauma survivors constitute a high need patient population with multiple complex medical and mental health comorbidities, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).6,7 Physically injured trauma survivors with multiple comorbidities are at risk for fragmented care transitions and recurrent emergency department visits and hospitalizations.8–22 After injury, PTSD and related comorbidities are associated with a broad profile of functional impairments, including diminished physical function and inability to return to work.23–28 PTSD and comorbidities are also associated with increased health care and societal expenditures.29–33

Peer interventionists are becoming a mainstay of treatment delivery for multiple health conditions across diverse US healthcare systems.34–36 The potential contribution of peer interventionists in the delivery of high quality patient-centered care has been espoused across disease conditions.37–45 However, unlike other areas of clinical medicine, acute post-injury interventions have yet to comprehensively integrate peer interventionists or clarify optimal roles for peer interventionists within a collaborative team. A number of potential roles exist for integrating peers including, bedside support and empathetic engagement and care coordination.46 Initial studies in the rehabilitation literature suggest that peer interventionists may aid care transitions after severe spinal cord and traumatic brain injury47–50, however no large scale acute care trials have integrated injured peers into multidisciplinary teams.47–50

Collaborative care interventions hold promise for the integration of peer interventionists into multidisciplinary teams in the treatment of injured patients. Collaborative care interventions include care management, pharmacotherapy targeting mental health and substance use disturbances, and behavioral intervention elements.51,52 A large body of research now has established the effectiveness of collaborative care in reducing depressive, anxiety, and pain related symptom presentations in primary care settings.53–58 52,54,59–63 In acute care settings, stepped collaborative care interventions appear to be effective in reducing the symptoms of PTSD and related comorbities. 64,65 Peer-integrated collaborative care interventions for US trauma care systems can be supported by information technology innovations, including the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE).20–22,66–68

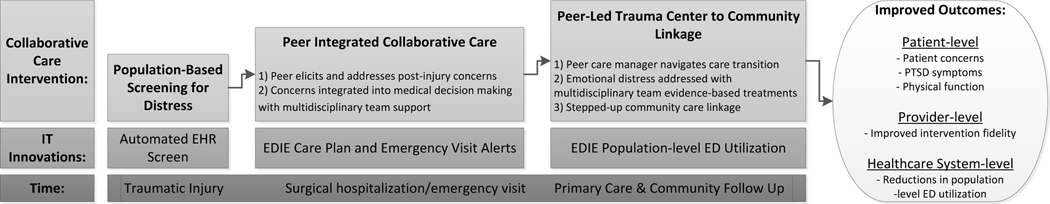

The introduction of peer-integrated, coordinated team activity into trauma center multidisciplinary teams may improve outcomes of great relevance to injured patients and their caregivers including each patient’s unique constellation of posttraumatic concerns. For front-line providers, peer integrated collaborative care intervention delivery may improve care processes, including adherence to evidence-based counseling and medication treatments.52,63 Finally, from a trauma care system perspective, the peer-integrated collaborative care model may reduce unnecessary health service utilization. The study team has an established track record of using comparative effectiveness trial designs that contrast collaborative care intervention elements with usual care, or enhanced usual care control conditions to influence national trauma center policy mandates and clinical practice guideline implementation.7,52,60,69,70 Given prior studies and the nationwide movement towards incorporating peer support, a next critical investigative step is a large scale randomized comparative effectiveness trial that tests an information technology enhanced peer integrated collaborative care intervention for a generalizable sample of injured patients.

The primary aim of the investigation is to compare emergency department health service use, severity of patient concerns, PTSD symptoms and physical function for patients randomized to the two conditions. The study hypothesizes that patients receiving the peer-integrated collaborative care intervention, when compared to the surgical team notification condition, will demonstrate significant reductions in post-injury emergency department utilization as documented by EDIE data on the intent-to-treat sample. The investigation also hypothesizes the peer-integrated collaborative care intervention will be associated with significant reductions in the severity of post-injury concerns, as well as reductions in PTSD symptom levels, when compared to the surgical team notification condition. Improvements in physical function are also hypothesized for patients receiving the peer-integrated collaborative care intervention.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Design Overview.

The overarching goal of this investigation is to develop and implement optimal peer-integrated collaborative care interventions for injured trauma survivors treated in US trauma care systems. All study participants will be recruited from the University of Washington’s Harborview level 1 trauma center. Harborview is the only level 1 trauma center serving the five state WWAMI (Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho) region. Harborview admits both adult and pediatric trauma survivors and serves socioeconomically diverse “safety net” populations. The study team anticipates the demographic, clinical and injury characteristics of patients to be recruited in the trial will resemble prior Harborview clinical trial patient characteristics.7,52,63

Injured trauma survivors ≥ 18 years of age will undergo electronic health record (EHR) screening for high levels of emotional distress (i.e. severe post-injury concerns, PTSD symptoms).71 Patients who are at risk on the EHR screen will be approached for informed consent. After informed consent is obtained, patients’ posttraumatic concerns will be assessed and patients will be screened with the PTSD checklist;72 patients with ≥ 1 severe posttraumatic concern and scores of ≥ 35 on the PTSD checklist will be randomized. A total of 424 patients will be randomized to peer-integrated collaborative care (n = 212) and surgical team notification (n =212) conditions. Intervention activity will continue for up to six months after the injury hospitalization, while follow-up continues for 12-months after the hospitalization. Emergency department use, patient concerns, PTSD symptoms, physical function and other outcomes will be assessed at 1-, 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-months after injury for all patients.

The investigation aims to integrate injured peers as care managers with front-line acute care providers as part of a multidisciplinary team. In the hours, days, and weeks after injury, peers will elicit patient post-injury concerns and target these concerns for amelioration while also working with other members of the intervention team to incorporate patient and caregiver preferences into medical decision making. Additionally, the peer will work with other team members to link injured patients’ care from inpatient and emergency department settings to primary care and community services. Working with peers, clinical and other study team members (e.g. MSW, MD) will simultaneously deliver evidence-based medication and psychotherapeutic elements to injured patients with high levels of PTSD and other symptoms. Evidence-based intervention elements will be delivered during routine post-injury patient encounters in trauma wards and emergency departments, in outpatient clinics, in community settings, and over the telephone. All study procedures were approved by the University of Washington International Review Board. The IRB approved protocol is currently enrolling patients.

Inclusion Criteria.

Patients determined to be at risk on the electronic health record screen will be approached for informed consent. After informed consent is obtained, patients will be screened for emotional distress; patients who score ≥ 35 on the PTSD checklist and endorse ≥ 1 severe posttraumatic concern will be randomized into the longitudinal portion of the investigation.52,62,63 Patients will be included if they are residents of Washington, Oregon, California, or Alaska. Prior to randomization, all patients will complete the full baseline assessment.

Exclusion Criteria.

Patients will only be excluded if they required immediate psychiatric intervention (i.e., self-inflicted injury, active psychosis), or are currently incarcerated; patients that do not speak either English or Spanish will also be excluded from the protocol; patients with less than two pieces of contact information (e.g. telephone or mailing address) who are not able to engage in follow-up will also be excluded from the protocol. The trial will only include English or Spanish speaking patients as prior study team investigation has previously documented over 40 different languages spoken by Harborview patients making the translation of consent documents and scales in multiple different languages impractical.73,74 Attempted consent for patients who are disoriented or delirious will be postponed; if a potential patient subject’s combined score on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)75 is < 15 and/or questions 1 and 2 of Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE)76 is < 7, the baseline interview will be postponed.

Electronic Health Record 10 Domain PTSD Risk Factor Eligibility Screen.

Each morning a study team member will review a list of all newly admitted injured patients with associated identifiable information and available 10 domain PTSD screening data. A study team member will conduct an electronic health record 10 domain PTSD screen.71 The 10 domain PTSD risk factor items pulled from the EHR are: 1) Gender (non-Male), 2) Race (non-White), 3) Insurance (Veteran insurance or no commercial insurance), 4) Treated in ICU during the injury admission, 5), BAC positive, or any substance disorder ICD from EHR, 6) Any psychiatric disorder ICD from EHR, 7) PTSD ICD from EHR, 8) Tobacco use, 9) Injury inflicted by another (i.e., intentional injury), 10) At least one prior hospitalization. Patients who meet three or more PTSD risk factors will be approached for participation by a study team member.

Baseline Interview and Further Eligibility Screening.

The study team member will then administer the study eligibility screening questions on the baseline interview which includes concern and posttraumatic symptom assessments to each consenting subject. The concern assessment asks each subject “Of everything that has happened to you since you were injured, what concerns you the most?” Subjects will then be asked to rate the severity of each concern on a scale from one to five with one being not at all concerning and five being extremely concerning. Subjects will also go through the PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version (PCL-C) for DSM-IV. Subjects will screen into the randomized portion of the study if they have ≥ 1 severe posttraumatic concern and ≥ 35 on the PCL at the time of injury.71

Randomization.

After completing the baseline assessment, subjects are randomized to one of two active comparator conditions. A total of 424 patients will be randomized to either receive surgical team notification to initiate a mental health consultation (n = 212), or receive a peer-integrated collaborative care intervention (n = 212). Randomization will occur in a 1:1 ratio according to a computer-generated random assignment sequence in blocks of either 4 or 6 patients, prepared by the study biostatistician. Opaque envelopes containing patient randomization status will be opened by study intervention team members after individual patients screen into the investigation. Research assistants conducting follow-up interviews remain blinded to patient intervention and control group status over the course of the 12-month study.77

Intervention and Enhanced Usual Care Control Conditions.

The two approaches to be compared are a peer-integrated collaborative care intervention versus trauma surgical team notification of patient emotional distress. The two approaches were selected, in part, as they can be feasibly implemented in the acute care medical context.63,78,79 Table 1 provides a detailed comparison and role breakdown for each condition.

Table 1.

Protocol Elements and Team Member Activities for Patients in the Information Technology Enhanced Peer-Integrated Collaborative Care Intervention versus Enhanced Usual Care Control Study Arms

| Technology Enhanced Peer-Integrated Collaborative Care Intervention | Enhanced Usual Care Control |

|---|---|

| Research assistant (RA) elicitation of post-injury concerns and symptomatic distress in baseline interview | Research assistant (RA) elicitation of post-injury concerns and symptomatic distress in baseline interview |

| Randomization with allocation concealment | Randomization with allocation concealment |

| Not Received | Trauma surgery recommendation for mental health consultation (e.g., trauma social work, psychiatry consult, rehabilitation psychology, spiritual care, addiction intervention or other mental health service) |

| Peer interventionist and other clinical study team members elicit posttraumatic concerns and target for improvement | Not received |

| Peer interventionist and other clinical study team members provide care management between trauma center to primary care and community resources | Not received |

| MSW interventionist and other non-peer clinical study team members (e.g., psychiatrist) provide evidence-based CBT & MI | Not received |

| MSW interventionist and other non-peer study team members (e.g., RC) administer symptom assessments (e.g., CESD, IES) | Not received |

| MD or MSW perform suicide risk assessment and safety planning | Not received |

| MD or MSW deliver pharmacotherapy symptom assessment | Not received |

| MD psychiatrist recommends psychotropic medication prescription | Not received |

| Peer interventionist, MD, MSW or other providers or study team members (e.g., RC) log intervention electronically (e.g., in REDCap) | Not received |

| MD, MSW, or other clinical study staff provides 24/7 cell phone coverage | Not received |

| RA blinded follow-up telephone assessment of post-injury concerns and symptomatic and functional outcomes | RA blinded follow-up telephone assessment of post-injury concerns and symptomatic and functional outcomes |

| EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT INFORMATION EXCHANGE (EDIE) ELEMENTS | |

| MD, MSW or other non-peer study team members (eg. research coordinator [RC]) add patient to Intervention study group within EDIE | MD, MSW or other non-peer study team members (eg. research coordinator [RC]) add patient to Control study group within EDIE |

| MD, MSW, or other non-peer study team members (e.g. RC) adds care plan to patient’s EDIE profile stating that patient is being followed by a team at Harborview and provides 24/7 cell phone number to facilitate care coordination | Not Received |

| EDIE study group enrollment initiates text and/or email alerts to 24/7 cell phone and clinical study team members when patient arrives at emergency departments nationwide | EDIE study group enrollment initiates text and/or email alerts to 24/7 cell phone and clinical study team members when patient arrives at emergency departments nationwide |

| EDIE collects real time follow up data on patient’s outpatient and emergency department visits | EDIE collects real time follow up data on patient’s outpatient and emergency department visits |

Note. CBT=Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; MI=Motivational Interviewing; CESD=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

a. Enhanced Usual Care Control Condition.

Trauma surgery team notification of patient emotional distress, with suggestions for mental health inpatient consultation (e.g., MD, PhD, MSW, addiction intervention, chaplaincy or other psychosocial consult service) will be the comparator condition. Surgical team notification of patient emotional distress with recommended mental health consultation constitutes a frequently employed, feasibly implemented comparator condition. Prior investigation documents that nationally between 50–80% of US acute care centers routinely provide mental health consultation for high levels of emotional distress (e.g., PTSD and depressive symptoms) and/or substance use (e.g., alcohol use problems).79 Previous data collected at the Harborview level I trauma center demonstrates that of 207 patients with high PTSD symptom levels, 89% were seen by a social worker, 22% were seen by a chemical dependency counselor, 17% were seen by a clinical psychologist, and 8% were seen by a psychiatrist.80

b. Peer-Integrated Collaborative Care Intervention.

Previously injured peers will work alongside front-line acute care providers in the delivery of collaborative care. The team will include both peers and study team case managers (e.g. MSW). The collaborative care team may work to link injured patients’ care from inpatient and emergency department settings to primary care and community services. Care coordination will include a series of intervention components that have been previously shown to improve acute care to primary care and community transitions. Injured patients randomized to the collaborative care intervention may be visited by the peer and/or other collaborative care team members while in the hospital. Peers and study team case managers will elicit and target for improvement each patient’s concerns, needs, and preferences. Elements of the intervention may be delivered during routine post-injury patient encounters in trauma wards, emergency departments, outpatient clinics, community settings, over the telephone, through secure web-based audio/video conferencing (e.g., Zoom) or other electronic means. In prior investigations care management conversations derived from concern elicitation have spanned physical injury, work and finance, social (e.g., impact of injury on family and friends), legal, psychological and medical domains. Case managers are generally encouraged to discuss these topic areas with patients and then bring summaries of these discussions back to supervision meetings. For two topic areas that may derive from general concern discussions, psychotropic medication side effects and suicidal ideation/intent, peers will receive specific training for the procedures for reporting back to the study team information derived from these specific topics. For psychotropic medication side effects, while peers may initially hear from patients about these symptoms, only MSW, MD, or other study team licensed providers will follow-up with formal psychotropic medication symptom assessments and recommendations.

Study team members may ask about treatment preferences and schedule ongoing times to meet/call the patient. Whenever possible, with the injured patient’s permission, family members and other primary post-injury caregivers will be incorporated into the care management intervention. The peer and case manager may also give the patient the study team’s 24-hour/7 days per week telephone and text message contact number and encourage texts/calls for spontaneous questions, needs, and concerns.

Collaborative care intervention team members may be trained in delivering evidence-based Motivational Interviewing (MI) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) elements during routine post-injury patient encounters in trauma wards, emergency departments, outpatient clinics, community settings, over the telephone, through secure web-based audio/video conferencing (e.g., Zoom) or other electronic means. A body of evidence supports the effectiveness of brief MI interventions targeting alcohol use problems. Flexibly delivered CBT interventions have been used to successfully target PTSD. 81,82

Psychopharmacologic intervention, including the use of Serotonin Specific Re-uptake Inhibitor (SSRI) and Serotonin Norepinephrine Re-uptake Inhibitor (SNRI) antidepressants, are also recommended in the treatment of patients with PTSD and/or depression symptoms.52,58,83,84 The medication intervention component aims to initiate and ensure adequate follow-up of pharmacologic treatment targeting symptoms of PTSD and/or depression. Members of the study team may perform medication assessments, assessment of response to psychotropic medications, including side effects, medication recommendations to providers, and medication prescription in a number of settings including trauma inpatient wards, emergency departments, trauma surgery outpatient clinics, over the telephone, and in the community. For all psychotropic medication prescriptions, the collaborative care team will attempt to consult with inpatient, outpatient, or primary care providers with regard to medication recommendations.

The Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE) platform supports TSOS Peer intervention delivery (Table 1).

A novel information technology feature supports the peer-integrated collaborative care intervention. The EDIE system allows collaborative care team members to implement electronic health care record innovations, such as the creation of care plan notifications that provide the study team contact information for the care of individual patients that can be viewed across emergency department sites utilizing the system. EDIE also provides real-time work-flow integrated electronic alerts that allow collaborative team providers to be notified when patients make recurrent visits to an emergency department. EDIE is currently operative in 22 states including Washington, Oregon, California, and Alaska.

Intervention Training and Supervision.

Each peer will receive training derived from manuals developed by the American Trauma Society.85,86 The American Trauma Society manuals outline methods for ensuring an adequate flow of peers into the team. Of note, peers are trained to broadly engage multiple diverse patients rather than to more narrowly focus on matched peer-patient characteristics. For example, a peer that is experienced a motor vehicle crash injury event can be trained to provide support to survivors of injury events related to interpersonal violence.

In addition to the initial trainings, peers receive ongoing supervision; a novel aspect of the intervention is that the peers will receive two types of ongoing supervision. The peers and other study team members will receive standard post-injury collaborative care clinical supervision delivered by Dr. Zatzick and potentially other study team members. These regular (e.g., weekly) supervisory sessions will review the progress of patients randomized into the protocol, the progress of the stepped care for intervention patients, and other topics. This regular caseload supervision will be facilitated by the study intervention data management tool (e.g., REDCap).

The peers and potentially other study team members will also receive monthly peer/patient advocacy supervision from the co-Principal investigators (DZ & PT), and other members of the study Patient and Peer Stakeholder Advisory Group (e.g., SS, PA, KA). Peter Thomas and other members of the Patient and Peer Stakeholder advisory group have prior experience conducting peer interventions/performing in the peer interventionist role. This supervision may take the form of presentation of cases by one or more of the study clinical team (e.g., MLW peer interventionist) on the monthly stakeholder group call. Beyond patient case presentations, the experiences of the peers as interventionists will also be a key topic discussed on the calls.

Blinded telephone follow-up interviews.

Patient-reported outcomes will be assessed at 1-, 3-, 6-, 9- and 12 months after the injury event by telephone interview. Telephone interviews have been found to be reliable and valid in the assessment patient reported outcomes for injured trauma survivors.52,63,69 In order to minimize bias, the research assistants conducting the telephone follow-up interviews will be blinded to the patient’s study group assignments.

Follow-up Procedures.

Injured trauma survivors admitted to safety net hospitals constitute a low-income, ethno-culturally diverse patient population that can present challenges for longitudinal retention in comparative effectiveness trials; the study team has developed specific methods to obtain high follow-up rates with this vulnerable patient population.87,88 89In order to optimize retention of patients for follow-up interviews required for the patient-reported outcomes assessments, at the baseline interview patient subjects will be asked for phone numbers/addresses of at least two contact sources (e.g., friends or relatives). After a trauma, patient subjects sometimes relocate temporarily in order to receive better care, such as movement from independent living to a skilled nursing facility; many patients are also homeless. Therefore, in addition to contacting patient subjects through the information they provide during the initial baseline interview, the follow-up team will utilize several approaches to attempt to stay in touch with patient subjects across the study window. All the approaches described below are only attempted for patients who consent to these procedures. The approaches are: 1) Contacting other people in the patient subject’s life, 2) Looking at hospital records. If the follow-up team is unable to reach a patient subject after repeatedly trying to contact them through the information provided, they may have the research coordinator review the hospital record for any updated contact information or 3) Conducting a public records search, or the use of social media. These follow-up procedures are further described below.

At the time of recruitment in the hospital, the study team will ask patient subjects for at least two pieces of contact information (the absence of sufficient contact information is an exclusionary criteria). One piece will need to be a phone number, while the second piece of contact information could include the patient’s address, email address, social media (e.g., Facebook page) or any of the aforementioned pieces of contact information for a relative or friend (referred to as alternate contacts). In the event that the subject’s contact information changes (a common event after injury admission); the follow-up team may reach out to these alternate contacts in an effort to get back in touch with the subject. Over the 12 months after the injury, the follow-up team may perform scheduling or check-in phone calls with subjects to ensure that the contact information on file is up to date.

VI. Outcome Measures and Other Study Assessments.

Overview.

The measures and timing of administration are described with references provided that document established scale psychometric properties (Table 2). All assessments have been previously employed by the study team in prior acute care medical investigations.

Table 2.

Study Assessments

| PATIENT-REPORTED OUTCOME MEASURES | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Measures Delivered During Specified Interview Time Points | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Interviews | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Scale | Baseline | 1month | 3month | 6month | 9month | 12month |

|

| ||||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)75 | ✓ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)76 | ✓ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| Injury Event | ✓ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| Posttraumatic Concerns61 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Demographic Characteristics | ✓ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| PTSD Checklist (PCL) (DSM-IV)72 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| PTSD Checklist (PCL) (DSM-5) 90 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Patient Health Questionnaire Depression (PHQ-9)91 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (MOS SF-12)92 | ✓ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (MOS SF-36)93 | ─ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT-C 3-item)94 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Self-Report Health Service Utilization - preinjury | ✓ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| Self-Report Health Service Utilization – post-injury (since last interview) | ─ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Medications | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Single Item Drug and Tobacco52 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| NSCOT Cognitive Screen (NSCOT)95 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Pain (Single item from SF-36) - pre-injury93 | ✓ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| Pain (Single modified BPI item) – current96 | ✓ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| Patient Satisfaction with Care52 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Employment/Work Status | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Willingness for Treatment | ✓ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ✓ |

| Website and Smartphone Application Acceptability63 | ✓ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| Reactions to Research Participation Questionnaire (RRPQ 1 item)97 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Trauma History Screen - pre-injury*98 | ─ | ✓ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| Stressful Life Events99 | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ✓ |

| CBT Items7 | ─ | ─ | ─ | ✓ | ─ | ✓ |

| Technology Use and Healthcare Utilization | ─ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Intervention Acceptability†63 | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ✓ |

| Client Satisfaction Questionnaire‡ 100 | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ✓ |

| Intervention Specific Measures | ||||||

| Scale | ||||||

| The Impact of Event Scale – Revised (IES-R)‡101 | ||||||

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)‡102 | ||||||

| PC-PTSD 4 item‡ 103 | ||||||

a. Emergency Department Health Service Utilization.

Emergency Department health service utilization will be assessed using the Emergency Department Information Exchange System (EDIE) developed by Collective Medical Technologies.66–68 EDIE is a novel clinical informatics tool that aggregates in real time emergency department visits for the population of patients presenting to any Emergency Department in Washington and Oregon. EDIE is currently integrated into the medical record at the University of Washington and Harborview Medical Center. For the purposes of the current trial, EDIE allows population-based 12-month follow-up of all emergency department visits across Washington, Oregon, Alaska, and California for the intent-to-treat sample of intervention and control patients. Recent study team investigations document the reliability and validity of EDIE emergency department assessments. 66–68 For intervention patients EDIE data on emergency department care plans and Harborview patient alerts will also be obtained.

b. Posttraumatic concern severity and domain.

61,104 As in prior study team investigations, the baseline and follow-up interviews will begin with the assessment of each patient’s unique constellation of post-injury concerns; responses to the concern items will be audio-recorded. The concern question asks, “Of everything that has happened to you since you were injured, what concerns you the most?” Patients are allowed to express an unlimited number of concerns. Following each concern elicitation, patients are asked to rate the severity of the concern on a scale from one to five, with one being not at all concerning and five being extremely concerning. Based on prior study team investigation, a severe concern is defined as a concern rated as a 5 by the patient. Prior psychometric investigation by the study team documents that the severity of post-injury concerns mirrors the longitudinal trajectory of PTSD symptoms and functional impairments.61,104 Procedures for the coding of posttraumatic concern domains are derived from previously described content analytic methods.61,104 A previously developed code book describing concern domains and coding procedures will be used.61,104 The initial concern question and its explanation constituted the unit of analysis. The frequency of patients reporting themes from one or more domains, along with the concern severity, will be tabulated. In prior investigations, the Kappa statistic was used to assess interrater reliability with values ranging from 0.77–0.78.61,104

c. PTSD Symptoms (PTSD Checklist).

72 The PTSD Checklist, a 17-item self-report questionnaire, will be used to assess PTSD symptoms.72 The instrument yields both a continuous PTSD symptom score and a dichotomized diagnostic cut point for symptoms consistent with a DSM diagnosis of PTSD; the DSM-IV version will be used with 4 additional question criteria added so that either DSM-IV or DSM-V diagnostic criteria can be evaluated (see instrument appendix). A series of investigations have demonstrated the reliability and convergent and construct validity of the PTSD Checklist across trauma-exposed populations.105 Cronbach’s alpha for the 17 item scale in a prior investigation with injured trauma survivors by the study team was 0.92.63 In a study of injured motor vehicle crash survivors, a correlation of 0.93 between the PTSD Checklist total score and the gold standard Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale diagnostic scale was documented.105

d. Physical Function and other Functioning and Quality of Life Outcomes (Medical Outcomes Study Short Form36, MOS SF-36).

92,93 The investigation will use the SF-36 to assess functioning and quality of life outcomes. Eight domains are assessed, including physical function, pain, general health, role physical function, role emotional function, vitality, social function, and mental health. The SF-36 has established reliability and validity and the measure has been used extensively with traumatically injured populations.93,95,99,106 The study team used the Physical Component Summary (PCS) sub-scale to assess post-injury physical function as a primary outcome. Cronbach’s alpha for the MOS SF-36 PCS in prior investigations by the study team was 0.90.52,99

Electronic medical record data.

The investigation will determine injury severity at baseline during the index admission from the electronic medical record International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) Codes using the Abbreviated Injury Scale and Injury Severity Score.107–110 Similarly, the presence of one or more chronic medical conditions will be ascertained using ICD-10 codes. Chronic medical conditions to be assessed include diabetes, obesity, epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, hypertension, carcinoma, disorders of blood coagulation and other chronic cardiac, pulmonary, liver, neurologic and renal conditions.71 Mental health consultations across psychiatry consult, rehabilitation psychology, trauma social work, addiction intervention and chaplaincy services and other services, laboratory toxicology results, insurance status, length of hospital and intensive care unit stays, and other clinical characteristics will be abstracted from the electronic medical record.

Safety and Adverse Event Reporting.

Across the two conditions the study will report suicide attempts, hospitalizations due to suicidal ideation, hospitalization due to study recommended psychotropic medication, and all-cause mortality. These adverse events will be reported to and reviewed by the study Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) and the University of Washington IRB.

Rapid Assessment Procedure Informed Clinical Ethnography (RAPICE) derived implementation process assessment.

111 Prior work by members of the investigative team has established pragmatic methods for simultaneoulsy assessing clincal trial implementation processes and evaluating the potential for sustainable implementation of trial findings.60 The RAPICE mixed method approach embeds participant observation within front-line study team members engaged in rolling-out clincial trial procedures, combined with regular data review/analyses with an implementation science mixed methods expert consultant. RAPICE has also been used as a formative evaluation procedure, as part of pilot investigations, to refine collaborative care intervention elements and track treatment adherence and adaptations in real time. The RAPICE approach aims to facilitate feasibly implemented “nimble” mixed method formative evaluations that strive to attain the pragmatic comparative effectiveness trial goal of minimizing research costs per subject randomized. Building upon these prior investigations, the TSOS Peer investigation will use the RAPICE60 approach to evaluate study implemenation processes. A primary source of RAPICE field observations will be the embedding of participant observation within regular caseload supervision staffing meetings. A psychiatric provider will lead the weekly caseload meetings; The provider will record RAPICE field observations across pre-specified RE-AIM112 domains including Reach, Effectiveness Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (Table 3). Also, as part of the RAPICE approach, for intervention patients the study team will complete end-of-study final case reviews that document key care processes hypothesized to be associated with study outcomes.

Table 3.

| RE-AIM Domain | Study Quantitative Assessment | Previously described implementation barriers for RAPICE assessment | RAPICE participant observation questions | Potential Policy Summit Questions/ Themes Derived from RAPICE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reach | • n enrolled divided by N in target population | • Prior studies, describe patients who prefer not to have care coordinated | • What factors explain site Reach variations? • What are the reasons patients opt out of the trial? • What are the barriers to enrolling patients? |

• Does Reach/breadth of applicability/ of the intervention warrant organizational, regional or national policy requirements? |

| Effectiveness | • Comparison of Intervention vs Control outcomes | • Lack of patient engagement • Lack of ability of team to implement intervention elements |

• What factors explain variations in effectiveness across sites? | • Are there policy changes that occurred during the study that introduced variability in the intervention delivery? • Do these policy changes differentially impact control versus intervention conditions? |

| Adoption | • % Provider and/or clinical service participation | • Negative staff attitudes toward system change • Lack of staff/peers with adequate skills to intervention |

• What impacts provider participation? • What impacts staff/peer baseline aptitudes and skill acquisition? |

• Will there be sites that spontaneously adopt the intervention without policy requirements? • What characterizes these innovator/early adopter sites? |

| Implementation | • Documentation of intervention adaptations across sites • Quantification of provider and site variability in the use of collaborative care or care transition CPT codes |

• Implementation of intervention strains existing resources • Lack of access related to adequate provider CC supervision and support |

• What were the barriers to implementation of the intervention • What was the nature of the adaptations to the intervention that occurred over time? • Why did adaptations to the intervention occur? |

• What organizational, regional and national policies might assist with site implementation of the intervention? |

| Maintenance | • Maintenance of intervention as delivered in the investigation (Yes/No) • If only partially maintained quantification of adaptations to the intervention |

• Lack of ongoing funding as a barrier to sustainability | • What are modifications made by providers after the study? • In what form will the components of the intervention be sustained? • What are the barriers to maintaining the peer intervention program? |

• What policy levers such as health care system mandates or CPT code availability might facilitate site/ organizational maintenance of the intervention? |

Considerations Related to the Incorporation of New Standards for Complex Interventions.

The Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute (PCORI) has outlined a series of new requirements for describing the delivery of complex interventions.117 The peer integrated collaborative care intervention constitutes a complex intervention as it has both multiple components and multiple casual pathways; additionally the intervention is complex in its targeting of a heterogeneous patient population and in its multifaceted adoption strategy for the acute care medical context.118–120 Numerous aspects of the complexity of the intervention are articulated throughout this manuscript. The conceptual framework underlying intervention effects is articulated in Figure 1, and documentation of how adaptations to the intervention and comparator conditions will be recorded are described as part of the implementation process assessment. (Table 3).116 The tracking of adaptations to the intervention and comparator condition are described as part of the RAPICE method (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Peer Integrated, IT Enhanced Stepped Collaborative Care Intervention Framework

The PCORI guidelines for complex interventions are heavily reliant upon a single implementation scientist stakeholder perspective.121,122 The study team is comprised of implementation science stakeholders, but also patient, front-line provider and trauma surgical policy member stakeholders. Therefore stakeholder input was obtained from the multiple diverse study team perspectives in considering an appropriate series of potential secondary data analytic questions relevant to the TSOS peer implementation process assessments (Table 4).

Table 4.

Potential Secondary Analyses Related to the Study Implementation Process Assessment

| Stakeholder Question | Research Question | Sample | Analytic Model | Example Question/Hypothesis from TSOS Peer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Can all of the patients hospitalized at the trauma center benefit from the intervention, or are there some individuals who may have benefit but others not? | How does the cumulative burden of disorders impact treatment response? | Intent-to-Treat | Moderation/Treatment Effect Heterogeneity 123,124 125 | As with prior study team acute care investigation, does an increasing burden of comorbid conditions (e.g., methamphetamine use problems diminish observed treatment effects) |

| Does receiving evidence-based treatment reduce symptomatic distress and improve function? | How does receiving an adequate dose of evidence-based treatment impact outcomes? | Intent-to-Treat | Mediation124,126,127 | Receiving an adequate dose of medications is associated with reduced PTSD symptoms |

| Is engagement with the peer a key factor in the overall intervention success? | What are the interrelationships between treatment engagement and treatment response? | Intervention Subsample | G-methods/ computation128 | Only intervention patients who first engage in treatment and then receive/maintain an adequate dosage of evidence based treatment will manifest a treatment response |

| Does adding a peer interventionist to the team reduce posttraumatic concerns, improve PTSD and function and reduce emergency utilization? | What is the isolated impact of the peer intervention on outcomes? | Intervention Subsample | Dismantling studies129 | Does an increasing number of peer visits/time enhance treatment engagement? Does this observation hold after adjusting for other factors known to impact treatment effects? |

Data Analyses

Overview.

All primary statistical analyses will be conducted with the intent-to-treat sample. The primary purpose of the statistical analyses is to examine and compare trends in emergency department health service utilization, posttraumatic concern severity, PTSD symptoms, and physical function longitudinally between patients in the peer-integrated collaborative care intervention and patients in the surgical team notification arms of the study. The major outcome variables are the continuous and dichotomous assessments of EDIE derived emergency department health service utilization,66 patient reported posttraumatic concerns,61,104 PTSD symptoms (PTSD Checklist),72 and physical function Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (MOS SF-36).92,93

The primary statistical analyses will test the hypothesis that patients randomized to the peer-integrated collaborative care intervention will demonstrate reductions in emergency department health service use when compared to patients randomized to the trauma surgery notification condition over the course of the 12-months after injury. Primary analyses will also assess whether collaborative care intervention patients demonstrate longitudinal reductions in posttraumatic concern severity and PTSD symptoms and improvements in physical function when compared to trauma surgery notification patients.

The study team will use mixed effects regression models to test these hypotheses for both continuous and discrete outcomes.130–133 The investigative group has extensive experience with this analytic approach in the analyses of longitudinal data after injury.28,52,60,63,134 In addition, these models will allow the use of covariates that model potential sources of non-response bias and time-dependent covariates. This type of model also allows the specification of random or fixed effects and the form of the serial correlation over time (if heterogeneity changes over time).

The effect of major interest will be the time by treatment group interaction term. For these models, repeated measurements of the baseline, 1-, 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month outcome assessments (i.e., EDIE documented emergency department utilization, concern severity, PTSD Checklist and MOS SF-36 Physical Components Summary (PCS) scale scores) will be the dependent variables. For all dependent variables, the study team will first fit models containing only time categories, intervention, and intervention by time interactions. The form of the dependent variables will determine the link function used.

The impact of including covariates in the model will be examined in planned sensitivity analyses. As in prior study team investigation, sensitivity analyses will be used to assess the impact of key assumptions. Important injury and demographic characteristics, such as Injury Severity Score and age, will be entered into the models as covariates in planned sensitivity analyses. Prior to these analyses, the study team will examine baseline treatment group differences, using the appropriate statistics for the distribution of the variable. Although randomization should ensure balance between the two groups, it is essential to control for any known confounders in the design and analysis to prevent a biased assessment of the treatment effect. Any baseline injury, demographic, or clinical variables found to be statistically significant in this analysis will also be included as covariates in the regression models. Care processes will also be examined as part of the secondary data analytic plan.

For the primary study outcome of EDIE emergency department data for the intent-to treat sample, prior investigation documents that the study team can attain ≥ 95% patient follow-up at all-time points; therefore, for the study primary outcome, no subject missing data is anticipated. For the primary patient-reported outcomes of posttraumatic concerns, PTSD symptoms and limitations in physical function, some attrition is expected in the study sample. In prior studies the investigative group has consistently achieved follow-up completion rates ≥ 80% between 6–12 months post-injury for patient reported outcomes.28,52,60,63,134,135 The study team has developed a series of methods for proactively minimizing patient attrition in follow-up that often involve patient subject informed consent prior to implementation. These methods include obtaining multiple pieces of contact information at the time of the baseline interview, maintaining contact with the patient’s social network, monitoring emergency department and hospital records for evidence of new patient contact information, conducting ongoing public records searches and conducting social media searches.

Missing data can contribute to biased estimations of treatment effects. Assumptions about the nature of missing data are crucial to the type of statistical analysis chosen. Full information maximum likelihood estimates from mixed effects regression models accommodate missing data that are missing at random (MAR). Missingness with MAR data allows dependence on previously observed outcome variables.136–138 Based on our relatively low attrition rates and our inability to find consistent variation in past investigations, we believe that MAR is a reasonable assumption. However, we will perform a sensitivity analysis on our data using multiple imputations.138–142

Whenever patients decline participation or withdraw from the study, the study research assistant will inquire as to why the individual did not want to participate. The study team will also document when patients miss a follow-up interview but do not formally withdraw from the study. The prior study team PCORI funded investigation attained ≥ 80% follow-up at each time point for patients randomized to both conditions.62

Secondary Analyses.

Potential secondary analyses are outlined above in Table 4. As an example, prior investigations by the study team suggest that a subgroup of injured trauma survivors with a greater cumulative burden of mental health conditions including PTSD, alcohol and drug use disorders, medical comorbidities, firearm violence, physical assault, and suicide related injury admissions, are at markedly increased risk for the development of a chronic syndrome that is recalcitrant to stepped care interventions.125 The study specific treatment effect heterogeneity analysis would harness these prior observations to potentially create a cumulative burden index for the current patient cohort. Other examples of potential quantitative secondary analyses related to the implementation process assessment are listed in the Table 4.

Sample Size and Power:

Power analyses were conducted using the RMASS program.143 Parameters used in ascertaining power including effect sizes were derived from prior study team investigations.52,62,63

i. Emergency Department Utilization.

The primary health care system intervention target will be group differences in emergency department utilization. In prior investigation, at 3–6 months post-injury, 30% of nurse notification patients versus 17% of care management patients had one or more emergency department visits (13% difference across groups), at 6–9 months post-injury, the differences were 31% nurse notification versus 21% care management (10% difference across groups), and at 12 months post-injury, the differences were 30% nurse notification versus 22% care management (8% difference across groups).62 With the ≥ 95%% follow-up rate provided by EDIE, the probability of a 2-tailed type I error set at 5%, correlation between observations of 0.7, and a similar pattern of emergency department visits as seen in the prior PCORI investigation with 424 total patients (n = 212 in each arm), the power is ≥ 0.80.

ii. Severity of posttraumatic concerns.

In the prior PCORI investigation, at the six month post-injury time point, 74% of nurse notification patients endorsed 1 or more severe concerns versus 52% of care management patients at the six month post-injury study endpoint, for a 22% absolute difference between the two groups.62 For patient-reported outcomes such as the endorsement of one or more severe posttraumatic concern, 20% 12-month attrition is anticipated. With 20% 12-month attrition, 424 patients, the probability of a 2-tailed type I error set at 5%, correlation between observations of 0.7 and a similar pattern of endpoint posttraumatic concern reduction as seen in the prior PCORI investigation (22% reduction in the endorsement of any severe post-injury concern), the power to detect differences in posttraumatic concern severity will be ≥ 0.80.

iii. PTSD symptoms.

In prior comparative effectiveness trials conducted by the study team, at the 12-month time point, collaborative care patients demonstrated a mean PTSD Checklist score of 37.4 (95% Confidence Interval = 34.0–40.7) and usual care patients demonstrated a mean PTSD Checklist score of 42.5 (95% Confidence Interval = 39.3–45.7).52 Projecting these differences to the current investigation, with 20% 12-month attrition, 424 patients, the probability of a 2-tailed type I error set at 5%, correlation between observations of 0.7 and an anticipated effect size = 0.34, the power to detect differences in PTSD symptoms will be ≥ 0.80.

iv. Physical function.

In prior comparative effectiveness trials conducted by the study team, at the 12-month time point, collaborative care patients demonstrated a mean MOS SF-36 PCS scale score of 43.7 (95% Confidence Interval = 41.0–46.5) and usual care patients demonstrated a mean MOS SF-36 score of 41.2 (95% Confidence Interval = 38.5–43.9).52 Projecting these differences to the current investigation, with 20% 12-month attrition, 424 patients, the probability of a 2-tailed type I error set at 5%, correlation between observations of 0.7 and an anticipated effect size = 0.26, the power to detect differences in physical function will be will be ≥ 0.67.

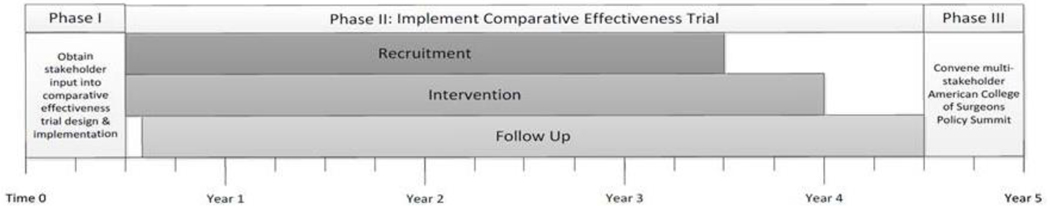

Data from the primary and secondary analyses and implementation process assessment will be used to inform an end-of-study policy summit with the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma.

The summit is an essential component of the project’s deployment-focused model of design and testing and will harness data from the study RAPICE derived implementation process assessment. The end-of-study year 5 policy summit will be modeled along prior study team experiences with American College Surgeons policy summits in the wake of successful comparative effectiveness trials targeting alcohol use problems, PTSD symptoms and patient-centered care.52,60,69,70,144–146 The summit will convene key stakeholders, including the study team policy core that is comprised of health care system administrators and policy advocates, as well as patient stakeholders, PCORI program staff and the study investigators. The co-principal investigators will take the lead in convening the summit.

Discussion

The current investigation, for the first time integrates previously injured peers into a collaborative care intervention that targets multiple patient-centered and policy relevant outcomes for US trauma care systems. Prior investigations have documented that stepped collaborative care interventions can reduce PTSD symptoms and related comorbidity among injury survivors. 64,65 The current investigation integrates peers into the stepped collaborative care model with the goal of establishing that peers have an essential role in the engagement of the most severely impacted and vulnerable physically injured trauma survivors admitted to a safety net level 1 trauma center setting. The study aims to establish that the peer integrated model when compared to a mental health referral enhancement to usual trauma center care, will reduce unnecessary health service utilization and improve outcomes of great relevance to injured patients including reducing injury related concerns and posttraumatic stress symptoms, and improving physical function.

In integrating peers into the collaborative care model the study aims to demonstrate that peers can be a key first step in the engagement of injured trauma survivors in acute care settings. The peer-led integrated approach may enhance patient engagement when compared to routine hospital based mental health intervention delivery. The study also has a goal of demonstrating that the introduction of a peer-integrated inpatient engagement can also enhance coordination between trauma center and primary care and community care settings. Peer engagement skills are believed to derive from their lived experiences and empathic inclinations that have been honed by their own injury recoveries.

The trial incorporates other important innovative features. The primary outcome, EDIE utilization accrues on the intent-to-treat sample without need for patient follow-up. This technological enhancement when combined with 24/7 cell phone contacts and alerts may constitute, a new pragmatic trial standard for both outcome assessment and intervention delivery.147 The study team has observed that the 24/7 cell phone defines a patient-centered approach after traumatic injury. This approach has provided a quick and accessible means for patients to have questions answered and concerns addressed as well as providing the opportunity for effective crisis intervention. Patients are able to text the 24/7 cell phone and promptly receive a response from a clinician (MD and/or MSW). This mode of communication is not only an essential piece of patient engagement, but the study team has observed that these rapid responses can successfully prevent individual emergency department visits and other unnecessary health service utilization. While the 24/7 cell phone does necessitate continuous provider coverage, the study team’s prior investigation demonstrated that patient’s behaviors can be shaped to contact the cell phone during working hours unless an emergency arises during evenings or weekends.7 Acute care providers routinely cover 24/7 shifts; the current investigation is assessing whether the 24/7 cell phone coverage when combined with other collaborative care elements successfully reduces emergency department utilization at the population level.

The investigation has limitations. First the investigation is being conducted at a single level 1 trauma center in the US Pacific Northwest. The results of the study may not generalize to other US and international trauma center settings. Also, the multifaceted nature of the intervention when combined with a sample of just over 400 patients may not yield robust secondary dismantling analyses.129 Furthermore the current comparative effectiveness trial design that compares peer integrated collaborative care with an enhancement to usual mental health care is not designed to assess whether the peer integrated intervention is more effective than collaborative care alone. Future investigations could assess in comparative effectiveness trial designs, peer integrated collaborative care versus standard collaborative care treatments. This pragmatic study is also limited by the inability to fastidiously assess variations in peer communication skills.

The investigation raises a series of further question about whether peers might be able to participate in the delivery of evidence-based behavioral interventions that constitute later stepped care elements. While peer engagement aptitudes may yield the ability to successfully elicit and problem solve post-injury concerns, the study team has observed that some peers may also possess additional capacities for the delivery of behavioral interventions. Collaborative care treatments routinely incorporate evidence-based behavioral interventions.82 A key question becomes, to what extent could peers be trained to assist in the stepped provision of behavioral interventions? The study team has observed that some peers are naturalistically employing basic behavioral intervention skills, including the use of open-ended questions, affirmations, reflective listening, and summaries (OARS) which are the foundation of the motivational interviewing (MI) approach.148 It may be that peer interventionists could be trained to implement more complex MI interventions that successfully target change in risk behaviors. Additionally, it may be that peer interventionists can be trained in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) elements including fundamental behavioral activation skills.149 Future investigations could assess the extent to which peer interventionists can deliver evidence based behavioral interventions, and whether there may be an objective coding process that could be employed to decipher which peer interventionists would be the best fit for the delivery of these interventions. 150–152

Additionally, a substantial body of literature describes the experience of vicarious trauma in acute care and other providers.153–157 Although not a systematic focus of the current investigation, future studies could evaluate peer vicarious trauma experiences.

The trial attempts to integrate new PCORI standards for the delivery of complex interventions while also, attending to key stakeholder perspectives. Ultimately the trial aims to move acute care policy for patient-centered peer integrated interventions. The implementation process assessment is designed to facilitate the overarching implementation science objective of reducing the time lag on implementation of evidence-base intervention integration into health care systems.121 The RAPICE informed implementation process assessment when combined with the end-of-study ACS/COT policy summit aims to impact health care system policy changes related to the intervention within the frame of a single 5 year contract/grant cycle. The ACS/COT is strongly considering the addition of patient-centered care recommendations for the next iteration of the Resources Guide that regulates trauma center care nationally.111 The current pragmatic randomized comparative effectiveness trial has the potential to add empiric data to future ACS/COT recommendations regarding optimal patient-centered care for US trauma care systems.

Figure 2.

Study Phases & Timeline

Funding

This work was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (IHS-2017C1–6151).

Funding & Disclosures

This work was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (IHS-2017C1–6151). All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Trial registration: (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03569878)

CRediT Author Statement

Hannah Scheuer: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration

Allison Engstrom: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Project Administration, Writing – Review & Editing

Peter Thomas: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Funding Acquisition, Writing – Review & Editing

Rddhi Moodliar: Software, Investigation, Resources, Project Administration, Writing – Review & Editing

Kathleen Moloney: Investigation, Resources, Project Administration, Writing – Review & Editing

Mary Lou Walen: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing

Peyton Johnson: Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing

Sara Seo: Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing

Natalie Vaziri: Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing

Alvaro Martinez: Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing

Ronald Maier: Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Writing – Review & Editing

Joan Russo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing

Stella Sieber: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing

Pete Anziano: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing

Kristina Anderson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing

Eileen Bulger: Writing – Review & Editing

Lauren Whiteside: Software, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing

Patrick Heagerty: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing

Lawrence Palinkas: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing

Douglas Zatzick: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.United States President’s Commission on Care for America’s Returning Wounded Warriors. Serve, support, simplify: Report of the President’s Commission on Care for America’s Returning Wounded Warriors. Washington, DC: President’s Commission on Care for America’s Returning Wounded Warriors; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.A National Trauma Care System: Integrating Military and Civilian Trauma Systems to Achieve Zero Preventable Deaths After Injury. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine;2016. 978–0309-44285–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center for Injury Prevention. CDC 2012. In: Office of Statistics and Programming, ed. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Traumatic brain injury: Hope through research. In: Bethesda: National Institute of Health; 2009: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/tbi/detail_tbi.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. https://wisqars-viz.cdc.gov:8006/non-fatal/home. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- 6.PCORI. Improving Healthcare Systems - Cycle 1 2017; http://www.pcori.org/funding-opportunities/improvinghealthcare-systems-cycle-1-2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zatzick D, Russo J, Thomas P, et al. Patient-Centered Care Transitions After Injury Hospitalization: A Comparative Effectiveness Trial. Psychiatry. 2018:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worrell SS, Koepsell TD, Sabath DR, Gentilello LM, Mock CN, Nathens AB. The risk of reinjury in relation to time since first injury: A retrospective population-based study. The Journal of trauma. 2006;60(2):379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez AA, Abdelsattar ZM, Dimick JB, Dev S, Birkmeyer JD, Ghaferi AA. Time-to-readmission and mortality after high-risk surgery. Ann Surg. 2015;262(1):53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merkow RP, Ju MH, Chung JW, et al. Underlying reasons associated with hospital readmission following surgery in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313(5):483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore L, Stelfox HT, Turgeon AF, et al. Rates, patterns, and determinants of unplanned readmission after traumatic injury: A multicenter cohort study. Ann Surg. 2014;259(2):374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabak YP, Sun X, Nunez CM, Gupta V, Johannes RS. Predicting Readmission at Early Hospitalization Using Electronic Clinical Data: An Early Readmission Risk Score. Medical care. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke RE, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, Schnipper JL. Moving beyond readmission penalties: creating an ideal process to improve transitional care. Journal of hospital medicine. 2013;8(2):102–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parry C, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Can’t see the forest for the care plan: a call to revisit the context of care planning. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(21):2651–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Archives of internal medicine. 2006;166(17):1822–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parry C, Min S-J, Chugh A, Chalmers S, Coleman EA. Further Application of the Care Transitions Intervention: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial Conducted in a Fee-For-Service Setting. Home health care services quarterly. 2009;28(2–3):84–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parry C, Mahoney E, Chalmers SA, Coleman EA. Assessing the quality of transitional care: further applications of the care transitions measure. Medical care. 2008;46(3):317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dy SM, Ashok M, Wines RC, Rojas Smith L. A framework to guide implementation research for care transitions interventions. Journal for healthcare quality : official publication of the National Association for Healthcare Quality. 2015;37(1):41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arias SA, Miller I, Camargo CA, Jr., et al. Factors Associated With Suicide Outcomes 12 Months After Screening Positive for Suicide Risk in the Emergency Department. Psychiatric services. 2015:appips201400513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demiris G, Kneale L. Informatics Systems and Tools to Facilitate Patient-centered Care Coordination. Yearbook of medical informatics. 2015;10(1):15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Ogarek J, et al. An Electronic Health Record-Based Intervention to Increase Follow-up Office Visits and Decrease Rehospitalization in Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62(5):865871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rochester-Eyeguokan CD, Pincus KJ, Patel RS, Reitz SJ. The Current Landscape of Transitions of Care Practice Models: A Scoping Review. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. 2016;36(1):117–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zatzick D, Jurkovich GJ, Gentilello LM, Wisner DH, Rivara FP. Posttraumatic stress, problem drinking, and functioning 1 year after injury. Archives of Surgery. 2002;137(2):200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holbrook TL, Anderson JP, Sieber WJ, Browner D, Hoyt DB. Outcome after major trauma: 12-month and 18-month follow-up results from the trauma recovery project. Journal of Trauma. 1999;46(5):765–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michaels AJ, Michaels CE, Moon CH, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder after injury: Impact on general health outcome and early risk assessment. Journal of Trauma. 1999;47(3):460–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zatzick DF, Marmar CR, Weiss DS, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and functioning and quality of life outcomes in a nationally representative sample of male Vietnam veterans. The American journal of psychiatry. 1997;154(12):1690–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zatzick D, Weiss D, Marmar C, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and functioning and quality of life outcomes in female Vietnam veterans. Military medicine. 1997;162(10):661–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zatzick D, Jurkovich G, Fan MY, et al. The association between posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms, and functional outcomes in adolescents followed longitudinally after injury hospitalization. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2008;162(7):642–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler RC. Posttraumatic stress disorder: The burden to the individual and society. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000;61(suppl 5):4–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, et al. The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60(7):427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER. The economic burden of depression in 1990. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 1993;54(11):405–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker E, Unutzer J, Rutter C, et al. Costs of health care use by women HMO members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect. Archives of general psychiatry. 1999;56(7):609–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker EA, Katon W, Russo J, Ciechanowski P, Newman E, Wagner AW. Health care costs associated with postraumatic stress disorder symptoms in women. Archives of general psychiatry. 2003;60(4):369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones ML, Gassaway J, Sweatman WM. Peer mentoring reduces unplanned readmissions and improves self-efficacy following inpatient rehabilitation for individuals with spinal cord injury. The journal of spinal cord medicine. 2019:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffmann DD, Sundby J, Biering-Sørensen F, Kasch H. Implementing volunteer peer mentoring as a supplement to professional efforts in primary rehabilitation of persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2019;57(10):881–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gillard S, Edwards C, Gibson S, Holley J, Owen K. Health Services and Delivery Research. In: New ways of working in mental health services: A qualitative, comparative case study assessing and informing the emergence of new peer worker roles in mental health services in England. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dale J, Caramlau IO, Lindenmeyer A, Williams SM. Peer support telephone calls for improving health. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2008(4):CD006903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valenstein Marcia, Pfeiffer Paul N., Brandfon Samantha, et al. Augmenting Ongoing Depression Care With a Mutual Peer Support Intervention Versus Self-Help Materials Alone: A Randomized Trial. Psychiatric Services. 2016;67(2):236–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heisler M, Vijan S, Makki F, Piette JD. Diabetes control with reciprocal peer support versus nurse care management: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine. 2010;153(8):507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johansson T, Keller S, Winkler H, Ostermann T, Weitgasser R, Sonnichsen AC. Effectiveness of a Peer Support Programme versus Usual Care in Disease Management of Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 regarding Improvement of Metabolic Control: A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. Journal of diabetes research. 2016;2016:3248547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunkeler EM, Meresman JF, Hargreaves WA, et al. Efficacy of nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Archives of family medicine. 2000;9(8):700–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harden PN, Sherston SN. Optimal management of young adult transplant recipients: the role of integrated multidisciplinary care and peer support. Annals of Saudi medicine. 2013;33(5):489–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paul GM, Smith SM, Whitford DL, O’Shea E, O’Kelly F, O’Dowd T. Peer support in type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial in primary care with parallel economic and qualitative analyses: pilot study and protocol. BMC family practice. 2007;8:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dale J, Caramlau I, Docherty A, Sturt J, Hearnshaw H. Telecare motivational interviewing for diabetes patient education and support: a randomised controlled trial based in primary care comparing nurse and peer supporter delivery. Trials. 2007;8:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young AS, Cohen AN, Goldberg R, et al. Improving Weight in People with Serious Mental Illness: The Effectiveness of Computerized Services with Peer Coaches. Journal of general internal medicine. 2017;32(1):4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolfe H, Haller DL, Benoit E, et al. Developing PeerLink to engage out-of-care HIV+ substance users: Training peers to deliver a peer-led motivational intervention with fidelity. AIDS care. 2013;25(7):888–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gassaway J, Jones ML, Sweatman WM, Hong M, Anziano P, DeVault K. Effects of peer mentoring on self-efficacy and hospital readmission following inpatient rehabilitation of individuals with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanks RA, Rapport LJ, Wertheimer J, Koviak C. Randomized Controlled Trial of Peer Mentoring for Individuals With Traumatic Brain Injury and Their Significant Others. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2012;93(8):1297–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]