Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to provide a comprehensive characterization of patients diagnosed with post-COVID-19 condition (PCC) during the first 16 months of use of the International Classification of Diseases revision 10 (ICD-10) diagnosis code U09.9 in Sweden.

Methods

We used data from national registers and primary health care databases for all adult inhabitants of the two largest regions in Sweden, comprising 4.1 million inhabitants (approximately 40% of the Swedish population). We present the cumulative incidence and incidence rate of PCC overall and among subgroups and describe patients with COVID-19 with or without PCC regarding sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities, subsequent diseases, COVID-19 severity, and virus variants.

Results

Of all registered COVID-19 cases available for PCC diagnosis (n = 506,107), 2.0% (n = 10,196) had been diagnosed with PCC using ICD-10 code U09.9 as of February 15, 2022 in the two largest regions in Sweden. The cumulative incidence was higher among women than men (2.3% vs 1.6%, P <0.001). The majority of PCC cases (n = 7162, 70.2%) had not been hospitalized for COVID-19. This group was more commonly female (69.9% vs 52.9%, P <0.001), had a tertiary education (51.0% vs 44.1%, P <0.001), and was older (median age difference 5.7 years, P <0.001) than non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19 without PCC.

Conclusion

This characterization furthers the understanding of patients diagnosed with PCC and could support policy makers with appropriate societal and health care resource allocation.

Keywords: Population-based Cohort study, Post-COVID-19 condition, Patient characteristics, Incidence rate

Introduction

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, many questions remain regarding patients with prolonged symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although several studies have described post-COVID-19 complications and symptoms in different settings and populations (Ayoubkhani et al., 2021; Blomberg et al., 2021; Havervall et al., 2021; Tran et al., 2022; Westerlind et al., 2021), it is difficult to compare results and draw conclusions due to the substantial heterogeneity between studies (Michelen et al., 2021). Discriminating between post-COVID-19 complications, prolonged symptoms of the acute COVID-19 infection, or consequences of possible hospital care, including postintensive care syndrome (Rawal et al., 2017), can be difficult because the clinical presentations may overlap. Furthermore, the terminology of the condition still varies and a widely accepted definition has been lacking (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021b; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2020). The World Health Organization (WHO) recently produced a consensus clinical case definition based on a Delphi process. The term “post-COVID-19 condition” (PCC) was defined as a condition that “occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset, with symptoms that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis” (Soriano et al., 2022). Similar to acute COVID-19, the symptoms and severity of PCC vary widely among affected individuals and can involve multiple organ systems (Crook et al., 2021). PCC can be used to describe the various complications arising from the acute infection, as well as a condition characterized by postviral fatigue. Commonly reported symptoms of PCC include fatigue, dyspnea, cognitive impairment, headache, muscle pain, and cardiac abnormalities, such as chest pain and palpitations (Crook et al., 2021; Groff et al., 2021; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2020; Soriano et al., 2022). The underlying processes of PCC are not fully understood, but various mechanisms for the different symptoms have been proposed, including virus-specific pathophysiologic changes, damage from the inflammatory response to the acute infection, expected sequelae of postcritical illness (Nalbandian et al., 2021), and neuroinflammatory responses in the brain (Edén et al., 2022; Kanberg et al., 2021; Song et al., 2021). The condition has been reported in patients previously hospitalized for acute COVID-19, as well as in patients with mild acute disease (Augustin et al., 2021; Ayoubkhani et al., 2021). Several studies have described PCC as more common in females than males (Augustin et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021a), and the condition does not seem to be restricted to the elderly (Ayoubkhani et al., 2021; Daugherty et al., 2021).

In September 2020, just over a year before the Delphi consensus definition was released, the WHO introduced the PCC diagnosis code (U09.9) within the International Classification of Disease Tenth Revision (ICD-10), and it was quickly adapted in the Swedish version (World Health Organization, 2020a, 2020b). However, some countries including the United Kingdom are instead using the emergency code U07.4 (NHS Digital, 2021) and it was not until October 2021 that the code U09.9 was introduced in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021a). In Sweden, the PCC diagnosis code U09.9 was implemented comparatively early and has been in use since October 16, 2020 (Statistik om tillstånd efter Covid-19 i primärvård och specialiserad vård, 2021). The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare recommends using the PCC diagnosis code to describe a symptom or condition that a physician assesses to be caused by a previous COVID-19 infection. The recommendations do not specify how soon after the acute infection the PCC diagnosis should be applied.

In the current study, we used Swedish hospital data and primary health care data from the two largest regions in Sweden (Region Stockholm and Region Västra Götaland, 2.4 and 1.7 million inhabitants, respectively [Statistics Sweden, 2022]) to present the incidence rate and cumulative incidence of PCC overall and in different subgroups of patients with COVID-19 and to describe the characteristics of all adult patients with COVID-19 with or without a PCC diagnosis during the first 16 months of use of the ICD-10 diagnosis code U09.9 in Sweden.

Methods

Data sources and study cohort

The Swedish Covid-19 Investigation for Future Insights – a Population Epidemiology Approach using Register Linkage (SCIFI-PEARL) project is a register-based cohort study in Sweden, with a comprehensive database for the epidemiological study of COVID-19 in real time (Nyberg et al., 2021). The current study is part of the SCIFI-PEARL research effort, with a unique linkage of data collected from several Swedish national, regional, and quality registers. All citizens in Sweden are assigned a unique personal identity number at birth or at immigration that follows an individual throughout life. This enables us to include a near-complete study population, with nearly 100% coverage of the health care system and a linkage between registers with extremely high accuracy (Ludvigsson et al., 2009). The registers included in the current study are the longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA), National Patient Register (NPR), Cause of Death Register (CDR), National Register of Notifiable Diseases (SmiNet), Swedish Intensive Care Register, National Diabetes Register, and the regional primary health care databases in Stockholm (VAL) and Västra Götaland (VEGA). The LISA database is held by Statistics Sweden and contains sociodemographic and socioeconomic data. The NPR and CDR are both held by the National Board of Health and Welfare; the former includes all inpatient and specialist outpatient health care in Sweden, and the latter includes all deaths in Sweden. The data from NPR includes patients regardless of a completed health care encounter or not. SmiNet is a register of all notifiable communicable diseases held by the Swedish Public Health Agency and includes all positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test results. In Sweden, SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests were mainly performed without inpatient, outpatient, or primary health care visits and positive test results have thus been reported into SmiNet without registration of health care visits in NPR or VEGA/VAL (unless it occurred for a health care reason, in which case a COVID-19 diagnosis code would be present to reflect the positive test and health care need). The VAL and VEGA databases comprise both public and most private primary health care in Region Stockholm and Region Västra Götaland (the largest and second largest regions in Sweden). These two regions encompass approximately 4.1 million inhabitants, corresponding to nearly 40% of the Swedish population (Statistics Sweden, 2022). Although these regions include the two largest cities, as well as the two largest university hospitals in Sweden; these regions also include rural areas. Because PCC, to a large extent, is diagnosed within primary health care in Sweden, the current study was limited to adult (aged 18 years or above) residents in Region Stockholm and Västra Götaland at the study start date (January 31, 2020), for whom we have information from all inpatient, specialist outpatient, and primary health care records (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2022). The university hospitals in these regions have advanced health care and serve as referral centers for other regions; however, we only included residents of these regions and not referred patients. Information from all registers was available until February 15, 2022. Inclusion criteria for this study included having a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test and/or a diagnosis of COVID-19 in any of the registers from the study start date January 31, 2020 until the study end date February 15, 2022. Information on death and emigration was retrieved from CDR and LISA, respectively.

Variables

A COVID-19 case was defined as having the ICD-10 diagnosis COVID-19 (U07.1 or U07.2, as main or secondary diagnosis) in NPR/VEGA/VAL and/or having a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test result registered in SmiNet. The first registration of any of these (for discharge diagnosis in the inpatient part of the NPR, the admission date was used) was defined as the COVID-19 index date. PCC was defined as having the ICD-10 code U09.9 as the main or secondary diagnosis in NPR/VEGA/VAL, and the first occurrence of this code more than 28 days from the COVID-19 index date was defined as the PCC index date (Wanga et al., 2021). A PCC diagnosis within 28 days from the COVID-19 index date (without later PCC diagnoses in the same individual) was interpreted as a probable misclassification relating to the acute infection rather than prolonged symptoms. Follow-up was defined from the COVID-19 index date until the earliest of PCC index date, emigration, death, or the end of the study. We required a minimum follow-up of 114 days (corresponding to the third quartile of follow-up between the COVID-19 index date and PCC index date among patients with PCC diagnosed after the introduction of the PCC diagnosis code) from COVID-19 index date until death, emigration, or the end of the study. Between the COVID-19 index date and the PCC index date, we required a minimum follow-up of 28 days.

In the acute phase of COVID-19, severity was categorized as either hospitalized (highest level of care: requiring intensive care or requiring nonintensive inpatient care) or not hospitalized (requiring neither intensive nor inpatient care). This categorization was based on data from Swedish Intensive Care Register and NPR's inpatient register.

Sociodemographic data, such as age, residency, sex, country of birth, and education, were obtained from the LISA database. Age was defined from birth until the start of the study, January 31, 2020, and categorized into five groups (ages 18-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, and ≥65 years). Countries of birth, except for Sweden, were aggregated to continental regions (categories: Sweden, Asia and Oceania, Africa, Europe except for Sweden, North and South America, and unknown). Education was categorized into primary school level (<10 years), secondary school level (10-12 years), tertiary school level (>12 years), and unknown. Data on comorbidities were retrieved from NPR and National Diabetes Register from January 1, 2015 until December 31, 2019. The comorbidities evaluated were broad definitions of respiratory disease (ICD-codes: J00-J99), cardiovascular disease (ICD-codes: I00-I99), and diabetes (ICD-codes: E10, E11). Data on medical diagnoses from health care encounters after the PCC index date (patients with COVID-19 with PCC) or after 28 days from the COVID-19 index date (patients with COVID-19 without PCC) were retrieved from the national inpatient and outpatient data in NPR and the regional primary health care data in VAL and VEGA, using both main and secondary diagnoses.

Statistical analyses

Characteristics of patients with COVID-19 with or without PCC were analyzed using descriptive statistics and presented as numbers (n), frequencies (%), median, interquartile range (IQR), cumulative incidence (calculated over the whole study period by dividing the number of PCC cases by the number of patients with COVID-19), and incidence rates (calculated by dividing the number of PCC cases by the sum of all COVID-19 cases’ individual follow-up and expressed per 100 person-years). In the analyses regarding cumulative incidence and incidence rate, we used the whole follow-up, as well as a truncated follow-up at 114 days, to account for differences in length of follow-up across the study period. The Mann-Whitney U test and chi-square test were used to test for significance between groups.

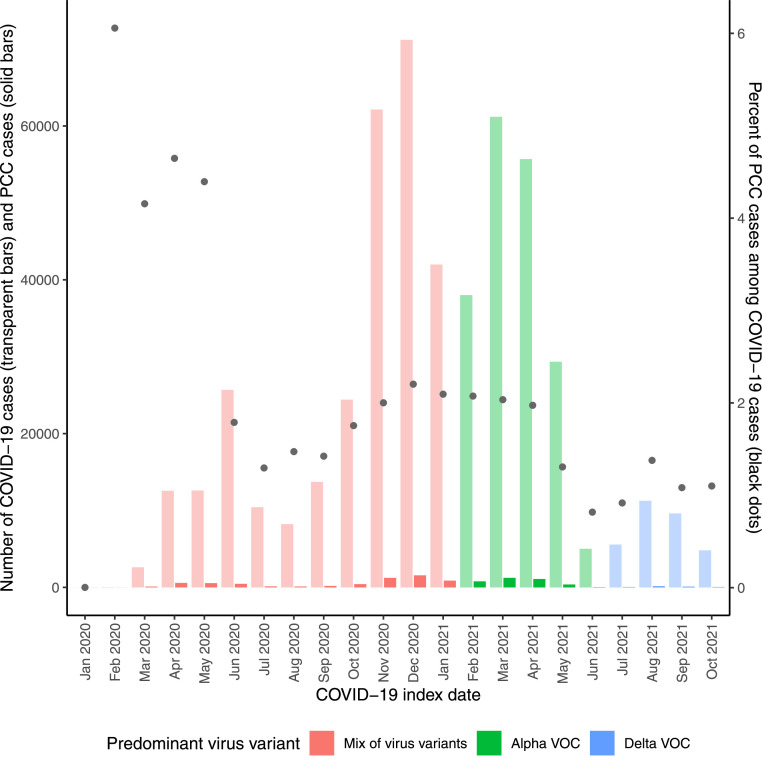

To describe potential variant-specific characteristics, we stratified each patient's COVID-19 index date into distinct time periods corresponding to the dominant virus variant. In Sweden, a combination of virus variants predominated from February 2020 to January 2021, followed by the alpha variant of concern (VOC) from February 2021 to June 2021 and the Delta VOC from July 2021 to December 2021 (Public Health Agency, 2022a).

All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 4.1.3).

Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity analyses with both more and less restriction of the included population were conducted using (i) all individuals diagnosed with PCC, regardless of the time between COVID-19 and PCC diagnosis (n = 11,774), and (ii) all individuals with PCC diagnosis requiring a minimum follow-up between the COVID-19 index date and the PCC index date of 90 days (n = 7375). The 2040 patients with PCC who had a PCC diagnosis but no preceding COVID-19 were not included in the main analyses. However, they are described in the supplemental material.

Results

Cumulative incidence and incidence rate of post-COVID-19 condition

As of February 15, 2022, there were a total of 884,045 COVID-19 cases in the two largest regions in Sweden (Stockholm and Västra Götaland). Of these, 377,938 (42.8%) had a shorter follow-up until death, emigration, or end of the study than 114 days and were thus not included in the study (Supplemental Figure S1). Of the remaining cases, 11,774 individuals had a registered diagnosis of PCC at some time point (2.3%). When counting only individuals with a registered diagnosis of PCC after 28 days from their COVID-19 index date, 10,196 PCC cases remained (age range 18-101 years). Our results therefore show that 2.0 % of all COVID-19 cases in the two largest regions in Sweden have been diagnosed with PCC >28 days after their COVID-19 diagnosis, during the first 16 months of usage of the PCC diagnosis code.

When considering sex, 2.3% of all female COVID-19 cases were diagnosed with PCC, compared with 1.6% of all male COVID-19 cases. The age group 55-64 years had the highest proportion of diagnosed PCC among COVID-19 cases (3.5%), whereas the youngest age group (18-34 years) had the lowest proportion (0.8%). The lowest incidence rate across different regions of birth was 1.7 PCC cases per 100 person-years among individuals born in Sweden. Individuals with tertiary education had the highest incidence rate (2.0 cases per 100 person-years) across education levels. In general, the incidence rates showed a similar pattern as the results based on cumulative incidence (Table 1 ). When truncating the follow-up for all COVID-19 cases (with or without PCC) at 114 days, the patterns for cumulative incidence and incidence rate were similar to the analyses using full follow-up, except for the virus variants (Supplemental Table S1).

Table 1.

Incidence rate and cumulative incidence for post-COVID-19 condition diagnosis among COVID-19 cases stratified according to the initial care requirement for COVID-19. COVID-19 cases from the two largest regions in Sweden, Stockholm and Västra Götaland, including both primary healthcare data and inpatient/outpatient specialist healthcare data, until February 15, 2022.

| Acute COVID-19 care level | Incidence rate (per 100 person-years) |

Cumulative incidence (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-hospitalized | Hospitalized, non-ICU | Hospitalized, ICU | Overall | Non-hospitalized | Hospitalized, non-ICU | Hospitalized, ICU | Overall | |

| Overall | 1.4 | 7.1 | 36.5 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 8.3 | 36.9 | 2.0 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 0.9 | 6.9 | 34.8 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 35.9 | 1.6 |

| Women | 1.8 | 7.4 | 40.8 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 8.7 | 39.2 | 2.3 |

| Age groupa (years) | ||||||||

| 18-34 | 0.7 | 2.9 | 18.3 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 20.9 | 0.8 |

| 35-44 | 1.6 | 8.0 | 46.0 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 9.3 | 41.0 | 2.0 |

| 45-54 | 2.0 | 10.8 | 42.6 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 12.5 | 43.4 | 2.8 |

| 55-64 | 2.1 | 10.5 | 40.4 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 12.2 | 40.9 | 3.5 |

| ≥65 | 0.9 | 5.0 | 31.0 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 5.9 | 31.3 | 2.5 |

| Region of birth | ||||||||

| Africa | 1.0 | 6.0 | 31.1 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 7.4 | 35.9 | 2.0 |

| Asia and Oceania | 1.5 | 6.8 | 34.4 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 8.1 | 36.2 | 2.3 |

| Europeb | 1.6 | 7.3 | 37.8 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 8.7 | 37.6 | 2.7 |

| North and South America | 1.9 | 8.3 | 39.5 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 10.1 | 41.7 | 3.0 |

| Sweden | 1.3 | 7.1 | 36.7 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 8.2 | 36.2 | 1.8 |

| Unknown | 1.8 | 8.2 | 47.2 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 9.3 | 43.0 | 2.5 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Primary school | 1.0 | 4.8 | 31.2 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 5.7 | 31.6 | 1.8 |

| Secondary school | 1.3 | 7.8 | 39.5 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 9.1 | 39.3 | 2.0 |

| Tertiary school | 1.6 | 8.4 | 38.0 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 9.7 | 39.0 | 2.1 |

| Unknown | 0.6 | 3.8 | 26.4 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 4.6 | 28.0 | 1.2 |

| Virus variantc | ||||||||

| Mix of virus variants | 1.3 | 4.7 | 27.1 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 6.6 | 33.3 | 2.2 |

| Alpha VOC | 1.5 | 15.7 | 76.0 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 12.4 | 45.2 | 1.9 |

| Delta VOC | 1.5 | 20.5 | 114.7 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 8.7 | 39.6 | 1.1 |

ICU, intensive care unit; VOC, variant of concern.

Age on study start 31 January 2020.

Not including Sweden.

Virus variants corresponding to specific time periods. In Sweden, a combination of virus variants predominated from February 2020 to January 2021, followed by the Alpha VOC from February 2021 to June 2021, and the Delta VOC from July 2021 to December 2021.

Among patients with COVID-19 with PCC, the median follow-up from the COVID-19 index date until the PCC index date was 87 (IQR = 43-214) days. The median follow-up for patients with COVID-19 without PCC was 403 (IQR = 321-462) days (censored at death, emigration, or end of the study).

Post-COVID-19 condition according to the severity of COVID-19

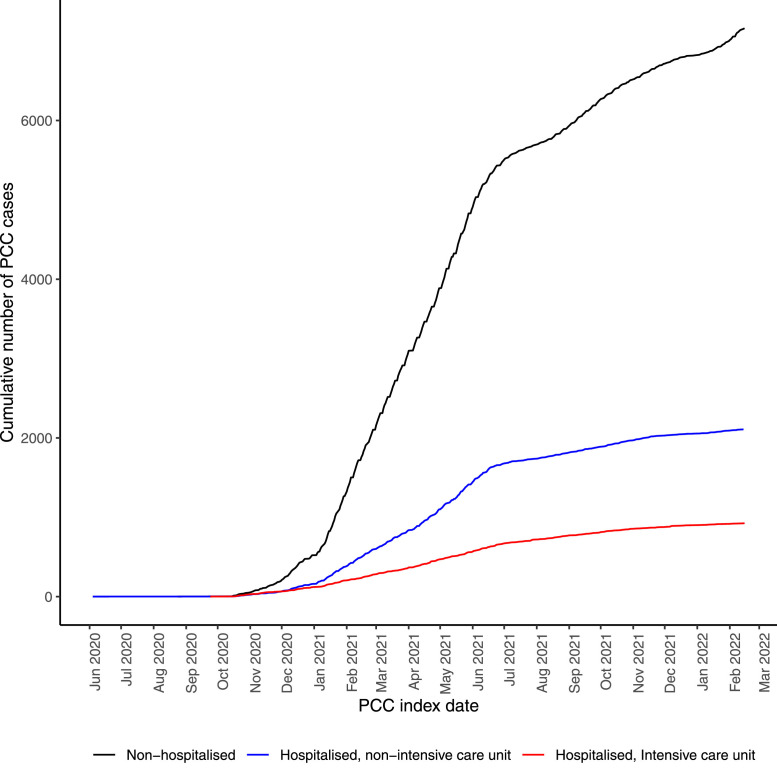

When stratifying COVID-19 cases (with and without PCC) by severity (hospitalized or non-hospitalized), most individuals had not been hospitalized for COVID-19 (with PCC n = 7162, without PCC n = 471,079; Table 2 and Fig 1 ). The proportion of patients with PCC among patients having required intensive care for COVID-19 was 36.9% (COVID-19 cases with PCC n = 926, COVID-19 cases without PCC n = 1583) from the start of the pandemic until the end of study February 15, 2022 (Table 1). The corresponding proportions among patients requiring nonintensive inpatient care and among non-hospitalized patients were 8.3% (with PCC n = 2108, without PCC n = 23,249) and 1.5% (with PCC n = 7162, without PCC n = 471,079), respectively.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for COVID-19 cases with or without PCC diagnosis in the two largest regions in Sweden, Stockholm and Västra Götaland, including both primary healthcare data and inpatient/outpatient specialist healthcare data, until 15 February 2022. Stratified according to the initial care requirement for COVID-19.

| Acute COVID-19 care level | Non-hospitalized |

Hospitalized, non-ICU |

Hospitalized, ICU |

All |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 cases without PCC | COVID-19 cases with PCC | P-value | COVID-19 cases without PCC | COVID-19 cases with PCC | P-value | COVID-19 cases without PCC | COVID-19 cases with PCC | P-value | COVID-19 cases without PCC | COVID-19 cases with PCC | P-value | |

| Total, n | 471,079 | 7162 | 23,249 | 2108 | 1583 | 926 | 495,911 | 10,196 | ||||

| Sex, n (%) | <0.001 | 0.066 | 0.129 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Men | 221,905 (47.1) | 2158 (30.1) | 12,799 (55.1) | 1116 (52.9) | 1124 (71.0) | 630 (68.0) | 235,828 (47.6) | 3904 (38.3) | ||||

| Women | 249,174 (52.9) | 5004 (69.9) | 10,450 (44.9) | 992 (47.1) | 459 (29.0) | 296 (32.0) | 260,083 (52.4) | 6292 (61.7) | ||||

| Agea (years), median (IQR) | 41.4 (30.2-53.3) | 47.1 (38.2-55.4) | <0.001 | 62.8 (48.6-76.3) | 58.2 (49.1-69.0) | <0.001 | 60.2 (49.8-68.2) | 58.3 (50.0-65.9) | 0.028 | 42.2 (30.7-54.5) | 50.3 (40.9-59.1) | <0.001 |

| Age groupa (years), n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 18-34 | 170,635 (36.2) | 1325 (18.5) | 2327 (10.0) | 84 (4.0) | 140 (8.8) | 37 (4.0) | 173,102 (34.9) | 1446 (14.2) | ||||

| 35-44 | 101,371 (21.5) | 1782 (24.9) | 2362 (10.2) | 243 (11.5) | 138 (8.7) | 96 (10.4) | 103,871 (20.9) | 2121 (20.8) | ||||

| 45-54 | 96,420 (20.5) | 2185 (30.5) | 3655 (15.7) | 520 (24.7) | 292 (18.4) | 224 (24.2) | 100,367 (20.2) | 2929 (28.7) | ||||

| 55-64 | 61,233 (13.0) | 1453 (20.3) | 4275 (18.4) | 596 (28.3) | 457 (28.9) | 316 (34.1) | 65,965 (13.3) | 2365 (23.2) | ||||

| 65 or above | 41,420 (8.8) | 417 (5.8) | 10,630 (45.7) | 665 (31.5) | 556 (35.1) | 253 (27.3) | 52,606 (10.6) | 1335 (13.1) | ||||

| Region of birth, n (%) | <0.001 | 0.189 | 0.643 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Africa | 12,653 (2.7) | 138 (1.9) | 1,057 (4.5) | 85 (4.0) | 100 (6.3) | 56 (6.0) | 13,810 (2.8) | 279 (2.7) | ||||

| Asia and Oceania | 54,199 (11.5) | 859 (12.0) | 4095 (17.6) | 359 (17.0) | 316 (20.0) | 179 (19.3) | 58,610 (11.8) | 1397 (13.7) | ||||

| Europeb | 29,041 (6.2) | 498 (7.0) | 2573 (11.1) | 245 (11.6) | 221 (14.0) | 133 (14.4) | 31,835 (6.4) | 876 (8.6) | ||||

| North and South America | 9790 (2.1) | 211 (2.9) | 720 (3.1) | 81 (3.8) | 56 (3.5) | 40 (4.3) | 10,566 (2.1) | 332 (3.3) | ||||

| Sweden | 346,397 (73.5) | 5095 (71.1) | 13,711 (59.0) | 1225 (58.1) | 821 (51.9) | 466 (50.3) | 360,929 (72.8) | 6786 (66.6) | ||||

| Unknown | 18,999 (4.0) | 361 (5.0) | 1093 (4.7) | 113 (5.4) | 69 (4.4) | 52 (5.6) | 20,161 (4.1) | 526 (5.2) | ||||

| Education, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Primary school | 60,615 (12.9) | 642 (9.0) | 5862 (25.2) | 357 (16.9) | 435 (27.5) | 201 (21.7) | 66,912 (13.5) | 1200 (11.8) | ||||

| Secondary school | 194,038 (41.2) | 2815 (39.3) | 9164 (39.4) | 915 (43.4) | 663 (41.9) | 430 (46.4) | 203,865 (41.1) | 4160 (40.8) | ||||

| Tertiary school | 207,551 (44.1) | 3653 (51.0) | 7382 (31.8) | 795 (37.7) | 426 (26.9) | 272 (29.4) | 215,359 (43.4) | 4720 (46.3) | ||||

| Unknown | 8875 (1.9) | 52 (0.7) | 841 (3.6) | 41 (1.9) | 59 (3.7) | 23 (2.5) | 9775 (2.0) | 116 (1.1) | ||||

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Respiratory disease | 47,103 (10.0) | 1027 (14.3) | <0.001 | 5344 (23.0) | 487 (23.1) | 0.925 | 285 (18.0) | 183 (19.8) | 0.299 | 52,732 (10.6) | 1697 (16.6) | <0.001 |

| No respiratory disease | 423,976 (90.0) | 6135 (85.7) | 17,905 (77.0) | 1621 (76.9) | 1298 (82.0) | 743 (80.2) | 443,179 (89.4) | 8499 (83.4) | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 44,440 (9.4) | 787 (11.0) | <0.001 | 8631 (37.1) | 622 (29.5) | <0.001 | 455 (28.7) | 242 (26.1) | 0.173 | 53,526 (10.8) | 1651 (16.2) | <0.001 |

| No cardiovascular disease | 426,639 (90.6) | 6375 (89.0) | 14,618 (62.9) | 1486 (70.5) | 1128 (71.3) | 684 (73.9) | 442,385 (89.2) | 8545 (83.8) | ||||

| Diabetes | 19,026 (4.0) | 298 (4.2) | 0.624 | 4552 (19.6) | 366 (17.4) | 0.015 | 370 (23.4) | 196 (21.2) | 0.220 | 23,948 (4.8) | 860 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| No diabetes | 452,053 (96.0) | 6864 (95.8) | 18,697 (80.4) | 1742 (82.6) | 1213 (76.6) | 730 (78.8) | 471,963 (95.2) | 9336 (91.6) | ||||

| Source of COVID-19 classification, n (%) | 0.053 | <0.001 | 0.007 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Positive PCR testc | 337,302 (71.6) | 5203 (72.6) | 20,658 (88.9) | 2008 (95.3) | 1508 (95.3) | 903 (97.5) | 359,468 (72.5) | 8114 (79.6) | ||||

| Diagnosis only, no positive PCR testd | 133,777 (28.4) | 1959 (27.4) | 2591 (11.1) | 100 (4.7) | 75 (4.7) | 23 (2.5) | 136,443 (27.5) | 2082 (20.4) | ||||

| Number of diagnosese, median (IQR) | 4 (2-8) | 6 (3-10) | 13 (7-22) | 9 (4-15) | 17 (11-25) | 11 (6-16) | 4 (2-9) | 7 (3-12) | ||||

| Follow-up (days), median (IQR) | 400 (321-460) | 94 (43-220) | 432 (333-626) | 61 (38-167) | 457 (343-657) | 118 (57-247) | 403 (321-462) | 87 (43-214) | ||||

| First PCC diagnosis from, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Inpatient care | 138 (1.9) | 199 (9.4) | 159 (17.2) | 496 (4.9) | ||||||||

| Outpatient care | 289 (4.0) | 151 (7.2) | 222 (24.0) | 662 (6.5) | ||||||||

| Primary care | 6735 (94.0) | 1758 (83.4) | 545 (58.9) | 9038 (88.6) | ||||||||

We required a minimum follow-up from COVID-19 index date until death, emigration, or end of study of 114 days. We required a minimum follow-up between COVID-19 index date and PCC index date of 28 days.

ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; PCC, post-COVID-19 condition; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Age on study start January 31, 2020.

Not including Sweden.

From SmiNet, first positive test before PCC diagnosis.

Among PCC cases: n specialist care = 231, n primary care = 1851. Among COVID-19 cases: n specialist care = 6651, n primary care = 129,792.

Main and secondary diagnoses after PCC index date or 28 days after COVID-19 index date.

Fig 1.

The cumulative number of PCC cases until February 15, 2022 according to COVID-19 severity. Study population from the two largest regions in Sweden, Stockholm and Västra Götaland, including both primary healthcare data and inpatient/outpatient specialist healthcare data.

PCC, post-COVID-19 condition.

Among non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19, patients with PCC were more likely women (69.9% vs 52.9%, P <0.001), older (median 47.1 years vs 41.4 years, P <0.001), with a tertiary education (51.0% vs 44.1%, P <0.001) and had a previous respiratory (14.3% vs 10.0%, P <0.001) or cardiovascular (11.0% vs 9.4%, P <0.001) disease than patients with COVID-19 without PCC (Table 2).

In all three categories of COVID-19 severity, a majority were diagnosed with PCC within primary health care (Table 2). The median duration of intensive care among patients with COVID-19 without PCC was 7 (IQR = 3-14) days, and for patients with PCC, it was 11 (IQR = 5-24) days. For patients with COVID-19 without PCC treated in nonintensive inpatient care (excluding the intensive care population), the median duration of care was 6 (IQR = 3-10) days and with PCC 8 (IQR = 4-12) days.

Overall, patients with COVID-19 with PCC had a median of 7 (IQR = 3-12) main and secondary diagnoses after their initial PCC diagnosis (Table 2). The most common diagnosis (COVID-19 diagnoses excluded) was malaise and fatigue (n = 2575) (Table 3a ). For patients with COVID-19 without PCC, the median was 4 (IQR = 2-9), and the most common diagnosis was essential hypertension (n = 65,940) (Table 3b ).

Table 3a.

Number (%) of COVID-19 cases with PCC diagnosed with the most common diagnoses (main and secondary) after PCC index date, stratified according to the initial care requirement for COVID-19. Study population from the two largest regions in Sweden, Stockholm and Västra Götaland, including both primary healthcare data and inpatient/outpatient specialist healthcare data, until February 15, 2022.

| COVID-19 cases with PCC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute COVID-19 care level/ Diagnoses after PCC | Non-hospitalized (n = 7162) | Hospitalized, non-ICU (n = 2108) | Hospitalized, ICU (n = 926) | All (n = 10,196) |

| R53.9 Malaise and fatigue | 1,963 (27.4) | 428 (20.3) | 184 (19.9) | 2,575 (25.3) |

| I10.9 Essential hypertension | 1,132 (15.8) | 768 (36.4) | 441 (47.6) | 2,341 (23.0) |

| R06.0 Dyspnea | 1,254 (17.5) | 513 (24.3) | 339 (36.6) | 2,106 (20.7) |

| R52.9 Pain, unspecified | 1,299 (18.1) | 366 (17.4) | 183 (19.8) | 1,848 (18.1) |

| R05.9 Cough, unspecified | 805 (11.2) | 237 (11.2) | 134 (14.5) | 1,176 (11.5) |

| G93.3 Postviral fatigue syndrome | 919 (12.8) | 145 (6.9) | 76 (8.2) | 1,140 (11.2) |

| J45.9 Unspecified asthma | 631 (8.8) | 272 (12.9) | 112 (12.1) | 1,015 (10.0) |

| R51.9 Headache, unspecified | 821 (11.5) | 130 (6.2) | 50 (5.4) | 1,001 (9.8) |

| G47.9 Sleep disorder, unspecified | 633 (8.8) | 198 (9.4) | 95 (10.3) | 926 (9.1) |

| E11.9 Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus without complications | 301 (4.2) | 366 (17.4) | 236 (25.5) | 903 (8.9) |

Diagnoses from the U-chapter excluded.

ICU, intensive care unit; PCC, post-COVID-19 condition.

Table 3b.

Number (%) of COVID-19 cases without PCC diagnosed with the most common diagnoses (main and secondary) more than 28 days after COVID-19 index date, stratified according to the initial care requirement for COVID-19. Study population from the two largest regions in Sweden, Stockholm and Västra Götaland, including both primary healthcare data and inpatient/outpatient specialist healthcare data, until 15 February 2022.

| COVID-19 cases without PCC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute COVID-19 care level/ Diagnoses after COVID-19a | Non-hospitalized (n = 471,079) | Hospitalized, non-ICU (n = 23,249) | Hospitalized, ICU (n = 1583) | All (n = 495,911) |

| I10.9 Essential hypertension | 53,910 (11.4) | 11,166 (48.0) | 864 (54.6) | 65,940 (13.3) |

| R52.9 Pain, unspecified | 61,056 (13.0) | 4,060 (17.5) | 265 (16.7) | 65,381 (13.2) |

| R53.9 Malaise and fatigue | 36,047 (7.7) | 3,688 (15.9) | 274 (17.3) | 40,009 (8.1) |

| R05.9 Cough, unspecified | 35,254 (7.5) | 4,106 (17.7) | 356 (22.5) | 39,716 (8.0) |

| J06.9 Acute upper respiratory infection, unspecified | 32,453 (6.9) | 1,720 (7.4) | 113 (7.1) | 34,286 (6.9) |

| R10.4X Abdominal pain, unspecified | 29,238 (6.2) | 2,875 (12.4) | 157 (9.9) | 32,270 (6.5) |

| F41.9 Anxiety disorder, unspecified | 23,855 (5.1) | 1,399 (6.0) | 78 (4.9) | 25,332 (5.1) |

| R06.0 Dyspnea | 16,743 (3.6) | 7,578 (32.6) | 758 (47.9) | 25,079 (5.1) |

| G47.9 Sleep disorder, unspecified | 21,337 (4.5) | 2,003 (8.6) | 162 (10.2) | 23,502 (4.7) |

| R51.9 Headache, unspecified | 20,888 (4.4) | 1,341 (5.8) | 75 (4.7) | 22,304 (4.5) |

Diagnoses from the U-chapter excluded.

ICU, intensive care unit; PCC, post-COVID-19 condition.

Diagnoses from healthcare visits from day 29 after COVID-19 index date until end of follow-up.

Post-COVID-19 condition according to specific time periods corresponding to dominant virus variants

Next, using COVID-19 index dates, we grouped the COVID-19 patient population into distinct time periods corresponding to the dominant virus variant at the time of their infection to describe potential virus variant-specific characteristics (Fig 2 and Supplemental Figure S2). The cumulative incidence of PCC was lowest in the Delta VOC period (1.1% vs mix of variants: 2.2% and Alpha VOC: 1.9%) (Table 1, Figure 2). However, the incidence rate of PCC was highest in the Delta VOC period (2.4 per 100 person-years vs mix of variants: 1.7 and Alpha VOC: 2.2). The period corresponding to the Delta VOC had fewer diagnosed PCC cases than the other two periods (n = 363 vs mix of variants: n = 6277 and Alpha VOC: n = 3556) but had a shorter follow-up (Supplemental Table S2). When truncating the follow-up for all COVID-19 cases (with or without PCC) at 114 days, the Alpha VOC period had both the highest incidence rate (4.8 per 100 person-years vs mix of variants: 3.1 and Delta VOC: 3.3) and the highest cumulative incidence (1.5% vs mix of variants: 1.0% and Delta VOC: 1.0%) (Supplemental Table S1).

Fig 2.

On the left y-axis: bar plot of COVID-19 cases (transparent color) and PCC cases (full color) according to COVID-19 index date (month and year). On the right y-axis: the percentage of PCC cases among COVID-19 cases (black dots). Study population from the two largest regions in Sweden, Stockholm and Västra Götaland, including both primary healthcare data and inpatient/outpatient specialist healthcare data, until February 15, 2022. Specific time periods of predominant virus VOC indicated. Early during the pandemic, the polymerase chain reaction testing was very low in Sweden which is reflected in the low incidence of COVID-19 cases. A zoom in on the PCC cases is available in Supplemental Figure S2. PCC, post-COVID-19 condition; VOC, variant of concern.

Sensitivity analyses

In the sensitivity analyses, the proportion of PCC cases to COVID-19 cases was 2.3% when including all PCC cases (n = 11,774) and 1.5% when only including those fulfilling the 90 days restriction (n = 7375). The results regarding the characteristics of these alternative study populations were quite similar (Supplemental Table S3). Most of the PCC cases had a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test (registered in SmiNet) before their PCC diagnosis (66.3%; n = 8114), 17.0% (n = 2082) had received a clinical diagnosis of COVID-19 without a positive PCR test, and 16.7% (n = 2040) had neither a positive PCR test nor a diagnosis (Supplemental Table S4). In the two groups without a positive PCR test, the majority were diagnosed with PCC during the first half of 2021 and the group with diagnosis only had COVID-19 index dates largely during the first months of the pandemic (Supplemental Figures S3 and S4).

Discussion

In the current study, we used Swedish hospital data and primary health care data from the two largest regions in Sweden (4.1 million inhabitants) to present the incidence rate and cumulative incidence and describe characteristics of all adult patients receiving a PCC diagnosis during the first 16 months of use of the ICD-10 diagnosis code U09.9 in Sweden. We show that 10,196 individuals, 2.0 % of all COVID-19 cases, had been diagnosed with PCC during the first 16 months of usage of the PCC diagnosis code. Although the overall cumulative incidence was higher in patients with severe and critical COVID-19, most of the individuals diagnosed with PCC had not been hospitalized for COVID-19. This non-hospitalized group was more likely female, older, had tertiary education, and had a previous respiratory or cardiovascular disease than the patients with COVID-19 without PCC.

A recent systematic review reported a range of PCC prevalence from 9-81% among 31 studies worldwide reporting PCC in widely varying selected COVID-19 study populations (Chen et al., 2022), and a recent umbrella review showed prevalence between 2% and 53% among different selected populations (Nittas et al., 2022). The differences in prevalence between studies seem to a large extent be due to differences in the study populations, follow-up time, the definition of post-COVID-19 condition (one or more symptoms after a certain number of days after COVID-19), the accuracy of diagnosis, the reporting systems, and the capacity of health care systems (Crook et al., 2021). For example, a survey carried out by The Office for National Statistics in the United Kingdom showed that 9.9% of patients with COVID-19 reported at least one symptom 12 weeks after the COVID-19 index date (The Office for National Statistics, 2020). A cohort study from Wuhan (n = 1276), which interviewed patients about their symptoms and conducted physical examinations, laboratory tests, and a 6-minute walk test after 6 and 12 months, found that 49% of patients who previously had been hospitalized due to COVID-19 had at least one sequelae symptom 12 months after the initial infection (Huang et al., 2021b). Assessment of PCC prevalence in truly population-based settings is rare in the previously published studies.

Because Sweden was early in implementing the U09.9 code, we chose to use this diagnosis code to describe the PCC prevalence as a reflection of actual clinical care and diagnosis setting. There are, however, limitations to using U09.9 as a definition of PCC. In the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare guidance, physicians are recommended to use the PCC code U09.9 when a symptom or condition is regarded as being caused by a previous COVID-19 infection. However, no instruction is given regarding how soon after the primary infection the code can be used. According to the case definition recently created by the WHO, PCC could be considered the first 3 months from COVID-19 onset, but 4 weeks have also been used as a definition in earlier studies (Wanga et al., 2021). Therefore, in our main analyses, we did not define 1578 patients as PCC cases because they were only given the PCC code within 28 days after the COVID-19 index date (and not again). Possible explanations for a PCC diagnosis within 28 days of COVID-19 index date include patients not getting tested for SARS-CoV-2 during the acute infection and then receiving a late COVID-19 diagnosis when seeking health care for PCC symptoms (early during the pandemic, the testing capacity in Sweden was very low) or misclassification because there was no specification in Sweden on how soon after COVID-19 a PCC diagnosis could be used or that acute COVID-19 symptoms were misclassified as PCC. It is also difficult to distinguish between PCC and other possible effects of hospitalization and intensive care treatment. This issue is not overcome by using the U09.9 code, and we are therefore unable to discriminate between these conditions in our study. Furthermore, partly due to the wide definition of PCC and the lack of knowledge about the condition, it is likely that not all patients experiencing post-COVID-19 complications are diagnosed with PCC and receive the U09.9 code (Walker et al., 2021). In Sweden, the Public Health Agency recommended the same public health surveillance for COVID-19 in all regions; although, a recent report concluded that Region Stockholm and Västra Götaland had lower test capacity than other regions, especially during 2020 (Almgren and Björk, 2021). Lastly, the diagnosis code has not yet been validated in a Swedish setting. Therefore, the true cumulative incidence of PCC could both be higher and lower than our estimate. Increased use of the WHO-implemented ICD-10 code U09.9 in future studies can hopefully assist in making comparisons between studies, even though many complicating factors will remain.

When considering prevalence data on PCC in different settings and populations, it is important to be aware of the limitations present in the various reports. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare regularly presents nationwide data on the PCC prevalence in Sweden; although, their results are based on aggregated primary health care data. Their latest report estimated that 16,019 individuals received a PCC diagnosis within the public primary healthcare from October 2020 until October 2021 in the whole of Sweden (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2022). In addition, in the report, data from the NPR showed that 5710 individuals received a PCC diagnosis in a hospital or outpatient clinic during the same period (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2022). However, the use of aggregated primary health care data, thus not individual-level data, makes it likely that there is some overlap between data from primary care and hospital/outpatient care. Furthermore, data are gathered from primary care within the public health system only, whereas numbers regarding private primary care are based on estimates. By having access to individual data from NPR, as well as from both public and private primary health care, our results regarding the cumulative incidence of PCC in the two largest regions in Sweden are likely more accurate than the Swedish governmental reports. The fact that the majority of patients with PCC in our study were diagnosed within primary health care (88.6%) further emphasizes the importance of having individual-based data from primary health care.

Our results showed a clear difference in cumulative incidence of PCC, depending on the severity of the primary infection. Among patients having required intensive care for COVID-19, 36.9 % went on to receive a PCC diagnosis, whereas the proportion of PCC diagnoses among non-hospitalized patients was only 1.5%. This is in line with previous reports showing a possible association between more severe acute infection and an increased risk of developing PCC (Huang et al., 2021a; Sudre et al., 2021). Furthermore, the high numbers of PCC among patients requiring intensive care for COVID-19 likely include patients experiencing the consequences of hospital care, including the so-called postintensive care syndrome (Rawal et al., 2017). Consistent with previous reports (Augustin et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021a; National Board of Health and Welfare, 2022), we also showed that females were more likely to receive a PCC diagnosis than men: 2.3% and 1.6%, respectively. There was also a difference across age groups, and the highest proportions of PCC were seen at ages 55-64 years. The different health-seeking behaviors between the sexes, as well as between different age groups, might explain some of these differences in PCC prevalence, both in terms of getting tested for SARS-CoV-2 during the initial infection and in seeking health care when experiencing symptoms of PCC (Thompson et al., 2016). Furthermore, patients initially hospitalized for COVID-19 might be more prone to continue seeking medical care after hospitalization, and there might also be different patterns of health-seeking behavior in the other subgroups evaluated in this study. One inevitable limitation to diagnosis-based register studies, such as the current study, is that these types of health-seeking behavior differences across subgroups might introduce self-selection bias. Nevertheless, the results presented here will be relevant and useful for assessing the future impact of PCC on health care as a reflection of real-world health care practices.

It is still unclear whether different SARS-CoV-2 variants have the same potential to cause sequelae symptoms and PCC after the initial infection and if there are any virus variant-specific characteristics of the condition. The current study shows that the cumulative incidence was lower in the Delta VOC period than in the other periods, but the incidence rate was higher. This might be due to the shorter follow-up in the Delta VOC period, and considering that the study end date was February 15, 2022 and that we required a minimum follow-up of 114 days, individuals whose COVID-19 index date was closer to the end of the study had less time to develop PCC. Hence, the results regarding PCC among patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 when the Delta VOC was dominant (n = 363) in Sweden (July 2021 until December 2021) must be interpreted cautiously. When accounting for differences in length of follow-up using a truncated follow-up, we show that the Alpha VOC period had a higher incidence rate and cumulative incidence than the other two periods. PCR confirmation of COVID-19 (84.6%) was comparatively low early in the period when a mix of virus strains was circulating due to the limited test capacity in Sweden during the first months of the pandemic.

Early in the pandemic, Sweden chose an approach to mitigate the pandemic that was different from most other countries, including the Nordic countries. The strategy was based on voluntary measures and personal responsibility of the Swedish population (Ludvigsson, 2022). A commission concluded in 2022 that although the overall mortality (2020-2021) was lower than in many other countries, earlier and more extensive measures should have been undertaken early on during the pandemic (Ludvigsson, 2022). Vaccination of individuals in risk groups started in late 2020 and early 2021 and continued on a large scale for the whole adult population in the second quarter of 2021 (Public Health Agency, 2022b). In the middle of the summer 2021, around 70% of the population had taken their first dose, meaning that the risk of severe COVID-19 had changed by the end of the study period.

Our study has several strengths: it is population-based and includes a near-complete data set from inpatient, outpatient, and primary health care data. Moreover, we used individual-level data and can thus distinguish individuals appearing in more than one register and avoid data duplication or overlap. Importantly, we included data from both public and private primary health care.

In conclusion, we present data on the estimated cumulative incidence of PCC in a truly population-based setting in the two largest regions in Sweden, together with a detailed characterization of the patient population diagnosed with PCC during the first 16 months of use of the ICD-10 diagnosis code U09.9. This knowledge is important to further the understanding of this emerging patient group. However, more research is urgently needed to improve the diagnosis and clinical care for these patients.

Declaration of competing interest

MB has funding by research grants from Svenska sällskapet för Medicinsk Forskning (SSMF), Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare (FORTE), and Mary von Sydow's foundation; SL has funding by a Swedish government research grant through the ALF-agreement; MG has funding by a Swedish government research grant through the ALF-agreement and from Formas, Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development; MG has received personal honoraria from Amgen, Biogen, BMS, Gilead, GSK/ViiV, Janssen-Cilag, MSD, Novocure, and Novo Nordic and participated on a scientific advisory board for Astra Zeneca (DSMB), Gilead, GSK/ViiV, Pfizer, and MSD; FN has funding for the submitted work by a Swedish government research grant through the ALF-agreement and from Formas, Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development; FN has funding through research grants from the Swedish Research Council, Swedish Heart-lung foundation, SciLifeLab / Knut & Alice Wallenberg Foundation, and Swedish Social Insurance Agency; FN had a previous employment at Astra Zeneca until 2019 and owns some Astra Zeneca shares; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Acknowledgments

Funding

MB is supported by a research grant from Svenska Sällskapet för Medicinsk Forskning SSMF (PD20-0012) and from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare, (FORTE) (2022-00444). The underlying SCIFI-PEARL study has funding by a Swedish government grant through the ALF-agreement (ALFGBG-938453, ALFGBG-971130) and from Formas, a Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development (2020-02828). MG received research grants from the ALF-agreement (ALFGBG-965885) and Formas (2021-06545). The funders had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Ethical approval

The Swedish Ethical Review Authority approved the study (Dnr: 2020-01800).

Author contributions

The work described in this article was conceptualized and designed by MB, SL, and FN. All authors made substantial contributions to the acquisition (AS, HL, MG, FN), analysis (MB, JM, HL), or interpretation (MB, SL, LL, DG, JM, AS, HL, MG, FN) of data for the work. MB, SL, and LL drafted the manuscript; all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content and gave their final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. MB and FN directly accessed and verified the underlying data reported in the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2022.11.021.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Almgren M, Björk J. Kartläggning av skillnader i regionernas insatser för provtagning och smittspårning under coronapandemin, 2021, https://coronakommissionen.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/underlagsrapport-m-almgren-kartlaggning-av-skillnader-i-regionernas-insatser-for-provtagning-och-smittsparning-under-coronapandemin.pdf; (accessed 01 September 2022).

- Augustin M, Schommers P, Stecher M, Dewald F, Gieselmann L, Gruell H, et al. Post-COVID syndrome in non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19: a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;6 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoubkhani D, Khunti K, Nafilyan V, Maddox T, Humberstone B, Diamond I, et al. Post-covid syndrome in individuals admitted to hospital with Covid-19: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021;372:n693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg B, Mohn KG, Brokstad KA, Zhou F, Linchausen DW, Hansen BA, et al. Long COVID in a prospective cohort of home-isolated patients. Nat Med. 2021;27:1607–1613. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New ICD-10-CM code for post-COVID Conditions, following the 2019 Novel coronavirus (COVID-19). p. 2021. Effective, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/announcement-new-icd-code-for-post-covid-condition-april-2022-final.pdf, 2021a (accessed 28 June 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Post-COVID conditions: information for healthcare providers. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/post-covid-conditions.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fhcp%2Fclinical-care%2Flate-sequelae.html, 2021b (accessed 28 June 2022).

- Chen C, Haupert SR, Zimmermann L, Shi X, Fritsche LG, Mukherjee B. Global prevalence of post COVID-19 condition or long COVID: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:1593–1607. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, Young M, Edison P. Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:n1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty SE, Guo Y, Heath K, Dasmariñas MC, Jubilo KG, Samranvedhya J, et al. Risk of clinical sequelae after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021;373:n1098. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edén A, Grahn A, Bremell D, Aghvanyan A, Bathala P, Fuchs D, et al. Viral antigen and inflammatory biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid in patients with COVID-19 infection and neurologic symptoms compared with control participants without infection or neurologic symptoms. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.13253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groff D, Sun A, Ssentongo AE, Ba DM, Parsons N, Poudel GR, et al. Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havervall S, Rosell A, Phillipson M, Mangsbo SM, Nilsson P, Hober S, et al. Symptoms and functional impairment assessed 8 months after mild COVID-19 among health care workers. JAMA. 2021;325:2015–2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Yao Q, Gu X, Wang Q, Ren L, Wang Y, et al. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398:747–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanberg N, Simrén J, Edén A, Andersson LM, Nilsson S, Ashton NJ, et al. Neurochemical signs of astrocytic and neuronal injury in acute COVID-19 normalizes during long-term follow-up. EBiomedicine. 2021;70 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24:659–667. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigsson JF. How Sweden approached the COVID-19 pandemic: summary and commentary on the national commission inquiry. Acta Paediatr. 2022 doi: 10.1111/apa.16535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelen M, Manoharan L, Elkheir N, Cheng V, Dagens A, Hastie C, et al. Characterising long COVID: a living systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Board of Health and Welfare . National Board of Health and Welfare; Sweden: 2022. Statistik om postcovid i primärvård och specialiserad vård. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service. Digital. COVID-19 and ICD-10. https://hscic.kahootz.com/t_c_home/view?objectId=19099248, 2021 (accessed 25 May 2022).

- National Board of Health and Welfare . Ministry of Health and Social Affairs; Sweden: 2021. Statistik om tillstånd efter Covid-19 i primärvård och specialiserad vård. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; London: 2020. COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19 [NICE guideline] NG188. [Google Scholar]

- Nittas V, Gao M, West EA, Ballouz T, Menges D, Wulf Hanson S, et al. Long COVID through a public health lens: an umbrella review. Public Health Rev. 2022;43 doi: 10.3389/phrs.2022.1604501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg F, Franzén S, Lindh M, Vanfleteren L, Hammar N, Wettermark B, et al. Swedish Covid-19 investigation for future insights - A population epidemiology approach using register linkage (SCIFI-PEARL) Clin Epidemiol. 2021;13:649–659. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S312742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency. Statistik om SARS-CoV-2 virusvarianter av särskild betydelse. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/smittskydd-beredskap/utbrott/aktuella-utbrott/covid-19/statistik-och-analyser/sars-cov-2-virusvarianter-av-sarskild-betydelse/, 2022a (accessed 28 June, 2022).

- Public Health Agency. Vaccinationer mot Covid-19 i Sverige. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/6df5491d566a44368fc721726c274301, 2022b (accessed 01 September 2022).

- Rawal G, Yadav S, Kumar R. Post-intensive care syndrome: an overview. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5:90–92. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2016-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song WJ, Hui CKM, Hull JH, Birring SS, McGarvey L, Mazzone SB, et al. Confronting COVID-19-associated cough and the post-COVID syndrome: role of viral neurotropism, neuroinflammation, and neuroimmune responses. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:533–544. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00125-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, Relan P, Diaz JV. WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:e102–e107. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00703-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Sweden. Folkmängd i riket, län och kommuner 31 December 2021 och befolkningsförändringar 2021. https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/befolkning/befolkningens-sammansattning/befolkningsstatistik/pong/tabell-och-diagram/helarsstatistik–kommun-lan-och-riket/folkmangd-i-riket-lan-och-kommuner-31-december-2021-och-befolkningsforandringar-2021/, 2022 (accessed 28 June 2022).

- Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, Graham MS, Penfold RS, Bowyer RC, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27:626–631. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Office for National Statistics. The prevalence of long COVID symptoms and COVID-19 complications. https://www.ons.gov.uk/news/statementsandletters/theprevalenceoflongcovidsymptomsandcovid19complications, 2020 (accessed 28 June 2022).

- Thompson AE, Anisimowicz Y, Miedema B, Hogg W, Wodchis WP, Aubrey-Bassler K. The influence of gender and other patient characteristics on health care-seeking behaviour: a QUALICOPC study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:38. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0440-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran VT, Porcher R, Pane I, Ravaud P. Course of post COVID-19 disease symptoms over time in the ComPaRe long COVID prospective e-cohort. Nat Commun. 2022;13:1812. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29513-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AJ, MacKenna B, Inglesby P, Tomlinson L, Rentsch CT, Curtis HJ, et al. Clinical coding of long COVID in English primary care: a federated analysis of 58 million patient records in situ using OpenSAFELY. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;71:e806–e814. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2021.0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanga V, Chevinsky JR, Dimitrov LV, Gerdes ME, Whitfield GP, Bonacci RA, et al. Long-term symptoms among adults tested for SARS-CoV-2 - United States, January 2020–April 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1235–1241. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7036a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerlind E, Palstam A, Sunnerhagen KS, Persson HC. Patterns and predictors of sick leave after Covid-19 and long Covid in a national Swedish cohort. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1023. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Emergency use ICD codes for COVID-19 disease outbreak. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases/emergency-use-icd-codes-for-covid-19-disease-outbreak, 2020a (accessed 28 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. Updates 3 & 4 in relation to COVID-19 coding in ICD-10. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/classification/icd/covid-19/covid-19-coding-updates-3-4-combined.pdf?sfvrsn=39197c91_3, 2020b (accessed 28 June 2022).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.