Abstract

Onchocerca lupi is a filarial nematode that causes ocular onchocercosis in canines globally including North America and areas of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Reported incidence of this parasite in canines has continued to steadily escalate since the early 21st century and was more recently documented in humans. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) of this parasite can provide insight into gene content, provide novel surveillance targets, and elucidate the origin and range expansion. However, past attempts of whole genome sequencing of other Onchocerca species reported a substantial portion of their data unusable due to the variable over-abundance of host DNA in samples. Here, we have developed a method to determine the host-to-parasite DNA ratio using a quantitative PCR (qPCR) approach that relies on two standard plasmids each of which contains a single copy gene specific to the parasite genus Onchocerca (major body wall myosin gene, myosin) or a single copy gene specific to the canine host (polycystin-1 precursor, pkd1). These plasmid standards were used to determine the copy number of the myosin and pkd1 genes within a sample to calculate the ratio of parasite and host DNA. Furthermore, whole genome sequence (WGS) data for three O. lupi isolates were consistent with our host-to-parasite DNA ratio results. Our study demonstrates, despite unified DNA extraction methods, variable quantities of host DNA within any one sample which will likely affect downstream WGS applications. Our quantification assay of host-to-parasite genome copy number provides a robust and accurate method of assessing canine host DNA load in an O. lupi specimen that will allow informed sample selection for WGS. This study has also provided the first whole genome draft sequence for this species. This approach is also useful for future focused WGS studies of other parasites.

Introduction

Onchocerca lupi is a filarial nematode that represents an emerging threat to wildlife, companion animals, and humans [1]. First described in the Republic of Georgia in the periocular tissues of a wolf (Canis lupus lupus) in 1967 [2], it was only recently detected in domesticated canines and felines in North America and the Old World [3–5]. As there is no current commercial diagnostic test for this parasite, O. lupi infections are confirmed based on ocular nodules on eyelids, conjunctiva, and sclera [6–8]. If nodules are not present but O. lupi infection is suspected, the only diagnostic tool currently available is through the detection of microfilariae in skin [9]. However, this invasive skin biopsy is heavily dependent on the biopsy location and the density of microfilaria [10] making this tool highly unreliable.

Onchocerca lupi poses a new public health and veterinary threat, but the genomic mechanisms that drive the evolution of pathogenicity are largely unexplored. Because of the growing number of both canine and human cases of O. lupi, it is imperative to understand the genomic content of this parasite to identify appropriate and O. lupi specific biomarker targets, mitigation strategies, and effective treatments. To date, there are no evidence-based treatment protocols for adult O. lupi nematode infections. Current treatment methods are based mostly on O. volvulus and involve the anti-microfilaricidal drug ivermectin concurrently given with the antibiotic doxycycline [11, 12]. However, there is no cure for this filarial nematode, highlighting the dire need for novel treatment therapies for this emerging parasite; one way to achieve this is by characterizing the whole genome of the parasite itself. Previous research has shown the production of draft genomes for filarial nematodes has significantly contributed to the identification of potential new drug treatment options [13, 14]. To date, there are no studies investigating the genomic landscape of O. lupi beyond mitochondrial genes. However, a recent study involving the closely related Onchocerca ochengi, a cattle parasite, described the sequencing of 20 whole genome samples and subsequently reported that data from 10 of those samples were majority host (cattle) DNA and therefore unusable [15]. To circumvent costly sequencing of majority host DNA in O. lupi samples, we have designed a qPCR to quantify the ratio of O. lupi parasite DNA and Canis lupus familiaris host DNA within a parasite sample. Here, we implemented a previously published [16] approach based on single copy genes unique to the parasite (myosin) or the host (polycystin-1 precursor, pkd1) [17]. Additionally, the highly conserved pkd1 gene target can be used to quantify DNA ratios from coyote, wolf, and dingo samples in addition to canine hosts. This approach is crucial for informed sample selection for whole genome sequencing of parasitic nematode samples that will allow for the development of novel, species-specific biomarkers for pathogen tracking, identify potential treatment targets, and determine population structure and evolution of this newly emerging zoonotic parasite. Additionally, this study produced the first draft genome for this species using this approach.

Materials and methods

Single copy gene target selection

The polycystin-1 precursor (pkd1) canine gene (accession no. AF483210) was identified as a conserved, single copy gene in a previous study [17] and was selected for use as the host locus based on these criteria. Pre-aligned pkd1 canine gene sequences (n = 4) (S1 Table) were downloaded from the NCBI nucleotide database [18] and used for primer design in the online software Primer3 [19]. The parasite locus, major body wall myosin gene, was chosen as it was a highly conserved, single copy gene across the genus Onchocerca. Briefly, the genomic sequences for 4 Onchocerca species (O. ochengi, O. flexuosa, O. volvulus, and O. lupi) (S2 Table) were aligned to predicted coding sequences pulled from O. ochengi (accession no. ASM90053720v1) reference genome using BWA v0.7.17-r1188 [20] within the NASP v1.2.0 pipeline [21]. Nucmer v3.1 [22] was used to identify single copy coding regions within the reference genome. Coding regions that were highly conserved across all Onchocerca genomes were considered for primer design using Primer3 software.

Sample collection and DNA isolation

Single copy host and parasite genes were amplified from a pre-established O. lupi PCR-positive canine skin biopsy sample collected from northern Arizona, United States under IACUC of Northern Arizona University approved protocol 19–016. Genomic DNA was extracted from a complex, biopsied canine skin sample using the Qiagen Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) following overnight lysis, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. O. lupi DNA was confirmed using previously published methods [1]. Additionally, four adult O. lupi isolates from four dogs in Flagstaff, Arizona; Phoenix, Arizona; and Albuquerque, New Mexico (n = 2) were used in this study. Adult worms contained within host tissue nodules were isolated using a 0.3% collagenase enzymatic digestion to remove host tissue and subsequently washed four times with PBS [11]. Genomic DNA was extracted using a modified filarial parasite genomic DNA isolation protocol [23] as follows: samples underwent three freeze/thaw cycles consisting of three minutes in liquid nitrogen followed by three minutes at 80°C. Afterward, samples were transferred to 2mL round bottom tubes with a single 5mm stainless steel bead, 250μL PBS, and 100μL lysis buffer. Using a vortex mixer with a special adapter, samples were vortexed on max speed for 45 min with rotation of the tubes every 10 minutes. Immediately following bead beating, 30μL of 10% SDS was added to each sample along with 2μL of 2−mercaptoethanol and 60μL of proteinase K (20mg/μL). Samples were incubated overnight at 65°C followed by an RNase A treatment which consisted of adding 15μl of RNase A (10mg/mL) to each sample and incubated at 37°C for one hour. The Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen) was used following the manufacturer’s recommendations with one exception; buffer AL was added at a 1:1 ratio with the sample volume. Extracted DNA was stored at -20°C until further use.

Cloning of the pkd1 and the myosin gene

The pkd1 and myosin plasmid construct genes were amplified from the O. lupi PCR-positive canine skin biopsy sample using the thermocycler conditions below:

pkd1: 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 60°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 1:30 min and a final extension of 72°C for 1 min.

myosin: 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 60°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 1:30 min and a final extension of 72°C for 1 min.

gDNA from a PCR-positive O. lupi canine skin sample was used as a template for both reactions and no template controls were included for all PCRs. Primer sequences for both the plasmid construct amplicons as well as the SYBR assay targets are given in Table 1. Non-specific banding was observed in the plasmid construct pkd1 gene PCR; therefore, the PCR product just below the 1000base marker was extracted from a 2% agarose gel and purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). Both the pkd1 and myosin amplified product were ligated into a TOPO TA vector (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmid constructs were amplified through transformation into One Shot TOP 10 chemically competent E. coli (Invitrogen) followed by overnight culturing. To ensure plasmid stability, ten individual colonies were re-streaked on LB containing 50mg/mL kanamycin and incubated overnight at 37°C. Cells were harvested and the cloned plasmid was extracted using the QIAquick Mini Kit (Qiagen). Gene inserts were confirmed for each plasmid by restriction digest using ECORI and sequenced directly with capillary electrophoresis using BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit on a 3130 Genetic Analyzer platform (Applied Biosystems) using M13 Forward and M13 Reverse (M13 FR) vector primer sites for all replicates. All sequences were queried with blastn [24] against the NCBI Nucleotide database (nt) to confirm the composition of gene targets within each plasmid.

Table 1. Primer sequences for quantitative and conventional PCR for both host and parasite used in this study.

| Target | Goal | Sequence 5’-3’ | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pkd1 | plasmid | F: GGCCATAGTCAATTCCAGCG | 951 |

| R: CCCAGATCATTGAAGGCACG | |||

| pkd1 | qPCR | F: ACATAGACCGCGGCTTCG | 336 |

| R: TGACCTGCAGATGGAAGCG | |||

| myosin | plasmid | F:GGATATCGCTGGATTCGAGA | 991 |

| R:CGGTCATGCTATCATGGAAA | |||

| myosin | qPCR | F:AACGCGAAGGTATTCAGTGG | 339 |

| R:GATCATTCGCTTTAGATTGTTTCA |

qPCR SYBR green based assay

Internal primers for use with SYBR dye-based qPCR assays were designed using Primer3 software for both pkd1 and myosin genes. All qPCR assays were performed on an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 12. Concentrations for the plasmid preps were measured using the Qubit dsDNA BR assay kit (Invitrogen). A fresh tenfold serial dilution ranging over six logs (106 to 10 gene copy number (GCN)) of both the pTOPO-pkd1 and pTOPO-myosin plasmids were used to generate each standard curve (Table 1). A 10μL qPCR mixture was prepared using the PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Invitrogen): 1X PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix, 0.3μM forward and reverse primers, and 2μL template DNA or plasmid standards. The thermal cycling protocol was as follows:

95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min.

Following amplification, a melting curve analysis was used to confirm reaction specificity; a single and specific peak was generated for each primer pair. Both negative and no-template controls were performed in triplicate.

Estimation of gene copy number

The gene copy number (GCN) of both plasmids used in this study were calculated using the following equation [25]:

DNA length represents the combined length of the plasmid (3,931 bp) and corresponding insert (pkd1 = 951 bp, myosin = 991 bp). The DNA amount represents the plasmid concentration multiplied by the volume used. Standard curves were generated using copy number vs. Cq value for all six plasmid dilutions in triplicate for both pTOPO-pkd1 and pTOPO-myosin plasmids.

Host and parasite DNA ratio calculations

GCNs estimated from the pTOPO-pkd1 and pTOPO-myosin standard curves were used to calculate total host and parasite DNA in four O. lupi samples. Given the estimated genome sizes of host (2370Mb) and parasite (150Mb) as well as the estimated gene copy numbers, we used the above equation to solve for the “DNA amount” in grams. The following equation was used to calculate host to parasite DNA ratio:

DNA sequencing and analysis

Four O. lupi DNA samples extracted from adult nematodes were prepared for paired-end, whole genome sequencing on either a MiSeq, HiSeq, or NextSeq using previously described methods [26]. To aide in the creation of a reference genome, sample Olupi_Ro2020_NM was sequenced on both Illumina NextSeq and MiSeq instruments. Raw reads were trimmed for adapter sequences using trimmomatic v0.39 [27]. The first draft genome assembly for this species was created using SPAdes v3.15.3 [28]. Assembly errors were corrected with eight rounds of pilon [29]. Reads were globally aligned to both the dog reference genome (accession number GCA_008641055.1) and our O. lupi draft assembly (BioProject PRJNA802584) using bowtie2 v.2.4.2 [30] default parameters with the addition of -I 125, and -X 1800. The number of aligned reads to each reference genome were calculated using PICARD tools v1.125 [31].

Results

Melting temperature and standard curve analysis

Two plasmid standards each containing a highly conserved gene specific to the canine host (951 bp fragment of the pkd1 gene) or the parasite (991 bp fragment of the myosin gene) were constructed. The amplicon targets used for the qPCR assay are nested within larger gene fragments (Table 1). These nested primers produced a single amplicon for each gene target, pkd1 (336bp) and myosin (339bp) (S1 Table). Melting curve analysis for both pkd1 and myosin amplicons revealed single peak temperature at 92°C and 81°C respectively for the standard plasmid DNA and the 3 biological samples.

Standard curve slopes were -3.499 for pkd1 plasmid and -3.509 for the myosin plasmid. Regression analysis was used to evaluate prediction accuracy which resulted in R2 values of 0.999 (pkd1) and 1.0 (myosin) and standard curve efficiencies of 93.11% and 92.74%, respectively. No template controls were included in each run to ensure PCRs were contamination-free.

Host-to-parasite DNA ratio predictions

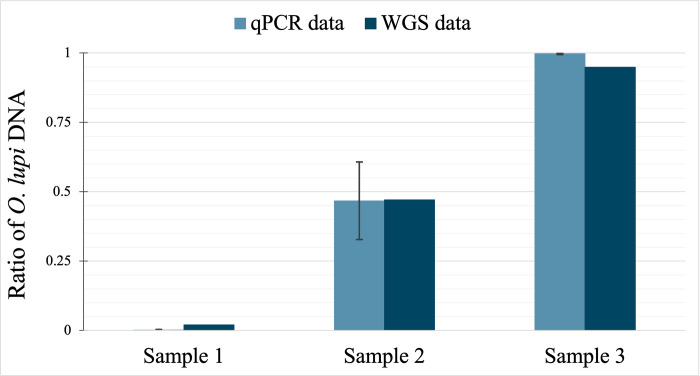

Using DNA extracted from three O. lupi isolates, host and parasite DNA ratios were estimated using LupiQuant. Standard curves were plotted using the pkd1 and myosin plasmid constructs; GCN of the host and parasite DNA per sample were calculated using the Cq values in reference to the standard curves. The host to parasite DNA ratio was calculated using equation 2. In the three O. lupi samples used for quantification, parasite DNA (%) ranged from 0.12% to 46.75% to 99.74% (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Comparison of Onchocerca lupi percentage from three biological canine samples.

Samples were screened using LupiQuant which estimated O. lupi percentages within each sample. Whole genome sequences of O. lupi samples were aligned to O. lupi reference genome (BioProject PRJNA802584) to compare LupiQuant ratios. Error bars represent the range of O. lupi percentages based on host and parasite technical replicates.

Whole genome sequencing and DNA ratios

Aligned read counts were tallied and aligned read percentages were compared with the predicted host-to-parasite DNA ratios (Table 2). The WGS data (BioProject PRJNA802584) for three samples showed the parasite DNA alignment (% of total reads) ranged between 1.98% to 47.15% to 94.45% (Fig 1).

Table 2. qPCR predicted host-to-parasite DNA ratios, WGS read alignment percentages, and from three adult O. lupi nematodes.

*Reported ratio is not based on total read numbers.

| Sample | Predicted DNA ratio (host to parasite) | WGS alignment ratio (host to parasite) |

|---|---|---|

| Isolate 1 | 99.88: 0.12 | 99.48: 1.98 |

| Isolate 2 | 53.25: 46.75 | 52.85: 47.15 * |

| Isolate 3 | 0.26: 99.74 | 3.00: 94.45 |

Discussion

The ability to produce high quality sequencing data from zoonotic parasites has direct and immediate implications for public and veterinary health. However, the variable amount of background host DNA in parasitic nematode samples can greatly reduce and sometimes entirely eclipse parasite signal [11] in whole genome sequencing. To provide an estimate of nematode signal in complex samples, we designed a robust and accurate qPCR assay (LupiQuant) with separate amplification and detection of parasite and host markers. The assay consists of cloned plasmid standards, each containing a single copy gene target from either the host or parasite. qPCR can then detect the host/parasite ratio that can be used to guide WGS efforts. Correlating WGS data with LupiQuant results showed a strong correlation (Fig 1), demonstrating the power of our approach.

One potential limitation to our approach is the presence of unexpected DNA in the sample (i.e., other pathogens co-infecting the host, contamination). For example, in one isolate from Flagstaff, Arizona, LupiQuant predicted the host-to-parasite DNA ratio as 53.25% host DNA and 46.75% parasite DNA. When the data were mapped against reference genomes, ~63% of the reads failed to align against dog or O. lupi references. When examining the ratio of mapped reads instead of total reads, the LupiQuant ratio estimate was correct. Blast results of the unaligned reads with the NCBI nt database identified what may be a fungal contaminant with less than 50% homology to any published organism. Additional testing on subsequent samples will determine if this contamination is isolated or widespread. The host-to-parasite ratio approach has been used previously for two tick-transmitted intracellular protozoal parasites, Theileria annulata and Theileria parva, both affecting cattle, but no report exists for filarial nematodes of the genus Onchocerca [16, 32]. Furthermore, this study is the first to use WGS data to validate the qPCR results. LupiQuant represents a critical method that allows researchers to selectively sequence O. lupi, conduct population structure studies to understand pathogen spread, develop diagnostics for accurate epidemiological surveillance, and potentially identify novel therapeutics to improve animal outcomes.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

The data underlying the results presented in the study are available at GenBank under BioProject PRJNA802584.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Pacific Southwest Center of Excellence in Vector-Borne Diseases Grant no. [1004601] (CCR, JWS).The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. URL: https://pacvec.us/.

References

- 1.Roe CC, Yaglom H, Howard A, Urbanz J, Verocai GG, Andrews L, et al. Coyotes as Reservoirs for Onchocerca lupi, United States, 2015–2018. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2020. Dec [cited 2020 Nov 6];26(12). Available from: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/12/19-0136_article.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodonaja TE. A new species of Nematode, Onchocerca lupi n Sp., from Canis lupus cubanensis. Soobshchenyia Akad Nuak Gruz SSR. 1967;715–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantey PT, Weeks J, Edwards M, Rao S, Ostovar GA, Dehority W, et al. The Emergence of Zoonotic Onchocerca lupi Infection in the United States—A Case-Series. Clin Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016. Mar 15 [cited 2018 Mar 5];62(6):778–83. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26611778 doi: 10.1093/cid/civ983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maia C, Annoscia G, Latrofa MS, Pereira A, Giannelli A, Pedroso L, et al. Onchocerca lupi Nematode in Cat, Portugal. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015. Dec [cited 2018 Mar 5];21(12):2252–4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26584050 doi: 10.3201/eid2112.150061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Giannelli A, Latrofa MS, Papadopoulos E, Cardoso L, et al. Zoonotic Onchocerca lupi infection in dogs, Greece and Portugal, 2011–2012. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2013. Dec [cited 2018 Nov 26];19(12):2000–3. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24274145 doi: 10.3201/eid1912.130264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sréter T, Széll Z. Onchocercosis: A newly recognized disease in dogs. Vet Parasitol [Internet]. 2008. Jan 25 [cited 2018 Nov 26];151(1):1–13. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17951007 doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miró G, Montoya A, Checa R, Gálvez R, Mínguez JJ, Marino V, et al. First detection of Onchocerca lupi infection in dogs in southern Spain. Parasit Vectors [Internet]. 2016. Dec 18 [cited 2018 Nov 26];9(1):290. Available from: http://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-016-1587-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zarfoss MK, Dubielzig RR, Eberhard ML, Schmidt KS. Canine ocular onchocerciasis in the United States: two new cases and a review of the literature. Vet Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2005. Jan [cited 2019 Apr 15];8(1):51–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15644101 doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2005.00348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latrofa MS, Annoscia G, Colella V, Cavalera MA, Maia C, Martin C, et al. A real-time PCR tool for the surveillance of zoonotic Onchocerca lupi in dogs, cats and potential vectors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2019 Apr 15];12(4):e0006402. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29617361 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Giannelli A, Abramo F, Ignjatović Ćupina A, Petrić D, et al. Cutaneous Distribution and Circadian Rhythm of Onchocerca lupi Microfilariae in Dogs. Baneth G, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2013. Dec 12 [cited 2019 Apr 16];7(12):e2585. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24349594 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kläger SL, Whitworth JAG, Downham MD. Viability and fertility of adult Onchocerca volvulus after 6 years of treatment with ivermectin. Trop Med Int Heal [Internet]. 2007. Aug 1 [cited 2021 Mar 25];1(5):581–9. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1365-3156.1996.tb00083.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cantey P, Eberhard M, Weeks J, Swoboda S, Ostovar G. Letter to the Editor: Onchocerca lupi infection. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016;17(1):118–9. doi: 10.3171/2015.6.PEDS15344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grote A, Lustigman S, Ghedin E. Lessons from the genomes and transcriptomes of filarial nematodes. Mol Biochem Parasitol [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2019 Apr 11];215:23–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28126543 doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott AL, Ghedin E. The genome of Brugia malayi—all worms are not created equal. Parasitol Int [Internet]. 2009. Mar [cited 2019 Apr 10];58(1):6–11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18952001 doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaleta TG, Rödelsperger C, Abanda B, Eisenbarth A, Achukwi MD, Renz A, et al. Full mitochondrial and nuclear genome comparison confirms that Onchocerca sp. “Siisa” is Onchocerca ochengi. Parasitol Res [Internet]. 2018. Apr 1 [cited 2021 Mar 25];117(4):1069–77. Available from: 10.1007/s00436-018-5783-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gotia HT, Munro JB, Knowles DP, Daubenberger CA, Bishop RP, Silva JC. Absolute quantification of the host-To- Parasite DNA ratio in theileria parva- Infected lymphocyte cell lines. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016. Mar 1 [cited 2020 Nov 18];11(3). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4773007/?report = abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dackowski WR, Luderer HF, Manavalan P, Bukanov NO, Russo RJ, Roberts BL, et al. Canine PKD1 is a single-copy gene: Genomic organization and comparative analysis. Genomics [Internet]. 2002. [cited 2020 Nov 19];80(1):105–12. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12079289/ doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NCBI Resource Coordinators NR. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet]. 2016. Jan 4 [cited 2018 May 3];44(D1):D7–19. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26615191 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, et al. Primer3-new capabilities and interfaces. [cited 2022. Jan 1]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics [Internet]. 2009. Jul 15 [cited 2018 Jan 4];25(14):1754–60. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19451168 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahl JW, Lemmer D, Travis J, Schupp JM, Gillece JD, Aziz M, et al. NASP: an accurate, rapid method for the identification of SNPs in WGS datasets that supports flexible input and output formats. Microb genomics [Internet]. 2016. Aug 25 [cited 2018 Dec 20];2(8):e000074. Available from: http://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/mgen/10.1099/mgen.0.000074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marçais G, Delcher AL, Phillippy AM, Coston R, Salzberg SL, Zimin A. MUMmer4: A fast and versatile genome alignment system. Darling AE, editor. PLOS Comput Biol [Internet]. 2018. Jan 26 [cited 2019 Mar 31];14(1):e1005944. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michalski ML, Griffiths KG, Williams SA, Kaplan RM, Moorhead AR. The NIH-NIAID Filariasis Research Reagent Resource Center. Knight M, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2011. Nov 29 [cited 2021 Mar 25];5(11):e1261. Available from: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics [Internet]. 2009. Dec 15 [cited 2018 Dec 20];10:421. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20003500 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whelan JA, Russell NB, Whelan MA. A method for the absolute quantification of cDNA using real-time PCR. J Immunol Methods [Internet]. 2003. [cited 2022 Jan 10];278(1–2):261–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12957413/ doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00223-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone NE, Sidak-Loftis LC, Sahl JW, Vazquez AJ, Wiggins KB, Gillece JD, et al. More than 50% of Clostridium difficile Isolates from Pet Dogs in Flagstaff, USA, Carry Toxigenic Genotypes. Lai H-C, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016. Oct 10 [cited 2018 Oct 23];11(10):e0164504. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics [Internet]. 2014. Aug 1 [cited 2018 Nov 26];30(15):2114–20. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24695404 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J Comput Biol [Internet]. 2012. May [cited 2018 Dec 20];19(5):455–77. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22506599 doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, Sakthikumar S, et al. Pilon: An Integrated Tool for Comprehensive Microbial Variant Detection and Genome Assembly Improvement. Wang J, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2014. Nov 19 [cited 2018 Oct 23];9(11):e112963. Available from: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods [Internet]. 2012. Mar 4 [cited 2018 Nov 26];9(4):357–9. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/nmeth.1923 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Picard Toolkit. Broad Institute [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/

- 32.Dandasena D, Bhandari V, Sreenivasamurthy GS, Murthy S, Roy S, Bhanot V, et al. A Real-Time PCR based assay for determining parasite to host ratio and parasitaemia in the clinical samples of Bovine Theileriosis. Available from: www.nature.com/scientificreports/ doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33721-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying the results presented in the study are available at GenBank under BioProject PRJNA802584.