Abstract

Stress-adaptive mechanisms enable tumour cells to overcome metabolic constraints under nutrient and oxygen shortage. Aspartate is an endogenous metabolic limitation under hypoxic conditions, but the nature of the adaptive mechanisms that contribute to aspartate availability and hypoxic tumour growth are poorly understood. Here we identify GOT2-catalysed mitochondrial aspartate synthesis as an essential metabolic dependency for the proliferation of pancreatic tumour cells under hypoxic culture conditions. In contrast, GOT2-catalysed aspartate synthesis is dispensable for pancreatic tumour formation in vivo. The dependence of pancreatic tumour cells on aspartate synthesis is bypassed in part by a hypoxia-induced potentiation of extracellular protein scavenging via macropinocytosis. This effect is mutant KRAS dependent, and is mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF1A) and its canonical target carbonic anhydrase-9 (CA9). Our findings reveal high plasticity of aspartate metabolism and define an adaptive regulatory role for macropinocytosis by which mutant KRAS tumours can overcome nutrient deprivation under hypoxic conditions.

Nutrient scarcity and low-oxygen levels are hallmarks of the tumour microenvironment1. To survive under these stress conditions, cancer cells leverage oncogenic alterations that engage stress-adaptive responses and facilitate the production of energy and biosynthetic precursors necessary for cell division2. Thus, identification of the molecular underpinnings of stress-adaptive pathways can provide insight into potential cancer cell-specific vulnerabilities. Activating KRAS mutations are among the most common oncogenic events in human cancers3. Through the engagement of multiple effector mechanisms, mutant KRAS directs the reprogramming of cellular metabolism to favour macromolecular synthesis and enhance nutrient acquisition capabilities. Indeed, KRAS activation is associated with an increase in glucose and glutamine use, which supports the synthesis of critical precursors for cell proliferation such as nucleotides and lipids4,5. Furthermore, mutant KRAS cells display enhanced autophagic flux6,7 and macropinocytosis8, facilitating intracellular protein catabolism and extracellular protein degradation. These adaptive mechanisms are particularly relevant for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), which is severely nutrient limited owing to a dense desmoplastic stroma and collapsed blood vessels9. However, their relative contribution to the fitness of pancreatic cancer cells under metabolic stress conditions is yet to be determined.

As oxygen is an essential substrate for many biosynthetic reactions10, hypoxia leads to multiple metabolic limitations that pancreatic cancer cells need to overcome. We have previously shown that, in tumour cell lines, hypoxia limits access to electron acceptors essential for the synthesis of aspartate and aspartate-derived nucleotides11. Indeed, aspartate production is limiting for a subset of hypoxic tumours and increasing its availability is sufficient to promote tumour growth11,12. In the present study, we identify cellular mechanisms used by pancreatic tumour cells to overcome aspartate limitation under hypoxic conditions.

Results

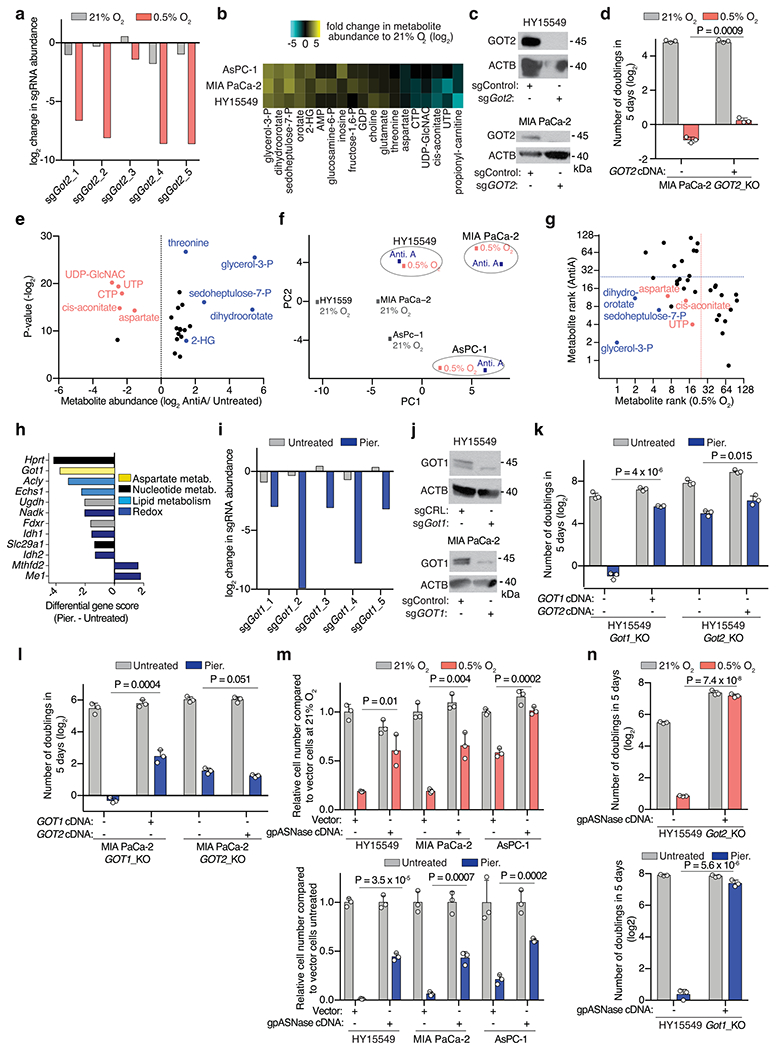

Metabolic dependencies of hypoxic pancreatic cancer cells.

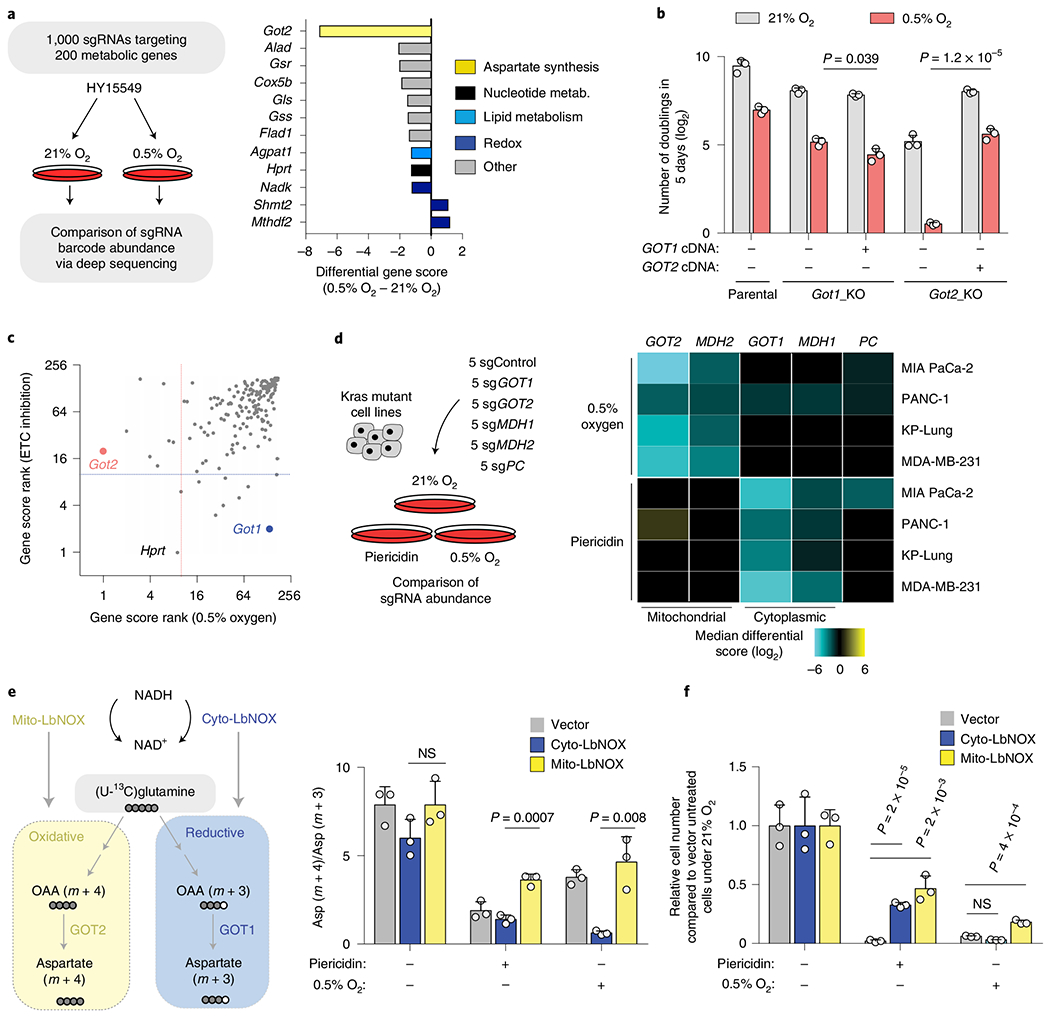

PDAC often grows in a hypoxic microenvironment due to poorly functioning vasculature13,14. To identify metabolic genes that PDAC cells depend on under hypoxia, we performed a focused, pooled CRISPR screen of 200 rate-limiting and cancer-relevant metabolic genes in mouse PDAC cells grown under normoxic (21%) or hypoxic conditions (0.5%) (Fig. 1a). Our screen identified the mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase (GOT2) as the top scoring gene necessary for PDAC cell growth under hypoxia (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a). These results were concordant with our previous findings demonstrating that human and mouse PDAC cells displayed substantial decreases in aspartate and nucleotide (UTP, CTP) levels when grown in low-oxygen conditions11 (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Confirming the screen results, GOT2 null cells proliferated substantially slower than single-guide (sg)RNA-resistant GOT2 complementary DNA-expressing cells in the context of low oxygen (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1c,d). As oxygen is the final electron acceptor for the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) and severe hypoxia may restrict ETC activity15, we conducted an analogous screen using ETC inhibitors. This perturbation yielded a similar metabolic signature, but a distinct set of genetic dependencies (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1e–h). Specifically, PDAC cells depended on the cytoplasmic aspartate transaminase GOT1 under ETC inhibition16 (Extended Data Fig. 1i) and GOT1 loss strongly sensitized cells to this condition, but not hypoxia (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1j–l). Increasing aspartate availability by expressing an intracellular guinea pig asparaginase (gpASNase)12 was sufficient to rescue proliferation defects under both conditions in parental (Extended Data Fig. 1m) and GOT1 or GOT2-knockout cells (Extended Data Fig. 1n). Finally, a small-scale sgRNA competition assay targeting each of the four genes in the aspartate-malate shuttle (GOT1, MDH1, GOT2, MDH2) or pyruvate carboxylase (PC)17 revealed that distinct compartmentalized routes operate for aspartate synthesis under hypoxia versus ETC inhibition (Fig. 1d). Together, these data indicate that PDAC cells use distinct metabolic pathways for aspartate synthesis (mitochondrial versus cytoplasmic) under different stresses and depend on mitochondrial aspartate synthesis under hypoxic culture conditions.

Fig. 1 |. The metabolic route for aspartate synthesis in hypoxic pancreatic cancer cells.

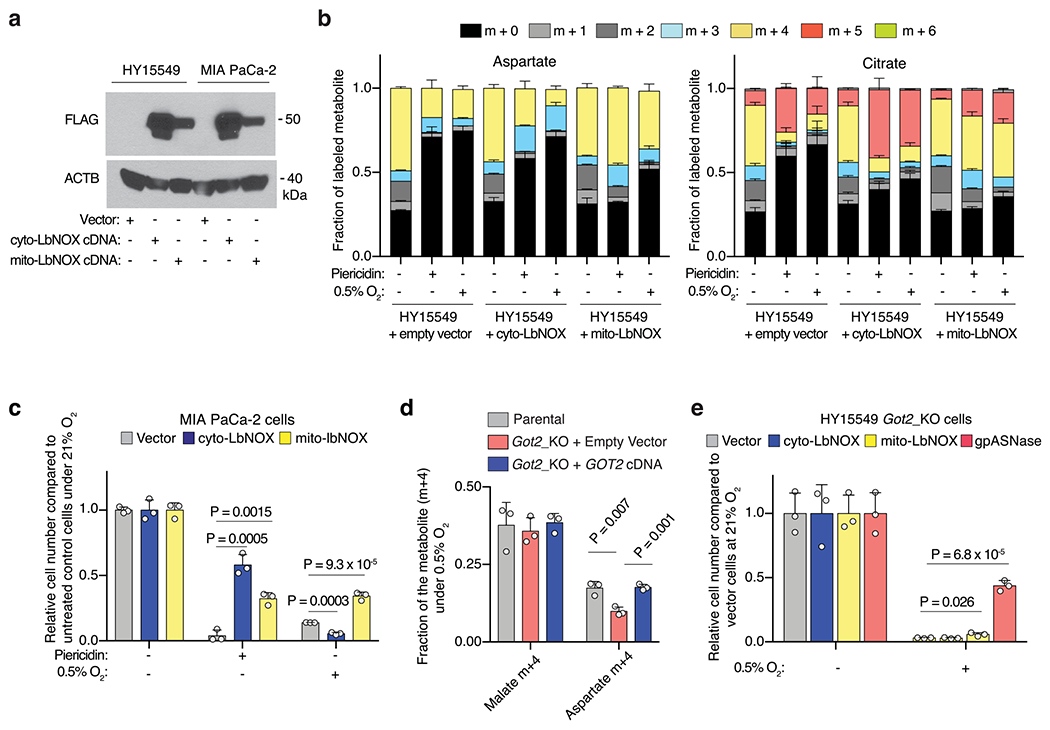

a, Scheme of the focused CRISPR–Cas9 based genetic screen in a Ras mutant mouse PDAC line (HY15549) grown under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic conditions (0.5% O2) for 14 population doublings (left). Top scoring genes and their differential gene scores in the focused CRISPR screen (right). b, Number of doublings (log2) of indicated parental, Got1 and Got2-knockout HY15549 cell lines expressing sgRNA-resistant GOT1 or GOT2 cDNA and grown for 5 days under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic conditions (0.5% O2). c, Plot of gene score ranks of hypoxia and ETC inhibitor CRISPR screens in HY15549 cells. d, Scheme of the in vitro sgRNA competition assay performed in KRAS-mutant cancer cell lines transduced with a pool of five control sgRNAs (sgControl) and sgRNAs targeting five enzymes involved in aspartate metabolism (GOT1, GOT2, MDH1, MDH2 and PC) (left). Heat map showing median differential gene scores in the indicated cell lines on low oxygen (0.5% O2) or treatment with piericidin, an ETC inhibitor (right). e, Scheme depicting the oxidative (yellow) and reductive (blue) routes from which aspartate can be synthesized from glutamine, and the activation of each pathway by mito- and cyto-LbNOX enzymes. Filled circles represent 13C atoms derived from [U-13C]-l-glutamine (left). Oxidative (m + 4) to reductive (m + 3) aspartate ratio in HY15549 cell lines grown under 21% O2, 0.5% O2 or in the presence of piericidin (50 nM) (right). f, Relative fold change in cell number in HY15549 cell lines transduced with a vector control, cyto-LbNOX or mito-LbNOX grown for 5 days under 0.5% O2 or in the presence of piericidin (50 nM). b,e,f, Bars represent mean±s.d.; b,d,e,f, n = 3 biologically independent samples. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired t-test. NS, not significant.

Mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is limiting for hypoxic PDAC cell growth.

Impairment of respiration limits NAD+ for tricarboxylic acid cycle progression, thereby hindering production of oxaloacetate, the precursor for aspartate synthesis16,18. As PDAC cells depend on the mitochondrial, but not cytoplasmic, aspartate transaminase under hypoxia, we proposed that mitochondrial NAD+ may be more limiting for PDAC cell proliferation under hypoxic conditions. To test this idea, we used mitochondria- or cytoplasmic-localized versions of the water-forming NADH oxidase LbNOX, a bacterial enzyme that recycles NADH into NAD+ (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 2a)19. Consistent with previous reports19, expression of mito-LbNOX regenerated mitochondrial NAD+ and allowed cells to maintain tricarboxylic acid cycle activity, supporting oxidative glutamine metabolism in spite of low oxygen or ETC inhibition (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 2b). Conversely, cytoplasmic-LbNOX (cyto-LbNOX) expression regenerated cytoplasmic NAD+ and promoted reductive metabolism of glutamine (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 2b). Using this system, we found that only mito-LbNOX expression promoted cell proliferation under hypoxia (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 2c). Notably, the antiproliferative effects of pharmacologic ETC inhibition were rescued by both cyto- or mito-LbNOX (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 2c). Isotope labelling studies under hypoxia revealed that GOT2-knockout cells synthesized lower levels of aspartate through the oxidative metabolism of glutamine (Extended Data Fig. 2d). Accordingly, in the absence of GOT2, increasing aspartate availability by gpASNase expression rescued hypoxia-induced proliferation arrest (Extended Data Fig. 2e). These results indicate that the selective dependence of PDAC cells on GOT2 for proliferation under hypoxia might be imposed by the limiting levels of mitochondrial NAD+.

Aspartate transaminases are redundant for PDAC tumour formation.

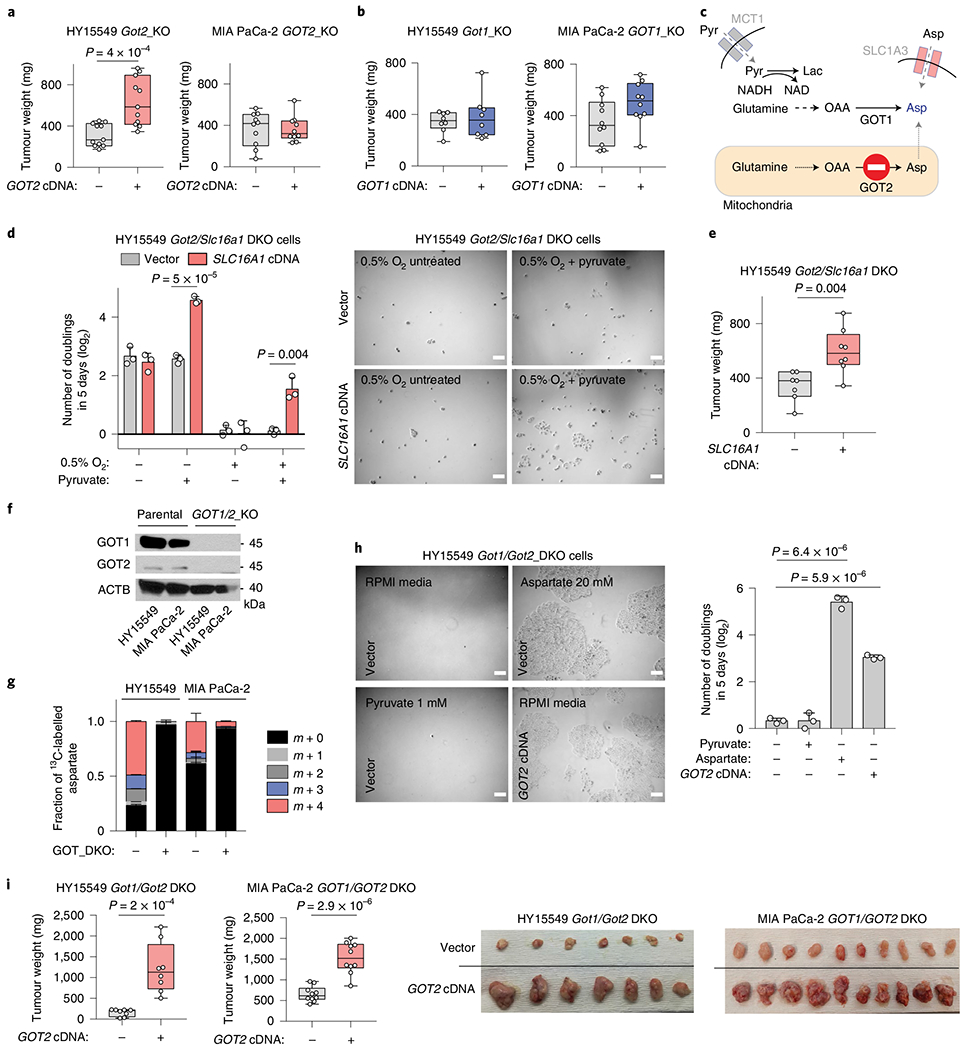

While cancer cells in culture rely on aspartate synthesis under hypoxia, the relative contributions of aspartate transaminases (GOT1 and GOT2) to tumour growth in vivo are not clear. We first tested the effects of GOT2 deletion on tumour growth in murine HY15549 (ref. 20) and human MIA PaCa-2 cells. Loss of GOT2 did not decrease the size of MIA PaCa-2 tumours and only modestly affected those derived from the HY15549 cancer cell line (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). Similarly, GOT1 loss did not result in any significant change in tumour growth (Fig. 2b). In vivo sgRNA competition assays confirmed that these results could be generalized to other PDAC cell lines implanted either subcutaneously or orthotopically and to patient-derived xenografts (PDX) (Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). Consistent with the requirement of exogenous NAD+ sources for GOT1-mediated aspartate synthesis (Fig. 2c), supplementation of culture media with pyruvate, an exogenous electron acceptor that can regenerate NAD+, rescued the antiproliferative effects of hypoxia both in GOT2-KO (Extended Data Fig. 3e) and GOT1-KO cells in a manner dependent on GOT1 activity (Extended Data Fig. 3f). Pyruvate is one of the metabolites secreted by human pancreatic stellate cells (hPSC)21,22. Indeed, addition of hPSC-conditioned media to HY15549 cells promoted hypoxic cell proliferation comparably to pyruvate supplementation (Extended Data Fig. 3g). We next sought to determine whether pyruvate uptake might enable the growth of GOT2-deficient PDAC tumours in vivo. Cancer cells take up pyruvate through monocarboxylate transporters, in particular SLC16A1 (MCT1)23 (Fig. 2c). Pharmacologic inhibition of SLC16A1 (Extended Data Fig. 3g) or its genetic loss in Got2-knockout PDAC cells (Extended Data Fig. 3h) halted hypoxic proliferation under physiological pyruvate levels24 (Fig. 2d). Consistent with the significant contribution of extracellular pyruvate to PDAC tumour growth, Got2/Slc16a1 double-knockout cells formed significantly smaller tumours compared to those expressing SLC16A1 cDNA (Fig. 2e). These results indicate that environmental pyruvate may provide sufficient NAD+ to support aspartate synthesis and tumour growth.

Fig. 2 |. The plasticity of aspartate metabolism in PDAC tumours.

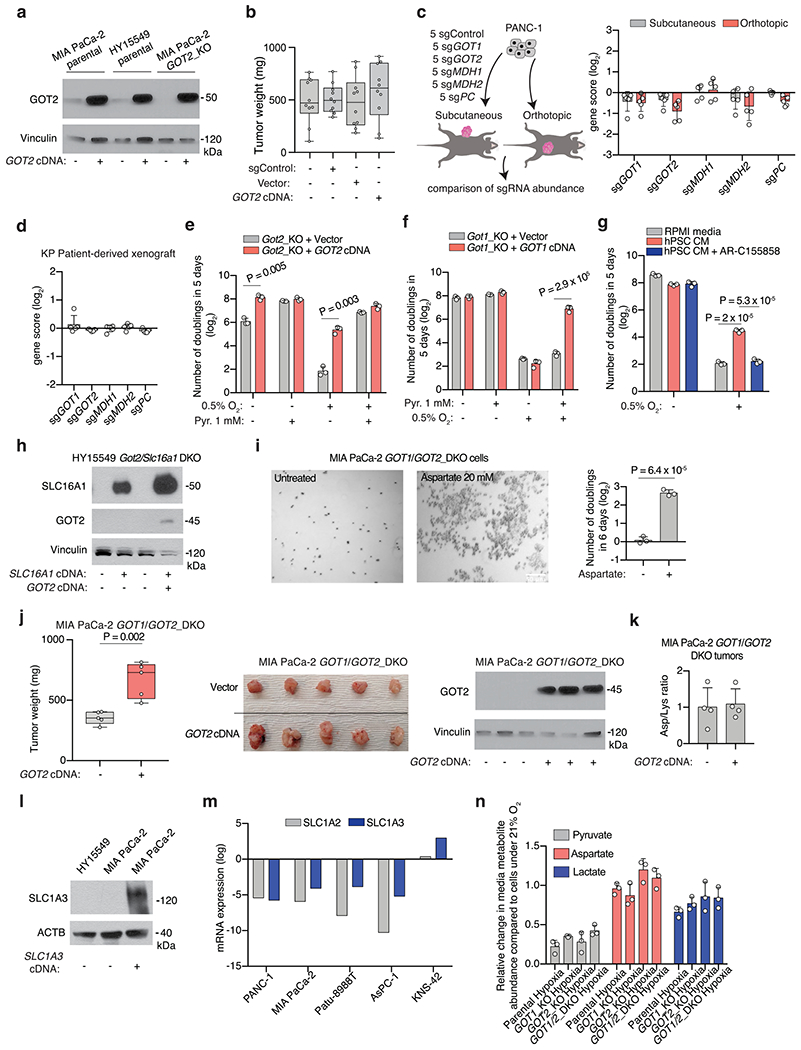

a,b, Weights of subcutaneous tumour xenografts derived from GOT2 (a) and GOT1-knockout (KO) (b) cell lines transduced with a control vector or an sgRNA-resistant cDNA. c, Scheme depicting metabolic pathways that compensate for the loss of aspartate synthesis in GOT2-knockout cells. d, Number of doublings (log2) of Got2/Slc16a1 double-knockout (DKO) HY15549 cells transduced with a control vector or an sgRNA-resistant SLC16A1 cDNA after 5 days of growth in the absence or presence of pyruvate (100 μM) (left). Representative bright-field micrographs of indicated cells under 0.5% O2 in the presence or absence of pyruvate (100 μM). Scale bar, 50 μm (right). e, Weights of subcutaneous tumour xenografts derived from the Got2/Slc16a1 double-knockout HY15549 cells transduced with a control vector or an sgRNA-resistant SLC6A1 cDNA. f, Immunoblot analysis of GOT1 and GOT2 in indicated cell lines. ACTB was used as loading control. g, Fraction of 13C-labelled aspartate in indicated cell lines cultured for 8 h in the presence of 0.5 mM [U-13C]-l-glutamine. h, Representative bright-field micrographs (left) and number of doublings (log2) (right) of Got1/Got2-double-knockout HY15549 cells transduced with a control vector or an sgRNA-resistant GOT2 cDNA grown for 5 days in indicated culture conditions. Scale bar, 50 μm (left). i, Weights of subcutaneous tumour xenografts derived from the indicated Got1/Got2 double-knockout cell lines transduced with a control vector or an sgRNA-resistant GOT2 cDNA (left). Representative images of indicated tumours (right). a,b,e,i, boxes represent the median, and the first and third quartiles, and the whiskers represent the minima and maxima of all data points. d,g,h, Bars represent mean± s.d. a,b,e,i, n = 11, 11, 10, 10, 8, 8, 10, 10, 7, 8, 8 and 8 biologically independent samples in each graph shown, respectively. d,g,h, n = 3 biologically independent samples. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired t-test.

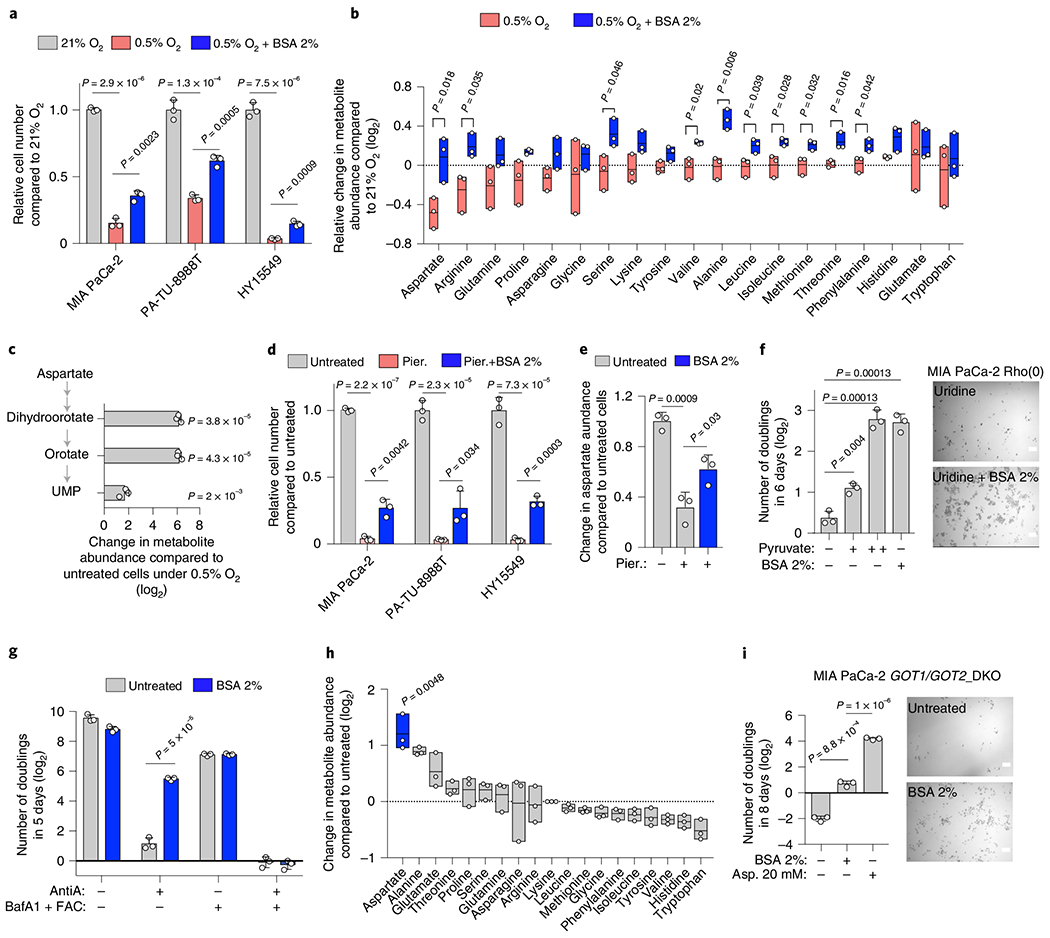

Fig. 3 |. Macropinocytosis provides sufficient aspartate to enable PDAC cell growth under hypoxic culture conditions.

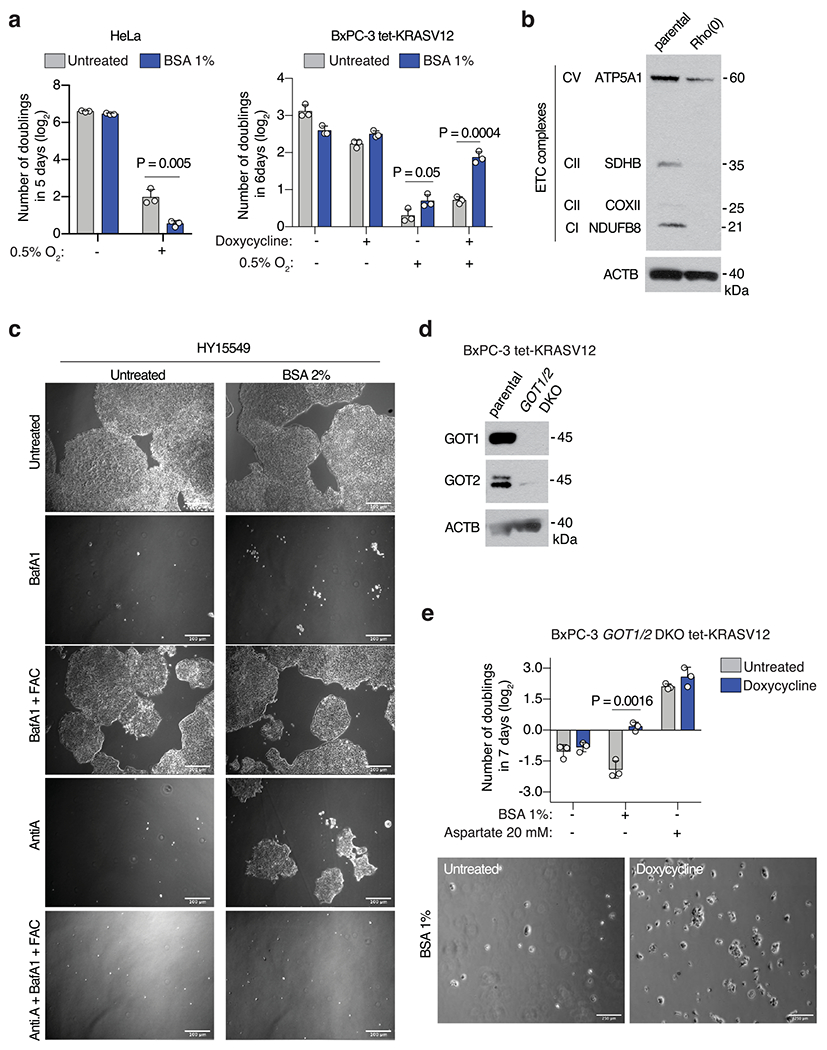

a, Relative cell number of indicated cell lines grown under indicated conditions. b, Relative change (log2) in amino acid abundance in MIA PaCa-2 cells grown under indicated conditions. c, Relative change (log2) in the indicated metabolites in MIA PaCa-2 cells grown under 0.5% O2 with 2% BSA to those without. d, Relative cell number of indicated cell lines treated with piericidin (Pier.; MIA PaCa-2, PA-TU-8998T 100 nM; HY15549 30 nM) for 5 days in the presence or absence of 2% BSA. e, Relative aspartate abundance of MIA PaCa-2 cells treated with piericidin (150 nM) with or without 2% BSA compared to controls. Metabolite abundance is normalized by total protein levels. f, Number of doublings (log2) of MIA PaCa-2 Rho(0) cells grown for 6 days in media supplemented with uridine (50 μg ml−1) in the presence or absence of pyruvate (+, 100 μM; ++, 1 mM) or 2% BSA (left). Representative bright-field micrographs of MIA PaCa-2 Rho(0) cells for indicated conditions. Scale bar, 50 μm (right). g, Number of doublings (log2) of HY15549 cells grown for 5 days in the absence and presence of 2% BSA, antimycin A (AntiA., 100 nM) or Bafilomycin A1 (BafA1, 10 nM + ferric ammonium citrate (FAC) 0.1 μg ml−1). h, Relative change (log2) in amino acid abundance of GOT1/GOT2 double-knockout MIA PaCa-2 cells grown for 48 h with or without 2% BSA. Aspartate is highlighted in blue. i, Number of doublings (log2) of indicated cells grown for 8 days in regular RPMI media and media supplemented with 2% BSA or aspartate (20 mM) (left). Representative bright-field micrographs of GOT1/GOT2 double-knockout MIA PaCa-2 cells in the presence or absence of BSA 2%. Scale bar, 50 μm (right). a,c–g,i, Bars represent mean±s.d.; b,h, boxes represent the median, and the first and third quartiles. a–i, n = 3 biologically independent samples. Statistical significance determined by a two-tailed unpaired t-test.

To assess directly whether de novo aspartate synthesis is redundant for tumour formation, we generated HY15549 and MIA PaCa-2 PDAC cell lines lacking both aspartate aminotransferases (GOT1/2 DKO), and thus auxotrophic for aspartate (Fig. 2f). Glutamine labelling confirmed that GOT1/2 DKO cells did not synthesize aspartate de novo (Fig. 2g). Consequently, these cells could be grown only in media supplemented with supraphysiological levels of aspartate (20 mM), highlighting their inability to grow in vitro (Fig. 2h and Extended Data Fig. 3i). While aspartate synthesis by GOTs was necessary for survival in culture, GOT1/2 DKO PDAC cells still formed tumours, either subcutaneously or orthotopically, albeit smaller (Fig. 2i and Extended Data Fig. 3j), indicating the presence of alternative sources for aspartate in vivo. Of note, aspartate levels in MIA PaCa-2 GOT1/2 DKO tumours were comparable to those of cells expressing GOT2 cDNA (Extended Data Fig. 3k). These results indicate that tumour aspartate availability is maintained by both de novo synthesis and alternative extracellular sources in vivo.

Macropinocytosis enables hypoxic PDAC cell growth.

To identify potential extracellular sources of aspartate, we first considered the possibility that the loss of aspartate biosynthesis could be compensated by the uptake of extracellular aspartate via plasma membrane aspartate/glutamate SLC1A family transporters11 (Fig. 2c). However, none of the main SLC1A aspartate transporters were expressed in PDAC cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 3l,m)25. Furthermore, secretion and uptake of aspartate appeared unaffected by hypoxic culture conditions (Extended Data Fig. 3n). An alternative mechanism that may enable cells to obtain aspartate from extracellular sources is the scavenging of albumin via macropinocytosis, a mutant KRAS dependent process8. Indeed, the macropinocytic uptake of albumin, the most abundant protein in interstitial fluids, and its subsequent lysosomal degradation has been shown to generate free amino acids8,26–28. We therefore tested the effects of bovine serum albumin (BSA) supplementation on aspartate levels and growth of hypoxic PDAC cells. The growth defect of KRAS mutant PDAC cell lines under hypoxic conditions was partly rescued by BSA supplementation (Fig. 3a). Metabolomic analysis of MIA PaCa-2 cells grown under hypoxia in the presence or absence of BSA identified aspartate as the only amino acid whose levels significantly decreased in response to hypoxia, and the addition of BSA was sufficient to restore its levels to those observed in normoxic cells (Fig. 3b). In addition, BSA dramatically increased the levels of pyrimidine synthesis intermediates (dihydroorotate, orotate and uridine-monophosphate, UMP) (Fig. 3c), for which aspartate is a precursor11. These results indicate that macropinocytosis could provide sufficient aspartate to promote proliferation of KRAS-mutant cancer cells under hypoxic conditions (Extended Data Fig. 4a).

We next sought to determine whether albumin-mediated rescue of cell growth is restricted to hypoxia or can be generalized to other conditions where aspartate levels are limiting. We therefore tested the ability of albumin to rescue the antiproliferative effects of ETC inhibition. Similar to hypoxia, BSA supplementation partly overcame the antiproliferative effects of a complex I inhibitor (Fig. 3d) and the drop in aspartate levels (Fig. 3e) in PDAC cell lines. Likewise, the addition of BSA to MIA PaCa-2 cells that are ETC-defective by virtue of lacking mitochondrial DNA29 (MIA PaCa-2 Rho(0)) (Extended Data Fig. 4b) enabled their proliferation to the same extent observed on pyruvate supplementation (Fig. 3f). Consistent with BSA exerting its effects through macropinocytic uptake and lysosomal degradation, treatment of HY15549 with Bafilomycin A1 (BafA1), an inhibitor of lysosomal acidification30, prevented the proliferation rescue by BSA under ETC inhibition by a complex III inhibitor (Fig. 3g and Extended Data Fig. 4c). In line with previous findings, these experiments required iron supplementation to maintain viability of cells without lysosomal acidity31. Finally, consistent with albumin as a sufficient source for aspartate, BSA supplementation increased aspartate levels (Fig. 3h) and enabled proliferation (Fig. 3i) of MIA PaCa-2 GOT1/2 DKOs cells that were auxotrophic for aspartate. This effect was dependent on the presence of mutant RAS, as addition of BSA to GOT1/2 DKO cells generated from BXPC-3 cell line with wild type (WT) RAS alleles (Extended Data Fig. 4d) allowed cell proliferation only on expression of oncogenic KRAS (Extended Data Fig. 4e). Collectively, these experiments indicate that protein scavenging via macropinocytosis contributes sufficient aspartate for growth when aspartate is limiting.

Hypoxia upregulates macropinocytosis in mutant KRAS cells.

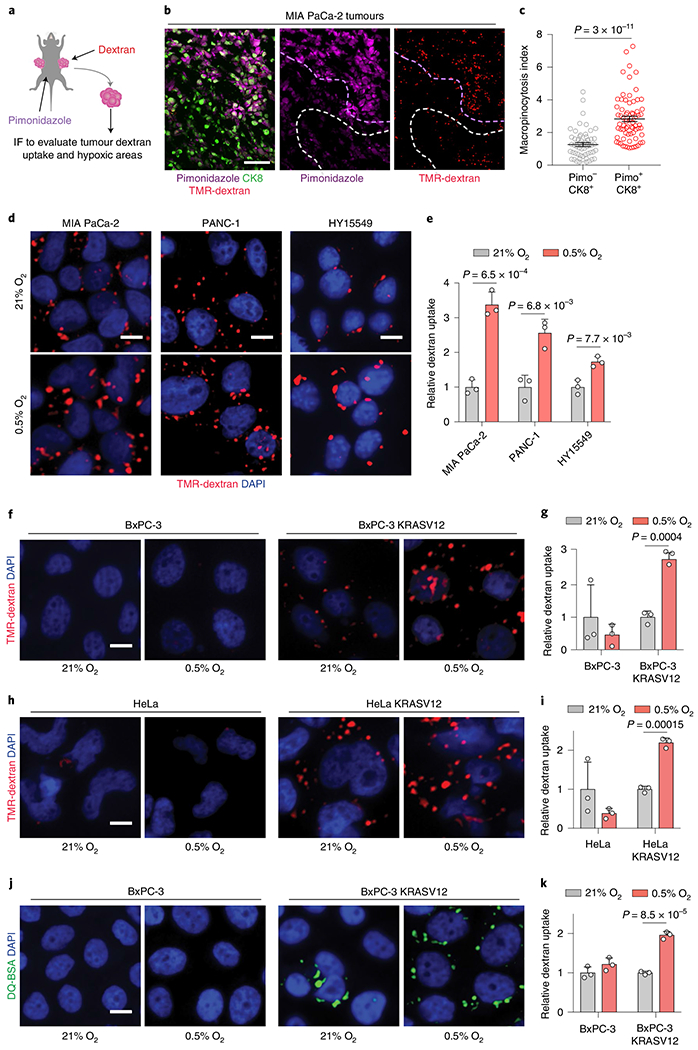

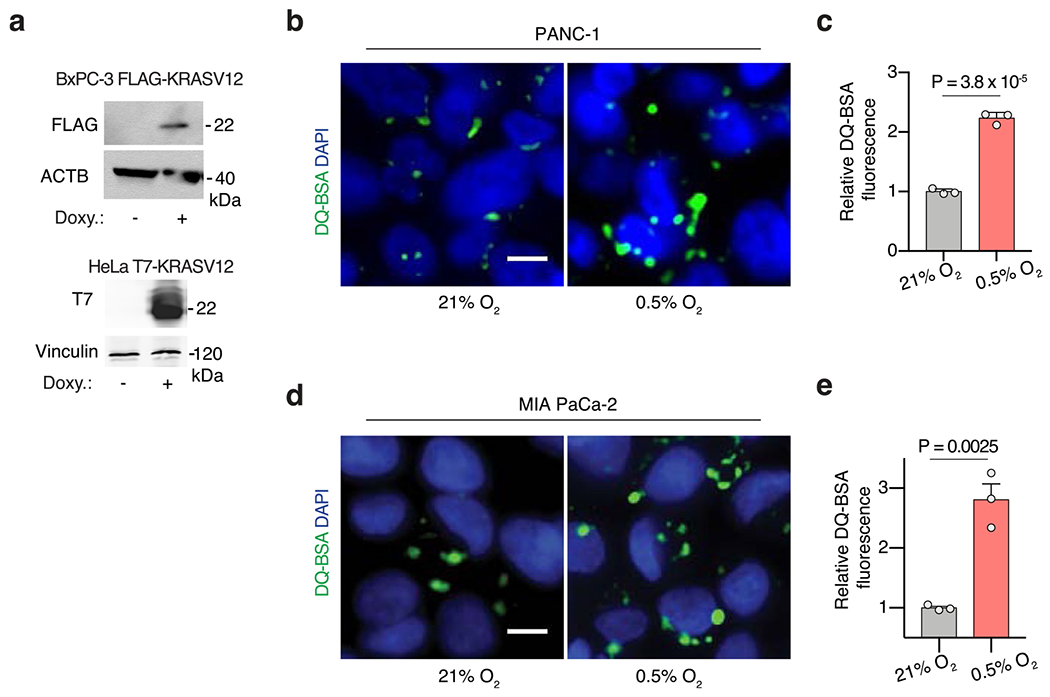

Given our findings linking macropinocytosis to an increase in aspartate levels under hypoxic conditions, we set out to investigate the relationship between hypoxia and macropinocytosis. To this end, tumour xenografts derived from MIA PaCa-2 cells were costained with tetramethylrhodamine-labelled high molecular weight dextran (TMR-dextran), a marker of macropinocytosis, and pimonidazole, a non-toxic 2-nitroimidazole hypoxia marker32 (Fig. 4a). A marked increase in TMR-dextran uptake by tumour cells, identified by positive staining for cytokeratin 8 (CK8), was observed in areas of high pimonidazole staining, suggesting that tumour hypoxia correlated with elevated macropinocytosis (Fig. 4b,c). Hypoxia also caused a pronounced increase in the uptake of TMR-dextran in KRAS-mutant PDAC cell lines in vitro (Fig. 4d,e). The hypoxia-dependent increase in macropinocytic uptake was restricted to KRAS-mutant cells, and the expression of oncogenic KRAS in WT RAS cells was sufficient to confer this dependency, implicating a direct role for mutant KRAS in linking hypoxia to the modulation of macropinocytosis levels (Fig. 4f–i and Extended Data Fig. 5a). Moreover, in KRAS mutant cells incubated with DQ-BSA, the hypoxia-induced macropinocytic uptake was accompanied by an increase in DQ-BSA fluorescence, indicating a corresponding increase the proteolytic degradation of BSA (Fig. 4j,k and Extended Data Fig. 5b–e). Thus, the upregulation of macropinocytosis might serve to improve tumour cell fitness in response to nutrient deprivation imposed by low-oxygen conditions.

Fig. 4 |. Hypoxia upregulates macropinocytosis in mutant KRAS cells in vivo and in vitro.

a, Schematic of in vivo assay for administering intratumoral TMR-dextran and intraperitoneal pimonidazole injection to identify macropinosomes and hypoxic regions of tumours, respectively. IF, immunofluorescence. b, Hypoxic tumour areas display more macropinocytosis than neighbouring non-hypoxic areas. Representative images from sections of MIA PaCa-2 xenograft tumour tissue showing macropinosomes labelled with TMR-dextran (red), tumour cells immunostained with anti-CK8 (green) and pimonidazole detected with antipimonidazole (purple). Dashed lines indicate high (purple) and low (white) areas of pimonidazole staining. Scale bar, 50 μm. c, Quantification of macropinocytic uptake in b showing tumour macropinocytosis index in hypoxic tumour areas (CK8+/Pimo+, red) relative to non-hypoxic tumour areas (CK8+/Pimo−, grey). d,e, Representative images (d) and quantification (e) of TMR-dextran (red) uptake in MIA PaCa-2, PANC-1 and HY15549 cells under normoxia (21% O2) and hypoxia (0.5% O2). Nuclei are labelled with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. In e, data are presented relative to normoxic controls for respective lines. f–i, Hypoxia-induced macropinocytosis depends on oncogenic RAS. Representative images (f,h) and quantification (g,i) of TMR-dextran (red) uptake in BxPC-3 cells (f,g) and HeLa cells (h,i) without and with expression of doxycycline-inducible KRASG12V grown in normoxia (21% O2) or hypoxia (0.5% O2). Nuclei are labelled with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. In g,i, data are presented relative to normoxic controls for respective lines. j,k, Representative images (j) and quantification (k) of DQ-BSA fluorescence (green) in BxPC-3 cells without and with expression of doxycycline-inducible KRASG12V grown in normoxia (21% O2) or hypoxia (0.5% O2). Scale bar, 10 μm. In k, data are presented relative to normoxia of the respective cell line. c,e,g,i,k, Bars represent mean ± s.e.m. At least 300 (c) or 500 (e,g,i,k) cells were quantified in each biological replicate (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired t-test.

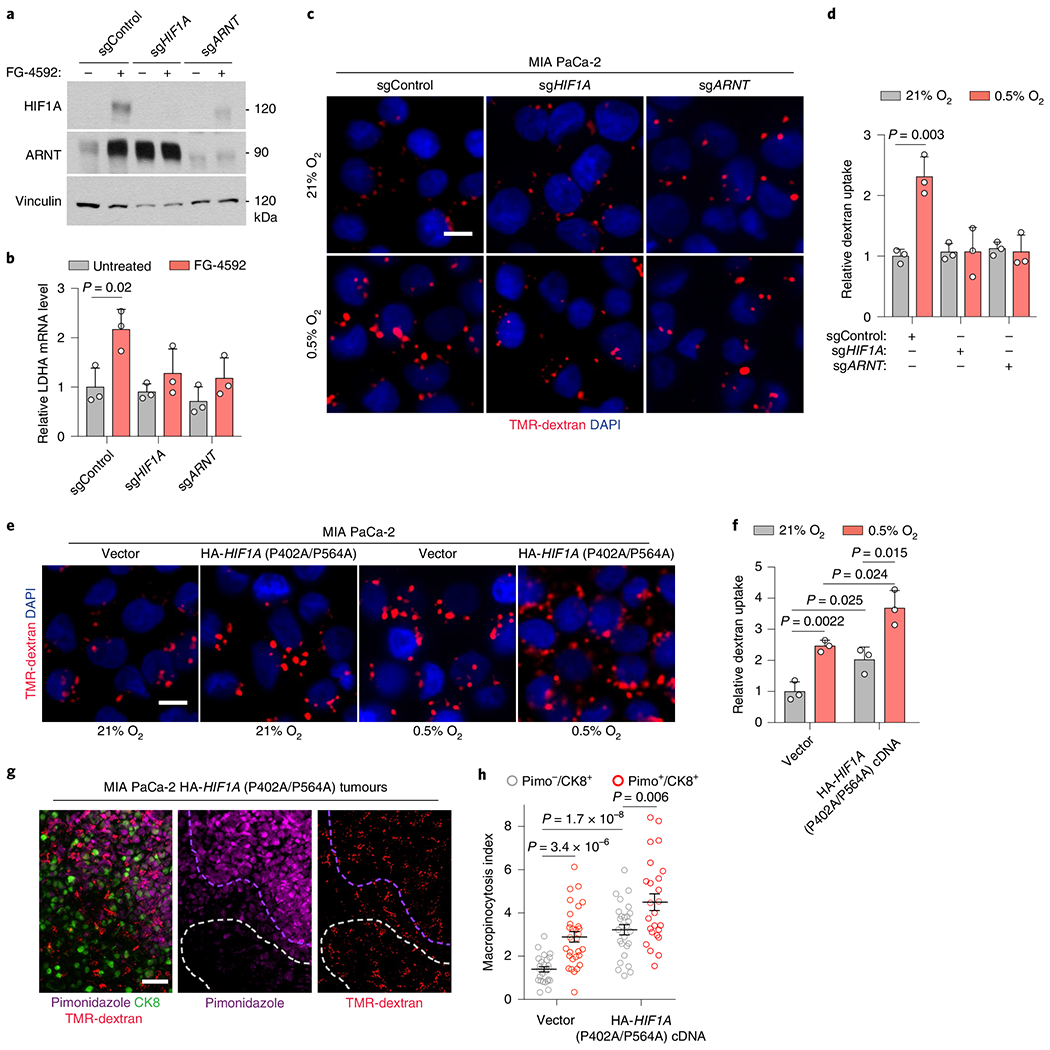

HIF1A regulates macropinocytosis under hypoxia.

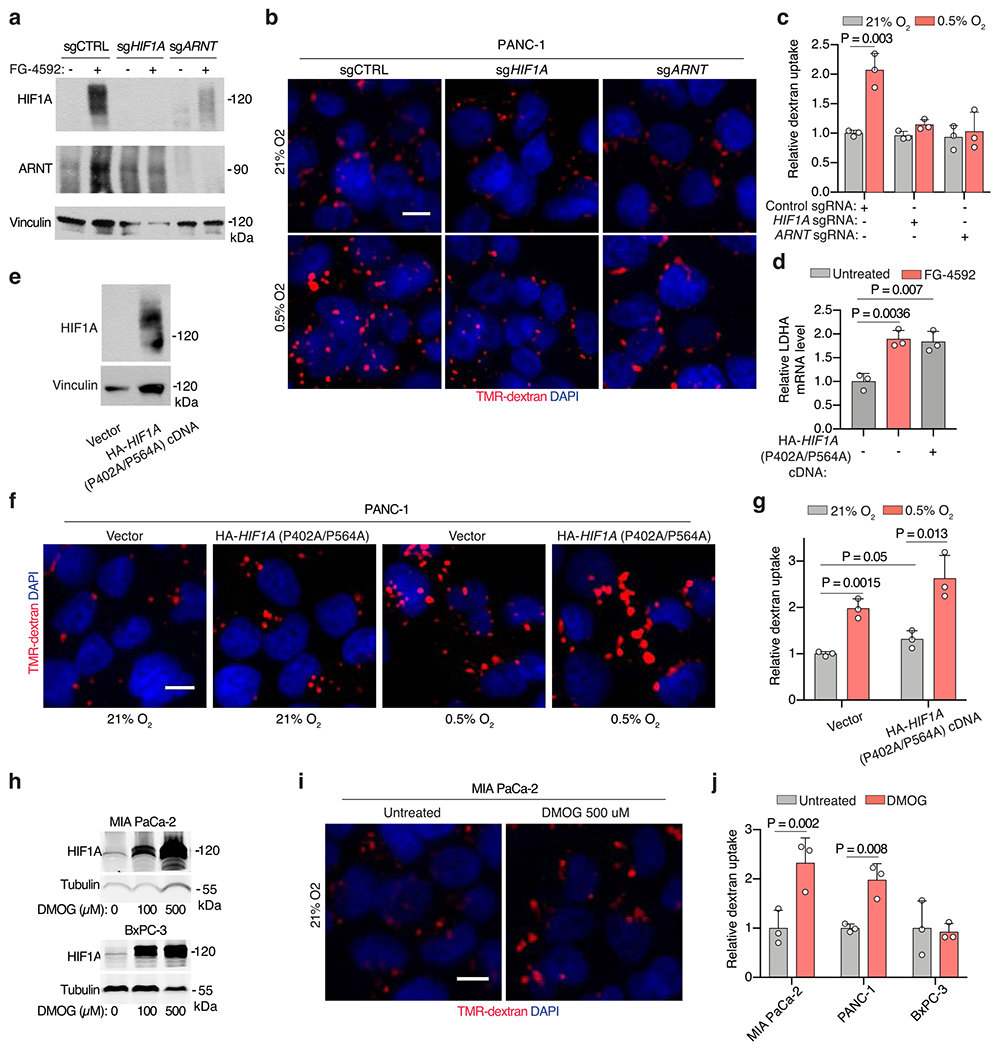

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF1) is a heterodimeric, basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor that is composed of HIF1A, the alpha subunit, and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), the beta subunit33. HIF1A is considered the master transcriptional regulator of cellular responses to hypoxia34, raising the possibility that it might play a role in the potentiation of macropinocytosis under hypoxic conditions. Indeed, KRAS mutant cells deficient for HIF1A or ARNT (Fig. 5a,b and Extended Data Fig. 6a) failed to display an increase in macropinocytosis in response to hypoxia (Fig. 5c,d and Extended Data Fig. 6b,c). Conversely, mutant KRAS cells transduced with a constitutively active HIF1A variant (HIF1A P402A/P564A)35 (Extended Data Fig. 6d,e) displayed an enhancement of macropinocytosis under standard atmospheric conditions, and a robust potentiation of the increase in macropinocytosis triggered by low oxygen (Fig. 5e,f and Extended Data Fig. 6f,g). Consistent with these results, stabilization of alpha subunits of HIFs by chemical inhibition of prolyl-hydroxylases (PHDs)36 also induced TMR-dextran uptake (Extended Data Fig. 6h–j) only in PDAC cells with oncogenic RAS mutations (Extended Data Fig. 6j). In agreement with the in vitro data, constitutive activation of HIF1A resulted in the enhancement of macropinocytosis in both hypoxic and non-hypoxic tumour regions (Fig. 5g,h). Collectively, these results indicate that the HIF1A/ARNT axis is a necessary and sufficient mediator of hypoxia-induced potentiation of macropinocytosis.

Fig. 5 |. HIF1A is necessary and sufficient for hypoxia-dependent upregulation of micropinocytosis.

a, Immunoblot analysis of indicated proteins in MIA PaCa-2-knockout cell lines treated with the prolyl-hydroxylase (PHD)-inhibitor FG-4592 (100 μM, 72 h). Vinculin is a loading control. FG-4592 is used to stabilize HIFs and confirm pathway disruption. b, Relative mRNA levels of HIF1A-target lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) in the indicated MIA PaCa-2-knockout cells treated with FG-4592 (100 μM for 72 h) compared to controls. c,d, Representative images (c) and quantification (d) of TMR-dextran (red) uptake in the indicated MIA PaCa-2-knockout cell lines under normoxia (21% O) or hypoxia (0.5% O2). Nuclei in blue. Scale bar, 10 μm. In d, data are normalized to normoxic controls. e,f, Representative images (e) and quantification (f) of TMR-dextran (red) uptake in MIA PaCa-2 cells transduced with indicated constructs under indicated conditions. Scale bar, 10 μm. In f, data are normalized to normoxic vector controls. g, Representative images from indicated MIA PaCa-2 xenografts showing macropinosomes (red), CK8+ tumour cells (green) and hypoxic areas (purple). Nuclei in blue. Dashed lines highlight hypoxic (purple) and normoxic (white) areas. Scale bar, 50 μm. h, Quantification of macropinocytic uptake in indicated MIA PaCa-2 xenografts in hypoxic (CK8+/Pimo+, red) and non-hypoxic (CK8+/Pimo−, grey) tumour areas. Data are normalized to normoxic areas in sgControl tumours. b,d,f–h, Bars represent mean ± s.e.m. b,d, n = 3 independent biological replicates; at least 500 (d,f) or 300 (g,h) cells were quantified in each biological replicate (n = 3). Statistical significance for all experiments was determined by a two-tailed unpaired t-test.

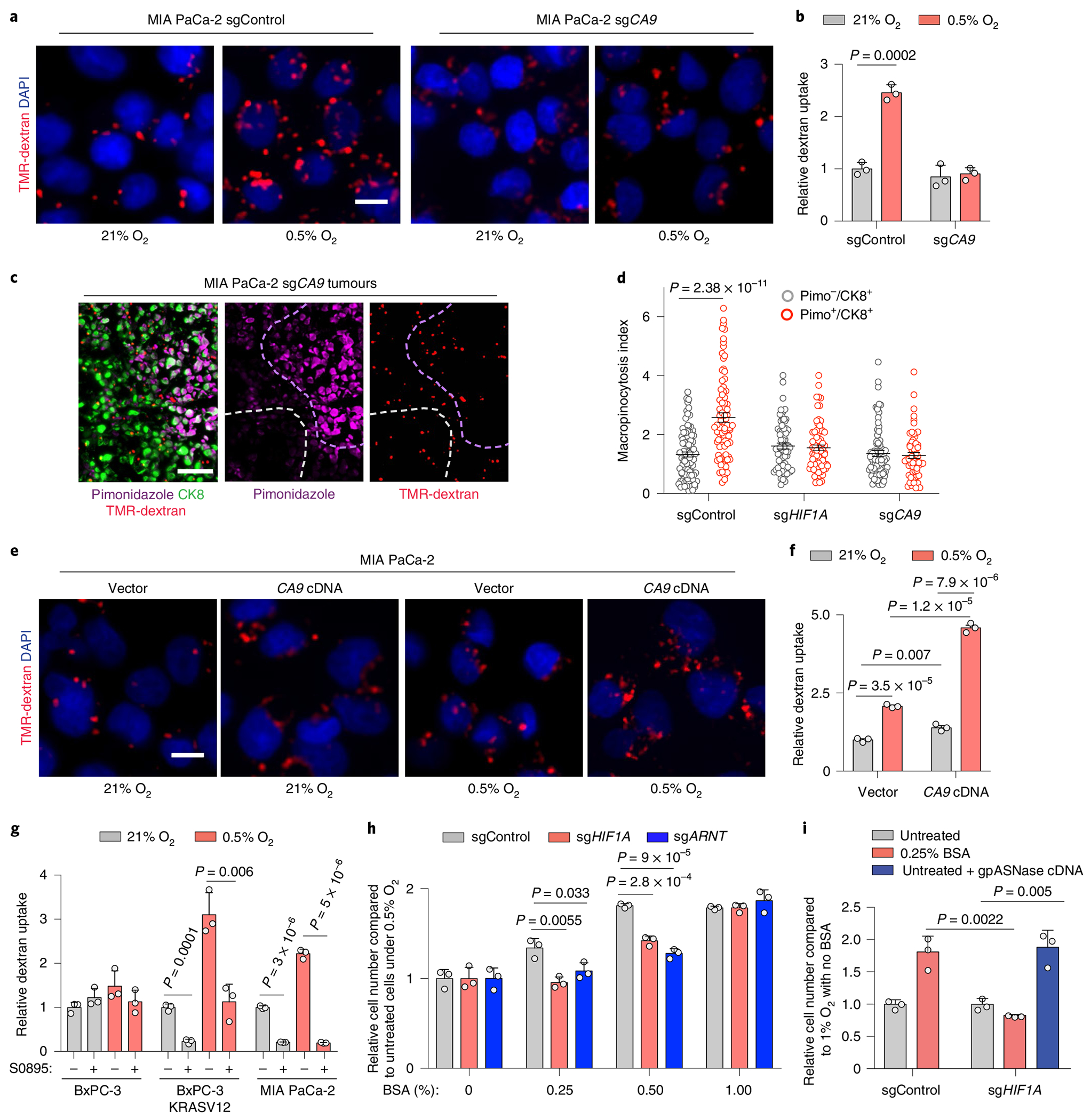

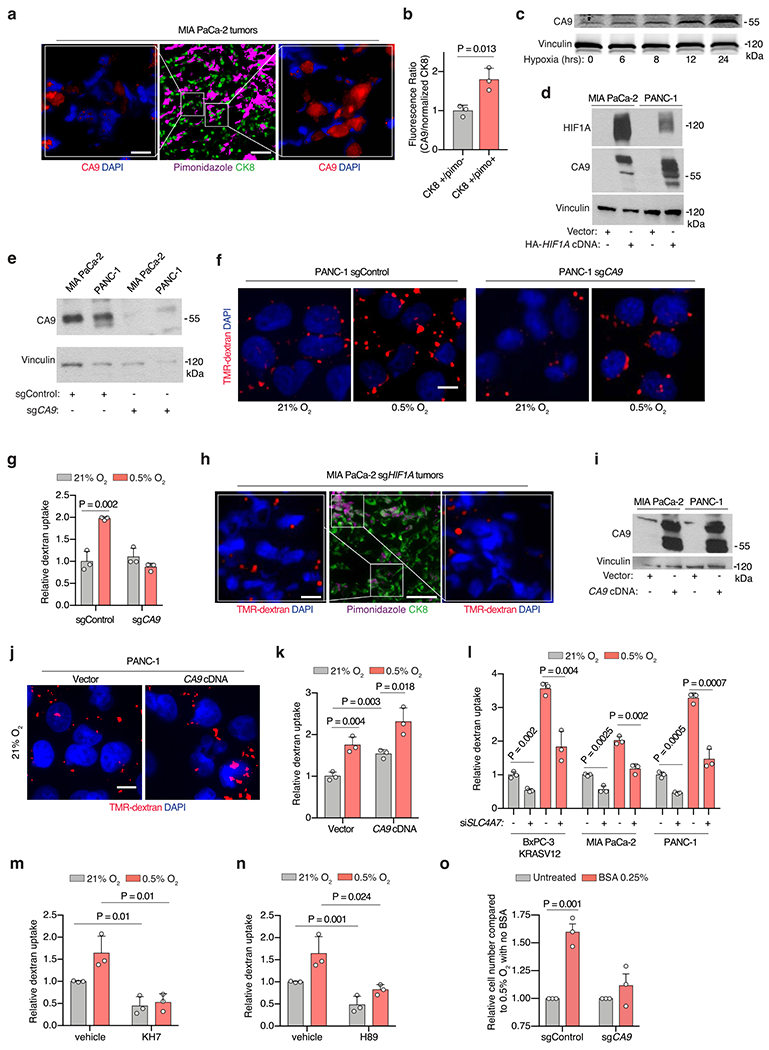

CA9 is required for HIF1A-induced macropinocytosis.

We next sought to determine the mechanism underlying the requirement of HIF1A for hypoxia-induced upregulation of macropinocytosis. Among the canonical HIF1A downstream targets is carbonic anhydrase IX (CA9), a transmembrane zinc metalloenzyme functioning as the catalyst of reversible hydration of carbon dioxide to bicarbonate ions and protons37,38. Indeed, we observed that CA9 is upregulated in hypoxic regions of mutant KRAS tumours (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b), both in cells cultured under hypoxia (Extended Data Fig. 7c) and in mutant KRAS cell lines expressing constitutively stable HIF1A P402A/P564A (Extended Data Fig. 7d). We have recently reported that oncogenic Ras-induced stimulation of macropinocytosis is dependent on the engagement of a bicarbonate signalling axis that is initiated by an increase in the expression of the electroneutral bicarbonate transporter SLC4A7 (ref. 39). The increase in bicarbonate influx that ensues leads to the activation of bicarbonate-dependent soluble adenylate cyclase (sAC) and its downstream effector protein kinase A40, which in turn leads to a series of alterations in membrane dynamics that are required for macropinocytosis39. Building on these findings, we proposed that CA9, by virtue of its capacity to increase bicarbonate availability, could play a critical role in coupling hypoxia to the upregulation of macropinocytosis. To test this hypothesis, we generated CA9-deficient mutant KRAS cells using CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing (Extended Data Fig. 7e) and assessed their macropinocytic activity in vitro and in vivo. In cells cultured under atmospheric oxygen conditions, CA9 loss had no impact on macropinocytosis levels. However, the potentiation of macropinocytosis observed under hypoxic conditions was abrogated in CA9-deficient cells (Fig. 6a,b and Extended Data Fig. 7f,g). The same CA9 dependence was observed in vivo, wherein the upregulation of macropinocytosis characteristic of hypoxic regions of the tumour failed to take place in tumour xenografts derived from HIF1A or CA9-knockout cells (Fig. 6c,d and Extended Data Fig. 7h). Last, overexpression of CA9 in KRAS mutant cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 7i) resulted in significant stimulation of baseline macropinocytosis activity, and further potentiated it in response to hypoxia (Fig. 6e,f and Extended Data Fig. 7j,k). Together, these results indicate that HIF1A-dependent induction of CA9 expression is an essential step in the process that enables mutant KRAS cells to upregulate their macropinocytic activity under hypoxic conditions.

Fig. 6 |. The HIF1A target CA9 is required for the upregulation of macropinocytosis in response to hypoxia.

a,b, Representative images (a) and quantification (b) of TMR-dextran (red) uptake in sgControl or sgCA9-transduced MIA PaCa-2 cells under indicated conditions. Nuclei are blue. Scale bar, 10 μm. Data are normalized to values in normoxic control cells. c, Representative images from sections of xenograft tumours derived from MIA PaCa-2 cells transduced with an sgRNA targeting CA9 showing macropinosomes (red), CK8+ tumour cells (green) and hypoxic areas (purple). Nuclei are blue. Dashed lines indicate hypoxic (purple) and normoxic (white) areas. Scale bar, 50 μm. d, Quantification of macropinocytic uptake in c for hypoxic (CK8+/Pimo+, red) and normoxic tumour areas (CK8+/Pimo−, grey) in tumours arising from cells transduced with an sgControl, sgHIF1A or sgCA9. Data are presented relative to those of non-hypoxic areas in sgControl-transduced tumours. e,f, Representative images (e) and quantification (f) of TMR-dextran (red) uptake in control or CA9 overexpressing MIA PaCa-2 cells under indicated conditions. Nuclei are blue. Scale bar, 10 μm. In f, data are normalized to values in normoxic controls. g, Quantification of dextran uptake in the indicated cell lines treated with the bicarbonate transporter inhibitor S0895 (15 μM) as shown under indicated conditions. Data are normalized to values in normoxic, untreated controls. h, Relative cell number of the indicated MIA PaCa-2 cell lines grown for 5 days under hypoxia (0.5% O2) with increasing concentrations of BSA (0–1%). Data are presented relative to hypoxic cells transduced with a control sgRNA and cultured without BSA. i, Relative cell number in the indicated MIA PaCa-2 cell lines transduced with a control vector or gpASNase cDNA grown for 5 days under hypoxia (1% O2) and in the absence or presence of BSA (0.25%). Data are presented relative to values obtained for sgControl hypoxic cells cultured without BSA. b,d,f,g, Bars represent mean ± s.e.m.; At least 500 (b,d,g) or 300 (f) cells were quantified in each biological replicate (n = 3). h,i, Bars represent mean ± s.d., n = 3 biologically independent samples. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired t-test.

The relevance of the catalytic product of CA9, bicarbonate, to this process is supported by the observation that small-interfering RNA-mediated knockdown of the bicarbonate transporter SLC4A7 or treatment of cells with a pan-bicarbonate transporter inhibitor, S0895, resulted in a partial or complete blockade of macropinocytosis under hypoxia, respectively (Fig. 6g and Extended Data Fig. 7l). Consistent with the engagement of the bicarbonate/macropinocytosis signalling axis by CA9 upregulation, treatment of cells with a soluble adenylate cyclase inhibitor (KH7) or a protein kinase A inhibitor (H89) resulted in the loss of the potentiating effect of hypoxia on macropinocytosis (Extended Data Fig. 7m,n).

Hypoxia-induced macropinocytosis promotes metabolic fitness.

We have previously shown that the deleterious effect of amino acid deprivation on the growth of mutant KRAS cells can be rescued by supplementing the growth medium with albumin8,41. Furthermore, we and others have demonstrated that albumin must be supplied at near physiological levels (1–3%) to support the survival and growth of mutant KRAS cells under these conditions. Since the rescuing capacity of albumin in these settings is dependent on its macropinocytic uptake, we reasoned that hypoxia-induced potentiation of macropinocytosis could reduce the threshold levels of albumin required for cell growth. To test this idea, we assessed the dependence of cell growth on HIF1A-CA9 axis under varying concentrations of albumin. We found that loss of HIF1A, ARNT or CA9 significantly decreased the proliferation of mutant KRAS cells when subjected to hypoxia in the presence of subphysiological levels of albumin (Fig. 6h and Extended Data Fig. 7o). Notably, this antiproliferative effect could be restored by the expression of gpASNase (Fig. 6i), supporting the limiting role of aspartate under hypoxic conditions.

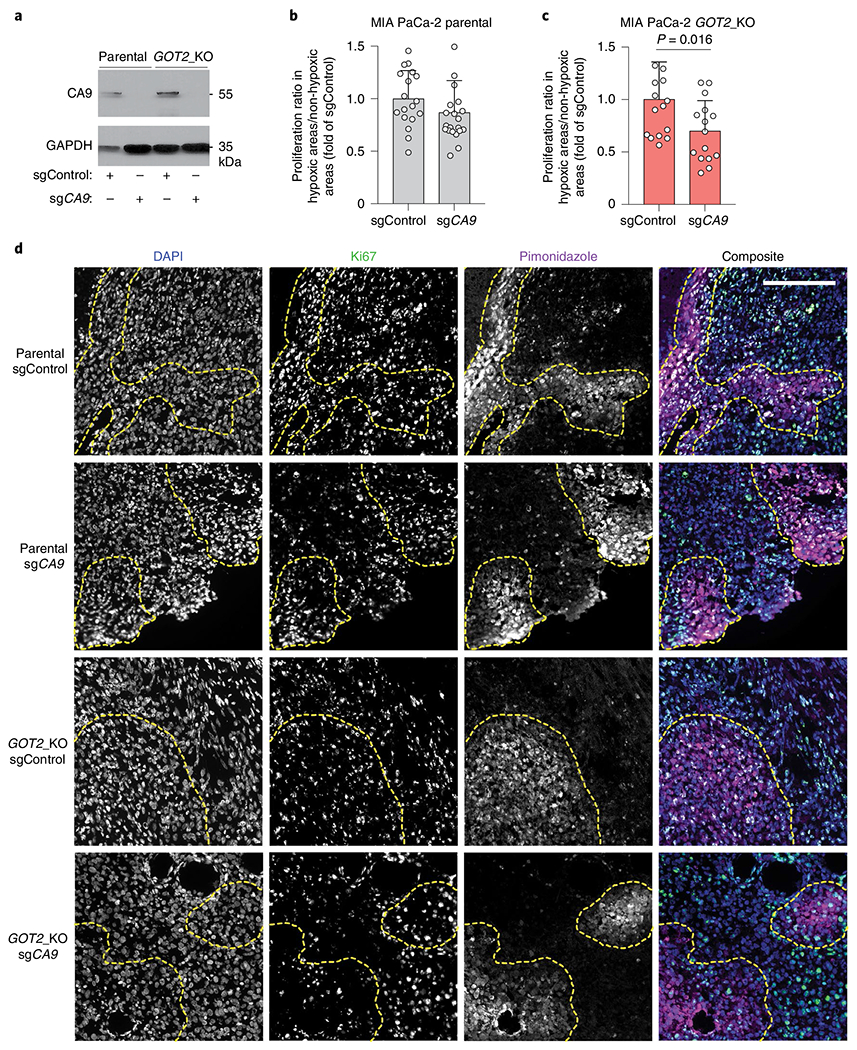

Fig. 7 |. Loss of CA9 inhibits hypoxic cancer cell growth under aspartate limitation.

a, Immunoblot analysis of CA9 in the indicated MIA PaCa-2 cell lines transduced with a control sgRNA or an sgRNA targeting CA9. GAPDH was used as a loading control. b,c, Quantification of ratio of percent Ki67 positive cells in hypoxic (pimonidazole positive) to neighbouring normoxic (pimonidazole negative) regions in MIA PaCa-2 parental tumours (b) MIA PaCa-2 GOT2 knockout tumours (c) transduced with a control sgRNA (sgControl) or sgCA9. Data are presented relative to values obtained for sgControl tumours. d, Representative immunofluorescent images of tumour xenografts derived from indicated MIA PaCa-2 cells stained for DAPI (nucleus), Ki67 (proliferation) and pimonidazole (hypoxia marker). Scale bar, 200 μM. c,d, Bars represent mean ± s.e.m. n = total numbers of fields evaluated from all five tumours analysed, 18, 20, 14 and 15 for each group, respectively. Statistical significance determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

We next sought to determine the contribution of CA9-mediated enhancement of macropinocytosis to tumour cell fitness under hypoxic conditions. Given that pancreatic tumours display a high degree of inter- and intratumoral heterogeneity in size and numbers of hypoxic regions, we compared the proliferation of tumour cells in hypoxic and neighbouring normoxic regions within the same tumour. To assess this in the context of aspartate limitation, we first attempted to knockout CA9 in GOT1/GOT2 double-knockout cells. However, the slow growth of these aspartate auxotrophic cells was not compatible with any further genetic manipulations. Instead, we resorted to using GOT2 null MIA PaCa-2 cells, in which CA9 was knocked out (Fig. 7a). Our analysis revealed that loss of CA9 significantly decreased the proliferative capacity of GOT2-knockout cells, but not that of the parental controls, in hypoxic tumour regions (Fig. 7b–d). These results probably represent an underestimate of the fitness advantage conferred by CA9, since they have been attained in the context of intact GOT1 function that allows for partial aspartate synthesis. Altogether, these results identify a critical role for HIF1A/CA9-driven stimulation of macropinocytosis in the metabolic adaptation of pancreatic tumour cells to the hypoxic tumour environment.

Discussion

As an essential substrate for more than 140 metabolic reactions, oxygen serves many critical anabolic and catabolic functions in mammalian cells. To overcome metabolite limitations imposed by hypoxia, most cancer cells engage stress-adaptive responses and use alternative nutrient sources. In this study, we explored the nature of these adaptive responses in the context of aspartate availability. While the limiting role of aspartate under both hypoxic and respiration impaired conditions has been established11,16,18, our results reveal that cancer cells use distinct subcellular routes of aspartate synthesis to accommodate each stress. PDAC cells depend on mitochondrial aspartate synthesis via GOT2 under hypoxia, whereas they rely on cytoplasmic aspartate production in response to pharmacologic ETC inhibition. This is probably due in part to differences in compartmentalized NAD+ limitation under these distinct conditions, but also may be mediated by hypoxia-specific downstream effectors. The use of compartment-specific pathways as an adaptation response to nutrient deprivation has previously been described for one carbon metabolism42, and may represent a general strategy exploited by cancer cells to enhance their metabolic plasticity.

As the limiting role of aspartate has been universally observed in culture, aspartate transaminases have been previously suggested as potential therapeutic targets5. However, our findings demonstrate that implanted PDAC tumours can partly overcome the complete loss of de novo aspartate production. This apparent discrepancy can be attributed to both cell extrinsic and cell intrinsic factors: neighbouring cells secrete pyruvate, thereby providing reducing equivalents to cancer cells; and cancer cells themselves upregulate macropinocytosis to improve aspartate acquisition. Given the presence of multiple pathways to address aspartate limitation, the relative contribution of each to tumour growth needs to be carefully assessed before considering this pathway for anticancer therapies.

While this study focuses on the acquisition of aspartate through macropinocytosis under limiting oxygen conditions, macropinocytosis itself is a non-selective bulk-fluid uptake process, and therefore probably would enhance the capacity of hypoxic tumour cells to import other extracellular solutes and macromolecules. Consistent with this notion, previous work has indicated that lipid scavenging is stimulated by hypoxic culture conditions and can be phenocopied in normoxic cells by RAS mutation43. Thus, increased macropinocytosis in the context of RAS mutation and its exacerbation by hypoxia would be predicted to enhance lipid scavenging, fuelling membrane replication and cell division. In addition, a low-oxygen environment causes necrosis, leading to the accumulation of necrotic cellular debris that can enter cells via macropinocytosis44 and provide a robust source of important bioenergetic substrates. Lastly, the adaptive response of cells to hypoxia involves inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)45. In oncogenic RAS transformed cells, inhibition of mTORC1 has been shown to increase the endolysosomal-mediated catabolism of proteins that enter the cells via macropinocytosis28. Collectively, hypoxic reprogramming of nutrient scavenging via macropinocytosis emerges as a versatile mechanism by which mutant RAS tumours could improve metabolic fitness.

We have previously shown that bicarbonate availability couples oncogenic RAS signalling to the molecular machinery that controls macropinocytosis39. The present study identifies this coupling mechanism as the point of intersection between hypoxia and macropinocytosis through the upregulation of CA9 and the ensuing increase in bicarbonate production. Significantly, high levels of CA9 expression in PDAC tumours have been shown to be associated with reduced survival46. Moreover, both small molecules and antibodies targeting CA9 are currently at various stages of clinical development47. Therefore, the link between CA9 expression and nutrient uptake may represent a new targetable vulnerability of mutant RAS tumours. It is likely, however, that inhibition of this enzyme will need to be coupled with perturbation with other anabolic pathways to yield effective treatments for PDAC.

Methods

This research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. All study protocols were approved by the relevant regulatory boards at each institution.

Cell lines, compounds and constructs.

Cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection, maintained under 5% CO2 at 37 °C and tested for mycoplasma every 2 months. HY15549 cells were a gift from N. Bardeesy. KP lung cells were a gift from T. Papagiannakopoulos. Human pancreatic stellate cells (hPSCs) were obtained from R. Hwang.

For generation of the lentiviral knockout constructs, annealed oligos were cloned using a T4 ligase (NEB) into lentiCRISPR-v2 vector or into a lentiCRISPR-v1-GFP and lentiCRISPR-v1-RFP for generation of GOT1/GOT2-double-knockout cell lines. The same protocol was used to clone sgRNAs for the competition assays targeting control regions (sgINTERGENIC) or aspartate-malate shuttle genes. sgRNA-resistant GOT1 and GOT2 cDNAs; and cyto-lbNOX, mito-lbNOX, gpASNase and CA9 cDNAs were synthesized as gBlock fragments (IDT) and cloned into PMXS-IRES-Blast vector by Gibson assembly. SLC16A1 and SLC1A3 cDNAs cloned into PMXS-IRES-Blast were previously generated. Constitutively stable HIF1A construct was obtained from Addgene (HA-HIF1alpha P402A/P564A-pcDNA3)35 and amplified by PCR.

For all oligo sequences, see Supplementary Table 1 and for a reagents list, see Supplementary Table 2.

Generation of knockout and cDNA overexpression cell lines.

To generate knockout lines, lentiviral vector was transfected into human embyronic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells with lentiviral packaging vectors VSV-G and Delta-VPR using XtremeGene transfection reagent (Roche). After 24 h, media was replaced. Then 48 h after transfection, the viral supernatant was collected and filtered using a 0.45 μm filter. Cells to be transduced were plated in six-well format and infected with media containing the virus and 8 mg ml−1 of polybrene. A spin infection was performed by centrifugation at 2,200 r.p.m. for 1.5 h. Next, 48 h after infection, selection of transduced cells was initiated by addition of puromycin. For generation of single-knockout cells for GOT1 and GOT2 HY15549 and MIA PaCa-2 lines, cells were raised from a single clone isolated by serial dilution in a 96-well plate containing 0.1 ml of media per well. After 3 weeks, the resultant clones were validated by western blot and expanded. GOT2-knockout cells were generated, expanded and maintained in RPMI 1640 media containing 1 mM pyruvate, except during proliferation experiments, in which low pyruvate media (50 μM) was used.

For generation of GOT1/2-double-knockouts, cells were transduced with lentiviral GFP-sgGOT2 and next day with lentiviral RFP-sgGOT1. Double GFP/RFP positive cells were then single-cell sorted using a BD FACS Aria and expanded for 3 weeks in high aspartate RPMI media (20 mM Aspartate). Absence of GOT2 and GOT1 was validated by western blot and glutamine isotope labelling experiments. MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 HIF1A, ARNT and CA9-knockout cell lines were generated by the same procedure but mixed cell populations were used.

For overexpression of cDNAs, retroviral vectors with indicated cDNAs were transfected with retroviral packaging plasmids Gag-pol and VSV-G into HEK293T cells. For virus collection and transduction, we followed the same procedure used with lentiviral vectors. Selection of transduced cells was achieved by addition of blasticidin.

For generation of MIA PaCa-2 Rho(0) cells, parental cells were maintained low confluency in RPMI media containing pyruvate (1 mM) and uridine (100 μM) in the presence of ethidium bromide (1:10,000) for 30 days.

HeLa and BxPC-3 stable cell lines with doxycycline-inducible expression of FLAG-KRAS(G12V) or T7-KRAS(G12V) were generated with lentiviral particles. Cells were transduced with lentiviral particles containing pTRIPZ-FLAG-K-Ras(G12V), selected with puromycin (2 μg ml−1) for 72 h and maintained in 10% tetracycline-free foetal bovine serum (FBS) (Clontech).

Proliferation assays.

Cell lines were plated in six-well plates at 1,000–2,500 (HY15549) or 15,000 (MIA PaCa-2 and PA-TU-8898-T) cells per well in standard conditions. Next day, cells were treated with ETC inhibitors (Antimycin A or piericidin), left untreated (normoxia) or cultured in a hypoxia chamber (Baker INVIVO) set to 0.5% O2. For hypoxic conditions, culture media was equilibrated before use. After 5–6 days of growth, cells were trypsinized and counted (Beckman Z2 Coulter Counter with a size selection setting of 8–30 μm). All experiments with GOT2_KO cells were performed in media containing 50 μM pyruvate.

Experiments using conditioned media from human pancreatic stellate cells (hPSCs) were performed as previously described21. Briefly, hPSCs were maintained in RPMI media and plated in 10-cm dishes at 1 × 106 cells per plate. The next day, media was changed. After 48 h, conditioned media was collected and filtered (0.45 μm filter).

For most of the BSA rescue experiments, albumin, bovine serum, fraction V, fatty acid-free, nuclease- and protease-free (Sigma, no. 126602) were used. Cells were plated in six-well plates in BSA-free media. Next day, media was aspirated and fresh media ± BSA was added (3 ml per well), with or without ETC inhibitors.

For BSA rescue experiments of CA9-knockout cell lines under hypoxia, cells were seeded at a density of 1,000–1,500 cells per well of a 96-well plate and incubated under normoxia for 24 h. Media was then supplemented with 0.5% fraction V BSA (Calbiochem). Cells were incubated for 5 d under either normoxia or hypoxia. Cells were then fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde, washed and incubated in a SYTO 60 red fluorescent nucleic acid stain (1:5,000 dilution in 0.1% Triton/PBS) for 30 min at room temperature. Plates were scanned and imaged using a Licor Odyssey Classic imager and the Odyssey v.2.1 software.

For induction of oncogenic KRAS expression before proliferation experiments in BxPC-3 with TET-inducible FLAG-KRAS(G12V), cells were treated with doxycycline (1 μg ml−1) for 48 h before plating 20,000 cells per well in the presence of 0.1 μg ml−1 of doxycycline for 7 d. Doxycycline was added fresh every 3 d.

Micrograph pictures of endpoint in proliferation experiments were taken with Primovert microscope (Zeiss).

Metabolite profiling and isotope tracing.

For the initial metabolite profiling experiment in KP PDAC cell lines, each indicated cell line (50,000 cells per replicate for HY15549; 100,000 cells per replicate for MIA PaCa-2 and AsPC-1) was cultured as triplicates in six-well plates. After 12 h, cells were left untreated at normoxia (21% O2), treated for 20 h with antimycin A (HY15549 30 nM; AsPC-1 50 nM; MIA PaCa-2 50 nM) or grown in a hypoxia chamber at 0.5% O2 with equilibrated media.

For glutamine tracing experiments in HY15549 and MIA PaCa-2 parental and GOT1/2 DKO lines, 50,000–100,000 cells per well were plated in RPMI media containing 20 mM aspartate. After 24 h, wells were thoroughly washed with PBS five times to remove all the aspartate, before addition of RPMI with dialysed FBS and no aspartate. After additional 24 h, media was changed and replaced with 2 ml of custom RPMI media lacking glutamine and supplemented with [U-13C]-Glutamine (500 μM). Cells were cultured in this media for an additional 8 h before their collection and isotope labelling analysis of aspartate and citrate.

For metabolite profiling under hypoxia or ETC inhibition in the presence or absence of BSA, MIA PaCa-2 parental cells were plated at low confluency (200,000 cells in 10-cm dishes in triplicates) in regular RPMI media. Next day, media was aspirated and fresh normoxic or hypoxia media with and without BSA (2%) were added. After 24 h under these culture conditions, metabolite extraction was performed. For ETC inhibition profiling, same procedure was used but adding piericidin (150 nM) to each condition for 24 h.

For metabolite profiling of PDAC cells auxotroph for aspartate on BSA addition, MIA PaCa-2 GOT1/2 DKO cells were plated at low confluency (200,000 cells in 10-cm dishes) in either RPMI media or RPMI media with BSA 2%, both prepared with dialysed FBS. After 48 h under these culture conditions, samples were collected and metabolite analysis was carried out.

In all experiments, at the time of collection cells were washed three times with 1–3 ml of cold 0.9% NaCl and polar metabolites extracted in 1 ml of cold 80% methanol containing internal standards (MSK-A2-1.2, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.) by scraping the cells in each well on ice and collecting the content in 1.5 ml tubes. After 10 min of extraction by vortexing and centrifugation for 10 min at 10,000g and 4 °C, samples were nitrogen dried and stored at −80 °C. Analysis was conducted on a QExactive benchtop orbitrap mass spectrometer equipped with an Ion Max source and a heated electrospray ionization II probe, which was coupled to a Dionex UltiMate 3000 UPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). External mass calibration was performed using the standard calibration mixture every 7 d.

Dried polar samples were resuspended in 100 μl of water and 2 μl were injected into a ZIC-pHILIC 150 × 2.1 mm (5 μm particle size) column (EMD Millipore). Chromatographic separation was achieved using the following conditions: buffer A was 20 mM ammonium carbonate, 0.1% ammonium hydroxide; buffer B was acetonitrile. The column oven and autosampler tray were held at 25 and 4 °C, respectively. The chromatographic gradient was run at a flow rate of 0.150 ml min−1 as follows: 0–20 min, linear gradient from 80 to 20% B; 20–20.5 min, linear gradient from 20 to 80% B and 20.5–28 min, hold at 80% B. The mass spectrometer was operated in full-scan, polarity switching mode with the spray voltage set to 3.0 kV, the heated capillary held at 275 °C and the heated electrospray ionization probe held at 350 °C. The sheath gas flow was set to 40 units, the auxiliary gas flow was set to 15 units and the sweep gas flow was set to 1 unit. The MS data acquisition was performed in a range of 70–1,000 m/z, with the resolution set at 70,000, the AGC target at 10 × 106 and the maximum injection time at 20 ms. Relative quantitation of polar metabolites was performed with XCalibur QuanBrowser v.2.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a 5 ppm mass tolerance and referencing an in-house library of chemical standards. For stable isotope tracing studies, fractional labelling was corrected for natural abundance using an in-house algorithm48.

Metabolite levels were normalized to the total protein amount for each condition.

Principal component analysis was carried out on whole-cell metabolite profiles of three PDAC cell lines under normoxic, antimycin A and hypoxic conditions. The principal component analysis is centred and scaled relative to the samples.

For measurement of metabolites in the media of hypoxic cells, an aliquot of spent media (20 μl) was diluted with cold 80% methanol (80 μl), vortexed for 10 min and spin down for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was dried down and resuspended in 600 μl of cold 80% methanol. The samples were vortexed for 20 s, centrifuged for 20 min at (20,000g, 4 °C) and 5 μl of the supernatant was injected onto the liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) in a randomized sequence. Polar metabolites were separated on a ZIC-pHILIC column and LC–MS analysis was carried out. Relative quantitation of polar metabolites was performed with Skyline Daily (MacCoss Laboratory Software) using a 2 ppm mass tolerance and referencing an in-house library of chemical standards. A stock solution containing 2,000 μM lactate, 200 μM glutamine, 20 μM of pyruvate, aspartate, lysine and histidine was prepared in 80% methanol. An external calibration curve was prepared from serial dilution of this stock solution into 80% methanol, by a factor of 2, yielding ten working stock solutions. The working stock solutions (5 μl) were injected onto the LC–MS in the order of increasing concentration and processed with the LC–MS methods used for the spent media samples. The concentration points generating a linear response on the mass spectrometer were fitted to a linear regression equation (intercept set to 0) and the resulting slope was used to estimate the concentration of lactate, pyruvate, glutamine, aspartate, histidine and lysine in the spent media samples.

Immunoblotting.

Cell pellets were washed twice with ice-cold PBS before lysis in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 150 NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2% SDS, 0.1% CHAPS) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche). After sonication of each cell lysate and centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C and 20,000g, supernatants were collected and their protein concentrations were determined by using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific) with BSA as a protein standard. Depending on the experiment, samples were resolved on 8, 12, 12–16 or 16% SDS–PAGE gels and transferred to Immobilon-P polyvinyl difluoride membranes (Millipore) with 0.45 μm (CA9) or 0.2 μm (all other proteins) pore size. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk (for analysis of GOT1, GOT2, ACTB (actin beta), FLAG, T7, SLC1A3, SLC16A1 and total oxidative phosphorylation) or BSA 5% (for HIF1A, ARNT, CA9 and vinculin) and analysed by immunoblotting using standard protocols.

Mouse studies.

All animal studies were approved by the respective Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUCs) at Rockefeller University and New York University Grossman School of Medicine and animal care was conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines. All mice were maintained on a standard light-dark cycle with food and water ad libitum.

The maximum tumour size allowed is 2 cm at the largest diameter or 10% of the animal’s body weight; this maximum size was not exceeded.

Xenograft tumours were initiated by injecting the following number of cells in DMEM with 30% Matrigel:

0.5 million cells per 100 μl for mouse HY15549 parental and individual GOT-knockout cell lines.

3 million cells per 100 μl for MIA PaCa-2 parental and individual GOT-knockout cell lines.

5 million cells per 100 μl for HY15549 and MIA PaCa-2 GOT1/2 DKO cell lines.

3 million cells per 100 μl for MIA PaCa-2 parental and GOT2-knockout cells transduced with sgControl or sgCA9.

After injections in the left and right flanks of male and female 6–9 week-old NOD SCID gamma (NSG) mice (Taconic), tumours were grown for 3–6 weeks.

For orthotopic pancreas injections, we followed previously described protocols49. Briefly, a small incision was made on the upper left quadrant of the abdomen and the pancreas was externalized. Then 100,000 cells in 50 μl of PBS with 50% Matrigel were injected into the pancreatic tail with insulin syringes (29-gauge needle, BD).

For metabolite profiling of MIA PaCa-2 DKO tumours, animals were euthanized and tumours were extracted and immediately lysed in cold 80% methanol containing internal standards by using a Bead Ruptor 24 (Omni International) by six cycles of 20 s at 6 m s−1. Supernatants were collected after 10 min of centrifugation at 10,000g and 4 °C, nitrogen dried and analysed for the content of carbon labelled aspartate.

Real-time PCR assays.

RNA was isolated by an RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and samples were analysed as previously described50. Briefly, RNA was spectrophotometrically quantified and equal amounts were used for cDNA synthesis with the Superscript II RT Kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR analysis was carried out on an ABI Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with the SYBR green Mastermix (Applied Biosystems).

For primer sequences, see Supplementary Table 1.

Results were normalized to ACTINB.

CRISPR-based screen.

The highly focused metabolism sgRNA library used for CRISPR screens in HY15549 was generated as previously described and contains sgRNAs targeting the mouse genes corresponding to our previously described highly focused metabolism human library51. Briefly, the plasmid pool was used to generate a lentiviral library containing five sgRNAs per gene target. This viral supernatant was tittered in HY15549 cells by infecting target cells at increasing amounts of virus in the presence of polybrene (8 μg ml−1) and by determination of cell survival after 3 d of selection with puromycin. Then 2 × 106 of each cell type were infected at a multiplicity of infection rate of 1 before selection with puromycin for 3 d. An initial pool of 2 million cells were collected. Infected cells were then cultured for 14 population doublings at 21% O2, 0.5% O2 or in the presence of an ETC inhibitor, piericidin (40 nM). After this, 2 million cells were collected and their genomic DNA extracted by a DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (QIAGEN). For amplification of sgRNA inserts, we performed PCR using specific primers for each condition. PCR amplicons were then purified and sequenced on a NextSeq 500 (Illumina). Sequencing reads were mapped and the abundance of each sgRNA was measured. Gene score is defined as the median log2 fold change in the abundance between the initial and final population of all sgRNAs targeting that gene. A gene score lower than −1 is considered as significantly essential.

sgRNA competition assay in vitro and in vivo.

Five control sgRNAs targeting intergenic regions, and five sgRNAs targeting GOT1, GOT2, MDH1, MDH2 or PC were cloned into linearized lentiCRISPR-v2 vector and transformed in NEB competent Escherichia coli. Each plasmid was then pooled at equal concentrations and used for lentivirus production as previously described. Each cell line was infected and selected with puromycin for 3 d before being in vitro cultured or, in the case of PANC-1, also injected subcutaneously or orthotopically in the pancreas of male and female 6–9 week-old NSG mice. Tumours were collected after 2–4 weeks of growth. An initial pool of each sample was taken for normalization. After 14–21 days, gDNAs were isolated and amplified by PCR. PCR amplicons were then sequenced on a NextSeq 500 (Illumina). Guide scores were calculated as median log2 fold change in the abundance between the initial and final population of that sgRNA similar to standard CRISPR screens.

The KP PDAC PDX model for in vivo competition assay was described previously49. Briefly, low passage PDX pancreatic tumour was chopped finely and digested with collagenase type IV for 30 min. Next, mouse cells were removed from the single-cell suspension via magnetic-associated cell sorting using the Mouse Cell Depletion Kit (130-104-694, Miltenyi), resulting in a single-cell suspension of predominantly pancreatic cancer cells of human origin. Ten million cells of this PDX suspension were transduced with the human aspartate-malate shuttle lentiviral particles and subsequently injected subcutaneously in PBS with 50% Matrigel in 10-week-old male NSG mice 24 h after infection. PDX tumours were collected after 3 weeks of growth, their gDNA isolated and amplicons were amplified by PCR and sequenced. The PDX tumour was obtained from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The protocol was approved by all site IRB (MSKCC Institutional Review Board/Privacy Board (protocol 10-018A and 06-107A) and The Rockefeller University’s Institutional Review Board (protocol ERA-0959)) and all patients signed informed consent before sample acquisition.

In vitro macropinocytosis assay.

Cells were seeded onto glass coverslips in a 24-well plate. Forty-eight hours after seeding, cells were subjected to serum starvation. For 24-h hypoxia experiments, cells were grown in normoxia (21% O2) for 24 h, then incubated in a hypoxia chamber set at <1% O2, Whitley H35 Hypoxystation (Don Whitley Scientific), for 24 h before the assay. Macropinosomes were quantified as previously described8.

In vivo macropinocytosis assay.

Two million cells of corresponding MIA PaCa-2 cell lines were resuspended in 50% Matrigel (Corning) and injected subcutaneously into the flanks of 7-week-old female nude mice (NCRNU Taconic). When tumours attained a volume of 500 mm3, pimonidazole (Hypoxyprobe, pimonidazole hydrochloride, HP-1000) was used to assess hypoxia in vivo and TMR-dextran was used to label macropinosomes in vivo as previously described8. Next, 1.5 mg of pimonidazole dissolved in PBS was injected intraperitoneally using an insulin syringe. Next, 100 μl of 10 mg ml−1 TMR-dextran was then injected intratumorally using an insulin syringe. Both pimonidazole and TMR-dextran were allowed to circulate for 90 min before euthanasia. Mice were euthanized with CO2, and cervical dislocation as a secondary method according to approved IACUC protocols. Tumours were harvested and rapidly frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT Compound. Frozen tumours were sectioned and stained for CK8, pimonidazole and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Macropinocytosis was quantified as previously described8.

In vitro DQ-BSA assay.

Cells were seeded onto glass coverslips in a 24-well plate. Forty-eight hours after seeding, cells subjected to serum starvation. Cells were incubated for 30 min in DQ Green BSA diluted to 0.05 mg ml−1 in serum-free media, then chased with serum-free media free of DQ-BSA for 1.5 h. Cells were then washed with ice-cold PBS and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde. Cells were DAPI stained for nuclei and mounted onto glass slides with DAKO mounting medium (Agilent). Images were captured at ×20 magnification using a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope and analysed using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, NIH). Background subtraction was applied, and a threshold was set to detect DQ-BSA fluorescence.

Immunofluorescence.

Frozen tumour sections on glass slides or cells seeded on glass coverslips were washed in PBS and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Blocking was done using 10% goat serum and 2% BSA in PBS for 1 h at room temperature for tumour sections. Blocking for in vitro samples included a permeabilization step and was done using Triton X-100 (1:1,000), 1% goat serum and 3% BSA in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation in primary antibody for 2 h at room temperature, samples were washed and incubated with fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies. Images were captured at ×20 or ×60 magnification using the Nikon Eclipse microscope and analysed using the ImageJ software (NIH). Hypoxic areas of tumour sections were identified by setting a threshold for pimonidazole fluorescence. The macropinocytic index within areas of high pimonidazole and lower pimonidazole was calculated by dividing the total area of macropinosomes by the total area of CK8 positive tumour cells. For quantifying the ratio of the percent of Ki67 positive cells in hypoxic regions versus normoxic regions, we conducted overall cell counts in hypoxic areas of tumour sections and in neighbouring normoxic areas. The number of Ki67 positive cells were then scored in each region in a blinded fashion. From these numbers, a percentage of Ki67 positive cells was calculated for each region. Then, a ratio of these values in hypoxic/normoxic regions was plotted. At least 17 regions were chosen at random from among all the tumours in each group were analysed, with a least one image from each tumour per group, as cross sectional tumor size allowed. The following primary antibodies were used: CK8 (1:180) (Millipore MABT329), pimonidazole (1:20), Ki67 (1:400) and CA9 (1:100). The following secondary antibodies were used: Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor 488 goat antirat (1:500).

Statistics and reproducibility.

GraphPad PRISM v.7 and Microsoft Excel v.15.21.1 software were used for statistical analysis. XCalibur QuanBrowser v.2.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for metabolomic analyses and ImageJ (NIH) for image analysis. Error bars, P values and statistical tests are reported in the figure captions. All experiments (except metabolite profiling experiments, in vivo tumour dextran assays and imaging analysis for Ki67/pimonidazole colocalization ratio, which were done once) were performed at least twice with similar results. Both technical and biological replicates were reliably reproduced.

Reporting summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Hypoxia and ETC inhibition trigger similar metabolic signatures in PDAC cells.

(a) Individual sgRNA scores for GOT2 under indicated conditions. (b) Heat map showing fold changes (log2) of polar metabolites significantly changed when comparing normoxic to hypoxic culture conditions. (c) Immunoblot analysis of GOT2. ACTB is a loading control. (d) Fold change in cell number (log2) of MIA PaCa-2 GOT2KO cell line expressing indicated constructs grown under indicated conditions for 5 days. (e) Common metabolite changes across three PDAC cell lines upon ETC inhibition. (f) Principal component analysis (PCA) of metabolic changes in indicated PDAC cell lines under indicated conditions. (g) Ranks of metabolites most significantly changed (p value < 0.01, dotted lines) across 3 PDAC cell lines under indicated conditions. Metabolites significantly accumulated (blue) or depleted (pink) under both conditions are in the lower left quadrant (right). (h) Top scoring genes and their differential gene scores in HY15549 cells treated with piericidin (Pier.) compared to untreated cells. (i) Individual sgRNA scores for GOT1 in HY15549 cells in indicated conditions. (j) Immunoblot analysis of GOT1 in indicated cell lines expressing indicated sgRNAs. ACTB is a loading control. (k) Fold change in cell number (log2) of indicated HY15549 cell lines expressing indicated constructs for 5 days in the presence or absence of Pier., 20 nM. (l) Fold change in cell number (log2) of indicated cell lines expressing indicated cDNAs grown for 5 days in the presence or absence of Pier., 20 nM. (m) Relative fold change in cell number of indicated parental PDAC cell lines transduced with indicated cDNAs grown for 5 days under indicated conditions; Pier., 20-100. (n) Fold change in cell number (log2) of indicated HY15549 cell lines transduced with indicated vectors grown for 5 days under indicated conditions; Pier. 50 nM. a, i, bars represent individual sgRNA scores; d, k, l, m, n, Bars represent mean ± s.d. d, k, l, m, n, n = 3 biologically independent samples. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Mitochondrial NAD+ is limiting for PDAC cell proliferation under hypoxia.

(a) Immunoblot analysis of FLAG-tagged cytoplasmic (cyto-) and mitochondrial (mito-) LbNOX heterologous expression in the indicated cell lines. ACTB was used as a loading control. (b) Fraction of labelled aspartate (left) and citrate (right) derived from labelled glutamine in control and cyto- or mito-LbNOX expressing HY15549 cells cultured for 8 h with [U-13C]-Glutamine (500 μM) with piericidin treatment (50 nM) or under 0.5% oxygen. Colours indicate mass isotopomers. (c) Expression of LbNOX enzymes rescues proliferation of MIA PaCa-2 cells under piericidin treatment (50 nM), whereas only mito-LbNOX expression rescues proliferation under 0.5% O2. Data is shown as fold change in cell number in the indicated cell lines grown for 5 days relative to untreated cells cultured at 21% O2. (d) Fraction of 13C-labeled aspartate (m + 4) and malate (m + 4) in HY15549 parental and GOT2-knockout cells transduced with a control vector or an sgRNA-resistant GOT2 cDNA cultured for 24 hours under hypoxia in the presence of [U-13C]-L-glutamine (1 mM). (e) Relative fold change in cell number of HY15549 GOT2-knockout cells transduced with a control vector or the indicated cDNAs grown for 5 days under hypoxia (0.5% O2) to those cultured under normoxia (21% O2). b-e, Bars represent mean ± s.d. b-e, n = 3 biologically independent samples. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Aspartate synthesis by GOTs is essential in culture but redundant for in vivo tumor growth.

(a) Immunoblot analysis of indicated proteins and cell lines with vinculin loading control. (b) Weights of subcutaneous tumor xenografts from MIA PaCa-2 cells transduced with indicated vectors. (c) In vivo sgRNA competition assay scheme (left). Gene scores for indicated conditions (right). Each dot represents one sgRNA (n = 5 tumours). (d) Gene scores for in vivo sgRNA competition assay performed in KRAS-mutant PDAC patient-derived xenografts (PDX). Each dot represents an sgRNA (n = 5 subcutaneous tumors). (e, f) Fold change cell number of GOT2-KO HY15549 cells transduced with indicated vectors grown 5 days under indicated conditions. Pyruvate (Pyr). (g) Fold change in cell number of HY15549 cells grown 5 days in regular or conditioned media from hPSCs (hPSC CM) with or without monocarboxylate transporter inhibitor AR-C155858 (5 μM). (h) Immunoblot analysis of indicated cells under indicated conditions with vinculin as loading control. (i). Representative bright-field micrographs of indicated cells grown 6 days in the indicated media. Scale bar = 50 μM (left). Quantification graph (right); aspartate (20 mM). (j) Weights, images, and immunoblot analysis of indicated tumors with vinculin loading control (right). (k) Relative aspartate abundance normalized to lysine levels of established xenografts from indicated cells transduced with indicated vectors. (l) Immunoblot of SLC1A3 in indicated cell lines with b-actin loading control. (m) SLC1A2 and SLC1A3 mRNA expression data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) (log transformed) in KP PDAC cell lines and a glioma cell line (KNS-42). (n) Relative abundance of indicated metabolites in the culture media of indicated MIA PaCa-2 cells grown under indicated conditions for 24 hours in the presence of pyruvate (100 μM). c, d, e, f, g, i, k, n Bars represent mean ± s.d. b, j, boxes represent the median, first, and third quartiles; whiskers represent the minima and maxima. c, d, e, f, g, i, k, n, n = 3; b, n = 10; j, n = 5; k, n = 4. All replicates are biologically independent. Statistical significance determined by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Macropinocytosis enables proliferation of KRAS-mutant cells under conditions where aspartate is limited.

(a) Fold change in cell number (log2) of HeLa (left) or BxPC-3 tet-KRASV12 (right) cells cultured under indicated concentrations of oxygen for 5-6 days in the presence or absence of 1% BSA. BxPC-3 tet-KRASV12 cells were cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline (0.1μ/mL) to activate KRASV12 expression. (b) Immunoblot analysis of several members of the ETC complex in parental MIA PaCa-2 cells or Rho(0) counterparts. ACTB was used as a loading control. (c) Representative bright-field micrographs of HY15549 cells cultured for 5 days in media with or without 2% BSA. Where indicated, cells were treated with bafilomycin A1 (BafA1, 10 nM), ferric ammonium citrate (FAC, 0.1 μg/mL) and complex III inhibitor antimycin A (Anti. A, 100 nM). Scale bar = 50 μm. (d) Immunoblot analysis of GOT1 and GOT2 in GOT1/2- double knockout BxPC-3 tet-KRASV12 cells compared to parental controls. ACTB was used as a loading control. (e) Fold change in cell number (log2) of GOT1/2- double knockout BxPC-3 tet-KRASV12 cells cultured in the indicated media conditions for 7 days in the presence or absence of doxycycline (0.1 μg/mL) (top). Representative bright-field micrographs of GOT1/2- double knockout BxPC-3 tet-KRASV12 cells in media supplemented with 1% BSA in the presence and absence of doxycycline (0.1 μg/mL) (bottom). a, e, Bars represent mean ± s.d. a, e, n = 3 biologically independent samples. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Hypoxia-induced macropinocytosis depends on oncogenic KRAS in PDACs.

(a) Immunoblot analysis of FLAG and T7, showing inducible expression of stably transduced FLAG-tagged KRASG12V BxPC-3 cells and T7-tagged KRASG12V HeLa cells after addition of doxycycline (1 μg/mL for 2 days). ACTB or vinculin were used as a loading control. (b-e) Representative images (b, d) and quantification (c, e) of DQ-BSA fluorescence (green) in PANC-1 (b, c) and MIA PaCa-2 (d, e) cells under normoxia (21% O2) and hypoxia (0.5% O2). Nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. In c, e, data are presented relative to normoxia. c, e, Bars represent mean ± s.e.m. At least 500 (c, d) cells were quantified in each biological replicate (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. HIF1A stabilization stimulates macropinocytosis in PDAC cells and tumors.

(a) Immunoblot analysis indicated proteins in the indicated sgRNA-transduced PANC-1 cells treated with FG-4592 as shown. Vinculin is a loading control. (b, c) Representative images (b) and quantification (c) of TMR-dextran (red) uptake in control or sgHIF1A- or sgARNT-transduced PANC-1 cells cultured under indicated conditions. Nuclei are blue. Scale bar, 10 μm. In c, data are values normalized to control normoxic cells. (d) Relative mRNA levels of the HIF1A-target lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) in the indicated MIA PaCa-2 cell lines expressing the indicated vectors and treated with the prolyl-hydroxylase (PHD)-inhibitor FG-4592 (100 μM, 72 hrs) as shown. (e, f) Representative images (e) and quantification (f) of TMR-dextran (red) uptake in PANC-1 cells expressing indicated constructs cultured under indicated conditions. Nuclei are blue. Scale bar, 10 μm. In f, data are normalized to values for control normoxic cells. (g) Immunoblot analysis of HIF1A in MIA PaCa-2 and BxPC-3 cells treated with 0, 100, and 500 μM of the prolyl-hydroxylase inhibitor DMOG under normoxia (21% O2). Tubulin was used as a loading control. (h) Representative images of TMR-dextran (red) uptake in MIA PaCa-2 cells in the absence or presence of DMOG (500 μM) under normoxia (21% O2). Nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. (i) Quantification of macropinocytic uptake in MIA PaCa-2, PANC-1 and BxPC-3 cells treated in the absence or presence of DMOG (500 μM) under normoxia (21% O2). Data are presented relative to values obtained for untreated cells. (j) Representative images of TMR-dextran (red) uptake from sections of xenograft tumors arising from MIA PaCa-2 cells transduced with sgRNAs targeting HIF1A or ARNT with tumor cells immunostained with anti-CK8 (green), and pimonidazole detected with anti-pimonidazole (purple). Nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 50 μm, inset = 10 μm c, d, f, i, Bars represent mean ± s.e.m. d, n = 3 independent, biological replicates. At least 500 (c, f, i) cells were quantified in each biological replicate (n = 3). Statistical significance for all experiments was determined by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. Bicarbonate generation by CA9 mediates the effect of HIF1A on PDAC macropinocytosis under hypoxia.

(a) Representative images of CA9 (red) from sections of indicated tumor xenografts with +CK8 tumor cells (green), and hypoxic areas (purple). Nuclei are blue. Scale bar = 10 uM. (b) Immunofluorescence of CA9 relative to CK8 in sections of MIA PaCa-2 xenograft tumors. Data are normalized to values from CK8 +/pimo-areas. (c) Immunoblot analysis of CA9 in MIA PaCa-2 cells grown under hypoxia (0.5% O2) for the indicated times (hours). (d) Immunoblot analysis of indicated proteins in the indicated cell lines expressing indicated constructs. (e) Immunoblot analysis of CA9 in the indicated cell lines transduced with the indicated sgRNAs. (f, g) Representative images (f) and quantification (g) of TMR-dextran (red) uptake in PANC-1 cells transduced with indicated constructs and cultured under the indicated conditions. Nuclei are blue. Scale bar, 10 μm. In g, data are normalized to values from normoxic control cells. (h) Immunoblot analysis of CA9 in indicated cells transduced with indicated vectors. (i) Representative images of TMR-dextran (red) uptake in indicated PANC-1 cells cultured under indicated conditions. Nuclei are blue. Scale bar = 10uM. (j) Quantification of TMR-dextran uptake in indicated PANC-1 cells under indicated conditions. Data are normalized to values from control cells. (k) Quantification of TMR-dextran uptake in the indicated cell lines transfected with indicated constructs and cultured under indicated conditions. Data are normalized to values from control normoxic cells. (l) Quantification of TMR-dextran uptake in MIA PaCa-2 cells treated with soluble adenylate cyclase inhibitor KH7 under indicated conditions. Data normalized to values obtained from control normoxic cells. (m) Quantification of TMR-dextran uptake in MIA PaCa-2 cells treated with the PKA inhibitor H89 (15 μM) as shown under indicated conditions. Data are normalized to values obtained for control normoxic cells. b, g, j, k, l, m, Bars represent mean ± s.e.m. At least 300 (b) and 500 (g, j, k, l, m) cells were quantified in each biological replicate (n = 3). Vinculin is a loading control in all immunoblots shown. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed unpaired t-test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements