Abstract

Streptococcus suis capsular type 2 is an important etiological agent of swine meningitis, and it is also a zoonotic agent. Since mononuclear phagocytes have been suggested to play a central role in the pathogenesis of meningitis, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the capacity of whole killed S. suis type 2 organisms to induce the release of the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) by murine macrophages. Induction of cytokines was evaluated in the presence or absence of phorbol ester (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate [PMA]) costimulation. Results showed that S. suis type 2 stimulated the production of both cytokines in a concentration- and time-dependent fashion. Although large doses of bacteria were required for maximal cytokine release, titers were similar to those obtained with the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) positive control. An increase in cytokine release was observed with both S. suis and LPS with PMA costimulation. Experiments with cytochalasin-treated macrophages showed that the stimulation of cytokine production was phagocytosis independent. When macrophages were stimulated with an unencapsulated mutant, an increase in TNF production was observed, but the absence of the capsule had no effect on IL-6 production. In fact, whereas purified capsular polysaccharide of S. suis failed to induce cytokine release, purified S. suis cell wall induced both TNF and, to a lesser extent, IL-6. IL-6 secretion probably requires some distinct stimuli which differ from those of TNF. Finally, the S. suis putative virulence factors suilysin and extracellular protein EF showed no cytokine-stimulating activity. The ability of S. suis to trigger macrophages to produce proinflammatory cytokines may have an important role in the initiation and development of meningitis caused by this microorganism.

Streptococcus suis is an important pathogen which has been associated with a wide variety of infections in swine, such as meningitis, septicemia, arthritis, and pneumonia (22). This organism has also been isolated from humans with meningitis or endocarditis (3, 49). To date, 35 different capsular types of S. suis have been described. S. suis capsular type 2 is considered to be the most virulent as well as the most prevalent capsular type in diseased pigs (21). The clinical presentation of S. suis infection may vary from asymptomatic bacteremia to a fulminant systemic disease resembling the clinical syndrome of gram-negative sepsis. Meningitis is the most striking feature, and the most common histopathological characteristics are the presence of fibrin, edema, and cellular infiltrates of the meninges and choroid plexus (9, 22). The pathogenesis of S. suis infections is still unclear. S. suis is transmitted via the respiratory route and remains localized in the palatine tonsils. From that site, the bacteria may become septicemic and invade the meninges and other tissues, possibly in close association with monocytes/macrophages. Once in the central nervous system, these bacteria induce an acute inflammatory exudate which increases the volume of the cerebrospinal fluid, leading to an increased intracranial pressure (22, 60).

It is now recognized that several inflammatory and infectious diseases are associated with the overproduction of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and IL-6. These cytokines are believed to mediate reactions associated with clinical deterioration, multiorgan system failure, and death during septic shock (6). In addition, they have been implicated in bacterial meningeal inflammation (like group B streptococcus [GBS] and S. pneumoniae meningitis) by alteration of the cerebrospinal fluid dynamics, brain metabolism, and cerebral blood flow (54). The cell walls of these gram-positive microorganisms have been postulated as being the major modulator of the inflammatory response (51, 53). Despite the fact that mononuclear phagocytes have been implicated in playing a central role in the pathogenesis of meningitis (22, 60), the interactions of S. suis type 2 with phagocytic cells and the possible induction of proinflammatory cytokines have not yet been studied.

Virulence factors of S. suis type 2 are not well characterized. Different bacterial structures or products, such as the capsule polysaccharide (CPS) as well as cell wall-associated (muraminidase-released protein, specific adhesins, etc.) and extracellular (extracellular factor [EF] and a hemolysin [suilysin]) proteins, have been suggested as being involved in the pathogenesis of the infection (22, 47). The CPS is the only one of these factors that has so far been shown to be critical to virulence. In a recent work, isogenic acapsular mutants of a virulent S. suis type 2 strain were shown to be avirulent for both mice and piglets and were cleared from circulation rapidly (7). However, it is not known whether the capsule, as well as other bacterial components or virulence factors, contributes to the host inflammatory response occurring during S. suis infection.

Since the murine model of infection has been widely used to evaluate the virulence of S. suis strains (4), our objectives were to evaluate the capacity of whole killed S. suis type 2 organisms to induce the release of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 by murine macrophages and to determine the relative contributions of the cell wall, the CPS, and the purified extracellular proteins EF and suilsin to cytokine production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Cell culture media, fetal bovine serum, penicillin G, and streptomycin were purchased from Gibco (Burlington, Vt.); 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) was obtained from Bio-Rad (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli O127:B8, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), cytochalasin C (CyC) from Metarrhizium anisopliae, polymyxin B sulfate (PmB), MTT tetrazolium salt (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; thiazolyl blue), actinomycin D from Streptomyces sp., and latex beads (polystyrene; particle diameter, 1.07 μm) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario, Canada).

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The S. suis capsular type 2 virulent strain 31533, originally isolated from a pig with meningitis, was used as the reference strain in this study (25). The virulent, encapsulated S. suis wild-type strain S735 was also studied, together with its avirulent, unencapsulated isogenic transposon mutant, strain 2A (7). S. suis type 2 strain 6860 (EF+), used for EF purification, was kindly provided by U. Vecht (DLO Institute for Animal Sciences and Health, Lelystad, The Netherlands). Bacteria were maintained as stock cultures in Todd-Hewitt broth (THB; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) containing 50% glycerol at −80°C. The THB was supplemented with tetracycline (10 μg/ml; Sigma) for growing mutant strain 2A (7). Bacteria were grown overnight on bovine blood agar plates at 37°C, and isolated colonies were used as inocula for THB; these cultures were incubated for 18 h at 37°C. Working cultures for macrophage stimulation were made by inoculating 10-ml volumes of these cultures into 200-ml volumes of THB and incubating the inocula at 37°C with agitation until they reached the mid-log phase (6 h of incubation; final optical densities at 540 nm, 0.4 to 0.5). Bacteria were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, and diluted to approximately 2 × 109 CFU/ml in PBS. An accurate determination of the CFU per milliliter in the final suspension was made by plating it on THB agar.

Preparation of killed bacteria.

Bacteria were heat killed by incubating the organisms at 60°C for 45 min (the minimal experimental condition required for S. suis killing). For some experiments, bacteria were also treated at 100°C for 5 min. The killed cultures were subcultured on blood agar plates at 37°C for 48 h to prove that no viable organisms remained. Killed bacterial preparations were stored at 4°C and resuspended in cell culture medium just before stimulation assays were performed.

Purified bacterial components.

The procedure used for purification of S. suis cell wall, not previously reported, was adapted from those of Tuomanen et al. (51) and Heumann et al. (20). The unencapsulated strain 2A was grown in 1 liter of THB for 12 h at 37°C with agitation to a cell concentration of ∼2 × 108 CFU/ml. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation (12,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C), washed in saline, and resuspended in 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; 200 ml). This suspension was submerged in a boiling-water bath for 30 min. The denatured cells were quickly chilled on ice and disintegrated by the use of ultrasound (Sonics & Materials, Danbury, Conn.) for five 8-min pulses (80% duty cycle). The suspension was centrifuged (3,000 × g, 5 min) to remove unbroken cells, and the supernatant was centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 30 min at room temperature (RT) to sediment out the cell wall material. The pellet was resuspended in 20 ml of distilled water and subjected to a second ultrasound cycle (five 8-min pulses) to ensure complete cell disruption. This crude cell wall material was washed six times by centrifugation (30,000 × g, 30 min, RT) in distilled water, resuspended in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 1 mM MgCl2, and subsequently treated at 37°C with pancreatic DNase I (Sigma; 50 μg/ml) plus RNase (Sigma; 100 μg/ml) for 2 h and then with trypsin (Gibco; 100 μg/ml) plus 10 mM CaCl2 for 12 h. Cell wall material was sedimented by centrifugation (30,000 × g, 30 min, RT) and resuspended in 5 ml of 2% SDS at 100°C in a water bath for 30 min. The detergent was removed by 10 cycles of washing, first in a 1 M NaCl solution and then in distilled water, and the purified cell wall material was lyophilized, weighed, and stored in the dry state at RT. Purified CPS of type 2 S. suis strain S735 was prepared as previously described (42). Purified suilysin from S. suis type 2 strain P1/7 was kindly provided by T. Jacobs (Intervet International, Boxmeer, The Netherlands). The suilysin was reactivated by addition of 0.1% 2-ME (23) to the culture medium during macrophage stimulation assays. The EF was purified from an 18-h culture supernatant of type 2 S. suis strain 6860 applied to a Carbolink gel affinity column (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) coated with a rabbit monospecific polyclonal anti-EF antibody. Purified material was tested by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and silver nitrate staining.

Cell lines and cell culture.

The J774A1 murine (BALB/c) macrophage-like cell line (ATCC TIB 67) was maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 1.5 g of bicarbonate/ml. The P388D1 murine (DBA/2) macrophage-like cell line (ATCC TIB 63) was maintained in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium. The L929 murine fibroblast cell line (ATCC CCL-1) was maintained in Eagle’s minimal essential medium. The 7TD1 C57BL/6 mouse hybridoma cell line (IL-6 dependent; ATCC CRL-1851) was maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 50 mM 2-ME and 10% IMR-90 (ATCC CCL-186)-conditioned medium (as a source for IL-6). All cell media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin G (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and cells were grown at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Stimulation of macrophages.

For macrophage stimulation assays, cells of 48-h cultures of J774A1 or P388D1 were scraped from flasks, washed once in culture medium, and then resuspended in culture medium at a density of 4 × 106/ml. One-milliliter volumes of this suspension were distributed into polypropylene tubes (Sarstedt, Montreal, Québec, Canada), and 1 ml of killed S. suis strains or purified cell wall, CPS, EF, or suilysin was added to each in appropriate dilutions made in culture medium. In some experiments, macrophages were also costimulated with PMA (20 ng/ml). Experiments comparing cytokine production in response to the S. suis wild type and to mutant strains were always run concurrently. Macrophages stimulated with LPS (50 ng/ml) served as positive controls. Macrophages with medium alone served as controls for spontaneous cytokine release. In some experiments, macrophages were pretreated with CyC (2 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 to block phagocytosis and then stimulated with heat-killed bacteria (109 CFU/ml) and further incubated in the presence of CyC. As a control for nonspecific cytokine release, macrophages were treated with latex beads (109/ml) in the presence or absence of CyC. All cytokine induction mixtures were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. At different time intervals (see Results), culture supernatants were harvested from individual tubes. The supernatants were aliquoted and kept frozen at −20°C until TNF and IL-6 determinations were performed.

TNF-α bioassay.

TNF activity in culture supernatants was measured by the L929 cytotoxicity assay, as described elsewhere (12), with minor modifications. Briefly, 5 × 105 L929 cells were incubated overnight in each well of 96-well microtiter plates, the culture medium was then removed, and culture supernatant samples were added in twofold serial dilutions. A known concentration of murine recombinant TNF-α (mrTNF-α; Sigma) was used as a standard. Actinomycin D (5 μg/ml) was added immediately after the addition of samples or standard. The cells were further incubated for 18 h at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Supernatants were then removed, and cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet in 25% ethanol. After homogenization of stained cells with 33% acetic acid, the optical density was read in a microplate reader (UVmax; Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, Calif.) at 595 nm. An mrTNF-α standard curve was included in each assay. All analyses were performed at least in triplicate, and TNF concentrations in samples were calculated by comparison to the standard curve. The specificity of the test was controlled by neutralization of TNF activity with a polyclonal anti-mouse TNF-α antibody (Biosource International, Menlo Park, Calif.). In all cases, addition of specific antibody to macrophage supernatants reduced TNF activity by more than 90%.

IL-6 bioassay.

IL-6 activity in culture supernatants was determined by a proliferation assay with the IL-6-dependent 7TD1 mouse B-cell hybridoma cell line (31), with some modifications. Briefly, cells from a 48-h 7TD1 culture were washed twice and resuspended in IL-6-free culture medium at a density of 6 × 104/ml. Fifty-microliter volumes of this cell suspension were added to 50-μl volumes of twofold serial dilutions of macrophage supernatants in microtiter plates. After 72 h of incubation at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, the number of cells was evaluated by a colorimetric method. Twenty microliters of MTT (5 mg/ml in PBS) was added per well, and the plates were incubated as above for 5 h. MTT precipitate in each well was then solubilized overnight with 100 μl of 10% SDS. After homogenization, the optical density was read in a microplate reader (UVmax; Molecular Devices) at 595 nm. Optical density values were corrected for background proliferation of 7TD1 cells. A standard curve for mrIL-6 (Gibco) was included in each assay. All analyses were performed at least in triplicate, and the IL-6 concentrations in samples were calculated by comparison to the standard curve. The specificity of the test was controlled by inhibition of cell proliferation after the addition of a neutralizing rat anti-mouse IL-6 monoclonal antibody (Biosource International). In all cases, addition of specific antibody to macrophage supernatants reduced IL-6-stimulated growth of the 7TD1 cell line by 99%.

ELISAs for cytokines.

TNF-α and IL-6 were also measured by using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Cytoscreen; Biosource International) in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. The lower limits of detection were 3 and 8 pg/ml for TNF-α and IL-6, respectively. All analyses were performed in triplicate.

Endotoxin contamination.

All solutions and bacterial preparations used in these experiments were tested for the presence of endotoxin by a Limulus amoebocyte lysate gel clot test (Pyrotell STV; Cape Cod, Falmouth, Mass.) with a sensitivity limit of 0.03 endotoxin units (EU)/ml. In addition, endotoxin contamination during stimulation of macrophages was controlled by performing parallel assays with PmB (10 μg/ml). The activity of the PmB was determined by measuring its ability to inhibit cytokine release in response to LPS (50 ng/ml) by 99% (P < 0.001). In contrast, treatment with PmB did not change the levels of cytokine release induced by S. suis (P > 0.1) (data not shown). Results from the Limulus amoebocyte lysate test confirmed the data from the PmB treatment protocol. Bacterial preparations contained less than 0.125 EU/ml, and the cell culture media and PMA solution each contained less than 0.03 EU/ml. Thus, endotoxin levels were determined to be always <0.025 ng/ml, below that (>0.1 ng) recognized as causing macrophage activation (28).

Cytotoxicity test.

The cytotoxic effects of bacteria and bacterial products on macrophages were determined by the colorimetric MTT (tetrazolium) assay (31), with some modifications. At 24- and 48-h interval points, 400-μl volumes of a stock MTT solution (5 mg/ml in PBS) were added to the different cytokine induction mixtures (prepared as described above); the tubes were incubated for 5 h. MTT precipitate was then solubilized overnight with 2 ml of 10% SDS. After homogenization, the optical density at 595 nm was read and the percentage of cytotoxicity was calculated. The different concentrations of bacteria or purified components tested did not have toxic effects on mammalian cells under the experimental conditions used in the present study (data not shown).

Statistical analysis.

Each test of macrophage stimulation was done at least in triplicate. Results were derived from linear-regression calculations and expressed in units of TNF or IL-6 per milliliter by comparing the reciprocals of the dilutions of TNF- or IL-6-containing test samples with the 50% endpoints of the standard curves in the bioassay systems. TNF and IL-6 values are expressed as means ± standard deviations of values from independent experiments. Differences were analyzed for significance by using Student’s unpaired t test (two-tailed P value). A P value of >0.05 was considered not significant, a P value of <0.05 was considered not quite significant, a P value of <0.01 was considered significant, and a P value of <0.001 was considered extremely significant.

RESULTS

Kinetics of TNF-α and IL-6 release by macrophages, triggered by whole S. suis organisms.

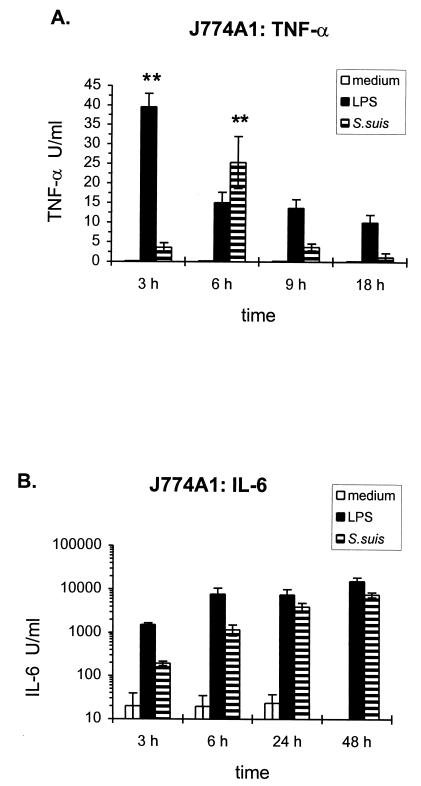

The induction of TNF and IL-6 production by the mouse macrophage cell lines J774A1 and P388D1 was evaluated after stimulation with heat-killed (60°C for 45 min) S. suis type 2 strain 31533. Cell culture medium alone was used as a negative control, and purified E. coli LPS (50 ng/ml) was used as a positive control. With a 109-CFU/ml dose of bacteria, the induction of these cytokines was time dependent. The kinetics of cytokine release from J774A1 cells is shown in Fig. 1. TNF activity appearing in culture supernatants after stimulation with whole bacteria clearly peaked at 6 h of incubation (P = 0.001) and markedly decreased upon further incubation through 18 h. Maximum LPS induction of TNF was observed at 3 h (P = 0.001). In contrast, IL-6 secretion showed a progressive accumulation, with higher IL-6 production observed by 48 h with both whole-bacterium (P = 0.02) and LPS (P = 0.05) stimulation. IL-6 titers were higher than those measured for TNF in all cases. A similar kinetics of cytokine release was observed with P388D1 cells (data not shown). Hence, for subsequent experiments, 6-h supernatants were used to analyze TNF induction whereas supernatants were harvested 48 h after stimulation for measurements of IL-6 production.

FIG. 1.

Time course of production of TNF-α (A) and IL-6 (B) by J774A1 cells (2 × 106/ml) stimulated with heat-killed (60°C for 45 min) S. suis strain 31533 (109 CFU/ml). Culture supernatants were harvested at different time intervals and were assayed for TNF-α and IL-6 by bioassay. Cell culture medium was used as a negative control, and purified E. coli LPS (50 ng/ml) was employed as a positive control. Data were collected from at least three separate experiments performed in duplicate and are expressed as means ± standard deviations (in units per milliliter). ∗∗, P < 0.001 (versus the corresponding stimulus at each time interval).

P388D1 and J774A1 macrophages differ in cytokine release and effect of PMA costimulation.

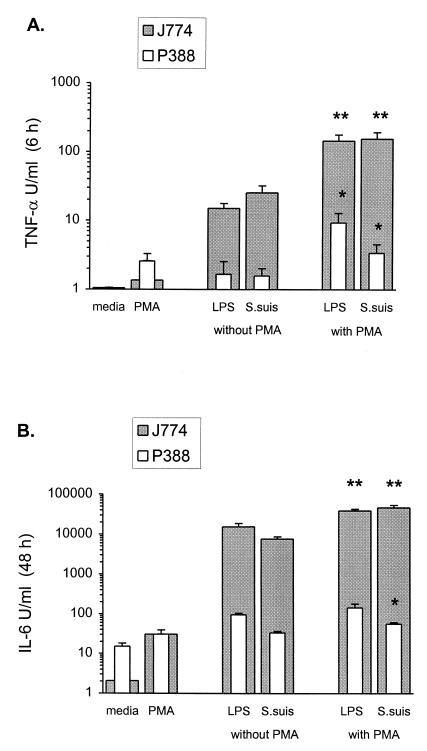

In general, stimulated J774A1 cells produced significantly higher levels of cytokines than P388D1 cells (Fig. 2). Interestingly, cytokine induction by S. suis with J774A1 cells was similar to that obtained with LPS at 50 ng/ml (P = 0.09 for TNF; P = 0.04 for IL-6), while S. suis was a less-potent inductor of IL-6 release by P388D1 cells (P < 0.01 with respect to LPS values), and both LPS and S. suis showed a weak TNF-stimulating activity in this cell line.

FIG. 2.

Effect of PMA costimulation on cytokine induction by S. suis with two macrophages cell lines, J774A1 and P388D1. J774A1 or P388D1 cells (2 × 106/ml) were stimulated with heat-killed (60°C for 45 min) S. suis strain 31533 (109 CFU/ml) in the presence or absence of PMA (20 ng/ml). TNF-α, at 6 h of incubation (A), and IL-6, at 48 h of incubation (B), were measured by bioassay titration of stimulated cell supernatants. Cytokine induction by S. suis was compared to that by purified E. coli LPS (50 ng/ml) under the same conditions. Cell culture medium and PMA alone were used as controls. Data were collected from at least three separate experiments performed in duplicate and are expressed as means + standard deviations (in units per milliliter). ∗∗, P < 0.001 (compared to the value in the absence of PMA and to the PMA control); ∗, P < 0.01 (compared to the value in the absence of PMA, but not quite significant with respect to the PMA control).

Since macrophage activation via protein kinase C (PKC) pathways is well documented (11), levels of cytokine induction by S. suis in the presence of PMA, a direct stimulator of PKC, were also compared (32). In the case of J774A1 cells, when macrophages were activated with PMA, the induction of both cytokines by S. suis, as with LPS, was significantly enhanced (P < 0.001). This effect was synergistic, since PMA alone was too weak as a cytokine inducer to account for this enhancement. However, with P388D1 cells, this enhanced stimulation was less significant (P < 0.01), and it was not quite significant with respect to PMA control (P > 0.02). Thus, a possible additive effect of PMA alone and stimuli alone could not be ruled out for this cell line (Fig. 2).

J774A1 is classified as one of the most mature macrophage-like cell lines, while P388D1 has an immature phenotype (33). This may account for the apparent differences in the levels of enhancement of cytokine production seen with these two cell lines. Hence, due to the obtainment of a higher-level cytokine response, J774A1 macrophages were used to analyze cytokine induction further.

Bacterial-concentration-dependent cytokine release.

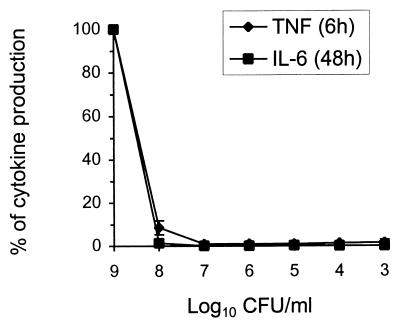

J774A1 macrophages were exposed to different concentrations of heat-killed (60°C for 45 min) S. suis type 2 strain 31533. A high bacterial concentration was needed for maximal TNF and IL-6 production. When the bacterial titer was decreased to 108 CFU/ml, cytokine release decreased considerably, and almost no cytokine production was observed at bacterial concentrations lower than 107 CFU/ml (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Effect of bacterial concentration on the production of TNF-α and IL-6. J774A1 cells (2 × 106/ml) were stimulated with different concentrations of heat-killed (60°C for 45 min) S. suis 31533 in the presence of PMA (20 ng/ml). TNF-α, at 6 h of incubation, and IL-6, at 48 h of incubation, were measured by bioassay titration of stimulated cell supernatants. Data were collected from at least three separate experiments performed in duplicate and are expressed as the percentage of cytokine production with respect to the maximal value (100%) obtained with 109 CFU/ml.

Role of bacterial uptake in cytokine release: effect of phagocytosis inhibition by cytochalasin.

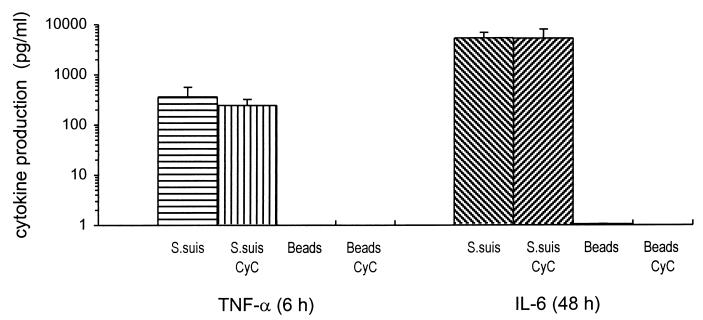

Since several studies had shown at least some uptake of S. suis by phagocytic cells (1), it was of interest to determine whether cytokine production was related to phagocytosis of bacteria. To address this question, experiments were performed in the presence of CyC (2 μg/ml), an inhibitor of microfilament-dependent uptake of particles by phagocytic cells. The cytochalasins have been used extensively for inhibition of phagocytosis of many bacteria and have no detectable effect on the attachment of bacteria or on cytokine induction (10, 36, 61). Results from ELISA titrations (performed because bioassay titration cannot be done with supernatants containing CyC) demonstrated that CyC had no effect on TNF or IL-6 production by J774A1 cells after S. suis stimulation (P = 0.3 and 0.9, respectively) (Fig. 4). To confirm that cytokine release was not caused by nonspecific phagocytosis of bacteria and consequent activation of macrophages, cells were also stimulated with 109 1.07-μm-diameter latex beads. These inert particles were chosen because of their similarity in size to S. suis organisms. No cytokine induction was demonstrated with latex beads in the presence or absence of CyC (Fig. 4). At the concentration used in this study, CyC was able to effectively block phagocytosis of bacteria without causing toxic effects on mammalian cells (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Effect of phagocytosis inhibition by CyC on cytokine production. CyC (2 μg/ml) was added during stimulation of J774A1 cells (2 × 106/ml), in parallel with controls without CyC. Cells were stimulated with 109 heat-killed (60°C for 45 min) S. suis 31533 cells or 109 latex beads/ml. TNF-α, at 6 h of incubation, and IL-6, at 48 h of incubation, were measured by ELISA titration of stimulated cell supernatants. Data were collected from at least three separate experiments performed in duplicate and are expressed as means + standard deviations (in picograms per milliliter).

Relative roles of bacterial components in cytokine production.

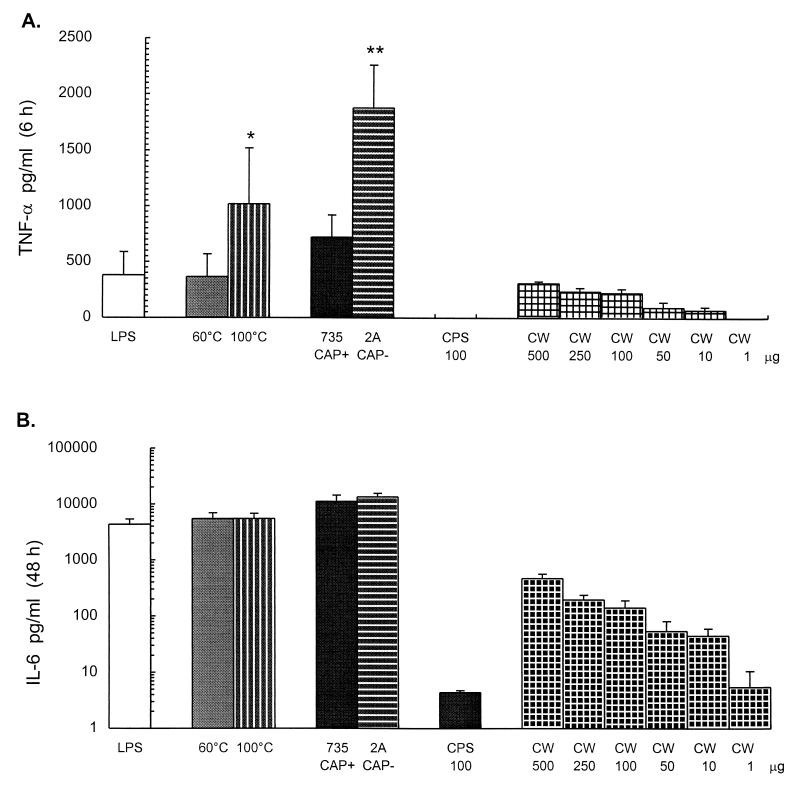

The relative contributions of proteins, CPS, and the S. suis cell wall to cytokine production were evaluated by using bacteria treated at 100°C for 5 min, an unencapsulated mutant, purified CPS, and purified cell wall material (Fig. 5). TNF and IL-6 concentrations were measured by ELISA and/or bioassay titration.

FIG. 5.

Relative roles of bacterial components in cytokine production. S. suis 31533 treated at 60°C for 45 min or at 100°C for 5 min, the encapsulated strain S735 and its corresponding unencapsulated mutant, strain 2A (109 heat-killed bacteria), the purified CPS (100 μg/ml), and the purified cell wall material were used for cytokine stimulation of J774A1 cells (2 × 106/ml). TNF-α, at 6 h of incubation (A), and IL-6, at 48 h of incubation (B), were measured by ELISA titration of stimulated cell supernatants. Purified E. coli LPS (50 ng/ml) served as a positive control. Data were collected from at least three separate experiments performed in duplicate and are expressed as means + standard deviations (in picograms per milliliter). ∗, P < 0.01 (compared to the value obtained with 60°C heat-killed bacteria); ∗∗, P < 0.001 (compared to the value obtained with encapsulated parent strain S735). 735 CAP+, encapsulated strain S735; 2A CAP−, unencapsulated strain 2A; CW, purified cell wall (different concentrations in micrograms per milliliter).

The level of cytokine released by S. suis type 2 strain 31533 treated at 100°C for 5 min was compared to that induced by the standard bacterial suspension (bacteria killed by heating at 60°C for 45 min, as used above). Results showed that the induction of TNF was increased after 100°C heat treatment of bacteria (P = 0.005) (Fig. 5A), possibly due to the exposition of newly denatured antigens. In contrast, no significant difference in IL-6 release from 100°C heat-killed and from 60°C heat-killed bacteria was observed (P = 0.9) (Fig. 5B). These results were also confirmed by bioassay titration (data not shown).

When the encapsulated strain S735 was compared to the unencapsulated isogenic mutant strain 2A with regard to the ability to induce cytokine secretion, the unencapsulated mutant was found to induce significantly more TNF than the encapsulated wild-type strain (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the induction of IL-6 was not influenced by the presence or absence of the capsule (P = 0.3) (Fig. 5B). These results were also confirmed by bioassay titration (data not shown).

To study the capacity of S. suis type 2 CPS to induce TNF and IL-6 release, different concentrations of purified CPS, ranging from 0.01 to 100 μg/ml, were tested. A concentration as high as 100 μg/ml did not induce significant levels of cytokine release compared to the negative control or whole bacteria (Fig. 5). This was in agreement with the finding that an unencapsulated mutant produced amounts of cytokines equal to or larger than those produced by the encapsulated parental strain.

Interestingly, when the purified cell wall material (ranging from 0.1 to 500 μg/ml) was evaluated for cytokine production, a threshold of 10 μg/ml was sufficient to initiate production of both cytokines. Maximum release was achieved at concentrations of about 100 μg/ml or higher. Cell wall material was roughly equivalent to whole bacteria for induction of TNF (P = 0.2) (Fig. 5A), whereas it was approximately 10 times less efficient than 109 bacterial equivalents for induction of IL-6 (Fig. 5B).

Induction of TNF-α and IL-6 by the secreted putative S. suis virulence factors.

When different concentrations of two secreted putative virulence factors of S. suis were tested, neither the purified EF factor (from 0.1 to 100 ng/ml) nor the purified hemolysin (from 0.01 to 100 ng/ml) stimulated the release of cytokines (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated for the first time that heat-killed S. suis stimulates mouse macrophages to release TNF-α and IL-6 in a dose- and time-dependent fashion, confirming recent reports which revealed that several pathogenic gram-positive cocci are powerful inducers of inflammatory cytokines (27, 40, 56). Time course studies indicated that TNF is released before IL-6 and that IL-6 levels are higher and persist longer than those of TNF. S. suis-induced TNF levels drop much faster than those described in the literature for other gram-positive bacteria (5, 8, 30). This seems to be a particular feature of S. suis, since similar results were observed with human monocytes (unpublished observations). TNF is known to stimulate IL-6 expression (13); however, TNF does not appear to directly induce IL-6, since an increase in TNF release after different bacterial treatments does not imply an increase in IL-6 levels (Fig. 5). These data indicate that S. suis is able to directly stimulate the release of both TNF and IL-6. This further suggests the existence of TNF-independent mechanisms leading to IL-6 production. Other reports had already established a lack of association between TNF and IL-6 production (19, 29). However, priming of monocytes by TNF may contribute to the increased production of IL-6 observed after incubation for more than 24 h (52, 57).

The kinetics of S. suis cytokine induction is similar to that of LPS from E. coli, as well as to that reported to occur during endotoxin fever (24). In addition, both S. suis and LPS are similarly affected by PMA costimulation, showing comparable increases in cytokine release. This effect is synergistic, since PMA alone hardly stimulates cytokine production, as has been previously shown with the same macrophage cell lines (29). PMA is an activator of PKC (32), and the PKC pathway is involved in the activation of many cell processes, such as immune responses, cell growth regulation, cell differentiation, and receptor expression (32, 34). Thus, S. suis stimulation of macrophage IL-6 and TNF production is responsive to activation of PKC, as evidenced by PMA potentiation of the S. suis cytokine response. This is a common feature with LPS-induced cytokines, as described herein and in previous works (28, 29, 39). Wightman and Raetz (59) postulated that LPS exerts its pleiotropic effects in part through activation of PKC. One common pathway of many gram-positive bacteria and LPS is interaction with the CD14 receptor, postulated by Pugin et al. (37) to be a pattern recognition receptor. In this regard, preliminary studies showed that S. suis-induced IL-6 release is inhibited by an anti-CD14 antibody. Further studies of the signaling mechanisms of S. suis cytokine induction are warranted.

Large doses of heat-killed S. suis are required for maximal cytokine release by J774A1 macrophages. However, the observed response was as potent as that achieved with 50 ng of E. coli LPS under the conditions used in this study. In vitro induction of TNF secretion in response to heat-killed pneumococci or staphylococci required stimulation of monocytes/macrophages by a threshold concentration of 106 bacteria, while maximal production was observed with more than 108 bacteria (44, 48). However, induction of an amount of inflammatory cytokines approximating that observed with LPS required a lower concentration of heat-killed pneumococci or GBS (5, 52, 53) than of S. suis. Although a large dose of bacteria is also required for maximal cytokine release, these data suggest that these pathogenic gram-positive bacteria have a higher potency than S. suis.

One of the major virulence factors of S. suis is the type 2 specific CPS (7). In an attempt to investigate the role of the capsule in cytokine release, an encapsulated and an unencapsulated type 2 S. suis strain were compared. The presence or absence of a capsule had no effect on IL-6 production, but the absence of a capsule resulted in increased TNF production, suggesting that antigens responsible for TNF release may be partially masked by the capsule. Furthermore, purified S. suis CPS failed to induce cytokine release. Several in vitro and in vivo studies with purified CPS or with unencapsulated mutants failed to demonstrate a major role for this bacterial component in cytokine induction by important pathogenic gram-positive cocci (35, 51–53). In addition, it has been reported that heat-killed unencapsulated GBS and S. pneumoniae strains induce higher levels of meningeal inflammation than their respective encapsulated parent strains, suggesting that the presence of capsular material masks the inflammatory activity of the underlying cell wall (27, 51). However, these findings do not imply that the S. suis capsule does not play an important role in the pathogenesis of the infection. Indeed, as demonstrated by Charland et al. (7) and Smith et al. (45), the capsule plays a critical role by protecting bacteria from in vivo clearance. Therefore, the capsule may not be necessary for induction of the release of inflammatory cytokines during S. suis infection, but it may contribute to the progression of disease by allowing the organism to evade host defense mechanisms such as phagocytosis. In this regard, lethal S. pneumoniae meningitis could be induced despite the lack of CPS, but the presence of the pneumococcal capsule is associated with a higher and more sustained bacterial density in cerebrospinal fluid (51).

The fact that heat-killed washed organisms were able to induce cytokine production indicates that relatively heat-stable cell-associated components are probably responsible for most of the cytokine stimulation observed. Furthermore, high-temperature (100°C) treatment of bacteria did not decrease cytokine release, indicating a probable limited role of proteins. Nevertheless, some protein-mediated effect cannot be completely ruled out, particularly with the 60°C treatment of bacteria. Heat-resistant potential candidates may include cell wall components, such as peptidoglycan or lipoteichoic acid, which have been demonstrated to be potent cytokine inductors for various gram-positive cocci (20, 48). It was postulated that encapsulated bacteria cause inflammation by exposing the underlying cell wall or by secreting cell wall material during growth (51). In fact, purified S. suis cell wall material was able to induce a TNF response similar to that obtained with whole bacteria. It could also induce, although to a lesser extent, IL-6 release. This result suggests that bacterial components other than those in the cell wall also contribute to IL-6 induction by S. suis and confirms the differences observed with the unencapsulated mutant as described above. Further studies are needed to determine the exact nature of the S. suis components responsible for cytokine release.

Since previous studies of the pathogenesis of S. suis infections suggested that bacteria could be phagocytosed, even in the presence of a capsule (1, 60), the possibility that the release of cytokines is a consequence of phagocytosis could not be ruled out. In fact, the dependence of TNF induction by GBS on phagocytosis has already been reported (16). Results obtained in the presence of CyC demonstrate that phagocytosis does not have an effect on TNF or IL-6 production by J774A1 cells after S. suis stimulation. In addition, nonspecific stimulation with latex beads did not induce any significant increase of cytokine release under conditions identical to those used for S. suis stimulation. We conclude that cytokine release by S. suis is not related to phagocytosis of this microorganism. This was also confirmed by a recent study showing that unlike GBS, well-encapsulated S. suis is in fact not phagocytosed (41). Using a similar approach, Simpson et al. (44) also obtained data suggesting that phagocytosis is not the major initiating factor for TNF synthesis in S. pneumoniae-stimulated macrophages. Recently, the importance of the attachment phase for cytokine induction has been shown with several bacterial species, including intracellular bacteria such as Legionella pneumophila and Listeria monocytogenes (10, 61). Thus, the initial attachment of bacteria to macrophages may be sufficient to generate a signal for cytokine induction, and such a signal may be mediated by interactions between bacterial ligands and macrophage receptors.

Since it has been shown that several microbial toxins can stimulate or modulate the inflammatory mediator cascade (26), two soluble proteins of S. suis, suilysin and EF, described as possible virulence factors, were analyzed (18, 55). However, we failed to demonstrate a role for these factors in cytokine induction by murine macrophages in vitro. This is in agreement with recent reports which indicate that S. suis type 2 strains deficient in the production of these proteins remain virulent (17, 46). It has also been shown that a pneumolysin-deficient strain of S. pneumoniae caused meningeal inflammation in rabbits indistinguishable from that induced by the parent strain (15). Similarly, streptolysin O from S. pyogenes induced neither neutrophil influx nor significant cytokine elevations in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (43). These two hemolysins, like suilysin, belong to the family of thiol-activated toxins (2). However, the role of suilysin, as well as that of EF, in in vivo inflammation remains to be elucidated.

Elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines have been correlated with disease severity and mortality in experimental animal models, and neutralization of these cytokines improves the survival rates of animals infected with pathogenic bacteria such as pneumococci or Haemophilus influenzae type b (38, 40). The observed cytokine-inducing activity of S. suis, most remarkably the higher-level IL-6 response, may have significant biological relevance, since it has been demonstrated that IL-6 can be generated in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid during invasive meningeal infections (50, 58). Furthermore, IL-6 was recently postulated to be a marker for acute bacterial infection in swine (14).

In conclusion, our findings suggest that S. suis type 2 may trigger macrophages to produce proinflammatory cytokines and may therefore be implicated in the initiation and development of meningitis caused by this microorganism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Sonia Lacouture for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Monique Doré for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) grant no. 0680154280 and by Fonds pour la Formation des Chercheurs et l’Aide à la Recherche du Québec (FCAR) grant no. NC-1037. M.S. holds a graduate scholarship from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander T. Proceedings of the Allen D. Leman Swine Conference. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 1995. Streptococcus suis: pathogenesis and host response; pp. 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alouf J E, Geoffroy C. The family of the antigenically-related cholesterol-binding (“sulphydryl-activated”) cytolytic toxins. In: Alouf J E, editor. Sourcebook of bacterial protein toxins. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 147–186. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arends J P, Zanen H C. Meningitis caused by Streptococcus suis in humans. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:131–137. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaudoin M, Higgins R, Harel J, Gottschalk M. Studies on a murine model for evaluation of virulence of Streptococcus suis capsular type 2 isolates. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;78:111–116. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90011-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cauwels A, Wan E, Leismann M, Tuomanen E. Coexistence of CD14-dependent and independent pathways for stimulation of human monocytes by gram-positive bacteria. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3255–3260. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3255-3260.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerami A. Inflammatory cytokines. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1992;62:S3–S10. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(92)90035-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charland N, Harel J, Kobish M, Lacasse S, Gottschalk M. Streptococcus suis serotype 2 mutants deficient in capsular expression. Microbiology. 1998;144:325–332. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleveland M G, Gorham J D, Murphy T L, Tuomanen E, Murphy K M. Lipoteichoic acid preparations of gram-positive bacteria induce interleukin-12 through a CD14-dependent pathway. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1906–1912. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.1906-1912.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clifton-Hadley F A. Studies of Streptococcus suis type 2 infection in pigs. Ph.D. thesis. Cambridge, United Kingdom: University of Cambridge; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demuth A, Goebel W, Beuscher H U, Kuhn M. Differential regulation of cytokine and cytokine receptor mRNA expression upon infection of bone marrow-derived macrophages with Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3475–3483. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3475-3483.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan X D, Goldberg M, Bloom B R. Interferon-γ-induced transcriptional activation is mediated by protein kinase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5122–5125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flick D A, Gifford G E. Comparison of in vitro cell cytotoxic assays for tumor necrosis factor. J Immunol Methods. 1984;68:167–175. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fong Y, Tracey K J, Moldawer L L, Hesse D G, Manogue K B, Kenney J S, Lee A T, Kuo G C, Allison A C, Lowry S F, Cerami A. Antibodies to cachectin/tumor necrosis factor reduce interleukin 1β and interleukin 6 appearance during lethal bacteremia. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1627–1633. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.5.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fossum C, Wattrang E, Fuxler L, Jensen K T, Wallgren P. Evaluation of various cytokines (IL-6, IFN-α, IFN-γ, TNF-α) as markers for acute bacterial infection in swine—a possible role for serum interleukin-6. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;64:161–172. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(98)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedland I R, Paris M M, Hickey S, Shelton S, Olsen K, Paton J C, McCracken G H. The limited role of pneumolysin in the pathogenesis of pneumococcal meningitis. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:805–809. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.3.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodrum K J, Dierksheide J, Yoder B J. Tumor necrosis factor alpha acts as an autocrine second signal with gamma interferon to induce nitric oxide in group B streptococcus-treated macrophages. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3715–3717. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3715-3717.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottschalk M, Lebrun A, Wisselink H, Dubreuil J D, Smith H, Vecht U. Production of virulence-related proteins by Canadian strains of Streptococcus suis capsular type 2. Can J Vet Res. 1998;62:75–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottschalk M G, Lacouture S, Dubreuil J D. Characterization of Streptococcus suis capsular type 2 haemolysin. Microbiology. 1995;141:189–195. doi: 10.1099/00221287-141-1-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Havell E A, Sehgal P B. Tumor necrosis factor-independent IL-6 production during murine listeriosis. J Immunol. 1991;146:756–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heumann D, Barras C, Severin A, Glauser M P, Tomasz A. Gram-positive cell walls stimulate synthesis of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 by human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2715–2721. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2715-2721.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins R, Gottschalk M. Distribution of Streptococcus suis capsular types in 1997. Can Vet J. 1998;39:299–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins R, Gottschalk M. Streptococcal diseases. In: Straw B E, D’Allaire S, Mengeling W L, Taylor D J, editors. Diseases of swine. Ames: Iowa State University; 1999. pp. 563–570. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobs A A C, Loeffen P L W, van den Berg A J G, Storm P K. Identification, purification, and characterization of a thiol-activated hemolysin (suilysin) of Streptococcus suis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1742–1748. doi: 10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.b00034458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansky L, Vybiral S, Pospisilova D, Roth J, Dornand J, Zeisberger E, Kaminkova J. Production of systemic and hypothalamic cytokines during the early phase of endotoxin fever. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;62:55–61. doi: 10.1159/000126988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobisch M, Gottschalk M, Morvan P, Cariolet R, Bénévent G, Joly J P. Infection expérimentale de porcelets par Streptococcus suis, serovar 2. J Rech Porcine Fr. 1995;27:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 26.König W, Kasimir S, Hensler T, Scheffer J, König B, Hilger R, Brom J, Köller M. Release of inflammatory mediators by toxin stimulated immune system cells and platelets. Zentbl Bakteriol Suppl. 1992;23:385–394. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ling E W Y, Noya F J D, Ricard G, Beharry K, Mills E L, Aranda J V. Biochemical mediators of meningeal inflammatory response to group B Streptococcus in the newborn piglet model. Pediatr Res. 1995;38:981–987. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199512000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin C A, Dorf M E. Differential regulation of interleukin-6, macrophage inflammatory protein-1, and JE/MCP-1 cytokine expression in macrophage cell lines. Cell Immunol. 1991;135:245–258. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90269-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin C A, Dorf M E. Interleukin-6 production by murine macrophage cell lines P388D1 and J774A.1: stimulation requirements and kinetics. Cell Immunol. 1990;128:555–568. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(90)90048-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattsson E, Rollof J, Verhoef J, Van Dijk H, Fleer A. Serum-induced potentiation of tumor necrosis factor alpha production by human monocytes in response to staphylococcal peptidoglycan: involvement of different serum factors. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3837–3843. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3837-3843.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newton A C. Protein kinase C: structure, function, and regulation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28495–28498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nibbering P H, Van Furth R. Quantitative immunocytochemical characterization of four murine macrophage-like cell lines. Immunobiology. 1988;176:432–439. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(88)80024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase C and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. FASEB J. 1995;9:484–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orman K L, Shenep J L, English B K. Pneumococci stimulate the production of the inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitric oxide by murine macrophages. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1649–1657. doi: 10.1086/314526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Painter R G, Whisenand J, McIntosh A T. Effects of cytochalasin B on actin and myosin association with particle binding sites in mouse macrophages: implications with regard to the mechanism of action of the cytochalasins. J Cell Biol. 1981;91:373–384. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.2.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pugin J, Heumann D, Tomasz A, Kravchenko V V, Akamatsu Y, Nishijima M, Glauser M P, Tobias P S, Ulevitch R J. CD14 is a pattern recognition receptor. Immunity. 1994;1:509–516. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramilo O, Saéz-Llorens X, Mertsola J, Jafari H, Olsen K D, Hansen E J, Yoshinaga M, Ohkawara S, Nariuchi H, McCracken G H., Jr Tumor necrosis factor α/cachectin and interleukin 1β initiate meningeal inflammation. J Exp Med. 1990;172:497–507. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.2.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts F A, Richardson G J, Michalek S M. Effects of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharides on mononuclear phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3248–3254. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3248-3254.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saukkonen K, Sande S, Cioffe C, Wolpe S, Sherry B, Cerami A, Tuomanen E. The role of cytokines in the generation of inflammation and tissue damage in experimental gram-positive meningitis. J Exp Med. 1990;171:439–448. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Segura M A, Cléroux P, Gottschalk M. Streptococcus suis and group B Streptococcus differ in their interactions with murine macrophages. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998;21:189–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sepulveda E M D, Altman E, Kobisch M, Dallaire S, Gottschalk M. Detection of antibodies against Streptococcus suis capsular type 2 using a purified capsular polysaccharide antigen-based indirect ELISA. Vet Microbiol. 1996;52:113–125. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(96)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shanley T P, Schrier D, Kapur V, Kehoe M, Musser J M, Ward P A. Streptococcal cysteine protease augments lung injury induced by products of group A streptococci. Infect Immun. 1996;64:870–877. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.870-877.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simpson S Q, Singh R, Bice D E. Heat-killed pneumococci and pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides stimulate tumor necrosis factor-α production by murine macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10:284–289. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.3.8117447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith H E, Damman M, van der Velde J, Wagenaar F, Wisselink H J, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Smits M A. Identification and characterization of the cps locus of Streptococcus suis serotype 2: the capsule protects against phagocytosis and is an important virulence factor. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1750–1756. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1750-1756.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith H E, Vecht U, Wisselink H J, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Biermann Y, Smits M A. Mutants of Streptococcus suis types 1 and 2 impaired in expression of muramidase-released protein and extracellular protein induce disease in newborn germfree pigs. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4409–4412. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4409-4412.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Staats J J, Feder I, Okwumabua O, Chengappa M M. Streptococcus suis—past and present. Vet Res Commun. 1997;21:381–407. doi: 10.1023/a:1005870317757. . (Review.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Timmerman C P, Mattsson E, Martinez-Martinez L, De Graaf L, Van Strijp J A G, Verbrugh H A, Verhoef J, Fleer A. Induction of release of tumor necrosis factor from human monocytes by staphylococci and staphylococcal peptidoglycans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4167–4172. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4167-4172.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trottier S, Higgins R, Brochu G, Gottschalk M. A case of human endocarditis due to Streptococcus suis in North America. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:1251–1252. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.6.1251. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tunkel A R, Scheld W M. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:118–136. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tuomanen E, Tomasz A, Hengstler B, Zak O. The relative role of bacterial cell wall and capsule in the induction of inflammation in pneumococcal meningitis. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:535–540. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vallejo J G, Baker C J, Edwards M S. Interleukin-6 production by human neonatal monocytes stimulated by type III group B streptococci. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:332–337. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vallejo J G, Baker C J, Edwards M S. Roles of the bacterial cell wall and capsule in induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha by type III group B streptococci. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5042–5046. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5042-5046.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Furth A M, Roord J J, van Furth R. Roles of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in pathophysiology of bacterial meningitis and effect of adjunctive therapy. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4883–4890. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.4883-4890.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vecht U, Wisselink H J, Jellema M L, Smith H E. Identification of two proteins associated with virulence of Streptococcus suis type 2. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3156–3162. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3156-3162.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verhoef J, Mattsson E. The role of cytokines in gram-positive bacterial shock. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:136–140. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88902-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.von Hunolstein C, Totolian A, Alfarone G, Mancuso G, Cusumano V, Teti G, Orefici G. Soluble antigens from group B streptococci induce cytokine production in human blood cultures. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4017–4021. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4017-4021.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waage A, Brandtzaeg P, Halstensen A, Kierulf P, Espevik T. The complex pattern of cytokines in serum from patients with meningococcal septic shock. Association between interleukin 6, interleukin 1, and fatal outcome. J Exp Med. 1989;169:333–338. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wightman P D, Raetz C R H. The activation of protein kinase C by biologically active lipid moieties of lipopolysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:10048–10052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams A E, Blakemore W F. Pathogenesis of meningitis caused by Streptococcus suis type 2. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:474–481. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.2.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamamoto Y, Okubo S, Klein T W, Onozaki K, Saito T, Friedman H. Binding of Legionella pneumophila to macrophages increases cellular cytokine mRNA. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3947–3956. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3947-3956.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]