Abstract

Background

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and its far-reaching impact, the prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms is increasing significantly in China. Yet access to reliable and effective psychological treatment is still limited during the pandemic. The widespread adoption of mobile technologies may provide a new way to address this gap. In this research we will develop an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) based intervention delivered by mobile application and will test its usability, efficacy, and mechanism of its effects in relieving PTSD symptoms.

Methods

A total of 147 Chinese participants with a diagnosis of PTSD according to the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-5) will be randomly assigned to an intervention group (app-delivered ACT), an active comparison group (app-delivered mindfulness), or a waitlist group. Participants in the intervention group or comparison group will use their respective apps for one month. Online self-report questionnaires will be used to assess the primary outcome of PTSD symptoms and the secondary outcomes symptoms of depression, symptoms of anxiety, and posttraumatic growth. The potential mediating variable to be tested is psychological flexibility and its components. These assessments will be conducted at baseline, at five times during treatment, at the end of treatment, and at 1- and 3-month follow-ups.

Discussion

As far as we know, this study is the first randomized controlled trial to investigate the usability, efficacy, and mechanism of an app-delivered ACT intervention for PTSD. Furthermore, the research will assess the effect of treatment in reducing dropout rates, explore effective therapeutic components, and investigate mechanisms of symptom change, which will be valuable in improving the efficacy and usability of PTSD interventions.

Trial registration: ChiCTR2200058408.

Keywords: COVID-19, Posttraumatic stress disorder, Randomized controlled trial, ACT, China, Mobile app-delivered intervention

Abbreviations: ACT, Acceptance Commitment Therapy; COVID-19, Corona Virus Disease 2019

Highlights

-

•

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a promising therapy that uses acceptance and awareness strategies.

-

•

We develop a mobile app-delivered ACT intervention program for PTSD symptoms.

-

•

RCT is used to access the usability, efficacy, and mechanisms of this program.

-

•

This trial may provide a new way to expand the accessibility of interventions for PTSD during COVID-19.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a great impact on the mental health of the global public. Compared to the effects of general stressful events, more severe mental health outcomes, especially posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), have developed during the pandemic (Olff et al., 2021). The prevalence of self-reported modest-to-severe posttraumatic stress symptoms in the global general population ranged from 7 % to 53.8 % during the pandemic (Xiong et al., 2020; Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020), compared to the world average of 3.9 %–7.8 % prior to the pandemic (McLaughlin et al., 2015; Koenen et al., 2017). COVID-19 has resulted in a high demand for PTSD intervention. However, access to effective treatment is still lacking.

The imbalance between intervention demand and supply may be attributed to deficiencies in existing intervention programs (Mavranezouli et al., 2020) and limited accessibility of interventions (J.R. Smith et al., 2020). Firstly, the most common interventions for PTSD (including prolonged exposure therapy, cognitive processing therapy, and narrative exposure therapy) focus on the trauma experience and use exposure-based strategies, with less emphasis on the promotion of positive affect and well-being (Cusack et al., 2016; American Psychological Association, 2019). This focus may lead to low adherence to treatment and high dropout rates (Imel et al., 2013; Garcia et al., 2011). Secondly, under the COVID-19 pandemic in China, restricted medical resources and prolonged isolation have very likely limited access to traditional face-to-face interventions. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop accessible and effective PTSD intervention programs that can be applied to a wide range of populations (Huang et al., 2020). A mobile application-delivered Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) may provide a new approach to large-scale intervention for PTSD.

ACT is a theory-based behavioral intervention that addresses mental disorders using a combination of mindfulness and acceptance techniques (Hayes et al., 2012). This approach has been increasingly used in PTSD intervention and has shown some uniqueness in theoretical conceptualization and practical strategies (Wharton et al., 2019). Firstly, the conceptualization of ACT is sufficient to explain the etiology of PTSD. Avoidance, the main reason for the development of PTSD symptoms (McNally et al., 2015), is the focus of ACT interventions (Smith et al., 2020). The strategies used in ACT, mainly teaching mindfulness and acceptance, can help individuals reduce avoidance. Other strategies include teaching individuals to pay attention to the present, embrace internal experiences, and improve psychological flexibility (Hayes et al., 2012; McCracken and Vowles, 2014). It has been reported that ACT significantly reduced PTSD symptoms in parents of children with life-threatening illnesses (Muscara et al., 2020), combat veterans (Dindo et al., 2020; Gobin et al., 2019), and traumatized adults (Boals and Murrell, 2016). In practical application, ACT has also been shown to be superior to traditional exposure-based therapy in increasing participants' engagement and decreasing the rate of dropout (Phillips et al., 2020; Ong et al., 2018). Finally, the emphasis on improving the well-being and quality of life is also an advantage of ACT (Dindo et al., 2021; Krafft et al., 2019). This emphasis has become even more valuable under the COVID-19 pandemic.

Improving accessibility is another important issue to be addressed in the treatment of PTSD (J.R. Smith et al., 2020). The widespread adoption of the Internet and mobile technologies provides a potential new way to improve the delivery of interventions (Stefanopoulou et al., 2020). Compared with traditional face-to-face therapies, internet interventions, especially when delivered via mobile applications (apps), are less constrained by time and space, allowing large groups of people with varying geographical distances to benefit from intervention (Wickersham et al., 2019). Moreover, app-delivered interventions are appropriate for situations where face-to-face treatment is not available, such as quarantine zones, which may persist during the COVID-19 pandemic (Wu et al., 2020).

App-delivered ACT interventions have been shown to be helpful in the treatment of depression (Pots et al., 2016a; Lappalainen et al., 2014; Larsen et al., 1979), anxiety (Ivanova et al., 2016), and sleep disturbances (Lappalainen et al., 2019). However, in the field of PTSD, the exploration of app-based interventions is still in its infancy, and most studies have focused on providing ACT via other platforms such as the web and video conferences. These internet-based interventions have been used in treating combat veterans (Smith et al., 2021), traumatized women (Fiorillo et al., 2017), and parents of children with life-threatening illness (Muscara et al., 2020). However, internet-based ACT has not yet been integrated with mobile app technology.

In addition to testing the efficacy and usability of an intervention, examining potential mediators of treatment effects could help to identify the mechanisms of symptom change (Kraemer et al., 2002), thus optimizing the development of interventions for PTSD patients (Kangaslampi and Peltonen, 2022). According to the therapeutic model of ACT, the core mediator of therapeutic change is psychological flexibility, made up of six components: acceptance, cognitive defusion, flexible attention to the present, self-as-observer, values-based action, and committed action (Hayes et al., 2011). The mediating effect of psychological flexibility has been shown in the treatment of distress (Flaxman and Bond, 2010), anxiety (Forman et al., 2007; Niles et al., 2014), and depression (Forman et al., 2007; Pots et al., 2016b), and in the promotion of psychological adjustment (Rost et al., 2012). In the field of PTSD, however, only one study has examined the mediating role of psychological flexibility, with a nonsignificant effect (Moyer et al., 2018). Furthermore, the role of the specific components of psychological flexibility in intervention also deserves attention. Researchers have found that specific components of psychological flexibility, such as acceptance (Cederberg et al., 2016; Hesser et al., 2014; Vasiliou et al., 2022), cognitive defusion (Vasiliou et al., 2022; Pakenham et al., 2018; Østergaard et al., 2020), and values and committed action (Østergaard et al., 2020), play a mediating role in ACT treatment for persons with chronic pain, tinnitus, multiple sclerosis, depression, and primary headaches. However, it is noted that different components of psychological flexibility do not have equal effects on symptom change in general psychotherapy (Stockton et al., 2019; Levin et al., 2020). To date, no attempt has been made to systematically investigate the specific roles and interrelationships of different psychological flexibility components in ACT treatment for PTSD. Thus, it is necessary to further explore and clarify the effects of the components of psychological flexibility as mediators of the effects of ACT on PTSD. Treatment can be more efficient if it includes only those aspects that are responsible for change.

The goals of the present study are twofold. Firstly, we will develop a mobile app-delivered ACT intervention for PTSD symptoms and test its usability and efficacy. Given that ACT is a mindfulness-based approach but includes many other components (Banks et al., 2015), we will include an active comparison group in which participants receive mindfulness training only. A waitlist control group will also be included. This design will allow us to test both the absolute efficacy of the ACT intervention as well as its relative advantage beyond mindfulness training. Secondly, we will test the mediating effect of psychological flexibility and further examine the roles and interrelationships among its six components. If the app proves to be efficient, it will be valuable in alleviating PTSD symptoms and enhancing the quality of life in the COVID-19 pandemic and in other similar situations that preclude access to face-to-face therapy.

2. Method

2.1. Study design

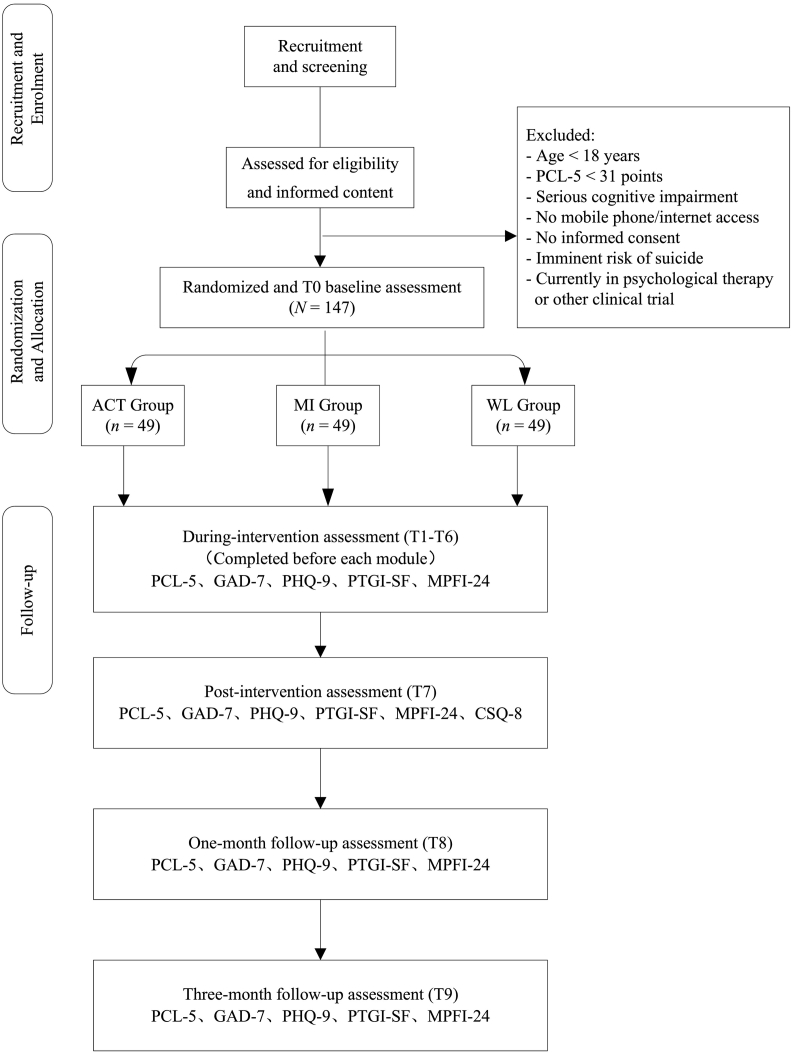

The present study will be a randomized controlled trial involving a one-month mobile app-delivered ACT intervention, with assessments made before the intervention, at five times during treatment, at the end of treatment, and at 1- and 3-month follow-ups. PTSD patients over 18 years old will be recruited through advertisements and screened by self-report questionnaires and a clinical interview. Based on this assessment, eligible participants will be randomly allocated (1:1:1) to the ACT intervention group (ACT group), the Mindfulness intervention group (MI group), or the Waitlist group (WL group). The ACT group (who received the whole ACT intervention) and MI group (who received the mindfulness training component of the ACT intervention) received treatment over the course of one month. Participants in the WL group were assessed without intervention. This trial was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry as ChiCTR2200058408 (http://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=165803). This protocol followed the guidelines of SPIRIT 2013 (Chan et al., 2013), CONSORT 2010 (the CONSORT Group et al., 2010), the TIDieR checklist (Hoffmann et al., 2014), and the mHealth Evidence Reporting and Assessment (mERA) Checklist (Agarwal et al., 2016) (see Appendix A). Fig. 1 presents the CONSORT flow diagram.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flowchart of the study design.

Note. ACT group: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy group; MI group: Mindfulness intervention group; WL group: Waitlist group; PCL-5: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5; GAD-7: Generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale; PTGI-SF: Posttraumatic Growth Inventory Short Form; MPFI-24: Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory; CSQ-8: Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (used only in the ACT group and MI group).

The recruitment, the intervention, the completion of self-reported questionnaires, and the clinical interview will be conducted through the Internet in mainland China. All researchers in this project will be required to have an educational background in psychiatry or psychology.

2.2. Sample size

The results of previous RCTs testing the effects of ACT relative to waitlist and active comparison interventions (Muscara et al., 2020; Dindo et al., 2020; Boals and Murrell, 2016) and a meta-analysis on the effects of ACT in a range of study designs (Gloster et al., 2020) produced a mean overall medium effect size for PTSD and broader psychological disorders. Thus, the expected effect size will be Cohen's d = 0.5 in the present protocol. An a priori power analysis was conducted in G*Power 3.1 to determine the sample size needed to detect a moderate effect size (Cohen's d = 0.5) with alpha = 0.05 and power = 0.85. The power analysis assumed that three independent group means are being compared using two-tailed tests in the “ANOVA: Repeated measures, between factors” member of the F-test family (Faul et al., 2009). The power analysis revealed a required sample size of 108 in total and 36 participants in each group. Considering the drop-out rate of 25.8 % for internet-based interventions at 6-month follow-up (Paganini et al., 2019), at least 147 participants will be needed for randomization with at least 49 participants in each group. Furthermore, the sample size of 147 meets Lemmens et al.'s proposed criterion of a sample size no <40 for tests of mediation (Lemmens et al., 2016).

2.3. Eligibility criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion criteria

Participants included in the study will meet the following selection criteria:

-

1)

Over 18 years and under 65 years old.

-

2)

Diagnosis of PTSD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2022) and the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-5) (Weathers et al., 2018).

-

3)

Able to understand the questionnaires independently.

-

4)

Have mobile communication equipment with Internet access.

-

5)

If taking psychotropic medication, on a stable dose for at least 2 months before study enrolment, and no planned change in medication during the follow-up period.

2.3.2. Exclusion criteria

Participants who meet any of the following criteria will be excluded:

-

1)

Serious cognitive impairment.

-

2)

Uncooperative with questionnaire administration or intervention.

-

3)

Imminent risk of suicide.

-

4)

Currently in psychological therapy or other clinical trials.

2.4. Recruitment, randomization, and blinding

Recruitment will be conducted via advertisements on the Internet and social media. The advertisements will encourage individuals who are suffering from trauma to participate in the intervention. In addition, basic information about the research team, the purpose of the intervention, the rights and responsibilities of research participants, as well as potential risks and benefits of the intervention will be presented in the advertisements. By scanning the QR code on the advertisements, participants can complete the screening questionnaires online and submit their responses through QuestionnaireStar (www.wjx.cn). The screening questionnaires will collect self-report information about demographic characteristics, the nature of the traumatic event, psychological and pharmacological treatment state, symptoms of PTSD assessed by the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5 (PCL-5), co-morbid conditions, and the risk of suicide.

Based on the eligibility criteria, adult participants within the required age range who score 31 or higher on the PCL-5 and meet the eligibility criteria will be invited to the clinical interview. The interviews will: (1) assess the severity of PTSD symptoms using the CAPS-5 scale; (2) provide more information about the current intervention program, including its objectives, applicable population, duration, tasks to be completed, and potential benefits; (3) further confirm important information provided by the participants on the screening scale, including risk of suicide, the ability to understand the questionnaire independently, and other psychological treatment plans; (4) answer participants' questions about the intervention program.

Participants who meet CAPS-5 diagnosed PTSD, show no imminent risk of suicide, not currently in psychotherapy or other clinical trials, and are willing to participate in the trial will be asked to sign an informed consent form. They will then be allocated (1:1:1) to the ACT group, the MI group, or the WL group using a randomization website (https://www.random.org/lists/). A researcher not participating in the study will complete the randomization and grouping. Participants will be informed of the general nature of the study, but they will not know which group they will be in. The intervention will be carried out via a mini-program of the WeChat app, which is one of the most widely used social media software in mainland China. Prior to the intervention, researchers will contact participants via WeChat to obtain the signed informed consent form and to provide the program package. There will be no personal contact during the intervention.

2.5. Ethical considerations

This project has been approved by the Ethics Institutional Review Board of Central China Normal University (No.: CCNU-IRB-202103-010). All participants will be informed that their participation is entirely voluntary and they can withdraw from the study at any time for any reason.

Participants who are not eligible for this trial but show indications of mental health problems will be provided with brief guidance and the recommendation to seek help. For example, college students will be advised to seek support from the mental health center in the university.

We will assess suicide risk during the participant screening process to identify a need for services and to make decisions about inclusion and exclusion from the study. The item related to suicide risk on the self-report Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (“Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way”) will be used to evaluate participants' suicidal ideation (Kroenke et al., 2001). Candidates who rate this item 0 (“Not at all”) or 1 (“Several days”) will continue with the clinical interview component of the screening process. Candidates who rate this item 2 (“More than half the days”) or 3 (“Nearly every day”) will be excluded directly from the study but interviewed for further clinical assessment. The clinical interview will evaluate the possibility of suicide by asking for more detailed information about suicide ideation, risk factors for suicide, protective factors for suicide, and whether there is a suicide plan. Candidates who are considered at risk of suicide will be encouraged to access professional suicide intervention, and the suicide hotline will be offered.

2.6. Intervention

The ACT intervention and Mindfulness intervention will be provided via mini-programs in WeChat. All participants will have a unique account on the platform.

2.6.1. Intervention development

Referring to Bendtsen et al. (2020), we will adopt a three-phase approach to developing the ACT intervention. In the first phase we will gather information from PTSD patients, psychiatrists, and clinical psychologists to develop ideas for what the content of the interventions should be and how the human-computer interaction should be designed. In the second phase we will develop the intervention. The content and scripts will be developed based on the information gathered in the first phase, the ACT Treatment Manual for PTSD (Walser et al., 2007) and related studies (Kelly et al., 2020; Reyes et al., 2020). In the third phase the intervention will be programmed as a mobile app and tested for optimization. Game-inspired infographics, personalized options, and open-ended questions will be used to increase users' sense of autonomy and control (Comello et al., 2016), which help to increase users' engagement (Fonzo et al., 2019). Pilot interviews will be conducted with PTSD patients to resolve technical issues and investigate how the final interventions are perceived. Based on the feedback, the intervention will be revised and adjusted. This process will be repeated as necessary until the developers and PTSD patients reach a consensus on the intervention script. Finally, the interventions developed in the third phase will be tested in a randomized controlled trial to evaluate their usability and efficacy.

2.6.2. ACT intervention

The mobile app-delivered ACT intervention is a self-help program consisting of one introductory module and six intervention modules on the following themes: 1) exploring ways to cope; 2) control as the problem; 3) options beyond control; 4) self-as-observer; 5) value living; 6) committed action. Details of the introductory and the six modules can be found in Appendix B.

Participants in the ACT group will complete six intervention modules with an interval of five days, 30–60 min per module, over the course of one month. After registration, participants will be able to directly access the introductory module, which contains a brief introduction to the symptoms of PTSD, the concept and process of the ACT intervention, and how to use the app. Participants will not be able to move to the next module without completing the introductory module. That is, the six modules will be unlocked sequentially after the participants complete the previous one. Participants' progress can be tracked in the backend, and a reminder will be given by the program if the intervention is not completed within the given time.

2.6.3. Mindfulness intervention

Mindfulness is one of the most important intervention strategies taught in ACT (Godbee and Kangas, 2020). We will use a dismantling paradigm to disengage mindfulness training from the standard ACT intervention. This will allow us to investigate the relative efficacy of the whole ACT intervention compared to the Mindfulness component in alleviating PTSD symptoms. That is, we will be able to address the question of whether one part of the ACT intervention is as effective as the whole ACT intervention (Bell et al., 2013).

The mindfulness exercises in the six modules of the ACT intervention will be selected as the material for the Mindfulness intervention, which will include an introductory module and six intervention modules, each containing three to five mindfulness exercises. Firstly, the introductory module will provide a brief introduction to the symptoms of PTSD, the concept and process of achieving mindfulness, and how to use this program. Then participants will complete the six modules of mindfulness training with an interval of five days, 20–40 min per module, and the training will last one month. The basic design and functionality of the Mindfulness intervention will be consistent with those in the ACT intervention, including a user-friendly design, sequentially unlocked modules, and reminders to complete the intervention modules as planned.

2.6.4. Waitlist group

Participants in the Waitlist group will only complete the questionnaire measures, with the measurement time points matched to the ACT group and the MI group. The Waitlist group will receive no intervention during the study, but at the end of the research, the ACT intervention program will be offered.

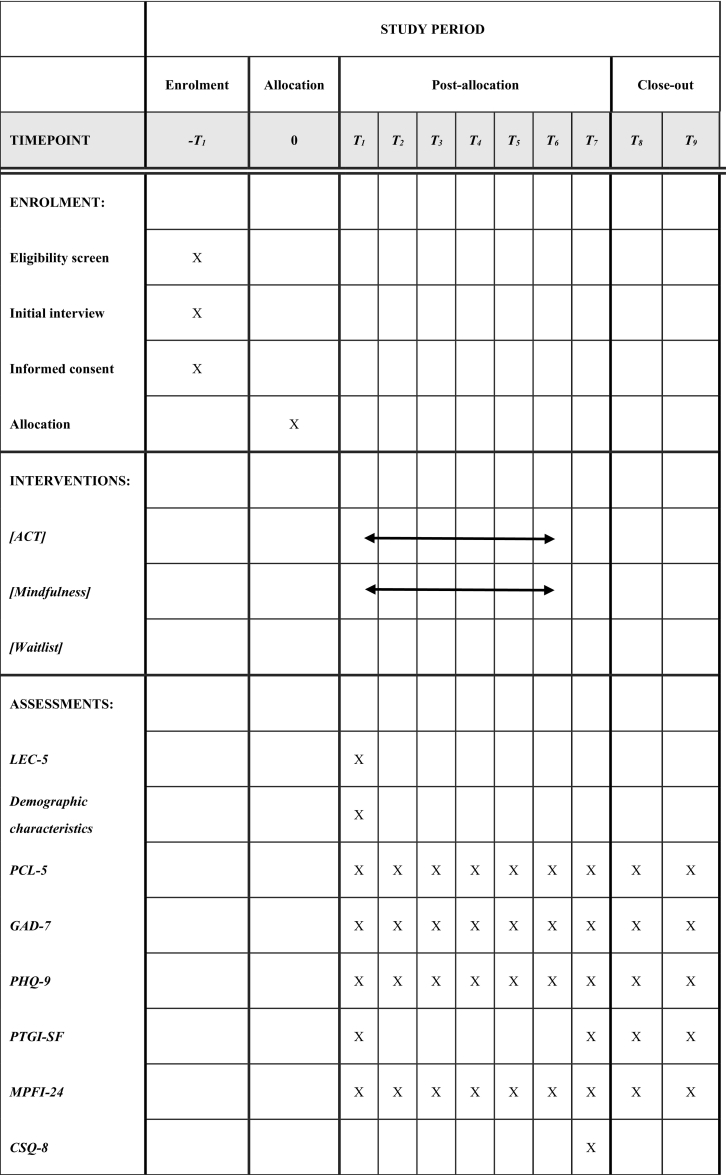

2.7. Measures

All questionnaire data will be collected online. We will measure background information as part of the screening questionnaires. Outcome and mediating variables will be assessed at baseline, at five times during the intervention, and post-treatment. Long-term follow-up will be conducted 1- and 3-months post-treatment. The assessment time points are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Content for the schedule of enrolment, interventions, and assessments.

Note: T1-T6 measures will be taken before the corresponding six modules. T7 measures will be taken after the whole intervention. T8 and T9 measures will be taken 1 and 3 months after intervention ended.

LEC-5: Life Events Checklist for DSM-5; PCL-5: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale; PTGI-SF: Posttraumatic Growth Inventory Short Form; MPFI-24: Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory; CSQ-8: Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (used only in the ACT group and MI group).

2.7.1. Background information

A self-developed questionnaire will be used to collect information on demographic characteristics, including age, gender, residence, education level, marital status, work status, self-assessed income status, and occupation type.

Trauma exposure will be assessed by the 17-item Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) (Weathers et al., 2013a), which measures exposure to 17 potentially traumatic events (e.g., “sexual assault”) and 6 levels of exposure (“happened to me”, “witnessed it”, “learned about it”, “part of my job”, “not sure”, and “doesn't apply”). In addition, the age at the time of the trauma will be collected.

2.7.2. Primary outcome

PTSD symptoms will be assessed by the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5 (PCL-5) (Weathers et al., 2013b). The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses PTSD symptoms including intrusion (5 items), avoidance (2 items), negative changes in cognition and mood (7 items), and arousal (6 items). Each item is rated from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”), resulting in a total score of 0 to 80, where higher scores indicate higher level of PTSD symptoms. A tentative diagnosis of PTSD is defined as a total score at or above 31 (Franklin et al., 2015). The Chinese version of PCL-5 has shown good reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.91) (Cheng et al., 2020).

2.7.3. Secondary outcomes

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al., 2006) is a seven-item self-report measure that assesses anxiety symptoms in the past two weeks. Higher scores indicate more severe anxiety symptoms. The Chinese version of the GAD-7 has shown excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.89) (Tong et al., 2016).

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002) is a nine-item self-report measure that assesses symptoms of depression in the past two weeks. Higher scores indicate more depression symptoms. The Chinese version of the PHQ-9 has shown excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.89) (Chen et al., 2013).

The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory Short Form (PTGI-SF) (Cann et al., 2010) is a self-report measure of posttraumatic growth. The 10-item Short Form was adapted from the original PTGI 21-item scale (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1996). Items are rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (“I did not experience this change”) to 5 (“I experienced this change to a very great degree”), with higher scores indicate higher levels of psychosocial growth. It has demonstrated good internal consistency in the Chinese culture (Cronbach's α = 0.86) (Liu et al., 2020).

2.7.4. Mediating variables

The Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory (MPFI-24) (Rolffs et al., 2018) is a 24-item self-report questionnaire used to measure global psychological flexibility and its six components (acceptance, present moment awareness, self as context, defusion, values, committed action). Items are rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“never true”) to 6 (“always true”). Ratings are averaged and higher scores indicate greater psychological flexibility. The measure has demonstrated good internal consistency (Grégoire et al., 2020).

2.7.5. Usability variable

The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) (Larsen et al., 1979) will be used to assess the usability of the intervention program. The CSQ-8 consists of eight items rated on a scale from 1 to 4, with higher ratings indicating higher usability. Summed ratings between 8–20, 21–26, and 27–32 are viewed as indicating low, medium, and high levels of usability, respectively. CSQ-8 has excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.93) (Trompetter et al., 2015).

2.8. Statistical analysis

All available data will be used in the analyses based on the intention-to-treat principle. Baseline characteristics will be compared among the ACT group, MI group, and WL group using ANOVAs or chi-square tests. Results with two-sided p < .05 will be considered statistically significant.

Latent growth curve modeling (LGCM) will be conducted to analyze the effect of interventions, determine the potential moderators of treatment effects, and evaluate the potential mediating effects of psychological flexibility and its components (Bollen and Curran, 2006; Duncan et al., 2013). LGCM is suited to the present research because it allows simultaneous analysis at multiple time points, so we can examine the continuous change of mediators and outcomes during the treatment phase (Thiruchselvam et al., 2019).

To estimate intervention effects, we will use PTSD symptoms, depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and posttraumatic growth as repeated measures at each time point in the three groups (ACT group, MI group, and WL group). These values are the observed indicators, with the latent intercept and slope being estimated. Referring to previous research (Mason et al., 2003), we will firstly estimate four unconditional LGCMs to examine the shape of the growth curves in PTSD symptoms, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic growth, respectively. Then, to examine the intervention effects, four expanded, conditional LGCMs that include “group” as an exogenous predictor of slope will be estimated. Intervention effects will be indicated by a statistically significant estimate of the effect of the group variable on changes in primary and secondary outcomes. In addition, to determine potential moderators of intervention effects, demographic characteristics (age, gender, and the number of traumatic events), initial symptom levels (initial PTSD, depression, and anxiety), and psychological characteristics (initial psychological flexibility and posttraumatic growth) will be used as predictors of the slope in expanded, conditional LGCMs.

To test mediation, repeated measurements of symptoms of PTSD and psychological flexibility collected at all time points will be included as observed indicators, with the latent intercept and slope factor being estimated. The tests of potential mediation effects will be conducted in three steps (Cheong et al., 2003). Firstly, an unconditional parallel-process of PTSD symptoms and psychological flexibility will be specified to estimate the growth trajectories and temporal stability for the ACT group and WL group. Secondly, conditional LGCMs will be used to investigate the effects of the intervention on PTSD symptoms and the components of psychological flexibility as potential mediators. Thirdly, the longitudinal mediation model will be tested to examine the changes in slopes of the outcomes and potential mediators, so we can investigate whether the ACT intervention reduces PTSD symptoms via increasing psychological flexibility.

All LGCMs will be performed using maximum likelihood (ML) estimation. Compared with traditional missing data methods, ML yields more efficient and less biased parameters even when the assumption of data being missing at random is not strictly satisfied (Little and Rubin, 1989). Model fit will be evaluated using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and the Relative Chi-Square Ratio (χ2/df). CFI > 0.90, RMSEA and SRMR <0.08, and χ2/df < 3 indicate good model fit (Hu and Bentler, 1998). Preliminary statistical analysis and LGCM will be performed using SPSS 20.0 and Mplus 8.0, respectively.

3. Discussion

Due to the impact of COVID-19 and its subsequent effects, the incidence of PTSD is increasing dramatically around the world (Olff et al., 2021). However, access to reliable mental health treatment is still limited (Wu et al., 2020). As a result, it is necessary to develop effective, accessible PTSD interventions that can be applied in large populations. The widespread adoption of mobile technologies in China provides a potential new way, namely the use of smartphone apps, to improve mental health care delivery (Van Ameringen et al., 2017). The primary aim of the present study is to investigate the usability, efficacy, and mechanism of the effects of a mobile app-delivered ACT intervention for PTSD symptoms.

The results of the current trial will have implications for PTSD treatment. As the pandemic continues, public mental health will become an increasingly prominent public issue, and the gap between the demand for mental health services and the available supply will likely continue to be significant. In this context, app-delivered interventions have the potential to be used as primary, brief “minimal interventions” before the use of traditional psychological therapies. This approach is indicated by the stepped care model (Bower and Gilbody, 2005). If shown to be efficacious, the current app-delivered ACT intervention program will be expected to serve as “the first step” for the general population in the epidemic. This approach can help to improve the existing psychological service system, optimize the allocation of psychological service resources, and provide treatment while face-to-face psychotherapy is unavailable during the pandemic. However, it should be noted that the current trial will evaluate the intervention effects using only self-reported outcome measures, which may create a risk of bias due to social desirability and shared method variance and reduce the generalizability of the results to clinical practice (Tønning et al., 2019).

Funding

This study is supported by a grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 32171086). Funding sources had no role in the study design and will have no role in the execution, analyses, interpretation, or presentation of results.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

ZZ, CZ, CS, and LL contributed to the design of the research. ZZ wrote the manuscript with support from CZ. CS aided in the language editing and polishing. LL provided input into the data analysis procedures. ZR supervised the project. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2022.100585.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

SPIRIT 2013 Checklist, CONSORT 2010 Checklist, TIDieR Checklist, and mERA Checklist.

Modules and contents of the mobile app-delivered ACT intervention for PTSD, and Content pictures of the mobile app-delivered ACT intervention for PTSD.

References

- Agarwal S., LeFevre A.E., Lee J., L’Engle K., Mehl G., Sinha C., et al. Guidelines for reporting of health interventions using mobile phones: mobile health (mHealth) evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist. BMJ. 2016 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Fifth edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; Washington, DC: 2022. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Banks K., Newman E., Saleem J. An overview of the research on mindfulness-based interventions for treating symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review: mindfulness and PTSD. J. Clin. Psychol. 2015;71:935–963. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E.C., Marcus D.K., Goodlad J.K. Are the parts as good as the whole? A meta-analysis of component treatment studies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013;81:722–736. doi: 10.1037/a0033004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen M., Bendtsen P., Henriksson H., Henriksson P., Müssener U., Thomas K., et al. The Mobile health multiple lifestyle behavior interventions across the lifespan (MoBILE) research program: protocol for development, evaluation, and implementation. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.2196/14894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boals A., Murrell A.R. I am > trauma: experimentally reducing event centrality and PTSD symptoms in a clinical trial. J. Loss Trauma. 2016;21:471–483. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2015.1117930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K.A., Curran P.J. John Wiley & Sons; 2006. Latent Curve Models: A Structural Equation Perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Bower P., Gilbody S. Stepped care in psychological therapies: access, effectiveness and efficiency: narrative literature review. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2005;186:11–17. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cann A., Calhoun L.G., Tedeschi R.G., Taku K., Vishnevsky T., Triplett K.N., et al. A short form of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2010;23:127–137. doi: 10.1080/10615800903094273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederberg J.T., Cernvall M., Dahl J., von Essen L., Ljungman G. Acceptance as a mediator for change in acceptance and commitment therapy for persons with chronic pain? Int. J. Behav. Med. 2016;23:21–29. doi: 10.1007/s12529-015-9494-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A.-W., Tetzlaff J.M., Gotzsche P.C., Altman D.G., Mann H., Berlin J.A., et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7586. e7586-e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Fang Y., Chiu H., Fan H., Jin T., Conwell Y. Validation of the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire to screen for major depression in a Chinese primary care population: PHQ-9 in Chinese primary care. Asia Pac. Psychiatry. 2013;5:61–68. doi: 10.1111/appy.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng P., Xu L.-Z., Zheng W.-H., Ng R.M.K., Zhang L., Li L.-J., et al. Psychometric property study of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) in Chinese healthcare workers during the outbreak of corona virus disease 2019. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;277:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong J., MacKinnon D.P., Khoo S.T. Investigation of mediational processes using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2003;10:238–262. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM1002_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comello M.L.G., Qian X., Deal A.M., Ribisl K.M., Linnan L.A., Tate D.F. Impact of game-inspired infographics on user engagement and information processing in an eHealth program. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016;18 doi: 10.2196/jmir.5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack K., Jonas D.E., Forneris C.A., Wines C., Sonis J., Middleton J.C., et al. Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016;43:128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dindo L., Johnson A.L., Lang B., Rodrigues M., Martin L., Jorge R. Development and evaluation of an 1-day acceptance and commitment therapy workshop for veterans with comorbid chronic pain, TBI, and psychological distress: outcomes from a pilot study. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2020;90 doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2020.105954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dindo L., Roddy M.K., Boykin D., Woods K., Rodrigues M., Smith T.L., et al. Combination outreach and wellness intervention for distressed rural veterans: results of a multimethod pilot study. J. Behav. Med. 2021;44:440–453. doi: 10.1007/s10865-020-00177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan T.E., Duncan S.C., Strycker L.A. Routledge; 2013. An Introduction to Latent Variable Growth Curve Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- Faul F., Erdfelder E., Buchner A., Lang A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo D., McLean C., Pistorello J., Hayes S.C., Follette V.M. Evaluation of a web-based acceptance and commitment therapy program for women with trauma-related problems: a pilot study. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2017;6:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2016.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flaxman P.E., Bond F.W. A randomised worksite comparison of acceptance and commitment therapy and stress inoculation training. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010;48:816–820. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonzo G.A., Fine N.B., Wright R.N., Achituv M., Zaiko Y.V., Merin O., et al. Internet-delivered computerized cognitive & affective remediation training for the treatment of acute and chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: Two randomized clinical trials. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019;115:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman E.M., Herbert J.D., Moitra E., Yeomans P.D., Geller P.A. A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Behav. Modif. 2007;31:772–799. doi: 10.1177/0145445507302202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin C.L., Piazza V., Chelminski I., Zimmerman M. Defining subthreshold PTSD in the DSM-IV literature: a look toward DSM-5. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2015;203:574–577. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia H.A., Kelley L.P., Rentz T.O., Lee S. Pretreatment predictors of dropout from cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. Psychol. Serv. 2011;8:1–11. doi: 10.1037/a0022705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gloster A.T., Walder N., Levin M.E., Twohig M.P., Karekla M. The empirical status of acceptance and commitment therapy: a review of meta-analyses. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2020;18:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobin R.L., Strauss J.L., Golshan S., Allard C.B., Bomyea J., Schnurr P.P., et al. Gender differences in response to acceptance and commitment therapy among operation enduring Freedom/Operation iraqi Freedom/Operation new Dawn veterans. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godbee M., Kangas M. The relationship between flexible perspective taking and emotional well-being: a systematic review of the “self-as-context” component of acceptance and commitment therapy. Behav. Ther. 2020;51:917–932. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2019.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grégoire S., Gagnon J., Lachance L., Shankland R., Dionne F., Kotsou I., et al. Validation of the English and French versions of the multidimensional psychological flexibility inventory short form (MPFI-24) J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2020;18:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of PTSD in Adults. American Psychological Association Summary of the clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Am. Psychol. 2019;74:596–607. doi: 10.1037/amp0000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C., Villatte M., Levin M., Hildebrandt M. Open, aware, and active: contextual approaches as an emerging trend in the behavioral and cognitive therapies. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2011;7:141–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C., Strosahl K.D., Wilson K.G. English edition. Wilson; Kelly: 2012. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Second Edition: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change. [Google Scholar]

- Hesser H., Westin V.Z., Andersson G. Acceptance as a mediator in internet-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for tinnitus. J. Behav. Med. 2014;37:756–767. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann T.C., Glasziou P.P., Boutron I., Milne R., Moher D., Altman D.G., Barbour V., Macdonald H., Johnston M., Lamb S.E., Dixon-Woods M., McCulloch P., Wyatt J.C., Chan A.W., Michie S. Better reporting of interventions: template forintervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014:348. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods. 1998;3:424–453. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Wei F., Hu L., Wen L., Liao G., Su J., et al. The post-traumatic stress disorder impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020;32:587–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel Z.E., Laska K., Jakupcak M., Simpson T.L. Meta-analysis of dropout in treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013;81:394–404. doi: 10.1037/a0031474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova E., Lindner P., Ly K.H., Dahlin M., Vernmark K., Andersson G., et al. Guided and unguided acceptance and commitment therapy for social anxiety disorder and/or panic disorder provided via the internet and a smartphone application: a randomized controlled trial. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016;44:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangaslampi S., Peltonen K. Mechanisms of change in psychological interventions for posttraumatic stress symptoms: a systematic review with recommendations. Curr. Psychol. 2022;41:258–275. doi: 10.1007/s12144-019-00478-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M.M., Reilly E.D., Ahern M., Fukuda S. Improving social support for a veteran with PTSD using a manualized acceptance and commitment therapy approach. Clin. Case Stud. 2020;19:189–204. doi: 10.1177/1534650120915781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen K.C., Ratanatharathorn A., Ng L., McLaughlin K.A., Bromet E.J., Stein D.J., et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health surveys. Psychol. Med. 2017;47:2260–2274. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H.C., Wilson G.T., Fairburn C.G., Agras W.S. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:877. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krafft J., Potts S., Schoendorff B., Levin M.E. A randomized controlled trial of multiple versions of an acceptance and commitment therapy matrix app for well-being. Behav. Modif. 2019;43:246–272. doi: 10.1177/0145445517748561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy Y., Nagarajan R., Saya G.K., Menon V. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002;32:509–515. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen P., Granlund A., Siltanen S., Ahonen S., Vitikainen M., Tolvanen A., et al. ACT internet-based vs face-to-face? A randomized controlled trial of two ways to deliver acceptance and commitment therapy for depressive symptoms: an 18-month follow-up. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014;61:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen P., Langrial S., Oinas-Kukkonen H., Muotka J., Lappalainen R. ACT for sleep - internet-delivered self-help ACT for sub-clinical and clinical insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2019;12:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen D.L., Attkisson C.C., Hargreaves W.A., Nguyen T.D. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval. Program Plann. 1979;2:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens L.H.J.M., Müller V.N.L.S., Arntz A., Huibers M.J.H. Mechanisms of change in psychotherapy for depression: an empirical update and evaluation of research aimed at identifying psychological mediators. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016;50:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin M.E., Krafft J., Hicks E.T., Pierce B., Twohig M.P. A randomized dismantling trial of the open and engaged components of acceptance and commitment therapy in an online intervention for distressed college students. Behav. Res. Ther. 2020;126 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2020.103557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R.J.A., Rubin D.B. The analysis of social science data with missing values. Sociol. Methods Res. 1989;18:292–326. doi: 10.1177/0049124189018002004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Thorp S.R., Moreno L., Wells S.Y., Glassman L.H., Busch A.C., et al. Videoconferencing psychotherapy for veterans with PTSD: results from a randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2020;26:507–519. doi: 10.1177/1357633X19853947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W.A., Kosterman R., Hawkins J.D., Haggerty K.P., Spoth R.L. Reducing adolescents’ growth in substance use and delinquency: randomized trial effects of a parent-training prevention intervention. Prev. Sci. 2003;4:203–212. doi: 10.1023/A:1024653923780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavranezouli I., Megnin-Viggars O., Daly C., Dias S., Stockton S., Meiser-Stedman R., et al. Research review: psychological and psychosocial treatments for children and young people with post-traumatic stress disorder: a network meta-analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2020;61:18–29. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken L.M., Vowles K.E. Acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness for chronic pain: model, process, and progress. Am. Psychol. 2014;69:178–187. doi: 10.1037/a0035623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin K.A., Koenen K.C., Friedman M.J., Ruscio A.M., Karam E.G., Shahly V., et al. Subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015;77:375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally R.J., Robinaugh D.J., Wu G.W.Y., Wang L., Deserno M.K., Borsboom D. Mental disorders as causal systems: a network approach to posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2015;3:836–849. doi: 10.1177/2167702614553230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer D.N., Page A.R., McMakin D.Q., Murrell A.R., Lester E.G., Walker H.A. The impact of acceptance and commitment therapy on positive parenting strategies among parents who have experienced relationship violence. J. Fam. Violence. 2018;33:269–279. doi: 10.1007/s10896-018-9956-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muscara F., McCarthy M.C., Rayner M., Nicholson J.M., Dimovski A., McMillan L., et al. Effect of a videoconference-based online group intervention for traumatic stress in parents of children with life-threatening illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niles A.N., Burklund L.J., Arch J.J., Lieberman M.D., Saxbe D., Craske M.G. Cognitive mediators of treatment for social anxiety disorder: comparing acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Behav. Ther. 2014;45:664–677. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff M., Primasari I., Qing Y., Coimbra B.M., Hovnanyan A., Grace E., et al. Mental health responses to COVID-19 around the world. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021;12 doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1929754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong C.W., Lee E.B., Twohig M.P. A meta-analysis of dropout rates in acceptance and commitment therapy. Behav. Res. Ther. 2018;104:14–33. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard T., Lundgren T., Zettle R.D., Landrø N.I., Haaland V.Ø. Psychological flexibility in depression relapse prevention: processes of change and positive mental health in group-based ACT for residual symptoms. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:528. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganini S., Lin J., Kählke F., Buntrock C., Leiding D., Ebert D.D., et al. A guided and unguided internet- and mobile-based intervention for chronic pain: health economic evaluation alongside a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham K.I., Mawdsley M., Brown F.L., Burton N.W. Pilot evaluation of a resilience training program for people with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil. Psychol. 2018;63:29–42. doi: 10.1037/rep0000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M.A., Chase T., Bautista C., Tang A., Teng E.J. Using acceptance and commitment therapy techniques to enhance treatment engagement in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Bull. Menn. Clin. 2020;84:264–277. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2020.84.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pots W.T.M., Fledderus M., Meulenbeek P.A.M., ten Klooster P.M., Schreurs K.M.G., Bohlmeijer E.T. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a web-based intervention for depressive symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2016;208:69–77. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.146068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pots W.T.M., Trompetter H.R., Schreurs K.M.G., Bohlmeijer E.T. How and for whom does web-based acceptance and commitment therapy work? Mediation and moderation analyses of web-based ACT for depressive symptoms. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:158. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0841-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes A.T., Serafica R., Sojobi A. College student veterans’ experience with a mindfulness- and acceptance-based mobile app intervention for PTSD: a qualitative study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020;34:497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolffs J.L., Rogge R.D., Wilson K.G. Disentangling components of flexibility via the hexaflex model: development and validation of the multidimensional psychological flexibility inventory (MPFI) Assessment. 2018;25:458–482. doi: 10.1177/1073191116645905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost A.D., Wilson K., Buchanan E., Hildebrandt M.J., Mutch D. Improving psychological adjustment among late-stage ovarian cancer patients: examining the role of avoidance in treatment. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2012;19:508–517. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.R., Workneh A., Yaya S. Barriers and facilitators to help-seeking for individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. J. Trauma. Stress. 2020;33:137–150. doi: 10.1002/jts.22456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B.M., Smith G.S., Dymond S. Relapse of anxiety-related fear and avoidance: conceptual analysis of treatment with acceptance and commitment therapy. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2020;113:87–104. doi: 10.1002/jeab.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B.P., Coe E., Meyer E.C. Acceptance and commitment therapy delivered via telehealth for the treatment of co-occurring depression, PTSD, and nicotine use in a male veteran. Clin. Case Stud. 2021;20:75–91. doi: 10.1177/1534650120963183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:1092. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanopoulou E., Lewis D., Mughal A., Larkin J. Digital interventions for PTSD symptoms in the general population: a review. Psychiatry Q. 2020;91:929–947. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09745-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockton D., Kellett S., Berrios R., Sirois F., Wilkinson N., Miles G. Identifying the underlying mechanisms of change during acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): a systematic review of contemporary mediation studies. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2019;47:332–362. doi: 10.1017/S1352465818000553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi R.G., Calhoun L.G. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma. Stress. 1996;9:455–471. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- the CONSORT Group. Schulz K.F., Altman D.G., Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Trials. 2010;11:32. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiruchselvam T., Dozois D.J.A., Bagby R.M., Lobo D.S.S., Ravindran L.N., Quilty L.C. The role of outcome expectancy in therapeutic change across psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy for depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;251:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X., An D., McGonigal A., Park S.-P., Zhou D. Validation of the generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) among Chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2016;120:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tønning M.L., Kessing L.V., Bardram J.E., Faurholt-Jepsen M. Methodological challenges in randomized controlled trials on smartphone-based treatment in psychiatry: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019;21 doi: 10.2196/15362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trompetter H.R., Bohlmeijer E.T., Veehof M.M., Schreurs K.M.G. Internet-based guided self-help intervention for chronic pain based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J. Behav. Med. 2015;38:66–80. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9579-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ameringen M., Turna J., Khalesi Z., Pullia K., Patterson B. There is an app for that! The current state of mobile applications (apps) for DSM-5 obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and mood disorders: VAN AMERINGEN et al. Depress. Anxiety. 2017;34:526–539. doi: 10.1002/da.22657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasiliou V.S., Karademas E.C., Christou Y., Papacostas S., Karekla M. Mechanisms of change in acceptance and commitment therapy for primary headaches. Eur. J. Pain. 2022;26:167–180. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walser R.D., Westrup D., Hayes S.C. New Harbinger Publications; 2007. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Trauma-Related Problems: A Practitioner’s Guide to Using Mindfulness and Acceptance Strategies. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F., Blake D., Schnurr P., Kaloupek D., Marx B., Keane T. 2013. The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Instrument Available from the National Center for PTSD. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F.W., Litz B.T., Keane T.M., Palmieri P.A., Marx B.P., Schnurr P.P. The ptsd Checklist for dsm-5 (pcl-5). Scale Available Natl Cent PTSD Www Ptsd Va Gov. 2013. p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F.W., Bovin M.J., Lee D.J., Sloan D.M., Schnurr P.P., Kaloupek D.G., et al. The clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM–5 (CAPS-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychol. Assess. 2018;30:383–395. doi: 10.1037/pas0000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton E., Edwards K.S., Juhasz K., Walser R.D. Acceptance-based interventions in the treatment of PTSD: group and individual pilot data using acceptance and commitment therapy. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2019;14:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wickersham A., Petrides P.M., Williamson V., Leightley D. Efficacy of mobile application interventions for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Digit Health. 2019;5 doi: 10.1177/2055207619842986. 205520761984298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Guo X., Shang Z., Sun Z., Jia Y., Sun L., et al. China experience from COVID-19: mental health in mandatory quarantine zones urgently requires intervention. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy. 2020;12:S3–S5. doi: 10.1037/tra0000609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M.W., Gill H., Phan L., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SPIRIT 2013 Checklist, CONSORT 2010 Checklist, TIDieR Checklist, and mERA Checklist.

Modules and contents of the mobile app-delivered ACT intervention for PTSD, and Content pictures of the mobile app-delivered ACT intervention for PTSD.