Abstract

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is highly expressed in PCa, which gradually increases in high-grade tumors, metastatic tumors, and tumors nonresponsive to androgen deprivation therapy. PSMA has been a topic of interest during the past decade for both diagnostic and therapeutic targets. Radioligand therapy (RLT) utilizes the delivery of radioactive nuclides to tumors and tumor-associated targets, and it has shown better efficacy with minimal toxicity compared to other systemic cancer therapies. Nuclear medicine has faced a new turning point claiming theranosis as the core of academic identity, since new RLTs have been introduced to clinics through the official new drug development processes for approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or European Medical Agency. Recently, PSMA targeting RLT was approved by the US FDA in March 2022. This review introduces PSMA RLT focusing on ongoing clinical trials to enhance our understanding of nuclear medicine theranosis and strive for the development of new radiopharmaceuticals.

Keywords: PSMA, Radioligand therapy, Prostate cancer

Introduction

Clinical Significance of Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most common male cancers and a common cause of cancer-related deaths in men worldwide [1]. Curative intent treatment for PCa, including radical prostatectomy (RP), external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), and brachytherapy, is possible when the tumor is localized within the prostate [2]. Even after successful curative treatment is completed, biochemical recurrence (BCR), which is defined as the increase of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, develops in 15–50% of patients within 5 years [3–5]. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is considered the standard of care (SOC) when salvage surgery or radiotherapy is not an option, but most patients eventually fail to maintain suppression of PSA levels, which is known as castration resistant PCa (CRPCa). Moreover, metastatic CRPCa (mCRPCa) remains incurable and fatal, despite the availability of multiple therapeutic options that delay disease progression and prolong life [6].

Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a type II, 750-amino acid transmembrane protein (100–120 kDa) that is anchored in the cell membrane of prostate epithelial cells. PSMA is highly expressed in primary epithelial tumor cells and metastatic lymph nodes of PCa. PSMA expression particularly increases in high-grade tumors, metastatic tumors, tumors nonresponsive to ADT, and tumors showing high tumor neo-vasculatures [7–9]. High PSMA expression was independently associated with reduced survival in patients with mCRPCa [10], and it also has been reported to be an independent biomarker of poor prognosis throughout the course of PCa and across anatomical sites [11, 12]. Thus, the possibility of using PSMA as a therapeutic target has been a topic of interest during the past decade.

In the Era of Radiopharmaceutical Therapy Acquiring FDA or EMA Approval

Therapy using radioisotopes is often referred to by different names, such as radioisotope therapy and radioligand therapy (RLT). Radiopharmaceutical therapy (RPT) is a newly coined term to define a novel type of cancer therapy that utilizes the delivery of radioactive nuclides to tumors and tumor-associated targets. A long history of RPT started with radioactive iodine, which was firstly used for the treatment of metastatic thyroid cancer in 1941. It was long before the establishment of the modern concept of new investigational drug application (NDA) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or European Medical Agency (EMA). Hence, clinical protocols of radioiodine therapy were empirically determined without elaborate steps, including dose escalation studies or determination of the maximal tolerated dose. Nuclear medicine physicians might be unfamiliar with the concept of NDA in the past. Currently, market authorization through well-designed clinical trials is an essential requisite for the introduction of a new drug in the clinical field.

Nuclear medicine has faced a new turning point, claiming theranosis as the core of academic identity, since new RPTs have been introduced in clinics one after another through the official new drug development processes. 177Lu-DOTA-TATE (Lutathera®) for peptide receptor RLT (PRRT) acquired approvals from both the FDA and EMA, followed by 223Ra dichloride (Xofigo®), which has opened a new chapter in the era of RPT for cancer. Recently, PSMA targeting RLT was approved by the US FDA in March 2022. We are going to review clinical trials using PSMA RLT to enhance our understanding of nuclear medicine theranosis and strive for the development of new RPTs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ongoing clinical trials for prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) targeting radioligand therapy (RLT)

| RLT agent | Status | Title | Properties | NCT number | Sponsor | Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 for mCPRCa* | 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Active, not recruiting | 177Lu-PMSA-617 in Metastatic Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer (VISION) | Phase III | NCT03511664 | Endocyte | 33 |

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | 177Lu-PSMA-617 vs Docetaxel in Metastatic Castration Resistant and PSMA-Positive Prostate Cancer | Phase II | NCT04663997 | Canadian Cancer Trials Group | ||

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | Radiometabolic Therapy (RMT) With 177Lu-PSMA-617 in Advanced Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer (LU-PSMA) | Phase II | NCT03454750 | IRST IRCCS, Italy | ||

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Not yet recruiting | Study of 177Lu-PSMA-617 In Metastatic Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer in Japan | Phase II | NCT05114746 | Norvatis Pharmaceuticals | ||

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 to earlier treatment lines | 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | An International Prospective Open-label, Randomized, Phase III Study Comparing 177Lu-PSMA-617 in Combination With Soc, Versus SoC Alone, in Adult Male Patients With mHSPC (PSMAddition) | Phase III | NCT04720157 | Norvatis Pharmaceuticals | |

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | 177Lu-PSMA-617 vs. Androgen Receptor-directed Therapy in the Treatment of Progressive Metastatic Castrate Resistant Prostate Cancer (PSMAfore) | Phase III | NCT04689828 | Norvatis Pharmaceuticals | ||

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | Enzalutamide With Lu PSMA-617 Versus Enzalutamide Alone in Men With Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer (ENZA-p) | Phase II | NCT04419402 | Australian and New Zealand Urogenital and Prostate Cancer Trials Group | ||

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 in Oligo-metastatic Hormone Sensitive Prostate Cancer (BULLSEYE) | Phase II | NCT04443062 | Radbound Univ., Netherlands | 43,44 | |

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Unknown | A Trial of 177Lu-PSMA-617 Theranostic Versus Cabazitaxel in Progressive Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer (TheraP) | Phase II | NCT 03,392,428 | Australian and New Zealand Urogenital and Prostate Cancer Trials Group | 47 | |

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 new strategies | 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | 177Lu-PSMA-617 and Pembrolizumab in Treating Patients With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer | Phase I | NCT03805594 | UC california | |

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Active, not recruiting | PRINCE (PSMA-lutetium Radionuclide Therapy and ImmuNotherapy in Prostate CancEr) (PRINCE) | Phase I,II | NCT03658447 | Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Australia | ||

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | 177Lu-PSMA-617 Therapy and Olaparib in Patients With Metastatic Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer (LuPARP) | Phase I | NCT03874884 | Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Australia | ||

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | A Study of Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy and 177Lu-PSMA-617 for the Treatment of Prostate Cancer | Phase I | NCT05079698 | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center | ||

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | Dosimetry, Safety and Potential Benefit of 177Lu-PSMA-617 Prior to Prostatectomy (LuTectomy) | Phase I,II | NCT04430192 | Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Australia | 52 | |

| 177Lu-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | In Men With Metastatic Prostate Cancer, What is the Safety and Benefit of Lutetium-177 PSMA Radionuclide Treatment in Addition to Chemotherapy (UpFrontPSMA) | Phase II | NCT04343885 | Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Australia | 53 | |

| New RLT ligands | 177Lu-PSMA-I&T | Recruiting | Study Evaluating mCRPC Treatment Using PSMA [Lu-177]-PNT2002 Therapy After Second-line Hormonal Treatment (SPLASH) | Phase III | NCT04647526 | POINT Biopharma | 57 |

| 177Lu-PSMA-I&T | Recruiting | 177Lu-PSMA-I&T Prior to Radical Prostatectomy for Locally Advanced Disease | Not applicable | NCT04297410 | Rabin Medical Center, Isral | ||

| 177Lu-PSMA-R2 | Active, not recruiting | 177Lu-PSMA-R2 in Patients With PSMA Positive Progressive, Metastatic, Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer (PROter) | Phase I,II | NCT03490838 | Advanced Accelerator Applications | ||

| 177Lu-EB-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | Therapeutic Efficiency and Response to 177Lu-EB-PSMA-617 in Comparison to 177Lu-PSMA-617 in Patients With mCRPC | Phase I | NCT04996602 | Peking Union Medical College Hospital, China | ||

| 177Lu-Ludotadipep | Recruiting | [177Lu]Ludotadipep Treatment in Patients With Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer | Phase I | NCT04509557 | FutureChem | ||

| 177Lu-DGUL | Recruiting | A phase 1/2 clinical trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability, dosimetry and anti-tumor activity of Ga-68-NGUL/Lu-177-DGUL in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) refractory to standard therapy | Phase I,II | KCT0006160 + | Cellbion | ||

| 177Lu-DOTA-TLX591++ | Not yet recruiting | External Beam Therapy With Theranostic Radioligand Therapy for Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer (ProstACT TARGET) | Phase II | NCT05146973 | Telix International Pty Ltd | ||

| I-131 based PSMA RLT | 131I-PSMA-1095 | Recruiting | Study of I-131–1095 Radiotherapy in Combination With Enzalutamide in Patients With Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Who Are Chemotherapy Naive and Have Progressed on Abiraterone (ARROW) | Phase II | NCT03939689 | Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Inc | |

| 131I-PSMA-1095 | Enrolling by invitation | Two TraCer PositROn EmiSSion Tomography ComBination for Efficacy EstimatiOn of Prostate Specific Membrane Antigen Radioligand Therapy in Patients With Metastatic Prostate Cancer (CROSSBOW) | Phase II | NCT04085991 | Sir Mortimer B. Davis—Jewish General Hospital, Canada | ||

| TAT† PSMA RLT | 225 Ac-PSMA-617 | Recruiting | Study of 225Ac-PSMA-617 in Men With PSMA-positive Prostate Cancer (AcTION study) | Phase I | NCT04597411 | Endocyte | |

| 225 Ac-PSMA-617 | Not yet recruiting | Clinical Trial of Ac225-PSMA Radioligand Therapy of Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer | Phase I | NCT04225910 | Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China | ||

| 225Ac-J591++ | Recruiting | Maximizing Responses to Anti-PD1 Immunotherapy With PSMA-targeted Alpha Therapy in mCRPC | Phase I,II | NCT04946370 | Weill Medical College of Cornell University, NY |

*mCRPca, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; + , Clinical Research information Service (CRIS) a registration system for clinical trials to be conducted in Korea; + + , PSMA targeting monoclonal antibodies; TAT†, targeting alpha therapy

PSMA-Directed Imaging

Current Status of PSMA Imaging

PSMA has a unique feature that forms a ligand–receptor complex with a substrate. Based on this feature, small molecules mimicking the endogenous substrate for PSMA have been developed for diagnosis and therapy after labeling with radionuclides. The basic chemical structure of these PSMA ligands incorporates glutamate-urea-glutamate or glutamate-urea-lysine dimers, which are essential structural components required for binding to the catalytic domain of PSMA [13]. PSMA was originally targeted by a monoclonal antibody (Capromab Pendetide) and then labeled with 111In (ProstaScint®) for scintigraphy imaging. However, inherent limitations of antibodies, such as slow clearance from non-targeted tissues, have hampered the use of antibodies in the clinical field. Instead, urea-based small-molecule PSMA inhibitors have been investigated as anti-PSMA-specific ligands. The first small-molecule PSMA inhibitors for the imaging of PCa introduced to the clinic were 123I-MIP-1072 and 123I-MIP-1095. In addition, the widespread use of 99mTc and SPECT scanners has led to the development of 99mTc-based PSMA radiopharmaceuticals. However, a clinical breakthrough was achieved with the development of 68Ga-based PSMA radioligands that have formed the mainstream in PSMA-directed imaging.

Among the recently developed PSMA ligands for PET imaging, the most widely and actively investigated PSMA-targeting imaging radiopharmaceuticals is 68Ga-PSMA-11. 68Ga-PSMA-11 has spread rapidly worldwide since its clinical introduction in 2011 [14]. 68Ga-PSMA-11 is the first PSMA PET agent that received FDA approval for the visualization of PSMA-positive lesions in patients with PCa in 2020. Although 68Ga-PSMA PET agents have prevailed in clinical studies, 18F-PSMA PET is preferred over 68Ga-PSMA PET for several reasons. The 18F-labeled agent presents with a higher image resolution than the 68Ga-labeled agent because of its longer half-life and shorter positron energy. Moreover, it is possible to produce 18F-labeled agents on a large scale from low-energy cyclotrons and to deliver 18F-labeled agents to local imaging centers from a central facility. Because of the limited distribution of 68Ga-PSMA-11, the FDA granted approval to the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of California, San Francisco. In contrast, 18F-DCFPyL was approved by the FDA as the first commercially available PSMA PET imaging agent in 2021.

18F-DCFPyL is indicated in patients with suspected metastasis who are candidates for initial definitive therapy or patients with suspected recurrence, based on two pivotal randomized clinical trials [15, 16]. A phase II/III multicenter trial (OSPREY study) demonstrated excellent performance of 18F-DCFPyL PET/CT for detecting nodal metastases in patients with high-risk PCa undergoing RP for determining suspected recurrent/metastatic lesions observed on conventional imaging [15]. Another prospective phase III study for the assessment of 18F-DCFPyL PET/CT in patients with BCR (CONDOR study) showed a high correct localization rate of 84.8–87.0%, which led to a change in intended management in 63.9% of evaluable patients [16].

Apart from PSMA PET agents that already acquired market authorizations, various PSMA ligands radiolabeled with positron emitters have been developed for PSMA-directed imaging, such as 68Ga-PSMA-617 [17], 68Ga-PSMA I&T [18], 64Cu-PSMA-I&T [19], 18F-PSMA-1007 [20], 18F-rhPSMA-7 [21], and 18F-Florastamin [22]. In addition to diagnostic accuracy, the focus of the development of PSMA imaging is the realization of theranosis. Not only targeting the same cellular structures and biologic process, but also similarities in the chemical structures of diagnostic and therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals are essential for the establishment of successful theranosis. In this regard, these PSMA PET radioligands can be interchangeably labeled with therapeutic radionuclides or at least share similar structures with therapeutic PSMA radioligands (Fig. 1).

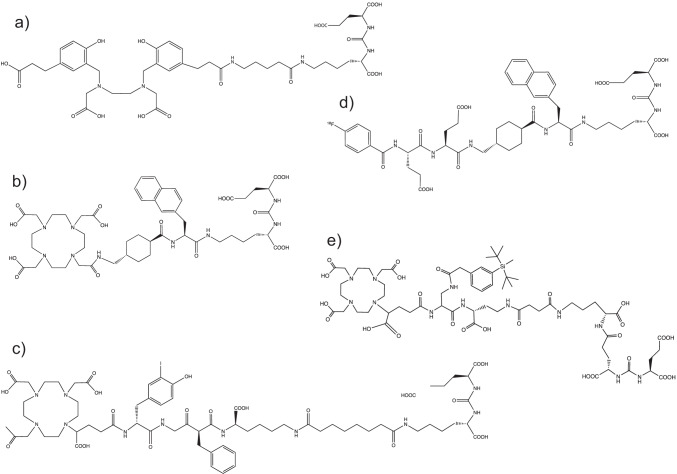

Fig. 1.

Representative radioligands targeting prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). A PSMA-11 is the most widely and actively investigated PSMA-targeting imaging radioligand, and 68 Ga-PSMA-11 received Food and Drug Administration approval for the visualization of PSMA-positive lesions in patients with prostate cancer (PCa) in 2020. B PSMA-617 is the most widely and actively investigated PSMA-targeting therapy radioligand, and many clinical trials using 177Lu-PSMA-617 have been conducted for the treatment of patients with PCa. C PSMA I&T can be radiolabeled with both diagnostic and therapeutic radionuclides; thus, the name implies imaging and therapy. D PSMA 1007 is used for PSMA-directed imaging after 18F labeling, and it is considered advantageous in theranostic applications because it shares similar structures with PSMA 617, a representative ligand for PSMA RLT. E Radiohybrid PSMA ligand is a theranostic PSMA targeting ligand that can be interchangeably labeled with 18F and radiometals

Importance of PSMA Imaging in PSMA Radioligand Therapy (RLT)

PSMA imaging is indispensable to PSMA RLT clinical trials, since PSMA PET is required to decide the eligibility of enrollment. It is crucial to determine the presence and intensity of PSMA expression to ensure therapeutic efficacy in patients with PSMA avid diseases and to avoid futile therapy in patients without PSMA-positive lesions. In addition, PSMA PET is used to evaluate the therapeutic outcomes in clinical trials using PSMA RLT.

Clinical trials using PSMA RLT followed the recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Groups (PCWG), an international working group of clinical and translational experts in PCa. As clinically relevant endpoints of clinical trials for patients with PCa, post-therapeutic changes in PSA and radiographic progression-free survival (r) have been recommended by PCWG. A PSA response was defined as ≥ 50% reduction in PSA from baseline to 12 weeks after the therapy or earlier for those who discontinued therapy by PCWG2 in 2008 [23]. Conventional imaging, including bone scan, computed tomography (CT), or whole-body magnetic resonance imaging, has been suggested as the standard imaging modality for PCa clinical trials by PCWG3 in 2016 [24]. A multicenter retrospective study reported that PSMA PET offers more accurate and reproducible identification of PCWG3 CRPCa clinical trial target populations than conventional imaging [25].

PSMA-Directed Therapy

The first PSMA-based RPT introduced in the clinical field was 131I-labeled PSMA ligands [26, 27]; however, it was replaced with 177Lu-labeled PSMA ligands. Both 131I and 177Lu primarily emit β-particles and share similar physical characteristics. 131I has a long half-life of 8.02 days, with a maximum β-particle range of 2.4 mm in soft tissues, and 177Lu has a physical half-life of 6.7 days, with a maximum range of 2.1 mm in soft tissues. However, 131I is less attractive from a radiation safety point of view owing to the high-energy γ-radiation. In contrast, 177Lu only emits low-energy γ-rays that enable post-therapeutic scans for tumor localization and dosimetry. Thus, 177Lu is favored to deliver sufficient radioactivity to cancer cells while preserving the surrounding normal tissues.

177Lu- PSMA-617 for patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (mCRPCa)

177Lu- PSMA-617 is the most actively investigated PSMA ligand for the treatment of PCa. PSMA-11 is the most widely investigated PSMA ligand for PET imaging, but it is inappropriate for RLT because of its radiochemical characteristics. Owing to the advantageous properties of RLT, many clinical trials using 177Lu-PSMA-617 have shown promising results in the treatment of PCa.

Early clinical trials have shown encouraging results in patients with CRPCa, since the first patient was treated with 177Lu-PSMA-617 in 2014. In a retrospective analysis, 68.2% of patients with mCRPCa experienced a decline in PSA value in comparison to the baseline value at 8 weeks after the second cycle of RLT with 177Lu- PSMA-617 [28]. 177Lu-PSMA-617 demonstrated favorable safety profiles and high therapeutic efficacy, with an overall PSA response rate of 45% in patients with mCRPCa in a retrospective multicenter clinical trial [29]. In two uncontrolled prospective phase II trials, patients with progressive mCRPCa after taxane-based chemotherapy and novel androgen-axis drugs (NAADs), such as abiraterone or enzalutamide, were treated with four cycles of 177Lu-PSMA-617 at a 6-week interval, and high response rates and low toxic effects were reported with a PSA response in 36% of patients [30] and 57% of patients [31], respectively. A literature review analyzing early clinical trials reported that 177Lu- PSMA-617 shows low-grade toxicities and a significant treatment response in patients with CPRCa, as the number of patients showing PSA responses ranges from 30 to 70% [32].

Recently, several phase III clinical studies have published important data on RLT with 177Lu-PSMA-617. In a phase III VISION study (NCT03511664), four cycles of 177Lu-PSMA-617 at 6-week interval plus best SOC demonstrated significant improvements in the overall survival (OS) and rPFS, compared to SOC alone in patients with progressive mCRPCa [33]. The differences in rPFS (median, 8.7 vs. 3.4 months) and in OS (median, 15.3 vs. 11.3 months) were both statistically significant, and the PSA response was higher in the 177Lu-PSMA-617 group than in the control group (46.0% vs. 7.1%).

177Lu- PSMA-617 to Earlier Treatment Lines

-

Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer Setting

The aforementioned clinical trials mainly investigated the safety and efficacy of 177Lu-PSMA-617 in patients with mCRPCa with progressive disease despite taxane-based chemotherapy and NAADs. Several clinical trials are ongoing to establish RLT with 177Lu-PSMA-617 as an earlier treatment line for PCa in various clinical settings. First, the potential clinical usefulness of 177Lu-PSMA-617 is being investigated in mCRPCa pre-taxane and metastatic hormone-sensitive PCa (mHSPCa) settings. The PSMAddition trial (NCT04720157) is an international prospective open-label, randomized phase III trial that assesses the efficacy and safety of 177Lu-PSMA-617 plus SOC versus SOC alone in patients with mHSPCa who were previously treated with an alternate ADT and not exposed to a taxane-containing regimen (taxane-naive). The PSMAfore trial (NCT04689828) is a multicenter, open-label, randomized phase III trial that compares the therapeutic efficacy of 177Lu-PSMA-617 on rPFS with a change in ADT treatment in taxane-naive patients with mCRPC who received one prior ADT. For both phase III trials, six cycles of 177Lu-PSMA-617 with 7.4 GBq of radioactivity will be provided at 6-week interval in taxane-naive patients with mHSPCa.

ADT may alter PSMA expression and radiosensitivity in PCa cells. Administration of ADT increased PSMA expression in in vitro studies and animal models [34, 35]. Short-term ADT led to a heterogeneous increase in PSMA uptake, as evaluated by 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET in nine men with treatment-naive PCa [36]. It is expected that concurrent administration of 177Lu-PSMA-617 and NAADs would be synergistic in patients with mCRPCa. In this regard, the ENZA-p trial (NCT04419402), an open label, randomized, stratified, two-arm, multicenter phase II clinical trial, is being conducted to determine the safety and therapeutic efficacy of 177Lu- PSMA-617 in combination with enzalutamide, compared with those of enzalutamide alone in patients with mCRPCa at high risk of early progression to enzalutamide alone.

-

Low-Volume Metastatic Prostate Cancer

Metastasis-directed therapy (MDT) to prevent additional metastatic spread has been suggested as an alternative therapy in patients with BCR after curative intent treatment of PCa, considering that most patients have only a few metastatic lesions at the time of detecting BCR [37]. A systematic review revealed that MDT is a promising approach to improve survival in patients with low-volume mHSPCa [38]. Asymptomatic patients with low-volume mHSPCa are increasingly seeking alternative therapies to defer from ADT-related side effects with a negative impact on quality of life (QoL) [39, 40]. However, many patients do not qualify for these treatments due to prior interventions or inappropriate tumor location despite the beneficial outcomes of MDT with EBRT or targeted surgery for low-volume HSPCa. For such patients, RLT with 177Lu-PSMA-617 could be a beneficial therapeutic option. Moreover, 177Lu-PSMA seems to be highly effective in such clinical settings because of the high tumor uptake of PSMA RLT in small lesions, such as oligometastatic PCa, according to a dosimetry study [41].

A prospective pilot study published promising results for 177Lu-PSMA-617 RLT in men with low-volume mHSPCa [42]. All patients showed altered PSA kinetics, postponed the need for ADT, and maintained QoL after two cycles of 177Lu-PSMA-617 without overt complications. In particular, there were no treatment-related grade 3–4 adverse events. This study suggests that 177Lu-PSMA is a feasible and safe treatment option for patients with low-volume mHSPCa. A multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial (BULLSEYE trial) is being conducted to evaluate 177Lu-PSMA-617 RLT as an effective treatment for low-volume HSPCa (NCT04443062). The BULLSEYE trial originally planned to use 177Lu-PSMA-I&T, and whether two cycles of RLT can prolong the rPFS and postpone ADT will be compared with the SOC [43]. Recently, the trial amended two important aspects of the study protocol. The radioligand replaced 177Lu-PSMA-I&T to 177Lu-PSMA-617 and responding patients with residual disease on the interim PSMA PET after the first two cycles are eligible to receive two additional cycles of 177Lu-PSMA-617 [44].

-

Chemotherapy-Naive mCRPCa

Docetaxel has been the first-line therapeutic agent for mCRPCa, but there are many potential challenges in the treatment of mCRPCa, such as frequent administration and the multitude of associated adverse events and resultant deterioration in QoL. Thus, there is a need for alternative therapeutic options that are effective and safe for such patients. In this regard, 177Lu-PSMA-617 has been investigated as a therapeutic option for chemotherapy-naive patients with mCRPCa.

177Lu-PSMA-617 was demonstrated to be safe and non-inferior to chemotherapy in the treatment of mCRPCa in a randomized controlled phase II non-inferiority trial [45]. The efficacy and safety of 177Lu-PSMA-617 were compared with those of docetaxel in chemotherapy-naive patients with mCRPCa. The 177Lu-PSMA-617 treated group showed better treatment outcomes and better QoL than the docetaxel-treated group. Both the PSA response rate (60% vs. 40%, p = 0.25) and rPFS rate at 60 months (30% vs. 20%, p = 0.50) were high in the 177Lu-PSMA-617 group. Compared to the docetaxel group, QoL outcomes improved significantly (p < 0.01), and treatment-emergent grade ≥ 3 adverse events occurred less frequently in the 177Lu-PSMA-617-treated group (30% vs. 50%, respectively, p = 0.20).

The immediate use of cabazitaxel in the patient with mCRPCa who had received prior docetaxel and one prior NAAD was suggested based on recent results from a multicenter, randomized, open-label, clinical trial [46]. Based on this result, a randomized, phase II study (TheraP trial, NCT 03392428) was planned to evaluate the PSA response rate and OS of 177Lu- PSMA-617 in comparison to cabazitaxel alone in patients in the post-docetaxel setting [47]. This trial randomized patients into two groups: patients treated with 177Lu- PSMA-617 every 6 weeks for up to 6 cycles or patients treated with cabazitaxel 20 mg/m2 every 3 weeks for up to 10 cycles. The 177Lu- PSMA-617 group showed a better PSA response than the cabazitaxel group (66% vs. 37%, p < 0.0001), and the 177Lu- PSMA-617 group demonstrated delayed disease progression by 31% compared with cabazitaxel. As expected, grade ≥ 3 adverse effects were more common in the cabazitaxel group than in the 177Lu- PSMA-617 group.

New Strategies for177Lu-PSMA-617

-

Combination with Immunotherapy

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have dramatically changed the treatment landscape of cancer therapeutics. Programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and its ligand programmed death-ligand 1, known as the PD-1 axis, play a major role in the negative regulation of T cell activation. Thus, neutralizing the PD-1 axis using mAbs reversed these effects and enhanced T cell cytotoxicity toward tumor cells. Among ICIs, PD-1 blockade has drawn attention in the clinical field because of its broader clinical utility than anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 treatment. However, currently available ICIs are not beneficial in most patients with PCa and have only limited success in patients with mCRPCa.

Combination strategies have been suggested to overcome the limitations of ICIs in PCa. Immunotherapy-based combination therapy is expected to efficiently mobilize the immune system against cancer, considering the complexity of immune activation and the physiological homeostatic mechanisms controlling the immune system. Ionizing irradiation not only causes direct tumor cell death but also induces indirect tumor cell death, which is related to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, tumor antigens, and other danger signals from irradiated cells. Thus, radiation may promote a large amount of tumoral neoantigens that are presented to the T lymphocytes, which makes radiation carry the potential to initiate the adaptive and innate immune responses, resulting in systemic antitumorigenic effects inside and outside of the irradiation field [48].

A phase Ib, single-arm trial is being conducted to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy and safety of 177Lu-PSMA-617 in combination with pembrolizumab in chemotherapy-naive patients with mCRPCa with progression on at least one prior NAADs (NCT03805594). A single dose of 177Lu-PSMA-617 was administered concomitantly with pembrolizumab to induce an immunogenic priming effect to improve the outcomes of pembrolizumab. In this study, 177Lu-PSMA-617 followed by pembrolizumab was well tolerated and led to durable responses in a subset of mCRPC, suggesting a possible immunogenic priming effect of RLT. Another single-arm, open-label phase Ib/II study (PSMA-lutetium Radionuclide Therapy and ImmuNotherapy in Prostate CancEr; PRINCE) is ongoing to examine the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of the combination of 177Lu-PSMA-617 and pembrolizumab in patients with mCRPCa (NCT03658447). The dosing schedule of this study was designed to evaluate the therapeutic effect of RLT therapy. Thus, 177Lu-PSMA-617 at 8.5 GBq every 6 weeks was administered with a 0.5 GBq reduction at each cycle plus pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks. According to an interim analysis of this study presented in the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress 2021, 177Lu-PSMA-617 plus pembrolizumab showed a PSA response in 73% of patients, and the rPFS rate at week 24 was 65%.

-

Combination with Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitor

The poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) enzyme family is involved in multiple DNA repair pathways; thus, PARP inhibition has durable antitumor activity in certain subsets of cancers presenting with DNA damage repair (DDR) mechanism. PARP inhibitors have been investigated in patients with mCRPCa showing certain genetic aberrations, such as deleterious BRACA. Olaparib is a PARP inhibitor approved for the treatment of germline BRACA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer and has been investigated for the treatment of mCRPCa. Olaparib showed a significantly longer rPFS (median, 7.4 months vs. 3.6 months) and longer median OS (18.5 months vs.15.1 months) in a randomized phase III trial (PROfound trial) comparing olaparib with NAADs in patients with progressive mCRPCa [49].

Synergistic effects of PARP inhibition are utilized to overcome the limitations of RLT with 177Lu-PSMA in patients with progressive mCRPCa. It is hypothesized that the combination of PARP inhibitors with ionizing radiation can increase the amount of DNA damage in cells with altered DDR pathways, because ionizing radiation generates reactive oxygen species (ROS). The interference of the DDR pathway facilitates the double-strand breaks evolving from single-strand breaks, promoting the accumulation of DNA damage and subsequent cell death, and PARP inhibitors confer cytotoxicity in response to high ROS levels [50]. Moreover, PARP inhibition modulates the inflammatory immune microenvironment of tumors and it can trigger robust local and systemic antitumor immunities. The therapeutic effects of both PARP inhibition and radiation can be maximized, considering that the effects of ionizing radiation are observed not only in tumor cells but also in the tumor microenvironment. In this regard, combination therapy of RLT with PARP inhibitors has been provided to seek synergistic effects in patients with progressive mCRPCa. A phase I dose-escalation and dose-expansion study was designed to evaluate the safety and tolerability of olaparib in combination with 177Lu-PSMA in patients with mCRPCa who had previously progressed on NADDs and had not had prior exposure to platinums. PARP inhibitors or 177Lu-PSMA will be eligible for the study (LuPARP trial, NCT03874884).

-

Combination with External Beam Radiation Therapy

The combination of RLT and EBRT has been investigated as an effective and safe tool to increase the radiation delivered to tumor cells while simultaneously saving adjacent normal cells from radiation toxicity. In addition, systemic administration of RLT is expected to improve the local control of EBRT by efficiently eradicating locally invasive cells outside the high-dose radiotherapy field and improving the overall outcome by targeting potential distant metastases. The combination of 177Lu-PSMA-617 and EBRT successfully decreased the size of PSMA-positive cerebral metastases in two patients with mCRPCa [51]. Thus, combination therapy with RLT and EBRT might function as an effective MDT to prevent additional metastatic spread.

Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) is defined as an EBRT that accurately delivers a high dose of radiation to the target. SBRT presents a logical option for MDT because accumulating evidence suggests that local MDT could defer disease progression, delay the need for systemic therapies, and spare their toxicities. In this single-institute, open-label phase I study, safety, and tolerability of 177Lu-PSMA-617 and SBRT in men with hormone-sensitive PCa were evaluated. This study is the first clinical trial to test the combination of 177Lu-PSMA-617 and SBRT in patients with PCa (NCT05079698). Researchers also aim to learn more about how the treatment affects daily life and relieve the symptoms of PCa.

-

As adjuvant or Neoadjuvant Therapy

Dosimetry studies have suggested that 177Lu-PSMA-617 has the potential to replace or augment surgery or EBRT in the first line setting for the treatment of PCa. An open-label, phase I/II non-randomized clinical trial (LuTectomy trial, NCT04430192) investigated dosimetry, safety, and potential benefits of 177Lu-PSMA-617 prior to prostatectomy [52]. Patients will receive one or two cycles of 177Lu-PSMA followed by surgery in men with high-risk localized or locoregional advanced PCa undergoing RP and pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND). The primary endpoint of the trial was to determine the radiation absorbed dose in the prostate and the involved lymph nodes. This research group also explored the potential roles of 177Lu-PSMA-617 in metastatic PCa as adjuvant therapy. An open-label, phase II randomized clinical trial (UpFrontPSMA trial, NCT04343885) compared the effectiveness of 177Lu-PSMA-617 therapy followed by docetaxel chemotherapy versus docetaxel chemotherapy alone (SOC) in patients with high-volume metastatic hormone-naive PCa (mHNPCa) [53]. Patients received two cycles of 177Lu-PSMA-617 at 6-week interval, followed by docetaxel or docetaxel alone after randomization. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with undetectable PSA (≤ 0.2 ng/L) at 12 months after the treatment commencement.

New PSMA Ligands for RLT

-

177Lu-EB-PSMA-617

EB-PSMA-617 is a small-molecule PSMA inhibitor modified from PSMA-617 by adding Evans blue (EB) moiety. 177Lu-EB-PSMA-617 has significantly higher tumor accumulation and longer intra-tumoral residence time due to the albumin binding motif, which leads to significantly higher absorbed doses in bone metastasis compared to 177Lu-PSMA-617. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that a single, low dose of 177Lu-EB-PSMA-617 caused a significant decrease in 68Ga-PSMA-617 uptake and a better therapeutic response in an animal tumor model than 177Lu-PSMA-617 [54]. This first-in-human study demonstrated that 177Lu-EB-PSMA-617 has significantly higher tumor accumulation than 177Lu-PSMA-617 and that a single imaging dose provides some therapeutic efficacy in patients with mCRPCa [55]. This result suggests that 177Lu-EB-PSMA-617 therapy is more effective and may facilitate the reduction of dose or dosing frequency. Further investigations with increased doses and frequencies of administration are warranted. In this regard, an open-label, randomized phase I, dose escalation study is being conducted with doses of 1.11 GBq, 1.85 GBq, and 3.7 GBq of 177Lu-EB PSMA617 in patients with CRPCa (NCT03780075).

-

177Lu PSMA- I&T

A small-molecule PSMA inhibitor PSMA-I&T was named for imaging and therapy to be optimized for theranostics, and it has a similar PSMA-affinity, dosimetry, and pharmacokinetic profile as 177Lu-PSMA-617. 177Lu PSMA-I&T has been actively investigated next to 177Lu PSMA-617. Although 177Lu PSMA-I&T showed significantly higher kidney uptake than 177Lu PSMA-617 in mice, human studies have demonstrated almost identical kidney clearance kinetics of both 177Lu PSMA-I&T and 177Lu-PSMA-617 in men [56]. 177Lu PSMA-I&T showed a PSA response rate of 80% and a median OS of 13.7 months in patients with early-stage mCRPCa [57]. A multicenter, open-label, phase III trial (SPLASH, NCT04647526) evaluated the efficacy of 177Lu-PSMA-I&T versus NAADs in delaying rPFS in the second line setting after progression on the first line NAADs in patients with mCRPC. In addition, 177Lu PSMA-I&T was investigated as neoadjuvant therapy in an open-label, single-arm clinical trial (NCT04297410) to evaluate the safety and immediate oncological outcomes of RLT therapy followed by RP with PLND in patients with high-risk PCa.

-

177Lu-PSMA-R2

177Lu-PSMA-R2 is a urea-based small-molecule PSMA inhibitor that has rapid and specific uptake in animal tumor models, with rapid elimination through the urinary system. An open-label, multicenter, phase I/II trial (PROter trial, NCT03490838) assessed 177Lu-PSMA-R2 for the treatment of patients with mCRPCa who received previous systemic treatment. The study assessed the safety, tolerability, and radiation dosimetry of the treatment and further evaluated its effectiveness.

-

177Lu-labelled CTT-1403

177Lu-labelled CTT-1403 is an irreversible phosphoramidate-based PSMA inhibitor with an albumin-binding motif. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that CTT-1403 increases tumor uptake and decreases uptake in normal tissues by extending the circulation time due to the albumin motif [58]. This agent is being investigated in a first-in-human phase I dose-escalation trial. Similar to the two urea-based agents described earlier, CTT-1403 also incorporates a theranostic paradigm using a companion diagnostic, CTT-1057, after labeling with 18F for PET imaging.

-

131I-PSMA-1095

131I -PSMA-1095 is one of the first agent based on PSMA-targeted small-molecule inhibitor RLT against PCa. Radioiodine PSMA ligands showed promising results in patients with mCRPCa [26, 27]. After a single cycle of 131I-MIP-1095, the PSA response rate was 60.7% in 28 patients with a median time to PSA progression of 126 days [26], and 70.6% of the 36 patients with mCRPC presented with the PSA response, with a median PSA progression of 116 days [27]. However, only 65.2% of the patients experienced any PSA decline with a significantly higher percentage of adverse effects compared with 177Lu-based RLT, grade 3 thrombocytopenia (13%) compared to 5.9% after the first dose of iodinated RLT. A randomized, multicenter, controlled phase II study (ARROW, NCT03939689) is currently underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of 131I-MIP-1095 in combination with enzalutamide compared to enzalutamide alone in patients with mCRPCa who have progressed to abiraterone.

PSMA RLT in Korea

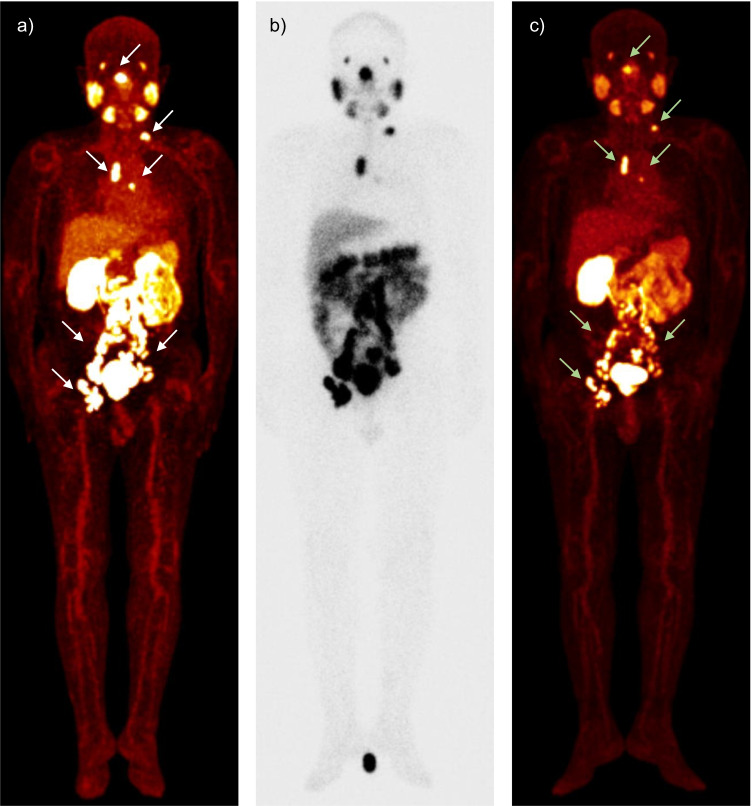

Two clinical trials using domestically developed PSMA radioligands, 177Lu-FC705 (FutureChem, Seoul, Korea) and 177Lu-DGUL (Cellbion, Seoul, Korea), are being conducted in Korea as of January 2022. 177Lu-FC705 (Ludotadipep) adopted an albumin motif to extend residential time in the circulation and simultaneously increase the tumor uptake rapidly eliminated in normal organs [59]. A phase I clinical trial aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of 177Lu-FC705 in patients with mCRPCa, with dose escalation (differentiated into five groups) applied to determine the appropriate dose (NCT04509557). 177Lu-DGUL (PSMA-DGUL) is a radioligand for PSMA-directed therapy based on Glu-Urea-Lys (GUL) derivatives [60]. 68Ga-NGUL, a counterpart for PSMA imaging radioligand to 177Lu-DGUL, exhibited similar performance in detecting PSMA-avid lesions, but showed lower uptake in normal organs, compared with 68Ga-PSMA-11 [61]. In this regard, 177Lu-DGUL is expected to be safe and effective for PSMA RLT (Figure 2). Currently, a phase I/II clinical trial is ongoing to evaluate the safety, tolerability, absorbed dose, and antitumor activity of 177Lu-DGUL in patients with mCRPCa (KCT0006160).

Fig. 2.

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) radioligand therapy in a patient with prostate cancer. A For PSMA radioligand therapy (RLT), PSMA expression was evaluated in a 69-year-old man with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer using 68 Ga-NGUL positron emission tomography (PET). The maximal intensity image (MIP) of 68 Ga-NGUL PET showed intense PSMA uptakes in multiple metastatic tumors in the lymph nodes and skull base (yellow arrows). B Matching uptake of 177Lu-DGUL was confirmed in the multiple metastatic tumors on the anterior image of post-therapeutic scintigraphy that was acquired 4 h after 5.5 GBq of 177Lu-DGUL administration. C After 2 cycles of PSMA RLT using177Lu-DGUL, the MIP of 68 Ga-NGUL PET demonstrated decreased size and PSMA expression of the metastatic tumors (green arrows)

Targeted Alpha Therapy for PSMA RLT

The radionuclides emitting alpha particles have desirable characteristics for cancer therapy, and they are best suited for the therapy of invasive tumor cells. The use of alpha-emission offers advantages over beta-emission due to the high linear energy transfer (LET) and the limited range in tissues [62]. The high LET effectively kills tumor cells through DNA double-strand and DNA cluster breaks, and the limited range allows selective tumor cell killing while sparing healthy tissues [63]. In the past few years, alpha-emitting radionuclides have been expected to enhance therapeutic effects by inducing more DNA double-strand breaks than beta-emitting radionuclides. Several alpha emitters, such as 225Ac and 213Bi, have been investigated as targeted alpha therapy (TAT) for PSMA RLT.

225 Ac-labeled PSMA

Ac-225 is an alpha emitter with a half-life of 9.92 days, which is an appropriate half-life for clinical application of RLT. TAT using 225Ac-PSMA-617 or 225Ac-PSMA-I&T has demonstrated significant benefits in patients with mCRPCa, even those who were already heavily treated, including RLT with 177Lu-PSMA-617 [64]. 225Ac-PSMA-617 shows substantial antitumor effects, which were confirmed by a significant PSA reduction and imaging responses in patients with mCRPCa [64, 65]. In a study of patients who had progressed on RLT with 177Lu-PSMA-617 under a compassionate use program in Germany, 225Ac-PSMA-617 showed a PSA response in 65% of patients and rPFS and OS of 4.1 and 7.7 months, respectively [64]. A case study reported that 225Ac-PSMA-617 achieved a complete molecular imaging response on 68Ga-PSMA PET after just one cycle of therapy and a near-complete PSA response after two cycles in a patient with PSMA-avid cerebral metastases [66]. Considering that the salivary glands and kidneys are dose-limiting organs for 177Lu-PSMA-617 by dosimetry studies, 225Ac-PSMA-617 may enhance treatment efficacy and simultaneously reduce toxicity [67]. 225Ac-PSMA-I&T also showed promising results in preclinical settings, and preliminary clinical studies showed antitumor effects, and the treatment was generally well-tolerated [68]. AcTION (NCT04597411) is a prospective open-label, international phase I trial that evaluates the safety of 225Ac-PSMA-617 in patients with mCRPCa. This study will hopefully help to address how best to minimize xerostomia while still achieving an adequate response.

213Bi-PSMA-617

Bi-213 is a mixed alpha and beta emitter with a short half-life of 45.6 min. Bi-213 has already been used for the treatment of PCa after labeling mAb J591 (213Bi-PSMA-mAB J591), which demonstrated promising therapeutic efficacy in a preclinical setting. Recently, a single case study reported the promising antitumor activity of 213Bi-PSMA-617, which was the first-in-human treatment concept in a patient with progressive mCRPCa despite conventional therapy [69]. Two cycles of 213Bi-PSMA-617 therapy showed a remarkable molecular imaging response and a PSA response (decreased from 237 to 43 μg/L). However, it is logistically challenging for therapeutic use because of the relatively short half-life of 213Bi and the inferior therapeutic index of 13Bi compared to 225Ac-PSMA-617 based on a dosimetry study [70].

Future Perspectives of PSMA RLT

Limitations of PSMA RLT

PSMA RLT based on beta-emitting nuclides presents excellent safety profiles in comparison with other treatment modalities for PCa. PSMA RLT does not affect QoL, in contrast to ADT or chemotherapy which is often related to a marked reduction in QoL. Fatigue, dry mouth, and nausea are the most common adverse events, which are nearly all of grade 1 or 2. Grade ≥ 3 adverse effects are rare. A recent meta-analysis reported that only 1% of the patients had grade 3/4 nausea and fatigue, only 2% of the patients had xerostomia, and 8% of the patients had anemia [71]. The low number of severe adverse effects among patients who received PSMA RLT may be the result of effective targeting of the cells that express PSMA.

PSMA is highly expressed in prostate epithelial cells and strongly upregulated in PCa cells, but it is also expressed in other normal organs (e.g., salivary glands, duodenal mucosa, and a subset of proximal renal tubular cells), on the contrary its name implies [72]. Normal organs that express PSMA related to off-target toxicities include the kidney, duodenum, and parotid and submandibular salivary glands [73]. Based on the biodistribution characteristics of PSMA, salivary gland toxicity is considered the main hurdle for the delivery of high-dose radioactivity. In cases of using alpha emitters (PSMA TAT), all patients experienced xerostomia, which led to treatment discontinuation in approximately a quarter of patients [64]. The application of 225Ac-PSMA-617 is unfortunately limited by severe xerostomia, which remains a dose-limiting toxicity [67], despite that clinical trials have been performed to find the best way to minimize xerostomia while achieving an adequate response. In this regard, 225Ac-PSMA-617 of 100 kBq/kg was considered the maximum tolerable dose due to xerostomia [67]. In addition, high-grade hematological toxicities, including anemia (35%), leukopenia (27%), and thrombocytopenia (19%), were observed in patients treated with PSMA TAT.

Various attempts have been investigated as a supplementary method to reduce off-target toxicities of PSMA RLT. De-escalation approach reported a less severe degree of xerostomia as 225Ac-PSMA-617 was sequentially reduced after the first cycle of the treatment with 8 MBq of 225Ac-PSMA-617 [74]. Botulinum toxin injection into the salivary glands via suppression of metabolism was successful, showing a substantial decrease of off-target uptake in a first-in-human study [75]. Blocking the salivary glands with the cold form of PSMA ligands, such as as 2-PMPA [76], PSMA-11 [77], also showed significant reductions in radioligand uptake of the salivary glands and kidneys, but the trade-off between safety and therapeutic efficacy of PSMA-targeting agents seems inevitable. Monosodium glutamate showed similar effects on PSMA radioligand uptake with cold compounds [78]. In addition, oral administration of folic acid reduced the absorbed dose to the salivary glands [79].

Enhancement of Therapeutic Effects of PSMA RLT

Although several radiopharmaceuticals targeting PSMA introduced in this review have been successfully implemented in clinics, there is still room for improvement in the therapeutic efficacy of PSMA RLT using structural modifications. Increasing the plasma protein binding of PSMA-targeting ligands can be an effective strategy to decrease the clearance rate while improving specific uptake [58]. In this regard, recently developed PSMA RLT ligands, such as EB-PSMA-617, have been adopted with an albumin motif. The attachment of albumin binders enables pharmaceuticals to bind with serum proteins, which can improve the tumor uptake of otherwise rapidly cleared molecules by expanding their circulation time. Simultaneously, an increase in off-target uptake in normal tissues seems unavoidable because of the extended circulation time. In addition, pharmacokinetic modifications of PSMA inhibitors have been investigated to accelerate excretion profiles with enhanced tumor-to-background ratios and lower radiation doses to non-target healthy tissues.

PSMA Targeting Radioimmunotherapy

Radioimmunotherapy was not addressed in this review, and it is worth discussing the potential of PSMA-targeting mAbs in the treatment of PCa. Unceasing efforts have been made to overcome the inherent limitations of antibodies, and the second-generation mAbs, such as J591, were developed to target the extracellular domains of PSMA, aiming to avoid the main burdens of intracellular targeting. Nevertheless, despite the relatively good biodistribution and pharmacokinetic profiles of J591, [177Lu]Lu-huJ591 showed significant disease remission in only 8% of patients [80]. Next, third-generation mAbs have also been developed, but they are also not free from the inherent limitations of mAb, including long circulation time and slow penetration characteristics, thereby delivering an undesired dose of radiation to healthy tissues. Based on bioengineering technology, PSMA-targeting minibodies or diabodies, even smaller nanobodies derived from huJ591, have been developed to reduce the circulation time and fast accumulation or penetration in target tissues. Although comprehensive efforts have shortened the circulation times of PSMA-targeting antibodies, undesirable characteristics, such as slow pharmacokinetic profiles, limit their application in theranostic concepts.

Expansion of Clinical Application of PSMA RLT

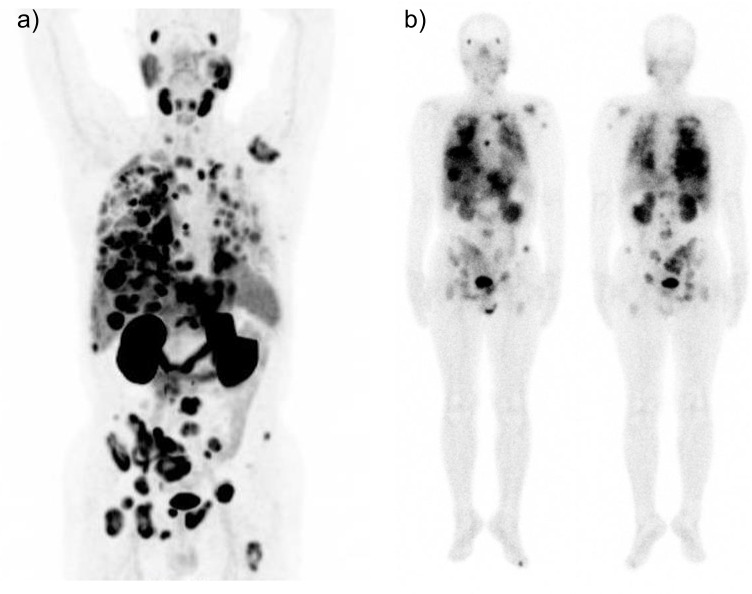

PSMA expression was also discovered in malignancies other than PCa (e.g., subtypes of transitional cell carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, colon carcinoma), and many incidental tumors presenting with high PSMA expression have been reported during PCa work-up using PSMA-directed imaging [73]. This characteristic can pave the way for the expansion of the clinical application of PSMA RLT for the treatment of non-prostate origin tumors with PSMA overexpression. However, clinical trials using PSMA RLT have yet to design or include non-prostate-origin malignancies. The “Treatment Investigational New Drug” program is prepared for such patients, which refers to permitting the use of investigational drugs or non-marketing drugs to treat patients with life-threatening diseases in Korea. This program is equivalent to the “Expanded Access Program” operated in the USA and the “Compassionate Use” in Europe. Currently, both 177Lu-FC705 and 177Lu-DGUL can be applied for the “Treatment Investigational New Drug” program, which is expected to expand the clinical applications of PSMA RLT and provide opportunities to patients with high PSMA expressing tumors. Based on the Treatment Investigational New Drug Program, a patient with metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma received PSMA RLT therapy using 177Lu-DGUL (Fig. 3) in 2021.

Fig. 3.

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) radioligand therapy in a patient with non-prostate origin malignancy. A PSMA expression was evaluated in a 55-year-old man with metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma of the left parotid gland using 68 Ga PSMA-11 positron emission tomography (PET). The maximal intensity image of 68 Ga PSMA-11 PET showed intense PSMA uptake in multiple metastatic tumors in the lungs, pleura, liver, and bones. B Uptake of 177Lu-DGUL was confirmed in the multiple metastatic tumors on the anterior and posterior images of scintigraphy that was acquired 4 h after 5.5 GBq of 177Lu-DGUL administration

Realization of Theranosis

PSMA-directed imaging and therapy are ultimately aimed at the realization of theranosis. Most clinical trials introduced in this review used imaging-based screening criteria. It is possible to image the distribution of therapeutic targets via PSMA-directed imaging. It is also possible to provide a highly favorable patient population and potentially exclude patients who may not have benefited from the PSMA-directed therapy, which is considered a precision medicine approach to RPT delivery. Accordingly, there is a growing experience regarding theranostic applications of PMSA PET in combination with PSMA RLT as a realization of theranosis.

Conclusion

PSMA-directed imaging and therapy, known as PSMA theranosis, represents a rapidly emerging strategy in the management of PCa. PSMA RLT has emerged as a promising modality for improving the management of patients with PCa. Although many challenges await PSMA RLT to be incorporated into clinical practice despite enthusiasm and scientific efforts, PSMA RLT is expected to become an SOC for PCa. In this regard, nuclear medicine has faced a golden opportunity to revive core academic identity. Thus, it is essential to enhance our understanding of PSMA theragnosis in relation to market authorization and development trends of PSMA targeting radioligands.

Author Contribution

This study was designed by So Won Oh. The first draft of the manuscript was written by So Won Oh, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. The important description was added by Gi Jeong Cheon, and Figs. 2 and 3 were made by Minseouk Suh. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing Interests

So Won Oh, Minseok Suh, and Gi Jeong Cheon declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

So Won Oh, Email: mdosw@snu.ac.kr.

Gi Jeong Cheon, Email: larrycheon@snu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Cancer C, Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:524-48. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Pfister D, Bolla M, Briganti A, Carroll P, Cozzarini C, Joniau S, et al. Early salvage radiotherapy following radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2014;65:1034–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephenson AJ, Scardino PT, Eastham JA, Bianco FJ, Jr, Dotan ZA, Fearn PA, et al. Preoperative nomogram predicting the 10-year probability of prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:715–717. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han M, Partin AW, Pound CR, Epstein JI, Walsh PC. Long-term biochemical disease-free and cancer-specific survival following anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. The 15-year Johns Hopkins experience. Urol Clin North Am. 2001;28:555–65. 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70163-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dong JT, Rinker-Schaeffer CW, Ichikawa T, Barrett JC, Isaacs JT. Prostate cancer–biology of metastasis and its clinical implications. World J Urol. 1996;14:182–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00186898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sartor O, de Bono JS. Metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1653–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1803343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghosh A, Heston WD. Tumor target prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and its regulation in prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:528–539. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans MJ, Smith-Jones PM, Wongvipat J, Navarro V, Kim S, Bander NH, et al. Noninvasive measurement of androgen receptor signaling with a positron-emitting radiopharmaceutical that targets prostate-specific membrane antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9578–9582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106383108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross JS, Sheehan CE, Fisher HA, Kaufman RP, Jr, Kaur P, Gray K, et al. Correlation of primary tumor prostate-specific membrane antigen expression with disease recurrence in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6357–6362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vlachostergios PJ, Niaz MJ, Sun M, Mosallaie SA, Thomas C, Christos PJ, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen uptake and survival in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:630589. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.630589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hupe MC, Philippi C, Roth D, Kumpers C, Ribbat-Idel J, Becker F, et al. Expression of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) on biopsies is an independent risk stratifier of prostate cancer patients at time of initial diagnosis. Front Oncol. 2018;8:623. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minner S, Wittmer C, Graefen M, Salomon G, Steuber T, Haese A, et al. High level PSMA expression is associated with early PSA recurrence in surgically treated prostate cancer. Prostate. 2011;71:281–288. doi: 10.1002/pros.21241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Afshar-Oromieh A, Avtzi E, Giesel FL, Holland-Letz T, Linhart HG, Eder M, et al. The diagnostic value of PET/CT imaging with the (68)Ga-labelled PSMA ligand HBED-CC in the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:197–209. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2949-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afshar-Oromieh A, Zechmann CM, Malcher A, Eder M, Eisenhut M, Linhart HG, et al. Comparison of PET imaging with a (68)Ga-labelled PSMA ligand and (18)F-choline-based PET/CT for the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2525-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pienta KJ, Gorin MA, Rowe SP, Carroll PR, Pouliot F, Probst S, et al. A phase 2/3 prospective multicenter study of the diagnostic accuracy of prostate specific membrane antigen PET/CT with (18)F-DCFPyL in prostate cancer patients (OSPREY) J Urol. 2021;206:52–61. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris MJ, Rowe SP, Gorin MA, Saperstein L, Pouliot F, Josephson D, et al. Diagnostic performance of (18)F-DCFPyL-PET/CT in men with biochemically recurrent prostate cancer: results from the CONDOR phase III, multicenter study. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:3674–3682. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu C, Liu T, Zhang N, Liu Y, Li N, Du P, et al. (68)Ga-PSMA-617 PET/CT: a promising new technique for predicting risk stratification and metastatic risk of prostate cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:1852–1861. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-4037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weineisen M, Schottelius M, Simecek J, Baum RP, Yildiz A, Beykan S, et al. 68Ga- and 177Lu-labeled PSMA I&T: optimization of a PSMA-targeted theranostic concept and first proof-of-concept human studies. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1169–1176. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.158550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CH, Lim I, Woo SK, Kim KI, Lee KC, Song K, et al. The feasibility of (64)Cu-PSMA I&T PET for prostate cancer. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2021 doi: 10.1089/cbr.2020.4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giesel FL, Hadaschik B, Cardinale J, Radtke J, Vinsensia M, Lehnert W, et al. F-18 labelled PSMA-1007: biodistribution, radiation dosimetry and histopathological validation of tumor lesions in prostate cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:678–688. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3573-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh SW, Wurzer A, Teoh EJ, Oh S, Langbein T, Kronke M, et al. Quantitative and qualitative analyses of biodistribution and PET image quality of a novel radiohybrid PSMA, (18)F-rhPSMA-7, in Patients with Prostate Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:702–709. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.119.234609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee I, Lim I, Byun BH, Kim BI, Choi CW, Woo SK, et al. A microdose clinical trial to evaluate [(18)F]Florastamin as a positron emission tomography imaging agent in patients with prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:95–102. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04883-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I, Morris M, Sternberg CN, Carducci MA, et al. Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the prostate cancer clinical trials working group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1148–1159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scher HI, Morris MJ, Stadler WM, Higano C, Basch E, Fizazi K, et al. Trial design and objectives for castration-resistant prostate cancer: updated recommendations from the prostate cancer clinical trials working group 3. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1402–1418. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farolfi A, Hirmas N, Gafita A, Weber M, Barbato F, Wetter A, et al. Identification of PCWG3 target populations is more accurate and reproducible with PSMA PET than with conventional imaging: a multicenter retrospective study. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:675–678. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.246603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zechmann CM, Afshar-Oromieh A, Armor T, Stubbs JB, Mier W, Hadaschik B, et al. Radiation dosimetry and first therapy results with a (124)I/ (131)I-labeled small molecule (MIP-1095) targeting PSMA for prostate cancer therapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:1280–1292. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2713-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Afshar-Oromieh A, Haberkorn U, Zechmann C, Armor T, Mier W, Spohn F, et al. Repeated PSMA-targeting radioligand therapy of metastatic prostate cancer with (131)I-MIP-1095. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:950–959. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3665-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmadzadehfar H, Eppard E, Kurpig S, Fimmers R, Yordanova A, Schlenkhoff CD, et al. Therapeutic response and side effects of repeated radioligand therapy with 177Lu-PSMA-DKFZ-617 of castrate-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:12477–12488. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahbar K, Ahmadzadehfar H, Kratochwil C, Haberkorn U, Schafers M, Essler M, et al. German multicenter study investigating 177Lu-PSMA-617 radioligand therapy in advanced prostate cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:85–90. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.183194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emmett L, Crumbaker M, Ho B, Willowson K, Eu P, Ratnayake L, et al. Results of a prospective phase 2 pilot trial of (177)Lu-PSMA-617 therapy for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer including imaging predictors of treatment response and patterns of progression. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2019;17:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hofman MS, Violet J, Hicks RJ, Ferdinandus J, Thang SP, Akhurst T, et al. [(177)Lu]-PSMA-617 radionuclide treatment in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (LuPSMA trial): a single-centre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:825–833. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emmett L, Willowson K, Violet J, Shin J, Blanksby A, Lee J. Lutetium (177) PSMA radionuclide therapy for men with prostate cancer: a review of the current literature and discussion of practical aspects of therapy. J Med Radiat Sci. 2017;64:52–60. doi: 10.1002/jmrs.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sartor O, de Bono J, Chi KN, Fizazi K, Herrmann K, Rahbar K, et al. Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1091–1103. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright GL, Jr, Grob BM, Haley C, Grossman K, Newhall K, Petrylak D, et al. Upregulation of prostate-specific membrane antigen after androgen-deprivation therapy. Urology. 1996;48:326–334. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hope TA, Truillet C, Ehman EC, Afshar-Oromieh A, Aggarwal R, Ryan CJ, et al. 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET imaging of response to androgen receptor inhibition: first human experience. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:81–84. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.181800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ettala O, Malaspina S, Tuokkola T, Luoto P, Loyttyniemi E, Bostrom PJ, et al. Prospective study on the effect of short-term androgen deprivation therapy on PSMA uptake evaluated with (68)Ga-PSMA-11 PET/MRI in men with treatment-naive prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:665–673. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04635-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Bruycker A, Lambert B, Claeys T, Delrue L, Mbah C, De Meerleer G, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of low-volume, oligorecurrent, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer amenable to lesion ablative therapy. BJU Int. 2017;120:815–821. doi: 10.1111/bju.13938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ost P, Bossi A, Decaestecker K, De Meerleer G, Giannarini G, Karnes RJ, et al. Metastasis-directed therapy of regional and distant recurrences after curative treatment of prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2015;67:852–863. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ost P, Reynders D, Decaestecker K, Fonteyne V, Lumen N, De Bruycker A, et al. Surveillance or metastasis-directed therapy for oligometastatic prostate cancer recurrence: a prospective, randomized, multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:446–453. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.4853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siva S, Bressel M, Murphy DG, Shaw M, Chander S, Violet J, et al. Stereotactic abative body radiotherapy (SABR) for oligometastatic prostate cancer: a prospective clinical trial. Eur Urol. 2018;74:455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peters SMB, Prive BM, de Bakker M, de Lange F, Jentzen W, Eek A, et al. Intra-therapeutic dosimetry of [(177)Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 in low-volume hormone-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer patients and correlation with treatment outcome. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05471-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prive BM, Peters SMB, Muselaers CHJ, van Oort IM, Janssen MJR, Sedelaar JPM, et al. Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 in low-volume hormone-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer: a prospective pilot study. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:3595–3601. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prive BM, Janssen MJR, van Oort IM, Muselaers CHJ, Jonker MA, de Groot M, et al. Lutetium-177-PSMA-I&T as metastases directed therapy in oligometastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer, a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:884. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07386-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prive BM, Janssen MJR, van Oort IM, Muselaers CHJ, Jonker MA, van Gemert WA, et al. Update to a randomized controlled trial of lutetium-177-PSMA in Oligo-metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: the BULLSEYE trial. Trials. 2021;22:768. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05733-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Satapathy S, Mittal BR, Sood A, Das CK, Mavuduru RS, Goyal S, et al. (177)Lu-PSMA-617 versus docetaxel in chemotherapy-naive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomized, controlled, phase 2 non-inferiority trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05618-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Wit R, de Bono J, Sternberg CN, Fizazi K, Tombal B, Wulfing C, et al. Cabazitaxel versus abiraterone or enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2506–2518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hofman MS, Emmett L, Sandhu S, Iravani A, Joshua AM, Goh JC, et al. [(177)Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 versus cabazitaxel in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TheraP): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:797–804. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaminski JM, Shinohara E, Summers JB, Niermann KJ, Morimoto A, Brousal J. The controversial abscopal effect. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, Saad F, Shore N, Sandhu S, et al. Olaparib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2091–2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Q, Gheorghiu L, Drumm M, Clayman R, Eidelman A, Wszolek MF, et al. PARP-1 inhibition with or without ionizing radiation confers reactive oxygen species-mediated cytotoxicity preferentially to cancer cells with mutant TP53. Oncogene. 2018;37:2793–2805. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0130-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei X, Schlenkhoff C, Schwarz B, Essler M, Ahmadzadehfar H. Combination of 177Lu-PSMA-617 and external radiotherapy for the treatment of cerebral metastases in patients with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2017;42:704–706. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000001763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dhiantravan N, Violet J, Eapen R, Alghazo O, Scalzo M, Jackson P, et al. Clinical trial protocol for LuTectomy: a single-arm study of the dosimetry, safety, and potential benefit of (177)Lu-PSMA-617 prior to prostatectomy. Eur Urol Focus. 2021;7:234–237. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2020.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dhiantravan N, Emmett L, Joshua AM, Pattison DA, Francis RJ, Williams S, et al. UpFrontPSMA: a randomized phase 2 study of sequential (177) Lu-PSMA-617 and docetaxel vs docetaxel in metastatic hormone-naive prostate cancer (clinical trial protocol) BJU Int. 2021;128:331–342. doi: 10.1111/bju.15384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Z, Tian R, Niu G, Ma Y, Lang L, Szajek LP, et al. Single low-dose injection of Evans blue modified PSMA-617 radioligand therapy eliminates prostate-specific membrane antigen positive tumors. Bioconjug Chem. 2018;29:3213–3221. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zang J, Fan X, Wang H, Liu Q, Wang J, Li H, et al. First-in-human study of (177)Lu-EB-PSMA-617 in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:148–158. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-4096-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kulkarni HR, Singh A, Schuchardt C, Niepsch K, Sayeg M, Leshch Y, et al. PSMA-based radioligand therapy for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: the Bad Berka experience since 2013. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:97S–104S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.170167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baum RP, Kulkarni HR, Schuchardt C, Singh A, Wirtz M, Wiessalla S, et al. 177Lu-Labeled prostate-specific membrane antigen radioligand therapy of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: safety and efficacy. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1006–1013. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.168443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choy CJ, Ling X, Geruntho JJ, Beyer SK, Latoche JD, Langton-Webster B, et al. (177)Lu-labeled phosphoramidate-based PSMA inhibitors: the effect of an albumin binder on biodistribution and therapeutic efficacy in prostate tumor-bearing mice. Theranostics. 2017;7:1928–1939. doi: 10.7150/thno.18719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee BS, Kim MH, Chu SY, Jung WJ, Jeong HJ, Lee K, et al. Improving theranostic gallium-68/lutetium-177-labeled psma inhibitors with an albumin binder for prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2021;20:2410–2419. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moon SH, Hong MK, Kim YJ, Lee YS, Lee DS, Chung JK, et al. Development of a Ga-68 labeled PET tracer with short linker for prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) targeting. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018;26:2501–2507. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suh M, Im HJ, Ryoo HG, Kang KW, Jeong JM, Prakash S, et al. Head-to-Head Comparison of (68)Ga-NOTA ((68)Ga-NGUL) and (68)Ga-PSMA-11 in patients with metastatic prostate cancer: a prospective study. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:1457–1460. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.258434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scheinberg DA, McDevitt MR. Actinium-225 in targeted alpha-particle therapeutic applications. Curr Radiopharm. 2011;4:306–320. doi: 10.2174/1874471011104040306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sgouros G. Alpha-particles for targeted therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1402–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feuerecker B, Tauber R, Knorr K, Heck M, Beheshti A, Seidl C, et al. Activity and adverse events of actinium-225-PSMA-617 in advanced metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer after failure of lutetium-177-PSMA. Eur Urol. 2021;79:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kratochwil C, Bruchertseifer F, Rathke H, Hohenfellner M, Giesel FL, Haberkorn U, et al. targeted alpha-therapy of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with (225)Ac-PSMA-617: swimmer-plot analysis suggests efficacy regarding duration of tumor control. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:795–802. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.203539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sathekge MM, Bruchertseifer F, Lawal IO, Vorster M, Knoesen O, Lengana T, et al. Treatment of brain metastases of castration-resistant prostate cancer with (225)Ac-PSMA-617. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:1756–1757. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04354-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kratochwil C, Bruchertseifer F, Rathke H, Bronzel M, Apostolidis C, Weichert W, et al. Targeted alpha-therapy of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with (225)Ac-PSMA-617: dosimetry estimate and empiric dose finding. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:1624–1631. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.191395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zacherl MJ, Gildehaus FJ, Mittlmeier L, Boning G, Gosewisch A, Wenter V, et al. First clinical results for PSMA-targeted alpha-therapy using (225)Ac-PSMA-I&T in advanced-mCRPC patients. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:669–674. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.251017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sathekge M, Knoesen O, Meckel M, Modiselle M, Vorster M, Marx S. (213)Bi-PSMA-617 targeted alpha-radionuclide therapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:1099–1100. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3657-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kratochwil C, Schmidt K, Afshar-Oromieh A, Bruchertseifer F, Rathke H, Morgenstern A, et al. Targeted alpha therapy of mCRPC: dosimetry estimate of (213)Bismuth-PSMA-617. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:31–37. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3817-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sadaghiani MS, Sheikhbahaei S, Werner RA, Pienta KJ, Pomper MG, Solnes LB, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and toxicities of lutetium-177-labeled prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeted radioligand therapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2021;80:82–94. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chang SS. Overview of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Rev Urol. 2004;6(Suppl 10):S13–S18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sheikhbahaei S, Afshar-Oromieh A, Eiber M, Solnes LB, Javadi MS, Ross AE, et al. Pearls and pitfalls in clinical interpretation of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-targeted PET imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:2117–2136. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3780-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sathekge M, Bruchertseifer F, Vorster M, Lawal IO, Knoesen O, Mahapane J, et al. Predictors of overall and disease-free survival in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients receiving (225)Ac-PSMA-617 radioligand therapy. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:62–69. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.119.229229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baum RP, Langbein T, Singh A, Shahinfar M, Schuchardt C, Volk GF, et al. Injection of botulinum toxin for preventing salivary gland toxicity after PSMA radioligand therapy: an empirical proof of a promising concept. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;52:80–81. doi: 10.1007/s13139-017-0508-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kratochwil C, Giesel FL, Leotta K, Eder M, Hoppe-Tich T, Youssoufian H, et al. PMPA for nephroprotection in PSMA-targeted radionuclide therapy of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:293–298. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.147181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kalidindi TM, Lee SG, Jou K, Chakraborty G, Skafida M, Tagawa ST, et al. A simple strategy to reduce the salivary gland and kidney uptake of PSMA-targeting small molecule radiopharmaceuticals. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:2642–2651. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05150-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]