Abstract

Background:

The repair of large bone defects remains a significant challenge in clinical practice and requires bone grafts or substitute materials. In this study, we developed a unique hybrid bone scaffold comprising a three dimensional (3D)-printed metal plate for weight bearing and a biodegradable polymer tube serving as bone conduit. We assessed the long-term effect of the hybrid bone scaffold in repairing radial bone defects in a beagle model.

Methods:

Bone defects were created surgically on the radial bone of three beagle dogs and individually-tailored scaffolds were used for reconstruction with or without injection of autologous bone and decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM). The repaired tissue was evaluated by X-ray, micro-computed tomography, and histological observation 6 months after surgery. The functional integrity of hybrid bone scaffold-mediated reconstructions was assessed by gait analysis.

Results:

In vivo analysis showed that the hybrid bone scaffolds maintained the physical space and bone conductivity around the defect. New bone was formed adjacent to the scaffolds. Addition of autologous bone and dECM in the polymer tube improved healing by enhancing bone induction and osteoconduction. Furthermore, the beagles’ gait appeared normal by 4 months.

Conclusion:

The future of bone healing and regeneration is closely related to advances in tissue engineering. Bone production using autologous bone and dECM loaded on 3D-printed hybrid bone scaffolds can successfully induce osteogenesis and provide mechanical force for functional bone regeneration, even in large bone defects.

Keywords: Bone regeneration, Bone abnormalities, Tissue engineering, Tissue scaffolds, 3D printing

Introduction

The healing of large bone defects represents a major clinical challenge. Even though bone tissue exhibits outstanding repair and intrinsic regenerative power, there are various clinical conditions, in which the size, location, and local environment of the defect prevent bone healing. Examples of large bone defects include tumor resections, trauma, congenital deformities, and segmental loss. The large volume of tissue that needs to be replaced hinders the quantity and quality of newly formed bone. Furthermore, the healing of larger defects is critically dependent on the presence of an appropriate vasculature to support regeneration and remodeling of new bone tissue.

In clinical practice, the standard treatment for large bone defects includes autogenous or allogenic bone grafts. However, this practice is associated with insufficient volume of available tissue, donor site morbidity (autogenous grafts), late biomechanical failures, and the possibility of allogenic disease transmission [1–5]. Osteoconductive bone graft substitutes and distraction osteogenesis (bone transport) have achieved great progress in treating smaller bone defects, but reconstruction of large bone defects requires new strategies that allow for both filling the bone gap and promoting vascularization and repair [6–9]. Vascularized free flaps offer an important and successful clinical solution; however, the procedure is time-consuming and often risky, with extended hospitalization and elevated costs.

Bone tissue engineering approaches may offer a solution [2, 9–12], as they regenerate the regions of bone defects by combining biodegradable scaffolds, cells, growth factors, and mechanical support [9]. Biodegradable scaffolds for the reconstruction of bone defects have been shown to be effective both in vitro and in vivo [2, 10–12]. However, achieving a gradual transition in physiological properties that allows the regenerated bone to withstand weight remains a major challenge. To address this problem, we propose an artificial scaffold that is customized to the patient using three dimensional (3D) printing technology and built in such way to allow for functional bone regeneration.

Specifically, we suggest reconstructing a large bone defect, i.e., one that is too extensive to heal spontaneously, by combining a metallic plate made of titanium alloy with a biodegradable polymer tube made of polycaprolactone (PCL) and ß-tricalcium phosphate (ß-TCP) into a hybrid bone scaffold. The metallic plate is individually customized by 3D printing to provide mechanical support and endure bilateral biomechanical stress by immobilization. In particular, it should withstand the initial weight-bearing pressure during bone reconstruction. The biodegradable polymer tube is a hollow cylinder designed and fabricated to function as a bone conduit, providing a passage for the newly forming bone. To enhance bone regeneration, the core of the polymer tube can be loaded with autologous bone particles and bone decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM).

In the present study, we developed and optimized hybrid bone scaffolds and evaluated their osteogenic potential in a beagle critical size radial defect model. We hypothesized that combining the metallic plate and biodegradable polymer tube into a customized implant via 3D printing could provide a biocompatible means for enhancing bone regeneration in large long-bone defects.

Materials and Methods

3D Printing and Fabrication of the Titanium Alloy Plate

The titanium (Ti-6Al-4 V) alloy plate was manufactured by the Research Institute of Industrial Science & Technology, Pohang, Republic of Korea. Titanium alloy powder with a particle size distribution of 15–45 μm and an average size of 34 μm was subjected to selective laser melting using a high-end metal 3D printer (ORLAS Creator RA; Anima, Pallini, Greece). The resulting metal plate was about 6 cm in length (Fig. 1). The mechanical properties of the metal scaffold were described previously [13–15].

Fig. 1.

Fabricated hybrid bone scaffold based on 3D printing. A Photograph of the porous titanium metal plate. B Photograph of the biodegradable polymer tube. C Schematic illustration of the 3D-printed scaffold tailored for bone regeneration in a beagle defect model

Fabrication of the Tubular Polymer

The biodegradable polymer tube was obtained from the Department of Health Sciences and Technology, Gachon University, Incheon, Republic of Korea. The 3D printer has 3 axis of X, Y and Z. A melted PCL polymer was extruded from the dispenser (Musashi Engineering Inc, Tokyo, Japan), which was attached on the Z-axis. A rotating rod of 9 mm diameter connected to the W stage were modulated of a rotating speed by an independent controller. The rotation speed of W stage was 1 RPM to make a tubular negative Poisson’s ratio (NPR) scaffold. As a scaffold material, PCL (MW 45,000; Corbion, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and β-TCP (310.20 g/mol; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were prepared and mixed at a 9:1 weight ratio. Mixed materials were fully melted in the printing dispenser at a temperature of 75 °C. PCL was extruded at 800Kpa as a filament through a heated metal micro-nozzle (0.20 mm). The movement of the micro-nozzle along the X, Y, and Z axis were controlled using a CNC controller. The 30-mm-long stretchable tubular scaffold with NPR (Fig. 1B) was created by extruding the gel paste onto a substrate using a 3D printing system (Geo technology, Incheon, Republic of Korea). The shape and size of the PCL/β-TCP scaffold were designed using CAD (Computer aided design) and software (Solidworks 2017; Dassault Systemes, Vẽlizy-Villacoublay, France).

Preparation of Decellularized Extracellular Matrix

Bone-derived dECM precursor (T&R Biofab Co, Ltd, Siheung, Republic of Korea) was processed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 0.5 M acetic acid was added to a desired concentration (1% for bio-scaffold coating and 3% for injection) of the sponge-form bone-derived dECM precursor. After that, 10 × minimum essential medium and resuspension buffer were mixed with the solubilized precursor at an 8:1:1 ratio, while the pH was adjusted to 6.5 ~ 7.3. The obtained dECM preparation was maintained at 4 °C until surgery, at which point dECM was applied for 1% concentration of bone dECM coating after immersing the bio-scaffold and air drying it on a clean bench.

Reconstruction of Large Segmental Bone Defects in Three Beagle Models

In strict accordance with the regulations on medical animal experiments, three beagles (24 months, about 10 kg) were assigned each to one treatment group: (1) hybrid bone scaffold only, (2) hybrid bone scaffold with autologous bone, and (3) hybrid bone scaffold with autologous bone and dECM. The beagles were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (5 mg/kg) and xylazine (1.1 mg/kg). The procedure was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Catholic University of Korea (CUMC-2021–0055-09).

The right anterior leg of the beagle was skinned and disinfected. A 15-cm-long craniomedial skin incision was made (Fig. 2A), the muscle was dissected from the diaphysis of the radius, and the vascular nerves were isolated. A 15-mm-long osteoperiosteal segmental defect (Fig. 2B) was made in the middle portion of the diaphysis using an oscillating saw (4000 Rotary Tool Kit; Dremel, Racine, WI USA).

Fig. 2.

Experimental procedure for creating a beagle radial bone defect model and implanting the hybrid bone scaffold. A The radial bone of the beagle was exposed. B A 15-mm-long bone defect was marked. C The biodegradable polymer tube was inserted between the two ends of the bone defect. D The metal plate was fixed to the bone with a screw. E The hybrid bone scaffold was implanted in the radial bone defect. F The muscle and skin were closed by suture

In all three beagles, the defects were surrounded by the prefabricated biodegradable polymer tube (Fig. 2C), while the bone was stabilized with the 3D-printed metal plate (Figs. 1C, 2D). Once the hybrid bone scaffold was implanted (Fig. 2E), the wound was sutured immediately in beagle 1 (Fig. 2F), autologous bone which was grounded previously from the resected radial bone which was grounded was injected in beagle 2, and grounded radial bone plus 100 μL dECM were injected into beagle 3 through a hole in the metal plate (Fig. 3). Finally, the fascia and skin were closed aseptically and tightly in all beagles. The defects were created and treated under the same conditions and by the same surgeons.

Fig. 3.

Experimental procedure for injecting autologous bone and dECM through the hole in the metal plate

The animals were administered cefazoline (20 mg/kg; Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical Corp., Seoul, Republic of Korea) intravenously for three days postoperatively. Immediately after surgery, an X-ray examination of the radial defect was performed and radiographs were made postoperatively at 4-week intervals.

Six months later, the three beagles were anesthetized and the treated radius was removed for analysis. Micro-computed tomography (Quantum GX micro-CT Imaging System; PerkinElmer, Hopkinton, MA, USA) was performed on the recovered radius. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the specimens (MeshLab version 2020.03; https://www.meshlab.net/) enabled the calculation of bone volume (mm3) and the bone volume/tissue volume ratio. Image segmentation and 3D modeling were performed with 3D slicer (version 4.11.0; https://www.slicer.org/) by anatomy and radiology experts. The area (mm2) and volume (mm3) of the scaffold and defect were measured using MeshLab software.

After the scan, the specimen was decalcified with 10% EDTA and soaked in paraformaldehyde. The upper, middle, and lower sections of the specimens were selected for hematoxylin and eosin stain. The sections were cut first to a thickness of 400 μm and then to 15 μm to obtain suitable tissue specimens. Histological analysis was performed by attaching a CCD camera (DMC2 Digital Microscope Camera; Polaroid Corporation, Cambridge, MA, USA) to an optical microscope (Olympus BX; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The tissue sample was imaged 12.5 times to measure the bone area ratio, and 40 times for histological evaluation.

Gait Evaluation

To evaluate the functional properties of the regenerated bone, gait was measured in the three beagles after 4 months. The dogs were graded into four categories: normal (grade 4), subtle weight-bearing lameness (grade 3), intermittent non-weight bearing lameness (grade 2), and non-weight-bearing lameness at the surgical limb (grade 1). Assessments were conducted in blinded fashion by three investigators.

Results

Hybrid Bone Scaffold Manufacturing, Implantation, and Surgical Outcome

Hybrid bone scaffolds consisting of a 3D-printed metal plate (Ti-6Al-4 V alloy) and polymer tube (PCL + 10%β-TCP) were successfully manufactured (Fig. 1) and implanted in the beagles (Figs. 2, 3). All the beagles tolerated the surgical procedure and fully recovered without significant discomfort following perioperative and postoperative analgesic care. The hybrid bone scaffolds were implanted around the individual radial bone defects without any difficulty, and no adjustment was required to prevent leakage of autologous bone and dECM.

Radiological Findings

Immediately after surgery, and every 4 weeks for a period of 6 months, X-ray images of the treated radius were taken. Radiographs showed that the 3D-printed metallic plate of the hybrid bone scaffold was well placed, with no loosening over this period of time (Fig. 4). New bone formation was seen in the bone defect area in all three beagles by 24 weeks. A smoother and more radiopaque appearance at this point indicated that mineralized tissue had formed around the hybrid scaffolds as well as along the adjacent host bone. A more complete shadow denoting new bone formation, fully connecting the two ends of the defect, was observed in the beagle given autologous bone and dECM compared to the animals treated with scaffold only or scaffold with autologous bone (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

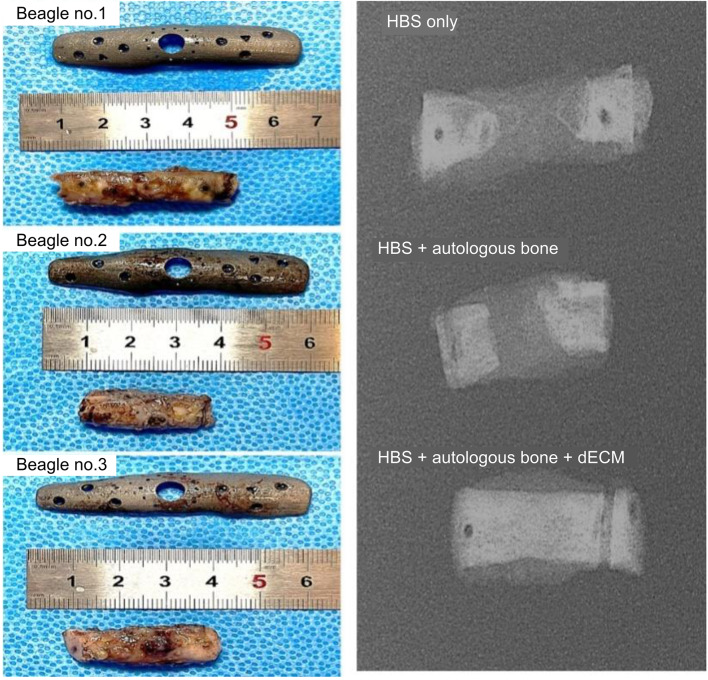

Serial X-ray images at 1 week, 8 weeks, and 24 weeks after surgery in the three beagle models: hybrid bone scaffold (HBS) alone, HBS with autologous bone, and HBS with autologous bone and dECM

Fig. 5.

Photographs of individual customized 3D-printed metal plates and gross bone specimens (left column) and radiographic images of the corresponding gross bone specimens (right column) in the three beagle models: hybrid bone scaffold (HBS) alone, HBS with autologous bone, and HBS with autologous bone and dECM

3D Micro-Computed Tomography Analysis

Harvested specimens were scanned by micro-computed tomography, and then analyzed and reconstructed in 3D with computer software based on 2D cross-sections through the center of the defects. New bone formation was observed in all three beagles, but it was more complete in the beagle treated with hybrid bone scaffold together with autologous bone and dECM. In this animal, the two ends of the radius defect were clearly connected; whereas in beagles treated with hybrid bone scaffold only or scaffold and autologous bone, newly formed bone was present only in minor amounts at the two ends of the bone defect, which were far from being connected (Fig. 6). Based on a sagittal view, the volume of newly formed bone in the beagle treated with scaffold only was 32.76 mm3, that of the beagle implanted with scaffold and autologous bone was 136.85 mm3, and that of the beagle treated with scaffold plus autologous bone and dECM was 350.43 mm3. The corresponding bone volume/tissue volume of newly formed bone was 0.1192, 0.2525, and 0.7411. Based on these results, it was concluded that the beagle treated with hybrid bone scaffold together with autologous bone and dECM achieved faster and more extensive tissue repair.

Fig. 6.

3D-reconstructed bone regeneration in the beagle radial bone defect model. 3D micro-computed tomography images demonstrating healing of the bone defect in the three beagle models: hybrid bone scaffold (HBS) alone, HBS with autologous bone, and HBS with autologous bone and dECM. The newly formed bone tissue consisted of cortical bone-like tissue covering the outside of the scaffold and cancellous bone-like tissue filling residual porosity on the inside of the scaffold

Histological Evaluation

Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on tissue Sects. 24 weeks after reconstruction to further evaluate the bone regeneration pattern following hybrid bone scaffold implantation. Based on the upper, middle, and lower sections of three histological specimens, no adverse host response and inflammatory sign such as lymphocytic infiltration could be detected at any time-point in any of the beagles.

Newly formed bone was observed in longitudinal sections throughout the segmental defect of all groups. In the beagle with hybrid bone scaffold alone, a minor amount of new bone was formed in the middle and lower sections (Fig. 7A, Table 1). Importantly, a distinct bone tissue-like structure was detected in the upper, middle, and lower sections of beagles treated with the scaffold plus autologous bone (Fig. 7B, Table 1), as well as those treated with the scaffold together with autologous bone and dECM (Fig. 7C, Table 1) Therefore, the hybrid bone scaffold with autologous bone and dECM resulted in more mature newly formed bone and was more conductive to the repair of large bone defects.

Fig. 7.

Histological evaluation of regenerated bone tissue at 24 weeks after surgery. The gross bone specimen (left column) was sliced into an upper section (slide 1), middle section (slide 2), and lower section (slide 3), which were stained by hematoxylin and eosin. External continuous cortical bone-like tissue bridging the defects (blue) and internal cancellous bone like tissue filling up the porous biodegradable polymer tube (yellow) can be seen. A Beagle 1: hybrid bone scaffold (HBS) only. B Beagle 2: HBS with autologous bone. C Beagle 3: HBS with autologous bone and dECM

Table 1.

Histomorphometric analysis of bone in the segmental defects at 24 weeks after reconstruction

| Models | Total bone volume (mm3) | New bone volume (mm3) | Percentage of new bone† |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBS only | 97.17 | 10.94 | 10.98 |

| HBS + autologous bone | 94.83 | 19.85 | 20.74 |

| HBS + autologous bone + dECM | 106.09 | 50.85 | 47.71 |

dECM, decellularized extracellular matrix; HBS, hybrid bone scaffold

†Percentage of new bone was the percentage of the area of the defect space occupied new bone

Gait Evaluation

At 1 month, the dogs exhibited a lameness grade of 1 to 2 on the unstable leg. However, at 2 months, they exhibited almost normal gait, with lameness grades of 2 to 4 (Table 2). At 4 months, all three dogs were judged as exhibiting normal motion after surgery.

Table 2.

Evaluation of the animals’ gait at different time-points after reconstruction

| Grade | HBS only | HBS + autologous bone | HBS + autologous bone + dECM |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 weeks after reconstruction | |||

| Grade 4 | |||

| Grade 3 | |||

| Grade 2 | √ | √ | |

| Grade 1 | √ | ||

| 8 weeks after reconstruction | |||

| Grade 4 | √ | ||

| Grade 3 | √ | ||

| Grade 2 | √ | ||

| Grade 1 | |||

| 16 weeks after reconstruction | |||

| Grade 4 | √ | √ | √ |

| Grade 3 | |||

| Grade 2 | |||

| Grade 1 | |||

dECM, decellularized extracellular matrix; HBS, hybrid bone scaffold

Discussion

In this study, we successfully developed a new strategy for reconstructing large bone defects using a tissue-engineered hybrid bone scaffold composed of a 3D-printed titanium metal plate and biodegradable PCL/β-TCP polymer tube.

New bone formation was observed in all three beagles in both X-ray and reconstructed 3D computed tomography images. Quantitative analysis of the latter indicated that the percentage of new bone volume relative to total defect volume was 11.9% upon treatment with the hybrid bone scaffold only, 25.3% in the case of the scaffold plus autologous bone, and 74.1% in the case of the scaffold with autologous bone and dECM. Thus, addition of autologous bone and dECM facilitated bone formation. A histological assessment confirmed the presence of invading new bone tissue in the porous structure of the polymer tube and bone ingrowth along the interface of the scaffold-bone. The observed joint stability and normal gait exhibited by all dogs 4 months after surgery support the functional efficacy of hybrid bone scaffolds.

Biocompatibility, biodegradability, osteoconductivity (allowing bone cells to adhere, proliferate, and secrete extracellular matrix), osteoinductivity (inducing new bone formation), osteogenic properties (acting as mesenchymal stem cells and osteoblasts’ reservoir), and bone-like mechanical properties (enabling formation of strong attachment with surrounding bone tissue) are critical characteristics of tissue-engineered scaffolds for bone defect reconstruction [16–19]. The hybrid bone scaffold in this study was composed of two parts, a titanium metal plate and a biodegradable polymer tube, each of which contributed separately to bone defect reconstruction.

The titanium metal plate provided mechanical support and bone scaffold fixation [20–22]. To prevent fatigue stress of the bone’s epiphysis due to excessive strength, the porosity and weight of the metal plate were adjusted [23]. The mechanical properties of the metal-based porous-structured framework provided optimum replacement for the bone [24]. The major difference between a conventional metal plate and the one used in the present scaffold is the latter’s isometric design by 3D printing. The strength of the metal plate in the scaffold was adjusted to compensate for weight-bearing loading [15], providing enough mechanical support as the new bone was being formed, while avoiding the triggering of an inflammatory response toward the foreign material.

The biodegradable polymer tube offered a new means to promote osteoconductivity, whereby bone cells were allowed to adhere, proliferate, and form extracellular matrix on its surface and pores, acting as a bridge between bone defects. The 3D porous structure of the polymer tube with an osteoblast-friendly semipermeable surface likely provided a more suitable environment for bone formation. The porous structures of the polymer tube enhanced diffusion of nutrients and metabolic products, which have been shown to increase the activity of osteoblasts [25, 26]. Biocompatibility was also satisfied by the polymer tube, as the proliferating and migrating cells did not elicit an immune or severe inflammatory response.

Autologous bone and dECM injections were possible through a hole in the metal plate of the hybrid bone scaffold, which enhanced the bone healing process [27]. The combination of autologous bone and dECM in conjunction with the proposed scaffold represents a better solution for new bone formation than scaffold alone, as it further facilitates osteoinduction by potentiating the biological effects of the added biological material. However, there are limitations to the use of dECM in standard clinical treatments due to possible immune response that could result from residual cellular material [28].

In our study, every beagle was able to bear weight on the affected limb and to walk without lameness. The implanted scaffolds were consistently stable as determined by radiography and clinical signs. These findings indicate that the scaffold adequately supported the mechanical load on the affected limbs. The major advantage of this procedure is its immediate stability, which allows earlier weight bearing and limb function, with subsequent bone ingrowth into the scaffold.

In conclusion, we have successfully established a clinically relevant radial bone defect beagle model. Our results suggest that 3D-printed tissue-engineered hybrid bone scaffolds may offer a promising treatment option for patients with large bone defects. Further studies investigating the efficacy of hybrid bone scaffolds and/or addition of autologous bone grafts or other bone substitute materials are necessary to determine the most effective treatments. Even though the healing process at the scaffold-bone interface remains unknown, the present study highlights the potential of hybrid bone scaffolds for the reconstruction of large defects in weight-bearing long bones and offers a chance for an improved quality of life.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (2017M3A9E2060428).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

All animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Catholic University of Korea (CUMC-2021–0055-09).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jiang H, Cheng P, Li D, Li J, Wang J, Gao Y, et al. Novel standardized massive bone defect model in rats employing an internal eight-hole stainless steel plate for bone tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12:e2162–e2171. doi: 10.1002/term.2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancedda R, Giannoni P, Mastrogicacomo M. A tissue engineering approach to bone repair in large animal models and clinical practice. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4240–4250. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Honnami M, Choi S, Liu IL, Kamimura W, Taguchi T, Ichimura M, et al. Repair of segmental radial defects in dogs using tailor-made titanium mesh cages with plates combined with calcium phosphate granules and basic fibroblast growth factor-binding ion complex gel. J Artif Organs. 2017;20:91–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Zheng X, Huang J, Lin J, Yang D, Xu T, Chen D, et al. 3D bioprinting in orthopedics translational research. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2019;30:1172–1187. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2019.1623989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao L, Zhao J, Yu J, Zhang C. Irregular bone defect repair using tissue-engineered periosteum in a rabbit model. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2020;17:717–727. doi: 10.1007/s13770-020-00282-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Q, Thouas GA. Metallic implant biomaterials. Mater Sci Eng R Rep. 2015;87:1–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mser.2014.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeGeros RZ. Properties of osteoconductive biomaterials: calcium phopates. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;395:81–98. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200202000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goto T, Kojima T, Iijima T, Yokokura S, Kawano H, Yamamoto A, et al. Resorption of synthetic porous hydroxyapatite and replacement by newly formed bone. J Orthop Sci. 2001;6:444–447. doi: 10.1007/s007760170013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grayson WL, Martens TP, Eng GM, Radisic M, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Biomimetic approach to tissue engineering. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:665–673. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang BJ, Ryu HH, Park SS, Koyama Y, Kikuchi M, Woo HM, et al. Comparing the osteogenic potential of canine mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissues, bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, and Wharton’s jelly for treating bone defects. J Vet Sci. 2012;13:299–310. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2012.13.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akahane M, Nakamura A, Ohgushi H, Shigematsu H, Dohi Y, Takakura Y. Osteogenic matrix sheet-cell transplantation using osteoblastic cell sheet resulted in bone formation without scaffold at an ectopic site. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2008;2:196–201. doi: 10.1002/term.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long T, Zhu Z, Awad HA, Schwarz EM, Hilton MJ, Dong Y. The effect of mesenchymal stem cell sheets on structural allograft healing of critical sized femoral defects in mice. Biomaterials. 2014;35:2752–2759. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chun CK, Kim SW. The effect of heat treatment on microstructure and mechanical behaviors of laser direct energy deposited Ti-6Al-4V plate. J Weld Join. 2018;36:75–80. doi: 10.5781/JWJ.2018.36.5.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thijs L, Verhaeghe F, Craeghs T, Van Humbeek J, Kruth JP. A study of the microstructural evolution during selective laser melting of Ti-6Al-4V. Acta Mater. 2010;58:3303–3312. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2010.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi S, Kim JW, Lee S, Yoon WY, Han Y, Kim KJ, et al. Mechanical and biocompatibility properties of sintered titanium powder for mimetic 3D-printed bone scaffolds. ACS Omega. 2022;7:10340–10346. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c06974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marijanovic I, Antunovic M, Matic I, Panek M, Ivkovic A. Bioreactor-based bone tissue engineering. In: Zorzi AR, de Miranda JA, editors. Advanced techniques in bone regeneration. London: IntechOpen; 2016. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/50291 doi: 10.5772/62546.

- 17.Ng J, Spiller K, Bernhard J, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Biomimetic approaches for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2017;23:480–493. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2016.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu D, Wang Z, Wang J, Geng Y, Zhang Z, Li Y, et al. Development of a micro-tissue-mediated injectable bone tissue engineering strategy for large segmental bone defect treatment. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:331. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-1064-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim TW, Ahn WB, Kim JM, Kim JH, Kim TH, Perez RA, et al. Combined delivery of two different bioactive factors incorporated in hydroxyapatite microcarrier for bone regeneration. Tissue Eng Reg Med. 2020;17:607–24. doi: 10.1007/s13770-020-00257-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spoerke ED, Murray NG, Li H, Brinson LC, Dunand DC, Stupp SI. A bioactive titanium foam scaffold for bone repair. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:523–533. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook SD, Thomas KA, Delton JE, Volkman TK, Whitecloud TS, Key JF. Hydroxylapatite coating of porous implants improves bone ingrowth and interface attachment strength. J Biomed Mater Res. 1992;26:989–1001. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820260803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long M, Rack HJ. Titanium alloys in total joint replacement-a materials science perspective. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1621–1639. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(97)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JW, Kang KS, Lee SH, Kim JY, Lee BK, Cho DW. Bone regeneration using a microstereolithography-produced customized poly(propylene fumarate)/diethyl fumarate photopolymer 3D scaffold incorporating BMP-2 loaded PLGA microspheres. Biomaterials. 2011;32:744–752. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laval-Jeantet AM, Bergot C, Carroll R, Garcia-Schaefer F. Cortical bone senescence and mineral bone density of the humerus. Calcif Tissue Int. 1983;35:268–272. doi: 10.1007/BF02405044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salgado AJ, Coutinho OP, Reis RL. Bone tissue engineering: state of the art and future trends. Macromol Biosci. 2004;4:743–765. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200400026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Son HJ, Lee MN, Kim Y, Choi H, Jeong BC, Oh SH, et al. Bone generation following repeated administration of recombinant bone morphogenetic protein 2. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2021;18:155–164. doi: 10.1007/s13770-020-00290-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assefa F, Lim J, Kim JA, Ihn HJ, Lim S, Nam SH, et al. Secretoneurin, a neuropeptide, enhances bone regeneration in a mouse calvarial bone defect model. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2021;18:315–324. doi: 10.1007/s13770-020-00304-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim YS, Majid M, Melchiorri AJ, Mikos AG. Applications of decellularized extracellular matrix in bone and cartilage tissue engineering. Bioeng Transl Med. 2019;4:83–95. doi: 10.1002/btm2.10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]