Abstract

Salmonella is an important foodborne pathogen, and it is unable to produce the quorum sensing signaling molecules called acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs). However, it synthesizes the SdiA protein, detecting AHL molecules, also known as autoinducer-1 (AI-1), in the external environment. Exogenous AHLs can regulate specific genes related to virulence and stress response in Salmonella. Thus, interfering with quorum sensing can be a strategy to reduce virulence and help elucidate the cell-to-cell communication role in the pathogens' response to extracellular signals. This study aimed to evaluate the influence of the quorum sensing inhibitors furanone and phytol on phenotypes regulated by N-dodecanoyl homoserine lactone (C12-HSL) in Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis. The furanone C30 at 50 nM and phytol at 2 mM canceled the alterations promoted by C12-HSL on glucose consumption and the levels of free cellular thiol in Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 under anaerobic conditions. In silico analysis suggests that these compounds can bind to the SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis and accommodate in the AHL binding pocket. Thus, furanone C30 and phytol act as antagonists of AI-1 and are likely inhibitors of the quorum sensing mechanism mediated by AHL in Salmonella.

Keywords: Quorum sensing, Furanone C30, Glucose consumption, QS-inhibitor, Phytol, Thiol

Introduction

Non-typhoidal Salmonella is an important foodborne bacterial pathogen causing gastrointestinal diseases, whose complications can lead to death [1, 2]. In 2017, it was estimated that 535,000 diseases were caused by invasive non-typhoid Salmonella, leading to 77,500 deaths [3], with Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis the most commonly associated serotype [4]. The pathogen’s virulence is related to the presence of genes located in regions of the genome called Salmonella Pathogenicity Islands (SPI) [5–8], as well as the possible presence of antibiotic resistance genes [1, 9] and the ability to resist the stresses found in the host through adjustments in its metabolism [10–14]. Besides, Salmonella can perform a type of cell-to-cell communication called quorum sensing, which leads to differential gene expression, potentially affecting virulence [15–18].

In Salmonella, quorum sensing can be mediated by three autoinducers (AI) types: AI-1, AI-2, and AI-3 [19, 20]. The mechanism mediated by AI-1 is incomplete in Salmonella due to the absence of a LuxI homolog, responsible for synthesizing acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs). However, this pathogen can respond to AHLs produced by other bacteria due to the presence of SdiA protein, a LuxR homolog, which binds to these signaling molecules and regulates gene expression [15, 16, 21, 22].

Under laboratory conditions, Salmonella responds to exogenous AHL by upregulating the expression of some genes. The rck operon (resistance to complement killing) is under positive regulation by AHL in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium [15, 18, 21]. The N-dodecanoyl homoserine lactone (C12-HSL) enhanced the expression of the hilA, invA, and invF genes of SPI-1 and glgC, fliF, lpfA, and fimF genes, involved in biofilm formation in S. enterica serovar Enteritidis PT4 578 [23].

Salmonella phenotypes were also modified in the presence of AHL once N-hexanoyl homoserine lactone (C6-HSL) and N-octanoyl homoserine lactone (C8-HSL) increased the invasion of HEp-2 cells by Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 14028 [24]. The cultivation with C8-HSL increased the adhesion of S. enterica serovar Typhi ST8 in HeLa cells and biofilm formation in polystyrene [25]. In anaerobic conditions, the molecule C12-HSL also increased the formation of biofilm in Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 [23, 26]. Furthermore, the abundance of different proteins was altered in the presence of C12-HSL [27, 28]. Among these proteins, there was an increase in those related to the oxidation–reduction process, as well as an increase in the levels of free cellular thiol after 6 and 7 h of cultivation, suggesting that the cells have greater potential to resist oxidative stress in the presence of AHLs [28]. Carneiro et al. [29] showed that glucose consumption by Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 was lower after 4 and 6 h of cultivation in the presence of C12-HSL, under anaerobic conditions, without growth alterations. In addition, the levels of metabolites related to the metabolic pathways of glycerolipids, amino acids, and aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis were also altered [29].

Even though the in vitro results suggest that exogenous AHLs regulate Salmonella virulence, this has yet to be proven in host gut colonization by this pathogen. However, considering that during gut colonization, Salmonella must compete for nutrients with the commensal microbiota that already exists in that environment, the presence of AHL may play an unrevealed effect. Interestingly, 14 different AHLs in human feces were detected by Landman et al. [30], with a predominance of N-3-oxo-dodecanoyl homoserine lactone with two double bonds (3-oxo-C12:2-HSL).

Thus, given the important phenotypes regulated by AI-1 on quorum sensing in diverse pathogens, the search for anti-quorum sensing compounds has been carried out from several sources, including algae, plants, microbes, and chemical libraries. Disrupting quorum sensing signaling is called quorum quenching and constitutes a relevant anti-virulence strategy [31–39].

The first quorum sensing inhibitor discovered was furanone, a group of compounds extracted from algae that has been extensively studied as quorum quenching in various bacteria [40–44]. Furanone C30 negatively regulated phenotypes controlled by AHL, such as swarming motility, protease, pyoverdin, and chitinase production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 [41] and production of violacein by Chromobacterium violaceum ATCC 12472 [45]. A mixture of four non-brominated furanones inhibits biofilm formation by Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 in the presence of C12-HSL [22, 26].

Phytol has been explored among the quorum sensing inhibitor compounds extracted from plants. Phytol reduced biofilm formation, pyocyanin production, twitching, and flagellar motility of P. aeruginosa PAO1 [46], swarm motility, virulence gene expression, exopolysaccharide, lipase, hemolysin, prodigiosin, and protease production by Serratia marcescens PS1 [47, 48]. Based on these phenotypic changes, Pejin et al. [46] and Srinivasan et al. [47, 48] suggested that phytol inhibits quorum sensing in P. aeruginosa and S. marcescens. In Salmonella, Z-phytol showed to be a promising candidate to inhibit AI-1-mediated quorum sensing in virtual screening of 107 plant compounds analyzed using molecular docking [49]. However, in vitro tests have yet to confirm these in silico data.

Considering the importance of anti-quorum sensing compounds for inhibiting phenotypes regulated by AHLs and the previous in silico results, the present study aimed to validate, by in vitro tests, the influence of furanone C30 and phytol on metabolic phenotypes regulated by C12-HSL in Salmonella Enteritidis under anaerobic conditions.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain and preparation of culture medium

Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Enteritidis phage type 4 (PT4) 578 (GenBank: 16S ribosomal RNA gene - MF066708.1), isolated from chicken meat, was provided by Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Culture was stored at -20 °C in Luria Bertani (LB) broth (tryptone 1%, yeast extract 0.5% and NaCl 0.4%; [50]) supplemented with 20% (v/v) of sterilized glycerol.

The experiments were conducted in anaerobic Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB; Sigma-Aldrich, India), prepared under O2-free conditions with CO2 bubbling, dispensed in anaerobic bottles sealed with butyl rubber stoppers, and autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min.

Inoculum preparation

The inoculum was prepared according to Almeida et al. [26]. Before each experiment, cells were cultivated twice in 10 mL of anaerobic TSB for 24 h at 37 °C. Then, 1 mL was transferred into 10 mL of anaerobic TSB and incubated at 37 °C. After 4 h of incubation, exponentially growing cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 g at 4 °C for 10 min (Sorvall, USA) and washed with 0.85% (w/v) saline, and the pellet was resuspended in 0.85% (w/v) saline. The inoculum was standardized to 0.1 of optical density at 600 nm (OD600nm), corresponding to approximately 107 CFU/mL, using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Finland).

Preparation of compounds solutions

The N-dodecanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone (C12-HSL; PubChem CID: 11,565,426; Fluka, Switzerland) and (Z-)-4-Bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-2(5H)-furanone (Furanone C30; PubChem CID: 10,131,246; Sigma-Aldrich, Switzerland) were suspended in acetonitrile (PubChem CID: 6342; Merck, Germany) at a stock concentration of 10 mM and further diluted to a working solution of 10 µM in acetonitrile. The 3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-2-hexadecen-1-ol (Phytol; PubChem CID: 5,366,244; Sigma-Aldrich, USA), which is a mixture of isomers (E) and (Z), was dissolved in ethanol (PubChem CID: 702; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at a stock concentration of 4 M. The prepared solutions were stored at -20 °C.

Effect of furanone and phytol in Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578

The effect of 50 nM furanone C30 and 2 mM of phytol on the growth, glucose consumption, and levels of free cellular thiol of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 were evaluated in bottles containing 50 mL of anaerobic TSB supplemented with 50 nM of C12-HSL. The control experiments were performed using an equivalent volume of the solvents used i.e., acetonitrile, ethanol or acetonitrile plus ethanol, such as 0.5% (v/v) of acetonitrile (acetonitrile), 1.0% (v/v) of acetonitrile (acetonitrile 2X), 0.05% (v/v) of ethanol (ethanol) and 0.5% (v/v) of acetonitrile plus 0.05% (v/v) of ethanol (acetonitrile + ethanol). The broths were inoculated with 5 mL of the standardized inoculum, and the bottles were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h.

Growth of Salmonella

At specific times, an aliquot of 1 mL of the culture broth was removed, and the growth of Salmonella was determined by the OD600nm using a spectrophotometer.

Glucose consumption by Salmonella

Glucose consumption was assessed by quantifying residual glucose in the culture broth by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), according to Carneiro et al. [29]. After 6 and 7 h of incubation, an aliquot of 2 mL of the broth was removed, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen (N2), and stored at -80 °C until analysis. The sample was centrifuged 12,000 g at 4 °C for 10 min (Brinkmann Instruments, Germany) and filtered on cellulose nitrate membrane with 13 mm in diameter and 22 μm pore size, and 1 mL of sample was analyzed in HPLC Dionex Ultimate 3000 (Dionex Corporation, USA) coupled to a refractive index Shodex RI-101 (Dionex Corporation, USA) and maintained at 40 °C. The mobile phase contained 5 mM sulfuric acid (H2SO4; Sigma-Aldrich, USA), the flow was 0.7 mL/min, and the injection of 20 μL. The HPLC was calibrated with the standard glucose curve and prepared at a concentration of 25 mM.

Quantification of free cellular thiol in Salmonella

The cellular lysate was prepared using 10 mL of culture broth after 6 and 7 h incubation and centrifuged at 10,000 g at 4 °C for 10 min (Brinkmann Instruments, Germany). The pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 10,000 g at 4 °C for 10 min. Posteriorly, the pellet was resuspended in 500 μL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and it was kept on ice for 1 min, vortexed for 1 min, and treated with ultrasound (400 W, 20 344 kHz; Sonics & Materials Inc., USA) for 1 min. This cycle was repeated five times. Then, the lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 g at 4 °C for 15 min, and the supernatant containing the free cellular thiol was used immediately.

The quantification of free cellular thiol was performed according to Ellman [51] and Riddles et al. [52] with the modifications proposed by Almeida et al. [28]. In a 96-well plate, 5 μL of 0.4% (w/v) 5,5'-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB or Ellman's reagent; Sigma, USA) was added in buffer sodium phosphate 0.1 M pH 8.0 containing 1 mM EDTA, 250 μL of the buffer sodium phosphate and 25 μL of the standard or cell lysate, obtained as described above. The microplate was incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and the absorbance at 412 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer. The free cellular thiol was quantified by using cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate (Sigma, USA) as standard at concentrations from 0.0 to 1.5 mM. The obtained equation was as follows: absorbance = (0.9008 × concentration) + 0.0867, with R2 = 0.9987. The quantification of free cellular thiol results was normalized by OD600nm.

Statistical analyses

Experiments were carried out in three biological replicates. The values of the triplicates were used for the analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's test using the Statistical Analysis System and Genetics Software [53]. A p-value of < 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered to be statistically significant.

Molecular docking of SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 with AHL, furanone, and phytol

The molecular docking was performed according to Almeida et al. [49, 54]. In brief, the molecular docking was performed between three modeled and validated macromolecular structures of SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 (4Y13-S, 4Y15-S, and 4Y17-S) by Almeida et al. [54] and C12-HSL (PubChem CID: 11,565,426), furanone C30 (PubChem CID: 10,131,246), E-phytol (PubChem CID: 5,280,435), Z-phytol (PubChem CID: 6,430,833) and 1-octanoyl-rac-glycerol (OCL; PubChem CID: 3,033,877) obtained from the Compound Identifier of PubChem database (PubChem CID; https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) using the “Dock Ligands” tool of the CLC Drug Discovery Workbench 4.0 software (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/), with 1,000 interactions for each compound, and the conformation of the compounds was changed during the docking via rotation around flexible bonds. The generated score mimics the potential energy change when the protein and the compound come together based on hydrogen bonds, steric interactions, and metal ions. The lower scores (more negative) correspond to higher binding affinities. The five best scores for each compound were selected, allowing the inspection of the binding sites of SdiA protein with each compound [49, 54].

Results and discussion

The molecules C12-HSL, furanone C30, and phytol and their respective concentrations were selected for this study based on three premises. First, in vitro analysis showed that C12-HSL regulates several phenotypes in Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 [22, 23, 26–29]. Second, in silico analysis revealed that these compounds could dock to different macromolecular structures of the SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 with good binding affinity [49, 54]. Furanone C30 is a quorum sensing inhibitor widely used as a positive control in studies searching for compounds that inhibit cell-to-cell communication [41, 45, 55]. Phytol is a possible quorum sensing inhibitor [46–48] and has not yet been evaluated in vitro in Salmonella. Third, the metabolic phenotypes regulated by C12-HSL in Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578, such as glucose consumption and levels of free cellular thiol, were not evaluated in the presence of furanone C30 and phytol. Notably, these phenotypes in Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 were regulated by C12-HSL at 6 and 7 h incubation and not at other cultivation times [28, 29].

Growth of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 in the presence of furanone and phytol

Initially, the growth of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 in the presence of furanone C30 and phytol was evaluated to choose concentrations of these compounds that did not interfere with the kinetics of bacterial multiplication. According to Defoirdt et al. [32], the anti-quorum sensing effect of a compound must be performed in concentrations below the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), and these concentrations should not interfere with the growth kinetics of the organism.

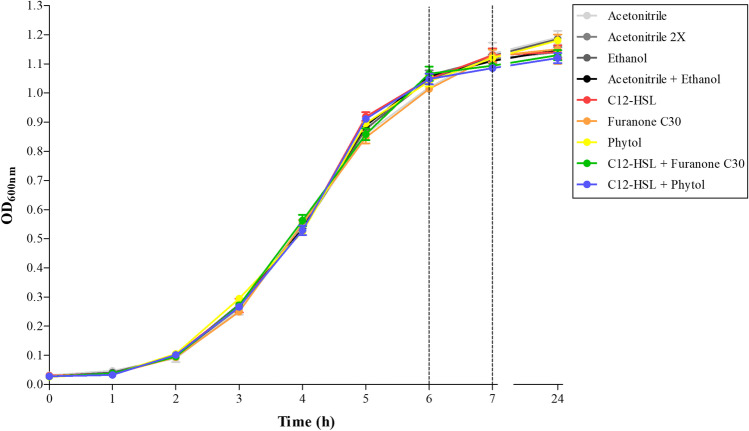

The growth of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 was not altered by 50 nM of furanone C30 or 2 mM of phytol in the presence or absence of 50 nM of C12-HSL, when compared to the controls (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1). Concentrations, even in the order of μM of furanones, have been used in other studies with no interference on the growth of Salmonella and having a quorum sensing inhibitory effect. For instance, the growth of Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 14028 at 16 °C was not influenced by adding 50, 60, and 100 μM of different brominated furanones, although biofilm formation on polystyrene was inhibited in aerobic conditions [42]. Brominated furanone F202 presented an inhibitory effect on the biofilm formation on polystyrene by Salmonella serovars Agona and Typhimurium at 37 °C without interfering with growth at concentrations up to 48 µM at 37 °C [43] and up to 50 µM at 20 °C [44]. Moreover, adding 50 nM of a mixture of four non-brominated furanones did not interfere with the growth of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions [22, 26], even though biofilm formation was inhibited. In other bacteria that naturally produce AHLs, phenotypes positively regulated by quorum sensing were negatively regulated by furanone C30 without altering growth [41, 45, 55]. For instance, the production of protease, pyoverdin, and chitinase in P. aeruginosa PAO1 was reduced by 1 or 10 µM of furanone C30 [41]. In C. violaceum ATCC 12472, adding 20 µM of furanone C30 reduced violacein production [45]. The swarming motility of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and S. marcescens MG1 also was reduced in the presence of 100 µM of furanone C30 [55].

Fig. 1.

Growth of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 in anaerobic TSB at 37 °C during 24 h, in the presence of 50 nM of C12-HSL, 50 nM of furanone C30, 2 mM of phytol, 50 nM of C12-HSL plus 50 nM of furanone C30, and 50 nM of C12-HSL plus 2 mM of phytol. The control experiments were also performed using 0.5% (v/v) of acetonitrile (acetonitrile), 1.0% (v/v) of acetonitrile (acetonitrile 2X), 0.05% (v/v) of ethanol (ethanol), and 0.5% (v/v) of acetonitrile plus 0.05% (v/v) of ethanol (acetonitrile + ethanol). The vertical dashed lines indicate the times of collection of supernatant and cells for the evaluation of the concentration of glucose in the extracellular medium and the levels of free cellular thiol, respectively. There was no statistical difference between the treatment and controls (p > 0.05). Error bars indicate standard error

The compound phytol used for this study was a mixture of the (E) and (Z) isomers and, at 2 mM, which corresponds to 593.06 µg/mL, no interference was observed in the growth of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 (Fig. 1). The MIC of phytol against Salmonella and other bacteria ranged from 2 µg/mL to 100 µg/mL [46, 56–59]. However, high concentrations of up to 1,280 μg/mL of commercially available phytol did not alter the growth of Acinetobacter baumannii MTCC 9829 and KF254610.1, even though biofilm formation was affected [60]. Phytol was considered a quorum quenching compound in P. aeruginosa PAO1. At a sub-MIC concentration of 9.5 μg/mL, it reduced phenotypes regulated by quorum sensing such as biofilm formation, production of pyocyanin, twitching, and flagella motilities [46]. Srinivasan et al. [47, 48] also showed that concentrations up to 10 μg/mL of commercially available phytol reduced biofilm formation, swarming motility, virulence gene expression, production of exopolysaccharide, lipase, hemolysin, prodigiosin, and protease by S. marcescens PS1, without interfering with growth. In general, the differences in the concentrations of furanone and phytol used by different authors are directly attributed to the test microorganism, initial inoculum, and culture conditions such as temperature, culture medium, and the presence or absence of oxygen.

In the control experiments, where acetonitrile, ethanol, and acetonitrile plus ethanol were used, the growth of Salmonella, measured as DO600nm, was not altered. A high concentration of 1% (v/v) of acetonitrile in the culture medium did not affect the growth or response of Salmonella to AHL [15]. Also, previous studies in our laboratory verified that the presence of 0.5% (v/v) of acetonitrile or 50 nM of C12-HSL in the culture medium did not interfere with the growth of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 in anaerobic TSB [22, 23, 26–29].

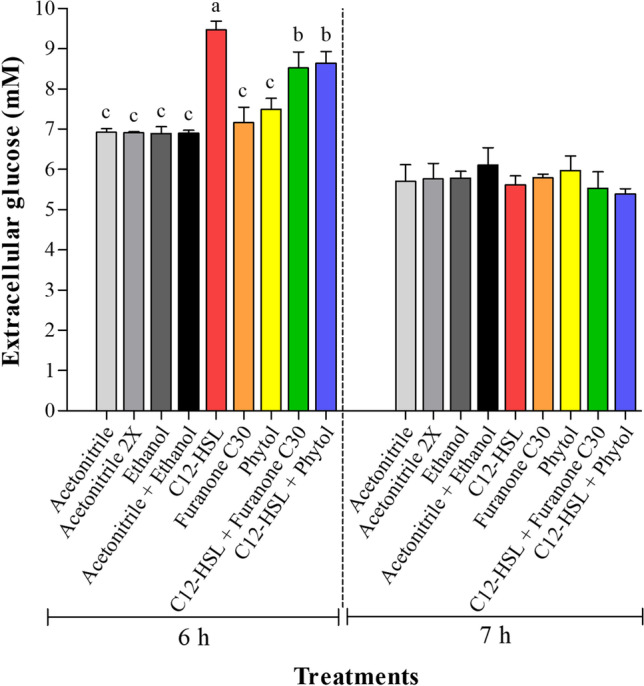

Glucose consumption of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 in the presence of furanone and phytol

The higher concentration of glucose (p < 0.05) observed in the TSB medium after 6 h of cultivation of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 in the presence of C12-HSL (Fig. 2) was also verified by Carneiro et al. [29]. According to these authors, despite the reduction in the glucose consumption by Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 cultivated in the presence of 50 nM of C12-HSL in anaerobic TSB, the numbers of log CFU/mL values were similar to the control. This result suggested that Salmonella can use alternative pathways to optimize its metabolism in the presence of quorum sensing signals. The return of glucose consumption occurred when quorum sensing inhibitors were added to the culture medium with C12-HSL but without reaching the values observed in the control treatment (Fig. 2). This behavior may indicate that furanone C30 and phytol act as AI-1 quorum sensing inhibitors.

Fig. 2.

Concentration of glucose in the extracellular medium after 6 and 7 h of cultivation of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 in anaerobic TSB at 37 °C, in the presence of 50 nM of C12-HSL, 50 nM of furanone C30, 2 mM of phytol, 50 nM of C12-HSL plus 50 nM of furanone C30, and 50 nM of C12-HSL plus 2 mM of phytol. The control experiments were also performed using 0.5% (v/v) of acetonitrile (acetonitrile), 1.0% (v/v) of acetonitrile (acetonitrile 2X), 0.05% (v/v) of ethanol (ethanol), and 0.5% (v/v) of acetonitrile plus 0.05% (v/v) of ethanol (acetonitrile + ethanol). Averages followed by different letters (between treatments at the same time) mean that there was a difference at 5% probability (p < 0.05) between them by the Tukey's test. Where the same letter or no letter is shown, no statistical difference between treatments was observed (p > 0.05). Error bars indicate standard error

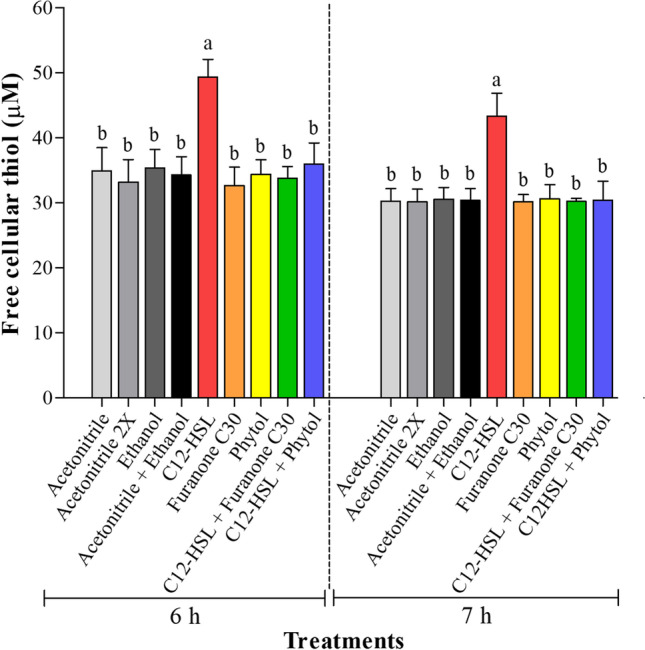

Quantification of free cellular thiol in Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 in the presence of furanone and phytol

Another phenotype associated with the presence of C12-HSL during the growth of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 in anaerobic TSB was the increase of free cellular thiol after 6 and 7 h of cultivation (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3). Besides the increased levels of free cellular thiol, the abundance of thiol proteins was higher in the presence of C12-HSL [28]. Thus, these results suggest that the cells may be prepared for possible oxidative stress since thiol, also known as mercaptan or sulfhydryl, is directly involved with the removal of reactive species, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) or reactive nitrogen species (RNS), as well as xenobiotic compounds, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [28, 61, 62]. During the invasion process, macrophages generate ROS to cause the oxidation of cellular macromolecules, such as DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids of the invader [63]. However, Salmonella can activate the production of thiol, thiol proteins, and antioxidant enzymes to escape the immune response and survive within these phagocytic cells [64, 65].

Fig. 3.

Levels of free cellular thiol after 6 and 7 h of cultivation of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 in anaerobic TSB at 37 °C in the presence of 50 nM of C12-HSL, 50 nM of furanone C30, 2 mM of phytol, 50 nM of C12-HSL plus 50 nM of furanone C30, and 50 nM of C12-HSL plus 2 mM of phytol. The control experiments were also performed using 0.5% (v/v) of acetonitrile (acetonitrile), 1.0% (v/v) of acetonitrile (acetonitrile 2X), 0.05% (v/v) of ethanol (ethanol), and 0.5% (v/v) of acetonitrile plus 0.05% (v/v) of ethanol (acetonitrile + ethanol). Averages followed by different letters (between treatments at the same time) mean that there was a difference at 5% probability (p < 0.05) between them by the Tukey's test. Where the same letter or no letter is shown, no statistical difference between treatments was observed (p > 0.05). Error bars indicate standard error

The presence of furanone C30 or phytol together with C12-HSL returns the levels of free cellular thiol to those of the controls (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3). Furanone C30 or phytol added alone to the culture medium did not alter the levels of free cellular thiol in comparison to the control treatments (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3). This decrease in free cellular thiol levels in the presence of C12-HSL plus furanone C30 or phytol shows that the addition of these two compounds alters this metabolic phenotype regulated by AHL and, consequently, reinforces the evidence that these compounds are inhibitors of quorum sensing in Salmonella.

The suppression of stress response phenotypes regulated by quorum sensing was described in P. aeruginosa PA14, and 50 µM of furanone C30 reduced the resistance to oxidative stress caused by the addition of H2O2 [66]. Other phenotypes positively regulated by AHLs in bacteria that naturally produce these molecules, such as C. violaceum, P. aeruginosa, and S. marcescens, were negatively regulated in the presence of furanone C30 [41, 45, 55] and phytol [46–48], as mentioned before.

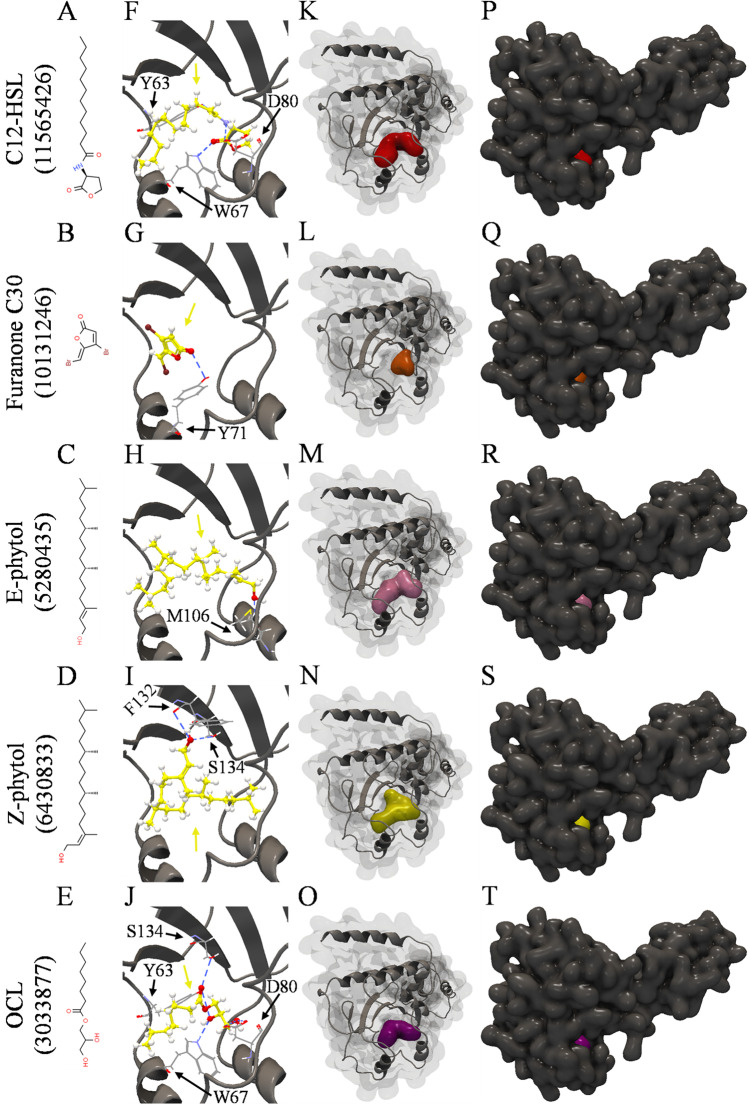

Molecular docking of SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 with AHL, furanone, and phytol

In vitro analyses showed that furanone C30 and phytol influence metabolic phenotypes such as glucose consumption and levels of free cellular thiol regulated by C12-HSL in Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578. Thus, molecular docking was performed between C12-HSL, furanone C30, E-phytol, Z-phytol, and OCL with three macromolecular structures of SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578, to compare binding sites, binding affinities through the scores, as well as the pocket accommodation of these compounds. Although Almeida et al. [49, 54] performed the molecular docking of these compounds with SdiA, they have not compared these four compounds nor performed an evaluation of their accommodation in the protein's binding pocket.

The structure of the SdiA protein of Salmonella is not available in the RCSB Protein Data Bank database (PDB; https://www.rcsb.org/). Thus, the macromolecular structures used in this study were generated by Almeida et al. [54] based on structures of the SdiA protein of Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) described by Nguyen et al. [67]. These last authors observed conformational changes of the EHEC's SdiA protein when complexed with different compounds. They named the SdiA structure of EHEC as 4Y13 when the protein was bound to OCL, 4Y15 for this protein bound to 3-oxo-C6-HSL, and 4Y17 for SdiA bound to 3-oxo-C8-HSL. Likewise, the modeled and validated macromolecular structures of SdiA of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 were named 4Y13-S, 4Y15-S, and 4Y17-S [54], and these structures were used in the current study.

The evaluated compounds showed different binding affinities with three macromolecular structures of the SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 (Table 1). These differences can be explained by the conformational changes of SdiA protein when complexed with different compounds and by the structural differences of the evaluated compounds (Figs. 4A to 4E). However, all the compounds bound in these structures and were accommodated in the binding pocket (Figs. 4K to 4T). Molecular docking studies also showed that different AHLs, furanones, and OCL [49, 54], as well as different plant compounds and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [49], presented different binding affinities for these macromolecular structures.

Table 1.

Results of molecular docking of modeled and validated macromolecular structures of SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 with C12-HSL, furanone C30, E-phytol, Z-phytol, and OCL

| Compound | PubChem CID | Modeled and validated macromolecular structures of SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4Y13-S | 4Y15-S | 4Y17-S | ||||||||||||||

| Binding residues | Hydrogen bond score | Steric interaction score | Score | Rank | Binding residues | Hydrogen bond score | Steric interaction score | Score | Rank | Binding residues | Hydrogen bond score | Steric interaction score | Score | Rank | ||

| Z-phytol 1 | 6,430,833 | Q72, Glycerol (Q72) | -6.00 | -74.66 | -71.02 | 1 | A43, F132, S134 | -6.00 | -89.53 | -84.79 | 1 | F132, S134 | -2.00 | -92.80 | -85.99 | 1 |

| C12-HSL2 | 11,565,426 | Y63, D80 | -5.90 | -69.66 | -69.00 | 2 | Y63, W67, D80, S134 | -6.65 | -85.62 | -84.70 | 2 | Y63, W67, D80 | -5.75 | -83.54 | -83.04 | 2 |

| E-phytol3 | 5,280,435 | Q72, Glycerol (Q72) | -5.07 | -71.35 | -68.60 | 3 | A43, F132, S134 | -8.00 | -87.12 | -81.91 | 3 | M106 | -0.99 | -87.00 | -82.96 | 3 |

| OCL4 | 3,033,877 | Y63, D80, Glycerol | -7.61 | -57.55 | -59.57 | 4 | Y63, W67, D80 | -6.99 | -61.70 | -61.13 | 4 | Y63, W67, D80, S134 | -7.80 | -59.09 | -65.28 | 4 |

| Furanone C305 | 10,131,246 | - | - | - | - | - | Y71 | -2.00 | -38.91 | -40.91 | 5 | Y71 | -2.00 | -40.33 | -42.33 | 5 |

1 Isomer (Z) of 3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-2-hexadecen-1-ol;

2 N-dodecanoyl-DL-homoserine lactone;

3 Isomer (E) of 3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-2-hexadecen-1-ol;

4 1-octanoyl-rac-glycerol;

5 (Z-)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-2(5H)-furanone;

No binding (-)

Fig. 4.

Molecular docking of the 4Y17-S structure of SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 with C12-HSL, furanone C30, E-phytol, Z-phytol, and OCL. (A-E) Structures of C12-HSL, furanone C30, E-phytol, Z-phytol, and OCL, (F-J) backbone representation of the 4Y17-S structure of SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 with hydrogen bonds between the amino acid residues and compounds evaluated, (K–O) surface and backbone representations and (P–T) surface representation. Gray surface representation, SdiA protein; Red surface representation, C12-HSL; Orange surface representation, furanone C30; Pink surface representation, E-phytol; Yellow surface representation, Z-phytol; Purple surface representation, OCL; Gray backbone representation, SdiA protein; Black arrow indicates the binding site; Yellow arrow, C12-HSL or furanone C30 or E-phytol or Z-phytol or OCL; Blue dashed line, hydrogen bond

The C12-HSL molecule showed a high binding affinity with all structures but presented lower scores than Z-phytol (Table 1). Almeida et al. [49, 54] also showed that AHLs with 12 carbons with or without 3-oxo modification presented greater affinities than other AHLs for SdiA macromolecular structures. In addition, C12-HSL is involved with increased virulence and resistance to cationic peptide nisin in Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 [68, 69].

The compound furanone C30 did not bind to the 4Y13-S structure. It showed the lowest binding affinity for the 4Y15-S and 4Y17-S structures, indicating that this compound binds in macromolecular structures of SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 with conformational changes caused by previous bonding with different AHLs (Table 1). When binding to the 4Y15-S and 4Y17-S structures, furanone C30 bound to Y71 residue differently from the other compounds evaluated (Table 1, Fig. 4G). Brominated furanones have a higher binding affinity for these macromolecular structures than non-brominated furanones. However, these affinities are lower than those of AHLs such as C12-HSL and phytol isoforms (E) and (Z) [49].

The compound Z-phytol showed the highest binding affinities with all evaluated structures (-71.02, -84.79, and -85.99, respectively) (Table 1). The E-phytol isomer also had a high binding affinity comparable to Z-phytol and C12-HSL (Table 1). Besides, these isomers of phytol are bound to the same amino acids in the 4Y13-S and 4Y15-S structures (Table 1). However, these molecules are bound at different amino acids in the 4Y17-S structure (Table 1, Fig. 4H and 4I) compared to the amino acids that C12-HSL bound (Table 1, Fig. 4F). Z-phytol has been suggested as a promising candidate for the in vitro quorum sensing inhibition tests and biofilm formation [49]. The E-phytol isomer showed similar and promising results as a quorum quenching compound.

The OCL, a compound found in prokaryotes and eukaryotes [70, 71], binds in the three evaluated macromolecular structures (Table 1 and Fig. 4J). Nguyen et al. [67] described OCL as a SdiA activator in EHEC independent of AHL. However, when binding to AHL, the SdiA protein showed greater stability and affinity for DNA binding [67].

Conclusion

Phenotypes recognized as regulated by C12-HSL in Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578, such as glucose consumption and production of free cellular thiol, were inhibited by 50 nM of furanone C30 or 2 mM of phytol in anaerobic TSB. Besides, these compounds could bind to the SdiA protein of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 578 and accommodate in the protein's binding pocket. Thus, we can infer that furanone C30 and phytol are inhibitors of the quorum sensing mechanism regulated by AI-1 in Salmonella. Given the important phenotypes regulated by the quorum sensing mechanism in pathogenic bacteria, which confer greater virulence and resistance to stress, the use of anti-quorum sensing compounds has been considered an important strategy for attenuation of these phenotypes. Therefore, the results presented here contribute to an advance in the understanding of cell-cell communication regulated by AI-1 in Salmonella.

Acknowledgements

Erika Lorena Giraldo Vargas was supported by a fellowship from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), and this research has also been supported by CAPES. The authors acknowledge the CLC bio of the QIAGEN Company by the license of the CLC Drug Discovery Workbench 4.0 software.

Author Contribution

Erika Lorena Giraldo Vargas was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing, and preparing the original draft. Felipe Alves de Almeida was involved in conceptualization, investigation, writing, and reviewing. Leonardo Luiz de Freitas carried out investigation. Uelinton Manoel Pinto wrote and prepared the original draft and reviewed the manuscript. Maria Cristina Dantas Vanetti participated in conceptualization, supervision, project administration, writing-reviewing, and editing.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, code 001) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not required.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors Erika Lorena Giraldo Vargas, Felipe Alves de Almeida, Leonardo Luiz de Freitas, Uelinton Manoel Pinto, and Maria Cristina Dantas Vanetti are in accordance with the submission of this manuscript to the Brazilian Journal of Microbiology.

Competing interests

None to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhao S, White DG, Friedman SL, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg isolates from retail meats, including poultry, from 2002 to 2006. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:6656–6662. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01249-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santhi LP, Sunkoji S, Siddiram S, et al. Patent research in salmonellosis prevention. Food Res Int. 2012;45:809–818. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanaway JD, Parisi A, Sarkar K, et al. The global burden of non-typhoidal Salmonella invasive disease: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:1312–1324. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30418-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balasubramanian R, Im J, Lee JS, et al. The global burden and epidemiology of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15:1421–1426. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1504717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ong SY, Ng FL, Badai SS, et al. Analysis and construction of pathogenicity island regulatory pathways in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. J Integr Bioinform. 2010;7:145. doi: 10.2390/biecoll-jib-2010-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fookes M, Schroeder GN, Langridge GC, et al. Salmonella bongori provides insights into the evolution of the Salmonellae. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002191 . doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaur J, Jain SK. Role of antigens and virulence factors of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi in its pathogenesis. Microbiol Res. 2012;167:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nieto PA, Pardo-Roa C, Salazar-Echegarai FJ, et al. New insights about excisable pathogenicity islands in Salmonella and their contribution to virulence. Microbes Infect. 2016;18:302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van TTH, Nguyen HNK, Smooker PM, et al. The antibiotic resistance characteristics of non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica isolated from food-producing animals, retail meat and humans in South East Asia. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;154:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabrega A, Vila J. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium skills to succeed in the host: virulence and regulation. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:308–341. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00066-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Runkel S, Wells HC, Rowley G. Chapter Three - Living with stress: a lesson from the enteric pathogen Salmonella enterica. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2013;83:87–144. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407678-5.00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dandekar T, Fieselmann A, Fischer E, et al. Salmonella - how a metabolic generalist adopts an intracellular lifestyle during infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015;4:191. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivera-Chávez F, Bäumler AJ. The pyromaniac inside you: Salmonella metabolism in the host gut. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2015;69:31–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrero-Fresno A, Olsen JE. Salmonella Typhimurium metabolism affects virulence in the host – A mini-review. Food Microbiol. 2018;71:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michael B, Smith JN, Swift S, et al. SdiA of Salmonella enterica is a LuxR homolog that detects mixed microbial communities. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5733–5742. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.19.5733-5742.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith JN, Ahmer BMM. Detection of other microbial species by Salmonella: expression of the SdiA regulon. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1357–1366. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.4.1357-1366.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabag-Daigle A, Soares JA, Smith JN. The acyl homoserine lactone receptor, SdiA, of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium does not respond to indole. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:5424–5431. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00046-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abed N, Grépinet O, Canepa S, et al. Direct regulation of the pefI-srgC operon encoding the Rck invasin by the quorum-sensing regulator SdiA in Salmonella Typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2014;94:254–271. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmer BMM. Cell-to-cell signalling in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:933–945. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walters M, Sperandio V. Quorum sensing in Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Int J Med Microbiol. 2006;296:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmer BMM, van Reeuwijk J, Timmers CD, et al. Salmonella Typhimurium encodes an SdiA homolog, a putative quorum sensor of the LuxR family, that regulates genes on the virulence plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1185–1193 . doi: 10.1128/JB.180.5.1185-1193.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campos-Galvão MEM, Leite TDS, Ribon AOB, et al. A new repertoire of information about the quorum sensing system in Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis PT4. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:4068–4084. doi: 10.4238/2015.April.27.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campos-Galvão MEM, Ribon AOB, Araújo EF, et al. Changes in the Salmonella enterica Enteritidis phenotypes in presence of acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing signals. J Basic Microbiol. 2016;56:493–501. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201500471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nesse LL, Berg K, Vestby LK, et al. Salmonella Typhimurium invasion of HEp-2 epithelial cells in vitro is increased by N-acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing signals. Acta Vet Scand. 2011;53:44. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-53-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Z, Que F, Liao L, et al. Study on the promotion of bacterial biofilm formation by a Salmonella conjugative plasmid and the underlying mechanism. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e109808 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Almeida FA, Pimentel-Filho NJ, Pinto UM, et al. Acyl homoserine lactone-based quorum sensing stimulates biofilm formation by Salmonella Enteritidis in anaerobic conditions. Arch Microbiol. 2017;199:475–486. doi: 10.1007/s00203-016-1313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almeida FA, Pimentel-Filho NJ, Carrijo LC, et al. Acyl homoserine lactone changes the abundance of proteins and the levels of organic acids associated with stationary phase in Salmonella Enteritidis. Microb Pathog. 2017;102:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almeida FA, Carneiro DG, Mendes TAO, et al. Vanetti, N-dodecanoyl-homoserine lactone influences the levels of thiol and proteins related to oxidation-reduction process in Salmonella. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0204673 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carneiro DG, Almeida FA, Aguilar AP, et al. Salmonella enterica optimizes metabolism after addition of acyl-homoserine lactone under anaerobic conditions. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1459. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landman C, Grill JP, Mallet JM, et al. Inter-kingdom effect on epithelial cells of the N-acyl homoserine lactone 3-oxo-C12:2, a major quorum-sensing molecule from gut microbiota. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0202587 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galloway WRJD, Hodgkinson JT, Bowden S, et al. Applications of small molecule activators and inhibitors of quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Defoirdt T, Brackman G, Coenye T. Quorum sensing inhibitors: how strong is the evidence? Trends Microbiol. 2013;21:619–624. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalia VC. Quorum sensing inhibitors: an overview. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:224–245. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quecán BXV, Rivera MLC, Pinto UM (2018) Bioactive phytochemicals targeting microbial activities mediated by quorum sensing. In: Kalia V (ed) Biotechnological applications of quorum sensing inhibitors. Springer Singapore, Singapore, pp 397–416. 10.1007/978-981-10-9026-4_19

- 35.Rémy B, Mion S, Plener L, et al. Interference in bacterial quorum sensing: a biopharmaceutical perspective. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:203. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.García-Contreras R, Wood TK, Tomás M. Editorial: quorum network (sensing/quenching) in multidrug-resistant pathogens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2019;9:80. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang Q, Chen J, Yang C, et al. Quorum sensing: a prospective therapeutic target for bacterial diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2019/2015978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalia VC, Patel SKS, Kang YC, et al. Quorum sensing inhibitors as antipathogens: biotechnological applications. Biotechnol Adv. 2019;37:68–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saeki EK, Kobayashi RKT, Nakazato G. Quorum sensing system: target to control the spread of bacterial infections. Microb Pathog. 2020;142:104068 . doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasmussen TB, Manefield M, Andersen JB, et al. How Delisea pulchra furanones affect quorum sensing and swarming motility in Serratia liquefaciens MG1. Microbiology. 2000;146:3237–3244. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-12-3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hentzer M, Wu H, Andersen JB, et al. Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by quorum sensing inhibitors. EMBO J. 2003;22:3803–3815. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janssens JCA, Steenackers H, Robijns S, et al. Brominated furanones inhibit biofilm formation by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:6639–6648. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01262-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vestby LK, Lönn-Stensrud J, Møretrø T, et al. A synthetic furanone potentiates the effect of disinfectants on Salmonella in biofilm. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;108:771–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vestby LK, Johannesen KCS, Witsø IL. Synthetic brominated furanone F202 prevents biofilm formation by potentially human pathogenic Escherichia coli O103:H2 and Salmonella ser. Agona on abiotic surfaces. J Appl Microbiol. 2014;116:258–268. doi: 10.1111/jam.12355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Z, Wang W, Zhu Y, et al. Antibiotics at subinhibitory concentrations improve the quorum sensing behavior of Chromobacterium violaceum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2013;341:37–44. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pejin B, Ciric A, Glamoclija J, et al. In vitro anti-quorum sensing activity of phytol. Nat Prod Res. 2014;29:374–377. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2014.945088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srinivasan R, Devi KR, Kannappan A, et al. Piper betle and its bioactive metabolite phytol mitigates quorum sensing mediated virulence factors and biofilm of nosocomial pathogen Serratia marcescens in vitro. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;193:592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Srinivasan R, Mohankumar R, Kannappan A, et al. Exploring the anti-quorum sensing and antibiofilm efficacy of phytol against Serratia marcescens associated acute pyelonephritis infection in Wistar rats. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:498. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Almeida FA, Vargas ELG, Carneiro DG, et al. Virtual screening of plant compounds and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for inhibition of quorum sensing and biofilm formation in Salmonella. Microb Pathog. 2018;121:369–388. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller JH. Experiments in molecular genetics. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riddles PW, Blakeley RL, Zerner B. Ellman’s reagent: 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) - a reexamination. Anal Biochem. 1979;94:75–81. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90792-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferreira DF. Sisvar: a computer statistical analysis system. Ciênc Agrotec. 2011;35:1039–1042. doi: 10.1590/S1413-70542011000600001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Almeida FA, Pinto UM, Vanetti MCD. Novel insights from molecular docking of SdiA from Salmonella Enteritidis and Escherichia coli with quorum sensing and quorum quenching molecules. Microb Pathog. 2016;99:178–190. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quecán BXV, Santos JTC, Rivera MLC, et al. Effect of quercetin rich onion extracts on bacterial quorum sensing. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:867. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rajab MS, Cantrell CL, Franzblau SG, et al. Antimycobacterial activity of (E)-phytol and derivatives: a preliminary structure-activity study. Planta Med. 1998;64:2–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Inoue Y, Hada T, Shiraishi A, et al. Biphasic effects of geranylgeraniol, teprenone, and phytol on the growth of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1770–1774. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1770-1774.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saikia D, Parihar S, Chanda D, et al. Antitubercular potential of some semisynthetic analogues of phytol. Bioorganic Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:508–512. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.11.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pejin B, Savic A, Sokovic M, et al. Further in vitro evaluation of antiradical and antimicrobial activities of phytol. Nat Prod Res. 2014;28:372–376. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2013.869692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Srinivasan R, Kannappan A, Sivasankar C, et al. Biofim inhibitory efficiency of phytol in combination with cefotaxime against nosocomial pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. J Appl Microbiol. 2018;125:56–71. doi: 10.1111/jam.13741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Forman HJ, Zhang H, Rinna A. Glutathione: overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ku JW, Gan YH. Modulation of bacterial virulence and fitness by host glutathione. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2019;47:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumawat M, Pesingi PK, Agarwal RK, et al. Contribution of protein isoaspartate methyl transferase (PIMT) in the survival of Salmonella Typhimurium under oxidative stress and virulence. Int J Med Microbiol. 2016;306:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bjur E, Eriksson-Ygberg S, Åslund F, et al. Thioredoxin 1 promotes intracellular replication and virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5140–5151. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00449-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aussel L, Zhao W, Hébrard M, et al. Salmonella detoxifying enzymes are sufficient to cope with the host oxidative burst. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:628–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.García-Contreras R, Nuñez-López L, Jasso-Chávez R, et al. Quorum sensing enhancement of the stress response promotes resistance to quorum quenching and prevents social cheating. ISME J. 2015;9:115–125. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nguyen Y, Nguyen NX, Rogers JL, et al. Structural and mechanistic roles of novel chemical ligands on the SdiA quorum-sensing transcription regulator. MBio. 2015;6:e02429–e2514. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02429-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Freitas LL, Silva FP, Fernandes KM, et al. The virulence of Salmonella Enteritidis in Galleria mellonella is improved by N-dodecanoyl-homoserine lactone. Microb Pathog. 2021;152:104730 . doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.104730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Freitas LL, Santos CIA, Carneiro DG, et al. Nisin and acid resistance in Salmonella is enhanced by N-dodecanoyl-homoserine lactone. Microb Pathog. 2020;147:104320. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alvarez HM, Steinbüchel A. Triacylglycerols in prokaryotic microorganisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;60:367–376. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Q, Siloto RMP, Lehner R, et al. Acyl-CoA: diacylglycerol acyltransferase: molecular biology, biochemistry and biotechnology. Prog Lipid Res. 2012;51:350–377. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]