Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Skeletal muscles play many important roles in the human body and any malfunction or disorder of the skeletal muscles can lead to a reduced quality of life. Some skeletal dysfunctions are acquired, such as sarcopenia but others are congenital. Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is one of the most common forms of hereditary muscular dystrophy and is caused by a deficiency of the protein, Dystrophin. Currently, there is no clear treatment for DMD, there are only methods that can alleviate the symptoms of the disease. Mesenchymal stem cells, including tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells (TMSCs) have been shown to differentiate into skeletal muscle cells (TMSC-myocyte) and can be one of the resources for the treatment of DMD. Skeletal muscle cell characteristics of TMSC-myocytes have been confirmed through changes in morphology and expression of skeletal muscle markers such as Myogenin, Myf6, and MYH families after differentiation.

MEOTHDS:

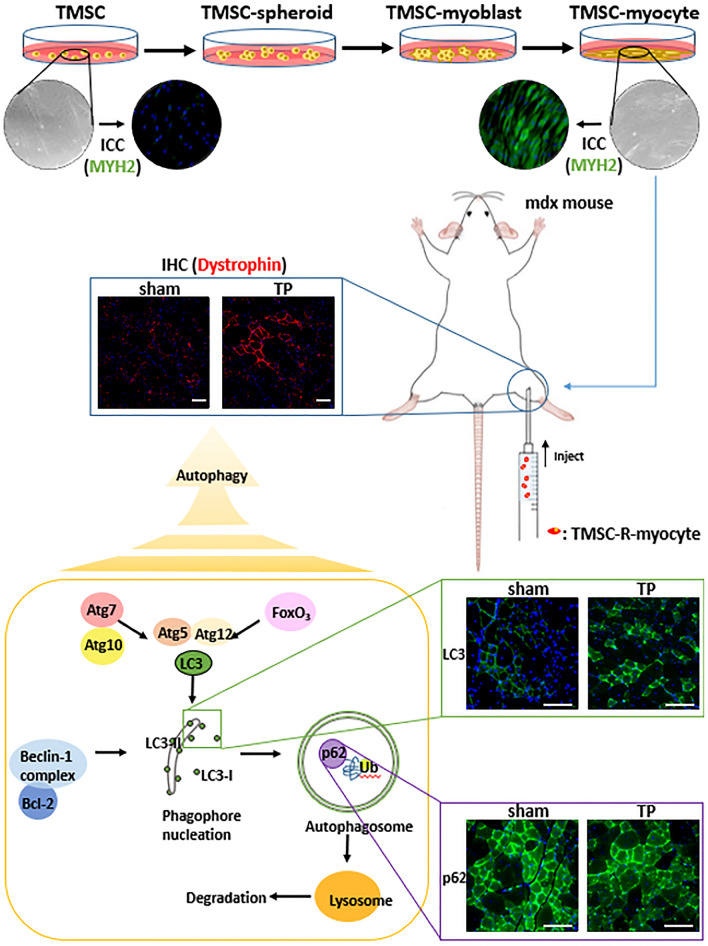

Based on these characteristics, TMSC-myocytes have been transplanted into mdx mice, a mouse model of DMD, to investigate whether they can help improve the symptoms of DMD. The red fluorescent protein gene was transduced into TMSC (TMSC-R) for tracking transplanted cells.

RESULTS:

Prior to transplantation (TP), it was confirmed whether TMSC-R-myocytes had the same differentiation potential as TMSC-myocytes. Increased expression of dystrophin and autophagy markers in the TP group compared with the sham group was confirmed in the gastrocnemius muscle 12 weeks after TP.

CONCLUSION:

These results demonstrate muscle regeneration and functional recovery of mdx via autophagy activation following TMSC-myocyte TP.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13770-022-00489-7.

Keywords: Tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells, Differentiation, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Mdx

Introduction

Skeletal muscle constitutes about 40–50% of the human body, performs many physiological functions, and is an essential component of the human body because it performs not only mechanical functions but also metabolic functions [1]. When skeletal muscles are damaged, they normally regenerate or recover themselves [2]. On the other hand, if muscle regeneration malfunctions, the purposes of skeletal muscles are altered or decreased. Skeletal muscle diseases can be divided into two types, ones that are caused by muscles directly and the others that are caused by other diseases associated with muscles. For instance, the former including muscular dystrophy, sarcopenia, and myopathy and the latter include diabetes and acquired immune deficiency syndrome [3].

Previous studies have demonstrated that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have therapeutic effects on skeletal muscle regeneration [4]. In addition, there are other studies concerning muscle regeneration using MSCs. For example, MSC-derived exosomes promote muscle regeneration [5], and human umbilical cord Wharton’s jelly-derived MSCs have a therapeutic effect in sarcopenia-induced mouse [6]. According to the previous research, we expected that MSCs would have a therapeutic effect on skeletal muscle diseases.

Tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells (TMSCs) were selected as a research source in this study, which were separated from the tissues that were discarded after tonsillectomy [7]. TMSC has superior proliferative ability compared to other MSCs [8], making it advantageous for the development of therapeutic agents by suitable cell sources. In addition, TMSCs have immunomodulatory functions upon transplantation [7], and these properties aid in recovery after injury [9]. For this reason, TMSCs are promising as a suitable resource for stem cell therapy.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X-linked genetic muscular disease that includes the absence of Dystrophin protein and is the most common type of muscular dystrophy. The phenotype is severe muscular dysfunction caused by degeneration of myofibers [10]. For the in vivo research of this disease, we used the mdx mouse, an animal model of DMD. The mdx mouse phenotype includes an absence of Dystrophin protein, just like in patients, but not as severe [11]. Many researchers have tried to find a treatment for DMD, and various treatments have been studied using the mdx mouse. For instance, Laminin-111, an important protein in skeletal muscle, has been injected into mdx mice [12], cardiosphere-derived cells have been injected into the heart of mdx mice [13], and muscle-specific dystrophin gene editing by CRISPR /Cas9 [14] etc. has been reported.

Autophagy is a eukaryotic cell recycling process and plays an important role in cell survival and maintenance through the breakdown of cytoplasmic organelles, proteins and macromolecules and recycling of degradation products [15]. Also, autophagy has been identified as a key regulatory mechanism during skeletal muscle development, regeneration and homeostasis, and uncontrolled autophagy is also associated with muscle disorders and aging-induced sarcopenia [16]. Recently, the studies processing to elucidate the role of autophagy in muscular disorders, including DMD and in loss of muscle mass in the elderly, referred as sarcopenia [17–19].

Based on the characteristics of TMSC-derived skeletal muscle cells (TMSC-myocytes) already identified in previous studies [4], we hypothesized that transplantation (TP) of these cells into the skeletal muscle of mdx mice would affect muscle regeneration. The cells to be used for transplantation were labeled with red fluorescent protein (RFP) and their differentiation potential was confirmed. After 12 weeks of TP, histopathological evaluation was performed to confirm muscle regeneration. To demonstrate the mechanism of recovery, autophagy markers were identified using IHC and western blotting.

Materials and methods

Cultivation of tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells

Tonsil tissue extracted from discarded tissue following tonsillectomy was washed with saline three times and then homogenized using sterilized scissors and a knife in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) on a 60 mm dish. Fragmented tissues were transferred to a 15 mL conical tube and Collagenase type I (210 U/mL, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and DNase (10 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were added. These mixtures were incubated at 36 °C for an hour on a shaker. Tissues were filtered with a cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and the filtered solution was pelleted down by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 5 min. Pellets were resuspended in low-glucose DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; Sigma-Aldrich) and plating on 100 mm cell-culture dishes. Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified chamber with 5% CO2 during passaging. Cells were used after passage 7. All TMSC production procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital (Seoul, permit number ECT-11–53-02, approval date: September 22, 2011).

Fluorescent labeling of TMSCs

The day before transduction, TMSCs (passage 5) were cultured in a 100 mm culture dish at a density of 1 × 106 in the growth medium. On the day of transduction, the medium was aspirated, and the cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then, 8 mL of new culture medium containing 5 μg/mL polybrene were added to the dish. Next, viral soup (2 × 106 IFU/mL Lentivirus-5 negative control (Lenti-X GoStic) recombinant lentivirus (Egg biotech, Daegu, Korea) were added, and the media were mixed gently. The cells were incubated overnight at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% (v/v) CO2. The next day, morphologic changes and RFP expression were observed using a fluorescence phase-contrast microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The medium was then replaced with fresh medium containing 2–3 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Upon reaching 80%–90% confluence, adherent cells were trypsinized using 0.25% (w/v) trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen) and replated at a 1:3 dilution.

Differentiation of TMSCs

To differentiate TMSCs into skeletal muscle cells, we used a previously established technique [9]. To form a spherical aggregation of TMSCs, attached cells were dissociated from dishes using trypsin–EDTA (0.25%) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and cultured in a suspension on 100 mm petri dishes for a day with the same media. The formed spheroids were transferred to a collagen-coated dish with myoblast media; DMEM/nutrient mixture (DMEM/F-12; Invitrogen) containing 1% nonessential amino acid (Invitrogen), 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 μL/mL transforming growth factor-β (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and 1% P/S, and cultured for four days to differentiate TMSC spheroids to myoblasts. To differentiate TMSCs-myoblasts into myocytes, the myoblast medium was replaced with a myocyte medium; low-glucose DMEM containing 2% FBS, 10 ng/mL insulin-like growth factor 1 (R&D Systems) and 1% P/S. The whole procedure of the differentiation of TMSC-myocyte was taken for 2–4 weeks.

Human skeletal muscle cells culture and differentiation

Human skeletal muscle cells (hSKMCs; Cell Applications, San Diego, CA, USA) were used as a positive control for TMSC-myocyte differentiation studies. These cells were cultured with growth medium (Cell Applications). After the cells fully covered 100 mm cell-culture dishes, the medium was replaced with differentiation medium (Cell Applications) for a week.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and Western blotting analysis

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and Western blotting (WB) analysis were performed as described previously [4]. The sequences of the forward and reverse primers used are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The primary antibodies used for WB are described in Supplementary Table 2.

Immunocytochemistry (ICC)

The cells were fixed with 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde solution (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4 °C, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Biosesang, Seongnam-si, Korea) for 20 min at room temperature (RT), blocked for 1 h with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Bovogen, East Keilor VIC, Australia) at RT, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody. Next day the cells were incubated in the secondary antibody for an hour at RT. Vectashield mounting medium, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) was dropped on the slide and the coverslips which side the cells were attached were placed on the slide. The images were photographed using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Ti2-U, Tokyo, Japan). Information on the antibodies such as manufacturers and catalog numbers (Cat. No.) were listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Transplantation

1 × 105 TMSC-myocytes were diluted in 100 μL Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS; Gibco) and transplanted into both gastrocnemius muscles (n = 5) of mdx mice at 6–12 weeks of age. As a positive control, W/T mice (n = 4) of the same age were used, and a sham group (n = 4) transplanted with DPBS only was used as a negative control. All mice used in this study were male.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain

Embedded muscle tissues were cut into 5 μm slices and placed on slides. Sections were deparaffinized by incubation in xylene (Duksan, Sejong-si, Korea), hydrated through a graded series of alcohols. The slides were boiled at 95 °C for 10 min in a water bath incubated in antigen retrieval buffer (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Samples were blocked and permeabilized with a blocking buffer that contained 1% BSA and 0.5% Triton X-100 for an hour at RT and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. Next day the sections were incubated with secondary antibody hour at RT. Vectashield mounting medium was dripped on sections and coverslips were placed on them. Images were photographed using a fluorescence microscope Nikon Ti2-U. The information of the antibodies such as manufacturers and Cat. No. were listed in Supplementary Table 2. For H&E staining, sections were stained with a standard technique to determine the histological changes in the three groups. The stained slides were observed and photographed under a light microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Each test was performed more than three times. Results were described as mean ± standard error of the mean. The statistical significance of differences was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey multiple comparison test using PRISM version 5.01 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was regarded as p < 0.05.

Results

TMSCs have the ability to differentiate into the myocyte

To ensure differentiation into myocytes, the morphology of TMSC transduced with RFP (TMSC-R) and TMSC-R-myocytes was observed using an optical microscope. TMSC-R were observed as undifferentiated stem cells (Fig. 1A, panels a, b), and TMSC-R-myocytes were observed as myofiber after differentiation (Fig. 1A, panels c, d). Both of them expressed red fluorescence (Fig. 1A, panels a, c). Similarly, ICC was conducted to identify skeletal muscle markers in TMSC-R-myocytes. Myosin 4 (MYH4) and Myogenin showed only low expression before differentiation and increased expression in TMSC-R-myocytes (Fig. 1B). Myosin 4 is expressed during postnatal developing muscles or type 2B muscle fibers of adult muscles [20] and myogenin is one of the myogenic regulatory factors in skeletal muscles [21]. The expression of skeletal muscle gene such as myogenin, Myf6, MYH2, and MYH8 were analyzed using RT-PCR (Fig. 1C) in TMSC-R (Fig. 1C, lane a), TMSC-R-myocyte 2w, 3w, 4w (Fig. 1C, lanes b, b’, b’’) and hSKMC, a positive control (Fig. 1C, lane c). Myf6 required for maintenance of the muscle stem cell pool, was expressed in all cells and decreased with the duration of differentiation into TMSC-R-myocytes. The Myogenin expression increased according to differentiation progress from 2 to 4 weeks, and the MYH8 expressed in embryonic and fetal developing muscles and specific adult muscles was more expressed at 2 and 4 weeks than 3 weeks after differentiation. The expression of MYH2 expressed in developing fetal muscles and type 2A muscle fibers of adult muscles was only expressed at TMSC-R-myocyte 3w.

Fig. 1.

Establishment of the potential of skeletal myogenic differentiation of RFP+ tonsil-derived stem cell (TMSC-R). A Morphology of the TMSC-R and TMSC-R-myocyte was observed by fluorescence (panels a and c) and optical microscopy (panels b and d). Scale bars indicate 100 μm. B Myosin 4 and Myogenin were expressed green TMSC-R-myocytes (panels b and d), but not in TMSC-R (panels a and c) in ICC analysis. The cells were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars indicate 100 μm. C mRNAs were isolated from undifferentiated TMSC-R (lane a), TMSC-R-myocyte 2w, 3w, 4w (lane b, b’, b’’ respectively), and hSKMCs (lane c), converted to cDNAs, and used for RT-PCR, too. Abbreviations: ICC, immunocytochemistry; RFP, red fluorescent protein; w, weeks for differentiation; MYH4, Myosin heavy chain 4; MYH8, Myosin heavy chain 8; MYH2, Myosin heavy chain 2; hSKMCs, human skeletal muscle cells

Comparison of the differentiation capacity of TMSC and TMSC-R into myocytes

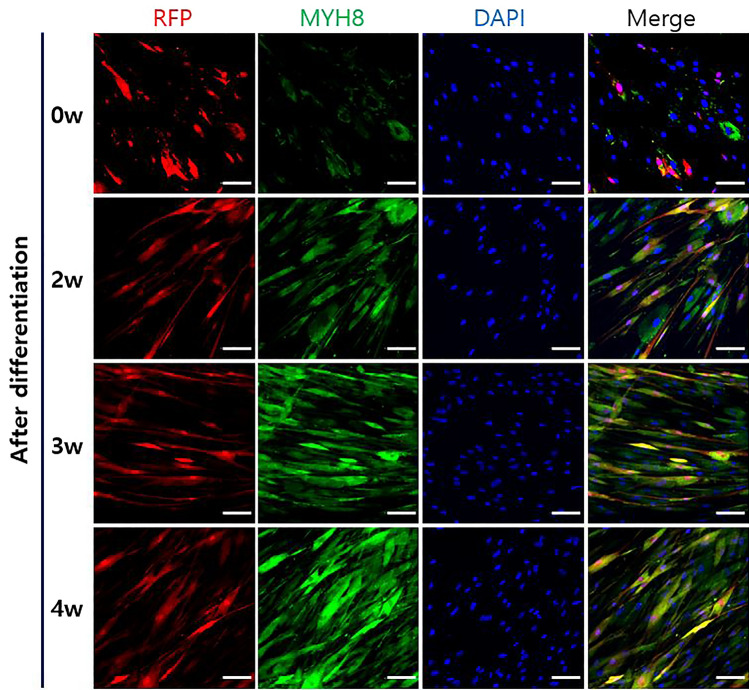

The protein expressions were compared between TMSC-myocyte and TMSC-R-myocyte to confirm the maintaining of differentiation after RFP-tagging by ICC. The Myogenin protein showed low expression before differentiation and much brighter signaling after differentiation in both groups before and after RFP-tagging (Fig. 2A). MYH3, Titin and MYH2 were hardly expressed at undifferentiation period, but their expressions were increased during 2–4 weeks after differentiation regardless of RFP-tagging (Fig. 2B–D). In addition, we compared the co-expression of RFP and MYH8 before and after differentiation in TMSC-R-myocytes. The brightness of MYH8 increased as the differentiation period (Fig. 3, lanes 2-4w) was longer than before differentiation (Fig. 3, lane 0w), and that of RFP maintained (Fig. 3). TMSC-R-myocytes did not form myotube, but the multinucleated cells, a symbol of functional skeletal muscle were observed in TMSC-R-myocytes 3w and 4w (Figs. 3, 4). As a result of these studies, we used TMSC-R-myocytes 4w for TP of the mdx mice.

Fig. 2.

Confirmation of the myogenic differentiation ability of RFP+ tonsil-derived stem cell (TMSC-R) by ICC. Expression of skeletal muscle-related markers (green) such as myogenin A, MYH3 B Titin C and MYH2 D was confirmed, and increased as the differentiation period was extended, up to 4 weeks. The cells were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The scale bars indicate 100 μm. Abbreviations: MYH3, Myosin heavy chain 3

Fig. 3.

Maintenance of RFP expression of TMSC-R-myocytes during differentiation for 4 weeks. ICC showed that the expression of MYH8 (green) increased and RFP (red) remained constant of TMSC-R-myocytes during differentiation. The cells were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The scale bars indicate 100 μm. Abbreviations: MYH8, Myosin heavy chain 8

Fig. 4.

Skeletal muscle regeneration by TMSC-R-myocytes transplantation in mdx mice. TMSC-R-myocytes were injected intramuscularly into the right gastrocnemius muscle. Twelve weeks after TP, the cross-sections of those muscles were analyzed by IHC. A There was a minimal expression of skeletal muscle marker such as Dystrophin (red), Titin (red), MHC (red) and MYH1E (green) in sham group mice (panels a, d, g and j), whereas their expression was more detected in TP group (panels b, e, h and k) in the gastrocnemius muscle. As a positive control, the muscle of age-matched W/T mice (panels c, f, i and l) were also compared to mdx mice. The cells were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Magnification is × 100 (panels a-i) and × 200 (panels j-l). B Distribution of the TMSC-myocytes were observed at 4 weeks after TP in the gastrocnemius, and RFP and HM (green) were not expressed simultaneously in sham group mice (panels a-d), whereas it was clearly expressed in TP group (panels e–f). The cells were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Magnification is × 100. Abbreviations: TP, transplantation; IHC, immunohistochemistry; W/T, wild type; MHC, Myosin heavy chain; MYH1E, Myosin heavy chain1E; HM, human mitochondria

Skeletal muscle regeneration following TMSC-R-myocytes transplantation into mdx mice

Twelve weeks after TP, the gastrocnemius muscle tissues were analyzed the effect of muscle regeneration according to TP by IHC. Since an etiology of mdx mice is a deficiency of Dystrophin, we investigated this first. In the W/T group, Dystrophin was highly expressed in the cell membrane (Fig. 4A, panel c). Although expression decreased in the TP group (Fig. 4A, panel b), it was greater than expression in sham group (Fig. 4A, panel a). In addition, expression of skeletal muscle markers such as Titin and Myosin heavy chain (MHC) in red color in the cytosol was the highest in W/T group (Fig. 4A, panels f, i), followed by TP group (Fig. 4A, panels e, h), and lowest in sham group (Fig. 4A, panels d, g). Double staining of MYH1E and Dystrophin also confirmed that the expression was increased in TP group (Fig. 4A, panel k) compared with sham group (Fig. 4A, panel j), although not as much as in W/T group (Fig. 4A, panel l).

To determine how long the transplanted TMSC-R-myocyte exist in the gastrocnemius, IHC was performed with an antibody against human mitochondria (HM) in 2, 4 and 6 weeks after TP. At 2 (data not shown) and 4 weeks after TP, cells expressing RFP and HM were observed simultaneously in the TP group (Fig. 4B, panels e–h), but not in all the experimental groups at 6 weeks (data not shown).

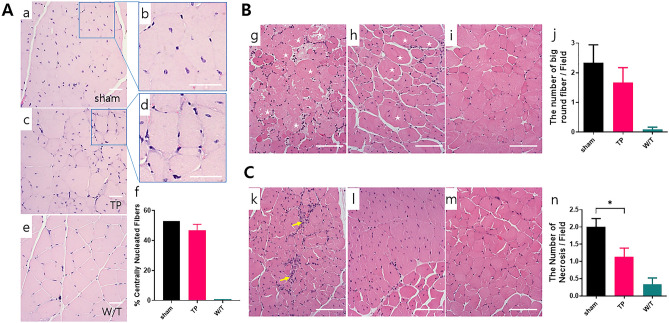

Twelve weeks after TP, H&E staining was performed to compare the morphology of muscle fibers. The peripheral nuclear myofibers are located in normal mice and the central nucleic acid (CN) myofibers, a hallmark of skeletal muscle regeneration, are located in mdx mice. CN myofibers (Fig. 5A) were visible more in the sham group (Fig. 5A, panels a, b) than in the TP group (Fig. 5A, panels c, d) and were not found in the W/T group (Fig. 5A, panel e). In addition, normal myofiber have a polygonal shape, not a round shape. The big round fibers (Fig. 5B) were found a little more in the sham group than in the TP group. Specifically, the fiber shape of the sham group (panel g) was more circular than that of the TP group (Fig. 5B, panel h). Even in the W/T group, sometimes single large fibers were found (Fig. 5B, panel i). The above two analyses were not statistically significant (Fig. 5B, panel f, j). Necrosis is a typical symptom that appears in mdx mouse, and the aggregation of distorted nuclei is collocated with the necrosis [22]. Necrotic spots (Fig. 5C) were widely distributed in muscle tissues of the sham group (Fig. 5C, panel k), whereas were smaller in those of the TP group (Fig. 5C, panel l) and were rarely found in the W/T group (Fig. 5C, panel m). The statistical analysis of the number of necrosis spots per field was statistically significant (Fig. 5C, panel n).

Fig. 5.

Assessment of the degree of muscle damage or recovery by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The number of centrally nucleated fibers A, big round fibers B and necrosis spots C in each group was counted, and three glass slides were read for each mouse. Centrally nucleated fibers were found in the images of both the sham (panels a and b) and TP groups (panel c and d), but not in that of the W/T group (panel e). To show the centrally nucleated fibers in more detail, enlarged images of the sham (panel b) and TP groups (panel d) are displayed next to each other. The number of big round fibers was lower in TP group (panel h) than in the sham group (panel g) and almost absent in the W/T (panel i) group. Necrosis fields were often observed in sham group (panel k), with less in TP group (panel l) and almost none in the W/T (panel m) group. Each analysis was quantified graphically (panels f, j, and n). H&E staining was detected by an image analyzer, the scale bars indicate 100 µm. ✩, big rounded fiber; → necrosis spot. Statistical analysis with one-way ANOVA (* p < 0.05). Abbreviations: H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; W/T, wild type

Fig. 7.

Schematic illustration of muscle regeneration-related autophagy pathway after transplantation (TP). TMSCs were differentiated into myocytes and were transplanted into mdx mice. It was identified that muscle regeneration improved after TP of TMSC-myocyte, and the activation of autophagy induced muscle regeneration. The scale bars indicate 100 µm.

Autophagy signal pathway was involved in the skeletal muscle regeneration following TMSC-R-myocytes transplantation

Autophagy plays several important roles in skeletal muscle such as maintaining the muscle mass and function and differentiation [23]. To find the pathway of muscle regeneration in the mdx mice, autophagy markers were identified using IHC (Fig. 6A) and western blot (Fig. 6B, C). Bcl-2 and light chain 3 (LC3), the key proteins of autophagy, were expressed more in the TP group (Fig. 6A, panels b, e) than in sham group (Fig. 6A, panels a, d) but not as much as in W/T group (Fig. 6A, panels c, f). Also, P62 protein is degraded when the autophagy is activated as opposed to LC3II by autolysosome after forming autophagosomes [24], the expression of which was most in sham group (Fig. 6A, panel g), less in TP group (Fig. 6A, panel h), and very weak in W/T group (Fig. 6A, panel i). In WB analysis, LC3 appears as two bands, the upper one is LC3I and the lower one is LC3II, and the transition of LC3I to LC3II means autophagy is activated. The lower bands were more distinct in the TP group than in sham group, and weak in W/T group (Fig. 6B). Unlike this result, the expression of LC3 in ICC was brighter in W/T group because both LC3I and LC3II expressions were included. The bands of P62 were thicker in sham group than in the TP group, and very weak in the W/T group (Fig. 6C). These results also showed that autophagy was activated in the TP group, and it would be related to muscle regeneration.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of the relationship between muscle regeneration and autophagy. A Cross-sections of those muscle analyzed by IHC. The expression of Bcl-2 (green, panels a-c) and LC3 (green, panels d-f) showed the same trend as the activation of autophagy, whereas P62 (green, panels g-i) was opposite. The cells were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The scale bars indicate 100 µm. (Sham group; panels a, d, and g, TP group panels b, e, and h, W/T group; panels c, f, and i). B In the Western blot results, the expression of LC3 and P62 in the extracted those muscle showed a similar trend to the IHC result. The expression levels were compared by quantification with GAPDH using ImageJ software. ← Correct band size. Statistical analysis with one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05; * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001)

Discussion

Over the decades, there have been many trials to develop a medical treatment for DMD. In particular, mdx mouse has been the most commonly used as DMD model because they have the same genetic mutation with human [25]. Protein replacement by utrophin-based therapies is also of great value for the treatment of DMD. Currently, drugs for oral administration using pathological mechanisms such as antifibrosis, anti-inflammatory, and Ca dysregulation are being studied preclinically. In particular, gene and cell-based therapeutic strategies have long been studied for DMD [26–28]. The cells for transplantation include muscle progenitor cells and/or stem cells obtained from healthy donors. In addition, the muscle progenitor cells, or myoblasts are able to isolate from adult or prenatal muscle tissues, but the number of cells that can be harvested is limited. Therefore, stem cells might be a suitable source of cells for therapy of skeletal muscle disease.

We used TMSCs that have the capacity to differentiate into various lineage such as myogenic, neuronal, endodermal, Schwann-like cell and parathyroid-hormone releasing cells in this study [4, 7, 29, 30]. In previous studies, we reported that TMSCs are capable of differentiating into skeletal muscle cells, and that these cells exhibit therapeutic effects in muscle injury models and peripheral nerve injury animal models [4, 31]. MSCs from other sources such as adipose tissue and urine also can be differentiated into skeletal muscle cells [32, 33]. Although differentiation capacity into skeletal myocytes of each MSC did not be compared, TMSCs might be one of promising source for DMD because TMSCs exhibit primitive myogenic satellite characteristics even in undifferentiated state and have excellent proliferation ability [4, 7].

In this study, the existing differentiation period was extended from 2 to 4 weeks, and as a result, a long, multinucleated form like the root canal was confirmed (Fig. 1A). Therefore, TMSC-myocyte 4w with the highest expression of skeletal muscle-related markers such as myogenin, MYH3, titin, MYH2 and MYH8 was used in the TP experiment of mice [34–36]. Protein expression of MYH8 increased as differentiation progressed, but the gene expression increased in TMSC-myocytes 2w and 4w and decreased in TMSC-myocytes 3w. This result seems to be the case in which genes and proteins are expressed differently depending on the state of the cell even in the same cell [37, 38].

To observe the period of exist the TMSC-myocyte in vivo, myogenic differentiation capacity of the TMSC-R was compared with TMSC in vitro. The differentiation ability of TMSC-myocytes was confirmed even after RFP-tagging (Fig. 1), and the expression of Myogenin, MYH3, Titin, and MYH2 was similarly increased in both cells as differentiation proceeded regardless of labeling (Fig. 2). We demonstrated that TMSC-R-myocytes having the potential of myogenic differentiation, existed in gastrocnemius of mdx mice over 4 weeks post-TP (Fig. 4B). These fluorescently-labeled stem cells can be used for non-invasive evaluation of safety and efficacy for the development of therapeutic agents, and studies on the differentiation potential of GFP-labeled stem cells have already been reported [39, 40].

Skeletal muscle regeneration in mdx mice due to TMSC-R-myocyte was confirmed through the expression of Dystrophin, a fundamental defect in DMD [14], and other typical markers (Titin, MHC and MYH1E) [18–21, 41] at 12 weeks after TP (Fig. 4A). In addition, muscle regeneration in mice was confirmed through histopathological analysis. The TP group showed a tendency to regenerate than the sham group in the ratio of the central nucleus and the distribution of big round fibers and necrotic fields [42–44]. These results support the therapeutic potential of TMSC-myocytes for the repair of damaged muscle tissue.

To confirm the distribution of TMSC-myocytes, the expressions of HM at the transplant sites were examined at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after TP in this study. As a result, HM was appeared at 2 and 4 weeks after TP, and the results of 4 week were only presented (Fig. 4B). In addition, although only one dose of the cells was applied in this experiment for TP, further studies are needed for various cell-dose, long-term efficacy evaluation beyond 12 weeks and comparison with human skeletal muscle cells.

Autophagy is an important cellular recycling process including degradation, and is included in the muscle regeneration process [15, 23] and the mechanism of myogenic differentiation in previous studies [45]. Based on these previous studies, autophagy was predicted as a mechanism of muscle regeneration through the TP of TMSC-myocyte, and related experiments were performed. Bcl-2 is a regulator of apoptosis and the increase in it produces inhibition of apoptosis, and thus autophagy increases [46]. One of the main mechanisms for regulating autophagy is by regulating the interaction between the autophagy proteins Beclin 1 and Bcl-2. The Bcl-2, identified in this study, plays an important role in cell or tissue regeneration through autophagy without falling into apoptosis [47]. LC3 is found in all types of autophagic membranes and LC3I to LC3II conversion is used to determine the activation of autophagy [48]. p62 is degraded by autophagy, so when autophagy is induced, the expression of p62 decreases [48]. The autophagy markers LC3 and p62 are oppositely expressed and are known to play important biological roles. In this study, the IHC results showed a completely opposite correlation (Fig. 6A), but not in WB (Fig. 6B, C). However, comparing only the sham and TP groups in the WB results, LC3 and p62 showed a contradictory correlation as a typical autophagy mechanism. These results support the possibility that autophagy may participate in muscle regeneration, and are consistent with previously reported studies on the regulation of autophagy for DMD treatment [16, 17]. Further studies of the autophagy pathway following TP of TMSC-myocytes will contribute to their application to DMD as well as other skeletal muscle diseases [18, 19].

In conclusion, we identified that TMSC can differentiate into skeletal myocytes in vitro and TMSC-myocyte was transplanted into the mdx mice. In several histopathological tests, significant recovery was observed. In addition, the autophagy activation is closely related to the mechanism of muscle regeneration in mdx mice derived by TP with TMSC-R-myocyte (Fig. 7). TMSC-myocytes enabled skeletal muscle regeneration in mdx mice by paracrine effect, followed by promoting damaged muscle recovery through autophagy induction. These results showed that TMSC-myocyte can be one of the promising therapeutic resources for hereditary muscle disease as well as for damaged or degenerative muscle disorders.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science & ICT (grant number, 2017M3A9B3063636), the Basic Science Research Pro-gram through the NRF funded by the Ministry of Education (2019R1I1A1A01060308) and the RP-Grant 2021 of Ewha Womans University.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ewha Womans University Medical Center (EWUMC) institutional review board (IRB number: ECT-2011–09-003). All the experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee for animal research at Ewha Woman’s University (EUM20-051). Informed Consent Statement: Informed written consent was obtained from all the patients participating in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Saeyoung Park and Soyeon Jeong have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Sui SX, Williams LJ, Holloway-Kew KL, Hyde KN, Pasco JA. Skeletal muscle health and cognitive function: a narrative review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:255. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamakawa H, Kusumoto D, Hashimoto H, Yuasa S. Stem cell aging in skeletal muscle regeneration and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1830. doi: 10.3390/ijms21051830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Truskey GA. Development and application of human skeletal muscle microphysiological systems. Lab Chip. 2018;18:3061–3073. doi: 10.1039/c8lc00553b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S, Choi Y, Jung N, Yu Y, Ryu KH, Kim HS, et al. Myogenic differentiation potential of human tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells and their potential for use to promote skeletal muscle regeneration. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37:1209–1220. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakamura Y, Miyaki S, Ishitobi H, Matsuyama S, Nakasa T, Kamei N, et al. Mesenchymal-stem-cell-derived exosomes accelerate skeletal muscle regeneration. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:1257–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang QQ, Jing XM, Bi YZ, Cao XF, Wang YZ, Li YX, et al. Human umbilical cord Wharton’s jelly derived mesenchymal stromal cells may attenuate sarcopenia in aged mice induced by hindlimb suspension. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:9272–9281. doi: 10.12659/MSM.913362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oh SY, Choi YM, Kim HY, Park YS, Jung SC, Park JW, et al. Application of tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells in tissue regeneration: concise review. Stem Cells. 2019;37:1252–1260. doi: 10.1002/stem.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu Y, Park YS, Kim HS, Kim HY, Jin YM, Jung SC, et al. Characterization of long-term in vitro culture-related alterations of human tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells: role for CCN1 in replicative senescence-associated increase in osteogenic differentiation. J Anat. 2014;225:510–518. doi: 10.1111/joa.12229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HJ, Jung H, Kim DK. IDO and CD40 may be key molecules for immunomodulatory capacity of the primed tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5772. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yiu EM, Kornberg AJ. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51:759–764. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spurney CF, Gordish-Dressman H, Guerron AD, Sali A, Pandey GS, Rawat R, et al. Preclinical drug trials in the mdx mouse: assessment of reliable and sensitive outcome measures. Muscle Nerve. 2009;39:591–602. doi: 10.1002/mus.21211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rooney JE, Gurpur PB, Burkin DJ. Laminin-111 protein therapy prevents muscle disease in the mdx mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7991–7996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811599106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aminzadeh MA, Rogers RG, Fournier M, Tobin RE, Guan X, Childers MK, et al. Exosome-mediated benefits of cell therapy in mouse and human models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;10:942–955. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bengtsson NE, Hall JK, Odom GL, Phelps MP, Andrus CR, Hawkins RD, et al. Muscle-specific CRISPR/Cas9 dystrophin gene editing ameliorates pathophysiology in a mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14454. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parzych KR, Klionsky DJ. An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:460–473. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiacco E, Castagnetti F, Bianconi V, Madaro L, De Bardi M, Nazio F, D'Amico A, Bertini E, Cecconi F, Puri PL, Latella L. Autophagy regulates satellite cell ability to regenerate normal and dystrophic muscles. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:1839–1849. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Palma C, Morisi F, Cheli S, Pambianco S, Cappello V, Vezzoli M, Rovere-Querini P, Moggio M, Ripolone M, Francolini M, Sandri M, Clementi E. Autophagy as a new therapeutic target in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e418. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitehead NP, Kim MJ, Bible KL, Adams ME, Froehner SC. A new therapeutic effect of simvastatin revealed by functional improvement in muscular dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:12864–12869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509536112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubinsztein DC, Marino G, Kroemer G. Autophagy and aging. Cell. 2011;146:682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiaffino S, Rossi AC, Smerdu V, Leinwand LA, Reggiani C. Developmental myosins: expression patterns and functional significance. Skelet Muscle. 2015;5:22. doi: 10.1186/s13395-015-0046-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernández-Hernández JM, García-González EG, Brun CE, Rudnicki MA. The myogenic regulatory factors, determinants of muscle development, cell identity and regeneration. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;72:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farini A, Sitzia C, Villa C, Cassani B, Tripodi L, Legato M, et al. Defective dystrophic thymus determines degenerative changes in skeletal muscle. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2099. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22305-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masiero E, Agatea L, Mammucari C, Blaauw B, Loro E, Komatsu M, et al. Autophagy is required to maintain muscle mass. Cell Metab. 2009;10:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klionsky DJ, Abdel-Aziz AK, Abdelfatah S, Abdellatif M, Abdoli A, Abel S, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (4th edition). Autophagy. 2021;17:1–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.van Putten M, Putker K, Overzier M, Adamzek WA, Pasteuning-Vuhman S, Plomp JJ, et al. Natural disease history of the D2 -mdx mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. FASEB J. 2019;33:8110–8124. doi: 10.1096/fj.201802488R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun C, Shen L, Zhang Z, Xie X. Therapeutic strategies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an update. Genes (Basel) 2020;11:837. doi: 10.3390/genes11080837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao S, Chen Z, Yu Y, Zhang N, Jiang H, Zhang G, Zhang Z, Zhang B. Current pharmacological strategies for duchenne muscular dystrophy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:689533. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.689533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Happi Mbakam C, Lamothe G, Tremblay JP. Therapeutic strategies for dystrophin replacement in duchenne muscular dystrophy. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9:859930. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.859930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung N, Park S, Choi Y, Park JW, Hong YB, Park HH, et al. Tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into a Schwann cell phenotype and promote peripheral nerve regeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1867. doi: 10.3390/ijms17111867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JY, Park S, Oh SY, Nam YH, Choi YM, Choi Y, Kim HY, Jung SY, Kim HS, Jo I, Jung SC. density-dependent differentiation of tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells into parathyroid-hormone-releasing cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:715. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park S, Choi Y, Kwak G, Hong YB, Jung N, Kim J, Choi BO, Jung SC. Application of differentiated human tonsil-derived stem cells to trembler-J mice. Muscle Nerve. 2018;57:478–486. doi: 10.1002/mus.25763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bansal V, De D, An J, Kang TM, Jeong HJ, Kang JS, Kim KK. Chemical induced conversion of mouse fibroblasts and human adipose-derived stem cells into skeletal muscle-like cells. Biomaterials. 2019;193:30–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen W, Xie M, Yang B, Bharadwaj S, Song L, Liu G, et al. Skeletal myogenic differentiation of human urine-derived cells as a potential source for skeletal muscle regeneration. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2017;11:334–341. doi: 10.1002/term.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganassi M, Badodi S, Wanders K, Zammit PS, Hughes SM. Myogenin is an essential regulator of adult myofibre growth and muscle stem cell homeostasis Elife. 2020;9:e60445. doi: 10.7554/eLife.60445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tajsharghi H, Oldfors A. Myosinopathies: pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:3–18. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1024-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herzog W. The role of titin in eccentric muscle contraction. J Exp Biol. 2014;217:2825–2833. doi: 10.1242/jeb.099127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo Y, Xiao P, Lei S, Deng F, Xiao GG, et al. How is mRNA expression predictive for protein expression? A correlation study on human circulating monocytes. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2008;40:426–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2008.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Zhang Y. Li J, Zhang Y, Yang C and Rong R (2020) Discrepant mRNA and protein expression in immune cells. Curr Genomics. 2020;21:560–563. doi: 10.2174/1389202921999200716103758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu J, Su X, Zhu C, Pan Q, Yang J, Ma J, Shen L, Cao H, Li L. GFP labeling and hepatic differentiation potential of human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35:2299–2308. doi: 10.1159/000374033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Islam I, Sriram G, Li M, Zou Y, Li L, Handral HK, Rosa V, Cao T. In Vitro osteogenic potential of green fluorescent protein labelled human embryonic stem cell-derived osteoprogenitors. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:1659275. doi: 10.1155/2016/1659275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swist S, Unger A, Li Y, Vöge A, von Frieling-Salewsky M, Skärlén Å. Maintenance of sarcomeric integrity in adult muscle cells crucially depends on Z-disc anchored titin. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4479. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18131-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moorwood C, Barton ER. Caspase-12 ablation preserves muscle function in the mdx mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:5325–5341. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Odom GL, Gregorevic P, Allen JM, Finn E, Chamberlain JS. Microutrophin delivery through rAAV6 increases lifespan and improves muscle function in dystrophic dystrophin/utrophin-deficient mice. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1539–1545. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klyen BR, Shavlakadze T, Radley-Crabb HG, Grounds MD, Sampson DD. Identification of muscle necrosis in the mdx mouse model of duchenne muscular dystrophy using three-dimensional optical coherence tomography. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16:076013. doi: 10.1117/1.3598842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park S, Choi Y, Jung N, Kim J, Oh S, Yu Y, et al. Autophagy induction in the skeletal myogenic differentiation of human tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Med. 2017;39:831–840. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Jin XF, Zhou XH, Dong XH, Yu WT, et al. The role of astragaloside IV against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury: suppression of apoptosis via promotion of p62-LC3-autophagy. Molecules. 2019;24:1838. doi: 10.3390/molecules24091838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Decuypere JP, Parys JB, Bultynck G. Regulation of the autophagic bcl-2/beclin 1 interaction. Cells. 2012;1:284–312. doi: 10.3390/cells1030284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang P, Mizushima N. LC3- and p62-based biochemical methods for the analysis of autophagy progression in mammalian cells. Methods. 2015;75:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.