Abstract

Swine pasteurellosis is one of the most economically important diseases of pig caused by Pasteurella multocida (P. multocida) capsular types A and D. These organisms are commensals and opportunistic pathogens in the upper respiratory tract in pig. In the present study, we extracted whole outer membrane proteins (OMP) from P. multocida capsular types A and D and were mixed together in the ratio of 1:1 forming bivalent outer-membrane proteins. The bivalent OMP was adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles. The size of aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles adsorbed outer membrane protein was found to be in the range of 125 to 130 nm. We observed that aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles adjuvanted bivalent OMP-based vaccine elicited quicker immune kinetics in terms of IgG response as compared to aluminum hydroxide microparticles adjuvanted bivalent bacterin vaccine against P. multocida capsular type A and D.

Keywords: Pasteurella multocida, Outer membrane protein (OMP), Nanoparticles, Vaccine, Aluminum hydroxide

Introduction

The P. multocida is broadly classified into 5 capsular types viz. A, B, D, E, and F. The capsular type B is primarily involved in causing hemorrhagic septicemia in cattle and buffaloes in India. On the other hand, the capsular types A and D are involved in the causation of swine pasteurellosis in pigs [1, 2]. The disease can be controlled by following proper managemental practices such as avoiding overcrowding of animals especially during rainy seasons and by routine vaccination in endemic areas.

The vaccination against swine pasteurellosis that is practiced in India involves the bacterin vaccine (adjuvanted with either alum or oil) that is obtained from P. multocida capsular type B (P52 strain). This vaccine appears to be less effective against swine pasteurellosis as the later is caused by capsular types A and D of P. multocida. Hence, we believe that the vaccine containing immunogenic components of these two capsular types would be more efficient in eliciting protective immune response against swine pasteurellosis. In the present study, we have proposed to test the protective immunopotential of outer membrane proteins of capsular types A and D of P. multocida adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide nanoparticle. Several workers have shown the better immunopotential of outer membrane proteins of P. multocida in various animal models [3–5]. The aluminum hydroxide have been used for many decades as an adjuvant and is efficient in eliciting short-term immune response [6, 7]. Recently, the aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles have been shown to elicit better immune response than its aluminum hydroxide microparticle counterpart [8]. In this study, we have demonstrated the better protective potential of bivalent outer membrane protein (obtained from capsular type A and D of P. multocida) adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles than the whole cell bacterin vaccine adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide microparticle.

Materials and methods

Pasteurella multocida isolates

The field isolates of P. multocida belonging to capsular types A and D of porcine origin were obtained from the repository of Network Project on Haemorrhagic Septicaemia, Department of Veterinary Microbiology, College of Veterinary Science, Assam Agricultural University, Khanapara, Guwahati, Assam, India. Pasteurella multocida types A and D isolates selected for the present study were revived by inoculating onto 5% sheep blood agar by streak plate method as described by Collins [9]. The inoculated plate was then incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 18 h. After incubation, isolated single colonies showing typical characteristics were picked up for preparation of smear and staining by Gram’s stain and methylene blue stain.

Preparation of whole OMPs of P. multocida capsular types A and D

The whole outer membrane proteins were extracted from the capsular types A and D of P. multocida as per the method described by Choi-Kim et al. [10]. The overnight grown cultures were transferred to the fresh BHI broth (brain heart infusion) containing 0.5% yeast extract and incubated for 6 h at 37 °C in shaker cum incubator. The culture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was decanted and the bacterial pellet was washed thrice in M PBS (pH 7. 4) by repeated centrifugation. The pellet was resuspended in 10 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4 (Sigma, USA). The cell suspension was sonicated at 1-min cycle for 10 min (Sonics, Vibra-Cell). The unbroken cells and other debris were removed by the centrifugation. The supernatant was transferred to fresh tube and was filtered through sterile membrane filter of pore size of 0.45 μm followed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C (Beckman Coulter, USA). The pellet was re-suspended in 2% sodium lauroylsarcosinate (Sigma, USA) and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The OMPs were separated by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in sterile distilled water. The protein concentration of OMPs was estimated by Lowry’s method [11]. For preparation of bivalent OMP, the whole OMPs obtained from P. multocida capsular type A and D was mixed in the ratio of 1:1 (w/w). The proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE using the method described by Sambrook and Russels [12].

Preparation of aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles

The aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles were synthesized using the method described by Li et al. [8]. An equal volume of 0.015 M AlCl3. 6H2O (Sigma, USA) solution and a 0.04 N NaOH solution were added into a glass vial, and a small volume of 0.01 N NaOH was added to adjust the pH to 7.0. After 20 min of stirring at room temperature, the particle suspension was sonicated for 30 min to break down the particle size and centrifuged at 800 × g for 20 min to obtain the pellet. The pellet was washed with distilled water.

Conjugation of aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles with bivalent outer membrane protein

The conjugation of OMPs and aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles was carried out by mixing the nanoparticle suspension with the bivalent outer membrane proteins, in the ratio of 2:1 (w/w) followed by stirring of the suspension for 30 min at room temperature. The suspension was centrifuged at 800 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was decanted and the pellet was collected. The adsorption of OMP on the aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. This vaccine formulation was designated as Al(OH)3NP-OMP (A + D).

Characterization of Al(OH)3NP-OMP (A + D)–based vaccine

The characterization of Al(OH)3NP-OMP (A + D) was carried out in terms of size and zeta potential using transmission electron microscopy at the Sophisticated Analytical Instrument Facility (SAIF), North-Eastern Hill University (Shillong, India) and dynamic light scattering at the Institute of Advanced Studies in Science and Technology (Assam, India) respectively.

Immunization protocol in mice

For animal experiments, the Swiss Albino mice were used that were procured from Department of Veterinary Pharmacology, College of Veterinary Science, Assam Agricultural University, Khanapara, Guwahati (India). All the animal experiments were approved by Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of Assam Agricultural University. For immunization, two numbers of animal experiments were performed. The animal experiment-I was performed in order to analyze the IgG immune response of Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) and aluminum hydroxide microparticle adjuvanted bivalent bacterin (Al(OH)3MP-bacterin(A + D))–based vaccine. The group that was administered AlOH3NP-OMP(A + D) was subdivided into two subgroups. One subgroup was administered booster dose at 14 days (group “NP-OMP-B”) and the other without booster dose (group “NP-OMP-NB”) (Table 1). All the vaccines were injected intramuscularly. For separation of serum, the whole blood samples were collected from the tail vein of mice on the day before the primary immunization and on 7, 14, 21, 28, 45, and 60 days post-primary immunization (dppi). The serum was stored at − 20 °C till further use. The animal experiment-II was carried out to evaluate the protective potential of the vaccine formulation. The immunization was performed as in the animal experiment-I. Each of the groups of mice was sub-grouped into two (containing 6 mice in each subgroup). The subgroups were challenged with virulent P. multocida capsular type A or D at the dose rate of 100 × LD50 through intranasal route on the day where the humoral immune response was maximum (as determined in animal experiment-I). The mice were observed for 5 days for any clinical signs or death. The re-isolation of P. multocida was attempted from lung, liver, and spleen from the dead mice. At the end of 7 days, all surviving mice were sacrificed to attempt the re-isolation of P. multocida. The identity of the organism was confirmed by P. multocida -specific PCR [13].

Table 1.

Experimental design for the assessment of immunopotential in mice

| A) Animal experiment-I | |||

| Vaccine type | Group designation | Booster dose (days post-primary immunization) | Route of immunization |

| Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) | I | 14 | I/M |

| Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) | II | N/A | I/M |

| Al(OH)3MP-bacterin (A + D) | Bact | 14 | I/M |

| PBS (100 μl per mice) | C | 14 | I/M |

| B) Animal experiment-II | |||

| Vaccine type | Group designation | Challenge of vaccinated mice with P. multocida (100 × LD50/mice) | |

| Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) | IA | Capsular type A | |

| Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) | ID | Capsular type D | |

| Al(OH)3MP-bacterin (A + D) | BactA | Capsular type A | |

| Al(OH)3MP-bacterin (A + D) | BactD | Capsular type D | |

| PBS (100 μl per mice) | CA | Capsular type A | |

| PBS (100 μl per mice) | CD | Capsular type D | |

Estimation of serum IgG by indirect enzyme-linked immuno-sorbent assay (ELISA)

Three hundred ng of OMP of P. multocida capsular types A or D or 32 μg of crude P. multocida capsular types A or D per well of ELISA plate (polysorb) was coated into the 96 wells and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The plate was washed thrice with washing solution (PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20, pH 7. 4) and 100 μl blocking buffer (PBS containing 2% BSA) was added to each well and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The plate was washed in similar manner and then 100 μl 1:100 times diluted test serum was added and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. After incubation, the plate was washed thrice with washing solution. The 100 μl anti-mouse horse radish peroxidase conjugated IgG antibody (1:3000 dilution) was added to each well and the plate was kept for incubation for 1 h at 37 °C. The plate was then washed thrice with washing solution in similar manner and 100 μl of o-phenylenediamine (OPD) substrate was added to each well and incubated for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. After incubation, 100 μl of 1.5 N NaOH stop solution was added to each well. The OD values were read at 492 nm ELISA reader. The OD values were corrected with the background OD value of sera of negative control group that was not immunized (group C).

Statistical analysis

The experimental values were expressed as mean ± SEM. The difference among the groups were analyzed by within group and between groups mixed ANOVA followed by multiple comparison by Bonferroni correction. The analysis of challenge studies was carried out by the chi-square test of independence. The analysis was carried out in statistical software R [14].

Result and discussion

Characterization of nanoparticles

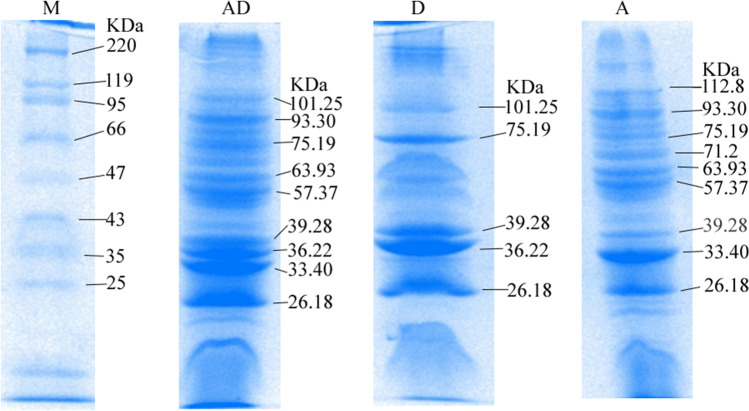

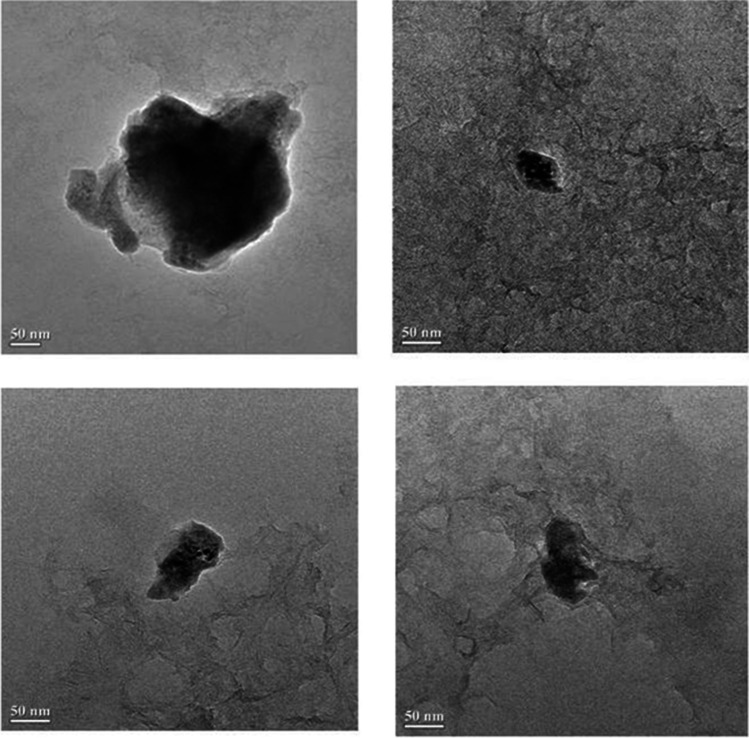

The present study was undertaken with a view to study the immunogenicity of aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles adjuvanted bivalent outer-membrane protein [Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D)] based vaccine for IgG response against P. multocida capsular types A and D. The SDS-PAGE profile of nanoparticle-OMP conjugate has revealed that there was no significant loss of immunogenic proteins during conjugation (Fig. 1). The transmission electron microscopy revealed that the size of Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) was in the range of 125 to 130 nm (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Coomassie brilliant blue stained SDS-PAGE (12%) profile of outer membrane proteins of P. multocida of different capsular type along with standard molecular weight marker. Lane M: molecular marker (14–220 kDa); lane AD: Al(OH)3NP-OMP (A + D); lane D: OMP of P. multocida capsular type D; lane A: OMP of P. multocida capsular type A

Fig. 2.

Transmission electron micrograph of Al(OH)3NP-OMP (A + D)

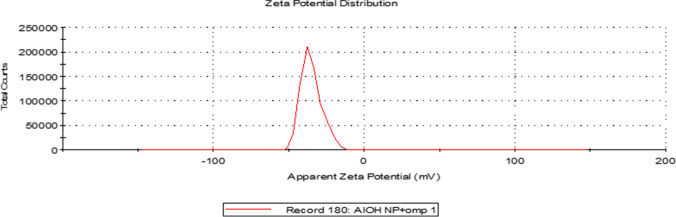

The synthesized Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D)–based vaccine was found to be stable in aqueous solution as evidenced by its zeta potential of − 35 mV (Fig. 3). The total amount of protein that could be loaded into 1 mg of Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D)–based vaccine was found to be 22.4 ± 0.56 μg. In the present study, two different types of vaccine were prepared, viz. aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles adjuvanted bivalent outer-membrane protein [Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D)]–based vaccine and aluminum hydroxide microparticles adjuvanted bivalent bacterin [Al(OH)3MP-Bacterin (A + D)]–based vaccine.

Fig. 3.

Zeta potential of Al(OH)3NP-OMP (A + D) as determined by DLS

Serum IgG response against P. multocida capsular type A and D

The IgG response against P. multocida capsular types A and D were evaluated separately in the mice model where the aluminum hydroxide microparticle adjuvanted bacterin vaccine (capsular type A and D) was taken as a control vaccine.

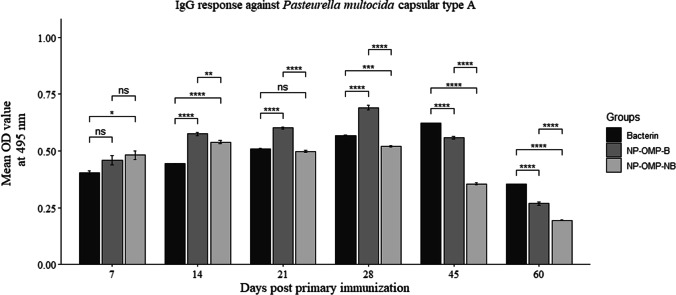

IgG response against P. multocida (capsular type A)

The IgG response of the Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) vaccine (with booster) was found to be significantly higher than the bacterin vaccine up to 28 dppi after which the fall in the IgG response was observed. On the other hand, the IgG response against bacterin vaccine reached the peak at 45 dppi where the IgG level was found to be significantly higher than that of Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) vaccine. The group that was immunized with Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) vaccine without booster immunization showed significant fall in antibody response after 14 dppi (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

IgG response of two vaccines viz. aluminum hydroxide nanoparticle + OMP (A + D) with booster dose (NP-OMP-B) and without booster dose (NP-OMP-NB) and bacterin vaccine against P. multocida capsular type A. ns: p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001

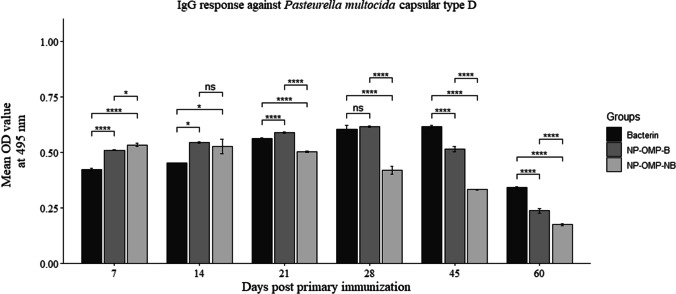

IgG response against P. multocida (capsular type D)

The immune kinetics of IgG against P. multocida (capsular type D) showed similar trend as that of P. multocida capsular type A showing the peak at 28 and 45 dppi for the vaccines Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) and bacterin respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

IgG response of two vaccines viz. aluminum hydroxide nanoparticle + OMP (A + D) with booster dose (NP-OMP-B) and without booster dose (NP-OMP-NB) and bacterin vaccine against P. multocida capsular type D. ns: p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001

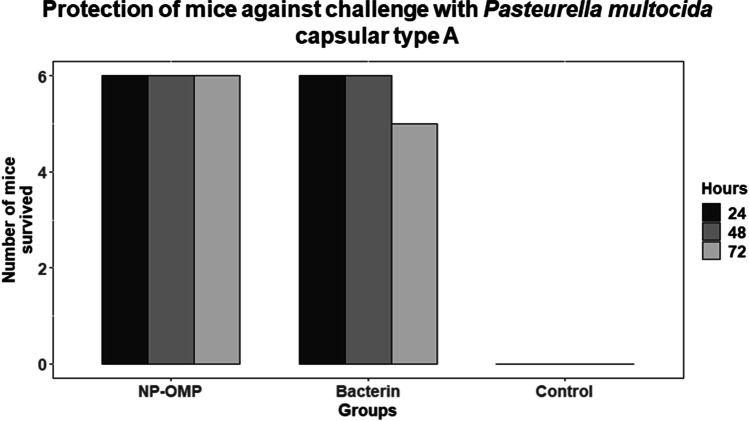

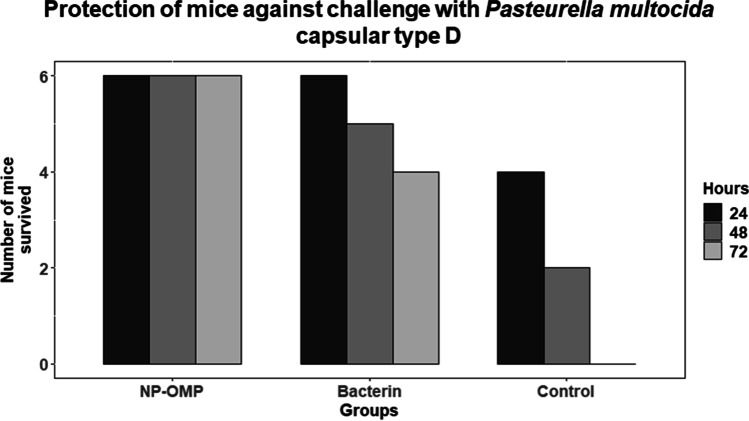

Protection against homologous challenge

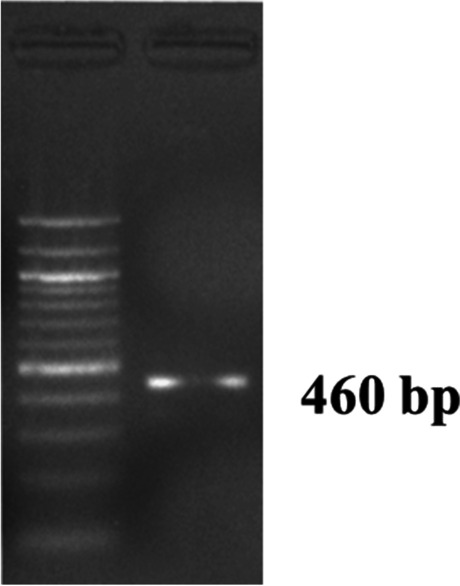

As in the earlier experiment (animal experiment I), the Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) and bacterin vaccine (with booster) showed the peak on 28 and 45 dppi respectively; hence, they were challenged at 28 and 45 dppi respectively in animal experiment II. The Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) vaccine elicited 100% protection against the challenge with virulent P. multocida capsular type A and D with the dose rate of 100 × LD50. On the other hand, the bacterin vaccine elicited 83% protection against P. multocida capsular type A (chi-sq = 5. 49, p = 0.0192) and 66% protection against capsular type D (chi-sq = 3. 38, p = 0.06) as depicted in Figs. 6 and 7 respectively. In the control group, all the mice died in 72 h when challenged with either P. multocida capsular type A or D. The mice in the control group and 3 mice in bacterin vaccine group showed clinical symptoms such as huddling together, lack of appetite, and pyrexia before death. The protection conferred by bacterin vaccine against P. multocida capsular type D was found to be statistically non-significant. Although the bacterin vaccine could elicit statistically significant protection against P. multocida capsular type A, it failed to provide 100% protection. The organisms were isolated from the liver, lung, and spleen of the dead mice. The isolated organisms were confirmed by P. multocida specific PCR and capsular type specific PCR (Figs. 8, 9, and 10). We could not isolate P. multocida from the sacrificed mice that withstood the challenge.

Fig. 6.

Survival of mice against the challenge of P. multocida capsular type A (NP-OMP: aluminum hydroxide nanoparticle + OMP (A + D))

Fig. 7.

Survival of mice against the challenge of P. multocida capsular type D (NP-OMP: aluminum hydroxide nanoparticle + OMP (A + D))

Fig. 8.

Pasteurella multocida species-specific PCR for detection of KMT1 gene of 460 bp in Agarose gel electrophoresis along with 100 bp DNA ladder

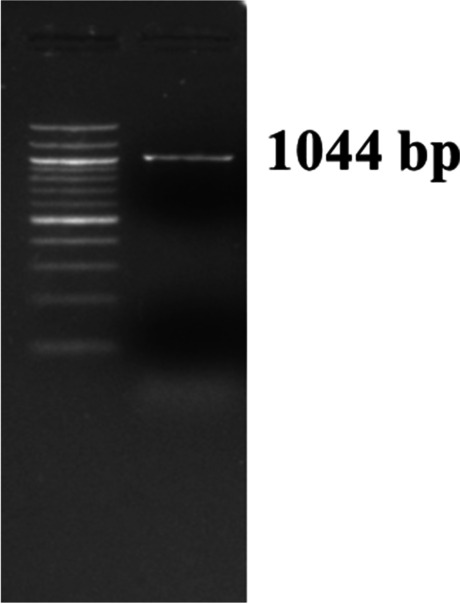

Fig. 9.

Pasteurella multocida capsular type A specific PCR showing an amplified product of 1044 bp in agarose gel electrophoresis along with 100 bp DNA ladder

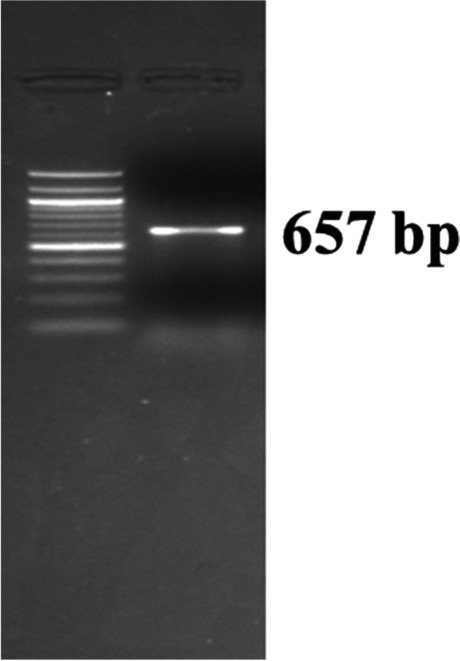

Fig. 10.

Pasteurella multocida capsular type D specific PCR showing an amplified product of 657 bp in agarose gel electrophoresis

Discussion

The immunogenicity and protective potential of OMP of P. multocida was first demonstrated by Lu et al. [4] in mice and rabbits. Pati et al. [3] demonstrated the immuno-protective potential of whole OMP of P. multocida capsular type B (P52 strain) against homologous challenge in buffalo calves. They reported 100% protection in OMP vaccinated animals on the other hand group of animals that were immunized with commercial vaccine could elicit only 66% protection in buffalo calves. The P. multocida causes swine pasteurellosis in pigs and it is specifically caused by capsular type A and D. Shyam et al. [15] reported that the antibody response of group of mice immunized with bivalent OMP (OMP obtained from capsular type A and D) against P. multocida capsular type A or D was higher than the group immunized with OMP of P52 strain (capsular type B) that was due to difference in the protein profile of major immunogenic proteins. Calcium phosphate nanoparticles and saponine conjugated to recombinant protein omp87 of P. multocida serotype B:2 has been demonstrated to be equivalent in terms of humoral immune response and the workers suggested that the calcium phosphate nanoparticle could replace saponine as an adjuvant [5].

In the present study, OMP from the capsular types A and D of P. multocida was extracted following the methods described by Choi- Kim et al. [10]. The OMPs of both the capsular types were adsorbed on aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles (Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D)) and the immunogenicity was tested in mice. The Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) was found to elicit 100% protection in mice against the homologous challenge while the bacterin vaccine could not elicit full protection.

The antigen presenting cells play an important role in induction of immune response through the internalization of antigen. Li et al. [8] have shown that macrophages and dendritic cells can more efficiently internalize the antigens conjugated with aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles than their microparticle counterpart. The easy uptake of antigens conjugated with nanoparticles by antigen presenting cells (APCs) have been reported by several other workers [16–18]. The antigens conjugated with nanoparticles of size less than 245 nm are internalized by APCs through receptors of clatherin, caveolin and scavenger and pinocytosis while those of size more than 245 nm follow the receptor independent pathway of phagocytosis. In addition, the nanoparticles also influence all the steps of maturation of dendritic cells. The nanoparticles have been reported to induce the expression of maturation markers of dendritic cells in vitro that was dependent on their size [19]. The three different pathways have been reviewed by Jia et al. [19] that are used by nanoparticles to stimulate immune response that are 1) efficient binding of nanoparticles to extracellular membrane receptors such as clatherin, 2) interference of intracellular pathway by the nanoparticles upon binding the extracellular receptors, 3) stimulation of generation of exosomes by the nanoparticles that probably can enhance the uptake of nanoparticles by DCs.

The important issue of the most of the nanoparticles is the aggregation during storage that converts the nanoparticles into a larger particle and causing lowering of its efficacy that is due to lack of stability of nanoparticles that is because of their higher surface area to volume ratio than their macroparticle counterparts [20]. The stability of nanoparticles depends on their electric charge. Higher zeta potential of the particles prevents aggregation due to electric repulsion and lower zeta potential leads to attractive forces to dominate. The zeta potential of —30 mV is considered optimum for good stability of nanoparticles [21]. In the present study, the zeta potential was found to be more than —35 mV indicating the good stability of the nanoparticles in aqueous solution.

In the present study, the Al(OH)3NP-OMP(A + D) vaccine appeared to be more efficient in stimulating humoral immune response than the bacterin vaccine up to 28 days provided the booster vaccination is accomplished. We assume that the nanoparticle and bivalent OMP based vaccine would be suitable immunogen during outbreak as they have been found to elicit rapid immune response. However, further studies in the final host (pig) are required in terms of systemic and mucosal immune response and immunoprotection.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Advanced State Biotech Hub sponsored by Department of Bio-Technology, Government of India, for providing the fund and facilities for the work. We are also thankful to the CIF of Institute of Advanced Studies in Science and Technology, Guwahati, Assam, and North Eastern Hill University, Meghalaya, for DLS and electron microscopy works respectively. We hereby declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Responsible Editor: Mariana X. Byndloss

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rajkhowa S, Shakuntala I, Pegu SR, Das RK, Das A. Detection of Pasteurella multocida isolates from local pigs of India by polymerase chain reaction and their antibiogram. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;44(7):1497–1503. doi: 10.1007/s11250-012-0094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varte Z, Dutta T, Roychoudhury P, Begum J, Chandra R (2014) Isolation, identification, characterization and antibiogram of Pasteurella multocida isolated from pigs in Mizoram with special reference to progressive atrophic rhinitis. Vet World 7. 10.14202/vetworld.2014.95-99

- 3.Pati US, Srivastava SK, Roy SC, More T. Immunogenicity of outer membrane protein of Pasteurella multocida in buffalo calves. Vet Microbiol. 1996;52(3):301–311. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(96)00066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu YS, Aguila HN, Lai WC, Pakes SP. Antibodies to outer membrane proteins but not to lipopolysaccharide inhibit pulmonary proliferation of Pasteurella multocida in mice. Infect Immun. 1991;59(4):1470–1475. doi: 10.1128/IAI.59.4.1470-1475.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamuly S, Kumar Saxena M, Saxena A, Kumar Mishra R, Jha R. Comparative evaluation of humoral immune response generated by calcium phosphate nanoparticle adjuvanted and saponin-adjuvanted recombinant outer membrane protein 87 (Omp87) of Pasteurella multocida (serotype B:2) in mice. J Nanopharmaceutics Drug Deliv. 2014;2(1):80–86. doi: 10.1166/jnd.2014.1045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindblad EB. Aluminium compounds for use in vaccines. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82(5):497–505. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta RK. Aluminum compounds as vaccine adjuvants. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1998;32(3):155–172. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(98)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X, Aldayel AM, Cui Z. Aluminum hydroxide nanoparticles show a stronger vaccine adjuvant activity than traditional aluminum hydroxide microparticles. J Controlled Release. 2014;173:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins CH, Lyne PM, Grange JM, Falkinham JO (2004) Actinobacillus, Pasteurella, Yersinia, Cardiobacterium and Francisella. In: Collins and Lyne’s microbiological methods, 8th edn. Arnold, pp 317–321

- 10.Choi-Kim K, Maheswaran SK, Felice LJ, Molitor TW. Relationship between the iron regulated outer membrane proteins and the outer membrane proteins of in vivo grown Pasteurella multocida. Vet Microbiol. 1991;28(1):75–92. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90100-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin Phenol Reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193(1):265–275. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sambrook J, Russell DW (2001) SDS-Poly-acrylamide gel electrophoresis of proteins. In: Molecular cloning, a laboratory manual, vol 3, 3rd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, pp A8.40–A8.51

- 13.Townsend KM, Boyce JD, Chung JY, Frost AJ, Adler B. Genetic organization of Pasteurella multocida cap Loci and development of a multiplex capsular PCR typing system. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(3):924–929. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.3.924-929.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.R Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing https://www.R-project.org. Accessed 19 Sept 2020

- 15.Shyam S, Tamuly S, Sharma RK, Singh RJ, Borah P (2022) Protective efficacy of calcium phosphate nanoparticle adsorbed bivalent subunit vaccine of pasteurella multocida against homologous challenge in mice. Indian J Anim Res. 10.18805/IJAR.B-4798

- 16.Fifis T, Gamvrellis A, Crimeen-Irwin B, et al. Size-dependent immunogenicity: therapeutic and protective properties of nano-vaccines against tumors. J Immunol. 2004;173(5):3148–3154. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Q, Mitchell AR, Johnson SL, Wagner-Bartak C, Morcol T, Bell SJ. Calcium phosphate nanoparticle adjuvant. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7(6):899–903. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.6.899-903.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He Q, Mitchell A, Morcol T, Bell SJD. Calcium phosphate nanoparticles induce mucosal immunity and protection against herpes simplex virus type 2. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9(5):1021–1024. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.5.1021-1024.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia J, Zhang Y, Xin Y, Jiang C, Yan B, Zhai S (2018) Interactions between nanoparticles and dendritic cells: from the perspective of cancer immunotherapy. Front Oncol 8. 10.3389/fonc.2018.00404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Zhang W (2014) Nanoparticle aggregation: principles and modeling. In: Capco DG, Chen Y (eds) Nanomaterial: impacts on cell biology and medicine. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Springer Netherlands, p 19-43. 10.1007/978-94-017-8739-0_2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Samimi S, Maghsoudnia N, Eftekhari RB, Dorkoosh F (2019) Chapter 3 - Lipid-based nanoparticles for drug delivery systems. In: Mohapatra SS, Ranjan S, Dasgupta N, Mishra RK, Thomas S, eds. Characterization and biology of nanomaterials for drug delivery. Micro and Nano Technologies. Elsevier, p 47–76. 10.1016/B978-0-12-814031-4.00003-9