Abstract

Escherichia coli are gut commensal bacteria and opportunistic pathogens, and the emergence of antimicrobial resistance threatens the safety of the food chain. To know the E. coli strains circulating in the Brazilian poultry sector is important since the country corresponds to a significant chicken meat production. Thus, we analyzed 90 publicly genomes available in a database using web-based tools. Genomic analysis revealed that sul alleles were the most detected resistance genes, followed by aadA, blaCTX-M, and dfrA. Plasmids of the IncF family were important, followed by IncI1-Iα, Col-like, and p0111. Genes of specific metabolic pathways that contribute to virulence (terC and gad) were predominant, followed by sitA, traT, and iss. Additionally, pap, usp, vat, sfa/foc, ibeA, cnf1, eae, and sat were also predicted. In this regard, 11 E. coli were characterized as avian pathogenic E. coli and one as atypical enteropathogenic E. coli. Phylogenetic analysis confirmed the predominant occurrence of B1 but also A, D, B2, F, E, G, C, and Clade I phylogroups, whereas international clones ST38, ST73, ST117, ST155, and ST224 were predicted among 53 different sequence types identified. Serotypes O6:H1 and:H25 were prevalent, and fimH31 and fimH32 were the most representatives among the 36 FimH types detected. Finally, single nucleotide polymorphisms-based phylogenetic analysis confirmed high genomic diversity among E. coli strains. While international E. coli clones have adapted to the Brazilian poultry sector, the virulome background of these strains support a pathogenic potential to humans and animals, with lineages carrying resistance genes that can lead to hard-to-treat infections.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-022-00799-x.

Keywords: Food-producing animals, Antimicrobial resistance, Virulence, WGS

Introduction

Pathogenic bacteria represent a significant threat to public health, especially those causing hard-to-treat infections due to antimicrobial resistance [1]. Escherichia coli is one of the most studied microorganism since it is part of the gastrointestinal microbiota of humans and animals and is also a frequent cause of significant infections [2, 3]. The discrimination between pathogenic and commensal E. coli strains is sometimes hard to achieve since the virulence of the first is suggested as a derivative of the commensal lifestyle, but both lineages differ with regard to their set of virulence factors [4]. Additionally, antimicrobial resistance genes are found in both commensal and pathogenic bacteria isolated from humans and animals due to their great capacity to acquire and accumulate antimicrobial resistance genes [5, 6].

All this exposed brings light to the One Health debate and the role of both humans and animals in the persistence and transmission of bacteria and genes. In recent years, the identification of such factors has been increasingly performed by the employment of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) in order to search for specific genes or regions often related to pathogenic and resistant bacteria [1, 6]. Since Brazil is still one of the most important exporters of chicken meat to the entire world, it is crucial to increase the knowledge about the genomic features associated to antimicrobial resistance and virulence of the E. coli present in this food sector in the country. Hence, we performed a genomic comparison and analysis of the E. coli isolated from poultry in Brazil in order to know about the lineages, the virulence, and the antimicrobial resistance profile of those bacteria.

Material and methods

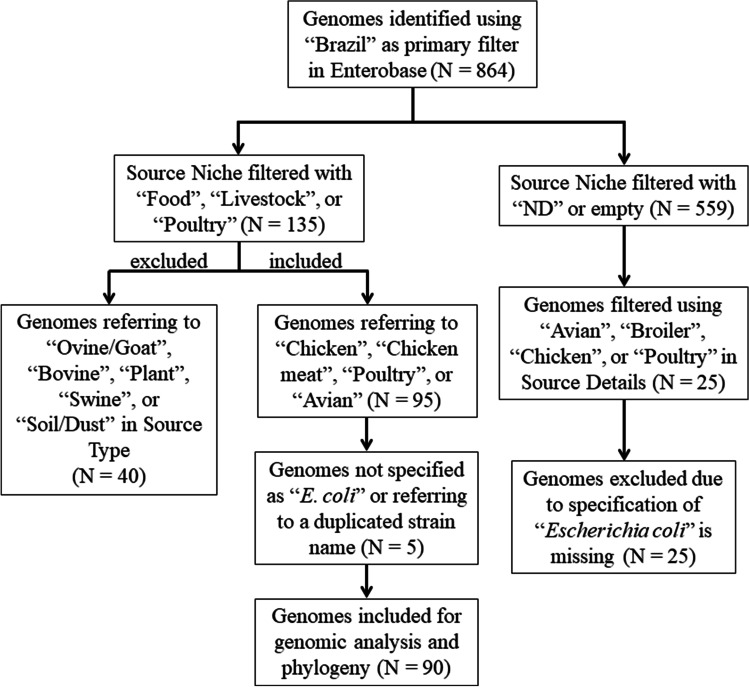

To perform the genomic comparison and analysis of the E. coli isolated from the Brazilian poultry sector, we investigated the WGS submitted to the official database curator of this species, the EnteroBase website (https://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/). The search for the E. coli genomes submitted to EnteroBase was performed on August 26, 2021, using the filter “Brazil” in the field “Country.” The released entries were downloaded and turned into a Microsoft Office Excel® spreadsheet file, and a screening was carried out filtering the field “Source niche.” In order to assure that we would study all the possible genome entries in EnteroBase following our criteria, we also screened the field “Source niche” with no specified term (“ND” or empty). With the aim of not occasionally analyzing other species such as Escherichia fergusonii, Shigella sonnei, or Shigella flexneri, only assemblies expressly referring to Escherichia coli were chosen for subsequent analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the detailed search process for selecting for the genomes of E. coli obtained from the Brazilian poultry sector from EnteroBase results

The selected assembled entries were submitted to the web-based tools ClermonTyping, SerotypeFinder 2.0, FimTyper 1.0, PathogenFinder 1.1, VirulenceFinder 2.0, ResFinder 4.1, and PlasmidFinder 2.1 with the purpose of identifying phylogenetic groups, serotypes, FimH type, potential for human pathogenicity based on a set of proteins, virulence genes, resistance genes, and plasmid replicons, respectively. The ClermonTyping tool is available at the Infection, Antimicrobials, Modelling, Evolution website (IAME, http://clermontyping.iame-research.center/index.php), while the other six abovementioned tools are available at the Center for Genomic Epidemiology website (CGE, https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/). Default parameters were used for ClermonTyping, FimTyper 1.0, VirulenceFinder 2.0, ResFinder 4.1, and PlasmidFinder 2.1, while SerotypeFinder 2.0 was launched using threshold for %ID = 90%, and minimum length = 60%, and PathogenFinder 1.1 was used by selecting “gammaproteobacteria” as the phylum/class of organism.

A phylogenetic analysis was further performed for all genomes using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and hierarchical clustering of core genome MLST (HierCC) based on 2513 core genomic loci [7]. For SNP analysis, assemblies were mapped to the reference strain Ecol_517, a random complete genome from an E. coli isolated in 2011 from human in Brazil (EnteroBase barcode ESC_FA9974AA). HierCC designates thirteen categories: HC0, HC2, HC5, HC10, HC20, HC50, HC100, HC200, HC400, HC1100, HC1500, HC2000, and HC2350. The HC0 corresponds to indistinguishable E. coli, HC1100 corresponds to a core genome MLST (cgMLST) lineage, and HC2350 to the Escherichia species. For example, genomes designated to the same HC5 differ by ≤ 5 core genomic alleles and accordingly are extremely similar. Results for sequence type (ST) and clonal complex (CC) were recovered directly from EnteroBase website. Tree topology visualization and annotation were performed with iTol v.6 (https://itol.embl.de/).

Results and discussion

The screening returned 864 released genomes submitted to EnteroBase, but only 90 met the criteria established to assure of studying only genomes belonging to E. coli isolated from the poultry sector in Brazil. Two genomes referred to a probably duplicated isolate since both presented the same strain name and were collected by the same research group in the same year (EnteroBase barcodes ESC_OA5589AA and ESC_PA5337AA); thus, the second entry was excluded from downstream applications (Fig. 1).

Information about coverage, N50, genome length, number of contigs > = 200 bp, low-quality bases, strain source type and details, year and region of collection, laboratory responsible for contact, and the respective EnteroBase barcode and assembly barcode were described in supplementary Supplemental Table 1. The averaged coverage for the 90 included genomes was 172.8 × (min. = 23; max. = 667); the averaged N50 value was 118,845 bases (min. = 19,165; max. = 322,808); the averaged genome length was 5,155,671 bases (min. = 4,473,174; max. = 5,920,552); the averaged contigs number was 201 (min. = 76; max. = 614); and the averaged low-quality bases was 49,960 bases (min. = 3,886; max. = 236,019).

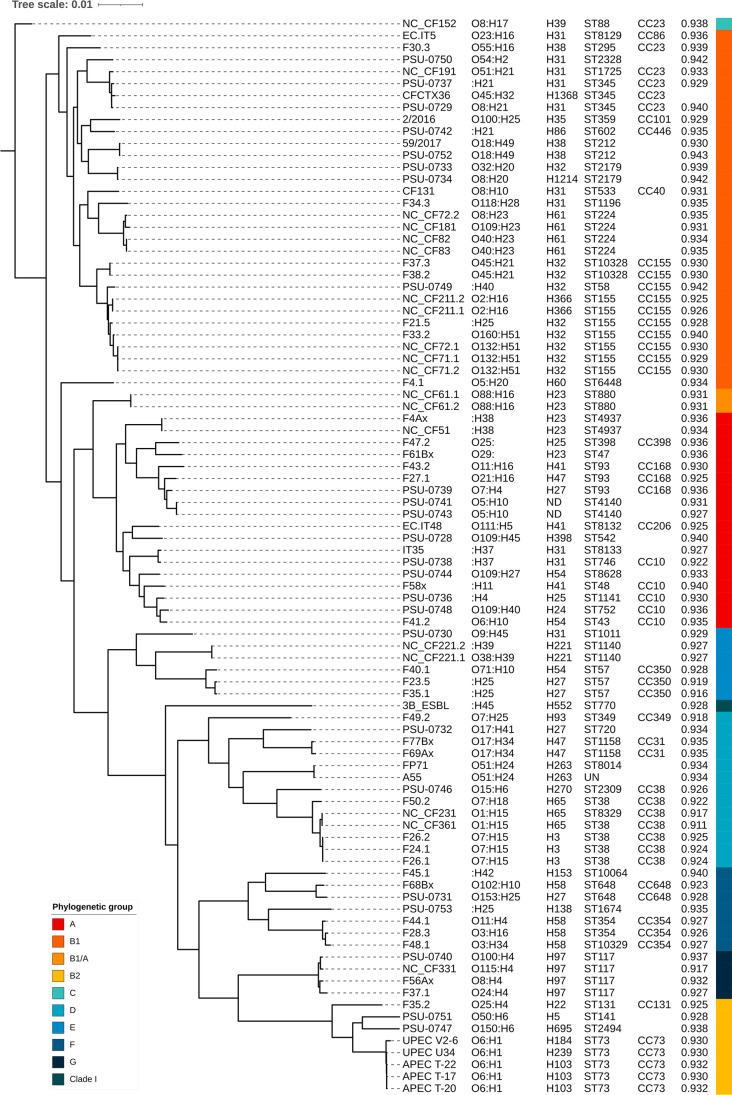

Figure 2 summarizes the characteristics for all analyzed genomes included in the phylogenetic tree. The 90 E. coli were considered potentially pathogenic to humans, with probabilities ranging from 0.911 to 0.943. In respect to sequence types, 53 different STs were detected, plus one genome with unknown ST; seven genomes were assigned as ST/CC 155/155, five as ST/CC 38/38, and five as ST/CC 73/73. Two E. coli were assigned as ST 648, and one as ST 131. In regard to serotypes, 67 O:H combinations were detected, and five genomes were identified as belonging to O6:H1 and four to the:H25 type. The other ST and O:H combinations were identified in less than five or four genomes, respectively. Typing E. coli according to the phylogenetic groups revealed the majority of them as predictive commensal, with distribution of phylogroups as B1 (n = 30, 33.3%), A (n = 18, 20.0%), D (n = 13, 14.4%), B2 (n = 8, 8.9%), F (n = 7, 7.8%), E (n = 6, 6.7%), G (n = 4, 4.4%), C (n = 1, 1.1%), and Clade I (n = 1, 1.1%); two genomes (2.2%) returned a B1/A result. Thirty-six FimH types were detected, but fimH31 and fimH32 were the most identified, present in 10 (11.1%) and nine assemblies (10.0%), respectively. Interestingly, some genomes presented features like ST, FimH type, and cephalosporinase production which are also found in E. coli causing bloodstream infections in humans [8] and stands out for the high similarity between those isolates and the ones obtained from broilers [9]. Examples are E. coli F50.2 and NC_CF361 (ST 38-fimH65-blaCTX-M-55), NC_CF152 (ST 88-fimH39-blaCTX-M-8), F43.2 (ST 88-fimH41-blaCTX-M-2), F37.1, F56Ax and NC_CF331 (ST 117-fimH97-blaCTX-M-55), F35.2 (ST 131-fimH22-blaCTX-M-55), and F28.3 and F44.1 (ST 354-fimH58-blaCMY-2 or blaCTX-M-14). All these results represent that several types of potentially human pathogenic E. coli lineages circulate through the poultry sector in Brazil.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic three using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the 90 selected genomes of E. coli obtained from the Brazilian poultry sector. Serotype, FimH type, MLST results (ST, sequence type; CC, clonal complex), potential for human pathogenicity, and phylogenetic group (lineages colored) are indicated for each genome. ND, fimH not detected. UN, unknown ST for strain A55

The VirulenceFinder 2.0 tool detected 61 genes encompassing fimbriae, cytotoxins, iron acquisition systems, elements of secretion systems, regulator or metabolic proteins, and bacterium survival protein (Fig. 3). The terC gene, which codifies for a tellurium ion resistance protein, was the only detected in all 90 genomes, and gad, responsible for the glutamate decarboxylase enzyme, was identified in 81 (90.0%). Other virulence genes significantly identified were iss (in 68.9% of analyzed genomes), responsible for the bacterial increased serum survival, sitA (71.1%), which codifies for an iron/manganese transport protein, and the traT (71.1%) and ompT (65.6%) genes, which code for protectins. Other important genes that codify for virulence factors were also identified such as those implicated in iron uptake by bacteria (iutA (in 46.7% of genomes), iucC (45.6%), chuA (43.3%), iroN (40.0%), and fyuA (26.7%)); genes part of the system for polysaccharide capsule production (kpsE and kpsM II (31.1% each)); and the hlyF gene (43.3%), which codifies for the hemolysin F. The hra gene, which codifies for a heat-resistant agglutinin, significantly associated to urinary tract infection and bacteremia in humans [10, 11], and the lpfA gene, coding for the long polar fimbriae, is important for adhesion of pathogenic E. coli [12, 13], where detected in 56.7% and 46.7%, respectively. Since the typical avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) are characterized as possessing genes for hemolysin, colicin, increased serum survival protein, type I fimbriae, temperature-sensitive hemagglutinin, and siderophore [14], 11 (12.2%) of the analyzed genomes represent APEC (EC.IT5, F23.5, F35.1, F56Ax, NC_CF152, NC_CF211.1, NC_CF211.2, NC_CF331, PSU-0731, PSU-0747, and PSU-0748). It is interesting to note that the genes eae and tir, which codify for intimin and its receptor in enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), were additionally detected in the genome of PSU-0748, characterizing it as an atypical EPEC as well. Curiously, no stx gene was identified in any of the 90 analyzed genomes, providing that in general the E. coli found in the Brazilian poultry sector are not relevant for the serious illness that can be triggered by the production of Shiga toxin.

Fig. 3.

Virulence genes detected in the 90 genomes of E. coli obtained from the Brazilian poultry sector based on the VirulenceFinder 2.0 tool

Overall, tellurium resistance seems to be extremely important to E. coli inhabiting the poultry sector in Brazil probably because of environmental contamination with industrial waste [15]. Depending on the area, tellurium is a scarce component, but it can reach profuse levels where the anthropogenic industrial activity is high, causing environmental pollution and microbial ecology impairment [16]. Besides, tellurium can be found in high concentrations in nuts and seeds, which can be used to feed chickens [17]. However, it seems to be also important to bacteria in general not because of tellurium resistance per se but for the reason that it also confers resistance to phages and pore-forming colicins [18]. The enzyme glutamate decarboxylase codified by the gad gene allows bacteria to survive in acidic environments, such as the urinary tract, the stomach, and parts of the distal gut of mammalians, as well as phagolysosomes [19, 20]. In fact, gad is one of the most detected virulence gene in E. coli isolated from food-producing animals [21]. The iss, sitA, traT, and ompT genes were also detected in considerable percentages, all of them classically associated to pathogenicity, as already reported for E. coli from poultry [22–25]. Despite all these genes are often related to virulence traits, as so as those responsible for iron acquisition, polysaccharide capsule formation, hemolysin, or fimbrial adhesin production, it has been proposed that they also serve for intestinal colonization and persistence in both humans and animals [2].

Other notable virulence genes were detected in few accounts, as the ones responsible for autotransporter toxins (vat, 12.2%; sat, 1.1%), for the uropathogenic-specific protein (usp, 12.2%), for fimbrial components (yfcV, 16.7%; papC, 16.7%; focC/sfaE, 6.7%; afaD, 4.4%), and for invasion of brain endothelial cells (ibeA, 5.6%). Genome analysis of commensal E. coli in bovine have revealed that such lineages are the source of pathogenic strains to humans [26], and the same could be expected in respect to E. coli coming from the poultry sector.

The ResFinder 4.1 tool detected 47 different genes/alleles conferring resistance to aminoglycosides (13 genes/alleles), β-lactams (8 genes/alleles), colistin (2 genes), fosfomycin (2 alleles), lincosamide (1 gene), phenicols (3 genes), quinolones (4 genes), sulfonamides (3 genes), tetracyclines (3 genes), or trimethoprim (8 alleles) (Fig. 4). The aminoglycoside resistance gene aadA1 was detected in 46 (51.1%) E. coli genomes, alleles of the trimethoprim resistance gene dfrA were detected in 41 (45.6%), the sulfonamide resistance genes sul1 and sul2 were identified in 37 (41.1%) and 42 (46.7%), respectively, and the β-lactam resistance gene blaTEM-1B in 31 (34.4%) genomes. Genes that code for resistance to third-generation cephalosporins (blaCTX-M and blaCMY) were identified in 61 (67.8%) screened genomes. Thirteen assembled sequences returned genes that code for resistance to non-specific antimicrobials such as the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance gene mdf(A) and/or the hydrogen peroxide resistance operon sitABCD.

Fig. 4.

Resistance genes detected in the 90 genomes of E. coli obtained from the Brazilian poultry sector based on the ResFinder 4.1 tool

The five main genes identified in the E. coli genomes analyzed are usually found in genetic mobile elements, and this fact suggests that these elements circulate through different E. coli in the sector. In respect to the detected bla genes that code for resistance to third-generation cephalosporins, blaCTX-M-55 was the most common, present in 24/61 (39.3%) genomes, followed by blaCTX-M-2 (16/61, 26.2%) and blaCTX-M-8 (14/61, 22.9%). Two assemblies presented both blaCTX-M-8 and blaCMY-2, two presented blaCTX-M-8 and blaCTX-M-55, and one last presented blaCTX-M-2 and blaCMY-2. The blaCTX-M-15 gene was detected in only one genome, which was unexpectedly since this blaCTX-M variant is the most worldwide spread [27]. Both blaCTX-M-2 and blaCTX-M-8 were always common in food-producing animals in Brazil, but studies have been reported blaCTX-M-55 as an important variant [28–30], which suggests that it could be displacing blaCTX-M-15 from the field. Actually, making a temporal correlation, CTX-M-2 was prevalent between the years 2012 and 2014, with punctual identification of blaCMY-2, blaCTX-M-15, and blaCTX-M-55. In genomes of E. coli collected in 2016, CTX-M-8 represented 45.8% of the alleles, but CTX-M-55 accounted for more than 30.0% of them, while CTX-M-2 corresponded for less than 10.0%. In both years 2017 and 2019, blaCTX-M-55 was already the prevalent allele, accounting for 80.0% and 42.3%, respectively, while CTX-M-2 returned to represent a significant amount of 30.8% in 2019 (data not shown). We recognize that the data collected by us is scarce and lacking proper statistical analysis in order to infer about the CTX-M epidemiology in E. coli isolated from the Brazilian poultry sector, but they strongly suggest the increase in the detection of the blaCTX-M-55 gene.

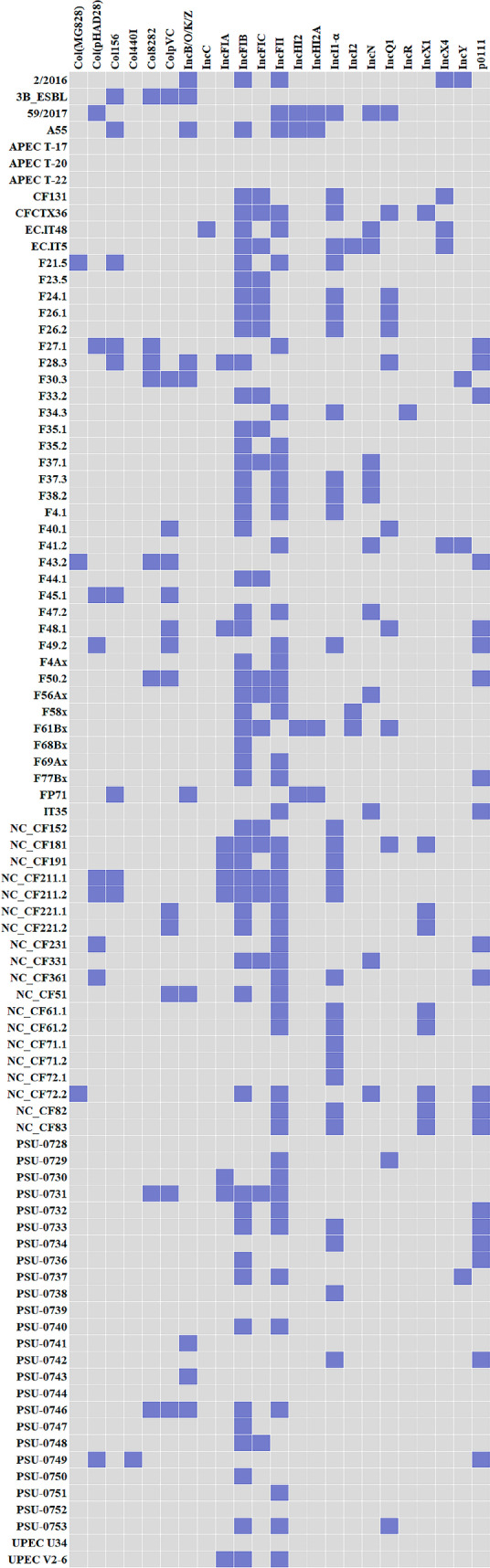

According to the PlasmidFinder 2.1 tool, 22 different plasmids were identified among 82 E. coli genomes; in eight assembled sequences, no plasmid was detected (Fig. 5). As expected, IncFII and IncFIB were prevalent, detected in 49/82 (59.8%) and 53/82 (64.6%) genomes, respectively, followed by IncI1-Iα in 30/82 (36.6%), IncFIC in 21/82 (25.6%), and p0111 in 20/82 (24.4%) genomes; six subtypes of Col plasmids were identified in 25/82 (30.5%), mainly ColpVC.

Fig. 5.

Plasmids detected in the 90 genomes of E. coli obtained from the Brazilian poultry sector based on the PlasmidFinder 2.1 tool

IncF are the most found plasmids in E. coli and were essential for the evolution of this species because of its relation to antimicrobial resistance genes [31–33]. In fact, only 3 (4.4%) of the 68 E. coli genomes that carry IncF plasmids do not harbor any antimicrobial resistance genes, which suggest a strong association between this type of plasmid and the resistance to relevant antimicrobials. Other feature of IncF plasmids that facilitate their maintenance in the bacterial genome is the presence of addiction systems [34]. All the exposed support the expected prevalence of IncF plasmids detected in the present study. Additionally, IncI1-Iα plasmids are also implicated in virulence phenotypes and antimicrobial resistance, especially to third-generation cephalosporins in E. coli isolated from a sort of hosts and geographical regions [35]. These attributes evidence the importance and abundance of this type of plasmid among the genomes screened. In fact, blaCTX-M/CMY genes were also identified in 26 (86.7%) of the 30 E. coli genomes that presented the IncI1-Iα plasmid. In regard to p0111 plasmids, they were also implicated in the carriage of antimicrobial resistance genes in E. coli recovered from both humans and chickens [36, 37]. This type represented the third most detected plasmid after the IncF and IncI1-Iα ones in the present study, and all genomes in it was identified also presented at least one antimicrobial resistance gene (Figs. 4 and 5).

SNPs and HierCC integrated into EnteroBase were performed to investigate the phylogenetic relatedness of the selected E. coli genomes (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table 2). In this respect, only one pair and one trio of them were considered indistinguishable: NC_CF221.1 and NC_CF221.2 (HC0_67590), and F24.1, F26.1, and F26.2 (HC0_117299). The following pairs were also extremely similar, i.e., up to 10 alleles of difference between genomes: NC_CF71.1 and NC_CF71.2 (HC2_67585), NC_CF83 and NC_CF82 (HC2_67589), NC_CF211.1 and NC_CF211.2 (HC2_67597), PSU-0733 and PSU-0734 (HC2_68548), NC_CF61.1 and NC_CF61.2 (HC5_67601), F37.3 and F38.2 (HC5_117293), PSU-0741 and PSU-0743 (HC10_75953), and APEC T-17 and APEC T-20 (HC10_124682) (Supplemental Table 2). All these pairs comprehend E. coli seemingly obtained by the same research groups in the same years (Supplemental Table S1), which could mean that they represent clones or clonally related isolates obtained from the same sort samples in each study. However, since we do not have any information about them (there is no information about publication of the screened genomes in EnteroBase), we can only speculate about this topic.

On the other hand, the SNP tree (Fig. 2) shows ten groups of E. coli genomes very related (total branch lengths of 0.0000094 to 0.0041 nucleotide substitutions per site), even with HierCC clusters assignments ranging from HC20 to HC1100, and isolates obtained by different research groups and years. Assemblies of E. coli A55 and FP71, both bacteria recovered from livestock avian by the same research group from the University of São Paulo (FMVZ-USP) but in different years, were grouped in SNP tree and share the same HC20_59164. F4Ax recovered from chicken cloacae in 2014 by our group (FAMERP), clustered in SNP tree with E. coli NC_CF51, and collected in 2016 from a chicken meat by the FDA Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN), and both were assigned to the same HC20_67586. PSU-0752, collected by the CFSAN from poultry in 2012, and the E. coli 59/2017, obtained from a chicken carcass by researchers from the Federal University of Paraiba (LAPOA-UFPB) in 2017, are clustered and assigned to the same HC100_2302. Both NC_CF231 and NC_CF361, collected by the CFSAN from chicken meats in 2016, and F24.1, F26.1, and F26.2, isolated from chicken carcasses in 2019 by investigators from the State University of Londrina (UEL), were all clustered and assigned to the same HC100_97. Genome of CFCTX36, collected by our group from a chicken meat sample in 2014, and PSU_0729, isolated by CFSAN from poultry in 2012, were very similar and were assigned to the same HC200_168. A sixth group comprised E. coli collected by CFSAN from chicken meats in 2016 (NC_CF71.1, NC_CF71.2, and NC_CF72.1), and the E. coli F33.2, obtained from chicken carcasses in 2019 by the research group from UEL, all belonging to HC200_1157. The group formed by PSU-0740 (poultry/2012/CFSAN), NC_CF331 (chicken meat/2016/CFSAN), F37.1 (chicken carcass/2019/UEL), and F56Ax (chicken cloacal swab/2014/FAMERP), all sharing the same HC200_50, was notable because we have the information that the last two E. coli were obtained from distant geographical regions (more than 400 km) with time-lapse of 5 years between collections. The eighth pair comprised PSU-0748 and F41.2, collected from poultry in 2012 by the CFSAN and from chicken carcass by people from UEL in 2019, respectively, both assigned to HC400_13 and arranged together in the SNP tree. PSU-0731 (poultry/2012/CFSAN) and F68Bx (cloacal swab/2014/FAMERP) are very similar according to the SNP tree and were assigned to HC400_1398. Finally, PSU-0738 (poultry/2012/CFSAN) and IT35 (2017/FMVZ-USP) were assigned to HC1100_13 (the same cgMLST) and are extremely similar according to the SNP analysis (total distance of 119 substitutions per 100,000 nucleotide) (Fig. 2, Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). The exposed indicates a significant similarity among the E. coli genomes within each mentioned cluster existent in different period and geographical location, which suggests the persistence and circulation of those lineages among poultry in Brazil. This all might be attributed to the use of similar matrices or by the trade in food animals and food products [38], but we do not have the tools needed for answering this question in the present study.

In our point of view, this work has two central limitations. First, probably not all whole sequenced E. coli isolated from poultry in Brazil had their genomes submitted to EnteroBase, and not all the submitted ones have all the info fields correctly filled. Considering the 864 genomes filtered in EnteroBase for this study, 704 certainly refer to genome of bacteria not coming from the poultry sector but from other sources. Only 25 others surely corresponding to genome of bacteria isolated from the Brazilian poultry sector could not be included because there was no mention of “Escherichia coli” as the species related to the assembly. This stands for the importance of correctly providing information of each isolate/genome/submission in databases.

A second important limitation of this study is that most of genomes deposited in EnteroBase are from bacteria collected by the same research groups and probably part of the same study and type of samples. This could have produced a bias in the genetic features found (typing, virulence, antimicrobial resistance, and plasmids) unlike it would be verified if we could have performed a randomized collection of data. For example, most sequenced isolates may be related to studies leading to specific characteristics such as resistance to third-generation cephalosporins, resulting in 2/3 of analyzed genomes presenting blaCTX-M and/or blaCMY-2 genes. However, the elevated presence of blaCTX-M/CMY and the scarcity of carbapenemase genes in E. coli from poultry around the world is well known [39, 40], which could also represent the reality of our country.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the poultry sector in Brazil is represented by a great diversity of E. coli in respect to serotype, phylogenetic groups, FimH type, and ST lineages or even considering the genetic relatedness according to the SNP diversity of them, with few clones being found in diverse geographical areas and years. However, all E. coli are considered potentially pathogenic to humans, presenting a sort of virulence genes, in case of they are having the opportunity to initiate an infection process. Furthermore, if causing an infectious event, most of the E. coli can resist the action of antimicrobials usually elected to treat such infections as third-generation cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. To know and survey the characteristics of the bacteria circulating among food-producing animals is essential for governmental strategies that are focused in reducing the risks for the human and public health. We expect that the knowledge provided by the present study could reach the responsible authorities as well as the research groups that are implicated in antimicrobial resistance through the food chain and the public health for producing a conceptual debate.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

WGS information of the 90 sequences selected for the study. Colum E (“Contig number”) stands for the number of contigs = 200 bp in size. Information about Region and/or City of isolation, as well as Details of the source are lacking for some sequence’s entries in Enterobase website. Supplementary file1 (XLSX 19 KB)

Hierarchical clustering of core-genome MLST of 90 genomes of E. coli obtained from the Brazilian poultry sector based on Enterobase website. Supplementary file2 (DOC 181 KB)

Acknowledgements

We further acknowledge all the research groups that have whole-genome sequenced the E. coli and submitted the respective reads to the EnteroBase website. Their contribution to this work was not formal but surely essential.

Author contribution

Conceptualization, Nilton Lincopan and Tiago Casella; methodology and investigation, Caroline Rodrigues da Silva, Marlon do Valle Barroso, Katia Suemi Gozi, and Herrison Fontana; formal analysis and validation, Nilton Lincopan and Tiago Casella; writing-original draft preparation, Caroline Rodrigues da Silva, Mara Corrêa Lelles Nogueira, and Tiago Casella; writing-review and editing, Mara Corrêa Lelles Nogueira, Nilton Lincopan, and Tiago Casella.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

CRS, MVB, KSG, and HF have scholarships from the Brazilian Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Responsible Editor: Tânia A. Tardelli Gomes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Liu B, Zheng D, Jin Q, Chen L, Yang J. VFDB 2019: a comparative pathogenomic platform with an interactive web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D687–D692. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denamur E, Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Gordon D. The population genetics of pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:37–54. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos S, Silva V, de LurdesEnesDapkevicius M, Caniça M, Tejedor-Junco MT, Igrejas G, et al. Escherichia coli as commensal and pathogenic bacteria among food-producing animals: health implications of extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) production. Animals. 2020;10:1–15. doi: 10.3390/ani10122239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malberg Tetzschner AM, Johnson JR, Johnston BD, Lund O, Scheutz F (2020) In silico genotyping of Escherichia coli isolates for extraintestinal virulence genes by use of whole-genome sequencing data. J Clin Microbiol 58:e01269-20. 10.1128/JCM.01269-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Suwono B, Eckmanns T, Kaspar H, Merle R, Zacher B, Kollas C, et al. Cluster analysis of resistance combinations in Escherichia coli from different human and animal populations in Germany 2014–2017. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poirel L, Madec J-Y, Lupo A, Schink A-K, Kieffer N, Nordmann P, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Spectr. 2018;6:1–27. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0026-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou Z, Alikhan N-F, Mohamed K, Fan Y, Achtman M. The EnteroBase user’s guide, with case studies on Salmonella transmissions, Yersinia pestis phylogeny, and Escherichia core genomic diversity. Genome Res. 2020;30:138–152. doi: 10.1101/gr.251678.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roer L, Johannesen TB, Hansen F, Stegger M, Tchesnokova V, Sokurenko E, et al. CHTyper, a web tool for subtyping of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli based on the fumC and fimH alleles. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:3–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00063-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roer L, Overballe-Petersen S, Hansen F, Johannesen TB, Stegger M, Bortolaia V, et al. ST131 fimH22 Escherichia coli isolate with a blaCMY-2/IncI1/ST12 plasmid obtained from a patient with bloodstream infection: highly similar to E. coli isolates of broiler origin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74:557–60. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srinivasan U, Foxman B, Marrs CF. Identification of a gene encoding heat-resistant agglutinin in Escherichia coli as a putative virulence factor in urinary tract infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:285–289. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.285-289.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson JR, Johnston B, Kuskowski MA, Nougayrede JP, Oswald E. Molecular epidemiology and phylogenetic distribution of the Escherichia coli pks genomic island. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:3906–3911. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00949-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou M, Yang Y, Wu M, Ma F, Xu Y, Deng B, et al. Role of long polar fimbriae type 1 and 2 in pathogenesis of mammary pathogenic Escherichia coli. J Dairy Sci. 2021;104:8243–8255. doi: 10.3168/jds.2021-20122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ideses D, Biran D, Gophna U, Levy-Nissenbaum O, Ron EZ. The lpf operon of invasive Escherichia coli. Int J Med Microbiol. 2005;295:227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarowska J, Futoma-Koloch B, Jama-Kmiecik A, Frej-Madrzak M, Ksiazczyk M, Bugla-Ploskonska G, et al. Virulence factors, prevalence and potential transmission of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from different sources: recent reports. Gut Pathog. 2019;11:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13099-019-0290-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maltman C, Yurkov V. Extreme environments and high-level bacterial tellurite resistance. Microorganisms. 2019;7:1–24. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7120601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vávrová S, Struhárňanská E, Turňa J, Stuchlík S (2021) Tellurium: a rare element with influence on prokaryotic and eukaryotic biological systems. Int J Mol Sci 22:5924. 10.3390/ijms22115924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Filippini T, Tancredi S, Malagoli C, Malavolti M, Bargellini A, Vescovi L, et al (2020) Dietary estimated intake of trace elements: risk assessment in an Italian population. Expo Heal 12:641–655. 10.1007/s12403-019-00324-w

- 18.Valkovicova L, Vavrova SM, Mravec J, Grones J, Turna J. Protein-protein association and cellular localization of four essential gene products encoded by tellurite resistance-conferring cluster “ter” from pathogenic Escherichia coli. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2013;104:899–911. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-0009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giovannercole F, Mérigoux C, Zamparelli C, Verzili D, Grassini G, Buckle M, et al. On the effect of alkaline pH and cofactor availability in the conformational and oligomeric state of Escherichia coli glutamate decarboxylase. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2017;30:237–246. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzw076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwan WR, Flohr NL, Multerer AR, Starkey JC. GadE regulates fliC gene transcription and motility in Escherichia coli. World J Clin Infect Dis. 2020;10:14–23. doi: 10.5495/wjcid.v10.i1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen L, Wang L, Yassin AK, Zhang J, Gong J, Qi K, et al (2018) Genetic characterization of extraintestinal Escherichia coli isolates from chicken, cow and swine. AMB Express 8:117. 10.1186/s13568-018-0646-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Bin KY, Yoon MY, Ha JS, Seo KW, Noh EB, Son SH, et al. Molecular characterization of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli from broiler chickens with colibacillosis. Poult Sci. 2020;99:1088–95. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2019.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hejair HMA, Ma J, Zhu Y, Sun M, Dong W, Zhang Y, et al. Role of outer membrane protein T in pathogenicity of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Res Vet Sci. 2017;115:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2017.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez-Siek KE, Giddings CW, Doetkott C, Johnson TJ, Nolan LK. Characterizing the APEC pathotype. Vet Res. 2005;36:241–256. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2004057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding HF, Liu BG, Gao YL, Zhong XH, Duan SS, Yuan L. Divergence of affinities, serotypes and virulence factor between CTX-M Escherichia coli and non-CTX-M producers. Poult Sci. 2018;97:980–985. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arimizu Y, Kirino Y, Sato MP, Uno K, Sato T, Gotoh Y, et al. Large-scale genome analysis of bovine commensal Escherichia coli reveals that bovine-adapted E. coli lineages are serving as evolutionary sources of the emergence of human intestinal pathogenic strains. Genome Res. 2019;29:1495–505. doi: 10.1101/gr.249268.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bevan ER, Jones AM, Hawkey PM. Global epidemiology of CTX-M β-lactamases: temporal and geographical shifts in genotype. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:2145–2155. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunha MPV, Lincopan N, Cerdeira L, Esposito F, Dropa M, Franco LS, et al. Coexistence of CTX-M-2, CTX-M-55, CMY-2, FosA3, and QnrB19 in extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli from poultry in Brazil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:1–3. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02474-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soncini JGM, Cerdeira L, Koga VL, Tizura AT, Nakazato G, Kobayashi RKT, et al. Genomic insights of high-risk clones of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolated from community infections and commercial meat in Southern Brazil. BioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2020.12.31.424884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casella T, Haenni M, Madela NK, de Andrade LK, Pradela LK, de Andrade LN, et al. Extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from chickens and chicken meat in Brazil is associated with rare and complex resistance plasmids and pandemic ST lineages. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:3293–3297. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mbelle NM, Feldman C, Osei Sekyere J, Maningi NE, Modipane L, Essack SY. Publisher correction: the resistome, mobilome, virulome and phylogenomics of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli clinical isolates from Pretoria. South Africa Sci Rep. 2020;10:1270. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58160-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irrgang A, Falgenhauer L, Fischer J, Ghosh H, Guiral E, Guerra B, et al (2017) CTX-M-15-producing E. coli isolates from food products in Germany are mainly associated with an IncF-type plasmid and belong to two predominant clonal E. coli lineages. Front Microbiol 8:2318. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Pitout JDD, Finn TJ. The evolutionary puzzle of Escherichia coli ST131. Infect Genet Evol. 2020;81:104265. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang QE, Sun J, Li L, Deng H, Liu BT, Fang LX, et al (2015) IncF plasmid diversity in multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli strains from animals in China. Front Microbiol 6:964. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Foley SL, Kaldhone PR, Ricke SC, Han J (2021) Incompatibility group I1 (IncI1) plasmids: their genetics, biology, and public health relevance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 85:e00031-20. 10.1128/mmbr.00031-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Kao CY, Chen JW, Liu TL, Yan JJ, Wu JJ. Comparative genomics of Escherichia coli sequence type 219 clones from the same patient: evolution of the IncI1 blaCMY-carrying plasmid in vivo. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang M, Jiang M, Wang Z, Chen R, Zhuge X, Dai J. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance in chicken-source phylogroup F Escherichia coli: similar populations and resistance spectrums between E coli recovered from chicken colibacillosis tissues and retail raw meats in Eastern China. Poult Sci. 2021;100:101370. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ludden C, Decano AG, Jamrozy D, Pickard D, Morris D, Parkhill J, et al (2020) Genomic surveillance of Escherichia coli ST131 identifies local expansion and serial replacement of subclones. Microb Genomics 6:e000352. 10.1099/mgen.0.000352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Lentz SAM, Adam FC, Rivas PM, Souza SN, Cupertino VML, Boff RT, et al. High levels of resistance to cephalosporins associated with the presence of extended-spectrum and AmpC β-lactamases in Escherichia coli from broilers in Southern Brazil. Microb Drug Resist. 2020;26:531–535. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2019.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jung D, Morrison BJ, Rubin JE. A review of antimicrobial resistance in imported foods. Can J Microbiol. 2022;68:1–15. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2021-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

WGS information of the 90 sequences selected for the study. Colum E (“Contig number”) stands for the number of contigs = 200 bp in size. Information about Region and/or City of isolation, as well as Details of the source are lacking for some sequence’s entries in Enterobase website. Supplementary file1 (XLSX 19 KB)

Hierarchical clustering of core-genome MLST of 90 genomes of E. coli obtained from the Brazilian poultry sector based on Enterobase website. Supplementary file2 (DOC 181 KB)

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.