Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus expresses several surface proteins that promote adherence to host cell extracellular matrix proteins, including fibronectin (Fn). Since this organism has recently been shown to be internalized by nonprofessional phagocytes, a process that typically requires high-affinity binding to host cell receptors, we investigated the role of its Fn binding proteins (FnBPs) and other surface proteins in internalization by the bovine mammary gland epithelial cell line (MAC-T). Efficient internalization of S. aureus 8325-4 required expression of FnBPs; an isogenic mutant (DU5883), not expressing FnBPs, was reduced by more than 95% in its ability to invade MAC-T cells. Moreover, D3, a synthetic peptide derived from the ligand binding domain of FnBP, inhibited the internalization of the 8325-4 strain in a dose-dependent fashion and the efficiency of staphylococcal internalization was partially correlated with Fn binding ability. Interestingly, Fn also inhibited the internalization and adherence of S. aureus 8325-4 in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast to internalization, adherence of DU5883 to MAC-T was reduced by only approximately 40%, suggesting that surface binding proteins, other than FnBPs, can mediate bacterial adherence to cells. Adherence via these proteins, however, does not necessarily result in internalization of the staphylococci. An inhibitor of protein tyrosine kinase, genistein, reduced MAC-T internalization of S. aureus by 95%, indicating a requirement for a host signal transduction system in this process. Taken together, these results indicate that S. aureus invades nonprofessional phagocytes by a mechanism requiring interaction between FnBP and the host cell, leading to signal transduction and subsequent rearrangement of the host cell cytoskeleton.

Staphylococcus aureus is the etiological agent of a wide range of infectious and toxigenic illnesses of humans and animals. Although it has many virulence factors, a key to its success as a pathogen is its ability to colonize and persist at various sites within its cadre of potential hosts. In addition to persistence in healthy hosts, this organism is well known for the ability to induce long-lasting chronic infections that resist conventional therapy. Although S. aureus is not traditionally considered to be an intracellular pathogen, it is now well documented that it can enter nonprofessional phagocytic cells such as endothelial and epithelial cells (4, 5, 6, 20, 49, 50, 53). We have been exploring the possibility that maintenance in an intracellular niche can promote long-term colonization in the host and also can play a role in maintaining chronic infections.

Previously, our laboratories reported that during its invasion cycle of bovine epithelial cells in vitro, S. aureus escapes from the endosomal vesicle, appears to multiply within the cytoplasm, and induces apoptosis (5). These steps were proposed to be mediated by the global regulators agr and sar (57). Although the gene products required for S. aureus to induce these effects were not identified in previous publications, we hypothesized that bacterial surface molecules were involved in internalization, since Agr and Sar mutants and cells in the exponential phase were internalized more efficiently (57). It is known that invasion of cells by other microorganisms studied thus far is a multistep process, beginning with attachment, which initiates complex changes in the host cell cytoskeleton and membrane (10, 11, 14, 23, 24, 36, 43, 44). A strong link between bacterial internalization and host cell signaling through protein tyrosine kinases (PTK) has been well documented in several host cell-bacterium interactions (1, 7, 9, 12, 13, 16, 17, 28, 42, 45, 46).

The ability of S. aureus to colonize the surface of host tissues is facilitated by several bacterial surface proteins that have a high affinity for extracellular-matrix components. These proteins, termed MSCRAMMs (microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules), recognize fibronectin (Fn), fibrinogen, collagen, vitronectin, laminin, and other ligands (39). The demonstration in 1978 that Fn in plasma binds to S. aureus first suggested a possible role for Fn adherence as a virulence factor (29). Fn binds to S. aureus with a very high affinity (Kd = 1.8 nM), such that the reaction is practically irreversible under physiological conditions (30, 31, 37, 40, 55). Two Fn binding protein (FnBP) genes, fnbA and fnbB, which confer the Fn binding phenotype, have been cloned from S. aureus 8325-4. The deduced protein sequences (for FnBPA and FnBPB) are 45% identical in their N-terminal region (domain A), whereas the Fn binding regions (domains 1 to 3), the wall-spanning regions (domain W), and the membrane anchor regions (domain M) have 95% identical amino acids (27, 47). Most invasive strains of S. aureus bind Fn, and the number of the bound Fn molecules correlates with the extent of tissue invasiveness (41).

The purpose of the present study was to investigate some of the early events in the internalization of S. aureus by epithelial cells. Considering the significance of FnBPs in invasion of tissues by S. aureus, we explored the hypothesis that FnBPs play a key role in internalization of the organism by nonprofessional phagocytes. In addition to demonstrating that FnBPs play a role in this process, S. aureus internalization was shown to require PTK activity similar to that induced by other organisms capable of entering nonprofessional phagocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The S. aureus laboratory strains and clinical isolates used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains were grown in Todd-Hewitt (TH) broth (Difco Laboratories) at 37°C with aeration, in the presence of antibiotics when necessary. For the experiments, the bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation, washed with sterile 150 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2), and resuspended in invasion medium (described below).

TABLE 1.

S. aureus strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Relevant phenotype or properties | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8325-4 | fnbA+fnbB+ | FnBPA+ FnBPB+, NCTC 8325 cured of prophages, plasmid free | 38 |

| DU5883 | fnbA::TcrfnbB::Emr | FnBPA−, FnBPB−, isogenic mutant of 8325-4 | 19 |

| DU5883(pFnBPA4) | AprCmr | FnBPA+ FnBPB−, DU5883 with multicopy plasmid carrying wild-type fnbA (overexpresses FnBPA) | 19 |

| DU5875 | spa::Tcr | Spa−, isogenic mutant of 8325-4 | 33 |

| DU5880 | clfA::Tn917 | ClfA−, mutant of 8325-4 | 32 |

| Novel | Bovine mastitis isolate | 48 | |

| ATCC 29740; 305 | Bovine mastitis isolate | ATCCa | |

| ATCC 25904; Newman | Human throat isolate | ATCC | |

| MN8 | Human toxic shock syndrome isolate | 8 | |

| ATCC 19095 | Human leg abscess isolate | ATCC |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Cell culture and invasion assay.

An established bovine mammary epithelial cell line (MAC-T) (22) was cultured as described previously (5). Briefly, the cells were grown in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone), insulin (5 μg/ml), hydrocortisone (5 μg/ml), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin sulfate (100 μg/ml). The MAC-T cells were seeded (6.0 × 104 per well) in 24-well culture plates (Costar) and incubated at 37°C under 6% CO2. Upon reaching confluency, the cells were washed once with sterile PBS and incubated overnight (37°C under 6% CO2) in invasion medium (growth medium without antibiotics or serum) (1.0 ml/well).

For most bacterial internalization assays, the following standard assay was used. Confluent MAC-T cell monolayers (approximately 2.0 × 105 to 2.5 × 105 cells/well) were washed once with the invasion medium and inoculated with bacteria suspended in invasion medium (approximately 106 to 107 bacteria per well) to produce multiplicities of infection (MOI) of 5 to 25. After incubation for 1 h (37°C under 6% CO2), the wells were washed once with PBS and then 1.0 ml of invasion medium supplemented with 100 μg of gentamicin was added to each well. The plates were incubated for an additional 1 h with the gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria. The monolayers were washed four times with sterile PBS, detached from the plates by being treated (5 min at 37°C) with 100 μl of trypsin solution (0.25%) in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Gibco-BRL), and then lysed by the addition of 900 μl of sterile deionized water. The cell lysates were serially diluted 10-fold and plated in triplicate on TH agar plates to quantify intracellular staphylococci.

In some experiments, gentamicin was omitted so that the adherent bacteria could be quantified. To assess internalization in the presence of various effectors, the standard assay described above was modified as follows. Prior to inoculation with washed bacteria, confluent MAC-T monolayers were incubated for 15 min with invasion medium containing D3 synthetic peptide (34) (5 to 20 μM) or the PTK inhibitor genistein (250 μM) (Calbiochem) (2, 3) and then inoculated with bacteria. In experiments with bacteria pretreated with bovine Fn (Calbiochem), aliquots of bacterial cell suspensions (100 μl, containing approximately 5 × 107 cells) were added to 900-μl aliquots of PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.1% Tween 80, and 0 to 50 pmol of bovine Fn. The cell suspension was incubated with shaking for 1 h, washed twice with PBS containing 0.1% BSA and 0.1% Tween 80, and resuspended in 1.0 ml of invasion medium. Aliquots of this suspension (100 μl, approximately 5 × 106 cells) were used to inoculate the MAC-T cell monolayers. The inoculum size was verified for each suspension by serial 10-fold dilutions and plating on TH agar. The following steps of these experiments were carried out as described above for the standard assay.

Adherence of bacteria to Fn-coated microtiter wells.

Wells in a 96-well microtiter plate were coated by addition (to each well) of 100 μl of bovine Fn solution (50 μg/ml in HBSS with bivalent ions) or 0.1% BSA (to estimate nonspecific binding) and incubation overnight at 22 to 25°C. After the wells were washed three times with HBSS, any residual binding sites were blocked by adding 100 μl of heat-denatured 0.1% BSA in HBSS (free of bivalent ions) and incubating the mixture for 60 min at room temperature. After the wells were washed once with invasion medium supplemented with 0.1% BSA, 100 μl of bacterial cell suspension (5 × 105 cells in invasion medium supplemented with 0.1% BSA) was added. The specificity for Fn binding was confirmed by adding invasion medium containing soluble bovine Fn (final concentration, 10 or 50 nM) to some wells. The plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and washed four times with PBS to remove nonadherent bacteria. Adherent bacterial cells were detached from the wells by adding 25 μl of 0.25% trypsin solution in HBSS and incubating the mixture for 5 min at 37°C. Detached bacteria were quantified by plating as described above. The results were recorded as the Fn adherence index (100 × CFU recovered/CFU added), which reflected the relative ability of various strains to adhere to the Fn-coated wells under the conditions used.

RESULTS

FnBP is required for efficient internalization of S. aureus 8325-4 by MAC-T cells.

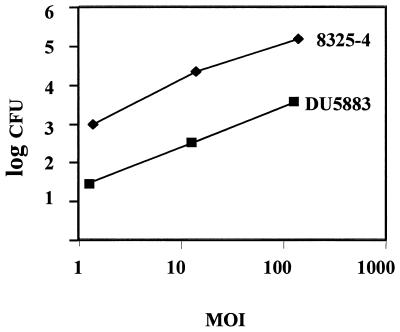

S. aureus expresses several MSCRAMM proteins which could potentially mediate binding and internalization by eukaryotic cells. To assess the role of FnBPs in these processes, invasion assays were performed to compare the internalization potential of parental strain 8325-4 (expressing FnBPA and FnBPB) and its double mutant DU5883 (not expressing FnBPs). Similar to results previously reported for S. aureus Novel and RN6390 (5, 57), 8325-4 exhibited a dose-dependent pattern of internalization (Fig. 1). In comparison, internalization of the DU5883 strain was reduced by more than 95% at all doses tested.

FIG. 1.

Internalization of S. aureus 8325-4 and DU5883 by MAC-T cells. A dose-response internalization assay was performed by inoculating MAC-T cell monolayers with various numbers of bacterial cells to generate the MOI indicated. After 1 h of incubation, extracellular bacteria were killed with gentamicin and the number of intracellular bacteria was determined. Data points represent the means of results from three separate but identically processed infected MAC-T cultures. Results of one representative experiment are shown in this figure. The experiment was performed 10 times.

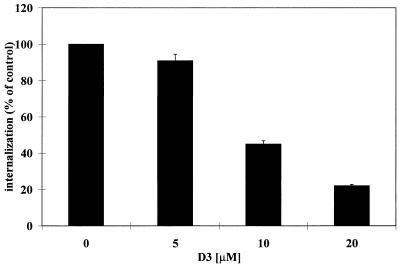

Additional experiments confirmed that the results presented in Fig. 1 were specific to FnBPs and not due to a secondary effect of the mutation. First, internalization of DU5883 was restored to levels 4.5 times higher than that of the parental 8325-4 strain by complementation with pFNBPA4, a plasmid which causes S. aureus transformants to overexpress FnBPA (19) (Table 2). Second, internalization of S. aureus by MAC-T cells could be blocked by pretreating monolayers with an excess of a synthetic peptide corresponding to a conserved functional region of the FnBP proteins. A well-characterized and previously described peptide (34), designated D3, is a 37-amino-acid synthetic peptide corresponding to one of the Fn binding domains of staphylococcal FnBPs. The results presented in Fig. 2 show that the addition of D3, at concentrations ranging from 5 to 20 μM, inhibited S. aureus 8325-4 internalization in a dose-dependent manner. These data indicate that the D3 peptide interferes with internalization by competing with FnBP for its cellular receptor.

TABLE 2.

Internalization of 8325-4 and its derivatives with altered surface proteins

| Strain | Relative internalizationa |

|---|---|

| 8325-4 | 100 |

| DU5883 | 5.5 ± 0.7 |

| DU5883(pFnBPA4) | 450.0 ± 0.4 |

| DU5875 | 85.3 ± 5.4 |

| DU5880 | 81.9 ± 7.1 |

Expressed as percentage of internalization compared to parental control strain 8325-4. A standard invasion assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods, using an MOI of 10 for all strains.

FIG. 2.

Effect of D3 peptide on internalization of S. aureus 8325-4 by MAC-T cells. D3 peptide was added to MAC-T cells 15 min prior to infection and remained in the medium during the experiment. Data are presented as percentage of bacteria (mean and standard error of the mean) internalized in the absence of D3 peptide and represent the mean of triplicate values. An MOI of 5 was used for these experiments, and 100% internalization was equivalent to 4 × 104 CFU.

Although FnBPs were shown above to be required for optimal internalization of S. aureus by MAC-T cells, they are only two of a cadre of MSCRAMMs and other proteins potentially expressed on the surface of staphylococcal cells. It was therefore important to determine whether alteration of other surface proteins could significantly reduce internalization of S. aureus by nonprofessional phagocytes. To accomplish this objective, two other isogenic surface protein knockout mutants of S. aureus 8325-4 were assessed in the standard invasion assay. Unlike DU5883, a protein A-deficient strain, DU5875 (33), and a fibrinogen binding protein MSCRAMM-deficient strain, DU5880 (32), were internalized only slightly less efficiently than was the parental strain 8325-4 (Table 2). This suggested that unlike FnBPs, these two representative surface proteins do not play a significant role in the internalization of S. aureus by MAC-T cells.

Comparison of Fn binding with internalization efficiency.

The FnBP content of staphylococcal isolates, as indicated by their ability to bind Fn, is highly variable (41). Since FnBPs were shown above to be required for the most efficient internalization of 8325-4, it was of interest to determine if heterogeneity in Fn binding ability by different S. aureus strains correlates with their internalization. Two bovine mastitis isolates (Novel and 305) and three well-characterized human isolates (Newman, MN8, and ATCC 19095) were compared for the ability to (i) bind to Fn immobilized on plastic surfaces and (ii) enter MAC-T cells in a standard invasion assay. All of the wild-type strains were internalized by the MAC-T cells, albeit with different efficiencies (Table 3). Their internalization could be reduced to levels comparable to that of the double mutant DU5883 by saturating host and/or bacterial receptors with soluble Fn. The two bovine isolates (Novel and 305) were internalized efficiently (12.9 and 17.8%) and displayed a high level of binding to immobilized Fn, as indicated by their adherence indices in Table 3. Conversely, strain 19095, which bound poorly to Fn, was internalized at levels (0.5%) only slightly higher than the FnBP double mutant DU5883 (0.1%).

TABLE 3.

Internalization of bovine and human S. aureus isolates by MAC-T and adherence to immobilized Fn

| Straina | Percentage of inoculum internalized in:

|

Fn adherence indexd | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medium alone | Medium + 100 nM Fnb | ||

| 8325-4 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 0.001 ± 0.001 | 4.3 ± 0.19 |

| DU5883 | 0.1 ± 0.07 | 0.1 ± 0.05 | 0.1 ± 0.01 |

| DU5883(pFnBPA4) | 11.2 ± 0.7 | NDc | 10.8 ± 0.4 |

| Novel | 17.8 ± 1.6 | 1.0 ± 0.04 | 4.0 ± 0.3 |

| 305 | 12.9 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 5.3 ± 0.4 |

| Newman | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.02 ± 0.006 | 1.3 ± 0.05 |

| MN8 | 18.0 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 1.0 ± 0.02 |

| 19095 | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

Strains are described in Table 1.

The purity of commercially obtained bovine Fn was confirmed by analyzing 20 μg of protein per lane of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels. The preparation resolved into a homogeneous protein band.

ND, not determined.

Calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

As shown in Table 3, the relative ability to adhere to Fn was strain dependent. Although in most cases there was an association between Fn binding and uptake by MAC-T cells, factors other than Fn binding affected internalization with some isolates. For example, the Newman and MN8 strains bound comparably to immobilized Fn but differed significantly in their internalization efficiencies (1.5 and 18.0%, respectively). Combined, these data suggest that FnBP levels generally correlate with internalization efficiency. However, the lack of complete correlation between the efficiency in adherence to immobilized Fn and in internalization by MAC-T indicates that for some strains, production of hemolysins or other toxic extracellular molecules could affect the ability of cells to internalize S. aureus. Alternatively, contact with eukaryotic cells may induce certain changes on the bacterial or host cell surface, affecting the accessibility of FnBPs or their receptors. It is also possible that other factors such as capsule or other MSCRAMMs enhance or reduce internalization regardless of their ability to bind to Fn.

Adherence to MAC-T cells by surface proteins other than FnBPs does not promote efficient internalization.

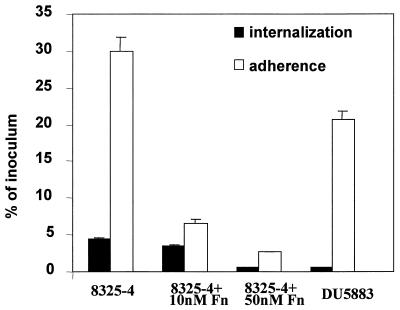

For other facultative intracellular pathogens, adherence is necessary but not sufficient to induce internalization by epithelial cells. High-affinity receptor-ligand interactions and subsequent events, including signal transduction, must be specifically induced prior to internalization (43, 46). To assess if the uptake of S. aureus has similar requirements, experiments were conducted to measure both adherence to and internalization by MAC-T cells for the 8325-4 and DU5883 strains, two isogenic strains shown above to be internalized at significantly different levels. Approximately 5 × 106 CFU of S. aureus was added to cultures of confluent MAC-T cell monolayers, and the adherent and internalized organisms were quantified as described above (Fig. 3). Under standard conditions, 35% of 8325-4 cells adhered to the monolayers. Consistent with the results discussed above, approximately 4% of 8325-4 cells were resistant to gentamicin and therefore were presumed to be intracellular. Involvement of the Fn binding residues of FnBPs in both of these processes was suggested by the observation that both internalization and adherence of any staphylococcal strain used in this study could be significantly reduced by addition of excess Fn to cultures during the infection (Table 3) or by preincubation of bacterial cells with Fn and washing prior to adding them to the monolayer experiment (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of internalization and adherence of S. aureus 8325-4 and DU5883 by MAC-T cells. Monolayers were incubated with bacteria for 1 h at an MOI of 20. Thereafter, either extracellular bacteria were killed by adding gentamicin or the wells were washed and the adherent and internalized bacteria were quantified. The number of adherent bacteria was calculated by subtracting the internalized bacteria from the total count. To assess the effect of Fn, bacterial cells were pretreated with Fn at the concentration shown and washed before being added to the monolayers. Data are presented as the percentage of bacteria adherent or internalized compared to the original inoculum and represent the means and standard errors of the mean of three independent experiments.

As described above, S. aureus produces a vast array of MSCRAMMs that are involved in adherence to various extracellular-matrix molecules. Although our results suggested that FnBP-mediated adherence and the ability to be internalized are related, our goal was to determine if these events could be uncoupled. Interestingly, 21% of the DU5883 cells adhered to the MAC-T cells, indicating that the inability to express FnBPs was associated with a reduction in adherence of only 40%, compared to the parental strain, 8325-4. In contrast to the moderate reduction in adherence, the absence of FnBPs in strain DU5883 nearly completely abrogated internalization. Therefore, with regard to adherence to epithelial cells, strain DU5883 may compensate for the lack of FnBPs with additional surface binding proteins, most probably MSCRAMMs recognizing other extracellular-matrix proteins. However, binding to MAC-T cells via these alternate surface ligands cannot promote efficient internalization of the organism. Thus, although S. aureus possesses numerous MSCRAMMs that allow the organism to bind to extracellular-matrix proteins, binding of 8325-4 via FnBPs is responsible for the majority of internalization by MAC-T cells.

Genistein reversibly inhibits internalization of S. aureus by MAC-T cells.

Internalization of obligate and facultative intracellular pathogens requires activation and participation of the host cell cytoskeleton (10). Although not entirely elucidated, in many cases the pathways leading to cytoskeletal rearrangement are initiated by PTK activation induced by bacterial binding to host cell receptors. Since cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of actin polymerization, blocks internalization of staphylococci by MAC-T cells (5), it was of interest to determine if PTK activity is required for uptake of S. aureus, as in other systems.

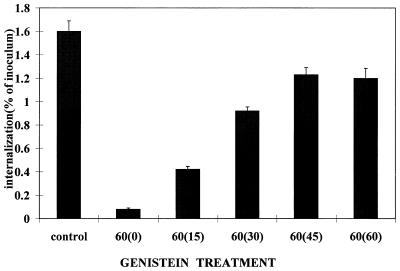

Based on results summarized in Fig. 4, it was concluded that efficient internalization of 8325-4 requires PTK activity. A 15-min preincubation with genistein, an inhibitor of PTKs, reduced internalization of the organism by greater than 95% compared to untreated controls. The inhibition was not the result of genistein-induced toxicity for either the staphylococci or the MAC-T cells, since removal of the genistein by washing resulted in a partial recovery after as little as 15 min. At 45 min after the removal of genistein, the level of internalization reached 79% of that of the untreated control.

FIG. 4.

Effect of genistein on internalization of S. aureus 8325-4 by MAC-T cells. MAC-T cells were pretreated with genistein (250 μM) for 15 min immediately prior to inoculation with bacteria (MOI = 11). Control cultures had no genistein added. Genistein was retained in all cultures for 60 min. After 60 min, the genistein was removed by washing the monolayers and internalized bacteria were quantified immediately (0) or after an additional period of incubation (minutes) indicated on the abscissa. Data are presented as the percentage of bacteria internalized in the absence of genistein and are means and standard errors of the mean of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Although not traditionally considered an intracellular pathogen, S. aureus can enter endothelial cells (6, 20, 49, 50, 53), epithelial cells (4, 5), and osteoblasts (21) in vitro. We and others reported previously that uptake requires host cytoskeletal rearrangements and induced membrane structures similar to those seen during entry of Listeria and Yersinia spp. into nonprofessional phagocytes (5). The present study investigated early events in S. aureus internalization by MAC-T cells. It showed that internalization of S. aureus shares two fundamental requirements with intracellular pathogens: (i) a crucial ligand (FnBP) on the bacterial surface and (ii) PTK activity probably representing host cell signal transduction.

The conclusion that FnBPs are required for efficient internalization by nonprofessional phagocytes arose from several lines of evidence. Mutants unable to express FnBPs were dramatically reduced in their ability to enter MAC-T cells, whereas strains with mutations in genes encoding other surface proteins (clumping factor [fibrinogen binding protein] and protein A) were internalized only slightly less efficiently. We obtained similar results with other cell lines in vitro, including HEp-2 (9) and Caco-2 (12) cells of human origin (our unpublished results), indicating that the requirement for FnBPs is not limited to entry into bovine epithelial cells. S. aureus FnBPs have long been recognized for their role in colonization and invasion of tissues by binding to Fn in the extracellular matrix. It is now clear that they are also required for internalization by epithelial cells. It is generally agreed that colonization of the vascular endothelium or mucosal surfaces is a prerequisite to internalization of bacteria by nonprofessional phagocytes. The outcome of colonization is determined largely by receptor-ligand interactions between the host cell and the pathogen surfaces as described by Isberg and Tran Van Nhieu (25).

FnBPs could induce internalization through several possible mechanisms. One possibility is that they are the ligand or part of a ligand complex that interacts directly with a host cell surface receptor. As such, they could function similarly to ligands reported for Listeria spp. (18), Yersinia spp. (24, 26), or Neisseria gonorrhoeae (54). Alternatively, the FnBPs could act indirectly by exposing or stabilizing an appropriate conformation of another surface protein which functions as the true ligand. Our results showing that D3 or soluble Fn blocks internalization and our demonstration that Fn binding correlates with the ability of staphylococci to interact with host cell receptors suggest that the former possibility is most likely for S. aureus.

Although strain DU5883 is deficient in FnBPs, its adherence to MAC-T cells was reduced by only 40% compared to that of parental strain 8325-4. Similarly, Flock et al. (15) reported no difference in adherence of these two strains in vivo with a rat endocarditis model. Thus, either in vitro or in vivo, other surface molecules such as MSCRAMMs compensate for the lack of Fn binding by DU5883, allowing the organism to bind to cells. However, our results confirmed that adherence alone is insufficient to induce internalization, since uptake of DU5883 by MAC-T cells was nearly completely abrogated. It is generally assumed that uptake of microorganisms has two essential requirements: (i) binding to a host cell receptor with an affinity sufficient to transduce an appropriate signal through the membrane, and (ii) subsequent cytoskeletal rearrangement leading to uptake. It is now clear that the uptake of staphylococci occurs via the same general mechanisms. We and others have shown previously that entry of S. aureus into nonprofessional phagocytes is characterized by changes in the host cell membrane, leading to engulfment of the bacterium (4, 5). In addition, uptake was impaired by cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of actin polymerization. The present study has further extended these observations by demonstrating a requirement for PTK activity; uptake was sensitive to genistein, an inhibitor of PTK activity. The effect was not due to a toxicity for the host cell or bacteria, since inhibition of internalization was reversed by removal of genistein from the cultures.

The host cell ligand responsible for FnBP-mediated internalization remains to be determined. One possibility is that S. aureus utilizes a receptor employed by other organisms. Several host cell proteins are known to bind and mediate bacterial internalization by involvement of different host signal transduction systems. Different classes of protein kinases participate in this process (12, 42–46, 52, 56). Isberg and Leong (24) reported that β1-integrins are receptors for invasin, a protein that promotes the entry of Yersinia spp. into host cells. The integrins interact with the cytoskeleton by noncovalent binding between cytoplasmic domains of integrin β-chains and various actin binding proteins within the focal adhesion complex (56). Likewise, Mengaud et al. (35) identified E-cadherins as the cell receptor for Listeria monocytogenes internalin. Rosenshine et al. (46) showed that enteropathogenic Escherichia coli attached to epithelial cells, causing actin polymerization at the adherence site and phosphorylation of epithelial membrane protein Hp90, which then associates directly with bacterial intimin.

The role of Fn in internalization remains to be determined. The Fn binding capacity partly correlated with the ability of various strains of staphylococci to be internalized, and excess soluble Fn blocked internalization by the MAC-T cells. These results are consistent with several potential models of uptake. In one model, Fn is a bifunctional molecule which forms a “bridge” between FnBP and a cellular receptor, linking the bacteria to the cell surface. If this were the case, a likely candidate for a cellular receptor would be the αβ-integrins, which are well known for their ability to bind to Fn or other extracellular-matrix components. Several well-characterized intracellular pathogens are internalized by binding to integrins. Furthermore, as described above, integrins have the potential to induce signal transduction, leading to cytoskeletal rearrangements. While this “bridge” model may be supported by circumstantial evidence, several lines of evidence suggest that S. aureus may bind directly to a host cell receptor without an Fn bridge. Our demonstration that S. aureus internalization is blocked by Fn is consistent with a direct-binding mode. Presumably, Fn blocks a site on the FnBP, which binds to the host cell receptor. Furthermore, the affinity of Fn binding to α5β1-integrin receptor is lower (Kd = 8 × 10−7) than the affinity of ligands such as invasin (Kd = 5 × 10−9) and is generally not believed to be sufficiently high to induce internalization (24, 25, 51). For example, Isberg and colleagues showed that the interaction of Fn with α5β1-integrin molecules is too weak to mediate internalization and that particles or bacteria artificially coated with Fn are not internalized (24, 25). Identification of the receptors and ligands involved is an area under investigation in our laboratories, and it should differentiate between these two potential mechanisms of binding.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by PHS grants AI28401 (G.A.B.) and AI38901 (K.W.B.), the United Dairymen of Idaho (G.A.B.), and a sabbatical fellowship from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (W.R.T.).

We are grateful to Tim Foster, who supplied many of the strains used in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam T, Arpin M, Prevost M C, Gounon P, Sansonetti P J. Cytoskeletal rearrangements and the functional role of T-plastin during entry of Shigella flexneri into HeLa cells. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:367–381. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akiyama T, Ishida J, Nakagawa S, Ogawara H, Watanabe S, Itoh N, Shibuya M, Fukami Y. Genistein, a specific inhibitor of tyrosine-specific protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5592–5595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akiyama T, Ogawara H. Use and specificity of genistein as inhibitor of protein-tyrosine kinases. Methods Enzymol. 1991;201:362–370. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)01032-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almeida R A, Matthews K R, Cifrian E, Guidry A J, Oliver S P. Staphylococcus aureus invasion of bovine mammary epithelial cells. J Dairy Sci. 1996;79:1021–1026. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(96)76454-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayles K W, Wesson C A, Liou L E, Fox L K, Bohach G A, Trumble W R. Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus escapes the endosome and induces apoptosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:336–342. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.336-342.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beekhuizen H, van de Gevel J S, Olsson B, van Benten I J, van Furth R. Infection of human vascular endothelial cells with Staphylococcus aureus induces hyperadhesiveness for human monocytes and granulocytes. J Immunol. 1997;158:774–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bliska J B, Galan J E, Falkow S. Signal transduction in the mammalian cell during bacterial attachment and entry. Cell. 1993;73:903–920. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90270-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohach G A, Kreiswirth B N, Novick R P, Schlievert P M. Analysis of toxic shock syndrome isolates producing staphylococcal enterotoxins B and C1 with use of southern hybridization and immunologic assays. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(Suppl. 1):S75–S81. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.supplement_1.s75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun L, Ohayon H, Cossart P. The InIB protein of Listeria monocytogenes is sufficient to promote entry into mammalian cells. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1077–1087. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cossart P. Host/pathogen interactions. Subversion of the mammalian cell cytoskeleton by invasive bacteria. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:2307–2311. doi: 10.1172/JCI119409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cossart P, Lecuit M. Interactions of Listeria monocytogenes with mammalian cells during entry and actin-based movement: bacterial factors, cellular ligands and signaling. EMBO J. 1998;17:3797–3806. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehio C, Prevost M C, Sansonetti P J. Invasion of epithelial cells by Shigella flexneri induces tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin by a pp60c-src-mediated signalling pathway. EMBO J. 1995;14:2471–2482. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fallman M, Persson C, Wolf-Watz H. Yersinia proteins that target host cell signaling pathways. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:1153–1157. doi: 10.1172/JCI119270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finlay B B, Cossart P. Exploitation of mammalian host cell functions by bacterial pathogens. Science. 1997;276:718–725. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.718. . (Erratum, 278:373, 1997.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flock J I, Hienz S A, Heimdahl A, Schennings T. Reconsideration of the role of fibronectin binding in endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1876–1878. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1876-1878.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foubister V, Rosenshine I, Donnenberg M S, Finlay B B. The eaeB gene of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is necessary for signal transduction in epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3038–3040. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.3038-3040.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francis C L, Ryan T A, Jones B D, Smith S J, Falkow S. Ruffles induced by Salmonella and other stimuli direct macropinocytosis of bacteria. Nature. 1993;364:639–642. doi: 10.1038/364639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaillard J-L, Berche P, Frehel C, Gouin E, Cossart P. Entry of L. monocytogenes into cells is mediated by internalin, a repeat protein reminescent of surface antigens in gram-positive cocci. Cell. 1991;65:1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90009-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene C, McDevitt D, Francois P, Vaudaux P E, Lew D P, Foster T J. Adhesion properties of mutants of Staphylococcus aureus defective in fibronectin-binding proteins and studies on the expression of fnb genes. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:1143–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17061143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamill R J, Vann J M, Proctor R A. Phagocytosis of Staphylococcus aureus by cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells: model for postadherence events in endovascular infections. Infect Immun. 1986;54:833–836. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.3.833-836.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudson M C, Ramp W K, Nicholson N C, Williams A S, Nousianen M T. Internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by cultured osteoblasts. Microb Pathog. 1995;19:409–419. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1995.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyunh H T, Robitaille G, Turner J D. Establishment of bovine mammary epithelial cells (MAC-T): an in vivo model for bovine lactation. Exp Cell Res. 1991;197:191–199. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90422-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ireton K, Cossart P. Interaction of invasive bacteria with host signaling pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:276–283. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isberg R R, Leong J M. Multiple beta 1 chain integrins are receptors for invasin, a protein that promotes bacterial penetration into mammalian cells. Cell. 1990;60:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90099-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isberg R R, Tran Van Nhieu G. Binding and internalization of microorganisms by integrin receptors. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:10–14. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isberg R R. Uptake of enteropathogenic Yersinia by mammalian cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;209:1–24. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85216-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jonsson K, Signas C, Muller H P, Lindberg M. Two different genes encode fibronectin binding proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. The complete nucleotide sequence and characterization of the second gene. Eur J Biochem. 1991;202:1041–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenny B, Finlay B B. Intimin-dependent binding of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to host cells triggers novel signaling events, including tyrosine phosphorylation of phospholipase C-γ1. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2528–2536. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2528-2536.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuusela P. Fibronectin binds to Staphylococcus aureus. Nature. 1978;276:718–720. doi: 10.1038/276718a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuusela P, Vartio T, Vuento M, Myhre E B. Binding sites for streptococci and staphylococci in fibronectin. Infect Immun. 1984;45:433–436. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.2.433-436.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maxe I, Ryden C, Wadstrom T, Rubin K. Specific attachment of Staphylococcus aureus to immobilized fibronectin. Infect Immun. 1986;54:695–704. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.3.695-704.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDevitt D, Francois P, Vaudaux P, Foster T J. Molecular characterization of the clumping factor (fibrinogen receptor) of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:237–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDevitt D, Francois P, Vaudaux P, Foster T J. Identification of the ligand-binding domain of the surface-located fibrinogen receptor (clumping factor) of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:895–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGavin M J, Gurusiddappa S, Lindgren P E, Lindberg M, Raucci G, Hook M. Fibronectin receptors from Streptococcus dysgalactiae and Staphylococcus aureus. Involvement of conserved residues in ligand binding. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23946–23953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mengaud J, Ohayon H, Gounon P, Mege R-M, Cossart P. E-cadherin is the receptor for internalin, a surface protein required for entry of L. monocytogenes into epithelial cells. Cell. 1996;84:923–932. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merz A J, So M. Attachment of piliated, Opa− and Opc− gonococci and meningococci to epithelial cells elicits cortical actin rearrangements and clustering of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4341–4349. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4341-4349.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mosher D F, Proctor R A. Binding and factor XIIIa-mediated cross-linking of a 27-kilodalton fragment of fibronectin to Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 1980;209:927–929. doi: 10.1126/science.7403857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novick R. Properties of a cryptic high-frequency transducing phage in Staphylococcus aureus. Virology. 1967;33:155–166. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patti J M, Allen B L, McGavin M J, Hook M. MSCRAMM-mediated adherence of microorganisms to host tissues. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:585–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Proctor R A, Mosher D F, Olbrantz P J. Fibronectin binding to Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:14788–14794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Proctor R A, Christman G, Mosher D F. Fibronectin-induced agglutination of Staphylococcus aureus correlates with invasiveness. J Lab Clin Med. 1984;104:455–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenshine I, Duronio V, Finlay B B. Tyrosine protein kinase inhibitors block invasin-promoted bacterial uptake by epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2211–2217. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2211-2217.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenshine I, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B, Finlay B B. Signal transduction between enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and epithelial cells: EPEC induces tyrosine phosphorylation of host cell proteins to initiate cytoskeletal rearrangement and bacterial uptake. EMBO J. 1992;11:3551–3560. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenshine I, Finlay B B. Exploitation of host signal transduction pathways and cytoskeletal functions by invasive bacteria. Bioessays. 1993;15:17–24. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenshine I, Ruschkowski S, Foubister V, Finlay B B. Salmonella typhimurium invasion of epithelial cells: role of induced host cell tyrosine protein phosphorylation. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4969–4974. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4969-4974.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenshine I, Ruschkowski S, Stein M, Reinscheid D J, Mills S D, Finlay B B. A pathogenic bacterium triggers epithelial signals to form a functional bacterial receptor that mediates actin pseudopod formation. EMBO J. 1996;15:2613–2624. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Signäs C, Raucci G, Jonsson H, Lindgren P E, Anantharamaiah G M, Lindberg M. Nucleotide sequence of the gene for a fibronectin-binding protein from Staphylococcus aureus: use of this peptide sequence in the synthesis of biologically active peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:699–703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith T H, Fox L K, Middleton J R. An outbreak of mastitis caused by a single strain of Staphylococcus aureus in a closed herd where strict milking time hygiene has been employed. J Vet Med Assoc. 1998;212:553–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tompkins D C, Hatcher V B, Patel D, Orr G A, Higgins L L, Lowy F D. A human endothelial cell membrane protein that binds Staphylococcus aureus in vitro. J Clin Investig. 1990;85:1248–1254. doi: 10.1172/JCI114560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tompkins D C, Blackwell L J, Hatcher V B, Elliott D A, O’Hagan-Sotsky C, Lowy F D. Staphylococcus aureus proteins that bind to human endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1992;60:965–969. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.965-969.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tran Van Nhieu G, Isberg R R. Bacterial internalization mediated by β1 chain integrins is determined by ligand affinity and receptor density. EMBO J. 1993;12:1887–1895. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Langendonck N, Velge P, Bottreau E. Host cell protein tyrosine kinases are activated during the entry of Listeria monocytogenes. Possible role of pp60c-src family protein kinases. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;162:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vann J M, Proctor R A. Ingestion of Staphylococcus aureus by bovine endothelial cells results in time- and inoculum-dependent damage to endothelial cell monolayers. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2155–2163. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2155-2163.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.vanPutten J P M, Duensing T D, Cole R L. Entry of OpaA+ gonococci into Hep-2 cells requires concerted action of glycosaminoglycans, fibronectin, and integrin receptors. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:369–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vartio T. Characterization of the binding domains in the fragments cleaved by cathepsin G from human plasma fibronectin. Eur J Biochem. 1982;123:223–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb19757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watarai M, Funato S, Sasakawa C. Interaction of Ipa proteins of Shigella flexneri with alpha5beta1 integrin promotes entry of the bacteria into mammalian cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:991–999. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wesson C A, Liou L E, Todd K M, Bohach G A, Trumble W R, Bayles K W. The Staphylococcus aureus Agr and Sar global regulators influence internalization and induction of apoptosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5238–5243. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5238-5243.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]