Abstract

Objective:

To identify the prevalence and predictors of (a) thoughts of suicide or self-harm among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and (b) help-seeking among those healthcare workers with thoughts of suicide or self-harm.

Method:

Analysis of data from the Australian COVID-19 Frontline Healthcare Workers Study, an online survey of healthcare workers conducted during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Outcomes of interest were thoughts of suicide or self-harm as measured through the Patient Health Questionnaire for depression and help-seeking behaviours.

Results:

Overall, 819 (10.5%) of 7795 healthcare workers reported thoughts of suicide or self-harm over a 2-week period. Healthcare workers with these thoughts experienced higher rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and burnout than their peers. In multivariable models, the odds of suicide or self-harm thoughts were higher among workers who had friends or family infected with COVID-19 (odds ratio = 1.24, 95% confidence interval = [1.06, 1.47]), were living alone (odds ratio = 1.32, 95% confidence interval = [1.06, 1.64]), younger (⩽30 years cf. >50 years; odds ratio = 1.70, 95% confidence interval = 1.36-2.13), male (odds ratio = 1.81, 95% confidence interval = [1.49, 2.20]), had increased alcohol use (odds ratio = 1.58, 95% confidence interval = [1.35, 1.86]), poor physical health (odds ratio = 1.62, 95% confidence interval = [1.36, 1.92]), increased income worries (odds ratio = 1.81, 95% confidence interval = [1.54, 2.12]) or prior mental illness (odds ratio = 3.27, 95% confidence interval = [2.80, 3.82]). Having dependent children was protective (odds ratio = 0.75, 95% confidence interval = [0.61, 0.92]). Fewer than half (388/819) of the healthcare workers who reported thoughts of suicide or self-harm sought professional support. Healthcare workers with thoughts of suicide or self-harm were more likely to seek support if they were younger (⩽30 years cf. >50 years; odds ratio = 1.78, 95% confidence interval = [1.13, 2.82]) or had prior mental health concerns (odds ratio = 4.47, 95% confidence interval = [3.25, 6.14]).

Conclusion:

One in 10 Australian healthcare workers reported thoughts of suicide or self-harm during the pandemic, with certain groups being more vulnerable. Most healthcare workers with thoughts of suicide or self-harm did not seek professional help. Strong and sustained action to protect the safety of healthcare workers, and provide meaningful support, is urgently needed.

Keywords: Suicide, self-harm, COVID-19, health practitioners, patient safety

Introduction

Thoughts of suicide or self-harm among healthcare workers sound the alarm for high levels of mental health distress, with potentially devastating consequences for healthcare workers, their families and the communities they serve. From a patient care perspective, we know that depressed doctors have higher rates of medical errors (Fahrenkopf et al., 2008) and suicidal ideation has been associated with impaired cognitive functioning (Marzuk et al., 2005). For individual healthcare workers and their loved ones, thoughts of suicide or self-harm are deeply troubling in their own right, as well as being associated with an increased risk of self-injury and death by suicide (Large et al., 2021; Pirkis et al., 2000).

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, doctors and nurses were known to have higher rates of suicidal ideation and death by suicide (Milner et al., 2016; Petrie et al., 2019) than other occupations. These increased rates have been attributed to occupational stressors (Petrie et al., 2020, 2021), barriers to care (Forbes et al., 2019) and access to prescription medicines which can be a lethal means of suicide (Milner et al., 2016).

Crisis events, such as natural disasters and wars, are well recognised to be associated with increased suicide rates in frontline responders (Kaplan et al., 2007; Matsubayashi et al., 2013). A growing body of research from Australia and around the world demonstrates that the pandemic has greatly increased the workload, stress and distress experienced by healthcare workers (Smallwood et al., 2021). There have been anecdotal reports of healthcare workers involved in the care of COVID-19 patients dying by suicide (Romo, 2020; Uvais, 2021), and an emerging body of international research is finding high rates of suicidal ideation among healthcare workers during the pandemic (Sahimi et al., 2021). However, most international studies have focused on doctors and nurses, have been limited to samples of fewer than a thousand healthcare workers and have included only a limited number of personal or occupational risk factors. To date, there have been no large-scale Australian studies examining the prevalence and risk factors for thoughts of suicide or self-harm among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, it is unclear whether healthcare workers experiencing thoughts of suicide or self-harm access mental healthcare. This information is crucial in order to understand which healthcare workers are most in need of support and how this support can best be targeted.

This article reports a subset of analyses from the Australian COVID-19 Frontline Healthcare Workers Study (Smallwood et al., 2021), which investigated the severity and prevalence of mental health symptoms and the social, workplace and financial disruptions experienced by Australian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesised that the personal, social and workplace characteristics and help-seeking behaviours of healthcare workers with thoughts of suicide or self-harm would significantly differ from those who did not experience these thoughts.

Methods

Study design and sample

A nationwide, voluntary, online survey was undertaken between 27 August and 23 October 2020, during the second wave of the pandemic in Australia. The full study methodology has been published elsewhere (Shaukat et al., 2020; Smallwood et al., 2021). The study period coincided with stringent lockdowns, particularly in Melbourne, which was the centre of the second wave. Healthcare workers from all professions and backgrounds, who self-identified as frontline healthcare workers in primary or secondary care, were invited to participate. As part of the survey, healthcare workers were asked to identify their profession and area of work. Participants did not need to have cared for people infected with COVID-19 to take part. Information regarding the survey was widely disseminated across Australia by hospital leaders, professional societies, colleges, universities, associations, government health departments and the media.

Data collection

Each participant completed the survey once, via an online survey link or the study website (https://covid-19-frontline.com.au/). Data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools. The survey questionnaire collected data regarding demographics, professional background, workplace situation and change, organisational leadership, health and recreational habits, and symptoms of mental illness (both subjectively determined and assessed using validated, objective mental health symptom measurement tools).

To help maintain the anonymity of respondents, age was collected in bands. Information on previous mental illness was collected using the following question: ‘Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic have you ever been diagnosed with depression, anxiety, or another mental health condition?’

Four validated psychological measurement tools were completed to assess current symptoms of mental illnesses: anxiety – Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006), depression – Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – Impact of Events Scale-6 (IES-6; Thoresen et al., 2010) and burnout – Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach et al., 1997), with subdomains of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and personal accomplishment. For each mental illness scale, outcomes were merged into dichotomous categories (no or minimal symptoms compared to moderate to severe symptoms). Cut-off scores were as follows: GAD-7 10–21 = moderate to severe anxiety; PHQ-9 10–27 = moderate to severe depression; IES-6 >9 = moderate to severe PTSD; MBI depersonalization ⩾4 = moderate to high; emotional exhaustion ⩾7 = moderate to high; personal accomplishment ⩾15 = low. Thoughts of suicide or self-harm were identified from the following question (item 9) of the PHQ-9: ‘Over the past two weeks how often have you been bothered by ... thoughts that you would be better off dead, or thoughts of hurting yourself in some way?’

Participants provided digital consent before completing the survey. The Royal Melbourne Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (HREC/67074/MH-2020).

Analysis

Data analysis was performed using Stata software, version 14.1 (StataCorp). Thoughts of suicide or self-harm over the past 2 weeks were coded as ‘nil’ (not bothered by such thoughts over the last 2 weeks), ‘occasional’ (several days over the past 2 weeks) or ‘frequent’ (more than half the days, or nearly every day over the past 2 weeks). Support strategies were coded into ‘self-care and informal help-seeking’, including exercise, social connections or the use of health apps, and ‘help-seeking from professionals’, including doctors and psychologists, employee assistance programmes and other professional supports.

Area of work was coded into six areas: emergency department, intensive care, surgical specialty areas, medical specialty areas, primary and community care and other areas of work. Surgical specialty areas included general surgery, surgical specialities, anaesthesia and perioperative care. Medical specialty areas included general medicine, respiratory medicine, infectious diseases, hospital aged care, palliative care and other medical specialties. Primary and community care included primary care, community care and non-hospital aged care. Other areas of work included paramedicine, radiology, pharmacy, pathology, maintenance, clerical or administrative, COVID-19 screening and other areas not elsewhere specified.

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics are reported descriptively. Chi-square tests were used to assess univariable associations between thoughts of suicide or self-harm and (a) participant characteristics, (b) mental health symptoms and (c) use of support strategies.

Predictors of thoughts of suicide or self-harm, and help-seeking, were identified through univariable and multivariable logistic regression models. In the regression analyses, thoughts of suicide or self-harm were combined into a binary variable reporting whether they were present or not, with ‘occasional’ and ‘frequent’ combined into ‘any’. Predictor variables examined were sex, age, occupation, area of work, practice location, state, physical health, pre-existing mental health condition, living alone, living with children, having close friends or relatives infected with COVID-19, increased concerns regarding household income during the pandemic, increased alcohol use during the pandemic and exposure to patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.

All predictors were initially included in a single multivariable model, then predictors which were not associated (with p > 0.2) were removed and the model refitted. This process was repeated until all predictors had p < 0.2, after which predictors with p > 0.1 were removed. Once all predictors in the model had p < 0.1, predictors excluded earlier were added back in one at a time and retained if p < 0.1. Additional models including and excluding predictors with p-values between 0.01 and 0.1 were fitted and the model which had the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC) was compared with the full multivariable model. For predictors with more than two categories, multivariate Wald tests were used to assess the significance of the association of the exposure with the outcome. Pairwise interactions were assessed for all predictors in the best models. The robustness of the models was assessed by removing the most outlying and/or influential observations, refitting the model and assessing changes in estimates, confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values. Associations are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs and statistical significance declared at p < 0.05.

Results

Study sample

Overall, 9518 people started the survey, with 7846 responses deemed complete for broader analyses. The non-mandatory question on thoughts of suicide or self-harm was answered by 7795 participants, who formed the sample for our analysis. Most participants were women (n = 6300, 81%), reflecting the predominantly female health workforce in Australia where 85% of the welfare workforce – including aged carers and support workers – and 75% of the registered health practitioners are women (Ahpra, 2019).

Although the survey was distributed nationally, around 85% of responses were from Victoria. This likely reflects the research team being based in Victoria, and therefore having stronger recruitment networks in the state, and Victoria being the state most affected by the pandemic and associated restrictions at the time of the survey. Participants came from multiple professional backgrounds including medicine (n = 2447, 31%), nursing (n = 3053, n = 39%), allied health (n = 1564, 20%) and other roles such as pharmacists, paramedics, technicians and support staff (n = 730, 9%).

Characteristics of healthcare workers with nil, occasional and frequent thoughts of suicide or self-harm

Eight hundred and nineteen participants of 7795 (10.5%) reported occasional or frequent thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The frequency of thoughts of suicide or self-harm varied across multiple personal, social and workplace characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

| Total (N = 7795) | Nil thoughts of suicide or self-harm (N = 6976) | Occasional thoughts of suicide or self-harm (N = 557) | Frequent thoughts of suicide or self-harm (N = 262) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sex | < 0.001 | ||||

| Male | 1452 (19) | 1266 (18) | 120 (22) | 66 (25) | |

| Female | 6300 (81) | 5681 (81) | 428 (77) | 191 (73) | |

| Non-binary / prefer not to say | 43 (1) | 29 (0) | 9 (2) | 5 (2) | |

| Age, years | < 0.001 | ||||

| ⩽30 | 1848 (24) | 1582 (23) | 177 (32) | 89 (34) | |

| 31–40 | 2237 (29) | 2000 (29) | 155 (28) | 82 (31) | |

| 41–50 | 1730 (22) | 1575 (23) | 116 (21) | 39 (15) | |

| >50 | 1980 (25) | 1819 (26) | 109 (20) | 52 (20) | |

| Occupation | 0.089 | ||||

| Medicine | 2447 (31) | 2222 (32) | 157 (28) | 68 (26) | |

| Nursing | 3053 (39) | 2710 (39) | 228 (41) | 115 (44) | |

| Allied health | 1564 (20) | 1404 (20) | 113 (20) | 47 (18) | |

| Other | 730 (9) | 639 (9) | 59 (11) | 32 (12) | |

| Location | 0.381 | ||||

| Metropolitan | 6335 (81) | 5684 (81) | 442 (79) | 209 (80) | |

| Regional / rural | 1460 (19) | 1292 (19) | 115 (21) | 53 (20) | |

| State | 0.763 | ||||

| Victoria | 6643 (85) | 5947 (85) | 470 (84) | 226 (86) | |

| Other | 1152 (15) | 1029 (15) | 87 (16) | 36 (14) | |

| Area of work | 0.019 | ||||

| Emergency department | 1140 (15) | 1011 (14) | 86 (15) | 43 (16) | |

| Intensive care | 742 (10) | 674 (10) | 48 (9) | 20 (8) | |

| Surgical specialty areas | 818 (10) | 712 (10) | 77 (14) | 29 (11) | |

| Medical specialty areas | 3079 (40) | 2757 (40) | 213 (38) | 109 (42) | |

| Primary / community care | 1324 (17) | 1217 (17) | 75 (13) | 32 (12) | |

| Other | 691 (9) | 604 (9) | 58 (10) | 29 (11) | |

| Physical health | < 0.001 | ||||

| Excellent / good | 6396 (82) | 5818 (83) | 413 (74) | 165 (63) | |

| Fair / poor | 1399 (18) | 1158 (17) | 144 (26) | 97 (37) | |

| Previous mental illness | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 2375 (30) | 1909 (27) | 299 (54) | 167 (64) | |

| No | 5420 (70) | 5067 (73) | 258 (46) | 95 (36) | |

| Lives alone | 0.002 | ||||

| Yes | 1078 (14) | 934 (13) | 92 (17) | 52 (20) | |

| No | 6717 (86) | 6042 (87) | 465 (83) | 210 (80) | |

| Children at home | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 2730 (35) | 2506 (36) | 161 (29) | 63 (24) | |

| No | 5065 (65) | 4470 (64) | 396 (71) | 199 (76) | |

| Income worries | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 2397 (31) | 2041 (29) | 219 (39) | 137 (52) | |

| No | 5398 (69) | 4935 (71) | 338 (61) | 125 (48) | |

| Increased alcohol use | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 2056 (26) | 1747 (25) | 184 (33) | 125 (48) | |

| No | 5739 (74) | 5529 (75) | 373 (67) | 137 (52) | |

| Friends or relatives with COVID-19 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 2386 (31) | 2093 (30) | 181 (32) | 112 (43) | |

| No | 5409 (69) | 4883 (70) | 376 (68) | 150 (57) | |

| Exposed to COVID-19 patients (suspected or confirmed) | 0.003 | ||||

| Yes | 4536 (58) | 4020 (58) | 341 (61) | 175 (67) | |

| No | 3246 (42) | 2946 (42) | 214 (39) | 86 (33) |

Comparing those with no, occasional or frequent thoughts of suicide or self-harm, we observed stepwise increases in the proportion of participants who were male, aged 30 years or younger, living alone, with fair or poor health, previous mental illness, increased income worries, increased alcohol use, friends or family with COVID-19, or exposure to COVID-19 patients. p < 0.005for all

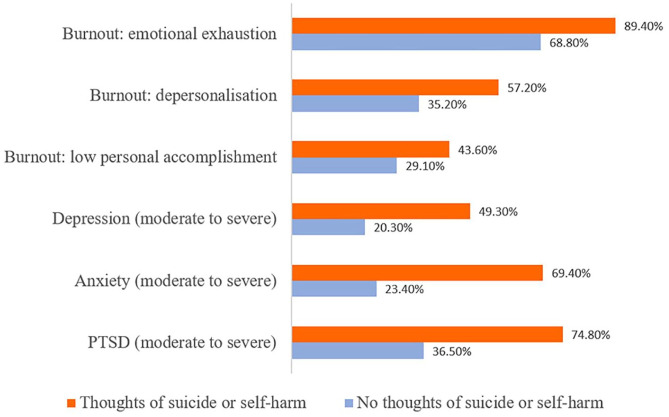

Mental health symptoms among healthcare workers with and without thoughts of suicide or self-harm

Healthcare workers with thoughts of suicide or self-harm reported significantly higher rates of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, depression, anxiety and PTSD symptoms than their peers (p < 0.01 for all mental health symptoms measured; Figure 1). Around half were experiencing symptoms consistent with moderate to severe depression (49.3%), with almost all (97.4%) reporting at least mild depression with a PHQ-9 score of 5 or above.

Figure 1.

Mental health symptoms among healthcare workers with and without thoughts of suicide or self-harm.

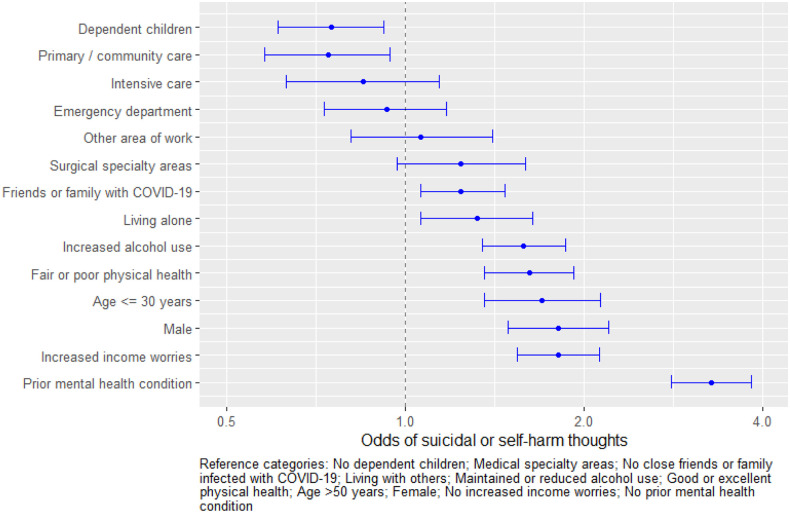

Multivariable predictors of thoughts of suicide or self-harm among healthcare workers

In our multivariable analyses, the ORs for the full models were very similar to those of the reduced models which excluded predictors that were not significantly associated with the outcome (e.g. male: OR = 1.81, 95% CI = [1.49, 2.20] vs OR = 1.75, 95% CI = [1.45, 2.11], respectively). The AICs from the full and reduced multivariable models were also very similar (AIC = 4741.06 vs 4739.59, respectively). We therefore present results from the full multivariable models below. Predictors which had significant results in the models for either of our two outcomes are shown in the figures, with full results of univariable and multivariable logistic regression models provided in Supplementary Tables.

As shown in Figure 2, the odds of suicidal or self-harm thoughts were significantly higher among healthcare workers who had close friends or family members infected with COVID-19 (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = [1.06, 1.47]), were living alone (OR = 1.32, 95% CI = [1.06, 1.64]), younger (⩽30 years cf. >50 years; OR = 1.70, 95% CI = [1.36, 2.13]), male (OR = 1.81, 95% CI = [1.49, 2.20]), reported increased alcohol (OR = 1.58, 95% CI = [1.35, 1.86]), increased income worries (OR = 1.81, 95% CI = [1.54, 2.12]), fair or poor physical health (OR = 1.62, 95% CI = [1.36, 1.92]) or prior mental health conditions (OR = 3.27, 95% CI = [2.80, 3.82]). The odds of thoughts of self-harm were also higher among healthcare workers who identified as non-binary or preferred not to disclose their sex (cf. female: OR = 2.76, 95% CI = [1.35, 5.64]), although we note that the numbers in this category were small. Healthcare workers in primary or community care had lower odds of suicidal or self-harm thoughts than those working in medical specialty areas, such as respiratory medicine or infectious diseases (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = [0.58, 0.94]). Having dependent children was also protective against thoughts of suicide of self-harm (OR = 0.75, 95% CI = [0.61, 0.92]). There were no other significant associations between having thoughts of suicide or self-harm and other personal or workplace characteristics (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2.

Multivariable odds of thoughts of suicide or self-harm among healthcare workers.

Self-care and help-seeking behaviours among healthcare workers with and without thoughts of suicide or self-harm

Patterns of self-care and help-seeking varied between healthcare workers with and without suicidal ideation (Table 2). Those with thoughts of suicide or self-harm were less likely to have maintained or increased exercise or social connections (p < 0.001). Among the participants experiencing thoughts of suicide or self-harm, 47% (388/819) reported that they had sought professional support (Table 2), with 39% seeking help from a doctor or psychologist and 11% seeking support from an employee assistance programme or other professional support programme.

Table 2.

Self-care and help-seeking behaviours among healthcare workers.a

| Thoughts of suicide or self-harm (N = 819) | No thoughts of suicide or self-harm (N = 6976) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Self-care and informal help-seeking | Maintained or increased exercise | 469 (57) | 4666 (67) | <0.001 |

| Maintained or increased social connections | 188 (23) | 2279 (33) | <0.001 | |

| Used psychological health appb | 140 (17) | 968 (14) | 0.013 | |

| Help-seeking from professionals | Sought help from a doctor or psychologist | 320 (39) | 1106 (16) | <0.001 |

| Sought help from employee support programme or other professional support programme | 88 (11) | 382 (5) | <0.001 |

Participants could select more than one category.

Psychological health apps, such as SmilingMind, HeadSpace, Ten Percent Happier and Calm, guide users through a range of meditation, mindfulness and relaxation techniques.

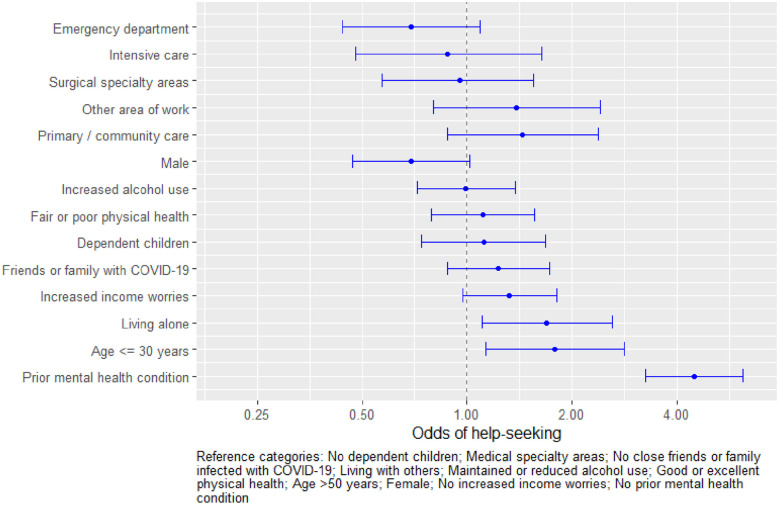

Healthcare workers with thoughts of suicide or self-harm were more likely to have sought support if were younger (⩽30 years cf. >50 years OR = 1.78, 95% CI = [1.13, 2.82]), if living alone (OR = 1.69, 95% CI = [1.10, 2.60]) or if they had prior mental health concerns (OR = 4.47, 95% CI = [3.25, 6.14]) (Figure 3). There were no other significant associations between seeking professional help and other personal or workplace characteristics (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 3.

Multivariable odds of help-seeking among healthcare workers with thoughts of suicide or self-harm.

Discussion

This large, national survey found that, among a convenience sample of nearly 10,000 Australian healthcare workers, 1 in 10 experienced thoughts of suicide or self-harm over a 2-week period during the pandemic. Healthcare workers with thoughts of suicide or self-harm experienced higher rates of depression, anxiety, PTSD and burnout than their peers. A range of personal, social and occupational characteristics were associated with thoughts of suicide or self-harm. Fewer than half of the healthcare workers experiencing thoughts of suicide or self-harm sought professional support.

Around the world, a growing body of research is revealing high rates of mental health symptoms, including burnout, depression and PTSD, among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020; Shaukat et al., 2020; Smallwood et al., 2021). Ours is the largest study to date to explore thoughts of suicide or self-harm among healthcare workers across all roles and settings.

The leading study of suicidal ideation among Australian doctors prior to the pandemic, conducted by Beyond Blue (Beyond Blue, 2019), found that 10.4% of doctors reported thoughts of suicide over a 12-month period. In our study, over 10% of healthcare workers reported thoughts of suicide or self-harm within the past 2 weeks suggesting that during the pandemic the 12-month prevalence is likely to be much higher.

Internationally, some smaller studies have explored suicidal ideation among healthcare workers during the pandemic. In the United States, a study of 225 doctors in New York found that 6.6% had thoughts of suicide or self-harm over the past 2 weeks, also using item 9 of the PHQ-9 (Al- Humadi et al., 2021). In Spain, the 30-day prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours among hospital workers during the first wave of the pandemic was estimated at 8.4% (Mortier et al., 2021). An analysis of 171 healthcare workers in Malaysia (Sahimi et al., 2021) found that 11.1% had current suicidal ideation. These rates are broadly similar to the estimates from our study. Further research is urgently needed to assess whether these high rates are persisting as the pandemic goes on and whether rates of self-harm and suicide among healthcare workers are increasing.

Consistent with previous studies, individuals in our study who reported thoughts of suicide or self-harm had significantly higher levels of depression (Forkmann et al., 2012), anxiety (Sareen et al., 2005), PTSD (Calabrese et al., 2011) and burnout (Dyrbye et al., 2008) than those without suicidal ideation. It is worth noting that – even among the healthcare workers without thoughts of suicide or self-harm – the rates of psychological distress among participants in our study were high, as discussed in previous publications from the Frontline Healthcare Workers Study (Smallwood et al., 2021).

The patterning of thoughts of suicide or self-harm reported by healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in our study echoes the well-recognised demographic risk factors for suicidal and self-harm ideation identified in previous research. In particular, thoughts of suicide or self-harm were more likely to occur among younger adults (Nock et al., 2008), men (Stocker et al., 2021), people experiencing financial stress (Elbogen et al., 2020), living alone (Farooq et al., 2021; Ge et al., 2017), and those with increased alcohol use (Borges et al., 2017), poor physical health (Ahmedani et al., 2017) or prior mental health disorders (Al-Humadi et al., 2021; Farooq et al., 2021; Nock et al., 2008). Healthcare workers with dependent children were less likely to report suicidal thoughts. which is consistent with previous research showing that having dependent children is a protective factor (Dehara et al., 2021).

The findings that healthcare workers with thoughts of suicide or self-harm were less likely to maintain exercise or social connections, and more likely to report increased alcohol use, deserve further exploration. The causality of these associations is unclear: we know that low physical activity, loneliness and alcohol use can contribute to, and be a consequence of, depression and suicidal ideation (Bennardi et al., 2019; Darvishi et al., 2015; Vancampfort et al., 2018). Nevertheless, further research could helpfully explore the role of social connection, exercise and substance use in the health of healthcare workers during the pandemic.

While multiple complex factors contribute to suicides among healthcare workers, a common theme is the presence of untreated or inadequately managed mental health conditions (Gold et al., 2013). Even among workers with frequent or near-daily thoughts of suicide or self-harm, fewer than half sought professional help, suggesting a significant unmet need for appropriate mental health care and support. Among those who did seek formal help, seeing a doctor or psychologist was the preferred formal support, being accessed more than employee assistance or professional support programmes.

Healthcare workers face both practical and cultural barriers to help-seeking. Practical barriers include long work hours, shift work, on-call commitments (Forbes et al., 2019) and limited availability of accessible and appropriate services. Cultural barriers included internalised, professional and institutional stigma around help-seeking for mental illness (Gerada, 2018). Some practitioners also fear being reported to a health regulator if they seek help, despite reassurance from the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency that mandatory reporting laws only apply where an impaired practitioner is placing the public at substantial risk of harm, and that engaging in treatment reduces this risk (Arroyo, 2020). A number of initiatives are seeking to address these barriers, including the expansion of health programmes for doctors, nurses and midwives, and the creation of peer support programmes (Bridson et al., 2021). It is encouraging that younger healthcare workers were more likely to seek help, suggesting that cultural norms may be changing. However, our findings suggest that more needs to be done.

Future implications

Against this background, we offer two practical suggestions to try and reduce the distress, and potential harm, associated with thoughts of suicide or self-harm among healthcare workers. First, governments, employers and professional bodies could use our findings to advocate for safer workplaces, and strengthen the support for those groups of healthcare workers at highest risk of thoughts of suicide or self-harm. This includes addressing structural issues, such as income insecurity, workplace stress, and social isolation.

Second, health regulators and practitioner health programmes should continue to explore and address the barriers to accessing and receiving help among healthcare workers who are experiencing thoughts of suicide or self-harm. Our findings suggest that, across Australia, many thousands of healthcare workers are going to work each day with thoughts that their life is not worth living or with thoughts of harming themselves. Yet, we have no clear way of connecting them with the care and support that they need.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest national study in the world to explore thoughts of suicide or self-harm among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. While previous studies of suicidal ideation among healthcare workers have focused on doctors and nurses, our study benefits from the inclusion of healthcare workers from all roles and areas of the health sector. The presence and frequency of thoughts of suicide or self-harm were assessed using item 9 of the PHQ-9, a validated tool which has been used in previous studies of practitioner health. Previous research has shown that responses to item 9 are associated with subsequent risk of suicide attempts and death (Rossom et al., 2017). While the positive predictive value of suicidal ideation as a marker for death by suicide is low, the presence of thoughts of suicide or self-harm indicates significant psychological distress and warrants a careful clinical assessment (McHugh et al., 2019).

Our study has limitations. Calculation of response rate was not possible due to the broad dissemination of the survey. Voluntary participation in the survey may have introduced selection bias, which may have resulted in over- or under-reporting of thoughts of suicide or self-harm. Like other international surveys exploring the mental health of healthcare workers during the pandemic, we were not able to confirm clinical diagnoses of mental illness with the symptoms measured by the validated psychological scales. Some studies have argued responses to item 9 of the PHQ-9 yield a high false-positive ratio by evaluating both the thought of passive death and desire for self-harm in a single-response question (Bauer et al., 2013) without enquiring about suicide plans, intent or actions. However, the scales we used are validated, have previously been used in studies of healthcare workers (Lim et al., 2020), and are the only feasible method for assessing mental health symptoms in a large-scale survey such as this.

It was not possible to collect baseline data due to the unexpected nature of the pandemic. Consequently, we were unable to compare rates before and during the pandemic, and we could not establish temporality of relationships: for example, increased alcohol use may have been a precursor, or response, to increased thoughts of suicide or self-harm.

Conclusion

This large national survey of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic found that more than 1 in 10 healthcare workers had thoughts of suicide or self-harm: a worryingly high proportion of those involved in frontline care. Yet most healthcare workers with thoughts of suicide or self-harm did not seek professional support.

The COVID-19 pandemic is far from over and will continue to disproportionately affect healthcare workers. Caring for those who care is both a moral imperative and a practical one: we cannot afford to lose healthcare workers to COVID-19 infection, nor to mental illness, self-injury or suicide. Strong and sustained action is needed from leaders of healthcare organisations, and from within the health professions, to ensure that healthcare workers are working in environments in which they feel safe and valued, and that those who do have thoughts of suicide and self-harm have ready access to social and professional supports which understand and meet their needs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-anp-10.1177_00048674221075540 for Thoughts of suicide or self-harm among Australian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic by Marie Bismark, Katrina Scurrah, Amy Pascoe, Karen Willis, Ria Jain and Natasha Smallwood in Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

The authors thank research assistant Anu Tayal for her contribution to the paper. They also acknowledge their co-investigators on the Australian COVID-19 Frontline Healthcare Workers Study.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Natasha Smallwood and Ria Jain are now affiliated to Department of Allergy, Immunology and Respiratory Medicine, Central Clinical School, The Alfred Hospital, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This paper was supported by NHMRC Emerging Leadership Investigator grant (grant no. APP1195984, grant title: Caring for Clinician Health and Wellbeing), The Royal Melbourne Hospital Foundation and The Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation.

ORCID iDs: Marie Bismark  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0114-2388

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0114-2388

Amy Pascoe  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3555-6856

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3555-6856

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Ahmedani BK, Peterson EL, Hu Y, et al. (2017) Major physical health conditions and risk of suicide. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 53: 308–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahpra (2019) 2018/2019 Annual report. Our National Scheme: For Safer Healthcare. Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Al- Humadi S, Bronson B, Muhlrad S, et al. (2021) Depression, suicidal thoughts, and burnout among physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey-based cross-sectional study. Academic Psychiatry 45: 557–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo D. (2020) AHPRA, mistrust, and medical culture in Australia. Australian Medical Student Journal 10: 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AM, Chan Y-F, Huang H, et al. (2013) Characteristics, management, and depression outcomes of primary care patients who endorse thoughts of death or suicide on the PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine 28: 363–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennardi M, Caballero FF, Miret M, et al. (2019) Longitudinal relationships between positive affect, loneliness, and suicide ideation: Age-specific factors in a general population. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 49: 90–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyond Blue (2019) National mental health survey of doctors and medical students. Available at: https://medicine.uq.edu.au/files/42088/Beyondblue%20Doctors%20Mental%20health.pdf (accessed 14 January 2022).

- Borges G, Bagge CL, Cherpitel CJ, et al. (2017) A meta-analysis of acute use of alcohol and the risk of suicide attempt. Psychological Medicine 47: 949–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridson TL, Jenkins K, Allen KG, et al. (2021) PPE for your mind: A peer support initiative for health care workers. Medical Journal of Australia 214: 8–11.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JR, Prescott M, Tamburrino M, et al. (2011) PTSD comorbidity and suicidal ideation associated with PTSD within the Ohio Army National Guard. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 72: 1072–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvishi N, Farhadi M, Haghtalab T, et al. (2015) Alcohol-related risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 10: e0126870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehara M, Wells MB, Sjöqvist H, et al. (2021) Parenthood is associated with lower suicide risk: A register-based cohort study of 1.5 million Swedes. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 143: 206–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. (2008) Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Annals of Internal Medicine 149: 334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Lanier M, Montgomery AE, et al. (2020) Financial strain and suicide attempts in a nationally representative sample of US adults. American Journal of Epidemiology 189: 1266–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, et al. (2008) Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 336: 488–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq S, Tunmore J, Ali W, et al. (2021) Suicide, self-harm and suicidal ideation during COVID-19: A systematic review. Psychiatry Research 306: 114228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes MP, Jenkins K, Myers MF. (2019) Optimising the treatment of doctors with mental illness. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 53: 106–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forkmann T, Brähler E, Gauggel S, et al. (2012) Prevalence of suicidal ideation and related risk factors in the German general population. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 200: 401–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L, Yap CW, Ong R, et al. (2017) Social isolation, loneliness and their relationships with depressive symptoms: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 12: e0182145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerada C. (2018) Doctors, suicide and mental illness. BJPsych Bulletin 42: 165–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold KJ, Sen A, Schwenk TL. (2013) Details on suicide among US physicians: Data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. General Hospital Psychiatry 35: 45–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS, Huguet N, McFarland BH, et al. (2007) Suicide among male veterans: A prospective population-based study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 61: 619–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, Saya GK, et al. (2020) Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research 293: 113382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. (2001) The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine 16: 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large M, Corderoy A, McHugh C. (2021) Is suicidal behaviour a stronger predictor of later suicide than suicidal ideation? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 55: 254–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim R, Van Aarsen K, Gray S, et al. (2020) Emergency medicine physician burnout and wellness in Canada before COVID-19: A national survey. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine 22: 603–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh CM, Corderoy A, Ryan CJ, et al. (2019) Association between suicidal ideation and suicide: Meta-analyses of odds ratios, sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value. BJPsych Open 5: e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzuk PM, Hartwell N, Leon A, et al. (2005) Executive functioning in depressed patients with suicidal ideation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 112: 294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. (1997) Maslach Burnout Inventory. In: Zalaquett CP, Wood RJ. (eds) Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Education, pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi T, Sawada Y, Ueda M. (2013) Natural disasters and suicide: Evidence from Japan. Social Science & Medicine 82: 126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner AJ, Maheen H, Bismark MM, et al. (2016) Suicide by health professionals: A retrospective mortality study in Australia, 2001–2012. Medical Journal of Australia 205: 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortier P, Vilagut G, Ferrer M, et al. (2021) Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviors among hospital workers during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 outbreak. Depression and Anxiety 38: 528–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. (2008) Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. The British Journal of Psychiatry 192: 98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie K, Crawford J, Baker ST, et al. (2019) Interventions to reduce symptoms of common mental disorders and suicidal ideation in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry 6: 225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie K, Crawford J, LaMontagne AD, et al. (2020) Working hours, common mental disorder and suicidal ideation among junior doctors in Australia: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 10: e033525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie K, Crawford J, Shand F, et al. (2021) Workplace stress, common mental disorder and suicidal ideation in junior doctors. Internal Medicine Journal 51: 1074–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkis J, Burgess P, Dunt D. (2000) Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Australian adults. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention 21: 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romo V. (2020) NYC emergency room physician who treated coronavirus patients dies by suicide. NPR, 28 April. Available at: www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/28/847305408/nyc-emergency-room-physician-who-treated-coronavirus-patients-dies-by-suicide (accessed 14 January 2022).

- Rossom RC, Coleman KJ, Ahmedani BK, et al. (2017) Suicidal ideation reported on the PHQ9 and risk of suicidal behavior across age groups. Journal of Affective Disorders 215: 77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahimi HMS, Mohd Daud TI, Chan LF, et al. (2021) Depression and suicidal ideation in a sample of Malaysian healthcare workers: A preliminary study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. (2005) Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: A population-based longitudinal study of adults. Archives of General Psychiatry 62: 1249–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaukat N, Ali DM, Razzak J. (2020) Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: A scoping review. International Journal of Emergency Medicine 13: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood N, Karimi L, Bismark M, et al. (2021) High levels of psychosocial distress among Australian frontline health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. General Psychiatry 72: 124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine 166: 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker R, Tran T, Hammarberg K, et al. (2021) Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) and General Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) data contributed by 13,829 respondents to a national survey about COVID-19 restrictions in Australia. Psychiatry Research 298: 113792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoresen S, Tambs K, Hussain A, et al. (2010) Brief measure of posttraumatic stress reactions: Impact of Event Scale-6. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 45: 405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uvais N. (2021) Suicide of doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders 23: 20com02867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D, Hallgren M, Firth J, et al. (2018) Physical activity and suicidal ideation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 225: 438–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-anp-10.1177_00048674221075540 for Thoughts of suicide or self-harm among Australian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic by Marie Bismark, Katrina Scurrah, Amy Pascoe, Karen Willis, Ria Jain and Natasha Smallwood in Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry