Abstract

Objective:

The main aim of this study was to assess food taboos and associated factors among pregnant women in eastern Ethiopia.

Methods:

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among randomly selected 422 pregnant women at Haramaya Demographic Surveillance System from Haramaya District, eastern Ethiopia. Data on sociodemographic conditions, the presence of food taboos, and perceived reasons were collected using the face-to-face interview method by trained data collectors through arranged home visits. Collected data were entered into EpiData 3.1 and exported to statistical package for social sciences version 23 for cleaning and analysis. Descriptive, binary, and multiple logistic regression analyses were carried out to determine the relationship between explanatory and outcome variables. Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) at p value less than 0.05 was used to declare significant association.

Results:

Approximately half (48%, 95% CI: 43%, 52%) of the pregnant women reported the presence of pregnancy-related food taboos. Pregnant women who have heard about food taboos (AOR: 3.58; 95% CI: 1.89, 6.83), pregnant women had friends who avoided food (AOR: 1.91; 95% CI: 1.22, 2.99), women’s monthly income ⩽840 ETB (AOR: 1.73; 95% CI: 1.10, 2.73), and pregnant women who had not attended formal education (AOR: 1.95; 95% CI: 1.18, 3.23) were more likely to report food taboos. The odds of pregnant women who had attended uptake of immunization services were less likely to have food taboos (AOR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.21, 0.58).

Conclusion:

Pregnancy-related food taboos among pregnant women are unacceptably high. Therefore, awareness creation and nutritional counseling at health service delivery points are imperative actions for pregnant women to avoid food taboos norms. Further research should be done to understand the social and cultural ground of food taboos during pregnancy.

Keywords: Food taboos, pregnant women, Haramaya, eastern Ethiopia

Introduction

More than 3.5 million women in low-income countries die each year due to the underlying cause of undernutrition.1 Improving the nutritional status of women before and during pregnancy can reduce the risk of adverse birth outcomes. However, poor maternal nutrition at the earliest stages of the life course, during fetal development, can induce both short-term and longer-lasting effects.2–4 Nutrition has never been as high on the international public health agenda as it is today. The adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the United Nations’ proclamation of a Decade of Action on Nutrition (2016–2030) are signals that indicate strong action is required relating to food and nutrition of pregnant women.4

Women’s nutritional need increases during pregnancy and lactation. Micronutrient supplements, adequate energy intake, diversified diet, using fruit, vegetables, and animal products throughout the life cycle help to ensure the women enter pregnancy and lactation without deficiencies.5 Micronutrient supplementations can improve maternal nutritional status to achieve fetal and postnatal growth and development.6,7 In addition to the increased demand for nutrition due to pregnancy itself, pregnancy-related food restrictions (taboos) of some essential nutrients due to cultural reasons affect the nutritional status of pregnant women.8 Women who had food taboos during pregnancy would have an increased likelihood of developing a range of adverse pregnancy outcomes, which have a range of influence on maternal health and fetal growth and development.9,10 The effect of maternal undernutrition on fetal growth retardation, low birth weight, poor pregnancy outcomes, premature birth, and other micronutrients deficiency disorders is well established.11,12 In addition, avoiding food items during pregnancy might have long-term impacts on the mother and fetus, which put the baby easily susceptible to disease during childhood.13

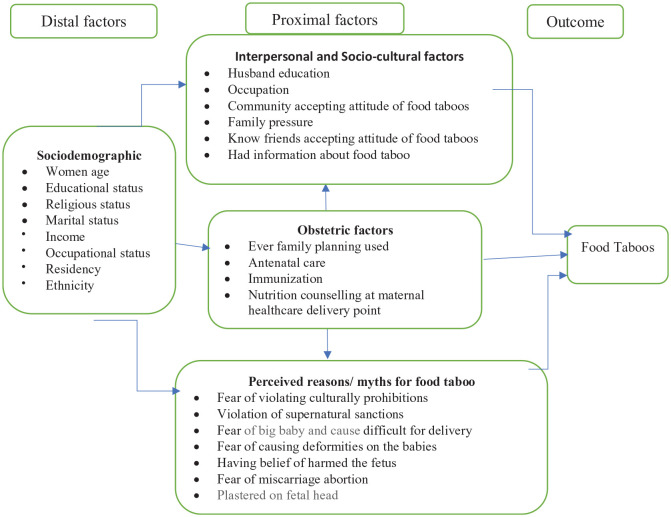

Communities’ traditionally held beliefs, sociocultural factors, and family pressure contribute to food taboos.8,14,15 Pregnancy-related food taboos are barriers to the first 1000 days of essential nutrition actions for improving adequate maternal and child nutrition.2,3 In Ethiopia, one of the nutrition-associated maternal health problems is iron deficiency anemia, which has shown a very sluggish decline from 27% in 200516 to 24% in 2016.17 Pregnancy-related food taboos have been contributing to the burden of poor maternal health in Ethiopia. Iron deficiency anemia was high among women who had pregnancy-related food taboos.15 Although maternal malnutrition might be jeopardized by sociocultural restrictions of some food items during pregnancy, evidence on the level of food taboos is limited in Ethiopia in the general and the eastern part in particular. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess the level of food taboos and its associated factors among pregnant women in the Haramaya Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS), Eastern Ethiopia. The link of explanatory variables with outcome variable (food taboos) is illustrated using an adapted conceptual framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adapted conceptual framework to illustrate the relationship between explanatory and outcome variables.

Methods

Study setting and design

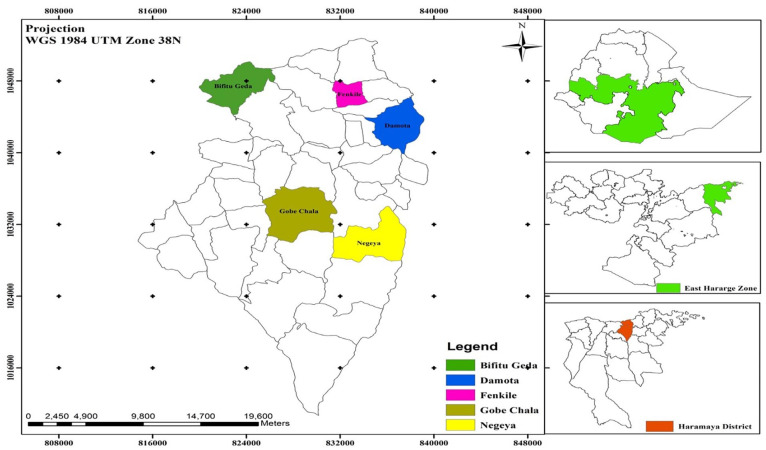

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among pregnant women participating in the ongoing Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) found in Haramaya District, East Hararghe Zone, Oromia Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia, located 500 km away from Addis Ababa. The HDSS was established in 2018 and covers 12 rural sub-districts/ “kebeles” (smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia) out of the total 36 sub-districts (which is the smallest functional administrative unit in Ethiopia) in Haramaya District (see map of the study area in Figure 2). Every 6 months, HDSS enumerators visit all residents in the selected sub-districts and collect data on key demographic events: births, deaths, pregnancy, and migration. The HDSS updates its dataset every 6 months to accommodate demographic and health changes among the residents. Pregnancy status has been registered by the HDSS since its inception, and a total of 994 women were registered in HDSS during the study period. The study was conducted from 1 to 31 July 2020.

Figure 2.

Geographic location of study area.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Pregnant women who have lived in the district and under the Hararghe HDSS follow-up were eligible and included in the study. However, seriously ill pregnant woman during data collection and unable to communicate were excused from the study.

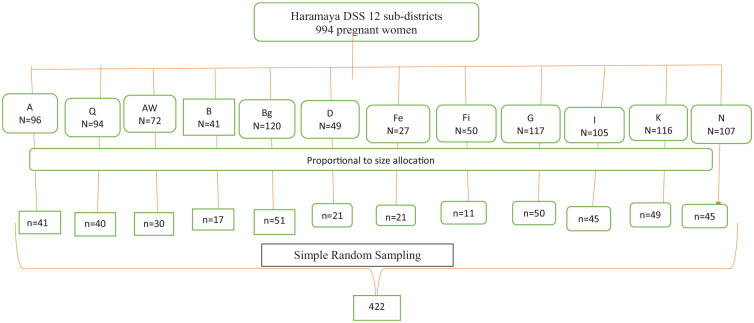

Population and sampling procedure

All pregnant women living in Haramaya District constituted the source population. The study population included all pregnant women (n = 994) residing in the Haramaya HDSS sub-districts during the study period. The sample size was calculated using single proportion formula by considering 95% significance level, 5% marginal error, and pregnancy-related food taboos (49.8%).9 Then 10% of the calculated sample was considered for potential non-responses compensation. Finally, the calculated sample size was 422. The location of the pregnant woman was obtained from the Haramaya HDSS household registry and updated in collaboration with the community health extension workers (HEWs) and HDSS site supervisors. A total of 12 sub-districts in Haramaya HDSS were included in this study. The calculated sample size was proportionally allocated to each selected sub-district. The details of the sampling procedure are illustrated using Figure 3. The sampling frame was constructed for each sub-district using the HDSS household registration number after separating households with pregnant women only. Then, study participants were recruited using simple random sampling-applied lottery method.

Figure 3.

Schematic presentation of the sampling procedure.

Data collection tools, methods, and procedures

A structured questionnaire (tool) was adapted from different studies on food taboos or restrictions during pregnancy,9,18–23 which comprised women’s sociodemographic variables, obstetric history, maternal health service utilization (specifically, antenatal care (ANC), Tetanus Toxoid (TT) vaccination, and nutritional counseling), and pregnancy related food taboos (restrictions), types of food items avoided and perceived reason for pregnancy-related food taboos. The questionnaire was initially prepared in English then translated to “Afaan Oromo” and backtranslated to English by individuals with good command of both languages. The adapted data collection tool was reviewed and pretested in local context prior to main data collection. The pretest was carried out at nearby HDSS before the actual data collection period on 21 (5%) women participating in Harar HDSS to ensure clarity, wordings, logical sequence, and skip patterns. Five data collectors and two supervisors were recruited from Haramaya HDSS considering their experience. A daylong training was given to both the data collectors and supervisors. Then data were collected through face-to-face interviews at the women’s home in a quiet and private place. In addition, supportive supervision was provided throughout the data collection period by trained supervisors. The filled questionnaires were checked for completeness and consistency. Then proper coding, entry into EpiData, and data cleaning were performed to ensure the quality of the study finding.

Statistical analysis

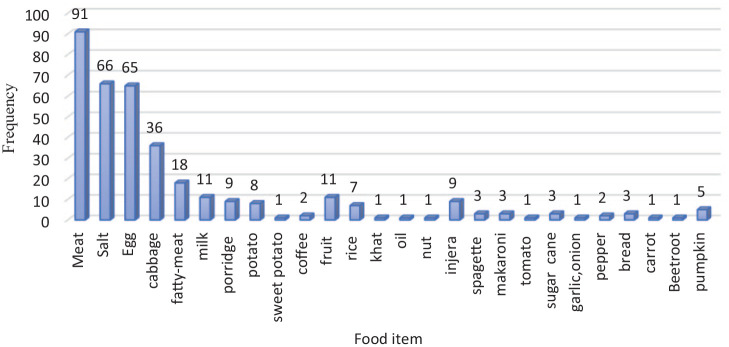

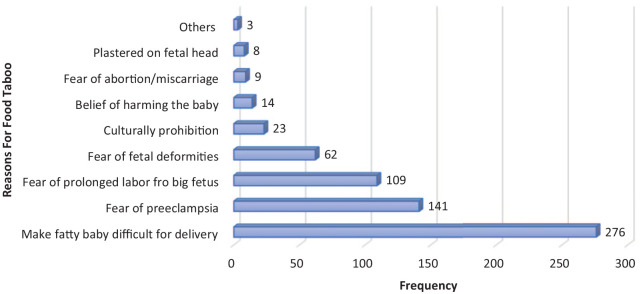

All checked data were coded, entered into EpiData 3.1, and exported to Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) 23 for cleaning and analysis. Food taboo was considered when a pregnant woman reported restrictions (avoided) of at least one previously usual food item due to being pregnant.24 Food taboo was dichotomized as restricted for at least one usual food item (yes = 1) and not restricted to any usual food item (no = 0) (Figure 4). Likewise, perceived reasons were assessed using open questions with multiple responses possible (Figure 5). Descriptive statistical analysis was performed to determine frequencies, proportion, mean, and standard deviation. Binary logistic regression was carried out to examine the association between 20 explanatory variables with women’s food taboos. Of these, variables with a p value less than 0.25 were entered into the multiple logistic regression model to control for possible confounders after checking for multicollinearity between independent variables. Model fitness was checked using Hosmer–Lemeshow test to show the goodness-of-fit.25 Multiple logistic regression model was fitted to determine adjusted odds ratios (AOR) at 95% CI to identify factors associated with food taboos. Finally, significant association was declared using AOR at 95% CI and p value <0.05.

Figure 4.

Commonest tabooed food items reported by women during pregnancy in HDSS, 2020 (Multiple responses were possible).

Figure 5.

Perceived reasons for pregnancy-related food taboo in HDSS, 2020 (multiple responses were possible).

NB: Others: women’s fear of being fatty (1), fear violating social norm (1), and to ease process of births (1).

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

From a total of 422 pregnant women approached, 416 (98.6%) were included in the study. The mean age of the pregnant women was 28.6 (± 9.7) years. The median monthly income was 840 ETB. Likewise, the mean family size of the women was 5.8(± 5.2) members (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant women in Haramaya HDSS, July 2020.

| Variables | Categories | n = 416 | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 28.6 (±9.7) years | ||

| Age (years) | <20 | 18 | 4.4 |

| 20–34 | 325 | 79.1 | |

| 35–49 | 68 | 16.5 | |

| Marital status | Single | 19 | 4.6 |

| Married | 397 | 95.4 | |

| Religion | Muslim | 413 | 99.3 |

| Orthodox | 3 | 0.7 | |

| Residence | Rural | 412 | 99.0 |

| Urban | 4 | 1.0 | |

| Women education | No formal education | 303 | 72.8 |

| Grade 1–6 | 94 | 22.6 | |

| Grade 7–12 | 19 | 4.6 | |

| Ethnicity | Oromo | 411 | 98.8 |

| Others* | 5 | 1.2 | |

| Woman occupation | Housewife | 379 | 91.1 |

| Private business | 37 | 8.9 | |

| Husband’s education | Illiterate | 282 | 67.8 |

| Read and write | 10 | 2.4 | |

| Grade 11–6 | 79 | 19.0 | |

| Grade 7–12 | 44 | 10.6 | |

| >12 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Husband occupation | Farmer | 407 | 97.8 |

| Others* | 9 | 2.2 | |

| Family size | ⩽5 | 216 | 52.4 |

| ⩾6 | 196 | 47.6 | |

| Estimated monthly household income (ETB) | ⩽840 | 211 | 50.8 |

| ⩾841 | 204 | 49.2 |

Others* husband occupation: Private employee (7), government employee (1), and NGOs employee (1); ethnicity: Amhara (2) and Somali (3).

Obstetric history of the pregnant women

Approximately half (47.1%) of the pregnant women had booked ANC follow-up. Of these, 76.6% of the women received nutritional counseling during ANC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetric history of the pregnant women in Haramaya HDSS, July 2020 (n = 416).

| Variables | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Had ANC booked? | Yes | 196 | 47.1 |

| No | 220 | 52.9 | |

| Number of ANC visits | 1 | 78 | 40.2 |

| 2 | 74 | 38.1 | |

| 3 | 36 | 18.6 | |

| 4 | 6 | 3.1 | |

| Received nutrition counseling during ANC visit | Yes | 151 | 76.6 |

| No | 45 | 22.8 | |

| Received nutrition counseling at previous family planning | Yes | 79 | 75.2 |

| No | 25 | 24.8 | |

| Received TT immunization service | Yes | 189 | 45.4 |

| No | 227 | 54.6 | |

| Received nutrition counseling during visits for immunization | Yes | 110 | 57.6 |

| No | 79 | 42.4 |

The magnitude of food taboos and perceived reasons

A total of 200 (48%; 95% CI: 43%, 52%) women reported the presence of food taboos during pregnancy period. Furthermore, two-thirds (66.8%) of the respondents had heard about food taboos, mainly from other pregnant women (50.7%). Of these, 50.5% listed some food items that should be avoided during pregnancy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Food taboos among pregnant women in Haramaya HDSS, July 2020 (n = 416).

| Variables | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever heard about food taboos | Yes | 278 | 66.8 |

| No | 138 | 33.2 | |

| Source of informationa | TV/radio | 19 | 6.8 |

| Health personnel | 84 | 30.2 | |

| Community HEWs | 56 | 20.1 | |

| Neighbors | 141 | 50.7 | |

| Family (mother-in-law) | 70 | 25.2 | |

| Knew community member with food taboos | Yes | 208 | 50.0 |

| No | 203 | 48.8 | |

| Not reported | 5 | 1.2 | |

| Women had known friends who avoided foods during pregnancy | Yes | 163 | 39.2 |

| No | 239 | 57.5 | |

| Not reported | 14 | 3.4 | |

| Early pregnancy | 68 | 16.4 | |

| Mid pregnancy | 212 | 51.0 | |

| Late pregnancy | 178 | 42.8 | |

| Had food taboos during pregnancy | Yes | 200 | 48.0 |

| No | 216 | 52.0 |

Multiple responses were possible.

The commonest food items that were avoided include meat, salt, egg, cabbage, milk, and oil (Figure 4).

Major reasons for food taboos were fear of having big baby that may cause difficulty during delivery, fear of increasing blood pressure, fear of prolonged labor, fear of fetal body deformities, and adherence to cultural prohibitions (Figure 5). Furthermore, pregnant women reported different reasons for different food item restrictions during pregnancy. Pregnant women had food taboos from eating egg, meat, milk, fruits (mainly mango), and vegetables (mainly cabbage) due to fear of violating sociocultural norms in their community. Likewise, pregnant women were not eating meat during pregnancy due to fear of fetal deformities. Table 4 demonstrates the match of the communities’ perceived reason, and tabooed food is presented in detail.

Table 4.

Match of tabooed food and perceived consequences among pregnant women at Haramaya HDSS, July 2020.

| To ease birth process | The belief of harming the baby | Cultural prohibition | Culturally prohibition | Fear of miscarriage | Fear of being fatty | Fear of fetal deformities | Fear of preeclampsia | Fear of prolonged labor | Fear of violating social culture | Make big baby and difficult for delivery | Plastered on fetal head | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Cabbage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| Cabbage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Chickpea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Coffee | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Egg | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 55 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 41 | 0 | 1 | 115 |

| Egg, fruit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Fatty meat | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| Fish | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Fruit | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 67 | 1 | 0 | 80 |

| Fruits (mango, banana, and papaya) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Honey | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 19 |

| Lentil | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Meat | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 65 | 7 | 0 | 67 | 1 | 1 | 152 |

| Milk | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| Oil | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Onion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Papaya | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Porridge | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 21 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 43 |

| Potato | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 21 |

| Pumpkin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Salt | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 29 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 64 |

| Sugarcane | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 11 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| Vegetables | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Yogurt | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

Multiple responses were possible. Different colors are given to indicate the match between food items with different reasons for food taboos during pregnancy, and label with numbers to show frequencies. Zero “0” is given for no-responses and shaded with same color.

Factors associated with pregnancy-related food taboos

Of a total of 20 explanatory variables considered in the binary logistic regression, 9 of them were found to be a candidate (p < 0.25) for the multiple logistic regression analysis. In the multiple logistic regression, five variables remained statistically significant association: ever heard about food taboos, having friends who avoided food, women had not attended formal education, monthly income, and had immunization service. Women who have ever heard about food taboos were 3.58 times more likely to report food taboos than women who had not heard about food taboos (AOR: 3.58, 95% CI:1.89, 6.83). Likewise, women who had friends with food taboos were 1.91 times more likely to have food taboos than their counterparts (AOR: 1.91, 95% CI: 1.22, 2.99). Women who had not attended formal education were 1.95 times more likely to report food taboos than those who had attended formal education (AOR: 1.95, 95% CI: 1.18, 3.23). Furthermore, women with monthly income below the median (840 ETB) were 1.73 times more likely to report food taboos than their counterparts (AOR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.10, 2.73). However, the odds of food taboos among women who had immunization service was 65% less likely to occur compared to women with no history of attending immunization service (AOR: 0.35, 95% CI: 0.21, 0.58) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with food taboos among pregnant women in Haramaya DSS, July 2020 (n = 416).

| Variables | Categories | Food taboo | COR 95% CI | AOR 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | ||||

| Age (years) | <20 | 4 (22.2) | 14 (77.8) | 0.43 (0.13, 1.46) | 0.31 (0.08, 1.15) |

| 20–34 | 164 (50.5) | 161 (49.5) | 1.55 (0.91, 2.63) | 1.26 (0.70, 2.27) | |

| 35–49 | 27 (39.7) | 41 (60.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Women’s education status | No formal education | 60 (53.1) | 53 (46.9) | 1.35 (0.88, 2.09)* | 1.95 (1.18, 3.23)* |

| Formal education | 138 (45.5) | 165 (54.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Women’s occupation | Housewife | 181 (47.8) | 198 (52.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Private business | 17 (45.9) | 20 (54.1) | 0.93 (0.47,1.83) | ||

| Husband education status | No formal education | 138 (47.3) | 154 (52.7) | 1.00 | |

| Formal education | 60 (48.4) | 64 (51.6) | 1.05 (0.69, 1.59) | ||

| Family size | ⩽5 | 100 (46.3) | 116 (53.7) | 0.88 (0.60, 1.30) | |

| ⩾6 | 97 (49.5) | 99 (50.5) | 1.00 | ||

| Monthly income (ETB) | ⩽840 | 107 (50.7) | 104 (49.3) | 1.30 (0.89, 1.92)* | 1.73 (1.10, 2.72)* |

| ⩾841 | 90 (44.1) | 114 (55.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Gravida | ⩽4 | 105 (46.7) | 120 (53.3) | 0.92 (0.63, 1.36) | |

| ⩾5 | 93 (48.7) | 98 (51.3) | 1.00 | ||

| Para | ⩽4 | 128 (46.9) | 145 (53.1) | 0.92 (0.61, 1.38) | |

| ⩾5 | 70 (49.0) | 73 (51.0) | 1.00 | ||

| ANC follow | Yes | 101 (51.5) | 95 (48.5) | 1.35 (0.92, 1.98) | |

| No | 97 (44.1) | 122 (55.5) | 1.00 | ||

| No. of ANC | Once | 47 (60.3) | 31 (39.7) | 1.00 | |

| Twice | 35 (47.3) | 39 (52.7) | 0.59 (0.31, 1.13) | ||

| Three times | 15 (41.7) | 21 (58.3) | 0.47 (0.21, 1.05) | ||

| Four times | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 0.66 (0.13, 3.48) | ||

| Nut counseling at ANC | Yes | 77 (51.0) | 74 (49.0) | 0.95 (0.49, 1.85) | |

| No | 24 (52.2) | 22 (47.8) | 1.00 | ||

| FP service used | Yes | 39 (37.5) | 65 (62.5) | 0.58 (0.37, 0.91)* | 0.65 (0.37, 1.14) |

| No | 159 (51.0) | 153 (49.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Nut counseling at FP | Yes | 29 (36.7) | 50 (63.3) | 1.00 | |

| No | 10 (38.5) | 16 (61.5) | 1.08 (0.43, 2.69) | ||

| Immunization service | Yes | 73 (38.6) | 116 (61.4) | 0.51 (0.35, 0.76)* | 0.35 (0.21, 0.58)* |

| No | 125 (55.1) | 102 (44.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Nut counseling at immunization | Yes | 43 (39.1) | 67 (60.9) | 0.98 (0.55, 1.77) | |

| No | 32 (39.5) | 49 (60.5) | 1.00 | ||

| Heard about the food taboo | Yes | 155 (55.8) | 123 (44.2) | 2.78 (1.81, 4.28)* | 3.59 (1.89, 6.83)* |

| No | 43 (31.2) | 95 (68.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Knew a food item to be avoided | Yes | 114 (54.3) | 96 (45.7) | 1.73 (1.17, 2.54)* | 1.18 (0.64, 2.18) |

| No | 84 (40.8) | 122 (59.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| The community has food taboos | Yes | 102 (49.0) | 106 (51.0) | 1.12 (0.76,1.65) | |

| No | 96 (46.2) | 112 (53.8) | 1.00 | ||

| Women had friends who avoided food | Yes | 97 (59.5) | 66 (40.5) | 2.21 (1.48, 3.30)* | 1.91 (1.22, 2.99)* |

| No | 101 (39.9) | 152 (60.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

NB: *COR (crude odds ratio): p < 0.25, and *AOR (adjusted odds ratio): p < 0.05; CI: confidence interval.

Discussion

This study determined the prevalence of food taboos and its associated factors among pregnant women in women participating in an ongoing HDSS Haramaya District, Eastern Ethiopia. Almost half of the women in this study reported avoiding some foods because of their pregnancy. Pregnancy-related food taboos were more likely among women who heard about food taboos, who had friends avoiding food, low monthly income, and women who had not attended formal education. However, women who reported attending an immunization service during their pregnancy were less likely to have food taboos. Fear of delivering a big baby, fear of causing fetal anomaly/deformities or harming the newborns, and cultural prohibition were some of the most frequently reported perceived reasons by pregnant women for their food taboos.

Our finding is similar with the studies conducted in Ethiopia that ranged from 42% to 49%9,13,26 and a study in Sudan (44%).27 Nevertheless, our finding is much higher than the finding from some other studies conducted in Ethiopia, in which the prevalence of food taboos ranged from 12% to 27%,15,21,22,28 a study in Nigeria,29,30 Sudan,31 and South Africa,32 which reported a prevalence of food taboos ranging from 13% to 37%. This difference might be due to the study settings, where almost all respondents in our study were rural residents who had not attended formal education, which may affect their awareness level and had misconceptions or perceived reasons for food taboos. Nevertheless, this finding is lower as compared with studies conducted in Ethiopia that reported pregnancy-related food taboos ranged 55%–68%,20,33 57% in Ghana,34 64% in South Africa (64%),35 70% in Malaysia (70%),19 and 65% in India.36 Congruent with similar studies, the most frequently mentioned reason for food taboos was fear of delivering a big baby, and cultural prohibitions of eating tabooed food during pregnancy.13,20,22 In addition, pregnant women in this study raised similar reason for food taboos with a study conducted in Sudan,31 South Africa,32 and Ghana reported cultural compassion,34 and in Malaysia,19 revealed that the most common perceived reasons for avoiding foods were fear of born a baby with deformities and fear of difficult of delivering big baby.

Women who had not attended formal education, heard about food taboos, and income was more likely to report food taboos. The fact that women who had no formal education reported having food taboos compared to their counterparts. This indicates the deep-rooted nature of the condition and how strong cultural beliefs affect food taboos which is quite consistent with the findings of studies conducted in Ethiopia,9,22,23,35 Nigeria,29,30,37 Ghana,34 South Africa,35 and India,38 which have reported that women’s low education attainment was one of the significantly associated factors with food taboos.

In addition, this study finding is consistent with another study in Ethiopia21 and Ghana,34 indicated that monthly income has associated with food taboo. Similarly, this study finding is consistent with the finding of previous study from South Africa women who have heard about food taboos more likely to have food taboos.32 Furthermore, in this study, pregnant women who had been vaccinated for TT were less likely to experience food taboos. This might be linked with counseling service (literacy service) at immunization point by health care providers, and also mostly women who have awareness may utilize such type of service. This finding is consistent with a study done in India, which has indicated that literacy status at antenatal, parity, and postnatal has been associated with special food consumption.36 Several myths, misconceptions, and cultural prohibitions for food taboo during pregnancy are identified in this study which have high implication maternal malnutrition and birth outcome in Ethiopia. Therefore, further research should be conducted to explore the reasons for food taboos and its effect on maternal and fetal nutritional status and birth outcomes. Hence, clinicians and public health programmers should exert efforts to provide nutritional counseling at any maternal health care delivery points to reduce myths and misconceptions

Being a community-based study and covering all the 12 sub-districts in the HDSS; applied probability sampling method with scientifically determined sample size; and potential confounders were controlled using multiple logistic regression analysis that could be considered as a strength of this study. Nevertheless, the study was not conducted without limitation. As a result of homogeneity within the population (e.g. ethnicity, religion, and residency), this study could not appreciate the influence of sociodemographic variation on food taboos. In addition, it was a cross-sectional study design that may not be strong enough to declare the causal effect relationship, and data relied on pregnant women’s self-report which are prone to social desirability bias may limit women’s disclosure of food taboos due to cultural prohibition. Therefore, the authors recommend a further study to assess the cultural factors that influence pregnant women’s food restriction using robust design.

Conclusion

Approximately half of the study participants reported having pregnancy-related food taboos. Meat, salt, sugarcane, porridge, honey, and several fruits and vegetables were the most avoided food items. Pregnancy-related food taboo was more likely among pregnant women who had heard about food taboo, had friends with food taboo, had formal education, and women from low socioeconomic status. Pregnancy-related food taboos were less likely among women who had attended immunization services. We suggest comprehensive and contextualized interventions should be designed by concerned stakeholders to address common reasons (myths and misconceptions) for pregnancy-related food taboos and encourage them to take essential nutrients for their health and beyond. In addition, further research is needed to understand the sociocultural factors in the context that leads to pregnancy-related food restrictions.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-smo-10.1177_20503121221133935 for Food taboos among pregnant women and associated factors in eastern Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study by Wbalem Amare, Abera Kenay Tura, Agumasie Semahegn and Kedir Teji Roba in SAGE Open Medicine

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Haramaya University, College of Health and Medical Sciences, for the overall support. They also thank all the data collectors, supervisors, and study participants for their contributions.

Footnotes

Author’s contribution: W.A., A.K.T., A.S., and K.T.R. had been involved since the conceptualization of the research question, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. W.A. and A.S. drafted the article. All authors reviewed and contributed intellectual inputs, and approved the article for submission.

Availability of data and materials: The raw data in EpiData and SPSS are available; we can make it available to share participants’ de-identified dataset on official requests.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee of College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Ethiopia. (Ref_No. IHRERC/119/2020).

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was part of the MPH Thesis work of W.A. No funding was obtained, and expenses for data collection were covered by W.A.

Informed consent: Informed voluntary verbal and written consent was obtained from all participants. Written informed consent from parents/legal guardian and assent from them were obtained from study participants whose age are younger than 18 years, and also not attended formal education. The study was conducted on adult pregnant women who can give consent to participate. Participants’ information was kept confidential using anonymous questionnaires and use of codes. Personal privacy and cultural norms were respected. The respondents were informed of their right not to participate in the study or withdraw from the study at any time without affecting their participation in the HDSS.

ORCID iD: Agumasie Semahegn  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6625-8184

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6625-8184

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Robert. Nutritional status in rural Nigeria. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008; 53: 734–739. [Google Scholar]

- 2. USAID. Maternal Nutrition Programming in the context of the 2016 WHO Antenatal Care Guidelines: For a positive pregnancy experience. Maternal and Child Survival Program, 2018, https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/resource/maternal-nutrition-programming-in-the-context-of-the-2016-who-antenatal-care-guidelines-for-a-positive-pregnancy-experience/

- 3. USAID. Maternal nutrition for girls and women; Multi-sectoral Nutrition Strategy 2014–2025. Technical Guidance Brief, 2014, https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1864/maternal-nutrition-for-girls-women-508-3.pdf

- 4. WHO. Good maternal nutrition the best start in life. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Core Group. Maternal nutrition during pregnancy and lactation: Linkages Dietary Guide. Core Group 2004. https://coregroup.org/resource-library/maternal-nutrition-during-pregnancy-and-lactation/

- 6. Hambidge KM, Krebs NF. Strategies for optimizing maternal nutrition to promote infant development. Reprod Health 2018; 15(Suppl. 1): 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kind KL, Moore VM, Davies MJ. Diet around conception and during pregnancy—effects on fetal and neonatal outcomes. Reprod Biomed Online 2006; 12(5): 532–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patil R, Mittal ADRV, Khan MI, et al. Taboos and misconceptions about food during pregnancy among rural population of Pondicherry Rajkumar. Calicut Med J 2010; 8(2): e4. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Biza Zepro N. Food taboos and misconceptions among pregnant women of Shashemene District, Ethiopia, 2012. Sci J Public Heal 2015; 3(3): 410–416. [Google Scholar]

- 10. ASA. Pregnancy as a time for dietary changes. Proc Nut Soc 2001; 60(6): 497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abu-Saad K, Fraser D. Maternal nutrition and birth outcomes. Epidemiol Rev 2010; 32(1): 5–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muthayya S. Maternal nutrition & low birth weight—what is really important? Indian J Med Res 2009; 130(5): 600–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gebremariam H. Food taboos during pregnancy and its consequence for the mother, infant and child in Ethiopia: a systemic review. Int J Pharm Biol Sci Fundam 2017; 13(2): 2520. [Google Scholar]

- 14. McNamara K, Wood E. Food taboos, health beliefs, and gender: understanding household food choice and nutrition in rural Tajikistan. J Health Popul Nutr 2019; 38: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mohammed SH, Taye H, Larijani B, et al. Food taboo among pregnant Ethiopian women: magnitude, drivers, and association with anemia. Nutr J 2019; 18(1): 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. CSA. Central Statistica Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ORC, 2005. Ethiopia demographic and health survey, 2005. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; ORC Macro Calverton, Maryland, USA. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17. CSA. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: CSA and ICF, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Daba G, Beyene F, Fekadu H, et al. Assessment of knowledge of pregnant mothers on maternal nutrition and associated factors in Guto Gida Woreda, East Wollega Zone, Ethiopia. J Nutr Food Sci 2013; 3: 6. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mohamad M, Ling CY. Food taboos of Malay pregnant women attending antenatal check-up at the maternal health clinic in Kuala Lumpur, 2016, https://www.oatext.com/Food-taboos-of-malay-pregnant-women-attending-antenatal-check-up-at-the-maternal-health-clinic-in-Kuala-Lumpur.php

- 20. Wondimu R. Food taboo and its associated factors among pregnant women in Sendafa Beke town, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Int J Sci Tech Soc 2019; 9: 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Getnet W, Aycheh W, Tessema T. Determinants of food taboos in the pregnant women of the Awabel District, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Regional State in Ethiopia. Adv Public Heal 2018; 2018: 9198076. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Demissie T, Muroki N, Kogi-makau W. Food taboos among pregnant women in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Heal Dev 1998; 12(pp. 1): 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zerfu TA, Umeta M, Baye K. Dietary habits, food taboos, and perceptions towards weight gain during pregnancy in Arsi, rural central Ethiopia: a qualitative cross-sectional study. J Health Popul Nutr 2016; 35: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meyer-Rochow VB. Food taboos: their origins and purposes. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 2009; 5: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bartlett J. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test for logistic regression, 2014, https://thestatsgeek.com/2014/02/16/the-hosmer-lemeshow-goodness-of-fit-test-for-logistic-regression/

- 26. Obse N, Mossie A, Gobena T. Magnitude of anemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Shalla worda, weste Arsi Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Heal Sci 2013; 23(2): 165–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tahir HMH, Ahmed AEEM, Mohammed NAA. Food taboos among pregnant women in health centers, Khartoum State. Int J Sci Heal Res 2018; 3(1): 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tela FG, Gebremariam LW, Beyene SA. Food taboos and related misperceptions during pregnancy in Mekelle city, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2020; 15(10): e0239451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ekwochi U, Osuorah CDI, Ndu IK, et al. Food taboos and myths in South Eastern Nigeria: the belief and practice of mothers in the region. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 2016; 12(1): 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oni OA, Tukur J. Identifying pregnant women who would adhere to food taboos in a rural community: a community-based study. Afr J Reprod Health 2012; 16(3): 68–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kheiri SA, Kunna A, Mustafa IS, et al. Superstitious food beliefs and traditional customs among ladies attending the antenatal clinic at Omdurman Maternity Hospital (OMH), Omdurman, Sudan. Ann Med Heal Sci Res 2017; 7: 218–221. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chakona G, Shackleton C. Food taboos and cultural beliefs influence food choice and dietary preferences among pregnant women in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Nutrients 2019; 11(2668): 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yoseph HH. Prevalence of food aversions, cravings and pica during pregnancy and their association with nutritional status of pregnant women in Dale Woreda, Sidama zone, SNNPRS, Ethiopia. Int J Nutr Metab 2015; 7(1): 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gadegbeku C, Wayo R, Badu GA, et al. Food taboos among residents at Ashongman -Accra, Ghana, 2019, pp. 20–30, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332902536_Food_taboos_among_residents_at_Ashongman_-Accra_Ghana#:~:text=The%20study%20sample%20belonged%20to,43%25%20were%20of%20plant%20origin.

- 35. Ramulondi M, de Wet H, Ntuli NR. Traditional food taboos and practices during pregnancy, postpartum recovery, and infant care of Zulu women in northern KwaZulu-Natal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 2021; 17: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mukhopadhyay S, Sarkar A. Pregnancy-related food habits among women of rural Sikkim, India. Public Health Nutr 2009; 12(12): 2317–2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Odebiyi AI. Food taboos in maternal and child health: the views of traditional healers in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Soc Sci Med 1989; 28(9): 985–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Banu KK, Prathipa A, Anandarajan B, et al. Food taboos during antenatal and postpartum period among the women of rural and urban areas of Tamilnadu. Int J Biomed Adv Res 2016; 7(8): 393–396. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-smo-10.1177_20503121221133935 for Food taboos among pregnant women and associated factors in eastern Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study by Wbalem Amare, Abera Kenay Tura, Agumasie Semahegn and Kedir Teji Roba in SAGE Open Medicine