Abstract

Background

Tiotropium, a long-acting muscarinic antagonist, is recommended for add-on therapy to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)-long-acting beta 2 agonists (LABA) for severe asthma. However, real-world studies on the predictors of response to tiotropium are limited. We investigated the real-world use of tiotropium in asthmatic adult patients in Korea and we identified predictors of positive response to tiotropium add-on.

Methods

We performed a multicenter, retrospective, cohort study using data from the Cohort for Reality and Evolution of Adult Asthma in Korea (COREA). We enrolled asthmatic participants who took ICS-LABA with at least 2 consecutive lung function tests at 3-month intervals. We compared tiotropium users and non-users, as well as tiotropium responders and non-responders to predict positive responses to tiotropium, defined as 1) increase in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) ≥ 10% or 100 mL; and 2) increase in asthma control test (ACT) score ≥3 after 3 months of treatment.

Results

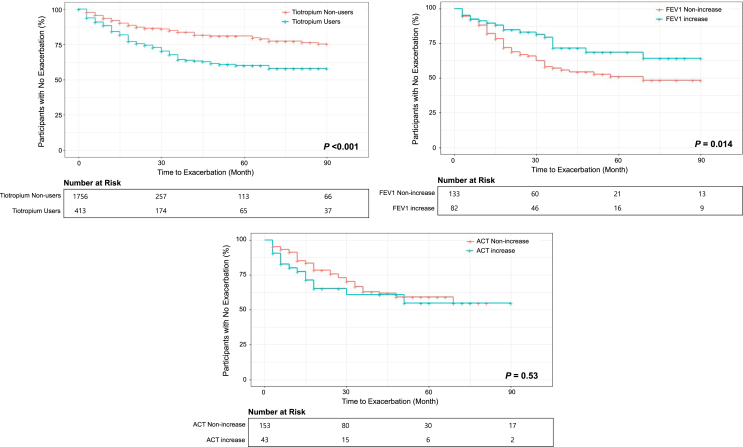

The study included 413 tiotropium users and 1756 tiotropium non-users. Tiotropium users had low baseline lung function and high exacerbation rate, suggesting more severe asthma. Clinical predictors for positive response to tiotropium add-on were 1) positive bronchodilator response (BDR) [odds ratio (OR) = 6.8, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.6–47.4, P = 0.021] for FEV1 responders; 2) doctor-diagnosed asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap (ACO) [OR = 12.6, 95% CI: 1.8–161.5, P = 0.024], and 3) initial ACT score <20 [OR = 24.1, 95% CI: 5.45–158.8, P < 0.001] for ACT responders. FEV1 responders also showed a longer exacerbation-free period than those with no FEV1 increase (P = 0.014), yielding a hazard ratio for the first asthma exacerbation of 0.5 (95% CI: 0.3–0.9, P = 0.016).

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that tiotropium add-on for uncontrolled asthma with ICS-LABA would be more effective in patients with positive BDR or ACO. Additionally, an increase in FEV1 following tiotropium may predict a lower risk of asthma exacerbation.

Keywords: Tiotropium, Muscarinic antagonists, Asthma, Treatment response, Predictor

Introduction

The 2021 update of the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) strategy recommends long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) for patients at Steps 4–5, including not only tiotropium, but also glycopyrronium and umeclidinium in forms of inhaled glucocorticoid (ICS)-long-acting beta 2 agonist (LABA)-LAMA triple combination.1,2 GINA defines severe asthma as uncontrolled symptomatic asthma despite high-dose ICS-LABA, or controlled only with high-dose ICS-LABA, and this condition may require additional therapy for proper symptom management.2 In those cases, the “add-on” therapy includes LAMAs, biologics, such as anti-immunoglobulin E (anti-IgE), anti-interleukin 5 and its receptor (anti-IL5/5R), and anti-IL4Rα, low-dose azithromycin, and oral corticosteroid (OCS) ≤7.5 mg/day prednisone equivalent.2

In clinical practice, physicians often consider LAMA primarily for add-on therapy, due to their familiar inhaler formulation, relatively low cost, and few side effects.3,4 Before 2021, tiotropium was the only LAMA approved for asthma, so it is currently the most commonly used.2 The GINA mentions that LAMA add-on therapy may lead to modest improvement in lung function and decreased exacerbation requiring OCS use, even if symptom relief is minimal.2 However, GINA does not define which patients would benefit most from LAMA add-on therapy;2 consequently, physicians do not have reliable information about which Steps 4–5 patients should be given LAMA preferentially.

Previous studies have mainly focused on elucidating the efficacy of tiotropium for asthma, but not the details of clinical and laboratory characteristics of tiotropium responders.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Add-on therapy is important for poorly controlled asthma or severe asthma, which have higher exacerbation risk, OCS requirements, impaired lung function, and poorer quality of life.2,15 Although biologics show high efficacy, they are very expensive, which presents a barrier to access for some patients. Therefore, it is still necessary to identify the asthmatic patients who exhibit good responses to LAMA.3 Thus, we investigated clinical characteristics, lung function, symptom score, and exacerbation rate of tiotropium users and non-users, as well as tiotropium responders and non-responders and its predictors in adult asthma using multicenter real-world cohort data from Korea.

Materials and methods

Study population

The Cohort for Reality and Evolution of Adult Asthma in Korea (COREA) is a multicenter nationwide asthma cohort in Korea started in 2005.16 Allergy or pulmonology specialists recruited adult asthmatic patients from 39 tertiary referral centers (≥18 years old).16 We defined asthma as: 1) the presence of one or more symptoms including dyspnea, cough, or wheezing, and 2) proven airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) or airway reversibility. AHR was defined as positive when PC20 (provocative concentration causing a 20% fall in forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1]) was less than 25 mg/mL in a bronchial provocation test using methacholine chloride. Airway reversibility was defined as an increase in FEV1 ≥12% from baseline after inhalation of 400 μg of salbutamol or 4 weeks of anti-inflammatory treatment (systemic and inhaled steroids). The results of AHR and airway reversibility were obtained by reviewing electronic medical records, and asthma patients of all GINA steps could be enrolled.

The physicians performed standard asthma treatments according to the GINA strategy at that time, and they followed patients with history taking, physical examination, spirometry, and medication adjustment every three months. Currently COREA includes more than 5000 asthmatic patients registered with detailed demographics and clinical and laboratory data.

From the COREA database, we enrolled participants who took ICS-LABA and had at least 2 consecutive lung function tests at 3-month intervals, and we excluded those who received any LAMA other than tiotropium (aclidinium, glycopyrronium, and umeclidinium). A total of 2169 participants were enrolled, of which 413 were ICS-LABA-tiotropium users and 1756 were tiotropium non-users. We studied the clinical characteristics of tiotropium users and non-users, and the differences between tiotropium responders and non-responders. We also evaluated possible predictors of tiotropium response.

Variable definitions

Asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) overlap (ACO) was defined as post-bronchodilator airway flow limitation (FEV1/forced vital capacity [FVC] < 0.7) and smoking history ≥10 pack-years. We also investigated doctor-diagnosed ACO. Atopy was determined as positive for inhalant allergens by skin prick test or multiple allergen simultaneous test. Other controller medications other than tiotropium were beclomethasone, budesonide, triamcinolone, ciclesonide, fluticasone, or flunisolide for ICS; methylprednisolone, prednisolone, hydrocortisone, dexamethasone, or deflazacort for OCS; and salmeterol or formoterol for LABA. Steroid burst was defined as >30 mg/day of prednisolone or its equivalent for more than 3 days, and this was evaluated at their regular clinic visit every 3 months or at unexpected visits due to exacerbation. Blood eosinophil, total IgE, and C-reactive protein levels were obtained at enrollment. We defined tiotropium responders in three ways: 1) increase in FEV1 ≥10% or 100 mL, 2) increase in asthma control test (ACT) score ≥3, or 3) no exacerbation 3 months after starting tiotropium.

Statistical analyses

General characteristics among the study population were assessed using Student's t-test for continuous variables and Pearson's χ2 test for categorical variables. Binary logistic regression (univariate and multivariate analysis) was performed to determine the predictive factors for positive response to tiotropium add-on among asthmatic patients. Time analysis of the first severe asthma exacerbation was conducted using the Kaplan-Meier method. The strength of associations is presented as odds ratios (OR) or hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistically significant difference was defined as a P-value <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

General characteristics

A total of 2169 asthmatic patients were enrolled, and the general characteristics of tiotropium users (n = 413) and tiotropium non-users (n = 1756) are presented in Table 1. Tiotropium users had significantly older age (59.2 ± 13.5 vs. 49.6 ± 16.0, P < 0.001) and more males (62.7% vs. 43.2%, P < 0.001) than non-users, and also had a higher rate of late-onset asthma (72.3% vs. 58.4%, P < 0.001), longer asthma duration (8.3 ± 9.3 years vs. 5.4 ± 7.5 years, P < 0.001), more ever-smokers (67.3% vs. 46.1%, P < 0.001) and higher ACO prevalence (59.8% vs. 21.3%, P < 0.001). The group using tiotropium showed fewer atopic patterns (16.0% vs. 35.3%, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Characteristics | Non-Tiotropium users (n = 1756) | Tiotropium users (n = 413) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 758 (43.2) | 259 (62.7) | <.001 |

| Age (years) | 49.6 ± 16.0 | 59.2 ± 13.5 | <.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 9.9 | 24.3 ± 3.7 | 0.054 |

| Onset of asthma (years) | 42.6 ± 17.2 | 47.9 ± 16.9 | <.001 |

| Late-onset asthma (age of onset ≥40 years), n (%) | 1014 (58.4) | 289 (72.3) | <.001 |

| Duration of asthma (years) | 5.4 ± 7.5 | 8.3 ± 9.3 | <.001 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Nonsmoker | 935 (54.0) | 132 (32.7) | |

| Past smoker | 518 (29.9) | 196 (48.5) | |

| Current smoker | 280 (16.2) | 76 (18.8) | |

| Smoking history (pack-year) | 17.7 ± 18.2 | 27.4 ± 23.3 | <.001 |

| ACO (doctor-diagnosed), n (%) | 115 (6.6) | 132 (32.0) | <.001 |

| ACO (by ATS definition), n (%) | 93 (21.3) | 101 (59.8) | <.001 |

| Other allergic diseases, n (%) | |||

| Atopy | 619 (35.3) | 66 (16.0) | <.001 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 809 (99.9) | 144 (98.0) | 0.013 |

| NERD | 17 (1.0) | 4 (1.0) | 1.0 |

| Family history of allergic disease, n (%) | 309 (17.6) | 76 (18.4) | 0.754 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| WBC (/μL) | 7764.7 ± 2829.1 | 8265.9 ± 2606.5 | 0.005 |

| Eosinophil (%) | 5.00 ± 5.4 | 4.8 ± 4.8 | 0.584 |

| Eosinophil (/μL) | 354.1 ± 394.3 | 385.9 ± 477.4 | 0.285 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 0.8 ± 2.3 | 0.8 ± 1.7 | 0.805 |

| Serum total IgE (IU/mL) | 410.0 ± 581.6 | 461.8 ± 882.9 | 0.536 |

| Lung function | |||

| FEV1% predicted | 81.9 ± 18.7 | 63.2 ± 19.6 | <.001 |

| FVC % predicted | 88.8 ± 16.4 | 78.9 ± 17.3 | <.001 |

| FEV1/FVC % postbronchodilation | 73.0 ± 11.3 | 59.6 ± 13.3 | <.001 |

| Positive bronchodilator response (n, %) | 224 (22.4) | 60 (23.0) | 0.911 |

| Budesonide equivalent ICS dose (mcg/day) | 533.7 ± 410.4 | 641.8 ± 520.8 | 0.009 |

| Prednisolone equivalent OCS dose during last month (mg) | 24.8 ± 71.9 | 47.1 ± 108.8 | 0.007 |

| Annual exacerbation rate (/year) | 0.7 ± 2.0 | 1.0 ± 2.5 | 0.023 |

| SCS burst use, n (%) | 105 (6.0) | 33 (8.0) | 0.163 |

| ER visit (/year) | 0.4 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 2.2 | 0.151 |

| Hospitalization (/year) | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | <.001 |

| ACT scores (total 25) | 20.7 ± 4.1 | 19.4 ± 4.6 | <.001 |

Data are presented as number (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

BMI, body mass index; ACO, Asthma-COPD Overlap; ATS, American Thoracic Society; NERD, NSAID exacerbated respiratory disease; WBC, white blood cell; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; OCS, oral corticosteroids; SCS, systemic corticosteroids; ER, emergency room; ACT, Asthma Control Test.

Tiotropium users showed significantly lower FEV1 (63.2 ± 19.6% vs. 81.9 ± 18.7%, P < 0.001) and FEV1/FVC (59.6 ± 13.3% vs. 73.0 ± 11.3%, P < 0.001), and there was no significant difference in positive bronchodilator response (BDR) between the two groups (23.0% vs. 22.4%). In tiotropium users, budesonide equivalent ICS dose (641.8 ± 520.8 mcg/day vs. 533.7 ± 410.4 mcg/day, P = 0.009) and prednisolone equivalent OCS dose for the past one month (47.1 ± 108.8 mg vs. 24.8 ± 71.9 mg, P = 0.007) were significantly higher, and the annual exacerbation rate was also higher (1.0 ± 2.5 vs. 0.7 ± 2.0, P = 0.023). ACT was significantly lower in tiotropium users (19.4 ± 4.6 vs. 20.7 ± 4.1, P < 0.001).

Changes in lung function in tiotropium users and non-users after 3 months of treatment

FEV1 (mL and %), FEV1/FVC ratio, and ACT score were examined for tiotropium users and non-users. When comparing FEV1 before the start of tiotropium (or at the time of registration for tiotropium non-users) and 3 months after, the change in FEV1 was 46.3 ± 381.7 mL and 89.8 ± 420.4 mL in tiotropium users and non-users, respectively, which showed no significant difference. ΔFEV1 (%), ΔFEV1/FVC, and ΔACT were also not significantly different between the 2 groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

The changes in lung function and ACT in tiotropium users and non-users after 3 months of treatment

| Tiotropium |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-users | Users | ||

| ΔFEV1 (mL) | 89.8 ± 420.4 (n = 336) | 46.3 ± 381.7 (n = 215) | 0.22 |

| ΔFEV1 (%) | 3.7 ± 12.1 (n = 336) | 2.0 ± 12.1 (n = 214) | 0.12 |

| ΔFEV1/FVC | 0.0 ± 0.1 (n = 336) | 0.2 ± 3.1 (n = 214) | 0.34 |

| ΔACT | 0.9 ± 3.9 (n = 490) | 0.3 ± 4.6 (n = 196) | 0.09 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; ACT, Asthma Control Test.

Differences according to tiotropium treatment response

First, when comparing the group in which FEV1 increased by ≥ 10% or 100 mL after 3 months of tiotropium administration (N = 133) and those with no FEV1 increase (N = 82), ΔFEV1 was 360.7 ± 311.1 mL in responders and −147.5 ± 278.6 mL in non-responders (P < 0.001). The responder group also showed younger age (56.7 ± 13.8 years vs. 60.7 ± 12.5 years, P = 0.029), and higher rate of positive BDR than non-responders (38.1% vs. 6.5%, P < 0.001; Table 3a). Next, the group in which ACT score increased by ≥ 3 points showed significantly lower ACT score than the non-responder group (15.0 ± 4.1 vs. 21.6 ± 3.4, P < 0.001; Table 3b). Lastly, when comparing the group without exacerbation (responders) and the group with one or more exacerbations within 3 months after starting tiotropium, responders showed higher blood eosinophil percentage (4.9 ± 4.8% vs. 1.6 ± 1.6%, P = 0.028) and count (387.7 ± 375.0/μL vs. 130.8 ± 103.6/μL, P = 0.041) than non-responders (Table 3c).

Table 3a.

Characteristics of the study population according to the response of tiotropium determined by an increase in FEV1 after 3 month after starting tiotropium

| Characteristics | FEV1 < 10% or 100 mL (n = 133) | FEV1 increase ≥10% or 100 mL (n = 82) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔFEV1 (mL) | −147.52 ± 278.57 | 360.73 ± 311.1 | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 85 (63.9) | 56 (68.3) | 0.611 |

| Age (years) | 60.7 ± 12.5 | 56.7 ± 13.8 | 0.029 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.7 ± 3.4 | 25.1 ± 4.3 | 0.076 |

| Onset of asthma (years) | 51.4 ± 15.4 | 45.0 ± 17.7 | 0.063 |

| Late-onset asthma (age of onset ≥ 40 years), n (%) | 41 (78.9) | 29 (65.9) | 0.234 |

| Duration of asthma(years) | 8.4 ± 8.5 | 7.7 ± 8.7 | 0.693 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.353 | ||

| Nonsmoker | 16 (27.1) | 15 (30.6) | |

| Past smoker | 35 (59.3) | 23 (46.9) | |

| Current Smoker | 8 (13.6) | 11 (22.5) | |

| Smoking history (pack-year) | 31.3 ± 20.6 | 33.0 ± 34.7 | 0.807 |

| ACO (doctor-diagnosed), n (%) | 21 (15.8) | 14 (17.1) | 0.954 |

| ACO (by ATS definition), n (%) | 16 (72.7) | 16 (72.7) | 1.0 |

| Other allergic diseases, n (%) | |||

| Atopy | 4 (3.1) | 3 (3.7) | 1.0 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 16 (94.1) | 16 (100.0) | 1.0 |

| Family history of allergic disease (n, %) | 9 (6.8) | 10 (12.2) | 0.265 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| WBC (/μL) | 8278.3 ± 2194.9 | 9164.4 ± 2763.9 | 0.129 |

| Eosinophil (%) | 4.5 ± 5.2 | 4.9 ± 4.2 | 0.739 |

| Eosinophil (/μL) | 337.5 ± 358.8 | 404.5 ± 355.3 | 0.424 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 0.9 ± 1.6 | 0.9 ± 1.2 | 0.634 |

| Serum total IgE (IU/mL) | 351.0 ± 404.3 | 257.4 ± 287.2 | 0.752 |

| Lung function | |||

| FEV1% predicted | 65.9 ± 18.5 | 62.7 ± 17.0 | 0.201 |

| FVC % predicted | 80.6 ± 16.7 | 76.4 ± 19.8 | 0.096 |

| FEV1/FVC % postbronchodilation | 58.8 ± 13.6 | 62.0 ± 14.2 | 0.283 |

| Positive bronchodilator response (n, %) | 3 (6.5) | 16 (38.1) | <0.001 |

| Budesonide equivalent ICS dose (mcg/day) | 700.4 ± 599.2 | 581.3 ± 391.8 | 0.280 |

| Prednisolone equivalent OCS dose during last month (mg) | 47.1 ± 124.9 | 114.6 ± 158.2 | 0.11 |

| Annual exacerbation rate (/year) | 3.0 ± 3.7 | 2.2 ± 2.5 | 0.559 |

| SCS burst use, n (%) | 13 (9.8) | 5 (6.1) | 0.489 |

| ER visit (/year) | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.842 |

| Hospitalization (/year) | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 0.5 ± 0.6 | 0.989 |

| ACT scores (total 25) | 20.6 ± 4.0 | 19.4 ± 5.3 | 0.131 |

Data are presented as number (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

BMI, body mass index; ACO, Asthma-COPD Overlap; ATS, American Thoracic Society; WBC, white blood cell; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; OCS, oral corticosteroids; SCS, systemic corticosteroids; ER, emergency room; ACT, Asthma Control Test.

Table 3b.

Characteristics of the study population according to the response of tiotropium determined by an increase in ACT score after 3 month after starting tiotropium

| Characteristics | ACT <3 (n = 153) | ACT increase ≥3 (n = 43) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔACT scores | −1.38 ± 3.35 | 6.26 ± 3.34 | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 97 (63.4) | 23 (53.5) | 0.317 |

| Age (years) | 59.3 ± 12.1 | 59.3 ± 12.9 | 0.988 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.9 ± 4.0 | 25.5 ± 3.6 | 0.052 |

| Onset of asthma (years) | 49.4 ± 17.0 | 53.7 ± 17.5 | 0.531 |

| Late-onset asthma (age of onset ≥ 40 years), n (%) | 32 (74.4) | 17 (89.5) | 0.31 |

| Duration of asthma(years) | 9.7 ± 11.6 | 4.3 ± 5.1 | 0.16 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.595 | ||

| Nonsmoker | 13 (24.5) | 8 (36.4) | |

| Past smoker | 32 (60.4) | 11 (50.0) | |

| Current Smoker | 8 (15.1) | 3 (13.6) | |

| Smoking history (pack-year) | 27.6 ± 24.6 | 28.1 ± 22.9 | 0.835 |

| ACO (doctor-diagnosed), n (%) | 14 (9.2) | 9 (20.9) | 0.064 |

| ACO (by ATS definition), n (%) | 18 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) | 0.643 |

| Other allergic diseases, n (%) | |||

| Atopy | 5 (3.8) | 2 (4.7) | 0.649 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 17 (94.4) | 6 (100.0) | 1.0 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| WBC (/μL) | 8402.3 ± 2409.4 | 8853.1 ± 2570.1 | 0.661 |

| Eosinophil (%) | 5.0 ± 4.6 | 5.4 ± 6.3 | 0.827 |

| Eosinophil (/μL) | 401.0 ± 380.8 | 440.1 ± 471.5 | 0.877 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 1.3 ± 2.1 | 1.1 ± 1.0 | 0.302 |

| Serum total IgE (IU/mL) | 326.6 ± 290.1 | 222.5 ± 281.8 | 0.727 |

| Lung function | |||

| FEV1% predicted | 66.5 ± 16.7 | 63.7 ± 17.2 | 0.373 |

| FVC % predicted | 81.2 ± 18.0 | 77.9 ± 15.4 | 0.304 |

| FEV1/FVC % postbronchodilation | 59.9 ± 14.3 | 65.3 ± 13.6 | 0.206 |

| Positive bronchodilator response (n, %) | 10 (19.6) | 5 (35.7) | 0.283 |

| Budesonide equivalent ICS dose (mcg/day) | 599.2 ± 501.0 | 774.8 ± 575.5 | 0.055 |

| Prednisolone equivalent OCS dose during last month (mg) | 54.9 ± 97.0 | 158.3 ± 220.1 | 0.173 |

| Annual exacerbation rate (/year) | 2.5 ± 3.7 | 2.6 ± 3.4 | 0.622 |

| SCS burst use, n (%) | 18 (11.8) | 6 (14.0) | 0.902 |

| ER visit (/year) | 1.0 ± 2.6 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.825 |

| Hospitalization (/year) | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.96 |

| ACT scores (total 25) | 21.6 ± 3.4 | 15.0 ± 4.1 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as number (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

BMI, body mass index; ACO, Asthma-COPD Overlap; ATS, American Thoracic Society; WBC, white blood cell; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; OCS, oral corticosteroids; SCS, systemic corticosteroids; ER, emergency room; ACT, Asthma Control Test.

Table 3c.

Characteristics of the study population according to the response of tiotropium determined by the presence of asthma exacerbation within 3 months after starting tiotropium

| Exacerbation ≥1 (n = 82) | No exacerbation (n = 133) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 10 (62.5) | 154 (63.1) | 1.000 |

| Age (years) | 56.1 ± 15.0 | 59.6 ± 12.8 | 0.463 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8 ± 1.9 | 24.3 ± 3.9 | 0.668 |

| Onset of asthma (years) | 44.6 ± 20.6 | 48.7 ± 16.9 | 0.662 |

| Late-onset asthma (age of onset ≥ 40 years), n (%) | 4 (57.1) | 76 (73.1) | 0.397 |

| Duration of asthma(years) | 8.4 ± 6.6 | 8.9 ± 10.0 | 0.478 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 8 (100.0) | 117 (100.0) | 0.098 |

| Nonsmoker | 0 (0) | 34 (29.1) | |

| Past smoker | 5 (62.5) | 63 (53.9) | |

| Current Smoker | 3 (37.5) | 20 (17.1) | |

| Smoking history (pack-year) | 27.3 ± 22.2 | 31.8 ± 27.3 | 0.729 |

| ACO (doctor-diagnosed), n (%) | 1 (6.25) | 41 (16.8) | 0.482 |

| ACO (by ATS definition), n (%) | 2 (66.7) | 35 (71.4) | 1.0 |

| Other allergic diseases, n (%) | |||

| Atopy | 0 (0) | 9 (3.7) | 1.0 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 2 (100.0) | 34 (97.1) | 1.0 |

| Family history of allergic disease (n, %) | 1 (6.3) | 18 (7.4) | 1.0 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| WBC (/μL) | 10,180 ± 2901.2 | 8479.9 ± 2427.0 | 0.144 |

| Eosinophil (%) | 1.6 ± 1.6 | 4.9 ± 4.8 | 0.028 |

| Eosinophil (/μL) | 130.8 ± 103.6 | 387.7 ± 375.0 | 0.041 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 0.6 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.7 | 0.949 |

| Serum total IgE (IU/mL) | 91.3 ± 91.6 | 324.2 ± 351.4 | 0.345 |

| Lung function | |||

| FEV1% predicted | 59.5 ± 15.3 | 64.6 ± 18.0 | 0.153 |

| FVC % predicted | 75.8 ± 12.2 | 79.2 ± 18.02 | 0.346 |

| FEV1/FVC % postbronchodilation | 61.0 ± 16.4 | 59.3 ± 14.2 | 0.961 |

| Positive bronchodilator response (n, %) | 1 (25.0) | 18 (19.2) | 1.0 |

| Budesonide equivalent ICS dose (mcg/day) | 400 ± 196.0 | 648.5 ± 521.0 | 0.429 |

| Prednisolone equivalent OCS dose during last month (mg) | 147.5 ± 250.5 | 63.4 ± 119.0 | 0.453 |

| Annual exacerbation rate (/year) | 2.7 ± 2.2 | 2.5 ± 3.4 | 0.38 |

| SCS burst use, n (%) | 2 (12.5) | 23 (9.4) | 0.657 |

| ER visit (/year) | 0.8 ± 1.0 | 0.9 ± 2.0 | 0.804 |

| Hospitalization (/year) | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0.9 | 0.38 |

| ACT scores (total 25) | 19.8 ± 3.9 | 20.2 ± 4.5 | 0.555 |

Data are presented as number (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

BMI, body mass index; ACO, Asthma-COPD Overlap; ATS, American Thoracic Society; WBC, white blood cell; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; OCS, oral corticosteroids; SCS, systemic corticosteroids; ER, emergency room; ACT, Asthma Control Test.

Predictors for tiotropium response

Next, we investigated the presence of predictors for treatment response to tiotropium. Positive BDR showed significant association with an increase in FEV1 ≥ 10% or 100 mL (OR = 6.8, 95% CI: 1.6–47.4, P = 0.021; Table 4a). In an unadjusted model, BMI >25 kg/m2, initial ACT score <20, and doctor-diagnosed ACO were associated with an increase in ACT score ≥3 points, but only doctor-diagnosed ACO and initial ACT score <20 remained significant after adjustment (OR = 12.6, 95% CI: 1.8–161.5, P = 0.024; OR = 24.1, 95% CI: 5.45–158.8, P < 0.001; Table 4b). There was no significant OR value for the no exacerbation group (data not shown).

Table 4a.

Predictors of a positive FEV1 response to tiotropium add-on therapy in adult asthmatic patient

| Variables | Tiotropium responder (FEV1≥ 10% or 100 mL) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted |

Adjusteda |

|||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 0.111 | |||

| < 65 years | 1 | |||

| ≥65 years | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | |||

| Sex | 0.511 | |||

| Male | 1 | |||

| Female | 0.8 (0.5–1.5) | |||

| BMI >25 kg/m2 | 2.2 (1.0–4.8) | 0.055 | ||

| ACO, doctor-diagnosed | 1.1 (0.5–2.3) | 0.804 | ||

| Smoking status | 0.69 | |||

| Never smoker | 1 | |||

| Ever smoker | 0.8 (0.4–2.0) | |||

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| Blood Eosinophil ≥150/μL | 1.7 (0.6–4.6) | 0.314 | ||

| Serum total IgE ≥76 IU/mL | 0.8 (0.2–4.6) | 0.831 | ||

| Atopyb | 1.2 (0.2–5.7) | 0.794 | ||

| Initial FEV1% predicted <80% | 1.7 (0.8–3.9) | 0.154 | ||

| FEV1/FVC% postbronchodilator <70% | 0.6 (0.2–1.4) | 0.229 | ||

| Positive bronchodilator response (n, %) | 8.8 (2.6–40.6) | 0.001 | 6.8 (1.6–47.4) | 0.021 |

| Budesonide equivalent ICS dose >800 mcg/day | 0.6 (0.2–1.6) | 0.322 | ||

| Initial ACT score <20 | 1.9 (0.9–3.7) | 0.075 | ||

BMI, body mass index; ACO, Asthma-COPD Overlap; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; ACT, Asthma Control Test; OR, odds ratio; CI; confidence interval.

Adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, and positive bronchodilator response.

defined as positive for inhalant allergens by skin prick test or multiple allergen simultaneous test (MAST).

Table 4b.

Predictors of a positive ACT response to tiotropium-add on therapy in adult asthmatic patient

| Variables | Tiotropium responder (ACT ≥3) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted |

Adjusteda |

|||

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | ||||

| < 65 years | 1 | |||

| ≥65 years | 0.9 (0.5–1.9) | 0.861 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1 | |||

| Female | 1.5 (0.8–3.0) | 0.24 | ||

| BMI >25 kg/m2 | 3.9 (1.4–11.7) | 0.01 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.203 |

| ACO, doctor-diagnosed | 2.6 (1.0–6.5) | 0.039 | 12.6 (1.8–161.5) | 0.024 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoker | 1 | |||

| Ever smoker | 0.6 (0.2–1.7) | 0.302 | ||

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| Blood Eosinophil ≥150/μL | 0.8 (0.2–2.8) | 0.66 | ||

| Serum total IgE ≥76 IU/mL | 0.1 (0–2.2) | 0.184 | ||

| Atopyb | 1.4 (0.2–7.0) | 0.667 | ||

| Initial FEV1% predicted <80% | 0.9 (0.4–2.2) | 0.713 | ||

| FEV1/FVC% postbronchodilator <70% | 0.7 (0.2–2.2) | 0.497 | ||

| Budesonide equivalent ICS dose >800 mcg/day | 1.6 (0.6–4.2) | 0.33 | ||

| Initial ACT score <20 | 14.73 (6.72–34.88) | <0.001 | 24.13 (5.45–158.8) | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index; ACO, Asthma-COPD Overlap; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; ACT, Asthma Control Test; OR, odds ratio; CI; confidence interval.

Adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, initial ACT score and doctor-diagnosed ACO.

Defined as positive for inhalant allergens by skin prick test or multiple allergen simultaneous test (MAST).

Exacerbation-free period among tiotropium users and non-users

We also examined the time to first asthma exacerbation (TFE) in each group using the Kaplan-Meier curve. Tiotropium users showed a shorter time to first acute exacerbation than tiotropium non-users (P < 0.001; Fig. 1). However, among tiotropium users, the group with increased FEV1 exhibited a longer exacerbation-free period than those with no FEV1 increase (P = 0.014), yielding a HR = 0.5 for TEF (95% CI: 0.3–0.9, P = 0.016; Fig. 1–2). There was no significant difference in TFE between the group with an ACT increase and the group with no ACT increase (P = 0.53), showing the HR = 1.2 for TEF (95% CI: 0.7–2.1, P = 0.529; Fig. 1–3).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier Curves for the Time to the First Severe Asthma Exacerbation, According to Each Group. 1–1. Tiotropium Non-Users (only ICS-LABA) vs Users (ICS-LABA-Tiotropium) 1–2. FEV1 Non-Increase Group vs Increase Group (among tiotropium users) 1–3. ACT Non-increase Group vs Increase Group (among tiotropium users) Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; ACT, Asthma Control Test.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the real-world use of tiotropium add-on in adult asthma, and we found that tiotropium was added to severe or uncontrolled asthma, with lower FEV1 and FEV1/FVC, poor symptom scores, more ICS or OCS use, and frequent exacerbations in a real-world situation in Korea. The results showed that tiotropium users exhibited any significant difference in ΔFEV1, ΔFEV1/FVC, or ΔACT scores compared with non-users, however, tiotropium users with increased FEV1 showed marked improvement of FEV1 >300 mL, suggesting that this group certainly benefitted from tiotropium use. It would be helpful to identify this responder group before tiotropium administration. In our study, positive BDR and doctor-diagnosed ACO were significant predictors for FEV1 response and ACT response to tiotropium, respectively. Initial ACT score less than 20 also associated with increased OR for ACT response to tiotropium. Additionally, FEV1 responders showed significantly longer time to first asthma exacerbation. Thus, asthmatic patients with positive BDR are more likely to have an increase in FEV1 by tiotropium add-on, and if there is an increase in FEV1, it may be effective in preventing asthma exacerbation.

Tiotropium is one of the muscarinic antagonists that binds M3 receptors widely expressed throughout airways, resulting in attenuation of bronchoconstriction caused by acetylcholine released from the vagal nerve.17,18 Until now, muscarinic antagonists have mostly been used for COPD, not asthma, because direct bronchoconstriction by inflammatory substances such as leukotrienes was considered as more important pathophysiology in asthma rather than bronchoconstriction by increasing vagal tone.15,19

The first publication of the “Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention” report was in 1995. In the 2002 version, the report elucidated the importance of anti-inflammatory treatment in asthma. In 2006, the report highlighted the need for evaluation and stepwise treatment by symptomatic asthma control status.20,21 The 2010 report, which introduced the use of anti-IgE omalizumab for management of severe uncontrolled asthma, limited the role of anticholinergics to the use of short-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists (SAMAs) ipratropium bromide and oxitropium bromide for additional bronchodilation in cases of acute asthma exacerbation.22 In a major revision in 2014 and then again in 2015, tiotropium add-on therapy was adopted as another controller option for GINA Step 4 or 5 for adult asthma with a history of exacerbations, following approval of tiotropium for this indication.21

Recently, more LAMAs other than tiotropium were introduced for add-on therapy based on several clinical trials.2,8,11,13,23,24 The 2021 GINA strategy suggests tiotropium for patients ≥6 years, or a triple combination such as beclomethasone-formoterol-glycopyrronium, fluticasone furoate-vilanterol-umeclidinium, or mometasone-indacaterol-glycopyrronium for patients ≥18 years for management of GINA Step 4 or 5. The European Respiratory Society (ERS)/American Thoracic Society (ATS) Severe Asthma Task Force recommends adding tiotropium to ICS-LABA for patients with severe uncontrolled asthma.12 Currently, these guidelines recommend that tiotropium add-on to ICS-LABA or triple combination could be considered regardless of asthma phenotype or endotype.

Among LAMAs, tiotropium has been used most widely and for a long time.25 Tiotropium Respimat® is approved in asthmatic patients aged 6 years and older in Korea, the United States, and the European Union.25,26 Several studies have elucidated the efficacy of tiotropium in asthma. A double-blind, three-way, crossover trial, called the Tiotropium Bromide as an Alternative to Increased Inhaled Glucocorticoid in Patients Inadequately Controlled on a Lower Dose of Inhaled Corticosteroid (TALC) study, revealed that adding tiotropium is superior to increasing ICS dose in patients whose asthma symptoms are not controlled by inhaled beclomethasone alone at a dose of 160 μg/day, and non-inferior to adding salmeterol with respect to morning and evening peak expiratory flow (PEF) and asthma symptom score.5

In a study on predictors of response to tiotropium, a short-acting bronchodilator response to albuterol was a predictor for a positive response to tiotropium for FEV1, and increased cholinergic tone determined by lower resting heart rate was also a predictor, while ethnicity, gender, asthma duration, atopy, IgE level, sputum eosinophil count, FENO, and BMI were not.5,27 Although the TALC study compared tiotropium with increasing ICS or adding salmeterol, and our study focused on tiotropium add-on to ICS-LABA, both studies showed consistent results that positive BDR predicts a positive response from tiotropium for increasing FEV1. Another study with severe asthmatic adults found that tiotropium was effective in improving lung function, increasing time to first severe exacerbation, and relieving asthma symptoms, regardless of baseline demographics such as IgE level, eosinophil count, age, and gender.6 However, in our study, not all tiotropium users showed favorable responses. According to another exploratory analysis from 4 large asthma trials, several factors such as age, sex, smoking status, age of onset, BMI, duration of asthma, FEV1, T2 high or T2 low profiles, IgE level, and eosinophil count did not predict tiotropium efficacy in moderate-to-severe asthmatic adults.7,9 Based on the inconsistent results from these studies, the current GINA guideline seems to recommend that phenotyping before tiotropium is unnecessary.

However, unlike well-organized, large scale randomized controlled trials, real-world clinical practice includes a wide spectrum of patients, which indicates a need for a real-world study.28 In a previous real-world retrospective cohort study for tiotropium response from Taiwan, tiotropium add-on improved asthma symptom control independent of age, sex, smoking status, ACO, initial FEV1, blood eosinophil, and BMI, while IgE >430 μg/L was identified as the only predictor of low clinical response to tiotropium.29 Another study with 138 severe asthmatics reported significantly higher rate of atopy, which is defined as positive skin prick tests to aeroallergens, in tiotropium responder than non-responders.30 These results are inconsistent with our finding that doctor-diagnosed ACO was a predictor for ACT responders and no relationship was observed with IgE level. Overall, the patients who could benefit from tiotropium add-on have not been clearly identified yet, showing inconsistent results among studies and lack of real-world investigation. In respect to ACO, there is a recent investigation on the effect of LAMA in patients with ACO. This 48-week, randomized, noninferiority trial comparing ICS-LABA vs ICS-LABA-LAMA in 303 ACO patients showed ICS-LABA-LAMA treatment had no difference in regard to TFE but significantly improved FEV1 and FVC compared with ICS-LABA, and this may also be evidence in favor of the effectiveness of LAMA on ACO.31 Regarding TFE, our study results showed that FEV1 responders among tiotropium users in asthma showed a significantly longer TFE than non-responders, which suggests that physicians managing asthma need to consider to add tiotropium more actively in step 4–5 treatment.

In this study, we investigated the real-world use of tiotropium in adult asthmatic patients in Korea and the presence of predictors for positive response to tiotropium add-on. However, this study has some limitations. First, we did not consider the effect of other asthma medications such as leukotriene receptor antagonist, xanthine derivatives, and azithromycin. Additionally, we enrolled all ICS-LABA users regardless of ICS dose. Second, we included current smokers in the analysis, which may have affected the results. Even so, this may reflect the real-world situation. Next, due to limitations in study design that individual physicians followed while practicing, tiotropium dose was not controlled and adherence to tiotropium or other medications was not assessed. We also could not analyze whether the OCS dose reduced or discontinued after administration of tiotropium, and the seasonal effects regarding exacerbation could not be sufficiently studied because no exacerbation after 3 months was defined as the responder. Finally, we could not evaluate sufficient laboratory T2 markers, so additional research into inflammatory or biomarkers is needed.

In conclusion, this study found that tiotropium add-on therapy might be considered for symptomatic uncontrolled asthma despite ICS-LABA use, especially for cases with positive BDR or ACO. Patients with poor ACT scores are more likely to improve their ACT after administration of tiotropium. Furthermore, an increase in FEV1 in tiotropium users could lead to a delay in asthma exacerbation. Currently, LAMA is being used as a non-selective asthma treatment, but more research on responders who show better outcomes to LAMA is needed and through this, the role of LAMA as a personalized treatment can be reconsidered.

Abbreviations

ACT; asthma control test, ACO; asthma-COPD overlap, BDR; bronchodilator response, COPD; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, FEV1; forced expiratory volume in 1 s, GINA; Global Initiative for Asthma, ICS; inhaled corticosteroids, IgE; immunoglobulin E, LABA; long-acting β2-agonist, LAMA; long-acting muscarinic antagonist, LTRA; leukotriene receptor antagonist, OCS; oral corticosteroids

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI19C0481, HC20C0076). This work was also supported by the Ewha Womans University Research Grant of 2021.

Availability of data and materials

The data-sets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

JS, JJ, MH, and TK designed the study; SK, TL, AJ, CP, JJ, JK, JM, MY, JL, JC, YS, HK, SK, JK, SC, YN, SK, SP, GH, SK, HP, HJ, JL, JP, HY, BC, YC, MK, and TK collected the data; JS and JJ analyzed the data; JS, JJ, MH, and TK interpreted the data; JS drafted the manuscript; MH and TK revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content; all authors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ewha Womans University Medical Center (SEUMC 2020-08-022-006). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Authors’ consent for publication

All authors agreed to the publication of this work in the World Allergy Organization Journal.

Submission declaration

The authors confirm that this manuscript is original, has not been published before, is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere, and has not been posted to a preprint server.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

We thank all the members participating in COREA research group for their support and discussion of the study.

Footnotes

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Contributor Information

Min-Hye Kim, Email: mineyang81@ewha.ac.kr.

Tae-Bum Kim, Email: tbkim@amc.seoul.kr.

References

- 1.Kim B.K., Park S.Y., Ban G.Y., et al. Evaluation and management of difficult-to-treat and severe asthma: an expert opinion from the Korean academy of asthma, Allergy and clinical immunology, the working group on severe asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2020;12:910–933. doi: 10.4168/aair.2020.12.6.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2021. https://ginasthma.org

- 3.Buendia J.A., Guerrero Patiño D., Cossio-Giraldo Y.E. Cost-effectiveness of tiotropium versus omalizumab for uncontrolled allergic asthma. J Asthma. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2021.1984527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong S.H., Cho J.Y., Kim T.B., Lee E.K., Kwon S.H., Shin J.Y. Cost-effectiveness of tiotropium in elderly patients with severe asthma using real-world data. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1939–1947. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.052. e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters S.P., Kunselman S.J., Icitovic N., et al. Tiotropium bromide step-up therapy for adults with uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1715–1726. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerstjens H.A., Moroni-Zentgraf P., Tashkin D.P., et al. Tiotropium improves lung function, exacerbation rate, and asthma control, independent of baseline characteristics including age, degree of airway obstruction, and allergic status. Respir Med. 2016;117:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casale T.B., Bateman E.D., Vandewalker M., et al. Tiotropium Respimat add-on is efficacious in symptomatic asthma, independent of T2 phenotype. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:923–935. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.037. e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobieraj D.M., Baker W.L., Nguyen E., et al. Association of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting muscarinic antagonists with asthma control in patients with uncontrolled, persistent asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;319:1473–1484. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casale T.B., Aalbers R., Bleecker E.R., et al. Tiotropium Respimat® add-on therapy to inhaled corticosteroids in patients with symptomatic asthma improves clinical outcomes regardless of baseline characteristics. Respir Med. 2019;158:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buhl R., FitzGerald J.M., Meltzer E.O., et al. Efficacy of once-daily tiotropium Respimat in adults with asthma at GINA Steps 2-5. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2020;60 doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2019.101881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gessner C., Kornmann O., Maspero J., et al. Fixed-dose combination of indacaterol/glycopyrronium/mometasone furoate once-daily versus salmeterol/fluticasone twice-daily plus tiotropium once-daily in patients with uncontrolled asthma: a randomised, Phase IIIb, non-inferiority study (ARGON) Respir Med. 2020;170 doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holguin F., Cardet J.C., Chung K.F., et al. Management of severe asthma: a European respiratory society/American thoracic society guideline. Eur Respir J. 2020;55 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00588-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerstjens H.A.M., Maspero J., Chapman K.R., et al. Once-daily, single-inhaler mometasone-indacaterol-glycopyrronium versus mometasone-indacaterol or twice-daily fluticasone-salmeterol in patients with inadequately controlled asthma (IRIDIUM): a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:1000–1012. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mark FitzGerald J., Hamelmann E., Kerstjens H.A.M., Buhl R. Asthma exacerbations and worsenings in patients aged 1-75 years with add-on tiotropium treatment. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2020;30:38. doi: 10.1038/s41533-020-00193-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papi A., Fabbri L.M., Kerstjens H.A.M., Rogliani P., Watz H., Singh D. Inhaled long-acting muscarinic antagonists in asthma - a narrative review. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;85:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim T.B., Park C.S., Bae Y.J., Cho Y.S., Moon H.B. Factors associated with severity and exacerbation of asthma: a baseline analysis of the cohort for reality and evolution of adult asthma in Korea (COREA) Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:311–317. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60530-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang J.Y., Rhee C.K., Kim J.S., et al. Effect of tiotropium bromide on airway remodeling in a chronic asthma model. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muiser S., Gosens R., van den Berge M., Kerstjens H.A.M. Understanding the role of long-acting muscarinic antagonists in asthma treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maselli D.J., Hanania N.A. Management of asthma COPD overlap. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:335–344. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health NIo. Global Initiative for Asthma Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. NHLBI/WHO Work Shop Report. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddel H.K., Bateman E.D., Becker A., et al. A summary of the new GINA strategy: a roadmap to asthma control. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:622–639. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00853-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bateman E.D., Boulet L., Cru A., et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. GINA executive summary. 2010;2008:31. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00138707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virchow J.C., Kuna P., Paggiaro P., et al. Single inhaler extra fine triple therapy in uncontrolled asthma (TRIMARAN and TRIGGER): two double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019;394:1737–1749. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee L.A., Bailes Z., Barnes N., et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily single-inhaler triple therapy (FF/UMEC/VI) versus FF/VI in patients with inadequately controlled asthma (CAPTAIN): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3A trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:69–84. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkins C. Barriers to achieving asthma control in adults: evidence for the role of tiotropium in current management strategies. Therapeut Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15:423–435. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S177603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy K.R., Chipps B.E. Tiotropium in children and adolescents with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.11.030. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peters S.P., Bleecker E.R., Kunselman S.J., et al. Predictors of response to tiotropium versus salmeterol in asthmatic adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1068–10674.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Averell C.M., Laliberté F., Duh M.S., Wu J.W., Germain G., Faison S. Characterizing real-world use of tiotropium in asthma in the USA. J Asthma Allergy. 2019;12:309–321. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S216932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng W.C., Liao W.C., Wu B.R., et al. Clinical predictors of asthmatics in identifying subgroup requiring long-term tiotropium add-on therapy: a real-world study. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:3785–3793. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.09.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park H.W., Yang M.S., Park C.S., et al. Additive role of tiotropium in severe asthmatics and Arg16Gly in ADRB2 as a potential marker to predict response. Allergy. 2009;64:778–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park S.Y., Kim S., Kim J.H., et al. A randomized, noninferiority trial comparing ICS + LABA with ICS + LABA + LAMA in asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) treatment: the ACO treatment with optimal medications (ATOMIC) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1304–13011.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data-sets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.