Abstract

Surfactant protein A (SP-A), a pulmonary member of the collectin family of proteins, facilitates the rapid clearance of pathogens by upregulating immune cell functions in the lungs. SP-A binds to bacteria and targets them for rapid phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages, but the mechanism by which this stimulation occurs is not clear. To characterize the intracellular events that may be involved, we examined the roles of protein phosphorylation and cytoskeletal polymerization in SP-A-stimulated phagocytosis. In rat alveolar macrophages, SP-A stimulated rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of specific proteins in a dose- and time-dependent manner. The pattern of proteins that were phosphorylated in response to SP-A, as resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, was similar to that observed for immunoglobulin G (IgG)-stimulated macrophages. Both SP-A and IgG stimulated increases in phagocytosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae above levels in the absence of added protein by 394% ± 81% and 200% ± 25%, respectively. Phagocytosis in both cases was dependent on tyrosine kinases, protein kinase C, and actin polymerization but not on microtubule activity. These studies show that SP-A utilizes pathways similar to those used by IgG to increase macrophage phagocytosis of bacteria.

In normal lungs, macrophages are the primary immune cells responsible for clearance of inhaled bacteria (3, 7). These macrophages are resident to the airways and alveoli, and when the respiratory tract is overwhelmed by bacteria, they are responsible for initiating an inflammatory cascade, which results in the recruitment of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and inflammatory macrophages to the site of infection. These inflammatory cells secrete a variety of enzymes and reactive oxygen species that not only kill pathogens but also damage the pulmonary epithelium and thereby compromise gas exchange. To avoid the need to mount this potentially damaging inflammatory response, rapid and efficient clearance of bacteria by alveolar macrophages is essential.

Several proteins that enhance macrophage clearance of bacteria have been identified in the lungs. The most abundant of these proteins is surfactant protein A (SP-A). SP-A is found associated with the surfactant which lines pulmonary airways and is a member of the collectin protein family because of its N-terminal collagen-like domain and carboxy-terminal carbohydrate-binding, or lectin, domain (6, 14). SP-A binds to a variety of pathogens, both bacterial and viral, and functions in innate, or non-antibody-mediated, immunity by modulating a variety of immune cell functions (34).

The best-characterized immune cell interaction of SP-A is that with alveolar macrophages (AM). SP-A stimulates AM chemotaxis (36), enhances AM bacterial clearance (15, 30, 31), alters AM production of reactive oxygen species (17, 31–33), and under some experimental conditions, minimizes AM production of proinflammatory mediators (22). Some studies also suggest that SP-A may act as a proinflammatory stimulus (18, 19), although conflicting data for SP-A as a pro- or anti-inflammatory mediator may be due to differences in SP-A isolation protocols, which yield proteins with variable solubilities and aggregation states (for a review, see reference 34).

The mechanisms by which SP-A modulates macrophage functions have not been elucidated. SP-A binds to macrophages in a dose- and calcium-dependent manner (25, 27), and although several cell surface proteins that interact with SP-A have been identified (2, 8, 21, 24), no SP-A-specific receptor has been associated with an SP-A-specific signaling event in macrophages. SP-A stimulation of macrophages results in a dose-dependent increase in cytosolic free calcium, as well as a dose-dependent and transient generation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (26). This increase in calcium appears to be a prerequisite for SP-A’s stimulatory effect on phagocytosis (26).

To characterize further the signal transduction events associated with SP-A stimulation of macrophage phagocytosis, we examined the ability of SP-A to stimulate macrophage kinases and examined the role of these phosphorylation events in bacterial phagocytosis. We show that SP-A stimulates the rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of specific macrophage proteins in a manner similar to that observed for immunoglobulin G (IgG). We also show that both SP-A and IgG appear to use a similar mechanism to stimulate macrophage phagocytosis: tyrosine phosphorylation, protein kinase C (PKC) activity, and actin polymerization are required, but microtubule activity is not. Furthermore, when both proteins are present, macrophage phagocytosis is enhanced synergistically, suggesting that these two proteins signal via overlapping pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and reagents.

Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein quantification reagents were from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Monoclonal antibody (MAb) PY-20 that recognizes phosphotyrosine residues (9) was obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, Mo.). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG was obtained from Pierce (Rockford, Ill.). Nitrocellulose was obtained from Schleicher & Schuell (Keene, N.H.). Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents were from Amersham (Little Chalfont, England). Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS) was purchased from GIBCO-BRL (Grand Island, N.Y.). Chelerythrin and nocodazole were obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, Calif.). Cytochalasin D, genistein, IgG, and all other chemicals, except as noted, were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company. Unless otherwise indicated, all centrifugation steps were done in a Beckman GS-6R centrifuge with a GH 3.8 swinging bucket rotor.

Proteins.

SP-A was purified from the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of patients with alveolar proteinosis as previously described (22). Briefly, SP-A was extracted from lavage fluid with butanol and sequentially solubilized in octylglucoside and 5 mM Tris (pH 7.4). SP-A was treated with polymyxin B agarose beads to reduce endotoxin contamination. All SP-A preparations were found to have <0.1 pg of endotoxin per μg of SP-A by the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay QCL-1000 (BioWhittaker, Waldersville, Md.). SP-A was stored in 5 mM Tris (pH 7.4) at −20°C.

The purified form of IgG from normal rat and human sera was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. IgG was reconstituted from lyophilized powder in saline and used without further treatment.

Isolation of AM.

AM were isolated as previously described (35) from male Sprague-Dawley rats (200 to 250 g) obtained from Charles River (Raleigh, N.C.). Briefly, rat lungs were lavaged six times with D-PBS (pH 7.2) containing 0.2 mM EGTA. Cells were collected by centrifugation for 10 min at 228 × g, resuspended in the appropriate buffer, and used immediately. Cell purity was determined to be ≥92% (average, 98%) macrophages by Hemacolor differential staining (EM Industries, Inc., Gibbstown, N.J.).

Immunoblotting for phosphorylated proteins.

Cells were resuspended in HEPES-buffered saline (HBS) containing 125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 5 mM glucose, 10 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) at 4 × 106 cells/ml and incubated for various times at 37°C with gentle shaking in the presence of 25 μg of protein per ml (unless otherwise indicated). The cells were collected by centrifugation at 228 × g for 10 min at 4°C and lysed in ice-cold Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg aprotinin/ml, 10 mg of leupeptin/ml, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]) for 15 min on ice. The lysate was centrifuged in an Eppendorf centrifuge (model no. 5415C) at 14,000 × g for 10 min to remove cellular debris. The supernatant was removed, and an aliquot was used for determination of protein content with the BCA assay. Equal amounts of protein were then combined with 5× sample buffer (for a final concentration of 0.05 M Tris, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS), electrophoresed under reducing conditions on SDS–10% polyacrylamide gels with 4% stacking gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and blocked with 50 mM TTBS [Tris (pH 7.6)–150 mM NaCl–0.1% Tween 20] and 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at 37°C or overnight at 4°C. The blots were then probed with mouse antiphosphotyrosine MAb PY-20) diluted 1:2,000 (vol/vol) in TTBS and 1% BSA for 1 h. This procedure was followed by incubation with rabbit anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase diluted 1:30,000 (vol/vol) in TTBS for 1 h. The blots were developed by the ECL method according to manufacturer’s specifications.

Bacteria.

A clinical isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae from a patient at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Medical Center was a generous gift of Roy Hopfer (Medical Microbiology Laboratory, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Medical Center). Streptococcus spp. were cultured on TSA II agar containing 5% sheep blood (Becton-Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.). Titers of bacteria were used to correlate the optical density of a bacterial suspension at 660 nm (OD660) to CFU per milliliter.

Labeling of bacteria with FITC.

Twenty-four hours after streaking, bacteria were harvested from agar plates, suspended in 5 ml of D-PBS (pH 7.2), and centrifuged 1 min at 228 × g to remove any large aggregates or agar. The OD660 of the resulting supernatant was measured to determine bacterial concentration. The suspension was then centrifuged, and the bacteria were resuspended in 0.9 ml of D-PBS (pH 7.2) and heated to 95°C for 10 min to kill the bacteria. The heat-killed bacteria were then sedimented by centrifugation and resuspended in 1 ml of 0.1 M sodium carbonate (pH 9.0). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) was added as a 10-mg/ml stock in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml, and the suspension was incubated for 1 h in the dark at room temperature with gentle shaking. Labeled bacteria were washed four times for 5 min each time with D-PBS (pH 7.2) to remove unconjugated fluorophore, diluted in D-PBS to an OD660 of 0.4, and stored in aliquots of 0.1 ml at −80°C.

Phagocytosis assay for fluorescence microscopy.

AM were suspended in HBS at 4 × 106 cells/ml and pretreated with the indicated pharmacological inhibitors or DMSO (vehicle control) for 10 min at room temperature. FITC-labeled S. pneumoniae was then added at a ratio of 10:1 (bacteria to AM), and SP-A or IgG was added at a concentration of 25 μg/ml. The incubation was continued at 37°C for 1 h with gentle shaking in the dark. Cells were then washed three times with HBS and resuspended at 25 × 106 cells/ml of HBS. Fluorescence of extracellular bacteria was quenched by the addition of ethidium bromide at 40 μg/ml (5), and an aliquot of cells was immediately mounted on a glass slide and scored for percent cells containing internalized fluorescent bacteria by fluorescence microscopy (magnification, ×100).

Phagocytosis assay for flow cytometry.

Additional phagocytosis analyses were done by flow cytometry because of increased sensitivity and efficiency of data acquisition. AM (0.5 × 105) were suspended in PBS plus 0.1% BSA and incubated with FITC-labeled S. pneumoniae at a ratio of 10:1 (bacteria to AM) in the presence or absence of the indicated proteins for 1 h at 37°C with gentle shaking in the dark. Final assay volume was 0.4 ml. Cells were then washed three times with ice-cold PBS (without calcium or magnesium) and split into two samples. One set was fixed in 1% formaldehyde, and the other was resuspended in 0.2 mg of trypan blue per ml in 0.02 M NaC2H3O2 (pH 5.8) to quench the fluorescence of extracellular bacteria. Trypan blue-treated cells were immediately washed two times prior to fixing with 1% formaldehyde. AM phagocytosis was assessed by flow cytometry; data are expressed as the percent increase in cell-associated fluorescence with the trypan blue-treated cells above that of the control with no added protein.

Statistical analysis.

Data were compared by the Student t test for unpaired samples. Values were considered significant at P of <0.05.

RESULTS

SP-A-stimulates protein phosphorylation in AM.

To examine the ability of SP-A to stimulate phosphorylation of macrophage proteins, freshly isolated AM were incubated in the presence of 25 μg of SP-A per ml, a concentration previously shown to stimulate phagocytosis and chemotaxis in AM (30, 36). Western blot analysis of cell lysates showed that SP-A triggers rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of AM proteins. The sizes of phosphorylated proteins are approximately 132, 110, 81, and 65 kDa with analysis under reducing conditions by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1). Protein phosphorylation was detectable after a 30-s exposure to SP-A (data not shown). Activity peaked within 3 to 5 min and gradually decreased to baseline over the next hour (Fig. 1B). As a protein control, BSA at 25 μg/ml was tested, and no phosphorylation activity was detected after 5 min (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

SP-A stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation in rat AM. (A) Time course of SP-A stimulation of phosphorylation. AM were incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 25 μg of SP-A per ml at 37°C for the indicated times. Cell lysates were subjected to BCA protein quantitation, and equivalent amounts of protein for each sample were analyzed by SDS–10% PAGE and antiphosphotyrosine immunoblotting. Images of blots were acquired in Adobe Photoshop. Molecular mass markers in kilodaltons (kD) appear on the left; some major substrates that showed enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation in the presence of SP-A are indicated by arrows at the right. (B) Graph of time-dependent change of SP-A-stimulated phosphorylation signal intensity as a percent of that of the control. A vertical section of each condition in panel A was analyzed with NIH Image for signal intensity and reported as a percent of the appropriate unstimulated cell control. Data represent a minimum of three experiments.

The degree of phosphorylation was variable between experiments. For some experiments, SP-A stimulated phosphorylation of proteins that were not phosphorylated in unstimulated control cells. In other experiments, SP-A treatment enhanced phosphorylation of proteins that were also phosphorylated in control cells.

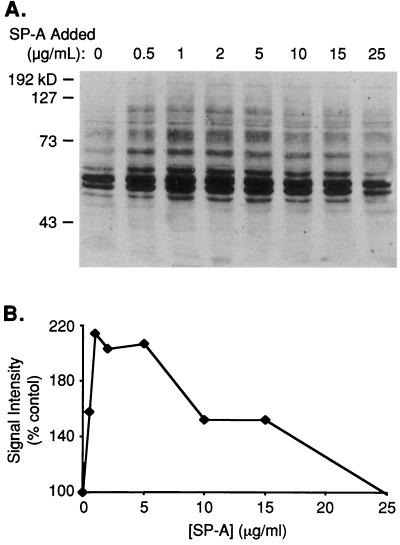

In order to analyze the dose dependence of the SP-A effect, AM were incubated for 3 min with 0.5 to 25 μg of SP-A per ml, and the lysate was subjected to Western blotting (Fig. 2A). The effects of SP-A on phosphorylation were biphasic; although all concentrations tested enhanced phosphorylation to some extent, phosphorylation was maximally stimulated at concentrations of approximately 1 to 5 μg/ml. Concentrations greater or less than this were less effective. The relationship between signal intensity and the SP-A concentration is shown in Fig. 2B.

FIG. 2.

Stimulation of tyrosine phosphorylation by SP-A is dose dependent in AM. (A) Western blot of SP-A dose response. Samples were processed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Molecular mass markers in kilodaltons (kD) appear on the left. (B) Graph of dose-dependent change of SP-A-stimulated phosphorylation signal intensity as a percent of that of the control. Data represent three experiments, although other experiments using 25 μg of SP-A per ml frequently showed significant stimulation of phosphorylation.

An AM-like cell line (NR8383) was also examined for SP-A-stimulated tyrosine kinase activity, but significant activity above background was not detected (data not shown).

The ability of SP-A to stimulate serine or threonine phosphorylation activity was also examined, but preliminary studies showed no phosphorylation activity as detected by Western blotting with antiphosphoserine or antiphosphothreonine antibodies when cells were incubated with SP-A for up to 1 h (data not shown).

IgG stimulates protein phosphorylation in AM.

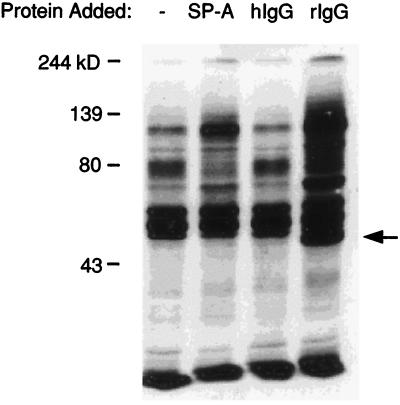

Previous studies have shown that IgG stimulates the rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of a number of proteins in peritoneal macrophages (11). Therefore, the phosphorylation patterns of proteins in AM stimulated by both IgG and SP-A were compared. Figure 3 shows a Western blot of the lysate from cells stimulated with SP-A (lane b), human IgG (lane c), or rat IgG (lane d), each at a concentration of 25 μg/ml. As observed with mouse peritoneal macrophages and mouse IgG (11), rat IgG stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation in rat AM; however, human IgG did not stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation in rat AM. The proteins phosphorylated in response to rat IgG were similar in size to those phosphorylated in response to SP-A, although the degree of phosphorylation varied somewhat.

FIG. 3.

Rat IgG, like SP-A, stimulates rapid tyrosine phosphorylation in AM. AM were incubated in the absence of protein (−) or in the presence of SP-A, human IgG (hIgG), or rat IgG (rIgG) (each at 25 μg/ml) for 3 min at 37°C and processed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Molecular mass markers in kilodaltons (kD) appear on the left. The arrow on the right marks binding of the secondary antibody to IgG. Data represent a minimum of three experiments.

It is possible that the phosphorylation activity stimulated by SP-A was due to the small amount of IgG that contaminates the alveolar proteinosis SP-A preparations (12). Several SP-A preparations were examined, and the IgG contamination was consistently less than 1% by weight. When macrophages were incubated with a concentration of human IgG equivalent to the 1% contamination in SP-A (0.25 μg/ml), no increase in the level of phosphorylated proteins was observed (data not shown). Rat IgG at a lower concentration (2.5 μg/ml) showed little to no stimulation of phosphorylation (data not shown).

Increase in S. pneumoniae phagocytosis by AM in the presence of SP-A and IgG.

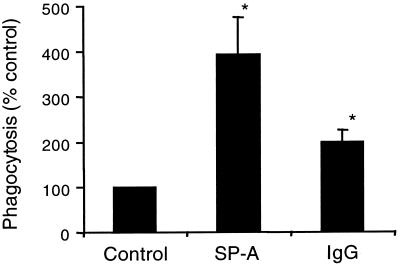

The effects of SP-A and rat IgG on macrophage phagocytosis of fluorescently labeled S. pneumoniae were examined. As determined by fluorescence microscopy, at 25 μg/ml, SP-A increased phagocytosis 394% ± 81% above that of the control, and IgG increased phagocytosis 200% ± 25% above that of the control (Fig. 4). As with the microscopy assay, flow cytometry phagocytosis assays also showed that SP-A and IgG enhanced AM phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae, and this enhancement was dose dependent (Table 1). It is not clear why the effects of SP-A were greater in the flow analyses, but it could be related to increased sensitivity of the assay or technical differences between the two assays (e.g., cell concentrations and quenching agents).

FIG. 4.

SP-A and IgG stimulate an increase in phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae by AM. AM were incubated with FITC-labeled S. pneumoniae in the absence of protein (control) or in the presence of 25 μg of SP-A or rat IgG per ml. Fluorescence of extracellular bacteria was quenched with ethidium bromide, and the percent phagocytosis was determined by fluorescence microscopy. Values are reported as the mean percent phagocytosis of the control (no protein) ± standard errors of the means (n = 7). ∗, significantly greater than control (P < 0.01 by one-tailed t test).

TABLE 1.

SP-A and IgG stimulate AM phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae in a dose-dependent manner

| Treatment | % Phagocytosis of AM treated with protein concentration (μg/ml) ofa:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | 5 | 25 | |

| SP-A | 100 | 661 ± 92 | 1,944 ± 1071 | 2,717 ± 945 |

| IgG | 100 | 150 ± 52 | 188 ± 65 | 341 ± 74 |

Values were determined by flow cytometry and are reported as the mean percent phagocytosis in the absence of protein treatment (control) ± standard errors of the means (n = 3 or 4).

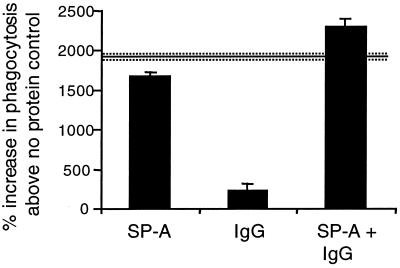

To determine if the SP-A and IgG effects were additive, SP-A and IgG (25 μg/ml each) were coincubated with AM and S. pneumoniae. SP-A and IgG together increased phagocytosis to a greater extent than either protein alone. Figure 5 shows that this cooperative increase in phagocytosis is synergistic. The percent increase in phagocytosis with SP-A plus IgG is 38% of that SP-A alone; if the effects between SP-A and IgG were only additive, the percent increase above that with SP-A alone would have been 14%.

FIG. 5.

SP-A and IgG increase AM phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae synergistically. AM were incubated with FITC-labeled S. pneumoniae in the absence of protein (control [data not shown]) or in the presence of 25 μg of SP-A or rat IgG per ml or both. Fluorescence of extracellular bacteria was quenched with trypan blue, and phagocytosis was determined by flow cytometry. Values are reported as mean percent increase in phagocytosis of the control ± standard errors of the means (n = 3). Solid line represents the additive total effects of SP-A and IgG, and the dashed lines represent standard errors of the means.

Phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae by the AM-like cell line NR8383 was also examined. At 25 μg/ml, both SP-A and IgG increased phagocytosis (155 and 142%, respectively) but to a significantly less extent than that was observed for AM. Phagocytosis in the absence of additional protein was, however, greater for the NR8383 cells than for AM, 41 and 2%, respectively.

Effect of phosphorylation inhibitors on SP-A and IgG-stimulated phagocytosis.

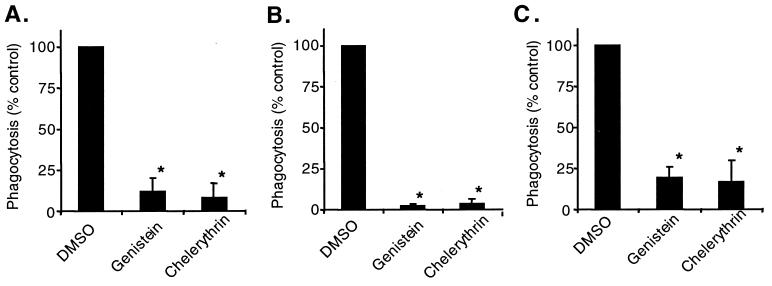

Because SP-A and IgG stimulated the phosphorylation of proteins with similar molecular masses, and the stimulation of phagocytosis was synergistic, we hypothesized that SP-A and IgG were utilizing similar signal transduction pathways for phagocytosis. To test this hypothesis, the ability of macrophages to phagocytose bacteria in the presence of various phosphorylation inhibitors was examined (Fig. 6). Inhibitors were added to the cells 10 min prior to the addition of bacteria and SP-A or IgG, and data are reported as the percent phagocytosis of the inhibitor solvent (DMSO) control. Genistein greatly reduced phagocytosis levels of S. pneumoniae both in the absence of protein and in the presence of SP-A or IgG. IgG data are comparable to those reported by Allen and Aderem with other tyrosine phosphorylation inhibitors (1).

FIG. 6.

Genistein and chelerythrin inhibit baseline and SP-A- and IgG-stimulated phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae by AM. AM were treated with 0.1% DMSO (inhibitor solvent), 150 μM genistein (tyrosine phosphorylation inhibitor), or 12 μM chelerythrin (PKC inhibitor). FITC-labeled S. pneumoniae was then added to the cells with no protein (A), 25 μg of SP-A per ml (B), or 25 μg of rat IgG per ml and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Percent phagocytosis was determined by scoring of cells by fluorescence microscopy in the presence of ethidium bromide. Values are reported as the mean percent phagocytosis of the DMSO control in the absence of protein or in the presence of SP-A or IgG ± standard errors of the means (n = 3 or 4). ∗, significantly less than that of the control (P < 0.01 by one-tailed t test).

Although no serine or threonine phosphorylation activity in the presence of SP-A was detected by Western blotting, chelerythrin, a PKC-specific inhibitor, significantly inhibited baseline, SP-A-stimulated, and IgG-stimulated phagocytosis (Fig. 6). Calphostin C, another inhibitor of PKC, did not inhibit phagocytosis to the same extent as did chelerythrin (data not shown). These data are also comparable to earlier reports of PKC and IgG stimulation of peritoneal macrophages (1, 10).

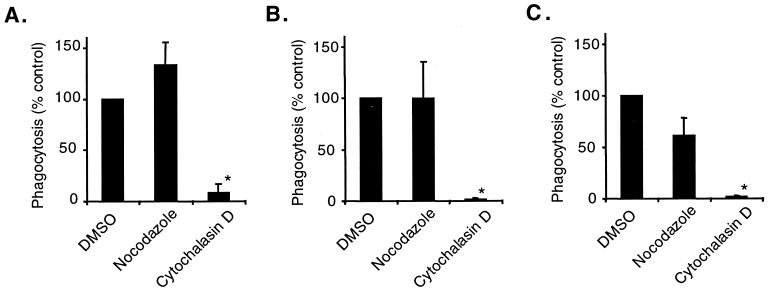

Effect of cytoskeletal inhibitors on SP-A- and IgG-stimulated phagocytosis.

The requirement of various cytoskeletal elements for SP-A- and IgG-stimulated phagocytosis was also examined. Because microtubules are required for some, but not all, types of phagocytosis (1), the effects of nocodazole, an inhibitor of microtubule formation, was examined. Nocodazole had no effect on baseline, SP-A-stimulated, or IgG-stimulated phagocytosis (Fig. 7). On the other hand, cytochalasin D, which inhibits the formation of filamentous actin, inhibited baseline and SP-A- and IgG-stimulated phagocytosis (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Cytochalasin D, but not nocodazole, inhibits baseline and SP-A- and IgG-stimulated phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae by AM. AM were treated with 0.1% DMSO (inhibitor solvent), 2 μg of nocodazole (inhibitor of microtubule formation) per ml, or 2 μM cytochalasin D (inhibitor of filamentous actin formation). FITC-labeled S. pneumoniae was then added to the cells with no protein (A), 25 μg of SP-A per ml (B), or 25 μg of rat IgG per ml (C) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Percent phagocytosis was determined by scoring of cells by fluorescence microscopy in the presence of ethidium bromide. Values are reported as the mean percent phagocytosis of the DMSO control in the absence of protein or in the presence of SP-A or IgG ± standard errors of the means (n = 3). ∗, significantly less than that of the control (P < 0.01 by one-tailed t test).

DISCUSSION

In summary, this study describes intracellular signaling events in AM that are stimulated by SP-A. We show that SP-A stimulates the rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of specific proteins in a dose- and time-dependent manner, and through the use of pharmacological inhibitors, we also show that SP-A-mediated phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae by macrophages requires the activity of tyrosine kinases, PKC, and actin polymerization but not microtubule activity. These findings demonstrate similarities between SP-A and IgG stimulation of macrophage phagocytosis and show that the two proteins act synergistically to enhance phagocytosis. This suggests that these two proteins are utilizing similar and possibly convergent intracellular signaling pathways.

SP-A very rapidly stimulates phosphorylation of specific proteins in AM. This stimulation occurs within 30 s of macrophage exposure to SP-A, and although total phosphorylation decreased over the course of an hour, some SP-A-stimulated phosphorylation persisted. SP-A stimulation was also clearly dose dependent in a biphasic manner as exemplified in Fig. 2. The ability of 25 μg of SP-A per ml to stimulate phosphorylation varied significantly between experiments. This result may be due to animal variability or to the aggregation state of the protein, as the SP-A used in these studies is multimeric and has various aggregate sizes (12); variable SP-A aggregation may cause subtle shifts in the phosphorylation dose-response curve.

SP-A and IgG appear to stimulate phosphorylation of similarly sized proteins. There are at least two potential explanations for this: (i) SP-A may stimulate signaling cascades similar to those of IgG, or (ii) an IgG contaminant of the SP-A preparation (≤1%) may be responsible for the stimulation.

We believe the first of these two explanations is the most likely. The SP-A used in these assays was purified from lavage fluid of patients with a condition called alveolar proteinosis. The etiology of the disease is unknown, and it is characterized by an excess of surfactant proteins and lipids in airways and alveoli (29). The IgG contaminant in these SP-A preparations is consistently ≤1% of the SP-A concentration. The IgG could not be removed by protein A-Sepharose extraction, size exclusion chromatography, or anion-exchange chromatography (data not shown). It has been reported that IgG can associate with SP-A (13, 20), but the physiological relevance of this interaction is not known.

It seems unlikely that the SP-A-stimulated phosphorylation described here is due to the small amount of human IgG present, because neither a high nor a low concentration of human IgG (25 or 0.25 μg/ml, respectively) stimulated phosphorylation. Also, rat IgG tested at a low concentration (2.5 μg/ml) showed reduced, almost undetectable, stimulation of phosphorylation. These studies do not, however, rule out the possibility that SP-A augments IgG function in a way that enables human IgG to stimulate phosphorylation.

Both SP-A and IgG enhance AM phagocytosis of S. pneumoniae in a dose-dependent manner, although SP-A has a much greater capacity for enhancing phagocytosis than does IgG. The different abilities of these proteins to enhance phagocytosis may be due to differences in the multimeric nature of the proteins or to differences in the number of receptors on the macrophages. Also, SP-A is known to bind, although not to aggregate, S. pneumoniae (30), so it may act as a more effective opsonin than IgG, as it is not known whether IgG binds to the bacteria.

The AM-like cell line NR8383 was examined for SP-A responsiveness. Little or no stimulation of tyrosine phosphorylation was detectable, although SP-A did enhance NR8383 phagocytosis of bacteria (155% of control), albeit to a less extent than AM (2,717% of control). The failure to detect clear phosphorylation could be because the basal activation level of these cells is greater than that of AM; SDS analysis of equivalent amounts of protein from NR8383 and AM revealed a greater amount of phosphorylated proteins in the NR8383 lysate than in the AM lysate. Also, a greater percentage of NR8383 cells than of AM were phagocytically active in the absence of protein stimulation (41 and 2%, respectively). Alternatively, the mechanism of SP-A stimulation of NR8383 phagocytosis may differ from that of stimulation of AM phagocytosis.

Tyrosine kinase activity, PKC activity, and actin polymerization are all necessary for both SP-A and IgG stimulation of phagocytosis. These data, in conjunction with the fact that SP-A and IgG stimulate similar patterns of protein phosphorylation and both act synergistically to enhance AM phagocytosis, suggest that SP-A and IgG are using some of the same signal transduction pathways to enhance phagocytosis.

Although SP-A and IgG have some common functions, not all functions are the same. For example, in response to lipopolysaccharide, SP-A reduces tumor necrosis factor alpha production by macrophages (22), whereas IgG augments production (28). In addition, it has been previously reported that SP-A stimulation of macrophages causes a rapid rise in intracellular free calcium concentrations ([Ca]i) and this increase is required for SP-A enhancement of phagocytosis (26). This contrasts with IgG-mediated phagocytosis, which occurs independently of large increases in total cell [Ca]i (4, 23), although Fc receptor clustering results in an increase in [Ca]i (4, 37). This finding suggests that SP-A and IgG use similar but not identical signaling pathways to enhance macrophage phagocytosis.

An approach similar to the one employed in this study has been used to compare IgG- and complement-mediated phagocytosis (1, 16). Unlike SP-A and IgG, complement stimulates phagocytosis independently of tyrosine kinase activity and requires microtubule activity. Electron microscopy showed that phagocytosis of complement-coated particles involves the “sinking” of the particle into the body of the cell (1). In contrast, IgG- and SP-A-mediated phagocytosis involves the extension of cytoplasmic processes from the cell surface which then engulf the target particle (SP-A data [29a]). SP-A and IgG may activate macrophages in such a way that more processes are extended from the cell, resulting in phagocytosis of a greater number of particles.

These data offer a clearer understanding of how SP-A modulates macrophage function. The similarities between unstimulated and SP-A- and IgG-stimulated phagocytosis suggest that these proteins upregulate a general phagocytic machinery within macrophages. Further elucidation of the exact mechanism of SP-A-enhanced phagocytosis and its synergistic effects with IgG may offer a therapeutic tool whereby AM may be pharmacologically stimulated to clear bacteria at a more rapid rate with minimal damage to surrounding tissues.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 HL-51134, Cell and Molecular Biology NIH Training Grant 5 T32 GM07184, and Pharmacological Sciences Training Grant GM07105.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen L A, Aderem A. Molecular definition of distinct cytoskeletal structures involved in complement- and Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages. J Exp Med. 1996;184:627–637. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chroneos Z C, Abdolrasulnia R, Whitsett J A, Rice W R, Shepherd V L. Purification of a cell-surface receptor for surfactant protein A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16375–16383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crystal R G, West J B, editors. The lung: scientific foundations. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Virgilio F, Meyer B C, Greenberg S, Silverstein S C. Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis occurs in macrophages at exceedingly low cytosolic Ca2+ levels. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:657–666. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drevets D A, Campbell P A. Macrophage phagocytosis: use of fluorescence microscopy to distinguish between extracellular and intracellular bacteria. J Immunol Methods. 1991;142:31–38. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90289-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein J, Eichbaum Q, Sheriff S, Ezekowitz R A B. The collectins in innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fels A O S, Cohn Z A. The alveolar macrophage. J Appl Physiol. 1986;60:353–369. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geertsma M F, Nibbering P H, Haagsman H P, Daha M R, van Furth R. Binding of surfactant protein A to C1q receptors mediates the phagocytosis of Staphylococcus aureus by monocytes. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:L578–L584. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.267.5.L578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glenney J R, Jr, Chen W S, Lazar C S, Walton G M, Zokas L M, Rosenfeld M G, Gill G N. Ligand-induced endocytosis of the EGF receptor is blocked by mutational inactivation and by microinjection of anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies. Cell. 1988;52:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90405-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg S, Chang P, Silverstein S C. Tyrosine phosphorylation is required for Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in mouse macrophages. J Exp Med. 1993;177:529–534. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg S, Chang P, Silverstein S C. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the gamma subunit of Fc gamma receptors, p72syk, and paxillin during Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3897–3902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hattori A, Kuroki Y, Katoh T, Takahashi H, Shen H Q, Suzuki Y, Akino T. Surfactant protein A accumulating in the alveoli of patients with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis—oligomeric structure and interaction with lipids. Am J Resp Cell Mol Biol. 1996;14:608–619. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.14.6.8652189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hattori A, Kuroki Y, Takahashi H, Sohma H, Akino T. Immunoglobulin G is associated with surfactant protein A aggregate isolated from patients with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1785–1788. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmskov U, Malhotra R, Sim R B, Jensenius J C. Collectins: collagenous C-type lectins of the innate immune defense system. Immunol Today. 1994;15:67–73. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kabha K, Schmegner J, Keisari Y, Parolis H, Schlepperschaefer J, Ofek I. SP-A enhances phagocytosis of Klebsiella by interaction with capsular polysaccharides and alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol. 1997;16:L344–L352. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.2.L344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan G. Differences in the mode of phagocytosis with Fc and C3 receptors in macrophages. Scand J Immunol. 1977;6:797–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1977.tb02153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katsura H, Kawada H, Konno K. Rat surfactant apoprotein A (SP-A) exhibits antioxidant effects on alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1993;9:520–525. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/9.5.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kremlev S G, Phelps D S. Surfactant protein A stimulation of inflammatory cytokine and immunoglobulin production. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:L712–L719. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.267.6.L712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kremlev S G, Umstead T M, Phelps D S. Surfactant protein A regulates cytokine production in the monocytic cell line THP-1. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L996–L1004. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.5.L996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuroki Y, Tsutahara S, Shijubo N, Takahashi H, Shiratori M, Hattori A, Honda Y, Abe S, Akino T. Elevated levels of lung surfactant protein A in sera from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:723–729. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.3.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malhotra R, Thiel S, Reid K B, Sim R B. Human leukocyte C1q receptor binds other soluble proteins with collagen domains. J Exp Med. 1990;172:955–959. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McIntosh J C, Mervin-Blake S, Conner E, Wright J R. Surfactant protein A protects growing cells and reduces TNF-alpha activity from LPS-stimulated macrophages. Am J Physiol. 1996;15:L310–L319. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.2.L310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNeil P L, Swanson J A, Wright S D, Silverstein S C, Taylor D L. Fc-receptor-mediated phagocytosis occurs in macrophages without an increase in average [Ca++]i. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:1586–1592. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.5.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nepomuceno R R, Henschen-Edman A H, Burgess W H, Tenner A J. cDNA cloning and primary structure analysis of C1aRp, the human C1q/MBL/SPA receptor that mediated enhanced phagocytosis in vitro. Immunity. 1997;6:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohmer-Schrock D, Schlatterer C, Plattner H, Schlepperschafer J. Interaction of lung surfactant protein-A with alveolar macrophages. Microsc Res Technol. 1993;26:374–380. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070260505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohmer-Schrock D, Schlatterer C, Plattner H, Schlepper-Schafer J. Lung surfactant protein A (SP-A) activates a phosphoinositide/calcium signaling pathway in alveolar macrophages. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:3695–3702. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.12.3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pison U, Wright J R, Hawgood S. Specific binding of surfactant protein SP-A to rat alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:L412–L417. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1992.262.4.L412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richard C A, Gudewicz P W, Loegering D J. IgG-coated erythrocytes augment the lipopolysaccharide-stimulated increase in serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R171–R177. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.1.R171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen S H, Castleman B, Liebow A A. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 1958;258:1123–1142. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195806052582301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Savov, J. Unpublished data.

- 30.Tino M J, Wright J R. Surfactant protein A stimulates phagocytosis of specific pulmonary pathogens by alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol. 1996;14:L677–L688. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.4.L677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Iwaarden F, Welmers B, Verhoef J, Haagsman H P, van Golde L M G. Pulmonary surfactant protein A enhances the host-defense mechanism of rat alveolar macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1990;2:91–98. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/2.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Iwaarden J F, Shimizu H, Van Golde P H M, Voelker D R, Van Golde L M G. Rat surfactant protein D enhances the production of oxygen radicals by rat alveolar macrophages. Biochem J. 1992;286:5–8. doi: 10.1042/bj2860005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weissbach S, Neuendank A, Pettersson M, Schaberg T, Pison U. Surfactant protein A modulates release of reactive oxygen species from alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:L660–L666. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.267.6.L660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright J R. Immunomodulatory functions of surfactant. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:931–962. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright J R, Wager R E, Hawgood S, Dobbs L, Clements J A. Surfactant apoprotein Mr = 26,000–36,000 enhances uptake of liposomes by type II cells. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:2888–2894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright J R, Youmans D C. Pulmonary surfactant protein-A stimulates chemotaxis of alveolar macrophage. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:L338–L344. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.264.4.L338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young J D, Ko S S, Cohn Z A. The increase in intracellular free calcium associated with IgG gamma 2b/gamma 1 Fc receptor-ligand interactions: role in phagocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5430–5434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.17.5430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]