Abstract

Even with optimal treatment, some persons with severe and persistent mental illness do not achieve a level of mental health, psychosocial functioning and quality of life that is acceptable to them. With each unsuccessful treatment attempt, the probability of achieving symptom reduction declines while the probability of somatic and psychological side effects increases. This worsening benefit–harm ratio of treatment aiming at symptom reduction has motivated calls for implementing palliative approaches to care into psychiatry (palliative psychiatry). Palliative psychiatry accepts that some cases of severe and persistent mental illness can be irremediable and calls for a careful evaluation of goals of care in these cases. It aims at reducing harm, relieving suffering and thus improving quality of life directly, working around irremediable psychiatric symptoms. In a narrow sense, this refers to patients likely to die of their severe and persistent mental illness soon, but palliative psychiatry in a broad sense is not limited to end-of-life care. It can – and often should – be integrated with curative and rehabilitative approaches, as is the gold standard in somatic medicine. Palliative psychiatry constitutes a valuable addition to established non-curative approaches such as rehabilitative psychiatry (which focuses on psychosocial functioning instead of quality of life) and personal recovery (a journey that persons living with severe and persistent mental illness may undertake, not necessarily accompanied by mental health care professionals). Although the implementation of palliative psychiatry is met with several challenges such as difficulties regarding decision-making capacity and prognostication in severe and persistent mental illness, it is a promising new approach in caring for persons with severe and persistent mental illness, regardless of whether they are at the end of life.

Keywords: Severe and persistent mental illness, goals of care, palliative psychiatry, irremediability, futility, suffering, quality of life, end of life

Introduction

Due to advances in psychiatry over the last decades, there are now evidence-based treatment options for nearly all mental disorders. However, in some cases of severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI; Zumstein and Riese, 2020), treatment response is not sufficiently good to alleviate patients’ suffering and improve their psychosocial functioning and quality of life to a level they deem acceptable. With each unsuccessful treatment attempt, the evidence base for further treatment becomes thinner and the probability of achieving symptom reduction declines (Kahn et al., 2018; Rush et al., 2009) while the probability of side effects increases. The latter include medication side effects (e.g. metabolic syndrome from antipsychotics contributing to the excess mortality of persons with SPMI; Correll et al., 2017) and psychological side effects (e.g. a sense of failure and hopelessness which can worsen the underlying SPMI, for instance in chronic depression; Berk et al., 2012). Thus, the benefit–harm ratio of treatment aiming at symptom reduction worsens with each failed attempt, which has prompted calls for palliative approaches in psychiatry (palliative psychiatry; Berk et al., 2012; Levitt and Buchman, 2021; Lindblad et al., 2019; Trachsel et al., 2016; Westermair et al., 2021).

Like preventive psychiatry (Trivedi et al., 2014) and rehabilitative psychiatry (Roessler, 2006), palliative psychiatry is a subdiscipline of psychiatry. The basic assumptions and principles of palliative psychiatry are as follows:

SPMI (symptoms)1 can, in some cases, be irremediable, i.e., unresponsive to optimal treatment.

Ineffective and burdensome interventions should not automatically be continued but necessitate a careful evaluation and possibly a change of the goals of care (Westermair et al., 2021).

When symptom reduction is in all likelihood unattainable, quality of life becomes the priority and thus the yardstick for assessing possible interventions (Trachsel et al., 2016).

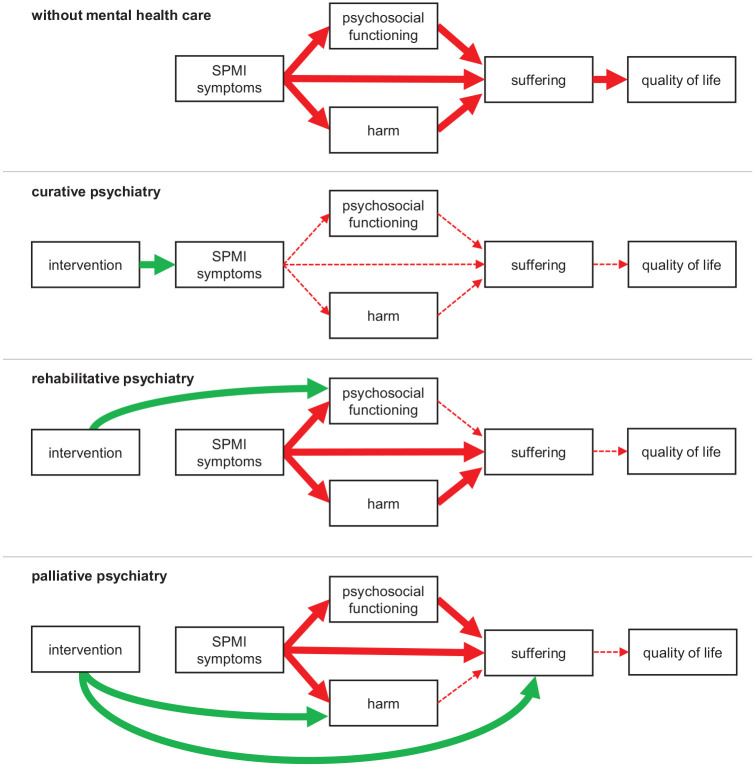

Of course, curative psychiatry, too, aims at improving patients’ quality of life. The difference lies in the strategies that are applied in working towards that goal: whereas curative psychiatry strives at improving quality of life by way of symptom reduction or even complete remission,2 palliative psychiatry aims at relieving suffering and thus improving quality of life directly by working around irremediable SPMI symptoms (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual overview of different approaches to mental health care.

Harmful effects in red and beneficial effects in green. While many more associations between the depicted constructs are conceivable, for reasons of clarity, we only show the associations most important for clarifying the conceptual differences between subdisciplines of psychiatry. ‘SPMI symptoms’ refer to the core symptoms of the respective SPMI, such as fear of gaining weight in anorexia nervosa. ‘Harm’ refers to negative consequences of the SPMI and can be biological, psychological, social or economic. ‘Suffering’ is the felt quality of unfulfilled basic needs threatening the existence or integrity of the person. All subdisciplines of psychiatry ultimately aim at improving patients’ quality of life, but differ in the strategies they employ in this pursuit. Traditional curative psychiatry uses interventions aiming at symptom remission (or at least reduction), which – if successful – indirectly reduces harm and suffering associated with the SPMI, improves psychosocial functioning and ultimately quality of life. When SPMI symptoms are most likely irremediable, rehabilitative and palliative psychiatry offer alternative care approaches. Rather than at symptom reduction, rehabilitative psychiatry aims directly at improved psychosocial functioning, and palliative psychiatry aims directly at harm reduction (e.g. supplying patients with sterile injection equipment to prevent infections; prescribing calcium and vitamin D for osteopenia in anorexia nervosa to prevent fractures) and/or relief of suffering (e.g. prescribing diazepam to relieve anxiety induced by therapy-refractory persecutory delusions). Often, palliative psychiatry interventions will aim at both harm reduction and relief of suffering (e.g. supervised injectable heroin treatment to reduce the risk of overdoses and alleviate craving). While palliative psychiatry in a broad sense refers to any approaches aiming at reducing harm and relieving suffering by means other than reduction of SPMI symptoms or improvement of psychosocial functioning, palliative psychiatry in a narrow sense refers to such approaches in patients likely to die of their SPMI in the near future.

The current debate about the necessity to establish palliative psychiatry (Berk et al., 2012; Lindblad et al., 2019; Trachsel et al., 2016; Trauer, 2012) should be based on conceptual clarity (Gieselmann and Vollmann, 2020). As the concept of palliative care itself has undergone considerable change since its emergence, the notion of palliative psychiatry may take on different meanings depending on which concept of palliative care one relies on. In what follows, we will summarize the early and the modern concept of palliative care and then apply them to psychiatry.

A brief history of palliative care

When Cicely Saunders founded the first modern hospice in 1967, the concept was readily embraced in high-income countries (Meghani, 2004). In the following two decades, ‘palliative care’ was used interchangeably with ‘hospice care’ and understood as care for patients dying from cancer. In line with this origin, in a recent survey, nearly half of psychiatrists in Switzerland felt that the term ‘palliative’ directly relates to end-of-life care (Trachsel et al., 2019).

However, after new health care technologies extended illness trajectories (such as dialysis for kidney failure), the concept of palliative care broadened considerably during the 1990s (Guo et al., 2012; Meghani, 2004). Palliative care was now seen as a philosophy of care and set of strategies that not only guide care for patients at the end of life, but all patients with life-threatening illnesses:

Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual. (Sepúlveda et al., 2002: 94)

In a recent Delphi process, the target population of palliative care was defined even broader as ‘individuals across all ages with serious health related suffering because of severe illness and especially of those near the end of life’ (Radbruch et al., 2020: 8). Severe illness, in turn, is ‘a condition that carries a high risk of mortality, negatively impacts quality of life and daily function, and/or is burdensome in symptoms, treatments, or caregiver stress’ (Kelley, 2014: 985). Thus, while the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness remains a sufficient eligibility criterion for palliative care, it is no longer necessary; palliative care includes, but goes beyond end-of-life care. Similarly, palliative care is no longer seen as incompatible with curative approaches and early integration of palliative care with disease-modifying care is now the gold standard, e.g., in oncology (Ferrell et al., 2017; Jordan et al., 2018). Indeed, in recent surveys, half of the respondents of psychiatrists in India found the term ‘palliative’ to not directly relate to end-of-life care, as did a third of the respondents in Switzerland (Stoll et al., 2022; Trachsel et al., 2019).

Importantly, in none of these definitions is eligibility for palliative care limited to specific diagnoses, and palliative care ‘should be delivered based on need rather than prognosis’ (Radbruch et al., 2020). Accordingly, some persons suffering from SPMI may be eligible for palliative care (Berk et al., 2012; Lindblad et al., 2019; Trachsel et al., 2016). About three in four psychiatrists in Switzerland and India indicated that palliative approaches are important in caring for some persons with mental disorders, even in the absence of life-threatening somatic illnesses (Stoll et al., 2022; Trachsel et al., 2019).

Palliative psychiatry in a narrow sense

Like palliative care for patients with advanced dementia3 (Eisenmann et al., 2020), palliative psychiatry in a narrow sense refers to the provision of end-of-life care for persons dying from a mental illness. An example is hospice care for persons dying from anorexia nervosa (Lopez et al., 2010; O’Neill et al., 1994; Trachsel et al., 2015). In these case reports, further curative treatment such as artificial refeeding was deemed futile and adding to the patients’ suffering.4 The goal of care was changed to optimizing quality of life, and the patients were referred to hospice care.

Another example comes from the case of a patient with schizophrenia and severe chronic agitated/malignant catatonia who, over several months of hospitalization, repeatedly required intubation and sedation to manage behavioural and mental symptoms. Considering the lack of appreciable clinical benefit from treatment and his irremediable suffering, the patient’s parents (as appointed substitute decision-makers) ultimately decided to forgo further life-sustaining treatment, and the patient died of aspiration pneumonia (Trachsel et al., 2022).

Two adjacent but distinct areas should be distinguished from palliative psychiatry in a narrow sense: palliative care psychiatry and assisted dying for persons with SPMI. Palliative care psychiatry (Fairman et al., 2016) or psychiatry in palliative medicine (Chochinov and Breitbart, 2009) is the care for persons with mental disorders or psychiatric symptoms who are receiving palliative care for a life-threatening somatic illness. Thus, palliative care psychiatry is concerned with persons dying with psychiatric symptoms or mental disorders, while palliative psychiatry in a narrow sense is concerned with persons dying from mental disorders.

Regarding assisted dying, some have argued that SPMI can cause irremediable, unbearable suffering and that in these cases, a wish to die may be rational, competent and voluntary (Dembo et al., 2018). However, a defining characteristic of palliative care is that it ‘intends neither to hasten nor to postpone death’ and ‘affirms life’ (Radbruch et al., 2020: 8). As the practice of palliative psychiatry develops, assisted dying may come to be seen as at the end of the spectrum of approaches for the relief of suffering in persons with SPMI, or considered entirely separate. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss its potential merits and pitfalls further.

Palliative psychiatry in a broad sense

While palliative psychiatry in a narrow sense is limited to patients likely to die of their SPMI in the near future, palliative psychiatry in a broad sense refers to all approaches aiming at improving quality of life by means other than reduction of SPMI symptoms, namely harm reduction and relief of suffering. Palliative psychiatry in a broad sense is exemplified by supervised injectable heroin (SIH) treatment for refractory opioid use disorder. SIH treatment is intended for patients ‘who have not responded to standard treatments such as oral methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) or residential rehabilitation’ (Strang et al., 2015: 6), i.e., when curative treatments (aiming at abstinence or at least reduction of consumption) have not been successful. In SIH treatment, the goal of care is no longer reduction of heroin use per se, but reduction of use of street heroin with its associated harm,5 which improves quality of life (Palis et al., 2017; Strang et al., 2015). Of note, emerging evidence suggests that SIH treatment reduces the ultimate harm, mortality (Levengood et al., 2021; Strang et al., 2015). Together with the high intensity and high costs of SIH treatment, this illustrates that palliative psychiatry is far from ‘giving up’ hope and/or patients. It is about letting go of curative goals of care – if and when they are in all likelihood unattainable and their pursuit burdensome – and redirecting hope towards palliative goals of care, such as harm reduction and relief of suffering.

Another example for palliative psychiatry in a broad sense is the Community Outreach Partnership Program (COPP) for anorexia nervosa (Williams et al., 2010). In cases where treatments focusing on symptom reduction have failed, the authors propose ‘a shift away from focusing on the eating disorder and towards increasing quality of life, reducing distress and increasing hope for the future’ (Williams et al., 2010: 91; italics in the original). Interventions are tailored to the individual and can, e.g., consist of accompanying a fearful person to an art class she finds pleasurable. Of note, while describing their approach as an alternative to treatments aiming at symptom reduction, the authors themselves declare that ‘COPP does not provide palliative care’ (Williams et al., 2010: 93). However, the programme is based on ‘setting the eating disorder aside’ (Williams et al., 2010: 90), i.e., letting go of curative goals of care (reduction of eating disorder symptoms) that are in all likelihood unattainable. Instead, relief of suffering and improvement of quality of life are the main goals of care in COPP. Thus, COPP is a palliative psychiatry approach in the broad sense. We assume that the authors wished to express that their programme does not provide end-of-life care when they distanced themselves from palliative care. This would imply that they referred to what we termed ‘palliative psychiatry in a narrow sense’, exemplifying the need for concept clarification regarding non-curative approaches in psychiatry.

Similar, but different

As with palliative psychiatry in a narrow sense, we now offer some differentiations and clarifications for palliative psychiatry in a broad sense. First, approaches like SIH and COPP are often labelled harm reduction approaches (Bianchi et al., 2021; Kleinig, 2008). In COPP, harm may be reduced by not bingeing on raw meat or food from the rubbish bin (without necessarily reducing the frequency or duration of bingeing, i.e., without symptom reduction). The palliative elements in both SIH and COPP clearly include harm reduction. But ‘harm reduction by itself is insufficient to reduce suffering in [SPMI] patients and to attend to their associated physical, mental, social, and existential needs’ (Westermair et al., 2021: 60). Therefore, palliative psychiatry includes but goes beyond harm reduction, e.g., by ‘offering unconditional therapeutic support even to patients who choose to not engage in harm reduction’ (Westermair et al., 2021: 61).

Second, palliative psychiatry shares some characteristics with rehabilitative psychiatry and (personal) recovery, such as shifting the focus away from the disorder and setting individual, realistic goals that are valued by the patient. A mental health professional with experience in palliative (or rehabilitative) psychiatry is likely to be a good fit for a SPMI patient interested in recovery. However, in contrast to palliative psychiatry, the overarching goal in rehabilitative psychiatry is to help SPMI patients ‘develop the emotional, social and intellectual skills needed to live, learn and work in the community with the least amount of professional support’ (Roessler, 2006: 151). Thus, where palliative psychiatry focuses primarily on suffering and quality of life, rehabilitative psychiatry focuses on psychosocial functioning (see Figure 1). Regarding (personal) recovery, the main difference to palliative psychiatry is one of perspective and initiative: while palliative psychiatry is an approach that mental health professionals can propose to SPMI patients, recovery is a journey that persons undertake in order to live a personally fulfilling life in the face of SPMI. Mental health professionals can (and, in our opinion, should) support persons with SPMI in their pursuit of personal recovery, but cannot initiate it or take the lead. Also, both concepts can stand alone: persons with SPMI do not require a mental health professional to undertake their recovery journey, and mental health professionals can take a palliative approach to caring for SPMI patients that are currently not interested in recovery. And while some final recovery stages map onto palliative goals of care (such as ‘improving quality of life’), others map onto rehabilitative goals (such as ‘successful occupational performance’) or do not map onto any of the traditional goals of medicine, namely prevention, curation, rehabilitation and palliation (such as ‘personal growth’; Leamy et al., 2011).

Third, palliative psychiatry is ‘defined by its goals and not by the use of specific treatments’ (Strand et al., 2020: 6). Most interventions used in palliative psychiatry are already established in psychiatry and frequently used with the goal of symptom reduction, i.e., with curative intent. For example, building a therapeutic relationship with a person with anorexia nervosa can both be a means to working on core symptoms such as restrictive eating (i.e. an intervention with curative intent) and a means to alleviating existential loneliness (Yager, 2020; that is, an intervention with palliative intent). Thus, palliative psychiatry differs from curative psychiatry mainly in when and for what purpose interventions are applied. In fact, palliative psychiatry may be most clearly distinguished from curative psychiatry by acts of omission (such as not coercing artificial refeeding, not terminating psychotherapy in a patient whose SPMI does not improve) than by acts of commission.

Fourth, and most importantly, palliative psychiatry in a broad sense can – and often should – be integrated with curative and rehabilitative approaches to provide optimal care, as is the gold standard in palliative care for somatic illnesses (Radbruch et al., 2020). For example, in the COPP programme for eating disorders detailed above, interventions aiming at symptom reduction (such as keeping food records and meal planning) and psychosocial functioning (general life skills such as budgeting and social skills such as conflict resolution) are used in parallel with treatment focusing directly on distress and quality of life (Williams et al., 2010). Another example might be prescribing benzodiazepines to relieve anxiety induced by therapy-refractory delusions (palliative intent) while switching to an antipsychotic combination treatment to try and reduce the delusions (curative intent) and initiating supported employment to train cognitive and self-management abilities (rehabilitative intent). Importantly, such a combination of palliative, rehabilitative and curative aspects of care is never fixed but should be constantly adapted to current psychopathology, psychosocial functioning, risk and severity of harm, and patients’ wishes. Shifts from more palliative approaches back to more curative approaches are likely to be more common in SPMI than in somatic illnesses due to differences in disorder trajectories and life expectancy. In addition, as interventions in mental health care tend to be pleiotropic, even if interventions are ‘only’ intended to relief suffering, they might still result in symptom reduction and/or improved psychosocial functioning. For example, a referral to a palliative care unit can, unexpectedly, help a person with anorexia nervosa realize that she does prefer eating over dying after all (Mishra, 2012).

Conclusion

Palliative psychiatry is an emerging subdiscipline of psychiatry, born out of compassion for SPMI patients and humility considering the limitedness of curative psychiatry in alleviating their suffering. In a broad sense, palliative psychiatry refers to any approach aiming at reducing harm and/or relieving suffering directly rather than via reduction of SPMI symptoms (curative psychiatry) or improvement of psychosocial functioning (rehabilitative psychiatry). In a narrow sense, palliative psychiatry refers to such approaches in patients likely to die of their SPMI in the near future.

As with somatic illnesses, palliative approaches are neither first-line nor second-line treatments. If curative treatment options have a reasonable benefit–harm ratio, they should be preferred in general. However, in some cases of SPMI, further treatment attempts aiming at symptom reduction will – in all likelihood – be ineffective and burdensome. In these cases, palliative psychiatry may be the best possible form of management, distinct from but integratable with other approaches such as curative and rehabilitative psychiatry and (personal) recovery.

The implementation of palliative psychiatry is met with several challenges, among them the stigmatization of palliative care in general, difficulties regarding decision-making capacity and prognostication in SPMI, and lack of established staging models for SPMI. We firmly believe that these challenges are worth overcoming so that mental health care can be improved and completed, just as cancer care was improved and completed by the emergence of palliative care.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ulrich Schweiger, MD (University of Lubeck, Germany) and Sascha Weber, MD (University of Aachen, Germany) for their feedback provided on an earlier draft of this manuscript. No compensation was provided.

Given the largely syndromal nature of diagnostication in psychiatry, a severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI) is largely defined by the presence of SPMI symptoms. Thus, if the symptoms that are diagnostic criteria for a SPMI are irremediable, so is the SPMI. We therefore do not differentiate between irremediability of SPMI symptoms and SPMI themselves in this article. Of note, irremediability of SPMI (symptoms) does not necessarily entail irremediability of the associated suffering.

In a narrow sense, curation in psychiatry means stable and complete symptom remission without need for further treatment. This can be achieved, e.g., in arachnophobia by exposure therapy. However, most approaches in psychiatry are symptomatic rather than causal as they relieve symptoms but do not, e.g., change the risk of recurrence after treatment has ended (such as anti-depressants in recurrent depressive disorder). Also, in many cases, only partial symptom remission is achieved. As all these approaches are characterized by a focus on the mental disorder and the intention to treat it, we group them under curation in psychiatry in a broad sense and use the term in this sense in the text.

Whether palliative care for dementia (including behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia) should be subsumed under palliative psychiatry hinges on the controversial question whether it constitutes a mental disorder, a neurological disease or whether the two categories should be collapsed into ‘disorders of the nervous system’ (Crossley et al., 2015; Gaebel et al., 2019; White et al., 2012). Resolving this nosological uncertainty seems out of the scope of this article, whose main thesis is that palliative approaches to care can be appropriate even in the absence of a proven progressive histopathological process.

Adapting Yager (2020), we define suffering as the felt quality of unfulfilled basic needs threatening the existence or integrity of the person. It is salient, intense and persistent, typically has an existential dimension but is meaningless itself. In SPMI, suffering can stem from SPMI symptoms, the associated impairment in psychosocial functioning and the biological, psychological, social and economic consequences of SPMI.

By harm we mean negative consequences of the SPMI, i.e., setbacks to the affected person’s interests (Beauchamp and Childress, 2019). Once manifested, harm persists independently of the SPMI. Harm can be biological (e.g. infections from needle sharing), psychological/mental (e.g. traumatisation from being sexually assaulted in an intoxicated and thus incapacitated state), social (e.g. damage to relationships through drug-related crime) or economic (e.g. loss of income; EMCDDA, 2010).

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Anna L Westermair  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3673-4589

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3673-4589

Daniel Z Buchman  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8944-6647

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8944-6647

Manuel Trachsel  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2697-3631

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2697-3631

References

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. (2019) Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Berk L, Udina M, et al. (2012) Palliative models of care for later stages of mental disorder: Maximizing recovery, maintaining hope, and building morale. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 46: 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi A, Stanley K, Sutandar K. (2021) The ethical defensibility of harm reduction and eating disorders. The American Journal of Bioethics 21: 46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov HM, Breitbart W. (2009) Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Solmi M, Veronese N, et al. (2017) Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: A large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry 16: 163–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley NA, Scott J, Ellison-Wright I, et al. (2015) Neuroimaging distinction between neurological and psychiatric disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry 207: 429–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembo J, Schuklenk U, Reggler J. (2018) ‘For their own good’: A response to popular arguments against permitting Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) where mental illness is the sole underlying condition. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry / Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie 63: 451–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann Y, Golla H, Schmidt H, et al. (2020) Palliative care in advanced dementia. Frontiers in Psychiatry 11: 699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMCDDA (ed.) (2010) Harm Reduction: Evidence, Impacts and Challenges. Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Fairman N, Hirst JM, Irwin SA. (2016) Clinical Manual of Palliative Care Psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. (2017) Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology 35: 96–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaebel W, Reed GM, Jakob R. (2019) Neurocognitive disorders in ICD-11: A new proposal and its outcome. World Psychiatry 18: 232–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieselmann A, Vollmann J. (2020) Ein Palliativkonzept für die Psychiatrie? Konzeptionelle Überlegungen zu Vorteilen und Grenzen einer engeren Zusammenarbeit von ‘palliative care’ und Psychiatrie. Der Nervenarzt 91: 385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Jacelon CS, Marquard JL. (2012) An evolutionary concept analysis of palliative care. Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine 2: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K, Aapro M, Kaasa S, et al. (2018) European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) position paper on supportive and palliative care. Annals of Oncology 29: 36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RS, van Winter Rossum I, Leucht S, et al. (2018) Amisulpride and olanzapine followed by open-label treatment with clozapine in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder (OPTiMiSE): A three-phase switching study. The Lancet Psychiatry 5: 797–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AS. (2014) Defining ‘serious illness’. Journal of Palliative Medicine 17: 985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinig J. (2008) The ethics of harm reduction. Substance Use & Misuse 43: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, et al. (2011) Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British Journal of Psychiatry 199: 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levengood TW, Yoon GH, Davoust MJ, et al. (2021) Supervised injection facilities as harm reduction: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 61: 738–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt S, Buchman DZ. (2021) Applying futility in psychiatry: A concept whose time has come. Journal of Medical Ethics 47: e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblad A, Helgesson G, Sjöstrand M. (2019) Towards a palliative care approach in psychiatry: Do we need a new definition? Journal of Medical Ethics 45: 26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A, Yager J, Feinstein RE. (2010) Medical futility and psychiatry: Palliative care and hospice care as a last resort in the treatment of refractory anorexia nervosa. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 43: 372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghani SH. (2004) A concept analysis of palliative care in the United States. Journal of Advanced Nursing 46: 152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra R. (2012) What actually happened. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 21: 408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill J, Crowther T, Sampson G. (1994) Anorexia nervosa: Palliative care of terminal psychiatric disease. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 11: 36–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palis H, Marchand K, Guh D, et al. (2017) Men’s and women’s response to treatment and perceptions of outcomes in a randomized controlled trial of injectable opioid assisted treatment for severe opioid use disorder. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 12: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radbruch L, de Lima L, Knaul F, et al. (2020) Redefining palliative care – A new consensus-based definition. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 60: P754–P764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roessler W. (2006) Psychiatric rehabilitation today: An overview. World Psychiatry 5: 151–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Warden D, Wisniewski SR, et al. (2009) STAR* D. CNS Drugs 23: 627–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, et al. (2002) Palliative care: The World Health Organization’s global perspective. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 24: 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll J, Mathew A, Venkateswaran C, et al. (2022) Palliative care for patients with severe and persistent mental illness: A survey study of the attitudes of psychiatrists in India compared to psychiatrists in Switzerland. Frontiers in Psychiatry 13: 858699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand M, Sjöstrand M, Lindblad A. (2020) A palliative care approach in psychiatry: Clinical implications. BMC Medical Ethics 21: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang J, Groshkova T, Uchtenhagen A, et al. (2015) Heroin on trial: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials of diamorphine-prescribing as treatment for refractory heroin addiction. The British Journal of Psychiatry 207: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachsel M, Hodel M, Irwin SA, et al. (2019) Acceptability of palliative care approaches for patients with severe and persistent mental illness: A survey of psychiatrists in Switzerland. BMC Psychiatry 19: 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachsel M, Irwin SA, Biller-Andorno N, et al. (2016) Palliative psychiatry for severe persistent mental illness as a new approach to psychiatry? Definition, scope, benefits, and risks. BMC Psychiatry 16: 260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachsel M, Johnsen C, Elgudin J. (2022) Palliative Psychiatry: A New Field for Treatment-Resistant Mental Illness. Presentation held at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Trachsel M, Wild V, Biller-Andorno N, et al. (2015) Compulsory treatment in chronic anorexia nervosa by all means? Searching for a middle ground between a curative and a palliative approach. The American Journal of Bioethics 15: 55–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trauer T. (2012) Palliative models of care for later stages of mental disorder: Maximising recovery, maintaining hope and building morale. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 46: 170–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi JK, Tripathi A, Dhanasekaran S, et al. (2014) Preventive psychiatry: Concept appraisal and future directions. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 60: 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermair AL, Buchman DZ, Levitt S, et al. (2021) Palliative psychiatry for severe and enduring anorexia nervosa includes but goes beyond harm reduction. The American Journal of Bioethics 21: 60–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PD, Rickards H, Zeman AZJ. (2012) Time to end the distinction between mental and neurological illnesses. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 344: e3454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Dobney T, Geller J. (2010) Setting the eating disorder aside: An alternative model of care. European Eating Disorders Review 18: 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager J. (2020) Managing patients with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: When is enough, enough? The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 208: 277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumstein N, Riese F. (2020) Defining severe and persistent mental illness – A pragmatic utility concept analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry 11: 648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]