This study assesses the association between youth suicide rates and mental health professional workforce shortages at the county level.

Key Points

Question

Are youth suicide rates associated with county mental health professional workforce shortages, after adjusting for county demographic and socioeconomic characteristics?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 5034 US youth 5 to 19 years who died by suicide from 2015 to 2016, the suicide rate increased as county levels of mental health professional shortages increased, after adjusting for county demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

Meaning

The findings suggest mental health professional workforce shortages at the county level are associated with youth suicides, which have implications for suicide prevention efforts.

Abstract

Importance

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among US adolescents. Workforce shortages of mental health professionals in the US are widespread, but the association between mental health workforce shortages and youth suicides is not well understood.

Objective

To assess the association between youth suicide rates and mental health professional workforce shortages at the county level, adjusting for county demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cross-sectional study included all US counties and used data of all US youlth suicides from January 2015, through December 31, 2016. Data were analyzed from July 1, 2021, through December 20, 2021.

Exposures

County health-professional shortage area designation for mental health, assigned by the US Health Resources and Services Administration based on mental health professionals relative to the population, level of need for mental health services, and service availability in contiguous areas. Designated shortage areas receive a score from 0 to 25, with higher scores indicating greater workforce shortages.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Suicides by youth aged 5 to 19 years from 2015 to 2016 were identified from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Compressed Mortality File. A multivariable negative binomial regression model was used to analyze the association between youth suicide rates and mental health workforce shortage designation, adjusting for the presence of a children’s mental health hospital and county-level markers of health insurance coverage, education, unemployment, income, poverty, urbanicity, racial and ethnic composition, and year. Similar models were performed for the subgroups of (1) firearm suicides and (2) counties assigned a numeric shortage score.

Results

During the study period, there were 5034 youth suicides (72.8% male and 68.2% non-Hispanic White) with an annual suicide rate of 3.99 per 100 000 youths. Of 3133 US counties, 2117 (67.6%) were designated as mental health workforce shortage areas. After adjusting for county characteristics, mental health workforce shortage designation was associated with an increased youth suicide rate (adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR], 1.16; 95% CI, 1.07-1.26) and an increased youth firearm suicide rate (aIRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.13-1.42). For counties with an assigned numeric workforce shortage score, the adjusted youth suicide rate increased 4% for every 1-point increase in the score (aIRR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.06).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study, US county mental health professional workforce shortages were associated with increased youth suicide rates. These findings may inform suicide prevention efforts.

Introduction

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among US adolescents, with rates rising over the last decade.1 Disparities exist by area geography, with higher suicide rates in rural areas and high-poverty areas.2,3,4 Mental health workforce shortages in the US are widespread, with most counties having few or no practicing child psychiatrists and limited numbers of child-serving mental health professionals.5 Both rural counties and high-poverty counties are also more likely to have an inadequate supply of mental health professionals,6,7,8 but little is known about the association of youth suicides with mental health workforce shortages. If a causal association exists, strategies to ameliorate and identify the root causes of mental health workforce shortages would be considered in comprehensive community-based suicide prevention programs.

The US federal government designates Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) to distribute targeted resources to geographic areas with health care workforce shortages in primary care, dental care, and mental health.9 HPSA workforce-shortage designation is used to determine eligibility for more than 30 federal and state incentive programs and enhanced US Centers for Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement rates.10 Thus, mental health HPSA designation is a policy-relevant marker for mental health workforce shortages.

The objective of our study was to assess the association of youth suicides and mental health workforce shortages measured by mental health HPSA designation at the county level in the US. We hypothesized that youth suicide rates would be higher in counties with mental health workforce shortages, after adjusting for county socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Since firearm suicides are less likely to be preceded by a known mental health diagnosis,11 we hypothesized that county mental health workforce shortages would not be associated with youth firearm suicide rates.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study of all US youth suicides from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2016, linked to county-level mental health workforce shortage data. Youth suicide data were obtained from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Compressed Mortality File (CMF), an administrative database of death certificate data.12 The most recently released year of CMF data is 2016. County mental health workforce shortage data were obtained from publicly available HPSA data files from the US Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA).13 County demographic and socioeconomic characteristics were obtained from publicly available Area Health Resource Files (AHRF), maintained by HRSA, which integrate data from multiple sources, including the American Hospital Association, American Medical Association, and US Census Bureau.14

We included counties from the 50 US states and Washington, DC, and excluded US territories. We excluded largely unpopulated counties (with fewer than 100 children 5 to 19 years) and counties with missing data for the outcome, mental health professional workforce shortages, or covariates. Data analysis was performed from July 1, 2021, to December 20, 2021. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.15 This study was deemed exempt by the Lurie Children’s Hospital institutional review board.

Study Measures

The study outcome was suicide deaths among youths 5 to 19 years from 2015 to 2016, identified in the CMF by International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes U03, X60 through X84, and Y87.0.12,16 Demographics of youth who died by suicide were categorized by age group (5 to 9 years, 10 to 14 years, and 15 to 19 years), sex (male or female), and race and ethnicity (Hispanic, Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, Non-Hispanic Asian and Pacific Islander, Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic White) as listed on the death certificate. Race and ethnicity were examined through a health equity lens, treating both as social constructs rather than biologic determinants.17 Firearm suicides were identified using ICD-10 codes X72 through X74.16 County population estimates of youth 5 to 19 years from the AHRF (derived from the 2010 US Census data) were used to determine suicide rates.

The main exposure variable, mental health professional workforce shortages, was defined by county designation as a mental health HPSA in the AHRF in 2015 and 2016.14 HRSA defines counties as HPSAs based on the number of mental health professionals and psychiatrists relative to the overall population, the area’s level of need for mental health services, and the availability of services in contiguous areas.14 Each county is categorically designated as a whole-county HPSA, partial-county HPSA, or not an HPSA. Partial-county HPSA means that 1 or more geographic areas, specific populations, or facilities within the county have designated shortage status. Similar to prior literature, we created a dichotomous variable to compare whole-county HPSA designation with partial/no HPSA designation.18,19 Counties with whole-county HPSA designation are assigned a mental health HPSA score from 0 to 25, based on mental health professional density and markers of need for mental health services, with higher scores indicating higher workforce shortages levels (eTable 1 in the Supplement).9

Covariates were selected from the AHRF based on prior literature3,4,11,20 using the Behavioral-Ecological Model of Healthcare Access and Navigation as a conceptual framework.21,22 This framework highlights how environmental factors (the health care environment, social environment, and neighborhood demographics) influence access to health services and health outcomes, such as youth suicide. As measures of the health care environment, we included whether the county had a children’s mental health short-term hospital (from the 2017 American Hospital Association Survey) and the percentage of children without health insurance in 2015 and 2016. As measures of the social environment, we used the percentage of individuals 25 years or older with a high school diploma from 2013 to 2017, the percentage of individuals 16 years or older who were unemployed in 2015 and 2016, median household income in 2015 and 2016, and the percentage of individuals below the federal poverty level in 2015 and 2016. To measure neighborhood demographics, we included county racial and ethnic composition (percentage Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White) from the 2010 US Census and county rural-urban status (metropolitan, rural adjacent to a metropolitan county, rural remote) defined using 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum codes.23,24

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the annual suicide rate per 100 000 youth aged 5 to 19 years old. We used descriptive statistics to summarize decedent demographics by age, sex, and race and ethnicity. We summarized county demographic and socioeconomic characteristics by mental health HPSA designation (whole vs partial/none) in 2015 and 2016. We calculated youth suicide rates by county mental health HPSA designation, mental health HPSA score quartile (for counties with an assigned score), and by county demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. For county characteristics that varied from 2015 to 2016, we used 2015 characteristics to assign county categorization. We estimated unadjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs) to compare youth suicide rates by county characteristics.

We determined the association between youth suicide rates and county mental health professional workforce shortages (as indicated by mental health HPSA designation), adjusting for county demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. For our main model (model 1), we used negative binomial regression with county as the unit of analysis and youth suicide counts by county as the outcome. Negative binomial regression was chosen due to overdispersion of the outcome of youth suicides. Variables included county mental health HPSA designation, presence of a children’s mental health short-term hospital, percentage of children without health insurance, county socioeconomic characteristics (percentage of individuals 25 years or older with a high school diploma, percentage of individuals 16 years or older who were unemployed, median household income, and percentage of individuals below the poverty level), percentage of the county population that was Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White, county rural-urban status, and year. We included year-specific county characteristics for variables that varied by year. The county population count of youth aged 5 to 19 years was used as the offset to estimate suicide rates. We constructed model 2 similarly, using youth firearm suicides as the outcome instead of total youth suicides.

Model 3 assessed the subset of US counties that had an assigned numeric HPSA score, replacing the categorical measure of mental health workforce shortages (HPSA designation) with the HPSA score. We included the same covariates, except for the presence of a children’s mental health hospital because few counties with an assigned HPSA score had such a hospital.

Prespecified sensitivity analyses were conducted to confirm the robustness of the results. For our first sensitivity analysis, we replaced the primary measure of mental health workforce shortages (HPSA designation) with an alternate workforce measure, the number of practicing child psychiatrists in the county (0, 1 to 5, 6 to 60, or more than 60) from the AHRF, sourced from the 2015 American Medical Association Physician Master File (model 4). For our second sensitivity analysis, we included alternate measures of county socioeconomic characteristics defined using US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service county typology codes (low education, low employment, persistent poverty, persistent childhood poverty; definitions available in eTable 2 in the Supplement) (model 5).25 For each model, we assessed collinearity of variables, with a variance inflation factor of more than 10 considered evidence of collinearity. None of the variables exceeded this cutoff. Analyses were performed using Stata version 16.0 (Stata Corp), including use of the maptile Stata program.26

Results

From 2015 to 2016, there were 5034 youth suicides, with 3665 suicides by males (72.8%) and 1369 by females (27.2%). There were 3435 suicides by non-Hispanic White youth (68.2%), 732 suicides by Hispanic youth (14.5%), 487 suicides by non-Hispanic Black youth (9.7%), 222 by non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander youth (4.4%), 148 by non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native youth (2.9%), and 10 by youth of unknown ethnicity (0.2%). The annual suicide rate was 3.99 per 100 000 youth.

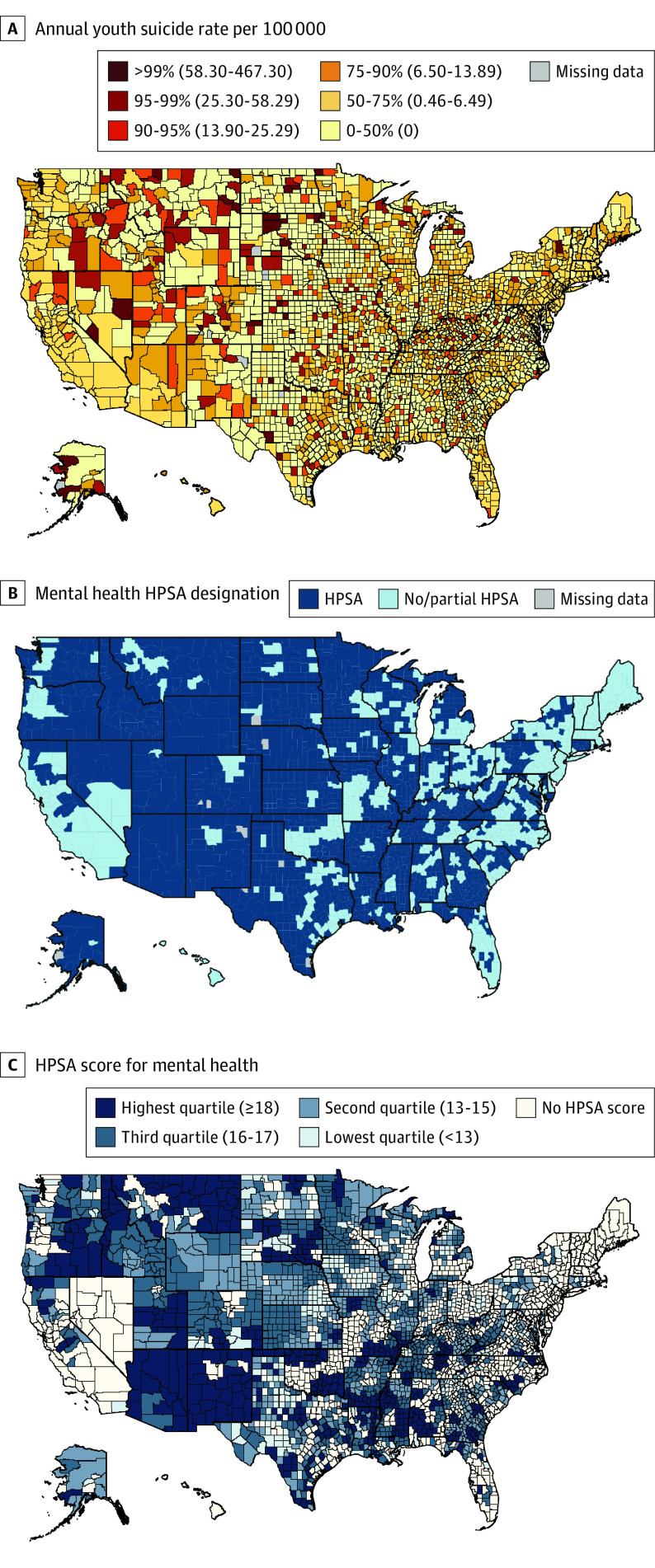

Of the 3150 US counties, we excluded 16 with fewer than 100 children aged 5 to 19 years and we excluded 1 due to missing data. Among the 3133 remaining counties, 2117 counties (67.6%) had mental health HPSA designation and 1016 counties (32.4%) had partial/no mental health HPSA designation (Figure 1). From 2015 to 2016, HPSA designation changed for 14 counties: 7 were newly designated and 7 had HPSA designation removed. There were 2106 US counties with an HPSA score assigned. More counties with mental health HPSA designation had no practicing child psychiatrists, compared with counties with partial/no HPSA designation (87.9% vs 47.2% in 2015). Only 1 county (0.1%) with mental health HPSA designation had a children’s mental health short-term hospital. Counties with mental health HPSA designation had more uninsured children, lower educational attainment, higher unemployment, higher poverty, higher percentages of non-Hispanic White residents, and were more often rural, compared with counties with partial/no HPSA designation (Table 1).

Figure 1. US County Maps of the Annual Youth Suicide Rate and Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) for Mental Health, 2015 to 2016.

A, County-level annual suicide rate per 100 000 youth 5 to 19 years old from 2015 to 2016. Color gradation cut points represent the 50th, 75th, 90th, 95th, and 99th percentile of the distribution of annual youth suicide rates by county. B, County HPSA designation for mental health. C, Mean county HPSA score for mental health from 2015 to 2016. HPSA scores range from 0 to 25; higher scores indicate higher degrees of mental health professional workforce shortages. Color gradation cut points represent score quartiles among counties assigned an HPSA score.

Table 1. Characteristics of US Counties With and Without Mental Health Professional Shortage Area Designation, 2015-2016.

| Year | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US counties | Counties with mental health HPSA designation | Counties with no or partial mental health HPSA designation | ||||

| 2015 (n = 3133) | 2016 (n = 3133) | 2015 (n = 2117) | 2016 (n = 2117)a | 2015 (n = 1016) | 2016 (n = 1016)a | |

| County characteristic | ||||||

| Child psychiatrists | ||||||

| 0 | 2341 (74.7) | 2341 (74.7) | 1861 (87.9) | 1860 (87.9) | 480 (47.2) | 481 (47.3) |

| 1-5 | 532 (17.0) | 532 (17.0) | 240 (11.3) | 240 (11.3) | 292 (28.7) | 292 (28.7) |

| 6-60 | 233 (7.4) | 233 (7.4) | 13 (0.6) | 14 (0.7) | 220 (21.7) | 219 (21.6) |

| >60 | 27 (0.9) | 27 (0.9) | 3 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 24 (2.4) | 24 (2.4) |

| Presence of a children’s mental health hospital | 24 (0.8) | 24 (0.8) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 23 (2.3) | 23 (2.3) |

| Uninsured children, quartile, %b | ||||||

| Lowest (<3.9) | 669 (21.4) | 992 (29.4) | 324 (15.3) | 507 (24.0) | 345 (34.0) | 415 (40.9) |

| Second (3.9-5.2) | 758 (24.2) | 776 (24.5) | 494 (23.3) | 502 (23.7) | 264 (26.0) | 264 (26.0) |

| Third (5.3-7.6) | 788 (25.2) | 773 (24.7) | 549 (25.9) | 550 (26.0) | 239 (23.5) | 223 (22.0) |

| Highest (≥7.7) | 918 (29.3) | 672 (21.5) | 750 (35.4) | 558 (26.4) | 168 (16.5) | 114 (11.2) |

| ERS county typology codesc | ||||||

| Low education | 466 (14.9) | 466 (14.9) | 396 (18.7) | 395 (18.7) | 70 (6.9) | 71 (7.0) |

| Low employment | 905 (28.9) | 905 (28.9) | 717 (33.9) | 714 (33.7) | 188 (18.5) | 191 (18.8) |

| Persistent poverty | 353 (11.3) | 353 (11.3) | 305 (14.4) | 305 (14.4) | 48 (4.7) | 48 (4.7) |

| Persistent childhood poverty | 708 (22.6) | 708 (22.6) | 571 (27.0) | 569 (26.9) | 137 (13.5) | 139 (13.7) |

| Ethnicity,d quartile, %b | ||||||

| Hispanic | ||||||

| Lowest (0-1.6) | 747 (23.8) | 747 (23.8) | 563 (26.6) | 564 (26.6) | 184 (18.1) | 183 (18.0) |

| Second (1.6-3.3) | 812 (25.9) | 812 (25.9) | 578 (27.3) | 577 (27.3) | 234 (23.0) | 234 (23.0) |

| Third (3.3-8.1) | 782 (25.0 | 782 (25.0 | 470 (22.2) | 468 (22.1) | 312 (30.7) | 315 (31.0) |

| Highest (8.1-95.7)) | 792 (25.3) | 792 (25.3) | 506 (23.9) | 508 (24.0) | 286 (28.2) | 284 (28.0) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | ||||||

| Lowest (0-0.4%) | 682 (21.8) | 682 (21.8) | 610 (28.8) | 611 (28.9) | 72 (7.1) | 71 (7.0) |

| Second (0.4-1.9) | 870 (27.8) | 870 (27.8) | 615 (29.1) | 618 (29.2) | 255 (25.1) | 252 (24.8) |

| Third (1.9-9.8) | 797 (25.4) | 797 (25.4) | 421 (19.9) | 421 (19.9) | 376 (37.0) | 376 (37.0) |

| Highest (9.8-85.4) | 784 (25.0) | 784 (25.0) | 471 (22.3) | 467 (22.1) | 313 (30.8) | 317 (31.2) |

| Non-Hispanic White | ||||||

| Lowest (0-67) | 783 (25.0) | 783 (25.0) | 504 (23.8) | 503 (23.8) | 279 (27.5) | 280 (27.6) |

| Second (67-85.8) | 778 (24.8) | 778 (24.8) | 481 (22.7) | 479 (22.6) | 297 (29.2) | 299 (29.4) |

| Third (85.8-94.2) | 787 (25.1) | 787 (25.1) | 525 (24.8) | 526 (25.9) | 262 (25.8) | 261 (25.7) |

| Highest (94.2-100) | 785 (25.1) | 785 (25.1) | 607 (28.7) | 609 (28.8) | 178 (17.5) | 176 (17.3) |

| Rural-urban status | ||||||

| Metropolitan | 1165 (37.2) | 1165 (37.2) | 461 (21.8) | 459 (21.7) | 704 (69.3) | 706 (69.5) |

| Rural adjacent to a metropolitan county | 1027 (32.8) | 1027 (32.8) | 796 (37.6) | 797 (37.7) | 231 (22.7) | 230 (22.6) |

| Rural remote | 941 (30.0) | 941 (30.0) | 860 (40.6) | 861 (40.7) | 81 (8.0) | 80 (7.9) |

Abbreviations: ERS, Economic Research Service; HPSA, Health Professional Shortage Area.

HPSA categorization changed for 14 counties from 2015 to 2016. Seven counties changed from HPSA to no/partial HPSA and 7 counties from no/partial HPSA to HPSA.

Quartiles defined using mean county characteristics from 2015 and 2016.

Definitions of ERS county typology codes are listed in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Race and ethnicity were categorized as listed on the death certificate.

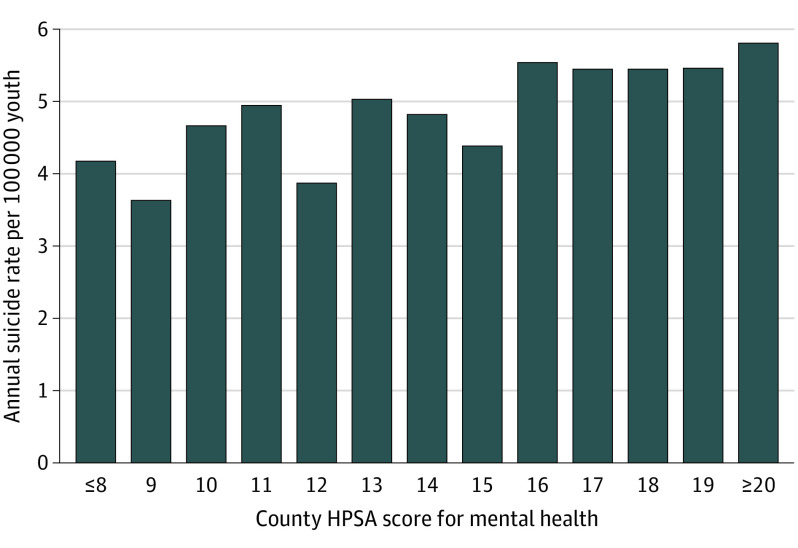

The unadjusted annual suicide rate in counties with mental health HPSA designation was 5.09 per 100 000 youth, compared with 3.62 per 100 000 youth in counties with partial/no HPSA designation (IRR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.33-1.49). The unadjusted annual suicide rate in counties with the highest quartile of mental health workforce shortages (HPSA score of 18 or more) was 5.49 per 100 000 youth compared with 4.22 per 100 000 youth in counties with the lowest quartile of workforce shortages (HPSA score less than 13) (IRR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.10-1.53). Unadjusted youth suicide rates decreased as the number of practicing child psychiatrists increased and youth suicide rates were lower in counties with a children’s mental health hospital. Unadjusted youth suicide rates were higher in counties with higher rates of uninsured children and in rural areas compared with metropolitan areas (Table 2). Figure 2 displays the annual suicide rate per 100 000 youth by county mental health HPSA score.

Table 2. Unadjusted Youth Suicide Rates by US County Characteristics.

| County characteristica | Youth suicides (2015-2016) | Mean national population, 5-19 y (2015-2016) | Annual suicide rate per 100 000 youth | IRR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health HPSA designation | ||||

| Partial/no county | 3414 | 47 165 279 | 3.62 | 1 [Reference] |

| Whole county | 1620 | 15 899 231 | 5.09 | 1.41 (1.33-1.49) |

| Mental health HPSA score, quartileb | ||||

| Lowest (<13) | 268 | 3 171 683 | 4.22 | 1 [Reference] |

| Second (13-15) | 406 | 4 306 050 | 4.71 | 1.12 (0.95-1.31) |

| Third (16-17) | 582 | 5 285 928 | 5.51 | 1.30 (1.13-1.51) |

| Highest (≥18) | 339 | 3 085 947 | 5.49 | 1.30 (1.10-1.53) |

| Child psychiatrists | ||||

| 0 | 1303 | 12 996 907 | 5.01 | 1 [Reference] |

| 1-5 | 1319 | 13 588 425 | 4.85 | 0.97 (0.90-1.05) |

| 6-60 | 1813 | 24 637 056 | 3.68 | 0.73 (0.68-0.79) |

| >60 | 599 | 11 842 122 | 2.53 | 0.50 (0.46-0.56) |

| Children’s mental health hospital | ||||

| Absent | 4830 | 59 844 749 | 4.04 | 1 [Reference] |

| Present | 204 | 3 219 761 | 3.17 | 0.79 (0.68-0.90) |

| Uninsured children, quartilec | ||||

| Lowest (<3.9%) | 1950 | 27 545 205 | 3.54 | 1 [Reference] |

| Second (3.9%-5.2%) | 1107 | 14 695 637 | 3.77 | 1.06 (0.99-1.15) |

| Third (5.3%-7.6%) | 1041 | 10 515 070 | 4.95 | 1.40 (1.30-1.51) |

| Highest (≥7.7%) | 936 | 10 308 598 | 4.54 | 1.28 (1.19-1.39) |

| Low education county typed | ||||

| No | 4521 | 54 000 848 | 4.19 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 513 | 9 063 662 | 2.83 | 0.68 (0.62-0.74) |

| Low employment county typed | ||||

| No | 4452 | 56 407 411 | 3.95 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 582 | 6 657 099 | 4.37 | 1.11 (1.01-1.21) |

| Persistent poverty county typed | ||||

| No | 4786 | 59 381 679 | 4.03 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 248 | 3 682 831 | 3.37 | 0.84 (0.73-0.95) |

| Persistent childhood poverty county typed | ||||

| No | 4411 | 54 298 128 | 4.06 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 623 | 8 766 382 | 3.55 | 0.87 (0.80-0.95) |

| Rural-urban status | ||||

| Metropolitan | 4077 | 53 880 704 | 3.78 | 1 [Reference] |

| Rural adjacent to a metropolitan county | 563 | 6 064 085 | 4.64 | 1.23 (1.12-1.34) |

| Rural remote | 394 | 3 119 721 | 6.31 | 1.67 (1.50-1.85) |

Abbreviations: IRR, incidence rate ratio; HPSA, Health Professional Shortage Area.

For county characteristics that varied between 2015 and 2016, categorization of the county was based on 2015 characteristics.

Among 2106 US counties with an HPSA score assigned. Quartiles were defined using mean HPSA scores from 2015 and 2016.

Quartiles were defined using mean uninsured rates from 2015 and 2016.

Definitions of Economic Research Service county typology codes are listed in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Figure 2. Annual Youth Suicide Rate by County Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) Score for Mental Health, 2015 to 2016.

Aggregate annual youth suicide rates were calculated by determining the annual number of youth suicides among counties with a specific mental health HPSA score and dividing by the youth population in counties with that HPSA score.

After adjusting for county socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, youth suicide rates were 1.16 times higher (adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR], 1.16; 95% CI, 1.07-1.26) in counties with mental health HPSA designation compared with counties with partial/no mental health HPSA designation (model 1; Table 3). In this model, the adjusted youth suicide rate increased as the proportion of uninsured children increased and as the percentage of individuals 25 years or older with a high school diploma increased. The adjusted youth suicide rate decreased as median household income increased. The adjusted youth suicide rate was lower in rural counties adjacent to metropolitan counties compared with metropolitan counties.

Table 3. Negative Binomial Regression Models Estimating the Association of Youth Suicide Rates and County Mental Health Professional Workforce Shortages.

| Characteristic | aIRR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: all youth suicides as outcome | Model 2: firearm youth suicides as outcome | Model 3: continuous HPSA score as variable | Model 4: child psychiatrists as primary variable | Model 5: categorical socioeconomic variables | |

| Mental health HPSA designation | 1.16 (1.07-1.26)a | 1.27 (1.13-1.42)a | NA | NA | 1.17 (1.08-1.28)a |

| Mental health HPSA score | NA | NA | 1.04 (1.02-1.06)a | NA | NA |

| Child psychiatrists | |||||

| 0 | NA | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 1-5 | NA | NA | NA | 0.98 (0.89-1.08) | NA |

| 6-60 | NA | NA | NA | 0.81 (0.72-0.91)a | NA |

| >60 | NA | NA | NA | 0.62 (0.52-0.74)a | NA |

| Presence of children’s mental health hospital | 0.97 (0.79-1.18) | 1.04 (0.80-1.35) | NA | 1.04 (0.85-1.26) | 1.00 (0.81-1.23) |

| Uninsured children, % | 1.05 (1.04-1.07)a | 1.09 (1.07-1.11)a | 1.03 (1.00-1.05)b | 1.05 (1.03-1.06)a | 1.05 (1.03-1.06)a |

| Socioeconomic markers | |||||

| Individuals ≥25 y with a high school diploma, % | 1.04 (1.03-1.05)a | 1.03 (1.01-1.05)a | 1.03 (1.02-1.05)a | 1.04 (1.03-1.05)a | NA |

| Unemployment among individuals ≥16 y, % | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | 1.04 (1.00-1.08)b | 1.01 (0.97-1.04) | 1.01 (0.98-1.04) | NA |

| Median household income (in $10 000s) | 0.93 (0.89-0.97)c | 0.82 (0.76-0.88)a | 1.04 (0.94-1.14) | 0.95 (0.91-0.99)b | NA |

| Individuals below the poverty level, % | 1.01 (0.99-1.02) | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | 1.02 (1.00-1.04) | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | NA |

| County typology codesd | |||||

| Low education | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.82 (0.71-0.96)b |

| Low employment | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.05 (0.93-1.17) |

| Persistent poverty | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.08 (0.90-1.30) |

| Persistent childhood poverty | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.02 (0.90-1.17) |

| Race and ethnicity, %e | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.98 (0.98-0.99)a | 0.99 (0.98-1.00)c | 0.98 (0.98-0.99)a | 0.98 (0.98-0.99)a | 0.98 (0.97-0.98)a |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.97 (0.97-0.98)a | 0.99 (0.98-1.00)b | 0.97 (0.96-0.98)a | 0.98 (0.97-0.98)a | 0.97 (0.97-0.98)a |

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.99 (0.98-0.99)a | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 0.99 (0.98-0.99)a | 0.99 (0.98-0.99)a | 0.99 (0.99-0.99)a |

| County rural-urban status | |||||

| Metropolitan | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Rural adjacent to a metropolitan county | 0.89 (0.80-0.99)b | 0.86 (0.73-1.00) | 0.86 (0.74-0.99)b | 0.90 (0.80-1.01) | 0.88 (0.79-0.98)b |

| Rural remote | 1.07 (0.95-1.22) | 1.15 (0.96-1.38) | 1.07 (0.91-1.25) | 1.11 (0.97-1.26) | 1.09 (0.96-1.24) |

| Year | 1.07 (1.00-1.15)b | 1.16 (1.06-1.28)c | 0.95 (0.85-1.07) | 1.07 (1.00-1.14)b | 1.05 (0.98-1.12) |

Abbreviations: HPSA, Health Professional Shortage Area; NA, not applicable.

Statistically significant with P < .001.

Statistically significant with P < .05.

Statistically significant with P < .01.

Definitions of Economic Research Service county typology codes are listed in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Race and ethnicity were categorized as listed on the death certificate.

In model 2, after adjusting for county characteristics, county mental health HPSA designation was associated with higher youth firearm suicide rates (aIRR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.13-1.42). In model 3, the adjusted youth suicide rate increased by 4% for every 1-point increase in the county mental health HPSA score (aIRR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02-1.06).

In sensitivity analyses, the adjusted youth suicide rate decreased as the number of practicing child psychiatrists increased (aIRR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.72-0.91 for 6 to 60 child psychiatrists and aIRR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.52-0.74 for more than 60 child psychiatrists; reference group, 0 child psychiatrists) (model 4). When using alternate definitions of socioeconomic variables, we continued to find an association between county mental health HPSA designation and youth suicide rates (model 5).

Discussion

We found that youth suicide rates in the US are associated with county mental health professional workforce shortages, after adjusting for county demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. This association remains significant for the subgroup of youth firearm suicides. Notably, we found that youth suicide rates increase as the degree of mental health professional workforce shortages increases.

Mental health problems are among the most common precipitating factors for youth suicide.27 Up to 1 in 5 children in the US has a mental health condition,28 but only about half of children who need mental health care receive it.29 Shortages of mental health professionals contribute to this unmet need, with geographic variation in workforce shortages across the US.6,7,8 For instance, child psychiatrists are significantly less likely to practice in low-income counties, counties with low levels of postsecondary education, and counties adjacent to metropolitan regions compared with metropolitan counties.6 Youth suicides are also known to vary geographically across the US, with higher suicide rates in high poverty and rural counties.4,30,31 To our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate an independent association between youth suicide rates and mental health workforce shortages at the county level, after adjusting for other county characteristics.

We chose to use mental health HPSA designation as our marker for mental health professional workforce shortage for several reasons. First, it takes into account clinician supply relative to need, rather than only clinician supply. Second, multiple types of mental health professionals are reflected within the score, rather than just psychiatrists. Third, it is directly relevant to policy in that it is used to inform federal interventions and programs to reduce clinician workforce shortages, such as HRSA’s National Health Services Corps.14,32

In contrast to our a priori hypothesis, we found that mental health workforce shortages were associated with increased youth firearm suicide rates. Because firearms are the most lethal means for suicide attempts, a single impulsive act may result in death.33 Compared with suicides by other methods, firearm suicides are less likely to be preceded by a known mental health condition.11 In a prior study conducted at the state level,34 higher mental health treatment capacity was not associated with firearm suicide rates among individuals aged 10 to 24 years. Our analysis differed in that we included younger youth (5 to 19 years old), who might be more sensitive to preventive interventions and our county-level analysis may have better accounted for heterogeneity occurring within states. We acknowledge that household firearm ownership might confound our results, as state-level household firearm ownership has previously been associated with youth suicides.35 In addition to expanding the mental health workforce, policies that restrict firearm access to young people may be considered as a suicide prevention strategy.36,37

We found that adjusted youth suicide rates were higher in counties with lower median household income. It is well established that poverty and related social determinants of health lead to adverse child health outcomes and county-level poverty has previously been associated with youth suicide rates.4,38 We also found youth suicides increased as the proportion of uninsured children increased. Prior studies have shown that uninsured children are less likely to access needed mental health services.39,40 Reducing poverty, addressing social determinants of health, and improving insurance coverage may be considered as components of a multipronged societal strategy to improve child health and reduce youth suicides.

Efforts are needed to enhance the mental health professional workforce to match current levels of need.41 For instance, several programs funded by HRSA focus on workforce development in underserved and rural communities.42 Investments are also needed to build a diverse mental health workforce that is adept at delivering culturally and linguistically relevant care.43 Improving reimbursement rates for mental health services may further aid in recruitment and retention of mental health professionals.44 Additionally, mental health capacity can be increased through integration of mental health care into primary care settings and schools and through expansion of telehealth services.45,46,47 Prospective studies are needed to determine whether improvements in mental health professional workforce shortages at the county level will reduce youth suicides.

Limitations

Because the CMF is an administrative database, there is potential for misclassification of demographics or cause of death.48 More recent county-level mortality data after 2016 is not available in the CMF.12 The data sets did not have available variables to assess actual use of mental health services or household firearm ownership, which may mediate the association between mental health professional shortages and youth suicides. Also, our models did not account for possible spatial autocorrelation. In our study design, there is potential for an ecological fallacy, as associations at the county level might not hold true when considering smaller levels of analysis, such as the city, neighborhood, or individual; however, more granular, nationally representative data on suicide location are not available. We believe that county-level information will nevertheless help inform policy and interventions to prevent youth suicide.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional sudy shows that mental health professional workforce shortages at the county level were associated with increased youth suicides in the US. Our results have relevance to policy considerations and the development of interventions to reduce youth suicides. While this study involved data collected prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, several studies suggest declining youth mental health, which is likely to exacerbate mental health workforce shortages even further.49,50,51 Strategies to ameliorate mental health professional workforce shortages, such as workforce development programs and integration of mental health care into primary care and schools, may be considered in comprehensive youth suicide prevention programs.

eTable 1. Criteria Used to Designate and Score Counties as Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSA) for Mental Health

eTable 2. Definitions of Economic Research Service County Typology Codes

References

- 1.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- 2.Sturm R, Ringel JS, Andreyeva T. Geographic disparities in children’s mental health care. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):e308. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.e308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fontanella CA, Hiance-Steelesmith DL, Phillips GS, et al. Widening rural-urban disparities in youth suicides, United States, 1996-2010. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):466-473. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann JA, Farrell CA, Monuteaux MC, Fleegler EW, Lee LK. Association of pediatric suicide with county-level poverty in the United States, 2007-2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(3):287-294. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim WJ; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Task Force on Workforce Needs . Child and adolescent psychiatry workforce: a critical shortage and national challenge. Acad Psychiatry. 2003;27(4):277-282. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.27.4.277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McBain RK, Kofner A, Stein BD, Cantor JH, Vogt WB, Yu H. Growth and distribution of child psychiatrists in the United States: 2007-2016. Pediatrics. 2019;144(6):e20191576. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Holzer CE, Morrissey JP. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1323-1328. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings JR, Allen L, Clennon J, Ji X, Druss BG. Geographic access to specialty mental health care across high-and low-income US communities. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):476-484. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Health Resources & Services Administration . Scoring shortage designations. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/workforce-shortage-areas/shortage-designation/scoring

- 10.Texas Department of State Health Services . Health professional shortage area designations. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://www.dshs.state.tx.us/tpco/HPSADesignation/

- 11.Boggs JM, Simon GE, Ahmedani BK, Peterson E, Hubley S, Beck A. The association of firearm suicide with mental illness, substance use conditions, and previous suicide attempts. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):287-288. doi: 10.7326/L17-0111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . About compressed mortality, 1999-2016. Accessed October 14, 2022. https://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd10.html

- 13.US Health Resources & Services Administration . Data downloads. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://data.hrsa.gov/data/download

- 14.US Health Resources & Services Administration . What is shortage designation? Accessed October 11, 2022. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/workforce-shortage-areas/shortage-designation

- 15.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Annest J, Hedegaard H, Chen L, Warner M, Smalls E; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, National Center for Health Statistics, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Proposed framework for presenting injury data using ICD-10-CM external cause of injury codes. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/icd-10-cm_external_cause_injury_codes-a.pdf

- 17.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200630.939347/full/

- 18.Ku BS, Druss BG. Associations between primary care provider shortage areas and county-level COVID-19 infection and mortality rates in the USA. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:3404-3405. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06130-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehrenthal DB, Kuo HD, Kirby RS. Infant mortality in rural and nonrural counties in the United States. Pediatrics. 2020;146(5):e20200464. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graves JM, Abshire DA, Mackelprang JL, Amiri S, Beck A. Association of rurality with availability of youth mental health facilities with suicide prevention services in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2021471. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farris KB. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research: Strategies for Improving Public Health. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(12):1977-1978. doi: 10.1177/106002800203601204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryvicker M. A conceptual framework for examining healthcare access and navigation: A behavioral-ecological perspective. Soc Theory Health. 2018;16(3):224-240. doi: 10.1057/s41285-017-0053-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service . Rural-urban continuum codes. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/

- 24.Patrick SW, Faherty LJ, Dick AW, Scott TA, Dudley J, Stein BD. Association among county-level economic factors, clinician supply, metropolitan or rural location, and neonatal abstinence syndrome. JAMA. 2019;321(4):385-393. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.20851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service . County typology codes. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/county-typology-codes/

- 26.Stepner M. Maptile: a Stata program that makes mapping easy. Accessed April 12, 2022. https://michaelstepner.com/maptile/

- 27.Karch DL, Logan J, McDaniel DD, Floyd CF, Vagi KJ. Precipitating circumstances of suicide among youth aged 10-17 years by sex: data from the National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 states, 2005-2008. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(1)(suppl):S51-S53. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perou R, Bitsko RH, Blumberg SJ, et al. Mental health surveillance among children–United States, 2005-2011. MMWR Suppl. 2013;62(2):1-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whitney DG, Peterson MD. US national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(4):389-391. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fontanella CA, Saman DM, Campo JV, et al. Mapping suicide mortality in Ohio: a spatial epidemiological analysis of suicide clusters and area level correlates. Prev Med. 2018;106:177-184. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steelesmith DL, Fontanella CA, Campo JV, Bridge JA, Warren KL, Root ED. Contextual factors associated with county-level suicide rates in the United States, 1999 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1910936. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Streeter RA, Snyder JE, Kepley H, Stahl AL, Li T, Washko MM. The geographic alignment of primary care health professional shortage areas with markers for social determinants of health. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conner A, Azrael D, Miller M. Suicide case-fatality rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014 a nationwide population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(12):885-895. doi: 10.7326/M19-1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstein E V., Prater LC, Wickizer TM. Preventing adolescent and young adult suicide: do states with greater mental health treatment capacity have lower suicide rates? J Adolesc Heal. 2021;70(1):83-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knopov A, Sherman RJ, Raifman JR, Larson E, Siegel MB. Household gun ownership and youth suicide rates at the state level, 2005-2015. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(3):335-342. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kappelman J, Fording RC. The effect of state gun laws on youth suicide by firearm: 1981-2017. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2021;51(2):368-377. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azad HA, Monuteaux MC, Rees CA, et al. Child access prevention firearm laws and firearm fatalities among children aged 0 to 14 years, 1991-2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(5):463-469. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gitterman BA, Flanagan PJ, Cotton WH; Council on Community Pediatrics . Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160339. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Busch SH, Horwitz SM. Access to mental health services: are uninsured children falling behind? Ment Health Serv Res. 2004;6(2):109-116. doi: 10.1023/B:MHSR.0000024354.68062.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548-1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boat TF, Land ML Jr, Leslie LK. Health care workforce development to enhance mental and behavioral health of children and youths. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1031-1032. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kepley HO, Streeter RA. Closing behavioral health workforce gaps: a HRSA program expanding direct mental health service access in underserved areas. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6)(suppl 3):S190-S191. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yun K, Jenicek G, Gerdes M. Overcoming language barriers in mental and behavioral health care for children and adolescents-policies and priorities. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(6):511-512. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Covino NA. Developing the behavioral health workforce: lessons from the states. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2019;46(6):689-695. doi: 10.1007/s10488-019-00963-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walter HJ, Vernacchio L, Trudell EK, et al. Five-year outcomes of behavioral health integration in pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20183243. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sekhar DL, Schaefer EW, Waxmonsky JG, et al. Screening in high schools to identify, evaluate, and lower depression among adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2131836. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.31836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bettencourt AF, Plesko CM. A systematic review of the methods used to evaluate child psychiatry access programs. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(8):1071-1082. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arias E, Heron M, Hakes J; National Center for Health Statistics; US Census Bureau . The validity of race and Hispanic-origin reporting on death certificates in the United States: an update. Vital Health Stat 2. 2016;(172):1-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saunders NR, Kurdyak P, Stukel TA, et al. Utilization of physician-based mental health care services among children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(4):e216298. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.6298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radhakrishnan L, Carey K, Hartnett KP, et al. Pediatric emergency department visits before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 2019-January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(8):313-318. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7108e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.American Academy of Pediatrics . AAP-AACAP-CHA declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Criteria Used to Designate and Score Counties as Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSA) for Mental Health

eTable 2. Definitions of Economic Research Service County Typology Codes