Highlights

-

•

RIG-I appears earlier in the evolutionary process.

-

•

RLRs in aquatic animals include RIG-I, MDA5, LGP2, mollusc RIG-I-like and MDA5-like proteins.

-

•

RIG-I lacks in the order of Perciformes, Cichliformes, and Pleuronectiformes.

-

•

Aquatic animal LGP2 works as an immune homeostasis regulator.

-

•

The prototype of antiviral immune system has emerged in aquatic mollusc.

Keywords: RIG-I-like receptor, Aquatic animal, RIG-I, MDA5, LGP2

Abstract

Retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs) sense microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) to activate the innate immune responses. RLRs in aquatic animals include RIG-I, MDA5, LGP2, mollusc RIG-I-like and MDA5-like proteins, which exhibit structural and functional diversity. RLRs data from 30 species of aquatic animals were collected for analysis. Not all species contain all the RLR members. RIG-I is absent in the orders of Perciformes, Cichliformes and Pleuronectiformes, and LGP2-like protein is absent in the class of Bivalvia. Due to the differences in species and variants, the homologous proteins have different responses to pathogens. LGP2 works as an immune homeostasis regulator to balance the immune response. The phylogenetic analysis demonstrates RIG-I and mollusc RIG-I-like present in the same evolutionary branch and appear in the early stage. RIG-I is an ancient PRR in innate antiviral immunity. The prototype of antiviral immune system has emerged in aquatic mollusc. Aquatic animal RLRs were analyzed and summarized in terms of structures, functions, and evolutions, which provide the basic information for future researches in RLRs. Base on the diversity of species and RLRs, more and in-depth studies in aquatic animal RLRs should be done.

1. Introduction

A lot of pathogens live in water, which could make aquatic animals sick [1]. For aquatic animals, the innate immune system is the first line to protect them against those pathogens via the microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) were recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) [2], [3], [4],. Currently, there are five major PRR families which were reported, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), retinoic acid-inducible gene I-like receptors (RLRs), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) [5], [6], [7], and cytosolic DNA sensors [8]. RLRs belong to the family of DExD/H-box RNA helicases. There are three members in RLRs, retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5), and laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 (LGP2) [9].

2. The discovery and identification of aquatic animal RLR genes

Aquatic animal RLR genes (Table 1) were searched in several ways, including that amplifying with degenerate primers by PCR, searching the counterparts with mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians from transcriptome or proteome by BLAST. After that, all the sequences are verified by PCR and BLAST analysis.

Table 1.

Currently reported RLRs in aquatic animals.

| Animal | Latin name | RIG-I | MDA5 | LGP2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zebra fish | Danio rerio | JX462558.1 | JX462556.1 | KP341002.1 |

| Grass carp | Ctenopharyngodon idella | ADC81089 | FJ542045.2 | FJ813483.2 |

| Common carp | Cyprinus carpio | HQ850439.1 | KM374815.1 | KM374816.1 |

| Gold fish | Carassius auratus | JF970225.1 | JF970226.1 | JF970227.1 |

| Black carp | Mylopharyngodon piceus | KX871189.1 | KX344501.1 | |

| Barbel chub | Squaliobarbus curriculus | MK759919.1 | KU955846.1 | MH512892.1 |

| Indian major carp | Labeo rohita | MN029108.1 | ||

| Fathead minnow | Pimephales promelas | MG799354.1 | ||

| Channel catfish | Ictalurus punctatus | JQ008940.1 | JQ008942.1 | JQ008941.1 |

| Mandarin fish | Siniperca chuatsi | MF034730.1 | MK625658.1 | |

| Barramundi | Lates calcarifer | KX268680.1 | KX268683.1 | |

| Brown croaker | Miichthys miiuy | KX351161.1 | ||

| Orange-spotted grouper | Epinephelus coioides | HQ880665.1 | KX257806.1 | |

| Japanese sea bass | Lateolabrax japonicus | KU317137.1 | KR062119.1 | |

| Barred knifejaw | Oplegnathus fasciatus | KF267452.1 | KF267451.1 | |

| Atlantic salmon | Salmo salar | FN178459.2 | KU376486.1 | BT045378.1 |

| Rainbow trout | Oncorhynchus mykiss | FN396357.1 | FN396358.1/FN396359.1 | |

| Tilapia | Oreochromis niloticus | MG680273.1 | MG680274.1 | |

| Green chromide | Etroplus suratensis | KM014661.1 | ||

| Olive flounder | Paralichthys olivaceus | HQ401014.1 | HM070372.1 | |

| Turbot | Scophthalmus maximus | MK214453.1 | ||

| Large yellow croaker | Larimichthys crocea | KU886064.1 | KU886062.1 | |

| Atlantic cod | Gadus morhua | HM046436.1 | ||

| Four-eyed sleeper | Bostrychus sinensis | MK091422.1 | MK091420.1 | |

| Japanese eel | Anguilla japonica | KT156978.1 MK838769.1 MK838770.1 | ||

| Bamboo shark | Chiloscyllium griseum | HG964657.1 | HG964652.1; | |

| California sea hare | Aplysia californica | XM_005104310.3 | ||

| Far eastern brook lamprey | Lethenteron reissneri | MN988676.1 | ||

| Japanese lancelet | Branchiostoma japonicum | KR560072.1 | ||

| Pacific oyster | Crassostrea gigas | KC702507.1 | ||

| Mediterranean mussel | Mytilus galloprovincialis | AJQ21533.1 | ||

| Yesso scallop | Patinopecten yessoensis | PY-10413.4/PY-10413./PY-443.7/ PY-443.8 | ||

In zebrafish, RIG-I, MDA5 and LGP2 have two variants, named as RIG-Ia, RIG-Ib, MDA5a, MDA5b, LGP2a, and LGP2b. RIG-Ia is more 38 amino acids than RIG-Ib, and those 38 amino acids has not been found in other RIG-I sequences [10]. MDA5b lacks 312 amino acids at C-terminal [11]. LGP2b is shorter 54 amino acids than LGP2a [12]. After that, other scientists found that zebrafish LGP2b lacks 121 amino acids at the C-terminal after compared with LGP2a [13]. Grass carp RIG-I is cloned by degenerate primers based on the multiple alignments of DDX58 of Mus musculus, Sus scrofa and Bos taurus, and RIG-I of Homo sapiens [14]. Based on the multiple alignments of IFIH1 from Gallus gallus, Danio rerio, Equus caballus, M. musculus, H. sapiens, and MDA5 from Monodelphis domestica, grass carp MDA5 is cloned by degenerate primers, which is first full-length MDA5 identified in teleost [15]. Grass carp LGP2 is cloned by degenerate primers based on the multiple alignments of DHX58 of Salmo salar, H. sapiens, M. musculus, and Xenopus laevis [16]. Common carp RIG-I is cloned based on the multiple alignments of RIG-I from salmon, pig, human, and mouse [17]. Common carp MDA5 is cloned based on the multiple alignments of MDA5 from grass carp, zebrafish, and human [18]. Common carp LGP2 is cloned based on the multiple alignments of LGP2 in zebrafish, channel catfish, Japanese flounder, grass carp, Atlantic salmon, and goldfish [19]. Goldfish RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 are cloned by using RACE-PCR [20]. Barbel chub MDA5 is cloned based on the conserved sequences of MDA5 from other species [21]. RIG-I and LGP2 of barbel chub were uploaded to NCBI in 2019 and 2018 respectively. Black carp MDA5 is cloned based on the sequences of MDA5 from grass carp, common carp, zebrafish, and human [22]. Black carp LGP2 is cloned based on the multiple alignments of LGP2 in grass carp, zebrafish, and human [23]. Indian major carp LGP2 is cloned based on the conserved nucleotide sequence of LGP2 of grass carp, and common carp [24]. Fathead minnow MDA5 were uploaded to NCBI in 2018.

Three isoforms of Japanese eel RIG-I are cloned based on the sequence of zebrafish RIG-I. Japanese eel RIG-I has 933 amino acids, RIG-Ib has 940 amino acids, and RIG-Ibv has 843 amino acids which lacks RD domain [25], [26]. RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 of Channel catfish are cloned by using those sequences from zebrafish and human [27]. MDA5 and LGP2 of large yellow croaker are cloned based on the sequences from Stegastes partitus, Takifugu rubripes, Paralichthys olivaceus, Oryzias latipes, Poecilia formosa, Fundulus heteroclitus, Esox lucius, S. salar, Clupea harengus, D. rerio, Ctenopharyngodon idella, Carassius auratus, Ictalurus punctatus, G. gallus, H. sapiens, M. musculus, Rattus norvegicus, Canis lupus familiaris, S. scrofa, B. taurus [28]. Atlantic salmon RIG-I is cloned by using BLAST analysis of those sequences from zebrafish and common carp [29]. Due to the high similarity of the nucleotide between rainbow trout and Atlantic salmon, Atlantic salmon MDA5 is cloned based on the sequence of rainbow trout MDA5 [30]. Atlantic salmon LGP2 is also reported [31]. Atlantic cod LGP2 is cloned based on the expressed sequence tag, RIG-I of Atlantic cod is found in NCBI [32]. Mandarinfish MDA5 and LGP2 are cloned by using 5’- and 3’- RACE techniques [33]. Asian seabass MDA5 and LGP2 are cloned based on the conserved nucleotide sequence of MDA5 from Oreochromis niloticus, P. olivaceus, S. salar, Epinephelus coioides, and Oncorhynchus mykiss [34], [35]. Brown croaker LGP2 is cloned based on the LGP2 sequences from different species [36]. Tilapia MDA5 and LGP2 are cloned based on the predicted cDNA sequences of MDA5 and LGP2 [37]. Orange-spotted grouper MDA5 and LGP2 are cloned based on the expressed sequence tag from grouper spleen transcriptome[38], [39]. Japanese flounder MDA5 and LGP2 are cloned based on the multiple alignments of MDA5 sequences from human, pig, medaka, mouse, and zebrafish [40], [41]. Four-eyed sleeper MDA5 and LGP2 are cloned from the transcriptome and based on the multiple alignments of grouper, large yellow croaker, and tiger puffer [42]. Japanese sea bass MDA5 and LGP2 are cloned based on the multiple alignments of those sequences from Oplegnathus fasciatus, S. salar, and P. olivaceus [43], [44]. Green chromide MDA5 is cloned based on the multiple alignments of MDA5 from Haplochromis burtoni, Maylandia zebra, O. niloticus, and P. olivaceus [45].

Grey bamboo shark is the only one cartilaginous fish for which RLRs have been reported. The RIG-I and MDA5 of grey bamboo shark are identified by transcriptome alignment, which are matching to RIG-I of M. musculus and MDA5 of Chrysemyl picta bellii [46].

Base on the phylogenetic and domain analysis, the RIG-I of lamprey was found and identified [47]. Amphioxus LGP2 was cloned by RACE [48].

The RLRs have also been found in mollusc, which can be called as RIG-I-like or MDA5-like protein. Pacific oyster RIG-I is cloned based on the expressed sequence tag, and MDA5 is obtained from the proteome analysis [49], [50]. RLR genes in Yesso scallop are obtained from the transcriptome based on the RLR sequences of human, mouse, zebrafish and pacific oyster [51]. Mediterranean mussel RLR was searched from the immunity-related transcriptome [52].

RLRs are widely distributed in a variety of aquatic animals, but not every aquatic animal has all the RLR members. Based on the data of RLRs from 30 aquatic species, which are published and collected, RIG-I is still not reported in the order of Perciformes, Cichliformes, and Pleuronectiformes, LGP2 is not reported in the class of Bivalvia.

3. The subcellular location of aquatic animal RLRs genes

Normally, RLRs locate in the cytosol, but due to the cell status, the process of the immune responses, RLRs distribute in different subcellular locations or be recruited to the functional areas.

Zebrafish RIG-Ia expresses in the whole cell, but RIG-Ib, which lacks 38 amino acids, clusters around the nucleus [10]. Zebrafish MDA5a and MDA5b present in the whole cytosol [11]. Black carp MDA5 and LGP2 express in the cytosolic area [22], [23]. Trout LGP2a and LGP2b locate around the nucleus, and MDA5 expresses in the global cytosol [12]. Brown croaker LGP2 locates in the cytoplasmic matrix [36]. Tilapia MDA5 locates in the cytoplasm, and LGP2 locates throughout the cytoplasm and nucleus [37]. Sea perch LGP2 expresses in the whole cytosol [44]. Orange-spotted grouper MDA5 and LGP2 locate in the cytoplasm, but the distribution is changed after SGIV infection, MDA5 is recruited into spots and LGP2 is in the nucleus [38], [39].

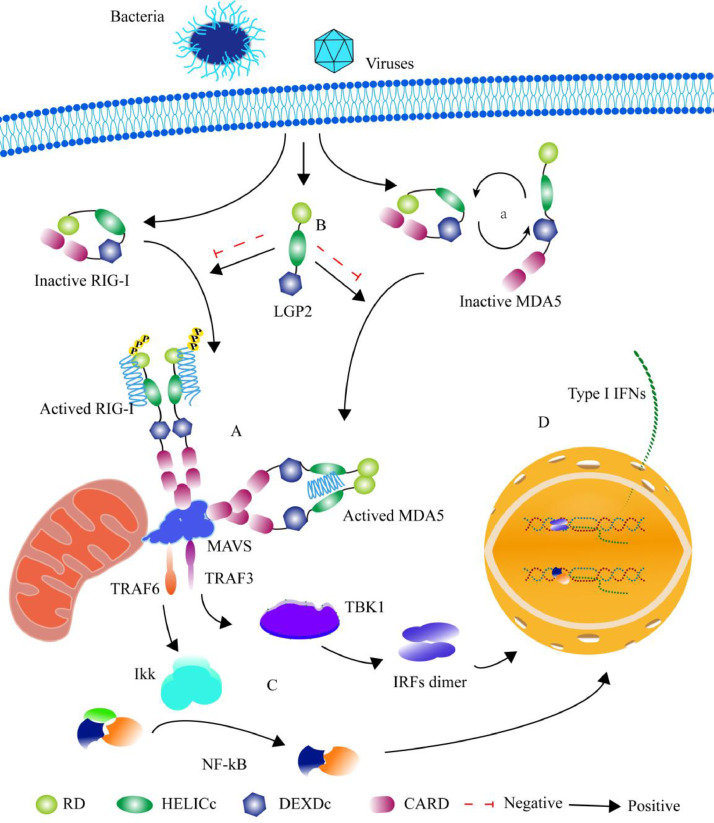

4. The functions of aquatic animal RLRs

RLRs work as sensors to recognize and interact with the MAMPs and activate the innate immune responses [53]. Pathogens invade cells and release the MAMPs, which activate the inactive RIG-I and MDA5. RIG-I recognizes and binds to the 5’-triphosphate short dsRNA, then the conformation of RIG-I is changed, and the dimer of active RIG-Is is binding to adaptor MAVS (Mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein) to activate downstream response (Fig. 1A) [54], [55], [56]. MDA5 detects and binds to long dsRNA as a dimer to activate the response via binding to MAVS (Fig. 1A) [57]. RIG-I exists as a close form in inactive status. MDA5 has two forms in inactive status, open and close (Fig. 1A) [57], [58]. LGP2 is an important regulator in the RIG-I signaling pathway. Due to the pathogens and species of hosts, LGP2 enhances the function of RIG-I- and MDA5- mediate immunity response on occasion, or sometimes represses the activity of RIG-I and MDA5 (Fig. 1B) [59], [60]. MAVS recruits TRAF3/6 (Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 3/6), TRAF3 recruits IKK (IκB protein kinase complex), and TRAF6 recruits TBK1 (TANK binding kinase 1) [61], [62], [63]. NF-κB (nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) and IRFs (Interferon (IFN) regulatory factors) are activated by IKK and TBK1 respectively (Fig. 1C) [64], [65]. The activated transcriptional regulators, NF-κB and IRFs, enter the nucleus and promote transcription of type I IFN (IFN-I) and inflammatory factor genes (Fig. 1D) [66]. This reaction is one of the first lines of defense during pathogen infections.

Fig. 1.

RLRs activate the immune responses to defense pathogens. RIG-I recognizes and binds to the 5’-triphosphate short RNA, MDA5 detects and binds to long dsRNA as a dimer to activate the down-stream responses via binding to MAVS (A). RIG-I exists as a close form in inactive status, MDA5 has two forms in inactive status, open and close (a). LGP2 enhance the function of RIG-I- and MDA5- mediated immune responses on occasion, or sometimes represses the activity of RIG-I and MDA5 (B). MAVS recruits TRAF3/6, TRAF3 recruits IKK, and TRAF6 recruits TBK1. NF-κB and IRFs are activated by IKK and TBK1 respectively (C). Transcription of IFN-I genes (D)

4.1. Aquatic animal RLRs regulate IFNs and NF-κB

Aquatic animals have an abundance of RLRs, and different structures, different isoforms, and different domains of RLRs can have different effects on the expression of downstream genes, especially regulating the expression of IFNs and NF-κB.

Zebrafish RIG-Ib can significantly induce the activation of the promoter of IFN, but RIG-Ia can not [10]. Zebrafish MDA5a and MDA5b can induce the activation of the promoter of IFN, and zebrafish MDA5a is much higher than MDA5b [11]. Overexpression of the CARD domain of Atlantic salmon RIG-I can induce the expression of IFN [29]. The overexpression of tilapia MDA5 can inhibit the activation of NF-κB, but LGP2 had no effect on the activation of NF-κB [37].

4.2. RLR responses to pathogenic stimulation

Different RLRs in the different aquatic animals give different responses to the different stimulations. RLRs have a strong response to the invasion of virus because those are the recognized receptors of the antiviral pathway. But RLRs also have a response to bacterial infection. The expressions of zebrafish RIG-Ia and RIG-Ib are significantly up-regulated after treatment with spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV) and Edwardsiella tarda, but RIG-Ib can provide better protection than RIG-Ia in SVCV infection, and RIG-Ib expresses higher than RIG-Ia in the untreated cell [10]. The expression level of MDA5a is higher than MDA5b in the normal cell, both of them are working well against the SVCV infection, and MDA5b also works as an enhancer to help MDA5a and MAVS in the antiviral pathway [11]. After grass carp reovirus (GCRV) infection, the expression of grass carp RIG-I is significantly up-regulated from 8 to 24 h post infection (hpi) to defense the infection [14]. Grass carp MDA5 is significantly up-regulated from 12 to 48 hpi against GCRV infection [15]. From 12 hpi to 48 hpi, the expression level of grass carp LGP2 is increased rapidly, the overexpression of LGP2 can protect the cells from GCRV infection via inhibiting the replication of GCRV, but LGP2 works as a negative regulator to inhibit the antiviral pathway via suppressing K63-linked and K48-linked ubiquitination of RIG-I and MDA5 at the early stage of GCRV infection [16], [91], [92]. After SVCV infection, common carp RIG-I is up-regulated in the spleen, head kidney, and intestine [17]. After Aeromonas hydrophila stimulated, common carp MDA5 is significantly up-regulated in the first 12 h [18]. After koi herpesvirus (KHV) infection, the expression level of common carp LGP2 is significantly up-regulated [19]. Overexpression of black carp MDA5 in EPC can defend against SVCV and GCRV infections [22]. After GCRV or SVCV infection, black carp LGP2 is significantly up-regulated and against the infection [23]. After GCRV infection, barbel chub MDA5 is rapidly increased at the first 12 h [21]. After CCV infection and bacterial stimulation, RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 of channel catfish are significantly up-regulated from 18 to 24 h and 4 h, respectively [27]. After infectious pancreatic necrosis virus, infectious salmon anaemia virus, and salmonid alphavirus infection, RIG-I, MDA5 and LGP2 of Atlantic salmon are significantly increased from 4 h to 10 d [30]. Overexpression of rainbow trout MDA5 and LGP2a, can enhance the protection level against viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) infection, but overexpression of LGP2b suppresses the antiviral pathway. [12] After Streptococcus agalactiae infection, tilapia MDA5 and LGP2 are significantly up-regulated [37]. The overexpression of orange-spotted grouper MDA5 can inhibit the replication of the virus, but LGP2 enhances the replication of the virus. MDA5 positively regulates IFN response, but LGP2 works in an opposite way[38], [39]. Japanese flounder LGP2 significantly up-regulates after VHSV infection. The overexpression of Japanese flounder MDA5 and LGP2 can delay the cytopathic effects of the virus [40], [41]. After nervous necrosis virus (NNV) infection, sea perch MDA5 and LGP2 are significantly up-regulated. The replication of NNV is significantly increased when MDA5 is silenced by using RNAi [43], [44]. The lamprey RIG-I was significantly increased in GCRV infection [47].

Based on the previous studies, RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 possess a high antiviral activity which can inhibit the replication of virus or delay the cytopathic effects of the virus. And some of the subtypes reinforce each other against virus. But LGP2 shows a widely function, it can suppress the antiviral pathway in some situations, and it also can protect away from virus infection in other situations.

RLRs also have response to pathogens-like stimulators, such as ploy(I:C), PGN and LPS. After poly(I:C) stimulated, grass carp RIG-I is increased rapidly, common carp MDA5 and LGP2 are significantly up-regulated in the first 24 h[14], [18], [19]. Black carp MDA5 is decreased in the first 24 h after treatment with LPS, but up-regulated rapidly with poly(I:C) stimulation [22]. The transcription of black carp LGP2 is significantly up-regulated after poly(I:C) treatment, but there is not changed after LPS or PMA stimulation [23]. After stimulated with poly(I:C), large yellow croaker MDA5 and LGP2 mRNA expressions are significantly up-regulated from 6 to 24 h, peak at 12 h and 6 h respectively [21]. The expression of RIG-I, RIG-Ib, and RIG-Ibv of Japanese eel are significantly up-regulated after stimulated with poly(I:C), LPS, and A. hydrophila [25]. Brown croaker LGP2 is significantly increased after poly(I:C) stimulation, but not changed in challenging with Vibrio anguillarum, Vibrio harveyi, LPS [36]. Indian major carp LGP2 is significantly up-regulated after treated with poly(I:C), both in vivo and in vitro [24]. Japanese flounder MDA5 and LGP2 are significantly increased following poly(I:C) and LPS stimulation, [40], [41]. Four-eyed sleeper MDA5 and LGP2 are significantly up-regulated following poly(I:C) stimulation [42]. After poly(I:C) stimulation, sea perch MDA5 and LGP2 are significantly up-regulated [43], [44]. Green chromide MDA5 is significantly increased after poly(I:C) stimulated [45]. Atlantic cod LGP2 is significantly increased following poly(I:C) stimulation [32]. Following poly(I:C) and LPS stimulation, mandarinfish MDA5 and LGP2 are significantly up-regulated [33]. After challenged with poly(I:C), LPS, PGN, Vibrio alginolyticus, and Staphylococcus aureus, the expression of Asian seabass MDA5 and LGP2 are significantly up-regulated [35]. Shellfish RLRs also have the immunoreactivity to the stimulation. Pacific oyster RIG-I is significantly up-regulated after poly(I:C) stimulation [50].

4.3. The modifications of RLRs affect the immunity responses

Modifications are very important regulatory manners in the life activities, such as methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, acetylation. DNA methylation is one of the chromatin modifications, which is also studied widely, that plays an important role in gene transcribing, maintaining the hematopoietic, and regulating the functions of the immune system [67].

DNA methylation of aquatic animal RLRs affects the immunity response [68]. DNA methylation of grass carp RIG-I at -534 CpG site is significantly reduced resistance to against GCRV infection in vivo [69]. DNA methylation at densely methylated elements of grass carp MDA5, such as +200, +202, +204, +207 nt, are significantly increased susceptibility to GCRV in individuals [70]. But DNA methylation of grass carp LGP2 has no effect on the immune responses [71].

Ubiquitination is a regulated fundamental process in the cells, which modifies the target protein to regulate the functions [72], [73]. There are seven types of lysine residues for different regulations, such as K6 for DNA damage, K11 for cell cycle regulation and membrane trafficking, K27 for mitophagy and signal transduction, K29 for 5’ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) regulation, K33 for TCR signaling, K48 for proteasomal degradation, and K63 for signal transduction [74], [75]. In mammals, ubiquitination also regulates the immunity pathway. The K63-linked ubiquitin of RIG-I enhances the interaction between RIG-I and MAVS, to activate the downstream genes [76], [77]. But K48-liked polyubiquitin works in an opposite way, which leads to RIG-I degradation and negatively regulates the immune process [78], [79]. The K63-linked ubiquitination of 2 CARDs and RD in zebrafish RIG-I could enhance IFN promoter activity to defense red grouper nervous necrosis virus (RGNNV) infection [80].

5. The evolution of RLRs and their domains

Every protein is composed of one or more domains, the domain is part of the protein polypeptide chain and an important part of protein function[81], [82]. Four conservative domains partially or fully present in the RLRs, caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD), DEAD/DEAH box helicase domain (DEXDc), helicase superfamily c-terminal domain (HELICc), repressor domain (RD)[54], [83]. The functions of domains affect the functions of the protein. CARD regulates caspase activation and cell apoptosis, and CARD-CARD interactions mediate the cell signaling[84], [85]. DEXDc can recognize RNA [86]. Overexpression of the CARD domains of grass carp MDA5 can induce the expressions of IFN-I and IL-1β [87].RD works as an inhibitor via interacting with helicase domain or CARD in the absence of the pathogens infection [88], [89], [90].

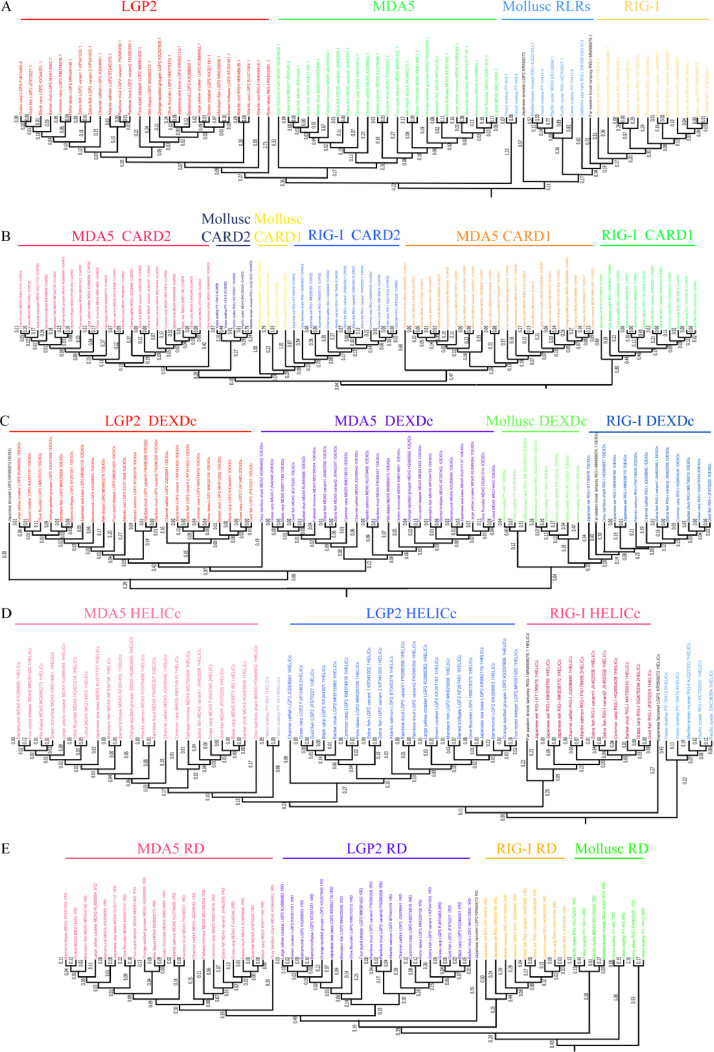

The evolution trees were constructed based on the RLRs data from 30 aquatic animals. The result shows that piscine RIG-Is cluster with the RLRs of mollusc, which means RIG-I appears earlier than MDA5 and LGP2 (Fig. 2A). The phylogenetic trees of the RLR domains were also made, including CARDs (Fig. 2B), DEXDc (Fig. 2C), HELICc (Fig. 2D), and RD (Fig. 2E). Those evolution trees of domains support the result from the evolution tree of aquatic animal RLRs.

Fig. 2.

The evolution of aquatic animal RLRs and domains. The phylogenetic trees of aquatic animals RLRs (A), CARD (B), DEXDc (C), HELICc (D) and RD (E).

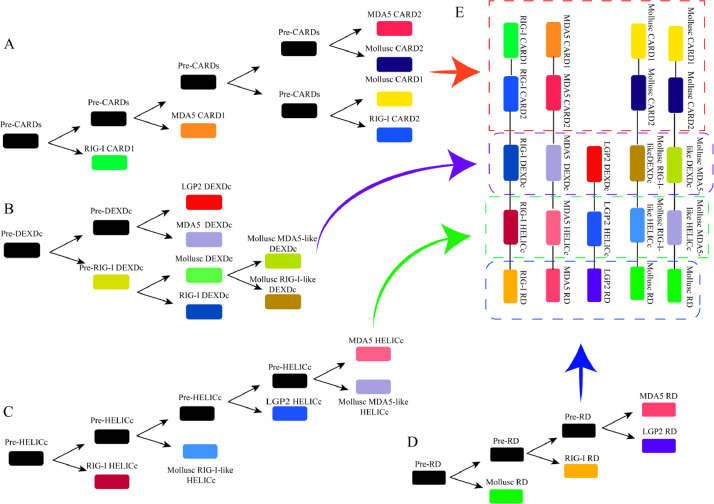

Base on the evolution trees of domains, the evolution pathways were established. In the divergence pathway of CARD (Fig. 3A), RIG-I CARD1 is the first CARD domain to be differentiated, MDA5 CARD1, MDA5 CARD2, RIG-I CARD2, mollusc CARD1, and CARD2 are differentiated later. The evolution pathways of DEXDc (Fig. 3B), HELICc (Fig. 3C), and RD (Fig. 3D) are shown in the same way. The structures of RLRs were assembled by domains based on the evolutionary pathways of domains (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

The divergence pathways of each domain of the aquatic animal RLRs and the splicing structures of RLRs. The divergence pathway of CARD (A), DEXDc (B), HELICc (C) and RD (D). The structures of RLRs were assembled by domains based on the divergence pathways of domains (E).

6. Conclusion and future perspective

RLRs in aquatic animals, include RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 in fish, mollusc RIG-I-like, and MDA5-like in mollusc. Some of them lack in several aquatic species, RIG-I is absent in the order of Perciformes, Cichliformes, and Pleuronectiformes, and MAD5 is not reported in Indian major carp, brown croaker, Atlantic cod, and Japanese eel, LGP2 is not reported in fathead minnow, green chromide, turbot, Atlantic cod, Japanese eel and the class of Bivalvia.

The structural integrity of RLRs has a significant impact on their function. Zebrafish RIG-Ia has 38 amino acids that no one else has, which makes RIG-Ia not induce the activation of the promoter of IFN. Rainbow trout LGP2b lacks 54 amino acids, which works as a negative regulator in antiviral response.

RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 possess a strong reaction to the viral invasion. RIG-I and MDA5 exhibit a powerful effect on antiviral, but LGP2 works as a regulator in the process of antiviral. In the different stages, LGP2 shows the different functions in the antiviral pathway, it is an immune homeostasis regulator to balance the immune response.

Aquatic animal RIG-I, especially aquatic mollusc RIG-I-like proteins, appears much more early than MDA5 and LGP2. It is an ancient PRR in innate antiviral immunity. It indicates the prototype of antiviral immune system has emerged in aquatic mollusc.

Aquatic animals are a huge population, it is estimated that there are over million species on earth. Bases on the evolutionary status of aquatic animals, the RLRs have richer diversity. More and in-depth studies on the aquatic animal RLRs should be done, which will help us to know more about the origins and development of innate immunity, and the evolution of RLRs from mollusc to teleost.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Prof. Qiang Xing and Haixing Zhu (Ocean University of China) for providing the four RLR sequences of Yesso scallop. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31873044).

References

- 1.Cabral JPS. Water microbiology. bacterial pathogens and water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2010;7:3657–3703. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7103657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janeway CA, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patten DA, Collett A. Exploring the immunomodulatory potential of microbial-associated molecular patterns derived from the enteric bacterial microbiota. Microbiology-Sgm. 2013;159:1535–1544. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.064717-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen S, Thomsen AR. Sensing of RNA viruses: a review of innate immune receptors involved in recognizing RNA virus invasion. J. Virol. 2012;86:2900–2910. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05738-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawasaki T, Kawai T, Akira S. Recognition of nucleic acids by pattern-recognition receptors and its relevance in autoimmunity. Immunol. Rev. 2011;243:61–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoneyama M, Fujita T. Recognition of viral nucleic acids in innate immunity. Rev. Med. Virol. 2010;20:4–22. doi: 10.1002/rmv.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiu YH, MacMillan JB, Chen ZJJ. RNA polymerase III detects cytosolic DNA and induces type I interferons through the RIG-I pathway. Cell. 2009;138:576–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar H, Kawai T, Akira S. Pathogen recognition in the innate immune response. Biochem. J. 2009;420:1–16. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou PF, Chang MX, Li Y, Zhang SH, Fu JP, Chen SN, Nie P. Higher antiviral response of RIG-I through enhancing RIG-I/MAVS-mediated signaling by its long insertion variant in zebrafish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015;43:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zou PF, Chang MX, Xue NN, Liu XQ, Li JH, Fu JP, Chen SN, Nie P. Melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 in zebrafish provoking higher interferon-promoter activity through signalling enhancing of its shorter splicing variant. Immunology. 2014;141:192–202. doi: 10.1111/imm.12179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang M, Collet B, Nie P, Lester K, Campbell S, Secombes CJ, Zou J. Expression and functional characterization of the RIG-I-like receptors MDA5 and LGP2 in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) J. Virol. 2011;85:8403–8412. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00445-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang WW, Asim M, Yi LZ, Hegazy AM, Hu XQ, Zhou Y, Ai TS, Lin L. Abortive infection of snakehead fish vesiculovirus in ZF4 cells was associated with the RLRs pathway activation by viral replicative intermediates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:6235–6250. doi: 10.3390/ijms16036235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang C, Su J, Huang T, Zhang R, Peng L. Identification of a retinoic acid-inducible gene I from grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) and expression analysis in vivo and in vitro. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2011;30:936–943. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su J, Huang T, Dong J, Heng J, Zhang R, Peng L. Molecular cloning and immune responsive expression of MDA5 gene, a pivotal member of the RLR gene family from grass carp Ctenopharyngodon Idella. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010;28:712–718. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang T, Su J, Heng J, Dong J, Zhang R, Zhu H. Identification and expression profiling analysis of grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idella LGP2 cDNA. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010;29:349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng H, Liu H, Kong R, Wang L, Wang Y, Hu W, Guo Q. Expression profiles of carp IRF-3/-7 correlate with the up-regulation of RIG-I/MAVS/TRAF3/TBK1, four pivotal molecules in RIG-I signaling pathway. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2011;30:1159–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu YY, Xing WX, Shan SJ, Zhang SQ, Li YQ, Li T, An L, Yang GW. Characterization and immune response expression of the Rig-I-like receptor mda5 in common carp Cyprinus carpio. J. Fish Biol. 2016;88:2188–2202. doi: 10.1111/jfb.12981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao XL, Chen JJ, Cao Y, Nie GX, Wan QY, Wang LF, Su JG. Identification and expression of the laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 gene in common carp Cyprinus carpio. J. Fish Biol. 2015;86:74–91. doi: 10.1111/jfb.12541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun F, Zhang YB, Liu TK, Shi J, Wang B, Gui JF. Fish MITA serves as a mediator for distinct fish IFN gene activation dependent on IRF3 or IRF7. J. Immunol. 2011;187:2531–2539. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Jin S, Zhao X, Luo H, Li R, Li D, Xiao T. Sequence and expression analysis of the cytoplasmic pattern recognition receptor melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 from the barbel chub Squaliobarbus curriculus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019;94:485–496. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J, Li J, Xiao J, Chen H, Lu L, Wang X, Tian Y, Feng H. The antiviral signaling mediated by black carp MDA5 is positively regulated by LGP2. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017;66:360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao J, Yan J, Chen H, Li J, Tian Y, Feng H. LGP2 of black carp plays an important role in the innate immune response against SVCV and GCRV. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016;57:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohanty A, Sadangi S, Paichha M, Samanta M. Molecular characterization and expressional quantification of lgp2, a modulatory co-receptor of RLR-signalling pathway in the Indian major carp Labeo rohita following pathogenic challenges and PAMP stimulations. J. Fish Biol. 2020;96:1399–1410. doi: 10.1111/jfb.14308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng J, Guo S, Lin P, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Zhang Z, Yu L. Identification of a retinoic acid-inducible gene I from Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) and expression analysis in vivo and in vitro. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016;55:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang B, Wang ZX, Zhang C, Zhai SW, Han YS, Huang WS, Nie P. Identification of a novel RIG-I isoform and its truncating variant in Japanese eel, Anguilla japonica. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019;94:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajendran KV, Zhang J, Liu S, Peatman E, Kucuktas H, Wang X, Liu H, Wood T, Terhune J, Liu Z. Pathogen recognition receptors in channel catfish: II. Identification, phylogeny and expression of retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs) Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2012;37:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen B, Zhang Y, Zheng S, Zeng J, Lin J. Molecular characterization and expression analyses of three RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway genes (MDA5, LGP2 and MAVS) in Larimichthys crocea. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016;55:535–549. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biacchesi S, LeBerre M, Lamoureux A, Louise Y, Lauret E, Boudinot P, Bremont M. Mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein plays a major role in induction of the fish innate immune response against RNA and DNA viruses. J. Virol. 2009;83:7815–7827. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00404-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nerbovik IKG, Solheim MA, Eggestol HO, Ronneseth A, Jakobsen RA, Wergeland HI, Haugland GT. Molecular cloning of MDA5, phylogenetic analysis of RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) and differential gene expression of RLRs, interferons and proinflammatory cytokines after in vitro challenge with IPNV, ISAV and SAV in the salmonid cell line TO. J. Fish Dis. 2017;40:1529–1544. doi: 10.1111/jfd.12622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leong JS, Jantzen SG, von Schalburg KR, Cooper GA, Messmer AM, Liao NY, Munro S, Moore R, Holt RA, Jones SJM, Davidson WS, Koop BF. Salmo salar and Esox lucius full-length cDNA sequences reveal changes in evolutionary pressures on a post-tetraploidization genome. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:279. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rise ML, Hall J, Rise M, Hori T, Gamperl AK, Kimball J, Hubert S, Bowman S, Johnson SC. Functional genomic analysis of the response of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) spleen to the viral mimic polyriboinosinic polyribocytidylic acid (pI:C) Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2008;32:916–931. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gu T, An C, Chen B, Wei W, Wu X, Xu Q, Chen G. MDA5 and LGP2 acts as a key regulator though activating NF-κB and IRF3 in RLRs signaling of mandarinfish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019;86:1114–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paria A, Deepika A, Sreedharan K, Makesh M, Chaudhari A, Purushothaman CS, Rajendran KV. Identification, ontogeny and expression analysis of a novel laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 (LGP2) transcript in Asian seabass, Lates calcarifer. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017;62:265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paria A, Makesh M, Chaudhari A, Purushothaman CS, Rajendran KV. Molecular characterisation, ontogeny and expression analysis of melanoma differentiation-associated factor 5 (MDA5) from Asian seabass, Lates calcarifer. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018;78:71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han J, Wang Y, Chu Q, Xu T. The evolution and functional characterization of miiuy croaker cytosolic gene LGP2 involved in immune response. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016;58:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao FY, Lu MX, Wang M, Liu ZG, Ke XL, Zhang DF, Cao JM. Molecular characterization and function analysis of three RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway genes (MDA5, LGP2 and MAVS) in Oreochromis niloticus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018;82:101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang Y, Yu Y, Yang Y, Yang M, Zhou L, Huang X, Qin Q. Antiviral function of grouper MDA5 against iridovirus and nodavirus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016;54:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu Y, Huang Y, Yang Y, Wang S, Yang M, Huang X, Qin Q. Negative regulation of the antiviral response by grouper LGP2 against fish viruses. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016;56:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohtani M, Hikima JI, Kondo H, Hirono I, Jung TS, Aoki T. Evolutional conservation of molecular structure and antiviral function of a viral RNA receptor, LGP2, in japanese flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. J. Immunol. 2010;185:7507–7517. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohtani M, Hikima JI, Kondo H, Hirono I, Jung TS, Aoki T. Characterization and antiviral function of a cytosolic sensor gene, MDA5, in Japanese flounder,Paralichthys olivaceus. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011;35:554–562. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou Z. (Master thesis). Zhejiang Ocean University; 2019. Molecular cloning and Immune response analysis of LGP2, MDA5 and MAVS genes of bostrychus sinensis. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jia P, Jia K, Chen L, Le Y, Jin Y, Zhang J, Zhu L, Zhang L, Yi M. Identification and characterization of the melanoma differentiation - associated gene 5 in sea perch, Lateolabrax japonicus. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2016;61:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2016.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jia P, Zhang J, Jin Y, Zeng L, Jia K, Yi M. Characterization and expression analysis of laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 gene in sea perch, Lateolabrax japonicus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015;47:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhat A, Paria A, Deepika A, Sreedharan K, Makesh M, Bedekar MK, Purushothaman CS, Rajendran KV. Molecular cloning, characterisation and expression analysis of melanoma differentiation associated gene 5 (MDA5) of green chromide, Etroplus suratensis. Gene. 2015;557:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gopalan TK, Gururaj P, Gupta R, Gopal DR, Rajesh P, Chidambaram B, Kalyanasundaram A, Angamuthu R. Transcriptome profiling reveals higher vertebrate orthologous of intra-cytoplasmic pattern recognition receptors in grey bamboo shark. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma A, Gou M, Song T, Li J, Zhu Y, Pang Y, Li Q. enomic analysis and functional characterization of immune genes from the RIG-I- and MAVS-mediated antiviral signaling pathway in lamprey. Genomics. 2021:(in press). doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2021.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu SS, Liu YY, Yang SS, Huang YH, Qin QW, Zhang SC. Evolutionary conservation of molecular structure and antiviral function of a viral receptor, LGP2, in amphioxus Branchiostoma japonicum. Eur. J. Immunol. 2015;45:3404–3416. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang G, Fang X, Guo X, Li L, Luo R, Xu F, Yang P, Zhang L, Wang X, Qi H, Xiong Z, Que H, Xie Y, Holland PWH, Paps J, Zhu Y, Wu F, Chen Y, Wang J, Peng C, Meng J, Yang L, Liu J, Wen B, Zhang N, Huang Z, Zhu Q, Feng Y, Mount A, Hedgecock D, Xu Z, Liu Y, Domazet-Loso T, Du Y, Sun X, Zhang S, Liu B, Cheng P, Jiang X, Li J, Fan D, Wang W, Fu W, Wang T, Wang B, Zhang J, Peng Z, Li Y, Li N, Wang J, Chen M, He Y, Tan F, Song X, Zheng Q, Huang R, Yang H, Du X, Chen L, Yang M, Gaffney PM, Wang S, Luo L, She Z, Ming Y, Huang W, Zhang S, Huang B, Zhang Y, Qu T, Ni P, Miao G, Wang J, Wang Q, Steinberg CEW, Wang H, Li N, Qian L, Zhang G, Li Y, Yang H, Liu X, Wang J, Yin Y, Wang J. The oyster genome reveals stress adaptation and complexity of shell formation. Nature. 2012;490:49–54. doi: 10.1038/nature11413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, Yu F, Li J, Tong Y, Zhang Y, Yu Z. The first invertebrate RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) homolog gene in the pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014;40:466–471. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu X, Liao H, Yang Z, Peng C, Lu W, Xing Q, Huang X, Hu J, Bao Z. Genome-wide identification, characterization of RLR genes in Yesso scallop (Patinopecten yessoensis) and functional regulations in responses to ocean acidification. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020;98:488–498. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gerdol M, Venier P. An updated molecular basis for mussel immunity. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015;46:17–38. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liao ZW, Wan QY, Su H, Wu CS, Su JG. Pattern recognition receptors in grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idella: I. Organization and expression analysis of TLRs and RLRs. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017;76:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brisse M, Ly H. Comparative structure and function analysis of the RIG-I-like receptors: RIG-I and MDA5. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1586. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feng M, Ding ZY, Xu L, Kong LL, Wang WJ, Jiao S, Shi ZB, Greene MI, Cong Y, Zhou ZC. Structural and biochemical studies of RIG-I antiviral signaling. Protein Cell. 2013;4:142–154. doi: 10.1007/s13238-012-2088-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kowalinski E, Lunardi T, McCarthy AA, Louber J, Brunel J, Grigorov B, Gerlier D, Cusack S. Structural basis for the activation of innate immune pattern-recognition receptor RIG-I by viral RNA. Cell. 2011;147:423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berke IC, Modis Y. MDA5 cooperatively forms dimers and ATP-sensitive filaments upon binding double-stranded RNA. EMBO J. 2012;31:1714–1726. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu YL, Olagnier D, Lin RT. Host and viral modulation of RIG-I-mediated antiviral immunity. Front. Immunol. 2017;7:662. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Quicke KM, Kim KY, Horvath CM, Suthar MS. RNA helicase LGP2 negatively regulates RIG-I signaling by preventing TRIM25-mediated caspase activation and recruitment domain ubiquitination. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2019;39:669–683. doi: 10.1089/jir.2019.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Satoh T, Kato H, Kumagai Y, Yoneyama M, Sato S, Matsushita K, Tsujimura T, Fujita T, Akira S, Takeuchi O. LGP2 is a positive regulator of RIG-I- and MDA5-mediated antiviral responses. PNAS. 2010;107:1512–1517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912986107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi CS, Qi HY, Boularan C, Huang NN, Abu-Asab M, Shelhamer JH, Kehrl JH. SARS-Coronavirus open reading frame-9b suppresses innate immunity by targeting mitochondria and the MAVS/TRAF3/TRAF6 signalosome. J. Immunol. 2014;193:3080–3089. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xie P. TRAF molecules in cell signaling and in human diseases. J. Mol. Signal. 2013;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shi ZB, Zhang Z, Zhang ZZ, Wang YY, Li CC, Wang X, He F, Sun LN, Jiao S, Shi WY, Zhou ZC. Structural insights into mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS)-tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:26811–26820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.666578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Isral A. The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-κB activation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2(3):a000158. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim MH, Yoo DS, Lee SY, Byeon SE, Lee YG, Min T, Rho HS, Rhee MH, Lee J, Cho JY. The TRIF/TBK1/IRF-3 activation pathway is the primary inhibitory target of resveratrol, contributing to its broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory effects. Pharmazie. 2011;66:293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iwanaszko M, Kimmel M. NF-κB and IRF pathways: cross-regulation on target genes promoter leve. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:307. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1511-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morales-Nebreda L, Mclafferty FS, Singer BD. DNA methylation as a transcriptional regulator of the immune system. Transl. Res. 2019;204:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chang MX. The negative regulation of retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs) signaling pathway in fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2021;119:104038. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2021.104038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shang XY, Wan QY, Su JG, Su JJ. DNA methylation of CiRIG-I gene notably relates to the resistance against GCRV and negatively-regulates mRNA expression in grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon Idella. Immunobiology. 2016;221:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shang XY, Su JG, Wan QY, Su JJ. CpA/CpG methylation of CiMDA5 possesses tight association with the resistance against GCRV and negatively regulates mRNA expression in grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idella. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2015;48:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shang XY, Su JG, Wan QY, Su JJ, Feng XL. CpG methylation in the 5 ’-flanking region of LGP2 gene lacks association with resistance/susceptibility to GCRV but contributes to the differential expression between muscle and spleen tissues in grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon Idella. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014;40:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chernorudskiy AL, Gainullin MR. Ubiquitin system: direct effects join the signaling. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:pe22. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pickart CM, Eddins MJ. Ubiquitin: structures, functions, mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1695:55–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ikeda F, Crosetto N, Dikic I. What determines the specificity and outcomes of ubiquitin signaling? Cell. 2010;143:677–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McDowell GS, Philpott A. Non-canonical ubiquitylation: mechanisms and consequences. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013;45:1833–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gack MU, Shin YC, Joo CH, Urano T, Liang C, Sun LJ, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Chen ZJ, Inoue SS, Jung JU. TRIM25 RING-finger E3 ubiquitin ligase is essential for RIG-I-mediated antiviral activity. Nature. 2007;446:916–920. doi: 10.1038/nature05732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rajsbaum R, Albrecht RA, Wang MK, Maharaj NP, Versteeg GA, Nistal-Villan E, Garcia-Sastre A, Gack MU. Species-specific inhibition of RIG-I ubiquitination and ifn induction by the influenza A virus NS1 protein. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(11):e1003059. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Arimoto KI, Takahashi H, Hishiki T, Konishi H, Fujita T, Shimotohno K. Negative regulation of the RIG-I signaling by the ubiquitin ligase RNF125. PNAS. 2007;104:7500–7505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611551104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Davis ME, Gack MU. Ubiquitination in the antiviral immune response. Virology. 2015;479:52–65. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jin YL, Jia KT, Zhang WW, Xiang YX, Jia P, Liu W, Yi MS. Zebrafish TRIM25 Promotes Innate Immune Response to RGNNV Infection by Targeting 2CARD and RD Regions of RIG-I for K63-Linked Ubiquitination. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:2805. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Buljan R, Bateman A. The evolution of protein domain families. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2009;37:751–755. doi: 10.1042/BST0370751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cagliani R, Forni D, Tresoldi C, Pozzoli U, Filippi G, Rainone V, De Gioia L, Clerici M, Sironi M. RIG-I-like receptors evolved adaptively in mammals, with parallel evolution at LGP2 and RIG-I. J. Mol. Biol. 2014;426:1351–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kell AM, Gale M. RIG-I in RNA virus recognition. Virology. 2015;479:110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hofmann K, Bucher P. The CARD domain: a new apoptotic signalling motif. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1997;22:155–156. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Park HH. Caspase recruitment domains for protein interactions in cellular signaling (Review) Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019;43:1119–1127. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sato H, Oshiumi H, Takaki H, Hikono H, Seya T. Evolution of the DEAD box helicase family in chicken: chickens have no DHX9 ortholog. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015;59:633–640. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gu T, Rao YL, Su JG, Yang CR, Chen XH, Chen LJ, Yan NN. Functions of MDA5 and its domains in response to GCRV or bacterial PAMPs. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015;46:693–702. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Baum A, Garcia-Sastre A. Induction of type I interferon by RNA viruses: cellular receptors and their substrates. Amino Acids. 2010;38:1283–1299. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0374-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Matsumiya T, Stafforini DM. Function and regulation of retinoic acid-inducible gene-I. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2010;30:489–513. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v30.i6.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Saito T, Hirai R, Loo YM, Owen D, Johnson CL, Sinha SC, Akira S, Fujita T, Gale M. Regulation of innate antiviral defenses through a shared repressor domain in RIG-I and LGP2. PNAS. 2007;104:582–587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen X, Yang C, Su J, Rao Y, Gu T. LGP2 plays extensive roles in modulating innate immune responses in Ctenopharyngodon idella kidney (CIK) cells. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2015;49:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rao Y, Wan Q, Yang C, Su J. Grass carp laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 serves as a negative regulator in retinoic acid-inducible gene I- and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5-mediated antiviral signaling in resting state and early stage of grass carp reovirus infection. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:352. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]