Abstract

Objective

Health-related research in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has grown over the years. However, concerns have been raised about the state of research ethics committees (RECs). This scoping review examines the literature on RECs for health-related research in SSA and identifies strategies that have been applied to strengthen the RECs. It focuses on three aspects of RECs: regulatory governance and leadership, administrative and financial capacity and technical capacity of members.

Design

A scoping review of published literature, including grey literature, was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute approach.

Data sources

BioOne, CINAHL, Embase (via Ovid), Education Abstracts, Global Health, Google Scholar, Jstor, OpenEdition (French), Philosopher’s Index, PsycINFO, PubMed, Science Citation and Expanded Index (Web of Science), reference lists of included studies and specific grey literature sources.

Eligibility criteria

We included empirical studies on RECs for health-related research in SSA, covering topics on REC leadership and governance, administrative and financial capacity and the technical capacity of REC members. We included studies published between 01 January 2000 and 18 February 2022 and written in English, French, Portuguese or Swahili.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two independent reviewers screened the records. Data were extracted by one reviewer and cross-checked by another. Owing to the heterogeneity of included studies, thematic analysis was used.

Results

We included 54 studies. The findings show that most RECs in SSA work under significant administrative and financial constraints, with few opportunities for capacity building for committee members. This has an impact on the quality of reviews and the overall performance of RECs. Although most countries have national governance systems for RECs, they lack regulations on accountability, transparency and monitoring of RECs.

Conclusions

This review provides a comprehensive overview of the literature on RECs for health-related research in SSA and contributes to our understanding of how RECs can be strengthened.

Keywords: MEDICAL ETHICS, International health services, Health & safety

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review uses a robust methodology, as proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute, to identify peer-reviewed papers and grey literature.

The review is limited to literature published between 01 January 2000 and 18 February 2022, in English, French, Portuguese or Swahili.

We found few studies that evaluated the effectiveness of measures taken to improve the ethical review of health-related research in sub-Saharan Africa.

Introduction

Health research in low-income and middle-income countries, which shoulders the greatest burden of disease, is critical to combat health inequity.1 Recognition of this burden in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has led to a growth in international collaborative research implemented in SSA funded mainly by the USA, UK, Germany and Japan. This has been crucial in establishing research governance in SSA.2 However, significant challenges remain3: international collaboration and external funding can skew priorities, external investigators may lack knowledge of the local context and local researchers may have limited exposure to research methodology and ethics training.4 In addition to these, sometimes gross ethical misconduct can occur.5–7 New and complex challenges are also emerging, such as research involving genetic and genomic analyses and the use of artificial intelligence in healthcare.8 9 These challenges are more serious in SSA, where research participants are likely to be vulnerable and less aware of their rights. Previous literature has identified the difficulty in adequately explaining complex genomic research methods, the risk of diagnostic misconception when recruiting healthy and unhealthy populations and the administration of informed consent in the context of low health and research literacy in African countries.7 10 Further to this, a recent survey on regulatory activities and ethical review in Africa in April 2020 found seven countries (Niger, Burkina Faso, Comoros, Togo, Guinea Bissau, Tanzania and Cote d’Ivoire) indicated that they do not have ethics review boards at universities or research institutes and most national regulatory authorities face resource constraints resulting in the lack of capacity for adequate review and approval of research. All these issues highlight the importance of strong research ethical review governance structures for health-related research in SSA, now more than ever, with the global impact of the pandemic resulting in outbreaks of several infectious diseases in SSA, making research into disease prevention and management crucial.11

Ethical reviews are conducted by boards commonly referred to as Institutional Review Boards, Research Ethics Committees (RECs) or Ethics Review Committees.12 The Declaration of Helsinki emphasises the importance of an independent and appropriately constituted REC that must have the authority to monitor ongoing studies, including any serious adverse events.13 Further, the review process should ensure that the interests of human participants are protected and that the research is ethically sound and relevant. While ethical and regulatory bodies in SSA are best placed to understand their local context and advise on how to conduct reviews, their capacity to do so may be limited by several factors. These factors include a lack of infrastructure (eg, information technology and office space), limited financial and administrative support, a small pool of REC members and regulators, a lack of theoretical training in ethics and regulatory affairs and weak governance structures.14 The concerns about ethical and regulatory issues, and the state of RECs in SSA, have persisted, despite various efforts to strengthen them. One example of this effort is the African Vaccine Regulatory Forum (AVAREF) which was established in 2006 by the WHO to serve as an informal capacity-building network to enhance the ethics and regulatory oversight of interventional clinical trials undertaken in Africa. Despite the AVAREF having demonstrated its value in strengthening regulatory and ethics reviews through promoting standards and approaches as well as accelerating the review of priority public health vaccines, literature has continued to identify constraints faced by RECs.15

A 2007 mapping of REC activity in Western and Central Africa reported limited information on existing committee structures.16–20 In 2009, the Mapping African Research Ethics Capacity (MARC) project was launched to understand the capacity of the network’s research institutions, to aid in the flow of information between the centres and to provide a public space for technical and strategic support for health research.21 22 There was a need to identify existing capacity, funding and areas where additional development would be beneficial. In 2012, this was seen to be lagging in terms of requirements, often due to a lack of resources and capacity.23 A 2015 systematic review focusing on the structure, functioning and outcomes of biomedical RECs in SSA found several factors impeding RECs’ work, including a lack of diversity in membership, limited resources, insufficient member training and a lack of national ethics guidelines and accreditation.24

This review builds on these previous efforts by applying a scoping review approach that provides an overview of the literature on health-related RECs in SSA and identifies strategies that have been applied to strengthen the RECs. We focus on three aspects of the RECs: the technical capacity of members, administrative and financial capacity and leadership and governance.

Methods

Search strategy

We applied the methodological approach proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute on how to extract, analyse and present results.25 This approach also aligns with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR).26 We initially conducted a preliminary search to refine the scope of the review, eligibility criteria for selecting the literature (table 1) and relevant online databases. The review included studies published from 01 January 2000. This start date was based on our preliminary search because most of the initiatives to improve RECs in SSA were after 2000. We included publications written in English, French, Portuguese or Swahili as these are some of the official languages in SSA and those that the authors were familiar with.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

| P—population | Research ethics committees (RECs) for health-related research in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. | RECs not focusing on health-related research and RECs outside SSA. Papers and material focusing on the ethics of individual research studies, including consent for specific empirical studies. |

| C—concept | Studies exploring the leadership and governance structures of RECs, the administrative and financial capacity; and the technical capacity of REC members to conduct ethical reviews. | Studies not focusing on the structure and capacity of RECs but focusing on the implementation of ethical practices in research such as informed consent and data storage as well as papers focusing on the ethics of individual research studies. |

| C—context | Studies focusing on SSA. | Studies outside SSA. |

| Type of publication | Publications using empirical data such as peer-reviewed journals, reports, discussions, theory papers, case studies, editorials and commentaries. | Publications not using empirical data such as opinion pieces. |

| Language | Publications written in English, French, Portuguese or Swahili. | Studies available in a language other than English, French, Portuguese or Swahili. |

| Time period | Published between 01 January 2000 and18 February 2022. | Pre-2000 and after 18 February 2022 |

We conducted structured searches of online health research-focused databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, Education Abstracts, Global Health, Google Scholar, Jstor, OpenEdition (French), Philosopher’s Index, PsycINFO and BioOne. Search terms were combined using Boolean and proximity operators and database subject headings such as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), were used: For example, the search string for PubMed was: ((ethic* committee* (title/abstract)) OR (ethics guidance (title/abstract)) OR (ethics review committee* (title/abstract)) OR (ethics regulation (title/abstract)) OR (research regulation (title/abstract)) OR (institutional review boards (title/abstract))) AND ((capacity development (title/abstract)) OR (capacity (title/abstract)) OR (governance (title/abstract)) OR (leadership (title/abstract))) AND (health OR medical (title/abstract)) AND (sub Saharan Africa (MeSH Terms)) AND ((English (Language) OR French (Language) OR Portuguese (Language) OR Swahili (Language))) AND ((‘2000’ (Date—Publication): ‘2022’ (Date—Publication))). Search strings for all databases are available in the supplementary file, online supplemental appendix A. We also hand-searched websites of relevant organisations to identify grey literature: the Council on Health Research for Development (https://www.cohred.org), WHO Regional Office for Africa/Integrated African Health Observatory (https://aho.afro.who.int), Pan African Bioethics Initiative (PANBIN) (http://www.who.int/sidcer/fora/pabin/en) and MARC (https://ahrecs.com/resources/mapping-africa-research-ethics-capacity-marc). The end date of the search was 18 February 2022.

bmjopen-2022-062847supp001.pdf (112.5KB, pdf)

Screening and data extraction

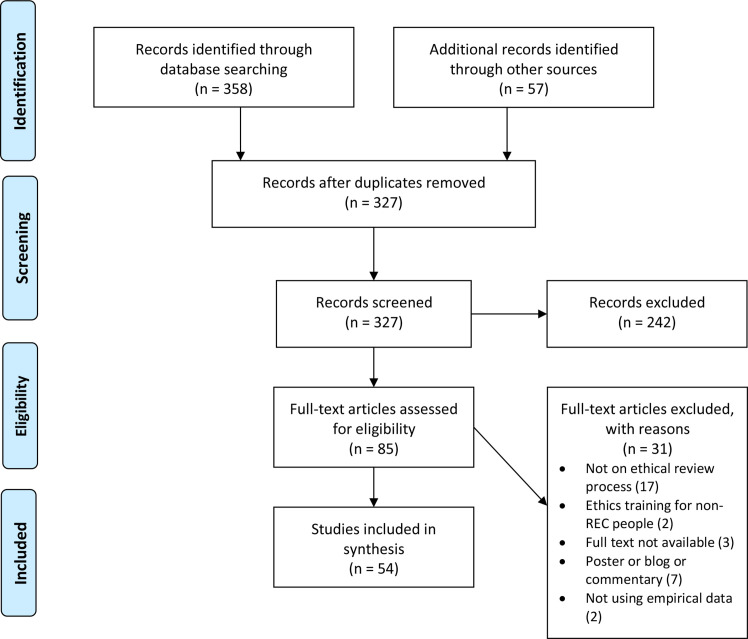

As per the PRISMA-ScR guidelines, we first screened the titles and abstracts of papers identified by the search (excluding duplicates) and then the full texts of papers that met the eligibility criteria. Two authors (VT and DP) conducted the screening independently. When there were disagreements, another author (AJML) was involved. We also searched the references of the included papers. Abstracts and full texts of additional papers identified were screened in the same manner. We identified 54 papers that were included in the review (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis; REC, research ethics committee.

We extracted data from the included papers on publication type, country, study objectives, study design, methods and findings on RECs (technical capacity, administrative and financial capacity and leadership and governance). Lastly, owing to the heterogeneity of the included papers in terms of study designs and methods, we used thematic analysis.27 Papers were imported into NVivo V.12, software for analysis of qualitative and mixed-method studies. The data from these papers were coded according to the REC themes stated above. The coding was done by one author (IC) and reviewed by another author (DP), and all authors contributed to identifying the subthemes. The scoping review protocol has been peer-reviewed and published.28 We extended the time period to 18 February 2022; in the protocol, it was October 2020. Additionally, we included studies that examined international collaborations with SSA countries and multicountry studies if the findings were relevant to SSA. This was not clearly explained in the protocol. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Patient and public involvement

None.

Results

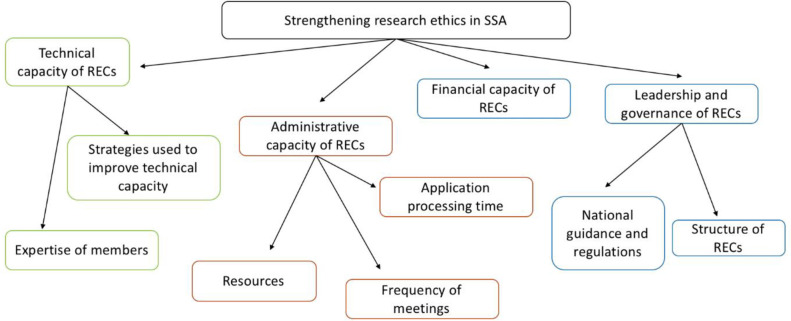

We identified four key themes (figure 2). The most common theme was technical capacity, examined by 43 papers, while financial capacity was examined by only 19 papers. The included papers are summarised in the supplementary file (online supplemental appendix B).

Figure 2.

Thematic map. RECs, research ethics committees; SSA, sub-Saharan Africa.

Technical capacity of RECs

The quality of reviews depended on the technical capacity of reviewers, that is, the expertise of REC members and strategies used to improve their technical capacity.

Expertise of members

Across studies at national and institutional levels, there are attempts at recruiting members with a high level of education or expertise in health research. Most SSA countries employ members such as scientists, physicians and statisticians.14 29–33 Some additionally involve other professionals such as lawyers and legal advisers,14 30 32 and a few also include lay members to ‘represent the cultural and moral values of the community’32 and who serve as ‘community gatekeepers and shape community attitudes towards research’.34 Two countries (South Africa and Nigeria) also include consumer groups or faith-based organisations.14 29

The capacity of RECs to conduct reviews also depends on the overall number of members in RECs. The average number of members per committee differed within and between countries. For example, in Nigeria, the number of members of the Health Research Ethics Committee (HREC) ranged from 9 to 15.35 Similarly, in South Africa, the University of Witwatersrand’s REC had only three members, whereas the University of Pretoria, Medical University of South Africa, had nine members.33 36

Challenges of recruiting and retaining members included high workloads, especially as REC activities are considered additional duties and there is a lack of compensation for attending REC meetings and for conducting reviews.22 37–41 Further, there are no rewards, incentives or academic acknowledgements for committee members participating in REC meetings and training.38–42 Only one study from Ethiopia identified benefits for academic staff working in institutional RECs, who could ‘theoretically’ request ‘research leave’ of up to 4 months to conduct their research in lieu of REC work.31 These challenges in recruiting and retaining members were also found to impact the quality of reviews which were reported as poor in most SSA. The primary reasons were related to poor administrative capacity, but ‘lack of adequate time and attention devoted to review tasks’ was also identified as a problem.40

Strategies used to improve technical capacity

Some studies blamed the poor quality of reviews on the REC governance that ‘did not train their staff in study related aspects’; therefore, some staff ‘had very little knowledge of research ethics and ignorance particularly about the…National Guidelines’.39 Most studies identified the training and education of members as critical to improving the technical capacity to conduct reviews.43–48 Understanding research ethics regulations and the ability to evaluate reviews were identified as two areas where training was required. Benefits of training such as better quality of reviews and reduced review processing times were commonly seen at the institutional RECs that implement strategies such as ethics workshops or trainings.23 33 34 49–53 Despite recognising the need for training, the quality of training and the number of training opportunities were largely ‘inconsistent’ across and within RECs.37 44 49 A study in Guinea also recommended that multiple ethical reviews, where a study is reviewed by the RECs in the countries where the study is being carried out and in the countries of the sponsor and research partners, should be routinely implemented for externally-funded trials to improve the quality of reviews.54

Financial capacity of RECs

Many RECs have inadequate financial resources, with institutional RECs facing greater financial challenges as they are considered a low priority within institutions.33 46 55 Many institutional RECs rely on fees charged for reviewing research protocols,29–31 33 35 36 50 56–58 but this is not adequate. One review across nine SSA countries found that ‘three out of twelve REC had no operating funds whatsoever’.37

In contrast, many national RECs receive funding from the government, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or foreign agencies.37 51 59 60 However, many studies also reported that receiving funding from different sources, national and international, has challenges and can raise concerns about conflict of interest. ‘Many reviewers are not aware of more subtle conflicts—they could be influenced by the prospect of more international recognition of a participating institution, the arrival of world-renowned experts and other indirect benefits”.61

Administrative capacity of RECs

The administrative capacity of RECs to follow and document ethical review processes depends on their workload, organisation and resources.

Application processing time

Time to process ethics applications varied across and within countries, ranging from 10 days to 12 weeks.35 37 39 46 50 62 The high workload of REC members was found to be the biggest reason for these delays, as REC members typically hold more than one job and have multiple responsibilities.33

Frequency of meetings

The frequency of REC meetings is inconsistent across and within countries, with national REC meetings taking place on average once a month and institutional REC meetings taking place once every 2–3 weeks. This was sometimes because of unclear guidance or lack of clarity in the standard operating procedures.30 32 35 39 62 63 However, many studies also reported that a lack of member incentives makes it difficult to hold meetings regularly. In Nigeria, HREC meetings were held ‘only occasionally’ because of the ‘competing interests of members, who receive no incentives for participation’.35 The number of study protocols reviewed in the meetings also varied substantially. Kass, covering nine SSA countries, found that three RECs reviewed 8–12 protocols per year, three reviewed 30–50, five reviewed 100–250 and one reviewed 600 per year.37

Resources

The lack of resources was another reason for the poor administrative capacity of REC. In most SSA, RECs have limited resources for maintaining documents relating to ethics reviews.39 48 55 64–69 “Many did not have access to dedicated office spaces or resources to conduct meetings/support ethics reviews’.42 70 For improving the functioning of REC, ‘budgets, office space and adequate equipment’ are essential ‘to enable sustainable and efficient service to the research community’.68

Leadership and governance

The leadership and governance of RECs are reflected in the national guidance and regulations and the structure of RECs.

National guidance and regulations

The majority (60%) of the countries have ‘some national ethics guidance, either in the form of laws, regulations, codes, guidelines or standard operating procedures’.71 Institutions have largely established their own structures despite following national guidance.42 64 72 73

Most countries also attempt to use international guidelines and regulations, namely, the Declaration of Helsinki, the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research involving Human Subjects and guidelines from the WHO.43 53 57 74 In Botswana, for example, the Human Resource Development Council (HRDC) is guided by principles articulated in the Helsinki Declaration and the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research involving Human Subjects (HBS) of the Council for International Organisations of Medical Sciences. Until recently, regulatory guidance on HBS was only available for clinical trials related to drug applications. The Ministry of Health issued Standard Operating Procedures in 2011 to guide the structure and operation of the HRDC and the review of research protocols at institutional and national levels.62 Similarly, in Nigeria, the National HREC, established in 2006, is empowered by regulations and the National Health Act, thereby having clear Terms of Reference that states its role in registering and auditing the work of institutional RECs.38

A survey exploring the training needs in research ethics evaluation among RECs in Cameroon, Mali and Tanzania found that ‘52.7% of respondents reported that they have no difficulty’ in applying ethics regulation guidance at national and institutional (local) levels, ‘whereas 47.3% reported having some difficulties concerning adaptation to local context, interpretation difficulties, difficulties applying to particular context and discrepancy with local regulations’.64 Guidance documents that were reported to be followed were from the following regulations: Declaration of Helsinki, CIOMS Guidelines, The Nuremberg Code, The Belmont Report, Guidelines of the Medical Research Coordinating Committee, Tanzania, National constitutions, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, ‘Declaration droit de malade’ and others.64 The survey also identified the need for developing laws and guidelines adapted to the local context to avoid discrepancies in international guidelines that do not fit in with local norms.75

Most countries have a national authority within the Ministry of Health that is responsible for setting up national guidance. However, the structure and mandate of the national authority vary across countries.21 57 61 Many are ‘not legally constituted hence lack official recognition and a legal framework to support the establishment’.21 Therefore, in cases of fraud or research misconduct, these authorities may lack the power to take legal action. One study highlighted the need for greater accountability, transparency and monitoring of RECs to mitigate the ‘unfortunate possibility of REC members becoming corrupted (bribed)’.61 Monitoring of RECs is also important for building trust, as a study reported that ‘some (scientists) believe that members of the committee will plagiarise their ideas during the review process’.76

Structure of RECs

There was less literature discussing the management structure of RECs, and most were limited to describing the expertise and designation of people who headed the committees, which greatly varies across countries. In most cases, RECs are ‘headed by a medical doctor’ or ‘scientist or health-related professional’, and they tend to have ‘some personal experience pertaining to the conduct of research’.59

Discussion

We found that RECs in SSA work under significant administrative and financial constraints, with limited capacity-building opportunities and support available to committee members. This affects the quality of reviews and the overall performance of RECs. There is little evidence on the impact of strategies used for improving their performance, whether through training REC members, using software to improve administrative efficiency or establishing clear standard operating protocols.

Many of the challenges faced by RECs have knock-on effects on other aspects.33 For example, reviewers’ workloads can compound administrative challenges relating to the regularity of REC meetings. However, administrative efficiency can be improved by using softwares as is done in most high-income countries (HICs), such as the Research for Health and Innovation Organiser (RHInnO Ethics), which serves as an information management and expert-decision support system for individual RECs. RHInnO Ethics is currently installed in 29 RECs in eight African countries and has been shown to improve review quality, efficiency and standardisation.13 A similar REC management tool is Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), which helps REC members to review projects anywhere online securely. REDCap has been found to increase the number of projects completed and reduce the time required for completion at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, where it was first used.77 This highlights the importance of encouraging RECs in SSA to invest in and use management systems to address current administrative challenges, particularly in institutional RECs.

The technical ability of REC members was also assessed across countries, and differences were observed in levels of training and experience. Overall, the technical ability of members was found to vary between national and institutional RECs. This could be the reason for the differences in the quality of reviews and the overall performance of national and institutional RECs. A 2015 review focusing on the structure, functioning and outcomes of biomedical RECs in SSA discovered several factors impeding REC work, including a lack of diversity in membership, a scarcity of resources, insufficient member training, insufficient capacity to review and monitor studies and a lack of national ethics guidelines and accreditation; supporting claims that the body of evidence on health-related RECs in SSA is still fragmented.20–22 24 78

RECs work under severe financial constraints. Most countries have inadequate financial resources at the institutional level, as they are considered low priority. This contrasts with funding available to the national RECs that receive funds from pre-allocated research budgets from the government, NGOs or other foreign funding agencies. This is similar to funding available in HICs such as in the UK where RECs such as the Royal College of Physicians, the Nuffield Trust and the unofficial Clinical Ethics Network receive financial support from the Department of Health of England.79 SSA countries’ lower Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rates are one of the primary reasons for the lower funding budgets and allocations received by RECs as compared with HICs.80 As a result, financial and resource support from HIC donors is needed to improve the resources and financial capacity of RECs in SSA. This may be through donations of old technical equipment, sponsoring training workshops or supporting the development of standard operating processes. A review has previously indicated that the US funding for biomedical RECs in SSA helped improve their structure, functioning and outcome.4 However, international collaboration and external funding can skew national priorities4 and cause a conflict of interest at national and institutional RECs.61 Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge that foreign funding is usually used for short-term support for RECs, highlighting the need for stronger governance and regulation of RECs with long-term sustainability.51

Leadership and governance for ethics and research were found to exist on two levels in most countries: institutional and national. Despite adhering to national guidelines, institutions were found to have largely established and maintained their own RECs. National RECs were also found to follow their own countries’ recommended guidelines. Many countries promote and implement international guidelines and regulations such as the Declaration of Helsinki. These guidelines emphasise the importance of independent and appropriately constituted RECs13 18 and that each committee’s operation must be transparent and independent of the researcher, the sponsor and any other undue influence. However, most countries still lack national guidance and regulations concerning accountability, transparency and monitoring of RECs.

RECs in SSA should consider using the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki (1964, updated in 2013) and the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (2016) guidelines as recommended by the WHO. These guidelines are viewed as tools that promote ethical standards through appropriate systems of review for any course of research. By applying these guidelines, SSA’s RECs can promote research of the highest ethical standards.33 71

Strengths and limitations of the review

This review advances our understanding of how RECs can be strengthened in SSA, a topic that has not received much attention despite increased health-related research in SSA. We applied a comprehensive search strategy that included a broad range of studies. However, there are a few limitations. The review included studies from 01 January 2000 until 18 February 2022 and only those published in English, French, Portuguese or Swahili. We did not exclude studies because of poor quality. The findings on administrative capacity are primarily based on qualitative studies and self-reported responses, and many studies did not use validated tools to measure administrative outcomes. Furthermore, few studies evaluated the effectiveness of measures taken to improve the ethical review of health-related research.

Conclusion

Most RECs in SSA face considerable administrative and financial constraints, with limited opportunities for capacity building of their members. This has an impact on the quality of reviews and the overall performance of RECs. To support RECs in SSA, more research is needed on the type of applications reviewed by RECs. This will also help to understand the training gaps for REC members.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AJML, DP and VT were responsible for the study concept and design. AJML, DP, IC and VT identified the papers and conducted the thematic analysis, IC wrote the first draft, while all authors (AJML, DP, EF, HW, IC, MS, VT) contributed to identifying the themes and drafting the manuscript. DP is the guarantor of the study and attests that all listed authors meet the authorship criteria and have agreed to publish this paper.

Funding: This work was supported by the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP), grant number CSA2018ERC-2330.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Bryant JH, Harrison PF. Health research: essential link to equity in development, in Global Health in Transition: A Synthesis: Perspectives from International Organizations. National Academies Press (US), 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ndebele P, Wassenaar D, Benatar S, et al. Research ethics capacity building in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of NIH Fogarty-funded programs 2000–2012. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2014;9:24–40. 10.1525/jer.2014.9.2.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alemayehu C, Mitchell G, Nikles J. Barriers for conducting clinical trials in developing countries- a systematic review. Int J Equity Health 2018;17:1–11. 10.1186/s12939-018-0748-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward CL, Shaw D, Sprumont D, et al. Good collaborative practice: reforming capacity building governance of international health research partnerships. Global Health 2018;14:1–6. 10.1186/s12992-017-0319-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ezeome ER, Simon C. Ethical problems in conducting research in acute epidemics: the pfizer meningitis study in Nigeria as an illustration. Dev World Bioeth 2010;10:1–10. 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2008.00239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Zulueta P. Randomised placebo-controlled trials and HIV-infected pregnant women in developing countries. ethical imperialism or unethical exploitation? Bioethics 2001;15:289–311. 10.1111/1467-8519.00240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mweemba O, Musuku J, Mayosi BM, et al. Use of broad consent and related procedures in genomics research: perspectives from research participants in the genetics of rheumatic heart disease (RHDGen) study in a university teaching hospital in Zambia. Global Bioethics 2020;31:184–99. 10.1080/11287462.2019.1592868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahl B, Cossy-Gantner A, Germann S, et al. Artificial intelligence (AI) and global health: how can AI contribute to health in resource-poor settings? BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000798. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansson MG, Dillner J, Bartram CR, et al. Should donors be allowed to give broad consent to future biobank research? Lancet Oncol 2006;7:266–9. 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70618-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mbuagbaw L, Thabane L, Ongolo-Zogo P, et al. The challenges and opportunities of conducting a clinical trial in a low resource setting: the case of the cameroon mobile phone SMS (camps) trial, an investigator initiated trial. Trials 2011;12:1–7. 10.1186/1745-6215-12-145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wamai RG. The Future of Health in Sub-Saharan Africa: Is There a Path to Longer and Healthier Lives for All? In: African futures. Brill, 2022: 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemminki E. Research ethics committees in the regulation of clinical research: comparison of Finland to England, Canada, and the United States. Health Res Policy Syst 2016;14:5. 10.1186/s12961-016-0078-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Medical Association . World Medical association declaration of helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yakubu A, Adebamowo CA. Implementing national system of health research ethics regulations: the Nigerian experience. BEOnline 2012;1:4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akanmori B, Mukanga D, Bellah A, et al. The role of the African vaccine regulatory forum (AVAREF) in the accelerated clinical evaluation of Ebola vaccine candidates during the large West Africa epidemic. J Immunol Sci 2018;2:75–9. 10.29245/2578-3009/2018/si.1111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kombe F, Toohey J, Ijsselmuiden C. Research ethics capacity building for the next decade – ‘beyond training’ – rhinno ethics as model to improve and accelerate ethics review of health research. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:A55.2–A55. 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000260.147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chatfield K, Schroeder D, Guantai A, et al. Preventing ethics dumping: the challenges for Kenyan research ethics committees. Res Ethics 2021;17:23–44. 10.1177/1747016120925064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novoa-Heckel G, Bernabe R, Linares J. Exportation of unethical practices to low and middle income countries in biomedical research. Rev Bioetica & Derecho 2017;40:167. 10.1344/rbd2017.40.19170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroeder D, et al. Ethics dumping and the need for a global code of conduct, in equitable research partnerships. Springer, 2019: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zielinski C, Kebede D, Mbondji PE, et al. Research ethics policies and practices in health research institutions in sub-Saharan African countries: results of a questionnaire-based survey. J R Soc Med 2014;107:70–6. 10.1177/0141076813517679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.COHRED . Strengthening research and innovation systems for health and development in Africa: report from a Tanzania knowledge-sharing workshop, in research for health Africa. Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania: COHRED, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mokgatla B, IJsselmuiden C, Wassenaar D, et al. Mapping research ethics committees in Africa: evidence of the growth of ethics review of health research in Africa. Dev World Bioeth 2018;18:341–8. 10.1111/dewb.12146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali J, Hyder AA, Kass NE. Research ethics capacity development in Africa: exploring a model for individual success. Dev World Bioeth 2012;12:55–62. 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2012.00331.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aidam J, Sombié I. The West African Health Organization’s experience in improving the health research environment in the ECOWAS region. Health Res Policy Syst 2016;14:1–11. 10.1186/s12961-016-0102-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.JBI . JBI Reviewers’ Manual Scoping Reviews; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1–9. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis; 2012.

- 28.Thurtle V, Leather AJ, Wurie H, et al. Strengthening ethics committees for health-related research in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2021;11:e046546. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dada MA, Moorad R. A review of a South African research ethics committee. Issues Med Ethics 2001;9:58–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falusi AG, Olopade OI, Olopade CO. Establishment of a standing ethics/institutional review board in a Nigerian university: a blueprint for developing countries. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2007;2:21–30. 10.1525/jer.2007.2.1.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaym A. Health research in Ethiopia--past, present and suggestions on the way forward. Ethiop Med J 2008;46:287–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirigia JM, Wambebe C, Baba-Moussa A. Status of national research bioethics committees in the who African region. BMC Med Ethics 2005;6:1–7. 10.1186/1472-6939-6-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moodley K, Myer L. Health research ethics committees in South Africa 12 years into democracy. BMC Med Ethics 2007;8:1–8. 10.1186/1472-6939-8-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Folayan MO, Adaranijo A, Durueke F, et al. Impact of three years training on operations capacities of research ethics committees in Nigeria. Dev World Bioeth 2014;14:1–14. 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2012.00340.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agunloye AM, Salami AT, Lawan A. Current role of research ethics committees in health research in three geopolitical zones in Nigeria: a qualitative study. S Afr J Bioeth Law 2014;7:19–22. 10.7196/sajbl.309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cleaton-Jones P. Applications and secretariat workload at the university of the witwatersrand human research ethics committee (medical) 2002-2011: a case study. S Afr J bioeth law 2012;5:38–44. 10.10520/EJC122379 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kass NE, Hyder AA, Ajuwon A, et al. The structure and function of research ethics committees in Africa: a case study. PLoS Med 2007;4:e3. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nyika A, Kilama W, Chilengi R, et al. Composition, training needs and independence of ethics review committees across Africa: are the gate-keepers rising to the emerging challenges? J Med Ethics 2009;35:189–93. 10.1136/jme.2008.025189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ochieng J, Ecuru J, Nakwagala F, et al. Research site monitoring for compliance with ethics regulatory standards: review of experience from Uganda. BMC Med Ethics 2013;14:1–7. 10.1186/1472-6939-14-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ouwe Missi Oukem-Boyer O, Munung NS, Tangwa GB. Small is beautiful: demystifying and simplifying standard operating procedures: a model from the ethics review and consultancy committee of the cameroon bioethics initiative. BMC Med Ethics 2016;17:1–10. 10.1186/s12910-016-0110-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rwabihama J-P, Girre C, Duguet A-M. Ethics committees for biomedical research in some African emerging countries: which establishment for which independence? A comparison with the USA and Canada. J Med Ethics 2010;36:243–9. 10.1136/jme.2009.033142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ikingura JKB, Kruger M, Zeleke W. Health research ethics review and needs of institutional ethics committees in Tanzania. Tanzan Health Res Bull 2007;9:p. 154–158. 10.4314/thrb.v9i3.14320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richard W, et al. Enhanced rec collaborative review through videoconferencing. S Afr J bioeth law 2016;9. 10.7196/SAJBL.2016.v9i2.483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mielke J, Ndebele P. Making research ethics review work in Zimbabwe--the case for investment in local capacity. Cent Afr J Med 2004;50:115-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogunrin O, Taiwo F, Frith L. Genomic literacy and awareness of ethical guidance for genomic research in sub-Saharan Africa: how prepared are biomedical researchers? J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2019;14:78–87. 10.1177/1556264618805194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ssali A, Poland F, Seeley J. Experiences of research ethics committee members and scientists of the research protocol review process in Uganda: a case study. Int Health 2020;12:541–2. 10.1093/inthealth/ihaa047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choko AT, Roshandel G, Conserve DF, et al. Ethical issues in cluster randomized trials conducted in low- and middle-income countries: an analysis of two case studies. Trials 2020;21:314. 10.1186/s13063-020-04269-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cleaton-Jones P, Vorster M. Workload of a South African university-based health research ethics committee in 2003 and 2007. S Afr J bioeth law 2008;1:38–43. 10.7196/sajbl.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.IJsselmuiden C, Marais D, Wassenaar D, et al. Mapping African ethical review committee activity onto capacity needs: the mARC initiative and HRWeb's interactive database of RECs in Africa. Dev World Bioeth 2012;12:74–86. 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2012.00325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ndebele P, Wassenaar D, Benatar S, et al. Research ethics capacity building in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of NIH fogarty-funded programs 2000–2012. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2014;9:24–40. 10.1525/jer.2014.9.2.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Silaigwana B, Wassenaar D. Biomedical research ethics committees in sub-Saharan Africa: a collective review of their structure, functioning, and outcomes. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2015;10:169–84. 10.1177/1556264615575511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Effa P, Massougbodji A, Ntoumi F, et al. Ethics committees in Western and central Africa: concrete foundations. Dev World Bioeth 2007;7:136–42. 10.1111/dewb_172.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Langlois A. The UNESCO universal declaration on bioethics and human rights: perspectives from Kenya and South Africa. Health Care Anal 2008;16:39–51. 10.1007/s10728-007-0055-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Crop M, Delamou A, Griensven JV, et al. Multiple ethical review in north-south collaborative research: the experience of the ebola-Tx trial in guinea. Indian J Med Ethics 2016;1:76-82. 10.20529/IJME.2016.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Noormahomed EV, Mocumbi AO, Preziosi M, et al. Strengthening research capacity through the medical education partnership initiative: the mozambique experience. Hum Resour Health 2013;11:62. 10.1186/1478-4491-11-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andanda P, Awah P, Ndebele P, et al. The ethical and legal regulation of HIV-vaccine research in Africa: lessons from cameroon, Malawi, Nigeria, Rwanda and Zambia. Afr J AIDS Res 2011;10:451–63. 10.2989/16085906.2011.646660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barchi F, Matlhagela K, Jones N, et al. “The keeping is the problem”: a qualitative study of IRB-member perspectives in botswana on the collection, use, and storage of human biological samples for research. BMC Med Ethics 2015;16:1–11. 10.1186/s12910-015-0047-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geldenhuys H, Veldsman A, Tameris M, et al. Analysis of time to regulatory and ethical approval of SATVI TB vaccine trials in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2013;103:85–8. 10.7196/SAMJ.6390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sombié I, Aidam J, Konaté B, et al. The state of the research for health environment in the ministries of health of the economic community of the West African states (ECOWAS). Health Res Policy Syst 2013;11:1–11. 10.1186/1478-4505-11-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sombié I, Aidam J, Montorzi G. Evaluation of regional project to strengthen National health research systems in four countries in West Africa: lessons learned. Health Res Policy Syst 2017;15:89–99. 10.1186/s12961-017-0214-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klinkenberg E, Assefa D, Rusen ID, et al. The Ethiopian initiative to build sustainable capacity for operational research: overview and lessons learned. Public Health Action 2014;4:2–7. 10.5588/pha.14.0051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feleke Y, Addissie A, Wamisho BL, et al. Review paper on research ethics in Ethiopia: experiences and lessons learnt from addis ababa university college of health sciences 2007-2012. Ethiop Med J 2015;53 Suppl 1:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silverman H, Sleem H, Moodley K, et al. Results of a self-assessment tool to assess the operational characteristics of research ethics committees in low- and middle-income countries. J Med Ethics 2015;41:332–7. 10.1136/medethics-2013-101587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ateudjieu J, Williams J, Hirtle M, et al. Training needs assessment in research ethics evaluation among research ethics committee members in three African countries: Cameroon, Mali and Tanzania. Dev World Bioeth 2010;10:88–98. 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2009.00266.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klitzman R. Views of the process and content of ethical reviews of HIV vaccine trials among members of US institutional review boards and South African research ethics committees. Dev World Bioeth 2008;8:207–18. 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Vries J, Munung SN, Matimba A, et al. Regulation of genomic and biobanking research in Africa: a content analysis of ethics guidelines, policies and procedures from 22 African countries. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18:8. 10.1186/s12910-016-0165-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yakubu AA. Research ethics committees in Nigeria: a survey of operations, functions, and needs. In: IRB ethics and human research. 39, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kasule M, Wassenaar DR, IJsselmuiden C, et al. Silent voices: current and future roles of African research ethics committee administrators. IRB 2016;38:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ochieng J, Mwaka E, Kwagala B, et al. Evolution of research ethics in a low resource setting: a case for Uganda. Dev World Bioeth 2020;20:50–60. 10.1111/dewb.12198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Milford C, Wassenaar D, Slack C. Resources and needs of research ethics committees in Africa: preparations for HIV vaccine trials. In: IRB: Ethics & Human Research. 28, 2006: 1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barchi F, Little MT. National ethics guidance in sub-Saharan Africa on the collection and use of human biological specimens: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2016;17:1–25. 10.1186/s12910-016-0146-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sacarlal J, Muchanga V, Mabutana C, et al. Research ethics review at University Eduardo Mondlane (UEM)/Maputo central hospital, mozambique (2013–2016): a descriptive analysis of the start-up of a new research ethics committee (REC). BMC Med Ethics 2018;19:1–10. 10.1186/s12910-018-0291-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Staunton C, Moodley K. Challenges in biobank governance in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Med Ethics 2013;14:1–8. 10.1186/1472-6939-14-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Silaigwana B, Wassenaar D. Research ethics committees' oversight of biomedical research in South Africa: a thematic analysis of ethical issues raised during ethics review of non-expedited protocols. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2019;14:107–16. 10.1177/1556264618824921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Henderson GE, Corneli AL, Mahoney DB, et al. Applying research ethics guidelines: the view from a sub-Saharan research ethics committee. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2007;2:41–8. 10.1525/jer.2007.2.2.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ajuwon AJ, Kass N. Outcome of a research ethics training workshop among clinicians and scientists in a Nigerian university. BMC Med Ethics 2008;9:1. 10.1186/1472-6939-9-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Klipin M, Mare I, Hazelhurst S, et al. The process of installing REDCap, a web based database supporting biomedical research: the first year. Appl Clin Inform 2014;5:916–29. 10.4338/ACI-2014-06-CR-0054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gooding K, Newell JN, Emmel N. Capacity to conduct health research among NGOs in Malawi: diverse strengths, needs and opportunities for development. PLoS One 2018;13:e0198721. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Williamson L, McLean S, Connell J. Clinical ethics committees in the United Kingdom: towards evaluation. Med Law Int 2007;8:221–37. 10.1177/096853320700800302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Acharya KP, Pathak S. Applied research in low-income countries: why and how? Front Res Metr Anal 2019;4:3. 10.3389/frma.2019.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-062847supp001.pdf (112.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.