ABSTRACT

Tracking the metabolic activity of whole soil communities can improve our understanding of the transformation and fate of carbon in soils. We used stable isotope metabolomics to trace 13C from nine labeled carbon sources into the water-soluble metabolite pool of an agricultural soil over time. Soil was amended with a mixture of all nine sources, with one source isotopically labeled in each treatment. We compared changes in the 13C enrichment of metabolites with respect to carbon source and time over a 48-day incubation and contrasted differences between soluble sources (glucose, xylose, amino acids, etc.) and insoluble sources (cellulose and palmitic acid). Whole soil metabolite profiles varied singularly by time, while the composition of 13C-labeled metabolites differed primarily by carbon source (R2 = 0.68) rather than time (R2 = 0.07), with source-specific differences persisting throughout incubations. The 13C labeling of metabolites from insoluble carbon sources occurred slower than that from soluble sources but yielded a higher average atom percent (atom%) 13C in metabolite markers of biomass (amino acids and nucleic acids). The 13C enrichment of metabolite markers of biomass stabilized between 5 and 15 atom% 13C by the end of incubations. Temporal patterns in the 13C enrichment of tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates, nucleobases (uracil and thymine), and by-products of DNA salvage (allantoin) closely tracked microbial activity. Our results demonstrate that metabolite production in soils is driven by the carbon source supplied to the community and that the fate of carbon in metabolites do not generally converge over time as a result of ongoing microbial processing and recycling.

IMPORTANCE Carbon metabolism in soil remains poorly described due to the inherent difficulty of obtaining information on the microbial metabolites produced by complex soil communities. Our study demonstrates the use of stable isotope probing (SIP) to study carbon metabolism in soil by tracking 13C from supplied carbon sources into metabolite pools and biomass. We show that differences in the metabolism of sources influence the fate of carbon in soils. Heterogeneity in 13C-labeled metabolite profiles corresponded with compositional differences in the metabolically active populations, providing a basis for how microbial community composition correlates with the quality of soil carbon. Our study demonstrates the application of SIP-metabolomics in studying soils and identifies several metabolite markers of growth, activity, and other aspects of microbial function.

KEYWORDS: metabolomics, stable isotope probing, soil carbon cycle, community metabolism

INTRODUCTION

Modeling the pathways that carbon takes through soil remains a complex problem because of the numerous interacting physicochemical and biological variables that regulate its transformation and fate. One barrier to understanding the fate of soil carbon is our limited capacity to track the dynamic processing of carbon within soil microbial communities. The transformation of carbon via microbial metabolism impacts the residency time of carbon in soil (1), in part due to changes in metabolite pools over time (2–5). Yet, the mechanisms that mediate these carbon transformations remain poorly described, due to the inherent difficulty of obtaining information on the microbial metabolites produced by complex soil communities.

Stable isotope probing (SIP) can be used to study the carbon metabolism of active microbial populations in soil by tracking 13C from supplied carbon sources into metabolite pools and biomass. Reconstructions of metabolic potential of active populations have been made from metagenome-assembled genomes with DNA-SIP (6) and from 13C-labeled proteins using SIP-metaproteomics (7, 8). SIP has been used to quantify the persistence of microbial biomass carbon in soil food webs by tracking 13C into lipids, amino acids, and carbohydrates (9, 10). The quantification of 13C in whole metabolite pools (i.e., SIP-metabolomics) has been used to study amino acid turnover in soil (11), in contrast with studying the metabolism of glucose in oxic and anoxic soils (12), as well as in other applications (13, 14). Here, we used SIP-metabolomics to examine community metabolism with respect to nine carbon sources that are common to soils. We did this by tracking the 13C enrichment dynamics of metabolites derived from each 13C-labeled carbon source (‘13C-metabolite profiles’).

The catalytic transformation of carbon in soil is governed by the metabolic capabilities and life history traits (i.e., growth rate, motility, morphology, etc.) represented in the soil microbial community. Life history traits can have a greater influence over which populations metabolize common sources of soil carbon than their metabolic capacity alone (i.e., potential metabolic pathways for carbon transformation). Traits are primarily a function of growth dynamics and the bioavailability of a carbon source, where fast-growing bacteria dominate for access to soluble sources (15). In addition, the biosynthetic pathways that produce cell biomass are highly conserved, and so the growth, death, and recycling of cell biomass might be expected to homogenize community metabolite pools over time regardless of carbon source (16). Accordingly, the composition of 13C-metabolite pools in soils might vary more by time than by carbon source over the course of months.

We studied soil carbon metabolism by tracing 13C derived from nine isotopically labeled carbon sources into the water-soluble soil metabolite pool across 48 days, using samples previously analyzed in a DNA-SIP study (15). The carbon sources were cellulose (plant cell walls), glucose and xylose (abundant carbohydrates in soil), vanillin (a by-product of lignin degradation), glycerol and palmitic acid (components of plant lipids), a mix of amino acids, and lactate and oxalate (microbial fermentation products). We expected underlying differences in the metabolism of each source to be less important than the influence of growth dynamics, and we hypothesized that 13C-metabolite profiles would vary primarily with respect to time rather than carbon source. We hypothesized that any initial variation in 13C-metabolite profiles among carbon sources, due to differences in the composition of metabolically active bacterial populations or differences in entry points into central metabolism, would disappear over time as carbon was recycled through common pathways. We also hypothesized that 13C-metabolite profiles would differ between soluble (e.g., glucose, xylose, amino acids, etc.) and insoluble carbon sources (cellulose and palmitic acid) due to the temporal dynamics of colonizing and degrading insoluble carbon sources (17, 18). Finally, we examined the chemodiversity and persistence of 13C-enriched metabolites over time to provide an account of the in vivo microbial community metabolism of soil carbon.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We profiled the community metabolism of nine 13C-labeled carbon sources in soil by measuring the 13C enrichment of water-extractable metabolites. Carbon sources were chosen to represent a range of compound classes common in soil, and they were selected to vary widely in solubility and bioavailability (15). A total of 2,003 features and 138 metabolites were identified using untargeted and targeted approaches, respectively. Of the total 138 metabolites, 69 yielded sufficiently interference-free m/z spectra to calculate the atom percent (atom%) 13C (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Most of the 13C-labeled metabolites belonged to central pathways involved in amino acid synthesis or catabolism (n = 23) and DNA synthesis (n = 10). Fifteen 13C-labeled metabolites corresponded to the carbon sources that were added, namely, 14 amino acids and vanillin, and were enriched on day 1. A total of 67 metabolites exhibited significant 13C enrichment relative to 12C controls for at least a single carbon source, while 57 exhibited 13C enrichment on five or more sources and 34 were 13C enriched in every metabolite profile (Table S4).

Patterns in 13C-metabolites by carbon source and time.

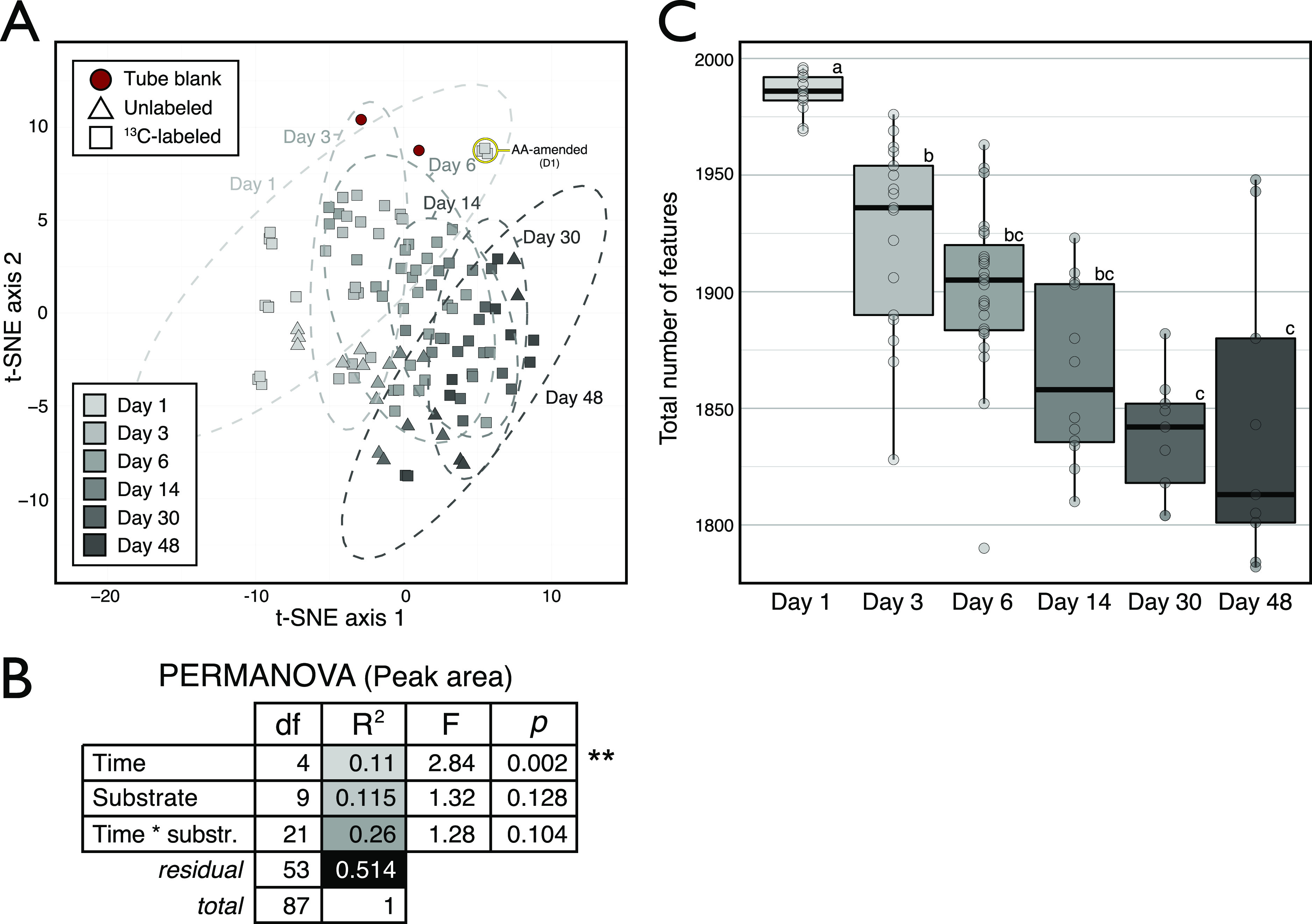

The mixture of carbon added to soil was identical in all aspects except for the identity of the 13C-labeled source; thus, the overall metabolite profiles should not have varied based on total peak area (i.e., without consideration of isotopologs). As expected, metabolite profiles based on total peak area did not vary significantly by carbon source but did change significantly over time (Fig. 1A and B). Temporal changes were similarly responsible for the most variation in whole bacterial community composition (see Table S5 in the supplemental material) and in features in our untargeted approach (Fig. S1). Notably, the total number of features significantly decreased over time (Fig. 1C), suggesting a reduction in metabolite richness as metabolic products were consumed by the community. This decline in molecular diversity differed from results observed during metabolism of dissolved organic carbon in a marine system, in which molecular richness increased over time (19), and our result was consistent with the expectation that carbon sources would be rapidly depleted in soil, where carbon is limiting (20–22). This observation does not necessarily fit with the hypothesis that microbial processing increases soil carbon persistence by increasing chemodiversity (5). That said, it is likely that our method underestimated the richness of metabolites present at very low concentrations.

FIG 1.

Whole metabolite profiles varied primarily across time when compared based on the peak area of all identified metabolites in soil water extracts (n = 138), irrespective of their 13C enrichment. This result was expected, given that every amendment contained the whole set of carbon sources, varying solely by which single source was 13C-labeled. (A) Clustering of samples based on the t-SNE multidimension reduction algorithm, separated along the first axis according to time. The same temporal trend was apparent in untargeted features data shown in Fig. S1. (B) A permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) showed that incubation time was the only significant factor explaining variation in weighted Bray-Curtis dissimilarity among metabolite profiles. Samples from day 1 were removed due to the distorting effect of 13C-labeled amino acids (highlighted in panel A). (C) The total number of features identified in the untargeted analysis decreased over time.

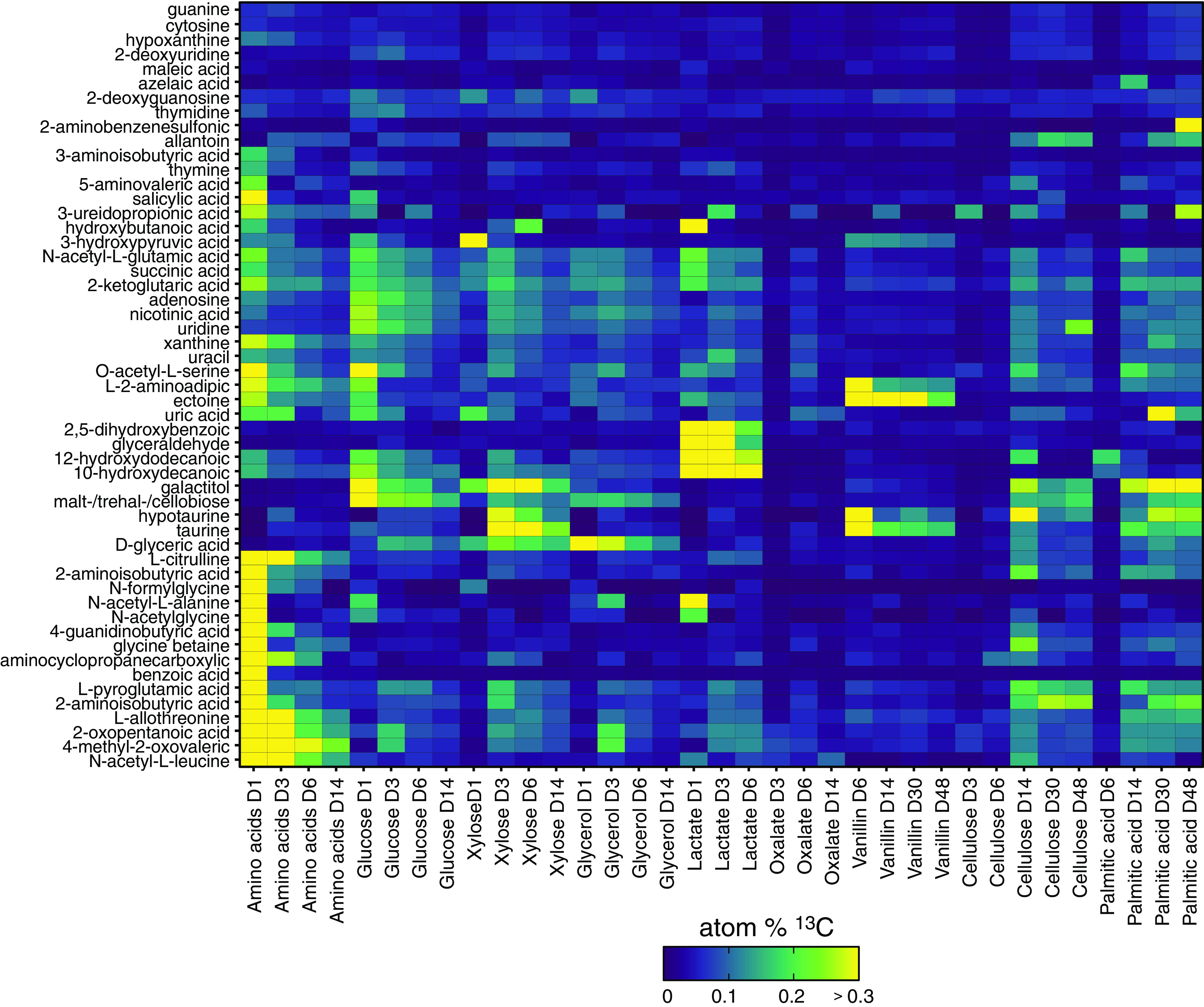

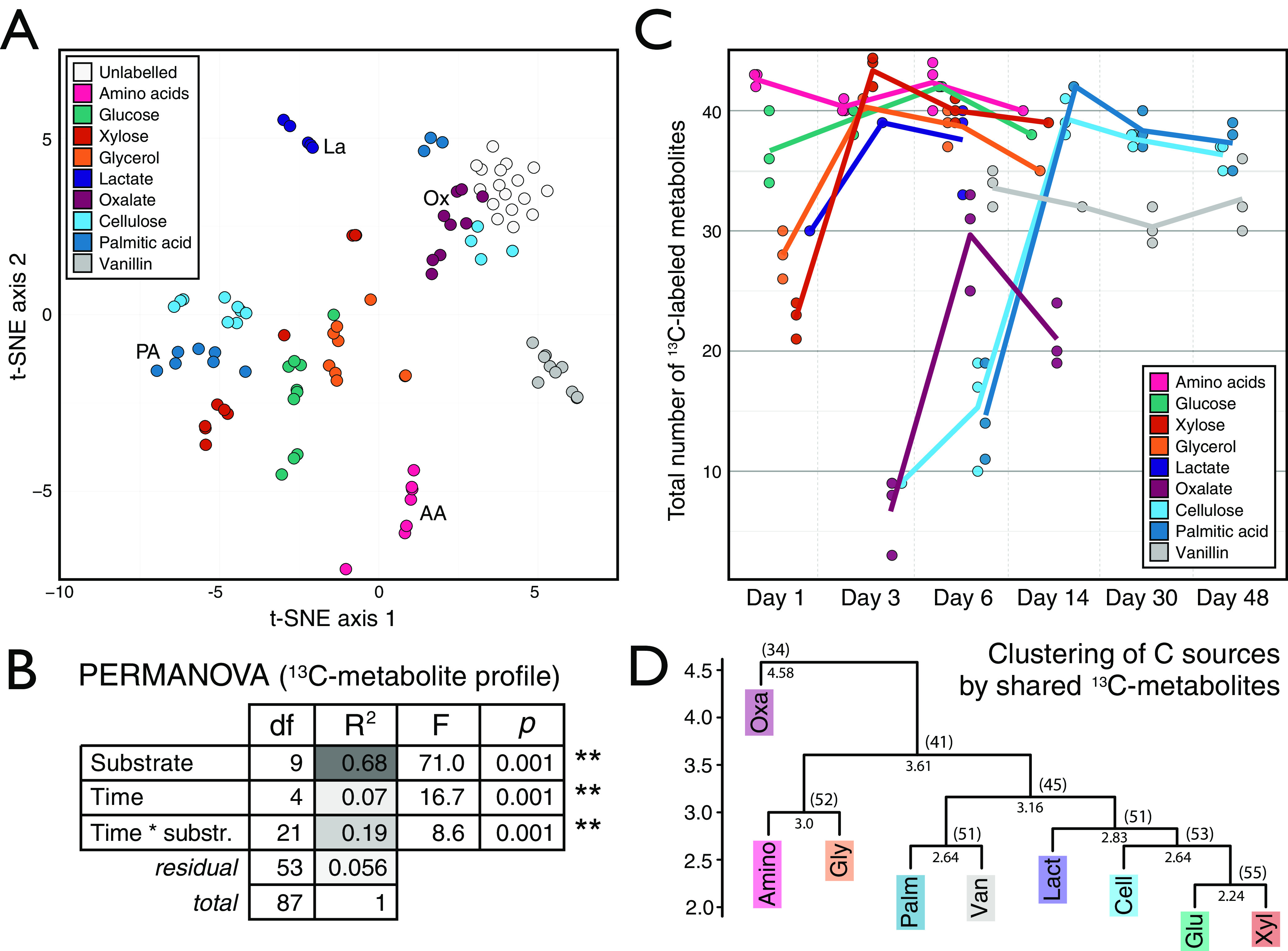

In contrast to whole-soil feature profiles, the 13C-metabolite profile for each carbon source was unique and varied over time (Fig. 2). The 13C-metabolite profiles primarily varied by carbon source (Fig. 3A), which explained significantly more variation in 13C enrichment than time (Fig. 3B). In this way, we falsified our hypothesis that populations with similar growth strategies would share similar 13C-metabolite profiles. As expected, the rate at which metabolites were 13C labeled differed between soluble and insoluble carbon sources (Fig. 3C), but the 13C-metabolite profiles among soluble carbon sources did not differ broadly based on the solubility of carbon sources (Fig. 3D). In fact, both soluble and insoluble carbohydrates (xylose, glucose, and cellulose) yielded the greatest number of shared 13C-labeled metabolites (Fig. 3D), despite differences in the composition of the bacterial populations incorporating 13C from these sources (Fig. S2). Thus, we concluded that differences in the metabolic capabilities of active populations significantly influenced the composition of metabolite pools and that differences according to carbon source persisted over time.

FIG 2.

Atom% 13C enrichment of metabolites varied mainly by carbon source and time. Metabolites corresponding to added 13C-labeled compounds were excluded. The color legend indicates degree of 13C enrichment. Values represent averages of triplicates.

FIG 3.

Trends in the 13C enrichment of metabolites from soil water extracts varied primarily according to the 13C-labeled carbon source. (A) The metabolomes clustered according to carbon source in a t-SNE based on the profile of atom% 13C of metabolites. To ensure clarity, some clusters are labeled with their corresponding carbon source in addition to their coloring. (B) PERMANOVA results showed that carbon source explains most of the variation in the weighted Bray-Curtis dissimilarity among 13C-metabolite profiles. (C) The total number of 13C-labeled metabolites varied over time, and these dynamics mirrored 13C source mineralization as described for this experiment previously (15). (D) Hierarchical clustering of metabolite profiles, based on Euclidean distance of 13C-metabolite presence or absence (Table S4), revealed similarities in labeling profiles between carbon sources. The cophenetic distances for each node and the number of shared metabolites were provided. Metabolites corresponding to added 13C-labeled compounds (n = 15) were excluded from plots except for those in panel C.

Ecological insights into soil community metabolism.

The unique 13C enrichment of metabolites by certain carbon sources revealed differences in the ecological characteristics of community metabolism. Aromatic compounds (benzoate and salicylate) were heavily labeled during the metabolism of the two most rapidly respired carbon sources: amino acids and glucose (15) (Fig. S3). The unique production of [13C]benzoic acid 1 day after addition of 13C-labeled amino acids was likely due to benzoic acid production during phenylalanine catabolism (23). Salicylic acid, in contrast, was produced rapidly from both 13C-labeled amino acids and [13C]glucose, and this argued for a biosynthetic, rather than catabolic, origin. Bacteria such as Pseudomonas and Bacillus are known to excrete salicylic acid (24), and members of these groups were primarily 13C labeled by glucose and amino acids in this experiment (15). It is notable that both benzoic and salicylic acids serve as phytohormones and have antifungal properties (25, 26), though the mechanisms and consequences of production remain to be determined.

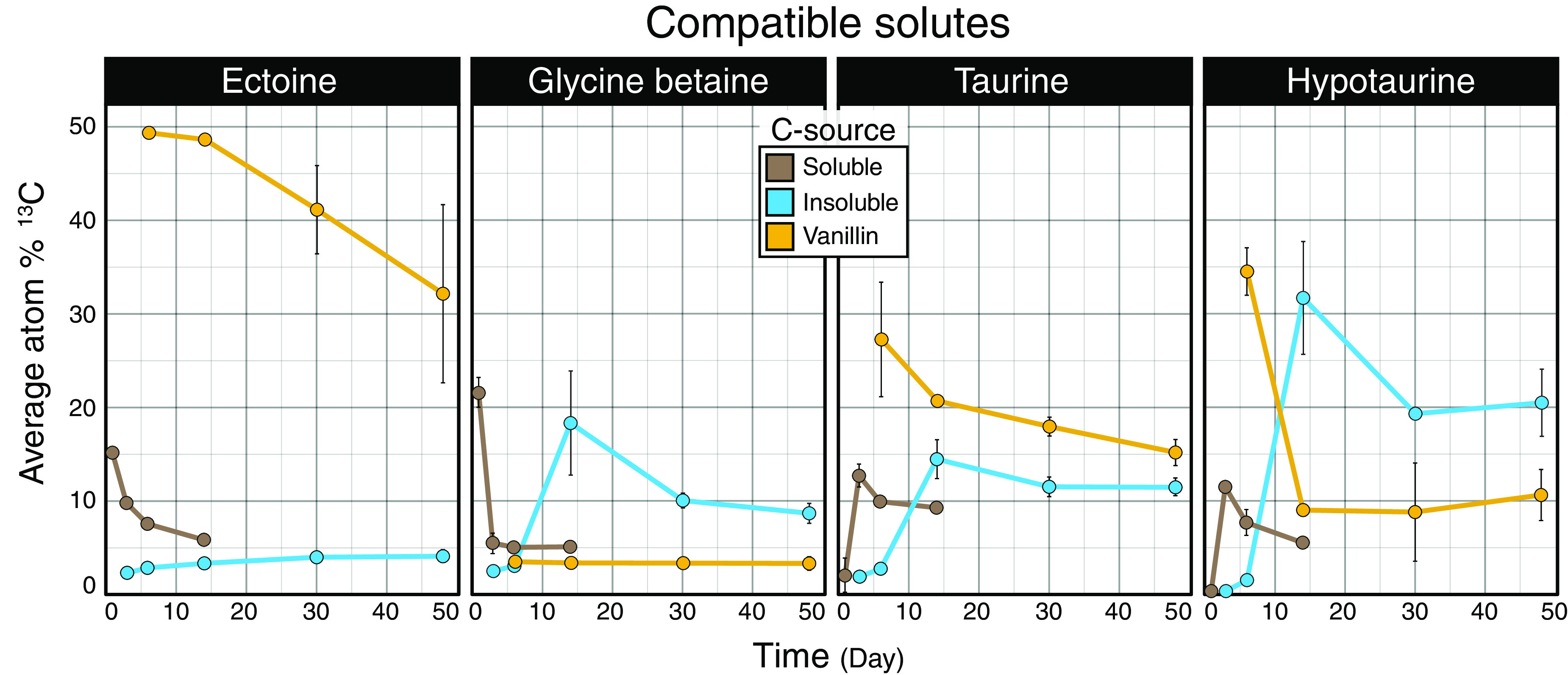

The 13C enrichment of metabolites involved in osmoregulation (i.e., compatible solutes) differed broadly among soluble and insoluble carbon sources and vanillin. The highest 13C enrichment of glycine betaine occurred during periods of peak respiration for both soluble (day 1) and insoluble sources (day 14), while vanillin produced low levels of 13C enrichment (Fig. 4). In comparison, maximal 13C enrichment of ectoine was observed from vanillin, with moderate and minimal enrichment resulting from soluble and insoluble sources, respectively. Ectoine can protect cells from damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS), whereas glycine betaine does not (27, 28). It is possible that differences in 13C labeling of ectoine reflect the needs of cells to protect from ROS generated during the oxidative catabolism of aromatics (29–32), like vanillin, and during periods of high metabolic activity (33).

FIG 4.

Patterns in the atom% 13C enrichment of metabolites identified as compatible solutes differed with respect to carbon source. Trends in major compatible solutes differed among compound types, with ectoine highly enriched during the metabolism of vanillin. Carbon sources were aggregated by response into three classes: soluble (glucose, xylose, amino acids, lactic acid, glycerol, and oxalic acid), insoluble (cellulose and palmitic acid), and vanillin. Points represent average atom% 13C values. Error bars correspond to standard deviations among triplicates. In most cases, error bars are narrow and obscured by the data point, excluding day 14 data, where only a single sample was taken for all carbon sources except for oxalate and cellulose.

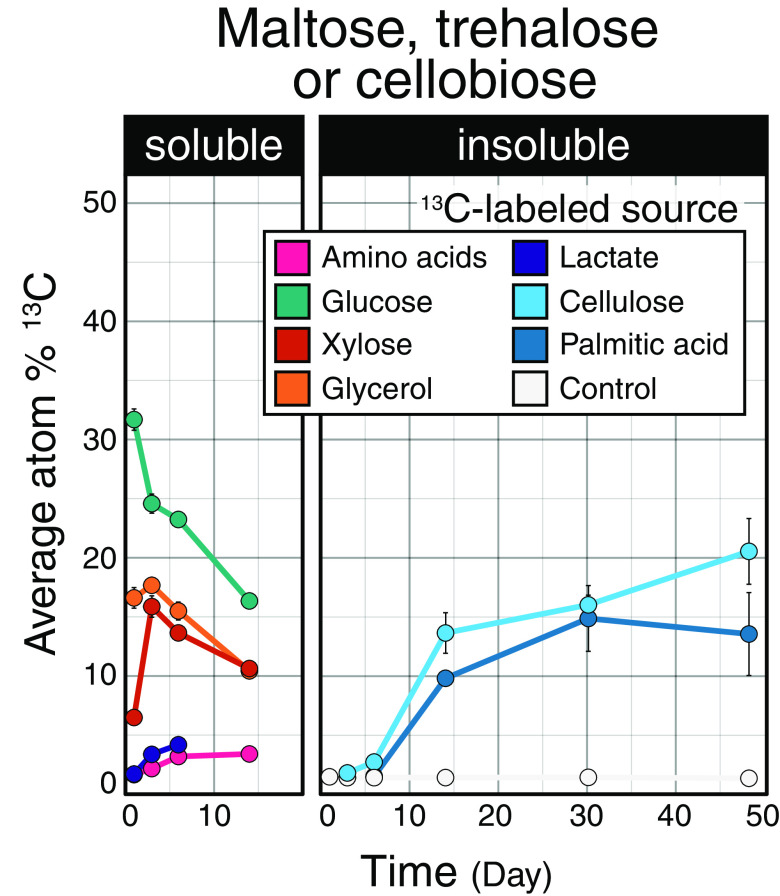

The 13C enrichment of disaccharides (including maltose, trehalose, and cellobiose) also differed between soluble and insoluble carbon sources. Disaccharide enrichment increased over time for insoluble carbon sources, while the opposite trend was generally evident for soluble sources (Fig. 5). For cellulose, this trend may track the liberation of cellobiose during cellulose degradation, but this cannot explain the same trend observed for palmitic acid. Maltose and trehalose are common metabolites that serve in carbon and energy storage, enhancing survival (34, 35) and fueling growth following periods of starvation (36–38). Our observations suggest that populations metabolizing insoluble carbon sources might sustain carbon and energy storage during growth, while populations that metabolize soluble carbon sources begin depleting stores immediately following peak activity.

FIG 5.

Patterns in atom% 13C enrichment of metabolites identified as disaccharides differed with respect to carbon source. The proportion of source-derived 13C occurring in disaccharides (maltose, trehalose, or cellobiose) steadily increased during the degradation of insoluble compounds. Maltose, trehalose, and cellobiose overlapped in m/z and could not be distinguished using our chromatography conditions. Values represent the averages of triplicates. Carbon sources were aggregated by response into two classes: soluble (glucose, xylose, amino acids, lactic acid, glycerol, and oxalic acid) and insoluble (cellulose and palmitic acid). Error bars correspond to standard deviations among triplicates. In most cases, error bars are narrow and obscured by the data point, excluding day 14, where only a single sample was taken for all carbon sources except for oxalate and cellulose.

Microbial growth and the persistence of biomass in soil.

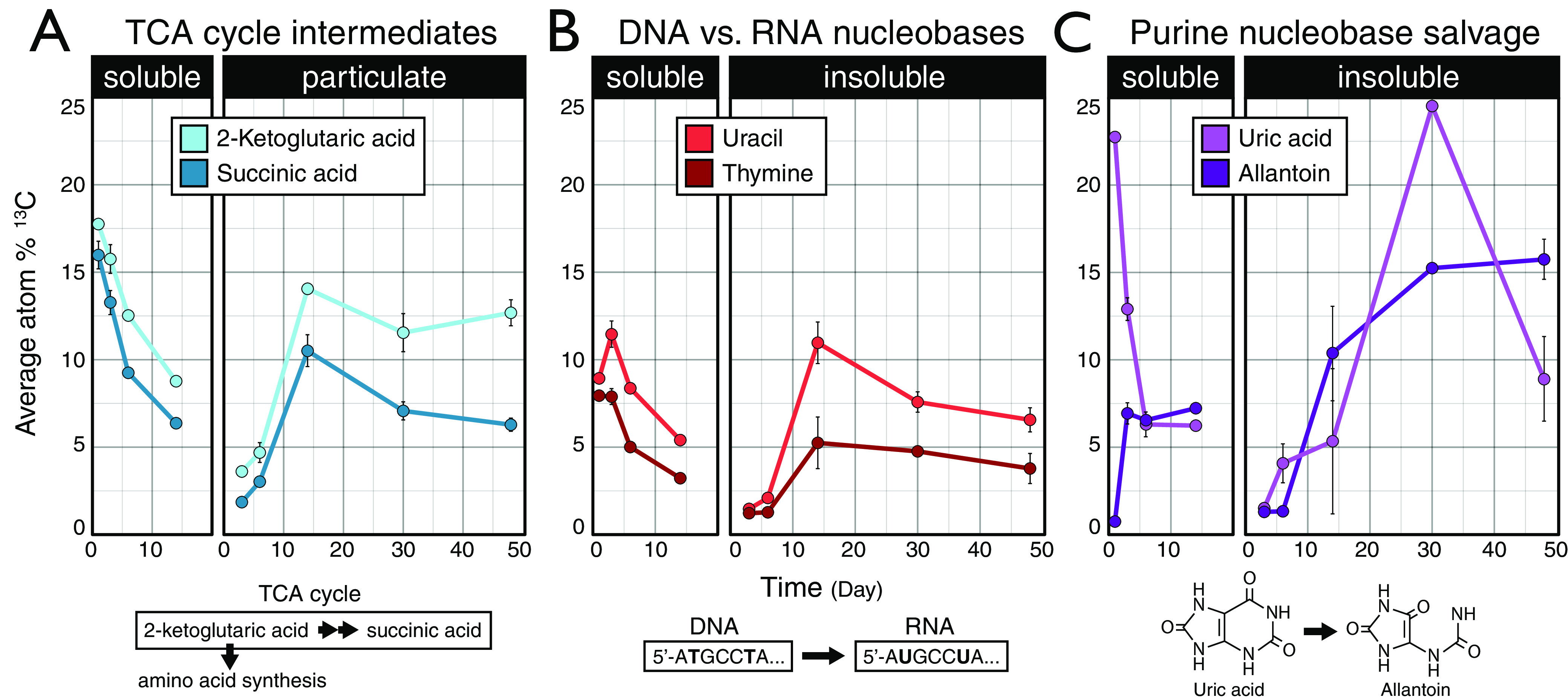

The time of peak metabolite enrichment (i.e., when the most features were 13C enriched) (Fig. 3C) was consistent with the dynamics of 13CO2 respiration. Glucose and amino acids were mineralized earliest (<24 h), followed by lactate, xylose, and glycerol (<2 days), then oxalate (day 6), cellulose (day 10), and palmitic acid (day 14) (15). Rapid 13C enrichment and subsequent depletion of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates (e.g., succinic and 2-ketoglutaric acids), corresponded with peak mineralization activities for both soluble and insoluble carbon sources (Fig. 6A). Notably, the 13C enrichment of uracil (RNA) versus thymine (DNA) diverged most during periods of highest respiration (Fig. 6B), occurring on day 3 (for all soluble carbon sources) and day 14 (insoluble sources). However, without quantification of uracil and thymine concentrations, we cannot know whether this trend reflected absolute differences in 13C abundance.

FIG 6.

Maximum 13C enrichment of TCA cycle intermediates, nucleobases, and purine nucleobase degradation products differed between soluble and insoluble carbon sources. (A) Relative 13C enrichment of TCA intermediates 2-ketogultaric acid (also 2-oxoglutaric acid) and succinic acid. (B) Relative 13C enrichment of nucleobases uracil and thymine. (C) Relative 13C enrichment of uric acid and allantoin. (Note that the degradation of purine bases generates uric acid, which is then cleaved to produce allantoin as part of a salvage pathway.) Carbon sources were aggregated by response into two classes: soluble (glucose, xylose, amino acids, lactic acid, glycerol, and oxalic acid) and insoluble (cellulose and palmitic acid). Points represent average atom% 13C values. Error bars correspond to standard deviations among triplicates. In most cases, error bars are narrow and obscured by the data point, excluding day 14, where only a single sample was taken for all carbon sources except for oxalate and cellulose. The 13C enrichment of metabolites did not account for differences in absolute metabolite concentrations. Thus, comparisons between metabolites may or may not accurately reflect changes in total 13C.

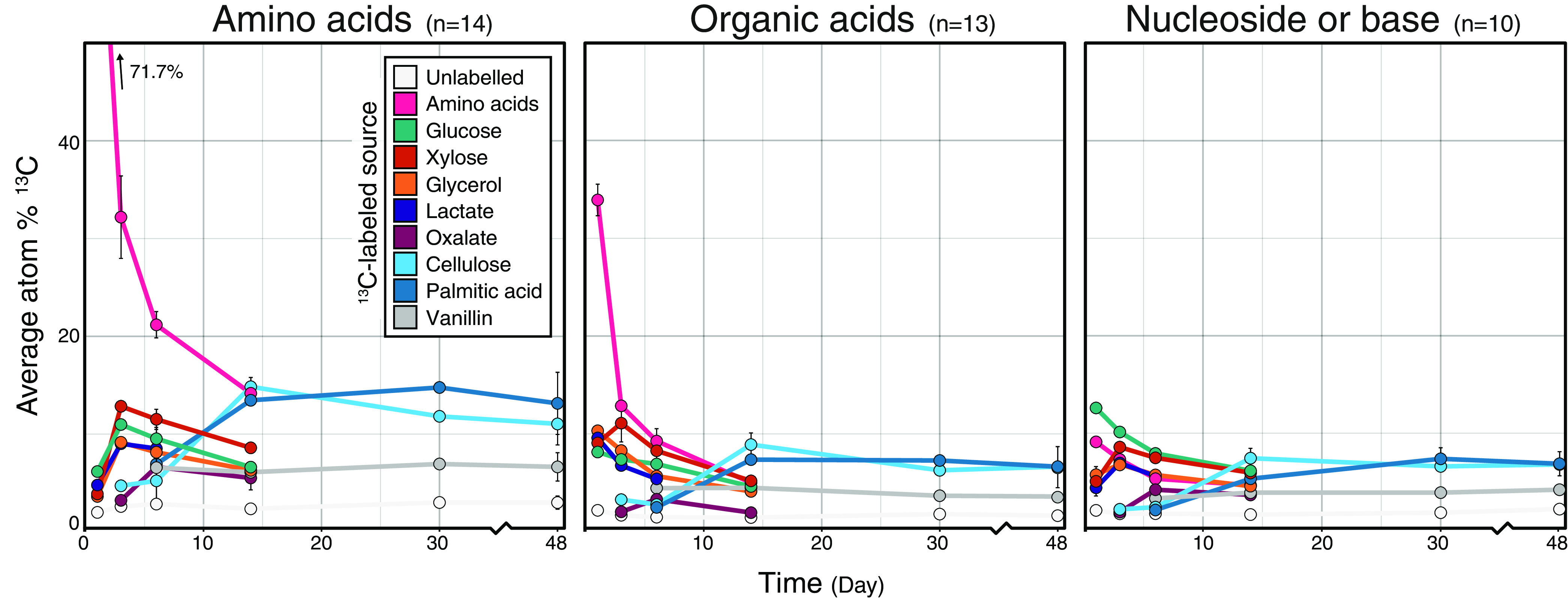

Most markers of microbial biomass and growth, such as amino acids, nucleotides, and organic acids, exhibited broadly similar patterns of 13C enrichment regardless of carbon source, differing primarily with respect to carbon source solubility (Fig. 7). The insoluble carbon sources cellulose and palmitic acid were catabolized through very different pathways, and so the similarity in 13C-metabolite profiles was likely due to common biosynthetic pathways shared among bacteria that colonize and degrade insoluble compounds (17, 18). The enrichment of biomass markers attenuated over time, stabilizing at between 5 to 15 atom% 13C by the end of incubations (Fig. 7). Amino acids had the highest level of enrichment among biomass markers at the end of every incubation (Table 1). This observation was consistent with the long residency time of amino acids in soil (39–41) and likely reflected the preservation of protein in dormant cells or in soil necromass. The latter case is supported by the disproportionately high stabilization of protein relative to other necromass fractions in soils (41). The enrichment of 13C in allantoin, the only metabolite to consistently increase in atom% 13C from all carbon sources over time (Fig. 6C), was further evidence of the possible persistence of source-derived 13C in necromass. Allantoin is produced as part of a salvage pathway during the degradation and/or salvage of purine nucleobases, first yielding uric acid and then allantoin. Allantoin is a valuable source of energy and nitrogen to soil communities (42–44), and thus its persistent enrichment likely reflects the accumulation of 13C in soil necromass.

FIG 7.

Average atom% 13C enrichment of amino acids, organic acids, and nucleosides and bases. The metabolites grouped into these classes are provided in Table S3. Metabolites corresponding to added amino acids were included in the average. The apparent low 13C enrichment of amino acids by day 1 likely reflected our coaddition of unlabeled amino acids, which increased overall pool size, thereby artificially reducing the proportion of newly synthesized 13C-labeled amino acids. Values represent the averages of triplicates. Error bars correspond to standard deviations among triplicates. In most cases, error bars are narrow and obscured by the data point, excluding day 14, where only a single sample was taken for all carbon sources except for oxalate and cellulose.

TABLE 1.

Proportions of source-derived carbon in metabolite poolsa

| Carbon source | Day | Atom% 13C (mean ± SD) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acids | Amino acid derivatives | DNA | Organic acids | ||

| No label | 48 | 2.4 ± 0.04 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| Amino acids | 14 | 14.2 | 8.7 | 4.7 | 5.0 |

| Glucose | 14 | 6.6 | 4.9 | 6.2 | 4.6 |

| Glycerol | 14 | 6.3 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 4.1 |

| Xylose | 14 | 8.6 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 5.2 |

| Oxalate | 14 | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

| Lactate | 6 | 8.5 ± 0.7 | 7.2 ± 0.4 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.5 |

| Cellulose | 48 | 11.0 ± 2.1 | 8.2 ± 1.6 | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 6.5 ± 0.07 |

| Palmitic acid | 48 | 13.1 ± 3.3 | 7.6 ± 1.8 | 6.9 ± 1.2 | 6.7 ± 2.1 |

| Vanillin | 48 | 6.6 ± 1.5 | 5.6 ± 2.5 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| Avgb | 8.1 | 5.6 | 4.9 | 4.3 | |

Higher proportions of source-derived carbon remained in amino acids and their derivatives over time, relative to other compound classes, such as organic acid and nucleic acid metabolite pools, according to the average atom% 13C at the end of each incubation. The specific metabolites grouped into these classes are provided in Table S3. The standard deviation among triplicates is shown, except for amino acids, glucose, glycerol, and xylose, for which only a single sample was available at the final time point.

The last row summarizes the unweighted mean 13C enrichment for all carbon sources.

Conclusions.

Our study demonstrated the extent to which the metabolism of diverse carbon sources affects the fate of carbon in soils. Contrary to our expectations, 13C-metabolite profiles varied more by carbon source than by time, with source-specific differences persisting throughout incubations. This suggested that homogenizing forces, like biomass recycling, are less transformative of soil metabolite pools over the short term (~1 month) than the initial community metabolism of a carbon source. Heterogeneity in 13C-metabolite profiles corresponded with compositional differences in the metabolically active populations (15), which provided a basis for how microbial community composition is correlated with the quality of soil carbon (45).

Our study is among the first examples of SIP-metabolomics in soil systems and demonstrates the capacity to profile metabolite markers of growth, activity, and other aspects of microbial function, such as osmoregulation. Our study was limited in the number of metabolites for which we could reliably calculate atom% 13C. However, tools are becoming available to assist in identifying metabolites in complex biological systems using SIP-metabolomics (46). The full realization of SIP-metabolomics for modeling the pathways of carbon through soil may lie in a comprehensive multi-omics approach. In future, SIP-metabolomic data can be paired with highly resolved genomic and metaproteomic data and relative activity for microbial populations (47–51) to provide a more complete model of a soil community’s carbon metabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design and 13C-labeled carbon sources.

Soil was collected from an organically managed farm field in Penn Yan, NY, USA, as previously described (52). Using a microcosm approach, soils were sieved (2 mm), homogenized, distributed into flasks (10 g in each 250-mL flask), and equilibrated for 1 week prior to the amendment of carbon. Soil microcosms were amended with a single bolus of carbon consisting of nine carbon sources representative of soluble (amino acids, glucose, xylose, glycerol, lactate, oxalate, and vanillin) and insoluble (palmitic acid and cellulose) substrates derived from plant matter, as previously described (15). All nine carbon sources were added together, and only the identity of the single 13C-labeled substrate was varied between treatments, to allow for stable isotope probing of the metabolome over time. 12C-control microcosms contained all unlabeled carbon sources. Triplicate microcosms for each of the nine carbon sources were destructively sampled over time (1, 3, 6, 14, 30, and 48 days after amendment; n = 104 samples) and frozen immediately at −70°C until use. Sampling times were determined by mineralization rates to capture time periods before, during, and after the period of maximal mineralization for each carbon source, as previously described (15). A small number of incubations lacked triplicates at single starting or terminal time points. A complete sample summary is available in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Microcosms were wetted to 50% water holding capacity at the time of carbon amendment and incubated at room temperature, and the headspace was flushed with air after each gas sampling. Sampling was discontinued after day 14 for treatments that received soluble 13C-labeled sources, because these carbon sources were mineralized rapidly and the production of 13CO2 from these sources was minimal after day 14, as previously described (15). 12C-control microcosms were sampled at all six time points.

Each carbon source was added at 0.4 mg C per g of soil for a total addition of 3.6 mg C per g of soil. Soils contained 12.2 mg C per g of soil of preexisting total carbon (52). The following 13C-labeled carbon sources were used: d-glucose (99 atom% 13C; Cambridge Isotopes, Tewksbury, MA, USA), d-xylose (99 atom% 13C; Omicron, South Bend, IN, USA), glycerol (99 atom% 13C; Sigma Isotec, Miamisburg, OH, USA), lactate (99 atom% 13C; Sigma Isotec), oxalate (99 atom% 13C; Sigma Isotec), palmitic acid (99 atom% 13C; Sigma Isotec), algal amino acid mixture (AA; 98 atom% 13C, Cambridge Isotopes), and ring-labeled vanillin (99% atom% 13C6 plus 1.1 atom% 13C2; Sigma Isotec). Bacterial cellulose (~99 atom% 13C) was produced in-house from the growth of Gluconoacetobacter xylinus on minimal medium with [13C]glucose as the sole carbon source, as previously described (17). The algal AA mixture contained 16 proteinogenic amino acids extracted from a blue-green algal source but was deficient for glutamine, asparagine, cysteine, and tryptophan. Identical unlabeled carbon sources (~1.1% atom% 13C) were sourced from the same company or produced in the same manner.

Extraction of metabolites in soil water extracts.

Soil metabolites were extracted following established protocols described in detail elsewhere (53). In brief, 2 g (dry weight) of soil was added to 8 mL liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-grade water in a 15-mL conical tube and shaken on an orbital shaker for 1 h at 200 rpm at 4°C. Samples were then centrifuged at 3,220 × g for 15 min at 4° C, and the supernatant was decanted into a 10-mL syringe attached to a 0.45-μm filter disc and subsequently filtered into 15-mL conical tubes. Filtered extracts were then lyophilized and stored at −80°C prior to LC-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis. We expected most 13C-labeled compounds recovered in soil water extracts to be exometabolites (i.e., secreted by cells), rather than intracellular metabolites freed by cell lysis. Still, an unknown amount of the latter metabolite pool was expected to occur, leading us to refer to our characterization as “water-soluble metabolites.”

LC-MS/MS analysis of soil metabolites.

Lyophilized soil water extracts were resuspended in methanol (150 μL) containing internal standards, as previously described (54), vortexed, and then filtered through 0.22-μm centrifugal membranes (Nanosep MF; Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY). Buffer control samples were prepared by performing the same extraction and resuspension procedures on identical tubes without soil samples. LC-MS was performed using a ZIC-HILIC column (100 mm by 2.1 mm, 3.5 μm, 200 Å; Millipore). An Agilent 1290 series UHPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for metabolite separation. Mobile phases were 5 mM ammonium acetate in water (A) and 95% acetonitrile, 5% 100 mM ammonium acetate in water (B). The gradient used was 100% B for 1.5 min (at 0.45 mL/min), linear decrease to 65% B by 15 min (at 0.45 mL/min), then decrease to 0% B by 18 min (at 0.6 mL/min), held until 23 min (at 0.6 mL/min), and then returned to the initial mixture by 25 min (at 0.45 mL/min). The total runtime was 30 min. Column temperature was 40°C. Negative- and positive-mode data were collected at a mass range of 70 to 1,050 m/z in centroid data mode on a Thermo QExactive system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Fragmentation spectra (MS/MS) were acquired for some metabolites using collision energies of 10 to 40 eV. Sample internal standards and quality control mixtures were run at the beginning (in triplicate) and end (in triplicate) and also individually interspersed every 15 samples to monitor instrument performance.

Metabolite identification.

An untargeted characterization of all “features” evident in LC-MS/MS data was performed to estimate the overall chemical diversity of metabolite pools. Features were identified and annotated with MZmine (v. 2.23) (55). The run parameters have been provided in an .xml file in the supplementary material. A targeted characterization of metabolites was performed using an in-house retention time and fragmentation library with positive assignments, henceforth referred to as “metabolites.” Metabolite identifications were based on comparisons with the retention times, accurate mass, and fragmentation patterns of chemical standards previously analyzed using the same column, gradient, and LC-MS/MS instrumentation. A summary of identification characteristics included similarity in fragmentation pattern, retention time, and precursor m/z; these data are provided in Table S2. LC-MS/MS data was analyzed using the Metabolite Atlas (56) for the metabolite feature extraction and annotation for all targeted metabolites with an intensity of ≥1,500. Calculation of atom% 13C was exclusively performed on metabolites identified in the targeted analysis without interfering signals for isotopologs in the retention time integration window (see extracted ion chromatograms in the supplemental material).

Calculation of atom% 13C of metabolites.

Atom% 13C served as a measure of the balance of source-derived carbon in metabolite pools. An increase in atom% 13C reflects the enrichment of 13C into a given metabolite pool, while a decrease can indicate a pool dilution (channeling of 12C from unlabeled carbon sources into a given metabolite pool). Changes in atom% 13C may also reflect metabolite losses from the differential consumption of a 13C-enriched versus 12C-enriched metabolites among segregated cells and populations, or vice versa. Thus, atom% 13C represents the relative balance between source-derived carbon entering a pool versus its dilution or loss. We did not obtain information about the absolute changes in metabolite concentrations or 13C enrichment. We interpreted any lack of change in atom% 13C enrichment over time as an indication that this metabolite was no longer being consumed or synthesized. The atom% 13C of each metabolite was calculated by apportioning the peak area of each isotopolog using the following equations:

Where n corresponds with the total number of carbon atoms in the metabolite, i corresponds with the number of atoms of 13C in each isotopolog of the metabolite, and Ai corresponds to the peak area of each isotopolog at each m/z. The contribution to mass by other naturally occurring isotopologs (e.g., 15N, 17O, or 2H) was assumed to be negligible based on their relatively low natural abundances (0.36%, 0.038%, and 0.016%, respectively) and low occurrence in the primarily carbon-based metabolites identified. Interference in ion spectra was an issue, leading to the removal of any metabolite that had an atom% 13C of >0.08 in more than 2 of the 17 unlabeled 12C-control samples. Chemodiversity refers to the diversity of chemical compounds in the metabolite pool, while persistence refers to how long the 13C enrichment of these compounds was significantly higher than natural abundance (based on direct comparison to 12C-controls).

Statistical analyses.

All statistical analyses were performed in R (v. 3.4.0) (57). Multiple pairwise comparisons were based on the Kruskal-Wallis test using kruskalmc from the R package pgirmess (v. 1.7). Metabolites were deemed 13C enriched based on Wilcoxon tests that compared soils amended with 12C-labeled versus 13C-labeled carbon sources (triplicates) by day according to adjusted P values of <0.05. P values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg multiple test correction (n = 612). The similarity among metabolite profiles was visualized using the t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) algorithm (58) (v. 0.15) and plotted with the R package ggplot2 (v. 3.3.5) (59). The geom_tile function from ggplot2 was used to create a heatmap of all 13C-enriched metabolites. Bacterial community composition was assessed using 16S rRNA gene amplicon count data sourced from the NCBI Short Read Archive (BioProject PRJNA668741) and processed as described elsewhere (15).

Data availability.

All scripts and data required to reproduce this work are provided in the supplemental material and can also be accessed through the Open Science Foundation (10.17605/OSF.IO/V32KM).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological & Environmental Research Genomic Science Program, under award number DE-SC0016364. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Energy.

R.C.W. performed research and writing. R.C.W. and S.E.B. performed data analysis. T.L.S. performed LCMS analyses, and B.P.B. preprocessed LC-MS data. D.H.B. and N.D.Y. designed the microcosm experiment. D.H.B. and T.R.N. guided all research efforts.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Daniel H. Buckley, Email: dbuckley@cornell.edu.

Jennifer B. Glass, Georgia Institute of Technology

REFERENCES

- 1.Woolf D, Lehmann J. 2019. Microbial models with minimal mineral protection can explain long-term soil organic carbon persistence. Sci Rep 9:6522. 10.1038/s41598-019-43026-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth V-N, Lange M, Simon C, Hertkorn N, Bucher S, Goodall T, Griffiths RI, Mellado-Vázquez PG, Mommer L, Oram NJ, Weigelt A, Dittmar T, Gleixner G. 2019. Persistence of dissolved organic matter explained by molecular changes during its passage through soil. Nat Geosci 12:755–761. 10.1038/s41561-019-0417-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang C, Schimel JP, Jastrow JD. 2017. The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage. Nat Microbiol 2:17105. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sokol NW, Sanderman J, Bradford MA. 2019. Pathways of mineral-associated soil organic matter formation: integrating the role of plant carbon source, chemistry, and point of entry. Glob Chang Biol 25:12–24. 10.1111/gcb.14482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehmann J, Hansel CM, Kaiser C, Kleber M, Maher K, Manzoni S, Nunan N, Reichstein M, Schimel JP, Torn MS, Wieder WR, Kögel-Knabner I. 2020. Persistence of soil organic carbon caused by functional complexity. Nat Geosci 13:529–534. 10.1038/s41561-020-0612-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilhelm RC, Singh R, Eltis LD, Mohn WW. 2019. Bacterial contributions to delignification and lignocellulose degradation in forest soils with metagenomic and quantitative stable isotope probing. ISME J 13:413–429. 10.1038/s41396-018-0279-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z, Yao Q, Guo X, Crits-Christoph A, Mayes MA, Hervey WJ, Lebeis SL, Banfield JF, Hurst GB, Hettich RL, Pan C IV, 2019. Genome-resolved proteomic stable isotope probing of soil microbial communities using 13CO2 and 13C-methanol. Front Microbiol 10:2706–2714. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleiner M, Kouris A, Jensen M, Liu Y, McCalder J, Strous M. 2021. Ultra-sensitive protein-SIP to quantify activity and substrate uptake in microbiomes with stable isotopes. bioRxiv. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.29.437612v1.

- 9.Wilhelm RC, Cardenas E, Leung HTC, Szeitz A, Jensen LD, Mohn WW. 2017. Long-term enrichment of stress-tolerant cellulolytic soil populations following timber harvesting evidenced by multi-omic stable isotope probing. Front Microbiol 8:537. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maxfield PJ, Dildar N, Hornibrook ERC, Stott AW, Evershed RP. 2012. Stable isotope switching (SIS): a new stable isotope probing (SIP) approach to determine carbon flow in the soil food web and dynamics in organic matter pools. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 26:997–1004. 10.1002/rcm.6172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Y, Zheng Q, Wanek W. 2017. Flux analysis of free amino sugars and amino acids in soils by isotope tracing with a novel liquid chromatography/high resolution mass spectrometry platform. Anal Chem 89:9192–9200. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassanpour B, Aristilde L. 2021. Redox-related metabolic dynamics imprinted on short-chain carboxylic acids in soil water extracts: a 13C-exometabolomics analysis. Environ Sci Technol Lett 8:183–191. 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng P, Valentino T, Flythe MD, Moseley HNB, Leachman JR, Morris AJ, Hennig B. 2021. Untargeted stable isotope probing of the gut microbiota metabolome using 13C-labeled dietary fibers. J Proteome Res 20:2904–2913. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.1c00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosier AC, Justice NB, Bowen BP, Baran R, Thomas BC, Northen TR, Banfield JF. 2013. Metabolites associated with adaptation of microorganisms to an acidophilic, metal-rich environment identified by stable-isotope-enabled metabolomics. mBio 4:e00484-12. 10.1128/mBio.00484-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnett SE, Youngblut ND, Koechli CN, Buckley DH. 2022. Multisubstrate DNA stable isotope probing reveals guild structure of bacteria that mediate soil carbon cycling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118:e2115292118. 10.1073/pnas.2115292118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bore EK, Kuzyakov Y, Dippold MA. 2019. Glucose and ribose stabilization in soil: convergence and divergence of carbon pathways assessed by position-specific labeling. Soil Biol Biochem 131:54–61. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.12.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pepe-Ranney C, Campbell AN, Koechli CN, Berthrong S, Buckley DH. 2016. Unearthing the ecology of soil microorganisms using a high resolution DNA-SIP approach to explore cellulose and xylose metabolism in soil. Front Microbiol 7:703–717. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilhelm RC, Pepe-Ranney C, Weisenhorn P, Lipton M, Buckley DH. 2021. Competitive exclusion and metabolic dependency among microorganisms structure the cellulose economy of an agricultural soil. mBio 12:1–19. 10.1128/mBio.03099-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mentges A, Feenders C, Seibt M, Blasius B, Dittmar T. 2017. Functional molecular diversity of marine dissolved organic matter is reduced during degradation. Front Mar Sci 4:1–10. 10.3389/fmars.2017.00194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demoling F, Figueroa D, Bååth E. 2007. Comparison of factors limiting bacterial growth in different soils. Soil Biol Biochem 39:2485–2495. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soong JL, Fuchslueger L, Marañon-Jimenez S, Torn MS, Janssens IA, Penuelas J, Richter A. 2020. Microbial carbon limitation: the need for integrating microorganisms into our understanding of ecosystem carbon cycling. Glob Change Biol 26:1953–1961. 10.1111/gcb.14962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ekblad A, Nordgren A. 2002. Is growth of soil microorganisms in boreal forests limited by carbon or nitrogen availability? Plant Soil 242:115–122. 10.1023/A:1019698108838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thierry A, Maillard MB. 2002. Production of cheese flavour compounds derived from amino acid catabolism by Propionibacterium freudenreichii. Lait 82:17–32. 10.1051/lait:2001002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishra AK, Baek KH. 2021. Salicylic acid biosynthesis and metabolism: a divergent pathway for plants and bacteria. Biomolecules 11:705. 10.3390/biom11050705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan X, Welti R, Wang X. 2008. Simultaneous quantification of major phytohormones and related compounds in crude plant extracts by liquid chromatography-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Phytochemistry 69:1773–1781. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amborabé BE, Fleurat-Lessard P, Chollet JF, Roblin G. 2002. Antifungal effects of salicylic acid and other benzoic acid derivatives towards Eutypa lata: structure-activity relationship. Plant Physiol Biochem 40:1051–1060. 10.1016/S0981-9428(02)01470-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hahn MB, Meyer S, Schröter MA, Kunte HJ, Solomun T, Sturm H. 2017. DNA protection by ectoine from ionizing radiation: molecular mechanisms. Phys Chem Chem Phys 19:25717–25722. 10.1039/c7cp02860a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brands S, Schein P, Castro-Ochoa KF, Galinski EA. 2019. Hydroxyl radical scavenging of the compatible solute ectoine generates two N-acetimides. Arch Biochem Biophys 674:108097. 10.1016/j.abb.2019.108097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chávez FP, Lünsdorf H, Jerez CA. 2004. Growth of polychlorinated-biphenyl-degrading bacteria in the presence of biphenyl and chlorobiphenyls generates oxidative stress and massive accumulation of inorganic polyphosphate. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:3064–3072. 10.1128/AEM.70.5.3064-3072.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamburro A, Robuffo I, Heipieper HJ, Allocati N, Rotilio D, Di Ilio C, Favaloro B. 2004. Expression of glutathione S-transferase and peptide methionine sulphoxide reductase in Ochrobactrum anthropi is correlated to the production of reactive oxygen species caused by aromatic substrates. FEMS Microbiol Lett 241:151–156. 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denef VJ, Patrauchan MA, Florizone C, Park J, Tsoi TV, Verstraete W, Tiedje JM, Eltis LD. 2005. Growth substrate- and phase-specific expression of biphenyl, benzoate, and C1 metabolic pathways in Burkholderia xenovorans LB400. J Bacteriol 187:7996–8005. 10.1128/JB.187.23.7996-8005.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J. 2017. Stress responses of Acinetobacter strain Y during phenol degradation. Arch Microbiol 199:365–375. 10.1007/s00203-016-1310-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McBee ME, Chionh YH, Sharaf ML, Ho P, Cai MWL, Dedon PC. 2017. Production of superoxide in bacteria is stress- and cell state-dependent: a gating-optimized flow cytometry method that minimizes ROS measurement artifacts with fluorescent dyes. Front Microbiol 8:459. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones SA, Jorgensen M, Chowdhury FZ, Rodgers R, Hartline J, Leatham MP, Struve C, Krogfelt KA, Cohen PS, Conway T. 2008. Glycogen and maltose utilization by Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the mouse intestine. Infect Immun 76:2531–2540. 10.1128/IAI.00096-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourassa L, Camilli A. 2009. Glycogen contributes to the environmental persistence and transmission of Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol 72:124–138. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi L, Sutter BM, Ye X, Tu BP. 2010. Trehalose is a key determinant of the quiescent metabolic state that fuels cell cycle progression upon return to growth. Mol Biol Cell 21:1982–1990. 10.1091/mbc.e10-01-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamotoya T, Dose H, Tian Z, Fauré A, Toya Y, Honma M, Igarashi K, Nakahigashi K, Soga T, Mori H, Matsuno H. 2012. Glycogen is the primary source of glucose during the lag phase of E. coli proliferation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1824:1442–1448. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rittershaus ESC, Baek SH, Sassetti CM. 2013. The normalcy of dormancy: common themes in microbial quiescence. Cell Host Microbe 13:643–651. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sorensen LH. 1975. The influence of clay on the rate of decay of amino acid metabolites synthesized in soils during decomposition of cellulose. Soil Biol Biochem 7:171–177. 10.1016/0038-0717(75)90015-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hatton PJ, Remusat L, Zeller B, Brewer EA, Derrien D. 2015. NanoSIMS investigation of glycine-derived C and N retention with soil organo-mineral associations. Biogeochemistry 125:303–313. 10.1007/s10533-015-0138-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miltner A, Kindler R, Knicker H, Richnow HH, Kästner M. 2009. Fate of microbial biomass-derived amino acids in soil and their contribution to soil organic matter. Org Geochem 40:978–985. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2009.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalgliesh CE, Neuberger A. 1954. The mechanism for the conversions of uric acid into allantoin and glycine. J Chem Soc 1954:3407–3414. 10.1039/jr9540003407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Antheunisse J. 1972. Decomposition of nucleic acids and some of their degradation products by microorganisms. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 38:311–327. 10.1007/BF02328101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Navone L, Casati P, Licona-Cassani C, Marcellin E, Nielsen LK, Rodriguez E, Gramajo H. 2014. Allantoin catabolism influences the production of antibiotics in Streptomyces coelicolor. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:351–360. 10.1007/s00253-013-5372-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Domeignoz-Horta LA, Shinfuku M, Junier P, Poirier S, Verrecchia E, Sebag D, DeAngelis KM. 2021. Direct evidence for the role of microbial community composition in the formation of soil organic matter composition and persistence. ISME Commun 1:5–8. 10.1038/s43705-021-00071-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bueschl C, Kluger B, Neumann NKN, Doppler M, Maschietto V, Thallinger GG, Meng-Reiterer J, Krska R, Schuhmacher R. 2017. MetExtract II: a software suite for stable isotope-assisted untargeted metabolomics. Anal Chem 89:9518–9526. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b02518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dumont MG, Radajewski SM, Miguez CB, McDonald IR, Murrell JC. 2006. Identification of a complete methane monooxygenase operon from soil by combining stable isotope probing and metagenomic analysis. Environ Microbiol 8:1240–1250. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lueders T, Wagner B, Claus P, Friedrich MW. 2003. Stable isotope probing of rRNA and DNA reveals a dynamic methylotroph community and trophic interactions with fungi and protozoa in oxic rice field soil. Environ Microbiol 6:60–72. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whiteley AS, Thomson B, Lueders TT, Manefield M. 2007. RNA stable-isotope probing. Nat Protoc 2:838–844. 10.1038/nprot.2007.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Youngblut ND, Barnett SE, Buckley DH. 2018. SIPSim: a modeling toolkit to predict accuracy and aid design of DNA-SIP experiments. Front Microbiol 9:570. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hungate BA, Mau RL, Schwartz E, Gregory Caporaso J, Dijkstra P, van Gestel N, Koch BJ, Liu CM, McHugh TA, Marks JC, Morrissey EM, Price LB. 2015. Quantitative microbial ecology through stable isotope probing. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:7570–7581. 10.1128/AEM.02280-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berthrong ST, Buckley DH, Drinkwater LE. 2013. Agricultural management and labile carbon additions affect soil microbial community structure and interact with carbon and nitrogen cycling. Microb Ecol 66:158–170. 10.1007/s00248-013-0225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swenson TL, Jenkins S, Bowen BP, Northen TR. 2015. Untargeted soil metabolomics methods for analysis of extractable organic matter. Soil Biol Biochem 80:189–198. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swenson TL, Couradeau E, Bowen BP, De Philippis R, Rossi F, Mugnai G, Northen TR. 2018. A novel method to evaluate nutrient retention by biological soil crust exopolymeric matrix. Plant Soil 429:53–64. 10.1007/s11104-017-3537-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pluskal T, Castillo S, Villar-Briones A, Orešič M. 2010. MZmine 2: modular framework for processing, visualizing, and analyzing mass spectrometry-based molecular profile data. BMC Bioinformatics 11:395. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yao Y, Sun T, Wang T, Ruebel O, Northen T, Bowen BP. 2015. Analysis of metabolomics datasets with high-performance computing and metabolite atlases. Metabolites 5:431–442. 10.3390/metabo5030431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Core Team R. 2020. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 58.van der Maaten L, Hinton G. 2008. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J Machine Learn Res 9:2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wickham H. 2009. Ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis, 2nd ed. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 to S3. Download aem.00839-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.5 MB (495.5KB, pdf)

Tables S1 to S5. Download aem.00839-22-s0002.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.2 MB (211.2KB, xlsx)

Data Availability Statement

All scripts and data required to reproduce this work are provided in the supplemental material and can also be accessed through the Open Science Foundation (10.17605/OSF.IO/V32KM).