Abstract

Larvae of Toxocara canis, a nematode parasite of dogs, infect humans, causing visceral and ocular larva migrans. In noncanid hosts, larvae neither grow nor differentiate but endure in a state of arrested development. Reasoning that parasite protein production is orientated to immune evasion, we undertook a random sequencing project from a larval cDNA library to characterize the most highly expressed transcripts. In all, 266 clones were sequenced, most from both 3′ and 5′ ends, and similarity searches against GenBank protein and dbEST nucleotide databases were conducted. Cluster analyses showed that 128 distinct gene products had been found, all but 3 of which represented newly identified genes. Ninety-five genes were represented by a single clone, but seven transcripts were present at high frequencies, each composing >2% of all clones sequenced. These high-abundance transcripts include a mucin and a C-type lectin, which are both major excretory-secretory antigens released by parasites. Four highly expressed novel gene transcripts, termed ant (abundant novel transcript) genes, were found. Together, these four genes comprised 18% of all cDNA clones isolated, but no similar sequences occur in the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. While the coding regions of the four genes are dissimilar, their 3′ untranslated tracts have significant homology in nucleotide sequence. The discovery of these abundant, parasite-specific genes of newly identified lectins and mucins, as well as a range of conserved and novel proteins, provides defined candidates for future analysis of the molecular basis of immune evasion by T. canis.

Toxocara canis is a common nematode parasite of dogs and related species. Adult worms live in the gastrointestinal tract, releasing eggs which enter the environment by the fecal route. Within the eggs, larval T. canis develop over a 2- to 3-week period (27). Embryonated eggs are then infective if ingested by a new host, as larvae hatch in the stomach and penetrate the epithelial layer. T. canis larvae show a remarkable lack of host specificity, infecting a wide range of taxa, including humans (27, 28). In the definitive (canid) host, larvae may mature by migrating to the intestine and developing to the adult stage; such maturation is favored in pups and in reproducing females (40). In most other dogs and in all paratenic hosts such as humans, development is arrested at the larval stage.

The arrested stage is remarkable for surviving for as long as 9 years in vivo (7), without reproduction or differentiation and without succumbing to attack by the host immune system. This diapausal state is mirrored in vitro, where larvae survive for many months in serum-free medium, secreting quantities of excretory-secretory antigens which have been characterized in biochemical (5, 50, 58) and immunological (44, 45, 56) terms.

We hypothesized that in the absence of cell division, tissue growth, or gametogenesis, a significant proportion of larval protein production, and therefore mRNA, is likely to be directed at immune evasion. To characterize abundant mRNAs, we conducted a small-scale expressed sequence tag (EST) project. EST sequencing was pioneered for mammalian cells (1, 2) and Caenorhabditis elegans (49) and is an important component of major parasite sequencing projects (15, 18, 22, 23, 46, 64). By this means, we have identified a series of abundantly expressed genes from larval T. canis, among which are likely to be important mediators of parasite immune evasion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

cDNA library.

T. canis larvae were hatched and maintained in vitro as previously described (20, 50) for a period of 6 months, with weekly changes of serum-free medium. From 200,000 cultured T. canis larvae, using a single-step guanidine-phenol-chloroform extraction, 265 μg of total RNA was recovered, from which 6 μg of poly(A)+ RNA was isolated by oligo(dT) chromatography. cDNA synthesized from this mRNA was unidirectionally cloned into the Uni-Zap XR phage vector, using packaging extracts from Stratagene. The amplified library contained 1.9 × 109 PFU/ml with 91% recombinants. The possibility of host contamination was essentially eliminated because eggs were first incubated in vitro in formalin, and once hatched, larvae were cultured in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium.

Isolation of cDNA clones and in vivo excision of phagemids.

Single clones were randomly picked phage from the plated out cDNA library. Phagemids were rescued in vivo by using ExAssist helper phage and nonsuppressing Escherichia coli SOLR (Stratagene).

Selection and maintenance of clones.

Plasmids were prepared from overnight cultures by using a Qiaprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen) and stored at −20°C. Insert sizes were determined by PCR using vector primers (M13 reverse and M13 forward primers or T3 and T7 primers). In the few cases where insert sizes could not be determined by PCR, restriction digestion of purified recombinant plasmids was performed with XbaI and XhoI (Promega). All clones are available to the research community on request.

Sequencing.

Plasmid templates were sequenced by using dye terminator cycle sequencing chemistry with Amplitaq DNA polymerase (FS enzyme) on an ABI 377 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Both 5′ and 3′ ends were sequenced in some cases where 5′ sequences gave high-quality sequence through the poly(A) tail or where the 5′ sequence showed unequivocal identity with a previously characterized T. canis clone.

Analysis.

SeqEd version 1.0.3 (Applied Biosystems) was used to edit out vector sequence and flanking sequences. Sequences were aligned by using AssemblyLign and MacVector 6.0 software (Oxford Molecular). Nonredundant database searches used ungapped BLAST (basic local alignment search tool) (3) on the National Center for Biotechnology Information server. Nucleotide sequences were subjected to BLASTX searches against the GenBank nr (nonredundant) protein database. Nucleotide sequence searches used BLASTN (on both nr and dbEST databases), and deduced protein sequence from any unambiguous open reading frame was used to search with TBLASTN (against the nr nucleotide database).

Nomenclature.

Gene naming follows the convention for nematodes (11, 14) of a three-letter name and a number, and a prefix indicating the source organism, in this case Tc. Genes are denoted in italics; proteins are capitalized. Three sets of interim gene names were used where no functional homology exists: Tc-not (novel transcript), Tc-ant (abundant novel transcript, where ≥5 clones of 263 are identical), and Tc-huf (homolog of unknown function, where similar sequences have been found in other nematode species). For interim gene designations, the number of the EST clone first sequenced is retained; for cDNAs assigned functional names, clones are generally numbered sequentially (e.g., Tc-ctl-1 and -2 for C-type lectins), except where numbering is significant in other organisms, principally for ribosomal proteins (e.g., Tc-rps-4, -5, and -9 to conform with established nomenclature).

Database deposition.

All sequences have been deposited in NCBI dbEST (17) with separate entries for 5′ and 3′ reads.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sequencing and similarity searches.

A total of 261 clones, containing inserts ranging from 128 to 2,050 bp, were taken for analysis once nonrecombinant and chimeric clones were discarded. All were sequenced from the 5′ end, and 218 were also sequenced from the 3′ end. Most similarities were found, or were stronger, with the 5′ sequences, but a significant minority of similarity relationships were found only with 3′ sequence reads. In general, a probability value of 10−6 was sought as a minimum degree of similarity.

Clustering analysis.

EST sequences were clustered on the basis of nucleotide identity. It was noted that in some of the larger clusters, identity of the 3′ sequences was critical to correctly group differentially truncated clones with nonoverlapping 5′ sequences.

As a result of these analyses, a total of 128 distinct gene products were identified. Of these, only three, mucin 1 (Tc-muc-1 [25]), phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein (Tc-peb-1 [26]), and the 60S ribosomal protein L3 (Tc-rpl-3 [51]), have been previously characterized. Approximately 50% (65/128) of the total number of genes have informative similarity to genes of known function from other species, a further 17 clones have database homologs of unknown function, and 47 genes (37%) show no similarity to known genes; among this last class, designated novel genes, 4 were classified as abundant transcripts (see below).

Abundant transcripts.

A small number of transcripts are heavily represented in the library. Just 8 transcripts (6.2% of genes) account for 102 clones (39.1%) sequenced, while the 20 most abundant (all those isolated three or more times) accounted for 143 clones (54.8%). Table 1 presents the transcripts characterized in order of frequency, with the most highly sampled clone being cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (25/261 = 9.6% of clones), which is a mitochondrial DNA-encoded gene in other nematodes (36, 52). The second most common clone is a C-type lectin (16/261 = 6.1%) which in work to be published elsewhere we demonstrate encodes the major surface and secreted glycoprotein of T. canis larvae, TES-32 (42).

TABLE 1.

Frequency of transcripts

| Transcript (gene) | No. of clones sequenced | Frequency of transcripts (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (cox-2) | 25 | 9.6 |

| C-type lectin, TES-32 (ctl-1) | 16 | 6.1 |

| Abundant novel transcript 003 (ant-003) | 15 | 5.7 |

| Abundant novel transcript 034 (ant-034) | 13 | 5.0 |

| Abundant novel transcript 030 (ant-030) | 13 | 5.0 |

| Abundant novel transcript 005 (ant-005) | 7 | 2.7 |

| Mucin 1, TES-120 (muc-1) | 7 | 2.7 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein, TES-26 (peb-1) | 5 | 1.9 |

| Novel transcript 095 (not-095) | 4 | 1.5 |

| Protein tyrosine phosphatase (ptp-1) | 4 | 1.5 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L19 (rpl-19) | 4 | 1.5 |

| ADP/ATP translocase (aat-1) | 3 | 1.1 |

| ASP homolog 1/TC-CRISP (vah-1) | 3 | 1.1 |

| Mucin 2 (muc-2) | 3 | 1.1 |

| Novel transcript 018 (not-018) | 3 | 1.1 |

| Novel transcript 120 (not-120) | 3 | 1.1 |

| 60S ribosomal protein P0 (rpp-0) | 3 | 1.1 |

| Superoxide dismutase 3 (sod-3) | 3 | 1.1 |

| Tubulin alpha-3 chain (tua-3) | 3 | 1.1 |

| 14 transcripts present as two clonesa | 28 | 10.7 |

| 95 transcripts present as single clones | 96 | 36.7 |

| Total no. of clones sequenced | 261 |

Abundant novel transcripts.

Unexpectedly, four more abundant clones are all novel, with no similarities in the database or, in the coding regions, to each other. These transcripts each represent between 2.7 and 5.7% of ESTs and together account for more than 18% of the library. They have consequently been designated ant genes and retain the number of the EST clone from which they were first isolated (ant-003, -005, -030, and -034).

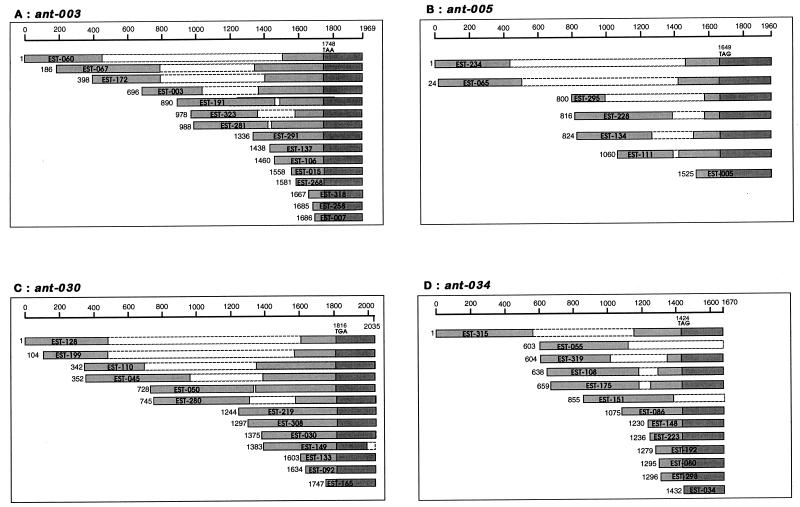

The four ant genes differ in length and composition, but all are 1.6 kb or more in length. The characterization of their full-length sequences, and of the protein products encoded by these genes, is currently under way, as none of the ESTs isolated include 5′ methionine start codons. Figure 1 presents a map of the EST clones isolated for each ant gene. From this it can be seen that 3′ sequencing proved essential in identifying all members of the cluster, because 5′ sequences do not in all cases overlap. Because the multiple clones all have different 5′ termini, the abundance of these transcripts appears not to be an artifactual amplification of single clones in the construction of the library.

FIG. 1.

Alignments of clones corresponding to ant-003, -005, -030, and -034. Segments sequenced in single-pass reactions are lightly shaded; unsequenced portions are shown unshaded in broken lines. Darker shading corresponds to 3′ UTRs. The position and codon of the stop signal are indicated for each transcript. Numbers to the left of the bars indicate the approximate start of the cDNA relative to the longest clone. No start codons have yet been identified for any of these genes, and hence numbering is provisional. Note that without 3′ sequence data, the longer EST clones belonging to ant-005 and ant-034 would not have been recognized.

Homology in 3′ UTRs of the four ant genes.

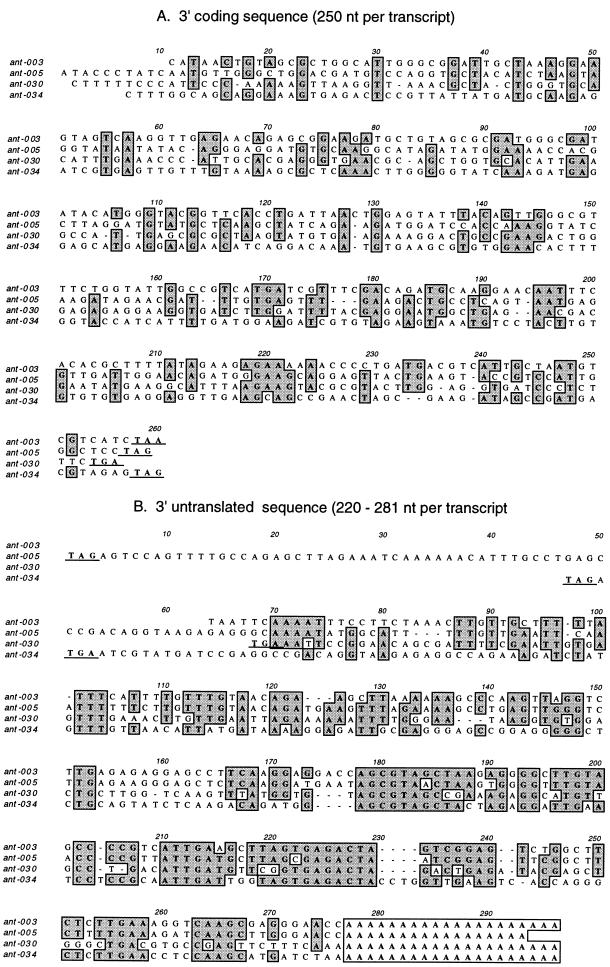

Although ant-003, -005, -030, and -034 showed no similarities between coding regions, the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of all four genes bore significant levels of identity. It is notable also that none of these 3′ ends contain consensus polyadenylation motifs such as AATAAA or similar sequence. This is not unprecedented among nematode genes: a recent survey of C. elegans 3′ UTRs found that 7% of mRNAs bore no identifiable polyadenylation signal (16).

An alignment of the 3′ coding regions and UTRs of these four transcripts shows little identity in coding region nucleotides (Fig. 2A) or amino acids (not shown) but similar sequences in all four genes immediately after the stop codon (Fig. 2B). No similar sequences were found in any other T. canis genes or in genes from other organisms such as C. elegans. In C. elegans, there are examples of 3′ UTR motifs associated with repression of translation in genes such as tra-2 and fem-3 in germ line cell differentiation (4, 68). This is unlikely to be a useful parallel for the T. canis ant genes, as there is no similarity in 3′ UTR sequence between the two species and there is no gonadal development in the larval stage of T. canis. Translational suppression of the ant genes would be a surprising event in light of their unusually high level of transcription.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of 250-nucleotide (nt) 3′-terminal coding sequences (A) and complete 3′ UTRs (B) of the four ant genes; identical settings were used for both alignments in MacVector ClustalW alignment (gap penalty = 10.0, extend gap penalty = 5.0). The stop codons at the end of the coding sequence and the beginning of the UTR are underlined. Bases identical in three or four of the sequences are boxed and shaded. The polyadenylated tail is shown boxed without shading.

Homologs of genes of unknown function.

Sixteen clones showed significant similarities to known nematode sequences with no assigned function (Table 2). These were all designated huf genes, retaining the number of the corresponding EST clone. One clone, Tc-huf-001, contains a tandem array of four blocks of 36 amino acids each containing six cysteines in identical alignment. This motif, termed the NC6 (26) or SXC (12) domain, is found in T. canis and C. elegans proteins, particularly those associated with nematode surfaces, but the function of the array is not known.

TABLE 2.

Homologs to proteins of unknown function in other nematodesa

| Gene | Similarity to: | P | EST name | Insert size | Read

|

GenBank accession no.

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5′ | 3′ | 5′ | 3′ | |||||

| Tc-huf-001 | NC6/SXC domain | Tc-EST-001 | 800 | 764 | 666 | AA683457 | AA683458 | |

| Tc-huf-012 | C. elegans R53.5 gene | 3.8E-06 | Tc-EST-012 | 850 | 599 | 342 | AA563573 | AI374481 |

| Tc-huf-053 | C. elegans C13A10 gene | 2.8E-38 | Tc-EST-053 | 1,000 | 589 | 602 | AA610971 | AA610972 |

| Tc-huf-062 | C. elegans F41D9.1 gene | 4.3E-42 | Tc-EST-062 | 760 | 482 | 521 | AA612566 | AA907959 |

| Tc-huf-159 | C. elegans C56E6.5 gene | 7.6E-15 | Tc-EST-159 | 1,850 | 387 | 288 | AA836705 | AA836706 |

| Tc-huf-169 | C. elegans K02E10.6 gene | 6.2E-17 | Tc-EST-169 | 1,050 | 466 | 393 | AA874757 | AA874758 |

| Tc-huf-252 | C. elegans Y57G11C.12 gene | 7.7E-30 | Tc-EST-252 | 1,150 | 547 | 558 | AA684533 | AA684534 |

| Tc-huf-264 | C. elegans B0034.3 gene | 1.4E-25 | Tc-EST-264 | 1,420 | 589 | 444 | AA684531 | AA684532 |

| Tc-huf-287 | C. elegans K12H4.5 gene | 5.3E-23 | Tc-EST-287 | 452 | 429 | 416 | AA875794 | AA979711 |

| Tc-huf-296 | C. elegans T24F1.6 gene | 1.9E-11 | Tc-EST-296 | 2,300 | 259 | 491 | AA875806 | AA875807 |

| Tc-huf-302 | B. malayi MBAFCE2B09T3 | 2.3E-29 | Tc-EST-302 | 760 | 283 | 621 | AA879342 | AA879343 |

| Tc-huf-316 | C. elegans T24D8.5 gene | 3.7E-21 | Tc-EST-316 | 720 | 542 | 578 | AA874711 | AA874712 |

| Tc-huf-325 | O. volvulus L3CAN05C08SK | 7.4E-47 | Tc-EST-325 | 1,250 | 370 | 351 | AA879368 | AA879369 |

| Tc-vah-1 | C. elegans T05A10.5 venom allergen/ASP homolog | 4.6E-15 | Tc-EST-269 | 1,870 | 459 | 590 | AI 083044 | AI 083045 |

| Tc-vah-2 | B. malayi venom allergen/ASP homolog | 1.0E-13 | Tc-EST-303 | 1,600 | 550 | 699 | AI083048 | AI083049 |

| Tc-vah-3 | B. malayi venom allergen/ASP homolog | 4.7E-16 | Tc-EST-249 | 650 | 507 | 512 | AI083050 | AI083051 |

All cDNAs were isolated as single transcripts except vah-1 (three clones), vah-2 (two clones), and huf-001 (two clones).

In addition, we found three genes which show similarity to Ancylostoma secreted protein (ASP), which is associated with larval activation and development in other nematode species (10, 30, 31, 61). However, the T. canis stage from which the cDNA library was made is developmentally arrested and is not analogous to activated hookworm larvae. This gene family shows similarity to hymenopteran venom allergens and, in common with members reported for Brugia malayi and Onchocerca volvulus, has been designated vah (venom allergen homolog). Tc-vah-1, previously reported as Tc-CRISP (cysteine-rich secreted protein) by Liu (39a), is remarkable for containing two NC6/SXC domains in tandem with a VAH homology unit. Further characterization of these clones, Tc-vah-1, -2, and -3 is in progress (51a).

Other novel genes.

A total of 43 additional transcripts were found to have no significant similarities to any other sequences deposited in GenBank nr protein and dbEST databases. These were present at between one and four copies in the 261-member data set from T. canis and are designated not genes. Further studies on selected clones, such as not-018, for which antibodies to the protein product strongly recognize T. canis larval excretory-secretory antigens (61a) are ongoing.

Homologs of known genes.

Sixty-five genes with database homologs were found; these are listed in Table 3. There are 23 metabolic and respiratory enzymes but remarkably few structural proteins (only actin, calponin, and α-tubulin) and no DNA replication proteins, consistent with the arrested state of the larval parasite. The various categories of genes are described below.

TABLE 3.

Homology of T. canis ESTs with known genesa

| Gene | Gene product | Closest species | P | Clone no. | Insert size | Read

|

GenBank accession no.

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5′ | 3′ | 5′ | 3′ | Full-length verified sequence | ||||||

| Mucins | ||||||||||

| Tc-muc-1 | Mucin 1, surface coat TES-120 | T. canis | 6.3E-104 | Tc-EST-087b | 810 | 557 | 539 | AA583105 | AA907963 | U39815 |

| Tc-muc-2 | Mucin 2 | T. canis | 3.8E-49 | Tc-EST-130b | 990 | 612 | 694 | AA583106 | AA583107 | AF167707 |

| Tc-muc-3 | Mucin 3 | T. canis | 2.6E-36 | Tc-EST-162b | 1,010 | 603 | 555 | AA583111 | AA583112 | AF167708 |

| Tc-muc-4 | Mucin 4 | T. canis | 1.6E-45 | Tc-EST-186 | 560 | 553 | 586 | AA583108 | AA583109 | AF167709 |

| Lectins | ||||||||||

| Tc-ctl-1 | C-type lectin/TES-32 glycoprotein | Tc-EST-209 | 830 | 615 | 393 | AA874713 | AA874714 | AF041023 | ||

| Tc-ctl-2 | C-type lectin-2/variant of TES-32 | Tc-EST-036 | 780 | 596 | 618 | AI078880 | AI078881 | |||

| Tc-ctl-3 | C-type lectin-3/variant of TES-32 | Tc-EST-155 | 610 | 590 | 737 | AI080917 | AI080918 | |||

| Proteases and protease inhibitors | ||||||||||

| Tc-aep-1 | Asparaginyl endopeptidase | Homo sapiens | 3.5E-28 | Tc-EST-262 | 1,300 | 520 | 648 | AA825116 | AA875769 | |

| Tc-api-1 | Aspartyl proteinase inhibitor | C. elegans | 1.5E-09 | Tc-EST-096 | 650 | 570 | 638 | AA820019 | AA820020 | |

| Tc-cpl-1 | Cathepsin L cysteine proteinase | C. elegans | 2.3E-40 | Tc-EST-013 | 1,150 | 604 | 390 | AA563518 | AI078878 | U53172 |

| Tc-cpz-1 | Cathepsin Z proteinase precursor | O. volvulus | 1.2E-73 | Tc-EST-205 | 1,000 | 568 | 701 | AI080921 | AI080922 | AF143817 |

| Transporters and receptors | ||||||||||

| Tc-aat-1 | ADP/ATP translocase | C. elegans | 1.9E-69 | Tc-EST-041b | 750 | 515 | 663 | AA603955 | AA683466 | |

| Tc-acr-1 | Acetylcholine receptor (tar-1) | Trichostrongylus colubriformis | 1.2E-35 | Tc-EST-121 | 1,300 | 529 | 547 | AA835586 | AA835587 | |

| Tc-peb-1 | Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein (TES-26) | T. canis | 6.1E-76 | Tc-EST-164b | 1,200 | 406 | 459 | AA864177 | AA864178 | U29761 |

| Structural proteins | ||||||||||

| Tc-act-1 | Actin | C. elegans | 1.3E-81 | Tc-EST-097 | 1,450 | 524 | AA820021 | |||

| Tc-cap-1 | Calponin | Meloidogyne javanica | 4.2E-21 | Tc-EST-292b | 620 | 462 | 537 | AA875799 | AA907961 | |

| Tc-tua-1 | Tubulin alpha-3 chain | Cricetulus griseus | 1.5E-69 | Tc-EST-297b | 1,500 | 400 | 439 | AA979712 | AA907952 | |

| Protein synthesis and modification factors | ||||||||||

| Tc-efa-1 | Elongation factor 1a | C. elegans | 3.5E-84 | Tc-EST-300 | 1,600 | 498 | 572 | AA879374 | AA879375 | |

| Tc-efb-1 | Elongation factor 1b | C. elegans | 3.1E-42 | Tc-EST-081 | 830 | 355 | 756 | AA888759 | AA888760 | |

| Tc-pam-1 | Peptidyl-glycine alpha-hydroxylating monooxygenase | Drosophila melanogaster | 1.1E-07 | Tc-EST-200b | 420 | 385 | 357 | AA874705 | AI080786 | |

| Tc-pdi-1 | Protein disulfide isomerase | Gallus gallus | 5.9E-18 | Tc-EST-235 | 474 | 445 | 468 | AA874740 | AA874741 | |

| Tc-ppi-1 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | Mus musculus | 3.2E-15 | Tc-EST-019 | 1,200 | 319 | AA563572 | |||

| Tc-ptp-1 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase | M. musculus | 5.9E-49 | Tc-EST-118 | 1,590 | 589 | 628 | AA820013 | AA820014 | |

| Glycolysis, respiration, and other metabolic enzymes | ||||||||||

| Tc-aca-1 | Acetyl coenzyme A acetyltransferase | C. elegans | 9.8E-33 | Tc-EST-059 | 626 | 626 | 560 | AA610965 | AA907958 | |

| Tc-aki-1 | Adenylate kinase isoenzyme I | G. gallus | 9.2E-39 | Tc-EST-328 | 800 | 452 | 505 | AA873889 | AA873920 | |

| Tc-ald-1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | Bos bovis | 1.3E-45 | Tc-EST-299 | 1,700 | 559 | 360 | AA979715 | AA979716 | |

| Tc-ata-1 | Alanine aminotransferase | C. elegans | 4.0E-42 | Tc-EST-294 | 1,440 | 472 | 357 | AA875802 | AA875803 | |

| Tc-cgl-1 | Cystathionine gamma lyase | C. elegans | 6.4E-54 | Tc-EST-090 | 750 | 555 | 685 | AA583117 | AA583118 | |

| Tc-cyb-5 | Cytochrome b5 | H. sapiens | 4.5E-10 | Tc-EST-032 | 406 | 406 | AA569419 | |||

| Tc-fba-1 | Fructose biphosphate aldolase | O. volvulus | 2.1E-98 | Tc-EST-183 | 1,010 | 480 | 533 | AA915868 | AA915869 | |

| Tc-fdh-1 | Fumarate dehydrogenase precursor | H. sapiens | 1.7E-26 | Tc-EST-237 | 317 | 317 | 314 | AA285389 | AA874746 | |

| Tc-frb-1 | Fumarate reductase, cytochrome b small subunit | Ascaris suum | 2.9E-32 | Tc-EST-083 | 1,560 | 452 | 480 | AA888752 | AA888753 | |

| Tc-gdh-1 | Glutamate dehydrogenase | H. contortus | 4.7E-74 | Tc-EST-026 | 1,740 | 584 | 331 | AA568090 | AI078879 | |

| Tc-pcc-1 | Propionyl coenzyme A carboxylase | C. elegans | 8.6E-64 | Tc-EST-074 | 1,560 | 320 | 399 | AA888750 | AA888751 | |

| Tc-pck-1 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | A. suum | 4.4E-69 | Tc-EST-004 | 2,740 | 599 | 425 | AA470327 | AI374480 | |

| Tc-pgk-1 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | Schistosoma mansoni | 1.8E-41 | Tc-EST-109 | 1,400 | 576 | 805 | AA825117 | AA825118 | |

| Tc-sdi-1 | Succinate dehydrogenase iron-sulfur protein | A. suum | 3.0E-73 | Tc-EST-166 | 630 | 518 | 423 | AA864181 | AI374479 | |

| Tc-ubo-1 | NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase 18-kDa subunit | Bos taurus | 1.9E-39 | Tc-EST-201 | 521 | 501 | 480 | AA874708 | AI080786 | |

| Presumed mitochondrial proteins | ||||||||||

| Tc-atp-6 | ATP synthase A chain (protein 6) | A. suum | 1.9E-68 | Tc-EST-064 | 610 | 576 | 557 | AA612565 | AA979708 | |

| Tc-cox-2 | Cytochrome c oxidase II | A. suum | 7.1E-75 | Tc-EST-038 | 850 | 496 | 669 | AA569422 | AA569423 | |

| Tc-ubo-4 | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4L | A. suum | 2.6E-29 | Tc-EST-163 | 220 | 213 | 216 | AA864175 | AA864176 | |

| Antioxidants | ||||||||||

| Tc-sod-2 | Superoxide dismutase 2 | C. albicans | 1.5E-23 | Tc-EST-084 | 850 | 401 | 340 | AI078885 | AI078886 | |

| Tc-sod-3 | Superoxide dismutase 3 | Zea mays | 2.1E-18 | Tc-EST-100 | 900 | 449 | 608 | AI080774 | AI080775 | |

| Tc-sod-4 | Superoxide dismutase 4 | C. elegans | 3.6E-40 | Tc-EST-143 | 804 | 630 | 520 | AI080778 | AI080779 | |

| Tc-sod-5 | Superoxide dismutase 5 | C. elegans | 2.4E-39 | Tc-EST-266 | 900 | 731 | 730 | AI080782 | AI080783 | |

| Ribosomal proteins | ||||||||||

| Tc-rpl-10 | 60S ribosomal protein L10 | C. elegans | 8.6E-44 | Tc-EST-271 | 800 | 321 | 590 | AA875777 | AA875778 | |

| Tc-rpl-19 | 60S ribosomal protein L19 | M. musculus | 2.1E-60 | Tc-EST-244b | 900 | 439 | 555 | AA874749 | AA874750 | |

| Tc-rpl-3 | 60S ribosomal protein L3 | T. canis | 5.5E-60 | Tc-EST-257 | 500 | 498 | 457 | AA875762 | AI080789 | P49149 |

| Tc-rpl-31 | 60S ribosomal protein L31 | H. sapiens | 4.8E-49 | Tc-EST-072 | 580 | 440 | 491 | AA728649 | AA728650 | |

| Tc-rpl-37a | 60S ribosomal protein L37 | S. mansoni | 3.6E-34 | Tc-EST-267 | 400 | 372 | 381 | AA875772 | AA875773 | |

| Tc-rpl-7 | 60S ribosomal protein L7A | H. sapiens | 7.2E-29 | Tc-EST-054b | 750 | 513 | 560 | AA610961 | AA907956 | |

| Tc-rpl-9 | 60S ribosomal protein L9 | H. contortus | 1.1E-54 | Tc-EST-182b | 630 | 396 | 480 | AA873890 | AI080784 | |

| Tc-rpp-0 | 60S ribosomal protein p0 | C. elegans | 4.4E-35 | Tc-EST-122b | 1,100 | 476 | 552 | AA835588 | AA835589 | |

| Tc-rpp-2 | 60S ribosomal protein P2 | B. malayi | 3.6E-08 | Tc-EST-088 | 288 | 288 | 275 | AA907964 | AA907965 | |

| Tc-rps-4 | 40S ribosomal protein S4 | C. griseus | 4.1E-61 | Tc-EST-006 | 750 | 582 | AA563574 | |||

| Tc-rps-5 | 40S ribosomal protein S5 | C. elegans | 1.4E-70 | Tc-EST-215 | 610 | 571 | 675 | AA874719 | AA874720 | |

| Tc-rps-8 | 40S ribosomal protein S8 | H. sapiens | 7.4E-66 | Tc-EST-277 | 640 | 481 | 600 | AI080929 | AI080930 | |

| Tc-rps-9 | 40S ribosomal protein S9 | Rattus norvegicus | 8.6E-38 | Tc-EST-270 | 410 | 381 | AA875776 | |||

| Others | ||||||||||

| Tc-gep-1 | Granulin/epithelin precursor | M. musculus | 8.4E-31 | Tc-EST-141 | 1,000 | 654 | 625 | AA836692 | AA836693 | |

| Tc-hih-4 | Histone H4 | C. elegans | 3.5E-60 | Tc-EST-174 | 250 | 444 | 459 | AA557121 | AA873915 | |

| Tc-lah-1 | Lupus autoantigen homolog | C. elegans | 1.5E-22 | Tc-EST-177 | 450 | 607 | 520 | AI083048 | AI083049 | |

| Tc-mps-1 | Metallopanstimulin (=rps27) | Strongyloides ratti | 8.3E-41 | Tc-EST-178 | 1,430 | 367 | 400 | AA873918 | AA979709 | |

| Tc-ofm-1 | Olfactomedin (F11C3.2) | C. elegans | 1.6E-54 | Tc-EST-079b | 1,870 | 479 | 628 | AA728643 | AA728644 | |

| Tc-pth-1 | PC4/TIS7/“interferon-related protein” | M. musculus | 4.1E-20 | Tc-EST-075b | 1,440 | 616 | 299 | AA618627 | AI078882 | |

| Tc-tlp-1 | Tubby-like protein | H. sapiens | 1.6E-42 | Tc-EST-242 | 1,530 | 506 | 585 | AA874759 | AA874760 | |

Numerous sequences for which closest species listed is not a nematode show a higher BLASTX score with a C. elegans sequence for which there is either no assignation or which is described as similar to the nonnematode sequence given here. One ribosomal RNA gene (Tc-EST-052, 5′ AA610968, 3′ AA610969) was also identified.

Longest clone.

Mucins.

A mucin gene, Tc-muc-1, has previously been reported to be abundantly expressed by T. canis larvae (25). Consistent with this, seven clones of Tc-muc-1 were recorded (2.7% of the library). Three new mucin genes were found among the EST clones, each of which contains similar mucin domains and flanking NC6/SXC domains (26). The mucins differ in the composition of repeat motifs, and in the number and positions of NC6/SXC domains, and work in progress indicates that all are members of the TES-120 glycoprotein family associated with the parasite surface coat (40a).

C-type lectins.

One of the most abundant transcripts (16/261) was found to correspond to peptide sequence obtained from TES-32, a prominent secreted glycoprotein. These ESTs showed weak similarity to C-type lectins, but the homology was firmly established from full-length sequence. A detailed analysis of the functional lectin properties of TES-32/Tc-ctl-1 has been submitted for publication (42). Two variants of this sequence, designated Tc-ctl-2 and Tc-ctl-3, were also noted.

Proteases.

Proteolytic enzymes have been prominent in most studies of parasitic helminths at the biochemical (32) and molecular (43) levels. Three transcripts, with strong similarities to cathepsin L (41), cathepsin Z (43), and asparaginyl endopeptidase (19), were each present as single copies. Full-length sequences of the cathepsins L (41) and Z (22a) have been determined. A protease inhibitor similar to the aspartyl protease inhibitor of Ascaris and Brugia (Bm33) (21) was also isolated as a single clone.

Transporters and receptors.

One clone homologous to the acetylcholine receptors reported from other nematodes (24) has been isolated. A relatively frequent transcript (5/263) encodes Tc-PEB-1, a previously identified phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein (26) which is present in parasite secretions as a 26-kDa protein (TES-26).

Structural proteins.

Few structural proteins were identified in the EST data set, probably reflecting the arrested state of this parasite stage. Actin (67) and calponin (33) have been sequenced from other parasitic nematodes. For tubulins, most attention has focused on the β-tubulins (29), with which benzimidazole resistance is associated. Tc-tua-1 has strong similarity to α-tubulins from Haemonchus contortus (37) and C. elegans.

Protein synthesis and modification.

Two genes essential for protein synthesis (elongation factors 1a and 1b) were identified, as well as peptidyl-glycine alpha-hydroxylating monooxygenase, which modifies the C termini of peptides. Protein disulfide isomerase is a well-known requisite for protein folding and correct formation of disulfide bonds. In C. elegans, the pdi gene is found in an operon with one cyclophilin gene (55); a homolog from O. volvulus has also been characterized (65). Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase is similarly essential for correct protein conformation; the Tc-ppi-1 gene product is related to the FK506-binding proteins of mammals and not to the multigene cyclophilin family of peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerases described for C. elegans (55, 57).

Glycolysis, respiration, and other metabolic and citric acid cycle enzymes.

Some 18 distinct metabolic enzymes had very high levels of similarity to T. canis ESTs and represent the major metabolic pathways of glycolysis and aerobic respiration, as well as essential processes such as amino acid synthesis and degradation. Particularly prominent among these is the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit II (25/261 = 9.7% of all clones). As mitochondrial mRNAs are not polyadenylated, the presence of mitochondrial DNA-encoded sequences in the cDNA library is difficult to interpret quantitatively.

Antioxidants.

Oxidative stress is highly detrimental to both parasitic (54) and free-living (34) nematodes. In tissue-dwelling parasites, reactive oxygen intermediates from aggressive granulocytes may be countered by expression of antioxidants such as glutathione peroxidase and/or superoxide dismutase (SOD). Previous work characterized a SOD gene (Tc-sod-1) from T. canis larvae and showed that no glutathione peroxidase activity or gene sequence was detectable in this parasite (47). The EST data set contained seven clones encoding SOD isoforms, all quite distinct from Tc-sod-1 (approximately 66% divergence in protein sequence) and more similar to C. elegans gene F55H2.1. The seven clones represent four distinct isoforms each showing 10 to 20% divergence in nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence, including two-codon insertions/deletions. This level of divergence and the presence of triplet insertions/deletions led us to designate these four isoforms as separate genes, Tc-sod-2, -3, -4, and -5. Confirmation of this assignation is under way.

Ribosomal proteins.

Twenty ESTs (comprising 13 different genes; 8.4%) encode ribosomal proteins. This is close to the range found with EST projects for other nematodes; for example, 8.5% (1,339/15,811) of B. malayi ESTs deposited are ribosomal (12a), as are 5.0% (11/218) of Necator americanus ESTs (12a).

Other proteins.

Some ESTs had homology to mammalian proteins for which a function in nematodes is not obvious. Five particularly interesting findings were noted.

(i) Granulin/epithelin precursor (Tc-gep-1).

Granulins are synthesized as large (500- to 600-amino-acid) precursors from which are derived seven small (∼60-amino-acid) 12-cysteine peptides with growth factor-like activity (8, 9, 69). Mammalian and fish kidney epithelial cells are rich sources of these peptides (8, 60), as are human and rodent leukocytes, suggesting that granulins may fulfill cytokine-like functions (6). If this is so, the synthesis of a granulin homolog by T. canis larvae may be important in the interaction between parasite and the host immune system.

(ii) Lupus autoantigen homolog (Tc-lah-1).

The lupus autoantigen (also known as Sjögren syndrome type B antigen) is a highly conserved ribonucleoprotein which is a target of autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythrematosus (39). As autoimmune responses can be initiated by infectious agents (53), the expression of this homolog by T. canis may be significant. Similarly, O. volvulus expresses the RAL-1 product, which is homologous to the Sjögren syndrome type A antigen (48).

(iii) Olfactomedin (Tc-ofm-1).

A T. canis member of the olfactomedin gene family was found. The prototype gene encodes a 57-kDa glycoprotein in the extracellular mucus matrix of the olfactory neuroepithelium of frogs (66), but additional homologs are widely expressed in mammalian brain (35). Tc-ofm-1 shows maximum similarity to a C. elegans homolog. As T. canis larvae produce high levels of mucins, including those constituting the surface coat (25, 59), Tc-OFM-1 protein may be involved with mucus layers in this parasite.

(iv) PC4/TIS7/“interferon-related protein” (Tc-pth-1).

A T. canis gene which is similar to a mammalian product described as PC4 or TIS7, induced in cell lines by activators such as nerve growth factor or phorbol esters (63), has been isolated. The same mammalian gene has also been designated interferon-related protein, due to an erroneous deposition of this sequence in 1985 as murine beta interferon (accession no. J00424). We have named the T. canis gene, which bears no similarity to mammalian interferons, pth-1 (PC4/TIS7 homolog).

(v) Tubby-like protein (Tc-tlp-1).

Recently, a new multigene family related to the mouse gene tubby has been recognized (38). Mutations in tubby in the mouse result in obesity and degenerative changes in adult life; however, the existence of conserved homologs in nematodes (including C. elegans) and in plants indicates that this gene encodes a protein which fulfills a fundamental—and as yet unrecognized—function in all higher organisms.

Conclusion.

The analysis of expressed genes that we present here has achieved its aims of identifying a number of abundant transcripts, one of which (ctl-1) corresponds to a major secreted product and four of which (ant-003, -005, -030, and -034) represent novel gene sequences. We have also made the first steps toward a comprehensive gene catalogue of a biologically intriguing and clinically significant parasite, providing a resource and springboard for future studies.

The outcome of this study supports the proposition that the EST strategy is highly applicable to many metazoan organisms which have relatively large genome sizes (≥108 bp) (13, 14), especially where interest is focused on genes expressed at moderate to high levels. In addition, genes restricted to a life cycle stage can be identified in this manner. Further evidence for the success of this approach is seen in the Filarial Genome Project, which in 3 years has deposited in dbEST over 15,000 sequences, which are estimated to represent some 5,000 separate gene transcripts, or around 33% of the total gene complement of B. malayi (15, 62). The availability of the full genome sequence of C. elegans lends an exceptional opportunity to compare free-living and parasite gene sequences and structure, with the potential to identify adaptations requisite for parasitism at the molecular level. Along their evolutionary path, parasitic species must have developed a myriad of immune evasion mechanisms, and we anticipate that our study and others like it will be instrumental in identifying the novel immune evasion genes upon which parasite survival depends.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Medical Research Council for project grant support.

We thank Mark Blaxter for detailed critical comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams M D, Dubnick M, Kerlavage A R, Moreno R, Kelley J M, Utterback T R, Nagle J W, Fields C, Ventner J C. Sequence identification of 2,375 human brain genes. Nature. 1992;355:632–634. doi: 10.1038/355632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams M D, Kerlavage A R, Fleischmeann R D, et al. Initial assessment of human gene diversity and expression patterns based upon 83 million nucleotides of cDNA sequence. Nature. 1995;377(Suppl.):3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson P, Kimble J. mRNA and translation. In: Riddle D L, Blumenthal T, Meyer B J, Priess J R, editors. C. elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 185–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badley J E, Grieve R B, Bowman D D, Glickman L T, Rockey J H. Analysis of Toxocara canis larval excretory-secretory antigens: physicochemical characterization and antibody recognition. J Parasitol. 1987;73:593–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bateman A, Belcourt D, Bennet H, Lazure C, Solomon S. Granulins, a novel class of peptide from leukocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80908-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaver P C. Biology of parasites. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1966. pp. 215–227. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belcourt D R, Lazure C, Bennet H P J. Isolation and primary structure of the three major forms of granulin-like peptides from hematopoietic tissues of a telost fish (Cyprinus carpio) J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9230–9237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhandari V, Palfree R G E, Bateman A. Isolation and sequence of the granulin precursor cDNA from human bone marrow reveals tandem cysteine-rich granulin domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1715–1719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bin Z, Hawdon J, Qiang S, Hainan R, Huiqing Q, Wei H, Shu-Hua X, Tiehua L, Xing G, Zheng F, Hotez P. Ancylostoma secreted protein 1 (ASP-1) homologues in human hookworms. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;98:143–149. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bird D M, Riddle D L. A genetic nomenclature for parasitic nematodes. J Nematol. 1994;26:138–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blaxter M L. Caenorhabditis elegans is a nematode. Science. 1998;282:2041–2046. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a.Blaxter, M. L. Personal communication.

- 13.Blaxter, M. L., M. Aslett, J. Daub, D. Guiliano, and The Filarial Genome Project. Parasitic helminth genomics. Parasitology, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Blaxter M L, Guiliano D B, Scott A L, Williams S A. A unified nomenclature for filarial genes. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:416–417. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaxter M L, Raghavan N, Ghosh I, Guiliano D, Lu W, Williams S A, Slatko B, Scott A L. Genes expressed in Brugia malayi infective third stage larvae. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;77:77–93. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blumenthal T, Steward K. RNA processing and gene structure. In: Riddle D L, Blumenthal T, Meyer B J, Priess J R, editors. C. elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 117–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boguski M S, Lowe T M J, Tolstoshev C M. dbEST—database for “expressed sequence tags.”. Nat Genet. 1993;4:332–333. doi: 10.1038/ng0893-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chakrabati D, Reddy G R, Dame J B, Almira E C, Laipis P J, Ferl R J, Yang T P, Rowe T C, Schuster S M. Analysis of expressed sequence tags from Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;66:97–104. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J-M, Dando P M, Rawlings N D, Brown M A, Young N E, Stevens R A, Hewitt E, Watts C, Barrett A J. Cloning, isolation and characterization of mammalian legumain, an asparaginyl endopeptidase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8090–8098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.8090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Savigny D H. In vitro maintenance of Toxocara canis larvae and a simple method for the production of Toxocara ES antigen for use in serodiagnosis test for visceral larva migrans. J Parasitol. 1975;61:781–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dissanayake S, Xu M, Nkenfou C, Piessens W F. Molecular cloning and serological characterization of a Brugia malayi pepsin inhibitor homolog. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;62:143–146. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90191-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Sayed N M A, Alarcon C M, Beck J C, Sheffield V C, Donelson J E. cDNA expressed sequence tags of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense provide new insights into the biology of the parasite. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;73:75–90. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)00098-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a.Falcone, F. H., et al. Unpublished data.

- 23.Fan J, Minchella D J, Day S R, McManus D P, Tiu W U, Brindley P J. Generation, identification, and evaluation of expressed sequence tags from different developmental stages of the Asian blood fluke Schistosoma japonicum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252:348–356. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleming J T, Baylis H A, Sattelle D B, Lewis J A. Molecular cloning and in vitro expression of C. elegans and parasitic nematode ionotropic receptors. Parasitology. 1996;113:S175–S190. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000077969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gems D, Maizels R M. An abundantly expressed mucin-like protein from Toxocara canis infective larvae: the precursor of the larval surface coat glycoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1665–1670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gems D H, Ferguson C J, Robertson B D, Page A P, Blaxter M L, Maizels R M. An abundant, trans-spliced mRNA from Toxocara canis infective larvae encodes a 26 kDa protein with homology to phosphatidylethanolamine binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18517–18522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillespie S H. Human toxocariasis. J Appl Bacteriol. 1987;63:473–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1987.tb02716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glickman L T, Schantz P M. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of zoonotic toxocariasis. Epidemiol Rev. 1981;3:230–250. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guénette S, Prichard R K, Klein R D, Matlashewski G. Characterization of a β-tubulin gene and β-tubulin gene products of Brugia pahangi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;44:153–164. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90001-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawdon J M, Jones B F, Hoffman D R, Hotez P J. Cloning and characterization of Ancylostoma-secreted protein. A novel protein associated with the transition to parasitism by infective hookworm larvae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6672–6678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawdon J M, Narasimhan S, Hotez P J. Ancylostoma secreted protein 2: cloning and characterization of a second member of a family of nematode secreted proteins from Ancylostoma caninum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;99:149–165. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Healer J, Ashall F, Maizels R M. Characterization of proteolytic enzymes from larval and adult Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Parasitology. 1991;103:305–314. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000059588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irvine M, Huima T, Prince A M, Lustigman S. Identification and characterization of an Onchocera volvulus cDNA clone encoding a highly immunogenic calponin-like protein. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;65:135–146. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishii N, Fujii M, Hartman P S, Tsuda M, Yasuda K, Senoo-Matsuda N, Yanase S, Ayusawa D, Suzuki K. A mutation in succinate dehydrogenase cytochrome b causes oxidative stress and ageing in nematodes. Nature. 1998;394:694–697. doi: 10.1038/29331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karavanich C A, Anholt R R H. Molecular evolution of olfactomedin. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:718–726. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keddie E M, Higazi T, Unnasch T R. The mitochondrial genome of Onchocerca volvulus: sequence, structure and phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;95:111–127. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klein R D, Nulf S C, Alexander-Bowman S J, Mainone C B, Winterrowd C A, Geary T G. Cloning of a cDNA encoding alpha-tubulin from Haemonchus contortus. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;56:345–348. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90185-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleyn P W, Fan W, Kovats S G, Lee J J, Pulido J C, Wu Y, Berkemeier L R, Misumi D J, Holmgren L, Charlat O, Woolf E A, Tayber O, Brody T, Shu P, Hawkins F, Kennedy B, Baldini L, Ebeling C, Alperin G D, Deeds J, Lakey N D, Culpepper J, Chen H, Glücksmann-Kuis M A, Carlson G A, Duyk G M, Moore K J. Identification and characterization of the mouse obesity gene tubby: a member of a member of a novel gene family. Cell. 1996;85:281–290. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotzin B L. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Cell. 1996;85:303–306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39a.Liu, L. Personal communication.

- 40.Lloyd S. Toxocara canis: the dog. In: Lewis J W, Maizels R M, editors. Toxocara and toxocariasis: epidemiological, clinical and molecular perspectives. London, England: Institute of Biology; 1993. pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 40a.Loukas, A., M. Hintz, K. Tetteh, and R. M. Maizels. Unpublished data.

- 41.Loukas A, Selzer P M, Maizels R M. Characterisation of Tc-cpl-1, a cathepsin L-like cysteine protease from Toxocara canis infective larvae. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;92:275–289. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loukas, A., N. P. Mullin, K. K. A. Tetteh, L. Moens, and R. M. Maizels. A novel C-type secreted by a tissue-dwelling parasitic nematode. Curr. Biol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Lustigman S, McKerrow J H, Sha K, Lui J, Huima T, Hough M, Brotman B. Cloning of a cysteine protease required for the molting of Onchocerca volvulus third stage larvae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30181–30189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.30181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maizels R M, Gems D H, Page A P. Synthesis and secretion of TES antigens from Toxocara canis infective larvae. In: Lewis J W, Maizels R M, editors. Toxocara and toxocariasis: epidemiological, clinical and molecular perspectives. London, England: Institute of Biology; 1993. pp. 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maizels R M, Kennedy M W, Meghji M, Robertson B D, Smith H V. Shared carbohydrate epitopes on distinct surface and secreted antigens of the parasitic nematode Toxocara canis. J Immunol. 1987;139:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manger I D, Hehl A, Parmley S, Sibley L D, Marra M, Hillier L, Waterston R, Boothroyd J C. Expressed sequence tag analysis of the bradyzoite stage of Toxoplasma gondii: identification of developmentally regulated genes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1632–1637. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1632-1637.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matzilevich, D. A., C. Tripp, L. Tang, X. Ou, L. Matzilevich, M. K. Shaw, and R. M. Maizels. Cloning, expression and localization of Tc-sod-1, an extracellular superoxide dismutase from infective stage larvae of Toxocara canis. Submitted for publication.

- 48.McCauliffe D P, Zappi E, Lieu T-S, Michalak M, Sontheimer R D, Capra J D. A human Ro/SS-A autoantigen is the homologue of calreticulin and is highly homologous with onchocercal RAL-1 antigen and an aplysia “memory molecule.”. J Clin Investig. 1990;86:332–335. doi: 10.1172/JCI114704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCombie W R, Adams M D, Kelley J M, FitzGerald M G, Utterback T R, Khan M, Dubnick M, Kerlavage A P, Ventner J C, Fields C. Caenorhabditis elegans expressed sequence tags identify gene families and potential disease gene homologues. Nat Genet. 1992;1:124–131. doi: 10.1038/ng0592-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meghji M, Maizels R M. Biochemical properties of larval excretory-secretory glycoproteins of the parasitic nematode Toxocara canis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1986;18:155–170. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(86)90035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore J, Todorova V, Kennedy M W. A cDNA encoding ribosomal protein L3 from the parasitic nematode Toxocara canis. Gene. 1995;165:239–242. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00565-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51a.Murray, J., et al. Unpublished data.

- 52.Okimoto R, Macfarlane J L, Clary D O, Wolstenholme D R. The mitochondrial genomes of two nematodes, Caenorhabditis elegans and Ascaris suum. Genetics. 1992;130:471–498. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.3.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oldstone M B A. Molecular mimicry and autoimmune disease. Cell. 1987;50:819–820. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90507-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ou X, Thomas R, Chacón M R, Tang L, Selkirk M E. Brugia malayi: differential susceptibility to and metabolism of hydrogen peroxide in adults and microfilariae. Exp Parasitol. 1995;80:530–540. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Page A P. Cyclophilin and protein disulfide isomerase genes are co-transcribed in a functionally related manner in Caenorhabditis elegans. DNA Cell Biol. 1997;16:1335–1343. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Page A P, Hamilton A J, Maizels R M. Toxocara canis: monoclonal antibodies to carbohydrate epitopes of secreted (TES) antigens localize to different secretion-related structures in infective larvae. Exp Parasitol. 1992;75:56–71. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90122-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Page A P, MacNiven K, Hengartner M O. Cloning and biochemical characterization of the cyclophilin homologues from the free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem J. 1996;317:179–185. doi: 10.1042/bj3170179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Page A P, Maizels R M. Biosynthesis and glycosylation of serine/threonine-rich secreted proteins from Toxocara canis larvae. Parasitology. 1992;105:297–308. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000074229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Page A P, Rudin W, Fluri E, Blaxter M L, Maizels R M. Toxocara canis: a labile antigenic coat overlying the epicuticle of infective larvae. Exp Parasitol. 1992;75:72–86. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90123-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Plowman G D, Green J M, Neubauer M G, Buckley S D, McDonald V L, Todaro G J, Shoyab M. The epithelin precursor encodes two proteins with opposing activities on epithelial cell growth. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13073–13078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schallig H D F H, van Leeuwen M A W, Verstrepen B E, Cornelissen A W C A. Molecular characterization and expression of two putative protective excretory secretory proteins of Haemonchus contortus. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;88:203–213. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61a.Tetteh, K. Unpublished data.

- 62.The Filarial Genome Project. Deep within the filarial genome: an update on progress in the Filarial Genome Project. Parasitol. Today, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Tirone F, Shooter E M. Early gene regulation by nerve growth factor in PC12 cells: induction of an interferon-related gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2088–2092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Verdun R E, Di Paolo N, Urmenyi T P, Rondinelli E, Frasch A C C, Sanchez D O. Gene discovery through expressed sequence tag sequencing in Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5393–5398. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5393-5398.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilson W R, Tuan R S, Shepley K J, Freedman D O, Greene B M, Awadzi K, Unnasch T R. The Onchocerca volvulus homologue of the multifunctional polypeptide protein disulfide isomerase. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;68:103–117. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)00161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yokoe H, Anholt R R H. Molecular cloning of olfactomedin, an extracellular matrix protein specific to olfactory neuroepithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4655–4659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zeng W, Donelson J E. The actin genes of Onchocerca volvulus. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;55:207–216. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang B, Gallegos M, Puoti A, Durkin E, Fields S, Kimble J, Wickens M P. A conserved RNA-binding protein that regulates sexual fates in the C. elegans hermaphrodite germ line. Nature. 1997;390:477–484. doi: 10.1038/37297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhou J, Gao G, Crabb J W, Serrero G. Purification of an autocrine growth factor homologous with mouse epithelin precursor from a highly tumorigenic cell line. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10863–10869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]