Abstract

HIV stigma in health care disrupts the care continuum and negatively affects health outcomes among people living with HIV. Few studies explore HIV stigma from the perspective of health care providers, which was the aim of this mixed-methods, community-based participatory research study. Guided by the Health Stigma Discrimination Framework, we conducted an online survey and focus group interviews with 88 and 18 participants. Data were mixed during interpretation and reporting results. Stigma was low overall and participants reported more stigma among their colleagues. The main drivers of stigma included lack of knowledge and fear. Workplace policies and culture were key stigma facilitators. Stigma manifested highest through the endorsement of stereotypes and in the use of unnecessary precautions when treating people with HIV. This study adds to our understanding of HIV stigma within health care settings, with implications for the development of multi-level interventions to reduce HIV stigma among health care professionals.

Keywords: Stigma, HIV/AIDS, mixed methods, community-based participatory research, health care providers

Stigma, understood as “an attribute that is deeply discrediting within a particular social interaction,”1 [Goffman, 1963, p. 3] affects health and quality of life. Specifically, stigma contributes to poor mental health, increased substance use, social marginalization, and lower quality of life,2–5 and is particularly detrimental to care engagement when encountered within health care.6–9 The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework (HSD),10 a global, crosscutting framework informed by theory, research, and practice delineates the stigmatization process in the context of health. According to the HSD framework drivers of stigma are inherently negative (e.g., fear of infection, lack of awareness) and tend to occur at more proximal-ecological levels. Facilitators can either positively or negatively influence stigma (e.g., cultural norms, occupational safety standards, health policy) and tend to occur at more distal-ecological levels. Stigma drivers and facilitators lead to the application of stigma, or stigma marking. Once marked, stigma manifests through stigma experiences and stigma practices (i.e., stereotypes, prejudice, discriminatory attitudes, and behaviors), which influence health outcomes (e.g., incidence, morbidity, mortality, quality of life) for the marked populations.

HIV stigma, or negative beliefs, feelings, and attitudes towards people living with HIV,11 contributes to testing reluctance,12 poor anti-retroviral (ART) adherence,13 and lack of retention in HIV care14, 15 and, thus, suboptimal viral load suppression.16–19 Efforts to reduce HIV stigma within health care must be prioritized to ensure people living with HIV can fully engage in care without fear of stigma or discrimination. Recent studies on HIV stigma found widespread perpetuation of HIV stigma among surveyed health care professionals,20, 21 and a systematic review on stigma experienced by women living with HIV reported distancing, refusal of physical contact or double-gloving, and outright refusal of services among the stigmatizing and discriminatory behaviors by health care providers.22 Yet, the literature on HIV stigma in the U.S. is largely missing a focus on providers themselves.20, 23 Few studies have examined how health care professionals, from administrative staff to care providers, contribute to HIV stigma, and there is no standard measure of provider stigma in the literature.24 Theory-driven research that examines local manifestations of stigma within health care settings is needed to inform stigma-reduction efforts.

Research is needed to better understand the manifestation of stigma in health care in settings such as San Antonio, Texas. The HIV epidemic in the United States (U.S.) is concentrated in the South, an area with over half (51%) of all incident cases but only 38% of the population,25, 26 and HIV-stigma is notably high in the South.27 The high prevalence of HIV cases and HIV stigma in the region are driven by a combination of factors. Socioeconomic factors contribute to poorer health outcomes, disproportionate access to health care services prevents early intervention, and cultural factors contribute to driving stigma.27–29 Texas is among the states with the highest HIV prevalence, with an estimated 94,000 individuals living with HIV.30 As of 2018, 81% of people living with HIV in San Antonio had been diagnosed, 72% of those individuals were on ART, and 87% of those were virally suppressed.31 Like gaps in progress reflected in the broader Southern U.S.,32 these figures demonstrate the need to improve initial and ongoing engagement in HIV care. Community-based partnerships that bring together local HIV stakeholders are well-positioned to identify the needs of the community and leverage local resources to address those needs and transform communities.33

Methods

This paper describes a mixed-methods, community-based participatory research (CPBR) study. Community-based participatory research brings together community members, organizational representatives, and researchers as equitable partners in all parts of the research process.34 The present study was initiated by the End Stigma End HIV Alliance of San Antonio (ESEHA), a local, grassroots organization (comprising health care providers, representatives from local AIDS service organizations, advocates from the community living with HIV, and researchers) working to reduce HIV and HIV-related stigma, raise sexual health awareness, and promote mental health and resilience in San Antonio. Guided by CBPR principles, the overall goal of the present study was to assess the depth and breadth of HIV stigma among health care professionals (HCPs) in the San Antonio area, including clinicians, mental health providers, and non-licensed health professionals (e. g. office staff, eligibility specialists, patient navigators). The End Stigma End HIV Alliance of San Antonio aims to use this study’s findings to create and disseminate anti-stigma guidelines for health care professionals and area health care organizations.

Study procedure.

The ESEHA membership was involved as decision-makers throughout the research process. Specifically, ESEHA members 1) conceptualized the study and developed the research questions, 2) participated in the literature review and study design, 3) led study recruitment efforts, 4) were consulted throughout both qualitative and quantitative data analysis, and 6) are co-leading the dissemination of results. The main CBPR team was made up of seven individuals active in ESEHA including physicians, representatives of ASOs, advocates from the community, and researchers. This team met frequently (between 1–4 times per month) both in person and virtually to develop instruments, discuss study logistics, plan and collect data, and work through the analysis and dissemination.

We implemented a snowball sampling strategy to recruit participants. An email recruitment message detailing the study aims and eligibility criteria was distributed throughout the social and professional networks of ESEHA members, and recipients were encouraged to distribute it through their networks as well. Eligible participants were health care providers (HCPs), and other health care professionals (e.g. social workers, office managers, patient navigators.), 18 years of age or older, working in the San Antonio metropolitan area. The recruitment email contained a link to the study information sheet, which included blinding language to avoid priming participants. Interested individuals provided informed consent and were directed to the survey, which took approximately five minutes to complete. Upon completion, participants indicated interest in being entered into a pool of participants to be selected to receive a study incentive (a $25.00 gift card to a local grocery store) and/or being contacted for a future focus group with a subsample of participants. The survey was designed and conducted using Qualtrics,35 and was available online from December 2019 to February 2020.

From the pool of 88 survey respondents, 51 indicated that they would like to be contacted about participation in a focus group. Of those individuals, 34 corresponded with us to learn more about participation and to provide information about their eligibility and availability. A total of 22 were invited to participate in one of the three focus groups scheduled between January and February 2020, of which 18 attended. Focus groups were stratified by provider type including licensed prescribers (physicians, physician’s assistants, nurse practitioners); licensed, non-prescribing providers (registered nurses, licensed counselors, and social workers); and non-licensed health care professionals (office staff/managers, administration, eligibility specialists, patient navigators). Each group included between four and seven participants.

The focus group guide was informed by the HSD framework10 and developed in collaboration with ESEHA membership to explore topics related to stigma in health care. Before the focus groups began, participants provided written informed consent and completed a brief sociodemographic questionnaire. The focus groups were conducted by one member of the team with a student co-moderating. Additional team members were present during the sessions to take detailed notes and distribute supplemental materials. Focus groups lasted around 90 minutes. Upon completion, participants received an additional study incentive. The sessions were recorded verbatim with permission and then audio files were edited to remove identifying information before being transcribed by a third-party. Once returned, the transcripts were checked for accuracy and corrected where necessary. All study procedures were approved by the University of Texas at San Antonio Institutional Review Board.

Survey measures.

The online survey included socio-demographic items as well as questions related to occupation, years of experience, experience working with people living with HIV (PLHIV), and history of trainings related to providing care or services to HIV clients and diverse populations. HIV stigma was assessed using the Health care Provider HIV/AIDS Stigma Scale (HPASS). The HPASS is a psychometrically-valid measure containing 31 items across three subscales: prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination; these domains align with the HSD framework’s manifestations of stigma practices domains.10 All items are measured on a six-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6).

Items on HPASS are grouped by subscale and displayed in Figures 1, 2, and 3. The subscale stereotypes included 11 items measuring negative thoughts, cognitive schemas, or beliefs regarding PLHIV (Cronbach’s 〈 for full sample = 0.92). The prejudice subscale includes 13 items measuring emotionally-driven attitudes or reactions towards PLHIV. A single item was dropped from the original scale to improve reliability: “I would be comfortable working alongside another health care provider who has HIV.” Four items specific to clinic practices were omitted for participants in non-clinical roles (Cronbach’s 〈 for clinical providers = 0.89; Cronbach’s 〈 for non-clinical roles = 0.89). The final six-item subscale measures discrimination, or the behavioral response to prejudicial reactions towards PLHIV. One item specific to clinical practices was omitted for participants in non-clinical roles. Cronbach’s 〈 for clinical providers = 0.74; Cronbach’s 〈 for non-clinical roles = 0.96).

Figure 1.

Endorsement of HPASS Stereotypes Items. N=88

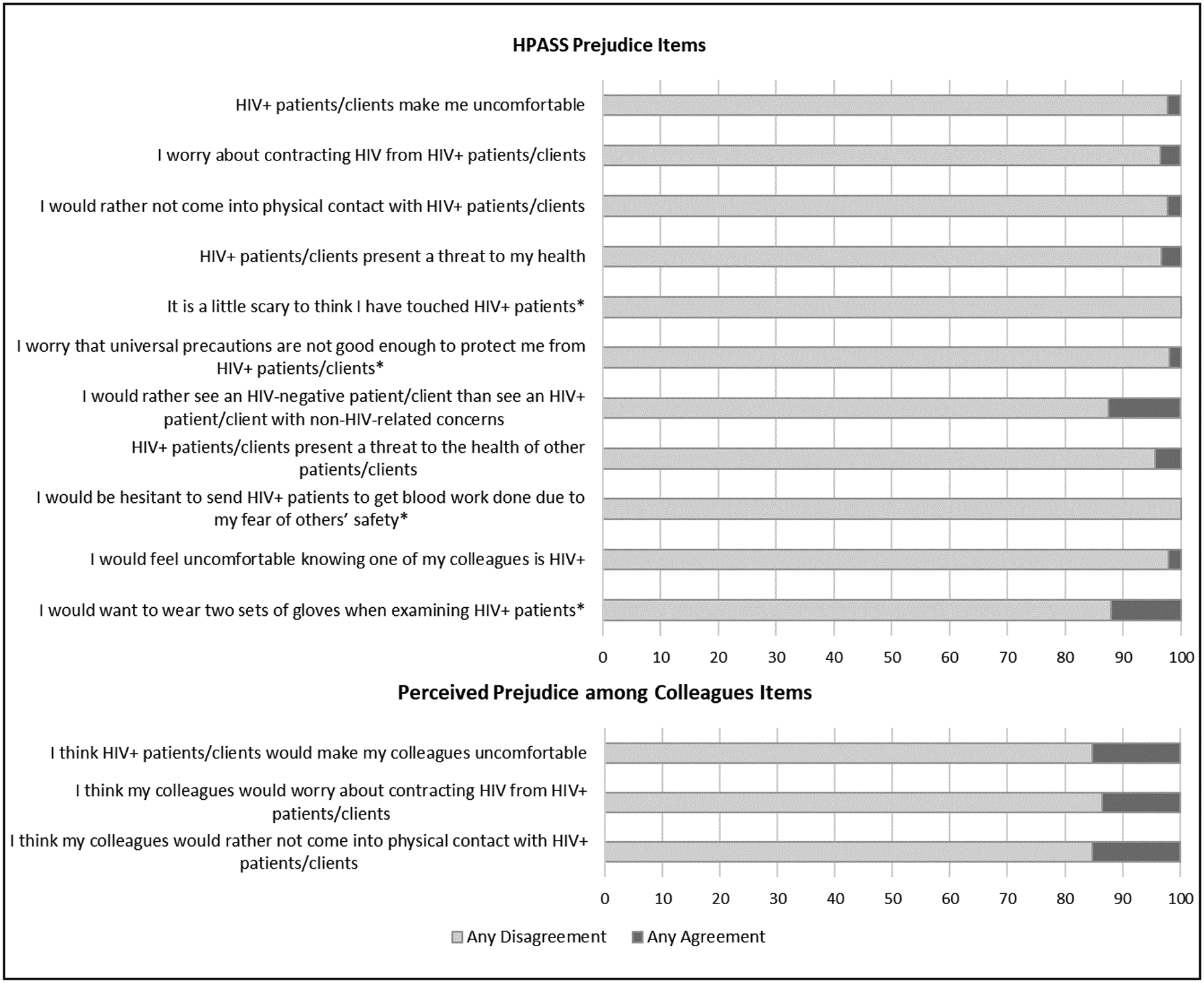

Note for figures 2–5: Any disagreement includes participants who responded slightly disagree, disagree, or strongly disagree; Any agreement includes participates who responded slightly agree, agree, or strongly agree.

Figure 2.

Endorsement of HPASS Prejudice Items and Perceived Prejudice among Colleagues Items, N=88

Figure 3.

Endorsement of HPASS Discriminatory Attitudes Items, N=83

In addition to the HPASS measure, eight items were constructed/adapted to assess perceived stigma among participants’ work colleagues (see Figure 4). These items originated from a similar community-based survey conducted by the Fast-Track Cities organizers in Phoenix, Arizona. One item assessed perceived HIV competence among coworkers: “I don’t think my colleagues are educated enough about working with HIV positive patients/clients.” Three items assessed perceived prejudice among coworkers (i.e., “I think HIV positive patients/clients would make my colleagues uncomfortable”). Four items assessed perceived stigmatizing behaviors among colleagues (e.g., “I have witnessed or heard about HIV positive patients/clients being refused treatment by other staff at the facility”). Response options were on a six-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). Since these items capture different manifestations of HIV stigma, they are presented separately in the results, rather than as one single scale.

Figure 4.

Endorsement of Perceived Stigmatizing Behaviors among Colleagues Items, n=58

Data analysis.

This study used a convergent mixed-methods design.36 Integration of methods occurred at the level of the study design as well as at the level of reporting and dissemination.37 Analysis of both data sets was directed by a specific theoretical framework and themes from the qualitative data and findings from statistical analysis were explored for convergence, which allowed us to contextualize findings from each dataset.

Quantitative data analyses were conducted in SPSS, v.25 (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).38 We ran descriptive statistics and frequencies to summarize participant characteristics. We created mean stigma scale scores for all participants, which accounted for missing data (e.g., items participants declined to answer or that were not applicable).39 We ran frequencies to display item-level endorsement of all stigma questions. For ease of interpretation, item-level frequencies were recoded into any disagreement (slightly disagree, disagree, strongly disagree) and any agreement (slightly agree, agree, strongly agree). While the overall aim of our quantitative analysis was descriptive in nature given the limited sample size, we conducted bivariate tests for between-group differences on stigma scores and types of training received by profession.

Data drawn from focus groups were analyzed using a thematic analysis technique.40 within our theoretical framework. Each transcript was completely coded using an iterative coding process and all coders met weekly to discuss new codes, potential themes, and discrepancies. First, two coders independently coded the transcripts deductively according to the HSD framework. During this initial round of coding, inductive codes drawn explicitly from the data were also created and applied to all relevant excerpts. After each transcript was coded completely, two separate coders reviewed all excerpts for consensus or re-coding and, in doing so, began to collate codes that represented larger thematic elements present within the HSD model constructs. We then engaged in a final round of coding to confirm thematic validity. During this final phase, some thematic codes were merged, some renamed, and others discarded.

Results

Participant characteristics.

Eighty-eight participants completed the online questionnaire, eighteen of whom participated in a focus group (see Table 1). The majority of participants in each phase of the study were women (approximately 77% in each). The majority of participants in both groups were White, Hispanic (survey: 43.2%; focus groups: 50%), followed by White, non-Hispanic (survey: 36.4%; focus groups: 33.3%). The survey pool included a larger number of Asian participants than focus groups (12.5% compared with 5.6%). Both participant groups included a small proportion of Black or African American, multiracial, or other racial groups. Although we had a larger proportion of lesbian, gay, and bisexual participants in the focus group (19.4% vs. 33.3%), the majority of participants identified their sexual orientation as heterosexual or straight (78.4% online survey, 66.7% focus group).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Online Survey, N=88 | Focus Groups, N=18 | |

|---|---|---|

| n/% | n/% | |

| Gender | ||

| Woman | 68 (77.30%) | 14 (77.80%) |

| Man | 18 (20.50%) | 4 (22.20%) |

| Genderqueer, non-binary, or gender non-conforming | 2 (2.30%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, Hispanic | 38 (43.20%) | 9 (50.00%) |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 32 (36.40%) | 6 (33.30%) |

| Asian | 11 (12.50%) | 1 (5.60%) |

| Black or African American | 3 (3.40%) | 1 (5.60%) |

| Multiracial | 3 (3.40%) | 1 (5.60%) |

| Other (not specified) | 1 (1.10%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Sexual Identity/Orientation | ||

| Straight | 69 (78.40%) | 12 (66.70%) |

| Lesbian or gay | 10 (11.40%) | 4 (22.20%) |

| Bisexual | 5 (5.70%) | 2 (11.10%) |

| Queer or Pansexual | 2 (2.30%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Don’t know/No response | 2 (2.30%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Provider-type | ||

| Prescribing healthcare providers | ||

| Physicians | 23 (26.10%) | 4 (22.20%) |

| Nurse practitioners | 5 (5.70%) | 3 (16.70%) |

| Pharmacist | 1 (1.10%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Non-prescribing licensed healthcare providers | ||

| Nurses | 22 (25.00%) | 5 (27.80%) |

| Counselors | 9 (10.20%) | 2 (11.10%) |

| Social workers | 6 (6.80%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Non-licensed administration/staff | ||

| Office/administrative staff | 8 (9.10%) | 4 (22.20%) |

| Administration/managerial staff | 5 (5.70%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Eligibility/intake specialists | 5 (5.70%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Other | 4 (4.50%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Years practicing medicine/ in health profession | ||

| Less than 2 years | 6 (8.20%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| 2–4 years | 6 (8.20%) | 1 (7.10%) |

| 5–10 years | 13 (17.80%) | 3 (21.40%) |

| 11–20 years | 20 (27.49%) | 5 (35.70%) |

| More than 20 years | 28 (38.40%) | 5 (35.70%) |

Note: In the online survey sample, multiracial included American Indian or Alaskan Native & White (n=2) and Black or African American or White (n=1); In the focus group sample, multiracial included American Indian or Alaskan Native & White (n=1)

Participants were categorized into the following three occupational categories: licensed prescribers/clinicians (survey: 33%, n=29; focus groups: 38.9%, n=7), licensed, non-prescribing providers (survey: 42%, n=37; focus groups: 38.9%, n=7), and administration/staff (survey: 25%, n=22; focus groups: 22.2%, n=4). The majority of the survey sample reported having ever worked in a facility serving PLHIV (76.1%), and nearly one third of the sample reported having ever worked in a facility specializing in HIV (30.7%); we did not collect this information from focus group participants.

Below, we present the primary findings of the study organized by the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework.10 Figure 5 presents our findings below mapped onto a modified model of the HSD. Qualitative themes are described and contextualized with illustrative quotations. The quantitative findings are integrated into the qualitative, where applicable, within the framework.

Figure 5.

Findings According to the Health Stigma Discrimination Framework

Drivers of stigma.

Knowledge deficits.

One prominent driver of stigma was lack of awareness related to HIV among both participants and their colleagues. Knowledge deficits included protocols around treating PLHIV generally, engaging in patient-education, and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Providers who worked outside of HIV care reported uncertainty about how an HIV diagnosis should affect treatment and care, especially when co-morbidities are present. As the participant narrative below demonstrates, this challenged providers’ capacity to educate patients and provide information about appropriate follow-up care:

This recently diagnosed man that I took care of was like, “So it [ART] just kills the virus? The drugs?” I’m like, “I’ll get back to you.” I have no idea. You know, I had no idea. And then I’ve gotta think, well, he’s on this and this and this. Is it gonna interact? What side effects do we need to look for? How long before it’s effective? When does he have to get his blood retest? I don’t know. And that’s what I went back to him with, a whole bunch of I don’t know. And, you know, that’s not what he was wanting to hear when he was upset.

—Non-prescribing provider

Additionally, while participants in each of the focus groups were aware of PrEP, most felt that they needed more information about it. Among prescribers specifically, education and training around PrEP was minimal. Results of the online questionnaire reflected these knowledge deficits. Nearly 30% of the sample had any agreement with the statement, “I don’t think my colleagues are educated enough about working with HIV positive patients/clients.”

Fear and discomfort.

Fear and discomfort were also driving stigma around treating PLHIV. When participants described their own fear, as opposed to that of their colleagues, it was framed as less pernicious and closely related to their knowledge deficits. For example, the participant below describes how increased knowledge eliminated her fear of HIV infection:

I trained in the 80s. And when I was a student, at that point, they didn’t even know how it was transmitted…I remember having tremendous fear…And so that definitely is gone, all of those fears and those things. I tried to keep myself educated…It’s a complete transformation from just absolute fear of the unknown to accumulating more and more and more knowledge that makes you more and more comfortable.

—Prescribing provider

Participants discussed their colleagues’ fear—sometimes regarded specifically as a phobia—as less benign than their own, explaining that despite widespread awareness of transmission routes, some health care providers still allow themselves an irrational fear of PLHIV as described below:

I mean, we don’t really think that we need to double glove so that we don’t get HIV from a patient we’re in casual contact with… But we allow ourselves to kind of go down that road or to entertain those thoughts…

—Non-prescribing provider

The difference between participants’ presentation of their own fear relative to that of co-workers reinforces results from our quantitative study in which participants reported more stigma among their colleagues than prejudice and discrimination in themselves.

Facilitators of stigma.

Insufficient education and training.

An absence of relevant content and training at the organizational level during professional education was a facilitator of the knowledge deficits driving stigma. Over the past two decades, there have been dramatic advances in knowledge of HIV etiology, epidemiology, and treatment. However, according to participants, there has not been sufficient knowledge transfer to ensure that the health care workforce, especially older professionals and non-licensed staff, are operating with up-to-date information. As the participant below describes, education and training systems are not adequate with regard to HIV:

I think all of us, we don’t have a mandatory continuing education [for HIV] like we do have for all sorts of diseases … and you know, there’s no mandatory sensitivity training between our recertifications that are necessary.

—Prescribing provider

This quotation illustrates a view endorsed by multiple focus group participants: that supplemental trainings are needed to ensure that no health care workers are perpetuating HIV stigma due to knowledge—or sensitivity—deficits.

Survey results echoed our finding of insufficient education and training related to HIV. Participants indicated topics they had ever received training in from a list of topics relevant to HIV and cultural competence. As shown in Figure 6, only about half of the sample had received training in key population stigma and discrimination (50%) and HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination (47.6%). Although occupational groups did not differ at a level of statistical significance, only 37% of prescribing health care providers (i.e., physicians, nurse practitioners, one pharmacist) reported HIV or key population stigma and discrimination training.

Figure 6.

HIV and other related training topics received, N=82

Policy.

Characteristics of the health care workplaces, operationalized through their policies, procedures, and protocols, facilitated stigma by either creating or preventing the conditions for stigma manifestations. In our focus groups, it was taken for granted that the health care systems participants work in—much like those responsible for educating and training the workforce—are built around a standard patient who does not encounter stigma related to HIV status. Additional training and education opportunities offered through the health care workplace were regarded as necessary but not sufficient. To ensure that patients did not have stigma experiences in health care, participants across the three focus groups stressed the need for policies and procedures to help preclude stigma coupled with education and training. One participant described such a policy in their workplace, saying:

When they would do the sensitivity training, [the employee] would sign off on it. So that’s my paper trail saying, okay you’ve been trained, you’re agreeing to do this. Once I hear the comment [a prejudicial statement], we would pull [the employee] aside, do the coaching. This is a verbal. And it starts to hurt because now it’s on record you’re not treating people as equals. So, I think once they sign that, we start that paper trail, it starts to become a little easier. You’re gonna get the resistance but then you’re gonna start to weed out these people that are just not good for your patients.

—Non-licensed professional

Policies, specifically enforceable policies with accountability measures were thought by participants to reduce the potential for stigma by either correcting the behavior or, failing that, removing a stigmatizing employee from the environment.

Here again, the quantitative portion of the study similarly documented an absence of anti-stigma and discrimination workplaces policies. Approximately 35% of the sample said they were aware of polices at their workplace to protect HIV clients from discrimination (35.4%). However, two thirds of the sample reported either not knowing of (54.9%) or not having such policies in their workplace (9.8%).

Workplace culture and norms.

The culture of a workplace or “how we do things around here,” is a product of the individuals who work together and an organization’s norms and values manifested in their specific policies, procedures, and protocols—or lack thereof. How workplace culture can create or reinforce stigma is evident in the example below, in which a participant describes a patient’s experience immediately after she was diagnosed with HIV:

She came in gripping that card [indicating a positive HIV test result]. When I talked to her, later, she said they couldn’t figure out what was wrong with her. There [were] people in the room, in-and-out, in-and-out. And she said the minute they diagnosed her with HIV, it just went to, like, crickets. She’s like, “Nobody wanted to come in that room.”

—Prescribing provider

Whether there is no post-diagnosis protocol to ensure that health care workers are not avoiding patients with HIV, or such a protocol exists but is not enforced, this organizational-level feature interacts with uninformed, fearful, and/or phobic employees to reinforce HIV stigma. In contrast, the example below demonstrates how a workplace culture can function as destigmatizing:

I’ve worked in a primary care place. And most of my patients knew they were HIV positive. They were stable, they were under the care of an HIV specialist. But their experience coming to me in our clinic was, “Wow. Y’all are okay? You’re fine? You don’t mind?” I’m like, “Why?” You know? Yes, of course we’re okay.” And they were so appreciative that we weren’t afraid of them.

—Prescribing provider

Further, a culture of normalizing HIV within the health care setting as in the example above may help mitigate the harm of previous exposure to HIV stigma within health care.

Our participants described a number of ways that organizational hierarchy can facilitate stigma as well. For one, participants agreed that a destigmatizing culture can originate from the top and filter down, mandated by higher-ups and supported by policies that can be enforced. The organizational hierarchy can also be leveraged to change norms in the workplaces. In our focus groups, multiple participants described having conversations with colleagues who worked under them about their prejudice and stigmatizing behaviors. One participant describes such a conversation, saying:

I tend to pull people aside and we talk about this and I let them know, okay, these are people living with HIV, it’s not AIDS. And I let them know when it does become AIDS.

—Non-licensed professional

However, it was also noted that engaging in corrective conversations can be uncomfortable, regardless of where one falls in the hierarchy. Even if one believes it necessary to correct a colleague, health care professionals may avoid doing so as it can risk their professional and social relationships:

The one person who said, you know, um, hey watch out, they have, they’re HIV positive was kind of an older nurse…that I really like, but he’ll give me that quick like, hey, doc just so you’re aware, you know. ‘Cause I think it’s just, he lived back when that’s what you did, I guess…And, and I don’t think he’s homophobic, I don’t think he’s mean-spirited that’s just what he says, you know… And if I didn’t know him so well, I probably would pull him aside and say, Hey, you know, you don’t need to tell me that, you wanna treat everyone like they do…”

—Prescribing provider

In the quotation above, an emergency medicine physician, despite having the support of his place in the organizational hierarchy, was too uncomfortable to correct a colleague below him on the hierarchy engaging in behavior that reinforces HIV stigma.

Manifestations of stigma: Stigma practices.

Stereotypes.

HIV patients are dishonest.

Among our focus group participants, the perception that HIV patients are dishonest was among the most pronounced stereotypes, equally endorsed among prescribing clinicians and nurses/counselors. The quotation below illustrates this stereotype:

I mean, ultimately, we need to be sure that providers are taking their history and understanding and giving the patient the freedom to really reveal –just like you were saying—patients don’t always reveal what they need to because they just want the medication now.

—Non-prescribing provider).

Participants discussed patient dishonesty in relation to disclosing one’s HIV status, medication adherence, and co-morbidities. Perceived reasons for patient dishonesty included being in denial of HIV status, fear of judgment, or as indicated in the quotation above, lying to get medication or something else they want. Our quantitative findings similarly demonstrated stereotypes endorsed by the larger online sample. Although endorsement was low, with participants largely disagreeing with most items, the stereotype subscale had the greatest endorsement (μ= 2.21, SD = 1.01) (see Table 2) of all the HPASS subscales.

Table 2.

Mean stigma scores and standard deviations for full sample and by occupational category

| Full sample (N=88) | Prescribing healthcare providers (n=29) | Nurses (n=39) | Counselors and social workers (n=17) | Administration/staff (n=20) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total HPASS | 1.71 (0.64) | 1.65 (0.58) | 1.82 (0.59) | 1.69 (0.67) | 1.69 (0.75) |

| HPASS stereotype | 2.21 (1.01) | 2.37 (1.16) | 2.37 (0.96) | 1.96 (0.80) | 2.05 (1.01) |

| HPASS prejudice | 1.33 (0.60) | 1.23 (0.33) | 1.45 (0.78) | 1.33 (0.50) | 1.33 (0.75) |

| HPASS discrimination | 1.62 (1.00) | 1.46 (0.66) | 1.62 (0.70) | 1.78 (1.36) | 1.68 (1.26) |

Note: HPASS = Health Care Provider HIV/AIDS Stigma Scale (HPASS); Prescribing healthcare providers include physicians, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists; Administration/staff include office administrators and managers, office/administrative staff, eligibility/intake specialists, and other health related professions.

Stereotype endorsement was slightly higher among prescribing providers and nurses compared with the other occupational categories, although differences were not statistically significant. At the item-level, nearly a quarter (24%) of participants endorsed the stereotype that PLHIV engage in risky behaviors despite knowing the risks (see Figure 1). Thirty-six percent of the sample had any agreement with the following stereotype: “HIV positive patients/clients who have acquired HIV through injection drug use are more at fault for contracting HIV than those who have acquired HIV through a blood transfusion.” In addition to the endorsement of stereotypes, these findings point to a degree of blame placed on PLHIV for their infection by health care professionals because of risk behaviors; 28% of the sample had any agreement with the statement “I think if people act responsibly, they will not contract HIV.”

Prejudice.

Dirty and contagious.

Participants agreed that some of their colleagues believed that PLHIV were “dirty.” This was, in part, linked to the prejudicial view that PLHIV are contagious, highlighting broader knowledge deficits about HIV transmission. One participant described this perspective by saying, “Everybody in their mind has this very 1980s, ‘Oh my God’ kind of point of view… you know, super contagious, everybody around you is gonna get it, only touch ‘em with gloved hands” (non-prescribing provider). While no survey participants agreed with the statement, “It is scary to think I’ve touched HIV positive patients,” approximately 15% reported any agreement that their colleagues “would worry about contracting HIV from patients” and “would rather not come in physical contact with HIV positive patients/clients” (see Figure 2). Focus group participants discussed that this fear often prevails despite widespread knowledge of HIV transmission, and may, as discussed below, originate from perceived violations of social norms around gender and sexuality more broadly:

The nurse who was coming in asked me, “Well, did you wipe down the seat she sat on?” … What’s goin’ on here, right? And you’re a nurse for God’s sakes… And it isn’t even about HIV specifically. It’s about a deviation from a really narrow norm that, even as a nurse, she couldn’t get past.

—Non-prescribing provider

Overall, the findings from the qualitative portion of the study indicated more prejudice than was reported in the quantitative portion; Table 2 reports the online survey sample mean for the HPASS prejudice subscale (μ= 1.33, SD = 0.60). Any agreement with items endorsing one’s own prejudice was less than 5% for most items (see Figure 2), including the statement “HIV positive patient/clients make me uncomfortable,” which was endorsed by only 2% of the sample. However, 15% of the sample felt this statement was true for their colleagues. These findings highlight a broader trend in both the qualitative and qualitative data where participants reported greater prejudice and HIV stigma in general among their colleagues than among themselves.

Discriminatory attitudes. Provider apathy and denial of responsibility. The stereotype that PLHIV were dishonest as described above, can lead to provider apathy towards patients and discriminatory attitudes towards patients who lie, justified by the belief that it is not the provider’s job to get the truth out of patients. The participant’s story below demonstrates this relationship:

I feel like I’ve given them time to feel comfortable with me, to sit down, to look them in the eye, to put my hand on their shoulder, and if they’re gonna lie to me and tell me the wrong thing, then I’m just gonna move on. I’m like, I can’t, you know. I’m gonna try to get you to believe, I’m here for you. And if you tell me the wrong answer, then that’s on you.

—Prescribing provider

A similar attitude—that it is someone else’s responsibility to provide care—was also present. The denial of responsibility was also observed in relation to the provision of PrEP. As noted, there was a knowledge deficit specific to PrEP among participants. In some cases, this was accompanied by a similar denial of responsibility for acquiring that knowledge, as exemplified in the following quotation:

Well, I just don’t know anything about it. I mean, my friends talk to me about it but it’s never come up in a situation at work. And I guess if somebody asked me about it, I would probably look it up and refer them out to somewhere else. So, I’m not equipped to do that.

—Non-prescribing provider

While referring patients out to other providers is this participant’s response, there was no consensus among participants about whose scope of practice PrEP provision fell under nor whether non-specialist providers even should prescribe PrEP.

Right to privacy.

Another discriminatory attitude was that PLHIV do not deserve the same right to privacy as other patients. This idea is driven by ignorance of transmission and prejudice that PLHIV are contagious or dirty, as demonstrated in the quotation below:

I’ve had to sit my staff down, and it’s mainly our CNAs [Certified Nursing Assistants] more than our nurses who have made very mean comments and say [things like], “Why didn’t you tell me they had AIDS? You know, I’m caring for them. You should tell me.” Well, I mean, it’s confidential. And everybody here … has tons of comorbidities. We’re not gonna [go] over each and every one. You take precautions like we would with everyone.

—Non-licensed professional

This discriminatory attitude in particular has the potential to result in health care discrimination in the form of breaches of patient confidentiality.

Discriminatory attitudes were also captured in the survey (see Table 2) (μ = 1.62, SD = 1.00), with participants asked to indicate agreement with statements about their perceived right to refuse to treat PLHIV for various reasons (e.g., to protect myself, if I feel uncomfortable, if I am concerned about legal liability). Survey respondents largely disagreed with these statements; however, as displayed in Figure 3, the percentage of the sample with any level of agreement with these statements was about 10% across items.

Stigmatizing behavior.

Gossip.

Gossip among health care providers and staff about HIV patients was a common stigmatizing behavior discussed in focus groups. For example, one participant in the ancillary staff focus group described concern that HIV clients will notice being gossiped about by staff who are uncomfortable being around PLHIV:

I don’t want the clients to feel that they are being whispered about or that, you know, as soon as they get up and leave the room, “Oh my goodness.” This isn’t, “Can you believe that or that?” The person assisting them is uncomfortable, but I know that there are managers that are uncomfortable with it that make fun of it.

— Non-licensed professional

Despite prominence in the focus group discussions, gossip about patients with HIV was infrequently reported in the survey, with only 10% of participants reporting overhearing colleagues gossip about PLHIV (see Figure 4).

Unnecessary precautions.

The discriminatory attitude that PLHIV have less of a right or expectation of privacy directly influences the behavior of health care professionals “warning” each other of a patient’s HIV status for no justifiable reason. This is one example of what we identify collectively as unnecessary precautions, as opposed to universal precautions. Health care workers double-gloving is another example. Taking these unnecessary precautions is driven by knowledge deficits, prejudice, and stereotypes, as demonstrated below:

I haven’t really seen any patients directly being treated poorly. In my observations, it’s been more of … “Oh, well that’s the patient that has HIV, double glove, be careful.” It’s a lot of awareness to everyone else. And I think it’s because no one knows or no one’s sure what the protocol is for a patient with HIV. So there’s this hypersensitivity and protection.

—Non-prescribing provider

Just over 10% of the survey sample reported any agreement with the statement “I would want to wear two sets of gloves when examining HIV positive patients” (see Figure 2). Nevertheless, the behavior was the subject of considerable discussion in each focus group. Taking unnecessary precautions was also linked to a lack of trust of HIV patients, stemming from the stereotype described above that HIV clients are dishonest. In an example of this below, the belief that patients are not forthcoming about their medical history resulted in a provider keeping a patient for two hours longer than necessary.

I probably hung on to that guy for two more hours than I would normally do for somebody who really didn’t have any medical problems. Just ‘cause I was thinking, is there something that I’m missing because he’s not telling me something? And I still don’t really know whether or not he was being truthful with me.

—Prescribing provider

Health care discrimination.

Focus group participants discussed several examples where stigmatizing behaviors led to health care discrimination for patients. For example, based on assumptions of non-compliance or violence among PLHIV with mental health issues, in one participants’ place of work, coverage is not provided for patients with multiple comorbidities:

We review everybody that comes in. So, the patient is a psych patient, behavioral with HIV or AIDS. We have a tendency to deny because we’re worried that they’re gonna be non-compliant, that they’re going to maybe hurt a staff member… we are very cautious.

——Non-licensed professional

This discriminatory behavior is driven by stereotypes about dishonesty as discussed, intersecting with stereotypes about mental illness. Ten percent of survey participants stated that they had witnessed or heard about HIV positive patients/clients being treated poorly by staff in their workplace, while 7% reported witnessing PLHIV being treated worse or refusing care in their facility or in others (see Figure 4).

Discussion

These data were collected as part of a mixed-methods, CPBR project aimed at understanding the breadth and depth of HIV stigma in health care in San Antonio, Texas. Our study fills two noted gaps in the literature by providing evidence of HIV stigma among health care providers from their direct perspective, and by extending this pool of participants to include other health professionals not directly involved in care provision (e.g., reception staff, administrators), who may be overlooked contributors to stigma within health care settings.23 We found no significant differences in stigma related to profession type. This finding demonstrates the necessity of addressing stigma not only among physicians and nurses but in all sectors of health care.

Another contribution of the present research is that it is theory-informed. The HSD framework10 guided the analysis of data collected through focus group interviews and the integration of findings from the online survey. Our study found the HSD framework to be a good fit for our data in explaining drivers, facilitators, and manifestations of HIV stigma, which supports its use for future research on both HIV-stigma and other stigmatized health conditions. The HSD framework was developed to be applicable to any health outcome and thus can be useful in better understanding stigmatized health outcomes such as COVID-19, mental health, and substance use, among others.

Through our analysis, we determined that lack of information related to HIV, along with fear of and discomfort caring for PLHIV, are prominent drivers of HIV stigma. Specifically, if one’s medical provider lacks basic information about their diagnosis, the message conveyed is that HIV is too difficult, complex, or outside the norm for a non-specialist provider to know about. These stigma drivers were thought to be less prevalent due to better training and more awareness of how HIV is transmitted in younger generations of health care providers. However, insufficient education and training at the institutional and organizational levels featured prominently as facilitators of HIV stigma.

Additional stigma facilitators concerned the policies, procedures, and culture of the health care workplace. Such characteristics can create or preclude the necessary conditions for stigma experiences and, thus, function as areas of opportunity to address HIV stigma at higher ecological levels. However, the manifestations of stigma we identified demonstrate how critical it is to address stigma at the interpersonal level across organizational actors, including clinical providers, non-clinical providers (e.g., counselors), and ancillary staff as well. In our study, we documented stereotypes, prejudice against PLHIV and discriminatory attitudes toward patients that lead to—and serve as justification for—health care professionals’ not developing the knowledge and skills needed to provide care tailored to HIV-positive patients. Many of the manifestations of stigma we found are commensurate with those from previous research including fear of contagion and related unnecessary precautions such as distancing and blaming those with HIV for contracting the virus.21, 41 While we documented provider perceptions of patients’ dishonesty, physician members of ESEHA note that providers may consider the possibility that a patient might be lying about stigmatized issues. Therefore, this perception may be informed by awareness of the impact of HIV stigma and not always reflective of HIV stigma in providers.

Our mixed-methods approach is a strength of this study, which allowed for the convergence of findings. Our quantitative findings provided insight into the overall prevalence of stigma manifestations among a larger community sample, while the qualitative data explored the context-specific drivers and facilitators that fuel stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors among health care professionals present in San Antonio. Taken together, our findings show that participants report greater prejudice and HIV stigma in general among their colleagues than among themselves. Knowing that self-reported stigma would be influenced by social desirability bias, we constructed specific questions about participants’ colleagues for both our qualitative and quantitative instruments to mitigate this bias. Nevertheless, our findings on the extent to which health care professionals reproduce and reinforce HIV stigma in the region is likely underreported.14

In addition to social desirability, limitations of our study include the use of a convenience sample, which limits the study’s generalizability and introduces the risk of selection bias. Our focus group participants may not be representative of the general population of health care professions or of the larger pool of respondents. Stigma scores of the general population of health care workers would perhaps be higher than we found in this sample of people from the professional networks of individuals working at AIDS service organizations or in HIV patient care. Although our quantitative aims were largely descriptive, our small sample size likely limited our ability to detect statistical differences by occupation or other characteristics, in addition to limiting study generalizability. While a strength of our study was our use of a validated measure of HIV stigma, the HPASS, we lack the ability to draw comparisons to previously published work; to our knowledge this is the first study to employ the HPASS, highlighting an area for future research. Further, some stigma items on the questionnaire may have low reporting simply because not all participants have worked in facilities where they commonly interact with PLHIV (e.g., I have witnessed gossip about PLHIV).

A major strength of the study lies in its foundation: CBPR. Given the contextual specificity of stigma,42 involvement from the community—members of ESEHA including local HIV organizational leaders, providers, and PLHIV—provided insider knowledge which strengthened the design of the study instruments, provided access to our population of interest, and improved the interpretation and reporting of our data within the local context through their analytic insights. Community-based participatory research work is meant to be action-oriented and translational.43 From the outset, the findings from this study were intended for translation and to inform the development of guidelines created by the community that would ultimately help eliminate HIV stigma through an intervention tailored to the needs of the community. Another strength is our mixed-methods approach which provides a more holistic understanding of HIV stigma in health care through the combined analysis of qualitative and quantitative data.

These findings have implications for improving health care for PLHIV in the Southern U.S. and elsewhere. Results demonstrate the necessity of multi-level strategies to target upstream organizational drivers and facilitators of stigma (i.e., lack of training/education in HIV, harmful workplace culture, a dearth of workplace policies and procedures to prevent and address stigma), while addressing interpersonal and individual-level stereotypes, prejudice, and discriminatory attitudes that result in stigmatizing experiences for PLHIV. Further, these results highlight the necessity of expanding the implementation of interventions across all job categories, not just among those directly involved in patient care. Finally, our findings demonstrate the importance of having an enforcement mechanism to address stigmatizing behavior, as education alone is insufficient. Collectively, such interventions can promote destigmatizing health care environments that are better able to keep PLHIV engaged in care.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources:

KMS was supported by a Mentored Research Scientist Career Development Award from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01MH121663. The funding supported only the study author and not the study directly. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funds to support participant incentive came from the End Stigma End HIV Alliance and the City of San Antonio Metro Health.

References

- 1.Goffman E Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edelman EJ, Lunze K, Cheng DM, et al. HIV Stigma and Substance Use Among HIV-Positive Russians with Risky Drinking. AIDS Behav. 2017. Sep;21(9):2618–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felker-Kantor EA, Wallace ME, Madkour AS, et al. HIV Stigma, Mental Health, and Alcohol Use Disorders among People Living with HIV/AIDS in New Orleans. J Urban Health. 2019. Dec;96(6):878–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How Does Stigma Affect People Living with HIV? The Mediating Roles of Internalized and Anticipated HIV Stigma in the Effects of Perceived Community Stigma on Health and Psychosocial Outcomes. AIDS Behav. 2017. Jan;21(1):283–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS Behav. 2006. Sep;10(5):473–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biancarelli DL, Biello KB, Childs E, et al. Strategies used by people who inject drugs to avoid stigma in health care settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019. May 1;198:80–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinsler JJ, Wong MD, Sayles JN, et al. The effect of perceived stigma from a health care provider on access to care among a low-income HIV-positive population. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007. Aug;21(8):584–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahmati-Najarkolaei F, Niknami S, Aminshokravi F, et al. Experiences of stigma in healthcare settings among adults living with HIV in the Islamic Republic of Iran. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010. Jul 22;13:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuvaraj A, Mahendra VS, Chakrapani V, et al. HIV and stigma in the healthcare setting. Oral Dis. 2020. Sep;26 Suppl 1:103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019. Feb 15;17(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and Transgender People. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/transgender/index.html.

- 12.Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, et al. Stereotypes about people living with HIV: implications for perceptions of HIV risk and testing frequency among at-risk populations. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012. Dec;24(6):574–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rintamaki LS, Davis TC, Skripkauskas S, et al. Social stigma concerns and HIV medication adherence. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006. May;20(5):359–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor BS, Fornos L, Tarbutton J, et al. Improving HIV Care Engagement in the South from the Patient and Provider Perspective: The Role of Stigma, Social Support, and Shared Decision-Making. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018. Sep;32(9):368–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris LM, Crawford TN, Kerr JC, et al. African American Older Adults Living with HIV: Exploring Stress, Stigma, and Engagement in HIV Care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(1):265–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16(3S2):18640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rueda S, Mitra S, Chen S, et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2016. Jul 13;6(7):e011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stockton MA, Giger K, Nyblade L. A scoping review of the role of HIV-related stigma and discrimination in noncommunicable disease care. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0199602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweeney SM, Vanable PA. The Association of HIV-Related Stigma to HIV Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of the Literature. AIDS Behav. 2016. Jan;20(1):29–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stringer KL, Turan B, McCormick L, et al. HIV-Related Stigma Among Healthcare Providers in the Deep South. AIDS Behav. 2016. Jan;20(1):115–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteside-Mansell L, Sockwell L, Martel I. HIV Stigma: A Clinical Provider Sample in the Southern U.S. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020. Jul 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darlington CK, Hutson SP. Understanding HIV-Related Stigma Among Women in the Southern United States: A Literature Review. AIDS Behav. 2017. Jan;21(1):12–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geter A, Herron AR, Sutton MY. HIV-Related Stigma by Healthcare Providers in the United States: A Systematic Review. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018. Oct;32(10):418–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexandra Marshall S, Brewington KM, Kathryn Allison M, et al. Measuring HIV-related stigma among healthcare providers: a systematic review. AIDS Care. 2017. Nov;29(11):1337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States 2010–2015. 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/.

- 26.Census Bureau U.S.. 2018 National and State Population Estimates. 2018. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2018/pop-estimates-national-state.html.

- 27.Reif S, Safley D, McAllaster C, et al. State of HIV in the US Deep South. J Community Health. 2017. Oct;42(5):844–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the Southern United States. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/cdc-hiv-in-the-south-issue-brief.pdf

- 29.Ingram L, Stafford C, Deming ME, Anderson JD, Robillard A, Li X. A Systematic Mixed Studies Review of the Intersections of Social-Ecological Factors and HIV Stigma in People Living With HIV in the U.S. South. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2019. May-Jun;30(3):330–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Texas Department of State Health Services. Epi Profile Section 2 - Texans Living with HIV in 2018. 2018. Available at: https://www.dshs.texas.gov/hivstd/reports/epiprofile/sec02.shtm.

- 31.Cities Fast-Track. Data visualization—San Antonio/Bexar County. 2018. Available at: https://www.fast-trackcities.org/data-visualization/san-antonio-bexar-county.

- 32.Colasanti JA, Armstrong WS. Challenges of reaching 90–90-90 in the Southern United States. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2019. Nov;14(6):471–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salimi Y, Shahandeh K, Malekafzali H, et al. Is Community-based Participatory Research (CBPR) Useful? A Systematic Review on Papers in a Decade. Int J Prev Med. 2012. Jun;3(6):386–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qualtrics. QualtricsXM. Provo, UT: Qualtrics, 2015. Available at: http://www.qualtrics.com. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Gutmann ML, et al. Advanced mixed methods research designs. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. 2003;209(240):209–40. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013. Dec;48(6 Pt 2):2134–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corp IBM. IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parent MC. Handling Item-Level Missing Data: Simpler Is Just as Good. The Counseling Psychologist. 2013;41(4):568–600. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development: sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Legal L HIV stigma and discrimination in the US: An evidence-based report. USA: Lambda Leg Mak case Equal. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. Aids. 2008. Aug;22 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S67–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhodes SD, Malow RM, Jolly C. Community-based participatory research: a new and not-so-new approach to HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010. Jun;22(3):173–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]