Abstract

Background:

The aim of the study was to analyze aortic-related outcomes after diagnosis of aortic dissection (AD), intramural hematoma (IMH), and penetrating aortic ulcer (PAU) from a population-based approach.

Methods:

Retrospective review of an incident cohort of AD, IMH, and PAU patients in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1995 to 2015. Primary end point was aortic death. Secondary end points were subsequent aortic events (aortic intervention, new dissection, or rupture not present at presentation) and first-time diagnosis of an aortic aneurysm. Outcomes were compared with randomly selected population referents matched for age and sex in a 3:1 ratio using Cox proportional hazards regression adjusting for comorbidities.

Results:

Among 133 patients (77 AD, 21 IMH, and 35 PAU), 57% were males, and mean age was 71.8 years (standard deviation, 14). Median follow-up was 10 years. Of 73 deaths among AD/IMH/PAU patients, 23 (32%) were aortic-related. Estimated freedom from aortic death was 84%, 80%, and 77% at 5, 10, and 15 years. There were no aortic deaths among population referents (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] for aortic death in AD/IMH/PAU, 184.7; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 10.3–3,299.2; P < 0.001). Fifty (38%) AD/IMH/PAU patients had a subsequent aortic event (aortic intervention, new dissection, or rupture), whereas there were 8 (2%) aortic events among population referents (all elective aneurysm repairs; adjusted HR for any aortic event and aortic intervention in AD/IMH/PAU patients, 33.3; 95% CI, 15.3–72.0; P < 0.001 and 31.5; 95% CI, 14.5–68.4; P < 0.001, respectively). After excluding aortic events/interventions 14 days of diagnosis, AD/IMH/PAU patients remained at increased risk of any aortic event (adjusted HR, 10.8; 95% CI, 3.9–29.8; P < 0.001) and aortic intervention (adjusted HR, 9.6; 95% CI, 3.4–26.8; P < 0.001). Among those subjects with available follow-up imaging, the risk of first-time diagnosis of aortic aneurysm was significantly increased for AD/IMH/PAU patients when compared with population referents (adjusted HR, 10.9; 95% CI, 5.4–21.7; P < 0.001 and 8.3; 95% CI, 4.1–16.7; P < 0.001 for thoracic and abdominal aneurysms, respectively) and remained increased when excluding aneurysms that formed within 14 days of AD/IMH/PAU (adjusted HR, 6.2; 95% CI, 1.8–21.1; P = 0.004 and 2.8; 95% CI, 1.0–7.6; P = 0.040 for thoracic and abdominal aneurysms, respectively).

Conclusions:

AD/IMH/PAU patients have a substantial risk of aortic death, any aortic event, aortic intervention, and first-time diagnosis of aortic aneurysm that persists even when the acute phase (≤14 days after diagnosis) is uncomplicated. Advances in postdiagnosis treatment are necessary to improve the prognosis in these patients.

INTRODUCTION

Aortic dissection (AD), intramural hematoma (IMH), and penetrating aortic ulcer (PAU) are dreaded aortic pathologies. Despite the distinct characteristics of each of these entities, they all involve a disruption of the media layer of the aortic wall and may progress from one to another,1 sharing a significant risk of acute and chronic aortic-related morbidity and mortality.2 For acute Stanford type A and type B dissection, the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection reported an in-hospital mortality of 22% and 14%, respectively.3 At 3 years, almost 25% of those with type B dissection discharged alive will additionally have died.4 In both, type A and type B dissection, aortic events are the most common cause of death.5–8 Acute survival of patients presenting with IMH and PAU may be slightly better than for those with AD (9–13%),9,10 but poor long-term survival has been reported in an institutional series.10 In addition, patients with chronic AD, IMH, and PAU carry a significant risk of subsequent aortic events, including recurrent dissection, rupture, and aneurysmal degeneration, often requiring intervention. However, the true risk of late aortic death and subsequent aortic events among patients with these aortic pathologies is not well known. Most long-term data come from registries or single centers4,10–12 and may be biased by limited follow-up compliance of these patients13 and lack of mortality data.

We have previously characterized the incidence of AD, IMH, and PAU and its associated mortality in a population-based approach using the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP, Olmsted County, Minnesota residents)14 and evaluated this incidence cohort with regard to nonaortic cardiovascular events.15 The objective of the present study was to quantify the risk of aortic death, subsequent aortic events, and aortic aneurysm formation after AD, IMH, and PAU. By comparing AD, IMH, and PAU patients with referent subjects from the same population, we aimed to approximate the expected increased risk of AD, IMH, and PAU patients to characterize the early and late impact of these aortic pathologies on patients’ lives.

METHODS

The detailed identification process of the incidence cohort we assessed is described elsewhere.14,15 In brief, we used the resources of the REP, a unique collaboration of health care providers linking together medical records of virtually all residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota.16,17 This permits the identification of incident diagnoses at a population level and allows follow-up of patients across providers. Within the REP, adult residents (18 years and older) with a new diagnosis of AD, IMH, or PAU from 1995 to 2015 were identified using International Classification of Disease codes (ICD, Ninth and Tenth revision) and Hospital Adaptation of the International Classification of Diseases codes (HICDA, second edition). Study inclusion required imaging confirmation of the diagnosis. For immediate decedents, AD/IMH/PAU had to be confirmed by autopsy or be the primary diagnosis on the death certificate. AD, IMH, and PAU were defined based on standard criteria used in current guidelines1 and classified as acute (≤14 days of symptom onset), subacute (15–90 days), chronic (>90 days), or unknown presentation (unknown date of onset of the pathology). AD was classified using the De Bakey and the Stanford classification, whereas IMH was classified using the Stanford classification only. PAU was classified by anatomic location.

The AD/IMH/PAU cohort was compared with randomly selected Olmsted County population referents matched for age and sex. As previously described, a matching ratio of 3:1 was chosen based on a sample size calculation to detect a minimum hazard ratio (HR) for all-cause death of 1.95 with an alpha of 0.05 and power of 0.8.14 For population referents, the diagnosis date of the matched AD/IMH/PAU patient was set as the index date to differentiate preexisting conditions from outcome events. Comorbidities were assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index.18 Charlson comorbidities were identified using predefined ICD and HICDA codes. Assignment of a comorbidity required 2 occurrences of a corresponding code within 5 years before the date of AD/IMH/PAU diagnosis (or the index date in population referents).19 All individuals were censored on December 31, 2015 for outcomes.

Assessment of Aortic Death

Primary end point was aortic death. Dates and causes of death were obtained from death certificates available through the REP, which collates up to date information on in state and out of state deaths from multiple sources.17 For a minority of subjects with missing vital status information (e.g., because of migration), an institutionally approved Internet research location service (Accurint; www.accurint.com) was used, and death certificates requested where permissible as per state laws. For 3 AD/IMH/PAU patients and 3 population referents known to have died out of state, deaths certificates could not be obtained. Causes of death retrieved from death certificates were cross checked with medical records. Aortic death was defined as death because of rupture, ischemic complications, surgical complications related to AD/IMH/PAU treatment, and other aortic-related causes (not specified).

Assessment of Subsequent Aortic Events

The secondary end point of a subsequent aortic event included aortic intervention and new dissection or rupture that was not present at initial presentation. All operative reports of AD/IMH/PAU patients and population referents were screened for aortic interventions. Medical records and follow-up imaging were reviewed to identify new dissection (including progression from IMH, retrograde Stanford type A dissection, new Stanford type B dissection after repair of De Bakey type II dissection) and rupture. Only first aortic interventions, first subsequent dissections, or ruptures were considered. Events were analyzed as a composite end point (any aortic event) and by event type separately.

Assessment of New Aneurysm Formation

To identify aneurysm formation during follow-up, available imaging was reviewed for AD/IMH/PAU patients and population referents. This included any contrast or noncontrast computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging with visualization of the entire thoracic or abdominal aorta, respectively, and a slice thickness of 5 mm or less. Abdominal ultrasound was included if performed for aneurysm screening or if providing satisfactory evaluation of the abdominal aorta in 2 planes when performed for other reasons. As there was no standardized imaging assessment for AD/IMH/PAU patients during the study period, imaging was at the discretion of the provider at the time (frequency and sections of the aorta imaged). This usually correlated with the acuity of the aortic pathology, extent of disease, and stability over time. Population referents had no standard aneurysm screening, and imaging was often performed for other reasons.

The maximum diameter of the ascending aorta, aortic arch, descending aorta, and abdominal aorta was measured outer-to-outer wall perpendicular to the course of the aorta using an electronic caliper. Cutoff values to define an aneurysm of the thoracic aorta were based on previously reported mean values for normal thoracic aortic diameters.20 Mean normal diameters in each aortic segment were multiplied by 1.5, resulting in cutoff values of ≥4.5 cm for the ascending aorta (aortic valve to innominate artery), ≥4 cm for the aortic arch (innominate artery to left subclavian artery), and ≥3.7 cm for the descending aorta (left subclavian artery to diaphragm). For the abdominal aorta, a generally accepted cutoff value of ≥3 cm was used to define an aneurysm.21 Any first-time aneurysm formation, associated or not associated with the initial AD/IMH/PAU pathology, was noted. If no aneurysm formation was documented, subjects were censored on the date of the last available imaging or at death. Subjects with known or repaired aneurysm before AD/IMH/PAU diagnosis (or the index date in referents) were excluded from the analysis as were those with no available follow-up imaging. For excluded AD/IMH/PAU patients, matched population referents were excluded likewise to maintain the age and sex matching; for excluded referents, their matched AD/IMH/PAU patient was excluded only if all 3 referent subjects had been excluded because of prior aneurysm or lack of imaging. Because of the variation in the availability of thoracic and abdominal imaging, analysis was performed for thoracic and abdominal aneurysm formation separately.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics including mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (range) and frequencies (percent) were used to describe baseline characteristics and descriptive outcomes. Univariate associations of baseline characteristics between AD/IMH/PAU patients and population referents were made using Student’s t-test for continuous and χ2 test for categorical variables with Fisher’s exact test for low-frequency events. Subtypes AD, IMH, and PAU were compared using analysis of variance for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. End points were evaluated as time to event using life tables and Kaplan-Meier plots. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to compare AD/IMH/PAU patients and population referents, adjusting for age, sex, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index. For all outcomes, analyses were performed in 2 ways: by including all events from the time of diagnosis forward and by including events > 14 days after diagnosis only to assess for the risk of aortic events beyond the acute phase. P values <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and SAS software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the 2 major health care providers in the REP, Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center. All individuals included in the study had already provided informed consent for the use of their medical records in research as part of the REP.16

RESULTS

One hundred thirty-three AD/IMH/PAU patients were identified; 77 had AD, 21 IMH, and 35 PAU. Mean age at diagnosis was 71.8 years (SD, 14.1), and 57% were males. Baseline characteristics of the AD/IMH/PAU cohort and population referents are displayed in Table I (some of these data have been published before14,15). Median follow-up was 10.2 years for AD/IMH/PAU patients and 10.1 years for matched population referents.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the AD/IMH/PAU cohort and population referents

| Referents |

AD/IMH/PAU |

AD/IMH/PAU subtypes |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n = 399 (%) | n = 133 (%) | P a | AD; n = 77 (%) | IMH; n = 21 (%) | PAU; n = 35 (%) | P |

|

| |||||||

| Age (years); mean (SD) | 71.8 (14.1) | 71.8 (14.1) | 1.0 | 68.9 (15.6) | 73.5 (11.5) | 77.1 (10.0) | 0.015 |

| Male gender | 76 (57.1) | 76 (57.1) | 1.0 | 46 (59.7) | 11 (52.4) | 19 (54.3) | 0.770 |

| Charlson | 1.7 (2.1) | 2.6 (2.6) | <0.001 | 2.1 (2.2) | 2.8 (2.6) | 3.7 (3.2) | 0.006 |

| Comorbidity Index; mean (SD) | |||||||

| Thoracic aneurysm | |||||||

| Prior known | 5 (1.2) | 11 (8.3) | <0.001 | 6 (7.8) | 2 (9.5) | 3 (8.6) | 0.912 |

| Prior repair | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.5) | <0.001 | 1 (1.3) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0.359 |

| Abdominal aneurysm | |||||||

| Prior known | 7 (1.7) | 6 (4.5) | 0.100 | 3 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.6) | 0.423 |

| Prior repair | 3 (0.7) | 11 (8.3) | <0.001 | 6 (7.8) | 1 (4.8) | 4 (11.4) | 0.677 |

| Acuity of presentationb | — | <0.001 | |||||

| Acute | — | 79 (59.4) | 52 (67.5) | 17 (81.0) | 10 (28.6) | ||

| Subacute | — | 4 (3.0) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.9) | ||

| Chronic | — | 3 (2.3) | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | ||

| Unknown | — | 47 (35.3) | 21 (27.3) | 3 (14.3) | 23 (65.7) | <0.001 | |

| Stanford classification | — | <0.001 | |||||

| Type A | — | — | 45 (58.4) | 5 (23.8) | — | ||

| Type B | — | — | — | 32 (41.6) | 16 (76.2) | — | — |

| De Bakey classification | — | — | |||||

| Type I | — | — | 24 (31.2) | — | — | ||

| Type II | — | — | 21 (27.3) | — | — | ||

| Type IIIa | — | — | 8 (10.4) | — | — | ||

| Type IIIb | — | — | 24 (31.2) | — | — | — | |

| Anatomic localization | — | ||||||

| Thoracic | — | — | — | — | 18 (51.4) | ||

| Abdominal | — | — | — | — | 17 (48.6) | ||

| Connective tissue disease | — | 8 (6.0) | — | 8 (10.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.052 |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | — | 3 (2.3) | — | 1 (1.3) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.9) | 0.388 |

| Iatrogenic | — | 7 (5.3) | — | 6 (7.8) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.281 |

P values for comparisons between the AD/IMH/PAU and the referent cohort do not account for matching.

Acute: ≤14 days of symptom onset; subacute: 15–90 days;and chronic: >90 days.

Aortic Death

During follow-up, 73 (55%) of 133 subjects in the AD/IMH/PAU cohort died compared with 144 (36%) of 399 in the referent cohort. Aortic death occurred in 23 (32%) of 73 AD/IMH/PAU decedents because of rupture (n = 12; 52%), complications after surgical treatment of AD/IMH/PAU (n = 5; 22%), ischemic complications (n = 4; 17%), and unspecified aortic causes (n = 2; 9%). Estimated freedom from aortic death in AD/IMH/PAU patients at 5, 10, and 15 years was 84%, 80%, and 77%. No aortic deaths occurred in population referents (adjusted HR for aortic-related death in AD/IMH/PAU, 184.7; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 10.3–3,299.2; P < 0.001). Fifteen (11%) deaths occurred within 14 days of AD/IMH/PAU diagnosis, thereof, 13 (87%) were aortic related. Late deaths (>14 days) were because of aortic causes in 10 (17%) of 58. For those surviving the first 14 days after AD/IMH/PAU diagnosis, estimated freedom from aortic death at 5, 10, and 15 years was 93%, 85%, and 85% (adjusted HR for aortic death among AD/IMH/PAU, 67.6; 95% CI, 3.3–1,401.7; P = 0.006). Among subtypes, only AD was associated with an increased risk of aortic-related death both when including and excluding acute deaths (Table II; subtype analyses not adjusted for the Charlson comorbidity Index because of low event numbers).

Table II.

Risk of aortic death in AD/IMH/PAU patients versus matched population referents

| All AD/IMH/PAU patients (n = 133) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All events |

Excluding acute eventsa |

|||||||||||

| AD/IMH/PAU |

Referents |

AD/IMH/PAU vs. referents |

AD/IMH/PAU |

Referents |

AD/IMH/PAU vs. referents |

|||||||

| Event | At risk | Events | At risk | Events | HR (95% CI) | P | At risk | Events | At risk | Events | HR (95% CI) | P |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Aortic death | 133 | 23 | 399 | 0 | 184.7 (10.3–3,299.2) | <0.001 | 118 | 10 | 354 | 0 | 67.6 (3.3–1,401.7) | 0.006 |

| Any aortic event | 133 | 50 | 399 | 8 | 33.3 (15.3–72.0) | <0.001 | 83 | 13 | 249 | 6 | 10.8 (3.9–29.8) | <0.001 |

| Aortic intervention | 133 | 48 | 399 | 8 | 31.5 (14.5–68.4) | <0.001 | 83 | 12 | 249 | 6 | 9.6 (3.4–26.8) | <0.001 |

| AD (n = 77)b | ||||||||||||

| Aortic death | 77 | 16 | 231 | 0 | 111.7 (6.1–2,030.6) | 0.001 | 65 | 5 | 195 | 0 | 33.9 (1.4–801.1) | 0.029 |

| Any aortic event | 77 | 34 | 231 | 4 | 47.6 (16.4–137.8) | <0.001 | 39 | 7 | 117 | 2 | 18.2 (3.5–94.2) | <0.001 |

| Aortic intervention | 77 | 33 | 231 | 4 | 44.8 (15.5–130.0) | <0.001 | 39 | 6 | 117 | 2 | 14.9 (2.8–79.1) | 0.002 |

| IMH (n = 21)b | ||||||||||||

| Aortic death | 21 | 4 | 63 | 0 | 30.5 (1.2–769.2) | 0.038 | 20 | 3 | 60 | 0 | 23.6 (0.8–669.9) | 0.064 |

| Any aortic event | 21 | 9 | 63 | 3 | 14.5 (3.8–55.0) | <0.001 | 16 | 5 | 48 | 3 | 7.3 (1.7–31.7) | 0.008 |

| Aortic intervention | 21 | 9 | 63 | 3 | 14.5 (3.8–55.0) | <0.001 | 16 | 5 | 48 | 3 | 7.3 (1.7–31.7) | 0.008 |

| PAU (n = 35)b | ||||||||||||

| Aortic death | 35 | 3 | 105 | 0 | 28.4 (0.9–878.7) | 0.055 | 33 | 2 | 99 | 0 | 17.5 (0.4–696.6) | 0.127 |

| Any aortic event | 35 | 7 | 105 | 1 | 24.5 (3.0–199.9) | 0.003 | 28 | 1 | 84 | 1 | 3.2 (0.2–51.8) | 0.408 |

| Aortic intervention | 35 | 6 | 105 | 1 | 21.2 (2.5–176.6) | 0.005 | 28 | 1 | 84 | 1 | 3.2 (0.2–51.8) | 0.408 |

Including deaths >14 days of diagnosis only.

Unadjusted for the Charlson Comorbidity Index because of low event numbers per subtype.

Other prevalent causes of death in AD/IMH/PAU patients were nonaortic cardiovascular causes (n = 21; 29%) and cancer (n = 8; 11%).14,15 Although none of the population referents died from an aortic cause, most also died from nonaortic cardiovascular disease (n = 40; 28%) or cancer (n = 29; 20%). Trauma and respiratory causes accounted for 5 (3%) and 11 (8%) deaths among referents, respectively.

Subsequent Aortic Events

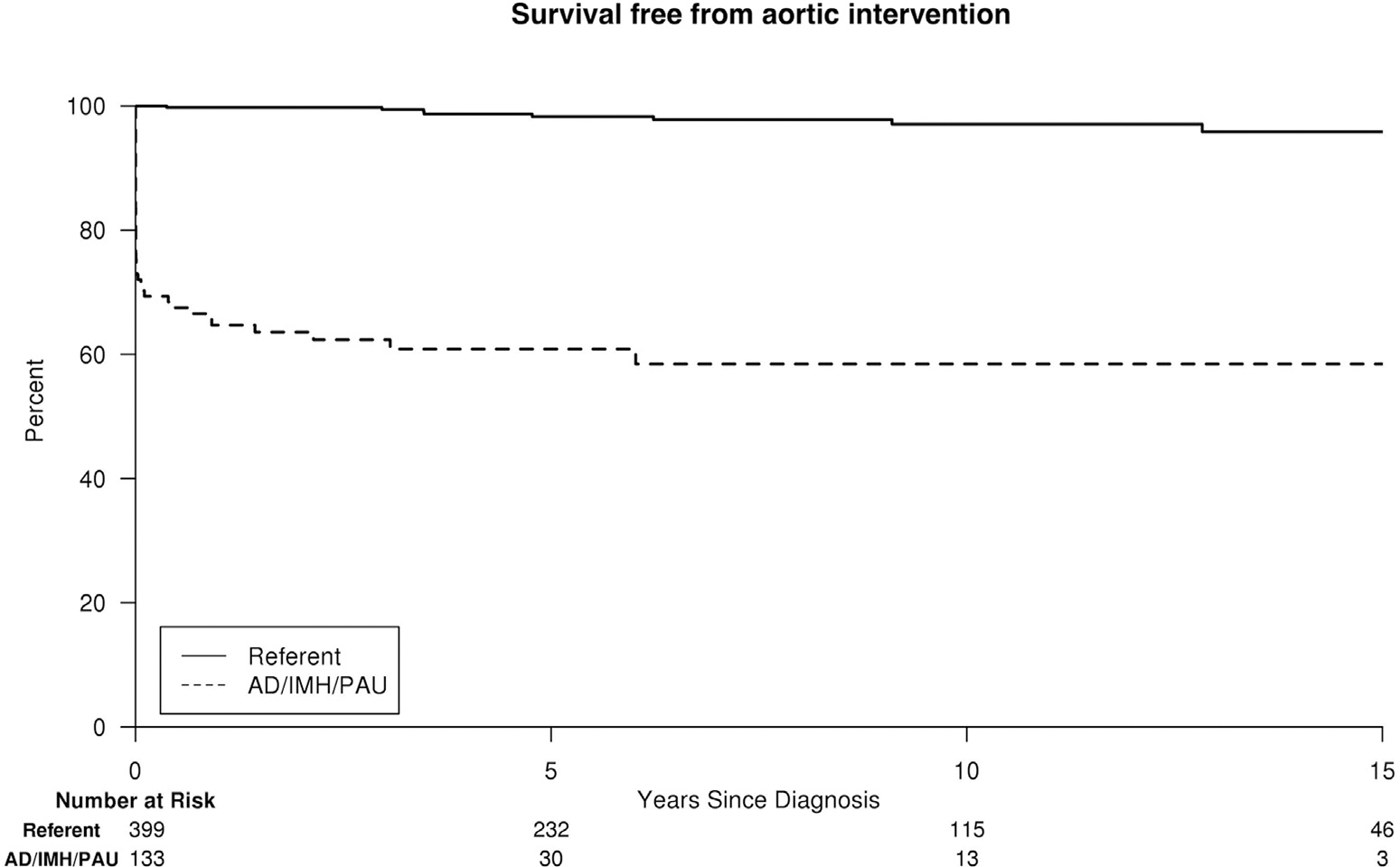

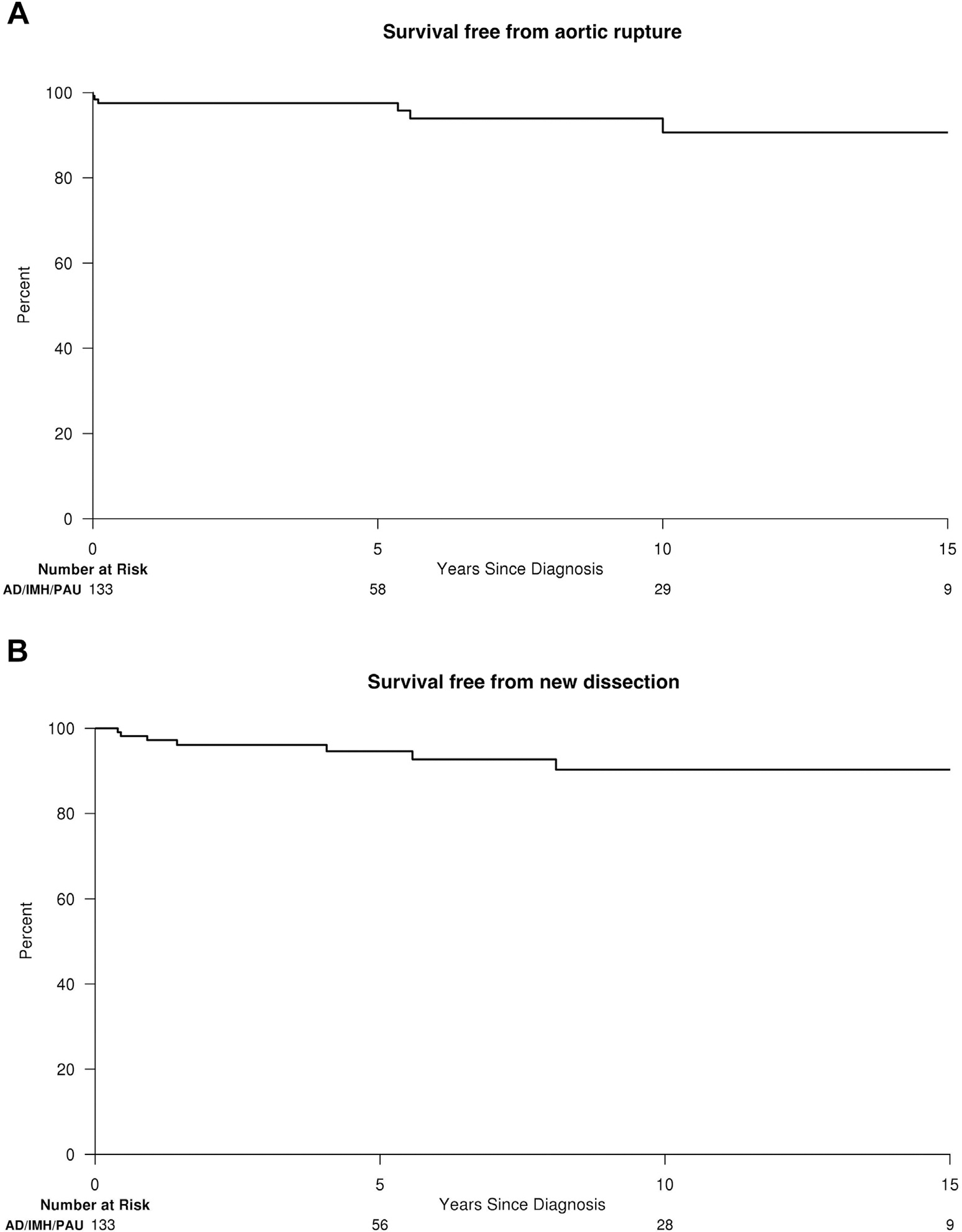

Fifty (38%) of 133 AD/IMH/PAU patients had a subsequent aortic event: 48 had at least 1 aortic intervention (including initial treatment), 7 had new dissection, and 7 had new rupture (11 had more than one of these events). Estimated freedom from any aortic event at 5, 10, and 15 years was 60%, 56%, and 56%. Among population referents, there were 8 nonruptured aneurysm repairs but no other aortic-related events, resulting in an adjusted HR for any aortic event and first aortic intervention in AD/IMH/PAU patients of 33.3 (95% CI, 15.3–72.0; P < 0.001) and 31.5 (95% CI, 14.5–68.4; P < 0.001), respectively. Survival free from aortic intervention in AD/IMH/PAU patients and referents is displayed in Figure 1. Freedom from new rupture and dissection in AD/IMH/PAU patients is displayed in Figure 2.

Fig. 1.

Survival free from aortic intervention for AD/IMH/PAU patients versus population referents of similar age and gender.

Fig. 2.

(A) Survival free from aortic rupture and (B) survival free from new AD after diagnosis of AD, IMH, or PAU.

Thirty-six (75%) of 48 aortic interventions and 2 (29%) of 7 new ruptures in AD/IMH/PAU patients occurred within 14 days of diagnosis. No new dissections occurred in the acute phase. When excluding acute interventions and events ≤14 days, AD/IMH/PAU patient remained at increased risk for any aortic event (adjusted HR, 10.8; 95% CI, 3.9–29.8; P < 0.001) and first aortic intervention (adjusted HR, 9.6; 95% CI, 3.4–26.8; P < 0.001) when compared with population referents.

Unadjusted subtype analyses showed an increased risk of any aortic event and intervention for AD and IMH, both when including the acute phase and beyond that. PAU alone was associated with aortic events only when including acute phase events but not thereafter (Table II).

New Aneurysm Formation

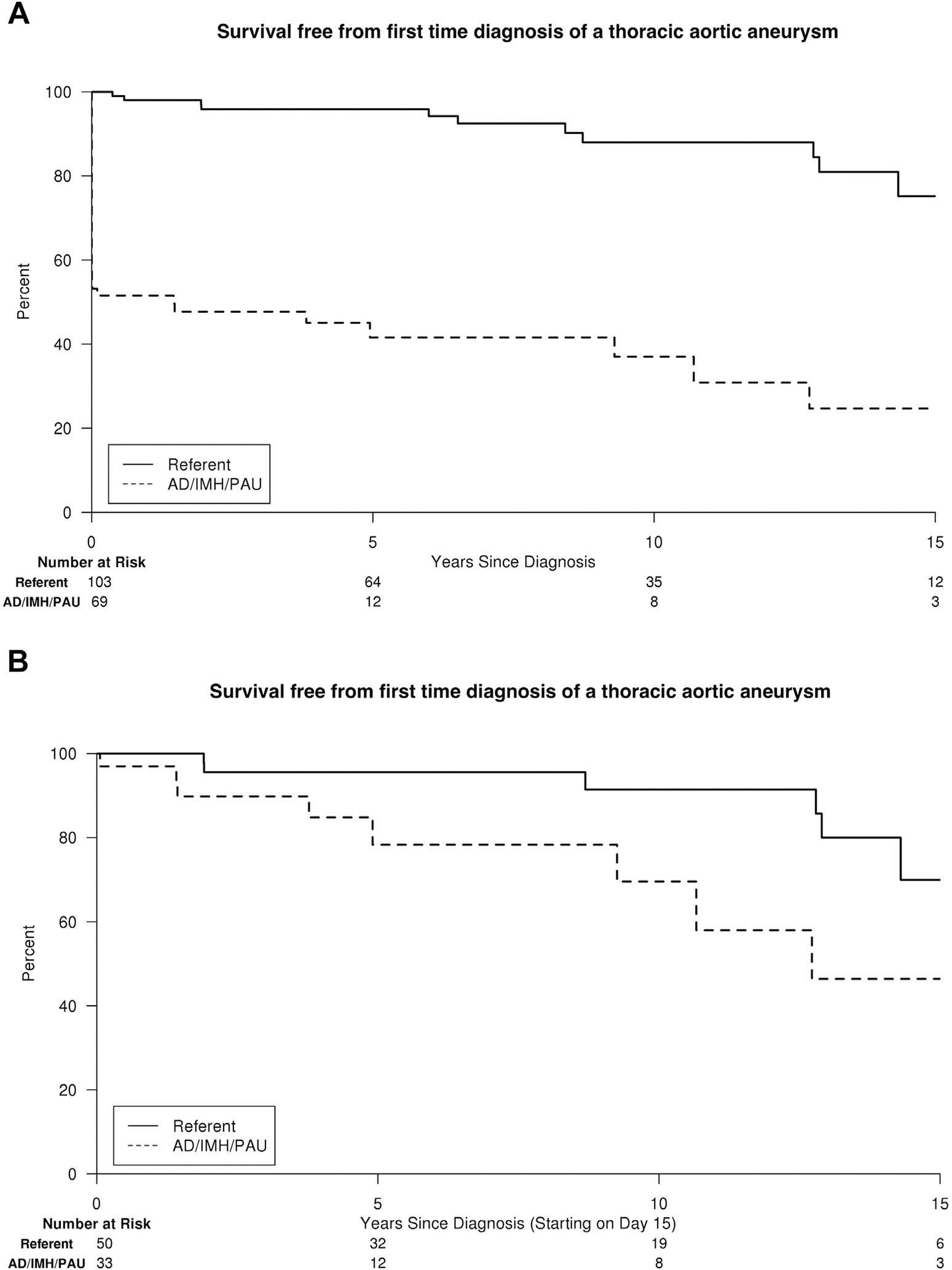

After exclusion of subjects with prior known or repaired thoracic aneurysm (Table I) and those without imaging, a total of 69 AD/IMH/PAU patients (40 AD, 11 IMH, and 18 PAU) and 103 population referents remained for the assessment of thoracic aneurysm formation. Estimated freedom of first-time diagnosis of a thoracic aneurysm at 5, 10, and 15 years was 42%, 37%, and 25% in AD/IMH/PAU patients versus 96%, 88%, and 75% in population referents (adjusted HR, 10.9; 95% CI, 5.4–21.7; P < 0.0001; Fig. 3A). Among those AD/IMH/PAU patients who did not develop a thoracic aneurysm within 14 days of AD/IMH/PAU diagnosis, freedom of thoracic aneurysm formation at 5, 10, and 15 years was 78%, 70%, and 46% (adjusted HR, 6.2; 95% CI, 1.8–21.1; P = 0.004; Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Survival free from first-time diagnosis of a thoracic aneurysm for AD/IMH/PAU patients versus population referents of similar age and gender, including all detected aneurysms from the time of (A) AD/IMH/PAU diagnosis and (B) those >14 days after diagnosis only.

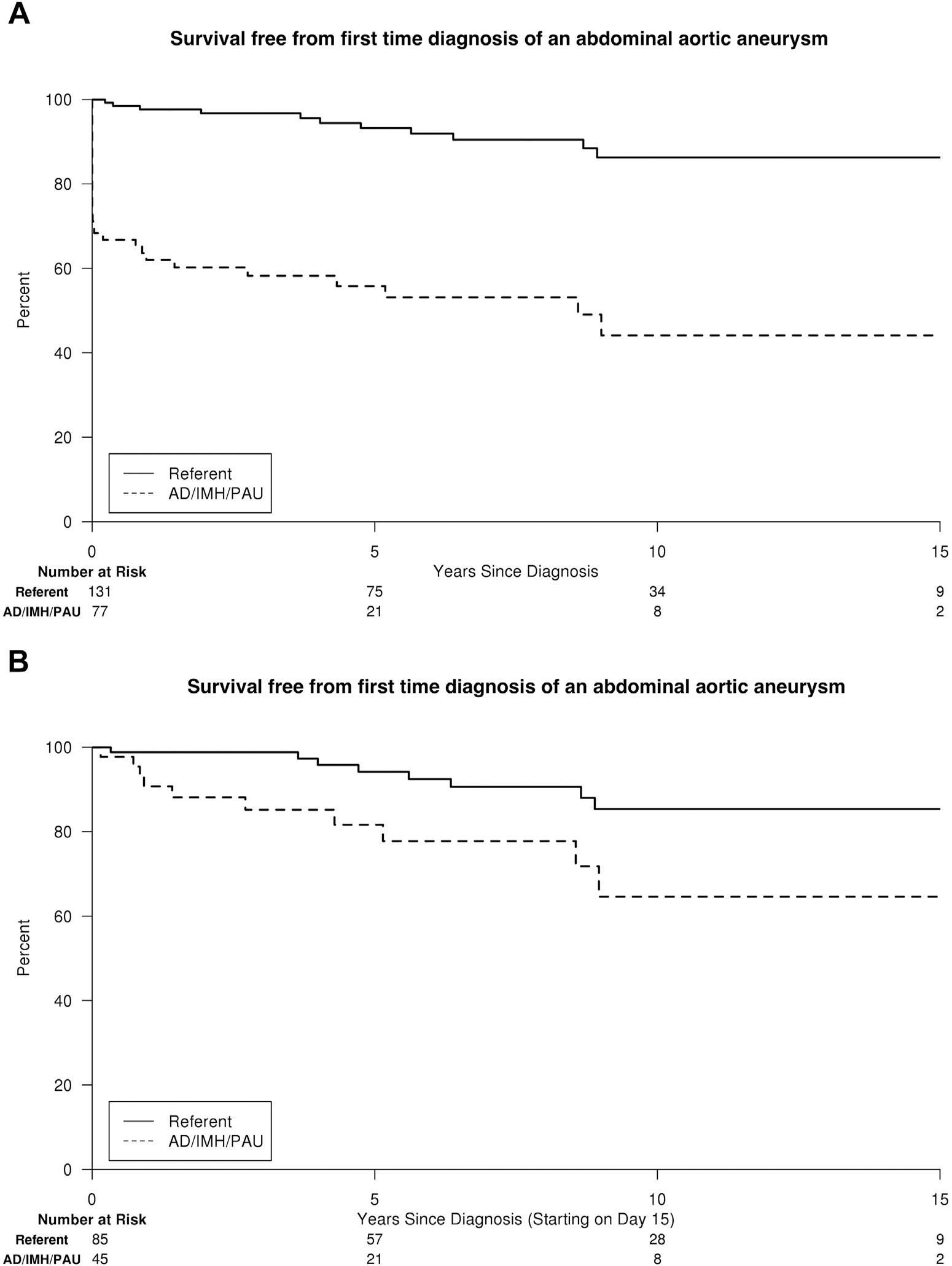

For the assessment of abdominal aneurysm formation, 77 AD/IMH/PAU patients (40 AD, 18 IMH, and 19 PAU) and 131 population referents remained. Estimated freedom of first-time diagnosis of an abdominal aneurysm at 5, 10, and 15 years was 56%, 44%, and 44% in AD/PAU/IMH patients versus 93%, 86%, and 86% in population referents (adjusted HR, 8.3; 95% CI, 4.1–16.7; P < 0.001; Fig. 4A). Among those who did not have an abdominal aneurysm within 14 days of AD/IMH/PAU diagnosis, freedom of abdominal aneurysm formation at 5, 10, and 15 years was 82%, 65%, 65% (adjusted HR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.0–7.6; P = 0.040; Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Survival free from first-time diagnosis of an abdominal aneurysm for AD/IMH/PAU patients versus population referents of similar age and gender, including all detected aneurysms (A) from the time of AD/IMH/PAU diagnosis and (B) those >14 days after diagnosis only.

DISCUSSION

This assessment of newly diagnosed AD, IMH, and PAU patients in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1995 to 2015 quantifies aortic-related outcomes from a population-based approach. Our results confirm the significant risk of aortic events known to be associated with AD/IMH/PAU diagnosis in the short term. However, our findings also highlight the relevant risk of aortic death and subsequent aortic events that remain in these patients >14 days after diagnosis. Despite follow-up and treatment, the long-term prognosis of these pathologies remains poor and never approximates population levels.

We have previously shown that AD/IMH/PAU patients remain at a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality when surviving the first 14 days after diagnosis.14 In our cohort, deaths were due to aortic causes in 32%, representing the most common cause of death. Most (52%) aortic deaths were due to rupture. Although most common within 14 days of diagnosis, aortic death remained a significant risk thereafter, accounting for 17% of late deaths, resulting in an estimated freedom from aortic death at 5, 10, and 15 years of 84%, 80%, and 77%. In previous reports, mostly including patients with AD, late deaths were due to aortic causes in 16–39%,6–8 and freedom from aortic death at 5 and 10 years (85% and 82%) was similar to our series.22 Chou et al.10 reported 32% aortic or possibly aortic-related late deaths in patients with IMH or PAU. Looking at subtypes in our cohort, the risk of aortic death was mainly driven by AD, with few late aortic deaths among IMH and PAU patients. Whereas in Chou’s series, all patients presented acutely, our cohort included newly diagnosed AD, IMH, and PAU pathologies regardless of acuity, thus possibly including more patients with less aggressive aortic disease. As we have previously shown, mortality has not improved during the past 20 years, and aortic death remains one of the most important causes of death in the long-term.14 If the prognosis of AD/IMH/PAU is to be improved, advances in the long-term treatment and follow-up of these patients are clearly necessary.

Similar to aortic death, subsequent aortic events were most prevalent within 14 days of AD/IMH/PAU diagnosis, and the most frequent subsequent aortic event was aortic intervention. This included initial surgical treatment of AD, IMH, or PAU, explaining the early drop in the Kaplan-Meier curve (Fig. 1). After excluding acute events (≤14 days), AD/IMH/PAU patients remained at significantly increased risk for any subsequent aortic event, in particular during the first 5 years after diagnosis. When compared with population referents, the risk of ever undergoing an aortic intervention among those who survived the acute phase without surgical treatment remained 10-fold higher with a total of 14% of these patients eventually undergoing intervention. Kret et al.13 reported 38% of medically treated patients with type B dissections eventually needing surgery in their series, although overall follow-up compliance of patients was limited. Chou et al.10 reported 43% of IMH and 30% of PAU patients undergoing late surgery. In our cohort, AD and IMH accounted for most of the subsequent interventions. Patients with PAU not requiring surgery within the first 14 days had the same low long-term risk of aortic intervention as the general population. However, because of low event rates among AD, IMH, and PAU separately, subtype analyses have to be interpreted very cautiously.

The assessment of aneurysm formation was clearly limited by the availability of follow-up imaging and was subdivided into thoracic and abdominal aneurysm formation for the same reason. The initial drop in survival free from first-time thoracic and abdominal aneurysm in AD/IMH/PAU patients (Fig. 2) has to be considered in the context that the data reflect the first time patients were diagnosed with an aneurysm on imaging. Because of the lack of imaging immediately before the AD/IMH/PAU event in most patients, aneurysm formation was often first diagnosed at the same time as AD, IMH, or PAU, and it remains unclear whether aneurysm or the AD/IMH/PAU pathology came first. However, when excluding those diagnosed with aneurysm formation within 14 days, the risk of developing any first-time aneurysm remained 6.2-fold and 2.8-fold higher than in population referents for the thoracic and abdominal aorta, respectively. It has to be noted, that any first thoracic and abdominal aneurysm was documented, regardless whether it involved the site of the initial AD/IMH/PAU pathology or not. These data may therefore also reflect systemic aortic disease,2 meaning that, in these patients with pathologies of the aortic media, the entire aorta is predisposed to aneurysm formation.

It has to be kept in mind that this AD/IMH/PAU incident cohort includes all newly diagnosed patients with these pathologies. As mentioned previously, it may include less severe findings than series from referral centers. This may particularly be true for PAU patients, which more often than AD and IMH, were chronic or of unknown acuity. The primary aim of this study was to define aortic-related outcomes in AD, IMH, and PAU from a broader perspective. Therefore, all identified pathologies were included, considering their common pathological disruption of the media layer of the aorta. Furthermore, those presenting with a pathology of unknown acuity may not necessarily have been asymptomatic but may have had atypical or not explicitly remembered symptoms. This comprehensive approach may explain somewhat lower rates of aortic deaths and subsequent aortic events than reported in single-center series but may more likely reflect true outcomes in the AD/IMH/PAU population overall.

When comparing AD, IMH, and PAU patients with population referents, it is obvious that the latter will be at much smaller risk for any aortic event. However, specific risks of AD/IMH/PAU patients to suffer an aortic-related complication may be difficult to grasp without a baseline in the general population. Thus, the present study stresses the implications of the aortic pathologies of AD, IMH, and PAU on the further clinical course of affected patients.

The REP provides a reliable infrastructure for population-based research in Olmsted County, capturing virtually all health cares provided to the residents of this geographically isolated region. Patients are followed across providers, and death certificates and autopsy reports are made available through the database. These are unique conditions within the United States. Although this population-based strategy strengthens our study, there are some limitations to the generalizability of the study findings. The demographical characteristic of Olmsted County reflects a predominantly white population that is slightly healthier than Minnesota state residents overall.14 However, prior studies have shown high similarity in terms of age, sex, and ethnic characteristics between Olmsted County and Minnesota/upper Midwest residents as well as similar mortality rates for Olmsted County and the United States overall.23

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study highlight the high risk of aortic death, subsequent aortic events, and aneurysm formation that is associated with AD/IMH/PAU diagnosis. Most importantly, even in patients who survive the first 14 days after diagnosis without one of these complications, a substantial aortic risk persists. This strengthens the need for further improvements in the care and treatment of these patients, potentially advocating for more rigorous follow-up in postdiagnosis aortic care and modalities of treatment for these patients. The question of how and to what extent adverse aortic outcomes can be prevented most effectively remains to be the subject of further research, but clearly, room exists for improvement.

Sources of funding:

This study was supported by the American Heart Association (16SDG27250043). It was conducted using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging under award number R01AG034676. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Data storage was performed with REDCap (UL1TR002377).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Riambau V, Bockler D, J Brunkwall, et al. Editor’s choice—management of descending thoracic aorta diseases: clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2017;53:4–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai TT, Nienaber CA, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes. Circulation 2005;112:3802–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pape LA, Awais M, Woznicki EM, et al. Presentation, diagnosis, and outcomes of acute aortic dissection: 17-year trends from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai TT, Fattori R, Trimarchi S, et al. Long-term survival in patients presenting with type B acute aortic dissection: insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. Circulation 2006;114:2226–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Umana JP, Lai DT, Mitchell RS, et al. Is medical therapy still the optimal treatment strategy for patients with acute type B aortic dissections? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;124: 896–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu HY, Chen YS, Huang SC, et al. Late outcome of patients with aortic dissection: study of a national database. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004;25:683–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsson C, Thelin S, Stahle E, et al. Thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection: increasing prevalence and improved outcomes reported in a nationwide population-based study of more than 14,000 cases from 1987 to 2002. Circulation 2006;114:211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glower DD, Speier RH, White WD, et al. Management and long-term outcome of aortic dissection. Ann Surg 1991;214:31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho KR, Stanson AW, Potter DD, et al. Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer of the descending thoracic aorta and arch. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;127:1393–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou AS, Ziganshin BA, Charilaou P, et al. Long-term behavior of aortic intramural hematomas and penetrating ulcers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;151:361–72. 373.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evangelista A, Salas A, Ribera A, et al. Long-term outcome of aortic dissection with patent false lumen: predictive role of entry tear size and location. Circulation 2012;125: 3133–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernard Y, Zimmermann H, Chocron S, et al. False lumen patency as a predictor of late outcome in aortic dissection. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:1378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kret MR, Azarbal AF, Mitchell EL, et al. Compliance with long-term surveillance recommendations following endovascular aneurysm repair or type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg 2013;58:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeMartino RR, Sen I, Huang Y, et al. A population-based assessment of the incidence of aortic dissection, intramural hematoma and penetrating ulcer, and its associated mortality from 1995 to 2015. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018;11:e004689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss S, Sen I, Huang Y, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality after aortic dissection, intramural hematoma, and penetrating aortic ulcer. J Vasc Surg 2019;70:724–731.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, et al. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester epidemiology project. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:1059–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, et al. Data resource profile: the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41: 1614–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chamberlain AM, Gersh BJ, Alonso A, et al. Decade-long trends in atrial fibrillation incidence and survival: a community study. Am J Med 2015;128:260–267.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hager A, Kaemmerer H, Rapp-Bernhardt U, et al. Diameters of the thoracic aorta throughout life as measured with helical computed tomography. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;123:1060–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaikof EL, Dalman RL, Eskandari MK, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2018;67: 2–77.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winnerkvist A, Lockowandt U, Rasmussen E, et al. A prospective study of medically treated acute type B aortic dissection. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006;32:349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, et al. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]