Abstract

Opioid misuse has dramatically increased over the last few decades resulting in many people suffering from opioid use disorder (OUD). The prevalence of opioid overdose has been driven by the development of new synthetic opioids, increased availability of prescription opioids, and more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic. Coinciding with increases in exposure to opioids, the United States has also observed increases in multiple Narcan (naloxone) administrations as life-saving measures for respiratory depression, and, thus, consequently, naloxone-precipitated withdrawal. Sleep dysregulation is a main symptom of OUD and opioid withdrawal syndrome, and therefore, should be a key facet of animal models of OUD. Here we examine the effect of precipitated and spontaneous morphine withdrawal on sleep behaviors in C57BL/6J mice. We find that morphine administration and withdrawal dysregulate sleep, but not equally across morphine exposure paradigms. Furthermore, many environmental triggers promote relapse to drug-seeking/taking behavior, and the stress of disrupted sleep may fall into that category. We find that sleep deprivation dysregulates sleep in mice that had previous opioid withdrawal experience. Our data suggest that the 3-day precipitated withdrawal paradigm has the most profound effects on opioid-induced sleep dysregulation and further validates the construct of this model for opioid dependence and OUD.

Keywords: Morphine, withdrawal, opioids, sleep, PiezoSleep

1. Introduction

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronically relapsing condition characterized by cycles of craving, binge, and withdrawal. In 2015, 37.8% of American adults were estimated to have used an opioid in the year prior, and from April 2020 to April 2021, opioid overdose deaths reached a record high of more than 100,000 [1,2]. Opioids have profound analgesic effects, but use may result in physical dependence, and discontinuation may lead to severe withdrawal symptoms known as opioid withdrawal syndrome (OWS). characterized by physical and affective symptoms, including weight loss, vomiting, aches, insomnia/sleep disturbances, diarrhea, irritability, dysphoria, anxiety, and social deficits [3]. In clinical populations OWS occurs after both spontaneous and naloxone-precipitated states of withdrawal. Naloxone, a mu-opioid receptor antagonist, is a lifesaving medication often used to precipitate withdrawal in humans experiencing respiratory failure and in animal models of OUD [4–8]. As naloxone becomes increasingly available over the counter and through Emergency Medical Services (EMS), we see increased instances of patients receiving multiple administrations of naloxone, increasing 26% from 2012–2015 [9]. Recent data indicates that in Guilford County, NC, EMS administration of naloxone increased 57.8%, and repeat administration increased 84.8% compared to pre-COVID-19 pandemic numbers [10]. These data suggest that it is important for preclinical research to investigate how precipitated withdrawal alters physiology and behavior.

With the increases in OUD and naloxone administration, it is crucial to better understand the behavioral effects of opioid withdrawal on sleep dysregulation. Sleep disruptions commonly occur during and following withdrawal from many substances, including alcohol, cannabis, and opioids [11–15]. Acute opioid administration in non-dependent adults results in sleep disturbances [16]. People with a prescription opioid dependency have been shown to differ significantly in several measures of sleep quality compared to those without dependency on prescription opioids [14]. Additionally, there is increasing evidence that sleep disruptions may be a biological pressure for relapse, especially in alcohol and opiate withdrawal [13,15,17–21]. Some of the effects of opioids on sleep have been recapitulated in preclinical models with cats, rats, and neonatal mice [22–24].

Our previous studies indicate that male and female mice experience opioid withdrawal differently, evident in their behavioral responses and neurobiology [5,25]. Far less is known about how sleep is altered during acute opioid exposure and withdrawal in mice. To our knowledge, no studies have examined the effect of opioid withdrawal on sleep behavior in female mice. One recent study highlighted how a protein that regulates circadian-dependent gene transcription altered rodent responses to fentanyl in a sex-specific manner, indicating that systems regulating circadian rhythms directly impact opioid experiences [26]. Opioid-related sleep disturbances can worsen both pain and withdrawal symptoms. Recent studies have shown that various opioids differentially affect sleep behaviors [27]. Zebadua Unzaga et al. (2021) found that increasing morphine and fentanyl dose-dependently affected sleep and wakefulness in C57BL/6 (B6J) mice [28]. Investigating the timeline and nature of these changes and how they might differ between males and females is critical to better understand the spectrum of behavioral response, and treat opioid withdrawal. In this study, we examine how three days of repeated morphine exposure and withdrawal can acutely impact sleep behaviors and how it can alter the response to future sleep disruptions in both male and female mice.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

All procedures were approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee. Male (N=52) and female (N=52) C57BL/6J (B6J) mice at least ten weeks of age were used in all experiments and were singly-housed. All animals had ad libitum access to food and water for the study duration. Following the conclusion of data collection, mice were euthanized according to IACUC protocols.

2.2. Piezo-Sleep System

Mice were housed individually in PiezoSleep 2.0 (Signal Solutions, Lexington, KY) 15.5 cm2 cages in a dedicated room separate from the general colony and behavior rooms. Mice were maintained on a 12:12 light-dark cycle (for MN vs. SN experiments, lights were on 7 AM to 7 PM, and for the MN vs. MS and MS vs. SS experiments, lights were on 10 am to 10 pm). All data are reflected as zeitgeber time (ZT). PiezoSleep is a non-invasive housing and monitoring system that uses piezoelectric pads beneath the cage floor to detect the mouse’s movement. Using SleepStats software (SleepStats v2.18, Signal Solutions, Lexington, KY), vibrational changes were processed to determine sleeping versus waking respiratory patterns, a method validated using electroencephalography and electromyogram, and visual assessment in other studies [29–31]. Data was evaluated for several parameters including the percent time spent asleep or awake for any chosen bin size and the mean bout length of each sleep event. The first two dark cycles were discarded as habituation, and baseline data consisted of at least five days of non-disrupted behavior before any manipulations.

2.3. Withdrawal paradigm

Animals were treated for three days using the paradigm described previously by Luster et al. [25]. Briefly, saline‐naloxone (SN) animals were injected with (0.9%) sterile saline (0.1 ml/10g) and 2 hr later with 1 mg/ kg naloxone (in sterile saline 0.1 ml/10g). Morphine‐naloxone (MN) animals were injected with 10 mg/kg morphine (in sterile saline 0.1 ml/10 g) and 2 hr later with 1 mg/kg naloxone (in sterile saline 0.1 ml/10 g). Morphine‐saline (MS) animals were injected with 10 mg/kg morphine (in sterile saline 0.1 ml/10 g) and 2 hr later with (0.9%) sterile saline (0.1 ml/10g). Saline‐saline (SS) animals were injected with (0.9%) sterile saline (0.1 ml/10g) and 2 hr later with (0.9%) sterile saline (0.1 ml/10g). All injections were delivered subcutaneously. Animal numbers and abbreviations for each group and experiment were as follows: male morphine naloxone (MMN; N=10) vs. male saline naloxone (MSN; N=10), female morphine naloxone (FMN; N=10) vs. female saline naloxone (FSN; N=10), male morphine naloxone (MMN; N=8) vs. male morphine saline (MMS; N=8), female morphine naloxone (FMN; N=8) vs. female saline naloxone (FSN; N=8), male morphine saline (MMS; N=8) vs. male saline saline (MSS; N=8), and female morphine saline (FMS; N=8) vs. female saline saline (FSS; N=8).

2.4. Sleep deprivation paradigm

All mice remained in the PiezoSleep chamber following the 3-day withdrawal paradigm. They were left untouched for five days and, on the 6th day, underwent an acute sleep deprivation paradigm. Mice were kept awake during the beginning of their light cycle (ZT 0–3 for the MN-SN and MS-SS experiments; ZT 1–4 for the MN-MS experiment). Sleep deprivation was accomplished using cage changes and gentle handling methods (light tapping on the cage top, ruffling food in the hopper, following the mouse in the cage with a pencil, removing nesting materials, etc.). Following sleep deprivation, mice were left alone for the remainder of the experiment.

2.5. Statistics

All data were analyzed using Graph Pad Prism (version 9.3.1). Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Comparisons were made with either regular or repeated measures 2‐way ANOVAs. All post-hoc tests were done using Bonferroni’s correction. ANOVAs are reported as (F(DFn,DFd)= F-value, p= P-value). Figure 2 depicts three different statistical methods: (1) 2-way ANOVA with no correction made for violation of sphericity assumption, (2) 2-way ANOVA with correction made across ZT hours 0–23, (3) two separate 2-way ANOVAs with correction made (split by light cycle ZT hours 0–11 and 12–23). Method 3 (Fig. 2 G & I) was chosen for all subsequent figures for two reasons. First, it is more conservative than method 1 which does not correct for the violation of sphericity. Second, it treats the light cycles separately which better elucidates the differences within light cycles and improves our predictive validity. It has been established that traditional statistics do not always properly account for biological rhythms [32]. Given the expectation that there will be significant differences between light and dark cycles when assessing sleep, we conduct ANOVAs on the light cycles separately (method 3) to avoid confounding biologically meaningful differences caused by our manipulations [33]. Through assessing these various methods, we believe we have achieved the greatest possible validity when making statistical conclusions.

Figure 2. Sex differences in baseline sleep behaviors of C57 mice using three different methods of statistical analysis.

Average of all baseline days shown as percent time spent sleeping of each hour in a 24-hour period, shown as Zeitgeber Time (ZT). ZT0 is the start of the light cycle and ZT12 is the start of the dark cycle. All 24-hour graphs show the same data but (A,C) do not have the Geisser-Greenhouse Correction, (D,F) use the GG Correction, and (G,I) utilize the GG Correction but hours 0–11 and 12–23 were analyzed separately. (B,E,H) Percent time spent sleeping in a 12-hour period of all baseline days (light or dark) and across all 24-hours of all baseline days, no GG corrections were used because there were only 2 repeated measures.

3. Results

3.1. Modeling morphine withdrawal in PiezoSleep chambers.

We used a three-day withdrawal paradigm previously validated in our lab to assess the effect of morphine withdrawal on sleep behaviors in C57B6/J mice [5,25]. This paradigm has been shown to result in sensitization of withdrawal symptoms over the three days of administration [25]. We have also shown various behavioral effects six weeks into forced abstinence [5]. In male Sprague-Dawley rats, this paradigm has been shown to alter noradrenergic transmission in the ventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (vBNST) [34]. Here we evaluate male and female C57B6/J mice under various conditions, including spontaneous withdrawal, precipitated withdrawal, saline control, and naloxone control (Fig. 1). Given our previously reported physiological and behavioral sex differences following precipitated withdrawal[5,25], we do not statistically compare the males and females but consider qualitative comparisons. Each experiment consisted of 7 days of habituation and baseline recording, three days of withdrawal, five days of recovery recordings, a 4-hour sleep deprivation study, and additional 2 recovery days (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Precipitated-withdrawal paradigm in PiezoSleep chambers.

Experimental timeline including habituation, baseline, morphine exposure and withdrawal, observation, and sleep deprivation. Table detailing the eight different treatment groups (four per sex).

3.2. Significant sex differences in sleep baselines.

We examined percent time sleeping on baseline days from all animals in the study, females (N=52) and males (N=52), across each zeitgeber hour. Baseline sleep was calculated by averaging each zeitgeber hour across the 3–5 days preceding withdrawal day one and calculating the percent of the time the mouse spent asleep each hour. We completed the analyses in three different ways to determine the most conservative and reasonable method to apply statistical measurements (see Methods for discussion): (method 1) no sphericity correction applied, (method 2) Geisser-Greenhouse correction applied, or (method 3) the GG correction applied to each light cycle independently. This correction for sphericity affects only the post-hoc analysis with the results as follows:

We found a main effect of sex (Figure 2A, No Geisser-Greenhouse Correction, F(1,102) =13.69, p=0.0004), and a significant interaction of sex vs. time (Fig. 2A, F(1,102)=3.839, p<0.0001). Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons showed significant differences in hour 0 (p<0.0001), hour 1 (p<0.0001), hour 3 (p=0.0107), hour 4 (p=0.0480), and hour 6 (p=0.0037). There was a main effect of sex on sleep bout lengths (shown in seconds) as well as a significant interaction (Fig. 2C, No Geisser-Greenhouse Correction, main effect: F(1, 102) = 8.220, p=0.0050; time × sex: F(5, 510) = 5.248, p=0.0001). Bonferroni’s comparison with no correction showed significant differences during hours 0–3 (p<0.0001) and hours 8–11 (p=0.0238).

We found a main effect of sex (Figure 2D, Geisser-Greenhouse Correction Applied, F(1,102) =13.69, p=0.0004), and a significant interaction of sex vs. time (Fig. 2C, F(1,102)=3.839, p<0.0001). Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons showed significant differences in hour 0 (p=0.0085), hour 1 (p=0.0006), hour 3 (p=0.0196), hour 4 (NS, p=0.0797), and hour 6 (p=0.0063). There was a main effect of sex on sleep bout lengths (shown in seconds) as well as a significant interaction (Fig. 2F, Geisser-Greenhouse Correction Applied, main effect: F(1, 102) = 8.220, p=0.0050; time × sex: F(5, 510) = 5.248, p=0.0001). Bonferroni’s comparison with GG correction showed significant differences during hours 0–3 (p=0.0063) and hours 8–11 (p=0.0016).

We found a main effect of sex in the light cycle (Figure 2G, Geisser-Greenhouse Correction Applied to Light Cycles Separately, F(1,102) =30.62, p<0.0001), and a significant interaction of sex vs. time (Fig. 2G, F(11,1122)=2.643, p=0.0024). Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons showed significant differences in hour 0 (p=0.0043), hour 1 (p=0.0003), hour 3 (p=0.0098), hour 4 (p=0.0398), and hour 6 (p=0.0031). We found no main effect of sex in the dark cycle (Figure 2G, Geisser-Greenhouse Correction Applied to Light Cycles Separately, F(1,99) =0.0004892, p=0.9824), and no significant interaction of sex vs. time (Fig. 2G, F(11,1089)=1.576, p=0.1002). Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons showed no significant differences in the dark cycle. There was a main effect of sex on sleep bout length in the light cycle (Figure 2I, Geisser-Greenhouse Correction Applied to Light Cycles Separately, F(1, 102) = 16.25, p=0.0001), but no significant interaction of sex vs. time in the light cycle (Fig. 2I, F(2, 204) = 1.168, p=0.3130). Bonferroni’s comparison with GG correction showed significant differences during hours 0–3 (p=0.0032) and hours 8–11 (p=0.0008). There were no main effects or statistically significant interactions in the dark cycle, though the interaction was p=0.0500 (Fig. 2I, main effect of sex: F(1, 102) = 0.01245, p=0.9114, sex × time: F(2, 204) = 3.039, p=0.0500).

There were no significant differences during the dark cycle, but males slept significantly more than females during the light cycle (Figure 2B, E, H: F(1,102)=14.57, p=0.0002) and the entire day (t-test, t=3.817, df=102, p=0.0002). For the light cycle analyses, no corrections were run due to the number of repeated measures being too low to warrant a correction. We confirmed that there were no baseline differences in sleep percentage between treatment groups in each experiment before starting any injections (data not shown: FMN vs. FSN (p=0.9275), FMN vs. FMS (p=0.5275), FMN vs. FSS (p=0.8731), MMN vs. MSN (p=0.3955), MMN vs. MMS (p=0.1607), and MMS vs. MSS (p=0.6985)).

These data demonstrate that with a sufficiently high N, that there is no meaningful difference in the data between each method for statistical analysis. We did lose statistical power, however, when using method 2 where the light cycles were not split when the GG correction was used. This can be observed by the GG epsilon value (ε) being lower in method 2 vs. method 3, and the loss of some statistical significance in post-hoc analysis (e.g., ZT hour 4 in 2 vs. 3, Fig 2D, 2G). As the GG correction is the more ideal correction to account for inflated F-statistics due to lack of sphericity when the epsilon (ε) value is lower than 0.75, we wanted to maintain this analysis while improving the ε values as much as possible. Therefore, we chose to use method 3 for the remainder of analysis in this paper [33].

3.3. Effect of morphine withdrawal on percent sleep in male mice.

On withdrawal day 1, there was a main effect of the treatment group for the MMN vs. MSN experiment in both ZT 0–11 and ZT 12–23 (Fig 3A; Light: F(1, 18) = 28.90, p<0.0001; Dark: F(1, 18) = 48.27, p<0.0001) but not for the other comparisons (3C: MMN vs. MMS and 3E: MMS vs. MSS). There was also a main effect of light cycle when averaged across the 12 hours for the MMN vs. MSN experiment (Fig 3B; Light: F(1, 18) = 28.90, p<0.0001; Dark: F(1, 18) = 48.27, p<0.0001) but not for the other experiments (3D and 3F). There was a main effect of time across all groups, as is expected with diurnal cycles like sleep patterns (Fig 3; (A) MMN vs MSN Light: F(6.286, 113.1) = 23.79, p<0.0001; Dark: F(7.028, 126.5) = 6.965, p<0.0001; (C) MMN vs MMS Light: F(4.413, 61.78) = 46.18, p<0.0001; Dark: F(5.233, 73.27) = 6.683, p<0.0001; (E) MMS vs MSS Light F(3.591, 50.27) = 3.500, p<0.0001; Dark: F(4.951, 69.32) = 4.813, p<0.0001). There was a significant interaction between the treatment group and ZT hour in the MMN vs. MSN experiment (Fig 3A light hours; F(11, 198) = 7.459, p<0.0001). Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test resulted in the following significant differences: hour 1 (p=0.0068), hour 2 (p<0.0001), and hour 4(p<0.0001). Also, in the precipitated withdrawal and naloxone control experiment, post-hoc testing of the light cycle comparisons showed significant differences across 12-hour averages (light vs. dark) between the two treatment groups: MSN mice slept more than MMN mice in the light cycle (3B, p<0.0001) and significantly less than MMN mice in the dark cycle (3B, p=0.0002).

Figure 3. Sleep behavior of male mice during morphine exposure and withdrawal.

Graphs depict either 24-hour sleep trace with percent sleep per hour, percent sleep per light cycle, or daily percent sleep. Each row is a different day (withdrawal days 1–3 and then recovery day 1). Black arrows indicate morphine or saline injections (injection #1) and red arrows indicate saline or naloxone injections (injection #2). (A-F) withdrawal day 1 (G-L) withdrawal day (M-R) withdrawal day 3 (S-X) recovery day Each point or bar represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Withdrawal day 2 mostly followed the same trends as day 1. All experiments exhibited a main effect of time (Fig 3; (G) MMN vs MSN Light: F(5.771, 103.9) = 20.04, p<0.0001; Dark: F(5.396, 97.12) = 9.179, p<0.0001; (I) MMN vs MMS Light: F(4.413, 61.78) = 46.18, p<0.0001; Dark: F(5.233, 73.27) = 6.683, p<0.0001; (K) MMS vs MSS Light: F(3.085, 43.18) = 12.50, p<0.0001; Dark: F(4.882, 68.35) = 4.071, p=0.0029). The MMN vs. MSN experiment had a significant interaction of ZT hour and treatment group (Fig. 3G Light: F(11, 198) = 3.957, p<0.0001), and Bonferroni’s post-hoc showed significant differences between precipitated withdrawal and naloxone control at hour 1 (p=0.0045), hour 2 (p=0.0148), and hour 15 (p=0.0082). On WD2, there was also a significant interaction of ZT hour and treatment group for the spontaneous withdrawal vs. saline control experiment (3K: F(11, 154) = 2.537, p=0.0057) and Bonferroni’s post-hoc showed significant differences between MMS and MSS at hour 1 (p=0.052). In the MMN vs. MMS experiment, there were no interactions or significant effect of treatment, but hour 13 was trending towards significance (Fig. 3I, p=0.0841). While assessing the role of treatment groups on sleep during different light cycles, the MMN vs. MSN experiment had a main effect of light cycle (Fig 3H: F(1, 18) = 58.99, p<0.0001) and a significant interaction of light cycle and treatment group (Fig 3H: F(1, 18) = 50.66, p<0.0001). Again, post-hoc analysis showed that MMN mice slept significantly less in the light (Fig 3H: p<0.0001) and significantly more in the dark (Fig 3H: p<0.0001) than the MSN mice run at the same time. There was a main effect of cycle in the MMS vs. MSS groups (Fig 3L: F(1, 14) = 12.26, p=0.0035) and a trend towards a significant interaction (Fig 3L: F(1, 14) = 3.218, p=0.0945), but no post hoc differences.

On withdrawal day 3, all experiments exhibited a main effect of ZT hour (Fig 3; (M) MMN vs MSN Light: F(6.661, 119.9) = 20.49, p<0.0001; Dark: F(5.641, 101.5) = 7.159, p<0.0001; (O) MMN vs MMS Light: F(5.304, 74.26) = 30.85, p<0.0001; Dark: F(5.924, 82.94) = 6.239, p<0.0001; (Q) MMS vs MSS Light: F(3.310, 46.34) = 15.79, p<0.0001; Dark: F(5.695, 79.73) = 3.690, p=0.0032) as well as a significant interaction of treatment condition vs. time in at least one of the 12-hour sets (Fig 3; (M) MMN vs MSN Light: F(11, 198) = 4.684, p<0.0001; (O) MMN vs MMS Light: F(11, 154) = 3.548, p=0.0002; Dark: F(11, 154) = 2.924, p=0.0016; (Q) MMS vs MSS Light: F(11, 154) = 3.824, p<0.0001). Hour 1 (p<0.0001and hour 15 (p=0.0378) in the MMN vs MSN experiment were significantly different when examined with post-hoc testing and hour 2 was trending (p=0.073), (Fig. 3M). When we examined MMN and MMS conditions (Fig. 3O), hours 21 (p=0.0079) and 22 (p=0.0111) were significantly different. The only hour with differences between MMS and MSS was hour 1 (Fig. 3Q; p=0.0012). When looking at the experiments based on 12 hour light cycles, MMN vs MSN showed a main effect of light cycle (Fig 3N; F(1, 18) = 232.5, p<0.0001) and a significant interaction of light cycle and treatment (Fig 3N; F(1, 18) = 15.26, p<0.0001) where post-hoc testing showed the MSN mice slept more in the light (p=0.0017) and less in the dark (p=0.03) when compared to MMN mice. In the MMS vs MSS experiment, the spontaneous withdrawal group slept significantly more than the saline control in the dark (Fig. 3R, p=0.0213) and had a main effect of light cycle (Fig 3R; F(1, 14) = 56.59, p<0.0001) and a significant interaction of light cycle and treatment (Fig 3R; F(1, 14) = 6.091, p<0.0001).

Following three days of injections, the mice were left to recover on day 4 (acute withdrawal [25]) without experimental disturbance, and sleep behavior was continuously monitored. There were main effects of ZT hour (Fig 3; (S) MMN vs MSN Light: F(5.459, 98.27) = 4.984, p=0.003; Dark: F(5.376, 96.77) = 8.699, p<0.0001; (U) MMN vs MMS Light: F(5.552, 77.73) = 2.803, p=0.0185; Dark: F(4.820, 67.48) = 14.08, p<0.0001; (W) MMS vs MSS Light: F(4.005, 56.08) = 7.893, p<0.0001; Dark: F(4.599, 64.39) = 5.565, p=0.0004) and, interestingly, significant interactions of treatment condition and ZT hour Fig 3; (S) MMN vs MSN Light: F(11, 198) = 2.539, p=0.051; Dark: F(11, 198) = 2.028, p=0.0275; (U) MMN vs MMS Dark: F(11, 154) = 1.876, p=0.0464; (W) MMS vs MSS Light: F(11, 154) = 2.121, p=0.0218). The difference between MMN and MSN was significant at hour 2 (Fig. 3S, p=0.0353). The MMN mice slept less in the light (Fig. 3T, p=0.0318) and more in the dark cycle (Fig. 3T, p=0.0054). MMS mice slept less than MSS mice across the entire light cycle (Fig. 3X, p=0.0023), and slightly more than the MSS in the dark (Fig. 3X, NS p=0.0854). All groups of mice slept approximately equal amounts out of the entire day, and there were no significant differences (data not shown).

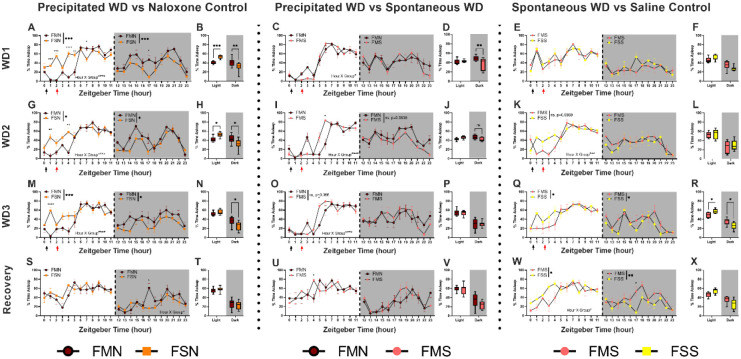

3.4. Effect of morphine withdrawal on percent sleep in female mice.

Similar to the male dataset, on withdrawal day 1 the FMN vs. FSN group showed a significant main effect of group (Fig 4A; Light: F(1, 18) = 24.49, p<0.0001; Dark: F(1, 18) = 16.01, p=0.0008) but not for the other comparisons (4C: FMN vs. FMS and 4E: FMS vs. FSS). In the first 12 hours, there was a significant interaction of treatment condition and ZT hour for FMN vs. FSN and FMN vs. FSN (Fig 4; (A) MMN vs MSN Light: F(11, 198) = 11.65, p<0.0001; (C) MMN vs MMS Light: F(11, 154) = 1.862, p=0.0484). All experiments exhibited a main effect of time except for the dark portion of MMS vs. MSS (Fig 4; (A) FMN vs FSN Light: F(6.048, 108.9) = 27.74, p<0.0001; Dark: F(6.642, 119.6) = 5.337, p<0.0001; (C) FMN vs FMS Light: F(4.066, 56.92) = 51.44, p<0.0001; Dark: F(5.282, 73.95) = 4.319, p<0.0001; (E) FMS vs FSS Light F(4.936, 69.11) = 6.115, p<0.0001). Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test resulted in the following significant differences between FMN and FSN: hour 1 (p=0.0003), hour 2 (p<0.0001), hour 4 (p<0.0001), hour 5 (p=0.0034), hour 7 (p=0.0456), and hour 17 (p=0.0325). When averaging across light cycle, all three experiments showed significant interaction of time and group (Fig 4; (B) MMN vs MSN: F(1, 35) = 26.54, p<0.0001; (D) MMN vs MMS: F(1, 14) = 6.013, p=0.0279; (F) MMS vs MSS: F(1, 14) = 7.452, p=0.0163), but none showed a main effect of group. Post-hoc tests showed that FMN mice sleep less than FSN mice in the light (4B: p=0.0004) and more in the dark (4B: p=0.0069). FMN mice slept more than FMS mice in the dark cycle (4D: p=0.0087). There were no significant differences between FMS and FSS, but differences trended towards significance (4F: light (p=0.0759) and dark (p=0.095)).

Figure 4. Sleep behavior of female mice during morphine exposure and withdrawal.

Graphs depict mean sleep bout in seconds per 4-hour bin of time. (A-C) withdrawal day 1 (D-F) withdrawal day (G-I) withdrawal day (J-L) recovery day Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Grey shading represents dark cycle hours.

All experiments exhibited a main effect of time on withdrawal day 2 (Fig 4; (G) FMN vs FSN Light: F(5.610, 101.0) = 18.25, p<0.0001; Dark: F(5.610, 101.0) = 18.25, p<0.0001; (I) FMN vs FMS Light: F(4.221, 59.09) = 46.56, p<0.0001; Dark: F(5.614, 78.60) = 4.105, p=0.0016; (K) FMS vs FSS Light F(4.353, 60.94) = 11.99, p<0.0001) Dark: F(6.506, 91.09) = 3.232, p=0.0051). Unlike the male sleep results, all three experiments had significant time and treatment group interactions on day 2 during the light. The FMN vs. FSN experiment had a significant interaction of treatment group and time (Fig. 4G: Light F(11, 198) = 4.047, p<0.0001) and Bonferroni’s post-hoc showed significant differences between precipitated withdrawal and naloxone control at hour 1 (p=0.0014) and hour 4 (p=0.0046). The precipitated versus spontaneous withdrawal experiment had similar differences in interactions (Fig. 4I: F(11, 154) = 7.197, p<0.0001) with trends towards differences at hour 3 (p=0.08) and hour 23 (p=0935) and a significant difference at hour 6 (p=0.036). There was also a significant interaction between ZT hour and the treatment group for the spontaneous withdrawal vs. saline control experiment (Fig. 4K: F(11, 154) = 3.088, p=0.0009). While assessing the role of treatment groups on sleep during different light cycles, the FMN vs. FSN experiment had a main effect of time (Fig. 4H: F(1, 18) = 15.00, p=0.0011) and a significant interaction of light cycle and treatment group (Fig 4H: F(1, 18) = 14.79, p=0.0012). Post-hoc analysis showed that FMN mice slept significantly less in the light (Fig 4H: p=0.0128) and more in the dark (p=0.0062) than the FSN mice. The FMN vs. FMS experiment had a significant interaction of light cycle and treatment group (Fig 4J: F(1, 13) = 0.1219, p=0.0012).

As with the males on withdrawal day 3, all experiments exhibited a main effect of ZT hour (Fig 4; (M) FMN vs FSN Light: F(6.284, 113.1) = 16.46, p<0.0001; Dark: F(5.923, 106.6) = 3.214, p=0.0063; (O) FMN vs FMS Light: F(5.097, 71.36) = 42.18, p<0.0001; Dark: F(5.886, 82.41) = 4.579, p=0.0005; (Q) FMS vs FSS Light F(4.060, 56.85) = 8.876, p=0.0001) Dark: F(6.042, 84.58) = 5.700, p=0.0001). The FMN vs. FSN and FMN vs. FMS experiments had significant interactions of treatment condition and ZT hour in the light hours (Fig 4; (M) FMN vs FSN F(23,414) =3.186, p<0.0001; (O) FMN vs FMS F(23,322) =2.206, p=0.0014). Hour 1 in the FMN vs FSN experiment was significantly different with post-hoc testing (Fig 4M; p<0.0001). When we examined FMN and FMS conditions (Fig. 4O) only hour 5 was significant (p=0.0151). Between FMS and FSS, the FMS animals slept less (p=0.0298) in the light and more in the dark (p=0.0131) than the FSS animals (Fig. 4Q). FMN vs FSN showed a main effect of light cycle (Fig 4N; F(1, 35) = 90.94, p<0.0001) and a significant interaction of light cycle and treatment (Fig 4N; F(2,35) =6.260, p<0.0001) where post-hoc testing showed the FMN mice slept more in the dark (p=0.0109) compared to FSN mice.

On day 4, there were main effects on ZT hour for all groups (Fig 4; (S) FMN vs FSN Light: F(6.026, 108.5) = 4.256, p=0.0007; Dark: F(6.026, 108.5) = 4.256, p<0.0001; (U) FMN vs FMS Light: F(6.059, 84.83) = 3.553, p=0.0034; Dark: F(5.062, 70.86) = 7.560, p<0.0001; (W) FMS vs FSS Light F(5.435, 76.09) = 7.754, p=0.0001) Dark: F(5.768, 80.75) = 2.723, p=0.0198). There were significant interactions of treatment condition and ZT hour in dark of the FMN vs. FSN experiment When comparing by cycle, all groups had a main effect of light cycle and there was a significant interaction of cycle and treatment group in the FMS vs. FSS experiment (Fig 4; (T) FMN vs FSN F(1, 18) = 152.1, p<0.0001; (V) FMN vs FMS F(1, 14) = 43.87, p<0.0001; (X) FMS vs FSS cycle: F(1, 14) = 33.95, p<0.0001 and interaction: F(1, 14) = 6.009, p=0.028). Post-hoc analysis showed FMN mice slept more than FSN mice at hour 17 (Fig. 4S, p=0.0247), FMS mice slept more than FMN mice at hour 4 (Fig. 4U, p=0.0384) and FMS mice slept more than FSS mice at hour 17(p= 0.0246; Fig. 4W).

3.5. Male sleep bout length during morphine withdrawal.

On withdrawal day 1, all three experiments showed a main effect of time in both the light and some in the dark cycle (Fig. 5; (A) MMN vs MSN Light: F(1.649, 29.69) = 18.32, p<0.0001; (B) MMN vs MMS Light: F(1.990, 27.86) = 39.57, p<0.0001; Dark: F(1.962, 27.47) = 7.218, p=0.0032; (C) MMS vs MSS Light: F(1.964, 27.50) = 21.11, p<0.0001; Dark: F(1.463, 20.48) = 7.746, p=0.0059) as well as a significant interaction of treatment condition vs. time in at least one of the 12-hour sets (Fig. 5; (A) MMN vs MSN Light: F(2, 36) = 4.580, p=0.0169; (B) MMN vs MMS Light: F(2, 28) = 4.017, p=0.0292; (C) MMS vs MSS Light: F(2, 28) = 7.869, p=0.0019). There was a main effect of treatment group in two comparisons (Fig. 5; (A) MMN vs MSN Light: F(1, 18) = 8.003, p=0.0111; (C) MMS vs MSS Dark: F(1, 14) = 9.186, p=0.09). Post hoc analysis only revealed a difference in the 4–7 hour time bin of MMN vs MSN (p=0.0158).

Figure 5. Sleep bout lengths in male mice.

Graphs depict mean sleep bout in seconds per 4-hour bin of time. (A-C) withdrawal day 1 (D-F) withdrawal day (G-I) withdrawal day (J-L) recovery day Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Grey shading represents dark cycle hours.

On withdrawal day 2, all three experiments showed the same pattern of main effect of time (Fig. 5; (D) MMN vs MSN Light: F(1.998, 35.96) = 43.21, p<0.0001; (E) MMN vs MMS Light: F(1.958, 27.41) = 53.27, p<0.0001; Dark: F(1.456, 20.38) = 19.05, p<0.0001; (F) MMS vs MSS Light: F(1.826, 25.56) = 33.26, p<0.0001; Dark: F(1.823, 25.52) = 5.351, p=0.0133) as well as a significant interaction of treatment condition vs. time in at least one of the 12-hour sets (Fig. 5; (D) MMN vs MSN Light: F(2, 36) = 6.998, p=0.0027; Dark: F(2, 36) = 0.4666, p= 0.6309; (E) MMN vs MMS Dark F(2, 28) = 3.753, p=0.036; (F) MMS vs MSS Light: F(2, 28) = 5.910, p=0.0072; Dark: F(2, 28) = 5.874, p=0.0074). There was a main effect of treatment group in two comparisons (Fig. 5; (A) MMN vs MSN Dark: F(1, 18) = 4.781, p=0.0422; (C) MMS vs MSS Dark: F(1, 14) = 5.392, p=0.0358). Post hoc analysis revealed a difference in the 0–3 hour time bin of MMN vs MSN (Fig. 5D: p=0.0032) and hours 0–3 and 16–19 of MMS vs MSS (Fig. 5F: bin 0–3 p=0.0007, bin 16–19 p=0.0119).

Withdrawal day 3 for the males had the same significant effect of time (Fig. 5; (G) MMN vs MSN Light: F(1.739, 31.30) = 24.75, p<0.0001; (H) MMN vs MMS Light: F(1.618, 22.65) = 41.31, p<0.0001; Dark: F(1.747, 24.46) = 5.688, p=0.0118; (I) MMS vs MSS Light: F(1.916, 26.83) = 42.25, p<0.0001; Dark: F(1.519, 21.27) = 4.056, p=0.0419) but there were fewer significant interaction of treatment condition vs. time (Fig. 5; (H) MMN vs MMS Light F(2, 28) = 4.993, p=0.014; Dark F(2, 28) = 3.604, p=0.0405; (I) MMS vs MSS Light: F(2, 28) = 11.76, p=0.0002). There was a main effect of treatment group in all three comparisons (Fig. 5; (G) MMN vs MSN Dark: F(1, 18) = 5.826, p=0.0267; (H) MMN vs MMS Light: F(1, 14) = 5.859, p=0.0297; (I) MMS vs MSS Dark: F(1, 14) = 7.970, p=0.0315). Post hoc analysis revealed a difference in the 0–3 hour time bin of MMN vs MSN (Fig. 5G: p=0.0051), hours 20–23 of MMN vs MMS (Fig. 5H: p=0.0388), and hours 8–11 and 12–15 of MMS vs MSS (Fig. 5I: bin 8–11 p=0.0491, bin 12–15 p=0.0435). There were no significant interactions for any group. There was a main effect of treatment in the light cycle of the MMN vs MMS comparison (p

Finally on the recovery day, only two conditions had main effects of time (Fig. 5; (J) MMN vs MSN Light: F(1.709, 30.76) = 18.48, p<0.0001; Dark: F(1.814, 32.65) = 7.271, p=0.0032; (K) MMN vs MMS Light: F(1.957, 27.40) = 4.366, p=0.0233; Dark: F(1.980, 27.72) = 22.13, p<0.0001) and the MMS vs. MSS experiment did not show differences based on time. MMN vs MMS showed a main effect of treatment in the light (Fig. 5K: p=<0.0001).

3.6. Female sleep bout length during morphine withdrawal.

On withdrawal day 1, all three experiments showed a main effect of time in only the light cycle (Fig. 6; (A) FMN vs FSN Light: F(1.745, 31.41) = 25.62, p<0.0001; (B) FMN vs FMS Light: F(1.591, 22.28) = 46.46, p<0.0001; (C) FMS vs FSS Light: F(1.867, 26.14) = 56.64, p<0.0001). Several of the experiments had time by treatment group interactions (Fig. 6: (A) FMN vs FSN Light: F(2, 36) = 7.896, p=0.0014; (C) FMS vs FSS Light: F(2, 36) = 0.5658, p=0.0016). There were no main effects of treatment group, and only two post-hoc tests were significant (Fig. 6; (A) hours 0–3: p=0.0037; (B) hours 12–15: p=0.0354).

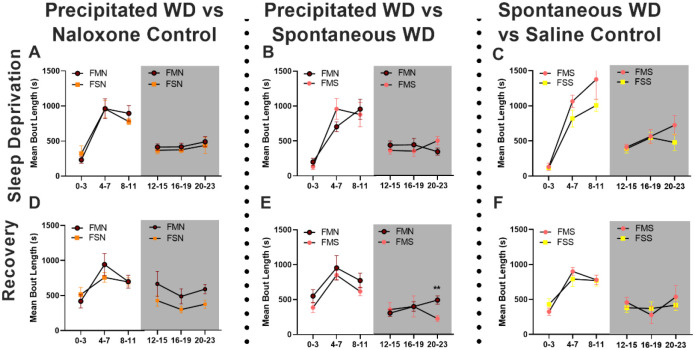

Figure 6. Sleep bout lengths in female mice.

Graphs depict mean sleep bout in seconds per 4-hour bin of time. (A-C) withdrawal day 1 (D-F) withdrawal day (G-I) withdrawal day (J-L) recovery day Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Grey shading represents dark cycle hours.

On withdrawal day 2, all three experiments still showed a main effect of time only the light cycle (Fig. 6; (D) FMN vs FSN Light: F(1.788, 32.19) = 33.74, p<0.0001; (E) FMN vs FMS Light: F(1.067, 14.94) = 40.71, p<0.0001; (F) FMS vs FSS Light: F(1.957, 27.40) = 53.74, p<0.0001). Several of the experiments had time by treatment group interactions (Fig. 6: (D) FMN vs FSN Light: F(2, 36) = 3.650, p=0.036; (F) FMS vs FSS Light: F(2, 28) = 6.409, p=0.0051). There was one main effect of treatment group (Fig. 6F: F(1, 14) = 4.759, p=0.0467) and only two post-hoc tests were significant (Fig. 6; (F) hours 0–3: p=0.0003 and hours 12–15: p=0.0022).

On withdrawal day 3, there was a main effect of time in most of the comparisons (Fig. 6; (G) FMN vs FSN Light: F(1.353, 24.35) = 27.98, p<0.0001; (H) FMN vs FMS Light: F(1.450, 20.29) = 30.19, p<0.0001; Dark: F(1.933, 27.06) = 8.917, p=0.0012; (I) FMS vs FSS Light: F(1.676, 23.46) = 19.28, p<0.0001); Dark: F(1.906, 26.69) = 4.477, p=0.0224). There was a significant interaction in FMS vs FSS Light cycle (Fig. 6I: F(2, 28) = 3.996, p=0.0297). All 3 experiments had a main effect of treatment group in the dark cycle (Fig. 6: (G) FMN vs FSN Dark: F(1, 18) = 9.909, p=0.0056; (H) FMN vs FMS Dark: F(1, 14) = 5.084, p=0.0407; (I) FMS vs FSS Dark: F(1, 14) = 21.55, p=0.0004). Post hoc tests showed two significant differences (Fig. 6; (G) hours 0–3: p=0.0095 and (I) hours 16–19: p=0.0084).

On the recovery day, all experiments had a main effect of time in the light, and one had a main effect of time in the dark (Fig. 6; (J) FMN vs FSN Light: F(1.960, 35.28) = 7.809, p=0.0017; (K) FMN vs FMS Light: F(1.446, 20.25) = 12.72, p=0.0007; Dark: F(1.437, 20.12) = 6.209, p=0.0135; (L) FMS vs FSS Light: F(1.981, 27.73) = 8.434, p=0.0014). There were no significant interactions, and only one main effect of treatment group (Fig. 6L: F(1, 14) = 7.243, p=0.0176). Hours 20–23 in the MMS vs MSS experiment were significant in Bonferroni’s post hoc (p=0.0475).

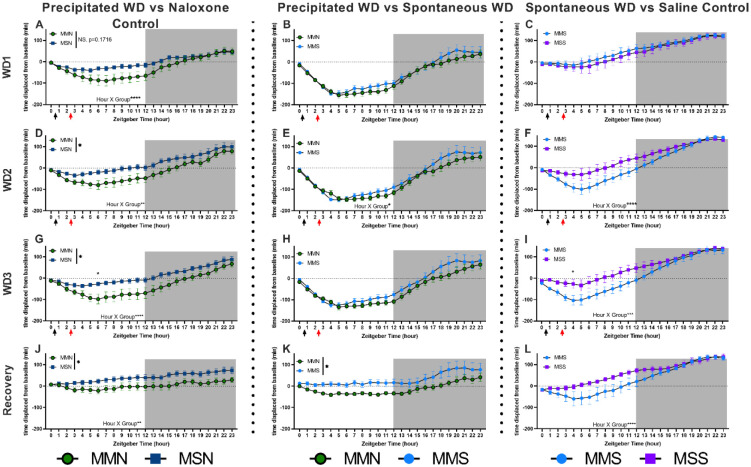

3.7. Male sleep displaced from baseline following withdrawal.

To investigate how individual animals shifted their sleep patterns during the treatment and withdrawal from opioids, we also examined the data as sleep displaced from baseline. All experiments are shown as cumulative minutes displaced from baseline across a 24-hour period. Percentages were converted to total minutes spent asleep and then subtracted from the total minutes slept up to that point during baseline for each individual animal [35]. On withdrawal day 1, no experiments showed main effects of treatment group between males. There was a significant interaction of cumulative time and group in the MMN vs MSN experiment (Fig. 7A F(23,414) =4.909, p<0.0001). On withdrawal day 2, only MMN vs MSN had a main effect of group (Fig. 7D F(1,18) =4.572, p=0.0465) and all three experiments had significant interactions (Fig. 7 (D) MMN vs MSN F(23,414) =2.018, p=0.0039; (E) MMN vs MMS F(23,322) =1.786, p=0.0157; (F) MMS vs MSS F(23,322)=3.536, p<0.0001). On withdrawal day 3, only MMN vs MSN had a main effect of group (Fig. 7G F(1,18) =5.462, p=0.0312) and a significant interaction (F(23,414) =2.938, p<0.0001), with a difference at hour 6 (p=0.0317). The MMS vs MSS experiment also showed a significant interaction (Fig. 7I F(23,322) =2.421, p=0.0004) where hour 4 showed significant differences (p=0.0468). On the recovery day, MMN vs MSN showed a main effect of group (Fig. 7J F(1,18) =5.109, p=0.0364) and a significant interaction (F(23,414) =1.931, p=0.0065). MMN vs MMS also showed a main effect (Fig. 7K F(1,14) =5.252, p=0.0379), but no significant interaction. Finally, MMS vs MSS showed a significant interaction (Fig. 7L F(23,322)=3.048, p<0.0001).

Figure 7. Cumulative difference in minutes of sleep of male mice during morphine exposure and withdrawal.

Minutes of sleep compared to each animal’s baseline sleep (within-subjects). Graph shows minutes of sleep subtracted from baseline minutes, cumulative by hour. Black arrows indicate morphine or saline injections (injection #1) and red arrows indicate saline or naloxone injections (injection #2). Each row is a different day (withdrawal days 1–3 and then recovery day 1). Every column is a different experiment (MMN vs MSN, MMN vs MMS, and MMS vs MSS). Grey box shows lights off. Data above 0 indicate a mouse had slept more by that point in the day than they did by that same hour during their baseline. Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

3.8. Female sleep displaced from baseline following withdrawal.

In the female mice, there were no significant differences in how each group differed from their baseline on withdrawal day 1. FMN vs FSN had a significant interaction (Fig. 8A F(23,414) =3.908, p<0.0001). On WD2, the FMN vs FMS experiment had a significant interaction (Fig. 8E F(23,322) =1.645, p=0.0332). On WD3, there was a main effect of group between FMN and FSN (Fig. 8G F(1,18) =4.573, p=0.0464). There was also a significant interaction in the FMS vs FSS experiment (Fig. 6I, F(23,322) =1.967, p=0.0057), which persisted to the recovery day (Fig. 8L, F(23,322) =37.01, p<0.0001). There were no other differences that lasted into the recovery days for females.

Figure 8. Cumulative difference in minutes of sleep of female mice during morphine exposure and withdrawal.

Minutes of sleep compared to each animal’s baseline sleep (within-subjects). Graph shows minutes of sleep subtracted from baseline minutes, cumulative by hour. Black arrows indicate morphine or saline injections (injection #1), and red arrows indicate saline or naloxone injections (injection #2). Each row is a different day (withdrawal days 1–3 and then recovery day 1). Every column is a different experiment (FMN vs FSN, FMN vs FMS, and FMS vs FSS). Grey box shows lights off. Data above 0 indicate a mouse had slept more by that point in the day than they did by that same hour during their baseline. Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

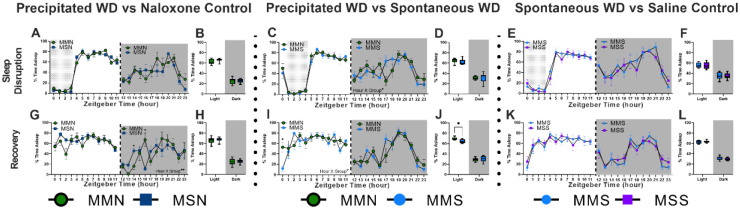

3.9. Sleep deprivation in male and female mice.

Following 6 days of forced abstinence where the mice were not manipulated by the investigators, we next conducted sleep deprivation assays. All mice were kept awake for 4 hours at the beginning of their light cycle, staring at either ZT0 or ZT1 (see methods). All male groups had significant main effects of time (Fig. 9; (A) MMN vs. MSN Light: F(5.220, 93.96) = 118.3, p<0.0001; Dark: F(6.145, 110.6) = 6.790, p<0.0001; (C) MMN vs. MMS Light F(3.476, 48.66) = 77.03, p<0.0001; Dark: F(5.943, 83.21) = 7.29, p<0.0001; (E) MMS vs. MSS Light F(3.739, 52.34) = 54.35, p<0.0001) Dark: F(5.787, 81.01) = 6.733, p<0.0001). The precipitated withdrawal group had a significant interaction (Fig. 9C, F(11, 154) = 2.311, p=0.0119).

Figure 9. Sleep behavior of male mice during sleep deprivation and recovery.

Sleep percentage of male mice undergoing sleep deprivation for 4 hours (A-F) and the day immediately following (G-L). Graphs are either 24-hour sleep percentages (A, C, E, G, I, K) or sleep percentage by light cycle (B, D, F, H, J, L). Columns are grouped by experiment (MMN vs MSN, MMN vs MMS, and MMS vs MSS). Grey box shows lights off and dotted region shows sleep disruption period. Each point or bar represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

One day following this sleep deprivation, MMN and MSN responded differently as noted by a significant interaction of group and time in the dark hours (Fig. 9G F(11, 198) = 2.552, p=0.0049). Hour 14 (p=0.0135) and hour 16 (p=0.0219) were both significant during post-hoc testing, but in opposite directions (Fig. 9G). Post-hoc analysis of the cycle averages showed that MMN mice slept significantly more than MMS mice (Fig. 9J, p=0.0438). MMN vs MMS also had a significant interaction (Fig. 9I F(11, 154) = 2.263, p=0.0139) with the difference occurring at hour 0 (p=0.0233). There were no significant differences between MMS and MSS. For the females, there were no significant interactions on the sleep deprivation day. While there was no interaction in the FMN vs FSN experiment, there was a significant difference at hour 21 (p=0.0163). On the recovery day, FMN vs FMS had a significant interaction of time and treatment group (Fig. 10J, F(11, 154) = 2.302, p=0.0123) and difference at hour 20 (p=0.0457).

Figure 10. Sleep behavior of female mice during sleep deprivation and recovery.

Sleep percentage of male mice undergoing sleep deprivation for 4 hours (A-F) and the day immediately following (G-L). Graphs are either 24-hour sleep percentages (A, C, E, G, I, K) or sleep percentage by light cycle (B, D, F, H, J, L). Columns are grouped by experiment (FMN vs FSN, FMN vs FMS, and FMS vs FSS). Grey box shows lights off and dotted region shows sleep deprivation period. Each point or bar represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

3.10. Sleep bout length during and following sleep deprivation in males and females.

On the sleep deprivation day, the males showed a main effect of time (Fig. 11; (A) MMN vs MSN Light: F(1.343, 24.18) = 13.38, p=0.0005; Dark: F(1.941, 34.94) = 4.964, p=0.0133; (B) MMN vs MMS Light: F(1.849, 25.89) = 31.06, p<0.0001; Dark: F(1.945, 27.24) = 9.977, p=0.0006; (C) MMS vs MSS Light: F(1.544, 21.62) = 18.93, p<0.0001). There was only one significant interaction (Fig. 11A: MMN vs MSN Dark: F(2,36)=3.578, p=0.0382) and post hoc result (Fig. 11A: MMN vs MSN hours 0–23 p=0.0259). The females showed significant main effect of time only in the light cycle (Fig. 12: (A) FMN vs FSN Light: F(1.387, 36.75) = 24.79, p<0.0001; (B) FMN vs FMS Light: F(1.634, 22.88) = 21.89, p<0.0001; (C) FMS vs FSS Light: F(1.279, 17.90) = 34.65, p<0.0001). There were no significant interactions, main effect of treatment group, or post hoc differences for the females.

Figure 11. Changes in male sleep bout length during and following sleep deprivation.

Graphs depict mean sleep bout in seconds per 4-hour bin of time. Each row is a different day (sleep deprivation day and then recovery day). (A) sleep deprivation MN vs SN bouts in 4-hour bins (B) sleep deprivation MN vs MS bouts in 4-hour bins (C) sleep deprivation MS vs SS bouts in 4-hour bins (D) recovery day MN vs SN bouts in 4-hour bins (E) recovery day MN vs MS bouts in 4-hour bins (F) recovery day MS vs SS bouts in 4-hour bins. Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Grey shading represents dark cycle hours.

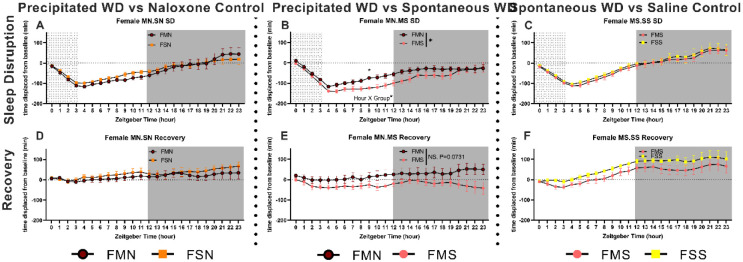

Figure 12. Changes in female sleep bout length during and following sleep deprivation.

Graphs depict mean sleep bout in seconds per 4-hour bin of time. Each row is a different day (sleep deprivation day and then recovery day). (A) sleep deprivation MN vs SN bouts in 4-hour bins (B) sleep deprivation MN vs MS bouts in 4-hour bins (C) sleep deprivation MS vs SS bouts in 4-hour bins (D) recovery day MN vs SN bouts in 4-hour bins (E) recovery day MN vs MS bouts in 4-hour bins (F) recovery day MS vs SS bouts in 4-hour bins. Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM): *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Grey shading represents dark cycle hours.

On the sleep deprivation recovery day, the males showed main effects of time in some experiments and cycles (Fig. 11: (D) MMN vs MSN Light: F(1.374, 24.73) = 9.910, p=0.002; (B) MMN vs MMS Dark: F(1.787, 25.02) = 7.217, p=0.0043; (C) MMS vs MSS Light: F(1.976, 27.66) = 5.178, p=0.0126). Males showed no significant interactions, main effect of treatment group, or post hoc differences. The females showed a significant main effect of time only in the light cycle (Fig. 12: (A) FMN vs FSN Light: F(1.893, 34.07) = 6.883, p=0.036; (B) FMN vs FMS Light: F(1.584, 22.17) = 11.49, p=0.0008; (C) FMS vs FSS Light: F(1.913, 26.78) = 34.79, p<0.0001). The females showed no significant interactions or main effect of the treatment group, but there was a post hoc difference for the females (Fig. 12C: hours 20–23 p=0.001).

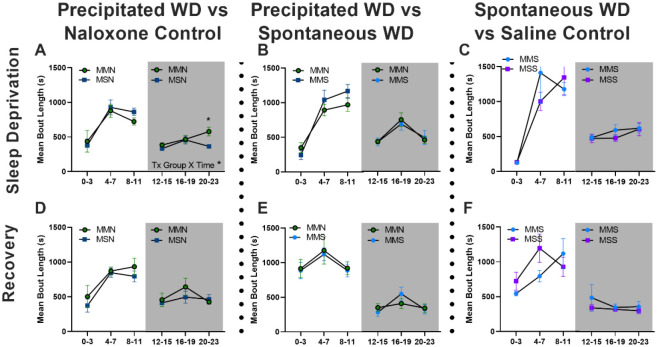

3.11. Cumulative minutes displaced from baseline sleep during sleep deprivation and recovery.

All male groups differed similarly from their baselines and there were no significant differences between groups on the sleep deprivation and recovery days (Fig. 13). Female precipitated withdrawal animals had significantly different sleep on the sleep deprivation day (Fig 14B, F(1,14)=4.721, p=0.0474) as well as a significant interaction of hour and group (F(23,322)=1.742, p=0.0199). By hour 9, the FMS group had slept more than 100 minutes less than their sleep up to hour 9 on their baseline. On the following day, the FMN vs FMS experiment was trending towards being significantly different (Fig. 14E, p=0.0731).

Figure 13. Cumulative difference in minutes of sleep of male mice during sleep disruption and recovery.

Minutes of sleep compared to each animal’s baseline sleep (within-subjects) on sleep deprivation and recovery days. Graph shows minutes of sleep subtracted from baseline minutes, cumulative by hour. Every column is a different experiment (FMN vs FSN, FMN vs FMS, and FMS vs FSS). Grey box shows lights off and dotted region shows sleep deprivation period. Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Figure 14. Cumulative difference in minutes of sleep of female mice during sleep deprivation and recovery.

Minutes of sleep compared to each animal’s baseline sleep (within-subjects) on sleep deprivation and recovery days. Graph shows minutes of sleep subtracted from baseline minutes, cumulative by hour. Every column is a different experiment (FMN vs FSN, FMN vs FMS, and FMS vs FSS). Grey box shows lights off and dotted region shows sleep deprivation period. Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM): *P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Sleep is governed by multiple brain regions and neurotransmitters. EEG studies have identified the various regions involved in stages of sleep including portions of cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, basal forebrain and others [36–38]. Many brain regions known to be involved in sleep are also implicated in addiction/reward circuitry and stress systems. In particular, monoaminergic nuclei have been largely implicated in regulating sleep behavior. The locus coeruleus (LC) projects to the basal forebrain, bringing dense noradrenergic inputs that are known to correlate with arousal states. The LC is the beginning of a wake-promoting circuit that uses monoaminergic signaling through the midbrain and to the frontal cortex and receives feedback from orexinergic neurons in the lateral hypothalamus [40]. Increased activation of the LC promotes arousal, and decreased activation of the LC results in increases in NREM sleep [40]. During opioid withdrawal, the LC neurons are activated and there is an increase in norepinephrine in the ventral forebrain that drives opioid withdrawal-induced aversion [41]. There is also an increase in norepinephrine in the ventral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (vBNST) following opioid withdrawal, although the source of this NE is mainly from the medullary noradrenergic neurons which have a less well-defined role in sleep [42,43]. The ventral tegmental area (VTA is considered the preeminent common substrate for all rewarding substances and reinforcing behaviors. It sends dopamine to the nucleus accumbens and is highly implicated in facilitating rewarding behaviors and self-administration of drugs. The VTA consists of both dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic (GABAergic) neurons, each which have been shown to play a role in the control of sleep behaviors [44,45]. The GABAergic neurons in the VTA show increased firing during REM sleep and decreased firing during waking behaviors [44]. These neurons synapse onto other GABA-neurons as well as onto the DA neurons in the VTA [46]. Inhibition of these dopamine neurons results in sleep induction and sleep preparation behaviors such as nest-building [45].

Here we examined how different paradigms of opioid withdrawal (and their respective controls) modulate sleep behavior in male and female mice using a non-invasive sleep measurement across multiple days and during a 4-hour sleep deprivation and recovery. We compare a 3-day precipitated morphine withdrawal paradigm that we and others have used to model the development of opioid dependence/tolerance as compared to spontaneous withdrawal from the same dose of morphine. We also compare these paradigms to their respective controls measured concurrently. Our data suggests that repeated withdrawal dysregulates sleep behavior, and the precipitated withdrawal paradigm results in greater sleep dysregulation, including subsequent drug-free recovery days and alterations in sleep drive following sleep deprivation. Additionally, we observed differences in some of these metrics between male and female subjects, and confirm sleep differences at baseline between male and female C57BL6/J mice.

4.1. Difference in baseline sleep behaviors in male and female mice.

In this study, we compared our model of OUD – a 3-day precipitated morphine withdrawal paradigm which results in acute withdrawal responses (ie. sensitization of escape jumps, paw tremors, and fecal boli over 3 days [25]) as well as protracted withdrawal responses (ie. changes in open field behaviors, social interaction, and increased locomotion[5]) -- to spontaneous morphine withdrawal, in the context of sleep dysregulation. Our previous studies also began to tease apart the sex differences that occur during acute and protracted withdrawal. We conducted these paradigms inside our PiezoSleep chambers and examined the effects of morphine withdrawal on the sleep behaviors of male and female C57B6/J mice (Fig. 1). We saw that male and female C57B6/J mice sleep differently at baseline, with the males sleeping on average 58.3% of the light cycle and 22.9% of the dark cycle while females slept 52.0% of the light cycle and 22.6% of the dark cycle (Fig. 2). Additionally, the mean sleep bout length varied between male and female mice (Fig. 2). This pattern in sleep differences between males and females is consistent with observations in healthy adult humans [47]. Once we established baseline sleep behaviors, mice were exposed to morphine followed by withdrawal. Our previous studies indicate that experiences during acute withdrawal may have both immediate and long-lasting effects [5,25]. Due to the significant difference between male and female baselines, the sexes are only compared qualitatively for the remainder of the discussion.

4.2. Validation of effects during precipitated withdrawal paradigm.

We showed that our previously published naloxone-precipitated morphine withdrawal paradigm results in sleep disruptions similar to observations in clinical reports [13,14,21]. Morphine results in decreased sleep in the light cycle and increased sleep in the dark cycle for both males and females across all three days of injections (Fig. 3 & 4). We observed correlating changes in the length of sleep bouts. Morphine exposure resulted in decreased bout length in the light cycle and increased bout length in the dark cycle (Fig. 5 & 6). This parallels the human experience in which those taking opioids or withdrawn from opioids report increased daytime sleepiness followed by insomnia at night [48–51]. Naloxone injections, on the other hand, result in an immediate increase in sleep in either male or female animals (Fig.3 A, B; Fig.4 A, B). In non-opioid-dependent people, naloxone alone results in increased latency to reach REM sleep, duration of REM, and number of REM cycles [52]. These effects are likely due to activation of the LC, which only ceases firing during REM sleep. In those with an OUD, maintenance treatment with buprenorphine and naloxone (Suboxone) results in improved sleep compared to those going through treatment without the combination therapy, but the sleep patterns do not return to baseline [53–55]. Across all our mice, the total percent time spent sleeping and total mean bout length for the day were not different between groups on any given day. This result suggests that sleep displaced by morphine exposure and withdrawal was gained at other time periods during the day. It is unlikely that this finding is consistent with human behavior given the environmental and social pressures to be active or productive during the day. For example, one study found that illicit opioid use decreased the amount of sleep its participants achieved, but so did having earlier scheduled urinalysis appointments [56]. These data highlight that the effects of sleep alterations could be more impactful in humans. Future studies could mimic the requirements/daily pressures human life, such as working for food or sleep deprivation (see below), and explore how these changes further impact sleep behavior.

4.3. Sleep disruptions continue into the first day of abstinence in both male and female mice.

While the 3-day precipitated withdrawal paradigm was originally developed to promote the rapid development of opioid dependence, the current opioid epidemic has resulted in people receiving doses of Narcan® (naloxone) to alleviate respiratory depression and save lives. The rates of people receiving multiple doses of Narcan from Emergency Medical Services is on the rise (up 26% from 2012–2015 [9] and up 84.8% in Guilford County, NC from pre-COVID to 2021[10]). The increasing frequency of repeated withdrawals and repeated dosing of naloxone begs the question of what rapid withdrawal itself, not merely opioid exposure and spontaneous withdrawal, does to the brain. Here, we see that there are acute effects of morphine withdrawal on sleep that persist into the day following the last exposure and withdrawal. Both males and females show interactions between the hour and treatment group, across all experiments (Fig. 3,4: S,U,W). Male morphine-naloxone mice showed a significant reduction in sleep during the light phase (similar to the time point where they received morphine/naloxone on the preceding days), as well as an increase in sleep during the dark when compared to their saline-naloxone controls (Fig. 3T). This is not the case, however, for females (Fig. 4T). The persistence of disruptions 24–36 hours after the last dose of morphine is comparable to that seen in the human condition, where studies have shown disruptions may never completely disappear due to external stressors (see discussion on sleep deprivation below) [54,55]. At this same 24-hour time point, our lab has shown that GABAergic signaling in the BNST is altered following opioid withdrawal [25]. Intriguingly, the plasticity was different in males and females: males exhibited increased frequency of spontaneous IPSCs, while the females showed decreased frequency of sIPSCs. An increase in GABAergic signaling in the BNST might result in a disinhibition of VTA GABA neurons, which have been shown to have decreased activity during awake states [25,44]. This circuit provides a potential explanation given the differences in GABA signaling and sleep behaviors in acute withdrawal. We have also examined various behaviors 6 weeks following precipitated withdrawal and seen several sex differences [5]. These data indicate that in the future, it might be beneficial to observe sleep behavior at a more protracted time point similar to our previous studies of protracted withdrawal behavior [5].

4.4. Within-animal comparisons elucidate differential responses by male and female mice.

In addition to assessing the sleep percentage by hour, we have examined sleep behavior by calculating cumulative difference in minutes of sleep obtained throughout the day compared to baseline sleep. This form of analysis considers within-subject variability and allows each mouse to serve as their own baseline. Here, we can more clearly visualize the effect of naloxone in combination with morphine on male mice (Fig. 7K). On the recovery day, males, but not females, exhibited a significant main effect between precipitated and spontaneous withdrawal groups. This finding is particularly interesting given that precipitated and spontaneous withdrawal groups behaved almost identically to each other on the three days of withdrawal, with only a significant interaction of hour and group on WD2 (Fig. 7E). However, during acute withdrawal, precipitated withdrawal animals slept significantly less than spontaneous withdrawal animals, indicating a role of withdrawal severity on symptoms (Fig. 7K). For the females, spontaneous and precipitated withdrawal groups had a significant interaction but no other effects (Fig. 8E). These findings indicate that male mice may be more affected by the combination of morphine and naloxone than female mice, specifically at the 1mg/kg dose of naloxone. One clinical study showed that women are more likely than men to use opioids while on a buprenorphine/naloxone treatment [57], and another concluded that women and men respond differently to naloxone depending on the dose [58].

4.5. Sleep deprivation one week after withdrawal result in changes in sleep on recovery day in males and females.

Examining sleep behaviors following sleep deprivation allows us to analyze how our manipulations alter homeostatic sleep drive. Sleep deprivation, however, is also a stressor that many of us experience in our daily lives. Therefore, we wanted to observe how a 4-hour sleep deprivation early in the dark cycle would alter future sleep behavior. We performed these experiments 6 days after the final drug treatments because all mice returned to regular sleep cycles by day 3 of recovery (data not shown). We observed interesting qualitative differences between the sexes. Examining precipitated withdrawal vs. naloxone control groups on the day of sleep deprivation, we observed no differences in male mice, however male mice exhibit significant interactions and timepoint differences on the day following sleep deprivation (Fig. 9B). Again, we observed enhanced waking behavior at hour 2 and enhanced sleep at hour 16, mimicking what was observed on recovery day 1. Female mice, in contrast, have a significant treatment-by-hour interaction on the day of the sleep deprivation, and females that had previously experienced precipitated withdrawal had enhanced active-period sleepiness in hours 20 and 21 (Fig. 10A) but did not show significant differences the following day. Interestingly, male mice did not differ between spontaneous and precipitated withdrawal on the day following a sleep deprivation, with both groups sleeping more than they did at baseline (Fig. 13E). However, female mice who had gone through precipitated withdrawal slept more than they did at baseline while those who has gone through spontaneous withdrawal prior to sleep deprivation slept less than their baseline (Fig.14E). Together, these changes might indicate that stressors occurring during abstinence impact male and female mice differently and that females may be more sensitive to the type of withdrawal experienced. We know that stress is often a driving force behind relapse to drug-taking behavior and preclinical data implicates noradrenergic signaling in the extended amygdala in reinstatement [59–61]. Sleep, stress, and opioid signaling overlap in these extended amygdala circuits, and all utilize noradrenergic signaling. Additional studies are needed to determine the impact of these specific circuits on sleep behavior in withdrawal, but they present a space for interesting sex differences.

Our main finding is that male mice are more sensitive to morphine withdrawal-induced acute sleep disturbances than female mice, but female mice might be more sensitive to future sleep-related stressors.

4.6. Limitations.

Sleep patterns are very specific to individuals due to the drive of social and environmental pressures in addition to genetic and biological drivers. As such, we see a lot of variability between subjects. This variability can often make it hard to identify real treatment effects. There can also be a lot of variability due to environmental changes. For example, the MS vs. SS experiment varies from the other experiments run in this study. We believe these differences are due to vivarium variability between experiments and this underscores the importance of conducting simultaneous controls. We feel confident that the effects we report are real because our results were consistent across all animals in two cohorts. Additionally, the within-subjects’ normalization of the data (Figures 7, 8, 13, and 14) confirms the overall trends we see in between-subjects’ comparisons. It is important to note that C57B6/J mice, and many other inbred strains, are deficient in their melatonin production, a hormone important in regulating sleep [62–66]. Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of outbred strains or a panel of inbred strains.

4.7. Conclusions

Our study here is foundational for our future work examining sleep and opioids, and further validates the 3-day morphine withdrawal paradigm as a model for OUD that captures elements of the human condition in a mouse model where signaling and circuits can be assessed.

Highlights.

Morphine withdrawal differentially dysregulates the sleep of male and female mice

3-day precipitated withdrawal results in larger changes than spontaneous withdrawal

Opioid withdrawal affects responses to future sleep deprivation differently between sexes

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Foundation of Hope; UNC-Pharmacological Sciences T32 [5T32GM135095]; National Institute of Drug Abuse [R01DA049261].

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:

The authors M. Bedard and Dr. McElligott are sub-contracted by EpiCypher® on a SBIR grant unrelated to the work completed in this article.

References

- [1].CDC, Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts, 2021.

- [2].Han B., Compton W.M., Blanco C., Crane E., Lee J., Jones C.M., Ann Intern Med 167 (2017) 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Strang J., Volkow N.D., Degenhardt L., Hickman M., Johnson K., Koob G.F., Marshall B.D.L., Tyndall M., Walsh S.L., Nat Rev Dis Primers 6 (2020) 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Adapt Pharma, NARCAN (Naloxone Hydrochloride) Nasal Spray, n.d.

- [5].Bravo I.M., Luster B.R., Flanigan M.E., Perez P.J., Cogan E.S., Schmidt K.T., McElligott Z.A., Eur J Neurosci 51 (2020) 742–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shaw L.V., Moe J., Purssell R., Buxton J.A., Godwin J., Doyle-Waters M.M., Brasher P.M.A., Hau J.P., Curran J., Hohl C.M., Syst Rev 8 (2019) 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Buresh M., Gicquelais R.E., Astemborski J., Kirk G.D., Mehta S.H., Genberg B.L., PLoS ONE 15 (2020) e0230127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dahan A., Aarts L., Smith T.W., Anesthesiology 112 (2010) 226–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Faul M., Lurie P., Kinsman J.M., Dailey M.W., Crabaugh C., Sasser S.M., Prehospital Emergency Care 21 (2017) 411–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Khoury D., Preiss A., Geiger P., Anwar M., Conway K.P., JMIR Public Health Surveill 7 (2021) e29298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Arnedt J.T., Conroy D.A., Brower K.J., Journal of Addictive Diseases 26 (2007) 41–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gates P., Albertella L., Copeland J., Substance Abuse 37 (2016) 255–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Huhn A.S., Finan P.H., Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [14].Hartwell E.E., Pfeifer J.G., McCauley J.L., Moran-Santa Maria M., Back S.E., Addictive Behaviors 39 (2014) 1537–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Beswick T., Best D., Rees S., Bearn J., Gossop M., Strang J., Addiction Biology 8 (2003) 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dimsdale J.E., Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 3 (2022) 4. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Brower K.J., Aldrich M.S., Hall J.M., Alcoholism Clin Exp Res 22 (1998) 1864–1871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Brower K.J., Aldrich M.S., Robinson E.A.R., Zucker R.A., Greden J.F., AJP 158 (2001) 399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Foster J.H., Peters T.J., Alcoholism Clin Exp Res 23 (1999) 1044–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Maulik P.K., Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (2002) 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lydon-Staley D.M., Cleveland H.H., Huhn A.S., Cleveland M.J., Harris J., Stankoski D., Deneke E., Meyer R.E., Bunce S.C., Addictive Behaviors 65 (2017) 275–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].De Andrés I., Caballero A., Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 32 (1989) 519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Coffey A.A., Guan Z., Grigson P.S., Fang J., Brain Research Bulletin 123 (2016) 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Stevens S., Mohan S., Heliyon 7 (2021) e06694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Luster B.R., Cogan E.S., Schmidt K.T., Pati D., Pina M.M., Dange K., McElligott Z.A., Addiction Biology 25 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Puig S., Shelton M.A., Logan R.W., The Journal of Pain 23 (2022) 59. [Google Scholar]

- [27].O’Brien C.B., Locklear C.E., Glovak Z.T., Zebadúa Unzaga D., Baghdoyan H.A., Lydic R., Journal of Neurophysiology 126 (2021) 1265–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zebadua Unzaga D., Bustamante C., Thibert M., Baghdoyan H., FASEB j. 35 (2021) fasebj.2021.35.S1.01706. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Flores A. E., Flores J. E., Deshpande H., Picazo J. A., Xie X., Franken P., Heller H. C., Grahn D. A., O’Hara B. F., IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 54 (2007) 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Donohue K.D., Medonza D.C., Crane E.R., O’Hara B.F., BioMed Eng OnLine 7 (2008) 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mang G.M., Nicod J., Emmenegger Y., Donohue K.D., O’Hara B.F., Franken P., Sleep 37 (2014) 1383–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Klerman E.B., Wang W., Phillips A.J.K., Bianchi M.T., J Biol Rhythms 32 (2017) 18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Verma J.P., Repeated Measures Design for Empirical Researchers., John Wiley and Sons, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [34].McElligott Z.A., Fox M.E., Walsh P.L., Urban D.J., Ferrel M.S., Roth B.L., Wightman R.M., Neuropsychopharmacol 38 (2013) 1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Naidoo N., Ferber M., Galante R.J., McShane B., Hu J.H., Zimmerman J., Maislin G., Cater J., Wyner A., Worley P., Pack A.I., PLoS ONE 7 (2012) e35174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Motomura Y., Kitamura S., Oba K., Terasawa Y., Enomoto M., Katayose Y., Hida A., Moriguchi Y., Higuchi S., Mishima K., PLoS ONE 8 (2013) e56578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zielinski M. R., McKenna J. T., McCarley R. W., 1 Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, West Roxbury, MA 02132, USA and Harvard Medical School, Department of Psychiatry, AIMS Neuroscience 3 (2016) 67–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yoo S.-S., Gujar N., Hu P., Jolesz F.A., Walker M.P., Current Biology 17 (2007) R877–R878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Krause A.J., Prather A.A., Wager T.D., Lindquist M.A., Walker M.P., J. Neurosci. 39 (2019) 2291–2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Scammell T.E., Arrigoni E., Lipton J.O., Neuron 93 (2017) 747–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Delfs J.M., Zhu Y., Druhan J.P., Aston-Jones G., Nature 403 (2000) 430–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Cheng C.-H., Yi P.-L., Lin J.-G., Chang F.-C., Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011 (2011) 159209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Fox M.E., Rodeberg N.T., Wightman R.M., Neuropsychopharmacol 42 (2017) 671–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lee R.-S., Steffensen S.C., Henriksen S.J., J. Neurosci. 21 (2001) 1757–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Eban-Rothschild A., Rothschild G., Giardino W.J., Jones J.R., de Lecea L., Nat Neurosci 19 (2016) 1356–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bouarab C., Thompson B., Polter A.M., Front. Neural Circuits 13 (2019) 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ohayon M.M., Carskadon M.A., Guilleminault C., Vitiello M.V., Sleep 27 (2004) 1255–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Pickworth W.B., Neidert G.L., Kay D.C., Clin Pharmacol Ther 30 (1981) 796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lewis S., Oswald I., Evans J., Akindele M., Tompsett S., (1969) 8.

- [50].Oyefeso A., Sedgwick P., Ghodse H., Drug and Alcohol Dependence 48 (1997) 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Zgierska A., Brown R.T., Zuelsdorff M., Brown D., Zhang Z., Fleming M.F., Journal of Opioid Management 3 (2007) 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sitaram N., Gillin J.C., Brain Research 244 (1982) 387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Baykara S., Alban K., Psychiatry Research 272 (2019) 450–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Howe R.C., Phillips J.L., Hegge F.W., Drug and Alcohol Dependence 7 (1981) 163–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Martin W.R., Arch Gen Psychiatry 28 (1973) 286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Bertz J.W., Epstein D.H., Reamer D., Kowalczyk W.J., Phillips K.A., Kennedy A.P., Jobes M.L., Ward G., Plitnick B.A., Figueiro M.G., Rea M.S., Preston K.L., Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 106 (2019) 43–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Barbosa-Leiker C., McPherson S., Layton M.E., Burduli E., Roll J.M., Ling W., The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 44 (2018) 488–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Chopra M., Feldman Z., Mancino M., Oliveto A., Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 90 (2008) 787–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Schmidt K.T., Makhijani V.H., Boyt K.M., Cogan E.S., Pati D., Pina M.M., Bravo I.M., Locke J.L., Jones S.R., Besheer J., McElligott Z.A., ACS Chem. Neurosci. 10 (2019) 1908–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Erb S., Neuropsychopharmacology 23 (2000) 138–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Shaham Y., Highfield D., Delfs J., Leung S., Stewart J., European Journal of Neuroscience 12 (2000) 292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Conti A., Maestroni G.J.M., Journal of Pineal Research 20 (1996) 138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Ebihara S., Marks T., Hudson D.J., Menaker M., Science 231 (1986) 491–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kasahara T., Abe K., Mekada K., Yoshiki A., Kato T., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 (2010) 6412–6417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Roseboom P.H., Namboodiri M.A.A., Zimonjic D.B., Popescu N.C., Rodriguez I.R., Gastel J.A., Klein D.C., (1998) 9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [66].Tosini G., Owino S., Guillaume J.-L., Jockers R., BioEssays 36 (2014) 778–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]