Abstract

Aims

While mexiletine has been used for over 40 years for prevention of (recurrent) ventricular arrhythmias and for myotonia, patient access has recently been critically endangered. Here we aim to demonstrate the effectiveness and safety of mexiletine in the treatment of patients with (recurrent) ventricular arrhythmias, emphasizing the absolute necessity of its accessibility.

Methods and results

Studies were included in this systematic review (PROSPERO, CRD42020213434) if the efficacy or safety of mexiletine in any dose was evaluated in patients at risk for (recurrent) ventricular arrhythmias with or without comparison with alternative treatments (e.g. placebo). A systematic search was performed in Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and in the clinical trial registry databases ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP. Risk of bias were assessed and tailored to the different study designs. Large heterogeneity in study designs and outcome measures prompted a narrative synthesis approach. In total, 221 studies were included reporting on 8970 patients treated with mexiletine. Age ranged from 0 to 88 years. A decrease in ventricular arrhythmias of >50% was observed in 72% of the studies for pre-mature ventricular complexes, 64% for ventricular tachycardia, and 33% for ventricular fibrillation. Electrocardiographic effects of mexiletine were small; only in a subset of patients with primary arrhythmia syndromes, a relative (desired) QTc decrease was reproducibly observed. As for adverse events, gastrointestinal complaints were most frequently observed (33% of the patients).

Conclusions

In this systematic review, we present all the currently available knowledge of mexiletine in patients at risk for (recurrent) ventricular arrhythmias and show that mexiletine is both effective and safe.

Keywords: Mexiletine, Systematic review, Ventricular arrhythmias

Introduction

Patients at risk for recurrent ventricular arrhythmias can be treated with anti-arrhythmic drugs or ablations.1 For example, the anti-arrhythmic agents currently known as quinidine and digoxin have already been used for the treatment of palpitations since the 18th century.2,3 Over time, more drugs were developed and became available for the treatment of arrhythmias.1,4 However, the tide has turned after the pivotal anti-arrhythmic drug developments in the 1960s to 1980s. Since the late 1990s and early 2000s, anti-arrhythmic drugs may no longer be sufficiently profitable for the pharmaceutical industry and anti-arrhythmic drug availability has actually decreased in many countries around the globe.5 As a consequence, the pharmaceutical treatment of numerous patients with (life-threatening) ventricular arrhythmias has become increasingly difficult.5–8

Mexiletine, a sodium channel blocker and the oral lidocaine equivalent, is such an example. Mexiletine is predominantly prescribed in both cardiology and neurology. Mexiletine was initially developed as an anti-arrhythmic drug by Boehringer Ingelheim and the first results were presented in 1973.9 Although other anti-arrhythmic drugs, such as sotalol and amiodarone, surpassed mexiletine over time with regards to efficacy and safety (e.g. mortality),10 it still can be very effective drug in specific subgroups of patients. In cardiology, mexiletine is most often prescribed to adult patients with recurrent ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation (VT/VF) when other therapies have failed, and to paediatric and adult patients with severe forms of the long QT syndrome (LQTS). This use of mexiletine has also been mirrored in successive international guidelines on the prevention of VT/VF.1,11 In neurology, mexiletine has proved effective in paediatric and adult patients with the disabling neuromuscular disorder non-dystrophic myotonia.12,13 In addition, mexiletine is sometimes successfully used for pain syndromes.14

Despite the use of mexiletine for over 40 years as an anti-arrhythmic drug, the accessibility of mexiletine in Europe is now critically endangered. After Boehringer Ingelheim withdrew Mexitil from the European market, patients had to rely on named patient import from other countries, including Canada and Japan. In 2018, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) authorized mexiletine (Namuscla, Lupin Europe GmbH, Germany) for the treatment of the neurological indication non-dystrophic myotonia as an orphan drug. The rationale behind the European (and e.g. USA) orphan drug legislation is to promote commercial interest for the development of new products for rare diseases assuming that such products will otherwise not be developed.6 This legislation was developed without exclusion of existing drugs from orphan designation, among others (Postema, 2020 #1603). This authorization of Namuscla as orphan drug for the neurological indication granted a 10-year market exclusivity. Not unexpectedly, the price of Namuscla was raised up to >30-fold for both neurology and cardiology in comparison with imported generic products, resulting in reimbursement issues.6,15,16 Remarkably, the contra-indications of Namuscla now include ventricular tachyarrhythmias and previous myocardial infarction while the guidelines on the treatment and prevention of VT/VF mexiletine can actually be an effective and safe drug of choice.1,11 This may constrain the off-label use of Namuscla for VT/VF. Herewith, the accessibility of mexiletine to prevent ventricular arrhythmias (and for the treatment of myotonia) is further compromised. This in turn may have life-threatening consequences.6

If the effectiveness and safety of mexiletine in patients at risk for (recurrent) ventricular arrhythmias would be demonstrated, this would prove the clear needs of its accessibility. Therefore, a systematic review to summarize all available efficacy and safety data was conducted.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines and registered in the International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews (CRD42020213434).17

Selection criteria

Studies were included in this systematic review if the efficacy and/or safety of mexiletine in any dose or route of administration were evaluated in patients at risk for (recurrent) ventricular arrhythmias with or without comparison with alternative treatments (e.g. placebo, other anti-arrhythmic drugs). Only studies with original data published in peer-reviewed journals were included and no restrictions in study design applied.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search using controlled terms and free text terms for the concepts (i) mexiletine (or brand names including, but not limited to, Mexitil and Ritalmex) and (ii) ventricular arrhythmias was performed in the Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and in the clinical trial registry databases [ClinicalTrials.gov, International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) registry]. The search was restricted to studies in human subjects, no other date or language restrictions applied. The search was performed on 22 October 2020. In the Supplemental material, the complete search strategy is presented. The identified records were imported into reference management tool Endnote (X9.2; Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and duplicates were removed.

Study selection and critical appraisal

Titles, abstracts, and subsequently the acquired relevant full-text articles were independently assessed by two reviewers (M.H.R., L.D.) for eligibility using Rayyan (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar).18 The assessment of methodological quality and risk of bias was performed independently by the review team (M.H.R., L.D., N.R., N.S., S.B., and V.W.) and tailored to the different study designs, discrepancies were resolved by discussion. For case reports and case series, the tool developed by Murad and colleagues19 was used, for non-randomized intervention studies, the ROBINS-1 tool was used,20 and for randomized studies, the ROB2 tool was used.21 In case no efficacy but only safety data about mexiletine was reported, risk of bias was not assessed. As the different tools have different (overall) scores, a 3-point scale [low, moderate (some concerns), and high (critical and serious)] was constructed to enhance comparability.

Data collection and analysis

Baseline characteristics, mexiletine details (e.g. daily dose), follow-up, and outcomes were independently extracted by two members of the review team per study (M.H.R., L.D., N.R., N.S., S.B., and V.W.) using a standardized extraction form in Castor EDC,22 discrepancies were resolved by discussion during weekly meetings or by consultation of a third reviewer. Data were processed and aggregated using R version 4.0.3. Outcome data included both efficacy as well as safety and survival data. Efficacy outcome data were further stratified in effects of mexiletine on the ventricular arrhythmia burden [consisting of the burden of pre-mature ventricular complexes (PVCs), sustained VT or VF], changes in electrophysiological parameters [VT inducibility, VF inducibility, effects on cycle length, and effective refractory period (ERP)], and changes in electrocardiographic parameters [heart rate, QRS-duration, corrected QT interval (QTc)]. For the electrocardiographic changes, the results are subdivided into patients with and patients without primary arrhythmia syndrome. In case multiple subtypes of LQTS were reported in one study, by virtue of pathology, LQTS type 3 was the preferred outcome for extraction.23 If available, pre-post mexiletine outcome data were used so that patients served as their own controls. Safety data included adverse events, left and right ventricular ejection fraction, drug–drug interaction, and the occurrence of worsening of arrhythmias. Adverse events were scored according to the definitions of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0, no grading was applied. If the adverse events were not reported in enough detail, only the organ system was scored. For the presentation of the adverse events, the organ systems with ≥3% adverse event incidences were reported. The incidence of the adverse events is reported relative to the evaluable patients from studies reporting that specific adverse event and presented for events with ≥3% incidence. Efficacy and safety data were summarized per stratified outcome measure in the manuscript. Efficacy data from studies considered to have a high risk of bias were excluded from the main efficacy results. Safety data from these high risk of bias studies were, however, included in the main safety results to present a complete overview of all reported adverse events available. Mexiletine was considered pro-arrhythmic if the arrhythmia worsened after the start of mexiletine [e.g. an increase in the number of PVCs or development of more malignant arrhythmias (e.g. from VT at baseline to VF during mexiletine treatment)]. The study data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Results

Search results and risk of bias

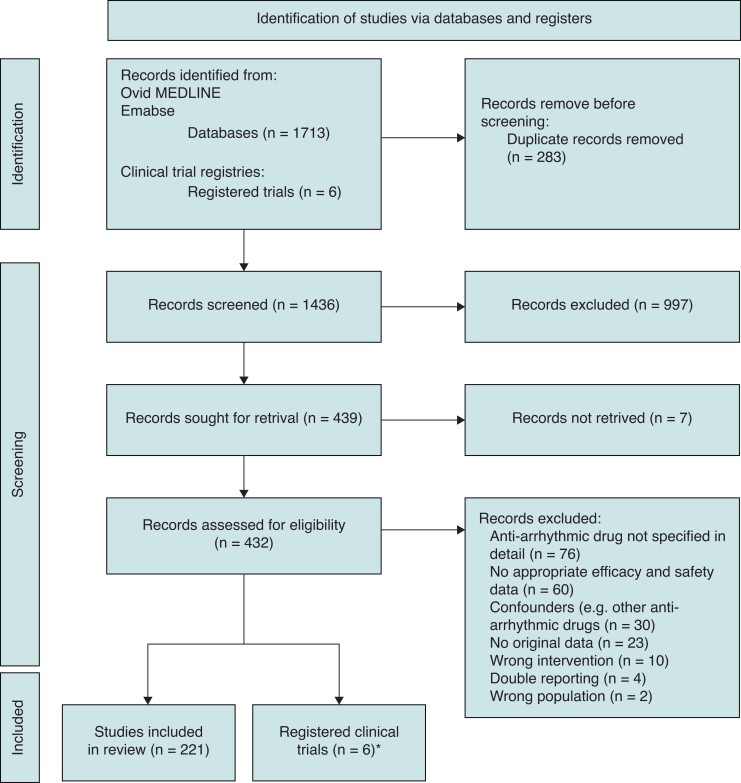

Of the 1436 unique records identified, of which after screening based on title and abstract 432 (30%) records were assessed for eligibility, 221 (15%) studies were included in this systematic review. In Figure 1, a flow chart of the study selection is presented. Efficacy was reported in 174 (79%) of the studies (efficacy and safety: n = 126; only efficacy: n = 48), 33 (19%) were considered low risk, 80 (46%) moderate risk, and 61 (35%) high risk of bias. In 173 (78%) studies, safety was reported (efficacy and safety: n = 126; only safety: n = 47).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study inclusion.

Baseline characteristics

In total, 8970 patients have reportedly been treated with mexiletine. Sex was reported in 4647 (52%) patients, and of these, the majority were males (n = 3322, 72%). The patient age in the studies ranged from 0 to 88 years. Of the studies reporting mean age, the weighted average was 56.5 years. Of 5131 patients, a diagnosis category was extractable. The most frequent diagnosis was ischaemic heart disease (n = 3671, 72%), followed by non-ischaemic heart disease (n = 720, 14%) and primary arrhythmia syndromes n = 144, 3%). Of patients with a primary arrhythmia syndrome, 132 (91%) were diagnosed with LQTS. The remaining group of patients received other diagnoses (e.g. idiopathic PVC). From the 174 studies reporting on efficacy, 60 (35%) studies included therapy-resistant patients in whom previous conventional therapy was ineffective. In 157 (71%) studies, the route of administration was oral. In 24 (11%) studies, mexiletine was administered intravenously. In 13 (6%) studies, both routes of administration were used. Intramuscular administration of mexiletine was used in 1 (0.5%) study, while in 26 (12%) studies, the route of administration was not reported. Doses ranged from 50–2400 mg/day to 1–42 mg/kg/day.

Outcome

In this section, an overview of the results is presented. In the supplementary excel file, we present the extracted data for the individual studies per outcome measure. In this supplement, it is possible to filter on (multiple) variables, for example in order to select studies with a specific follow-up duration, mexiletine dose, or certain arrhythmia burden cut-offs.

Data on effectiveness of mexiletine

Results of individual studies are presented in the supplements.

Ventricular arrhythmia burden

Efficacy of mexiletine with regards to the ventricular arrhythmias is further stratified in the burden of PVC (n = 61 studies), VT (n = 34 studies), and VF (n = 12 studies). Table 1 shows the study details and outcomes. For the PVC burden, in the 38 studies (n = 1143 evaluable patients) in which a percentage change was reported or calculable, 27 (72%) studies comprising 877 evaluable patients showed a reduction of >50% in PVC burden. In 8 studies (21%, n = 197 patients), this reduction percentage was >80%.24–31 For the studies that applied a cut-off value for efficacy, the results are presented in Table 1. For the VT burden, in the 11 studies (n = 412 evaluable patients) in which a percentage change was reported or calculable, 7 (64%) studies, comprising 237 evaluable patients, showed a reduction of >50% in VT burden. Two studies applied a cut-off of >75% for efficacy, 74% of the patients met this criterion. Twenty-one studies applied a cut-off of 100%, in those studies 90% of the patients met this criterion (Table 1). For VF burden, in the 3 studies (n = 171 evaluable patients) in which a percentage change was reported or calculable, 1 (33%) study comprising of 34 evaluable patients showed a reduction of >50% in VF occurrence.100 Nine studies applied a cut-off of 100%, 90% of the patients met this criterion (Table 1). In only two studies (n = 2 patients), ICDs were implanted.100,101 In the studies with recurrences, details on the episodes (sustained vs. unsustained) were sparsely reported. Worsening of arrhythmias is discussed in the ‘Safety and surival data’ section. For patients with LQTS, efficacy of mexiletine in VF reduction is reported in three studies (n = 40 patients, LQTS type 3: 100%),100–102 a reduction of >90% was achieved in 39 (98%) of these patients.100,102

Table 1.

The effect of mexiletine on ventricular arrhythmia burden

| Arrhythmias | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publications, n (%) | Study design | Follow-up range | Studies with therapy-resistant patients | Patients on mexiletine | Age range (years) | Type of patients (if reported) | Mexiletine dose range | Evaluable patients | Studies that show >50% reduction | Number of patients meeting the cut-off | ||||

| Pre-mature ventricular contractions | ||||||||||||||

| 619,24–83 | Non-randomized | 61 | 7 days–84 months | 13 | 2369 | 0.42–88 | Ischaemic | 814 | 200–1500 | mg/day | 1834 patients in pre-post design 137 patients on mexiletine vs. 152 control patients |

27/38 studiesa24–32,35–37,45,46,49,52–56,58,65,68,70,74,81,82/24–32,34–37,40,41,44–47,49,50,52–56,58–60,65,68,70,71,73,74,77,81,82 | 23 studies work with a cut-off9,33,38,39,42,43,48,51,57,61–64,66,67,69,72,75,76,78–80,83 | |

| Randomized | 0 | Non-ischaemic | 321 | Cut-off (#studies) | #pt that meet cut-off/#evaluable pt | |||||||||

| 50–59% (7) | 95/175 (54%) | |||||||||||||

| Arrhythmia syndrome | 1 | 1–15 | mg/kg/day | 70–79% (12) | 282/455 (62%) | |||||||||

| 80–89% (3) | 24/39 (62%) | |||||||||||||

| Other | 377 | >90% (1) | 7/20 (35%) | |||||||||||

| Ventricular tachycardia | ||||||||||||||

| 349,25,27,28,35,36,58,62,64–67,70,72,78,80–82,84–99 | Non-randomized | 34 | 0–70 months | 15 | 1803 | 16–87 | Ischaemic | 616 | 50–1500 | mg/day | 943 patients in pre-post design 167 patients on mexiletine vs. 172 control patients |

7/11 studiesa25,27,35,65,81,82,94/25,27,35,36,58,65,81,82,84,93,94 | 23 studies work with a cut-off9,28,62,64,66,67,70,72,78,80,85–92,95–99 | |

| Non-ischaemic | 124 | Cut-off (#studies) | #pt that meet cut-off/#evaluable pt | |||||||||||

| 75% (2) | 63/85 (74%) | |||||||||||||

| Randomized | 0 | Arrhythmia syndrome | 4 | 2–15 | mg/day/kg | |||||||||

| 100% (21) | 492/613 (80%) | |||||||||||||

| Other | 110 | |||||||||||||

| Ventricular fibrillation | ||||||||||||||

| 1235,67,78,80,90,91,93,99–103 | Non-randomized | 12 | 1–84 months | 4 | 870 | 1–79 | Ischaemic | 246 | 400–1200 | mg/day | 358 patients in pre-post design 137 patients on mexiletine vs. 147 control patients |

1/3 studiesa100/35,93,100 | 9 studies work with a cut-off67,78,80,90,91,99,101–103 | |

| Non-ischaemic | 34 | Cut-off (#studies) | #pt that meet cut-off/#evaluable pt | |||||||||||

| Arrhythmia syndrome | 40 | 6–8 | mg/day/kg | 100% (9) | 290/324 (90%) | |||||||||

| Randomized | 0 | Other | 44 | |||||||||||

Studies that report a percentage change or enabled us to calculate a percentage change.

Electrophysiological study parameters

Table 2 shows the study details and outcome for the studies evaluating the effect of mexiletine on VT/VF inducibility and electrophysiological parameters. Inducibility of ventricular arrhythmias was reported in 19 studies for VT, and 2 studies for VF. In 112/379 (30%) patients, non-inducibility was achieved for VT and in 11/17 (65%) for VF (Table 2). The range in relative change percentage after mexiletine for the VT cycle length was −17% to +27%. Ten (55%) studies comprising 119 patients showed a change in cycle length of >15% after mexiletine, and most of those studies, 9/10 (90%), comprising 89 patients, showed that this change was an increase in cycle length (Table 2). With regards to the ERP, 0 (0%) of the 10 studies (n = 151 patients) showed a change of >15%. The effect ranged from −11% to + 8% (Table 2).

Table 2.

The effects of mexiletine on electrophysiological study parameters

| Electrophysiology studies | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inducibility studies | |||||||||||

| Publications, n (%) | Study design | Studies with therapy-resistant patients | Patients on mexiletine | Age range (years) | Type of patients (if reported) | Mexiletine dose range | Evaluable patients | Number of patients with non-inducibility | |||

| VT inducibility | |||||||||||

| 1973,81,91,97,104–117 | Non-randomized | 19 | 12 | 432 | 16–79 | Ischaemic | 229 | 125−2400 | mg/day | 379 patients in pre-post design | 112 (30%) |

| Non-ischaemic | 53 | ||||||||||

| Randomized | 0 | Arrhythmia syndrome | 0 | NA | mg/day/kg | ||||||

| Other | 8 | ||||||||||

| VF inducibility | |||||||||||

| 291,116 | Non-randomized | 2 | 1 | 35 | 60a | Ischaemic | 15 | 800−1200 | mg/day | 17 patients in pre-post design | 11 (65%) |

| Non-ischaemic | 20 | ||||||||||

| Randomized | 0 | Arrhythmia syndrome | 0 | NA | mg/day/kg | ||||||

| Other | 0 | ||||||||||

| Electrophysiology study parameters | |||||||||||

| Publications, n (%) | Study design | Studies with therapy-resistant patients | Patients on mexiletine | Age range | Type of patients | Mexiletine dose range | Evaluable patients | Studies with >15% change | |||

| Cycle length | |||||||||||

| 1873,81,87,97,105,106,108–110,113,115,117–123 | Non-randomized | 18 | 18 | 409 | 16–79 | Ischaemic | 179 | 125−2400 | mg/day | 376 patients in pre-post design | 10/18 Range of the change: −17% to +27%. Only one study showed a decrease of >15% |

| Non-ischaemic | 50 | ||||||||||

| Randomized | 0 | Arrhythmia syndrome | 0 | NA | mg/day/kg | ||||||

| Other | 7 | ||||||||||

| Effective refractory period | |||||||||||

| 1073,87,108–110,117,119,120,123,124 | Non-randomized | 10 | 6 | 178 | 5–79 | Ischaemic | 95 | 125−1200 | mg/day | 151 patients in pre-post design | 0/10 Range of the change: −11% to +8% |

| Non-ischaemic | 25 | ||||||||||

| Randomized | 0 | Arrhythmia syndrome | 0 | NA | mg/day/kg | ||||||

| Other | 3 | ||||||||||

NA, not applicable; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Mean age based on one study, and the age is not reported in the other study.

Electrocardiographic parameters

Table 3 shows the electrocardiographic effects of mexiletine in patients without a primary arrhythmia syndrome and in Table 4, the results are presented for the patients with a primary arrhythmia syndrome. The electrocardiographic effects of mexiletine in patients without primary arrhythmia syndrome showed that the effects of mexiletine on electrocardiographic parameters were small. Only 1 study out of 16 (6%, 5 of 329 patients) showed a change of >15% on heart rate (increase). For the QRS-duration (n = 21 studies, 536 patients) and the QTc (n = 16 studies, 439 patients), no effects >15% were observed. The range in relative change for the heart rate, QRS-duration, and the QTc were between −14% and +16% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Electrocardiographic effects of mexiletine in patients without primary arrhythmia syndromes

| Electrocardiographic studies | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publications, n (%) | Study design | Follow-up range | Studies with therapy-resistant patients | Patients on mexiletine | Age range (years) | Type of patients (if reported) | Mexiletine dose range | Evaluable patients | Studies that show >15% change | |||

| Heart rate | ||||||||||||

| 1624,31,37,38,45,49,55,62,66,71,74,88,124–127 | Non-randomized | 16 | 2 days–12 months | 7 | 449 | 5–83 | Ischaemic | 181 | 300–1200 | mg/day | 360 patients in pre-post design 9 patients on mexiletine vs. 26 control patients |

1125/16 Range of the change: −14% to +16% |

| Randomized | 0 | Non-ischaemic | 82 | |||||||||

| 4–24 | mg/day/kg | |||||||||||

| Other | 117 | |||||||||||

| QRS-duration | ||||||||||||

| 2126,31,37,45,46,55,58,61,62,64,65,74,76,82,87,88,108,110,119,120,128 | Non-randomized | 21 | 2 days–36 months | 9 | 647 | 21–87 | Ischaemic | 316 | 125–1500 | mg/day | 536 patients in pre-post design | 0/21 Range of the change: −4% to +7% |

| Non-ischaemic | 90 | |||||||||||

| Randomized | 0 | 7 | mg/day/kg | |||||||||

| Other | 98 | |||||||||||

| QTc | ||||||||||||

| 1626,37,45,55,61,62,64,65,68,73,74,82,87,88,110,117 | Non-randomized | 16 | 0.1–36 months | 7 | 557 | 18–87 | Ischaemic | 235 | 200–1200 | mg/day | 439 patients in pre-post design | 0/16 Range of the change: −5% to +2% |

| Non-ischaemic | 92 | |||||||||||

| NA | mg/day/kg | |||||||||||

| Randomized | 0 | Other | 112 | |||||||||

NA, not applicable.

Table 4.

Electrocardiographic effects of mexiletine in patients with primary arrhythmia syndromes

| Electrocardiographic studies | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publications, n (%) | Study design | Follow-up range | Studies with therapy-resistant patients | Patients on mexiletine | Age range (years) | Type of patients | Mexiletine dose range | Evaluable patients | Studies that show >15% change | |||

| Heart rate | ||||||||||||

| 598,102,128–130 | Non-randomized | 5 | 12–84 months | 0 | 50 | 1–63 | LQTS | 38 | NA | mg/day | 34 patients in pre-post design | 0/5 Range of the change: −7% to +6% |

| Randomized | 0 | CPVT | 0 | |||||||||

| Brugada | 12 | 2–42 | mg/day/kg | |||||||||

| QRS-duration 1128 | ||||||||||||

| Non-randomized | 1 | Mean follow-up 0.02 days | 0 | 12 | 27–63 | LQTS | 0 | NA | mg/day | 12 patients in pre-post design | 0/1 Mean change: +1.4% |

|

| CPVT | 0 | |||||||||||

| Randomized | 0 | Brugada | 12 | 2 | mg/day/kg | |||||||

| QTc | ||||||||||||

| 1198,100,102,128–135 | Non-randomized | 11 | 0.69–84 months | 0 | 115 | 0–64 | LQTS | 103 | 150–600 | mg/day | 90 patients in pre-post design | 3129–131/11 Range of the change: −19% to −1.3% |

| CPVT | 0 | |||||||||||

| Brugada | 12 | 2–42 | mg/day/kg | |||||||||

| Randomized | 0 | |||||||||||

CPVT, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; LQTS, long QT syndrome; NA, not applicable.

Patients with primary arrhythmia syndromes

In patients with a primary arrhythmia syndrome, mostly patients with LQTS (Table 4), the results for heart rate (n = 5 studies, n = 34 patients) and QRS-duration (n = 1 study, n = 12 patients) were similar (range of relative change −7% to +6%). In contrast, all studies reporting on QTc showed QTc shortening (n = 90 evaluable patients). Indeed, 3 (27.3%) of the 11 studies (22 of 90 evaluable patients) in LQTS patients report a relative decrease of >15% after mexiletine.129–131 Most of the evaluable LQTS patients were patients with type 3 (n = 64, 82%), followed by type 2 (n = 11, 14%), a combination LQT1/2 or LQT2/3 (n = 2, 3%) and type 8 (n = 1, 1%).

Safety and survival data

In 173 (78%) studies, safety is reported in total evaluating 7379 (82%) patients.9,10,24,26,27,29–77,84–97,100,103–110,118,124–126,127,128–130,132,133,136–222 Survival is reported in 151 studies (68%).9,10,25–32,35,40,43,46–50,52–63,66–71,73–80,84–87,89,91–98,100–113,119–126,128,130–139,142–145,148–159,161,162,164,165,169,171–173,175–177,181–184,188,190–194,196,199–201,204,207,208,211,212,214–217,220–229

Adverse events

In total, adverse events are reported in 128 (58%) of the studies. For the 589 adverse events reported, in 512 (86.9%), the number of patients with adverse events was specified resulting in a total of 4037 evaluable patients. Table 5 shows the incidences of adverse events. The most frequently reported organ system with adverse events was the gastrointestinal tract (33%). Gastrointestinal pain was reported in 27% of the patients, gastrointestinal discomfort/distress was reported in 19%, as was nausea (19%). Adverse events concerning the nervous system were also frequently reported (31%), and in 17% of the patients, a tremor occurred. Psychiatric adverse events were reported in 12% of the patients with insomnia most frequently reported (20%).

Table 5.

Overview of the adverse events

| # patients with event/number of patients in the studies reporting the event | |

|---|---|

| Adverse events were specified for a total of 4037 patients | |

| Gastrointestinal | |

| 1348 patients with this type of event (33%) | |

| Nausea | 462/2475 (19%) |

| Other (e.g. discomfort/distress or not further specified) | 341/1833 (19%) |

| Gastrointestinal pain | 88/329 (27%) |

| Constipation | 150/1043 (14%) |

| Diarrhoea | 100/1259 (8%) |

| Nervous system disorders | |

| 1267 patients with this type of event (31%) | |

| Tremor | 414/2485 (17%) |

| Other (e.g. coordination difficulties or not further specified) | 131/1002 (13%) |

| Dizziness | 293/2368 (12%) |

| Headache | 165/1644 (10%) |

| Paraesthesia | 111/1373 (8%) |

| Psychiatric disorders | |

| 475 patients with this type of event (12%) | |

| Insomnia | 291/1457 (20%) |

| Depression | 67/689 (10%) |

| Other (e.g. anxiety, nervousness, mood changes, nightmares) | 80/1225 (7%) |

| Confusion | 26/470 (6%) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | |

| 175 patients with this type of event (4%) | |

| Generalized muscle weakness | 171/912 (19%) |

| Joint effusion | 1/32 (3%) |

| Cardiac disorders | |

| 144 patients with this type of event (4%) | |

| Sinus bradycardia | 36/388 (9%) |

| Heart failure | 29/533 (5%) |

| Chest pain—cardiac | 10/246 (4%) |

The organ systems and adverse events with ≥3% incidences are presented.

Left and right ventricular ejection fraction

Only 15 (7%) of the studies (n = 476 patients) report on effects of mexiletine on cardiac function.49,54,57,58,62,65,66,97,125,126,139,155,180,181,189 In all of the studies reporting on left ventricular ejection fraction, 14 (93.3%) of the studies (475 of 476 patients) showed no negative effects of mexiletine on left ventricular ejection fraction.49,54,57,58,62,65,66,97,125,126,155,180,181,189 Three (20%) studies comprising 36 patients reported on right ventricular ejection fraction, and none of these studies demonstrated a decrease in right ventricular ejection fraction.66,125,126

Drug–drug interactions

Nine studies (n = 23 patients) report on mexiletine interacting with other drugs.95,150,158,182,183,186,216,221,222 The majority [n = 5 (56%) studies, 7 (30%) patients] of those studies report an interaction with theophylline.95,158,182,183,216 Clearance of theophylline is reduced as a consequence of CYP1A2 inhibition by mexiletine, which results in increased (possibly toxic) theophylline blood levels.

Worsening of arrhythmias

In 40 (18%) studies, worsening or not worsening of arrhythmias is actively mentioned.27,31,34,38,39,41,50,54,55,57,58,60,62,64,68,75,76,85,87,90,106,118,128,129,138,141,151,154,161,164,166,174,175,183,201,207–209,213,218 In total, in this subset of 40 studies, in 137 of 2173 (6.3%) patients, the arrhythmia worsened after start of mexiletine.

Survival

Survival is reported in 151 (68%) studies evaluating 4801 patients on mexiletine. During varying follow-up durations ranging from 0.5 h to 167 months, 213 (4%) patients reportedly died during the study follow-up. In 13 studies reporting on both survival in patients with mexiletine and control patients, the proportions of survival are similar (90% in mexiletine vs. 92% in control patients).10,35,40,56,84,93,127,137,144,152,173,176,193

Discussion

In this systematic review, we present all the currently reported knowledge from 1973 onwards on the effectiveness and safety of mexiletine in patients at risk for (recurrent) ventricular arrhythmias. The data presented confirm that mexiletine is both effective and safe in patients at risk for (recurrent) ventricular arrhythmias. The evaluation of effectiveness is extensive and comprises of several aspects, including appreciable effects on PVC, VT and VF burden and on electrophysiological changes evaluated by electrophysiological studies and electrocardiography. Also with regards to our safety evaluation, to the best of our knowledge, such a detailed overview of adverse event incidences of mexiletine has not been previously reported. For example, we present incidences of several adverse events (e.g. diarrhoea and confusion) of which the incidences are currently marked as unknown.230 The presented safety data should be implemented into the product information of mexiletine to inform patients and prescribers adequately. Unfortunately, because of our broad study aim and the subsequent inclusion of studies with extremely heterogeneous designs and outcomes, it is not possible to compare the efficacy results of mexiletine with other anti-arrhythmic drugs such as sotalol or amiodarone.231,232

The findings of this systematic review indicate that treatment of mexiletine should be part of the therapeutic cardiology arsenal, both in paediatric (LQTS) and adult cardiology. Accessibility should thus be guaranteed. However, accessibility has been jeopardized by the market authorization as an orphan drug of Namuscla. Remarkably, the contra-indications of Namuscla actually include ventricular tachyarrhythmias and previous myocardial infarction. However, as can be appreciated from its previous anti-arrhythmic drug labelling, from the international guidelines on the treatment and prevention of VT/VF,1,11 and from our results section, mexiletine can be an effective and safe choice for the treatment and prevention of VT and VF. Furthermore, these results are mostly driven by patients with (post-)ischaemic heart disease as mexiletine was most frequently prescribed in this patient category (72%). Possibly, the indication for non-dystrophic myotonia would have been complicated by potential pro-arrhythmic effects, which is, of course, intrinsically a part of every anti-arrhythmic drug. The lack of new data may have led to declaring a contra-indication for cardiology patients whose lives are threatened by VT/VF. Importantly, labelling a contra-indication for a previous indication that is still recommended in the guidelines could have important medico-legal consequences for off-label prescription. This could further limit mexiletine use in patients who could benefit. In addition, as per European regulation, the authorization of Namuscla as an orphan drug for the neurological indication non-dystrophic myotonia granted a 10-year market exclusivity and prohibits import of mexiletine for VT/VF. Upon introduction of Namuscla, the price was raised up to >30-fold in comparison with imports which in turn led to reimbursement issues for both the cardiac and neurological indication.6,15,16

Practical suggestion

The current use of mexiletine is constrained to (high risk and/or therapy refractory) VT/VF, which is also supported by the results of our systematic review. However, as shown, mexiletine also appears to be very successful in suppressing PVCs. Hence, mexiletine may have a position in patients without complex ventricular arrhythmias who do not respond well to conventional therapy (be it side effects or inefficacy). Mexiletine also appears to be very effective in (paediatric) patients with LQTS. Therefore, we suggest the use of mexiletine in:

Patients at high risk for VT/VF who do not respond to conventional therapy

Patients without complex ventricular arrhythmias who do not respond to conventional therapy

Patients with LQTS (mainly Types 3 and 2) with ventricular arrhythmias or a high risk of ventricular arrhythmias (e.g. very long QTc)

Limitations

From 1973 onwards, 221 publications with original data regarding the efficacy and safety of mexiletine in patients with (recurrent) ventricular arrhythmias were identified. Over time, inevitably, the quality of conducting and reporting scientific research improved.233 For the efficacy data, studies with a high risk of bias were therefore excluded. Furthermore, in this review, we aimed to evaluate both the effectiveness and safety of all types of patients at risk for (recurrent) arrhythmias. As efficacy of mexiletine comprises of multiple relevant outcome measures (e.g. PVC reduction, or QTc reduction in patients with LQTS), included studies were different in methodology, follow-up duration, outcome measures, and also in the reporting of efficacy (e.g. cut-off % for efficacy) and of safety data. Therefore, a single estimate effect of mexiletine could not be calculated. Due to this heterogeneity, extracting data for standardized evaluation required modulation or interpretation of study data for some studies. Data were independently extracted by at least two members of the study team to prevent subjectivity. Also due to the large amount of data, in the body of the manuscript only a general overview of the results is presented. For more detailed results of individual studies, we refer to the supplementary excel file. This supplementary excel also allows the reader to select on specific study characteristics (e.g. follow-up duration). It is important to acknowledge that drug–drug studies not involving mexiletine treatment effectiveness or safety (i.e. healthy volunteer studies) are beyond the scope of this review. Consequently, evaluation of relevant drug–drug interactions, mainly involving the cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP1A2 and CYP2D6, is incomplete. Lastly, efforts were made to prevent double reporting of patients and outcome data in this systematic review; however, we cannot exclude that double reported data entered our results.

Conclusion

In this systematic review, we present all the currently available knowledge on the effectiveness and safety of the long-known anti-arrhythmic drug mexiletine in patients at risk for (recurrent) ventricular arrhythmias and based on the results, we conclude that mexiletine is both effective and safe. As the European accessibility of mexiletine has recently been critically endangered by its acceptance as an anti-myotonic drug, efforts should be undertaken to unchain mexiletine and assure its fair accessibility for both cardiology and neurology patients.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Martijn H van der Ree, Department of Clinical Cardiology, Heart Center, Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Cardiovascular Sciences, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Laura van Dussen, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 15, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Medicine for Society, Platform at Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Noa Rosenberg, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 15, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Medicine for Society, Platform at Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Nina Stolwijk, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 15, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Medicine for Society, Platform at Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Sibren van den Berg, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 15, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Medicine for Society, Platform at Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Vincent van der Wel, Medicine for Society, Platform at Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Bart A W Jacobs, Medicine for Society, Platform at Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Department of Pharmacy, Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 15, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Arthur A M Wilde, Department of Clinical Cardiology, Heart Center, Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Cardiovascular Sciences, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Carla E M Hollak, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 15, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Medicine for Society, Platform at Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Pieter G Postema, Department of Clinical Cardiology, Heart Center, Amsterdam UMC—University of Amsterdam, Cardiovascular Sciences, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Funding

This systematic review is performed as part of a larger project ‘platform Medicijn voor Maatschappij (platform Medicine for Society)’. This platform is financially supported by a grant from ‘de VriendenLoterij’, a National Lottery that distributes funds raised by this lottery for good causes primarily concerning health and welfare in The Netherlands. P.G.P. receives research funding from the Dutch Heart Foundation (grant 03-003-2021-T061).

Data availability

As stated in the method section: The study data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm Jet al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the Europe. Eur Heart J 2015;36:2793–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sénac J-B, Orléans P, Orléans L, Potier J, Robert J. Traité de la structure du coeur, de son action, et de ses maladies 1749.

- 3. Withering W. An account of the foxglove and some of its medical uses: with practical remarks on dropsy and other diseases. London 1785.

- 4. Lei M, Wu L, Terrar DA, Huang CL. Modernized classification of cardiac antiarrhythmic drugs. Circulation 2018;138:1879–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilde AAM, Langendijk P. Antiarrhythmic drugs, patients, and the pharmaceutical industry: value for patients, physicians, pharmacists or shareholders? Neth Heart J 2007;15:127–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Postema PG, Schwartz PJ, Arbelo E, Bannenberg WJ, Behr ER, Belhassen Bet al. Continued misuse of orphan drug legislation: a life-threatening risk for mexiletine. Eur Heart J 2020;41:614–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Viskin S, Antzelevitch C, Márquez MF, Belhassen B. Quinidine: a valuable medication joins the list of ‘endangered species’. Europace 2007;9:1105–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Viskin S, Wilde AA, Guevara-Valdivia ME, Daoulah A, Krahn AD, Zipes DPet al. Quinidine, a life-saving medication for Brugada syndrome, is inaccessible in many countries. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:2383–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Talbot RG, Nimmo J, Julian DG, Clark RA, Neilson JM, Prescott LF. Treatment of ventricular arrhythmias with mexiletine (Kö 1173). Lancet 1973;302:399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. International mexiletine and placebo antiarrhythmic coronary trial: I. Report on arrhythmia and other findings. Impact Research Group. J Am Coll Cardiol 1984;4:1148–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis ABet al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2018;138:e272–e391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Postema PG. About the different faces of mexiletine. Heart Rhythm 2020;17:1951–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stunnenberg BC, Raaphorst J, Groenewoud HM, Statland JM, Griggs RC, Woertman Wet al. Effect of mexiletine on muscle stiffness in patients with nondystrophic myotonia evaluated using aggregated N-of-1 trials. JAMA 2018;320:2344–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carroll IR, Kaplan KM, Mackey SC. Mexiletine therapy for chronic pain: survival analysis identifies factors predicting clinical success. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:321–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van den Berg S, van der Wel V, de Visser SJ, Stunnenberg BC, Timmers L, van der Ree MHet al. Cost-based price calculation of mexiletine for nondystrophic myotonia. Value Health 2021;24:925–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Luzzatto L, Hyry HI, Schieppati A, Costa E, Simoens S, Schaefer Fet al. Outrageous prices of orphan drugs: a call for collaboration. Lancet 2018;392:791–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CDet al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ;2021:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. Evid Based Med 2018;23:60–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan Met al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron Iet al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. EDC C. Castor Electronic Data Capture 2019.

- 23. Wilde AAM, Amin AS, Postema PG. Diagnosis, management and therapeutic strategies for congenital long QT syndrome. Heart 2022;108:332–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fracalossi C, Ziacchi V, Farisè F, Rossi A, Marino A, Lomanto Bet al. Mexiletine for the treatment of ventricular arrhythmias associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. G Ital Cardiol 1989;19:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garcia-Touchard A, Somers VK, Kara T, Nykodym J, Shamsuzzaman A, Lanfranchi Pet al. Ventricular ectopy during REM sleep: implications for nocturnal sudden cardiac death. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2007;4:284–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lui HK, Harris FJ, Chan MC, Lee G, Mason DT. Comparison of intravenous mexiletine and lidocaine for the treatment of ventricular arrhythmias. Am Heart J 1986;112:1153–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morganroth J. Comparative efficacy and safety of oral mexiletine and quinidine in benign or potentially lethal ventricular arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol 1987;60:1276–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Skwarski K, Sliwiński P, Górecka D, Zieliński J. The effects of mexiletine on cardiac arrhythmias in patients with cor pulmonale. Respiration 1989;56:235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Steen SN, Hughes EM, Sharon G, MacGregor TR. Efficacy of oral mexiletine therapy at a 12-h dosage interval. Chest 1990;97:358–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Trimarco B, Volpe M, Ricciardelli B, Sacca L, De Luca N, Rengo Fet al. Disopyramide and mexiletine: which is the agent of choice in the long term-oral treatment of lidocaine-responsive arrhythmias? Efficacy comparison in a randomized trial. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther 1980;248:251–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zehender M, Geibel A, Treese N, Hohnloser S, Meinertz T, Just H. Prediction of efficacy and tolerance of oral mexiletine by intravenous lidocaine application. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1988;44:389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Arakawa K, Doi Y, Hashiba K, Mitsuoka T, Yanaga T, Hata Yet al. Well-controlled comparative study of the clinical effectiveness of intravenous mexiletine and procainamide on ventricular premature contraction. Jpn Heart J 1984;25:357–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Assey ME, Hudson WM, Hanger KH, Miller SC. Comparative study of mexiletine and quinidine in the treatment of ventricular ectopia. South Med J 1985;78:565–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Breithardt G, Seipel L, Lersmacher J, Abendroth RR. Comparative study of the antiarrhythmic efficacy of mexiletine and disopyramide in patients with chronic ventricular arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1982;4:276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Campbell RW, Achuff SC, Pottage A, Murray A, Prescott LF, Julian DG. Mexiletine in the prophylaxis of ventricular arrhythmias during acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1979;1:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Campbell RW, Dolder MA, Prescott LF, Talbot RG, Murray A, Julian DG. Comparison of procainamide and mexiletine in prevention of ventricular arrhythmias after acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 1975;305:1257–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Capucci A, Di Pasquale G, Boriani G, Carini G, Balducelli M, Frabetti Let al. A double-blind crossover comparison of flecainide and slow-release mexiletine in the treatment of stable premature ventricular complexes. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 1991;11:23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chaudron JM, Luwaert RJ. Effectiveness of mexiletine in ventricular arrhythmias. Acta Cardiol 1985;40:589–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fenster PE, Hanson CD. Mexiletine and quinidine in ventricular ectopy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1983;34:136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Haedo AH, Chiale PA, Ieri JD, Lázzari JO, Elizari MV, Rosenbaum MB. Comparative antiarrhythmic efficacy of verapamil, 17-monochloracetylajmaline, mexiletine and amiodarone in patients with severe chagasic myocarditis: relation with the underlying arrhythmogenic mechanisms. J Am Coll Cardiol 1986;7:1114–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ino-Oka E, Takashima T. Comparison of clinical efficacy of disopyramide and mexiletine in treatment of premature ventricular complexes. Drug Investig 1989;1:53–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jewitt DE, Jackson G, McComish M. Comparative anti-arrhythmic efficacy of mexiletine, procainamide and tolamolol in patients with symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias. Postgrad Med J 1977;53:158–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kerin NZ, Aragon E, Marinescu G, Faitel K, Frumin H, Rubenfire M. Mexiletine. Long-term efficacy and side effect in patients with chronic drug-resistant potentially lethal ventricular arrhythmias. Arch Intern Med 1990;150:381–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Koch G, Lindström B. Efficacy of oral mexiletine in the prevention of exercise-induced ventricular ectopic activity. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1978;13:237–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Masotti G, Morettini A, Casolo GC, Ieri A, Zipoli A, Serneri GG. Efficacy of mexiletine in the medium-term treatment of ventricular arrhythmias. A randomized, double-blind, crossover trial against placebo in ambulatory patients. J Int Med Res 1984;12:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mehta J, Conti CR. Mexiletine, a new antiarrhythmic agent, for treatment of premature ventricular complexes. Am J Cardiol 1981;49:455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Meinertz T, Kasper W, Stengel E, Waldecker B, Löllgen H, Jähnchen Eet al. Comparison of the antiarrhythmic activity of mexiletine and lorcainide on ventricular arrhythmias. Z Kardiol 1982;71:35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Moak JP, Smith RT, Garson A Jr. Mexiletine: an effective antiarrhythmic drug for treatment of ventricular arrhythmias in congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1987;10:824–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morita H, Hirabayashi K, Nozaki S, Ohmori K, Yoshikawa K, Matsuo H. Chronic effect of oral mexiletine administration on left ventricular contractility in patients with congestive heart failure: a study based on mitral regurgitant flow velocity measured by continuous-wave Doppler echocardiography. J Clin Pharmacol 1995;35:478–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Myburgh DP, Goldman AP. The anti-arrhythmic efficacy of perhexiline maleate, disopyramide and mexiletine in ventricular ectopic activity. S Afr Med J 1978;54:1053–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nademanee K, Feld G, Hendrickson J, Intarachot V, Yale C, Heng MKet al. Mexiletine: double-blind comparison with procainamide in PVC suppression and open-label sequential comparison with amiodarone in life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. Am Heart J 1985;110:923–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nagasako S, Iwamoto K, Hayashibara M, Katagiri Y, Morioka S, Moriyama K. Utilization of salivary level monitoring of mexiletine in the therapy of arrhythmic patients. Jpn J Clin Pharmacol Therap 1993;24:425–31. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ohashi K, Ebihara A, Hashimoto T, Hosoda S, Kondo K, Oka T. Pharmacokinetics and the antiarrhythmic effect of mexiletine in patients with chronic ventricular arrhythmias. Arzneimittelforschung 1984;34:503–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Petrac D, Pintaric H, Trampuz L. Efficacy of mexiletine in the suppression of ventricular premature beats in patients with ischemic and nonischemic heart disease. Acta Clin Croat 1998;37:191–5. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Poggesi L, Scarti L, Ieri A, Lanzetta T, Grazzini M, Del Bene Pet al. Efficacy of mexiletine in chronic ventricular arrhythmias: a multicentre double-blind medium-term trial. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 1989;9:269–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pristautz H, Biffl H, Leitner W, Parsché P, Schmid P. Influence of an antiarrhythmic premedication on the development of premature ventricular contractions during fiberoptic gastroduodenoscopy. Endoscopy 1981;13:57–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ravid S, Lampert S, Graboys TB. Effect of the combination of low-dose mexiletine and metoprolol on ventricular arrhythmia. Clin Cardiol 1991;14:951–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rutledge JC, Harris F, Amsterdam EA. Clinical evaluation of oral mexiletine therapy in the treatment of ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985;6:780–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Saikawa T, Ito M, Nakagawa M, Shimoyama N, Hara M, Yonemochi Het al. Suppression of ventricular premature contractions continues after the washout of antiarrhythmic drugs. Jpn Circ J 1993;57:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Saikawa T, Nakagawa M, Takahashi N, Ishida S, Fujino T, Ito Met al. Mexiletine and disopyramide suppress ventricular premature contractions (VPC) irrespective of the relationship between the VPC and the underlying heart rate. Jpn Heart J 1992;33:665–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sakurada H, Motomiya T, Hiraoka M. Efficacy of disopyramide and mexiletine used alone or in combination in the treatment of ventricular premature beats. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1991;5:835–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sami M, Lisbona R. Mexiletine: long-term efficacy and hemodynamic actions in patients with ventricular arrhythmia. Can J Cardiol 1985;1:251–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sathyamurthy I, Krishnaswami S, Padmakumar P, Mao R. Comparative trial of mexiletine and lignocaine in the treatment of ventricular arrhythmias. Indian Heart J 1985;37:361–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Singh JB, Rasul AM, Shah A, Adams E, Flessas A, Kocot SL. Efficacy of mexiletine in chronic ventricular arrhythmias compared with quinidine: a single-blind, randomized trial. Am J Cardiol 1984;53:84–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Singh S, Klein R, Eisenberg B, Hughes E, Sh DP. Long-term effect of mexiletine on left ventricular function and relation to suppression of ventricular arrhythmia. Am J Cardiol 1990;66:1222–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Stein J, Podrid P, Lown B. Effects of oral mexiletine on left and right ventricular function. Am J Cardiol 1984;54:575–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Talbot RG, Julian DG, Prescott LF. Long-term treatment of ventricular arrhythmias with oral mexiletine. Am Heart J 1976;91:58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tanabe T. Combination antiarrhythmic treatment among class Ia, Ib, and II agents for ventricular arrhythmias. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1991;5:827–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tanabe T, Yoshikawa H, Furuya H, Goto Y. Therapeutic effectiveness and plasma levels of single or combination use of class I antiarrhythmic agents for ventricular arrhythmias. Jpn Circ J 1988;52:298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Upward JW, Holt DW, Jackson G. A study to compare the efficacy, plasma concentration profile and tolerability of conventional mexiletine and slow-release mexiletine. Eur Heart J 1984;5:247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Waleffe A, Kulbertus HE. The efficacy of intravenous mexiletine on ventricular ectopic activity. Acta Cardiol 1977;32:269–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wang RY, Lee PK, Wong KL, Chow MS. Mexiletine in the treatment of recurrent ventricular tachycardia. Prediction of long-term arrhythmia suppression from acute and short-term response. J Clin Pharmacol 1983;23:89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Waspe LE, Waxman HL, Buxton AE, Josephson ME. Mexiletine for control of drug-resistant ventricular tachycardia: clinical and electrophysiologic results in 44 patients. Am J Cardiol 1983;51:1175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yamauchi M, Watanabe E, Yasui K, Takeuchi H, Terasawa T, Sawada Ket al. Prevention of ventricular extrasystole by mexiletine in patients with normal QT intervals is associated with a reduction of transmural dispersion of repolarization. Int J Cardiol 2005;103:92–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zaliunas R, Zabiela P, Slapikas R, Vainoras A, Pentiokiniene D, Levisauskiene Ret al. Signal-averaged ECG in prediction of the short-term suppression of ventricular premature beats by mexiletine. Int J Cardiol 1994;46:243–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zaliunas R, Zabiela P, Slapikas R, Vainoras A, Pentiokiniene D, Levisauskiene Ret al. The effects of intravenous mexiletine on spectra of the signal-averaged ECG. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1994;17:2187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zou JG, Zhang J, Jia ZH, Cao KJ. Evaluation of the traditional Chinese Medicine Shensongyangxin capsule on treating premature ventricular contractions: a randomized, double-blind, controlled multicenter trial. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011;124:76–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Priori SG, Bonazzi O, Facchini M, Varisco T, Schwartz PJ. Antiarrhythmic efficacy of penticainide and comparison with disopyramide, flecainide, propafenone and mexiletine by acute oral drug testing. Am J Cardiol 1987;60:1068–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tanabe T, Yoshikawa H, Tagawa R, Furuya H, Ide M, Goto Y. Evaluation of antiarrhythmic drug efficacy using Holter electrocardiographic technique. Jpn Circ J 1985;49:337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Thomas MG, Giles TD. Mexiletine: long-term follow-up of a patient with prolonged QT interval and quinidine-induced torsades de pointes. South Med J 1985;78:205–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kim SG, Seiden SW, Matos JA, Waspe LE, Fisher JD. Discordance between ambulatory monitoring and programmed stimulation in assessing efficacy of mexiletine in patients with ventricular tachycardia. Am Heart J 1986;112:14–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kim SG, Mercando AD, Tam S, Fisher JD. Combination of disopyramide and mexiletine for better tolerance and additive effects for treatment of ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989;13:659–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nakanishi T, Nishimura M, Kubota S, Hirabayashi M. Effects of antiarrhythmic agents on ventricular premature systoles, with special reference to the coupling interval. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 1990;48:623–31. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Deyell MW, Steinberg C, Doucette S, Parkash R, Nault I, Gray Cet al. Mexiletine or catheter ablation after amiodarone failure in the VANISH trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2018;29:603–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Fenster PE, Kern KB. Mexiletine in refractory ventricular arrhythmias. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1983;34:777–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hoffmann A, Schütz E, White R, Follath F, Burckhardt D. Suppression of high-grade ventricular ectopic activity by antiarrhythmic drug treatment as a marker for survival in patients with chronic coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 1984;107:1103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mendes L, Podrid PJ, Fuchs T, Franklin S. Role of combination drug therapy with a class IC antiarrhythmic agent and mexiletine for ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;17:1396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Otuki S, Hasegawa K, Watanabe H, Katsuumi G, Yagihara N, Iijima Ket al. The effects of pure potassium channel blocker nifekalant and sodium channel blocker mexiletine on malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias. J Electrocardiol 2017;50:277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Park J, Kim SK, Pak HN. A case of long QT syndrome type 3 aggravated by beta-blockers and alleviated by mexiletine: the role of epinephrine provocation test. Yonsei Med J 2013;54:529–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Podrid PJ, Lown B. Mexiletine for ventricular arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol 1981;47:895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Poole JE, Werner JA, Bardy GH, Graham EL, Pulaski WP, Fahrenbruch CEet al. Intolerance and ineffectiveness of mexiletine in patients with serious ventricular arrhythmias. Am Heart J 1986;112:322–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Santinelli V, Chiariello M, Stanislao M, Condorelli M. Intravenous mexiletine in management of lidocaine-resistant ventricular tachycardia. Am Heart J 1983;105:680–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Smyllie HC, Doar JW, Head CD, Leggett RJ. A trial of intravenous and oral mexiletine in acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1984;26:537–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Sobiech M, Lewandowski M, Zając D, Maciąg A, Syska Pet al. Efficacy and tolerability of mexiletine treatment in patients with recurrent ventricular tachyarrhythmias and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator shocks. Kardiol Pol 2017;75:1027–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Stanley R, Comer T, Taylor JL, Saliba D. Mexiletine-theophylline interaction. Am J Med 1989;86:733–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Stein J, Podrid PJ, Lampert S, Hirsowitz G, Lown B. Long-term mexiletine for ventricular arrhythmia. Am Heart J 1984;107:1091–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Whitford EG, McGovern B, Schoenfeld MH, Garan H, Newell JB, McElroy Met al. Long-term efficacy of mexiletine alone and in combination with class Ia antiarrhythmic drugs for refractory ventricular arrhythmias. Am Heart J 1988;115:360–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Okuwaki H, Kato Y, Lin L, Nozaki Y, Takahashi-Igari M, Horigome H. Mexiletine infusion challenge test for neonatal long QT syndrome with 2:1 atrioventricular block. J Arrhythmia 2019;35:685–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Sharma PP, Ott P, Hartz V, Mason JW, Marcus FI. Risk factors for tachycardia events caused by antiarrhythmic drugs: experience from the ESVEM trial. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 1998;3:269–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Mazzanti A, Maragna R, Faragli A, Monteforte N, Bloise R, Memmi Met al. Gene-specific therapy with mexiletine reduces arrhythmic events in patients with long QT syndrome type 3. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1053–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ten Harkel AD, Witsenburg M, de Jong PL, Jordaens L, Wijman M, Wilde AA. Efficacy of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in a neonate with LQT3 associated arrhythmias. Europace 2005;7:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Ruan Y, Liu N, Bloise R, Napolitano C, Priori SG. Gating properties of SCN5A mutations and the response to mexiletine in long-QT syndrome type 3 patients. Circulation 2007;116:1137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Pottage A, Campbell RW, Fiddler GI, Godman MJ. Mexiletine therapy in a child with a chronic ventricular arrhythmia. Postgrad Med J 1977;53:137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Breithardt G, Seipel L, Abendroth RR. Comparison of the antiarrhythmic efficacy of disopyramide and mexiletine against stimulus-induced ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1981;3:1026–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Jordaens LJ, Tavernier R, Vanmeerhaeghe X, Robbens E, Clement DL. Combination of flecainide and mexiletine for the treatment of ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1990;13:1127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Palileo EV, Welch W, Hoff J, Strasberg B, Bauernfeind RA, Swiryn Set al. Lack of effectiveness of oral mexiletine in patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal sustained ventricular tachycardia. A study utilizing programmed stimulation. Am J Cardiol 1982;50:1075–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Raviele A, Di Pede F, Delise P, Piccolo E. Value of serial electropharmacological testing in managing patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1984;7:850–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Toivonen L, Kadish A, Morady F. A prospective comparison of class IA, B, and C antiarrhythmic agents in combination with amiodarone in patients with inducible, sustained ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 1991;84:101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Widerhorn J, Sager PT, Rahimtoola SH, Bhandari AK. The role of combination therapy with mexiletine and procainamide in patients with inducible sustained ventricular tachycardia refractory to intravenous procainamide. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1991;14:420–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Yeung-Lai-Wah JA, Murdock CJ, Boone J, Kerr CR. Propafenone-mexiletine combination for the treatment of sustained ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992;20:547–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Denniss AR, Ross DL, Cody DV, Russell PA, Young AA, Richards DAet al. Randomized controlled trial of prophylatic antiarrhythmic therapy in patients with inducible ventricular tachyarrhythmias after recent myocardial function. Eur Heart J 1988;9:746–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Gillis AM, Traboulsi M, Hii JTY, Wyse DG, Duff HJ, McDonald Met al. Antiarrhythmic drug effects on QT interval dispersion in patients undergoing electropharmacologic testing for ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 1998;81:588–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Ohira K, Niwano S, Furushima H, Taneda K, Chinushi M, Aizawa Y. The use of the block cycle length as a safe and efficient means of interrupting sustained ventricular tachycardia and its pharmacological modification. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1998;21:1686–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Rae AP, Greenspan AM, Spielman SR, Sokoloff NM, Webb CR, Kay HRet al. Antiarrhythmic drug efficacy for ventricular tachyarrhythmias associated with coronary artery disease as assessed by electrophysiologic studies. Am J Cardiol 1985;55:1494–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Miller SM, Martinez JJ, Deal BJ, Bauman JL, Scagliotti D, Hariman RJet al. Electrophysiologic testing of tocainide and mexiletine for ventricular tachycardia: assessment of the need to test both drugs. Am Heart J 1986;112:1114–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Rae AP, Spielman SR, Kutalek SP, Kay HR, Horowitz LN. Electrophysiologic assessment of antiarrhythmic drug efficacy for ventricular tachyarrhythmias associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 1987;59:291–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Bonavita GJ, Pires LA, Wagshal AB, Cuello C, Mittleman RS, Greene TOet al. Usefulness of oral quinidine-mexiletine combination therapy for sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias as assessed by programmed electrical stimulation when quinidine monotherapy has failed. Am Heart J 1994;127:847–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Manz M, Steinbeck G, Nitsch J, Luderitz B. Treatment of recurrent sustained ventricular tachycardia with mexiletine and disopyramide. Br Heart J 1983;49:222–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Abe A, Aizawa Y, Ma M. Does mexiletine have a preferential action (versus healthy myocardium) on the reentrant circuit of ventricular tachycardia? Heart Vessels 1997:235–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Aizawa Y, Abe A, Ohira K, Furushima H, Chinushi M, Fujita S. Preferential action of mexiletine on central common pathway of reentrant ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28:1759–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Ohkubo K, Watanabe I, Okumura Y, Ashino S, Kofune M, Nagashima Ket al. Functional atrioventricular conduction block in an elderly patient with acquired long QT syndrome: elucidation of the mechanism of block. J Electrocardiol 2011;44:353–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Reiter MJ, Easley AR, Mann DE. Efficacy of class Ib (lidocaine-like) antiarrhythmic agents for prevention of sustained ventricular tachycardia secondary to coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1987;59:1319–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Rosenheck S, Schmaltz S, Kadish AH, Summitt J, Morady F. The effect of quinidine and mexiletine on the adaptation of ventricular refractoriness to an increase in rate. Am Heart J 1991;121:512–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Shakibi JG, Moezzi B. Electrophysiologic effects of mexiletine in children. Jpn Heart J 1982;23:733–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Sheldon RS, Duff HJ, Mitchell LB, Wyse DG, Manyari DE. Effect of oral combination therapy with mexiletine and quinidine on left and right ventricular function. Am Heart J 1988;115:1030–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Takada Y, Isobe S, Okada M, Ando A, Nonokawa M, Inden Yet al. Effects of antiarrhythmic agents on left ventricular function during exercise in patients with chronic left ventricular dysfunction. Ann Nucl Med 2004;18:209–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Lombardi F, Torzillo D, Rone G, Dalla Vecchia L, Cappiello E. Autonomic effects of antiarrhythmic drugs and their importance. Eur Heart J 1992;13:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C, Suyama K, Kurita T, Taguchi A, Aihara Net al. Effect of sodium channel blockers on ST segment, QRS duration, and corrected QT interval in patients with Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2000;11:1320–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Funasako M, Aiba T, Ishibashi K, Nakajima I, Miyamoto K, Inoue Yet al. Pronounced shortening of QT interval with mexiletine infusion test in patients with type 3 congenital long QT syndrome. Circ J 2016;80:340–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Chang CC, Acharfi S, Wu MH, Chiang FT, Wang JK, Sung TCet al. A novel SCN5A mutation manifests as a malignant form of long QT syndrome with perinatal onset of tachycardia/bradycardia. Cardiovasc Res 2004;64:268–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Locati EH, Napolitano C, Cantu F, Towbin JAet al. Long QT syndrome patients with mutations of the SCN5A and HERG genes have differential responses to Na+ channel blockade and to increases in heart rate: implications for gene-specific therapy. Circulation 1995;92:3381–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Bos JM, Crotti L, Rohatgi RK, Castelletti S, Dagradi F, Schwartz PJet al. Mexiletine shortens the QT interval in patients with potassium channel-mediated type 2 long QT syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2019;12:e007280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Windle JR, Geletka RC, Moss AJ, Zareba W, Atkins DL. Normalization of ventricular repolarization with flecainide in long QT syndrome patients with SCN5A:DeltaKPQ mutation. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2001;6:153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Fujisawa T, Aizawa Y, Katsumata Y, Kimura K, Hashimoto K, Yamashita Tet al. Mexiletine shortens the QT interval in a pedigree of KCNH2 related long QT syndrome. J Arrhythmia 2019;36:193–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Zhu W, Mazzanti A, Voelker TL, Hou P, Moreno JD, Angsutararux Pet al. Predicting patient response to the antiarrhythmic mexiletine based on genetic variation: personalized medicine for long QT syndrome. Circ Res 2019;124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Abinader EG, Cooper M. Mexiletine. Use in control of chronic drug-resistant ventricular arrhythmia. JAMA 1979;242:337–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Achuff SC, Pottage A, Prescott L, Campbell RW, Murray A, Julian DG. Mexiletine in the prevention of ventricular arrhythmias in acute myocardial infarction. Postgrad Med J 1977;53:163–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Aguglia F, Gnecchi M, De Marzio P. Lidocaine, mexiletine and propafenone in the treatment of arrhythmias complicating myocardial infarction. A case report. Int J Cardiol 1985;7:303–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Ballas SL, Baughman KL, Griffith LSC, Veltri EP. Mexiletine-associated left ventricular dysfunction: a case study. Maryland Med J 1991;40:519–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Bell JA, Thomas JM, Isaacson JR, Snell NJ, Holt DW. A trial of prophylactic mexiletine in home coronary care. Br Heart J 1982;48:285–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Berchtold-Kanz E, Schwarz G, Hust M, Nitsche K, Just H. Increased incidence of side effects after encainide: a newly developed antiarrhythmic drug. Clin Cardiol 1984;7:493–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Bero CJ, Rihn TL. Possible association of pulmonary fibrosis with mexiletine. DICP Ann Pharmacother 1991;25:1329–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Boyle DM, Barber JM, Chapman C, Khalid I, Kinney CD, McIlmoyle ELet al. Comparison of the plasma concentrations and efficacy of mexiletine and of a slow-release preparation of mexiletine in patients admitted to a coronary care unit. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1981;4:174–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Bury RW, Hale G, Higginbotham M, Mashford ML. Zuidl. Mexiletine vs. lignocaine in the management of ventricular arrhythmias after open-heart surgery. Med J Aust 1982;1:265–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Cady WJ, Wilson CS, Chambers WA, Miles RR, Holcslaw TL, Forker AD. Mexiletine in the treatment of refractory ventricular arrhythmias: a report of five cases. Am Heart J 1980;99:181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Campbell NP, Chaturvedi NC, Shanks RG, Kelly JG, Strong JE, Adgey AA. The development of mexiletine in the management of ventricular dysrhythmias. Postgrad Med J 1977;53:114–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Campbell NP, Kelly JG, Shanks RG, Chaturvedi NC, Strong JE, Pantridge JF. Mexiletine (Kö 1173) in the management of ventricular dysrhythmias. Lancet 1973;302:404–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Campbell NP, Pantridge JF, Adgey AA. Long-term oral antiarrhythmic therapy with mexiletine. Br Heart J 1978;40:796–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Campbell RW, Julian DG, Talbot RG, Prescott LF. Long term treatment of ventricular arrhythmias with oral mexiletine. Postgrad Med J 1977;53:146–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Christie JM, Valdes C, Markowsky SJ. Neurotoxicity of lidocaine combined with mexiletine. Anesth Analg 1993;77:1291–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Cocco G, Strozzi C, Chu D, Pansini R. Torsades de pointes as a manifestation of mexiletine toxicity. Am Heart J 1980;100:878–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Datta-Chaudhari ML, O'Brien TD. Prophylactic use of mexiletine in the elderly with acute myocardial infarction. J Assoc Physicians India 1990;38:144–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. De Ambroggi G, Ali H, Cappato R, Sansone VA, De Ambroggi L. A 10-year follow-up of a patient affected by myotonic dystrophy type 1 with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implanted for secondary prevention. J Cardiovasc Med 2020;21:150–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. DiMarco JP, Garan H, Ruskin JN. Mexiletine for refractory-ventricular arrhythmias: results using serial electrophysiologic testing. Am J Cardiol 1980;47:131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Duff HJ, Mitchell LB, Manyari D, Wyse DG. Mexiletine-quinidine combination: electrophysiologic correlates of a favorable antiarrhythmic interaction in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol 1987;10:1149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Duff HJ, Roden D, Primm RK, Oates JA, Woosley RL. Mexiletine in the treatment of resistant ventricular arrhythmias: enhancement of efficacy and reduction of dose-related side effects by combination with quinidine. Circulation 1983;67:1124–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Duke M. Chronic mexiletine therapy for suppression of ventricular arrhythmias. Clin Cardiol 1988;11:132–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Ellison MJ, Lyman DJ, San Miguel E. Threefold increase in theophylline serum concentration after addition of mexiletine 2. Am J Emerg Med 1992;10:506–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Ermakov S, Hoffmayer KS, Gerstenfeld EP, Scheinman MM. Combination drug therapy for patients with intractable ventricular tachycardia associated with right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2014;37:90–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Facchini M, Bonazzi O, Priori SG, Varisco T, Zuanetti G, Schwartz PJ. Multiple comparison of several antiarrhythmic agents by acute oral drug testing in patients with chronic ventricular arrhythmias. Eur Heart J 1988;9:462–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Farré J G, Albo PS EA, Martí F, Martínez-Romero Pet al. Arrhythmogenic effects of antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with an old myocardial infarction and asymptomatic ventricular ectopic activity as studied by programmed electrical stimulation. Eur Heart J 1987;8:113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Ferro G, Chiariello M, Tari MG, Vigorito C, Ungaro B, Condorelli M. Intropic effects of several antiarrhythmic drugs. Jpn Heart J 1983;24:377–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Flaker GC, Madigan NP, Alpert MA, Moser SA. Mexiletine for recurring ventricular arrhythmias: assessment by long-term electrocardiographic recordings and sequential electrophysiologic studies. Am Heart J 1984;108:490–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Frank MJ, Watkins LO, Prisant LM, Smith MS, Russell SL, Abdulla AMet al. Mexiletine versus quinidine as first-line antiarrhythmia therapy: results from consecutive trials. J Clin Pharmacol 1991;31:222–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Frutos-Lopez M, Pedrote A, Acosta-Martinez J, Arana-Rueda E. Dramatic reduction of ventricular tachycardia burden after dronedarone plus mexiletine treatment in a patient refractory to hybrid ablation. Rev Port Cardiol 2017;39:171–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Fujimoto Y, Fukuki M, Hirokane Y, Kotake H, Mashiba H. Clinical study on coupling interval of ventricular premature contraction in patients with organic heart disease. Jpn Circ J 1991;55:1174–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]