ABSTRACT

Background

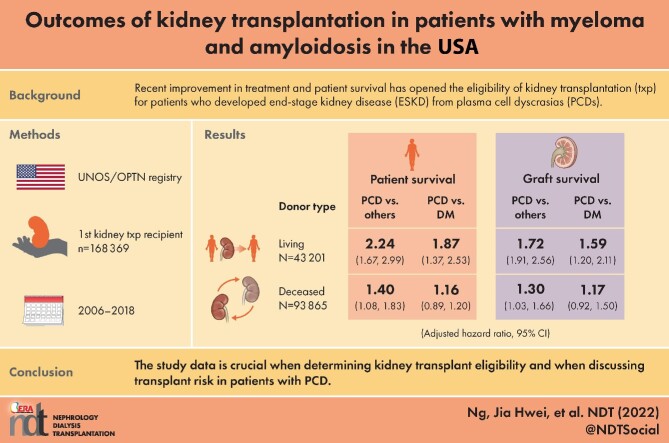

Recent improvement in treatment and patient survival has opened the eligibility of kidney transplantation to patients who developed end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) from plasma cell dyscrasias (PCDs). Data on clinical outcomes in this population are lacking.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of United Network for Organ Sharing/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network dataset (2006–2018) to compare patient and graft outcomes of kidney transplant recipients with ESKD due to PCD versus other causes.

Results

Among 168 369 adult first kidney transplant recipients, 0.22–0.43% per year had PCD as the cause of ESKD. The PCD group had worse survival than the non-PCD group for both living and deceased donor types {adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 2.24 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.67–2.99] and aHR 1.40 [95% CI 1.08–1.83], respectively}. The PCD group had worse survival than the diabetes group, but only among living donors [aHR 1.87 (95% CI 1.37–2.53) versus aHR 1.16 (95% CI 0.89–1.2)]. Graft survival in patients with PCD were worse than non-PCD in both living and deceased donors [aHR 1.72 (95% CI 1.91–2.56) and aHR 1.30 (95% CI 1.03–1.66)]. Patient and graft survival were worse in amyloidosis but not statistically different in multiple myeloma compared with the non-PCD group.

Conclusion

The study data are crucial when determining kidney transplant eligibility and when discussing transplant risks in patients with PCD.

Keywords: amyloidosis, MGRS, myeloma kidney, onconephrology, paraproteinemia, transplantation

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

KEY LEARNING POINTS.

What is already known about this subject?

Recent improvement in treatment and patient survival has opened the eligibility of kidney transplantation to patients who developed end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) from plasma cell dyscrasias (PCDs) including multiple myeloma, immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis and various forms of monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance.

Data on patient and graft outcomes for kidney transplant recipients with ESKD due to PCD compared with other causes were limited to one database study on amyloidosis, but the study did not looked at various forms of PCD nor stratified analyses to living and deceased donor types.

Kidneys are a scarce resource, thus a comparison of kidney transplantation outcomes of patients with ESKD due to PCD versus other causes is needed to guide future eligibility criteria for kidney transplantation among patients with PCD.

What this study adds?

The group with ESKD due to PCD had worse survival than those from other causes for both living and deceased donor types.

Those with ESKD due to PCD group had worse survival than those with diabetes as the cause of ESKD, but only among living donors.

When compared with ESKD due to other causes, patient and graft survival were worse in those with ESKD due to amyloidosis but not statistically different when compared with ESKD due to multiple myeloma.

What impact this may have on practice or policy?

The comparison of outcomes of patients with ESKD due to PCD in the context of other causes of ESKD will guide future eligibility criteria for patients with PCD to receive kidney transplantation, particularly at the level of transplant centers.

At the patient level, the study findings are particularly important when discussing kidney transplant risk with patients and potential donors.

INTRODUCTION

Despite recent advancements, kidney outcomes associated with plasma cell dyscrasias (PCDs) have not improved to the same degree as overall survival. PCDs are neoplastic disorders of plasma cells that are associated with an increased risk of death and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) [1]. Common PCDs that affect the kidney include multiple myeloma (MM), immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL amyloidosis) and various forms of monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance (MGRS) [2]. The treatment of MM has improved over the last decade [3–5]. The addition of monoclonal antibody therapy such as daratumumab has further improved progression-free survival and is estimated to improve overall survival beyond 8 years [6]. About 25% of patients with newly diagnosed MM have kidney involvement. Even with early treatment, up to 12% of patients with MM develop ESKD [7, 8], whereas kidney involvement occurs in 80% of patients with systemic AL amyloidosis [9–11]. Overall, patients with PCD who experience kidney complications have worse survival than those without [7, 12].

Compared with hemodialysis, kidney transplantation is a superior but scarce treatment option for ESKD [13–15]. Kidney transplant centers have begun to perform kidney transplantation for patients with ESKD due to PCD, but outcomes for these patients remain uncertain. Early evidence shows poor patient and graft survival for recipients with ESKD due to PCD, but the data have been limited to a few case reports and case series with small sample sizes [16–19]. A retrospective US registry–based study of kidney transplant recipients showed that patients with ESKD from amyloidosis had worse outcomes than those with ESKD from other causes but comparable to those with ESKD due to diabetes [20]. However, no similar study has been done to compare the outcomes across various forms of PCD nor to stratify their analyses to living and deceased donor types. Understanding the outcomes of survivors with malignancies after kidney transplantation is a research priority based on the 2020 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference on onconephrology [21].

To fill the knowledge gap, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS)/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) database. First, we described the frequency of kidney transplantation for patients who had ESKD due to various forms of PCD (MM, AL amyloidosis and MGRS). Second, we determined the absolute and relative outcomes of kidney transplant recipients who had ESKD due to PCD versus other causes. We also used ESKD due to diabetes as a second comparator group since diabetes is the most common cause of ESKD in the USA and is considered a high-risk transplant group [20, 22–24]. Third, we examined the causes of death of all kidney transplant recipients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and data source

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the dataset from the UNOS/OPTN. The UNOS/OPTN is a national registry reporting data on donors, recipients, waitlisted candidates and transplant recipients in the USA since 1 October 1987.

Study population and setting

We studied 168 369 adult (age ≥18 years) first kidney transplant recipients between 1 January 2006 and 30 June 2018 in the USA. Kidney transplant recipients with a body mass index (BMI) ≤15 or ≥45, multiorgan transplant and repeat kidney transplant were excluded. After analysis of our first objective, patients with a transplant after 1 January 2017 were excluded to ensure that all patients had a minimum 18-month follow-up time. Additionally, patients with any missing or unknown values on any demographic or clinical characteristics of interest were excluded, for a total sample size of 137 066. List-wise deletion was used to handle missing data because <2% of values were missing in all the variables.

Definitions and measurements

Outcomes

The primary outcome was patient survival time, defined as the time from transplantation to death [25]. Patients who were alive as of the last follow-up were censored and their time until the last follow-up was used.

Secondary outcomes included graft survival time, death-censored graft survival time [25], graft rejection and cause of death. Graft survival time was defined as the time from transplantation to graft failure. If the graft was still functioning at the last follow-up time, the patient was censored for graft failure. Patients who died with a functioning graft were considered as graft failure. Death-censored graft survival time was defined as the time from transplantation to graft failure. If the graft was still functioning or if the patient died with a functioning graft at the last follow-up time, the patient was considered censored for graft failure. Graft rejection was determined using the variable ‘patient treated for rejection during follow-up period [TRT_REJ]’. We determined the cause of death using the variable ‘cause of death [COD_KI]’ and recategorized them into the following: cardiocerebrovascular disease, malignancy, infection, others (hemorrhage, trauma, suicide, organ failure and drug-related) and unknown/missing.

Exposure

The primary exposure is PCD as the cause of ESKD. We use the variable ‘cause of kidney disease [DIAG_KI]’ to determine PCD. We included the following diagnostic codes as PCD: 3023 (multiple myeloma) and 3016 (amyloidosis). Additionally, we examined another variable ‘Other [DIAG_OSTXT_KI]’ to determine the cause of kidney failure by searching key terms related to PCD (see the Supplementary material).

Covariates

Covariates were chosen based on prior literature [26–28]. We included demographic and clinical characteristics from both the kidney transplant recipient and the kidney donor (see the Supplementry material).

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized for continuous variables using median and interquartile range [IQR; i.e. quartile 1 (Q1) quartile 3 (Q3)] and for categorical variables using frequency and percentage. Descriptive statistics were used to assess the association between demographic and clinical characteristics and the reason for kidney transplant (PCD, all other causes). Nominal categorical variables (e.g. sex) were compared across the reason for kidney transplant group using the chi-squared test and ordinal categorical variables (e.g. BMI category) and continuous variables were compared across the reason for kidney transplant group using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. The incidence rate of death was calculated by dividing the total number of deaths by the total person-time at risk. Cause of death was summarized descriptively using frequencies and percentages across each reason for ESKD. The median follow-up time was computed using the reverse Kaplan–Meier method using overall survival as the endpoint.

Cox proportional hazards regression was carried out to calculate unadjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for the outcomes of patient survival time, graft survival time, and death-censored graft survival time. For multivariable analyses, a univariable screen was first applied. All variables found to be associated with the main exposure, cause of ESKD (Table 2), were investigated as potential confounders. All potential confounders were included in a series of preliminary multivariable models looking at each outcome of interest. Backwards elimination was applied to each preliminary model to exclude variables not associated with the outcome. If the main exposure of interest was dropped during backwards elimination, it was added back in for the final model. All univariable and multivariable analyses were stratified by living and deceased donor types. This decision was made a priori because evidence shows that living donor kidney transplant recipients have better long-term patient and graft survival compared with deceased donor recipients [29, 30]. Logistic regression analyses were carried out in a similar manner for the outcome of rejection. Additional details of the univariable screen, multivariable analyses, sensitivity analyses and examples of confounder assessment are provided in the Supplementary material.

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between demographic/clinical characteristics and reason for kidney transplant (plasma cell dyscrasia, non-PCD) (N = 137 066)

| Characteristics | Plasma cell dyscrasia (n = 410) | Other (n = 136 656) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient | <.001 | ||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 59.00 (51.00–65.00) | 54.00 (43.00–63.00) | |

| Sex, n (%) | .86 | ||

| Male | 249 (60.73) | 83 594 (61.17) | |

| Female | 161 (39.27) | 53 062 (38.83) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| African American/Black | 24 (5.85) | 37 941 (27.76) | |

| Asian | 12 (2.93) | 8449 (6.18) | |

| Hispanic | 51 (12.44) | 21 642 (15.84) | |

| Other/multiracial | 4 (0.98) | 2643 (1.93) | |

| White | 319 (77.80) | 65 981 (48.28) | |

| BMI category, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| <25 | 158 (38.54) | 46 541 (34.06) | |

| 25–30 | 170 (41.46) | 41 383 (30.28) | |

| >30 | 82 (20.00) | 48 732 (35.66) | |

| HLA mismatch, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| ≤3 | 174 (42.44) | 44 920 (32.87) | |

| >3 | 236 (57.56) | 91 736 (67.13) | |

| HLA DR mismatch, n (%) | .052 | ||

| 0 | 87 (21.22) | 23 848 (17.45) | |

| 1 | 191 (46.59) | 64 375 (47.11) | |

| 2 | 132 (32.20) | 48 433 (35.44) | |

| History of cancer, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 141 (34.39) | 8962 (6.56) | |

| No | 269 (65.61) | 127 694 (93.44) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 17 (4.15) | 48 086 (35.19) | |

| No | 393 (95.85) | 88 570 (64.81) | |

| Prior dialysis, n (%) | .001 | ||

| Yes | 369 (90.00) | 115 087 (84.22) | |

| No | 41 (10.00) | 21 569 (15.78) | |

| Transplant year, n (%) | .01 | ||

| 2006–2008 | 87 (21.22) | 32 950 (24.11) | |

| 2009–2010 | 64 (15.61) | 24 108 (17.64) | |

| 2011–2013 | 103 (25.12) | 27 844 (27.69) | |

| 2014–2016 | 156 (38.05) | 41 754 (30.55) | |

| PRA, n (%) | .31 | ||

| ≤30 | 355 (86.59) | 115 875 (84.79) | |

| >30 | 55 (13.41) | 20 781 (15.21) | |

| Induction medication, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Depletinga | 223 (54.39) | 87 511 (64.04) | |

| Non-depletingb | 140 (34.15) | 29 339 (21.47) | |

| None | 47 (11.46) | 19 806 (14.49) | |

| Maintenance medication group 1, n (%) | .74 | ||

| Antimetabolitec | 382 (93.17) | 127 875 (93.57) | |

| No antimetabolite | 28 (6.83) | 8781 (6.43) | |

| Maintenance medication group 2, n (%) | .63 | ||

| CNI | 374 (91.22) | 125 702 (91.98) | |

| mTOR | 3 (0.73) | 933 (0.68) | |

| CNI + mTOR | 14 (3.41) | 3325 (2.43) | |

| None | 19 (4.63) | 6696 (4.90) | |

| Maintenance medication group 3, n (%) | .44 | ||

| Steroid | 388 (94.63) | 128 070 (93.72) | |

| None | 22 (5.37) | 8586 (6.28) | |

| Donor | |||

| Type, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Living | 206 (50.24) | 42 995 (31.46) | |

| Deceased | 204 (49.76) | 93 661 (68.54) | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 45.50 (33.00–55.00) | 42.00 (28.00–52.00) | <.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | .25 | ||

| Male | 206 (50.24) | 72 578 (53.11) | |

| Female | 204 (49.76) | 64 078 (46.89) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| African American/Black | 18 (4.39) | 17 831 (13.05) | |

| Asian | 7 (1.71) | 3993 (2.92) | |

| Hispanic | 44 (10.73) | 19 143 (14.01) | |

| Other/multiracial | 1 (0.24) | 2077 (1.52) | |

| White | 340 (82.93) | 93 612 (68.50) | |

| Height (cm), median (IQR) | 170.00 (162.60–176.00) | 170.18 (162.56–177.80) | .38 |

| Weight (kg), median (IQR) | 77.11 (66.68–89.81) | 78.00 (66.00–91.00) | .48 |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | .21 | ||

| Yes | 16 (3.90) | 7219 (5.28) | |

| No | 394 (96.10) | 129 437 (94.72) | |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | .07 | ||

| Yes | 71 (17.32) | 28 723 (21.02) | |

| No | 339 (82.68) | 107 933 (78.98) | |

| Hepatitis C, n (%) | .03 | ||

| Yes | 2 (0.49) | 2723 (1.99) | |

| No | 408 (99.51) | 133 933 (98.01) | |

| Cause of death (N = 93 661)d | .67 | ||

| Cerebrovascular | 65 (31.86) | 31 151 (33.26) | |

| Other | 139 (68.14) | 62 510 (66.74) | |

| Last serum creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 0.90 (0.70–1.10) | 0.90 (0.70–1.17) | .27 |

CNI, calcineurin inhibitors; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; PRA, panel reactive antibody.

Depleting agents: anti-thymocyte globulin, OKT3, alemtuzumab.

Non-depleting agents: anti-CD25 antibody.

Antimetabolite agents: mycophenolate, azathioprine, leflunomide.

Among N = 93 661 recipients with deceased donors.

The analysis for this article was generated using SAS Studio version 3.8 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and a P-value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Northwell Health Institutional Review Board determined that the study is not human subjects research under 45CFR46 (details in the Supplementary material).

RESULTS

Study population

Between 1 January 2006 and 30 June 2018, 168 369 patients received a first kidney transplant (Fig. 1). The proportion of kidney transplant recipients with ESKD due to PCD ranged from 0.22 to 0.43%, of which 0.15–0.28% had amyloidosis, 0.03–0.11% had MM and 0–0.05% had MGRS (Table 1). The final cohort used for the survival analysis was 137 066 patients (Fig. 1). Among these patients, 410 (0.30%) had ESKD from PCD (amyloidosis, 286; MM, 99; MGRS, 25) and 136 656 (99.70%) from other diagnoses. Table 2 describes the baseline characteristics of kidney transplant recipients by ESKD due to PCD versus other causes. Between the two groups, the PCD group was older and mostly White patients and had a lower BMI and a lower proportion of diabetes. The PCD group had a higher proportion with a history of cancer and a prior history of dialysis and a higher frequency of kidney transplantation during 2014–2016. They also had less human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch and had a lower proportion who received depleting induction medication. Neither group showed significant differences in maintenance immunosuppressants [antimetabolites, calcineurin inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors and steroids] (Table 2). The PCD group had a higher proportion of living donors; those donors were older, were mostly White and had a higher proportion without hepatitis C.

Figure 1:

Assembly of the study cohort for first-time kidney transplant recipients who had ESKD attributed to PCD or other causes. PRA, panel reactive antibody.

Table 1.

PCD (MM, amyloidosis, MGRS) as the cause of kidney transplant over time (N = 168 369)

| Year | Total transplants, N | All PCD transplants, n (%) | MM transplants, n (%) | Amyloidosis transplants, n (%) | MGRS transplants, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 12 210 | 39 (0.32) | 4 (0.03) | 29 (0.24) | 6 (0.05) |

| 2007 | 12 260 | 33 (0.27) | 6 (0.05) | 24 (0.20) | 3 (0.02) |

| 2008 | 12 565 | 28 (0.22) | 7 (0.06) | 19 (0.15) | 2 (0.02) |

| 2009 | 12 736 | 38 (0.30) | 6 (0.05) | 29 (0.23) | 3 (0.02) |

| 2010 | 13 022 | 33 (0.25) | 8 (0.06) | 25 (0.19) | 0 (0.00) |

| 2011 | 13 111 | 35 (0.27) | 14 (0.11) | 21 (0.16) | 0 (0.00) |

| 2012 | 12 745 | 40 (0.31) | 9 (0.07) | 29 (0.23) | 2 (0.02) |

| 2013 | 13 220 | 31 (0.23) | 8 (0.06) | 20 (0.15) | 3 (0.02) |

| 2014 | 13 501 | 39 (0.29) | 10 (0.07) | 29 (0.21) | 0 (0.00) |

| 2015 | 13 919 | 60 (0.43) | 16 (0.11) | 39 (0.28) | 5 (0.04) |

| 2016 | 14 976 | 58 (0.39) | 15 (0.10) | 40 (0.27) | 3 (0.02) |

| 2017 | 15 793 | 53 (0.34) | 14 (0.09) | 37 (0.23) | 2 (0.01) |

| 2018a | 8311 | 29 (0.35) | 10 (0.12) | 18 (0.22) | 1 (0.01) |

Data are from 1 January 2018 to 30 June 2018 only.

The median follow-up for patients with ESKD due to PCD and other causes was 4.85 years (IQR 4.04–5.20) and 4.99 years (IQR 4.98–4.99), respectively. Overall, there were 37.5 deaths/1000 person-years. Among living donor kidney transplant recipients, the incidence rate of death for patients with ESKD due to PCD, diabetes and other was 50.5, 39.2 and 15.8 deaths/1000 person-years, respectively (Table 3), whereas the incidence rate of death among deceased donor kidney transplant recipients for the PCD, diabetes and other groups was 64.3, 7.1 and 35.1 deaths/1000 person-years, respectively.

Table 3.

Incidence rate of death (deaths/100 person-years), stratified by donor type

| Outcome | Total deaths | Total person-years at risk for death | Incidence rate of death (deaths/1000 person-years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combined (living and deceased donor) | |||

| Plasma cell dyscrasia | 102 | 1784.7 | 57.2 |

| Diabetes | 10 736 | 174 197.5 | 61.6 |

| Other | 13 495 | 473 703.2 | 28.5 |

| Living donor | |||

| Plasma cell dyscrasia | 47 | 929.9 | 50.5 |

| Diabetes | 1942 | 49 603.5 | 39.2 |

| Other | 2570 | 162 493.6 | 15.8 |

| Deceased donor | |||

| Plasma cell dyscrasia | 55 | 854.8 | 64.3 |

| Diabetes | 8794 | 124 594.0 | 70.6 |

| Other | 10 925 | 311 209.7 | 35.1 |

Patient survival

Among living donor kidney transplant recipients, those with ESKD due to PCD had 2.47 times the rate of death compared with those from other causes of PCD [HR 2.47 (95% CI 1.85–3.29)] (Table 4, Fig. 2A). The rate of death of the PCD group remained higher than that of the non-PCD group after adjustment [adjusted HR (aHR) 2.24 (95% CI 1.67–2.99)]. Among deceased donor kidney transplant recipients, those with ESKD due to PCD had 1.40 times the rate of death after adjustement compared with those from other causes [aHR 1.40 (95% CI 1.08–1.83)] (Table 4, Fig. 2B). Patient survival, stratified by amyloidosis, MGRS, MM, diabetes and other causes is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Table 4.

| Living donor (n = 43 201) | Deceased donor (n = 93 865) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Patient survival | ||||||||

| PCD versus others |

2.47 (1.85–3.29) |

<.001 |

2.24 (1.67–2.99) |

<.001 |

1.43 (1.10–1.87) |

.01 |

1.40 (1.08–1.83) |

.01 |

| PCD versus diabetes |

1.33 (0.99–1.77) |

.06 |

1.87 (1.37–2.53) |

<.001 |

0.90 (0.69–1.18) |

.45 |

1.16 (0.89–1.52) |

.27 |

| Graft survival | ||||||||

| PCD versus others |

1.81 (1.38–2.36) |

<.001 |

1.72 (1.32–2.56) |

<.001 |

1.25 (0.99–1.59) |

.06 |

1.30 (1.03–1.66) |

.03 |

| PCD versus diabetes |

1.30 (0.99–1.70) |

.06 |

1.59 (1.20–2.11) |

.08 |

0.95 (0.75–1.21) |

.68 |

1.17 (0.92–1.50) |

.20 |

| Death-censored graft survival | ||||||||

| PCD versus others |

1.51 (1.02–2.24) |

.04 |

1.94 (1.31–2.88) |

.001 |

1.17 (0.83–1.65) |

.36 |

1.51 (1.07–2.13) |

0.02 |

| PCD versus diabetes |

1.52 (1.02–2.27) |

.04 |

1.97 (1.30–3.00) |

.001 |

1.14 (0.81–1.61) |

0.45 |

1.56 (1.10–2.20) |

0.02 |

| Outcomes | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Rejectionc | ||||||||

| PCD versus others |

1.39 (089–2.16) |

.15 |

1.46 (0.93–2.29) |

.10 |

0.94 (0.57–1.57) |

.82 |

1.09 (0.65–1.82) |

.75 |

| PCD versus diabetes |

1.58 (1.01–2.47) |

.05 |

1.64 (1.04–2.58) |

.04 |

1.04 (0.62–1.73) |

.90 |

1.13 (0.67–1.89) |

.65 |

| Rejection (sensitivity analysis)d | ||||||||

| PCD versus others |

1.34 (0.86–2.11) |

.20 |

1.45 (0.92–2.30) |

.11 |

0.94 (0.56–1.58) |

.82 |

1.09 (0.65–1.84) |

.75 |

| PCD versus diabetes |

1.51 (0.96–2.39) |

.07 |

1.60 (1.01–2.53) |

.05 |

1.00 (0.60–1.69) |

.99 |

1.09 (0.65–1.85) |

.74 |

aMain exposure categories: PCD (MM, amyloidosis, MGRS), other.

bMain exposure categories: PCD (MM, amyloidosis, MGRS), diabetes, other.

c32 731 patients with unknown rejection status combined as no rejection.

d32 731 patients with unknown rejection status were excluded.

Figure 2:

Patient survival, stratified by PCD (includes amyloidosis, MGRS and MM) and other (includes diabetes and all other). (A) Among living donor recipients. (B) Among deceased donor recipients.

The PCD group had a worse survival rate compared with the diabetes group, but only among recipients with a living donor, not among recipients with a deceased donor [aHR 1.87 (95% CI 1.37–2.53) versus aHR 1.16 (95% CI 0.89–1.20), respectively] (Table 5, Fig. 3). The causes of death for patients are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Table 5.

Association between kidney failure attributed to MM (versus other causes of ESKD) and clinical outcomesa,b (N = 137 041)

| Living donor | Deceased donor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Patient survival | ||||||||

| MM versus amyloidosis |

0.86 (0.42–1.79) |

.70 |

0.72 (0.35–1.50) |

.38 |

1.06 (0.58–1.95) |

.85 |

1.09 (0.59–2.00) |

.80 |

| MM versus other |

2.24 (1.16–4.30) |

.02 |

1.75 (0.91–3.38) |

.10 |

1.53 (0.91–2.58) |

.11 |

1.52 (0.90–2.57) |

.12 |

| Amyloidosis versus other |

2.59 (1.87–3.60) |

<.001 |

2.43 (1.75–3.38) |

<.001 |

1.44 (1.05–1.98) |

.02 |

1.40 (1.02–1.93) |

.04 |

| Graft survival | ||||||||

| MM versus amyloidosis |

0.81 (0.41–1.61) |

.54 |

0.63 (0.31–1.25) |

.18 |

0.96 (0.54–1.73) |

.90 |

0.85 (0.48–1.53) |

.59 |

| MM versus other |

1.56 (0.84–2.90) |

.16 |

1.23 (0.66–2.30) |

.51 |

1.20 (0.72–1.99) |

.48 |

1.15 (0.69–1.91) |

.59 |

| Amyloidosis versus other |

1.94 (1.43–2.62) |

<.001 |

1.98 (1.46–2.68) |

<.001 |

1.25 (0.93–1.66) |

.14 |

1.35 (1.01–1.80) |

.04 |

| Death censored graft survival | ||||||||

| MM versus amyloidosis |

0.89 (0.33–2.37) |

.81 |

0.79 (0.30–2.13) |

.64 |

1.32 (0.60–2.89) |

.49 |

1.17 (0.53–2.58) |

.69 |

| MM versus other |

1.40 (0.58–3.37) |

.45 |

1.67 (0.69–4.02) |

.25 |

1.36 (0.71–2.61) |

.36 |

1.66 (0.86–3.20) |

.13 |

| Amyloidosis versus other |

1.58 (1.01–2.48) |

.05 |

2.10 (1.34–3.31) |

.001 |

1.03 (0.66–1.60) |

.89 |

1.42 (0.91–2.20) |

.12 |

| Outcomes | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Rejectionc | ||||||||

| MM versus amyloidosis |

0.30 (0.07–1.36 |

.12 |

0.30 (0.07–1.35) |

.12 |

0.64 (0.17–2.36) |

.50 |

0.54 (0.15–2.01) |

.36 |

| MM versus other |

0.51 (0.13–2.12) |

.36 |

0.54 (0.13–2.24) |

.40 |

0.68 (0.21–2.18) |

.51 |

0.71 (0.22–2.89) |

.56 |

| Amyloidosis versus other |

1.69 (1.04–2.74) |

.03 |

1.80 (1.10–2.93) |

.02 |

1.06 (0.59–1.92) |

.84 |

1.31 (0.72–2.37) |

.38 |

| Rejection (sensitivity analysis)d | ||||||||

| MM versus amyloidosis |

0.27 (0.06–1.19) |

.08 |

0.26 (0.06–1.17) |

.08 |

0.68 (0.18–2.55) |

.56 |

0.56 (0.15–2.12) |

.39 |

| MM versus other |

0.45 (0.11–1.86) |

.27 |

0.49 (0.12–2.04) |

.33 |

0.72 (0.22–2.33) |

.58 |

0.74 (0.22–2.42) |

.61 |

| Amyloidosis versus other |

1.69 (1.04–2.77) |

.04 |

1.90 (1.15–3.13) |

.01 |

1.06 (0.58–1.93) |

.86 |

1.32 (0.72–2.42) |

.37 |

aMain exposure categories: MM, amyloidosis, other.

b25 patients with monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance were excluded.

c32 726 patients with unknown rejection status combined as no rejection.

d32 726 patients with unknown rejection status were excluded.

Figure 3:

Patient survival, stratified by PCD (includes amyloidosis, MGRS and MM), diabetes and other (includes all other). (A) Among living donor recipients. (B) Among deceased donor recipients.

Graft survival and death-censored graft survival

After adjustment, patients with ESKD due to PCD had a higher rate of graft loss compared with other causes, for both living and deceased donor types [aHR 1.72 (95% CI 1.32–2.56) and aHR 1.30 (95% CI 1.03–1.66), respectively] (Table 4). Similarly, the PCD group had a higher rate of death-censored graft loss compared with the other group for both living and deceased donor types [aHR 1.94 (95% CI 1.31–2.88) and aHR 1.51 (95% CI 1.07–2.13), respectively].

Graft rejection

There was no difference between ESKD due to PCD versus other causes in terms of graft rejection for both living and deceased donor transplants [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.46 (95% CI 0.93–2.29) and aOR 1.09 (95% CI 0.65–1.82), respectively] (Table 4). When comparing ESKD due to PCD versus diabetes, the PCD group had higher odds of graft rejection compared with the diabetes group among living donor types [aOR 1.64 (95% CI 1.04–2.58)], but not among deceased donor types [aOR 1.13 (95% CI 0.37–1.89)]. The findings were similar in the sensitivity analysis.

Patient and graft outcomes in multiple myeloma versus amyloidosis versus others

Patient survival for the group with ESKD due to MM was not statistically different compared with other causes for both living and deceased donor kidney transplant recipients [aHR 1.75 (95% CI 0.91–3.38) and aHR 1.52 (95% CI 0.90–2.57), respectively] (Table 5). However, the group with ESKD due to amyloidosis had a worse patient survival rate compared with others for both living and deceased donor kidney transplant recipients [aHR 2.43 (95% CI 1.75–3.38) and aHR 1.40 (95% CI 1.02–1.93), respectively].

Graft survival for the group with ESKD due to MM was not found to be statistically different compared with that of other causes [living donor aHR 1.23 (95% CI 0.66–2.30) deceased donor aHR 1.15 (95% CI 0.69–1.91)]. The group with ESKD due to amyloidosis had a higher rate of graft failure than the group of other causes [living donor aHR 1.98 (95% CI 1.46–2.68) aHR 1.35 (95% CI 1.01–1.80)].

The odds of graft rejection for the group with ESKD due to MM was not statistically different compared with others in both the living and deceased donor types [aOR 0.54 (95% CI 0.13–2.24 and aOR 0.71 (95% CI 0.22–2.89), respectively]. The adjusted odds of rejection for patients with ESKD due to amyloidosis was 1.80 times that of patients with other causes only among the living donor recipients [aOR 1.80 (95% CI 1.10–2.93)], but was not found to be different among deceased donor recipients [aOR 1.31 (95% CI 0.72–2.37)]. The findings were similar in the sensitivity analysis.

DISCUSSION

Data on patient and graft outcomes for kidney transplant recipients with ESKD due to PCD are limited. Using the UNOS/OPTN database, we found that the frequency of kidney transplantation for those with ESKD due to PCD over the past decade remains <0.50% of the total first-time kidney transplants. The overall incidence of death and patient survival for ESKD due to PCD is higher than for other causes. Additionally, the PCD group has worse patient survival compared with the diabetes group, but only among living donor kidney transplant recipients.

While the number of publications regarding kidney transplantation for patients with ESKD due to PCD has recently increased [16, 18, 19, 31], our study shows that this practice is still <0.50% of all first-time kidney transplants in the past decade. A major reason is the lack of consensus about criteria for determining suitability for kidney transplantation for patients with ESKD due to PCD [32]. In particular, kidney transplant and amyloidosis centers viewed the anticipated survival of patients as the most important factor when determining suitability for kidney transplant [32].

The incidence of death for transplant recipients who had ESKD due to PCD was 57.2/1000 person-years. Based on the United States Renal Data System Annual Data Report, the annual mortality rate of dialysis patients (all causes of ESRD) is 163.8/1000 person-years at risk (adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, primary cause of ESRD and patient dialysis vintage). With breakdown based on the cause of ESRD, the annual mortality ranges from 124.4 for glomerulonephritis (best), to 154.5 for hypertension and 196.9 for diabetes. Therefore we believe it is likely the survival of patients with PCD receiving kidney transplant is better than for those who remain on dialysis overall. However, given that patients with PCD who receive kidney transplantations are a highly selected group, future studies comparing survival for patients on the transplant waitlist versus transplant recipients will be needed to determine whether kidney transplantation improves the outcomes of patients with PCD.

The incidence of death for kidney transplant recipients with ESKD due to PCD were higher than those of non-PCD causes, but lower than ESKD due to diabetes. Our finding is consistent with a 2017 study, where the incidence of death was highest for recipients with ESKD due to diabetes compared with glomerular diseases or other causes [23]. In our study, we further stratify patients by donor type. The incidence of death for living donor recipients is consistently lower than that of their deceased donor counterparts for PCD, diabetes and others, respectively. This finding is concordant with the kidney transplant literature, where living donor types have a lower incidence of death than deceased donor types [30].

The group with ESKD due to PCD had worse patient survival compared with those of other causes. Studies on post-transplant outcomes for recipients with ESKD due to PCD have conflicting results. The outcomes vary depending on the various forms of PCD or the era in which the study was conducted [17–20, 33–35]. The study era is important because new and effective therapies for PCD were available only after early 2000 [16]. Additionally, the studies had small sample sizes [34] and many were limited to single-center studies [33].

In our study, living donor transplants had better outcomes than deceased donor transplants among all groups. However, those with ESKD due to PCD has a worse survival rate compared with ESKD due to diabetes, but only among living donor types. This finding is counterintuitive, but likely caused by different listing practices for living and deceased donor kidney transplantation. In order for patients with ESKD due to PCD to undergo deceased donor kidney transplantation, the PCD must be in remission and the patient must live through the waitlist period (median wait time 4.1 years) [36]. In contrast, living donor recipients can potentially undergo kidney transplantation when they have a suitable living donor. During the early years of transplantation, living donor recipients with ESKD due to PCD could have residual malignancy-related risk factors that may decrease survival. Additionally, certain transplant centers may allow kidney transplantation if the candidate has a living donor, even if the candidate has suboptimal cardiovascular risk or is not qualified for deceased donor wait-listing.

Both graft survival and death-censored graft survival were worse in those with ESKD due to PCD compared with other causes. In a study of kidney transplant outcomes for patients with AL amyloidosis, the majority (18/21) of graft loss was attributed to death with a functioning graft [17]. The remaining three graft losses were due to recurrent amyloid, primary non-function and post-operative complications [17]. In a previous case series of 36 patients with ESKD due to MM who received kidney transplantation, 6 patients experience death-censored graft loss, where 3 lost their grafts due to rejection complications [16].

In our study, the risk of kidney graft rejection was similar among patients with ESKD due to PCD and those of other causes. This was despite a lower proportion of the PCD group receiving depleting therapy at the time of transplantation compared with the non-PCD group [223 (54.4%) versus 87 511 (64.0%)]. The type of PCD therapy may affect the risk of graft rejection. Immunomodulatory drugs such as lenalidomide and pomalidomide are associated with a higher risk of acute graft rejection [37–39]. In contrast, proteasome inhibitors, such as bortezomib, are used to treat refractory antibody-mediated rejection [40]. Recently a study showed that animals treated with daratumumab had reduced donor-specific antibody levels compared with untreated controls, and prolonged kidney graft survival [41]. Although the impact of daratumumab on humans is yet to be studied, it is possible that daratumumab used to treat PCD relapse may have helped prevent rejection in certain cases.

Patient outcomes differed depending on the various forms of PCD. Patient survival in those with ESKD due to MM was not different compared with ESKD due to other causes, whereas those with ESKD due to amyloidosis had worse patient survival compared with those of other causes. Kormann et al. [31] showed that the overall 5-year patient survival of 13 transplanted patients with ESKD due to MM was 65%. Other studies have found that those with ESKD due to amyloidosis had worse survival than those of other causes, but comparable survival with ESKD due to diabetes [17, 20]. These studies included both AL and secondary amyloidosis in their cohort. In terms of graft outcomes, a study of 60 patients with ESKD due to AL amyloidosis showed that 3 had graft failure, 19 died with a functioning graft and 13 had an amyloid recurrence [33]. The authors concluded that outcomes after kidney transplant in patients with ESKD due to AL amyloidosis seem acceptable if a very good partial response or complete response is achieved either before or after transplantation [33].

We found that the top causes of death for the group with ESKD due to MM were unknown (43.48%), followed by malignancy (21.74%), infection (13.04%) and cardio-cerebrovascular disease (13.04%). Based on a collection of cases of kidney transplantation for patients with ESKD due to MM, most deaths after transplantation were not related to MM itself, but rather to sepsis, cardiac disease or de novo malignancy [16]. Although our finding differs from previous studies, the large proportion of unknown cause of death within the MM group limits further interpretation. In the amyloidosis group, other causes (35.14%) and cardiocerebrovascular disease (20.27%) were the most common causes of death. A recent publication by Law et al. [17] highlighted the importance of cardiocerebrovascular death for kidney transplant recipients with amyloidosis, in which an interventricular septal thickness >12 mm was associated with an increased risk of death.

The current study has several limitations. First, the cause of ESKD is assessed by individual physicians and reported to the UNOS/OPTN, but it may not be fully accurate, as confirmatory kidney biopsies are not always performed [42]. Second, hematological data on PCD disease such as stage, cytogenetics, prior therapies, history of stem cell transplantation and recurrence were not available. There is no comprehensive national cancer registry available to link to the UNOS data. As such, the KDIGO Controversies Conference on onconephrology in 2020 stated that one of the research priorities should be to develop a registry that captures granular cancer data on transplant recipients with cancer [21]. Third, it is possible that several of the amyloidosis cases included various forms of amyloidosis (e.g. secondary and genetic) and not the AL form. Fourth, as current US guidelines recommend that patients must have stable remission of PCD before listing for kidney transplant [43, 44], there is inherent selection bias for patients with ESKD due to PCD receiving a kidney transplant. The study finding cannot be generalizable to all patients with PCD nor is it generalizable to transplant centers outside of the USA.

An important strength of this study is that this is the first and largest study to date that quantifies the frequency of kidney transplants occurring in the USA for patients with ESKD due to various forms of PCD and compares the outcomes of kidney transplant recipients of ESKD due to PCD versus diabetes versus others. Additionally, given that treatment options develop quickly in the area of PCD, we adjusted the model using different 3-year time periods. Kidneys for transplantation are a scarce resource, thus comparison of kidney transplantation outcomes of patients with ESKD due to PCD in the context of other causes of ESKD will guide future eligibility criteria for patients with PCD to receive kidney transplantation, particularly at the level of transplant centers. At the patient level, the study findings are important when discussing kidney transplant risk with patients and potential donors.

Our study found that the survival of kidney transplant recipients is worse in ESKD due to PCD compared with those of other causes. Nonetheless, patient survival of the PCD group is similar to the diabetes group, specifically among the deceased donor types. Future research is needed to understand which subgroup of patients with ESKD due to PCD will benefit from kidney transplantation over remaining on dialysis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Mythri Shankar for creating the graphical abstract.

Contributor Information

Jia H Ng, Division of Kidney Diseases and Hypertension, Department of Medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Great Neck, NY, USA.

Stephanie Izard, Center for Health Innovations and Outcomes Research, Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, Northwell Health, Manhasset, NY, USA.

Naoka Murakami, Division of Renal Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Kenar D Jhaveri, Division of Kidney Diseases and Hypertension, Department of Medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Great Neck, NY, USA.

Amy Sharma, Northwell Cancer Institute, Department of Medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, New Hyde Park, NY, USA; New affiliation as of June 2022. Montefiore Medical Center, Department of Hematology and Oncology, NY, USA.

Vinay Nair, Division of Kidney Diseases and Hypertension, Department of Medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Great Neck, NY, USA.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

J.N. is the founder of PublishedMD Consulting. K.D.J. is a consultant for Astex Pharmaceuticals, Natera, GlaxoSmithKline, ChemoCentryx and Chinook, a paid contributor to Uptodate.com, and receives honorarium from the International Society of Nephrology and American Society of Nephrology (ASN). He is editor in chief for the ASN Kidney News. A.S. is a consultant for Vertex Pharmaceuticals. V.N. is a consultant for CareDx. The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

S.I. and J.H.N. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. K.D.J., V.N. and J.H.N. were responsible for the concept and design. S.I. and J.H.N. were responsible for the acquisition and analysis of data. All authors were responsible for the interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript.

FUNDING

J.N. is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases (K23DK132459-01). N.M. is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases (K08DK120868) and by an American Society of Nephrology Foundation for Kidney Research Carl W. Gottschalk Research Scholar Grant.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

This was a retrospective cohort study using the dataset from the UNOS/OPTN. The UNOS/OPTN is a national registry reporting data on donors, recipients, wait-listed candidates and transplant recipients in the USA since 1 October 1987. The dataset used in this study consists of data from 1 October 1987 through 30 June 2018.

REFERENCES

- 1. Katagiri D, Noiri E, Hinoshita F.. Multiple myeloma and kidney disease. Sci World J 2013; 2013: 487285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leung N, Bridoux F, Batuman Vet al. The evaluation of monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance: a consensus report of the International Kidney and Monoclonal Gammopathy Research Group. Nat Rev Nephrol 2019; 15: 45–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Durie BGM, Hoering A, Sexton Ret al. Longer term follow-up of the randomized phase III trial SWOG S0777: bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone vs. lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients (pts) with previously untreated multiple myeloma without an intent for immediate autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). Blood Cancer J 2020; 10: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NKet al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 906–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NKet al. Persistent overall survival benefit and no increased risk of second malignancies with bortezomib-melphalan-prednisone versus melphalan-prednisone in patients with previously untreated multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 448–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bonello F, Mina R, Boccadoro Met al. Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies and antibody products: current practices and development in multiple myeloma. Cancers (Basel) 2019; 12: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Courant M, Orazio S, Monnereau Aet al. Incidence, prognostic impact and clinical outcomes of renal impairment in patients with multiple myeloma: a population-based registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2021; 36: 482–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Decourt A, Gondouin B, Delaroziere JCet al. Trends in survival and renal recovery in patients with multiple myeloma or light-chain amyloidosis on chronic dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 11: 431–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dember LM. Amyloidosis-associated kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 3458–3471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gertz MA, Kyle RA, O'Fallon WM.. Dialysis support of patients with primary systemic amyloidosis. A study of 211 patients. Arch Intern Med 1992; 152: 2245–2250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palladini G, Hegenbart U, Milani Pet al. A staging system for renal outcome and early markers of renal response to chemotherapy in AL amyloidosis. Blood 2014; 124: 2325–2332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dimopoulos MA, Roussou M, Gavriatopoulou Met al. Outcomes of newly diagnosed myeloma patients requiring dialysis: renal recovery, importance of rapid response and survival benefit. Blood Cancer J 2017; 7: e571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll Get al. Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant 2011; 11: 2093–2109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yoo KD, Kim CT, Kim MHet al. Superior outcomes of kidney transplantation compared with dialysis: an optimal matched analysis of a national population-based cohort study between 2005 and 2008 in Korea. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95: e4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford ELet al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1725–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chitty DW, Hartley-Brown MA, Abate Met al. Kidney transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma: narrative analysis and review of the last 2 decades. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Law S, Cohen O, Lachmann HJet al. Renal transplant outcomes in amyloidosis. Nephrol Dial Transplantat 2021; 36: 355–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sherif AM, Refaie AF, Sobh MAet al. Long-term outcome of live donor kidney transplantation for renal amyloidosis. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 42: 370–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pasternack A, Ahonen J, Kuhlbäck B.. Renal transplantation in 45 patients with amyloidosis. Transplantation 1986; 42: 598–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sawinski D, Lim MA, Cohen JBet al. Patient and kidney allograft survival in recipients with end-stage renal disease from amyloidosis. Transplantation 2018; 102: 300–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Małyszko J, Bamias A, Danesh FRet al. KDIGO Controversies Conference on onco-nephrology: kidney disease in hematological malignancies and the burden of cancer after kidney transplantation. Kidney Int 2020; 98: 1407–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. United States Renal Data System. 2020 USRDS Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States . Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23. O'Shaughnessy MM, Liu S, Montez-Rath ME. et al. Kidney transplantation outcomes across GN subtypes in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 28: 632–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kadiyala A, Mathew AT, Sachdeva Met al. Outcomes following kidney transplantation in IgA nephropathy: a UNOS/OPTN analysis. Clin Transplant 2015; 29: 911–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. European best practice guidelines for renal transplantation . Section IV: long-term management of the transplant recipient. IV.13 analysis of patient and graft survival. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17: 60–67 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Foucher Y, Daguin P, Akl Aet al. A clinical scoring system highly predictive of long-term kidney graft survival. Kidney Int 2010; 78: 1288–1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maluf DG, Fisher RA, King ALet al. Hepatitis C virus infection and kidney transplantation: predictors of patient and graft survival. Transplantation 2007; 83: 853–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pessione F, Cohen S, Durand Det al. Multivariate analysis of donor risk factors for graft survival in kidney transplantation. Transplantation 2003; 75: 361–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hariharan S, Johnson CP, Bresnahan BAet al. Improved graft survival after renal transplantation in the united states, 1988 to 1996. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 605–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nemati E, Einollahi B, Lesan Pezeshki Met al. Does kidney transplantation with deceased or living donor affect graft survival? Nephrourol Mon 2014; 6: e12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kormann R, Pouteil-Noble C, Muller Cet al. Kidney transplantation for active multiple myeloma or smoldering myeloma: a case-control study. Clin Kidney J 2019; 14: 156–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lam R, Lim MA, Dember LM.. Suitability for kidney transplantation in AL amyloidosis: a survey study of transplant and amyloidosis physicians. Kidney360 2021; 2: 1987–1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heybeli C, Bentall A, Wen Jet al. A study from the Mayo Clinic evaluated long-term outcomes of kidney transplantation in patients with immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis. Kidney Int 2021; 99: 707–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leung N, Lager DJ, Gertz MAet al. Long-term outcome of renal transplantation in light-chain deposition disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43: 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Penn I. Evaluation of transplant candidates with pre-existing malignancies. Ann Transplant 1997; 2: 14–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KCet al. US Renal Data System 2017 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2018; 71: A7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lum EL, Huang E, Bunnapradist Set al. Acute kidney allograft rejection precipitated by lenalidomide treatment for multiple myeloma. Am J Kidney Dis 2017; 69: 701–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meyers D E, Adu-Gyamfi B, Segura AMet al. Fatal cardiac and renal allograft rejection with lenalidomide therapy for light-chain amyloidosis. Am J Transplant 2013; 13: 2730–2733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nadeau Nguyen M, Nayernama A, Jones SCet al. Solid organ transplant rejection associated with the use of the immunomodulatory drugs (IMIDs). Blood 2019; 134(Suppl 1): 2189 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Woodle ES, Alloway RR, Girnita A.. Proteasome inhibitor treatment of antibody-mediated allograft rejection. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2011; 16: 434–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kwun J, Matignon M, Manook Met al. Daratumumab in sensitized kidney transplantation: potentials and limitations of experimental and clinical use. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019; 30: 1206–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Grams ME, Plantinga LC, Hedgeman Eet al. Validation of CKD and related conditions in existing data sets: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 2011; 57: 44–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Al-Adra DP, Hammel L, Roberts Jet al. Preexisting melanoma and hematological malignancies, prognosis, and timing to solid organ transplantation: a consensus expert opinion statement. Am J Transplant 2021; 21: 475–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chadban SJ, Ahn C, Axelrod DAet al. KDIGO clinical practice guideline on the evaluation and management of candidates for kidney transplantation. Transplantation 2020; 104(4 Suppl 1): S11–S103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This was a retrospective cohort study using the dataset from the UNOS/OPTN. The UNOS/OPTN is a national registry reporting data on donors, recipients, wait-listed candidates and transplant recipients in the USA since 1 October 1987. The dataset used in this study consists of data from 1 October 1987 through 30 June 2018.