Abstract

Background

Endometrial carcinoma (EC) is the most common gynaecological cancer worldwide. The Cancer Genome Atlas molecular grouping of a given case of EC could be assessed by POLE gene mutation, mismatch repair (MMR) ‘to reflect microsatellite instability’ and p53 status, which has proved to be of prognostic value. Programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) are playing a progressively important role in tumour immunology and cancer treatment.

Objectives

To investigate PD-L1 immunohistochemical expression in EC in relation to MMR and p53 status. Associations between marker expression and different histopathological parameters were also investigated.

Methods

This retrospective study was performed on archival biopsies of 170 cases of EC using a tissue microarray model. Immunohistochemical staining was applied using antibodies against PD-L1, MLH1, MSH2 and p53.

Results

The percentages of positivity were as follows: PD-L1, 19.6%; MLH1, 79.5%; MSH2, 78.5%; and p53 mutant, 13.8%. There was significant correlation between MLH1 expression and MSH2 expression (p = 0.008). Tumour grade was significantly correlated with stage (p = 0.005) and p53 mutant expression (p = 0.008). Combined PD-L1 positivity and MMR deficiency showed significant correlation with the presence of lymphovascular space invasion (p = 0.014). MSH2 negativity was significantly associated with poorer overall survival (p = 0.014).

Conclusions

A panel of immunohistochemical markers (PD-L1, MLH1, MSH2 and p53) could help to predict the prognosis and plan the treatment of patients with EC. MMR deficiency seems to be a good predictor for PD-L1 status, and therefore the response to potential PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy.

Keywords: Endometrial carcinoma, Immunotherapy, Prognostic markers, PD-L1, MMR, P53

1. Introduction

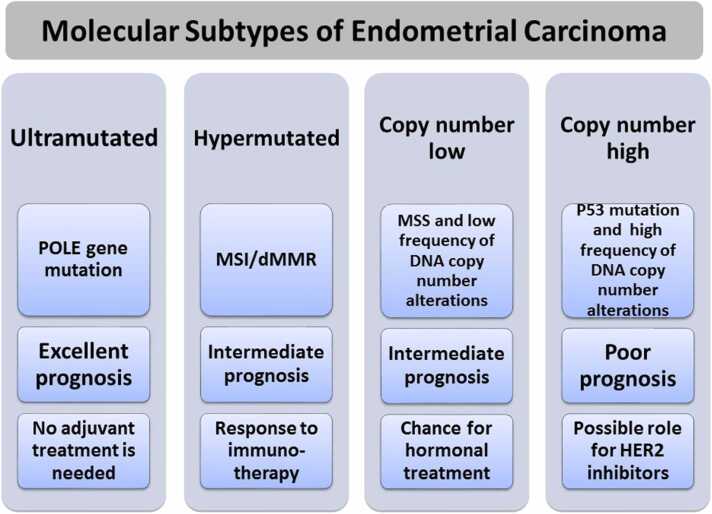

Endometrial carcinoma (EC) is the most common gynaecological cancer worldwide, and represents the sixth leading cause of cancer-related death among women. Traditionally, it can broadly be divided into two types: endometrioid carcinoma (type 1) and non-endometrioid carcinoma (type 2) [1], [2]. Unlike type 1 carcinomas, type 2 carcinomas are highly aggressive and typically carry a poor prognosis. According to the World Health Organization classification, type 2 ECs are mainly uterine serous carcinomas (USCs) [2]. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) programme described four prognostically distinct groups of EC according to tumour mutational burden and somatic copy number alterations (Fig. 1) [3]: ultramutated EC which has DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE) mutations in the exonuclease domain; hypermutated EC with microsatellite instability (MSI); low-mutation-rate EC with low frequency of DNA copy-number alterations; and low-mutation-rate EC with high frequency of DNA copy-number alterations [3], [4]. In practice, the molecular subtype of a given EC case can be assessed by exploring POLE gene mutation, MSI and p53 status. This has been proved to be of prognostic value [4], [5]. The first category (ultramutated EC) has the best prognosis and there are potential therapeutic implications for each category (Fig. 1) [5]. However, POLE gene mutation testing still relies on DNA sequencing, which is not available in many pathology laboratories [5]. Uterine and ovarian carcinomas are believed to share similar cancer genetic drivers and progression mechanisms in many situations, such as p53 mutation [6]. Therefore, the treatment strategies of EC and ovarian carcinoma may carry significant potential value [7]. Among the different therapeutic strategies is novel immunotherapy, such as pembrolizumab. This has had an active response for patients with gynaecological malignancies. As such, immunotherapeutic strategies need to be developed and established for patients with aggressive EC, including USC [6], [7], [8], [9]. Programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) are playing a progressively important role in tumour immunology and cancer treatment. Several studies have investigated PD-L1 expression and its prognostic values in EC [6], [7]. However, many of these studies did not consider the correlation with mismatch repair gene expression and p53 status [6], [7], [10]. The poorer outcome for patients with aggressive EC, such as USC, using traditional treatment methods portends great importance in finding effective targeted immunotherapy. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate PD-L1 expression and its prognostic value in EC in relation to MMR and p53 status.

Fig. 1.

Molecular types of endometrial carcinoma with prognstic significance and possible impact on treatment planning. MSI, microsatellite instability; dMMR, mismatch repair deficiency.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample selection

This retrospective study used archival biopsies of 170 cases of EC. The materials were retrieved from the archives of the Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine and Oncology Centre, Mansoura University, for the period between 2008 and 2014. Patients’ data were collected from the Clinical Oncology and Nuclear Medicine Department and the Oncology Centre, Mansoura University. There were 127 cases of EC (G1, n = 56; GII, n = 57; GIII, n = 14) and 43 cases of non-EC. The slides were re-examined for revision of the histologic type. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2009 criteria were used for grading and staging. All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Mansoura University [Institutional Review Board (IRB) Ref. MD15.09.08, dated 18th September 2015] in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Formal written informed consent was not required, with a waiver from the IRB.

2.2. Tissue microarray construction

Tissue microarray (TMA) construction was performed in a similar way as described previously [1], [11]. After reviewing the slides stained with haematoxylin and eosin, a representative slide of the tumour was chosen from each case, and an area of tumour on the representative slide was circled. The corresponding paraffin block was retrieved. Using a manual tissue arrayer (Beecher Instruments Inc., Sun Prairie, WI, USA), the chosen area from the donor block was cored with a 0.6-mm-diameter cylinder tissue punch and placed in the recipient paraffin block. Three cores were taken from the tumour in each case.

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

Sections from the TMA blocks were cut at a thickness of 4 µm and stained using an automated immunostainer (BenchMark, Roche, Tucson, AZ, USA), with antibodies against PD-L1 clone 22C3 (Dako, Carpenteria, CA, USA), MLH1 (mouse monoclonal, clone M1, pre-diluted), MSH2 (mouse monoclonal, clone G219–1129, pre-diluted) and p53 (mouse monoclonal, Genemed, Torrance, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.4. Evaluation of immunohistochemical staining

Slides were evaluated by two pathologists, blinded to patient characteristics and outcomes, using standard light microscopes.

2.4.1. PD-L1

PD-L1 expression was determined using a combined positive score (CPS), which is the number of PD-L1-stained cells (tumour cells, lymphocytes, macrophages) divided by the total number of viable tumour cells, multiplied by 100. Any convincing partial or complete linear membrane staining (≥1 + intensity) of viable tumour cells that is perceived as distinct from cytoplasmic staining was considered as PD-L1 staining and included in the scoring. Any membrane and/or cytoplasmic staining (≥1 +) of lymphocytes and macrophages (immune cells) within tumour nests and/or adjacent supporting stroma was considered as PD-L1 staining and included in the scoring. PD-L1 expression was examined at higher magnification (20x), and CPS was calculated. CPS ≥ 1 was considered positive [12], [13].

2.4.2. MLH1 and MSH2

Any positive reaction in the nuclei of tumour cells was considered as intact expression (normal), even if patchy or in only one core of the case. An interpretation of expression loss in tumour cells was made only if a positive reaction was seen in internal control cells, such as the nuclei of stromal, inflammatory or non-neoplastic epithelial cells [14], [15].

2.4.3. p53

Immunohistochemistry of p53 was reported as mutant or wild-type. The mutant expression patterns were either overexpression, diffuse strong nuclear positivity in ≥ 80% of the nuclei of the tumour cells, or complete absence of staining. Wild-type expression was applied to those cases showing an admixture of negative, weakly positive and strongly positive tumour cells [16], [17], [18].

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS Version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Qualitative data were described using number and percentage. Quantitative data were described using median (range) for non-parametric data, and mean [standard deviation (SD)] for parametric data after testing normality using Kolmogrov–Smirnov test. The significance of the obtained results was judged at the 0.05 level. Chi-squared test was used to test the significance of differences in categorical variables between various groups. The Monte Carlo test was used as correction for the Chi-squared test when > 25% of cells had a count < 5 in tables (>2 ×2). The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare independent non-normally distributed data. Spearman’s correlation was used to compare continuous non-normally distributed data. The Kaplan–Meier test was used to calculate overall survival and disease-free survival using log rank test to detect the effects of risk factors affecting survival.

3. Results

This study used archival material of 170 patients with EC. Patient age ranged from 37 to 79 years, with a mean age of 59.8 (SD 8.2) years. Immunohistochemical expression of PD-L1, MLH1, MSH2 and p35 was assessed using a TMA model.

3.1. Expression patterns of different markers

Table 1 shows the percentages of expression of the studied markers, after exclusion of any non-assessable TMA spots. PD-L1-positive cases showed tumour cell positivity alone (n = 9), immune cell positivity alone (n = 7), and both tumour cell and immune cell positivity (n = 12). Examples of the different immunohistochemical expression patterns of the examined markers are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical expression patterns among the studied cases.

| Staining patterns | |

|---|---|

| PD-L1 | Positive: 28 (19.6%) Negative: 115 (80.4%) |

| MLH1 | Positive: 124 (79.5%) Negative: 32 (20.5%) |

| MSH2 | Positive: 117 (78.5%) Negative: 32 (21.5%) |

| p53 | Wild-type: 144 (86.2%) Mutant: 23 (13.8%) |

Fig. 2.

Examples of different immunohistochemical expression patterns. PD-L1: tumour cell (arrow) (A), immune cell (*) (B), and both tumour and immune cells (C). MLH1: diffuse strong (D), focal moderate (E) and negative staining with positive internal control (*) (F). MSH2: diffuse strong (G), focal moderate (H) and negative staining with positive internal control (*) (I). p53: mutant, diffuse strong (J); wild-type, patchy moderate (K); and week to absent staining (L) (original magnification 400x).

3.2. Association of immunohistochemical expression with different histopathological parameters

Immunohistochemical expression of each marker, correlated with the expression of other markers, and tumour size, grade and stage is summarized in Table 2. Significant correlation was found between MLH1 expression and MSH2 expression (p = 0.008). Tumour grade was significantly correlated with stage (p = 0.005) and p53 mutant pattern (p = 0.008).

Table 2.

Associations between immunohistochemical expression, tumour size, grade and stage.

| MLH1 | MSH2 | PD-L1 | p53 | Size | Grade | Stage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLH1 | R | 1.000 | ||||||

| P | . | |||||||

| MSH2 | R | 0.220** | 1.000 | |||||

| P | 0.008 | . | ||||||

| PD-L1 | R | 0.049 | -0.020 | 1.000 | ||||

| P | 0.577 | 0.822 | . | |||||

| p53 | R | 0.047 | 0.152 | 0.016 | 1.000 | |||

| P | 0.571 | 0.073 | 0.854 | . | ||||

| Tumour size | R | -0.098 | 0.087 | -0.110 | 0.209* | 1.000 | ||

| P | 0.354 | 0.412 | 0.331 | 0.039 | . | |||

| Grade | R | 0.024 | 0.080 | 0.052 | 0.406** | 0.155 | 1.000 | |

| P | 0.780 | 0.363 | 0.571 | 0.008 | 0.112 | . | ||

| Stage | R | 0.042 | 0.043 | 0.104 | 0.072 | 0.091 | 0.322** | 1.000 |

| P | 0.631 | 0.626 | 0.262 | 0.389 | 0.353 | 0.005 | . |

r:Point Biserial correlation coefficient.

3.3. Combined immunohistochemical expression patterns

The specific combination of PD-L1 positivity and MMR deficiency was significantly correlated with lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI) (p = 0.014), as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlation of combined PD-L1 positivity and MMR deficiency [MHL1(-) and/or MSH2 (-)] with tumour size, grade, stage, lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI), cervical invasion and lymph node metastasis.

| PD-L1 positivity and MMR deficiency |

Test of significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent n = 116 |

Present n = 6 |

|||

| Tumour size | Median (range) | 4 (1–11) | 2.5 (0.5–5) | Z = 1.42 p = 0.155 |

| Grade | 1 2 3 |

41 (35.3) 42 (36.2) 33 (28.4) |

1 (16.7) 5 (83.3) 0 |

χ2MC= 5.57 p = 0.062 |

| Stage | IA IB IIA IIB IIIB IVA |

62 (55.4) 19 (17.0) 10 (8.9) 7 (6.2) 13 (11.6) 1 (0.9) |

4 (57.1) 1 (14.3) 2 (28.6) 0 0 0 |

MC p = 0.569 |

| LVSI | - + |

96 (72.2) 37 (27.8) |

2 (28.6) 5 (71.4) |

χ2FET= 6.02 p = 0.014 |

| Cervical invasion | - + |

120 (88.2) 16 (11.8) |

5 (71.4) 2 (28.6) |

χ2 = 1.71 p = 0.191 |

| Lymph node metastasis | - + |

130 (95.6) 6 (4.4) |

7 (100) 0 |

χ2 = 0.322 p = 0.570 |

3.4. Association between immunohistochemical expression and patient outcome

As shown in Table 4, MSH2 was the only marker to show significant correlation with overall survival (p = 0.014).

Table 4.

Expression of markers in relation to overall survival.

| Median overall survival (95% CI) |

Log rank χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 Negative Positive |

96.92 (79.63–114.21) 55.2 (36.27–74.13) |

0.266 | 0.606 |

| MLH1 Negative Positive |

77.6 (24.64–130.56) 69.28 (60.02–78.53) |

0.0 | 0.994 |

| MSH2 Negative Positive |

29.96 (10.84–49.07) 109.89 (97.75–122.03) |

6.09 | 0.014 |

| p53 Wild-type Mutant |

103.62 (89.19–118.05) 47.14 (26.22–68.07) |

1.01 | 0.315 |

CI, confidence interval.

4. Discussion

The molecular classification of EC has been proved to be of diagnostic and prognostic significance [2], [4], [5]. This could be translated into practice simply by testing POLE gene mutation, MSI and p53 status [4]. PD-L1 plays an important role in tumour immunology and cancer treatment, and studies have investigated the value of its expression in EC [8], [9], [10].

In this study, immunohistochemical expression of PD-L1, MLH1, MSH2 and p53 was assessed in relation to different clinicopathological parameters in patients with EC. Overall, 19.6% of cases were positive for PD-L1 (tumour cell positivity alone, 6.3%; immune cell positivity alone, 4.9%; both tumour cell and immune cell positivity, 8.4%). These findings are similar to those of a previous study where 21.2% of patients with EC were PD-L1 positive [10]. The percentage was higher in studies using high-grade carcinomas alone (30% in clear cell carcinomas and 50% in undifferentiated/dedifferentiated carcinomas) [8], [9]. Previous studies found that PD-L1 expression was slightly higher in tumour cells (8.6% vs 14%) and much higher in immune cells (27.7% vs 37.3%) compared with the present study [12], [19], [20]. This could be explained by tissue heterogeneity that may be suboptimally reflected by TMA, as well as the exclusive inclusion of high-risk cases [19], [20]. The MMR status of EC and colorectal cancer are assessed routinely by immunohistochemistry for MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 and MSH6, functionally coupled as MLH1/PMS2 and MSH2/MSH6 [21], [22]. Among those markers, MLH1 and MSH2 are considered to be the most important to reflect MMR status [23]. The present study found a similar percentage of MLH1 positivity compared with previous studies [21], [22]. However, MSH2 negativity was higher in the present study compared with some previous studies [21], [24], but lower compared with another study [25]. For p53, the present study found a mutant pattern of expression in approximately 14% of cases, despite the fact that approximately 25% of the series were non-ECs. Previous studies showed that p53 mutation was detected in approximately 25% of all patients with EC. The frequency of p53 mutations in type I EC is approximately 10–40%, compared with approximately 90% in type II EC [3], [26]. Differences between these results and the results of the present study may be attributed to sampling matters and TMA construction.

Associations between marker expression, the expression of other markers, and the different clinicopathological parameters revealed that MLH1 expression is significantly correlated with MSH2 expression, as reported previously [22]. The present study found that p53 expression was correlated with tumour grade, being mutant for serous carcinoma; this finding is supported by previous studies [3], [26]. As expected, positive correlation was found between tumour grade and stage, as higher grade tumours were associated with higher stage [27].

Regarding the association of different combinations of marker expression with various clinicopathological parameters, combined PD-L1 positivity and MMR deficiency (MHL1 negative and/or MSH2 negative) was found to be correlated with LVSI. Previous studies found that combined PD-L1 positivity and MMR deficiency was associated with adverse findings, such as high tumour grade [10]; therefore, there is a potential role for immunotherapy to benefit EC patients with MMR deficiency [6], [7], [9], [12]. The association found between PD-L1 positivity and MMR deficiency in the present study was lower than reported previously [28]. This could be attributed to sampling and TMA matters.

Among the examined markers, MSH2 was the only marker to show correlation with overall survival, as MSH2 negativity was found to be associated with poorer survival. This finding is in contrast to some previous studies [29], [30], [31], but supports other studies [6], [25].

This study had some limitations. Despite the benefits of TMA, such as cost effectiveness and assurance of experimental uniformity, it may not reflect tissue heterogeneity appropriately. However, with the use of three cores from each case, as in this study, the expression of immunohistochemical markers should be reflected reliably [32]. Even for those markers with focal expression, such as PD-L1, the present results are comparable with those from previous studies using full tissue sections [10]. Another limitation is that the cases were not tested for POLE gene mutation [5]. This would have added more insight into the potential value of PD-L1 expression in relation to MMR, p53 and the other clinicopathological parameters. At present, PCR/NGS is the gold standard for assessing POLE gene status [4], [5].

In conclusion, a panel of immunohistochemical markers (PD-L1, MLH1, MSH2 and p53) could help to predict the prognosis and plan the treatment of patients with EC. The combination of PD-L1 positivity and MMR deficiency may be associated with aggressive features, such as the presence of LVSI. MMR deficiency seems to be a good predictor for PD-L1 status, and therefore the response to potential PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy [33], [34]. MSH2 negativity alone could reflect poor overall survival.

It is recommended that this panel of immunohistochemical markers should be performed for patients with EC, especially those who are potential candidates for immunotherapy, and patients with recurrent disease without a well-known primary tumour immunohistochemical status. A panel of four immunohistochemical markers is cost beneficial, and can be afforded by most pathology laboratories for daily use.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

This study is the outcome of a research project (entitled: Impact of Genetic Alterations on the Management of Endometrial Carcinoma) supported by the research fund unit of Mansoura University.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Salama A., Arafa M., ElZahaf E., et al. Potential role for a panel of immunohistochemical markers in the management of endometrial carcinoma. J Pathol Transl Med. 2019;53:164–172. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2019.02.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matias-Guiu X., Longacre T.A., McCluggage G.W. WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs. 5th edn.., 2020. Tumours of the uterine corpus: introduction; pp. 246–247. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Kandoth C., Schultz N., et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talhouk A., McConechy M.K., Leung S., et al. Confirmation of ProMisE: a simple, genomics-based clinical classifier for endometrial cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:802–813. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almadani N., Thompson E., Tessier-Cloutier B., et al. An update of molecular pathology and shifting systems of classification in tumours of the female genital tract. DiagnHistopathol. 2020;26:278–288. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evrard C., Alexandre J. Predictive and prognostic value of microsatellite instability in gynecologic cancer (endometrial and ovarian) Cancers. 2021;13:2434. doi: 10.3390/cancers13102434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills A.M., Bullock T.N., Ring K.L. Targeting immune checkpoints in gynecologic cancer: updates & perspectives for pathologists. Mod Pathol. 2022;35:142–151. doi: 10.1038/s41379-021-00882-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin C., Hacking S., Liang S., Nasim M. PD-L1/PD-1 expression in endometrial clear cell carcinoma: a potential surrogate marker for clinical trials. Int J Surg Pathol. 2020;28:31–37. doi: 10.1177/1066896919862618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hacking S., Jin C., Komforti M., Liang S., Nasim M. MMR deficient undifferentiated/dedifferentiated endometrial carcinomas showing significant programmed death ligand-1 expression (sp 142) with potential therapeutic implications. Pathol Res Pr. 2019;215 doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2019.152552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amarin J.Z., Mansour R., Al-Ghnimat S., et al. Differential characteristics and prognosis of PD-L1-positive endometrial carcinomas: a retrospective chart review. Life. 2021;11:1047. doi: 10.3390/life11101047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arafa M., Kridelka F., Mathias V., et al. High frequency of RASSF1A and RARb2 gene promoter methylation in morphologically normal endometrium adjacent to endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Histopathology. 2008;53:525–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasanen A., Ahvenainen T., Pellinen T., et al. PD-L1 expression in endometrial carcinoma cells and intratumoral immune cells: differences across histologic and TCGA-based molecular subgroups. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:174–181. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PD-L1 I.H.C. 22C3 pharmDx interpretation manual: cervical cancer. Santa Clara, CA: Agilent; 2022. Available at: 〈https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/usermanuals/public/29257_22c3_pharmDx_cervical_interpretation_manual_us.pdf〉 (last accessed 17 November 2022).

- 14.Mills A.M., Liou S., Ford J.M., et al. Lynch syndrome screening should be considered for all patients with newly diagnosed endometrial cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1501–1509. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burgart, L.J., Chopp, W.V., Jain, D., Bellizzi, A.M., Fitzgibbons, P.L., Template for reporting results of biomarker testing of specimens from patients with carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Northfield, IL: College of American Pathologists; 2021. Available at: 〈https://documents.cap.org/protocols/ColoRectal.Bmk_1.3.0.0.REL_CAPCP.pdf〉 (last accessed 17 November 2022).

- 16.Köbel M., Reuss A., du Bois A., et al. The biological and clinical value of p53 expression in pelvic high-grade serous carcinomas. J Pathol. 2010;222:191–198. doi: 10.1002/path.2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCluggage W.G., Soslow R.A., Gilks C.B. Patterns of p53 immunoreactivity in endometrial carcinomas: 'all or nothing' staining is of importance. Histopathology. 2011;59:786–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Köbel M., Ronnett B.M., Singh N., et al. Interpretation of p53 immunohistochemistry in endometrial carcinomas: toward increased reproducibility. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2019;38(Suppl. 1) doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000488. S123–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasanen A., Ahvenainen T., Pellinen T., et al. PD-L1 expression in endometrial carcinoma cells and intratumoral immune cells: differences across histologic and TCGA-based molecular subgroups. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:174–181. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zong L., Sun Z., Mo S., et al. PD-L1 expression in tumor cells is associated with a favorable prognosis in patients with high-risk endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;162:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruegl A.S., Djordjevic B., Urbauer D.L., et al. Utility of MLH1 methylation analysis in the clinical evaluation of Lynch syndrome in women with endometrial cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:1655–1663. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashmi A.A., Mudassir G., Hashmi R.N., et al. Microsatellite instability in endometrial carcinoma by immunohistochemistry, association with clinical and histopathologic parameters. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20:2601–2606. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.9.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang S.M., Jiang B., Deng Y., et al. Clinical significance of MLH1/MSH2 for stage II/III sporadic colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;11:1065–1080. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i11.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haraga J., Nagasaka T., Nakamura K., et al. Significance of MSH2 promoter methylation in endometrial cancer with MSH2 deficiency. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(Suppl. 5):V348. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mwafy S., Elanwar N., Eid A. Mismatch repair status in endometrioid type of endometrial carcinoma: association with clinicopathological parameters. Int J Cancer Biomed Res. 2020;4:209–215. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura M., Obata T., Daikoku T., Fujiwara H. The association and significance of p53 in gynecologic cancers: the potential of targeted therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5482. doi: 10.3390/ijms20215482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Çakıroğlu Y., Doğer E., Yıldırım Kopuk Ş., et al. Prediction of tumor grade and stage in endometrial carcinoma by preoperative assessment of sonographic endometrial thickness: is it possible? Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;11:211–214. doi: 10.4274/tjod.35651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Favier A., Varinot J., Uzan C., et al. The role of immunohistochemistry markers in endometrial cancer with mismatch repair deficiency: a systematic review. Cancers. 2022;14:3783. doi: 10.3390/cancers14153783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato M., Takano M., Miyamoto M., et al. DNA mismatch repair-related protein loss as a prognostic factor in endometrial cancers. J Gynecol Oncol. 2015;26:40–45. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2015.26.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tangjitgamol S., Kittisiam T., Tanvanich S. Prevalence and prognostic role of mismatch repair gene defect in endometrial cancer patients. Tumour Biol. 2017;39 doi: 10.1177/1010428317725834. 1010428317725834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fountzilas E., Kotoula V., Pentheroudakis G., et al. Prognostic implications of mismatch repair deficiency in patients with nonmetastatic colorectal and endometrial cancer. ESMO Open. 2019;4 doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arafa M., Boniver J., Delvenne P. Progression model tissue microarray (TMA) for the study of uterine carcinomas. Dis Mark. 2010;28:267–272. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2010-0709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mamat Yusof M.N., Chew K.T., Kampan N., et al. PD-L1 expression in endometrial cancer and its association with clinicopathological features: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers. 2022;14:3911. doi: 10.3390/cancers14163911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamashita H., Nakayama K., Ishikawa M., et al. Microsatellite instability is a biomarker for immune checkpoint inhibitors in endometrial cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;9:5652–5664. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]