Abstract

The 2006 European National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) showed that a large proportion of asthmatics had uncontrolled asthma. The current analysis estimated the prevalence of asthma and asthma control (Asthma Control Test™ (ACT); QualityMetric Inc., Lincoln, RI, USA) in five European countries using the 2008 NHWS. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL), using the Short Form-12 (SF-12) health survey, and work productivity/activity impairment were assessed.

Of 3,619 respondents aged ≥18 yrs, the prevalence of self-reported physician diagnosis of asthma was 6.1% (15 million people); 56.6% of treated asthmatics were not well-controlled (NWC; ACT score ≤19). Individual components of the ACT showed that, compared with at least well-controlled patients (ALWC; ACT score ≥20), NWC patients had activity limitations at least some of the time (40.8% versus 1.5%, p<0.001), were breathless ≥3 times per week (72.5% versus 5.4%, p<0.001), suffered sleep difficulties due to asthma at least once per week (60.3% versus 4.6%, p<0.001) and required rescue medication ≥2–3 times per week (77.4% versus 15.9%, p<0.001). NWC patients had also received more healthcare contact in the past 6 months, including hospitalisation (17.4% versus 9.9%, p<0.001). The SF-12 physical and mental summary scores were 7.46 and 4.73 points higher, respectively, for ALWC patients compared with NWC patients (p<0.001). ALWC patients reported less absenteeism (5.5% versus 12.2%) and work impairment (15.4% versus 30.0%) than NWC patients (both p<0.001).

The proportion of asthmatics with NWC asthma has not improved since 2006. ALWC asthma is associated with a significant positive impact on healthcare resource use, HRQoL and work productivity.

Keywords: Adults, asthma control, Europe, National Health and Wellness survey

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory condition of the lungs that causes increased airway hyperresponsiveness and recurrent episodic wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing [1]. Currently, approximately 300 million people worldwide have asthma, with the global prevalence ranging from 1% to 18% of the population in different countries [1]. Whilst decreases in prevalence have been observed in North America and Western Europe, there is good evidence for increased prevalence in regions where prevalence was previously low, particularly in developing countries as they become more urbanised [1, 2]. In addition to the substantial effects of asthma on morbidity and mortality [2], there is also a significant economic burden associated with asthma [3]. Costs due to asthma include both direct costs, such as physician visits, hospital care and medications, and indirect costs, such as lost work days. Furthermore, mean annual costs per patient have been shown to increase as the level of disease control decreases [3].

The main goal of asthma treatment is to achieve and maintain clinical control [1, 4], and when asthma is controlled severe exacerbations should be rare and there should be no more than occasional symptoms [1]. Despite such guidelines [1], the Asthma Insights and Reality surveys found that the understanding and management of asthma was poor across all regions [5]. In the Asthma Insights and Reality in Europe study, for example, only 5.3% of patients met the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) criteria for defined asthma control, and half of the adults surveyed reported daytime symptoms at least once a week with a further 30% reporting sleep disturbances at least once a week [6]. More recently, the 2006 European National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS; Consumer Health Sciences, Princeton, NJ, USA), for which data from five European countries was collected, reported that approximately half of all treated patients with diagnosed asthma were not well-controlled [7]. Although this was less than previously reported, it still highlighted a need for the continuing education of patients and physicians on the importance of achieving and maintaining clinical control.

The aim of the current analysis was to re-assess the level of asthma control and the associated health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and healthcare resource use in five European countries using data collected from the 2008 NHWS.

METHODS

Study design

The methods for obtaining data have been published previously and will be summarised herein [7]. Data were obtained from the 2008 NHWS (Consumer Health Sciences), an annual cross-sectional survey of the health status, attitudes, behaviours and outcomes of adults aged ≥18 yrs in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK. Participating subjects completed self-administered, web-based questionnaires. No formal approval of the survey or informed consent was required but information about confidentiality and the voluntary nature of participation was included as part of the survey. Data from patients with self-reported, diagnosed asthma were used for the analyses presented herein.

Outcome measures

Asthma control

Asthma control was assessed using the validated Asthma Control Test™ (ACT; QualityMetric, Inc., Lincoln, RI, USA) [8], a self-administered questionnaire which is aligned with levels of asthma control defined by GINA [1]. The ACT scores range from 5 to 25 with a score of ≥20 denoting at least well-controlled asthma and a score of ≤19 denoting not well-controlled asthma. The recall period of the questionnaire is 4 weeks.

Demographics and asthma-specific characteristics

Patients answered questions about their demographics and general health. In addition, specific information about their asthma, such as duration of disease, symptoms during the previous 4 weeks and asthma medication use, was collected. Medication adherence was assessed using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS), which assesses four reasons for non-adherence: forgetfulness, carelessness, feeling better and feeling worse. The overall MMAS score ranges from 0 (highly adherent) to 4 (highly non-adherent) [9].

The participants also answered questions about their healthcare attitudes, such as perceptions about their health status and medications, scoring on a five-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Responses of a four or five were categorised as agreement with the statement.

Healthcare resource use

Information was collected on number and type of contact with healthcare physicians in the previous 6 months. This included three patient-reported metrics: medical provider visits (general practitioners or specialists); emergency room (ER) visits; and hospitalisations [7].

Patient-reported outcomes

Work productivity loss and activity impairment

Work productivity loss and activity impairment was assessed for the past 7 days using the Work Productivity Loss and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire [10]. The WPAI yields four metrics of impairment due to health: absenteeism or percentage of work time missed; presenteeism or percentage of impairment while working; percentage of overall work productivity impairment which considers both absenteeism and presenteeism; and percentage of impairment in daily activities.

WPAI outcomes are expressed as impairment percentages, with higher percentages indicating greater impairment and less productivity.

HRQoL

The Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) was used to assess the HRQoL of the past 4 weeks. The SF-12 is a generic measure of health status that consists of 12 items covering eight domains: physical functioning; role limitations due to physical health problems; bodily pain; general health; vitality; social functioning; role limitations due to emotional problems; and mental health [11]. The SF-12 yields normative physical and mental summary measures that also correspond with the summary measures of the SF-36 [11, 12]. All 12 items are used to calculate the physical and mental health composite scores (PCS-12 and MCS-12, respectively). Each score ranges from 0 to 100 where 0 indicates the lowest level of health and 100 indicates the highest level of health. Both the PCS and MCS combine the 12 items in such a way that they compare to a national norm with a mean±sd score of 50.0±10.0. A change of three to five units has been deemed clinically important [13].

Statistical analysis

Prevalence estimates were computed using frequency weights, based on sex, age and country of residence. The known population for each country was defined using the International Database of the US Census Bureau and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2008 mid-year population sex and age estimates) [14]. In addition, an asthma control index (ACI) was computed as the ratio of at least well-controlled to not well-controlled treated asthma sufferers [7].

Patients with asthma who were not well-controlled were compared to those who were at least well-controlled using weighted data. The Chi-squared test was used to test for significant differences in categorical variables, and unpaired t-tests were used to test for significant differences in continuous variables. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Asthma prevalence and control

A total of 53,524 participants responded to the 2008 European NHWS and of these 3,619 were patients with self-reported, physician-diagnosed asthma. Applying frequency weights, the prevalence of diagnosed asthma across the five European countries was 6.1% of the adult population which extrapolates to approximately 15 million people (table 1). The highest and lowest reported prevalence was in the UK (10%, 5 million) and Italy (4.4%, 2 million), respectively.

Table. 1—

Prevalence of asthma control for diagnosed and treated asthma in 2008

| All countries |

France |

Germany |

Italy |

Spain |

UK |

|

| Diagnosed asthma# | 15.15¶ (6) | 2.86 (6) | 3.71 (5) | 2.13¶ (4) | 1.61 (5) | 4.84 (10) |

| Not well-controlled | 7.89 (52) | 1.17 (41) | 2.30 (62) | 1.35 (63) | 0.75 (47) | 2.33 (48) |

| At least well-controlled | 7.25 (48) | 1.70 (59) | 1.41 (38) | 0.77 (36) | 0.86 (53) | 2.51 (52) |

| Treated asthma# | 11.87 (78) | 1.98 (69) | 2.97 (80) | 1.47 (69) | 1.11 (69) | 4.32 (89) |

| Not well-controlled | 6.72 (57) | 1.00 (51) | 2.00 (67) | 0.98 (67) | 0.53 (47) | 2.21 (51) |

| At least well-controlled | 5.15 (43) | 0.98 (49) | 0.97 (33) | 0.49 (33) | 0.59 (53) | 2.11 (49) |

Data are presented as prevalence millions (% total population) and prevalence millions (% of diagnosed asthma) for diagnosed asthma and treated asthma, respectively. #: extrapolated to EU population in millions; ¶: sum of not well-controlled and at least well-controlled greater than total due to rounding.

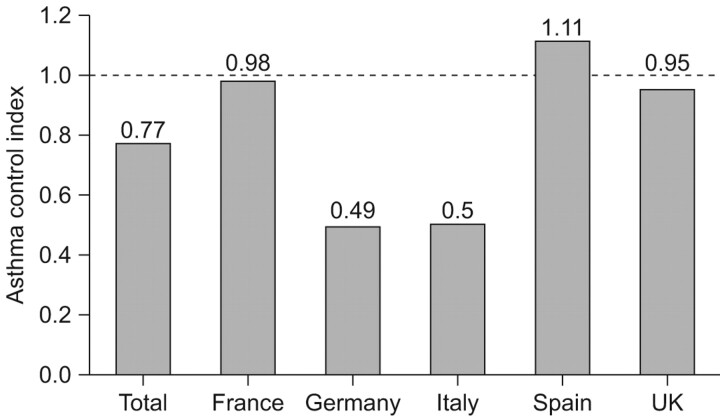

Of the patients with diagnosed asthma, 52.1% were assessed as not well-controlled as measured by the total ACT score. The respondent's own rating of their control in the last 4 weeks (based on one component of the ACT score) concurred with the total ACT score (57.3% rated their asthma as not well-controlled, i.e. “not at all”, “poorly” or “somewhat” controlled) (table 2). Comparing the ACI by country, Spain showed the greatest levels of control (ACI 1.1). The lowest rates of asthma control were found in Germany and Italy (ACI 0.5) (fig. 1).

Table. 2—

Proportion of patients with individual components of the Asthma Control Test™

| Diagnosed asthma | p-value |

|||

| Not well-controlled# |

At least well-controlled¶ |

|||

| Impact of asthma on work, school and home activities in past 4 weeks | <0.001 | |||

| All of the time | 3.4 | 0.1 | ||

| Most of the time | 10.1 | 0.0 | ||

| Some of the time | 27.3 | 1.4 | ||

| A little of the time | 33.7 | 18.7 | ||

| None of the time | 25.4 | 79.8 | ||

| Frequency of shortness of breath in past 4 weeks | <0.001 | |||

| At least once a day | 48.1 | 1.7 | ||

| 3–6 times per week | 24.4 | 3.7 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 25.6 | 47.5 | ||

| None | 1.9 | 47.1 | ||

| Night-time awakenings due to asthma in past 4 weeks | <0.001 | |||

| ≥4 nights per week | 17.0 | 0 | ||

| 2–3 nights per week | 26.4 | 1.3 | ||

| Once a week | 16.9 | 3.3 | ||

| Once or twice per week | 39.8 | 95.4 | ||

| Frequency of rescue medication use | <0.001 | |||

| ≥3 times per day | 14.8 | 0.6 | ||

| Once or twice per day | 38.0 | 7.1 | ||

| 2–3 times per week | 24.6 | 8.2 | ||

| None or once a week | 22.6 | 84.1 | ||

| Self-rated asthma control in past 4 weeks | <0.001 | |||

| Not at all controlled | 11.6 | 4.0 | ||

| Poorly controlled | 10.7 | 1.0 | ||

| Somewhat controlled | 35.0 | 4.7 | ||

| Well-controlled | 37.3 | 36.6 | ||

| Completely controlled | 5.3 | 53.6 | ||

Data are presented as % of patients, unless otherwise stated. #: n = 1,827; ¶: n = 1,792. Statistical comparisons were computed using the Chi-squared test.

FIGURE 1.

Asthma control index. An asthma control index was computed by country as the ratio of at least well-controlled to not well-controlled treated asthma sufferers. An index of >1 equates to a greater proportion of at least well-controlled and an index of <1 equates to a greater proportion of not well-controlled.

Demographics and asthma-specific characteristics

Table 3 summarises the demographics and health characteristics of patients with asthma by control status. Of the patients who were not well-controlled, a significantly higher proportion of them were female, aged >55 yrs, more often unemployed, and more likely to smoke and suffer from obesity compared with patients who had at least well-controlled asthma. The prevalence of self-reported comorbidities, such as depression, anxiety and sleep difficulties, was also significantly higher amongst asthma sufferers with not well-controlled asthma.

Table. 3—

Demographics and health characteristics of subjects with asthma by control status

| Diagnosed asthma | p-value |

|||

| Not well-controlled |

At least well-controlled |

|||

| Subjects n | 1827 | 1792 | ||

| Female | 62.5 | 53.3 | <0.001 | |

| Age yrs | 47.31±15.6 | 42.85±15.7 | <0.001 | |

| Age range yrs | ||||

| 18–34 | 26.6 | 37.2 | ||

| 35–54 | 38.9 | 38.0 | ||

| >55 | 34.6 | 24.8 | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 49.8 | 63.4 | <0.001 | |

| Unemployed | 50.2 | 36.6 | <0.001 | |

| Retired | 22.8 | 16.5 | ||

| On disability | 6.3 | 2.7 | ||

| Overweight# | 33.6 | 35.6 | <0.001 | |

| Obese¶ | 30.4 | 23.3 | <0.001 | |

| Current/ex-smoker | 70.3 | 58.7 | ||

| Experienced the following in past 12 months | ||||

| Depression | 31 | 18 | <0.001 | |

| Anxiety | 40 | 28 | <0.001 | |

| Sleep difficulties | 42 | 35 | <0.001 | |

| Number of times spoken with doctor in last 12 months | 3.15±3.7 | 1.48±1.9 | <0.001 | |

| Asthma treatment | ||||

| Controller medication | 64.7 | 46.2 | <0.001 | |

| Rescue medication | 55.1 | 48.4 | <0.001 | |

| MMAS among those treated for a symptomatic condition | ||||

| 0 (highly adherent) | 36.4 | 35.4 | ns | |

| 1 | 22.1 | 24.5 | ns | |

| 2 | 17.4 | 16.8 | ns | |

| 3 | 13.9 | 16.1 | ns | |

| 4 (highly nonadherent) | 10.1 | 7.3 | 0.016 | |

Data are presented as % or mean±sd, unless otherwise stated. MMAS: Morisky Medication Adherence Scale; ns: nonsignificant. #: body mass index ≥25 kg·m−2 and <30 kg·m−2; ¶: body mass index ≥30 kg·m−2. Statistical comparisons were computed using the Chi-squared test for percentages and unpaired t-tests for means.

Just over half of the asthmatics (55%) had had their asthma diagnosed by a primary care physician. A further 37% were diagnosed by a specialist (pulmonologist or allergist). However, the majority of patients had their asthma medication prescribed by a primary care physician (71%), with 25% having their treatment managed by a specialist. Approximately 60% of patients treated for a symptomatic condition, including asthma, reported good or complete adherence with their medications on the MMAS with no difference based on level of asthma control (at least well-controlled: 60%; not well-controlled: 59%) (table 3). But the proportion of highly non-adherent patients was significantly greater amongst those with not well-controlled asthma compared with those with at least well-controlled asthma.

Individual components of the ACT include: impacts on work, school and home activities; frequency of symptoms including night-time awakenings; and use of rescue medication. Patients with at least well-controlled asthma experienced less activity limitations compared to those with not well-controlled asthma: 0.1% versus 13.5%, respectively, reported that their asthma limited their activities all or most of the time and 1.4% versus 27.3%, respectively, were affected some of the time (p<0.001) (table 2). A large proportion of patients with not well-controlled asthma reported: breathlessness at least once a day (48.1%) or 3–6 times per week (24.4%) compared with 1.7% and 3.7%, respectively, of those with at least well-controlled asthma (p<0.001); had their sleep interrupted ≥2–3 nights per week (43.4% versus 1.3%, p<0.001); and needed to use a rescue medication ≥2–3 times per week (77.4% versus 15.9%, p<0.001).

With respect to healthcare attitudes, patients with well-controlled asthma are more likely to consult a doctor if they do not feel well and to take responsibility for their actions in ensuring that they get well again compared with patients with not well-controlled asthma (table 4). Conversely, not well-controlled asthmatics are more likely to have regular contact with their doctors and to keep their doctors informed about the over-the-counter products they use. Not well-controlled asthma sufferers reported that they would like to take fewer pills and are more aware of the side-effects associated with prescription medications, but they preferred brand name medications to generic ones and were highly regimented in following their drug regimen (adhering to a routine in taking their medications and resistant to a change in that routine) compared to those with at least well-controlled asthma.

Table. 4—

Healthcare attitudes of respondents with asthma by control status

| Agree/strongly agree with statement |

Diagnosed asthma | p-value |

||

| Not well-controlled# |

At least well-controlled¶ |

|||

| Unless there is a good reason to change my medication, I think it is best to continue taking my medication as I currently do | 72.0 | 68.0 | 0.032 | |

| I prefer brand name medications to generic ones | 21.1 | 14.8 | <0.001 | |

| Whenever I don't feel well, I should consult a medically trained professional | 41.7 | 45.8 | 0.04 | |

| If I get sick, it is my own behaviour which determines how soon I get well again | 47.5 | 53.7 | 0.002 | |

| My doctor knows about all the over-the-counter products that I use | 48.0 | 42.7 | 0.009 | |

| I am afraid of needles | 27.0 | 21.2 | <0.001 | |

| All prescription medications have side-effects | 43.3 | 34.8 | <0.001 | |

| I would prefer if my medications were combined into fewer pills | 44.5 | 37.8 | <0.001 | |

| I try to take a multivitamin each day to improve or maintain my health | 27.0 | 21.3 | <0.001 | |

| Having regular contact with my physician is the best way for me to avoid illness | 29.9 | 19.9 | <0.001 | |

| I try to take my medication at the same time every day | 65.2 | 59.7 | 0.005 | |

Data are presented as %, unless otherwise stated. #: n = 1,827; ¶: n = 1,792. Statistical comparisons were computed using the Chi-squared test.

Healthcare resource use

Patients who were not well-controlled visited a traditional medical provider in the past 6 months significantly more than patients who were at least well-controlled (94.6% versus 89.6%; p<0.001) and required more consultations with any traditional healthcare provider (9.9 versus 6.8 mean patient visits; p<0.001) including visits to a general practitioner (80.8% versus 75.8%; p = 0.0038), as well as respiratory specialists (11.4% versus 5.7% visited a pulmonologist; p<0.001) (table 5).

Table. 5—

Health resource use in previous 6 months

| Healthcare resource use |

Diagnosed asthma | p-value |

||

| Not well-controlled |

At least well-controlled |

|||

| Subjects n | 1827 | 1792 | ||

| Visited traditional medical provider | 94.6 | 89.6 | <0.001 | |

| Traditional medical provider visits | 9.92±10.8 | 6.78±6.78 | <0.001 | |

| Visited general/family practitioner | 80.8 | 75.8 | 0.0038 | |

| Visited internist | 9.6 | 5.2 | <0.001 | |

| Visited allergist | 15.6 | 9.6 | <0.001 | |

| Visited pulmonologist | 11.4 | 5.7 | <0.001 | |

| Visited ER | 24.5 | 15.9 | <0.001 | |

| ER visits | 0.6±2.4 | 0.2±0.7 | <0.001 | |

| Hospitalised | 17.4 | 9.9 | <0.001 | |

| Times hospitalised | 0.4±2.8 | 0.2±0.6 | <0.001 | |

Data are presented as % or mean±sd, unless otherwise stated. ER: emergency room. Statistical comparisons were computed using the Chi-squared test for percentages and unpaired t-tests for means.

Patients with asthma who were at least well-controlled had significantly less ER visits compared with those with not well-controlled asthma (15.9% versus 24.5%; mean 0.2 versus 0.6, p<0.001) (table 5). Furthermore, for patients with at least well-controlled asthma the rate of hospitalisation was significantly lower and they had on average been hospitalised half as many times as those with not well-controlled asthma (9.9% versus 17.4% (p<0.001) and 0.2 versus 0.4 times (p<0.001), respectively).

Patient-reported outcomes

WPAI

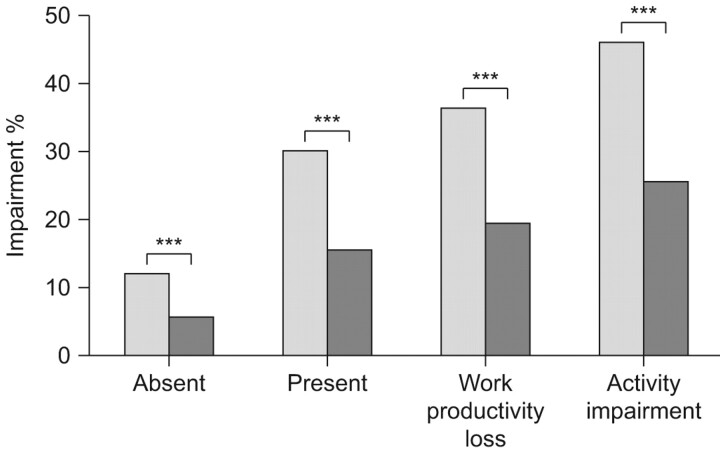

Among asthma sufferers who were employed full-time, there was a significant impact on work productivity for patients with not well-controlled asthma (fig. 2). All WPAI domains were significantly different between groups including absenteeism, presenteeism and total work productivity. Regarding absenteeism, the percentage of work time missed due to health was 12.2% and 5.6% for not well-controlled and at least well-controlled (p<0.001), respectively. Regarding presenteeism, the percentage of impairment due to health while working was respectively 30.0% versus 15.4% for not well-controlled and at least well-controlled (p<0.001), respectively, and the total work productivity impairment was 36.2% versus 19.3% (p<0.001), respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Work productivity and activity impairment by control status. Work productivity impairment considers both absent (time missed from work) and present (impairment while working) results. ░: not well-controlled asthma; ▒: at least well-controlled asthma. Statistical comparisons were computed using the Chi-squared test. ***: p<0.001.

Patients with at least well-controlled asthma also experienced significantly less activity impairment in daily activities than not well-controlled asthmatics (25.3% versus 45.8%; p<0.001).

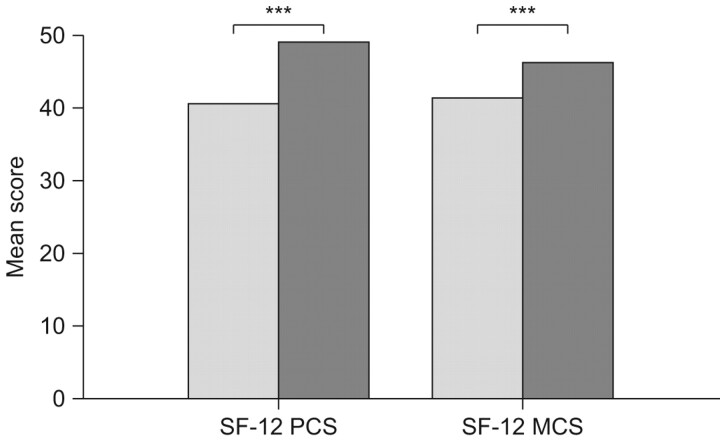

HRQoL

Patients with asthma who were at least well-controlled rated their overall health better than those who were not well-controlled for both the physical and mental components of the SF-12 questionnaire. Patients with at least well-controlled asthma had SF-12 PCS and MCS mean scores greater than patients with not well-controlled asthma. The difference in mean SF-12 scores between controlled and uncontrolled asthmatics was 7.46 points for the SF-12 PCS and 4.73 points for the SF-12 MCS. These differences were both statistically and clinically significant (fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Short-form (SF)-12 mean scores by control status. PCS: physical component score; MCS: mental component score. ░: not well-controlled asthma; ▒: at least well-controlled asthma. Statistical comparisons were computed using the unpaired t-test. ***: p<0.001.

The SF-12 scores are normalised to a mean of 50 for the general population. Patients with at least well-controlled asthma had SF-12 physical and mental summary scores of 48.0 and 46.1, respectively, which were inferior but not much less than the average for the general population. Not well-controlled asthma patients had mean SF-12 physical and mental summary scores of 40.6 and 41.4, respectively, which were significantly poorer than those for at least well-controlled patients (p<0.001) and notably below the average range of 50 meaning a clear deterioration of the quality of life in comparison with the general population.

The results for the individual SF-12 dimension mean scores were consistent with the summary scores. Compared with patients with at least well-controlled asthma, not well-controlled asthmatics experienced significantly poorer physical functioning (41.7 versus 49.1), more pain (40.7 versus 47.1), greater impairment in social activities (39.1 versus 45.6) and poorer emotional health (38.2 versus 45.3) (all p<0.001).

When not well-controlled patients were grouped by the amount of rescue medication they used, those taking rescue medication 2–3 times per week had a similar social and physical burden to those taking it 1–2 times per day (SF-12 physical functioning score: 2–3 times per week: 42.2; 1–2 times per day: 41.9; SF-12 social functioning score: 2–3 times per week: 38.8; 1–2 times per day: 40.0). WPAI scores were also similar between these groups of patients (absenteeism: 2–3 times per week, 10.7%; 1–2 times per day, 12.9%; presenteeism: 2–3 times per week, 28.1%; 1–2 times per day, 30.7%; overall work impairment: 2–3 times per week, 34.1%; 1–2 times per day, 36.8%).

DISCUSSION

The results of this analysis show that the overall prevalence of physician diagnosed asthma in five European countries in 2008 was 6.1%, which is a slight increase on that reported in 2006 (5.8%) [7]. This result was consistent across all participating countries. The proportion of treated patients with not well-controlled asthma has shown no improvement since 2006. The results of this survey indicate that asthma is still a serious public health problem. Although it is possible to achieve and maintain clinical control in the majority of asthma patients [15], and despite the emphasis placed on achieving asthma control in recent guidelines, together with the endorsement that the clinical manifestations of asthma (symptoms, sleep disturbances, impairment of lung function and use of rescue medications) can be controlled with appropriate treatment [14], a large proportion of asthmatics are still failing to achieve good control. Almost half of the asthmatics in the current survey had their asthma diagnosed by a primary care physician but interestingly, primary care physicians were responsible for treating almost three quarters of all asthma sufferers. Therefore, the main burden of treating asthma appears to fall to the primary care physician. Recent surveys in general practice have reported similar levels of uncontrolled asthma as the current findings (ranging from 55% to 59%). highlighting the need for more effective assessment of asthma control in general practice [16–18]. A problem for physicians is that patients often underestimate their symptoms and overestimate their level of control [6]. However, over three quarters of patients with not well-controlled asthma were taking rescue medication ≥2 times per week which is a recognised sign of uncontrolled asthma [1] and would be a good indicator to use for monitoring the level of asthma control in general practice. Primary care physicians also have the advantage of being responsible for the complete welfare of a patient and, therefore, may monitor other health characteristics such as comorbidities, weight, smoking habits and employment status; all of which were related to level of asthma control.

Results from this survey have shown that, compared to patients with at least well-controlled asthma, having not well-controlled asthma is associated with a significant burden for patients and on healthcare systems. Patients with not well-controlled asthma attended more medical provider visits and, in the previous 6 months, visited the ER and were hospitalised significantly more than those with at least well-controlled asthma, which concurs with the 2006 survey [7]. Poorly controlled asthma was also shown to have a significant impact on WPAI. At least well-controlled patients reported 6.6% less absences from work, 15% less impairment at work and 16.9% less work productivity loss. These percentages equate to a gain of 2.6 h, 6 h and 6.7 h, respectively, in a 40-h working week for patients with at least well-controlled asthma [19]. Previous studies have also found significant direct and indirect costs associated with poorly controlled asthma [20, 21]. The Hunair study [20] assessed 378 paediatric and 711 adult asthma patients in Hungary and found patients with poor asthma control had a significantly higher number of ER/hospital visits and general practitioner visits compared to patients with moderate or good control. This study also showed that patients with, or parents of patients with, good asthma control missed significantly fewer work days compared with those with moderate or poor control. They concluded that improving patient control could reduce the cost to society by ≥40%. Accordini et al. [21] also reported substantial asthma-related costs in 527 Italian patients, largely driven by indirect costs, such as effects on work productivity, and reported that poorly controlled asthmatics accounted for proportionately much higher costs compared to patients with good control.

Having not well-controlled asthma was also associated with a significant impact on HRQoL as assessed by the SF-12 questionnaire. Mean SF-12 scores in at least well-controlled asthmatics approached general population norms and those observed in a recent Dutch sample of the general population [22], whereas those scores for patients with uncontrolled asthma were markedly lower than normative values. The differences in physical and mental component scores, as well as the individual dimensions, between the groups with at least well-controlled and not well-controlled asthma also exceeded the pre-defined minimum clinically important difference. These findings are in agreement with a previous study in which asthma control showed highly significant cross-sectional associations with HRQoL, including generic HRQoL as assessed by SF-36 [23]. In addition, Pont et al. [24] showed that asthma patients treated according to international treatment guidelines had significantly higher overall HRQoL than patients with non-guideline treatment.

The results of the current survey show that having at least well-controlled asthma is associated with a significant and positive impact on healthcare resource use, as well as on a patient's own productivity. Patients with at least well-controlled asthma also experienced a better HRQoL enabling them to perform physical activities more easily, such as doing housework or playing sport, to engage in social activities more readily and for their asthma to have much less impact on them emotionally. Even not well-controlled patients who use rescue medication only 2–3 times per week experience significant impairment in their productivity and HRQoL, similar to that experienced by patients using daily rescue medication. This highlights the importance of regularly assessing a patient's level of rescue use as an indicator of asthma control and suggests that patients using rescue medication starting from ≥2 times per week warrant a re-evaluation of their treatment.

There are limitations to this type of survey. First, respondents completing the survey were required to have internet access and, therefore, do not fully represent the general population in each country. To overcome such bias, the NHWS sampling frame ensured a representative demographic sample from each county in terms of age and sex. Secondly, all outcomes were self-reported by the patients without any subsequent clinical verification. However, the results for asthma prevalence are consistent with previous reports [2] and the self-reported questionnaires used have all been previously validated. Finally, observations from this survey should be interpreted with full consideration to its cross-sectional nature and, thus, cause and effect relationships cannot be established.

In conclusion, the results of the 2008 NHWS show that the proportion of treated asthmatics with uncontrolled asthma has shown no improvement since 2006. Having at least well-controlled asthma is associated with a significant positive impact on healthcare resource use, HRQoL and work productivity. Healthcare practitioners play a key role in identifying patients with uncontrolled asthma as early as possible, facilitating the achievement and maintenance of guideline-defined asthma control through treatment review and helping patients to be symptom-free with minimum rescue medication use.

Statement of interest

B. Gueron, L. Adamek and R.D. Walters are all employees of GlaxoSmithKline. L. Adamek and R.D. Walters also have shares in GlaxoSmithKline.

Provenance

Publication of this peer-reviewed article was supported by GlaxoSmithKline, France (article sponsor, European Respiratory Review issue 116).

Acknowledgments

Editorial support in the form of developing a draft outline and first draft, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, and referencing was provided by K. Hollingworth (Livewire Communications, Gerrards Cross, UK) and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

References

- 1.Global initiative for asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2009 update. www.ginasthma.com/Guidelineitem.asp?l152&l251&intId

- 2.Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, et al. The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee Report. Allergy 2004; 59: 469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahadori K, Doyle-Waters MM, Marra C, et al. Economic burden of asthma: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med 2009; 9: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, 2007. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.pdf

- 5.Rabe KF, Adachi M, Lai C, et al. Worldwide severity and control of asthma in children and adults. The global Asthma and Insights and Reality surveys. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 114: 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabe KF, Vermeire PA, Soriano JB, et al. Clinical management of asthma in 1999: the Asthma Insights and Reality in Europe (AIRE) study. Eur Respir J 2000; 16: 802–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demoly P, Paggiaro P, Plaza V, et al. Prevalence of asthma control among adults in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK. Eur Respir Rev 2009; 18: 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care 1986; 24: 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993; 4: 353–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996; 34: 220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kontodimopoulos N, Pappa E, Niakas D, et al. Validity of SF-12 summary scores in a Greek general population. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007; 5: 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samsa G, Edelman D, Rothman ML, et al. Determining clinically important differences in health status measures. A general approach with illustration to the health utilities index mark II. Pharmacoeconomics 1999; 15: 141–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Census Bureau. International database (IDB). www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/

- 15.Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, et al. Can guideline-asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma Control Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 170: 836–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mintz M, Gilsenan AW, Bui CL, et al. Assessment of asthma control in primary care. Curr Med Res Opin 2009; 25: 2423–2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters SP, Jones CA, Haselkorn T, et al. Real-world evaluation of asthma control and treatment (REACT): findings from a national web-based survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 119: 1454–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman KR, Boulet LP, Rea RM, et al. Suboptimal asthma control: prevalence, detection and consequences in general practice. Eur Respir J 2008; 31: 320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubois RW, Aguilar D, Fass R, et al. Consequences of frequent nocturnal gastro-oesophageal reflux disease among employed adults: symptom severity, quality of life and work productivity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25: 487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herjavecz I, Nagy GB, Gyurkovits K, et al. Cost, morbidity, and control of asthma in Hungary: The Hunair study. J Asthma 2003; 40: 673–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Accordini S, Bugiani M, Arossa W, et al. Poor control increases the economic cost of asthma. A multicentre population-based study. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2006; 141: 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mols F, Pelle AJ, Kupper N. Normative data of the SF-12 health survey with validation using post myocardial infarction patients in the Dutch population. Qual Life Res 2009; 18: 403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vollmer W, Markson LE, O'Connor E, et al. Association of asthma control with healthcare utilisation and quality of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160: 1647–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pont LG, van der Molen T, Denig P, et al. Relationship between guideline treatment and health-related quality of life in asthma. Eur Respir J 2004; 23: 718–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]