Abstract

Peptides derived from the surface glycoprotein gp82 of Trypanosoma cruzi, previously implicated in the parasite’s invasion of host cells, were expressed as fusions to the protein LamB of Escherichia coli in a region known to be exposed on the cell surface. Bacteria expressing these proteins adhered to HeLa cells in a manner that mimics the pattern of parasite invasion of mammalian cells. Purified LamB fusion proteins were shown to bind to HeLa cells and to inhibit infection by T. cruzi, supporting the notion that these gp82-derived peptides can mediate interaction of the parasite with its host.

LamB is a 421-amino-acid, trimeric, integral, outer membrane protein of Escherichia coli involved in the permeation of maltose and maltotriose and required for the transport of high-er dextrins (9). In addition, LamB acts as a cell surface receptor for a variety of bacteriophages, including phage lambda. The X-ray structure of LamB revealed an 18-stranded antiparallel β barrel that forms the channel through which the sugar molecules slide (14). The strands are connected to each other on the cell exterior surface of the barrel by long unstructured loops. Three of these loops form large protusions on the cell surface. One of them, L4, spanning amino acid residues 149 to 166, harbors point mutations that render cells resistant to bacteriophage lambda and has been used as a site for insertions of several foreign sequences without disruption of the proper protein structure, localization, or ability to form trimers (2, 4). Furthermore, these foreign sequences are exposed on the cell surface, as determined by their accessibility to antibodies.

Taken together, these data suggested that peptide sequences with specific receptors on the surface of eukaryotic cells, when inserted in the L4 loop of LamB, are sufficiently exposed on the bacterial cell surface so as to mediate bacterial adhesion to cultured cell monolayers. In this work, this system was employed in the study of a surface glycoprotein of Trypanosoma cruzi.

T. cruzi is the causative agent of Chagas’ disease, which affects 16 to 18 million individuals in Central and South America (17). Invasion of host cells by metacyclic trypomastigotes, the T. cruzi developmental forms that initiate infection in the mammalian host, requires a set of parasite surface molecules, one of which is the 82-kDa glycoprotein (gp82) (11, 12). gp82 is expressed exclusively by the metacyclic trypomastigote stage (1, 16) and seems to play a central role in parasite penetration into target cells through a receptor-mediated pathway. Invasion of cultured HeLa cells by metacyclic trypomastigotes is inhibited by about 80% in the presence of the native gp82 or a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-gp82 fusion protein (13). The latter observation also indicates that the peptide portion of gp82, comprising 516 amino acid residues, rather than its sugar moiety, is involved in the interaction of this molecule with target cells. Purified gp82, native or recombinant, triggers an increase in intracellular concentration of Ca2+ in HeLa cells (5) and induces parasite protein tyrosine kinase activity (6), events required for T. cruzi invasion.

Purified truncated recombinant proteins and synthetic peptides containing sequences derived from gp82 have been used to identify the domain(s) of this molecule which is recognized by host cell receptors. The results of this analysis suggest that the central domain of gp82 (amino acid residues 224 to 356) mediates the interaction with host cells. Invasion of HeLa cells was not affected by any of the GST fusion proteins lacking the referred sequence, whereas an inhibition of 65% was observed in the presence of a construct containing amino acids 224 to 356 (13). Synthetic peptides spanning residues 254 to 273 (P4) and residues 294 to 313 (P8) have significant inhibitory activity on HeLa cell invasion by metacyclic forms (13). These results indicate that the portion of gp82 required for mammalian cell attachment and invasion is located in the central part of the molecule. However, because the GST fusion proteins were highly insoluble, this inhibitory activity might not reflect the in vivo situation. The use of peptides in the inhibition assays is also prone to conformational problems. Therefore, the use of the LamB expression system to mediate adhesion of bacteria through receptor-ligand interaction might provide an additional method with which to study surface protein interactions and, more importantly, to define sequence sufficiency.

Expression of LamB recombinant proteins.

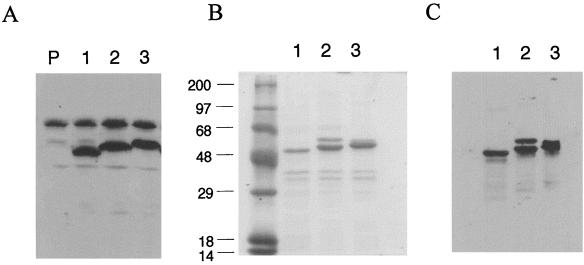

In this work, two peptides derived from the central domain of T. cruzi gp82 surface protein, named P4 (LARLTEELKTIKSVLSTWSK) and P8 (NSASGDAWIDDYRSVNAKVM), were expressed on the surface of E. coli cells as fusions to LamB. The gp82-derived peptides were fused to LamB between residues Ser-153 and Ser-154, in the L4 loop. Complementary oligonucleotide pairs corresponding to the sequences of gp82 (GenBank accession no. L14824 deposited by Araya et al. [1]) (P4 coding strand: 5′-GATCCACTTGCCCGCCTGACCGAGGAGCTG AAGACGATGAAGTCCGTCCTCAGCACTTGGTCAA AGAAT3′; P8 coding strand: 5′-GATCCAAATTCGGCCAGCGGTGACGCGTGGATCGACGATTACCGTTCCGTGAATGCAAGGTCATGAAT-3′) were inserted into the BamHI site of plasmid pAJC264 (2), which carries the lamB gene under the control of the tac promoter (a kind gift of M. Hofnung, Institute Pasteur, Paris, France). The ligation reactions were used to transform strain POP6510 (thr leu tonB thi lacYi recA dex-5 metA supE) to ampicillin resistance, the plasmids containing the insertions were isolated, and the inserts were sequenced to ascertain their correctness. The expression of the recombinant LamB proteins was determined by immunoblots of whole-cell extracts of bacteria after induction with 10−3 M IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Both constructions were recognized by antisera raised against LamB, as indicated by the presence of bands with the expected molecular mass slightly above the 48-kDa of the wild-type LamB (Fig. 1A). The recombinant proteins were expressed at approximately the same levels as the wild-type.

FIG. 1.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins. (A) Immunoblot of whole-cell extracts of E. coli expressing the wild-type LamB (lane 1), LamB-P4 (lane 2), and LamB-P8 (lane 3) recombinant proteins, reacted with an antiserum raised against LamB. The strain POP6510 was used as a negative control (lane P). (B) Coomassie blue staining of sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel of the purified wild-type and recombinant LamB proteins. Molecular mass standards are indicated on the left, in kilodaltons. (C) Immunoblot of the purified LamB proteins with anti-LamB antibodies.

Bacterial adhesion to HeLa cells.

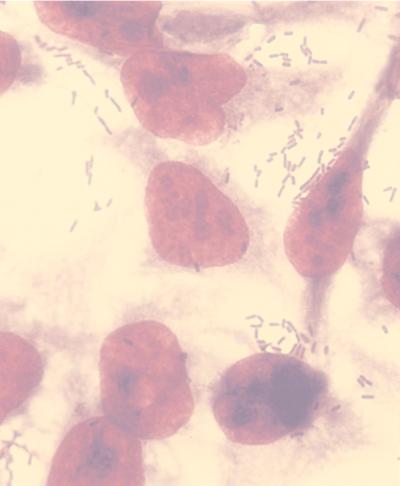

E. coli cells expressing the LamB-P4 and LamB-P8 fusion proteins were tested for their ability to adhere to HeLa cells. E. coli expressing the wild-type LamB and a construction containing an unrelated T. cruzi sequence (LamB-B13) inserted in the same site of the L4 loop (10) were used as negative controls. The latter control was used in order to rule out a possible influence of the alteration in the conformation of the L4 loop, due to the insertion of a foreign sequence, on the binding of bacteria to the human cells. Bacteria expressing LamB-P4 and LamB-P8 were capable of binding to HeLa cells, at levels that are statistically significant compared to those of the two negative controls (Table 1). Bacteria expressing LamB-P4 were apparently more efficient in binding to cells than those expressing LamB-P8. In both cases, bacteria were not randomly distributed over the cell surface but were concentrated on the borders of the HeLa cells and on their remnants after fixation, as shown in Fig. 2 for E. coli expressing LamB-P4. This suggests the existence of preferential areas where HeLa cells could have more receptors for gp82.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial adhesion to HeLa cells

| E. coli strain | Adhesion indexa (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| POP6510/LamB | 0.28 ± 0.11 |

| POP6510/LamB-B13 | 0.30 ± 0.16 |

| POP6510/LamB-P4 | 1.53 ± 0.25 |

| POP6510/LamB-P8 | 0.82 ± 0.14 |

The adhesion index is the mean number of bacteria per cell, as determined by examination of 100 cells. Each number represents the results of four separate experiments. The differences in the mean values between POP6510/LamB-P4 or POP6510/LamB-P8 and the controls are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

FIG. 2.

E. coli adhesion to HeLa cells. E. coli suspensions of 108 cells expressing the different LamB recombinant proteins were incubated with HeLa cells (5 × 104) in the presence of 1% d-mannose, for 3 h at 37°C in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After extensive washing in sterile phosphate-buffered saline, the cells were fixed with methanol, stained with Giemsa, and examined microscopically under oil immersion at a magnification of ×1,000.

Binding of purified recombinant proteins to HeLa cells.

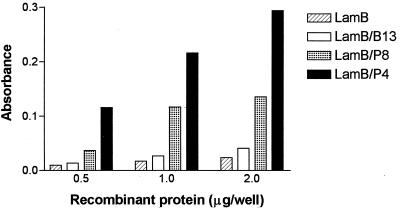

To ascertain that the adhesion of bacteria was mediated through the gp82 fragments present in LamB, the purified recombinant proteins were used in binding assays. The LamB proteins were purified from E. coli as outer membrane components (7) (Fig. 1B). In these preparations, LamB and the recombinant derivatives were the major components, and proteins of lower molecular weight were present in the same amounts in the three cases. The two bands of approximately 50 kDa, detected by Coomassie blue staining in the preparations of LamB-P4 and LamB-P8, reacted with serum directed to LamB (Fig. 1C), indicating that they might represent the precursor form of LamB. The binding of these purified proteins to HeLa cells was determined in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using anti-LamB antibodies. As shown in Fig. 3, LamB-P4 and LamB-P8 bound to HeLa cells in a dose-dependent fashion. These data give further support to the argument that the E. coli adhesion results from the interaction of P4 and P8 with a receptor on HeLa cells. Purified wild-type LamB and LamB-B13 showed only a basal level of binding (Fig. 3). In this assay, LamB-P4 displayed a better binding capacity, reflecting the in vivo adhesion study.

FIG. 3.

Binding of recombinant proteins to HeLa cells. Various concentrations of wild-type and recombinant LamB proteins were added to wells in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plates containing HeLa cells fixed with paraformaldehyde. After washes, cells were incubated with antibodies against LamB and with anti-mouse immunoglobulin G conjugated with peroxidase. The reactions were developed with o-phenylenediamine as the substrate. The results show one of three independent experiments, expressed as means of triplicates. Standard deviations were never greater than 10% above or below the mean. The differences between LamB-P4 or LamB-P8 and the controls LamB and LamB-B13 are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Effect of recombinant LamB proteins on parasite invasion.

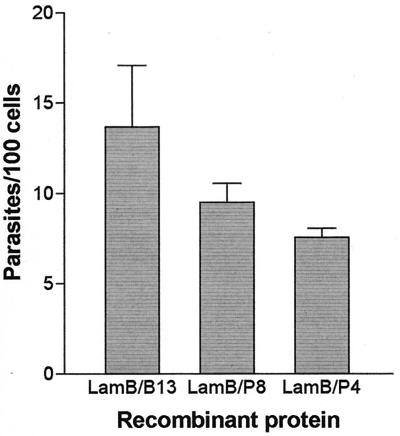

Purified LamB-P4 and LamB-P8 were also assayed for their capacity to inhibit the invasion of HeLa cells by T. cruzi (Fig. 4). T. cruzi invasion assays were performed as described previously (18). Invasion of HeLa cells preincubated with purified LamB-P4 or LamB-P8 was significantly reduced compared to the control, in which the cells were preincubated with the LamB-B13 protein. LamB-P4 displayed a stronger inhibitory activity than LamB-P8, reflecting both the higher adhesion index displayed by bacteria expressing this fusion protein and the protein binding data.

FIG. 4.

Inhibitory effect of recombinant LamB proteins on T. cruzi entry into host cells. Metacyclic trypomastigotes were added to HeLa cells previously incubated with LamB-B13, LamB-P4, or LamB-P8 proteins (50 μg/well) for 3 h at 37°C. The rate of invasion was determined by counting the number of intracellular parasites in 500 cells stained with Giemsa. Values are means + standard deviations (error bars) of two experiments performed in duplicate. The differences between the values obtained for LamB-P4 or LamB-P8 and for the control LamB-B13 are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

We described here the use of LamB as a carrier of T. cruzi-derived peptides in order to obtain direct in vivo evidence of their role in host cell receptor recognition. The results shown here indicate that the two segments of the metacyclic trypomastigote surface molecule gp82, namely, P4 and P8, are sufficient to mediate a receptor-specific adhesion to host cells. The results obtained with the purified LamB proteins corroborate previous data obtained with synthetic peptides, corresponding to P4 and P8, where partial inhibition of HeLa cell invasion by metacyclic trypomastigotes was seen (13). This was expected since complete inhibition was not obtained even when the native gp82 was present, which is consistent with the notion that the interaction of the parasite with the target cells involves other molecules besides gp82 (11).

Bacterial adhesion mediated by P4 and P8 provides direct evidence of the role of these sequences in the recognition and binding of the gp82 molecule to host cells. It is of note that bacteria were not randomly distributed over the monolayer but were concentrated on the borders of HeLa cells. This pattern of interaction mimics the attachment of T. cruzi trypomastigotes to HeLa cells during invasion, which occurs preferentially at the edges (8). The bacteria carrying P4 seemed to bind more efficiently to cells than those carrying P8. In addition, the purified LamB-P4 protein showed both a higher binding to HeLa cells and greater inhibitory activity on parasite invasion. Significantly, purified LamB-P4 induced in HeLa cells a greater increase in intracellular calcium concentration than did LamB-P8 (unpublished data). Thus, it is likely that the P4 sequence comprises residues that are more directly involved in maintaining an interaction with the receptor on the eukaryotic cells. Alternatively, if both sequences are equally relevant for this recognition, the conformation that P4 assumes on the surface of bacteria could be more easily accommodated by the receptor. In both cases, however, the theoretical structural model predicts their exposure on the surface in an unconstrained mode (data not shown).

This work shows that fusions to LamB may provide a useful method to identify domains in molecules involved in recognition of host cells, overcoming obstacles inherent to the use of synthetic peptides, such as insolubility and conformational variations. The fact that the site for insertions in LamB is part of a nonstructured loop provides the possibility for the heterologous sequence to be exposed on the surface of the cell and to take on a conformation that mimics its own in the native protein. In addition, adhesion can be used as a selective method for the identification of interacting molecules, since bacterial cells that do not bind to a receptor can be readily washed from the monolayer and those carrying the binding sequence can be recovered by plating. Large numbers of bacterial cells can be added to cell monolayers, so that selection can be applied in theory to large libraries of random sequences. It has been shown that this site on LamB permits the insertion of large segments with a wide variety of amino acid sequences, with the largest sequence tested being 65 residues long, and this was shown not to interfere with the normal localization or conformation of LamB (3, 15). Thus, the displaying of peptides on the surface of bacterial cells mediated by LamB may represent a very versatile model for the study of surface protein interactions in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Salete Newton and Phillip Klebba for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by FAPESP. C.M.P. and S.F. were supported by CNPq fellowships.

REFERENCES

- 1.Araya J E, Cano M I, Yoshida N, Franco da Silveira J. Cloning and characterization of a gene for the stage-specific 82-kDa surface antigen of metacyclic trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;65:161–169. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulain J C, Charbit A, Hofnung M. Mutagenesis by random linker insertion into the lamB gene of Escherichia coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;205:339–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00430448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charbit A, Molla A, Saurin W, Hofnung M. Versatility of a vector for expressing foreign polypeptides at the surface of Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1988;70:181–189. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charbit A, Ronco J, Michel V, Werts C, Hofnung M. Permissive sites and topology of an outer membrane protein with a reporter epitope. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:262–275. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.262-275.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorta M L, Ferreira A T, Oshiro M E M, Yoshida N. Ca+2 signal induced by Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclic trypomastigote surface molecules implicated in mammalian cell invasion. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;73:285–289. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)00123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Favoreto S, Jr, Dorta M L, Yoshida N. Trypanosoma cruzi 175-kDa protein tyrosine phosphorylation is associated with host cell invasion. Exp Parasitol. 1998;89:188–194. doi: 10.1006/expr.1998.4285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filip C, Fletcher G, Wulff J, Earhart C. Solubilization of the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli by the ionic detergent sodium-lauryl sarcosinate. J Bacteriol. 1973;115:712–722. doi: 10.1128/jb.115.3.717-722.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortara R A. Trypanosoma cruzi: amastigotes and trypomastigotes interact with different structures on the surface of HeLa cells. Exp Parasitol. 1991;73:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(91)90002-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikaido H, Vaara M. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:1–32. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.1-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pereira C M, Yamauchi L M, Levin M J, Franco da Silveira J, Castilho B A. Mapping of B cell epitopes in an immunodominant antigen of Trypanosoma cruzi using fusions to the Escherichia coli LamB protein. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;164:125–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramirez M I, Ruiz R C, Araya J E, Franco da Silveira J, Yoshida N. Involvement of the stage-specific 82-kilodalton adhesion molecule of Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclic trypomastigotes in host cell invasion. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3636–3641. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3636-3641.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiz R C, Favoreto S, Jr, Dorta M L, Oshiro M E M, Ferreira A T, Manque P M, Yoshida N. Infectivity of Trypanosoma cruzi strains is associated with differential expression of surface glycoproteins with differential Ca2+ signaling activity. Biochem J. 1998;330:505–511. doi: 10.1042/bj3300505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santori F R, Dorta M L, Juliano L, Juliano M A, Franco da Silveira J, Ruiz R C, Yoshida N. Identification of a domain of Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclic trypomastigote surface molecule gp82 required for attachment and invasion of mammalian cells. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;78:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02626-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schirmer T, Keller T A, Wang Y, Rosenbusch J P. Structural basis for sugar translocation through maltoporin channels at 3.1 A resolution. Science. 1995;267:512–514. doi: 10.1126/science.7824948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sousa C, Kotrba P, Ruml T, Cebolla A, De Lorenzo V. Metalloadsorption by Escherichia coli cells displaying yeast and mammalian metallothioneins anchored to the outer membrane protein LamB. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2280–2284. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2280-2284.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teixeira M M G, Yoshida N. Stage-specific surface antigens of metacyclic trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi identified by monoclonal antibodies. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1986;18:271–282. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(86)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Fighting disease. Fostering development. The World Health Report 1996. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1996. p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshida N, Mortara R A, Araguth M F, Gonzalez J C, Russo M. Metacyclic neutralizing effect of monoclonal antibody 10D8 directed to the 35- and 50-kilodalton surface glycoconjugates of Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1663–1667. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.6.1663-1667.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]