Abstract

Mycobacterium avium is an intracellular pathogen that has been shown to invade macrophages by using complement receptors in vitro, but mycobacteria released from one cell can enter a second macrophage by using receptors different from complement receptors. Infection of CD18 (β2 integrin) knockout mice and the C57 BL/6 control mice led to comparable levels of tissue infection at 1 day, 2 days, 1 week, and 3 weeks following administration of bacteria. A histopathological study revealed similar granulomatous lesions in the two mouse strains, with comparable numbers of organisms. In addition, transmission electron microscopy of spleen tissues from both strains of mice showed bacteria inside macrophages. Our in vivo findings support the hypothesis that M. avium in the host is likely to use receptors other than CR3 and CR4 receptors to enter macrophages with increased efficiency.

Mycobacterium avium is an intracellular pathogen that in the host main infects mononuclear phagocytes (8, 14). Intracellular pathogens such as mycobacteria have evolved sophisticated mechanisms allowing them to actively enter phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells and to survive in the intracellular environment.

A number of studies have concentrated on gaining an understanding of the mechanisms used by mycobacteria to enter phagocytes—more specifically, monocytes and macrophages. Schlesinger and colleagues (21) first noted that Mycobacterium tuberculosis uses complement receptors on the surface of macrophages, both in the presence and in the absence of serum, to gain access to the intracellular milieu. CR1, as well as CR3 and CR4 (both of which are β2 integrins), has been shown to bind and internalize mycobacteria (9, 13, 23). Similar findings were observed with M. avium, and in addition it was shown that M. avium also recognizes the mannose receptor (a monomeric transmembrane protein) on the macrophage surface (5). More recently, an additional mechanism of entry has been described by Schorey and colleagues (22), who suggested that pathogenic mycobacteria recruit the complement fragment C2a to form a C3 convertase and generate active C3b. Other pathways of mycobacterial uptake into macrophages have been described and include CD14 molecules (18), surfactant protein receptors in the lung (12), and scavenger receptors (25).

The particular reason why mycobacteria are able to bind to and invade cells via so many receptors is unknown. This may represent different strategies, adapted to diverse environments, with the expression of particular ligands in a specific site or the ability to enter mononuclear phagocytes in different stages of maturation.

We recently have shown that M. avium grown within macrophages, when released from the infected cell, seems to use noncomplement receptors to enter a second macrophage (2). Therefore, it is plausible to hypothesize that this strategy is the one used by the bacterium in vivo after it exits macrophages undergoing either necrosis or apoptosis (2).

In this study, we attempted to investigate one step further, i.e., determine whether M. avium requires (or uses) CR3 and CR4 to infect macrophages in vivo, by using CD18 knockout (KO) mice.

M. avium 101 was isolated from the blood of an AIDS patient. Bacteria were cultured on Middlebrook 7H11 agar supplemented with oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, and catalase (OADC) for 10 days, and then transparent colonies were harvested, transferred to 20 ml of 7H9 broth with OADC, and allowed to grow for an additional 5 days. Bacteria were spun down, washed with Hanks’ balanced salt solution, and resuspended in Hanks’ balanced salt solution. The bacteria in the final suspension were dispersed by passing them through an 18-gauge needle 10 times, and then the suspension was placed in a 15-ml plastic tube for 5 min and the top 1 ml was removed and used. The suspension was subsequently adjusted to contain 108 bacteria by using a McFarland turbidimetric standard as previously described (2). The inoculum was stained by using the LIVE and DEAD kit as described below and examined by light microscopy to ensure dispersion of the bacteria. This procedure ensures a disperse inoculum. The number of bacteria in the inoculum was also quantitated by plating on 7H10 agar. The viability of the bacterial inoculum was determined by using the LIVE and DEAD assay (Molecular Probes, Portland, Oreg.) as previously reported (2). Cell suspensions used in the assays were approximately 90% viable.

Female C57 BL/6J-Itg B2 (CD18 KO) mice and C57 BL/6J (wild-type) controls were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). Mice were used when they were 8 weeks old and approximately 20 g of weight.

Recombinant murine gamma interferon (IFN-γ) was kindly provided by Genentech (South San Francisco, Calif.). It had an activity of 3 × 107 U/mg of protein.

To stain for CD18, peritoneal macrophages were obtained as previously described (4, 6), seeded at a density of 105 cells per Lab-Tek slide chamber (Nunc, Naperville, Ill.), and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h. After being washed, the cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD11b and FITC–rat anti-mouse CD18 (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) for 1 h at room temperature. Monolayers were then washed three times, mounted, and observed under a light microscope (Nikon, Japan). As a negative control we used A549 lung epithelial cells (American Type Tissue Collection) (1).

Mice (15 mice per group and per time point) were infected with 107 (for mice harvested at 1 and 3 weeks) or 1.1 × 106 (for mice harvested at 1 and 2 days) bacteria in a 100-μl volume via the lateral tail vein. Different groups of mice were harvested at 1 day, 2 days, 1 week, and 3 weeks postinfection. The blood, liver, and spleen were removed aseptically at the appropriate time point as previously described (4). Briefly, organs were weighed and then homogenized in 5 ml of Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco). Serial 10-fold dilutions were plated in duplicate on Middlebrook 7H10 agar supplemented with OADC. After incubation of the plates for 10 to 14 days at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, colonies were counted and the numbers of CFU per organ were determined (4). The experiments were repeated twice.

Spleens from three C57 BL/6 controls and three CD18 KO mice were harvested at 1 and 3 weeks. Spleens were then cut into small pieces and placed in 10% formalin for fixation. Sections of 5 μm thickness from paraffin blocks were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or by the Ziehl-Nielsen method for the detection of acid-fast bacteria.

To determine the location of M. avium in the tissue (i.e., within macrophages or in other cells), mice were infected as described above and after 1 or 3 weeks, spleens were harvested, fixed, and postfixed as previously described (16). Electron microscopy was not use for quantitation of bacteria in the spleen.

Analysis of variance was used to determine the significance of the difference in the numbers of viable organisms recovered from the spleen and liver. Experiments were repeated twice. Data were considered statistically significant at P values of <0.05.

To evaluate the expression of CR3 (CD11b/CD18) on the surface of peritoneal macrophages, FITC-labeled anti-CD11b and anti-CD18 were used. In some assays, cells were seeded for 24 h in the presence of recombinant murine IFN-γ. While treatment with IFN-γ induced the expression of both CD11b and CD18 on macrophages of C57 BL/6 control mice anywhere from mildly to highly, it had no effect on the lack of expression of CD11b and CD18 on macrophages of CD18 KO mice. No staining of CR3 was seen in A549 lung epithelial cells.

Based on the assumption that the CR3 receptor is important for the uptake of M. avium by macrophages in vivo, one would presume that the bacterial load would be significantly higher in C57 BL/6 mice than in CD18 KO mice. As shown in Table 1, however, the two strains of mice exhibited comparable degrees of infection of the liver and spleen both early after infection (1 and 2 days) and late after infection (1 and 3 weeks).

TABLE 1.

Number of M. avium in livers and spleens of C57 BL/6 (wild-type) and Itg B2 (CD18 KO) mice at several time points after infection

| Mouse strain | Time points postinfection (days)a | CFU/g of organb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Spleen | ||

| C57 BL/6 | 1 | 1.8 × 108 ± 0.1 × 108 | 8.4 × 107 ± 0.2 × 107 |

| 2 | 2.3 × 108 ± 0.1 × 108 | 1.1 × 108 ± 0.2 × 108 | |

| 7 | 1.6 × 108 ± 0.5 × 108 | 1.4 × 108 ± 0.3 × 108 | |

| 14 | 1.2 × 108 ± 0.2 × 108 | 4.7 × 108 ± 0.4 × 108 | |

| Itg B2 | 1 | 1.8 × 108 ± 0.3 × 108 | 8.2 × 107 ± 0.1 × 107 |

| 2 | 2.1 × 108 ± 0.2 × 108 | 1.4 × 108 ± 0.2 × 108 | |

| 7 | 1.6 × 108 ± 0.3 × 108 | 7.5 × 107 ± 1.4 × 107 | |

| 14 | 1.9 × 108 ± 0.3 × 108 | 3.5 × 108 ± 0.5 × 108 | |

Mice used for 1- and 2-day time points were infected with 107 bacteria via the tail vein; mice used for 7- and 14-day time points were infected with 106 bacteria via the tail vein.

Results represent means ± standard deviations of data for 15 mice/group/time point. P > 0.05 for all comparisons between the numbers of bacteria in the livers and spleens of wild-type and KO mice at the same time point.

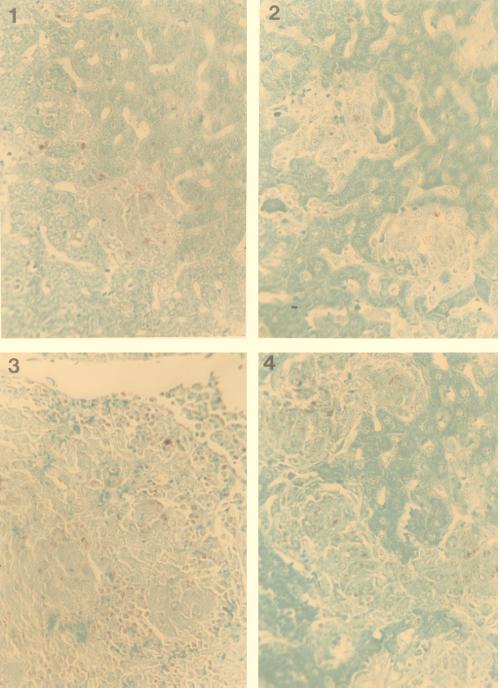

Since it was possible that M. avium would infect other cells upon failing to enter macrophages (although one would not expect the rate of intracellular growth to be similar to that achieved in macrophages), we performed histopathological studies to determine the location of the bacteria. As shown in Fig. 1, granulomas in the spleens of both C57 BL/6 and CD18 KO mice appeared morphologically similar at 1 and 3 weeks. In addition, the numbers of bacteria observed in the granulomas of the two mouse strains appeared to be comparable (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Histopathology of mouse spleens, stained for acid-fast bacilli, from CD18 KO mice (panels 1 and 3) and C57 BL/6 (panels 2 and 4). Granulomatous lesions containing mycobacteria and epithelioid cells can be observed. Spleens were obtained 1 week (panels 1 and 2) and 3 weeks (panels 3 and 4) after infection.

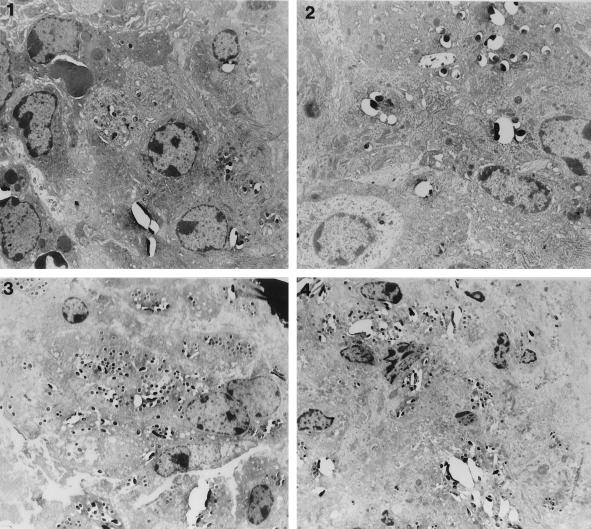

Electron micrographs obtained at 1 and 3 weeks following infection showed that bacteria in the spleen were contained within macrophages in both C57 BL/6 and CD18 KO mice (Fig. 2) but not in another type of cell (data not shown). There was no attempt to use the electron micrographs to quantitate intracellular bacteria.

FIG. 2.

Electron micrographs of the spleens of CD18 KO mice (panels 1 and 3) and C57 BL/6 mice (panels 2 and 4). Panels 1 and 2 were obtained at 1 week postinfection; panels 3 and 4 were obtained at 3 weeks postinfection. Bacteria are seen within macrophage vacuoles in all examples.

Our data show that M. avium infection of both wild-type C57 BL/6 mice and CD18 KO mice resulted in comparable levels of tissue infection, histopathological patterns, and bacterial localization in the spleen (within macrophages). Since mice generated with a mutation in the CD18 locus have undetectable levels of CD11b/CD18 on their neutrophils or macrophages (19), the results strongly suggest that the absence of CR3 and CR4 in vivo has no impact on the ability of M. avium to be phagocytosed by macrophages. This finding indicates that bacteria, under conditions encountered in the host environment, will enter macrophages lacking both CR3 and CR4 receptors in vitro, probably via other surface receptors, such as CR1 (5), scavenger receptors (6, 25), the vitronectin receptor (20), and the mannose receptor (5).

Previous studies determined that in the presence of serum, both M. avium and M. tuberculosis enter macrophages by a serum-dependent mechanism early in the infection (5, 22), although later on uptake seems to take place mostly by complement-independent pathways.

The observation that CD18 KO mice developed levels of infection similar to those of C57 BL/6 controls has several implications. First, it suggests that M. avium most likely grows in the same organs and within similar cells in the two strains of mice. This conclusion is supported by the histopathological findings as well as by the electron microscopy data showing the presence of bacteria within macrophages. Second, the fact that the rates of growth of M. avium infecting the two strains of mice are comparable indicates that M. avium bacteria are most likely found in similar intracellular environments, i.e., within similarly formed vacuoles. Our results showing that the intravacuolar pHs in macrophages from the wild-type C57 BL/6 mice and the CD18 KO mice are similar (data not shown) support that conclusion. Third, whatever effect the surface receptor(s) by which the bacteria are taken up by macrophages has on the fate of intracellular organisms, it is likely that M. avium was ingested by similar receptors on macrophages of the wild-type and the CD18 KO mice.

Although we do not known precisely how M. avium is taken up by macrophages in vivo, there are two possible mechanisms that may explain our finding that M. avium bacilli were able to cause similar levels of infection in both CD18 KO and C57/BL6 control mice: (i) mycobacteria in the host assumed a phenotype comparable to the intracellular phenotype, or (ii) bacteria used other receptors, such as CR1 and mannose receptors, to be internalized by macrophages. In fact, a number of in vitro studies of mycobacteria as well as other bacteria, such as Salmonella, Legionella, and Yersinia spp., had shown that the in vitro culture conditions significantly influence the uptake by both epithelial intestinal cells and macrophages (7, 15, 17). For example, the ability of Salmonella spp. to invade epithelial cells increases when the bacteria are cultured under anaerobic conditions (17). Similarly, Legionella pneumophila is internalized by either coiling phagocytosis or conventional phagocytosis, depending on the culture conditions prior to the assay (7). Likewise, expression of invasin, a protein associated with epithelial cell invasion, by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is dependent on the temperature and the growth phase (15). In addition, we have shown that M. avium grown under conditions that resemble the intestinal environment is significantly more efficient at invading intestinal epithelial cells than when grown under laboratory conditions (3). Therefore, the ability of a bacterium to adapt to different challenging environments that are encountered in vivo is responsible for the existence of different phenotypes that are unlike the ones obtained when the bacterium is cultured on a rich medium under optimum laboratory conditions. It is a characteristic of mycobacterial infection both in vitro and in vivo that bacteria exit infected macrophages to subsequently infect other macrophages in the vicinity. Tissues that contain a small focus of infection early on will show extensive infection later (10). In addition, M. avium, and perhaps M. tuberculosis, needs to translocate through the mucosal epithelial cells before invading macrophages, requiring a transition period intracellularly. It is quite plausible that this temporary phase of the infection induces a change of phenotype, resulting in a bacterium that is significantly more efficient at invading other cells than was the original one (2).

A number of in vitro studies have demonstrated the roles of several membrane receptors in the entry of both M. avium and M. tuberculosis into macrophages (5, 9, 12, 13, 18, 21–23, 25). It is still plausible that mycobacteria circulating in the blood express the extracellular growth phenotype (laboratory grown), since a large percentage of the bacteria are initially extracellular (24a). Therefore, in this scenario, M. avium would activate and bind to the C3b fraction of complement and enter cells via the complement receptors (5, 11, 21, 22).

In summary, our results are not in disagreement with previously published work regarding the role of complement in in vitro infection of macrophages by mycobacteria, but in contrast to the original proposal of the importance of CR3 and CR4 receptors for the uptake of M. avium, our data support a reevaluation of the role of complement receptors in the phagocytosis of M. avium by tissue macrophages in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Allen for preparing the manuscript and Ted Pella, Inc., for kindly providing electron microscopy supplies.

This study was supported by contract no. NO1-AI-25140 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bermudez L E, Goodman J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis invades and replicates within type II alveolar cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1400–1406. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1400-1406.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bermudez L E, Parker A, Goodman J. Growth within macrophages increases the efficiency of Mycobacterium avium in invading other macrophages by a complement receptor-independent pathway. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1916–1925. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1916-1925.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bermudez L E, Petrofsky M, Goodman J. Exposure to low oxygen tension and increased osmolarity enhance the ability of Mycobacterium avium to enter intestinal epithelial (HT-29) cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3768–3773. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3768-3773.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bermudez L E, Stevens P, Kolonoski P, Wu M, Young L S. Treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection in mice with recombinant interleukin-2 and tumor necrosis factor. J Immunol. 1989;143:2996–3002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bermudez L E, Young L S, Enkel H. Interaction of Mycobacterium avium complex with human macrophages: roles of membrane receptors and serum proteins. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1697–1702. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.5.1697-1702.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Champsi J, Young L S, Bermudez L E. Production of TNF-α, IL-6 and TGFβ and expression of receptors for TNFα and IL-6 during murine Mycobacterium avium infection. Immunology. 1995;84:549–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cirillo J D, Falkow S, Tompkins L S. Growth of Legionella pneumophila in Acanthamoeba castellanii enhances invasion. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3254–3261. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3254-3261.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crowle A J, Tsang A Y, Vatter A E, May M H. Comparison of 15 laboratory and patient-derived strains of Mycobacterium avium for ability to infect and multiply in cultured human macrophages. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:812–821. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.5.812-821.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cywes C, Godenir N L, Hoppe H C, Scholle R R, Steyn L M, Kirsch R E, Ehlers M R W. Nonopsonic binding of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to human complement receptor type 3 expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5373–5383. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5373-5383.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dannenberg A M., Jr Pathogenesis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;125:25–30. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.125.3P2.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ernst J D. Macrophage receptors for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1277–1281. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1277-1281.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaynor C D, McCormack F X, Voelker D R, McGowan S E, Schlesinger L S. Pulmonary surfactant protein A mediates enhanced phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by a direct interaction with human macrophages. J Immunol. 1995;155:5343–5351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch C S, Ellner J J, Russell D G, Rich E A. Complement receptor-mediated uptake and tumor necrosis factor α-medicated growth inhibition of M. tuberculosis by human alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 1994;152:743–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inderlied C B, Kemper C A, Bermudez L E. The Mycobacterium avium complex. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:266–310. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isberg R R. Determinants for thermoinducible cell binding and plasmid-encoded cellular penetration detected in the absence of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis invasin protein. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1998–2005. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.7.1998-2005.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S Y, Goodman J R, Petrofsky M, Bermudez L E. Mycobacterium avium infection of the gut mucosa in mice is associated with later inflammatory response and ultimately results in areas of intestinal cell necrosis. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:725–731. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-8-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee C A, Falkow S. The ability of Salmonella to enter mammalian cells is affected by bacterial growth state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4304–4308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson P K, Gekker G, Hu S, Sheng W S, Anderson W R, Ulevitch R J, Tobias P S, Gustafson K V, Molitor T W, Chao C C. C14 receptor-mediated uptake of nonopsonized Mycobacterium tuberculosis by human microglia. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1598–1602. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1598-1602.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plow E J, Zhang L. A MAC-1 attack: integrin functions directly challenged in knockout mice. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:1145–1146. doi: 10.1172/JCI119267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao S P, Ogata K, Catanzaro A. Mycobacterium avium-M. intracellulare binds to the integrin receptor αVβ3 on human monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. Infect Immun. 1993;61:663–670. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.663-670.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schlesinger L S, Bellinger-Kawahara C, Payne N R, Horwitz M A. Phagocytosis of M. tuberculosis is mediated by human monocyte complement receptors and complement component C3. J Immunol. 1990;144:2771–2780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schorey J S, Carroll M C, Brown E J. A macrophage invasion mechanism of pathogenic mycobacteria. Science. 1997;277:1091–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stokes R W, Haidl I D, Jefferies W A, Speert D P. Mycobacteria-macrophage interactions. Macrophage phenotype determines the nonopsonic binding of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to murine macrophages. J Immunol. 1993;152:743–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schlesinger P H, Chakraborty P, Haddix P L, Collins H L, Fok A K, Allen R D, Gluck S L, Heuser J, Russell D G. Lack of acidification in Mycobacterium phagosomes produced by exclusion of the vesicular proton-ATPase. Science. 1994;263:678–681. doi: 10.1126/science.8303277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24a.Wu, H., P. Kolonoski, and L. Bermudez. Unpublished data.

- 25.Zimmerli S, Edwards S, Ernst J D. Selective receptor blockade during phagocytosis does not alter the survival and growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human macrophages. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:760–770. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.6.8969271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]