Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has a great impact on society as a whole. Yet the pandemic and associated mandatory lockdown in several countries may have increased the vulnerability of certain populations. The present study aimed to document the frequency of clinical level of psychological distress and COVID-19 related post-traumatic stress symptoms in youth during the first wave of the pandemic. The study more specifically explored the role of prior trauma and adverse life events as a vulnerability factor for negative outcomes. A sample of 4914 adolescents and young adults from the province of Quebec, Canada was recruited online through social networks during the first wave of COVID-19. Results revealed that 26.6% of youth displayed serious psychological distress and 20.3% probable PTSD symptoms. The number of past traumas and adversity experienced showed a dose-response relation with the prevalence of psychological distress and PTSD. After controlling for socio-demographic characteristics and COVID-19 related variables (exposure, fear, suspicion of having the infection), participants with a history of five traumas and more presented a two-fold risk of serious psychological distress and probable PTSD. Emotion dysregulation was also associated with an increased risk of symptoms while resilience was linked to a reduced risk of distress.

Keywords: COVID-19, Adverse life events, Trauma, PTSD, Psychological distress, Youth

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, due to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began in December 2019 and represents a world-health crisis. To date, the number of cases has exceeded 555 million and the virus has caused more than six million deaths (WHO, 2022). The pandemic has many psychosocial consequences on the world population (Wu et al., 2021). Several health measures have been put in place to curb the spread of the pandemic, but these measures may inadvertently lead to other significant public health issues. Indeed, several studies point out that confinement measures may be associated with an increase in violence (Augusti et al., 2021; Fabbri et al., 2021) due to the lack of a safety net. In a review of the studies related to the pandemic and past findings on infectious disease outbreaks, the fear of contracting the virus and the consequences of the lockdown (loss of employment, social isolation, restricted access to health or social services) were found to be related to significant symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the population (Boyraz and Legros, 2020). The pandemic may also particularly affect adolescents and young adults, who are in a pivotal developmental period in which social networking and personal development are essential. The available studies report a risk of developing a mental health problem in youth following the COVID-19 outbreak (Samji et al., 2021). Some personal factors may also promote or hinder positive adaptation of individuals. For example, emotional dysregulation, or the difficulty of an individual to manage his emotions adequately (Gross, 2008), is associated with various mental health issues (Berking and Wupperman, 2012). Resilience, the ability to adapt in the face of adversity (Luthar et al., 2000), is associated with fewer symptoms of PTSD in several studies (Horn and Feder, 2018).

Furthermore, there may be an increased risk of psychological distress in populations that already have pre-existing vulnerabilities. Indeed, the stress due to the pandemic could trigger a resurgence of symptoms in individuals who have experienced interpersonal trauma and life adversities (Morabito et al., 2021). A number of empirical reports have documented a graded dose response relationship between adverse childhood experiences and health-risk behaviors, as well as poor psychological and physical health (Luby et al., 2017; Ramiro et al., 2010). Trauma, and even more so cumulative trauma, exacerbates the risk not only for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Briere et al., 2016) but may also impede on the development of efficient coping strategies to face later adversities (Sheffler et al., 2019). The stress sensitization model posits that early experiences of adversities may heighten the vulnerability to distress following subsequent exposure to others stressful life events (Hammen et al., 2000). Youth with a history of past traumas may thus, when faced with new unforeseen stressors including the current pandemic context, may be particularly vulnerable to psychological distress.

The purpose of this study was first to determine the frequency of serious psychological distress and COVID-19-related PTSD symptoms in a sample of adolescents and young adults. Our second aim was to identify factors associated to psychological distress and PTSD symptoms in a sample of adolescents and young adults. The potential factors examined include sociodemographics, COVID exposure, history of trauma and adverse life events, emotional regulation and resilience.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and procedure

Participants were recruited online through announcements on social networks to answer an online survey on the Qualtrics platform which allows the anonymity of the data. The recruitment took place between April 21 and May 26, during the first wave of COVID-19 in Quebec. At that time, a lockdown was established, schools and all non-essential services were closed (restaurants, shops, theater, etc.). To be included, participants had to be between 14 and 25 years of age, live in the province of Quebec, and speak French. As a financial compensation, the participants could enter a contest to win one of ten 50$ gift cards at the end of the survey. Of the 7123 registered answers, 32 participants were withdrawn due to invalid responses (similar responses throughout the survey, duplicates, response time too short). For the present analyses, 2177 had provided incomplete data on the measures considered; thus, the final sample consisted of 4914 participants. This investigation was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study design was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Université du Québec à Montréal. Informed consent of the participants was obtained after the nature of the procedures had been fully detailed.

2.2. Measures

Participants were invited to provide sociodemographic information (gender, sexual orientation, age, occupation, ethnicity) and complete the following measures:

2.2.1. History of past trauma and adversity

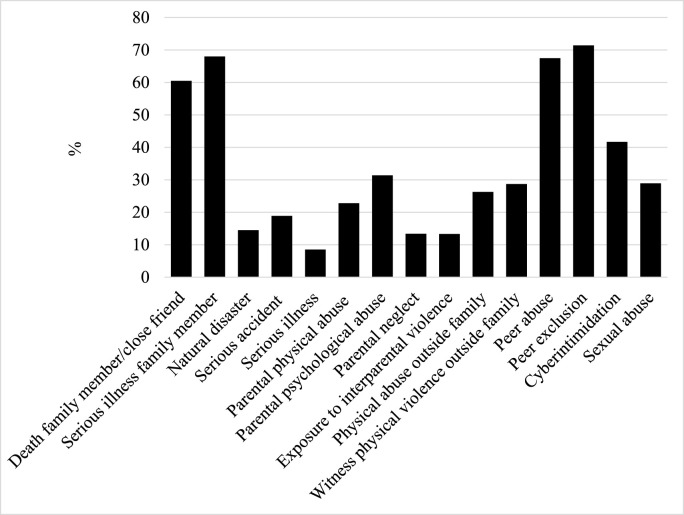

Items derived from Hamby et al. (2015), Hamby et al. (2018) and Finkelhor et al. (1990) were used to measure the number of past traumas and adversities experienced by participants. The scale contains 15 items (see Fig. 1 ) Participants answered Yes or No if they experienced the trauma or adversity listed. The score ranges from 0 to 15 (M = 5.68; SD = 3.06) and a cut-off was created to categorize those who experienced fewer traumas than average (0–4 traumas) and more or equal number of traumas than average (5 traumas or more). All the items are listed in the supplementary materials.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of participants reporting experiences of trauma and adverse life events.

2.2.2. Primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5

The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (Prins et al., 2016) was used to measure PTSD symptoms linked to COVID-19. For the present study, participants were asked to answer items in reference to the exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic. The scale consists of 5 items completed with a Yes or No format and total score ranging from 0 to 5. A cut-off of 3 was found to be optimally sensitive to probable PTSD (Prins et al., 2016). The scale showed good internal consistency (α = 0.82) in the present study.

2.2.3. Kessler psychological distress scale

Psychological distress was measured by the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6; Kessler et al., 2002) that consists in 6 items and a total score varying between 0 and 24. Participants were asked to respond based on symptoms in the last week. The response options vary from Rarely (1) to Always (4). As per previous studies (Kessler et al., 2002; McGinty et al., 2020), we used the cut-off score (scores ranging from 13 to 24) to identify serious psychological distress. The scale showed acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.70).

2.2.4. COVID-related items

To assess whether or not participants had had the COVID-19, three indicators were created: 1) Had COVID (No, 0; Yes, 1), 2) Suspect having COVID and/or waiting test results (No, 0; Yes, 1) and 3) Fear of being infected on a 4-point scale (Not true, 1; A little bit true, 2; Mostly true, 3; Very true, 4). This last indicator was recoded to assess if the fear was absent (Not true) or present (A little bit true to Very true).

2.2.5. Emotion dysregulation

The 4-item Emotional Regulation Scale (Hamby et al., 2015) was used to measure the emotion dysregulation of the participants (for e.g., “When I'm upset, it takes me a long time to feel better”). Participants answered item with a 4-point Likert scale (Not true, 1; A little bit true, 2; Mostly true, 3; Very true, 4). The scale showed high internal consistency (α = 0.88). The total score was calculated by computing the mean of the items. A dichotomous score was then created to assess the presence or absence of emotion dysregulation. A score was considered clinical if it reached ≥0.5 standard deviation of the mean. In this sample, the mean score was 2.24. (SD = 0.76).

2.2.6. Resilience

To assess resilience, the Connor-Davidson Resilience scale 2 (CD-RISC2, Connor and Davidson, 2003; Vaishnavi et al., 2007) was used. The two items reflecting the ability to bounce back and successfully adapt to change were answered with a 4-point Likert scale (Not true, 1; A little bit true, 2; Mostly true, 3; Very true, 4). The average score of 1–4 was recoded to assess if there was an absence or a presence of resilience. A participant was considered resilient when his actual score reached ≥0.5 standard deviation of the mean (M = 2.80; SD = 0.76).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive data

The sample consisted of participants identifying themselves as cisgender girls (64.2%), cisgender boys (33.5%), and participants identifying as gender minorities (trans, gender queer) (2.3%). A total of 77.9% of youth reported heterosexual orientation. The vast majority of participants were born in Quebec or Canada (91.7%). The average age of participants is 19.93 (SD = 3.14) and 72.2% were students, 21.9% were working, and 5.9% reported not currently enrolled in school or working.

The vast majority of participants (94.2%) reported not having the virus, 5.2% suspected having it while 0.6% had the COVID-19. The percentage of participants who had experienced each trauma and adverse event assessed is illustrated in Fig. 1.

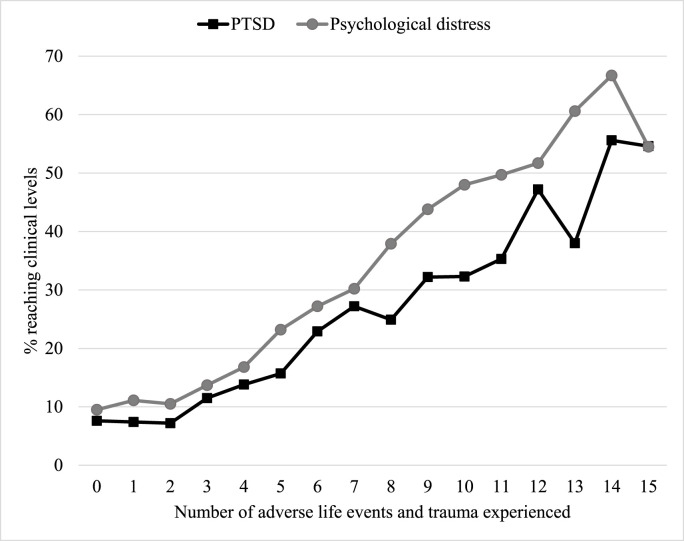

Overall, 26.6% of participants obtained score above the clinical cut-off score for serious psychological distress. In addition, 20.3% of youth showed scores indicative of probable PTSD symptoms. In Fig. 2 , the prevalence of participants reaching clinical levels of psychological distress and PTSD symptoms is illustrated as function of the number of adverse life events and trauma experienced. The results of the Chi-square analysis showed a significant association between the number of adverse events and trauma experienced and the presence of clinical levels of psychological distress (χ2 (1) = 448.93; p < .001) and the presence of PTSD linked to the pandemic (χ2 (1) = 302.37; p < .001).

Fig. 2.

Percentage of participants reaching clinical levels of psychological distress and PTSD by number of adverse life events and trauma experienced.

3.2. Bivariate analyses

A series of chi-square analysis was first conducted to ascertain the associations between the different variables of interest and prevalence of clinical levels of serious psychological distress and probable PTSD symptoms. Findings revealed significant associations (see Table 1 ). The prevalence of serious psychological distress and probable PTSD was higher among cisgender girls compared to cisgender boys, and among participants identifying themselves as part of sexual or gender minorities. Participants born outside Canada were also found more likely to display negative outcomes linked to the pandemic.

Table 1.

Bivariate analyses of % of clinical level of psychological distress and COVID related PTSD.

| Variable | Presence of clinical level of psychological distress (%) | Presence of clinical level of PTSD (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | χ2 (1) = 75.06 ∗∗∗ | χ2 (1) = 78.99 ∗∗∗ |

| Boys | 18.4 | 12.7 |

| Girls | 29.9 | 23.4 |

| Identifying as gender or sexual minority | χ2 (1) = 135.99 ∗∗∗ | χ2 (1) = 40.95 ∗∗∗ |

| No | 22.6 | 18.3 |

| Yes | 40.2 | 27.1 |

| Country of origin | χ2 (1) = 10.60 ∗∗ | χ2 (1) = 4.08 ∗ |

| From Canada | 25.9 | 19.9 |

| From outside Canada | 33.3 | 24.0 |

| Suspicion of having COVID | χ2 (1) = 3.91 ∗ | χ2 (1) = 16.86 ∗∗∗ |

| No | 26.3 | 19.7 |

| Yes | 31.9 | 30.3 |

| Having COVID | χ2 (1) = 3.29 | χ2 (1) = 5.66 ∗ |

| No | 26.5 | 20.1 |

| Yes | 41.4 | 37.9 |

| Fear of COVID | χ2 (1) = 18.46 ∗∗∗ | χ2 (1) = 110.03 ∗∗∗ |

| No | 21.3 | 8.6 |

| Yes | 27.9 | 23.3 |

| Number of traumas and adversities | χ2 (1) = 268.00 ∗∗∗ | χ2 (1) = 175.18 ∗∗∗ |

| Less than five | 13.5 | 10.6 |

| Five and more | 34.7 | 26.2 |

| Emotion dysregulation | χ2 (1) = 910.12 ∗∗∗ | χ2 (1) = 239.21 ∗∗∗ |

| No | 13.8 | 14.3 |

| Yes | 54.6 | 33.3 |

| Resilience | χ2 (1) = 226.47 ∗∗∗ | χ2 (1) = 94.77 ∗∗∗ |

| No | 32.6 | 23.8 |

| Yes | 11.7 | 11.5 |

Note. ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .001.

Suspicion of having COVID and fear of the infection were also linked to greater frequency of both psychological distress and probable PTSD. In addition, youth that had COVID reported higher likelihood of PTSD symptoms. As expected, the prevalence of reaching levels of serious psychological distress and PTSD symptoms was higher in participants reporting a history of five traumas and adversities or more, who scored high in emotion dysregulation and low on resilience.

3.3. Regression analyses

A logistic regression analysis was performed first with the presence of clinical level of serious psychological distress as a dependent variable and second with the presence of probable PTSD symptoms as a dependent variable. Socio-demographic variables including age, sex, identification as gender or sexual minority, and ethnicity were controlled for. COVID-related variables (suspicion of COVID, having COVID, fear of COVID), history of traumas and adverse life events (experiencing five traumas/adverse life events or more), emotion dysregulation and resilience served as independent variables in both analyses. Each analysis was conducted using the direct-entry method to allow to ascertain the unique contribution of each variable beyond that of the others. Results are presented in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Logistic regression analyses associated to clinical levels of psychological distress and COVID-related PTSD.

| Psychological distress: χ2(10) = 1129.63, p < .001; Cox & Snell R2 = .21 Nagelkerke R2 = .31 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Β | SE | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI |

| Age | −.00 | .01 | .08 | .77 | .10 | .97–1.02 |

| Identifying as cisgender girl | .31 | .09 | 13.19 | .00 | 1.37 | 1.16–1.62 |

| Identifying as gender or sexual minority | .47 | .09 | 29.56 | .00 | 1.60 | 1.35–1.90 |

| Ethnicity | −.34 | .13 | 6.72 | .01 | .71 | .55–.92 |

| Suspicion of COVID | .09 | .17 | .27 | .60 | 1.09 | .79–1.51 |

| Has COVID | .27 | .49 | .29 | .59 | 1.30 | .50–3.40 |

| Fear of COVID | −.00 | .10 | .00 | .99 | .10 | .82–1.21 |

| Experienced 5 traumas and more | .96 | .09 | 124.50 | .00 | 2.61 | 2.21–3.09 |

| Emotion dysregulation | 1.70 | .08 | 496.95 | .00 | 5.47 | 4.71–6.35 |

| Resilience | −.95 | .10 | 90.58 | .00 | .39 | .32–.47 |

| PTSD: χ2(10) = 512.65, p < .001; Cox & Snell R2 = .10 Nagelkerke R2 = .16 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Β | SE | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI |

| Age | .02 | .01 | 3.05 | .08 | 1.02 | .10–1.05 |

| Identifying as cisgender girl | .46 | .09 | 25.90 | .00 | 1.59 | 1.33–1.90 |

| Identifying as gender or sexual minority | .15 | .09 | 2.94 | .09 | 1.17 | .98–1.39 |

| Ethnicity | −.26 | .13 | 3.77 | .05 | .77 | .60–1.00 |

| Suspicion of COVID | .58 | .16 | 13.81 | .00 | 1.78 | 1.31–2.41 |

| Has COVID | .90 | .43 | 4.26 | .04 | 2.45 | 1.05–5.73 |

| Fear of COVID | .95 | .13 | 57.74 | .00 | 2.59 | 2.03–3.32 |

| Experienced 5 traumas and more | .84 | .09 | 86.16 | .00 | 2.31 | 1.93–2.75 |

| Emotion dysregulation | .75 | .08 | 88.38 | .00 | 2.12 | 1.81–2.48 |

| Resilience | −.60 | .10 | 36.17 | .00 | .55 | .45–.67 |

Note. OR = Odds ratio.

The regression analysis to assess which variables were associated with clinical levels of psychological distress was significant (χ2 = 1129.63, p < .001). Compared to cisgender boys, cisgender girls were more likely to show clinical levels of distress (OR: 1.37). Identifying as a member of a gender or sexual minority is linked to an increased odd of presenting clinical levels of distress (OR: 1.60). In addition, ethnicity was associated with PTSD as being born in Canada decreased the odds of serious psychological distress (OR: 0.71) relative to being born outside Canada. Reporting a history of more than 5 traumas or adversities was associated with more than a two-fold risk (OR: 2.61) of serious psychological distress. As expected, high emotional dysregulation was linked to greater odds (OR: 5.47) of distress while displaying high resilience (OR: 0.39) significantly decreased the odds.

Analysis performed with scores of probable PTSD symptoms also produced significant results (χ2 = 512.65, p < .001). Cisgender girls (OR: 1.59) were more likely to show scores indicative of probable PTSD symptoms related to COVID-19 relative to cisgender boys. Suspicion of infection (OR: 1.78), being afraid of COVID (OR: 2.59) or having COVID (OR: 2.45), were all associated with a heightened risk of presenting probable PTSD. Participants who had experienced five traumas/adverse life events or more were more than twice (OR: 2.31) as likely to exhibit probable COVID-related PTSD. Similarly to results found for psychological distress, participants with high emotion dysregulation (OR: 2.12) were vulnerable to PTSD symptoms while for participants with high resilience, the likelihood of probable PTSD symptoms decreased (OR: 0.55).

4. Discussion

The present study first aimed to document the frequency of clinical psychological distress and COVID-19-related PTSD symptoms and document the association with a history of trauma and adversity. The COVID-19 pandemic affects the population in several ways and to varying degrees (Wu et al., 2021). Government authorities have implemented several measures to slow the spread of the virus. In the province of Quebec of Canada, in the spring of 2020, a mandatory lockdown was implemented, non-essential services have been closed as well as schools. During such lockdowns, some populations may be particularly vulnerable, not only because of the virus itself, but also because of restricted access to services and social isolation (Brooks et al., 2020; Simon et al., 2021). Teenagers and young adults, being at a crucial developmental stage in which they are envisioning their future, and in which interpersonal relationships are essential, may be among the populations for which such preventative measures may affect. Moreover, youth with a history of past trauma and adversity may be at higher risk of developing anxiety and depression disorders as well as addictions and other mental health problems (Dvir et al., 2014).

Our results revealed that one quarter of teenagers and young adults show serious psychological distress while one-fifth display significant PTSD symptoms related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings also underscore a dose-response relation between increasing numbers of past traumas and adversities experienced and psychological distress and COVID-related PTSD.

Our analysis also aimed to explore the possible factors that may be associated the occurrence of clinical levels of psychological distress and PTSD symptoms in a sample of adolescents and young adults. Cisgender girls were found more likely to show clinical levels of distress and PTSD relative to cisgender boys. These results are consistent with findings from recent studies showing that women experience more psychological symptoms following the COVID outbreak (Ausín et al., 2021), and more broadly, with studies on trauma which suggest that women present with rates of PTSD symptoms twice as high as men (Tolin and Foa, 2006). Our findings revealed that yough identifying themselves as belonging to gender or sexual minorities are also more vulnerable to serious psychological distress. Silliman Cohen and Bosk (2020) report that the pandemic may be a particularly difficult situation for gender and sexual minorities not only because of the resulting limited access to a social safety net, but also given that the confinement may sometimes force them to remain in a non-supportive, even violent environment. Results also showed that participants born outside of Canada were more vulnerable to PTSD symptoms. Immigrants face specific challenges which could be accentuated during the pandemic (Dalexis and Cénat, 2020).

Results also showed that suspicion of having COVID and fear of infection was associated with higher odds of probable PTSD symptoms. Tang et al. (2020) found similar results among a sample of university students in China in that feeling extremely scared during the outbreak was a predictor of PTSD symptoms. This may relate to the long incubation period of the virus that creates a stress of unknowingly having COVID-19 and unintentionally spreading it (Tang et al., 2020).

After controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and COVID-related variables, our results revealed that having experienced five traumas or adverse life events or more is associated with more than a two-fold increased likelihood of clinical levels of psychological distress and COVID-related PTSD symptoms. These findings are consistent with recent studies suggesting that the pandemic is likely to increase the risk of distress in populations with pre-existing vulnerabilities (Blix et al., 2021; Boyraz and Legros, 2020; Silliman Cohen and Bosk, 2020). Individuals with a history of past trauma and adversities may experience a resurgence of symptoms as a result of the pandemic. Individuals with a history of trauma, especially those who have experienced severe, chronic abuse involving caregivers may present with Complex PTSD and may be more likely to respond with heightened fear when confronted with later stressful events (Morabito et al., 2021; Tsur and Abu-Raiya, 2020).

Our study also considered two key variables that may impact on outcomes. First, as expected, emotional dysregulation contributed to increased odds of presenting with clinical levels of psychological distress and COVID-related PTSD symptoms. According to previous studies, negative coping strategies, which include emotional dysregulation, were found to be linked to poorer reactions to stress (Jungmann and Witthöft, 2020). Second, resilience and the capacity to bounce back from adversity may act as a buffer against PTSD symptoms and psychological distress. Studies on pandemic suggest that a higher level of resilience could be associated with fewer COVID-related worries (Paredes et al., 2021). While the pandemic appears to be associated with a negative impact on a large number of youth, it appears to some may adapt well and continue to function normally (Chen and Bonanno, 2020; Panchal et al., 2021). It is also important to highlight this possibility and eventually understand why (Dvorsky et al., 2020). Such an analysis may identify important targets for intervention. Training and teaching in the use of positive coping strategies such as emotional regulation should be promoted in school and family settings, for children, but also for adolescents who are in an important period of change and identity formation.

4.1. Limitations

The study presents a number of limitations. First, no baseline assessment was measured, and the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow for causal inferences to be drawn. Second, because the study relied on a convenience sample, the generalization of the findings is limited. Considering that the spread as well as the sanitary measures put in place varied greatly from one province to another or from one country to another, it is difficult to generalize the experience of the first lockdown in Quebec to those issued elsewhere. Furthermore, our results may not be representative of the larger population of youth in Quebec. In addition, the study did not allow to explore the maintenance of the symptoms over time. Thus, the prevalence of symptoms reflects the reality of youth during the first lockdown in the spring of 2020 and may not represent the situation of youth confronted to the subsequent waves of the pandemic. In addition, the measure used in this study to assess PTSD symptoms is designed to screen individuals with probable PTSD, and assessment with a structured interview or with more comprehensive self-report measure should be considered in future studies. Moreover, the rates of probable PTSD might have been heightened as the life-threat trauma criterion was not directly assessed. Also, while the results of the logistic regressions are statistically significant, the percentage of variance explained remains modest, suggesting other variables may come into play (e.g., presence or absence of social support). Finally, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow us to determine whether symptoms were present prior to the onset of the pandemic since the data were collected when the pandemic had already been declared. Although participants were instructed to answer PTSD items in relation to the pandemic, it is conceivable that some participants' increased sensitivity to stress was a resurgence of symptoms due to their trauma history instead of COVID-19 stress. Despite these limitations, our findings provide evidence of the immediate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated confinement measures in youth and the heightened vulnerability of youth with a history of past traumas and adverse life events.

4.2. Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to explore a history of past traumas as a risk factor of COVID-19-related probable PTSD symptoms and psychological distress among youth in Quebec during the first wave of the pandemic. Our findings clearly suggest that special attention must be given to youth's mental health during the pandemic as one out of four youth displayed clinical psychological distress and one out of five had probable PTSD symptoms. These high percentages are quite concerning and raise questions about the support services that need to be put in place to address these issues. Authors have proposed a host of solutions including working on the different features of fear experienced during the pandemic by increasing emotional regulation and attachment security, embracing acceptance and valuing responsibility (Schimmenti et al., 2020). Our findings underscore that there is also an important need to offer services to youth with a history of trauma and adversity. The interaction between past trauma and the uncertainty surrounding the current pandemic may indeed create a complex stressor which is important to untangle for vulnerable populations. Trauma-informed care practices (trustworthiness and transparency, safety, peer support, collaboration and mutuality, empowerment and choice, cultural, historical and gender issues) can guide intervention practices at the time of COVID-19 (Collin-Vézina et al., 2020). Apart from personal competencies (for instance, hardiness, coping skills), interpersonal strengths as well as family, peer, and community support may offer resources that facilitate navigating through difficult times.

Author statement

MH: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Data curation; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing, AJT: Formal analysis; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing, LF: Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

Role of funding

This research was supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program (Grant #950-230791).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the youth who participated in the study and Manon Robichaud for data management.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psycom.2022.100092.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Augusti E.-M., Sætren S.S., Hafstad G.S. Violence and abuse experiences and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in a population-based sample of Norwegian adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;118 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausín B., González-Sanguino C., Castellanos M.Á., Muñoz M. Gender-related differences in the psychological impact of confinement as a consequence of COVID-19 in Spain. J. Gend. Stud. 2021;30(1):29–38. doi: 10.1080/09589236.2020.1799768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berking M., Wupperman P. Emotion regulation and mental health: recent findings, current challenges, and future directions. Curr. Opin. Psychiatr. 2012;25(2):128–134. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blix I., Birkeland M.S., Thoresen S. Worry and mental health in the Covid-19 pandemic: vulnerability factors in the general Norwegian population. BMC Publ. Health. 2021;21(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10927-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyraz G., Legros D.N. Coronavirus disease (covid-19) and traumatic stress: probable risk factors and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Loss Trauma. 2020;25:503–522. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2020.1763556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J., Agee E., Dietrich A. Cumulative trauma and current posttraumatic stress disorder status in general population and inmate samples. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2016;8(4):439–446. doi: 10.1037/tra0000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Bonanno G.A. Psychological adjustment during the global outbreak of COVID-19: a resilience perspective. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S51–S54. doi: 10.1037/tra0000685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin-Vézina D., Brend D., Beeman I. Developmental Child Welfare; 2020. When it Counts the Most: Trauma-Informed Care and the COVID-19 Global Pandemic. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connor K.M., Davidson J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) Depress. Anxiety. 2003;18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalexis R.D., Cénat J.M. Asylum seekers working in Quebec (Canada) during the COVID-19 pandemic: risk of deportation, and threats to physical and mental health. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;292 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113299. 113299-113299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvir Y., Ford J.D., Hill M., Frazier J.A. Childhood maltreatment, emotional dysregulation, and psychiatric comorbidities. Harv. Rev. Psychiatr. 2014;22(3):149–161. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorsky M.R., Breaux R., Becker S.P. Finding ordinary magic in extraordinary times: child and adolescent resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01583-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri C., Bhatia A., Petzold M., Jugder M., Guedes A., Cappa C., Devries K. Modelling the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on violent discipline against children. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;116 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D., Hotaling G., Lewis I.A., Smith C. Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse Negl. 1990;14:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J.J. Emotion regulation. Handbook of emotions. 2008;3(3):497–513. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S., Grych J., Banyard V. Life Paths measurement packet: finalized scales. Sewanee, TN: Life Paths Research Program. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S., Taylor E., Smith A., Blount Z. Life Paths Research Center; 2018. Resilience Portfolio Questionnaire Manual: Scales for Youth. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C., Henry R., Daley S.E. Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000;68:782–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn S.R., Feder A. Understanding resilience and preventing and treating PTSD. Harv. Rev. Psychiatr. 2018;26(3):158–174. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann S.M., Witthӧft Michael. Health anxiety, cyberchondria, and coping in the current COVID-19 pandemic: which factors are related to coronavirus anxiety? J. Anxiety Disord. 2020;73:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Andrews G., Colpe L.J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D.K., Normand S.L., Walters E., Zaslavsky A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby J.L., Barch D., Whalen D., Tillman R., Belden A. Association between early life adversity and risk for poor emotional and physical health in adolescence: a putative mechanistic neurodevelopmental pathway. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(12):1168–1175. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S.S., Cicchetti D., et Becker B. The construct of resilience : a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):543-562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty E.E., Presskreischer R., Anderson K.E., Han H., Barry C.L. Psychological distress and COVID-19–related stressors reported in a longitudinal cohort of US adults in April and July 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(24):2555–2557. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabito D.M., Bedford C.E., Woller S., Schmidt N.B. Vulnerability to COVID-19–related disability: the impact of posttraumatic stress symptoms on psychosocial impairment during the pandemic. J. Trauma Stress. 2021;34(4):701–710. doi: 10.1002/jts.22717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchal U., Salazar de Pablo G., Franco M., Moreno C., Parellada M., Arango C., Fusar-Poli P. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. 2021:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01856-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes M.R., Apaolaza V., Fernandez-Robin C., Hartmann P., Yañez-Martinez D. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on subjective mental well-being: the interplay of perceived threat, future anxiety and resilience. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2021;170 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins A., Bovin M.J., Smolenski D.J., Marx B.P., Kimerling R., Jenkins-Guarnieri M.A., Kaloupek D.G., Schnurr P.P., Kaiser A.P., Leyva Y.E., Tiet Q.Q. The primary care ptsd screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2016;31:1206–1211. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro L.S., Madrid B.J., Brown D.W. Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and health-risk behaviors among adults in a developing country setting. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(11):842–855. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samji H., Wu J., Ladak A., Vossen C., Stewart E., Dove N., Long D., Snell G. Review: mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth – a systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health. 2021 doi: 10.1111/camh.12501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti A., Billieux J., Starcevic V. The four horsemen of fear: an integrated model of understanding fear experiences during the covid-19 pandemic. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2020;17:41–45. doi: 10.36131/CN20200202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffler J.L., Piazza J.R., Quinn J.M., Sachs-Ericsson N.J., Stanley I.H. Adverse childhood experiences and coping strategies: identifying pathways to resiliency in adulthood. Hist. Philos. Logic: Int. J. 2019;32(5):594–609. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2019.1638699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman Cohen R., Bosk E.A. Vulnerable youth and the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J., Helter T.M., White R.G., van der Boor C., Łaszewska A. Impacts of the Covid-19 lockdown and relevant vulnerabilities on capability well-being, mental health and social support: an Austrian survey study. BMC Publ. Health. 2021;21(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10351-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W., Hu T., Hu B., Jin C., Wang G., Xie C., Chen S., Xu J. Prevalence and correlates of PTSD and depressive symptoms one month after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in a sample of home-quarantined Chinese university students. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;274:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin D.F., Foa E.B. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 2006;132:959–992. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsur N., Abu-Raiya H. Child Abuse Negl; 2020. COVID-19-related Fear and Stress Among Individuals Who Experienced Child Abuse: the Mediating Effect of Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishnavi S., Connor K., Davidson J.R. An abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), the CD-RISC2: psychometric properties and applications in psychopharmacological trials. Psychiatr. Res. 2007;152:293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worldwide Health Organization . 2022. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard.https://covid19.who.int (accessed June 2022) [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Jia X., Shi H., Niu J., Yin X., Xie J., Wang X. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;281:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.