Abstract

The Covid-19 variants' transmissibility was further quantitatively analyzed in silico to study the binding strength with ACE-2 and find the binding inhibitors. The molecular interaction energy values of their optimized complex structures (MIFS) demonstrated that Omicron BA.4 and 5's MIFS value (344.6 kcal mol−1) was equivalent to wild-type MIFS (346.1 kcal mol−1), that of Omicron BQ.1 and BQ. 1.1's MIFS value (309.9 and 364.6 kcal mol−1). Furthermore, the MIFS value of Omicron BA.2.75 (515.1 kcal mol−1) was about Delta-plus (511.3 kcal mol−1). The binding strength of Omicron BA.4, BA. 5, and BQ.1.1 may be neglectable, but that of Omicron BA.2.75 was urging. Furthermore, the 79 medicine candidates were analyzed as the binding inhibitors from binding strength with ACE-2. Only carboxy compounds were repulsed from the ACE-2 binding site indicating that further modification of medical treatment candidates may produce an effective binding inhibitor.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants (BA.4, BA.5, BA.2.75, BQ.1, BQ.1.1), ACE-2, Binding strength, Quantitative in silico analysis, Molecular interaction energy, Binding inhibitor

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Once the death numbers soared by Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 in the last winter; then, new mutants, Omicron BA.4 and BA.5, appeared, and the death numbers declined to be compatible with the influenza death numbers. Several countries announced that the disease was not to be pandemic. The definition of the pandemic is not clear, but the disease was defined as not a pandemic but a syndemic [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. But we are still fighting to control Covid-19 infection. The mutants Omicron BA.2, BA.4, and BA.5 are listed as variants of concern, and omicron BA.2.75 and BQ.1 is considered a variant of interest [5]. The SARS-Cov-2 infection mechanism was described in detail, and the target approach was proposed [6]; however, the solution is far from conclusive. The mutation of viruses is too fast, and the development of new vaccines and medicines is far behind. Previous infection with an older variant such as Alpha, Beta, or Delta offers some protection against reinfection with Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 [7]. This may be a similar mutation of the Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 S-RBD binding site to that of the older variants and different from that of Omicron BA.1 and BA.2, in which various amino acids are mutated.

Furthermore, Omicron BA4 and BA.5 showed reduced neutralization by the serum from individuals vaccinated with triple doses of AstraZeneca or Pfizer vaccine compared with Omicron BA.1 and BA.2. In addition, using the serum from Omicron BA.1 vaccine breakthrough infections, there were significant reductions in the neutralization of Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 whose multiplication extend beyond that to other variants [8], raising the possibility of repeat Omicron infections. A greater escape from neutralization of Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 compared with Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 was reported [8]. Serum from triple-vaccinated donors had a 2 to 3-fold reduction in neutralization titers compared with the neutralization of Omicron BA.1 and BA.2. The prevention of transmission might become less effective as viruses evolve antigenically further from ancestral strains. While vaccination was unlikely to eliminate transmission, the combination of vaccines with boosting by natural infection will probably continue to protect the majority from severe disease. The L452R and F486V mutations both made major contributions to Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 escape [9]. However, the L452R mutation strengthens the binding with ACE-2 based on previous analysis. One emerging sublineage Omicron BA.2.75, which might escape from antibodies due to the mutation, did not show greater antibody evasion than Omicron BA.5 [10]. A different approach to drug discovery was proposed and created minimal virions of wild-type (WT) and mutant SARS-CoV-2 with precise molecular composition and programmable complexity by the bottom-up assembly to study the free fatty acid binding pocket that was an allosteric regulatory site enabling adaptation of SARS-CoV-2 immunogenicity to inflammation states via binding of pro-inflammatory free fatty acids. Vitamin K and dexamethasone might work in the pocket instead of fatty acids; therefore, the approach may find a future COVID-19 therapy [11]. Drug resistance to Nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid) of SARS-Cov-2 protease mutants was extensively studied. The mutation around the binding site reduced enzyme activity [12]. The mutation prevented antibody binding and neutralization. The antibodies almost always interacted with the amino acid at position K417 N or E484A [13]. The original amino acid K417 is the key mutation amino acid; the mutation to neutral amino acid reduces the S-RBD binding strength with ACE-2. The S-RBD E484 is repulsed from ACE-2; therefore, the E484A mutation erases the repulsion from ACE-2. R493 and R498 of S-RBD demonstrated their binding with ACE-2 via ion-ion interaction [14]. This fact supported the previous observation [15].

On the other hand, monoclonal antibodies have been considered to prevent the virus from infecting human cells by binding to the virus's spike protein; however, Omicron is totally or partially resistant to all currently available monoclonal antibodies [16]. Another report using lentivirus-based pseudo virus demonstrated that Bamlanivimab, Casirivimab, Etesevimab, Imdevimab, and Tixagevimab were less functional against BA.2 but Bebtelovimav, Cilgavimab, Imdevimab, Sotrovimab demonstrated a little effectiveness for neutralizing Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 variants [17]. Bebtelovimab showed remarkable preserved in vitro activity against all SARS-CoV-2 variants, including Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 [18]. The monoclonal antibody may bind to the S-RBD for protection; however, the binding with ACE-2 has not been described in detail.

Previously, the MI of their optimized complex structures demonstrated that Omicron BA.2's MIFS value was 1.4 times Delta MIFS and 2.7 times Alfa MIFS. The Omicron BA.2 S-RBD demonstrated the most vital transmissible strength [15]. The 14 currently proposed medical treatment compounds did not show as the inhibitors to block the Omicron S-RBD and ACE-2 binding. Despite the availability of vaccines and medicines, the infection has not been under control, and Omicron infections are high as ever. Therefore, further study was carried out transmissibility of Omicron BA.4 and BA.5, BA.2.75, BQ.1, and BQ.1.1 as the difference in molecular interaction energy values. Additional 79 binding inhibitor candidates were analyzed in silico by calculating binding strength with ACE-2.

2. Experimental

The manual docking process was the same as that used previously [15]. The basic complex structure of SARS-CoV-2 and ACE-2 was from Ref. [19]. The amino acids of the extracted S-RBD were mutated based on the reference [5], and the mutated structures were optimized using the MM2 program. The mutated S-RBD was superimposed on the original reference structure; then, the new S-RBD and ACE-2 formed a complex in the optimization process. The MI energy values were obtained from their original and the complex's values using the following equation: MIFS = {fs (S-RBD) + fs (ACE-2)} - FS (S-RBD and ACE-2 complex), where fs is the final structure energy value of individual molecule, and FS is the final structure energy value of the complex. HB, ES, and VW indicate the final (optimized) structure, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interaction, and van der Waals force.

Computational chemical calculations were performed using a DCPIx86-based PC with an Intel Core™i7-2600 cpu 3.40 GHz (Dospara, Yokohama) with the CAChe program (Fujitsu, Tokyo). The minimum energy level was 10−7 kcal mol−1.

3. Results and discussion

The strongest molecular interaction force is ion-ion interaction; mutations of acidic and/or neutral amino acids to basic amino acids of Covid-19 S-RBD enhanced the binding strength with ACE-2 binding [20], and such mutation hiked the transmissibility of Covid-19 mutants. The typical mutations are E484K, L452R, T478K, Q493R, and Q498R. Once the Delta valiant panicked us with the stronger transmissibility. Delta's only two mutations of the S-RBD (L452R and T478K) enhanced the MIFS value 1.71 times that of WT S-RBD. Increased numbers of basic amino acids (arginine, lysin) tighten the binding via ion-ion interaction. MIES energy contributes 72% of the binding force of Delta. Furthermore, Omicron BA.1 valiant with 15 mutants (G339D, S371L, S373P, S375F, K417 N, N440K, G446S, S477 N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, G496S, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H) exhibits the stronger binding force with ACE-2. In addition, Omicron BA.2 valiant with 16 mutants (G339D, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405 N, R408S, K417 N, N440K, S477 N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H) demonstrates the strongest binding force. The four mutants to basic amino acids (N440K, T478K, Q493R, Q498R) contributed to their high MIFS energy values of Omicron BA.1 and BA.2, 761.7 and 904.3 kcal mol−1, respectively. The ion-ion interaction is their main mechanism, and their MIES values contributed 63.7% of their interaction energy value.

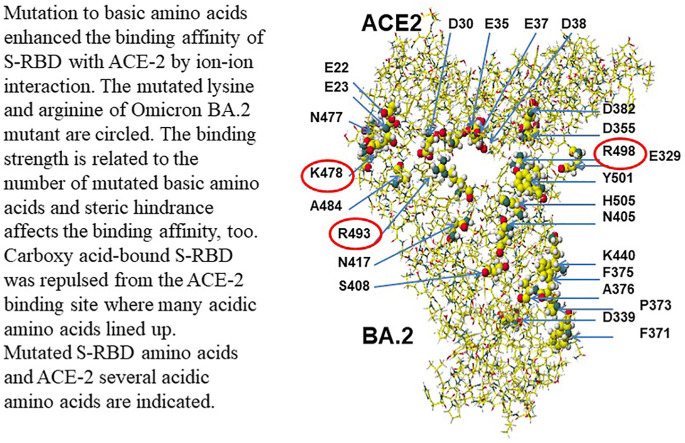

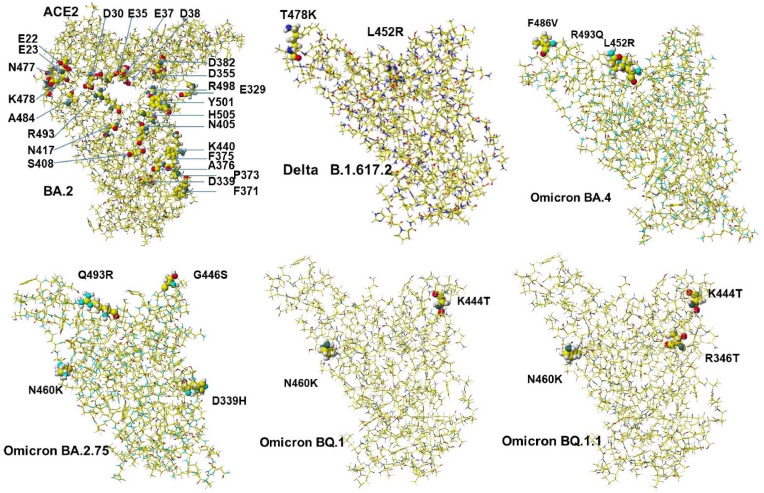

However, variants Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 have become widely spread viruses. Their S-RBD mutations are the same. Only two mutations actually happened, and the primary mutant is L452R. The calculated MIFS energy value is 344.6 kcal mol−1, and the value is similar to that of W.T. The binding strength is neglectable, but the simple mutation may speed up the multiplication. Another variant Omicron BA.2.75 actually has three mutants (D339H, G446S, N460K). The MIFS energy value was 515.1 kcal mol−1, which was similar to that of the Delta-plus (511.3 kcal mol−1). Recently, the variants Omicron BQ.1 and BQ.1.1, were emerged and were replacing Omicron BA.4 and BA5. Their MIFS energy values were not high, and their basic amino acid K460 is far from the binding site with ACE-2. The spreading reason was considered based on their rapid multiplication [8]. The necessary complicated multi-mutation Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 variants may have weak multiplication; however, Omicron BA.2.75 should be carefully monitored not to spread like the Delta variant. The location of mutated amino acids of Delta, Omicron BA.2, Omicron BA.4, Omicron BA.2.75, Omicron BQ.1, and Omicron BQ.1.1 are indicated in Fig. 1 . These calculated MI values are summarized in Table 1 . Figures of BA.2 and Delta B.1.617.2 are reference structures for their comparison.

Fig. 1.

Structure of ACE-2 complexes with S-RBD of Delta, Omicron BA.2 with ACE-2, BA.2.75, BA.4 (BA.5), BQ.1 and BQ.1.1.

Table 1.

Molecular interaction energy values between ACE-2 and SARS-CoV-2 mutants.

| Mutant MIFS MIHB MIES MIVW |

|---|

| WT 346.0675 284.725 186.499–58.491 |

| Delta B.1.517.2594.1785 321.588 426.310–70.623 |

| Delta-plus AY.1511.2668 353.568 264.584–53.387 |

| Omicron BA.1761.7122 389.186 484.065–60.100 |

| Omicron BA.2904.3286 475.158 576.588–73.122 |

| Omicron BA.2.75 515.1229 288.025 282.777–27.122 |

| Omicron BA.4&5344.6077 175.479 166.0875–62.349 |

| Omicron BQ.1309.9460 248.473 97.942–3.738 |

| Omicron BQ.1.1364.6182 300.761 114.112–17.027 |

Critical amino acid residues are indicated as 0.5 atomic sizes, and other amino acids are done as 0.02 atomic sizes. The location of ACE-2 aspartic acid (D) is indicated. Another acidic amino acid is glutamic (E). Black, dark gray, light gray, and white balls are oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, and hydrogen.

The Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 demonstrated the strongest binding affinity; however, the multiplication was expected slow, and our defense (immune) system should overcome the spreading. However, the Covid-19 virus changed its strategy and produced Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 variants (variants of concern) that mutate only three amino acids of S-RBD, and their multiplication speed is considered fast, and it became the main Covid-19 virus, now. Omicron BA.2.75 is recognized as a variant of interest due to its transmissibility.

The additional 79 inhibitor candidates were studied to determine whether they would inhibit the S-RBD binding with ACE-2. The calculated MIFS, MIHB, MIES, and MIVW values are summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Molecular interaction values between an analyte and ACE-2.

| ]Compound [ref] | MIHB | MIES | MIVW | XlogP | logP* | pKa* |

| Absinthin [21] | 24.991 | 4.611 | 19.358 | 2.2 | ||

| Aesculetin [22] | 56.528 | 15.021 | −3.040 | −2 | ||

| Angelicin [22] | 4.024 | 6.277 | 1.862 | 2 | 2.08(S) | |

| Artecanin [23] | −7.827 | 9.904 | 16.913 | 0.2 | ||

| Asperagenin [21] | 42.577 | 25.362 | 13.564 | 3.9 | ||

| Aspirine-O-mannoside methylester | 146.306 | 36.721 | 9.076 | |||

| Baicalin [24] | 72.096 | 21.502 | 5.309 | 1.1 | ||

| Berberine [24] | 19.849 | 7.162 | 15.118 | 3.6 | ||

| Bergapten [22] | 61.680 | 13.776 | 3.624 | 2.3 | 1.93(E) | |

| Budesonide [25] | 39.565 | 3.638 | 10.409 | 2.5 | 1.914(D) | |

| m-Carboxy-l-tyrosine methylester | −42.521 | −36.950 | 25.828 | |||

| m-Carboxy-l-tyrosine methylester | ||||||

| mannoside | −38.815 | −37.112 | 28.540 | |||

| Carmofur [26] | 32.058 | 8.183 | −7.103 | 2.6 | 2.63(E) | |

| Carolacton (M) [27] | 90.786 | 34.017 | 13.273 | 3.4 | ||

| Carolacton (I) | 49.382 | 3.561 | −3.051 | |||

| CHEMBL2171598 [25] | 56.611 | 34.619 | 24.789 | 7.1 | ||

| Chloroquine [26,[28], [29], [30]] | 41.069 | 16.030 | 11.630 | |||

| Cinanserin [26] | 93.928 | 46.517 | −11.833 | 4.1 | ||

| Clofazimine [31] | −8.091 | −24.558 | 21.147 | 7.1 | 7.66 (D,E) | 8.51(D) |

| Dalcetrapib [32] | −3.442 | 3.277 | 21.218 | 7.1 | ||

| Dasatinib [33] | 59.391 | 4.710 | 21.513 | 3.6 | 1.8 (D,HM) | |

| Deguelin [24] | 29.416 | 22.198 | 15.848 | 3.7 | ||

| 2,6-Deoxyactein [21] | 40.586 | 3.839 | 24.837 | 3.9 | ||

| Dexamethasone [34] | 178.940 | 44.341 | −15.208 | 1.9 | 1.83(H) | |

| Disulfiram [26] | 34.658 | 3.467 | 14.802 | 3.9 | 3.88 | |

| Dolutegravir [35] | 83.004 | 34.956 | 3.494 | 2.4 | 2.2 | |

| Dorsilurin E [36] | 195.398 | −7.930 | −17.266 | 3.9 | 3.88(H) | |

| Ebselen [26] | 62.609 | 32.602 | 6.118 | – | ||

| EIDD-2801 [27], | 113.580 | 44.426 | 2.170 | −0.8 | ||

| Emetine [27] | 47.286 | 1.543 | 4.784 | 4.7 | 5.77, 6.64(HS) | |

| Emodin [26] | 58.023 | 4.345 | −1.169 | 2.7 | ||

| Etravirine [35] | −2.536 | 5.482 | 23.965 | 4.5 | ||

| Eugenol [24] | 55.699 | −4.692 | 10.954 | 2 | 2.27(E) | 10.19(D) |

| Evodiamine [24] | 13.125 | 7.648 | 11.834 | 3.1 | ||

| Favipiravir [26,[37], [38], [39]] | −34.055 | −32.693 | 16.672 | −0.5 | 5.1(D) | |

| Flavanone [40] | 41.321 | 1.408 | 7.738 | |||

| Fluvoxamine [25,41] | 43.850 | 10.628 | −5.581 | 2.6 | 3.2(D) | |

| Fluoxetine [25] | 7.449 | 4.715 | 15.166 | 4 | 4.05(D)- | |

| Hecogenin [21] | 27.224 | 17.992 | 11.173 | 4.8 | ||

| Heraclenin [22] | 10.100 | 3.894 | 18.997 | 2.2 | ||

| Heraclenol [22] | 24.340 | 4.703 | 5.210 | 1.2 | ||

| Homoharringtonine | ||||||

| (Omacetaxine mepesuccinate) [29] | 85.605 | 65.102 | 7.787 | 0.8 | ||

| (2R,3S,4S,5S,6R)-6-(Hydroxymethyl)- oxane-2,3,4,5-tetrol [26] | 48.840 | 16.969 | −9.645 | −2.6 | ||

| 2-Hydroxypropane-1,2,3- tricarboxylic acid (M) [26] | 38.858 | 17.744 | −2.030 | −1.7 | ||

| 2-Hydroxypropane-1,2,3- | ||||||

| tricarboxylic acid (I) | repulsed | |||||

| Imperatorin [22] | 56.808 | 23.858 | 4.483 | 3.4 | 2.983 | |

| Indinavir [35,41] | 66.626 | 5.283 | 15.868 | 2.8 | 2.9(D),3.49(E) | |

| Kazinol-A [42] | 50.404 | 64.987 | 6.795 | 6.6 | ||

| Kurarinone [24] | 39.696 | 3.256 | 10.240 | 5.6 | ||

| Laninamivir (Inavir) [38] | 59.592 | 24.819 | −3.599 | −3.2 | ||

| Limonin [21] | −5.413 | 4.090 | 20.745 | 1.8 | ||

| Limonoid [43] | 70.553 | 26.388 | 8.003 | |||

| Oleandrin [44] | 5.989 | −0.327 | 28.278 | 2.4 | 2.53(HS) | |

| Oxepeucedanin [22] | 6.371 | 7.904 | 17.283 | 2.6 | 2.55(HS) | |

| Peramivir (Rapivab) [38] | 37.872 | 25.813 | 13.216 | 0 | ||

| PGG (1,2,3,4,6-Penta-O-galloyl-β- | ||||||

| d-glucose) [24] | 106.966 | 17.225 | −8.799 | 3.6 | ||

| Procyanidin [24] | 83.264 | 24.991 | −13.070 | 2 | ||

| Psoralen [22] | 20.576 | 12.800 | 1.547 | 2.3 | 1.67(E) | |

| Quercetin-7-O-glucoside [24] | 43.254 | 21.447 | 9.830 | 0.4 | ||

| Raltegravir [35] | 68.484 | 32.632 | −5.509 | 1.1 | 0.40 (HS) | |

| Resveratrol [45] | 21.596 | 8.489 | 5.493 | 3.1 | 3.1(HS) | 8.99,9.63,10.64(HS) |

| Ribavirin [26,29] | 53.518 | 23.421 | 8.328 | −1.8 | −1.85(D) | |

| SaikosaponinA [24] | 54.456 | 25.843 | 14.237 | 2.5 | ||

| Saquinavir [33,41] | 133.586 | 58.456 | 5.561 | 4.2 | 3.8(D), 4.7(E) | |

| Sanggenol F [36] | 21.400 | 20.625 | 14.030 | F5.2 | ||

| Sanggenol L [36] | 36.708 | 18.802 | −5.954 | L5.3 | ||

| Savinin [42], | −4.988 | 0.181 | 22.904 | 3.6 | ||

| Saxalin [22] | 2.851 | 2.749 | 19.408 | 2.9 | ||

| Schizanthine Y [23] | −5.257 | 2.240 | 18.725 | D2.8, A5.3 | ||

| Shizukaol A [21] | 12.107 | 9.477 | 13.054 | 2.3 | ||

| Sildenafil [33] | 10.306 | 2.023 | 27.418 | 1.5 | 1.9(D), 2.75€ | |

| Tadalafil [33] | 6.996 | 6.654 | 17.179 | – | ||

| Theaflavin-3,3-digallate [42] | 63.911 | 28.390 | 21.023 | 3.2 | ||

| Tideglusib [26] | 15.821 | 8.800 | 21.432 | 4.3 | 3.28(D) | |

| Timosaponin A-1 [21] | 34.063 | 12.904 | 14.588 | 4.9 | ||

| Tipranavir [35] | 27.923 | 16.549 | 18.736 | 7 | 6.9(D) | |

| Toddacoumaquinone [22] | 28.005 | 19.471 | 7.079 | 3.6 | ||

| Tomentosolic acid [21] | −0.003 | 8.259 | 18.830 | 6.1 | ||

| Triterpenoids [43] | 84.022 | 40.515 | −11.814 | 3.9 |

(M), (I): molecular and ionized compounds; MIFS, MIHB, MIES, MUVW: Molecular interaction energy value of the final (optimized) structure, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic and van der Waals interaction (unit: kcal.mol−1).

*logP and pKa from PubChem: D(Drug Bank), E(EPA DSSTox), H(Hansch logP), S(Sangster), Ch(ChEMBL), H.S. (Hazardous substance data bank).

The binding inhibitor candidates were m-carboxyl-l-tyrosine, citric acid, and the citric acid glycosides, ferulic acid, gallic acid, glycyrrhizic acid, ibuprofen, lactic acid, malic acid, mefenamic acid, nalidixic acid, and naproxen [20], modified PF07321332, and modified gallocatechin gallate [15], and 2-Hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid. Only acidic compounds were repulsed from ACE-2. The modification of the phenolic hydroxy group or a cyano group to the carboxy group may avoid the adsorption at the contact site of ACE-2. However, this study did not analyze the binding affinity of monoclonal antibodies due to their uncertain stereo structures in physiological conditions.

Further study is required for the proposed compound to predict the toxicity and the docking with SARS-CoV-2 protein and whether the new compounds may block the multiplication or not. The latter analysis requires a supercomputer. A new type of designed multiplex SARS-CoV-2 vaccine was proposed. The universal adjuvant-free nano-vaccine platform by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats engineering of bacteriophage T4 in which multiple targets can be incorporated into a single-phase scaffold to rapidly generate various vaccine candidates against any emerging pathogen during epidemic or pandemic situations [46]. The overall adjusted hazard ratio for SARS-CoV-2 infection was 0.47 and 0.51 after previous natural infection versus Pfizer and Moderna vaccination [47]. We have to make multi approaches to control coming new viruses.

4. Conclusion

Omicron BA.2 valiant demonstrated the highest binding strength with ACE-2 among various variants, including Delta valiant; however, Covid-19 changed the strategy, and it changed to a few mutations of Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 variants to enhance the multiplication; even the Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 variants' binding strength was weakened. The new variants, Omicron BQ.1 and BQ.1.1's binding strength, was also weakened; however, these variants are replacing Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 by multiplication. The candidate inhibitors for blocking the S-RBS and ACE-2 binding should be carboxy compounds repulsed from ACE-2 because several acidic amino acids exist at the ACE-2 contact site. The steric hindrance and the number of basic amino acids of variants affect the binding affinity. In the Omicron virus multiplication process, supplying excess basic amino acids is required. The “Healthy eating” report presented the regional food habitude, suggesting transmissibility and mortality are very high in certain countries. Excess eating of dairy and animal protein seems to relate to the urgent problem.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Editorial Cocid-19, a pandemic or not? www.thelancet.com/infection. 2020;20:383. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30180-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horton R. Offline: Covid-19 is not a pandemic. 2020;396:874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32000-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shmerling R.H. Harvard Health Publishing; October 26 2022. Is the Covid-19 Pandemic Over,or Not? [Google Scholar]

- 4.Topol E. An optimistic outlook. Ground Truths. November 7, 2022:1–7. Daily pandemic update #6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control SARS-CoV-2 variants of dashboard 10 Nov. 2022 http://www.ecdc.eu/en/covid-19/variant-concern [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scudellari M. How SARS-CoV-2 infects cells – and why Delta is so dangerous. Nature. 2021;595:640–644. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-02039-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prillaman M. Prior omicron infection protects against BA.4 and BA.5 variants. Nature News. 2022;21 doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-01950-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.E.Topol, The BA.5 story, the takeover by this omicron sub-variant is not pretty, Ground Truths, November 8, 2022.

- 9.Tuekprakhon A., Nutalai R., Dijokaite-Guraliu A., Zhou D., Ginn H.M., Selvaraj M., Liu C., Mentzer A.J., Supasa P., Duyvesteyn H.M.R., Das R., Skelly D., Ritter T.G., Amini A., Bibi S., Adele S., Johnson S.A., Constantinides B., Webster H., Temperton N., Klenerman P., Barnes E., Dunachie S.J., Crook D., Pollard A.H., Lambe T., Goulder P., Paterson N.G., Williams M.A., Hall D.R., Fry E.E., Huo J., Mongkolsapaya J., Ren J., Stuart D.I., Screaton G.T. Antibody escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 from vaccine and BA.1 serum. Cell. 2022;185:2422–2433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.005. e13 Epub 2022 Jun 9] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheward D.J., Kim C., Fischbach J., Muschiol S., Ehling R.A., Bjorkstrom N.K., Hedestam G.B.K., Reddy S.T., Albert J., Peacock T.P., Murrell B. Evasion of neutralizing antibodies by omicron sublineage BA.2.75. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, Sept 1 (2022 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00524-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staufer O., Gupta K., Bucher J.E.H., Kohler F., Sigl C., Singh G., Vasileiou K., Relimpio A.Y., Macher M., Fabritz S., Dietz H., Adam E.A.C., Schaffitzel C., Ruggieri A., Platzman I., Berger I., Spatz J.P. Synthetic virions reveal fatty acid-coupled adaptive immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:868. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28446-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Y. Hu, E.M. Lewandowski, H. Tan, X. Zhang, R.T. Morgan, X. Zhang, L.M.C. Jacobs, S.G. Bitler, M.V. Gongora, J. Choy, X. Deng, Y. Chen, J. Wang, bioRxiv preprint doi://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.28.497978.

- 13.Doctrow B. How COVUD-19 variants evade the immune response. NIH Research Matter. June 8, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 14.P. Han, L. Li, S. Liu, Q. Wang, D. Zhang, Z. Xu, P. Hana, X. Li, Q. Peng, C. Su, B. Huang, D. Li, R. Zhang, M. Tian, L. Fu, Y. Gao, X. Zhao, K. Liu, J. Qi, G. Gao, P. Wang, Receptor binding and complex structures of human ACE2 to spike RBD from omicron and delta SARS-CoV-2, Cell, 185 (202) 630-640. 10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Hanai T. Quantitative in silico analysis of SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD omicron mutant transmissibility. Talanta. 2022;240 doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2022.123206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozlov M. Omicron overpowers key CONID antibody treatments in early tests. Nature. 2021 doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03829-0. Dec 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamasoba D., Kosugi Y., Kimura I., Fujita S., Uriu K., Ito J., Sato K. Neutralisation sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants to therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. www.thelancet.com/infection. 2022;22:942. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00365-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hentzien M., Autran B., Pitoh I., Yazdanpanah Y., Calmy A. A monoclonal antibody stands out against omicron subvariants: a call to action for wider access to Bebtelovimab. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00495-9. www.thelancet.com/infection 22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu X., Mannar D., Srivastava S.S., Berezuk A.M., Demers J.-P., Saville J.M., Leopold K., Li W., Dimitrov D.S., Tuttle K.S., Zhou S., Chittori S., Subramaniam S. Cryo-electron microscopy structures of the N501Y SARA-CoV-2 spike protein in complex with ACE2 and 2 potent neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Biol. 2021;19 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001237. 1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanai T. T. Hanai, Quantitative Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Variants Transmissibility, & S-RBD and ACE-2 Docking Inhibitors: T. Hanai, (Ed.) Quantitative in Silico Analytical Chemistry. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility and the protein structures, HYAKUMANBEN TUSHIN,181, (2021) pp. 4-12, (in Japanese), & T. Hanai, Covid-19 transmissibility and food habitude, HYAKUMANBEN TUSHIN,182 (2021) 5–7, (in Japanese) pp. 153–156. 157-159 in English) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vardhan S., Sahoo S.K. Exploring the therapeutic nature of limonoids and triterpenoids against SARS-CoV-2 by targeting nsp13, nsp14, and nsp15 through molecular docking and dynamics simulations. J. Traditional and Complementary Medicine. 2022;12:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar C.S., Ali D., Alarifi S., Radhakrishnan S., Akbar I. J. Inf. Pub. Health. 2020;13:1671–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alfaro M., Alfaro I., Angle C. Identification of potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease from tropane alkaloids from Schizanthus porridges: a molecular docking study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020;761 doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2020.138068. 1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vidoni C., Fuzimoto A., Ferraresi A., Isidoro C. Targeting autophagy with natural products to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Traditional and Complementary Medicine. 2022;12:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ledford H. Hundreds of Covid trials could provide a deluge of new drugs. Nature. 2022;603:25–27. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-00562-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Hoshoudy A.N. Investigating the potential antiviral activity drugs against SARS-CoV-2 by molecular docking simulation. L. Mol. Liq. 2020;318 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.11.3968. 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z., Yang L. Turning the tide; natural products and natural-product-inspired chemicals as potential counters to SARS-Cov-2 infection. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saleh M., Gabriels J., Chang D., Kim B.S., Mansoor A., Mahmood E., Maller P., Ismail H., Goldner B., Willner J., Beldner S., Mitra R., John R., Chinitz J., Skipitaris N., Mountantonakis S., Epstein L.M. Effect of chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, and Azithromycin on the corrected Q.T. interval in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.120.008662\. 496-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boopathi S., Poma A.B., Kolandaivel P. Novel 2019 coronavirus structure, mechanism of action, antiviral drug promises and rule out against its treatment. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynam. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1758788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basha S.H. Coronavirus drugs – a brief overview of past, present and future. J. PeerScoentist. 2020;2 http://journal.peerscientist.com 16. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan S., Yin X., Meng X.Z., Chan J., Ye Z.-W., Riva L., Pache L., Chan C.C.-Y. P.M.Lai, C. Chan, V. Poon, N. Matsunaga, Y. Pu, C-K. Yuen, J. Cao, Liang, T. Kaiming, S. Li, Y. Du, Sheng, X. Wan, S. K-H. Sze, Z. Jinxia, H. Chu. R.K-H. Kok, K. To, D-Y. Jin, R. Sun, S. Chanda, K-Y. Yuen, Clofazimine broadly inhibits coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;593:418–423. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03431-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niesor E.J., Boivin G., Rheaume E., Shi R.V., Lavoie V., Goyette N., Picard M.-E., Perez A., Laghrissi-Thode F., Tardif J.-C. Inhibition of the 3CL protease and SARS-CoV-2 replication by dalcetrapib. ACS Omega. 2021;6(25):16584–16591. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c01797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiao Z., Zhang H., Ji H.F., Chen Q. Computational view toward the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and the 3CL protease. Communication. 2020;8:53–61. doi: 10.3390/computation8020053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jarvis L.M. C&EN; 2020 June 22. Dexamethasone Could Help in Severe Covid-19; the Old, Inexpensive Steroid Appears to Save Lives in a Large U.K. Trial; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Indu P., Rameshkumar M.R., Arunagirinathan N., Al-Dhahi N.A., Arasu M.V., Ignacimuthu S., Raltegravir, Indinavir Tipranavir. Dolutegravir, and Etravirine against main protease and RNA-dependent R.N.A. polymerase of SARS-CoV-2: a molecular docking and drug repurposing approach. J. Inf. Pub. Health. 2020;13:1856. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.10.015. 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jimenez-Avalos G., VargasoRuiz A.P., Delgado-Pease N.E., Olivos-Ramirez G.E., Sheen P., Fernandez-Diaz M., Quiliano M., Zimic M. Covid-19 Working group in Peru, Comprehensive virtual screening of 4.8K flavonoids reveals novel insights into allosteric inhibition of ASRS-CoV-2 Mpro. Sci. Rep. 2021;1115452:1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-94951-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agrawal U., Raju T., Udwadia Z.F. Favipiravir: a new and emerging antiviral option in Covid-19. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 2020;76(4):370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.mjFI.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manzanares-Meza L.D., Medina-Contreras O. SARS-Cov-2 and influenza: a comparative overview and treatment implications. Bol. Med. Hosp. Infant. Mex. 2020;77(5):262–273. doi: 10.24875/bmhim.20000183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu C.-R., Yin W.-C., Jiang Y., Xu H.E. Structure genomics of SARS-CoV-2 and its omicron variant: drug design templates for Dovid-19. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41401-021-00851-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu Z., Yang L., Zhang X., Zhang Q., Yang Z., Liu Y., Wei S., Liu W. Discovery of potential flavonoid inhibitor against COCID-19 3CL proteinase based on virtual screening strategy. Front. Mil. Biosci. 2020;29:Sept. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.556481. https://dpo.org/10.3389/fmolb.2020.556491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall D.C., Jr., Ji H.-F. A search for medications to treat COVID-9 via in silico molecular docking models of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and 3CL protease. Travel med. Inf. Disease. 2020;35 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101646. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swargiary A., Mahmud S., Saleh A. Screening of phytochemicals as a potent inhibitor of 3-chymotrypsin and papain-like proteases of SARS-CoV-2: an in silico approach to combat Covid-19. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynam. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1835729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vardhan S., Sahoo S.K. Exploring the therapeutic nature of limonoids and triterpenoids against SARS-CoV-2 by targeting nsp13, nsp14, and nsp15 through molecular docking and dynamic simulations. J. Traditional and Complementary Medicine. 2022;12:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halford B. What is oleandrin, the compound touted as a possible COVID-19 treatment? Scientists warn that the natural botanical product is unproven and could have lethal side effects. C&EN, Aug. 2020;31:6. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah M., Woo H.G. 2021. Omicron: A Heavily Mutated SARS-CoV-2 Variant Exhibits Stronger Binding to ACE2 and Potently Escapes Approved COVID-19 Therapeutic Antibodies, bioTxiv. preprint doi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu J., Ananthaswamy N., Jain S., Batra H., Tang W.-C., Lewry D.A., Richards M.I., David S.A., Kilgore P.B., Rao V.B. A universal bacteriophage T4 nanoparticle platform to design multiplex SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates by CRISPR engineering. Sci. Adv. 2021;7:37. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abh1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chemaitelly H., Ayoub H.H., AlMukdad S., Coyle P., Tang P., Yassine H.M., Al-Khatib H.A., Smatti M.K., Hasan M.R., Al-Kanaani Z., Al-Kuwari E., Jeremijenko A., Kaleeckal A.H., Latif A.N., Shaik R.M., Abdul-Rahim H.F., Nasrallah G.K., Al-Kuwari M.G., Butt A.A., Al-Romaihi H.E., Al-Thani M.H., Al-Khal A., Bertollini R., Abu-Raddad L.J. Protection from previous natural infection compared with mRNA vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 in Qatar: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Microbe. 2022:12. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00287-7a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.