Abstract

Porphyromonas gingivalis is one of the pathogens associated with periodontal diseases, and its protease activity has been implicated as an important virulence factor. Kgp is the major Lys-gingipain protease of P. gingivalis and appears to be involved not only in enzyme activity but also in hemagglutination and the pigmented phenotype due to heme accumulation and/or hemoglobin binding. However, little information concerning the molecular mechanism for the spontaneous generation of pigmentless P. gingivalis mutants is currently available. In this study, several spontaneous pigmentless mutants of P. gingivalis were isolated and characterized. The results revealed that a portion of the kgp gene had been deleted from the chromosomes of the pigmentless mutants. This deletion appears to result from recombination between the highly homologous DNA sequences encoding the adhesin domains of the tandemly arranged hagA and kgp genes on the chromosomes of P. gingivalis strains.

Porphyromonas gingivalis, a gram-negative anaerobic bacterium, has been recognized as one of the major etiologic agents of human periodontal diseases. It is known that this organism produces a variety of potential virulence factors, and proteases have been implicated as important virulence factors of this organism (2, 13, 16, 19, 20, 31, 32). Two of these enzymes, Arg-gingipain A (RgpA) and Lys-gingipain (Kgp) (16, 21–23, 31), have been shown to contain highly homologous adhesin domains. These conserved sequences are also present in the large hemagglutinin HagA of P. gingivalis (7, 11). Recent data suggests that the precursor of Kgp comprises at least four domains: the signal peptide domain, the amino-terminal propeptide domain, the catalytic protease domain, and the carboxyl-terminal hemagglutinin domain (2, 12, 21, 22). Kgp has been implicated in the destruction of periodontal tissues and the disruption of host defense mechanisms due not only to its catalytic activity but also to its involvement in hemagglutination, heme accumulation, and hemoglobin binding by P. gingivalis (2, 3, 5, 8–10, 12–14, 18, 19, 21–29).

Previously, a pigmentless variant of P. gingivalis W50, W50/BE1, was isolated following chemostat culture (4, 15). This strain was altered in protease, collagenase, and hemagglutination activities and proved to be avirulent in a mouse abscess model system. However, the molecular basis for the spontaneous generation of pigmentless P. gingivalis mutants has not yet been determined. In addition, recent results (17, 19, 26) have implicated the kgp gene in the pigmentation phenotype. To gain further insight into this phenomenon, several spontaneously generated pigmentless mutants of strain 381 were isolated and analyzed. Our results suggest that one mechanism for the spontaneous development of pigmentless mutants is the generation of deletions of portions of the hagA and kgp genes following homologous recombination between the tandemly arranged hagA and kgp genes.

Isolation and identification of spontaneous pigmentless P. gingivalis mutants.

P. gingivalis 381 and its variants MT10, G102, and WK, which are protease-deficient mutants with insertionally inactivated rgpA (31), rgpB (30), and prtT genes (29), respectively, were grown anaerobically (5% CO2, 10% H2, 80% N2) in enriched TSB medium (containing, per liter, 40 g of tryptic soy broth [TSB; Difco, Detroit, Mich.], 5 g of yeast extract [Difco], 0.5 g of cysteine, 10 mg of hemin, and 1 mg of vitamin K1) and maintained on tryptic soy blood agar (TSA) plates (containing, per liter, TSB plus 15 g of agar and 50 ml of sheep blood) (29). For growth of the antibiotic resistance strains, antibiotics were added to the media at the following concentrations: 50 μg/ml for gentamicin and 10 μg/ml for erythromycin (29). A few pigmentless colonies of WK, MT10, and G102 developed spontaneously on the TSA plates streaked with these strains. Each colony was passaged twice on TSA plates to isolate stable white colonies and named WK-W, G102-W, and MT10-W. These pigmentless colonies remained white on TSA plates for at least 3 to 4 weeks and then gradually became light brown in color. The shape, size, and odor of these white colonies were similar to those features of the corresponding black-pigmented colonies. The frequency of appearance of white colonies varied with each strain and was approximately 10−6. However, no such colonies were obtained on the TSA plates from the parental strain, 381, under identical conditions. This suggested that protease deficiency may increase the rate of appearance of the pigmentless colonies. Additional studies will be necessary to determine if this increased rate is a direct or an indirect effect.

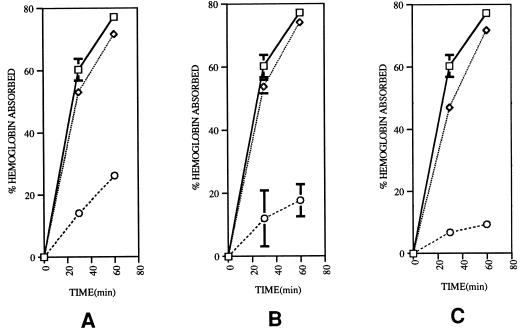

It is generally recognized that P. gingivalis requires hemin for growth and that the characteristic pigmentation produced by P. gingivalis colonies on blood agar plates is due to the accumulation of hemin on the cell surface from hemoglobin in the blood agar (17, 26, 27). Therefore, we investigated the hemoglobin binding activities of the mutants. A hemoglobin binding assay was modified according to the work of Okamoto et al. (19) and Genco et al. (6). Briefly, P. gingivalis was grown anaerobically in enriched TSB overnight. The cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cell density of the suspension was adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.70, and hemoglobin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was added to a final concentration of 250 μg/ml. A 1.0-ml aliquot was immediately removed and centrifuged for 1 min at 10,000 × g in an Eppendorf tube to pellet the cells. The absorbance of the supernatant fluid was then measured at 415 nm. The remaining cells were incubated at 37°C under anaerobic conditions and assayed at 30 and 60 min for residual hemoglobin in the supernatant. P. gingivalis cultures resuspended in PBS without hemoglobin served as controls. Absorbed hemoglobin was evaluated by the decrease of absorbance of the supernatant fluid and recorded as the percentage of initial hemoglobin. All of the pigmentless mutants, WK-W, G102-W, and MT10-W, showed significant decreases in hemoglobin binding activity (Fig. 1). MT10-W was the most strongly attenuated in hemoglobin binding activity of the pigmentless strains.

FIG. 1.

Hemoglobin binding assay of P. gingivalis strains. The cell suspensions in PBS were incubated anaerobically with bovine hemoglobin at pH 7.4 and 37°C for 30 to 60 min and centrifuged. The absorbance of the suspensions at 415 nm was then measured. The decrease in absorbance was used to calculate hemoglobin binding. Shown are hemoglobin binding results with strains 381 (□), WK (◊), and WK-W (○) (A); with strains 381 (□), G102 (◊), and G102-W (○) (B); and with strains 381 (□), MT10 (◊), and MT10-W (○) (C). Bars represent the standard deviations of results of duplicate samples.

Recently, a prominent 19-kDa protein was identified and purified from P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 by Nakayama et al. (17) and proposed to function as a hemoglobin receptor protein. The nucleotide sequence encoding this protein is present within the rgpA, kgp, and hagA genes of P. gingivalis. Furthermore, the hemoglobin receptor protein was not expressed in pigmentless mutants isolated from the W50 strain of P. gingivalis (15, 17). The ability of these mutants to bind hemoglobin was also markedly decreased. The kgp-deficient mutant KDM35, constructed following insertional inactivation of the kgp gene, binds hemoglobin to a lesser extent than the kgp+ sibling strain KDM16. Since recent results in our laboratory (29) suggested that inactivation of the rgpA gene resulted in reduced transcription of the kgp gene, the integrity of the rgpA gene in the pigmentless mutants was examined. It was confirmed that the rgpA gene appears to be present on the chromosomes of the pigmentless mutants by Southern blot analysis with chromosomal DNAs digested with XmaI and probed with a 1.4-kb PstI/SmaI fragment of the rgpA gene (data not shown). In order to examine the nature of the kgp gene in these mutants, a pair of primers (PR1, 5′-CAT ACG GAA TGC TCA GGA TCC-3′, and PR2, 5′-CAG GCA CAG CAA TCA ACT TC-3′) which correspond to a subdomain of the amino-terminal sequence of the Kgp protease domain (nucleotides 13178 to 15288) (Fig. 2) were synthesized (Center for Advanced Molecular Biology and Immunology, State University of New York at Buffalo). PCR amplification, with the chromosomal DNAs of all strains as templates, suggested that the 1.0-kb parental fragment (nucleotides 12467 to 13457) could not be amplified from any of the pigmentless spontaneous mutants (data not shown). We also designed primers based upon the nucleotide sequence of the adhesin domain of Kgp and amplified the corresponding 2-kb fragment (nucleotides 16702 to 18717). All of the mutants showed results identical to those of the parental strains (data not shown). Therefore, these results suggested that the 5′ end of the kgp gene appears to have been deleted in the pigmentless mutants.

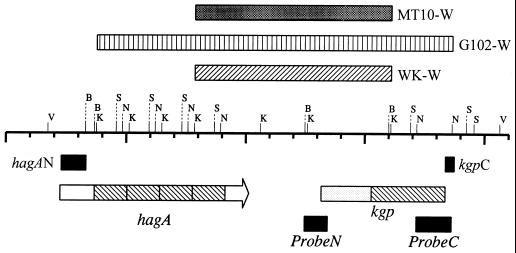

FIG. 2.

Genomic maps of the proposed orientations of the hagA and kgp genes of P. gingivalis 381. The major restriction sites of hagA and kgp are indicated. Restriction sites: K, KpnI (nucleotides 3760, 5116, 6484, 7852, 10606, 12589, and 16087); B, BamHI (nucleotides 3309, 3672, 12484, and 15999); N, NcoI (nucleotides 4840, 6208, 7576, 8944, 17170, and 18643); S, SmaI (nucleotides 4583, 5951, 7319, 8687, 16913, 19245, and 19554); V, Van91I (nucleotides 1741 and 20629). Solid boxes on the map show the probes N (for the Kgp N-terminal protease domain), C (for the Kgp adhesin domain), hagAN (for the exact HagA N-terminal region), and kgpC (for the exact Kgp C-terminal region). Boxes with hatching labeled “hagA” and “kgp” represent the adhesin regions of the hagA and kgp genes, respectively. The stippled box represents the N-terminal domain and protease domain of Kgp. The boxes above the restriction enzyme map with hatching, vertical lines, and shading represent the proposed minimal deleted regions of WK-W, MT10-W, and G102-W, respectively.

The Kgp activities of the pigmentless mutants were also determined following hydrolysis of the synthetic chromogenic substrate benzoyl-dl-lysine p-nitroanilide (BLPNA; Nova, La Jolla, Calif.) (20, 22). All of the pigmentless mutants were significantly decreased in BLPNA hydrolyzing activity. Furthermore, the hemagglutinating activities of the mutants were compared with those of their pigmented counterparts. WK-W and G102-W displayed approximately 50% of the hemagglutinating activities of their parental pigmented strains WK and G102, respectively, while MT10-W was completely devoid of hemagglutinating activity (data not shown). These results are consistent with those of Okamoto et al. (19), who suggested that Kgp appears to play a relatively small role in hemagglutination compared to that of RgpA (16, 31).

Molecular basis for deletions of the kgp gene.

One possible explanation for the spontaneous deletion of portions of the kgp gene is that a recombinational rearrangement occurred. This may result from the presence of highly homologous related sequences in the adhesin domains of rgpA, hagA, and kgp (7, 11, 16, 21, 31). In order for this to occur, the kgp gene should be closely linked to one of these homologous genes. After searching the sequence database at The Institute for Genomic Research (28a) for P. gingivalis W83 with the kgp and hagA sequences, we identified three fragments sequenced from P. gingivalis W83 (contigs 20, 40, and 81) carrying portions of both genes (1). An examination of these fragments suggested that the hagA gene is located upstream of the kgp gene in strain W83. In addition, the hagA gene of strain 381 contains four adhesin domains (1), compared to three homologous domains for W83. Approximately 3 kb separates the hagA and kgp genes on the strain W83 chromosome. Therefore, in order to confirm this arrangement for strain 381, Southern blot analysis was carried out. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from P. gingivalis 381 cells with a Puregene DNA isolation kit by following the protocol of the supplier (Gentra System, Inc., Minneapolis, Minn.). The DNA was digested with several restriction enzymes, separated on 0.8% agarose gels, and transferred to Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (29). Probe N (nucleotides 12484 to 13457), the PCR product amplified with PR1 and PR2, was digested with BamHI and purified with a QIAEX II kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). A 1.4-kb (nucleotides 17170 to 18643) NcoI fragment of the kgp adhesin region was used as probe C (Fig. 2). The labeling of the probes as well as hybridization and detection by the ECL system was performed as recommended by the supplier (Amersham International plc., Amersham, United Kingdom). Southern blot analysis revealed that both probes N (Fig. 3C, lane 1 and C (Fig. 3D, lane 1) hybridized with the same 8.2-kb (nucleotides 8944 to 17170) NcoI fragment, which included portions of both the hagA and kgp genes. This result is consistent with hagA being upstream of the kgp gene (Fig. 2). In order to further confirm this tandem arrangement, a portion of the intervening region (nucleotides 12290 to 12650) between the hagA and kgp genes was amplified by PCR, isolated, and sequenced (data not shown), and the results confirmed the postulated sequence. Nucleotide sequence analyses revealed that the four repeat adhesin regions of the hagA gene of P. gingivalis 381 are approximately 98% identical with the C-terminal adhesin region of its kgp gene. These homologous regions provided a good molecular basis for homologous recombination.

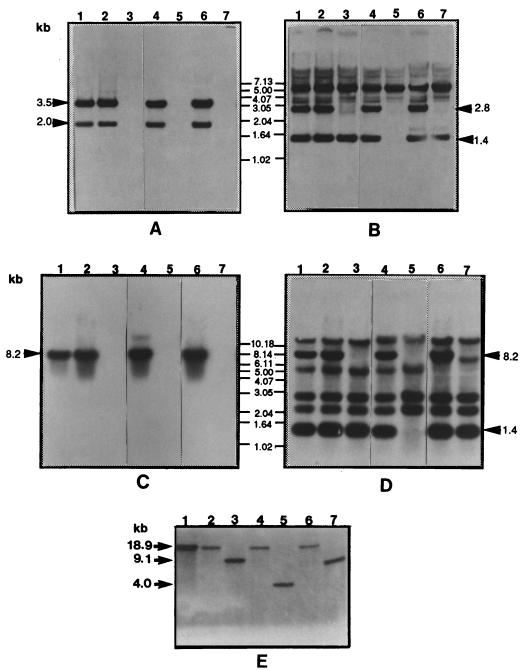

FIG. 3.

Southern blot analysis of genomic DNAs of P. gingivalis strains. (A to E) Southern blots of strain 381 (lanes 1), WK (lanes 2), WK-W (lanes 3), G102 (lanes 4), G102-W (lanes 5), MT10 (lanes 6), and MT10-W (lanes 7). The chromosomal DNAs of the P. gingivalis strains were digested with the following restriction enzymes and hybridized with the following probes: KpnI and probe N (A), KpnI and probe C (B), NcoI and probe N (C), NcoI and probe C (D), and Van91I and probe hagAN (E).

In order to determine which portions of the kgp gene were deleted in each mutant, several Southern blot analyses were carried out (Fig. 3A to D). An analysis of the Southern blotting patterns revealed that probe N hybridized with 2.0-kb (nucleotides 10606 to 12589) and 3.5-kb (nucleotides 12589 to 16087) KpnI fragments (Fig. 3A) and an 8.2-kb NcoI fragment (Fig. 3C) from the pigmented strains 381, WK, G102, and MT10 but not with the corresponding fragments from the spontaneous pigmentless mutants WK-W, G102-W, and MT10-W. Probe C hybridized with 1.4-kb KpnI fragments from all of the strains except G102-W and also reacted with 2.8-kb (nucleotides 7852 to 10606) fragments from strains 381, WK, G102, and MT10 but not from the pigmentless mutants (Fig. 3B). The 1.4-kb bands from G102-W probed with probe C also were not reactive when G102-W DNA was digested with NcoI (Fig. 3D) or SmaI (data not shown). Probe C hybridized to six separate NcoI fragments from the chromosomal DNA of P. gingivalis 381. The 1.4-kb fragment may contain one or more of the repeat regions of the hagA and kgp genes. There were no 8.2-kb bands from any of the pigmentless mutants (Fig. 2 and 3D). The other positive bands likely derived from the domains of the other homologous genes such as rgpA (23) which have homology with probe C. The ∼5.5-kb fragments (Fig. 3D, lanes 1 to 5), which could be probed by the rgpA gene fragment (data not shown), shifted to 7.5 kb because of the insertion of the 2-kb erythromycin cassette with MT10 and MT10-W (Fig. 3D, lanes 6 and 7). From these Southern blot analyses, we determined that minimal regions of approximately 8.2, 14.9, and 8.2 kb, depicted in Fig. 2, of the chromosomal DNAs from WK-W, G102-W, and MT10-W had been deleted. This likely results from homologous recombination between the homologous adhesin domain sequences of hagA and kgp. In order to determine if a fragment of genomic DNA containing the hagA and kgp genes that was larger than the part indicated in Fig. 2 was deleted, two pairs of primers for both the precise hagA N terminus and the kgp C terminus were designed (hagAN5′, CCT ATT GTG TTG GGG ACA GAC; hagAN3′, AGT TCA TCG GAG CAG GTT TG; kgpC5′, AAT TCT GTC TTG GAC TCG GAG; and kgpC3′, GCT CGT ACA AGT AGC TCC TCA). Analyzed by PCR, 1-kb (hagAN) and 0.38-kb (kgpC) fragments specific for the hagAN and kgp C termini were amplified from all of the strains. Southern blot analyses were also carried out by probing the KpnI-digested DNA with hagAN and the NcoI-digested DNA with kgpC. The same profile was observed for all of the strains (data not shown). These results suggested that both hagAN and kgpC termini were present on the chromosomal DNAs from all of the pigmentless mutants. In order to obtain further convincing evidence, additional Southern blot analysis was done (Fig. 2 and 3E). Chromosomal DNAs were cut outside both the hagA and kgp genes (nucleotides 1741 and 20629) by the restriction enzyme Van91I and probed with the hagAN probe. The results showed an 18.9-kb band with wild-type 381 and WK, G102, and MT10, a 4-kb band with G102-W, a 9.1-kb band with WK-W, and a similarly sized, approximately 8- to 9-kb band with MT-10. Therefore, it appears that approximately 1.6- and approximately 1.7- to 2.7-kb regions have been deleted from WK-W and MT10, respectively, in addition to the postulated minimal deleted region depicted in Fig. 2. It is difficult to more precisely define the deleted regions, which may be at either side of the depicted regions, since no additional convenient restriction sites are apparent. Furthermore, the precise recombination junctions cannot be accurately determined because of the extremely high nucleotide homologies between the adhesin domains of the two genes. Nevertheless, these results indicated that pigmentless mutants of P. gingivalis deficient in hemoglobin binding can be generated following homologous recombination between the adhesin domain sequences of the tandemly arranged kgp and hagA genes. In addition, these results suggest, but do not prove, that the catalytic activity of Kgp is required for the pigmented phenotype since the Kgp adhesin domain essentially remains intact following recombination. However, we cannot formally rule out the possibility that such a recombination event results in an undetected modification of the Kgp adhesin structure. Finally, other mechanisms of spontaneous Kgp inactivation involving transposons (14) or nonsense mutations might also generate pigmentless mutants and these alterations might affect the growth of these mutants in environments where iron is available in the form of hemoglobin.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Han for advice in this study.

This investigation was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant DE08293.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J H, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST—a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkocy-Gallagher G A, Han N, Patti J M, Whitlock J, Progulske-Fox A, Lantz M S. Analysis of the prtP gene encoding porphypain, a cysteine protease of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2734–2741. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2734-2741.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calkins C C, Platt K, Potempa J, Travis J. Inactivation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha by proteases (gingipains) from the periodontal pathogen, Porphyromonas gingivalis. Implications of immune evasion. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6611–6614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collinson L M, Rangarajan M, Curtis M A. Altered expression and modification of proteases from an avirulent mutant of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50 (W50/BE1) Microbiology. 1998;144:2487–2496. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujimura S, Hirai K, Shibata Y, Nakayama K, Nakamura T. Comparative properties of envelope-associated arginine-gingipains and lysine-gingipain of Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;163:173–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genco C A, Odusanya B M, Brown G. Binding and accumulation of hemin in Porphyromonas gingivalis are induced by hemin. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2885–2892. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2885-2892.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han N, Whitlock J, Progulske-Fox A. The hemagglutinin gene A (hagA) of Porphyromonas gingivalis 381 contains four large, contiguous, direct repeats. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4000–4007. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4000-4007.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinode D, Hayashi H, Nakamura R. Purification and characterization of three types of proteases from culture supernatants of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3060–3068. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3060-3068.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imamura T, Potempa J, Pike R N, Travis J. Dependence of vascular permeability enhancement on cysteine proteases in vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1999–2003. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1999-2003.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kadowaki T, Nakayama K, Yoshimura F, Okamoto K, Abe N, Yamamoto K. Arg-gingipain acts as a major processing enzyme for various cell surface proteins in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29072–29076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.29072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozarov E, Whitlock J, Dong H, Carrasco E, Progulske-Fox A. The number of direct repeats in hagA is variable among Porphyromonas gingivalis strains. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4721–4725. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4721-4725.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuboniwa M, Amano A, Shizukuishi S. Hemoglobin-binding protein purified from Porphyromonas gingivalis is identical to lysine-specific cysteine protease (Lys-gingipain) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:38–43. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuramitsu H K. Proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis: what don’t they do? Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1998;13:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1998.tb00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis J P, Macrina F L. IS195, an insertion sequence-like element associated with protease genes in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3035–3042. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3035-3042.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKee A S, McDermid A S, Wait R, Baskerville A, Marsh P D. Isolation of colonial variants of Bacteroides gingivalis W50 with a reduced virulence. J Med Microbiol. 1988;27:59–64. doi: 10.1099/00222615-27-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakayama K, Kadowaki T, Okamoto K, Yamamoto K. Construction and characterization of arginine-specific cysteine protease (Arg-gingipain)-deficient mutants of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23619–23626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakayama K, Ratnayake D B, Tsukuba T, Kadowaki T, Yamamoto K, Fujimura S. Haemoglobin receptor protein is intragenically encoded by the cysteine protease-encoding genes and the haemagglutinin-encoding gene of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:51–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okamoto K, Kadowaki T, Nakayama K, Yamamoto K. Cloning and sequencing of the gene encoding a novel lysine-specific cysteine protease (Lys-gingipain) in Porphyromonas gingivalis: structural relationship with the arginine-specific cysteine protease (Arg-gingipain) J Biochem. 1996;120:398–406. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okamoto K, Nakayama K, Kadowaki T, Abe N, Ratnayake D B, Yamamoto K. Involvement of a lysine-specific cysteine protease in hemoglobin adsorption and heme accumulation by Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21225–21231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otogoto J I, Kuramitsu H K. Isolation and characterization of the Porphyromonas gingivalis prtT gene, coding for protease activity. Infect Immun. 1993;61:117–123. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.117-123.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pavloff N, Pemberton P A, Potempa J, Chen W C, Pike R N, Prochazka V, Kiefer M C, Travis J, Barr P J. Molecular cloning and characterization of Porphyromonas gingivalis lysine-specific gingipain. A new member of an emerging family of pathogenic bacterial cysteine proteases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1595–1600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pike R, McGraw W, Potempa J, Travis J. Lysine- and arginine-specific proteases from Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:406–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pike R N, Potempa J, McGraw W, Coetzer T H, Travis J. Characterization of the binding activities of protease-adhesin complexes from Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2876–2882. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2876-2882.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Potempa J, Pike R, Travis J. The multiple forms of trypsin-like activity present in various strains of Porphyromonas gingivalis are due to the presence of either Arg-gingipain or Lys-gingipain. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1176–1182. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1176-1182.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott C F, Whitaker E J, Hammond B F, Colman R W. Purification and characterization of a potent 70-kDa thiol lysyl-protease (Lys-gingivain) from Porphyromonas gingivalis that cleaves kininogens and fibrinogen. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:7935–7942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah H N, Bonnett R, Matten B, Williams A D. The porphyrin pigmentation of subspecies of Bacteroides melaninogenicus. Biochem J. 1979;180:45–50. doi: 10.1042/bj1800045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slots J, Reynolds H S. Long-wave UV light fluorescence for identification of black-pigmented Bacteroides spp. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:1148–1151. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.6.1148-1151.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smalley J W, Birss A J, Mckee A S, Marsh P D. Hemin regulation of hemoglobin binding by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Curr Microbiol. 1998;36:102–106. doi: 10.1007/s002849900287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28a.The Institute for Genomic Research Website. 1999, copyright date. [Online.] The Institute for Genomic Research. http://www.tigr.org. [20 December 1998, last date accessed.]

- 29.Tokuda M, Chen W, Karunakaran T, Kuramitsu H K. Regulation of protease expression in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5232–5237. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5232-5237.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tokuda M, Duncan M, Cho M-I, Kuramitsu H K. Role of Porphyromonas gingivalis protease activity in colonization of oral surfaces. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4067–4073. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4067-4073.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tokuda M, Karunakaran T, Duncan M, Hanada N, Kuramitsu H K. Role of Arg-gingipain A in virulence of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1159–1166. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1159-1166.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoneda M, Kuramitsu H K. Genetic evidence of the relationship of Porphyromonas gingivalis cysteine protease and hemagglutinin activities. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1996;11:129–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]