Abstract

Indwelling medical devices currently used to diagnose, monitor, and treat patients invariably suffer from two common clinical complications: broad-spectrum infections and device-induced thrombosis. Currently, infections are managed through antibiotic or antifungal treatment, but the emergence of antibiotic resistance, the formation of recalcitrant biofilms, and difficulty identifying culprit pathogens have made treatment increasingly challenging. Additionally, systemic anticoagulation has been used to manage device-induced thrombosis, but subsequent life-threatening bleeding events associated with all available therapies necessitates alternative solutions. In this study, a broad-spectrum antimicrobial, antithrombotic surface combining the incorporation of the nitric oxide (NO) donor S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) with the immobilization of the antifungal Amphotericin B (AmB) on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was developed in a two-step process. This novel strategy combines the key advantages of NO, a bactericidal agent and platelet inhibitor, with AmB, a potent antifungal agent. We demonstrated that SNAP-AmB surfaces significantly reduced the viability of adhered Staphylococcus aureus (99.0 ± 0.2%), Escherichia coli (89.7 ± 1.0%), and Candida albicans (93.5 ± 4.2%) compared to controls after 24 h of in vitro exposure. Moreover, SNAP-AmB surfaces reduced the number of platelets adhered by 74.6 ± 3.9% compared to controls after 2 h of in vitro porcine plasma exposure. Finally, a cytotoxicity assay validated that the materials did not present any cytotoxic side effects toward human fibroblast cells. This novel approach is the first to combine antifungal surface functionalization with NO-releasing technology, providing a promising step toward reducing the rate of broad-spectrum infection and thrombosis associated with indwelling medical devices.

Keywords: multifunctional surfaces, nitric oxide-releasing surfaces, antimicrobial surfaces, hemocompatible, medical device

Graphical Abtract

1. INTRODUCTION

Indwelling medical devices have been plagued with two common clinical complications: infection and device-induced thrombosis. As a conservative estimate, approximately 50% of nosocomial infections are related to medical device use.1 Pathogens can readily colonize into biofilms on the surface of indwelling devices, forming highly structured, often polymicrobial networks of microorganisms embedded within a protective three-dimensional extracellular matrix. Infection is largely managed through the administration of antibiotics, but the emergence of antibiotic resistance has made treatment increasingly difficult. Biofilm matrices have been reported to increase drug resistance by 1000-fold compared to planktonic counterparts, and 60–70% of hospital-acquired infections involve biofilms, resulting in an additional $11 billion in healthcare costs in the United States alone.2,3 Biofilms on indwelling medical devices often also disseminate, leading to widespread bloodstream infections. Systemic administration of antibiotics and antifungals are often used to treat these infections, but the difficulty in penetrating biofilms has led to increased antimicrobial resistance, which ultimately necessitates additional surgeries to remove the infected device.

Moreover, when medical devices are in contact with blood, the presence of a foreign body triggers several adverse reactions including protein adsorption, platelet adhesion and activation, and complement activation, ultimately resulting in device-induced clot formation. These clots can result in total occlusion, impairing device function and increasing risk of embolism. Blood-contacting devices are used to treat thousands of patients daily, but despite the extensive use of these devices, thrombosis and clot formation remain at the forefront of clinical complications associated with these devices.4 Systemic anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapies are currently the clinical standard for preventing device-induced clotting, but subsequent life-threatening bleeding events associated with all available therapies has led to the demand for alternative solutions.5,6

The urgent need to reduce the risk of infection and device-induced clotting has led to the incorporation of nitric oxide (NO) donors into various medical-grade polymers. NO is a key signaling molecule that acts as an endogenous antimicrobial against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial pathogens and an inhibitor of platelet activation within the body.7 S-nitrosothiols (RSNOs) have been integrated with different medical-grade polymers via blending, immobilization, or solvent swelling, and, as a result, NO-releasing devices have minimized platelet aggregation and bacterial viability on different polymeric surfaces.7–9 However, NO-releasing surfaces has been shown to be less successful against fungal pathogens, which require higher doses of NO to be effective.10–12 It has been previously shown that NO’s physiological effect is largely concentration dependent, and at higher doses (which would be required to kill fungal cells) NO has a cytotoxic effect on mammalian cells.13,14 In addition, tailoring a NO-releasing material to maintain this higher NO flux would deplete the NO donor reservoir, which would severely limit long-term applications.

Although significant effort has been placed in combating bacterial pathogens, substantially less has been focused on combating device-related fungal infections. Candida species are the most common opportunistic fungal pathogens globally and are the fourth leading cause of bloodstream infections in the United States with a reported mortality rate of up to 50%.15–17 An increasing number of device-related infections involve Candida species, accounting for $2 billion in healthcare costs yearly.18 Once formed, eradication of biofilms via therapeutic interventions is seldom successful, which causes device failure and removal. Intravenous infusion of antifungal agents such as amphotericin B (AmB) can control fungal infections associated with indwelling devices; however, biofilms are not adequately screened. Therefore, antifungal agents are normally only administered after symptoms do not resolve after 3–7 days of antibiotic therapy.19 Additionally, antifungal agents are often used as a last resort for treating serious infections in critically ill patients due to the extreme side effects including nephrotoxicity, high fever, nausea, and severe rigors.19,20 The side effects associated with antifungal agents are generally more severe than antibacterial agents as the cytotoxic mechanisms used against fungal cells, which are eukaryotic, have a higher chance of targeting mammalian cells, which are also eukaryotic.21 Therefore, a surface modification that elicits antifungal activity while avoiding the side effects associated with systemic administration of antibiotic and antifungal therapies would be clinically advantageous.

Since NO-release can be accomplished by modifying the polymeric matrix of a material, the surface is left unchanged and is capable of surface modification.22,23 Thus, the antifungal efficacy of an NO-releasing surface can be significantly improved by immobilization of an antifungal compound while still retaining its antibacterial and antithrombotic effects. In this study, a dual broad-spectrum antimicrobial/antithrombotic surface was prepared in a two-step process, and the first reported method for covalent surface immobilization of the antifungal agent Amphotericin B was described. The NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) was incorporated into the polymeric matrix of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) via solvent swelling and AmB was immobilized through an EDC/NHS (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide/N-hydroxysuccinimide) coupling method. We demonstrate that the NO-releasing, AmB-immobilized (SNAP-AmB) surface resulted in (1) reduced viability of adhered bacteria and fungi; (2) reduced platelet adhesion; and (3) no cytotoxic effects toward mammalian cells. This novel approach was the first to combine NO-releasing technology with an immobilized antifungal agent and is capable of reducing the rate of broad-spectrum infections and thrombosis associated with indwelling medical devices.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials.

N-acetyl-d-penicillamine (NAP), tetrahydrofuran (THF), sodium nitrite (NaNO2), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES), N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), (3-Aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane (APTMS), Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), and HCl were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Amphotericin B (AmB) was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 138 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, and 10 mM sodium phosphate was used during in vitro experimentation, and phosphate buffer (PB) containing 0.0754 M sodium phosphate heptahydrate and 0.0246 M sodium phosphate monohydrate at 7.4 pH was used for platelet adhesion studies. Trypsin–EDTA was purchased from Corning (Corning, NY). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Penicillin–Streptomycin (Pen-Strep) were purchased from Gibco-Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). The bacterial strains S. aureus (ATCC 6538) and E. coli (ATCC 11303), human fibroblasts (CRL-2522), and C. albicans (ATCC MYA 4441) and Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). LB broth and agar and TS agar and broth were purchased from Difco Laboratories (Detroit, MI). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) kit was purchased from Roche Life Sciences (Indianapolis, IN). Drabkin’s reagent was purchased from Ricca Chemical Company (Arlington, TX).

2.2. SNAP Synthesis.

The method for the synthesis of SNAP was adapted via a previously defined method.24 Briefly, a 1:1 molar ratio of NaNO2 and NAP was added to a solution of DI water and methanol containing 2 M HCl and 2 M H2SO4 and stirred for 30 min. The reaction vessel was then transferred to an ice bath and cooled for 6 h until SNAP crystals precipitated. SNAP crystals were collected via vacuum filtration and dried in a desiccator for 24 h to remove any trace solvent. For the duration of this procedure, the reaction mixture and products were sheltered from light.

2.3. Preparation of SNAP-Impregnated PDMS.

A 25 mg/mL SNAP swelling solution was prepared by dissolving SNAP in THF according to previously optimized NO release kinetics.8,25 PDMS was made by mixing Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer Base at a 10:1 ratio with DOWSIL 184 Silicone Elastomer Curing Agent, which was poured in a mold and allowed to cure overnight. PDMS samples 0.635 cm in diameter and 0.225 cm in thickness were added to the SNAP-THF solution for 24 h (Figure 1a). After swelling, the PDMS was removed, briefly washed in PBS, and dried overnight in the dark at room temperature to allow any excess THF to evaporate. After drying, the samples were immersed in DI water and sonicated for 5 min to remove any SNAP crystals from the surface.

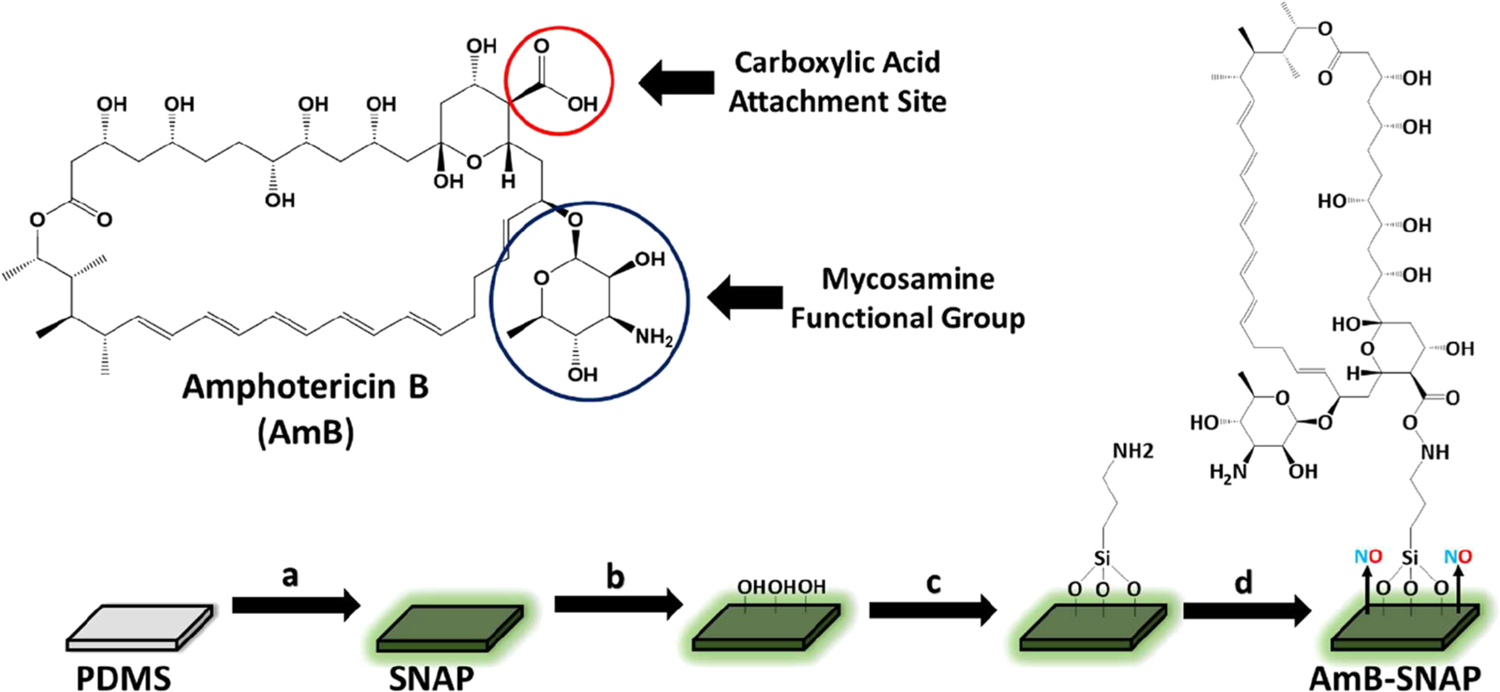

Figure 1.

Schematic of SNAP-AmB synthesis. (a) PDMS is swelled with SNAP using THF at a concentration of 25 mg mL−1. (b) SNAP is exposed to oxygen plasma to force −OH groups onto polymeric surface. (c) APTMS is immobilized onto the surface through chemical vapor deposition. (d) AmB is covalently bound using EDS/NHS coupling.

2.4. Amphotericin B Immobilization.

The antifungal molecule AmB was immobilized onto PDMS substrates using EDC/NHS coupling (Figure 1). EDC/NHS coupling was selected as the coupling method due to it being designed for the immobilization of large biomolecules.26 Prior to EDC/NHS coupling, surfaces were treated with low pressure O2 plasma for 5 min at 30 W to force −OH groups on the surface (Figure 1b), which allows for chemical vapor deposition of APTMS. Once deposited, APTMS forms a layer of primary amines on the surface of the silicone rubber, which allows for EDC/NHS coupling (Figure 1c). Once the aminated surface is formed and verified by FITC labeling, the EDC/NHS coupling reaction is mixed in to allow for proper priming before immobilization onto the surface. EDC reacts with carboxylic acid groups present on AmB, which is then replaced by NHS to form an ester that is considerably more stable than the EDC intermediate, allowing for more efficient conjugation to primary amines. After 10 min passed for the AmB-NHS complex to form, the aminated PDMS substrates were subjected to the reaction mixture to allow for AmB immobilization to the surface (Figure 1d).

2.5. Material Characterization.

2.5.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy-Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS).

SEM was deployed using an FEI Teneo instrument equipped with an EDS system to examine the surface morphology and elemental analysis of the fabricated materials. Samples were sputter-coated with gold–palladium at 10 nm thickness prior to examination using a Leica Sputter Coater system. An accelerating voltage of 5 and 20 kV was used for SEM and EDS, respectively.

2.5.2. Contact Angle.

The static contact angle of samples was measured using a Krüss DSA100 Drop Shape Analyzer (sessile drop method) using 5 μL droplets of deionized water. Care was taken to measure the same area (closest to the center) between samples to avoid inconsistent data collection.

2.5.3. Amphotericin B Quantification and Leaching.

AmB conjugation quantification was determined through UV/vis analysis of the incubation solution before and after EDC/NHS coupling. AmB in aqueous solutions has an absorption peak at 365 nm that is linearly related to its concentration.27 Employing a standard curve, we calculated the concentration of AmB used in the reaction. After the coupling reaction, the samples (n = 8) were briefly sonicated to remove any unbound AmB. The resulting reaction solution was compared to the original solution, and the difference between the two was calculated to be the amount of AmB coupled to the surface (Eq 1).

| (1) |

This same method was used to calculate AmB leaching from the surface. AmB samples (n = 5) were placed within PBS and incubated in physiological conditions. Aliquots of samples were removed at 1, 3, and 7 days, measured at an adsorption peak of 365 nm, and the amount of AmB leached was interpolated using a standard curve.

2.6. Nitric Oxide Release Characterizations.

2.6.1. NO Release Measurements.

NO flux was measured and recorded utilizing Sievers chemiluminescence NO analyzers (NOA 280i, GE Analytical, Boulder, CO, USA). SNAP and SNAP-AmB samples (n = 3) were measured in a dark environment to protect from premature catalysis of NO. A baseline measurement of NO in ppb in the absence of the sample was first established prior to the sample being placed in the sample holder. The samples were kept at 37 °C by a water bath placed around the sample holder. NO released from the samples was purged from the sample holder by a continuous supply of high purity nitrogen maintained at a constant flow rate of 200 mL min−1 into a chemiluminescence detection chamber. NO released measured in ppb was normalized and an NOA constant (mol ppb−1 s−1) was used to convert data to NO flux (×10−10 mol cm−2 min−1). Data was collected over 10 days. Samples were kept submerged in PBS in glass vials at 37 °C in the dark between measurements.

2.6.2. SNAP Loading.

To determine the total quantity of SNAP loaded, samples (n = 3) were submerged in excess THF to remove SNAP into solution. The absorbance of resulting THF solution was subsequently measured using UV–vis at 340 nm to determine the concentration of SNAP originally incorporated via a SNAP-THF calibration curve composed of known SNAP concentrations.

2.7. In Vitro Bacterial Adhesion Assay.

The antimicrobial activity of the materials against bacterial and fungal pathogens was determined using a previously established protocol.28 The antimicrobial activity of the fabricated materials was tested against Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Escherichia coli (E. coli), and Candida albicans (C. albicans) compared to unmodified materials. Isolated colonies of S. aureus and E. coli were each inoculated in LB broth at 37 °C for 16 h at 150 rpm, and C. albicans was inoculated in tryptic soy broth at 37 °C for 24 h at 150 rpm. Each culture was subsequently centrifuged for 7 min at 3500 rpm and washed with sterile PBS (pH 7.4). The culture was centrifuged again for another 7 min at 3500 rpm and the bacteria pellet was suspended with fresh sterile PBS. An optical density measurement at 600 nm was performed to determine the concentration of bacterial cells and dilute the culture to ~108 colony-forming units (CFUs) per mL. In a 24-well plate, 1 mL of the bacterial or fungal suspension was placed into each well containing samples and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C at 150 rpm. Each sample was removed and gently washed with sterile PBS and placed in 1 mL of PBS in a 15 mL centrifuge tube. The immersed sample was then homogenized at 25,000 rpm for 60 s to detach bacteria or fungi from the surface of the sample. The solution containing the bacteria or fungi was serially diluted, plated on LB agar plates (for bacteria) or tryptic soy agar (for fungi), and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Colony-forming units were counted to determine the viable bacterial or fungal colonies per cm2 and assess the effectiveness of microbial inhibition.

2.8. In Vitro Platelet Adhesion Assessment.

All protocols using including the use of whole blood or its components were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee prior to experimentation. Fresh porcine blood was drawn with 3.4% sodium citrate and subsequently centrifuged at 233 × g for 12 min and 3082 × g for 20 min to collect platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-poor plasma (PPP), respectively. The concentration of platelets in both PRP and PPP was determined using a hemocytometer, and both PRP and PPP were then combined to achieve a final concentration of 2 × 108 platelets mL−1. Calcium chloride (2.5 mM) was added to the platelet solution before exposure to samples (1 cm2), which were added to 3 mL of the final platelet solution and rocked at 25 rpm at 37 °C for 1.5 h. After incubation, the samples were removed and infinitely rinsed with PBS to remove any loosely adhered platelets. Samples were transferred to Eppendorf tubes containing an equal volume of a 2 v/v% Triton-PB solution (lysing solution) and for 30 min. Lactate dehydrogenase released from lysed platelets was measured to determine the number of platelets adhered to each sample using a Roche Cytotoxicity kit. Absorbance at 492 nm was measured using a BioTek Cytation5 plate reader. Platelet adhesion compared to untreated control PDMS samples was calculated with a calibration curve according to the following Eq 2, where P = platelets cm−2:

| (2) |

2.9. Hemolysis.

All protocols involving the use of whole blood and its components were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Georgia prior to use. Hemolytic activity of fabricated materials was evaluated based on ISO 10993–4 standards by NAMSA. Fresh porcine whole blood was collected through a blind draw with 3.4% sodium citrate. Collected whole blood was diluted in PBS to reach a hemoglobin concentration of 10 ± 1.0 mg mL−1. Diluted blood was combined with PBS (1 mL diluted blood: 7 mL PBS) in 15 mL conical tubes. Samples (n = 6) were placed in the conical tubes, capped, and kept at 37 °C for 2 h. Sterile DI water and PBS were used as a positive control and blanks, respectively. Tubes were gently inverted every 30 min during incubation. After exposure, samples were removed, and conical tubes were centrifuged at 700 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was collected, added to Drabkin’s reagent (at 1:1 volume ratio), and allowed to stand for 15 min at room temperature. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a plate spectrophotometer plate reader. Blank-corrected hemolysis (%) was calculated based on absorbance (ABS) readings according to the following Eq 3:

| (3) |

2.10. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Measurement.

2.10.1. Cell Culture.

Cytotoxicity of fabricated materials toward mammalian cells was evaluated against human fibroblasts (CRL-2522) according to ISO 10993 standards. All protocols involving mammalian cells were approved by the University of Georgia prior to experimentation. Cells were cultured in a 75 cm2 T-flask with EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep. Flasks were kept at 37 °C in a humified incubator at 5% CO2. Cells were grown to ~80% confluency prior to passaging. Once confluent, cells were trypsinized using 0.18% trypsin and 5 mM EDTA and seeded in a 96-well plate (5000 cells/mL, 100 μL) for 24 h.

2.10.2. Cytotoxicity Assay.

Cytotoxicity was measured using a CCK-8 kit according to ISO 10993 standards and manufacturer’s protocol. Fabricated materials were exposed to cell culture media for 24 h at 37 °C (1 mg of sample per 1 mL of media). The extract was subsequently collected, added (10 μL) to seeded cells (n = 7), and incubated for 24 h. A prepared CCK-8 solution was added (10 μL) to each well and incubated for 3 h. The CCK-8 solution contains WST-8 [2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium monosodium salt], which dehydrogenases present in living cells can reduce to form formazan, detectable at 450 nm wavelength. The absorbance of each well was measured at 450 nm after 3 h exposure to the salt solution. Blank-adjusted cell viability (%) relative to a negative control (media without leachate treatment) was measured according to the following Eq 4:

| (4) |

2.11. Statistical Analysis.

Data reported are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed through performing a standard two-tailed Student’s t test, where p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Material Characterization of SNAP-AmB PDMS.

3.1.1. Fabrication of SNAP-AmB PDMS Polymer.

The primary goals of this project are to (1) demonstrate a proof-of-concept that antifungal agents can also be directly immobilized to medical-grade polymers via covalent bonding as antibiotics are and (2) combine antifungal immobilized-surfaces with NO-releasing technology, rendering modified surfaces antithrombotic, antibacterial, and antifungal.29 This is important to establish as, despite the increased cytotoxicity of antifungal agents when compared to antibacterial agents, there is scarce literature available on surface immobilization of antifungal agents. For this study, AmB was chosen as a model antifungal agent as it is considered an essential medicine by the World Health Organization and is readily available worldwide.30 AmB works by binding to ergosterol (the main sterol of fungal cells) in the cell membrane and has three proposed mechanisms of action: (1) AmB molecules aggregate to form an ion-channel “pore” in the cell membrane, which causes leakage of intracellular components. (2) AmB causes oxidative stress by binding to low-density lipoprotein receptors. (3) AmB molecules adsorb onto the cell membrane which destabilizes the cell membrane by sequestering ergosterol.31 If the density of immobilized AmB is high enough, then the pores proposed in the first mechanism should be capable of forming; however, the latter two proposed mechanisms should be feasible regardless of the density of surface AmB. The mycosamine group on the molecule allows AmB to bind to sterols and cannot bind to sterols without it; therefore, any coupling method cannot use the mycosamine group as an anchoring point. With that in mind, the EDC/NHS reaction was chosen as the coupling method, as it allows for the carboxylic group to be used as the anchoring point (Figure 1).26

In addition to the immobilization of AmB, NO-releasing technology was utilized to create a broad-spectrum antibacterial and antithrombotic surface (in addition to AmB’s antifungal properties). Previous studies have optimized a SNAP solvent swelling protocol, demonstrating that a 25 mg/mL SNAP-THF swelling solution allows for rapid solvent evaporation after swelling, has excellent solvent swelling behavior, optimizes NO release kinetics for short-term application, minimizes the volumes of solution required, and can be used after the polymer extrusion process (which limits depletion of NO reservoir due to the high heat used during extrusion).8,25

The immobilization of AmB and implementation of NO-releasing technology was carried out through a two-step synthesis process. PDMS was swelled in a 25 mg/mL SNAP-THF solution for 24 h and dried under dark ambient conditions overnight to allow excess THF to evaporate. Prior to EDC/NHS coupling of AmB, SNAP PDMS was surface treated with O2 plasma to force −OH groups onto the surface of the PDMS. Thereafter, a layer of primary amines was immobilized onto the surface of the PDMS via chemical vapor deposition of APTMS. Prior to immobilization of AmB, an EDC/NHS reaction was performed for 10 min. In this reaction, the carboxylic acid groups present on AmB are converted to NHS-esters, allowing for more efficient conjugation to primary amines.26 After the formation of the AmB-NHS ester, aminated PDMS samples were placed within the reaction vessel for 2 h and AmB was immobilized onto the PDMS surface. The following sections characterize the physical and biological properties of the fabricated SNAP-AmB PDMS polymer.

3.1.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS).

The surface morphology of the interface of medical devices plays an important role in regulating tissue-device interactions. In order to examine the surface morphology of the fabricated materials, SEM was deployed (Figure 2). The SEM images confirm that the addition of AmB and SNAP does not significantly alter the surface roughness of the PDMS, which supports previous reports that SNAP swelling does not significantly alter surface morphology.22,32

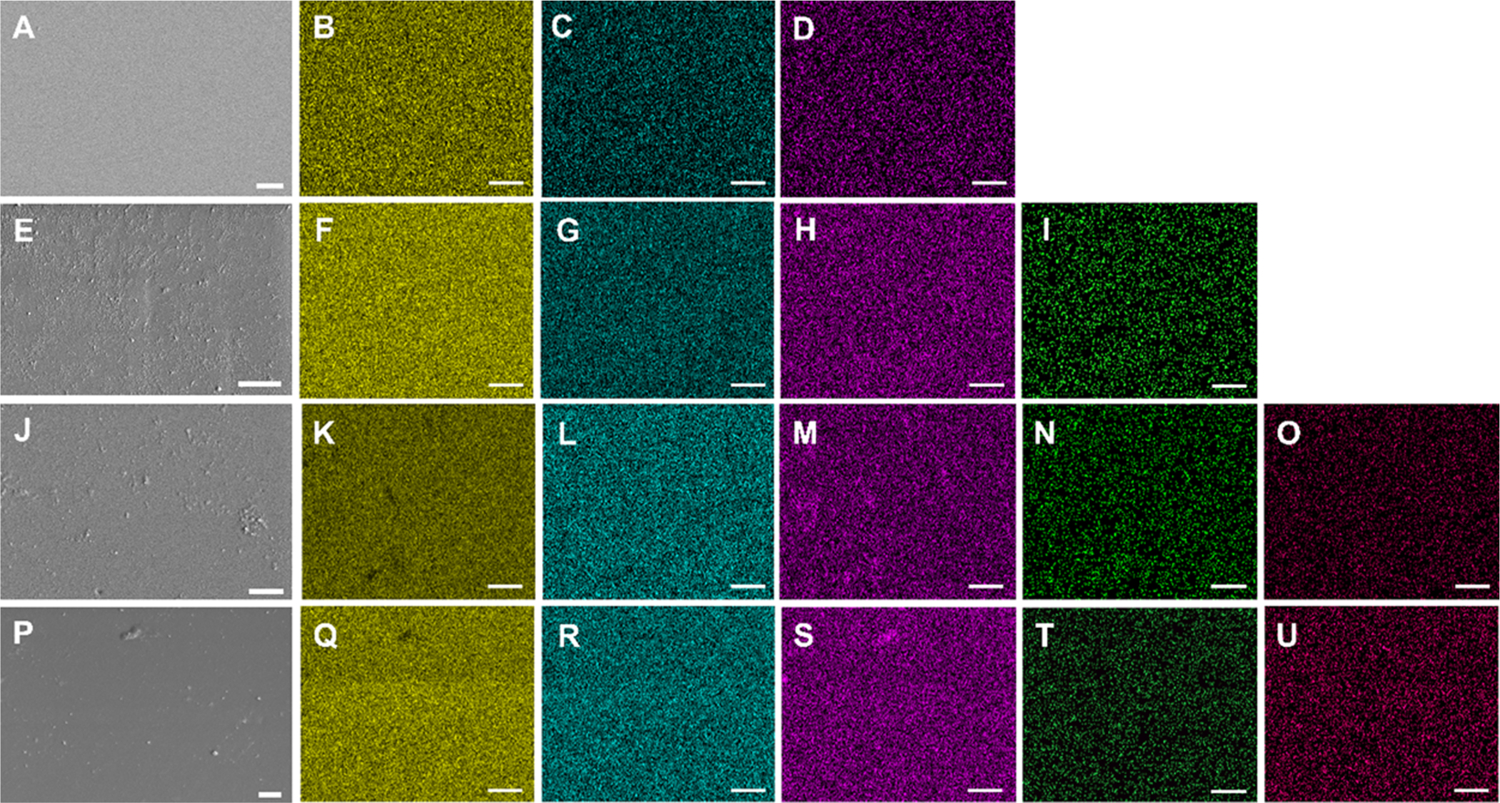

Figure 2.

SEM and EDS mapping of PDMS (A–D), AmB-PDMS (E–I), SNAP-PDMS (J–O), and SNAP-AmB-PDMS (P–U). Silicon (yellow), oxygen (blue), carbon (purple), nitrogen (green), and sulfur (pink) were detected. No significant detection of nitrogen and/or sulfur were found for PDMS and AmB-PDMS samples. White bar, 10 μm.

To confirm that SNAP was successfully impregnated into the PDMS and that AmB was immobilized onto the surface, elemental maps of the materials using EDS were generated (Figure 2). The PDMS base polymer contains silicon (yellow), oxygen (blue), and carbon (purple), which is consistent with the maps generated for the bare PDMS films. In addition to carbon and oxygen, SNAP molecules contain nitrogen and sulfur. Both SNAP and SNAP-AmB films showed well-dispersed nitrogen (green) and sulfur (pink) maps. Similarly, in addition to carbon and oxygen, AmB molecules contain nitrogen. Both AmB and SNAP-AmB films show well-dispersed nitrogen maps, indicating evenly distributed AmB-immobilized molecules on the surface of the PDMS. However, because nitrogen is present in both SNAP and AmB molecules, the detection of sulfur in SNAP-PDMS samples and lack of detection of sulfur in AmB-PDMS samples aids in distinguishing the presence of both SNAP and AmB in the respective samples. To further investigate the effect of SNAP swelling on AmB immobilization, amine quantification and contact angle measurements were examined next.

3.1.3. Amphotericin Surface Quantification.

AmB immobilization was confirmed through UV/vis analysis and the conjugation efficiency was calculated compared to the surface amines quantified via a FITC assay. 3.34 ± 0.51 nmol amines/cm2 (n = 8) were found to be on the surface after treatment with APTMS. This is within the expected range of amino-sylation as it has been previously shown that 3-amino-propyltriethoxysilane chemical vapor deposition resulted in a 0.266 ± 0.017 nmol amines cm−2.32 The higher amount of aminosilane deposition observed in this study can be explicated by: (1) APTMS (the aminosilane used in this study) has less steric hindrance than 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane due to having one less methyl group, which allows for a greater immobilization density. (2) The increased duration of oxygen plasma treatment and chemical vapor deposition in this study compared to what was previously used.

Through analysis of the reaction solution, it was determined that the PDMS surface contained 1.92 ± 0.45 nmol AmB cm−2 (n = 8), which equates to a 57.3 ± 0.13% conjugation efficiency. This degree of AmB conjugation is believed to be enough to prevent biofilm formation on medical devices, as a 2.191 nmol/cm−2 caspofungin (which has a comparable minimum inhibitory concentration to AmB) immobilized surface has been previously shown to reduce C. albicans adherence by ≈89% in a rat implant model.33,34 Additionally, the conjugation efficiency is within the expected range for an EDC/NHS reaction.33,34 However, it has been previously shown that, depending on the molecule, EDC/NHS binding can be optimized at different ratios and durations for denser immobilization of compounds.35 Therefore, while the purpose of this project was to establish proof of concept for direct covalent immobilization of AmB, further work can be done to improve the conjugation efficacy and improve the density of surface-bound AmB.

3.1.4. Contact Angle Measurements.

After confirmation of AmB immobilization, the contact angle of samples throughout the two-step synthesis process was measured to assess the effect on the surface wettability of PDMS. As shown in Table 1, each step in the synthesis process influenced surface wettability. PDMS exhibited a hydrophobic contact angle of 110.5° ± 2.2, which was only slightly affected by the inclusion of SNAP in SNAP PDMS samples (105.6° ± 2.3). This slight reduction is due to the presence of nitrogen and oxygen atoms capable of hydrogen bonding in the SNAP molecule. The addition of the aminated surface through APTMS immobilization significantly affected sample surface wettability and made the surface of both aminated PDMS and aminated SNAP PDMS samples slightly hydrophilic (79.0° ± 2.2 and 80.5° ± 1.9, respectively), which is due to the primary amine on APTMS being capable of forming hydrogen bonds with water. An even greater increase in hydrophilicity was seen with the immobilization of AmB as the contact angle decreased to 59.4° ± 2.7 and 59.5° ± 2.6 on AmB PDMS and SNAP-AmB PDMS, respectively (p < 0.05 compared to PDMS, SNAP, aminated PDMS, and aminated SNAP surfaces). This result is expected as the polyol subunit of AmB (which contains multiple −OH groups) is also capable of hydrogen bonding with water.31

Table 1.

Contact Angle Measurements of Materials throughout the Fabrication Processa

| sample | contact angle |

|---|---|

| PDMS | 110.5° ± 2.2 |

| SNAP | 105.6° ± 2.3 |

| aminated PDMS | 79.0° ± 2.2 |

| aminated SNAP-PDMS | 80.5° ± 1.9 |

| AmB | 59.4° ± 2.7 |

| SNAP-AmB | 59.5° ± 2.6 |

Immobilization of APTMS resulted in an aminated surface capable of hydrogen bonding, which significantly lowered contact angle compared to PDMS and SNAP. SNAP-AmB and AmB surfaces exhibited a further significant increase in hydrophilicity compared to PDMS SNAP, aminated PDMS, and aminated snap surfaces (p <0.05).

3.2. Measurements of SNAP Loading and NO Release Kinetics.

3.2.1. Measurement of SNAP Loading.

To ensure that the immobilization of AmB does not adversely affect the SNAP reservoir, the total SNAP loading of samples was measured before and after AmB immobilization. To measure SNAP loading, freshly made samples were placed within excessive THF, which allowed the SNAP reservoir within the samples to leach into solution. Using a calibration curve, no statistical difference was found between the loading of SNAP before and after AmB immobilization. The 26.42 ± 2.51 and 29.41 ± 4.12 μg/mg of SNAP loaded per mg of PDMS in SNAP and SNAP AmB samples are similar to previously reported SNAP loading via the solvent swelling method (Figure S1).22 Confirmation that the integrity of the SNAP reservoir remains intact means that the AmB immobilization process should not negatively affect the loading of NO.

3.2.2. Nitric Oxide Release Measurements.

NO-releasing materials have previously demonstrated a reduction in the viability of a wide number of microbes and inhibitory effects toward platelet adhesion and activation,35,36 but few materials have demonstrated extended NO-releasing capabilities for long-term (>24 h) applications. Previous studies have routinely demonstrated the catalytic, stable release of NO from S-nitrosothiols (including SNAP) impregnated in polymers by exposure to heat, light irradiation, moisture, or metal ions.7,37,38 Therefore, in this study, PDMS, a polymer commonly used for blood-contacting medical devices including catheters, implants, and pacemaker encapsulants, and AmB-immobilized PDMS was swelled with the NO donor SNAP, and NO release kinetics were measured at 37 °C in PBS to mimic physiological conditions over 10 days (Figure 3). Samples were swelled with a previously optimized concentration of 25 mg/mL SNAP concentration in THF due to (1) its high vapor pressure, allowing for rapid solvent evaporation after swelling and (2) its excellent solvent swelling behavior.8,25 Further, the effect of the immobilization of the antifungal agent AmB on the NO release profile was evaluated.

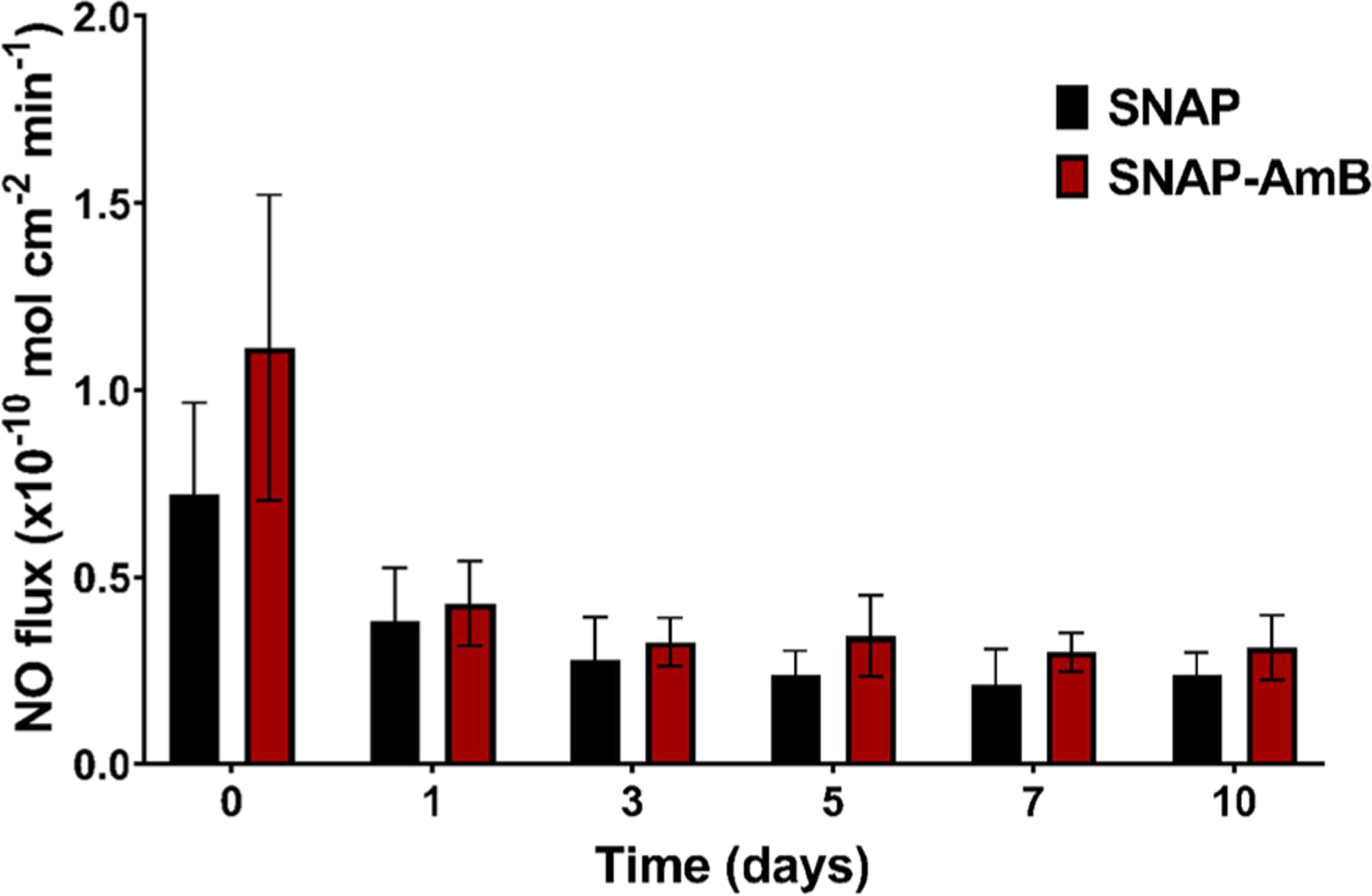

Figure 3.

Average real-time NO release of SNAP and SNAP-AmB PDMS at 37 °C submerged in PBS (n = 6). Data is reported in mean ± SD. Statistical significance (*) was calculated between SNAP and SNAP-AmB surfaces for each time point (p < 0.05).

The overall NO release profile for both the SNAP and SNAP-AmB PDMS samples showed consistent, moderate levels of NO release within a range previously shown to be effective in improving the hemocompatibility and antibacterial activity in short-term and long-term medical device applications.25,39 The initial NO flux for the SNAP and SNAP-AmB PDMS samples (0.72 ± 0.25 × 10−10 mol cm−2 min−1 and 1.11 ± 0.41 × 10−10 mol cm−2 min−1, respectively) were not significantly different (p > 0.05). Both SNAP and SNAP-AmB showed a stabilized, consistent flux for 10 days, displaying a flux of 0.24 ± 0.06 × 10−10 mol cm−2 min−1 and 0.31 ± 0.09 × 10−10 mol cm−2 min−1, respectively, by day 10. A nonsignificant increase in NO flux was observed on day 5 (SNAP-AmB samples) and day 10 (SNAP and SNAP-AmB samples), which is a trend that has been observed in previously reported SNAP-swelled samples.40,41 This nonexponential decay of the NO reservoir can be explained by the crystalline structure formed by SNAP within the silicone after THF evaporation.42 However, further investigation is needed to fully understand this phenomenon. Real-time NO release profiles of samples on day 0 and day 10 can be found in the supporting information section (Figure S2). Similar NO release rates for SNAP-incorporated polymers have been established in literature to be effective for reducing platelet adhesion and increasing antimicrobial properties of medical-grade polymers.8,39 Based off of SNAP loading measurements (Figure S1), only <5% of the NO originally stored in the materials released by day 10.

It should be noted that although the SNAP-AmB samples showed a slightly higher NO flux over the 10 days of measurement compared to SNAP samples, the difference was not significant. The slightly increased NO flux on SNAP-AmB samples is likely attributed to the increased hydrophilicity of the SNAP-AmB surface (confirmed by the contact angle characterization previously discussed), which can improve water uptake and therefore increase the NO release rate. Similar effects due to hydrophilicity have been previously noted in literature.22,23,43 However, because the difference is not significant, this demonstrates that the addition of AmB does not negatively alter the NO release profile over a prolonged period of time. Overall, the NO-release profile is similar to previous SNAP-swelled PDMS reports,8 and future studies including the effects of substrate thickness and its effects on NO release duration can be conducted.

3.3. In Vitro 24 h Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of SNAP-AmB PDMS.

To date, few studies have demonstrated simultaneous broad antimicrobial efficacy against clinically relevant bacterial and fungal pathogens. NO-releasing materials have demonstrated tremendous promise for reducing the viability of numerous bacterial strains with minimal resistance,44,45 but have had little success against fungal pathogens which requires much higher, potentially cytotoxic concentrations of NO to be effective.10–12 Therefore, with an aim to increase the antimicrobial activity of polymers used for medical devices, the common antifungal agent AmB was immobilized onto the surface of SNAP-swelled PDMS. To assess the antimicrobial efficacy of the synthesized materials, a series of 24 h in vitro antimicrobial assays was performed to assess the viability of adhered bacteria and fungi commonly associated with hospital-acquired infections after exposure to the materials. Isolated strains of S. aureus (Gram-positive bacteria), E. coli (Gram-negative bacteria), and C. albicans (opportunistic fungi) were exposed to each sample type for 24 h at 37 °C at 150 rpm. Figure 4 summarizes the effects of the different surface modifications on the viability of the adhered pathogens, and Figure S3 shows representative pathogen spread plates for each sample type.

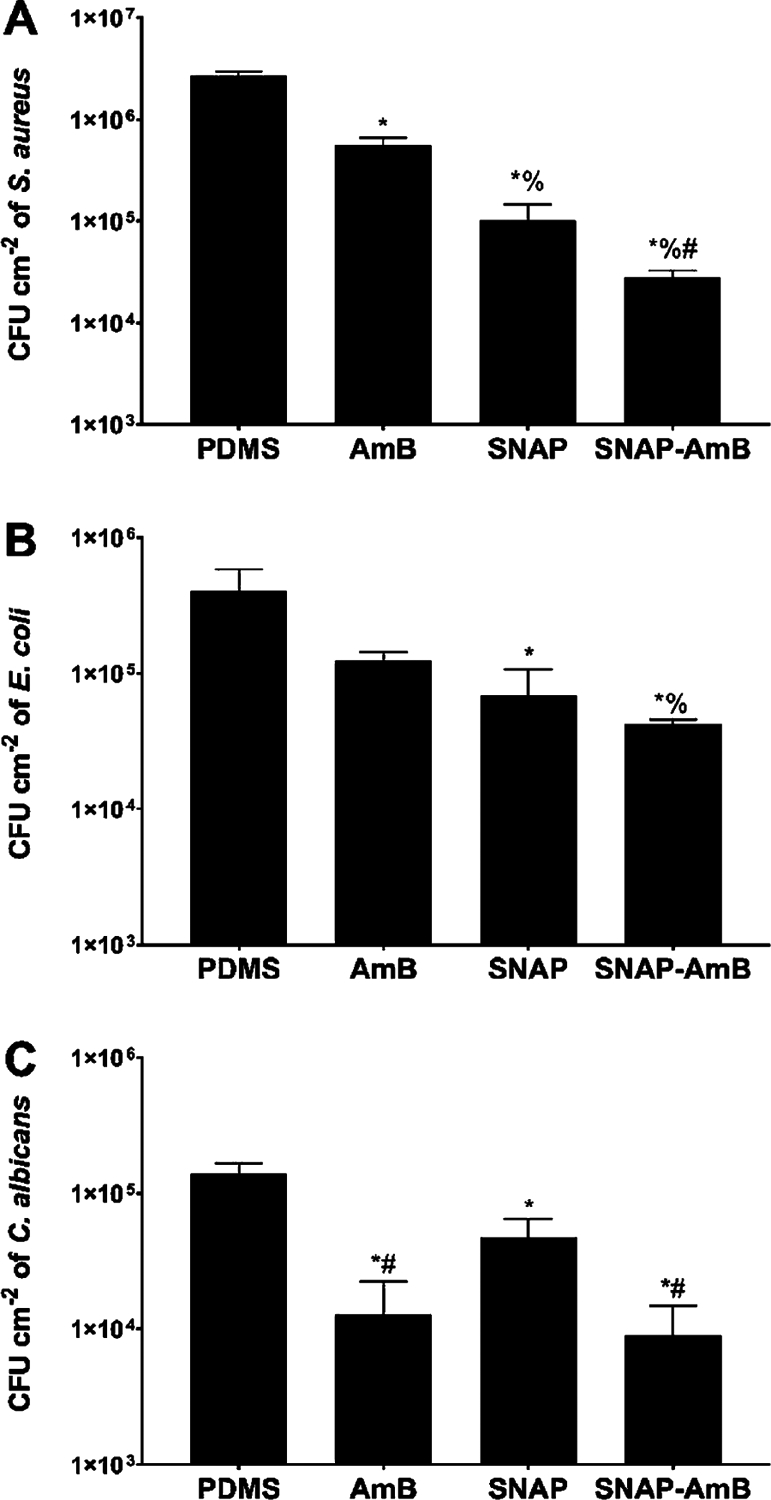

Figure 4.

Adhered bacterial and fungal viability after 24 h exposure of materials to S. aureus (A), E. coli (B), and C. albicans(C) quantified in CFU/cm2. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) is indicated by *, %, and # compared to PDMS, AmB, and SNAP samples, respectively. Measurements are reported in mean ± SD.

NO-releasing surfaces have been shown previously to reduce bacterial viability through several different mechanisms including DNA cleavage, nitrosative and oxidative stress, and peroxynitrite or superoxide formation.37 As expected, SNAP surfaces significantly reduced the viability of adhered S. aureus and E. coli (Figure 4A,B) compared to PDMS control surfaces (SNAP vs S. aureus − 96.2 ± 1.6%; SNAP vs E. coli − 83.2 ± 9.3%; SNAP-AmB vs S. aureus − 99.0 ± 0.2%; SNAP-AmB vs E. coli − 89.7 ± 1.0%; p < 0.05). The presence of AmB did not interfere with the antibacterial nature of NO-releasing surfaces. In fact, the presence of AmB marginally reduced the number of viable adhered S. aureus and E. coli compared to PDMS controls by 79.4 ± 3.8% (p < 0.05) and 69.5 ± 4.7% (p > 0.05), respectively. As demonstrated by the contact angle measurements earlier, AmB immobilization resulted in increased hydrophilicity of PDMS. Hydrophilic surfaces with similar contact angles have exhibited similar reductions in adhered bacterial pathogens.46,47 By creating a hydration layer, a hydrophilic surface has an increased thermodynamic requirement for foulants to bind onto, which results in a bioinert antifouling mechanism.48 Overall, SNAP-AmB surfaces best reduced the number of viable S. aureus (99.0 ± 0.2%) and E. coli (89.7 ± 1.0%) on the surfaces (p < 0.05). These results are consistent with other NO-releasing materials, which have similarly reduced the viability of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial pathogens by >80%.7,37–39 The resulting antifungal-immobilized NO-releasing surface modification can be applied to limitless medical-grade polymers, demonstrating the potential of the surface’s dual-antimicrobial functionality for biomedical applications.

In addition to antibacterial effects, the SNAP-AmB surfaces significantly reduced the viability of adhered C. albicans (Figure 4C) compared to control PDMS surfaces (AmB: 90.8 ± 7.0%; SNAP-AmB: 93.5 ± 4.2%; p < 0.05). AmB binds to ergosterol present in the cell membrane of fungi, which serves a similar role to that of cholesterol in mammalian cells, causing membrane destabilization.49 After binding, the leakage of monovalent ions as a result of the formation of ion channels results in membrane depolarization.50 The presence of AmB can also result in oxidative damage and mitochondrial disruption, although the exact mechanism of this is still unknown.49 Although only SNAP-swelled samples were able to reduce the viability of adhered C. albicans, the difference in reduction was more modest (65.8 ± 12.5%). A previous study by Privett et al. showed that NO-releasing xerogel surfaces had comparable antifungal effects against C. albicans, also demonstrating that NO-releasing surfaces have lower antimicrobial efficacy against C. albicans relative to bacteria.51 No statistical difference was found between the antifungal efficacy of AmB-PDMS and SNAP-AmB-PDMS samples (p > 0.05). Therefore, due to the reduced efficacy of NO against C. albicans, a combination of NO-releasing surfaces with antifungal strategies to reduce the risk of broad-spectrum infections is warranted.

3.4. In Vitro Analysis of Antiplatelet Properties of SNAP-AmB PDMS.

Currently, the systemic administration of anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapies are the clinical standards in preventing medical device-induced clot formation. However, regardless of the therapeutic agent used, the most common adverse side effect from systemic anticoagulation is acute hemorrhaging including gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding.52 Due to these complications, the systemic administration of anticoagulants leads the United States in clinical drug-related deaths.53,54 Therefore, a surface modification that prevents platelet adhesion and activation is of high demand.

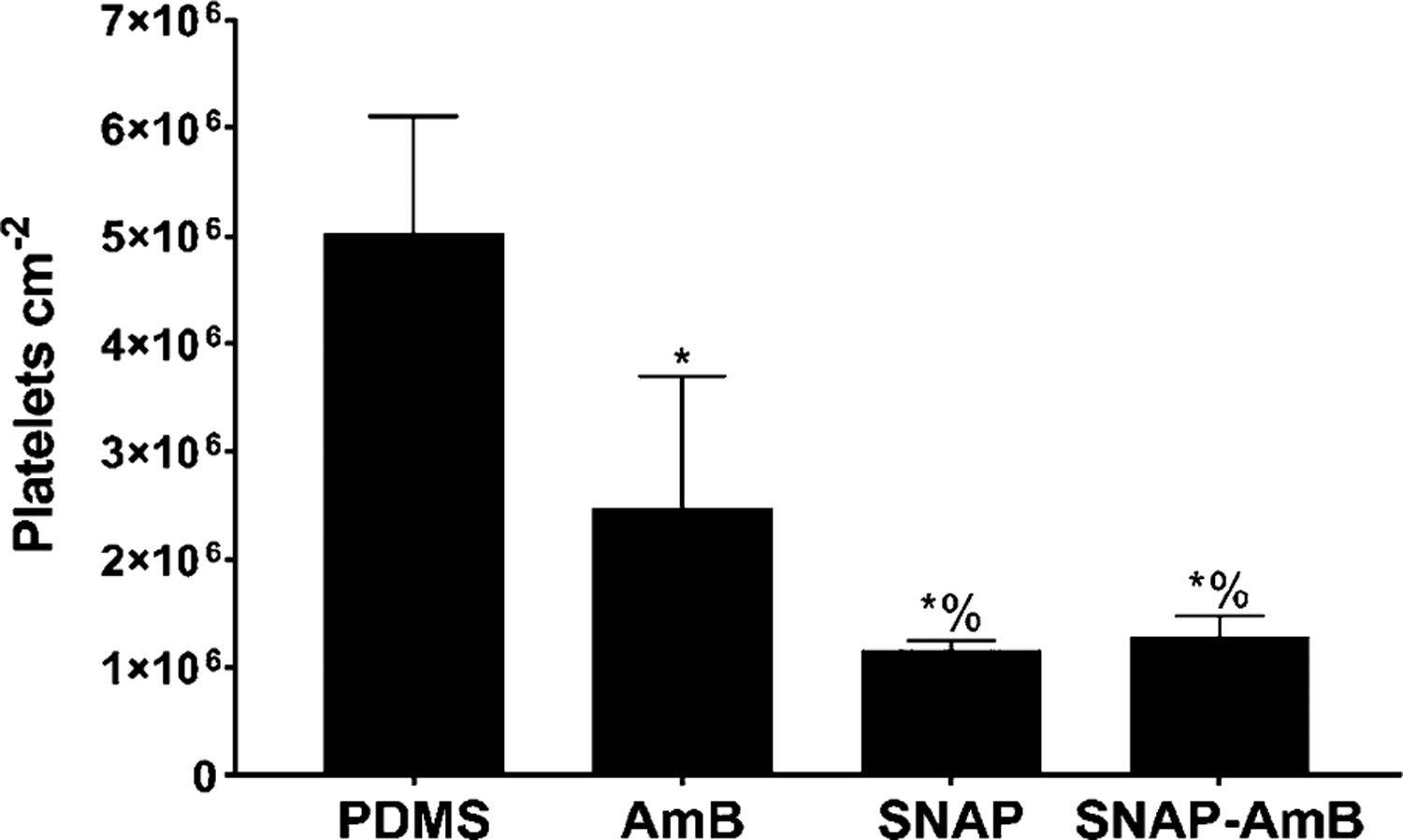

In this study, the antiplatelet activity of the fabricated materials was measured using an LDH assay after in vitro exposure to porcine plasma (2 × 108 platelets/mL) for 1.5 h (Figure 5). Interestingly, AmB PDMS samples resulted in a 50.9 ± 24.5% reduction of platelets compared to PDMS, which was statistically significant compared to control PDMS surfaces (p < 0.05). This reduction can again be attributed to the surface hydrophilicity due to AmB immobilization. Increased hydrophilicity has been previously shown to have antifouling behavior due to the increased affinity for water molecules, which can reduce platelet adhesion.23 Due to NO’s antiplatelet effect, both SNAP and SNAP-AmB samples exhibited a significantly higher reduction of adhered platelets with a respective reduction of 76.9 ± 1.8 and 74.6 ± 3.9% (p < 0.05). This reduction can be attributed to the NO flux exhibited by the samples, which is similar to that of the normal endothelium of blood vessels responsible for modulating platelet activity.55,56 However, no statistical significance was found between SNAP and SNAP-AmB samples.

Figure 5.

In vitro platelet adhesion normalized to surface area. Statistical significance (p < 0.05) is indicated by * and % compared to PDMS and AmB, respectively. Measurements are reported in mean ± SD.

3.5. Hemolytic Activity of SNAP-AmB.

Erythrocytes can be lysed via the exposure of foreign materials due to contact, toxins, metal ions, leachates, and surface charge, leading to decreased oxygen transport, toxicity, and altered kidney function.57,58 Hemolysis is an important measure in assessing hemocompatibility as hemolysis of RBCs releases hemoglobin into the plasma which causes a pro-thrombotic response.59,60 To measure the hemolytic activity of the fabricated materials, samples (n = 6) were incubated directly in vitro with whole porcine blood for 2 h at 37 °C according to ISO 10993–4 protocol (Table 2). All fabricated materials were found to be nonhemolytic (hemolytic index <2%), and the positive control (sterile DI water) had a hemolytic index ~100%. According to ASTM scoring standards, materials are considered nonhemolytic when the hemolytic index is below 2%.61 Therefore, we consider all of the tested samples to be considered nonhemolytic, exhibiting no statistical difference between sample types (p > 0.05). Thus, all fabricated materials were found to be safe toward erythrocytes according to a 2 h in vitro whole blood study.

Table 2.

Hemolytic Activity of PDMS, AmB, SNAP, and SNAP-AmB Materialsa

| sample type | hemolysis (%) |

|---|---|

| PDMS | 0.49 ± 0.54 |

| AmB | 0.65 ± 1.18 |

| SNAP | 0.16 ± 0.40 |

| SNAP-AmB | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| sterile DI water | 96.06 ± 4.31 |

All materials were found to be nonhemolytic (<2%). Sterile DI water was used as a positive control.

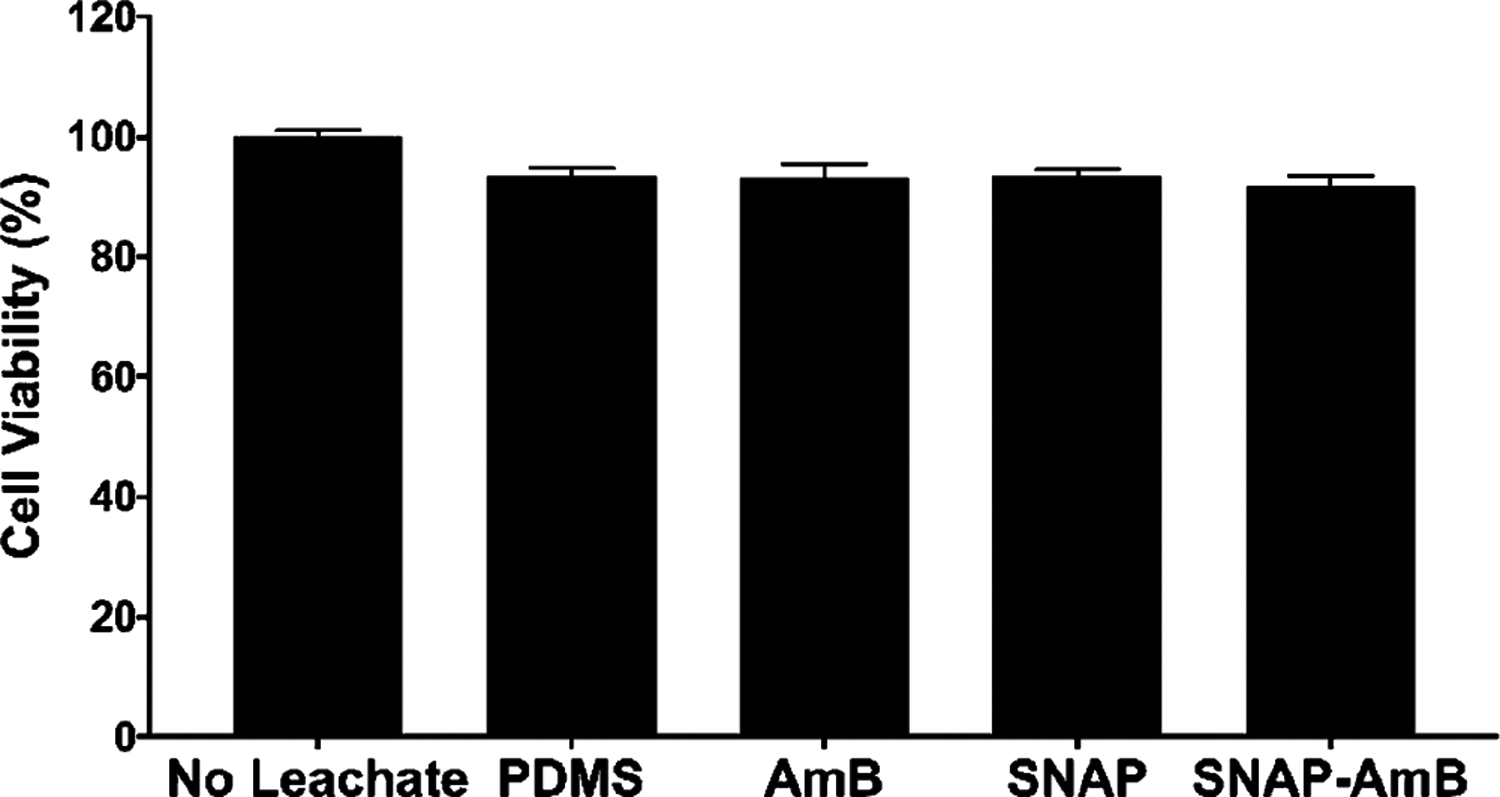

3.6. In Vitro Cytotoxicity of SNAP-AmB toward Human Fibroblasts.

Investigating cytotoxicity is a necessary preliminary biological evaluation in determining the toxicity of different materials toward host cells. This is especially important to measure given AmB’s severe side effects and potential toxicity toward mammalian cells.19–21 This cytotoxicity is highly related to the concentration of AmB and is caused by binding to cholesterol in mammalian cells (which is similar in structure to ergosterol). In this study, the toxicity of PDMS, AmB, SNAP, and SNAP-AmB materials toward human fibroblasts was measured using in vitro cytotoxicity testing in accordance with ISO 10993 standards. Leachates from the materials were collected over 24 h and were exposed to human fibroblast cells for an additional 24 h to allow for a cytotoxic response (if any). With respect to control human fibroblasts, no cytotoxicity (> 90% human fibroblast viability) was measured from any of the materials (PDMS: 93.4 ± 1.4%; AmB: 93.2 ± 2.2%; SNAP: 93.4 ± 1.1%; and SNAP-AmB: 91.8 ± 1.7%) (Figure 6). No significant difference was found between any of the sample types (p > 0.05). Previous studies have reported similar noncytotoxic behavior from other SNAP-based materials.37,38,40,62 While administration of AmB at high enough concentrations can potentially lead to local and/or systemic toxicity,63 the concentration of AmB present in the leachates in this study did not adversely affect fibroblast viability. When assessed over a 7-day period in physiological conditions, no detectable amounts of AmB could be quantified using UV–vis. Therefore, it can be concluded that the EDC/NHS immobilization method allows for stable coupling of AmB with little to no leaching. This conclusion would be in line with previous biomacromolecule immobilization using EDC/NHS which showed negligible leaching of immobilized compounds.64,65 Given the promising in vitro cytotoxicity results from this study, further in vivo testing can be performed to dictate the safety and efficacy of the fabricated materials.

Figure 6.

In vitro cytotoxicity measurements against human fibroblasts. Measurements are reported in mean ± SD.

4. CONCLUSIONS

The two primary objectives for this study were to (1) for the first time fabricate and evaluate a novel Amphotericin B-immobilized polymeric surface and (2) combine the antifungal-immobilized surface with NO-releasing technology to render the surface antibacterial, antifungal, and antithrombotic. The findings from this study provide a promising platform for combating broad-spectrum colonization and improving the hemocompatibility of polymer surfaces. In this work, NO-releasing Amphotericin B-immobilized PDMS was developed using a two-step solvent swelling and EDC/NHS coupling method. The synthesized material demonstrated a consistent NO flux over 10 days. Surface functionalization with AmB reduced the contact angle from 110.5° ± 2.2° (untreated PDMS) to ~59°. Further, amine quantification revealed that the EDC/NHS coupling method was able to immobilize 361.70 ± 12.72 μg/cm−2 AmB onto the PDMS surface. The resulting surface modifications significantly decreased the viability of adhered S. aureus (99.0 ± 0.2%), E. coli (89.7 ± 1.0%), and C. albicans (93.5 ± 4.2%), presenting an all-encompassing antimicrobial surface strategy for unilaterally combatting broad-spectrum infections as opposed to current standards of care. In addition, the NO-releasing surfaces improved antithrombotic activity (>75% reduction in platelet adhesion) compared to untreated surfaces. None of the surface modifications developed in this study resulted in cytotoxic effects toward human fibroblasts (>90% cell viability) or any hemolytic activity toward erythrocytes (<2% hemolysis). This study presents a proof of concept for a singular-platform solution that simultaneously combats broad-spectrum infection and prevents surface-induced thrombosis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, USA grant R01HL134899.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsami.1c01330.

Loading of the NO donor SNAP, representative NO release profiles, representative images of pathogen spread plates (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsami.1c01330

Author Contributions

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: “Dr. Hitesh Handa is the founder of inNOveta Biomedical LLC. inNOveta Biomedical LLC is exploring possibilities of using nitric oxide releasing materials for medical applications.”

Contributor Information

Ryan Devine, School of Chemical, Materials and Biomedical Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602, United States.

Megan Douglass, School of Chemical, Materials and Biomedical Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602, United States.

Morgan Ashcraft, School of Chemical, Materials and Biomedical Engineering, College of Engineering and Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences Department, College of Pharmacy, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602, United States.

Nicole Tayag, School of Chemical, Materials and Biomedical Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602, United States.

Hitesh Handa, School of Chemical, Materials and Biomedical Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Kojic EM; Darouiche RO Candida Infections of Medical Devices. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2004, 17, 255–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Nguyen NT; Grelling N; Wetteland CL; Rosario R; Liu H Antimicrobial Activities and Mechanisms of Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles (nMgO) against Pathogenic Bacteria, Yeasts, and Biofilms. Sci. Rep 2018, 8, 16260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Römling U; Kjelleberg S; Normark S; Nyman L; Uhlin BE; Åkerlund B Microbial Biofilm Formation: A Need to Act. J. Intern. Med 2014, 276, 98–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Brisbois EJ, Handa Hitesh, Meyerhoff ME Recent Advances in Hemocompatible Polymers for Biomedical Applications. In Advanced Polymers in Medicine; Springer, Ed.; 2015, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-12478-0_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Cronin RE; Reilly RF Unfractionated Heparin for Hemodialysis: Still the Best Option. Semin. Dial 2010, 23, 510–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Suen K; Westh RN; Churilov L; Hardidge AJ Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin and the Relative Risk of Surgical Site Bleeding Complications: Results of a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials of Venous Thromboprophylaxis in Patients After Total Joint Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 2017, 32, 2911–2919.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Douglass ME; Goudie MJ; Pant J; Singha P; Hopkins S; Devine R; Schmiedt CW; Handa H Catalyzed Nitric Oxide Release via Cu Nanoparticles Leads to an Increase in Antimicrobial Effects and Hemocompatibility for Short-Term Extracorporeal Circulation. ACS Appl. Bio Mater 2019, 2, 2539–2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Goudie MJ; Pant J; Handa H Liquid-Infused Nitric Oxide-Releasing (LINORel) Silicone for Decreased Fouling, Thrombosis, and Infection of Medical Devices. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 13623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Hopkins SP; Pant J; Goudie MJ; Schmiedt C; Handa H Achieving Long-Term Biocompatible Silicone via Covalently Immobilized S-Nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) That Exhibits 4 Months of Sustained Nitric Oxide Release. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 27316–27325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ghaffari A; Miller CC; McMullin B; Ghahary A Potential Application of Gaseous Nitric Oxide as a Topical Antimicrobial Agent. Nitric Oxide 2006, 14, 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Macherla C; Sanchez DA; Ahmadi MS; Vellozzi EM; Friedman AJ; Nosanchuk JD; Martinez LR Nitric Oxide Releasing Nanoparticles for Treatment of Candida albicans Burn Infections. Front. Microbiol 2012, 3, 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Stasko N; McHale K; Hollenbach SJ; Martin M; Doxey R Nitric Oxide-Releasing Macromolecule Exhibits Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Activity and Utility as a Topical Treatment for Superficial Fungal Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2018, 62 (), DOI: DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01026-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Li C-Q; Pang B; Kiziltepe T; Trudel LJ; Engelward BP; Dedon PC; Wogan GN Threshold Effects of Nitric Oxide-Induced Toxicity and Cellular Responses in Wild-Type and p53-Null Human Lymphoblastoid Cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2006, 19, 399–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Carpenter AW; Schoenfisch MH Nitric Oxide Release: Part II. Therapeutic Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev 2012, 41, 3742–3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Coad BR; Griesser HJ; Peleg AY; Traven A Anti-Infective Surface Coatings: Design and Therapeutic Promise Against Device-Associated Infections. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, No. e1005598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Jabra-Rizk MA; Kong EF; Tsui C; Nguyen MH; Clancy CJ; Fidel PL; Noverr M Candida albicans Pathogenesis: Fitting Within the Host-Microbe Damage Response Framework. Infect. Immun 2016, 84, 2724–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Roscetto E; Contursi P; Vollaro A; Fusco S; Notomista E; Catania MR Antifungal and Anti-Biofilm Activity of the First Cryptic Antimicrobial Peptide From an Archaeal Protein Against Candida Spp. Clinical Isolates. Sci. Rep 2018, 8, 17570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Vargas-Blanco D; Lynn A; Rosch J; Noreldin R; Salerni A; Lambert C; Rao RP A Pre-Therapeutic Coating for Medical Devices That Prevents the Attachment of Candida albicans. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob 2017, 16, DOI: DOI: 10.1186/s12941-017-0215-z,. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Boogaerts M; Winston DJ; Bow EJ; Garber G; Reboli AC; Schwarer AP; Novitzky N; Boehme A; Chwetzoff E; De Beule K; Itraconazole Neutropenia Study G Intravenous and Oral Itraconazole Versus Intravenous Amphotericin B Deoxycholate as Empirical Antifungal Therapy for Persistent Fever in Neutropenic Patients With Cancer Who Are Receiving Broad-Spectrum Antibacterial Therapy. a Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann. Intern. Med 2001, 135, 412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Laniado-Laborín R; Cabrales-Vargas MN Amphotericin B: Side Effects and Toxicity. Rev. Iberoam. Micol 2009, 26, 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Seneviratne CJ; Rosa EAR Editorial: Antifungal Drug Discovery: New Theories and New Therapies. Front. Microbiol 2016, 7, 728–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Devine R; Goudie MJ; Singha P; Schmiedt C; Douglass M; Brisbois EJ; Handa H Mimicking the Endothelium: Dual Action Heparinized Nitric Oxide Releasing Surface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 20158–20171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Singha P; Pant J; Goudie MJ; Workman CD; Handa H Enhanced Antibacterial Efficacy of Nitric Oxide Releasing Thermo-plastic Polyurethanes With Antifouling Hydrophilic Topcoats. Biomater. Sci 2017, 5, 1246–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Chipinda I; Simoyi RH Formation and Stability of a Nitric Oxide Donor: S-Nitroso-N-Acetylpenicillamine. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 5052–5061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Brisbois EJ; Major TC; Goudie MJ; Bartlett RH; Meyerhoff ME; Handa H Improved Emocompatibility of Silicone Rubber Extracorporeal Tubing via Solvent Swelling-Impregnation of S-Nitroso-N-Acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) and Evaluation in Rabbit Thrombogenicity Model. Acta Biomater. 2016, 37, 111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Fischer MJ Amine Coupling Through Edc/NHS: A Practical Approach. In Surface plasmon resonance; Springer: 2010; 55–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Tan TR; Hoi KM; Zhang P; Ng SK Characterization of a Polyethylene Glycol-Amphotericin B Conjugate Loaded with Free AMB for Improved Antifungal Efficacy. PLoS One 2016, 11, No. e0152112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Torres N; Oh S; Appleford M; Dean DD; Jorgensen JH; Ong JL; Agrawal CM; Mani G Stability of Antibacterial Self-Assembled Monolayers on Hydroxyapatite. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 3242–3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Kallenberg AI; van Rantwijk F; Sheldon RA Immobilization of Penicillin G Acylase: The Key to Optimum Performance. Adv. Synth. Catal 2005, 347, 905–926. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Model List of Essential Medicines; World Health Organization: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Kamiński DM Recent Progress in the Study of the Interactions of Amphotericin B With Cholesterol and Ergosterol in Lipid Environments. Eur. Biophys. J 2014, 43, 453–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Brisbois EJ; Major TC; Goudie MJ; Bartlett RH; Meyerhoff ME; Handa H Improved Hemocompatibility of Silicone Rubber Extracorporeal Tubing via Solvent Swelling-Impregnation of S-Nitroso-N-Acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) and Evaluation in Rabbit Thrombogenicity Model. Acta Biomater. 2016, 37, 111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kucharíkoáv S; Gerits E; De Brucker K; Braem A; Ceh K; Majdič G;Španič T; Pogorevc E; Verstraeten N; Tournu H; Delattin N; Impellizzeri F; Erdtmann M; Krona A; Lövenklev M; Knezevic M; Fröhlich M; Vleugels J; Fauvart M; de Silva WJ; Vandamme K; Garcia-Forgas J; Cammue BPA; Michiels J; Van Dijck P; Thevissen K Covalent Immobilization of Antimicrobial Agents on Titanium Prevents Staphylococcus Aureus and Candida Albicans Colonization and Biofilm Formation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2016, 71, 936–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Lemos JA; Costa CR; de Araújo CR; Souza LKHE; Silva M. d. R. R. Susceptibility Testing of Candida Albicans Isolated From Oropharyngeal Mucosa of HIV(+) Patients to Fluconazole, Amphotericin B and Caspofungin. Killing Kinetics of Caspofungin and Amphotericin B Against Fluconazole Resistant and Susceptible Isolates. Braz. J. Microbiol 2009, 40, 163–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Gierke GE; Nielsen M; Frost MC S-Nitroso-N-Acetyl-D-Penicillamine Covalently Linked to Polydimethylsiloxane (SNAP-PDMS) for Use as a Controlled Photoinitiated Nitric Oxide Release Polymer. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater 2011, 12, No. 055007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Pant J; Gao J; Goudie MJ; Hopkins SP; Locklin J; Handa H A Multi-Defense Strategy: Enhancing Bactericidal Activity of a Medical Grade Polymer With a Nitric Oxide Donor and Surface-Immobilized Quaternary Ammonium Compound. Acta Biomater. 2017, 58, 421–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Mondal A; Douglass M; Hopkins SP; Singha P; Tran M; Handa H; Brisbois EJ Multifunctional S-Nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine-Incorporated Medical-Grade Polymer with Selenium Interface for Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 34652–34662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Pant J; Goudie MJ; Hopkins SP; Brisbois EJ; Handa H Tunable Nitric Oxide Release from S-Nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine via Catalytic Copper Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 15254–15264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Singha P; Goudie MJ; Liu Q; Hopkins S; Brown N; Schmiedt CW; Locklin J; Handa H Multipronged Approach to Combat Catheter-Associated Infections and Thrombosis by Combining Nitric Oxide and a Polyzwitterion: a 7 Day In Vivo Study in a Rabbit Model. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 9070–9079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Colletta A; Wu J; Wo Y; Kappler M; Chen H; Xi C; Meyerhoff ME S-Nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) Impregnated Silicone Foley Catheters: A Potential Biomaterial/Device To Prevent Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2015, 1, 416–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Feit CG; Chug MK; Brisbois EJ Development of S-Nitroso-N-Acetylpenicillamine Impregnated Medical Grade Polyvinyl Chloride for Antimicrobial Medical Device Interfaces. ACS Appl. Bio Mater 2019, 2, 4335–4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Wo Y; Li Z; Colletta A; Wu J; Xi C; Matzger AJ; Brisbois EJ; Bartlett RH; Meyerhoff ME Study of Crystal Formation and Nitric Oxide (NO) Release Mechanism From S-Nitroso-N-Acetylpenicillamine (SNAP)-Doped Carbosil Polymer Composites for Potential Antimicrobial Applications. Composites, Part B 2017, 121, 23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Riccio DA; Dobmeier KP; Hetrick EM; Privett BJ; Paul HS; Schoenfisch MH Nitric Oxide-Releasing S-Nitrosothiol-Modified Xerogels. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 4494–4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Sadrearhami Z; Nguyen T-K; Namivandi-Zangeneh R; Jung K; Wong EHH; Boyer C Recent Advances in Nitric Oxide Delivery for Antimicrobial Applications Using Polymer-Based Systems. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 2945–2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Schairer DO; Chouake JS; Nosanchuk JD; Friedman AJ The Potential of Nitric Oxide Releasing Therapies as Antimicrobial Agents. Virulence 2012, 3, 271–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Mohamad AJ; Zhu X; Liu X; Pfleging W; Torge M In Effect of Surface Topography on Hydrophobicity and Bacterial Adhesion of Polystyrene, 2013; IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Yuan Y; Hays MP; Hardwidge PR; Kim J Surface Characteristics Influencing Bacterial Adhesion to Polymeric Substrates. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 14254–14261. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Chen S; Li L; Zhao C; Zheng J Surface Hydration: Principles and Applications Toward Low-Fouling/Nonfouling Biomaterials. Polymer 2010, 51, 5283–5293. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Mesa-Arango AC; Scorzoni L; Zaragoza O It Only Takes One to Do Many Jobs: Amphotericin B as Antifungal and Immunomodulatory Drug. Front. Microbiol 2012, 3 (), DOI: DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Noor A; Preuss CV Antifungal Membrane Function Inhibitors (Amphotericin B). In StatPearls; Treasure Island, FL, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Privett BJ; Nutz ST; Schoenfisch MH Efficacy of Surface-Generated Nitric Oxide Against Candida albicans Adhesion and Biofilm Formation. Biofouling 2010, 26, 973–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Harter K; Levine M; Henderson SO Anticoagulation Drug Therapy: A Review. West. J. Emerg. Med 2015, 16, 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Shepherd G; Mohorn P; Yacoub K; May DW Adverse Drug Reaction Deaths Reported in United States Vital Statistics, 1999–2006. Ann. Pharmacother 2012, 46, 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Dhakal B; Kreuziger LB; Rein L; Kleman A; Fraser R; Aster RH; Hari P; Padmanabhan A Disease Burden, Complication Rates, and Health-Care Costs of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia in the USA: A Population-Based Study. Lancet Haematol. 2018, 5, e220–e231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Vaughn MW; Kuo L; Liao JC Estimation of Nitric Oxide Production and Reactionrates in Tissue by Use of a Mathematical Model. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 1998, 274, H2163–H2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Emerson M; Momi S; Paul W; Francesco PA; Page C; Gresele P Endogenous Nitric Oxide Acts as a Natural Antithrombotic Agent In Vivo by Inhibiting Platelet Aggregation in the Pulmonary Vasculature. Thromb. Haemost 1999, 81, 961–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Weber M; Steinle H; Golombek S; Hann L; Schlensak C; Wendel HP; Avci-Adali M Blood-Contacting Biomaterials: In Vitro Evaluation of the Hemocompatibility. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol 2018, 6, 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Brisbois EJ; Major TC; Goudie MJ; Meyerhoff ME; Bartlett RH; Handa H A Attenuation of Thrombosis and Bacterial Infection Using Dual Function Nitric Oxide Releasing Central Venous Catheters in a 9 Day Rabbit Model. Acta Biomater. 2016, 44, 304–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Da Q; Teruya M; Guchhait P; Teruya J; Olson JS; Cruz MA Free Hemoglobin Increases Von Willebrand Factor-Mediated Platelet Adhesion in Vitro: Implications for Circulatory Devices. Blood 2015, 126, 2338–2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Helms CC; Marvel M; Zhao W; Stahle M; Vest R; Kato GJ; Lee JS; Christ G; Gladwin MT; Hantgan RR; Kim-Shapiro DB Mechanisms of Hemolysis-Associated Platelet Activation. J. Thromb. Haemost 2013, 11, 2148–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).ASTM. F756–17 Standard Practice for Assessment of Hemolytic Properties of Materials. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (62).Pant J; Goudie MJ; Chaji SM; Johnson BW; Handa H Nitric Oxide Releasing Vascular Catheters for Eradicating Bacterial Infection. J. Biomed. Mater Res. B Appl. Biomater 2018, 106, 2849–2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Harmsen S; McLaren AC; Pauken C; McLemore R Amphotericin B Is Cytotoxic at Locally Delivered Concentrations. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 2011, 469, 3016–3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Wu B; Gerlitz B; Grinnell BW; Meyerhoff ME Polymeric Coatings That Mimic the Endothelium: Combining Nitric Oxide Release with Surface-Bound Active Thrombomodulin and Heparin. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 4047–4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Lee J; Yoo JJ; Atala A; Lee SJ Controlled Heparin Conjugation on Electrospun Poly(ε-Caprolactone)/Gelatin Fibers for Morphology-Dependent Protein Delivery and Enhanced Cellular Affinity. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 2549–2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.