It is 2021. The imperative to move health care services outside of hospitals is evident. Before the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, Canadian media had switched its tune from “shorter surgical times” to demanding the end of “hallway medicine.” During the COVID-19 pandemic, the message is to keep patients safe at home and out of high-risk settings. With a greater focus on care received outside of the hospital, there is growing emphasis on the role played by community-based care sectors and, in particular, family medicine. However, confusion remains around this sector, including terminology and the role it plays in keeping patients healthy in their communities. Clarity around terminology is essential to guide health system reform both in Canada and globally, and to ensure health system actors are using a single vocabulary. In this article, we clarify the distinctions between primary health care (PHC), primary care, and family medicine and highlight how family medicine is an adaptive and evolving field that meets the needs of patients and communities. Primary care is an essential component of a well-functioning PHC system. Family medicine is a subset of primary care delivered by family physicians.

In 2019 we celebrated the 50th anniversary of Certification in Family Medicine. Despite being a field with a unique certification for more than 50 years, the distinctions between family medicine, primary care, and PHC are often blurred. The confusion in the language is evident given the recent statement released by the College of Family Physicians of Canada to protect family medicine terminology, given a trend where “family practice” and “family medicine” are being used outside of the field.1 Misunderstanding in terminology not only signals a lack of understanding of the different skill sets and roles of providers, but risks affecting how health care is organized and delivered.

Family medicine is a unique field focused on delivering “high-quality, evidence-based care from family physicians trained to meet the health care needs of their patients and communities.”1 It is critical to the delivery of primary care and PHC in Canada and continues to evolve to meet the needs of our population. Globally, countries are introducing family medicine as a way of strengthening PHC. As this happens, researchers, educators, policy makers, and the family medicine community need to have a clear understanding of the distinctions and interrelationships between these 3 sectors.

Primary health care

The concept of PHC has been redefined repeatedly since the concept first emerged in 1920 in the Dawson report, where PHC was identified as the first level of care, “equipped for services of curative and preventive medicine.”2 In 1978, the World Health Organization (WHO) formalized its commitment to PHC globally. It defined PHC as “essential health care made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community by means acceptable to them through their full participation.”3 Essential health care was meant to include health promotion, disease prevention, and curative, rehabilitative, and supportive care. The WHO further identified PHC as the key to achieving “health for all” through the Declaration of Alma-Ata.4 While the Declaration of Alma-Ata led to an agreement on the importance of PHC, it did not define how to operationalize this commitment. In 2018, 40 years after the Declaration of Alma-Ata, global partners reconvened at the Global Conference on Primary Health Care not only to renew their pledge to PHC through the Declaration of Astana but also to agree on a single operational definition of PHC (Box 1).5

Box 1. Definition of primary health care.

Primary health care achieves health and well-being through the following:

Meeting people’s health needs through comprehensive promotive, protective, preventive, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative care throughout the life course by strategically prioritizing health services, aimed at individuals through primary care and the population through public health functions as the central elements of integrated health services;

Systematically addressing the broader determinants of health (including social, economic, and environmental factors, as well as individual characteristics and behaviour) through evidence-informed policies and actions across all sectors; and

Empowering individuals, families, and communities to optimize their health as advocates for policies that promote and protect health and well-being, co-developers of health and social services, and self-carers and caregivers

Adapted from the World Health Organization.5

The Declaration of Astana provides us with a complete and precise definition of what PHC encompasses and the various ways to strengthen PHC. Family medicine is at the core of item 1.6,7

Even in the absence of a clear operational definition, 40 years of experience shows the value that PHC brings worldwide. Studies have shown that PHC reduces the leading causes of morbidity and mortality globally with statistical significance, including maternal, neonatal, and child deaths, as well as deaths from causes such as HIV-AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and vaccine-preventable diseases.8-10 It also reduces total health care costs, increases efficiency by improving access to preventive and promotive services, provides earlier diagnosis and treatment for many conditions, delivers care that focuses on the needs of the whole person, and reduces hospital admissions.11-14 Many of the interventions that are core to the benefit of PHC are related to primary care.9,15

Primary care

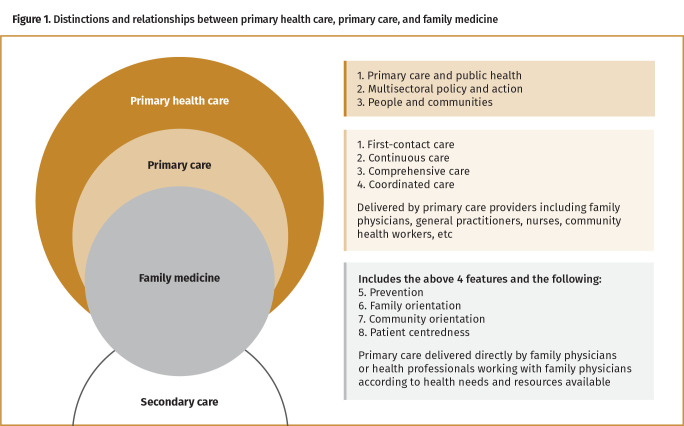

Primary care is an essential component of PHC (Figure 1). It describes a narrower concept of services delivered to individuals. primary health care is a broader term that derives from the core principles articulated by the WHO and describes an approach to health policy and service provision that includes services delivered to both individuals (primary care services) and populations (public health functions).16 Primary care is defined as “first-contact, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated care provided to populations undifferentiated by gender, disease, or organ system.”17 The 4 main features of primary care services are first-contact access for each new need; long-term, person-focused (not disease-focused) care; comprehensive care for most health needs; and coordinated care when it must be sought elsewhere. Based on the landmark research by Barbara Starfield, the global community judges primary care as “good,” according to how well these 4 features are fulfilled.11

Figure 1.

Distinctions and relationships between primary health care, primary care, and family medicine

Family physicians, general practitioners, and nonphysician primary care providers deliver primary care services. Nonphysician primary care providers are a broad group including but not limited to lay or community health workers, nurses, physician assistants, midwives, social workers, and pharmacists. In high-income countries (HICs) such as Canada, nonphysician primary care providers typically work in teams alongside family physicians. Interprofessional collaboration is recognized as an essential aspect of care for patients, particularly those with complex and chronic conditions,18 and is considered a key component for providing high-quality primary care.11

The evidence for primary care as a contributor to better health in HICs is strong; people who receive care from primary care physicians are healthier. Populations with access to primary care that encompasses all 4 features of primary care (first-contact; long-term and person-focused; comprehensive; and coordinated) have better health outcomes.11 Although the bulk of evidence for primary care comes from HICs, some evidence also exists for primary care–focused health initiatives in low-middle income countries (LMICs). In LMICs, populations with primary care programs have improved access to health care, decreased health costs, and improved health outcomes, including minimizing wealth-based disparities in mortality.9,19 Primary care is further strengthened by having physicians specializing in primary care—family physicians—involved in the delivery and management of health care services.

Family medicine

Family medicine is a subset of primary care. It is the delivery, organization, and management of health services by family physicians that distinguish family medicine from primary care.

To appreciate the concept of family medicine, we must first understand the history behind its development. The role, training, and title of the general practitioner working in primary care practice has changed over time and differs from country to country. The term general practitioner was first used in early 19th-century England to describe a new type of practitioner who was qualified to practise medicine, surgery, and midwifery.20 In early Canada, there were no medical schools, and practitioners were trained by apprenticeship until 1840 when the first medical schools were founded.20 In the early 19th century, all Canadian physicians were general practitioners in the sense that they practised both medicine and surgery, providing episodic care to patients when needed. Before 1966, in Canada, most physicians entered general practice after 1 year of internship.20 The impetus for the development of the field of family medicine came shortly after the publication of the Collings report in 1950, highlighting the poor conditions of general practice, low morale of general practitioners, and the lack of academic basis and of standards for general practice in the United Kingdom.21 Consequently, family medicine training programs were first implemented in 1966 in the United Kingdom and programs were implemented in the same decade in Canada and the United States to improve these conditions and meet the needs of individuals and populations.22 Coinciding with the introduction of postgraduate training in family medicine was the change in name from general practice to family medicine. This change in name symbolizes “the change of role from the general practitioner as a provider of episodic care to the broader concept of family doctor as promoter and maintainer of health in a defined population composed chiefly of family groups.”20

Globally, the terminology is quite jumbled, with the terms general practitioner and family physician used interchangeably. In some cases, the term general practitioner does include those who have specialized postgraduate training in primary care (as seen in the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Netherlands, for example). In other contexts, it refers to a physician who has completed an undergraduate medical degree with no specialty training in primary care, who provides generalized medical care at a grassroots level.22,23 In Canada, we use family physician to identify those who have completed postgraduate training in primary care and have passed the Certification Examination in Family Medicine.

Family medicine follows 8 core principles that guide education and training: access or first-contact care, comprehensiveness, continuity of care, coordination, prevention, family orientation, community orientation, and patient centredness. Of note, 4 of the 8 principles overlap with the components of primary care. Family medicine further expands primary care through the addition of prevention, family orientation, community orientation, and patient centredness. It is the provision of clinical care using these 8 principles that distinguishes family medicine from other medical specialties.22

Family physicians exercise their professional role by providing care either directly to patients or by working collaboratively with other health professionals based on the health needs and resources available in the communities in which they work.22,24 Family medicine is context specific; “the scope of each family doctor’s training and practice varies according to the contexts of their work, their roles, and the organization and resources of the health systems in each country.”22 There is not a one-size-fits-all model for family medicine practice. For example, in LMICs and remote regions of HICs, with few medical practitioners, family physicians may work in secondary care settings performing surgical procedures, including cesarean sections; may manage trauma; and may manage care for adults and children. In other contexts, family physicians may be clinical leads for hospital-based health care teams or may have leadership or administrative roles within teams.25 Given the diversity and breadth of roles of family physicians, they often straddle the primary and secondary care sectors (Figure 1). In many HICs with sufficient health forces, they typically form the backbone of the primary care system, serve a known population, and act as gatekeepers to more specialized care and the rest of the health care system.22 Having family physicians deliver and manage primary care increases the scope of care provided to patients and improves the efficiency and organization of primary care delivery.26-28

Family medicine continues to evolve at different rates around the world. By 1995, at least 56 countries had developed specialty training programs in family medicine, and many LMICs continue to develop and implement programs today.22,29 A survey in the Asia Pacific region showed family medicine training has been growing noticeably since 1995, with 53% of academic institutions reporting having a clinical postgraduate family medicine program.30 In the past 20 years, a handful of countries in sub-Saharan Africa have implemented family medicine training programs, including Ghana, Botswana, Uganda, Kenya, Nigeria, Lesotho, and—more recently—Ethiopia, Malawi, and Zimbabwe.22,23,31

From this discussion it is evident that PHC, primary care, and family medicine are 3 distinct sectors, yet they are very much interconnected (Figure 1). Family medicine is a subset of primary care delivered by family physicians. Good primary care is an essential component of a well-functioning PHC system.

An evolving field

In Canada, we have seen family medicine evolve over the past 50 years from the solo family physician providing primary care to a community, to working and managing comprehensive interdisciplinary teams to improve access and coordination of care for a defined population. We witnessed this transition over the past decade in several provinces with the introduction of Ontario’s family health teams, Quebec’s family medicine groups, Manitoba’s My Health Teams, Alberta’s primary care networks, and Prince Edward Island’s family health centres.32,33

In Ontario, the evolution continues with the Ontario Health Teams’ mandate to deliver a coordinated continuum of care to defined populations through a system of integrated primary and secondary care that is accountable for the care provided.34 Family physicians are integral to the development, management, and implementation of Ontario Health Teams given their central role in providing and facilitating seamless care for patients with public health, home care, other specialists, and hospitals.

Family physicians are also contributing to stronger PHC by advocating for policy changes such as access to universal drug plans, initiatives to end poverty, advocating for better housing solutions for the homeless and precariously housed, and demanding changes to the delivery of long-term care for aging populations.

In 2021, as we look to the future of family medicine in Canada, we can expect the role of family physicians to continue to evolve, playing a greater role in the delivery of primary care, strengthening integration with public health and secondary care, and increasing accessibility through the use of technology. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated our ability to see the role family physicians play in this evolution of health care. We witnessed the rapid introduction and scale-up of virtual clinics,35 albeit with caution not to lose the innumerable benefits of in-person care,36 the expansion of palliative and end-of-life care capacity,37 and the innovative redesign of necessary in-person visits.38 All of this was done alongside the required organization and delivery of care in COVID-19 centres in collaboration with public health and secondary care centres.39

In LMICs we expect the trajectory of family medicine to be unique and context specific; for example, in regions where there are substantial health force shortages, the role of the family physician at the time of implementation will be that of clinical leader and consultant to nonphysician primary care workers.25,31 In fact, we expect Canadian family physicians to learn lessons from global colleagues about how to implement task shifting and interdisciplinary care better to expand service delivery without compromising quality or increasing costs.

Conclusion

Family medicine in Canada continues to evolve to support primary care and PHC systems that achieve health and well-being for all. Globally, family medicine is growing as a way of strengthening PHC in LMICs. As these initiatives are implemented and evaluated, it is vital to recognize the distinctions between family medicine, primary care, and PHC. It is also important to remember that family medicine is an ever evolving field, intending to meet the changing needs of the populations we serve.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared

The opinions expressed in commentaries are those of the authors. Publication does not imply endorsement by the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article se trouve aussi en français à la page 656.

References

- 1.Position statement: appropriate use of family medicine terminology. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2019. Available from: https://www.cfpc.ca/CFPC/media/Images/News/News%20PDF/Protecting-Family-Medicine-Terms-Position-Statement-Dec-6-19-Web-ENG.pdf. Accessed 2021 May 16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Consultative Council on Medical and Allied Services . Interim report on the future provision of medical and allied services 1920 (Lord Dawson of Penn). London, UK: Ministry of Health; 1920. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September 1978. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Social determinants of health. WHO called to return to the Declaration of Alma-Ata. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/declaration-of-alma-ata. Accessed 2021 May 16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Declaration of Astana. Astana, Kazakhstan: World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund; 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/primary-health/conference-phc/declaration. Accessed 2021 May 16. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Astana Declaration: the future of primary health care? Lancet 2018;392(10156):1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CFPC Position Statement in support of the Declaration of Astana. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2020. Available from: https://www.cfpc.ca/uploadedFiles/About_Us/Sadok_Besrour_Centre_for_Innovation_in_Global_Health/CFPC-Position-Statement-in-Support-of-the-Declaration-of-Astana-ENG.pdf. Accessed 2021 May 16. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The World Health Report 2008. Primary health care. Now more than ever. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: https://www.who.int/whr/2008/whr08_en.pdf. Accessed 2021 Jul 7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kruk ME, Porignon D, Rockers PC, Van Lerberghe W.. The contribution of primary care to health and health systems in low- and middle-income countries: a critical review of major primary care initiatives. Soc Sci Med 2010;70(6):904-11. Epub 2010 Jan 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry HB, Sacks E, Schleiff M, Kumapley R, Gupta S, Rassekh BM, et al. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 6. Strategies used by effective projects. J Glob Health 2017;7(1):010906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J.. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83(3):457-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Starfield B. Primary care: an increasingly important contributor to effectiveness, equity and efficiency of health services. SESPAS report 2012. Gac Sanit 2012; 26(Suppl 1):20-6. Epub 2012 Jan 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss LJ, Bustein J.. Faithful patients: the effect of long-term physician-patient relationships on the costs and use of health care by older Americans. Am J Public Health 1996;86(12):1742-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedberg MW, Hussey PS, Schneider EC.. Primary care: a critical review of the evidence on quality and costs of health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(5):766-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L.. The contribution of primary care systems to health outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, 1970-1998. Health Serv Res 2003;38(3):831-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muldoon LK, Hogg WE, Levitt M.. Primary care (PC) and primary health care (PHC). What is the difference? Can J Public Health 2006;97(5):409-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starfield B. Is primary care essential? Lancet 1994;344(8930):1129-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reeves S, Goldman J, Gilbert J, Tepper J, Silver I, Suter E, et al. A scoping review to improve conceptual clarity of interprofessional interventions. J Interprof Care 2011;25(3):167-74. Epub 2010 Dec 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macinko J, Starfield B, Erinosho T.. The impact of primary healthcare on population health in low- and middle-income countries. J Ambul Care Manage 2009;32(2):150-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McWhinney IR. General practice in Canada. Int J Health Serv 1972;2(2):229-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collings JS. General practice in England today—a reconnaissance. Lancet 1950;255(6604):555-85. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kidd M, editor. The contribution of family medicine to improving health systems. A guidebook from the World Organization of Family Doctors. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arya N, Gibson C, Ponka D, Haq C, Hansel S, Dahlman B, et al. Family medicine around the world: overview by region. The Besrour Papers: a series on the state of family medicine in the world. Can Fam Physician 2017;63:436-41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bentzen BG, Bridges-Webb C, Carmichael L, Ceitlin J, Feinbloom R, Metcalf D, et al. The role of the general practitioner/family physician in health care systems: a statement from WONCA, 1991. Belgium, Brussels: World Organization of Family Doctors; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mash B, Reid S.. Statement of consensus on family medicine in Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2010;2(1):a151. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Continuity of care with family medicine physicians: why it matters. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2015. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/UPC_ReportFINAL_EN.pdf. Accessed 2021 May 16. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glazier RH, Moineddin R, Agha MM, Zagorski B, Hall R, Manuel DG, et al. The impact of not having a primary care physician among people with chronic conditions. ICES investigative report. Toronto, ON: ICES; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strumpf E, Ammi M, Diop M, Fiset-Laniel J, Tousignant P.. The impact of team-based primary care on health care services utilization and costs: Quebec’s family medicine groups. J Health Econ 2017;55:76-94. Epub 2017 Jul 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haq C, Ventres W, Hunt V, Mull D, Thompson R, Rivo M, et al. Where there is no family doctor: the development of family practice around the world. Acad Med 1995;70(5):370-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng CJ, Teng CL, Abdullah A, Wong CH, Hanafi NS, Phoa SSY, et al. The status of family medicine training programs in the Asia Pacific. Fam Med 2016;48(3):194-202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mash R, Howe A, Olayemi O, Makwero M, Ray S, Zerihun M, et al. Reflections on family medicine and primary healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(Suppl 3):e000662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peckham A, Ho J, Marchildon G.. Rapid review 1. Policy innovations in primary care across Canada. Toronto, ON: North American Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2018. Available from: https://ihpme.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/NAO-Rapid-Review-1_EN.pdf. Accessed 2021 May 16. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutkin C. The future of family practice in Canada. The Patient’s Medical Home. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:1224 (Eng), 1223 (Fr). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ontario Health Teams. Toronto, ON: Ontario College of Family Physicians; 2019. Available from: https://www.ontariofamilyphysicians.ca/tools-resources/timely-trending/ontario-health-team-oht-overview. Accessed 2019 Feb 11. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhattacharyya O, Payal A.. Adapting primary care to respond to COVID-19 [blog]. Can Fam Physician 2020. Apr 9. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/news/2020/04/09/04-09-1. Accessed 2021 Jul 22.

- 36.Telner D. Unsticking the pendulum [blog]. Can Fam Physician 2020. Aug 25. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/news/2020/08/25/08-25. Accessed 2021 Jul 22.

- 37.Khosravani H, Steinberg L, Incardona N, Quail P, Perri GA.. Symptom management and end-of-life care of residents with COVID-19 in long-term care homes. Can Fam Physician 2020;66:404-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferguson KB, Bradford J.. A parking-lot injection clinic: an adaptation to the COVID-19 pandemic [blog]. Can Fam Physician 2020. Jul 14. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/news/2020/07/14/07-14. Accessed 2021 Jul 22.

- 39.Zimmer R. Primary medical care can help to protect acute care capacity, if properly incorporated into local COVID-19 pandemic preparedness and response [blog]. Can Fam Physician 2020. Apr 14. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/news/2020/04/14/04-14. Accessed 2021 Jul 22.