Abstract

Objective

To summarize and synthesize qualitative studies that report patient and physician perspectives on continuity of care in family practice.

Data sources

MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), and PsycInfo (Ovid) were searched for qualitative primary research reporting perspectives of patients, physicians, or both, on continuity of care in family practice.

Study selection

English-language qualitative studies were selected (eg, interviews, focus groups, mixed methods) that were conducted in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, New Zealand, or Australia.

Synthesis

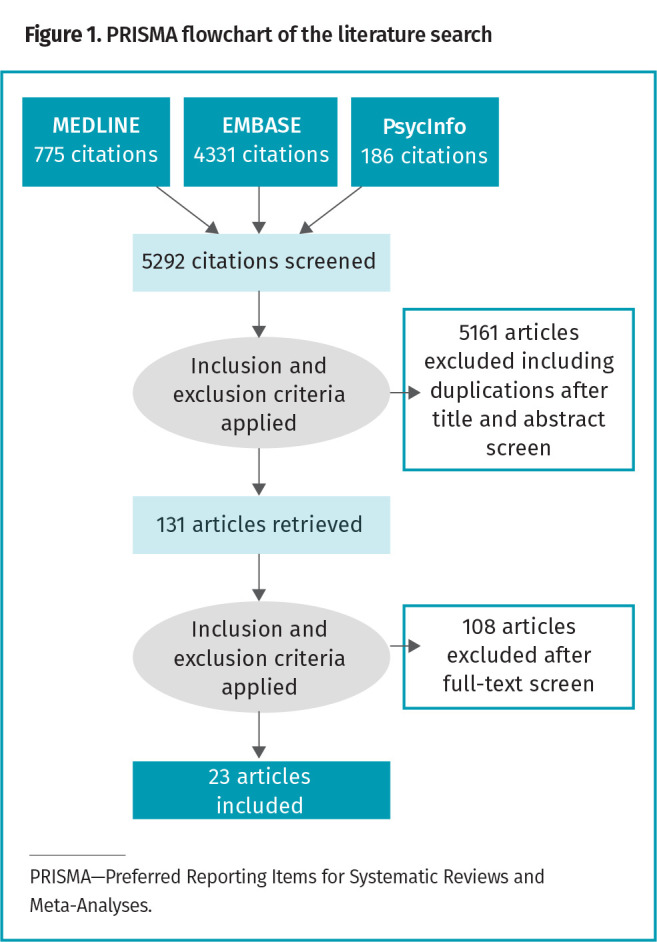

Themes were extracted, summarized, and synthesized. Six overarching themes emerged: continuity of care enables person-centred care; continuity of care increases quality of care; continuity of care leads to greater confidence in medical decision making; continuity of care comes with drawbacks; the absence of continuity of care may lead to medical and psychological harm; and continuity of care can foster greater joy and meaning in a physician’s work. Out of the 6 themes, patients and physicians shared the first 5.

Conclusion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first qualitative review reporting the unique perspectives of both patients and family physicians on continuity of care. The findings add nuanced insight to the importance of continuity of care in family practice.

Résumé

Objectif

Résumer les études qualitatives qui présentent les points de vue des patients et des médecins sur la continuité des soins en pratique familiale, et en faire la synthèse.

Sources d’information

Une recension a été effectuée dans MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid) et PsycInfo (Ovid) en quête de recherches qualitatives primaires signalant les points de vue des patients, des médecins ou des 2 groupes sur la continuité des soins en pratique familiale.

Sélection des études

Nous avons sélectionné des études qualitatives en anglais (p. ex. des entrevues, des groupes de discussion, des méthodes mixtes), effectuées au Canada, aux États-Unis, au Royaume-Uni, dans l’Union européenne, en Nouvelle-Zélande ou en Australie.

Synthèse

Les thèmes ont été cernés, résumés et synthétisés. Six thèmes omniprésents se sont dégagés de l’exercice : la continuité des soins facilite les soins centrés sur la personne; la continuité des soins augmente la qualité des soins; la continuité des soins entraîne une plus grande confiance à l’endroit de la prise de décisions médicales; la continuité des soins comporte des inconvénients; l’absence de continuité dans les soins peut causer des préjudices médicaux et psychologiques; et la continuité des soins peut apporter plus de satisfaction professionnelle et donner plus de sens au travail des médecins. Parmi les 6 thèmes, les patients et les médecins partagent la même opinion sur les 5 premiers.

Conclusion

À la connaissance des auteurs, il s’agit de la première revue qualitative qui signale les perspectives uniques des patients et des médecins de famille sur la continuité des soins. Ces constatations donnent un aperçu plus nuancé de l’importance de la continuité des soins en pratique familiale.

Continuity of care is a core element of family practice.1-3 Continuity of care is typically defined as a longitudinal relationship with a personal physician or care team.4,5 A substantial body of literature demonstrates the benefits of this kind of relationship throughout the continuum of health care. Among other improvements, continuity of care leads to a higher quality of care, more preventive care, decreased emergency department visits, and reduced odds of avoidable hospitalization.6-12 A 2018 systematic review by Gray et al showed that increased continuity of care with a physician was associated with decreased mortality.13 Similarly, a 2020 systematic review by Baker et al showed decreased mortality in the context of primary care continuity.14 The quantitative evidence is clear: continuity of care is good for people, care teams, populations, and health systems.

Despite the large body of literature on the quantitative benefits, there are few evidence syntheses of why patients or physicians value continuity.15,16 Qualitative perspectives provide thick descriptions of the meaning and relevance of the experience of continuity. A qualitative synthesis combining these perspectives would bring a nuanced and descriptive narrative of the underlying experiences of both patients and physicians with continuity of care. Understanding a holistic view of the unique perspectives from both patients and physicians, moreover, can inform healthy primary care policy.

Continuity of care in primary care is mainly interpreted in the context of a longitudinal relationship with a clinician (relational continuity).4,5 Secondarily, continuity of care can be within a medical records system, be with a family, be through varying practice settings, or even be team based.4,17,18 Our analysis mainly refers to relational continuity, but captures emerging dimensions and nuances of continuity of care when relevant.4 The objective of our narrative review was to summarize and synthesize the literature on patient and physician perspectives of continuity of care in family practice.

METHODS

Data sources

Our intent was to capture the qualitative studies in which continuity of care was the primary objective of the study. We conducted a comprehensive structured search for qualitative studies with the phrase continuity of care in the context of family practice. As our search was preplanned, we consulted with a research librarian in formulating our methodology. Following the recommendations of Greenhalgh et al, we conducted a structured narrative review for its ability to provide interpretation and critique.19,20

We searched MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), and PsycInfo (Ovid), as these electronic databases were most relevant to our research question. The search was conducted on November 11, 2019. We used the McMaster University Health Information Research Unit qualitative filter for the best balance of sensitivity and specificity in searching for qualitative evidence. The general search strategy and an example of the full electronic search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid) are available from CFPlus.*

Study selection

A single reviewer screened titles and abstracts of all retrieved citations in Ovid and removed items that were clearly irrelevant to our inclusion criteria (S.C.N.). The remaining references were imported into Covidence, an online literature review software program. Study duplicates were removed in Covidence (S.C.N.). Three reviewers (D.A.N., N.Y.S., and S.C.N.) then divided and screened titles, abstracts, and if needed, full text, to determine eligibility for inclusion, with an overlapping review by at least 2 authors. Finally, full article texts were concurrently assessed for inclusion by all 3 authors. Any discrepancies between reviewers in the last 2 steps were resolved by majority consensus among the 3 reviewers.

Inclusion criteria were English-language, qualitative studies (eg, interviews, focus groups, mixed methods) conducted in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, New Zealand, or Australia, with a main objective of exploring patient or physician perspectives on continuity of care in family or general practice. Exclusion criteria included inpatient, hospital, or emergency settings, and a focus on medical specialists other than family physicians, as well as independent allied health practitioners or alternative providers. Although we recognize their important role in primary care, we excluded nurse practitioners to focus our analysis on family physicians. For the purpose of this analysis, we excluded the articles that merely found continuity of care as a theme or a relevant result of an otherwise unrelated study. We did not include the gray literature or opinion pieces.

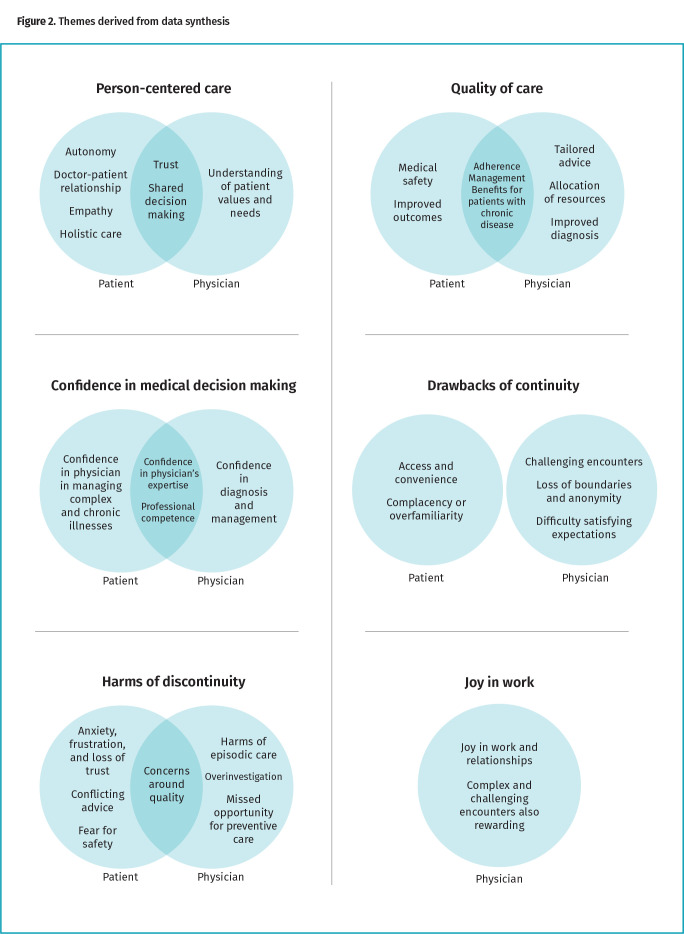

Of the 1172 retrieved articles, 131 were deemed relevant to continuity of care during preliminary screening of titles and abstracts. Of these, 102 remained eligible after full-text screening. After further review, 23 of these articles met inclusion criteria in that they explicitly examined continuity of care in family practice as a primary objective. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart of our literature search.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the literature search

Synthesis

Included studies were examined using NVivo 12 qualitative data analysis software. Only qualitative and mixed-methods studies were scanned. If a study used a mixed-methods approach, only the qualitative components of the study were included. This approach included extracting and aggregating text from studies in NVivo 12 to systematically capture overlapping concepts between studies.

We took an inductive approach to deriving themes. S.C.N. coded articles with patient or combined perspectives. N.Y.S. coded articles with physician perspectives. We iteratively discussed emerging concepts over the course of several working group meetings to signal reliability. During these working groups, 2 reviewers (N.Y.S. and S.C.N.) summarized emerging perspectives. Both reviewers then discussed these perspectives for consistency across studies with a content expert (D.A.N.). S.C.N., N.Y.S., and D.A.N. sought consensus on key themes, looking to group perspectives into mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories. These categories are reported below as 6 theme summary statements. We also selected study participant quotations from the retrieved references to further illustrate individual perspectives on continuity of care.

SYNTHESIS

The themes are outlined below. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the studies included in the synthesis.17,21-42 Figure 2 shows an overview of the themes derived from the synthesis.

Table 1.

Studies examining patient and physician perspectives on continuity of care with family doctors

| AUTHORS | YEAR | COUNTRY | SAMPLE SIZE | PARTICIPANTS | TECHNIQUE | DATA ANALYSIS | THEMES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alazri et al21 | 2006 | UK | 79 | Patients | Focus groups | Framework approach | 1, 2, 4, 5 |

| Boulton et al22 | 2006 | UK | 31 | Patients | In-depth interviews | Qualitative analysis* | 1, 2, 4, 5 |

| Von Bültzingslöwen et al23 | 2006 | Sweden | 14 | Patients | Open individual interviews | Content analysis | 1–5 |

| Cowie et al24 | 2009 | UK | 30 | Patients | Semistructured interviews | Qualitative analysis* | 2–5 |

| Detz et al25 | 2013 | US | 712 | Patients | Internet reviews | Content analysis | 1, 2, 4 |

| Frederiksen et al26 | 2009 | Europe | 22 | Patients | Semistructured interviews | Interpretive phenomenologic analysis | 1, 2, 5 |

| Frederiksen et al27 | 2010 | Europe | 22 | Patients | Semistructured interviews | Interpretive phenomenologic analysis | 1, 3 |

| Gabel et al28 | 1993 | US | 60 | Patients | Ethnographic interviews | Ethnographic analysis | 1–4 |

| Den Herder-van der Eerden et al29 | 2017 | Europe | 152 | Patients | Semistructured interviews | Qualitative content analysis | 1, 4, 5 |

| Liaw et al30 | 1992 | Australia | 96 | Patients | Focus group interviews | Qualitative analysis* | 4, 5 |

| Michiels et al31 | 2007 | Europe | 17 | Patients | Face-to-face, in-depth interviews | Grounded theory | 1, 4 |

| Naithani et al32 | 2006 | UK | 25 | Patients | In-depth, semistructured interviews | Qualitative analysis* | 1–5 |

| Pandhi et al33 | 2007 | US | 40 | Patients | In-person, open-ended interviews | Grounded theory | 1–5 |

| Rhodes et al34 | 2014 | UK | 38 | Patients | In-depth interviews | Qualitative analysis* | 1–5 |

| Tarrant et al35 | 2010 | UK | 20 | Patients | Semistructured interviews | Constant comparative method | 1, 3, 5 |

| Tarrant et al36 | 2015 | UK | 50 | Patients | Semistructured, face-to-face interviews | Constant comparative method | 1, 4, 5 |

| Alazri et al37 | 2007 | UK | 52 | GPs and practice nurses | Semistructured individual interviews | Framework approach | 1–3, 5 |

| Delva et al38 | 2011 | Canada | 37 | Physicians | Semistructured focus group interviews | Constant comparison | 1, 3–6 |

| Kerr et al17 | 2012 | Canada | 37 | Physicians | Focus groups | Content analysis | 2–4, 6 |

| Ridd et al39 | 2006 | UK | 24 | Physicians | In-depth interviews | Constant comparative method | 1–6 |

| Schultz et al40 | 2012 | Canada | 37 | Physicians | Focus groups | Phenomenologic approach | 1–4, 6 |

| Sturmberg41 | 2000 | Australia | 22 | Physicians | Focus groups | Qualitative analysis* | 1, 2, 4 |

| Guthrie and Wyke42 | 2006 | UK | 48 | Patients and physicians | Semistructured interviews | Interpretive thematic analysis | 1–4, 6 |

UK—United Kingdom, US—United States.

Unclear, not explicitly reported.

Figure 2.

Themes derived from data synthesis

Theme summary statement 1: continuity of care enables person-centred care

We used the framework proposed by The Health Foundation, which presents person-centred care as promoting dignity, respect, and compassion, in a coordinated, personalized, and enabling manner.43,44

Patients. With continuity of care, patients perceived stronger relationships with their physicians.22,25-27 Patients experienced the capacity to exercise autonomy and participate in shared decision making.23,31-33 In cases where patients were dealing with chronic illness or sensitive issues, they felt they were treated with respect, listened to, and had their concerns taken seriously.21,23,26-28,31-36,42 Patients also believed they received greater empathy, recognition, and understanding from their physicians.23,25,26,28,29,31-33 Continuity facilitated an environment where patients thought they were treated holistically.26,31-33 They felt treatments were tailored to their individual needs.22,23,31-33,42 Patients felt supported through their illness experience.31,32,36,42 Continuity promoted trust in a physician’s competence and confidence that the physician cared for the patient’s best interest.21-23,25,28,29,31-33,35,37,42 Gabel et al shared a comment by a patient who appreciated the holistic understanding that continuity brought:

Well, health is more than one thing. It’s how well you relate to your work, your family, your friends, your society .… How you treat your body. The more the doctor knows about those kinds of things, the better prepared the doctor is to treat you.28

Physicians. Physicians believed continuity led to mutual trust, which created psychological safety for patients to share sensitive issues and deliberate difficult problems.21,31,37-41 A trusting relationship was seen as itself therapeutic.40 Physicians noted a more nuanced understanding of patient values and needs, and thus shared decision making.41 In a focus group by Schultz et al, a physician commented: “You have a thousand pieces of a puzzle; you start off with a 25-piece puzzle, but as the relationship grows and grows you get more and more pieces to clarify things more and more.”40

Theme summary statement 2: continuity of care increases quality of care

Patients. When a relationship with a doctor was continuous, patients indicated they were more willing to adhere to treatment plans and continue with monitoring.21,32,33 Patients expressed how there was a benefit to medical safety, in that they were less likely to be harmed by error.21,23,24,42 Overall, patients experienced better outcomes, including faster diagnosis and better chronic disease management.21-23,25,26,28,32-34,37 In an interview by Frederiksen et al, a patient with chronic illness shared the following:

I would feel unsecure not consulting a regular GP. I would feel unsecure if one was to continuously meet new faces and inform them. Even though they have our records, you will never have the same contact and thoroughness, if they have not followed you for many years … and he performs the same examinations every time; and then, it also makes me secure that he knows, and that I know, what is going to happen to me.26

Physicians. Physicians believed that continuity allowed them to give more tailored advice, which improved treatment adherence.37,40 Physicians expressed how they were able to diagnose and treat more effectively.17,39,40 Continuity was thought to improve management and health outcomes.37,39-41 Physicians believed they could better allocate resources, using fewer investigations and medications.40 Overall, physicians expressed benefits to care quality, in particular for patients with serious, chronic, complex, or psychological problems.17,37,39,40

Theme summary statement 3: continuity of care leads to greater confidence in medical decision making

Patients. Especially in the management of complex, chronic, emotional, and serious illness, patients were confident in their physician and their physician’s advice.23,24,27,28,32-35,42 They trusted their physician’s expertise, in that doctors were seen as more competent in managing problems in the context of the individual’s history, family, and social circumstances.23,42

Physicians. With continuity, physicians were more confident in their ability to make diagnostic and management decisions, especially in the face of complexity or other challenges.17,37-40 They also felt more professionally competent, particularly in dealing with emotionally challenging presentations and slowly evolving conditions.17,38,40 Sturmberg shared the following sentiment from a physician in a focus group:

It is much easier when you see a patient that has been coming to you for some time and you know all the problems and probably a lot about the family and all the other outside things that you wouldn’t know with a new patient, for example. It often has a lot of bearing on their illness and their treatment, too.41

Theme summary statement 4: continuity of care comes with drawbacks, including access and complacency

Patients. Access and convenience were seen as trade-offs to continuity, but patients were generally willing to wait to see a personal physician especially for chronic conditions.21-25,28-33,36,42 Some patients felt they experienced a missed diagnosis owing to complacency or overfamiliarity, as in the section’s quote below.21,42 In this light, patients sometimes appreciated a fresh second opinion.34 Alazri et al shared the perspective of a patient who felt adversely affected by continuity of care:

I mean I had an [incident] here .… I saw my doctor, and I’d been complaining about pains in me [sic] chest for about 2 year[s], anyway it wasn’t until I went to hospital and had tests up there, and I came down, back down to see my doctor and he said, “Oh I’m glad they’ve found something wrong with you,” I thought, “Well 2 year[s] I’ve been complaining.”21

Physicians. Physicians expressed distress about particularly difficult encounters, but nonetheless described satisfaction and personal growth in building a therapeutic relationship in these contexts.38,40 Physicians also discussed challenges in relation to boundaries and loss of anonymity.17,38-40 It was also more difficult to satisfy expectations around time constraints and office availability while maintaining work-life balance.17,41 A physician described the challenge of boundaries and expectations in a focus group with Schultz et al: “It can be exhausting … you can feel as if you have the weight of the world on your shoulders.”40

Theme summary statement 5: the absence of continuity of care may lead to medical and psychological harm

Patients. Patients experiencing discontinuity, meaning not seeing their usual physician, expressed general dissatisfaction.24 They felt like their physicians did not know them.21-23,26,34 Patients responded to a lack of continuity by attempting to self-manage, delaying care, or withdrawing from care.32,33 In one instance, a patient believed discontinuity was likely to lead to diagnostic error.34 Patients felt frustrated and anxious in repeating their narratives, felt an overwhelming burden in self-care, and heard conflicting advice from different clinicians.21,23,29,32 Some lost trust or became sceptical of their care team.26,35 Others felt anxious, uncertain, and insecure in their care.23,24,29,33,34,36 Patients feared for their safety, worrying that their problems would not be cared for or serious illness would be missed.21,24,30,32,34 Pandhi et al shared the following quote from a patient who withdrew from discontinuous care:

‘Cause when I had other doctors and I didn’t feel comfortable around them I didn’t go to the doctor. They would set appointments for me but I wouldn’t go. So that’s why my health got like it is because I didn’t want to go in ‘cause I wasn’t comfortable.33

Von Bültzingslöwen et al shared a comment from another patient experiencing discontinuity: “Not to be believed … to have to repeat everything again. It made me so vulnerable. Now I panic before each appointment … will I get a doctor that understands how I feel this time?”23

Physicians. Physicians perceived several drawbacks in discontinuity. Episodic care at walk-in clinics, for instance, was seen as useful for acute conditions but harmful for chronic or sensitive conditions.37 Informational continuity through medical records was seen as an incomplete replacement for longitudinal care by a personal physician, as it did not capture important aspects in the doctor-patient relationship.37-39 Discontinuity in the context of cross-coverage led to risks from confusion, missed opportunities for preventive or proactive care, as well as a tendency toward overinvestigation and overtreatment.39 Alazri et al shared the reflections of an interviewed physician:

I think … [the] number of times that we have problems purely and simply, it’s not that they’ve been badly treated, mistreated, not diagnosed properly, it’s purely and simply that we just haven’t got the information. We just don’t know what happened and you know, you end up having to chase things up all the time to try and find out why and who did this.37

Theme summary statement 6: continuity of care can foster greater joy and meaning in a physician’s work

Physicians. Physicians found joy and meaning in the relationships built with their patients over time and through important life events.17,38-40 The therapeutic relationships were seen as rewarding to physicians, even in encounters that were more complex or challenging.40 Schultz et al shared the following quote from an interviewed physician:

With continuity you really become part of the patient’s life; you’re not just somebody that they’re coming to consult, but you’re really a player—in the money—and that’s when the relationship, both ways, is very rewarding.40

DISCUSSION

We describe 6 themes related to continuity of care in family practice, the first 5 of which were shared by both patients and physicians (Figure 2). Our results show mostly positive attitudes toward continuity from both patients and physicians, and add nuance to the existing literature supporting continuity.

Previous qualitative syntheses have examined patient perspectives on continuity.12,15,16,45 However, there has been little focus on the overlapping experiences of patients and physicians. Our study furthers the knowledge on continuity of care by revealing this overlap. The first set of themes shared by patients and physicians relates to how continuity of care enables person-centred care, increases quality of care, and leads to greater confidence in medical decision making. These findings are consistent with the existing qualitative literature on continuity, where continuity was found to be especially important in care of people with serious, chronic, complex, or psychological concerns.12,15,16

Another theme patients and physicians shared related to the drawbacks of continuity. Existing literature suggests difficulties in accessing continuous care and proposes a risk of delayed diagnosis.12,46,47 A report from the Nuffield Trust suggests that not all patients value continuity, particularly when they see themselves as healthy or do not feel like they have a good relationship with their clinician.12 In our synthesis, we found little overlap between patient and physician perspectives toward this theme (drawbacks of continuity in Figure 2). Patients identified the trade-off between access and continuity, expressed worry over missed diagnoses, and appreciated having a second opinion. In contrast, physicians expressed concern over managing boundaries and expectations. Both groups agreed that there were challenges to continuity of care.

Previous quantitative studies have highlighted the harms of discontinuity of care; these harms included tangible outcomes such as increased rehospitalization, increased health service costs, a risk to safety, and higher all-cause mortality.13,14,18,36,48,49 The qualitative literature on patient experiences of continuity reflects possible mechanisms behind this theme, with patients experiencing discontinuity with uncertainty and vulnerability, including communication failures between transitions in care.15 In our synthesis, both patients and physicians expressed how the absence of continuity of care has the potential to cause medical and psychological harm. Patients became frustrated and withdrew from discontinuous care, reflecting findings of other studies on continuity.15 Meanwhile, physicians saw discontinuity as risky and a missed opportunity for preventive care. These findings further the existing literature by bridging the shared patient and physician perspectives of the harms of discontinuity, and shed light on potential mechanisms for these harms.

For health professionals, caring for others can be a joyful and meaningful endeavour.50 A report including clinician perspectives on continuity of care supports the view that continuity is a core element of family practice, contributes to joy and meaning in work, and “makes us who we are” as family physicians.3,12 Our synthesis was consistent with these attitudes, showing that continuity of care fostered greater joy in work for physicians. Joy in work is known to be a factor associated with safe, high-quality, and compassionate care.50 Our findings suggest that continuity of care is a key feature of joy and meaning in a family physician’s work—and by extension important to recruitment and retention of clinicians in family practice.

Despite the generally positive sentiment toward continuity in our synthesis, there are challenges to achieving continuity of care. These challenges are reflected in the drawbacks to continuity of care (theme summary statement 4). Access was a concern for patients, and maintaining boundaries was the corresponding concern for physicians. It is unclear yet what balance of the 2 makes sense, and how to pragmatically enable a system in which we emphasize patient needs while also respecting the human clinician on the other side.

We recommend that family physicians and policy makers recognize and advocate for the value of continuity of care in family practice. By acknowledging the importance of this key element, individual practices, primary care teams, and policy makers should support practice arrangements and policies that prioritize continuity.12,51 In Canada, the Patient’s Medical Home by the College of Family Physicians of Canada includes continuity of care in its vision for practices and policy makers.52 Qualitative research provides uniquely nuanced insights in informing these recommendations. Although our research explores reasons why continuity of care is valuable, further research is needed to explore how it can be implemented—including the balance between access to physicians and continuity of care, the appropriate blend of continuity with a clinician or with a dedicated team, and how health systems can promote the various forms of continuity to improve integration and quality of care.4,12,51

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, in excluding clinicians other than general practitioners and family physicians, we are omitting studies relevant to continuity of care with other specialists, nurse practitioners, and other health professionals. Second, although we used a systematic way of including relevant qualitative studies, our narrative review did not assess the quality of the studies included. Third, the techniques that we used to develop themes were inherently subjective. We mitigated this subjectivity by formulating themes in collaborative working groups with a content expert. That said, our method of qualitative synthesis adds depth and nuance that remained uncaptured in the quantitative literature.

Conclusion

Continuity of care matters. Our review and synthesis of existing studies reveals the value that patients and physicians place on continuity of care in family practice. It also serves as a call to action for more ambitious policies and practices around primary care to prioritize continuity of care. After all, continuity of care is good for people, care teams, populations, and health systems. Continuity of care is a key element to primary care, and thus our support of continuity of care is essential to healthy primary care policy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr Allan Detsky from the University of Toronto, who provided thoughtful commentary and guidance on the manuscript. We also thank Kaitlin Fuller, Education & Liaison Librarian at the University of Toronto, for her guidance with the search strategy creation.

Editor’s key points

▸ Continuity of care is a core element in family practice. It has considerable individual, population, and health systems benefits, and yet there is no synthesis of the qualitative research on why continuity of care is valuable to patients and family doctors.

▸ Through their narrative review, the authors found mostly positive attitudes toward continuity from both patients and physicians, and their findings add nuance to the existing literature supporting continuity.

▸ Continuity of care is good for people, care teams, populations, and health systems, but the authors also found that continuity of care comes with challenges, including access, complacency, and maintaining boundaries.

Points de repère du rédacteur

▸ La continuité des soins est un élément fondamental dans la pratique familiale. Elle apporte des bienfaits considérables sur les plans individuel, populationnel et systémique. Pourtant, il n’existe pas de synthèse de la recherche qualitative sur les raisons expliquant pourquoi la continuité des soins est précieuse pour les patients et les médecins de famille.

▸ Au cours de leur revue narrative, les auteurs ont constaté des attitudes majoritairement positives envers la continuité, à la fois chez les patients et chez les médecins, et leurs observations ajoutent des nuances à la littérature scientifique existante en faveur de la continuité.

▸ La continuité des soins est bonne pour les personnes, les équipes de soins, les populations et les systèmes de santé, mais les auteurs ont aussi trouvé que la continuité des soins présente des défis, notamment au chapitre de l’accès, d’une possible complaisance et du maintien de distances appropriées.

Footnotes

The general search strategy and an example of the full electronic search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid) are available from www.cfp.ca. Go to the full text of the article online and click on the CFPlus tab.

Contributors

Dr Dominik Alex Nowak, Natasha Yasmin Sheikhan, and Dr Ross E.G. Upshur contributed to the conception and design of the study. Dr Dominik Alex Nowak, Natasha Yasmin Sheikhan, and Sumana Christina Naidu conducted the literature review and synthesis. All authors contributed to preparing the manuscript for submission. Drs Ross E.G. Upshur and Kerry Kuluski co-supervised the study.

Competing interests

Dr Dominik Alex Nowak discloses consulting fees from Telus outside of the submitted work.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

References

- 1.Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K.. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med 2014;12(2):166-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J.. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83(3):457-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McWhinney IR. Primary care: core values. Core values in a changing world. BMJ 1998;316(7147):1807-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid RJ, Haggerty JL, McKendry R.. Defusing the confusion: concepts and measures of continuity of healthcare. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R, et al. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ 2003;327(7425):1219-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accelerating Change Transformation Team . Evidence summary: the benefits of relational continuity in primary care. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Medical Association; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bierman AS, Dunn JR.. Swimming upstream. Access, health outcomes, and the social determinants of health. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21(1):99-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabana MD, Jee SH.. Does continuity of care improve patient outcomes? J Fam Pract 2004;53(12):974-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christakis DA, Wright JA, Koepsell TD, Emerson S, Connell FA.. Is greater continuity of care associated with less emergency department utilization? Pediatrics 1999;103(4 Pt 1):738-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menec VH, Sirski M, Attawar D, Katz A.. Does continuity of care with a family physician reduce hospitalizations among older adults? J Heal Serv Res Policy 2006;11(4):196-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Northwood M, Ploeg J, Markle-Reid M, Sherifali D.. Integrative review of the social determinants of health in older adults with multimorbidity. J Adv Nurs 2018;74(1):45-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer W, Hemmings N, Rosen R, Keeble E, Williams S, Imison C.. Improving access and continuity in general practice. Practical and policy lessons. London, UK: Nuffield Trust; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray DJP, Sidaway-Lee K, White E, Thorne A, Evans PH.. Continuity of care with doctors—a matter of life and death? A systematic review of continuity of care and mortality. BMJ Open 2018;8(6):e021161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker R, Freeman GK, Haggerty JL, Bankart MJ, Nockels KH.. Primary medical care continuity and patient mortality: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2020;70(698):e600-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haggerty JL, Roberge D, Freeman GK, Beaulieu C.. Experienced continuity of care when patients see multiple clinicians: a qualitative metasummary. Ann Fam Med 2013;11(3):262-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waibel S, Henao D, Aller MB, Vargas I, Vázquez ML.. What do we know about patients’ perceptions of continuity of care? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Qual Heal Care 2012;24(1):39-48. Epub 2011 Dec 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerr JR, Schultz K, Delva D.. Two new aspects of continuity of care. Can Fam Physician 2012;58:e442-9. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/content/cfp/58/8/e442.full.pdf. Accessed 2021 Aug 9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira Gray D, Evans P, Sweeney K, Lings P, Seamark D, Seamark C, et al. Towards a theory of continuity of care. J R Soc Med 2003;96(4):160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenhalgh T, Thorne S, Malterud K.. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur J Clin Invest 2018;48(6):e12931. Epub 2018 Apr 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutton A, Clowes M, Preston L, Booth A.. Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Info Libr J 2019;36(3):202-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alazri MH, Neal RD, Heywood P, Leese B.. Patients’ experiences of continuity in the care of type 2 diabetes: a focus group study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56(528):488-95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boulton M, Tarrant C, Windridge K, Baker R, Freeman GK.. How are different types of continuity achieved? A mixed methods longitudinal study. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56(531):749-55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Von Bültzingslöwen I, Eliasson G, Sarvimäki A, Mattsson B, Hjortdahl P.. Patients’ views on interpersonal continuity in primary care: a sense of security based on four core foundations. Fam Pract 2006;23(2):210-9. Epub 2005 Dec 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cowie L, Morgan M, White P, Gulliford M.. Experience of continuity of care of patients with multiple long-term conditions in England. J Heal Serv Res Policy 2009;14(2):82-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Detz A, López A, Sarkar U.. Long-term doctor-patient relationships: patient perspective from online reviews. J Med Internet Res 2013;15(7):e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frederiksen HB, Kragstrup J, Dehlholm-Lambertsen G.. It’s all about recognition! Qualitative study of the value of interpersonal continuity in general practice. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frederiksen HB, Kragstrup J, Dehlholm-Lambertsen B.. Attachment in the doctor-patient relationship in general practice: a qualitative study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2010;28(3):185-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabel LL, Lucas JB, Westbury RC.. Why do patients continue to see the same physician? Fam Pract Res J 1993;13(2):133-47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Den Herder-van der Eerden M, Hasselaar J, Payne S, Varey S, Schwabe S, Radbruch L, et al. How continuity of care is experienced within the context of integrated palliative care: a qualitative study with patients and family caregivers in five European countries. Palliat Med 2017;31(10):946-55. Epub 2017 Mar 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liaw ST, Litt J, Radford A.. Patient perceptions of continuity of care: is there a socioeconomic factor. Fam Pract 1992;9(1):9-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michiels E, Deschepper R, Van Der Kelen G, Bernheim JL, Mortier F, Vander Stichele R, et al. The role of general practitioners in continuity of care at the end of life: a qualitative study of terminally ill patients and their next of kin. Palliat Med 2007;21(5):409-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naithani S, Gulliford M, Morgan M.. Patients’ perceptions and experiences of ‘continuity of care’ in diabetes. Heal Expect 2006;9(2):118-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandhi N, Bowers B, Chen FP.. A comfortable relationship: a patient-derived dimension of ongoing care. Fam Med 2007;39(4):266-73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhodes P, Sanders C, Campbell S.. Relationship continuity: when and why do primary care patients think it is safer? Br J Gen Pract 2014;64(629):e758-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tarrant C, Dixon-Woods M, Colman AM, Stokes T.. Continuity and trust in primary care: a qualitative study informed by game theory. Ann Fam Med 2010;8(5):440-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tarrant C, Windridge K, Baker R, Freeman G, Boulton M.. ‘Falling through gaps’: primary care patients’ accounts of breakdowns in experienced continuity of care. Fam Pract 2015;32(1):82-7. Epub 2014 Nov 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alazri MH, Heywood P, Neal RD, Leese B.. UK GPs’ and practice nurses’ views of continuity of care for patients with type 2 diabetes. Fam Pract 2007;24(2):128-37. Epub 2007 Feb 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delva D, Kerr J, Schultz K.. Continuity of care. Differing conceptions and values. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:915-21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ridd M, Shaw A, Salisbury C.. ‘Two sides of the coin’—the value of personal continuity to GPs: a qualitative interview study. Fam Pract 2006;23(4):461-8. Epub 2006 Apr 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schultz K, Delva D, Kerr J.. Emotional effects of continuity of care on family physicians and the therapeutic relationship. Can Fam Physician 2012;58:178-85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sturmberg JP. Continuity of care: towards a definition based on experiences of practising GPs. Fam Pract 2000;17(1):16-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guthrie B, Wyke S.. Personal continuity and access in UK general practice: a qualitative study of general practitioners’ and patients’ perceptions of when and how they matter. BMC Fam Pract 2006;7:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collins A. Measuring what really matters. Towards a coherent measurement system to support person-centred care. London, UK: The Health Foundation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Person-centred care made simple. What everyone should know about person-centred care. London, UK: The Health Foundation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pandhi N, Saultz JW.. Patients’ perceptions of interpersonal continuity of care. J Am Board Fam Med 2006;19(4):390-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersen RS, Vedsted P, Olesen F, Bro F, Søndergaard J.. Does the organizational structure of health care systems influence care-seeking decisions? A qualitative analysis of Danish cancer patients’ reflections on care-seeking. Scand J Prim Health Care 2011;29(3):144-9. Epub 2011 Aug 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vedsted P, Olesen F.. Are the serious problems in cancer survival partly rooted in gatekeeper principles? An ecologic study. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61(589):e508-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carson-Stevens A, Hibbert P, Williams H, Evans HP, Cooper A, Rees P, et al. Characterising the nature of primary care patient safety incident reports in the England and Wales National Reporting and Learning System: a mixed-methods agenda-setting study for general practice. Heal Serv Deliv Res 2016;4:1-76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T.. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18(8):646-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perlo J, Balik B, Swensen S, Kabcenell A, Landsman J, Feeley D.. IHI framework for improving joy in work. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Continuity and coordination of care: a practice brief to support implementation of the WHO Framework on integrated people-centred health services. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 52.A new vision for Canada. Family practice—the Patient’s Medical Home. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.