Abstract

Objective

To examine the perceptions of family medicine (FM) residents about their chosen specialty and how they perceive that patients, other specialists, and the government value FM.

Design

Self-report data from the Family Medicine Longitudinal Survey collected from 2014 (time 1 [T1]) to 2016 (time 2 [T2]).

Setting

Canada.

Participants

Family medicine residents from 16 out of the 17 FM residency programs.

Main outcome measures

Responses to statements in the survey were evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree). Data were analyzed in 2 ways: cross sectionally (participation in either T1 or T2), and longitudinally (participation in both T1 and T2).

Results

For both the cross-sectional cohorts (T1, n = 916; T2, n = 785) and the repeated-measures cohort (n = 420), most residents responded positively to feeling proud of becoming a family physician, with little change from entrance to exit. For both cohorts, a higher proportion of residents at the end of training reported that other medical specialists value the contributions of family physicians (P < .001); however, fewer believed that the government perceived FM as essential to the health care system (P < .001).

Conclusion

Most participating Canadian FM residents feel proud to become family physicians. This feeling may come from the perceptions of others who are believed to value FM, including other specialists. Measuring attitudinal perceptions offers a window to discover how FM is viewed and can offer a way to measure the effect of strategies implemented to advance the discipline of FM.

Résumé

Objectif

Examiner les perceptions des résidents en médecine familiale (MF) à propos de la spécialité qu’ils ont choisie, et de la façon dont les patients, les autres spécialistes et le gouvernement valorisent la MF.

Type d’étude

Données signalées par les répondants dans le Sondage longitudinal en médecine familiale, qui ont été recueillies de 2014 (premier [T1] à 2016 (deuxième [T2]).

Contexte

Canada.

Participants

Des résidents en médecine familiale de 16 des 17 programmes de résidence en MF.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

Les réponses à des énoncés dans le sondage ont été évaluées sur une échelle de Likert en 5 points (de fortement en désaccord à fortement d’accord). Les données ont été analysées de 2 façons : transversalement (participation à T1 ou T2) et longitudinalement (participation à T1 et T 2).

Résultats

À la fois dans les 2 cohortes transversales (T1, n = 916; T2, n = 785) et dans la cohorte à mesures répétées (n = 420), la plupart des résidents ont répondu positivement au sentiment de fierté de devenir médecins de famille, avec peu de changements au départ et à la fin. Dans les 2 cohortes, une plus grande proportion des résidents à la fin de leur formation ont signalé que les autres spécialistes médicaux valorisaient les contributions des médecins de famille (p < ,001); toutefois, ils étaient moins nombreux à croire que le gouvernement percevait la MF comme une composante essentielle du système de santé (p < ,001).

Conclusion

La plupart des résidents canadiens en MF éprouvent de la fierté à devenir médecins de famille. Ce sentiment pourrait venir de la perception d’autres personnes dont on croit qu’elles valorisent la MF, notamment les autres spécialistes. La mesure des perceptions des attitudes offre une possibilité de découvrir comment est perçue la MF, de même qu’une façon de mesurer les effets de stratégies mises en œuvre pour faire avancer la discipline de la MF.

In 1978, the Declaration of Alma-Ata was issued at the International Conference on Primary Health Care, which drew attention to the urgent need for global health promotion and the prominent role of primary care professionals in supporting wellness and preventing illness in the communities they serve.1 Indeed, evidence suggests that family physicians contribute substantially to positive community health outcomes by preventing morbidity and mortality, and provide health care across various populations through community-based practices in an unbiased and equitable manner.2-7 However, despite awareness of the essential role of family medicine (FM) in health promotion, FM as a discipline does not always receive positive recognition and is often perceived as a less prestigious or desirable practice specialty.8-13

Negative perceptions of FM pervade all levels of learners (ie, medical students, residents, fellows, and faculty) and include views such as the following: FM is not a prestigious specialty and lacks academic opportunities and innovation technology,12-14 and is a “worst-case scenario” backup plan.13 In a recent widely publicized survey of more than 3500 medical students in the United Kingdom, most (76%) reported experiencing negative comments toward FM during training, and perceived peers as having negative attitudes toward FM (91%)—findings that are corroborated in other recent studies.15-19 Other evidence suggests that a dynamic exists in medicine that facilitates the continued reinforcement of a hierarchy where FM is inferior to other disciplines,17 specifically that family physicians are not competent and their role is not a foundational component of the health care system.20 These negative perceptions of FM may influence future career choices of students, compounded by biases against primary care that may exist in medical schools and postgraduate training placements.21

Several initiatives have been implemented over the years to address biases toward FM. Of note is the release of 2 reports from the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada, which highlighted the need for medical schools to address the negative impact of the “hidden curriculum”—particularly the effect of devaluing generalism.22 The hidden curriculum represents informal learning that takes place outside of the formal medical curriculum17 and is suspected to be a major factor in the reduced interest in, and perceived value of, FM among medical learners. Medicine’s hidden curriculum revolves around an organizational culture that often favours other medical specialties, devaluing the importance of generalist skills that are embedded in FM.17,23,24 More recently, the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC), in partnership with the Canadian federal government, developed and implemented a strategy to strengthen the foundation of FM, including FM interest groups in medical schools that are focused on promoting a positive perception of FM among medical students, developing awareness of the unique skill set and importance of family physicians in overall community health, and fostering a positive collegial environment across all specialties.10-12

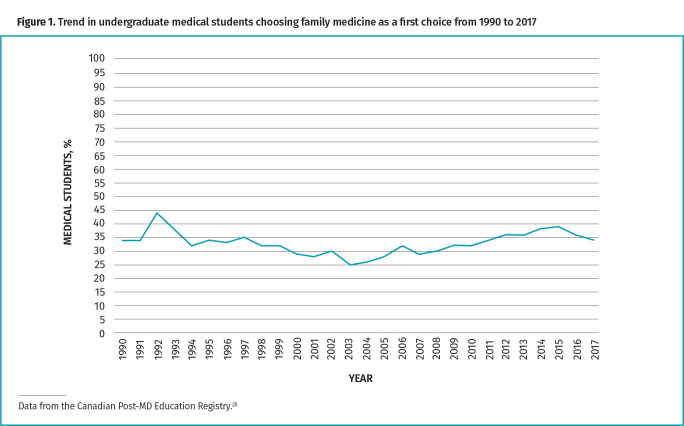

Despite these initiatives, interest in FM as a specialty choice has fluctuated throughout the past 2 decades. Figure 125 illustrates a peak in FM as a career choice in 1992 and this coincides with the shift away from generalist internships to selection of FM or another specialty.26 From 1992 to 2003 a decrease in interest in FM as a specialty choice by medical students is noted; however, increased interest is observed from 2003 to 2015, which coincides with advocacy efforts and strategic educational and practice initiatives in Canada (Figure 1).22,25.26 Despite more than 30% of all medical students choosing FM, the numbers still fall short of the call for up to 45% by the CFPC.27 Governments are feeling the pressure from the public regarding the lack of access to family physicians28-30: approximately 15% of Canadians are without a family physician.31-34 Furthermore, in rural and remote areas of Canada, timely access to appropriate care is even more challenging.30,31 This lack of access highlights the pressing need to enhance recruitment into the discipline, rather than just create more FM residency positions. Identifying the ways to improve the perception of, and interest in, FM as a first-choice specialty is imperative, since many residency positions in FM remain unfilled.26

Figure 1.

Trend in undergraduate medical students choosing family medicine as a first choice from 1990 to 2017

To inform initiatives aimed at increasing interest in FM, it is essential to explore the perceptions of FM residents toward the specialty they have chosen to practice, as well as whether those perceptions change over time during training. The objective of this study is to examine the perceptions held by learners in FM residency programs about the specialty of FM, measured at the beginning and at the end of residency training. This information could be useful to educators, program planners, and the government as they consider ways to increase interest in FM as a specialty of choice.

METHODS

Study design and data collection

As part of this quantitative observational study (one part of a larger mixed-methods study), the Family Medicine Longitudinal Survey (FMLS)—a Likert scale–based survey tool developed by the CFPC—was administered to FM residents in training programs across Canada upon entry to residency and again at the end of residency. The FMLS captures information from residents about their learning experiences during FM training, their perceived readiness for unsupervised practice, and their practice intentions. Results were captured with the FMLS on questions asking specifically about residents’ own perceptions of FM, as well as their perceptions on how others value FM (Table 1).

Table 1.

Questions from the FMLS capturing perceptions of FM residents about their specialty using a 5-point Likert scale

| QUESTION NO. | PERCEPTION |

|---|---|

| 13a | Proud to become a family physician |

| 13b | Patients recognize value of FM |

| 13c | Patients believe family physicians provide value beyond referrals |

| 13d | Find other medical specialists have little respect for expertise of family physicians |

| 13e | Family physicians provide valuable contribution that is different from other specialists |

| 13f | Would prefer to be in another medical specialty |

| 13g | Government perceives FM as essential to health care system |

FM—family medicine, FMLS—Family Medicine Longitudinal Survey.

Information was provided to participants regarding the purpose of the survey, the procedures, and the benefits and risks of voluntary participation. Continuing with the survey and providing responses to the FMLS was deemed to be implied consent. In addition, residents were provided with written confirmation of confidentiality and anonymity of responses, which was located at the beginning of the survey. Surveys were available in both paper and online format.

This research was approved by the research ethics board at each of the 16 participating institutions.

Participants

Family medicine residents from 16 out of 17 programs across Canada were invited to participate in the survey.

Procedures

Residency programs had a 3-month window at residency start (time 1 [T1]: 2014) and again at exit (time 2 [T2]: 2016) to make the survey available. Responses to statements in the survey were evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree). Data were analyzed in 2 ways: cross sectionally (participation in either T1 or T2) and longitudinally (participation in both T1 and T2).

Analyses

Cross-sectional data for each cohort were analyzed in aggregate. Repeated-measures data were matched between entry and exit surveys. A  2 analysis for cross-sectional data and a McNemar test for repeated-measures data were used to identify changes in frequencies. In addition, it was important to calculate the effect size to understand the magnitude of the observed changes, so a ϕ coefficient was the appropriate effect size calculation for

2 analysis for cross-sectional data and a McNemar test for repeated-measures data were used to identify changes in frequencies. In addition, it was important to calculate the effect size to understand the magnitude of the observed changes, so a ϕ coefficient was the appropriate effect size calculation for  2, and Cohen d as a function of the odds ratio (OR) (Cohen d = ln(OR)/1.81) for the McNemar test. However, the Cohen d could not be calculated for repeated-measures data because of a discordant value (0 in numerator or denominator) in the calculation of the OR. All statistical analyses were completed using the statistical software package R, version 3.3.2.

2, and Cohen d as a function of the odds ratio (OR) (Cohen d = ln(OR)/1.81) for the McNemar test. However, the Cohen d could not be calculated for repeated-measures data because of a discordant value (0 in numerator or denominator) in the calculation of the OR. All statistical analyses were completed using the statistical software package R, version 3.3.2.

RESULTS

Cross-sectional cohort

At the start of training in 2014 (T1), 916 out of 1353 (68%) residents participated in the FMLS; and 785 out of 1306 (60%) residents participated at the end of their training in 2016 (T2). Demographic characteristics for this cohort are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of FM residents participating in the FMLS cross-sectional cohort

| CHARACTERISTIC | FINDINGS |

|---|---|

| Age, y |

|

| Sex |

|

| Marital status |

|

| Have or expecting children |

|

| Settlement residence before attending university |

|

FM—family medicine, FMLS—Family Medicine Longitudinal Survey.

The threshold for statistical significance was set at P of less than .007. Results from 2014 indicate that for most of the positive statements relating to perceptions of FM, responses were highly in agreement at both the start and the end of residency (Table 3). The following significant differences between T1 and T2 were found: there was a 12% decrease in the percentage of residents perceiving that other medical specialists have little respect for the expertise of family physicians (P < .001), and there was a 34% decrease in the percentage of residents reporting that the government values FM as essential to the health care system (P < .001). While not statistically significant, a decrease was also noted in the perception that patients recognize the value of FM.

Table 3.

Cross-sectional cohort (T1 [2014] vs T2 [2016]) differences in frequency, corresponding significance level, and magnitude of effect for changes in perceptions about family medicine: Results include responses of agree and strongly agree.

| FMLS QUESTION | T1 (N = 916), n (%) | T2 (N = 785), n (%) | P VALUE | EFFECT SIZE, ϕ* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proud to become a family physician (13a) | 850 (92.8) | 729 (92.9) | > .99 | NA |

| Patients recognize value of family medicine (13b) | 777 (84.8) | 643 (81.9) | .12 | NA |

| Patients believe family physicians provide value beyond referrals (13c) | 665 (72.6) | 614 (78.2) | .009 | NA |

| Find other medical specialists have little respect for expertise of family physicians (13d) | 337 (36.8) | 194 (24.7) | 1.12 × 10–7† | 0.13 |

| Family physicians provide a valuable contribution that is different from other specialists (13e) | 876 (95.6) | 759 (96.7) | .32 | NA |

| Would prefer to be in another medical specialty (13f) | 46 (5.1) | 57 (7.3) | .07 | NA |

| Government perceives family medicine as essential to health care system (13g) | 711 (77.6) | 344 (43.8) | < 2.2 × 10–16t | 0.35 |

FMLS—Family Medicine Longitudinal Survey, NA—not applicable, T1—time 1, T2—time 2.

ϕ magnitude of effect: small is from 0.10 to 0.29; medium is from 0.30 to 0.49; and large is 0.50 or greater.

Statistical significance is set at P < .007 after application of the Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons; in these cases, P < .001.

Repeated-measures cohort

In 16 out of 17 programs, 420 out of 1353 (31%) incoming residents participated in the FMLS at both the start of their training in 2014 (T1) and the end of training in 2016 (T2). Demographic characteristics for this cohort are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Demographic characteristics of FM residents participating in the FMLS repeated-measures cohort

| CHARACTERISTIC | INDINGS |

|---|---|

| Age, y |

|

| Sex |

|

| Marital status |

|

| Have or expecting children |

|

| Settlement residence before attending university |

|

FM—family medicine, FMLS—Family Medicine Longitudinal Survey.

The threshold for statistical significance was set at P of less than .007. In this repeated-measures cohort, a large proportion of residents reported feeling proud to become a family physician and that family physicians provide a valuable contribution to health care that is different from other specialists (Table 5). Statistically significant results for this cohort are as follows: there was a decrease in the proportion of FM residents perceiving little respect for their expertise from other medical specialists (P < .001); there was an increase in the proportion of residents reporting that family physicians provide a valuable contribution beyond providing referrals to other specialists (P = .003); there was a decrease in the proportion of residents reporting that they perceive that patients recognize the value of FM (P < .001); and there was a decrease in perceived governmental support for FM as essential to the health care system (P < .001). Furthermore, while there was an increase in the proportion of residents who reported that they would prefer to be in another medical specialty, this change is not statistically significant.

Table 5.

Repeated-measures cohort (T1 [2014] vs T2 [2016]) differences in frequency, corresponding significance level, and magnitude of effect for changes in perceptions about family medicine: Results include responses of agree and strongly agree.

| FMLS QUESTION | T1 (N = 420), n (%) | T2 (N = 420), n (%) | P VALUE | EFFECT SIZE, COHEN d* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proud to become family physician (13a) | 398 (94.8) | 394 (93.8) | .13 | NA |

| Patients recognize value of family medicine (13b) | 369 (87.9) | 350 (83.3) | 3.64 × 10–5† | NA |

| Patients believe family physicians provide value beyond referrals (13c) | 319 (76.0) | 334 (79.5) | .003‡ | NA |

| Find other medical specialists have little respect for expertise of family physicians (13d) | 136 (32.4) | 94 (22.4) | 2.51 × 10–10† | NA |

| Family physicians provide valuable contribution that is different from other specialists (13e) | 412 (98.1) | 408 (97.1) | .13 | NA |

| Would prefer to be in another medical specialty (13f) | 20 (4.8) | 29 (6.9) | .008 | NA |

| Government perceives family medicine as essential to health care system (13g) | 336 (80.0) | 185 (44.0) | < 2.2 × 10–16† | NA |

FMLS—Family Medicine Longitudinal Survey, NA—not applicable, T1—time 1, T2—time 2.

Cohen d magnitude of effect: small is from 0.10 to 0.29; medium is from 0.30 to 0.49; and large is 0.50 or greater. However, odds ratios cannot be calculated because one of the discordant values in the McNemar test is 0; therefore, Cohen d cannot be calculated for this cohort.

Statistical significance is set at P < .007 after application of the Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons; in this case, P < .001.

Statistical significance is set at P < .007 after application of the Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons; in this case, P <.01.

DISCUSSION

These results provide a snapshot of Canadian learner perceptions about FM and their perceptions of how others, such as colleagues, patients, and the government, value the discipline of FM. This is the first longitudinal examination of perceptions of FM residents—from the beginning of residency training to completion—to the best of our knowledge. The reported perceptions at residency entrance are likely a reflection of experiences in medical school, and thus are reflective of medical school culture across Canada and the hidden curriculum that learners may be exposed to related to the discipline of FM.17,22-24 At exit, perceptions are more likely to be a reflection of residency training experiences.

There are 3 key findings from this study. The first is consistent pride in becoming a family physician. The pride reported by FM residents for their chosen career is a reassuring finding. Evidence suggests that medical specialty selection requires alignment between perceived characteristics of a specialty and personal career needs, which supports the development of an FM identity and positive external view of FM.35,36 Family medicine residents’ unwavering pride may be an indication of the alignment of what they hoped the specialty would be and what they actually experienced during their training.

Second, contrary to recently publicized reports related to negative attitudes toward FM, our findings highlight the perception by residents that other specialists value the contribution of family physicians. Perhaps the efforts undertaken by the CFPC and the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada have had a positive influence on changing the hidden curriculum during medical school. Family medicine residents in this survey leave residency with a strengthened perception of positive views by other specialties as to the contributions of FM. This result is a positive outcome, particularly in light of previously published research, which suggests that professional relationships between family physicians and other specialists can be conflictual.37 If these conflicts are filtered down to the trainee level, it could influence medical students’ or trainees’ decisions to choose a career in general practice.38 It could also influence how they might negatively perceive themselves for choosing FM.39 Values about a career are often shaped by medical school experiences and by the values and culture of the institution in which the student receives medical training.35

Third, residents’ perception that the government values FM as an essential part of the health care system and that patients recognize the value of family physicians decreased by the end of residency. The significant decrease over time in FM residents’ perception that the government values FM as an essential part of the health care system is a finding that must be investigated further. When family physicians do not feel supported and learners witness their preceptors challenged in the workplace, their perceptions of the discipline may be negatively influenced. In addition, income disparities between family physicians and other specialists17,40 over the years have been a challenge, with pay differentials between FM and other specialties frequently cited as a reason why medical school graduates do not choose FM.40-43 Evidence suggests that strong leadership and government support are critical ingredients needed for health care reform and transformation of primary care practices.44,45 Provincial governments in Canada set policies related to physician remuneration and practice models. Family medicine graduates entering practice who experience government policies first-hand may have their beliefs reinforced after residency, and this may create a ripple effect that negatively impacts career choice in FM in the future. There is a distinct possibility that medical school students could be influenced to avoid a specialty where the government (who holds the purse strings and sets policy) is perceived as not supporting FM. A potential decrease in interest in FM in Canada may follow similar declines reported in other countries,26,46-49 creating major concerns about the future health and wellness of communities.

It is worth noting the significant decrease in FM residents’ perceptions that patients recognize the value of family physicians. This significant decrease was seen only in the repeated-measures cohort, but is potentially a finding worth further exploration. If this perception by residents is consistent in future survey findings, it may mean that negative perceptions about FM stemming from the hidden curriculum are upheld outside of academic institutions and in the general community. If so, this may perpetuate the false dichotomy of prestige and respect between FM and other medical specialties.

Limitations

The research undertaken has limitations. The findings presented are based on self-report, with no objective measure to triangulate or to confirm them. However, while we acknowledge the limitations associated with self-report, in this study we see this method of data collection to be a strength, since there is no other way of capturing intrapsychic concepts about a topic, such as perceptions, other than through subjective reporting. An additional limitation is that we are unable to attribute the observed changes to specific factors, such as curriculum reform detailed in the introduction, since this study did not incorporate a control group and randomization. The results from the repeated-measures cohort are based on a 31% response rate, and this is another limitation of this study. In keeping with confidentiality agreements with each of the 16 residency programs across Canada, we have disseminated results in aggregate only. Finally, incorporating focus groups or interviews with residents participating in the survey may have provided more in-depth understanding of responses and captured more information. It is a planned activity in future examinations to include the perceptions of FM residents about their specialty.

Conclusion

Many FM residents entering and exiting residency training in Canada do so with pride. The findings presented here from a pan-Canadian cohort of residents who experienced training from 2014 to 2016 indicate that, during the course of training, FM residents generally have positive perceptions about becoming a family physician. While these findings differ from other publications cited in this article that indicate a more negative view of FM, these recent Canadian findings are reassuring. While we have posed questions and evidence-based interpretations in response to data captured by the FMLS, the current results provide a starting point for further examination of factors influencing FM as a career choice.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the College of Family Physicians of Canada and the 17 university-based family medicine residency programs who have partnered to evaluate the Triple C Competency-based Curriculum that provided the survey data used in this publication.

Editor’s key points

▸ Although family medicine (FM) is an essential part of the health care system, it is often perceived as a less desirable medical specialty. Negative perceptions of FM could influence medical students’ decisions, leading to fewer students selecting FM as a career.

▸ At the end of residency, residents generally had positive perceptions about FM. Many had pride in becoming a family physician and found other specialists seemed to value and respect the expertise of family physicians.

▸ However, by the end of residency, fewer residents held the perception that the government valued FM as part of the health care system and that patients recognized the value of FM.

Points de repère du rédacteur

▸ Même si la médecine familiale (MF) est une composante essentielle du système de santé, elle est souvent perçue comme une spécialité médicale moins attrayante. Les perceptions négatives de la MF pourraient influer sur les décisions des étudiants en médecine et faire en sorte qu’un moins grand nombre d’entre eux choisissent la MF comme carrière.

▸ À la fin de la résidence, les résidents avaient généralement des perceptions positives de la MF. Plusieurs se sentaient fiers de devenir médecins de famille, et ils trouvaient que les autres spécialistes semblaient valoriser et respecter l’expertise des médecins de famille.

▸ Par ailleurs, à la fin de leur résidence, un moins grand nombre de résidents avaient l’impression que le gouvernement valorisait la MF comme composante du système de santé et que les patients reconnaissaient la valeur de la MF.

Footnotes

Contributors

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

References

- 1.WHO called to return to the Declaration of Alma-Ata. International conference on primary health care. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J.. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q 2005;83(3):457-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishikawa H, Yano E.. Patient health literacy and participation in the health-care process. Health Expect 2008;11(2):113-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vuori IM, Lavie CJ, Blair SN.. Physical activity promotion in the health care system. Mayo Clin Proc 2013;88(12):1446-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starfield B, Hyde J, Gérvas J, Heath I.. The concept of prevention: a good idea gone astray? J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62(7):580-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peerson A, Saunders M.. Health literacy revisited: what do we mean and why does it matter? Health Promot Int 2009;24(3):285-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health promotion. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keegan DA, Scott I, Sylvester M, Tan A, Horrey K, Weston WW.. Shared Canadian Curriculum in Family Medicine (SHARC-FM). Creating a national consensus on relevant and practical training for medical students. Can Fam Physician 2017;63:e223-31. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/content/63/4/e223.long. Accessed 2021 Aug 18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohan-Minjares F, Alfero C, Kaufman A.. How medical schools can encourage students’ interest in family medicine. Acad Med 2015;90(5):553-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woloschuk W, Wright B, McLaughlin K.. Debiasing the hidden curriculum. Academic equality among medical specialties. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:e26-30. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/content/57/1/e26.long. Accessed 2021 Aug 18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bethune C, Hansen PA, Deacon D, Hurley K, Kirby A, Godwin M.. Family medicine as a career option. How students’ attitudes changed during medical school. Can Fam Physician 2007;53:880-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osborn HA, Glicksman JT, Brandt MG, Doyle PC, Fung K.. Primary care specialty career choice among Canadian medical students. Understanding the factors that influence their decisions. Can Fam Physician 2017;63:e107-13. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/content/63/2/e107.long. Accessed 2021 Aug 18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodríguez C, López-Roig S, Pawlikowska T, Schweyer FX, Bélanger E, Pastor-Mira MA, et al. The influence of academic discourses on medical students’ identification with the discipline of family medicine. Acad Med 2015;90(5):660-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naimer S, Press Y, Weissman C, Zisk-Rony RY, Weiss YG, Tandeter H.. Medical students’ perceptions of a career in family medicine. Isr J Health Policy Res 2018;7(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collier R. Disrespect within medicine for family doctors affects medical students and patients. CMAJ 2018;190(4):E121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips SP, Clarke M.. More than an education: the hidden curriculum, professional attitudes and career choice. Med Educ 2012;46(9):887-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doja A, Bould MD, Clarkin C, Eady K, Sutherland S, Writer H.. The hidden and informal curriculum across the continuum of training: a cross-sectional qualitative study. Med Teach 2016;38(4):410-8. Epub 2015 Aug 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oser TK, Haidet P, Lewis PR, Mauger DT, Gingrich DL, Leong SL.. Frequency and negative impact of medical student mistreatment based on specialty choice: a longitudinal study. Acad Med 2014;89(5):755-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barber S, Brettell R, Perera-Salazar R, Greenhalgh T, Harrington R.. UK medical students’ attitudes towards their future careers and general practice: a cross-sectional survey and qualitative analysis of an Oxford cohort. BMC Med Educ 2018;18(1):160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips J, Charnley I.. Third- and fourth-year medical students’ changing views of family medicine. Fam Med 2016;48(1):54-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholson S, Hastings AM, McKinley RK.. Influences on students’ career decisions concerning general practice: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66(651):e768-75. Epub 2016 Aug 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The future of medical education in Canada (FMEC): a collective vision for MD education. Ottawa, ON: The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martimianakis MA, Michalec B, Lam J, Cartmill C, Taylor JS, Hafferty FW.. Humanism, the hidden curriculum, and educational reform: a scoping review and thematic analysis. Acad Med 2015;90(11 Suppl):S5-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandini J, Mitchell C, Epstein-Peterson ZD, Amobi A, Cahill J, Peteet J, et al. Student and faculty reflections of the hidden curriculum. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017;34(1):57-63. Epub 2016 Jul 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annual census. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Post-MD Education Registry; 2021. Available from: https://caper.ca/postgraduate-medical-education/annual-census. Accessed 2021 Aug 16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.R-1 match interactive data. National data on CMG applicants and quota in the R-1 match by disciplines (first iteration only). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Supporting the future family medicine workforce in Canada. Is enough being done today to prepare for tomorrow? Report card. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brend Y. We’re graduating more doctors than ever, so why is it so hard to find a GP? CBC News 2017. May 4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gandhi S. More bad news for family medicine and patients. Huffington Post 2018. Jan 10. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Globerman S, Barua B, Hasan S.. The supply of physicians in Canada: projections and assessment. Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.2015-2016 annual census of post-MD trainees. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Post-MD Education Registry; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.2016-2017 annual census of post-MD trainees. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Post-MD Education Registry; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muggah E, Hogg W, Dahrouge S, Russell G, Kristjansson E, Muldoon L, et al. Patient-reported access to primary care in Ontario. Effect of organizational characteristics. Can Fam Physician 2014;60:e24-31. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/content/60/1/e24. Accessed 2021 Aug 18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clarke J. Health at a glance: difficulty accessing health care services in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bland CJ, Meurer LN, Maldonado G.. Determinants of primary care specialty choice: a non-statistical meta-analysis of the literature. Acad Med 1995;70(7):620-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woloschuk W, Myhre D, Dickinson J, Ross S.. Implications of not matching to a first-choice discipline: a family medicine perspective. Can Med Educ J 2017;8(3):e30-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall MN. Qualitative study of educational interaction between general practitioners and specialists. BMJ 1998;316(7129):442-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamien BA, Bassiri M, Kamien M.. Doctors badmouthing each other. Does it affect medical students’ career choices? Aust Fam Physician 1999;28(6):576-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Natanzon I, Ose D, Szecsenyi J, Campbell S, Roos M, Joos S.. Does GPs’ self-perception of their professional role correspond to their social self-image?—a qualitative study from Germany. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morra DJ, Regehr G, Ginsburg S.. Medical students, money, and career selection: students’ perception of financial factors and remuneration in family medicine. Fam Med 2009;41(2):105-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Kutob R.. Factors related to the choice of family medicine: a reassessment and literature review. J Am Board Fam Pract 2003;16(6):502-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phillips JP, Weismantel DP, Gold KJ, Schwenk TL.. Medical student debt and primary care specialty intentions. Fam Med 2010;42(9):616-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grayson MS, Newton DA, Thompson LF.. Payback time: the associations of debt and income with medical student career choice. Med Educ 2012;46(10):983-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hutchison B, Levesque JF, Strumpf E, Coyle N.. Primary health care in Canada: systems in motion. Milbank Q 2011;89(2):256-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malko AV, Huckfeldt V.. Physician shortage in Canada: a review of contributing factors. Glob J Health Sci 2017;9(9):68-80. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lahad A, Bazemore A, Petek D, Phillips WR, Merenstein D.. How can we change medical students’ perceptions of a career in family medicine? Marketing or substance? Isr J Health Policy Res 2018;7(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weidner A, Davis A.. Influencing medical student choice of primary care worldwide: international application of the four pillars for primary care physician workforce. Isr J Health Policy Res 2018;7(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xierali IM. Distributional differences between family physicians and general internists. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2018;29(2):711-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singleton T, Miller P.. Evaluating physician employment contracts: how do your benefits measure up? Fam Pract Manag 2017;24(5):9-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]