Abstract

Objectives

Latinos are the fastest aging racial/ethnic minority group in the United States. One limitation to understanding the diverse experiences of older Latinos is the lack of nationally representative data necessary to examine factors contributing to changes in population-level health over time. This is needed to provide a more comprehensive picture of the demographic characteristics that influence the health and well-being of older Latinos.

Methods

We utilized the steady-state design of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) from 1992 to 2016 to examine the demographic and health characteristics of five entry birth cohorts of older Latinos aged 51–56 years (n = 2,882). Adjusted Wald tests were used to assess statistically significant differences in demographic and health characteristics across the HRS birth cohorts.

Results

Cross-cohort comparisons of demographic and health characteristics of older Latinos indicate significant change over time, with later-born HRS birth cohorts less likely to identify as Mexican-origin, more likely to identify as a racial “other,” and more likely to be foreign-born. In addition, we find that later-born cohorts are more educated and exhibit a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity.

Discussion

Increasing growth and diversity among the older U.S. Latino population make it imperative that researchers document changes in the demographic composition and health characteristics of this population as it will have implications for researchers, policymakers, health care professionals, and others seeking to anticipate the needs of this rapidly aging population.

Keywords: Diversity in aging, Health disparities, Minority aging, (race/ethnicity), Population aging

The U.S. population aged 65 and older is projected to double between 2016 and 2060 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018a). Population estimates suggest that Latinos will contribute significantly to the growth of the older adult population in the United States, with the share of older U.S. Latinos expected to increase from 8% to 21% over the coming decades (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018b), making Latinos the fastest aging minority group. These trends suggest that the demographic and health profiles of aging U.S. adults will increasingly reflect that of the rapidly growing and aging Latino population (Hummer & Hayward, 2015). This is of particular concern as emerging research shows that older Latinos have experienced significant increases in the prevalence of debilitating chronic conditions (Aguayo-Mazzucato et al., 2019; C. Garcia et al., 2018; Quiñones et al., 2019), disability (Garcia et al., 2017, 2020), and cognitive impairment (Garcia et al., 2021; González et al., 2019), which has contributed to a higher burden of older adult years spent living with these conditions. However, it remains unclear whether these trends are a result of changes in the demographic composition of the Latino population or period exposure to structural and social factors that shape health across the life course (Elder et al., 2003).

Currently, four U.S. population-based longitudinal studies have focused exclusively on the health and well-being of older Latinos: (a) the Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly, an ongoing longitudinal cohort study of Mexican Americans aged 65 and older residing in the Southwestern United States that began in 1993–1994; (b) the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging, a longitudinal cohort study of Latinos aged 60 and older in Sacramento County, California conducted between 1996 and 2008; (c) the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, an ongoing longitudinal study of 1,500 Puerto Ricans aged 45–75 years, recruited from the Greater Boston area in Massachusetts that began in 2004; and (d) the Puerto Rican Elderly Health Conditions Project, a longitudinal study of island Puerto Ricans aged 60 and older that began in 2002.

The primary aim of these surveys is to provide information on demographic, physical health, psychosocial characteristics, and health care needs of community-dwelling older Latinos. The longitudinal nature of these data sets has been beneficial for evaluating health trends among different subgroups of older Latinos across various contextual settings (e.g., Southwestern United States, Puerto Rico). Despite the important insights drawn from this research, the literature on older Latinos has notable gaps that limit our understanding of the health and well-being of this population. Specifically, none of the above studies are nationally representative of older Latinos and primarily follow a group of similarly aged respondents (i.e., single cohorts) over time. This limits our ability to understand trends in demographic and health characteristics across decades and different birth cohorts in the broader U.S. Latino population. Moreover, with the Latino population becoming more demographically diverse, nationally representative data are necessary to address questions regarding factors contributing to changes in population-level health in the United States over time.

For example, the proportion of foreign-born Latinos in the United States has increased from 13.8% in 1960 to 34.4% in 2015 (Flores, 2017a). Large increases in migration streams from Central America and the Caribbean (Flores, 2017b), coupled with significant declines in the proportion of foreign-born Mexicans residing in the United States over the same period (Flores, 2017a), have contributed to growing ethnic origin diversity within this population. In addition, educational attainment, an important indicator of population health and well-being, has steadily increased, with the proportion of Latinos aged 25 and older earning a bachelor’s degree nearly doubling from 7.7% in 1980 to 15.0% in 2015 (Flores et al., 2017). Recent evidence also shows a significant increase in the educational levels of foreign-born immigrants to the United States, with approximately 26% of Latino immigrants reporting having obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher in 2018 compared to 10% of Latino immigrants in 1990 (Noe-Bustamante, 2020).

Finally, prior research has documented emerging changes in the geographic distribution of U.S. Latinos over the past several decades. Although Latinos have historically been concentrated in California, Texas, and Florida, there have been substantial population increases in states such as Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Virginia (Krogstad, 2020). These changes in geographic location have largely been driven by foreign-born Latinos migrating to New Destination areas. Moreover, the concentration of Latinos in specific geographic areas across the United States is associated with ethnic origin. For example, there are larger concentrations of Mexicans in the Southwest, Puerto Ricans in the Northeast, and Cubans in South Florida (García & Ailshire, 2019). The demographic changes noted above may be influenced by the exposure to certain social conditions and transformations in the social world (in and out of the United States) across the life span that may differentially impact resources and opportunity structures, which influence health in later life. We can advance existing research on older Latinos by documenting past and current demographic and health profiles of older Latinos to better address the needs of this rapidly aging population and to better inform the design of culturally relevant policies and programs.

A promising nationally representative longitudinal study to examine older Latinos is the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). A key feature of the HRS is the oversampling of Latinos, who have response rates at baseline and follow-up equal to or better than non-Latino Whites (Ofstedal & Weir, 2011). Notably, the oversampling of Latinos is higher in refresher samples due to a supplemental screening effort (HRS, 2011). To date, the HRS has collected and made publicly available 14 waves of biennial data between 1992 and 2018 on adults older than age 50 who were born between 1890 and 1967. This comprehensive data collection provides researchers the opportunity to examine the population profile—and changes in the demographic composition and health characteristics—of aging U.S. Latinos, a group that has been historically underrepresented in national studies of health. Documenting past and current demographic and health profiles of older Latino birth cohorts can further our understanding of this rapidly growing and diverse population by considering how changes in the demographic composition of the Latino population have contributed to the trends in the overall health of this population. Thus, we take advantage of the longitudinal design of the HRS to answer the following questions:

Has the demographic composition of older Latino cohorts changed over time?

Are there changes in health and health behaviors among older Latino cohorts?

This study has the potential to provide more granular demographic and health information that can unpack the diversity within the aging Latino population to enhance our ability to study and serve the changing needs of this rapidly aging population.

Method

Data

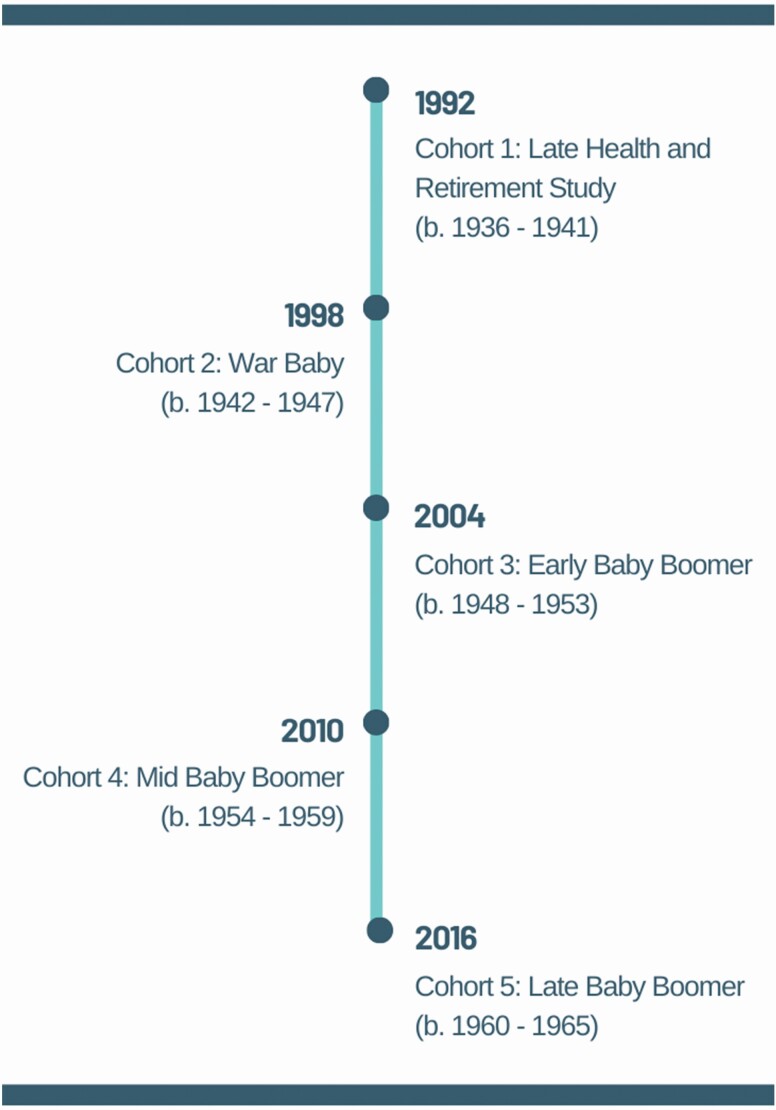

Data for this study come from the HRS, a nationally representative longitudinal survey of adults older than age 50 in the contiguous United States that is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan (Sonnega & Weir, 2014). The initial HRS cohort was recruited in 1992 and represented adults aged 51–61 years. Since 1998, the HRS has implemented a steady-state design, sampling a new cohort of individuals aged 51–56 every 6 years (e.g., 2004, 2010, and 2016) to “refresh” the sample and keep it representative of the population older than age 50. We utilize this design feature to compare cohorts of Latinos aged 51–56 years from 1992 to 2016. Figure 1 shows each birth cohort in the HRS and the baseline interview year in which they entered the survey at ages 51–56.

Figure 1.

The Health and Retirement Study’s steady-state design. Note: The original HRS cohort was based on an 11-year grouping (b. 1931–1941) and was divided into the Late HRS cohort that corresponds to the refresher cohorts in age (51–56) at baseline (i.e., first interview).

Apart from the War Baby cohort (born 1942–1947) added in 1998, the HRS has oversampled racial and ethnic minority respondents, including Latinos, to increase sample sizes needed for subgroup analyses, such as that conducted in the present study (Ofstedal & Weir, 2011). Moreover, HRS sample weights are designed to account for the oversampling of minority respondents and other factors associated with differential selection probability to ensure each HRS birth cohort is nationally representative of the older U.S. population. Response rates ranged from 81.0% to 90.7% across survey years (HRS, 2017), although response rates were slightly lower (66.2%–88.4%) for the minority oversample implemented between 2010 and 2016 (HRS, 2017). More detailed information on sample design and measurement validation is available elsewhere (Fisher & Ryan, 2018; Hauser, 2005; Juster & Suzman, 1995).

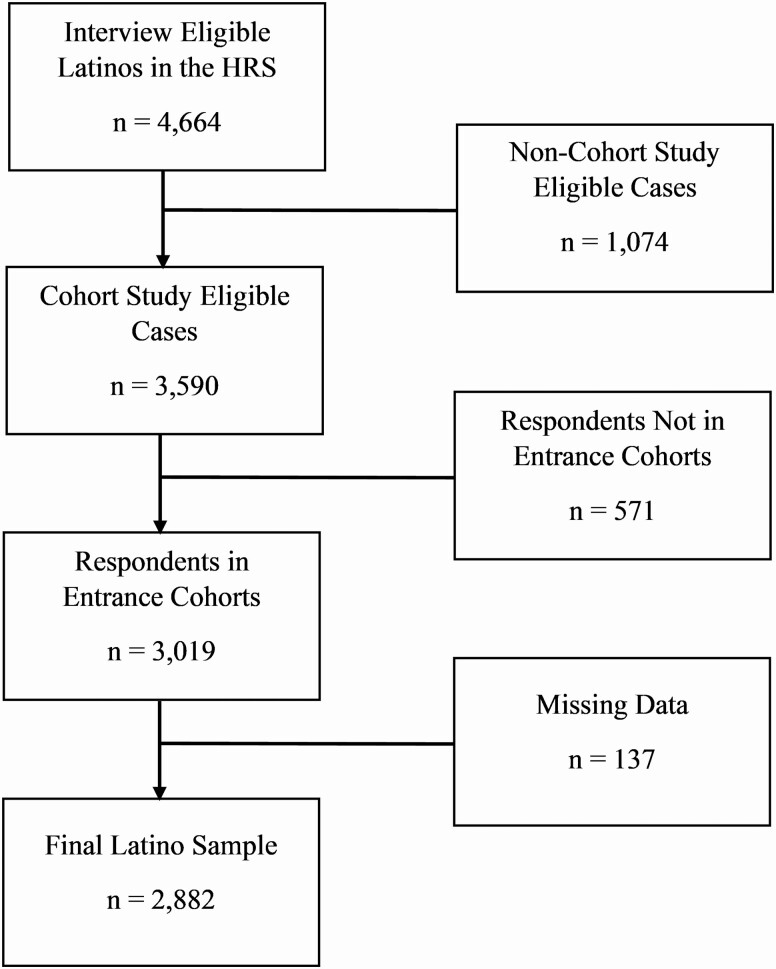

A detailed summary of selection criteria for the final analytic sample is presented in Figure 2. The final sample included respondents who self-identified as Hispanic or Latino, were cohort-eligible (i.e., aged 51–56 at baseline interview), and were not missing data on any covariates included in the analysis (n = 2,882).

Figure 2.

Health and Retirement Study (HRS) Latino sample selection, 1992–2016.

Measures

HRS birth cohorts

Cohorts were based on the respondents’ birth year that reflects the HRS steady-state design. The five HRS birth cohorts include (a) the Late HRS cohort (born 1936–1941), which represents part of the original HRS cohort that corresponds in age at baseline to the refresher cohorts; (b) War Babies (born 1942–1947); (c) Early Baby Boomers (born 1948–1953); (d) Mid Baby Boomers (born 1954–1959); and (e) Late Baby Boomers (born 1960–1965). Each defined HRS birth cohort included nationally representative respondents aged 51–56 years.

Demographic characteristics of older Latino birth cohorts

In order to contextualize the demographic composition of each cohort of Latinos, the following variables were included: sex, marital status, census region of residence, ethnic origin, racial identification, nativity status, language of interview, educational attainment, poverty, and household wealth. Sex was a dichotomous variable that included females and males. Marital status was coded categorically as married, separated, or divorced, widowed, and never married. Census region of residence was coded as Northeast, Midwest, South, West, and Other (not in a defined U.S. Census region).

Ethnic origin was based on the response to the following question, “Would you say you are Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban American, or something else?” Respondents were instructed to choose all the origins that applied to them. Although most respondents identified with one ethnic origin, some respondents identified with multiple ethnic origins. Respondents with multiple ethnic origins were classified based on their first response to maintain respondent confidentiality. The categories for ethnic origin for this study included Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and “other” Latinos (the origins of these “other” Latinos were not included with the HRS restricted data to protect respondent confidentiality). Information for ethnic origin was unavailable for the most recent cohort (i.e., Late Baby Boomers) at the time of the analysis.

Racial identification was based on the response to the question, “What race do you consider yourself to be: White, Black or African American, American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, or something else?” Respondents were instructed to choose all the races that they identified with. If more than one race was reported, respondents were asked which one they considered to be their primary race. Primary racial identification was used to classify respondents as White, Black, or “other” race.

Nativity status was self-reported by the respondent: (a) born in one of the 50 U.S. states (U.S.-born) or (b) born outside of the United States, including its territories (foreign-born). The interview language was determined by whether the respondent or proxy completed the survey in English or Spanish.

Educational attainment distinguished respondents with less than a high school education, high school education, and more than a high school education. Poverty was determined using the U.S. Census definition and poverty thresholds based on household income for the last calendar year. This measure of poverty excludes institutionalized household members, consistent with the Current Population Survey compatible definition of resident family members for determining the household composition and income (see RAND HRS Longitudinal File Documentation). Note, this measure became available beginning in 2002. Household wealth was a continuous variable that calculated the sum of all assets (excluding IRA’s and Keogh plans) minus debt. To accurately compare household wealth across HRS birth cohorts, total wealth was adjusted for inflation in 2020 dollars using the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index Research Series (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021).

Health and health behaviors

The following health and health behavior variables were included to further contextualize the demographic profiles of older Latino birth cohorts: chronic conditions, disability, obesity, smoking status, health insurance, and whether the respondent reported any doctor visit in the reference period. Respondents reported whether a doctor ever told them that they had any of the following six chronic conditions: hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, stroke, cancer (not including skin cancer), and lung disease (not including asthma). We created dichotomized variables for each chronic condition, indicating whether the respondent had the condition versus not having the condition. Activities of daily living (ADLs) were used to assess disability status (Smith et al., 1990). Respondents were asked if they had any difficulty performing the following tasks: bathing, eating, dressing, walking across a room, and getting in and out of bed. A dichotomized variable was created, indicating whether the respondent had any ADL disability versus no ADL disability.

Obesity was categorized as a measured body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or above. Smoking status was determined by whether the respondent reported they never smoked, were a former smoker, or were current smokers. Health insurance included two variables indicating whether the respondent had government-sponsored health insurance (e.g., Medicaid) and whether the respondent had private or employer-provided health insurance. These two health insurance indicators are not mutually exclusive. Finally, we include a dichotomized variable of whether the respondent reported any doctor visit. For respondents who were first interviewed in Wave 1 (i.e., 1992), the reference period for reporting any doctor visit is 12 months. In subsequent waves, the reference period for reporting any doctor visit is 2 years.

Analytic Strategy

Adjusted Wald tests were used to assess older Latino birth cohort differences across demographic and health characteristics. Statistical significance was assessed at α = 0.05. Stata’s survey prefix commands (svy) were used to account for the complex survey design of the HRS. For the current analysis, we use the sampling weights that correspond to each respondent’s first (baseline) interview. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp, 2019).

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Older Latino Birth Cohorts

Table 1 presents cross-cohort comparisons of demographic characteristics in five HRS birth cohorts of Latinos aged 51–56 years: the Late HRS, War Baby, Early Baby Boomer, Mid Baby Boomer, and Late Baby Boomer cohorts. Females comprised the majority of the sample across older Latino birth cohorts, reflecting the sex composition of older populations in which women live longer than their male counterparts. Over 60% of respondents reported being married, with the Early Baby Boomer cohort reporting the highest proportion of married individuals (72.8%). In contrast, the Late Baby Boomers had the highest proportion of individuals who were never married (14.1%). Although we observed considerable variability in the region of residence, older Latinos across HRS birth cohorts were more likely to live in the South (31.9%–45.4%) and West (35.1%–45.9%) Census regions, reflecting historical/traditional settlement patterns of Latino immigrants in states such as California and Texas. Overall, respondents in the War Baby and Early Baby Boomer cohorts were more likely to reside in the South, whereas the Mid Baby Boomer and Late Baby Boomer cohorts were more likely to live in the West.

Table 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Latino Population Aged 51–56 Over HRS Study Periods

| Cohort | Late HRS | War Baby | Early Baby Boomer | Mid Baby Boomer | Late Baby Boomer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth years | 1936–1941 | 1942–1947 | 1948–1953 | 1954–1959 | 1960–1965 | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age (mean) | 53.3 | 53.4 | 53.3 | 53.5 | 53.5 | |||||

| Female | 281 | 52.8 | 143 | 56.7 | 245 | 49.8 | 474 | 53.4 | 471 | 50.5 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Married | 368 | 69.7a | 179 | 68.4 | 305 | 72.8a,b | 556 | 63.5c | 507 | 62.0c,d |

| Separated/divorced | 86 | 19.2 | 37 | 22.8 | 97 | 17.7b | 196 | 23.9c | 202 | 20.9 |

| Widowed | 29 | 5.7b | 9 | 4.3 | 25 | 5.2 | 30 | 2.7d | 38 | 3.1 |

| Never married | 24 | 5.3a,b | 6 | 4.5a,b | 26 | 4.3a,b | 65 | 9.8c,d,e | 97 | 14.1c,d,e |

| Census region | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 62 | 13.8b | 26 | 13.3b | 63 | 12.1b | 104 | 7.7a,c,d,e | 142 | 13.0b |

| Midwest | 25 | 5.3 | 15 | 6.1 | 18 | 3.5a | 33 | 5.5 | 61 | 7.5c |

| South | 226 | 40.3a | 106 | 45.4a | 176 | 43.8a | 325 | 41.1a | 269 | 31.9b,c,d,e |

| West | 194 | 40.6 | 83 | 35.1a,b | 195 | 40.5 | 382 | 45.5e | 353 | 45.9e |

| Other | — | — | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.2 | 19 | 1.6 |

| Ethnic origin | ||||||||||

| Mexican | 320 | 62.3a | 158 | 65.0a | 297 | 66.8a | 478 | 61.6 | 440 | 55.9c,d,e |

| Puerto Rican | 41 | 8.3 | 15 | 8.4 | 51 | 10.8 | 86 | 8.6 | — | — |

| Cuban | 42 | 7.2b,c | 10 | 3.9 | 16 | 3.2 | 25 | 2.7d | — | — |

| Other Latino | 104 | 22.1 | 48 | 22.7 | 89 | 19.2 | 256 | 26.9 | — | — |

| Unknown | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 0.2 | — | — |

| Racial identification | ||||||||||

| White | 393 | 78.7a,b,c,e | 163 | 68.0a,b,c,d | 236 | 53.9a,d,e | 423 | 54.1a,d,e | 366 | 45.6b,c,d,e |

| Black | 12 | 2.0 | 7 | 4.5 | 6 | 1.2 | 15 | 1.3 | 30 | 2.3 |

| Other | 102 | 19.2a,b,c,e | 61 | 27.5a,b,c,d | 211 | 44.9d,e | 385 | 42.5d,e | 424 | 49.0d,e |

| Unknown | — | — | — | — | — | — | 24 | 2.2 | 24 | 3.1 |

| Foreign-born | 278 | 53.1a | 120 | 51.1a | 265 | 57.2 | 556 | 59.6 | 527 | 60.3d,e |

| Spanish interview | 227 | 43.1 | 103 | 39.1 | 213 | 41.7 | 452 | 44.7 | 399 | 44.4 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| <High school | 311 | 59.3a,b,c | 125 | 51.9a,b,c | 206 | 42.0a,d,e | 361 | 40.3a,d,e | 268 | 30.5b,c,d,e |

| High school | 107 | 21.6a,b | 42 | 18.9a,b | 109 | 26.3 | 223 | 27.3d,e | 264 | 30.1d,e |

| >High school | 89 | 19.1a,b,c,e | 64 | 29.3a,d | 138 | 31.8a,d | 263 | 32.4a,d | 312 | 39.4b,c,d,e |

| Below poverty threshold | — | — | — | — | 102 | 21.2 | 210 | 22.3 | 219 | 23.7 |

| Wealth in 2018$ (mean) | $114,385c | $139,149c | $234,098b,d,e | $142,950c | $295,063 | |||||

| N | 507 | 231 | 453 | 847 | 844 |

Notes: Unweighted Ns and weighted percentages. Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding; ethnic origin data other than Mexican origin were not available for Late Baby Boomers at the time of analysis. HRS = Health and Retirement Study.

aSignificantly different from Late Baby Boomers.

bSignificantly different from Mid Baby Boomers.

cSignificantly different from Early Baby Boomers.

dSignificantly different from Late HRS.

eSignificantly different from War Babies.

Additional demographic characteristics of Latinos that included ethnic origin, racial identification, nativity status, and language of interview showed significant variability across HRS birth cohorts. Although Mexican-origin respondents comprised the largest ethnic group across all birth cohorts, we observed a notable decrease in the proportion of respondents who identified as Mexican origin in the Late Baby Boomer cohort relative to prior cohorts. For example, 62.3% of respondents identified as Mexican origin in the Late HRS cohort compared to 55.9% of respondents who identified as Mexican origin in the Late Baby Boomer cohort—a 6.4 percentage point reduction. This decline reflects the growing demographic diversity within the aging Latino population as other ethnic origin groups have increased in population size over time. Notably, respondents who identified as “other” Latino experienced the largest increase in population size over time, from 22.1% in the Late HRS cohort to 27.1% in the Mid Baby Boomer cohort. However, these increases are not significant. Conversely, the proportion of respondents that identified as Puerto Rican was relatively stable across older Latino birth cohorts (ranging from 8.3% to 10.8%). In contrast, the proportion of older Latinos who identified as Cuban decreased from 7.2% in the Late HRS cohort to 2.7% in the Mid Baby Boomer cohort.

Older Latinos overwhelmingly identified racially as White across all HRS birth cohorts (except for the Late Baby Boomer cohort). However, the proportion of respondents that identified as White has declined with each successive cohort. For instance, 78.7% of Latino respondents in the Late HRS cohort identified racially as White compared to 45.6% of respondents in the Late Baby Boomer cohort. Latinos who identified racially as Black comprised less than 5% across all HRS birth cohorts with Puerto Ricans and “other” Latinos more likely to have identified as Black than other ethnic origin groups (results not shown). Moreover, our results indicate that Latinos who identified as some “other” race have increased with each successive birth cohort, from 19.2% in the Late HRS cohort to 52.1% in the Late Baby Boomer cohort.

A majority of Latinos also identified as foreign-born, with Early Baby Boomer (57.2%), Mid Baby Boomer (59.6%), and Late Baby Boomer (60.3%) cohorts having the largest proportion of foreign-born respondents. Language of interview did not significantly differ across older Latino birth cohorts, though it is noteworthy that approximately 40% of older Latinos completed their baseline interview in Spanish. Moreover, nearly 90% of respondents who completed interviews in Spanish were foreign-born (results not shown).

Our results also revealed significant variation in socioeconomic status among Latinos across birth cohorts. Among the Late HRS cohort, 59.3% of respondents reported a less than high school education. Increases in educational attainment were observed with each successive birth cohort, with 30.5% of Late Baby Boomers reporting a less than high school education—a 28.8 percentage point reduction between the initial Late HRS cohort and the youngest cohort in the study design. Although we observed educational attainment increases among the Early-, Mid-, and Late-Baby Boomer birth cohorts, the proportion of respondents below the federal poverty threshold remained stable across HRS birth cohorts at approximately 21%. Similar to the patterns observed with educational attainment, household wealth (adjusted for inflation in 2020 dollars) also increased among older Latinos with each successive birth cohort, except for the Mid Baby Boomer cohort who reported lower household wealth than the Early Baby Boomer cohort.

Health and Health Behaviors

Table 2 presents cross-cohort comparisons of health and health behavior characteristics across the five older Latino birth cohorts. Hypertension was the most reported chronic condition across birth cohorts, with prevalence rates increasing in each subsequent birth cohort, from 26.3% among the Late HRS cohort to 41.5% among the Late Baby Boomers. Diabetes was the second most reported chronic condition across birth cohorts. Similar to hypertension, we observed an increase in the prevalence of diabetes with each successive birth cohort. Notably, the prevalence of diabetes increased significantly from the Late HRS cohort (10.1%) to the Late Baby Boomer cohort (30.4%).

Table 2.

Baseline Health Characteristics of the Latino Population Over HRS Study Periods

| Cohort | Late HRS | War Baby | Early Baby Boomer | Mid Baby Boomer | Late Baby Boomer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth year | 1936–1941 | 1942–1947 | 1948–1953 | 1954–1959 | 1960–1965 | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Chronic conditions | ||||||||||

| Hypertension | 137 | 26.3a,b | 69 | 26.2a,b | 147 | 32.0b | 304 | 36.0c,d | 353 | 41.5c,d,e |

| Diabetes | 52 | 10.1a,b | 35 | 11.9a,b | 70 | 14.6a,b | 185 | 21.8b,c,d,e | 244 | 30.4a,c,d,e |

| Heart disease | 34 | 6.0 | 13 | 5.0 | 38 | 7.1 | 53 | 5.1 | 61 | 7.8 |

| Stroke | 8 | 1.2b | 6 | 2.0 | 9 | 2.4 | 21 | 2.1b | 34 | 4.7a,c |

| Cancer | 11 | 2.4 | 5 | 2.4 | 21 | 4.7 | 33 | 4.2 | 39 | 4.7 |

| Lung disease | 11 | 2.6 | 3 | 1.8 | 8 | 2.2b | 31 | 3.3 | 42 | 4.9 |

| Disability | ||||||||||

| Any ADL | 80 | 15.6 | 32 | 13.2 | 74 | 15.2 | 150 | 17.2 | 114 | 13.7 |

| Health behaviors | ||||||||||

| Obesity | 141 | 27.3a,b,e | 72 | 29.2a,b | 164 | 35.6a,b,c | 433 | 51.3c,d,e | 414 | 50.6c,d,e |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||

| Current smoker | 118 | 24.9b,c | 41 | 20.0 | 89 | 18.8c | 164 | 20.4 | 140 | 16.7c |

| Former smoker | 167 | 32.4 | 64 | 28.5 | 142 | 31.1 | 270 | 35.2 | 241 | 29.6 |

| Never smoker | 232 | 42.7b,d,e | 126 | 51.4c | 222 | 50.1c | 413 | 44.4b | 463 | 53.7a,c |

| Health insurance | ||||||||||

| Government | 68 | 12.6b | 33 | 15.1b | 74 | 15.4b | 142 | 14.7b | 237 | 24.1a,c,d,e |

| Private | 236 | 48.0d | 133 | 57.0a,c | 234 | 54.9a | 358 | 46.5b,d,e | 428 | 54.3a |

| Doctor’s visit in previous 2 years | 350 | 69.1b,d,e | 190 | 82.1a,c | 388 | 87.1a,b,c | 608 | 74.9d,e | 642 | 75.5c,e |

| N | 507 | 231 | 453 | 847 | 844 |

Notes: Unweighted Ns and weighted percentages. Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding. ADL = activity of daily living; HRS = Health and Retirement Study.

aSignificantly different from Mid Baby Boomers.

bSignificantly different from Late Baby Boomers.

cSignificantly different from Late HRS.

dSignificantly different from War Babies.

eSignificantly different from Early Baby Boomers.

Our findings further show that heart disease and cancer prevalence was relatively low (less than 10%) among Latinos and did not differ substantially between birth cohorts. Although stroke was also a low-prevalence disease among older Latinos, we observed stark differences between older cohorts and younger birth cohorts. For instance, the prevalence of stroke in the Late Baby Boomer cohort (4.7%) was over triple that of the Late HRS cohort (1.2%). Similarly, lung disease was observed to be a low-prevalence disease among older Latinos, though prevalence rates have increased from the Late HRS cohort (2.6%) to the Late Baby Boomer cohort (4.9%). In contrast, the prevalence of any ADL disability (defined as any difficulty with bathing, eating, dressing, walking across a room, and getting in and out of bed) was observed to be between 13.2% and 17.2%, with no significant differences found across birth cohorts.

Obesity was highly prevalent among older Latinos (>27%) and increased with each successive birth cohort. Markedly, the prevalence of obesity in the Late Baby Boomer cohort (50.6%) was nearly double that of the Late HRS cohort (27.3%). Although the prevalence of smoking was generally low among older Latinos, it varied with approximately a quarter of respondents in the Late HRS cohort reporting being current smokers, followed by the Mid Baby Boomer (20.4%) and War Baby cohorts (20.0%). In contrast, Early Baby Boomer (18.8%) and Late Baby Boomer (16.7%) cohorts reported the lowest levels of current smokers.

Finally, the majority of Latinos across birth cohorts reported having either government or private (e.g., employer-sponsored) health insurance. Late Baby Boomers were more likely to report having government health insurance coverage (24.1%) compared to earlier birth cohorts (12.6%–15.4%). Conversely, respondents in the War Baby (57.0%), Early Baby Boomer (54.9%), and Late Baby Boomer (54.3%) cohorts were more likely to report having private health insurance coverage relative to earlier Late HRS (48%) and Mid Baby Boomer (46.5%) cohorts. As health insurance coverage is usually a preceptor to receiving health care, most Latinos reported seeing a doctor in the previous 2 years (or 12 months for those interviewed in 1992). Latinos in the Early Baby Boomer cohort were the most likely to have seen a doctor (87.1%), whereas Latinos in the Late HRS cohort were the least likely to have seen a doctor (69.1%), which may reflect the shorter reporting period.

Discussion

Increasing growth and diversity among the older U.S. Latino population make it imperative that researchers investigate changes in the composition of this population as it will have implications for researchers, policymakers, health care professionals, and others seeking to anticipate the needs of this rapidly aging population (Angel & Angel, 2006, 2015; Vega et al., 2015). In this study, we used nationally representative data from the HRS to examine whether there have been changes in the demographic composition and health characteristics of five HRS older Latino birth cohorts. We used birth cohorts to investigate compositional changes among older Latinos because each cohort experiences different historical, cultural, and social contexts that shape life course events and subsequent health (Elder et al., 2003).

Comparisons of demographic and health characteristics across five older birth cohorts of Latino respondents in the HRS indicate that there have been significant changes in demographic and health and health behavior characteristics over time. Specifically, we document changes in the Census region where older Latinos live in the United States, declines among older Latinos that self-identify as Mexican origin, and declines among older Latinos who self-identify racially as White. In addition, we document increases in the foreign-born population, educational attainment, government-sponsored health insurance, and the prevalence of chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity. Below we focus our discussion on these changes and contextualize how these differences are important factors to consider when examining the health and well-being of older Latinos residing in the United States.

First, the above findings indicate that residential patterns of older Latinos have changed across HRS birth cohorts, with population increases in the Midwest and West Census regions among younger birth cohorts. This observed change is particularly important given the vast literature demonstrating geographic disparities in disease risk factors, access to health care, quality of care, and health outcomes (García & Ailshire, 2019; Pastor, 2001; Rosenbaum et al., 2002). For example, a study of U.S. Latino patients aged 53–75 hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction found that Latinos residing in the Northeast were more likely to have Medicaid and a higher prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors relative to other U.S. regions (Krim et al., 2011). Conversely, Latinos in the Midwest and West regions were less likely to have Medicaid and had relatively healthier profiles (i.e., lower prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors) than the Northeast region (Krim et al., 2011). This suggests that the increased spatial clustering of older Latinos in the Midwest and West regions may be associated with exposures to environmental conditions (i.e., availability, affordability, and accessibility of health-related resources) that are linked to better health relative to other regions (i.e., Northeast). Moreover, the social environments of Latinos in these regions may decrease the biological embedding of deleterious experiences associated with their socioeconomic and material conditions that increase the risk of disease (Moore, 2014).

Second, our results show that Latinos who self-identified as Mexican—the largest ethnic origin group across birth cohorts—accounted for more than half of HRS Latinos in the study. However, we document a decline in respondents who self-identified as Mexican among recent birth cohorts of Latinos, which may reflect recent trends of fewer Mexican-origin individuals migrating to the United States, and an increasing number of Mexican migrants leaving the United States to return home (Flores, 2017b). Although we document a decline among the largest Latino subgroup in the HRS, without ethnic origin data (other than Mexican) from the most recent cohort—Late Baby Boomers—we are unable to draw conclusions about the changes in ethnic composition in the Latino population. Nonetheless, we want to highlight the importance of focusing on the ethnocultural determinants of health as ethnic origin is a proxy of the sociopolitical circumstances that influence the context of migration (e.g., occupational opportunities, involuntary displacement), geographic dispersion of residential location, socioeconomic status (e.g., educational attainment, income, wealth), behavioral factors (e.g., diet, smoking), psychosocial factors (e.g., social support), health care (e.g., access, utilization, quality), and health outcomes (Ramírez García, 2019; Walker et al., 2016).

Third, we also find that the Baby Boomer cohorts were less likely to identify as racially White than older birth cohorts, which may reflect changes in the ethnoracial assignment and self-identification of Latinos. For instance, Mexican Americans were classified as White in the 1950 Census and remained that way until the OMB Directive of May 12, 1977 created the ethnic category “Hispanic” (Waterson, 2006). Moreover, when the first wave of Cuban immigrants came to the United States after the Cuban Revolution of 1959—known as the “Golden Exiles”—they were racialized as White because these Cubans mostly came from the upper and middle strata of Cuban society (e.g., military officers, political leaders, professionals) and were well educated and light-skinned (Duany, 1999). The decline of Latinos self-identifying as racially White may be partially attributed to a multidimensional understanding of their identities that simultaneously incorporate physical characteristics (e.g., skin color and hair texture), culture (e.g., having roots in Latin America and the Caribbean), personal politics (e.g., not identifying with non-Latino White and Anglo Americans), acculturation levels, and social class. Although this shows that racial self-identification among U.S. Latinos is nuanced; race and racialization processes influence how individual, psychosocial, and contextual opportunities and resources are filtered in U.S. society (Borrell, 2005). In addition, qualitative studies have revealed that some Latinos perceive the term “Latino” as a distinct racial category due to their collective experiences of discrimination and pejorative stereotyping in the United States (Almaguer, 2012). Furthermore, the “othering” of Latinos in U.S. society may have significant population health consequences, such as creating barriers to opportunity structures and access to health care due to the deeply rooted and long-lasting effects of structural racialization (e.g., sociopolitical marginalization and material disadvantage; López & Vargas Poppe, 2021).

Fourth, we document an increase in foreign-born Latinos among Baby Boomer cohorts, reflecting the general trend of aging among all immigrants, as well as an increase in immigrants who are coming to the United States at older ages than in previous birth cohorts (Population Reference Bureau, 2013). The greater proportion of immigrants observed in recent birth cohorts suggests that there may be a larger number of older Latinos who suffer from acculturative stressors, including adaptation to a new environment, language barriers, economic distress, occupational-related exploitation, housing instability, legal status stressors, discrimination (i.e., xenophobia), and loss of social support (Arbona et al., 2010; Cuellar et al., 2004; Torres & Wallace, 2013). Long-term exposure and negative appraisal of these stressors may result in physiological dysregulation, accelerated aging, and provoke deleterious disease trajectories for older Latino immigrants (Mangold et al., 2012; McEwen & Seeman, 1999).

Although prior research has documented an immigrant health advantage among older Latinos, more recent evidence suggests that this health advantage diminishes over time with increased duration in the United States. For example, data from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos document lower scores of allostatic load among foreign-born Latinos relative to their U.S.-born counterparts; however, these differences are less pronounced and insignificant at ages 55 and older. The erosion of this health advantage among older foreign-born Latinos may be partially attributed to the challenges and stressors associated with acculturation over time, which has been shown to affect the cortisol awakening response (a biological marker of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal activity; Mangold et al., 2012). This cortisol awakening response has been found to be associated with major depression (Dedovic & Ngiam, 2015), type 2 diabetes (Hackett et al., 2016), and changes in the brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (Violanti et al., 2018).

Fifth, we document a significant increase in educational attainment among older Latino birth cohorts, with Late Baby Boomers exhibiting the highest level of education attainment compared to other HRS birth cohorts. This is particularly important given the robust relationship between educational attainment and population health outcomes, specifically cognitive impairment and dementia (Baker et al., 2011; Wight et al., 2006; Zeki Al Hazzouri et al., 2011). However, it is important to note that racial and ethnic disparities in educational attainment among older adults in the United States persist, with older U.S.- and foreign-born Latinos exhibiting the poorest educational outcomes compared to older Black and White adults (Garcia et al., 2021).

Last, our findings of a significant increase in the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and obesity among Latinos in the Baby Boomer cohorts—especially the Late Baby Boomers—is concerning given the increasing health care costs associated with these conditions (Rowley et al., 2017). Although increases in hypertension and diabetes may reflect an increase in the incidence of disease and a decrease in mortality (Crimmins et al., 2019), we observe this increase in prevalence in adults aged 51–56, which suggests an early-onset and early diagnosis of these conditions in more recent birth cohorts. Several studies report that high triglycerides, high total cholesterol, and obesity are associated with early-onset (age ≤40) hypertension and diabetes (Chen et al., 2004; Neufeld et al., 1998; Suvila et al., 2021). While there has been a tremendous focus on the dietary and exercise behaviors of Latinos to combat obesity and its related conditions, recent attention has shifted to examining the types of environments Latinos live in that influence health due to their structural vulnerability (i.e., material disadvantage; Greenhalgh & Carney, 2014). For example, the neighborhood environment serves as an important context for understanding obesity and chronic disease as they profoundly affect the resources an individual has and whether they will consume nutritious food and have options to engage in physical activity. A study on adults aged 55 and older (which included Latinos) found that living in a neighborhood with greater economic advantage was associated with a decreased risk for obesity (Grafova et al., 2008). Thus, policymakers should focus attention on creating opportunities for healthy living by investing in Latino communities (e.g., increasing access to affordable healthy foods, green spaces, quality housing, health and medical services, social and educational institutions) if we want to delay the onset of obesity and chronic disease. Moreover, given that the Late Baby Boomer cohort exhibited higher rates of government-sponsored health insurance than previous birth cohorts, we can infer that Latinos in the Late Baby Boomer cohort are potentially facing higher economic insecurity and financial strain and are more likely to be living in underresourced communities.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study that warrant consideration. First, while the HRS is representative of the U.S. Latino population, the information presented in this study is skewed toward that of the Mexican-origin population. Previous studies have documented demographic and health differences among Latino subgroups by ethnic origin (Dudley et al., 2017; Fenelon et al., 2017; C. Garcia et al., 2018; M. A. Garcia et al., 2018; Salazar et al., 2016). We acknowledge the importance of these differences, but do not include them in this analysis due to sample sizes available for the available subgroups (i.e., Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban) across the study period.

Second, the HRS-restricted data do not provide detailed information on ethnic origin for Latinos categorized as “other,” which precludes further inferences of Latinos in this group. Nonetheless, this category is included to demonstrate the growing demographic diversity of the Latino population, particularly among those who are classified by the HRS as “other” Latino. Third, disease prevalence was based on self-reported disease diagnosis rather than using clinical measures. Although the HRS does have biomarker information from respondents, these measures were collected beginning in 2006 and excluded from the present analysis. Thus, the birth cohort differences that we noted should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, the above findings are based on cross-sectional comparisons of Latino birth cohorts from a nationally representative longitudinal study. Future research should aim to further disentangle age–period–cohort effects (e.g., the Great Recession) not captured in this study.

Finally, the findings from the present study need to be validated with another nationally representative data set, such as the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) or the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BFRSS), to determine if Latino birth cohorts in the HRS are (a) nationally representative of older Latinos and (b) whether Latino birth cohorts in the HRS differ significantly from older Latinos in nationally representative cross-sectional surveys. We recognize the limitations of comparing HRS birth cohorts (a longitudinal study) with synthetic cohorts in cross-sectional studies (i.e., NHIS or BFRSS); however, in supplementary analyses, we compared select demographic indicators in the NHIS to demographic indicators in the HRS (results not shown) and corroborated the demographic patterns reported above, with the exception of Census region of residence. Despite these limitations, our study identifies the need to use nationally representative data to monitor the health and well-being of all older Latinos in the United States over time and across birth cohorts.

Contributor Information

Catherine García, Department of Human Development and Family Science, Aging Studies Institute, Center for Aging and Policy Studies, Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA.

Marc A Garcia, Department of Sociology, Aging Studies Institute, Center for Aging and Policy Studies, Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion, Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, USA.

Jennifer A Ailshire, Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (R36AG057949).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Aguayo-Mazzucato, C., Diaque, P., Hernandez, S., Rosas, S., Kostic, A., & Caballero, A. E. (2019). Understanding the growing epidemic of type 2 diabetes in the Hispanic population living in the United States. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews, 35(2), e3097. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almaguer, T. (2012). Race, racialization, and Latino populations in the United States. In HoSang D. M., LaBennett O., & Pulido L. (Eds.), Racial formation in the twenty-first century (pp. 143–161). University of California Press. doi: 10.1525/california/9780520273436.003.0008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angel, R. J., & Angel, J. L. (2006). Diversity and aging in the United States. In R. Binstock, L. George, S. Cutler, J. Hendricks, & J. Schulz (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the social sciences (pp. 94–110). Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/B978-012088388-2/50009-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angel, R. J., & Angel, J. L. (2015). Latinos in an aging world: Social, psychological, and economic perspectives. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Arbona, C., Olvera, N., Rodriguez, N., Hagan, J., Linares, A., & Wiesner, M. (2010). Acculturative stress among documented and undocumented Latino immigrants in the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 32(3), 362–384. doi: 10.1177/0739986310373210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, D. P., Leon, J., Smith Greenaway, E. G., Collins, J., & Movit, M. (2011). The education effect on population health: A reassessment. Population and Development Review, 37(2), 307–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00412.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell, L. N. (2005). Racial identity among Hispanics: Implications for health and well-being. American Journal of Public Health, 95(3), 379–381. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.-W., Wu, S.-Y., & Pan, W.-H. (2004). Clinical characteristics of young-onset hypertension—Implications for different genders. International Journal of Cardiology, 96(1), 65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins, E. M., Zhang, Y. S., Kim, J. K., & Levine, M. E. (2019). Changing disease prevalence, incidence, and mortality among older cohorts: The Health and Retirement Study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 74(Suppl. 1), 21–26. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar, I., Bastida, E., & Braccio, S. M. (2004). Residency in the United States, subjective well-being, and depression in an older Mexican-origin sample. Journal of Aging and Health, 16(4), 447–466. doi: 10.1177/0898264304265764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedovic, K., & Ngiam, J. (2015). The cortisol awakening response and major depression: Examining the evidence. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 1181, 1181–1189. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S62289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duany, J. (1999). Cuban communities in the United States: Migration waves, settlement patterns and socioeconomic diversity. Pouvoirs dans la Caraïbe Revue du Centre de recherche sur les pouvoirs locaux dans la Caraïbe, 11, 69–103. doi: 10.4000/plc.464 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, K. A., Weng, J., Sotres-Alvarez, D., Simonelli, G., Cespedes Feliciano, E., Ramirez, M., Ramos, A. R., Loredo, J. S., Reid, K. J., Mossavar-Rahmani, Y., Zee, P. C., Chirinos, D. A., Gallo, L. C., Wang, R., & Patel, S. R. (2017). Actigraphic sleep patterns of U.S. Hispanics: The Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. Sleep, 40(2). doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder, G. H., Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In Mortimer J. T. & Shanahan M. J. (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–19). Springer US. doi: 10.1007/978-0-306-48247-2_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fenelon, A., Chinn, J. J., & Anderson, R. N. (2017). A comprehensive analysis of the mortality experience of Hispanic subgroups in the United States: Variation by age, country of origin, and nativity. SSM—Population Health, 3, 245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, G. G., & Ryan, L. H. (2018). Overview of the Health and Retirement Study and introduction to the special issue. Work, Aging and Retirement, 4(1), 1–9. doi: 10.1093/workar/wax032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores, A. (2017a). 2015, Hispanic population in the United States statistical portrait (statistical portrait of Hispanics in the United States). Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2017/09/18/2015-statistical-information-on-hispanics-in-united-states/#share-foreign-born [Google Scholar]

- Flores, A. (2017b). How the U.S. Hispanic population is changing. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/18/how-the-u-s-hispanic-population-is-changing/ [Google Scholar]

- Flores, A., López, G., & Radford, J. (2017). 2015, Hispanic population in the United States statistical portrait (statistical portrait of Hispanics in the United States). Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2017/09/18/2015-statistical-information-on-hispanics-in-united-states-trend-data/ [Google Scholar]

- García, C., & Ailshire, J. A. (2019). ¿Importa Dónde Vivimos? How regional variation informs our understanding of diabetes and hypertension prevalence among older Latino populations. In Vega W. A., Angel J. L., Gutiérrez Robledo L. M. F., & Markides K. S. (Eds.), Contextualizing health and aging in the Americas (pp. 39–62). Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-00584-9_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, C., Garcia, M. A., & Ailshire, J. A. (2018). Sociocultural variability in the Latino population: Age patterns and differences in morbidity among older US adults. Demographic Research, 38, 1605–1618. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2018.38.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M. A., Downer, B., Chiu, C.-T., Saenz, J. L., Ortiz, K., & Wong, R. (2021). Educational benefits and cognitive health life expectancies: Racial/ethnic, nativity, and gender disparities. The Gerontologist, 61(3), 330–340. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M. A., Downer, B., Crowe, M., & Markides, K. S. (2017). Aging and disability among Hispanics in the United States: Current knowledge and future directions. Innovation in Aging, 1(2), igx020. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igx020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M. A., Garcia, C., Chiu, C.-T., Raji, M., & Markides, K. S. (2018). A comprehensive analysis of morbidity life expectancies among older Hispanic subgroups in the United States: Variation by nativity and country of origin. Innovation in Aging, 2(2), 1–12. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igy014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M. A., Reyes, A. M., Garcia, C., & Chiu, C.-T. (2020). Nativity and country of origin variations in life expectancy with functional limitations among older Hispanics in the United States. Research on Aging, 42(7–8), 199–207. doi: 10.1177/0164027520914512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M. A., Warner, D. F., García, C., Downer, B., & Raji, M. (2021). Age patterns in self-reported cognitive impairment among older Latino subgroups and non-Latino whites in the U.S., 1997 to 2018: Implications for public health policy. Innovation in Aging, 5(4), 1–15. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igab039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González, H. M., Tarraf, W., Fornage, M., González, K. A., Chai, A., Youngblood, M., de los Angeles Abreu, M., Zeng, D., Thomas, S., Talavera, G. A., Gallo, L. C., Kaplan, R., Daviglus, M. L., & Schneiderman, N. (2019). A research framework for cognitive aging and Alzheimer’s disease among diverse US Latinos: Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos–Investigation of Neurocognitive Aging (SOL-INCA). Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 15(12), 1624–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.08.192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafova, I. B., Freedman, V. A., Kumar, R., & Rogowski, J. (2008). Neighborhoods and obesity in later life. American Journal of Public Health, 98(11), 2065–2071. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, S., & Carney, M. (2014). Bad biocitizens? Latinos and the US “obesity epidemic.” Human Organization, 73(3), 267–276. doi: 10.17730/humo.73.3.w53hh1t413038240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, R. A., Kivimäki, M., Kumari, M., & Steptoe, A. (2016). Diurnal cortisol patterns, future diabetes, and impaired glucose metabolism in the Whitehall II cohort study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 101(2), 619–625. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, R. (2005). Survey design and methodology in the Health and Retirement Study and the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. doi: 10.7826/ISR-UM.06.585031.001.05.0012.2005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Health and Retirement Study. (2011). Sample sizes and response rates.https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/biblio/sampleresponse.pdf

- Health and Retirement Study. (2017). Sample sizes and response rates.https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/biblio/ResponseRates_2017.pdf

- Hummer, R. A., & Hayward, M. D. (2015). Hispanic older adult health & longevity in the United States: Current patterns & concerns for the future. Daedalus, 144(2), 20–30. doi: 10.1162/DAED_a_00327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juster, F. T., & Suzman, R. (1995). An overview of the Health and Retirement Study. The Journal of Human Resources, 30, S7. doi: 10.2307/146277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad, J. M. (2020). Hispanics have accounted for more than half of total U.S. population growth since 2010. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/10/hispanics-have-accounted-for-more-than-half-of-total-u-s-population-growth-since-2010/ [Google Scholar]

- Krim, S. R., Vivo, R. P., Krim, N. R., Cox, M., Hernandez, A. F., Peterson, E. D., Fonarow, G. C., Piña, I. L., Schwamm, L. H., & Bhatt, D. L. (2011). Regional differences in clinical profile, quality of care, and outcomes among Hispanic patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction in the Get with Guidelines–Coronary Artery Disease (GWTG-CAD) Registry. American Heart Journal, 162(6), 988–995.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López, V., & Vargas Poppe, S. (2021). Toward a more perfect union: Understanding systemic racism and resulting inequity in Latino communities. UNIDOS US. https://www.unidosus.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/unidosus_systemicracismpaper.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mangold, D., Mintz, J., Javors, M., & Marino, E. (2012). Neuroticism, acculturation and the cortisol awakening response in Mexican American adults. Hormones and Behavior, 61(1), 23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, B. S., & Seeman, T. (1999). Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress: Elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896(1), 30–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K. D. (2014). An ecological framework of place: Situating environmental gerontology within a life course perspective. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 79(3), 183–209. doi: 10.2190/AG.79.3.a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld, N. D., Raffel, L. J., Landon, C., Chen, Y. I., & Vadheim, C. M. (1998). Early presentation of type 2 diabetes in Mexican-American youth. Diabetes Care, 21(1), 80–86. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noe-Bustamante, L. (2020). Education levels of recent Latino immigrants in the U.S. reached new high as of 2018. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/07/education-levels-of-recent-latino-immigrants-in-the-u-s-reached-new-highs-as-of-2018/ [Google Scholar]

- Ofstedal, M. B., & Weir, D. R. (2011). Recruitment and retention of minority participants in the Health and Retirement Study. The Gerontologist, 51(Suppl. 1), S8–S20. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, M. (2001). Geography and opportunity. In Smelser N. J., Wilson W. J., & Mitchell F. (Eds.), America becoming: Racial trends and their consequences: Volume I (pp. 435–468). The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/9599 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Population Reference Bureau. (2013). Elderly immigrants in the United States (today’s research on aging).https://www.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/TRA29-2013-elderly-us-immigrants.pdf

- Quiñones, A. R., Botoseneanu, A., Markwardt, S., Nagel, C. L., Newsom, J. T., Dorr, D. A., & Allore, H. G. (2019). Racial/ethnic differences in multimorbidity development and chronic disease accumulation for middle-aged adults. PLoS One, 14(6), e0218462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez García, J. I. (2019). Integrating Latina/o ethnic determinants of health in research to promote population health and reduce health disparities. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(1), 21–31. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, J. E., Reynolds, L., & Deluca, S. (2002). How do places matter? The geography of opportunity, self-efficacy and a look inside the black box of residential mobility. Housing Studies, 17(1), 71–82. doi: 10.1080/02673030120105901 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, W. R., Bezold, C., Arikan, Y., Byrne, E., & Krohe, S. (2017). Diabetes 2030: Insights from yesterday, today, and future trends. Population Health Management, 20(1), 6–12. doi: 10.1089/pop.2015.0181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, C. R., Strizich, G., Seeman, T. E., Isasi, C. R., Gallo, L. C., Avilés-Santa, L. M., Cai, J., Penedo, F. J., Arguelles, W., Sanders, A. E., Lipton, R. B., & Kaplan, R. C. (2016). Nativity differences in allostatic load by age, sex, and Hispanic background from the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. SSM—Population Health, 2, 416–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. A., Branch, L. G., Scherr, P. A., Wetle, T., Evans, D. A., Hebert, L., & Taylor, J. O. (1990). Short-term variability of measures of physical function in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 38(9), 993–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb04422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnega, A., & Weir, D. R. (2014). The Health and Retirement Study: A public data resource for research on aging. Open Health Data, 2(1), 1–4. doi: 10.5334/ohd.am [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2019). Stata statistical software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Suvila, K., Lima, J. A. C., Cheng, S., & Niiranen, T. J. (2021). Clinical correlates of early-onset hypertension. American Journal of Hypertension, 34(9), 915–918. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpab066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres, J. M., & Wallace, S. P. (2013). Migration circumstances, psychological distress, and self-rated physical health for Latino immigrants in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 103(9), 1619–1627. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021). Consumer Price Index Retroactive Series (R-CPI-U-RS).https://www.bls.gov/cpi/research-series/r-cpi-u-rs-home.htm

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2018a). Projected age groups and sex composition of the population: Main projections series for the United States, 2017–2060.https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2018b). Race and Hispanic origin by selected age groups: Main projections series for the United States, 2017–2060.https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html

- Vega, W. A., Markides, K. S., Angel, J. L., & Torres-Gil, F. M. (Eds.). (2015). Challenges of Latino aging in the Americas. Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-12598-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Violanti, J. M., Fekedulegn, D., Andrew, M. E., Charles, L. E., Gu, J. K., & Miller, D. B. (2018). Subclinical markers of cardiovascular disease among police officers: A longitudinal assessment of the cortisol awakening response and flow mediated artery dilation. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 60(9), 853–859. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R. J., Strom Williams, J., & Egede, L. E. (2016). Influence of race, ethnicity and social determinants of health on diabetes outcomes. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 351(4), 366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterson, A. (2006). Are Latinos becoming “white” folk? And what that still says about race in America. Transforming Anthropology, 14(2), 133–150. doi: 10.1525/tran.2006.14.2.133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wight, R. G., Aneshensel, C. S., Miller-Martinez, D., Botticello, A. L., Cummings, J. R., Karlamangla, A. S., & Seeman, T. E. (2006). Urban neighborhood context, educational attainment, and cognitive function among older adults. American Journal of Epidemiology, 163(12), 1071–1078. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeki Al Hazzouri, A., Haan, M. N., Galea, S., & Aiello, A. E. (2011). Life-course exposure to early socioeconomic environment, education in relation to late-life cognitive function among older Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Journal of Aging and Health, 23(7), 1027–1049. doi: 10.1177/0898264311421524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]