Abstract

Objectives:

To describe palliative, concurrent, and hospice care in pediatric oncology in the United States (US), present a clinical scenario illustrating palliative and hospice care, including eligibility for concurrent care, insurance coverage and billing, barriers to accessing quality pediatric palliative and hospice care, and implications for oncology nursing practice.

Data Sources:

Peer-reviewed articles, clinical practice guidelines, professional organizations, and expert clinical opinion, examining pediatric oncology, palliative care, and hospice care.

Conclusion:

Understanding the goals of palliative and hospice care and the differences between them is important in providing holistic, goal-directed care.

Implications for Nursing Practice:

Oncology nurses play a pivotal role in supporting the goals of pediatric palliative care and hospice care and in educating patients and their families. Nurses form trusting relationships with pediatric oncology patients and their families and are in a position to advocate for best palliative care practices as disease progresses to end-of-life, including when appropriate concurrent care or hospice.

Keywords: pediatric oncology, pediatric palliative care, pediatric concurrent care, pediatric hospice, pediatric oncology nursing

Children, adolescents and young adults (AYA) living with cancer undergo intense treatment (e.g., cellular therapies, hematopoietic stem cell transplants, radiotherapy, experimental therapies) to achieve cure, which may have adverse physical and psychosocial symptoms. Despite improvements in cancer treatment and outcomes, some children will die. In 2020, approximately 16,850 American children under the age of 20 years were diagnosed with cancer, and 1,730 are expected to die.1 Cancer is the leading disease-related cause of death in children.2 Therefore, pediatric patients with cancer require not only expert oncology care, but also care from clinicians skilled in pain and symptom management, communication, existential suffering, distress, and end-of-life (EOL) care. The subspecialty of palliative care has evolved to meet these needs by encompassing both a philosophy and delivery of compassionate care that prioritize quality of life, function, and spiritual and personal growth while minimizing suffering. Pediatric palliative care (PPC), which has developed as a subspecialty over the past several decades,3–5 focuses on pediatric patients who are experiencing life-limiting, chronic, or complex conditions and their families. Although the terms are sometimes confused, palliative care and hospice care are not synonymous, however hospice care is a component of palliative care.6 Hospice care focuses more specifically on providing holistic, interdisciplinary care to pediatric patients nearing the end-of-life.7

Oncology nurses have been instrumental in providing holistic support to patients and families and conducting quality of life research,8 long before palliative care became a subspecialty. Likewise, pediatric oncology nurses form trusting relationships with patients and their families and are in a position to advocate for best palliative care practices as the disease progression leads to EOL-focused care, including hospice, or when appropriate, concurrent care. Nurses play a pivotal role in supporting the goals of PPC and in educating patients and their families.

This paper provides an overview of palliative, hospice and concurrent care within the context of childhood cancer. For the sake of simplicity, we will use the expressions “children” and “childhood cancer” in a broad sense to encompass both children and adolescents. Implications for practice, education, and research are identified in an effort to demonstrate not only how far we have come but the critical need for ongoing work in this field.

Pediatric Palliative Care

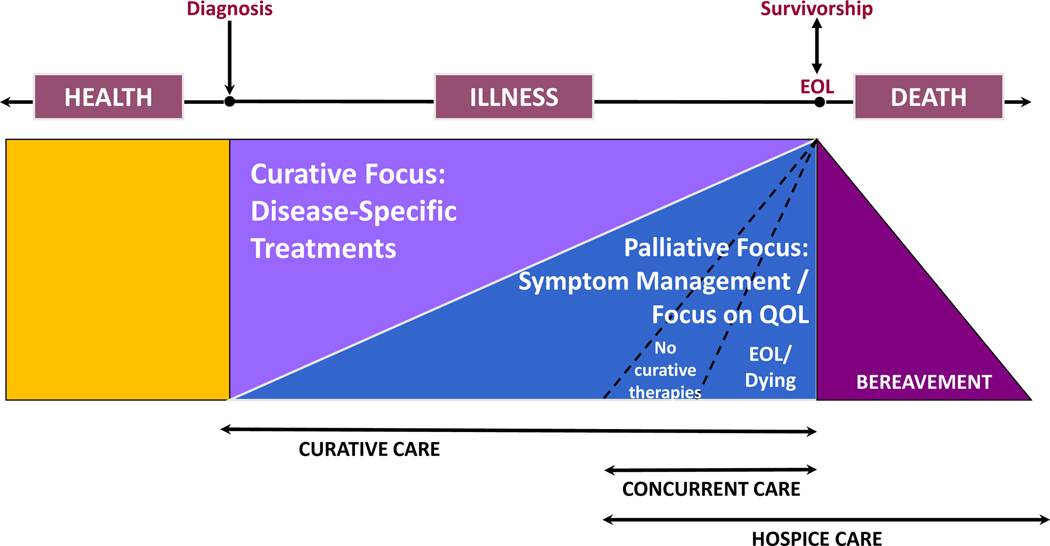

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines pediatric palliative care as “an approach that enhances the quality of life of patients and their families facing life-threatening illness and is appropriate early in the course of the illness in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life.” 7 The goal of palliative care is to provide an additional layer of holistic support for the patient, the family, and other caregivers through an interdisciplinary team who works alongside the disease-focused team (e.g., oncology service). Ideally, palliative care should be incorporated early in the disease trajectory9 and be flexibly prioritized depending upon where the patient is along the continuum from active treatment to survivorship or EOL (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Palliative & Hospice Care Continuum in Children with Cancer

This figure is an adaptation from National Quality Forum98

Pediatric oncology clinicians and other stakeholders have published standards for psychosocial care, which recommend palliative care as a standard of care for children and adolescents with cancer.10 When woven into routine pediatric oncology care, PPC enhances the assessment and management of complex symptoms and communication with patients and families. Such communication includes routine elicitation and clarification of goals of care, which are incorporated into shared decision-making and advance care planning (ACP).11

Palliative care can be viewed as both a philosophy, that is, an approach to care, and as an interdisciplinary team of individuals who specialize in the care of children with serious and complex illness. Palliative care as a philosophy should be embraced by all healthcare professionals caring for children with serious and complex illness, aiming to optimize the quality of life of the patient and family. This approach is referred to as “primary palliative care,” and in pediatric oncology, should include, at a minimum, eliciting goals of care from patients and families, documenting goals in the medical record, and providing care accordingly. Clinicians who specialize in palliative care have more advanced education, training, and practical experience that allows them to provide or direct palliative care in complex situations. Such care is often referred to as “specialty” or “secondary” palliative care.12

Despite the highly endorsed recommendations that all children with cancer receive palliative care, only 75% of children’s hospitals in the United States (US) have pediatric palliative care programs, which are largely weekday, business hour operations.11 The majority of palliative care provided to pediatric oncology patients is through their multidisciplinary oncology teams in the form of primary palliative care, whereas subspecialty palliative care is reserved for patients with refractory symptoms, complex psychosocial concerns, and/or challenging communication issues.13 Unfortunately, such services are often provided in the inpatient environment with limited outpatient and home-based services available.14 With increased utilization of PPC in outpatient settings, care delivery is evolving to include frameworks such as “floating clinics,” embedded PPC specialists, protocolized triggers for consultation or support and routine use of telehealth14 during palliative or hospice care.

In pediatric oncology, specialty PPC can either be embedded within the oncology program or freestanding; consult-based or trigger-based; and delivered by a solo provider or the full interdisciplinary team.15 Considerable variation exists among programs in terms of team structure, range of services, and sources of funding.16 Building off a successful model of palliative care integration into adult oncology programs, Kaye et al.17 proposed a holistic model, which leverages the role of an embedded pediatric palliative oncology expert into the pediatric oncology team. As part of the team, this embedded expert can identify opportunities and facilitate the provision of palliative care at all stages, to more patients, and across all settings of care such as inpatient, outpatient and home. Such a model is believed to enhance both the quality and efficiency of care.

Brock et al.15 provided preliminary results of such a program, at a large academic hospital in the southeast. After initiation of this program, patients who were introduced to palliative care services earlier in their illness trajectory; were less likely to die in the hospital and able to spend more time at home at the EOL, resulting in fewer days spent in the hospital. This program did not result in decreased enrollment in Phase I/II clinical trials, and participants’ overall survival time did not decrease. This demonstrates the feasibility of implementing such a model and suggests positive outcomes. More research is needed to examine this model and others at sites of different sizes with an emphasis on measuring patient- and family-reported outcomes.

A growing body of evidence demonstrates benefits for patients and families who receive palliative care. Adult studies have documented the benefits of initiating palliative care at the time of diagnosis.18 In addition, several recent systematic reviews reported the impact of specialty PPC.19,20 Patients who received specialty PPC experienced improved quality of life and symptom management. They also received fewer procedures (diagnostic and monitoring), earlier and more EOL discussions, fewer resuscitation events, and decreased rates of admission and death in the intensive care unit (ICU). Similarly, Vern-Gross and colleagues21 reported pediatric patients enrolled in a palliative care service experienced more hospice use, earlier implementation of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, and fewer hospital deaths. For AYAs followed by a palliative care team, earlier DNR orders were more common, and death in the ICU and/or on a ventilator were less common.22 Parents have also benefited from palliative care services reporting improved quality of life, reduction in their psychological distress,23 feeling better prepared for end-of-life care,24 and receiving anticipatory guidance during the bereavement period.25 Unfortunately, PPC is still often initiated too late in many situations, such as immediately prior to death. These delays in initiation of PPC result in lost opportunities for improved care and quality of life throughout the disease trajectory.26 Results of these studies underscore the importance of early initiation of palliative care and frequent assessment of goals of care and care preferences through goal-directed communication in response to the changing clinical situation of the child and family.

Pediatric Palliative Care in Practice

Throughout the cancer trajectory, pediatric oncology nurses provide developmentally appropriate care to patients. When patients do not understand their disease or treatment and side-effects, nurses provide education in a language that facilitates learning. Similarly, pediatric oncology nurses have opportunities to introduce the philosophy of palliative care at diagnosis, using developmentally appropriate language, and to help their patients and families build an understanding of the PPC resources and support available as disease progresses.

Quality of Life.

Fundamental goals of palliative care include a focus on symptoms and quality of life. Mitigating suffering at any point throughout the disease continuum is the core of palliative care. The time of diagnosis of a new pediatric oncology patient is characterized by fear, uncertainty and loss, followed in rapid succession by the side effects of chemotherapy or other cancer-directed therapies. Such side effects include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, other gastrointestinal complaints, pain and depression. See Table 1 for symptoms that are commonly managed in the context of PPC. Studies of patients and parents highlight their expectation that quality of life should be a high priority from the very beginning, emphasizing the need for early palliative care involvement.27 At the other end of the disease continuum, suffering may be greatest for patients at the EOL, compromising quality of life. When palliative care is actively engaged throughout the illness trajectory, patients and families are better prepared for future events, participate more in advance care planning, and suffering is reduced.24,28

Table 1:

Common Symptoms Managed in Pediatric Palliative Care

| Neurological |

|

|

| Delirium |

| Agitation |

| Restlessness |

| Insomnia/Somnolence |

| Anxiety |

| Confusion |

| Dysphagia |

| Clonus |

| Seizures |

| Depression |

|

|

| Respiratory |

|

|

| Oral secretions |

| Cough |

| Dyspnea |

| Fluid overload |

|

|

| Cardiovascular |

|

|

| Fluid overload |

|

|

| Genitourinary |

|

|

| Incontinence |

|

|

| Gastrointestinal |

|

|

| Nausea/Vomiting |

| Constipation |

| Anorexia/cachexia |

| Diarrhea |

| Ascites |

| Obstruction |

| Incontinence |

|

|

| Integumentary |

|

|

| Pruritus |

| Skin breakdown/wounds |

| Temperature changes |

|

|

| General |

|

|

| Pain |

| Fatigue |

| Fever |

| Infections |

Communication and Decision Making.

A core tenet of PPC within oncology is the facilitation of patient and family-centered communication. Improved communication is reported by families who receive PPC.29 Quality communication and the need for decision making support occur at different time points throughout the illness experience but are of particular importance at the cessation of cancer-directed treatment when considering salvage chemotherapy, experimental therapies (Phase I clinical trials), and palliative chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Within pediatric oncology, Sisk and colleagues have described eight unique purposes of communication: “(1) building relationships, (2) exchanging information (3) enabling self-management (4), making decisions (5) managing uncertainty (6) responding to emotions (7) providing validation (8) and supporting hope.”30 When considering these purposes, it is clear that developing effective lines and styles of communication among clinicians, patients and families are essential.31

Parents value open dialogue, and desire to be fully informed about their child’s situation and care. Further, they want to be involved in a continuous dialogue with the care team where they can express their opinions, share their experiences, and also safely express their fears and potential limitations as a care partner. These discussions should be carried out respectfully, using language that is comprehensible to the family, avoiding unnecessary medicalized jargon and using interpreters where appropriate.32 If bad news is to be delivered or discussed, families prefer a member of the team who is familiar with them to participate.32–34 For these difficult conversations, health care providers must be thoughtful and sensitive in how they deliver information and in their choice of language. See Table 2 for communication guidance throughout the disease trajectory.

Table 2.

Empathic Communication Throughout the Illness Trajectory

| Suggested Phrases | Rationale |

|---|---|

| At time of diagnosis: | |

| “What did the team share with you today?” | Explore what the family heard and understands; allows for any clarification. |

| “Given what you’ve heard from the team, what makes you most hopeful?” “What worries you the most?” | Allows for a better understanding of what the family’s hopes and worries are, further clarifies the family’s perception of the information. |

| “I can see this is not what you expected to hear” or “I can see this is difficult news to hear.” | Naming the family’s emotion can help to develop trust and a relationship with the family. |

| “It is so clear how much you love her.” | Providing respect statements to the family shows empathy. |

| Silence | Allows time for the family to process the information shared and allow space for their emotions. |

| When curative treatments are no longer available: | |

| “I wish there were therapies available to treat the cancer.” | Align with the family’s hopes and says “no” without saying “no.” |

| “I worry that doing more treatments will not allow him to stay out of the hospital like he’s wanting.” | Provides a level of concern without certainty to help align with the family’s hopes. |

| “I wonder if you’ve thought about what would happen if he doesn’t get better?” | A way of entering difficult conversations or to explore if a family has considered an option beyond cure. |

| “Given what you’ve heard today, I wonder if you could share with me what are you hoping for?” “What else are you hoping for?” | Allows for a better understanding of what the family’s hopes are, begins to identify the family’s goals of care and what is important to them if cure is not possible. |

| At end-of-life: | |

| “I wish there was something we could do to change this. I’m going to continue to monitor him to make sure he is comfortable; would you like to hold him as he is dying?” | Helpful when the family is struggling to not initiate resuscitative efforts; allows the family to know the condition cannot be reversed, that the child is actively dying and provides them with an active plan of “doing something.” |

| “I can’t even begin to imagine how difficult this is. Is there something we can do to be helpful right now?” | Provides the family comfort in knowing they are not alone. |

| Phrases to avoid: | Phrases to use instead: |

| “Withdraw care” – we never stop caring for our patients. | Redirection of care |

| “There’s nothing more we can do.” | “We will focus on those interventions which provide comfort and maximizes his quality of life.” |

| “I understand how you feel.” | “I can see how difficult this is for you.” |

Clinician concerns about the potential effects of communicating prognostic information have been described in the literature.35–37 Yet when queried, parents report wanting accurate prognostic information using numeric values.38 They do not want to hear nonspecific words, such as, “infrequent,” “uncommon,” “moderate,” or “reduced,” which may have very different meanings for different people. Even if the prognosis is poor and considered upsetting, parents describe wanting reliable and accurate prognostic information, which helps them maintain hope39 and supports their ability to trust the healthcare team.40

Unique Needs of Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs).

In providing palliative care to AYAs, their unique stage of development,41 decision making and communication needs must be taken into consideration. Many adolescents prefer to be involved in treatment decision making,42–47 but even for those who do not, they still prefer to be informed about their care.42,47

While many clinicians have previously excluded adolescents from advance care planning (ACP) discussions, research has documented the benefits of involving adolescents s in ACP.48–50 Lyon et al.51 developed and tested a three-session intervention, which engaged adolescents and their designated surrogates in the process of ACP. Results demonstrated that not only was it possible to have these conversations, but that discussing EOL situations actually reduced fear and anxiety versus causing it. In addition, the ACP process was reported to be worthwhile by patients and surrogates, who described improved understanding of the adolescent’s EOL wishes and treatment preferences. Adolescents who participate in ACP are more likely to receive early palliative care.51 “Voicing My CHOiCES” and “My Wishes” are pediatric specific guides, available online, and can be used to facilitate these difficult discussions.52–54 “Five Wishes” is an adult advance care planning guide, also available online.52

Clinical Vignette

Diagnosis and Introduction of Palliative Care.

At 14 years of age, Ryan received his cancer diagnosis. At presentation, he described pressure and fullness in his lower abdomen, constipation and frequent urination with urgency. When standard constipation therapy did not alleviate symptoms, his pediatrician ordered a CT scan, which showed a large pelvic mass with paraspinal involvement. A surgical biopsy was performed, and pathology confirmed a diagnosis of Ewing Sarcoma. Metastatic work-up showed multiple, bilateral pulmonary nodules.

The oncology team spent considerable time with Ryan and his family ensuring they understood Ryan’s diagnosis, prognosis, and the treatments required to treat his disease. They also spoke to Ryan and his family about including palliative care as part of his treatment and introduced them to the PPC team. The oncology team explained that palliative care would be an adjunct to Ryan’s treatment team, focusing on pain management, symptom control, and quality of life. As the PPC team included a psychologist and child life specialist, the PPC was also prepared to address psychosocial distress as well as important developmental considerations. Ryan then embarked upon a 9-month course of standard treatment with systemic chemotherapy, surgery and radiation therapy. The PPC team was actively involved in his care throughout treatment. Important life events and milestones were considered when planning for admissions for inpatient chemotherapy. When his clinical condition allowed, alterations were made in therapy schedules so he could participate in events such as middle school graduation.

Relapse and Continuation of Palliative Care.

During routine scan surveillance at 12 months after the end of his therapy, Ryan was noted to have relapsed disease with new masses found in his pelvis and lungs. Intensively timed chemotherapy was reinitiated with good response. Surgery was performed to remove the remaining pulmonary nodules, and chemotherapy finished after one year. Ryan was now 16 years old. The PPC team continued to be actively involved throughout Ryan’s relapse therapy, ensuring his quality of life remained central to his treatment.

Hospice and Concurrent Care

Hospice

The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) has defined hospice care as care provided to the patient with a terminal illness with less than 6 months to live.55 This care includes an interdisciplinary team approach to EOL care. Curative therapies are no longer the goal of care for patients seeking hospice, rather comfort-focused goals including symptom management and relief from psychosocial and spiritual suffering are emphasized.55 The AAP9 also emphasizes that EOL care should be aimed at relieving suffering, improving quality of life and facilitating decision making. The theme of quality of life and principles of palliative care are echoed throughout both organizations’ definitions and standards of hospice care.

Concurrent Care

In 2010, the United States’ Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Section 2302) made provisions for those less than 21 years of age with Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) within the last 6 months of life to continue to receive disease-directed therapies along with hospice care. Such an approach to care is referred to as “concurrent care”.56 The goal of concurrent care is to provide the full interdisciplinary, holistic team approach that hospice and palliative care afford, while allowing patients to receive disease-directed therapies. This approach provides patients and families with a means of hope, balancing treatment with quality of life.57 Concurrent care aims to reduce physical, psychological, and spiritual suffering; all of which are important aspects of both palliative and hospice care.

Pediatric patients receiving hospice and concurrent care must also have their developmental needs addressed. The use of Child Life Specialists as part of the interdisciplinary team is an important aspect in pediatric hospice and concurrent care. Recognizing and incorporating this into EOL care for children allows care to be more tailored to the patient and the family.58

Hospice and Concurrent Care in Practice

Patients with advanced cancer and their families often face the relatively mutually exclusive priorities of pursuing more cancer-directed therapy while also wishing to prioritize quality of life. Parents may cite several reasons to continue cancer-directed therapies in spite of advanced cancer. Such reasons include continued hope for cure, life-prolongation, relief of symptom burden, and fear of foregoing chemotherapy even when cure is not an option.59–61 Hope is commonly expressed by children and families in pediatric oncology and is often linked to an expectation of a favorable prognosis or cure.59,62,63 The object of a patient or family’s hope can change over the course of an illness and remain even at the EOL.64–66 Two categories of hope, future-oriented hope and present-oriented hope, have been described in parents of children with cancer. Future-oriented hope involves hope for a cure and treatment success, hope for a miracle, and hope for more quality time with the child. Present-oriented hope involves hope for each day and each moment and a hope for no pain and suffering.61 Parents often recognize their hope for a cure may differ from their expectations of what is likely to occur and are able to hold both hope for a cure and a hope for their child’s well-being and minimal suffering.59,61,63 Directly asking about this with a question such as “What are you hoping for today?” can be very useful.67 Understanding what is being hoped for by the family and nurturing hope rather than simply judging whether a hope is realistic or not can be a very empathetic approach.68

The availability of concurrent care may ease parental concern for choosing between their hope for cure in continued therapy and hope for their child’s minimal suffering and improved EOL care.57 With care coordination between the child’s pediatric specialists and hospice team, the patient can continue to pursue curative-based therapies while receiving home-based hospice support to address distressing symptoms while building rapport with the patient and family before EOL. Should the cancer not respond to therapy and symptoms worsen, hospice services are already in place and they can more easily transition to EOL care. Concurrent care allows for the greatest level of care and health of the child while minimizing suffering from physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual distress. In addition, it delivers emotional support to parents to avoid them making difficult decisions to forgo further therapies for their child while ensuring the child’s symptoms and quality of life are addressed.57

One of the greatest benefits of hospice is the ability to provide symptom management and emotional support to the patient and family in their home. This allows the patient to be with their loved ones in the surroundings they are most comfortable while ensuring their symptoms are well controlled, which allows them to better participate in activities they enjoy. When considering hospice enrollment, one must ensure that the goals of hospice align with the patient and family’s goals of care. Some families may wish to seek hospitalization if it is considered necessary for the child while others may state it is of great importance for them to remain at home and to avoid hospitalization, even if this results in a shortened life for the child. If a family prefers to seek inpatient admissions for most symptom management needs, the patient and family will fail to receive the full benefits of hospice care. In these situations, it may be appropriate for the patient to continue to receive curative treatments and symptom management with palliative care without enrolling in hospice care until the patient’s condition worsens. While concurrent care allows for the family to continue to pursue curative-based therapies, it is important to ensure the family’s goals of care align with the hospice care plan.

When establishing the patient and family’s goals of care, each patient and family should be approached with curiosity to truly understand what is important for the dying child and family. When English is not the primary language, an interpreter should be engaged to ensure that the patient and family understand their options and have the opportunity to discuss questions and process emotions. Language barriers that interfere with understanding have been demonstrated to contribute to parental sadness and distress long after their child’s death.69 Understanding family structure and the role of each family member can help guide EOL conversations. The nurse should inquire about cultural values and spiritual beliefs that may influence EOL decisions, preferences for care, and meaning-making activities or rituals that are important prior to death. Whenever possible, families should be encouraged to participate in healing practices or rituals that promote meaning at EOL (e.g., special cloths, herbs, prayers, chants, traditional healers, lighting candles, pouring holy water on bed, placing patient on the ground instead of in a bed, or using traditional healers). Finally, the child and family should be asked about the preferred location for the child’s death as this can vary among different cultures and religions. For example, in the Chinese culture, some believe death in the home is bad luck, while others believe one’s soul will be lost if a person dies in the hospital.70

Some families wish to remain home with hospice services, while others may wish to be admitted to a free-standing hospice facility, and yet others may wish to be admitted to the hospital for their EOL care.29 The availability of a free-standing hospice facility varies by geographic location and may not be available in many areas. A home death allows the child to remain in familiar surroundings, maintains a sense of normalcy, promotes autonomy and privacy, and allows for a greater sense of control.29 Yet, patients and families cite many reasons for not wishing to receive EOL care at home. Reasons include concern for the lasting impact on siblings, memory of the child’s death occurring in the family home, concern for being alone when the child dies, or fear of being unable to effectively manage the child’s symptoms to keep them comfortable.29,71

Some children find comfort in returning to the unit where their cancer care was provided, surrounded by the nurses and medical team who they know and trust. If the hospital is the preferred site of death, the child can continue to receive home-based hospice services to manage their symptoms with the plan to be admitted to the hospital as the child begins to transition to EOL. However, if the child dies before being transferred, hospice is available to provide support to the family and post-mortem care to the child. Patients and families may initially feel they wish to transfer to the hospital for EOL care as they are not yet familiar with their hospice team but may change their minds when the time approaches. Similar to introducing palliative care services early in the patient’s diagnosis, enrolling a patient into hospice when he or she becomes eligible allows time for the family and child to develop a relationship and trust with their hospice team.

Providing family-centered care that is culturally sensitive is integral to hospice and concurrent care, as services are provided to not only the child but also the family, addressing the needs of the child-family unit together. 56,70,72 Caring for the family extends beyond the child’s death and includes bereavement services for families. In addition, legacy building activities that include both the child and family can provide emotional comfort for the family following the child’s death. Such legacy building activities may include journals or drawings done by the child or handprints and footprints of the child, for the family to keep.58 Nurses can play an active role in encouraging legacy building activities and should collaborate with other members of the healthcare team including Child Life, Social Work, and/or Psychology to ensure that such activities are offered to children and their families.

Bereavement care is part of the continuum of palliative care. The needs of the family do not end when the child dies73–75 Providing support to families might include follow-up telephone calls from team members, support groups, counseling or arranging an annual “Day of Remembrance.” 76

Insurance regulations/billing/medication coverage

“Concurrent Care for Children” mandates that all US state Medicaid plans finance both curative and hospice services to children less than twenty-one years of age.77 To be eligible for concurrent care, a physician or advanced practice registered nurse must certify that the patient is within the last 6 months of life. Concurrent care for children is not available to those who are privately insured or those without insurance. In addition, concurrent care does not include children receiving EOL care in an acute care/inpatient setting, but is rather community or hospice-based.57 Despite concurrent care being enacted over a decade ago, its implementation into state Medicaid plans occurred from 2010 to 2017 with significant variability in how it was implemented from state to state. 56,77–79 Furthermore, it remains common for pediatric specialists and hospice clinicians to be unaware of concurrent hospice care.56 This provides an opportunity for oncology nurses to become knowledgeable about their state regulations and share their knowledge with patients, families, and other members of the healthcare team.

With concurrent care, a hospice provider is not responsible for the cost of “life-prolonging treatments, medications prescribed by non-hospice providers/subspecialists, or any aspect of the patient’s medical care plan that is focused on treating, modifying, or curing a medical condition (even if that medical condition is also the hospice-qualifying diagnosis).” 80 The hospice physician is responsible for identifying the hospice related and unrelated diagnoses as well as indications for current medications. Hospice is responsible for covering any medications needed to manage symptoms related to the hospice diagnosis and plan of care, such as analgesics, antiemetics, anxiolytics, and anti-constipation agents.78,80 Life-prolonging therapies and hospice services are billed and reimbursed separately to allow for concurrent services.80

In the United States, all children with a life expectancy of 6 months or less may enroll in hospice to receive family-centered care to assist with symptom management, psychosocial care, respite, and bereavement support, regardless of eligibility for concurrent care. Occasionally, private insurances will allow for some curative-based therapies to co-exist with hospice. It is important for the hospice agency to verify what therapies the patient’s insurance will cover in addition to hospice services. The hospice program is responsible for providing and billing the insurance provider for those medications aimed at managing symptoms such as analgesics, antiemetics, anxiolytics, and anti-constipation agents. Given the general uncertainty that remains with hospice services and availability of concurrent care, it is important for pediatric specialists and hospice agencies to collaborate and work with families to ensure appropriate services are available to the patient to avoid any issues with the patient’s payor source.

Clinical Vignette Continued

Ryan’s second relapse: Introduction of hospice and concurrent care.

Eight months after Ryan completed his relapse therapy, he was admitted for lower back pain and numbness and weakness in his lower extremities. Once admitted, he confided to the resident physician providing care to him that he had noted weakness and “clumsiness” for several weeks and feared relapse but didn’t want to worry his parents. He hid his symptoms from his parents. He also began to have difficulty urinating and completely emptying his bladder as well as constipation. Again, he chose not to tell his parents of these symptoms out of concern for their feelings. He did not want to cause them worry or stress.

Recognizing the distress Ryan was feeling, the nurse caring for him asked the Child Life Specialist to provide Ryan with additional emotional and social support. The resident shared Ryan’s new symptoms with the primary oncologist. A CT scan was ordered, which revealed widespread metastatic disease in his abdomen and lungs. A follow up PET scan showed multiple bones were also now involved. The oncologist shared this information with Ryan and his family with the PPC team present. The oncologist explained that given the presence of widespread relapsed disease, there were no options for curative therapy. Life expectancy was felt to be less than 6 months. Ryan and his family were devastated.

Palliative chemotherapy, Phase 1 therapy, and hospice care were discussed as potential therapeutic approaches. The family was adamant that hospice was “out of the question” because they “were not giving up,” and decided that Ryan would enroll on a Phase 1 Trial that involved a new oral agent that would be taken twice daily. The PPC team recognized that Ryan had Medicaid as a payor source, and discussed that Ryan was eligible for concurrent care. The PPC and oncology team explained that concurrent care allows Ryan to continue to receive disease-directed therapies, like the Phase 1 agent, while also getting the benefits associated with hospice care. The family and Ryan liked this idea, as neither were ready to “just give up,” yet they admitted the services offered by hospice including pain management, counseling, chaplaincy and spiritual care were important to them and allowed them to keep Ryan home as much as possible. The family felt that concurrent care allowed them to focus on Ryan’s quality of life while maintaining hope that continued therapy would offer Ryan more time and maybe even a miracle.

Disease and Symptom Progression.

Five months after Ryan was enrolled on the Phase 1 trial, he experienced significant progression of disease. During those 5 months, he enjoyed many periods of good pain control that allowed him to go on his “Make a Wish” trip and to travel to attend an out-of-state family reunion. He had a wonderful time with aunts, uncles, cousins, parents and siblings. His girlfriend of 2 years was also part of the trip. He even learned to drive a truck on the pastures at his uncle’s farm.

Upon his return from this trip, the pain increased, and his bowel and bladder symptoms and lower extremity weakness returned. Scans showed significant progression of disease. He was taken off the Phase 1 trial, and he and his family together decided to remain on hospice care and not pursue additional disease-directed treatments. They were guided in this decision-making process by their primary oncology team and the PPC team. They felt comfortable with their decision and expressed relief that Ryan would remain in the care of clinicians who had cared for him from the beginning. Two weeks after stopping Phase 1 therapy, Ryan died peacefully at home surrounded by his family. His family later remarked that the support they received throughout his care from both oncology and the PPC team had been instrumental in providing them with the confidence and peace they needed at this very difficult time. They appreciated the bereavement follow-up the PPC team offered to them, their other children, and even Ryan’s girlfriend.

Barriers to Accessing Pediatric Palliative and Hospice Care

While the number of palliative care programs in children’s hospitals in the United States has risen considerably over the past 20 years, barriers continue to limit access and expansion of PPC and hospice services. Dahlberg et al., 81 identified an insufficient number of programs and late referrals as the two most prominent factors impeding access to palliative care in the US. Most pediatric palliative care programs require a referral from the primary team, in this case, the primary oncology team, for patients to access palliative care services. The primary oncologist, therefore, serves as a gatekeeper, and may be unwilling to consult the palliative care team or a palliative care provider embedded within their program. In order to initiate referrals, pediatric oncologists must have an awareness of the benefits of palliative care and a willingness to discuss it with their patients and families.82 Although perceptions are changing, many providers still equate palliative care with hospice or EOL care, seeing it as an approach distinct from curative therapy, not recognizing the value of the extra layer of services that palliative care can provide. Unfortunately, when palliative care is introduced late in the illness trajectory, it reinforces to patients, parents and other members of the health care team that palliative care is reserved for patients with poor prognoses.

Another major barrier limiting the expansion of palliative care services is the lack of financial support. Despite an Institute of Medicine12 report from almost 20 years ago encouraging both private and public insurance plans to support and reimburse services provided as part of comprehensive models of palliative care, billing reimbursement remains limited. Further, benefits provided by state Medicaid and CHIPS programs and state-mandates for private insurance plans vary by region, making it difficult for families and healthcare clinicians alike to know what services are available to them.82 Thus, limited financial support restricts program development and the services that can be offered.

Most pediatric patients with cancer (52%) in the United States are covered by private, employer-sponsored health plans.83 These private health insurance plans are the least regulated and tend to cover the least amount of palliative services. While inpatient palliative care services are generally covered12, 82 outpatient services are covered on a limited basis. Typically, home health care services including nursing visits are included, but the number of visits may be capped.

Several barriers exist to children receiving hospice. First, an underestimation or even denial of the child’s prognosis can delay access to hospice care. Also, a lack of understanding of the availability or utility of concurrent care can also delay hospice referral when appropriate. Only 10% of dying children in the US receive hospice care, primarily through adult hospice organizations.84

A significant obstacle in obtaining quality pediatric hospice care is access to services.85 Hospices generally provide coverage to a particular area, and often designate coverage by county. However, many counties across the US might lack adequate hospice coverage, particularly for children.86,87 In 2015, the NHPCO reported that 78% of US hospices service pediatric patients, but less than 20% of the hospice programs offer formal pediatric hospice services with pediatric trained staff. These hospices report serving between 1 to 30 pediatric hospice patients per year.84,88

An additional barrier to providing care includes lack of adequately trained personnel. Kaye et al84 surveyed hospice nurses from three southern states (N = 551) and found that more than 85% of respondents cared for pediatric patients infrequently (i.e., several times a year, every couple of years, or never), and 77% reported a lack of formal training or resources in providing care to children in hospice. With limited exposure to pediatric patients and little training, hospice nurses reported a knowledge deficit in understanding pediatric pain and symptom management and how to address goals of care or EOL discussions with children and their families.84 In addition to lack of knowledge and training, due to the low number of pediatric hospice patients serviced, agencies may not always have pediatric equipment and supplies available.86 Therefore, due to inexperience and discomfort in caring for children along with an inability to provide appropriately sized equipment and supplies, hospices often decline services to infants and young children. Obtaining quality, age- and developmentally appropriate hospice care for children and families can be challenging. Pediatric oncology nurses can extend their expertise in pediatric oncology care to hospice providers to help support and guide them in their care of children with cancer while in hospice.

Implications for Practice, Education and Research

Nurses are well positioned to advocate for the early integration of palliative care into the care of pediatric oncology patients. Such an approach, whether administered by the primary oncology team or in collaboration with specialty palliative care services ensures that quality of life remains central and that goals of care are established and re-visited throughout the illness trajectory. As educators, nurses can work with patients and families to correct any myths or misperceptions about both palliative and hospice care, explaining how both can complement the care they are already receiving by their primary oncology team. When a child with cancer enters a more terminal phase, nurses can help parents understand the concept of concurrent care and explain the potential benefits of this approach. Finally, nurses can embrace palliative care principles and embed them into their own practice.

When considering palliative care, nurses must work with interdisciplinary team members to assess and identify the unique cultural, religious and spiritual needs of patients and families. Non-Western cultures such as indigenous or Eastern-oriented, may have very different expectations for communication, truth telling, co-management and other interactions. Therefore, individualizing care and determining how to best communicate with patients and their families is critical.89

In order to feel confident as an advocate for both palliative care and hospice care, nurses will require additional education and training. Recognizing this need, in 2016, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) partnered with the End-of-Life Nursing Consortium (ELNEC) to develop competencies and curricula related to palliative care for undergraduate nursing students.90 In 2019, similar competencies and curricula were developed for graduate level nursing students.91 Notably, these competencies have only recently been integrated into formal nursing education, leaving a large number of practicing nurses without such education. Fortunately, a number of other opportunities exist for nurses to enhance their knowledge and expertise related to both palliative care and hospice care. See Table 3 for a list of educational opportunities offered both in-person and online.92

Table 3:

Educational Opportunities Relevant to Pediatric Palliative Care

| In-Person Training | ||

| Title | Website | Description |

| Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care Program (EPEC) | https://www.bioethics.northwestern.edu/programs/epec/curricula/pediatrics.html | An annual offering of 23 core and 2 elective topics in pain and symptom management in pediatric palliative care taught as a combination of distance learning modules and in-person conference sessions. |

| End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium Pediatric Palliative Care Train-the-Trainer (ELNEC-PPC) | https://advancingexpertcare.org/elnec | Train-the-trainer format pediatric palliative care in-person curriculum for nurses. |

| Palliative Care Leadership Centers | https://www.capc.org/palliative-care-leadership-centers/ | A national initiative of the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) for year-long palliative care team mentoring with in-person visits, webinars, and virtual office hours. |

| Program in Palliative Care Education and Practice (PCEP) Pediatric Track | http://www.hms.harvard.edu/pallcare/PCEP/PCEP.htm | Week-long, in-person learning opportunities for clinician educators who wish to become expert in the practice and teaching of comprehensive pediatric palliative care. |

| Online Learning | ||

| Title | Website | Description |

| Association for Children with Life-Threatening or Terminal Conditions and Their Families (ACT) Professional Resources | http://www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk/professionals/resources | Downloadable symptom control guidelines, palliative care commissioning reports, and patient education pages. |

| The California State University Institute for Palliative Care | https://csupalliativecare.org/programs/pediatrics/ | Curriculum for preparing palliative care professionals to care for pediatric-age patients (adult to pediatric education prep). |

| Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) | https://www.capc.org/training/ | Online palliative modules to include programmatic development; team education; etc. |

| Certified Hospice and Palliative Pediatric Nurse Review Course | https://advancingexpertcare.org/ItemDetail?iProductCode=OC615&Category=COURSE&WebsiteKey=b1bae5a7-e24a-4d4c-a697-2303ec0b2a8d | Online review course includes nine modules designed to assist with preparation for the certification exam. Topics include life-threatening conditions in children, pain and symptom management, bereavement, professional issues, and more. |

| Courageous Parents Network | https://courageousparentsnetwork.org/ | Collection of family-centric interactive modules thematically searchable; provider portal contains meaningful topical education expertly prepared with patient- and family-centric focus. |

| International Children’s Palliative Care Network (ICPCN) E-Learning Programme | https://www.elearnicpcn.org/ | Online courses on pain assessment and management in children, childhood development, communicating with children, and pediatric grief and bereavement. |

| National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) Pediatric Palliative Care Webinar Series | http://ppcwebinars.org/ | Monthly webinar series to raise the visibility of pediatric palliative care and to build clinicians’ competencies and confidence in providing care to children. |

| NHPCO Concurrent Care for Children Implementation Toolkit | https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/CCCR_Toolkit.pdf | Toolkit that includes information about implementing section 2302 or expanding PPC services. |

| National Institute of Nursing Research Palliative Care for Children Palliative Care: Conversations Matter | https://www.ninr.nih.gov/newsandinformation/conversationsmatter#.VY6-pUay4nJ | Tools and resources to help clinicians discuss palliative care with pediatric patients and their families. |

| Palliative Care Online Journal Club | http://journalclub.pallcare.info/index.php? | Filtered and organized articles on palliative care for current, convenient browsing. |

| Stanford Palliative Care Training Portal | http://palliative.stanford.edu/ | Training portal on an array of topics from opioid conversion, dyspnea, clinical prognostication, and care transitions. |

| University of Washington Certificate in Palliative Care | https://www.pce.uw.edu/certificates/palliative-care | Three-course graduate certificate program, which provides the foundational skills for delivering integrated, person-centered palliative care using a team-based approach. |

| Vision of Hope | http://www.bioethicsinstitute.org/research/projects-2/hope | Disease-specific modules which integrate palliative care into pediatric chronic disease (include sickle cell and muscular dystrophy). |

| Vital Talk | http://vitaltalk.org | Learning modules with pearls and pitfall examples to foster medical professional’s comfort in discussing difficult topics with patients. |

The subspeciality of palliative care has grown exponentially over the past 20 years and continues to evolve. Great opportunity exists to investigate the benefits and gain greater clarity around which patients gain the most from these services and how these services are best applied. As more patients are routinely referred to palliative care, determining what services patients will need on an ongoing basis, who will be available to provide them and how this will be influenced by legislation and reimbursement will be critical. More work needs to be done identifying and defining outcomes unique to palliative care, which can clearly demonstrate the impact of these services. Additional evidence is needed to guide standards, models of care, and quality improvement projects aimed at improving the ways in which pediatric palliative care and hospice care are delivered to patients and families.

As the inclusion of palliative care becomes more common in the care of children with serious or life-threatening health conditions, the psychosocial experience of nurses caring for these children must be considered. These psychosocial experiences may intensify when caring for long-term patients that move to hospice or concurrent care as disease progresses. Nurses caring for patients at EOL often experience compassion fatigue. This phenomenon might ultimately lead to burnout arising from the physical and emotional toll nurses can experience in caring for these patients who often have complex physical, emotional and spiritual needs. Awareness, recognition and prevention are key to preventing professional burnout.93 Recognizing this need, some institutions have established programs including self-care retreats, mindfulness and resiliency workshops, and on-site Employee Assistance Program counseling programs to encourage and promote well-being and resiliency among staff.94,95 Self-care activities do not have to be time-consuming and can include just five minutes of stretching, listening to music, drawing, journaling, or walking.96 Nurses are encouraged to practice self-care and self-compassion, which might allow them to experience personal resiliency and to provide more authentic compassionate care.97

Conclusion

In summary, PPC has shown to be beneficial to pediatric patients with cancer and their families when utilized. Clinicians should aim to integrate palliative care principles into their practice, and when patients and families have more complex needs, specialty palliative care providers should be consulted. When pediatric patients with cancer face a terminal prognosis, stopping disease-directed therapies can be a difficult decision. Many patients and families are not ready to “give up” and want to pursue additional treatments and experimental therapies. Provisions in the ACA now allow patients with a terminal diagnosis, who have state-based insurance, to enroll in hospice care while still receiving disease-directed therapies. There are many benefits to PPC including improved communication, less fragmented care and a growing, robust evidence base. Pediatric oncology nurses must be knowledgeable about palliative care, so that they can advocate for and ensure that their patients and families receive holistic, patient and family-centered, goal-directed care.

Acknowledgments:

Received partial funding from the Stanford Nurse Alumnae during her Postdoctoral Fellowship in Palliative Care which occurred during the manuscript development.

This publication was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number UL1TR001436. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Childhood Cancers. American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-in-children/key-statistics.html. Published 2021. Accessed 1/1/2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Top Ten Leading Causes of Death in the U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/animated-leading-causes.html. Published 2021. Accessed 3/13/2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter BS, Levetown M, Friebert SE. Palliative Care for Infants, Children, and Adolescents: A Practical Handbook. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman A, Hain R, Liben S. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children. 1 ed: OUP Oxford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfe J, Hinds P, Sourkes B. Textbook of Interdisciplinary Pediatric Palliative Care E-Book: Expert Consult Premium Edition. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg AR, Dussel V, Kang T, et al. Psychological distress in parents of children with advanced cancer. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(6):537–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Definition of palliative care. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/palliative-care. Published 2021. Accessed February 7, 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant MM, Dean GE. Evolution of quality of life in oncology and oncology nursing. In: King CR, Hinds PS, eds. Quality of Life: From Nursing and Patient Perspectives. 3rd ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning LLC; 2011:570. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatric Palliative Care and Hospice Care Commitments, Guidelines, and Recommendations. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):966–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weaver MS, Heinze KE, Bell CJ, et al. Establishing psychosocial palliative care standards for children and adolescents with cancer and their families: An integrative review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(3):212–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weaver MS, Rosenberg AR, Tager J, Wichman CS, Wiener L. A Summary of Pediatric Palliative Care Team Structure and Services as Reported by Centers Caring for Children with Cancer. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(4):452–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Field MJ, Behrman RE. When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snaman J, McCarthy S, Wiener L, Wolfe J. Pediatric Palliative Care in Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(9):954–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brock KE, Snaman JM, Kaye EC, et al. Models of Pediatric Palliative Oncology Outpatient Care-Benefits, Challenges, and Opportunities. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(9):476–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brock KE, Allen KE, Falk E, et al. Association of a pediatric palliative oncology clinic on palliative care access, timing and location of care for children with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(4):1849–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feudtner C, Womer J, Augustin R, et al. Pediatric palliative care programs in children’s hospitals: a cross-sectional national survey. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaye EC, Snaman JM, Baker JN. Pediatric Palliative Oncology: Bridging Silos of Care Through an Embedded Model. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(24):2740–2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauman JR, Temel JS. The integration of early palliative care with oncology care: the time has come for a new tradition. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12(12):1763–1771; quiz 1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcus KL, Santos G, Ciapponi A, et al. Impact of Specialized Pediatric Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(2):339–364.e310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaye EC, Weaver MS, DeWitt LH, et al. The Impact of Specialty Palliative Care in Pediatric Oncology: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vern-Gross TZ, Lam CG, Graff Z, et al. Patterns of End-of-Life Care in Children With Advanced Solid Tumor Malignancies Enrolled on a Palliative Care Service. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(3):305–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snaman JM, Kaye EC, Lu JJ, Sykes A, Baker JN. Palliative Care Involvement Is Associated with Less Intensive End-of-Life Care in Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Patients. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(5):509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groh G, Borasio GD, Nickolay C, Bender HU, von Lüttichau I, Führer M. Specialized pediatric palliative home care: a prospective evaluation. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(12):1588–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolfe J, Hammel JF, Edwards KE, et al. Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1717–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snaman JM, Kaye EC, Levine DR, et al. Empowering Bereaved Parents Through the Development of a Comprehensive Bereavement Program. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(4):767–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng BT, Rost M, De Clercq E, Arnold L, Elger BS, Wangmo T. Palliative care initiation in pediatric oncology patients: A systematic review. Cancer Med. 2019;8(1):3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine DR, Mandrell BN, Sykes A, et al. Patients’ and Parents’ Needs, Attitudes, and Perceptions About Early Palliative Care Integration in Pediatric Oncology. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(9):1214–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kassam A, Skiadaresis J, Alexander S, Wolfe J. Parent and clinician preferences for location of end-of-life care: home, hospital or freestanding hospice? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(5):859–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sisk BA, Friedrich A, Blazin LJ, Baker JN, Mack JW, DuBois J. Communication in Pediatric Oncology: A Qualitative Study. Pediatrics. 2020;146(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1203–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen H. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(1):14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Contro NA, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen HJ. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1248–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snaman JM, Torres C, Duffy B, Levine DR, Gibson DV, Baker JN. Parental Perspectives of Communication at the End of Life at a Pediatric Oncology Institution. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(3):326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Back AL. Patient-Clinician Communication Issues in Palliative Care for Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(9):866–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon EJ, Daugherty CK. ‘Hitting you over the head’: oncologists’ disclosure of prognosis to advanced cancer patients. Bioethics. 2003;17(2):142–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sisk BA, Dobrozsi S, Mack JW. Teamwork in prognostic communication: Addressing bottlenecks and barriers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(5):e28192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Dorman NM, et al. Nomenclature for kidney function and disease: report of a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Consensus Conference. Kidney Int. 2020;97(6):1117–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(33):5265–5270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(35):5636–5642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Upshaw NC, Roche A, Gleditsch K, Connelly E, Wasilewski-Masker K, Brock KE. Palliative care considerations and practices for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(1):e28781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pyke-Grimm KA, Franck LS, Halpern-Felsher B, Goldsby RE, Rehm RS. Three Dimensions of Treatment Decision Making in Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hinds PS, Drew D, Oakes LL, et al. End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9146–9154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keim-Malpass J, Stegenga K, Loudin B, Kennedy C, Kools S. “It’s Back! My Remission Is Over”: Online Communication of Disease Progression Among Adolescents With Cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2016;33(3):209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mack JW, Fasciano KM, Block SD. Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients’ Experiences With Treatment Decision-making. Pediatrics. 2019;143(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller VA, Baker JN, Leek AC, et al. Adolescent perspectives on phase I cancer research. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(5):873–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weaver MS, Baker JN, Gattuso JS, Gibson DV, Sykes AD, Hinds PS. Adolescents’ preferences for treatment decisional involvement during their cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(24):4416–4424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friebert S, Grossoehme DH, Baker JN, et al. Congruence Gaps Between Adolescents With Cancer and Their Families Regarding Values, Goals, and Beliefs About End-of-Life Care. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e205424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lyon ME, Jacobs S, Briggs L, Cheng YI, Wang J. Family-centered advance care planning for teens with cancer. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(5):460–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wiener L, Ballard E, Brennan T, Battles H, Martinez P, Pao M. How I wish to be remembered: the use of an advance care planning document in adolescent and young adult populations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(10):1309–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lyon ME, Garvie PA, D’Angelo LJ, et al. Advance Care Planning and HIV Symptoms in Adolescence. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wishes Five. Five Wishes. Aging with Dignity. https://fivewishes.org/. Published 2021. Accessed 03/08/2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zadeh S, Pao M, Wiener L. Opening end-of-life discussions: how to introduce Voicing My CHOiCES™, an advance care planning guide for adolescents and young adults. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(3):591–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The Conversation Project. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. https://theconversationproject.org/. Published 2021. Accessed 3/13/2021, 2021.

- 55.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. National Hospice and Palliative Care-Hospice Care Overview for Professionals. National Hospitce and Palliative Care Organization. https://www.nhpco.org/hospice-care-overview/. Published 2021. Accessed 2/6/2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lindley LC, Keim-Malpass J, Svynarenko R, Cozad MJ, Mack JW, Hinds PS. Pediatric Concurrent Hospice Care: A Scoping Review and Directions for Future Nursing Research. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2020;22(3):238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mooney-Doyle K, Keim-Malpass J, Lindley LC. The ethics of concurrent care for children: A social justice perspective. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26(5):1518–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Basak RB, Momaya R, Guo J, Rathi P. Role of Child Life Specialists in Pediatric Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(4):735–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kamihara J, Nyborn JA, Olcese ME, Nickerson T, Mack JW. Parental hope for children with advanced cancer. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):868–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mack JW, Cronin AM, Uno H, et al. Unrealistic parental expectations for cure in poor-prognosis childhood cancer. Cancer. 2020;126(2):416–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sisk BA, Kang TI, Mack JW. Sources of parental hope in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(6):e26981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Conway MF, Pantaleao A, Popp JM. Parents’ Experience of Hope When Their Child Has Cancer: Perceived Meaning and the Influence of Health Care Professionals. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2017;34(6):427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cotter V, Foxwell A. The meaning of hope in the dying. In: Ferrell BR, Paice J, eds. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Nursing. 5th ed.: Oxford University Press; 2019:379–389. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hill DL, Nathanson PG, Carroll KW, Schall TE, Miller VA, Feudtner C. Changes in Parental Hopes for Seriously Ill Children. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hill DL, Nathanson PG, Fenderson RM, Carroll KW, Feudtner C. Parental Concordance Regarding Problems and Hopes for Seriously Ill Children: A Two-Year Cohort Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):911–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kaye EC, Kiefer A, Blazin L, Spraker-Perlman H, Clark L, Baker JN. Bereaved Parents, Hope, and Realism. Pediatrics. 2020;145(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rosenberg AR, Feudtner C. What else are you hoping for? Fostering hope in paediatric serious illness. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105(9):1004–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Feudtner C The breadth of hopes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(24):2306–2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davies B, Contro N, Larson J, Widger K. Culturally-sensitive information-sharing in pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e859–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wiener L, McConnell DG, Latella L, Ludi E. Cultural and religious considerations in pediatric palliative care. Palliat Support Care. 2013;11(1):47–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vickers JL, Carlisle C. Choices and control: parental experiences in pediatric terminal home care. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2000;17(1):12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cain CL, Surbone A, Elk R, Kagawa-Singer M. Culture and Palliative Care: Preferences, Communication, Meaning, and Mutual Decision Making. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(5):1408–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Snaman JM, Kaye EC, Torres C, Gibson DV, Baker JN. Helping parents live with the hole in their heart: The role of health care providers and institutions in the bereaved parents’ grief journeys. Cancer. 2016;122(17):2757–2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kreicbergs UC, Lannen P, Onelov E, Wolfe J. Parental grief after losing a child to cancer: impact of professional and social support on long-term outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(22):3307–3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rosenberg AR, Postier A, Osenga K, et al. Long-term psychosocial outcomes among bereaved siblings of children with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(1):55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McCarthy S, Pyke-Grimm KA, Feraco A. Oncological Illnesses. In: Wolfe J, Hinds PS, Sourkes B, eds. Textbook of Interdisciplinary Pediatric Palliative Care. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford Press, New York; 2021. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Laird J, Cozad MJ, Keim-Malpass J, Mack JW, Lindley LC. Variation In State Medicaid Implementation Of The ACA: The Case Of Concurrent Care For Children. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(10):1770–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lindley LC, Richar CS, Hoit T, Steinhorn DM. Cost of Pediatric Concurrent Hospice Care: An Economic Analysis of Relevant Cost Components, Review of the Literature, and Case Illustration. J Palliat Med. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lindley LC, Cozad MJ, Svynarenko R, Keim-Malpass J, Mack JW. A National Profile of Children Receiving Pediatric Concurrent Hospice Care, 2011 to 2013. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2021;23(00):00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Determination of Hospice Medication Coverage in Children. National Hospitce and Palliative Care Organization. https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/Medication_Flow_Chart.pdf. Published 2020. Updated 10/2020. Accessed 2/7/2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dalberg T, McNinch NL, Friebert S. Perceptions of barriers and facilitators to early integration of pediatric palliative care: A national survey of pediatric oncology providers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(6):e26996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haines ER, Frost AC, Kane HL, Rokoske FS. Barriers to accessing palliative care for pediatric patients with cancer: A review of the literature. Cancer. 2018;124(11):2278–2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee JM, Wang X, Ojha RP, Johnson KJ. The effect of health insurance on childhood cancer survival in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123(24):4878–4885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kaye EC, Gattas M, Kiefer A, et al. Provision of Palliative and Hospice Care to Children in the Community: A Population Study of Hospice Nurses. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(2):241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lindley LC, Shaw SL. Who are the children using hospice care? J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2014;19(4):308–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fernandez KS, Rogers D, Look LM, Antony R. Overcoming barriers to hospice care for children with cancer: Promoting active participation of the oncology team. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(29_suppl):131–131. [Google Scholar]

- 88.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO Facts and Figures: Pediatric Palliative and Hospice Care in America. National Hospitce and Palliative Care Organization. Published 2015. Accessed February 26, 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mack JW, Smith TJ. Reasons why physicians do not have discussions about poor prognosis, why it matters, and what can be improved. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(22):2715–2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ferrell B, Malloy P, Mazanec P, Virani R. CARES: AACN’s New Competencies and Recommendations for Educating Undergraduate Nursing Students to Improve Palliative Care. J Prof Nurs. 2016;32(5):327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Preparing Graduate Nursing Students to Ensure Quality Palliative Care for the Seriously Ill & Their Families. 2019.

- 92.Allison J, Weaver M. Integration of Pediatric Palliative Care-A Primary practice with Subspecialty Access. American Academy of Pediatrics, Secton on Hematology Oncology (SOHO) Newsletter. 2019(Fall 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mills J, Wand T, Fraser JA. Palliative care professionals’ care and compassion for self and others: a narrative review. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2017;23(5):219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Altounji D, Morgan H, Grover M, Daldumyan S, Secola R. A self-care retreat for pediatric hematology oncology nurses. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2013;30(1):18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Slater PJ, Edwards RM, Badat AA. Evaluation of a staff well-being program in a pediatric oncology, hematology, and palliative care services group. J Healthc Leadersh. 2018;10:67–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dickman E Practice these five self-care strategies in less than five minutes. ONS Voice. 2019. https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/practice-these-five-self-care-strategies-in-less-than-five-minutes. Published May 25, 2019. Accessed March 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Andrews H, Tierney S, Seers K. Needing permission: The experience of self-care and self-compassion in nursing: A constructivist grounded theory study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;101:103436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.National Quality Forum. A national framework and preferred practices for palliative and hospice care quality. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum Washington, DC; December, 2006. 2006. [Google Scholar]