Abstract

CRISPR screening, including CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and CRISPR-knockout (CRISPR-KO) screening, has become a powerful technology in the genetic screening of eukaryotes. In contrast with eukaryotes, CRISPR-KO screening has not yet been applied to functional genomics studies in bacteria. Here, we constructed genome-scale CRISPR-KO and also CRISPRi libraries in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). We first examined these libraries to identify genes essential for Mtb viability. Subsequent screening identified dozens of genes associated with resistance/susceptibility to the antitubercular drug bedaquiline (BDQ). Genetic and chemical validation of the screening results suggested that it provided a valuable resource to investigate mechanisms of action underlying the effects of BDQ and to identify chemical-genetic synergies that can be used to optimize tuberculosis therapy. In summary, our results demonstrate the potential for efficient genome-wide CRISPR-KO screening in bacteria and establish a combined CRISPR screening approach for high-throughput investigation of genetic and chemical-genetic interactions in Mtb.

Development of combined CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO screening provides a comprehensive functional genomics study platform in Mtb.

INTRODUCTION

A major task in biology is to define gene function and to identify genetic elements underlying certain biological processes. CRISPR-Cas systems constitute an innovative approach to determining the gene function on a genome-wide scale (1, 2). Pooled CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) screening has been widely used to predict gene fitness and screen diverse phenotypes in various microorganisms (3–10). Although powerful, CRISPRi has a polar effect on operonic downstream genes, and this method only performs well when single guide RNA (sgRNA) targets a nontemplate strand (3, 5). Available protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences in a small gene might be limited, hampering the ability of CRISPRi to investigate functional genomics in bacteria. CRISPR knockout (KO) introduces loss-of-function mutations into genomic DNA when sgRNA targets both template and nontemplate strands and thus overcomes the disadvantages of CRISPRi (11). Although CRISPR-KO screening has been widely applied to eukaryotes (1), it has never to our knowledge been applied to prokaryotes because of its low genome editing efficiency in these organisms (2).

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB), is estimated to infect 9.9 million persons and cause 1.3 million deaths in 2020 (12). Multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant TB continues to be a public health threat, posing a critical challenge to TB treatment and control worldwide (12). Although recently developed drugs such as bedaquiline (BDQ), pretomanid, and delamanid have been developed, the treatment of TB, especially drug-resistant TB, requires several months, and the overall rate of favorable outcomes in persons infected with MDR-TB remains unacceptably low (13). Thus, there is an urgent need to investigate the bacterial pathways that govern drug efficacy and pathogenicity in Mtb, leading to the development of alternative and improved treatment regimens. High-throughput identification of important genes involved in mycobacterial metabolic and cellular functions can provide perspectives for understanding bacterial pathogenicity and drug susceptibility. Recent work on the development of barcoded degron (14), transcriptional regulator-induced phenotype (TRIP) (15), and CRISPRi (16), as well as transposon sequencing (Tn-seq) (17), provides excellent platforms to quantify gene vulnerability, investigate chemical-genetic interactions, and identify genes responsible for Mtb pathogenicity and drug resistance (18–22).

We previously described the development of a highly efficient CRISPR-mediated genome editing tool in Mtb that is dependent on the nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) repair system and does not require a repair template (23), making it feasible to generate genome mutant libraries for CRISPR-KO screening. The present study describes the development of a genome-scale Streptococcus thermophilus Cas9 (Cas9Sth1)–based functional genomic platform, combining CRISPR-KO and CRISPRi screening systems, that can be used for high-throughput loss-of-function screening in Mtb. This platform was used to investigate the genetic pathways that govern the efficacy of BDQ and to identify chemical-genetic synergies that can optimize the treatment of TB. These findings also provide a conceptual and technical framework for combined CRISPR screening in Mtb and other bacteria.

RESULTS

CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO, widely applied to functional genetic screening in various organisms, have individual advantages and limitations, suggesting that their combination may overcome their individual limitations. CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO using dCas9sth1 and Cas9sth1 have been developed in Mtb (16, 23). To comprehensively explore the biological processes in Mtb, we used them and constructed a CRISPRi and a CRISPR-KO library designed to target nearly all annotated Mtb genes with sgRNAs. This genome-scale sgRNA library consisted of 79,863 unique sgRNAs targeting random positions along the genome of Mtb strain H37Ra (24), in which 90% of the sgRNAs targeted annotated Mtb genes and 1272 sgRNAs were nontargeting control sgRNAs. This library, with an average coverage of 18 sgRNAs per gene, was synthesized on-chip and cloned into dCas9sth1-expressing (16) and Cas9sth1-expressing (23) integrated plasmids (fig. S1A).

Construction and validation of the CRISPRi library in Mtb

Mtb strain H37Ra was transformed with the CRISPRi sgRNA library, and the resulting bacteria were inoculated into 7H9 broth in the presence or absence of anhydrotetracycline (ATc) and grown for 18 generations. The fitness effect of each sgRNA was determined by analyzing the relative fold change in abundance (log2FC), as quantified by next-generation sequencing (NGS) of the library. In the presence of ATc, the fold-change distribution of sgRNAs targeting essential genes, but not nonessential genes and nontargeting controls, was significantly shifted (Fig. 1A). These findings were not observed in the absence of ATc, indicating that this ATc-inducible system was tightly regulated. Consistent with previous reports showing strand bias with dCas9 derived from other species (25), sgRNAs targeting essential genes with dCas9Sth1 showed, on average, a strong bias for the fitness effect when the nontemplate strand was targeted (fig. S1B) (25).

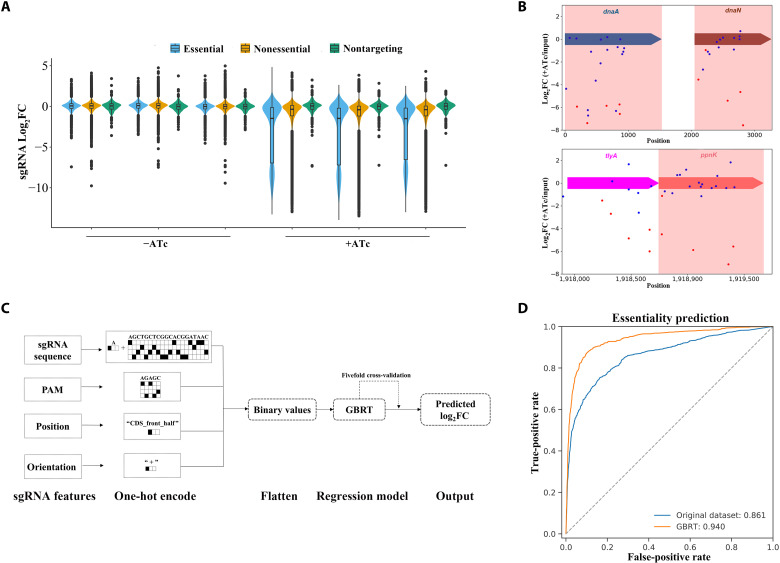

Fig. 1. Genome-scale CRISPRi screening for essential genes in Mtb.

(A) Violin plots showing log2FC distributions of sgRNAs targeting reference essential (blue) and nonessential (yellow) genes, as determined by Tn-seq, and of control nontargeting sgRNAs (green) from triplicate experiments. (B) Example of high variability in the effect of sgRNAs targeting the essential genes dnaA and dnaN and the tylA-ppnK operon. The dnaA, dnaN, and ppnK genes highlighted in red are essential. The sgRNAs selected after machine learning are shown in red. (C) Schematic flow of machine learning analysis. The features were converted to binary values by the one-hot encoding method. Eight varieties of machine models were tested, with the gradient boosting regression tree (GBRT) having the best performance among all models. (D) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves indicating the performance of chosen sgRNAs after machine learning in identifying essential genes. True-positive rates and false-positive rates were calculated relative to the standard set of essential and nonessential genes (27).

We then attempted to predict gene essentiality by the median log2FC for sgRNAs targeting the gene. Different sgRNAs targeting the same essential gene were found to differ in repression activity, and these effects were reproducible in three independent experiments (Fig. 1B), suggesting that some sgRNAs may have inherently poor repression activity due to a weak PAM, targeting of the template strand, or poor accessibility to the locus. Overdispersions resulting from these poor sgRNAs may influence the ability to predict the essential nature of a gene if the median value is directly calculated for all sgRNAs (see the examples of dnaA, dnaN, and ppnK in Fig. 1B). Thus, the best-performing sgRNAs were selected using machine learning approaches. The determinants of dCas9Sth1 activity were analyzed by calculating differences in log2FC values of sgRNAs that target essential genes. Subsequent prediction models were based on 458 essential genes shared by three Tn-seq studies (26–28). Eight traditional machine learning approaches with default hyperparameters were used to predict the log2FCs of sgRNAs, and the performance of each model was tested (29, 30) (Fig. 1C and fig. S1C). On the basis of the mean metrics of the test dataset by fivefold cross-validation, the gradient boosting regression tree (GBRT) model, which merged sgRNA sequence, PAM, position, and orientation, achieved the best generalization ability (Fig. 1C; fig. S1, C to E; and table S1). Application of this model to predict the log2FC for all sgRNAs in the dataset enabled the extraction of the five highest-ranked sgRNAs per gene for candidates to predict gene essentiality (table S2). The genes exceeding both thresholds (log2FC < −3.8 and Padj < 0.05) were considered essential, thus yielding a total of 594 essential genes (tables S3 and S4). To assess the performance of this approach, it was compared with the essential gene set (625 essential genes) identified in Tn-seq studies (27) as the standard method. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses showed that the areas under the curve (AUCs) for prediction of gene essentiality were 0.861 before and 0.940 after sgRNA selection (Fig. 1D), highlighting the benefits of machine learning.

Construction and validation of the CRISPR-KO library in Mtb

To construct a genome-scale CRISPR-KO library in Mtb, the sgRNA library was electroporated into Mtb strain H37Ra harboring the helper plasmid pNHEJ-recXmu-sacB (23). Approximately 3 million transformants were collected from three replicates and analyzed by NGS (Fig. 2A). Notably, the sgRNA counts for each gene across different replicates correlates well, indicating that the procedure of KO screening was sufficiently reliable (fig. S2). In contrast to CRISPRi screening, in which targeting the nontemplate strand resulted in greater gene repression (fig. S1B), the activities of sgRNAs targeting different DNA strands for Cas9 in KO libraries did not differ significantly (Fig. 2B). Most of the sgRNAs targeting nonessential genes, such as rv2826c and tlyA, were detected in the sequenced mutant library (Fig. 2C), whereas most sgRNAs targeting essential genes, such as rpsL, rpsG, and ppnK, were absent (Fig. 2C). CRISPR-KO screening results were further subjected to model-based analysis of genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 KO (MAGeCK) (31). Using MAGeCK with the robust rank algorithm (31), genes with log2FC lower than −4.5 and a false discovery rate (FDR) lower than 0.05 were considered essential, thus yielding a total of 704 essential genes (tables S3 and S4).

Fig. 2. Genome-scale CRISPR-KO screening for essential genes in Mtb.

(A) Schematic overview of the CRISPR-KO screening of essential genes in Mtb. The KO sgRNA library was built by cloning oligonucleotides into the Cas9sth1-expressing vector pYC1446 and using these plasmids to transform the Mtb strain H37Ra harboring the helper plasmid pNHEJ-recXmu-sacB. After 21 days of growth to allow for CRISPR-mediated gene KO, the transformants were collected, and the abundance of sgRNA barcodes in these cells was analyzed by NGS. (B) Comparisons of the fitness effect of sgRNAs targeting template (n = 33,402) and nontemplate (n = 34,429) strands in the gene-coding regions. (P = 0.817 by unpaired two-tailed t test). (C) Positions and read counts of sgRNAs targeting different genes are shown between the plasmid and KO libraries collected after transformation. The lengths of the vertical lines represent the normalized read counts of sgRNAs with a maximum log2 value of ~15, and the vertical lines on different sides of the horizontal line denote the sgRNAs targeting the nontemplate and template strands. (D) Venn diagram comparisons of essential genes screened by CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO in this study and in two previous studies (27, 32). ES, essential; NE, nonessential.

Performance comparison of CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO screening

Because CRISPRi has a polar effect on operonic downstream genes (3, 25), many nonessential genes, such as tlyA, were determined to be essential due to the presence of a downstream essential gene on CRISPRi screening (Fig. 1B and fig. S3A). In addition, several antitoxin genes, such as rv2827c, rv1044, and rv1990c, which are essential in the presence of toxin genes (27), were determined to be nonessential on CRISPRi screening due to the corepression of downstream toxin genes (Fig. 2C and fig. S3B). To disrupt a gene, CRISPR-KO usually causes the deletion of several base pairs (23) and thus might not have a polar effect and therefore can properly determine the essentiality of these genes (Fig. 2C and fig. S3). Mutation of a gene by CRISPR-KO usually leads to complete disruption of the gene’s function and might be more sensitive to affect bacterial growth. Thus, CRISPR-KO might recognize genes whose mutation strongly affects bacterial growth as essential (Fig. 2D and table S3). In addition, analysis of gene essentiality by CRISPRi involves comparing the sgRNA abundance before and after the induction of the CRISPR system in the CRISPRi library, while analysis of gene essentiality by CRISPR-KO involves comparing the sgRNA abundance in the plasmid library and Mtb CRISPR-KO library. Therefore, when coverage of the CRISPR library is limited, CRISPRi might recognize essential genes absent in the CRISPRi library as nonessential, while CRISPR-KO might recognize nonessential genes absent in the CRISPR-KO library as essential. Together, these results suggest that either CRISPRi or CRISPR-KO screening has shortcomings in determining Mtb gene essentiality.

The essential genes identified by CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO screenings were further compared with the essential genes identified by recent CRISPRi and Tn-seq studies (27, 32). Our results were generally consistent with those of the earlier studies, and we defined 593 genes appearing in at least three datasets as essential genes in Mtb strain H37Ra (Fig. 2D). Twelve essential genes identified in our screenings were not observed in the two previous datasets (Fig. 2D and table S3). Two of these genes, rv2204c and rv1248c (Fig. 2C and table S3), were also verified as essential in other studies (28, 33), whereas the remaining 10 genes were associated with differences in genetic backgrounds, methodology, or environmental conditions (i.e., media composition). Fourteen genes identified as essential in the two previous datasets were not observed in our screenings (Fig. 2D and table S3). Five of these genes were reported to be nonessential in several Tn-seq screening studies (26, 28, 34), indicating that these genes may also be nonessential in our tested conditions. The other nine genes had negative scores close to the threshold, but our stringent definition of essentiality likely missed several genes with moderate phenotypes. In addition, 29 genes were only determined by CRISPRi, not by CRISPR-KO and Tn-seq (Fig. 2D and table S3). Twenty-four of these genes are located upstream of an essential gene, and the CRISPRi essentiality call might result from a polar effect (table S3). Five of these genes lack surrounding essential genes. CRISPRi screenings were carried out using liquid medium (32), while CRISPR-KO and Tn-seq were carried out using solid medium (27). Thus, one possible explanation is that these genes might be essential in liquid medium, but not in solid medium. This still needs to be verified. Collectively, these results suggested that combinations of CRISPR screenings perform better than individual CRISPR screening on functional genomic studies in Mtb.

CRISPR screening identification of genes that determine BDQ efficacy in Mtb

BDQ is a recently developed antitubercular drug that inhibits adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) synthase of mycobacteria (35). To assess chemical-genetic interactions and identify additional drug targets that could improve the efficacy of chemotherapy, CRISPR screening was applied to Mtb to determine the gene patterns involved in intrinsic resistance and susceptibility of bacteria to BDQ. To mimic the Mtb status of “growth stasis” in vivo (36, 37), CRISPR-KO and CRISPRi libraries were grown to late-log phase. To profile genes related to both sensitivity and resistance, the libraries were treated with two different concentrations (250 and 1000 ng/ml) of BDQ for 6 days (Fig. 3A), resulting in ~40 to 60% and ~80 to 90% killing, respectively, relative to untreated control (Fig. 3B). The treated cells were washed and grown for 16 population doublings; their genomic DNA was extracted and subjected to NGS analysis of sgRNA abundance (Fig. 3A and fig. S4). The analysis showed that more hit genes were recovered in the genomes of bacteria treated with BDQ (1000 ng/ml than 250 ng/ml) by both CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO screening (tables S5 and S6) and that the changes in these hit genes were dose dependent (fig. S5). As expected, genes associated with BDQ resistance and susceptibility were observed (Fig. 3, C and D). For example, mmpS5-mmpL5 (rv0677c and rv0676c), which encodes a drug efflux system, was one of the most depleted genes (Fig. 3, C and D), whereas rv0678, encoding a transcriptional repressor of mmpSL5 and whose inactivation results in acquired resistance to BDQ (38), was the most enriched gene on both screenings (Fig. 3, C and D). These results suggest that CRISPR screening may be applicable to chemical-genetic interaction profiling.

Fig. 3. Application of CRISPR screenings to characterize gene-drug interactions.

(A) Experimental setup for CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO screenings to identify genes that alter BDQ efficacy. (B) Viability of the CRISPRi (gray) and CRISPR-KO (black) libraries after BDQ treatment for 6 days. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-tailed t tests for comparisons of BDQ with untreated controls. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; CFU, colony-forming units. (C and D) Volcano plots showing log2FC values and adjusted P value of each gene from the CRISPRi (C) and CRISPR-KO (D) libraries after treatment with BDQ (1000 ng/ml) in two replicates. Horizontal dashed line represents adjusted P value = 0.05. (E) Categorization of depleted and enriched hit genes from the CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO libraries treated with BDQ (1000 ng/ml) by physiological functions, as annotated in TubercuList (60).

One of the key advantages of CRISPRi is the ability to investigate the role of essential genes and can be used to determine the contribution of essential genes to synergistic antimicrobial effects. As expected, many essential genes, such as atpB, atpC, and atpH, which are involved in ATP synthesis, were recovered by CRISPRi but not by CRISPR-KO screening (Fig. 3C). Screening also identified pks13, which encodes the target of TAM16 and was reported to synergize with BDQ (Fig. 3C) (39), suggesting that these screening methods could be used to identify potential synergistic drug targets. In addition, BDQ treatment of bacteria resulted in the enrichment of several essential genes (Fig. 3C and table S5), indicating that these genes might be antagonistic drug targets of BDQ, which may provide important implications for TB therapeutics due to the reliance on multidrug regimens.

Compared with CRISPRi, during which incomplete knockdown results in the retention of gene function, CRISPR-KO disrupts gene function completely and is thought to be highly sensitive. As expected, many genes were identified in CRISPR-KO but not in CRISPRi screening (table S5). Several of these genes had been previously found by the Tn-seq method to be associated with intrinsic resistance/susceptibility to various antibiotics (table S5) (22). For example, lprG was identified on Tn-seq analysis as conferring intrinsic drug resistance, with disruption of this gene increasing susceptibility to vancomycin and rifampin (22). LprG, required for Mtb virulence, is involved in the transport of triacylglycerides and lipoarabinomannans required for correct biogenesis of the outer mycobacterial membrane (40). The increased drug susceptibility of the lprG mutant may result from elevated drug assimilation through a defective mycobacterial cell envelope. Reduced cell wall permeability is considered a main cause of intrinsic drug resistance in Mtb (41, 42). Furthermore, functional classification of BDQ resistance/susceptibility genes indicates that intrinsic resistance is largely determined by genes involved in cell wall synthesis and cell processes (Fig. 3E). To validate these screenings, several knockdown and KO mutants in Mtb strains H37Ra and H37Rv were constructed and their drug susceptibility was analyzed (Fig. 4). The minimum inhibitory concentration that inhibited bacterial growth by 50% (MIC50) and/or killing kinetics of these mutants generally matched the screening results (Fig. 4), confirming the accuracy of our screenings.

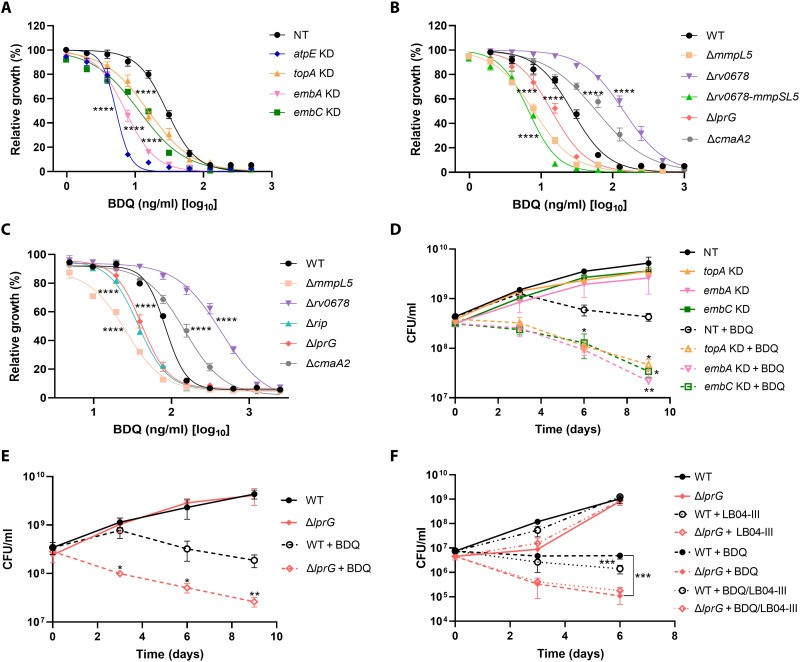

Fig. 4. Validation of genetic screening hits.

(A to C) Validation of screened genes with MIC measurements. MIC values for BDQ measured for H37Ra CRISPRi knockdown (KD) (A), CRISPR-KO (B) strains, and H37Rv CRISPR-KO strains (C). Data show the means ± SD of triplicate samples and are representative of at least two independent experiments. MIC50 was analyzed by nonlinear fit using GraphPad Prism 9.0. P values are relative to wild-type (WT) or NT controls as indicated. ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001. (D and E) Time kill assay of the indicated CRISPRi knockdown (D) and CRISPR-KO (E) strains with BDQ. CFU values were counted over a period of 9 days for untreated (solid lines) and BDQ-treated (1000 ng/ml; dashed lines) cultures of the indicated strains. (F) Effect of LB04-III (10 μM) on BDQ (50 ng/ml)–induced killing of indicated strains over 6 days. Bacterial viability was determined by counting the numbers of CFUs after plating bacteria on agar plates on days 3 and 6. NT corresponds to a CRISPRi strain harboring a nontargeting sgRNA. All data points shown in (D) to (F) represent the means ± SD of two biological replicates and are representative of at least two independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-tailed t tests, as compared between wild-type and mutant strains.

Mechanisms of action of genes associated with BDQ efficacy

Cells require certain ranges of intracellular ATP concentrations to maintain viability. BDQ functions as a bactericide in Mtb by reducing intracellular ATP below a certain threshold (35, 43). Thus, the uptake and efflux of BDQ were hypothesized to affect intracellular BDQ concentration, which modulates intracellular ATP concentration and ultimately affects cell killing. The mechanisms by which the screened genes affect drug resistance were first investigated by analyzing cell permeability using an ethidium bromide (EtBr) uptake assay. As expected, mutations of genes associated with the cell envelope, such as lprG and embA, increased the uptake of EtBr (Fig. 5A). Analysis of the effects of BDQ on intracellular ATP concentrations showed that, as expected, BDQ treatment was more effective at disrupting ATP homeostasis in strains with mutations in the efflux pump gene mmpL5 and in genes related to cell permeability (lprG or embA) than in the parental strain (Fig. 5, B and C). By contrast, strains with mutations in rv0678, resulting in high expression of the efflux pump, showed resistance to BDQ-induced disruption of ATP homeostasis (Fig. 5B). Unexpectedly, although the repression of Topoisomerase I (topA) did not affect the uptake of EtBr, the depletion of topA increased BDQ-associated sensitivity to disruption of ATP homeostasis, indicating that TopA may indirectly affect ATP consumption or production (Fig. 5, A and C).

Fig. 5. Investigation of the mechanisms of genes associated with BDQ efficacy.

(A) Uptake of EtBr by wild-type and ΔlprG, embA, and topA CRISPRi knockdown strains. (B) Bioluminescence measurements of ATP levels in the indicated knockout strains exposed to a range of BDQ concentrations for 24 hours. RLU, relative light unit. (C) Bioluminescence measurements of ATP levels in the indicated knockdown strains exposed to a range of BDQ concentrations for 24 hours. (D) Uptake of EtBr by Mtb pretreated with DMSO or subinhibitory EMB (312.5 ng/ml) or LB04-III (2.5 μM) for 3 days. (E) Effect of LB04-III (10 μM) or AMSA at 0.4× MIC50 (31.25 μM) on the dose range of BDQ-induced ATP depletion in Mtb. (F) Effect of EMB at 0.35× MIC50 (312.5 ng/ml) on the dose range of BDQ-induced ATP depletion in Mtb. All data points in (A) to (F) represent the means ± SD of triplicate samples and are representative of at least two independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test using GraphPad Prism 9.0. All P values are relative to controls as indicated. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. (G) Schematic diagram of the pathways affecting BDQ efficacy in Mtb. ADP, adenosine 5′-diphosphate; ATPase, adenosine triphosphatase.

These results were further validated chemically by focusing on three agents, LB04-III, ethambutol (EMB), and amsacrine (AMSA), which target LprG (44), EmbABC (45), and TopA (46, 47), respectively. Consistent with the genetic results, treatment of Mtb with LB04-III increased the uptake of EtBr and stimulated the ability of BDQ to disrupt ATP homeostasis (Fig. 5, D and E). Treatment with a high concentration (80 μM) of LB04-III slightly affected the MIC50 of BDQ (fig. S6A), while treatment with a low concentration (lower than 40 μM) of LB04-III did not significantly affect the MIC50 of BDQ (fig. S6, A and B). However, LB04-III potentiated the Mtb-killing efficacy of BDQ in an lprG-dependent manner (Fig. 4F and fig. S6, D and E). Treatment of Mtb with EMB increased cell permeability (Fig. 5D) but did not synergize with BDQ when the interaction of EMB and BDQ was evaluated by checkerboard assays (fig. S6, A and C). This may be due to an ATP increase in Mtb caused by EMB treatment, antagonizing BDQ-mediated ATP depletion (Fig. 5F), which, in turn, affects bacterial killing (fig. S6, D and E). Consistent with the genetic results, treatment of Mtb with AMSA, an inhibitor of TopA (47), enhanced the ability of BDQ to disrupt ATP homeostasis (Fig. 5E) and potentiated the effects of BDQ, as demonstrated by checkerboard and killing kinetics assays (fig. S6, A and D to F). In addition, AMSA was able to restore BDQ sensitivity to the BDQ-resistant Mtb (fig. S6G).

Despite targeting distinct cellular processes, the mechanisms of intrinsic resistance or sensitivity to drugs may be similar (21, 22). Recently, BDQ was combined with pretomanid and linezolid to treat patients with MDR-TB, resulting in successful outcomes in 90% of patients with drug-resistant TB with just 6 months of treatment (48). In addition, delamanid is another recently approved anti–MDR-TB drug (49). Thus, we investigated the effects of lprG, embA, and topA on the efficacy of pretomanid, linezolid, delamanid, and rifampicin. Mutation of lprG and depletion of embA decreased the MIC50 values of the tested drugs, whereas depletion of topA did not (fig. S7), indicating that the disturbance of cell envelope may affect the efficacy of many drugs. In addition, although pretomanid and delamanid have similar antimycobacterial mechanisms of action (49, 50), the mutation of lprG and depletion of embA had a stronger effect on the efficacy of delamanid than that of pretomanid (fig. S7, A and C), indicating that assimilation of these two drugs might be differentially regulated in Mtb.

DISCUSSION

The present study describes the construction of a CRISPR-KO library in bacteria and the development of a comprehensive functional genomics study platform consisting of a combination of CRISPR-KO and CRISPRi screening in Mtb. Tn-seq and CRISPR-KO usually generate similar results because the genes disrupted in both Tn and CRISPR-KO libraries were usually the same. However, unlike genes subjected to Tn insertion in Tn libraries, genes in CRISPR-KO libraries were usually subjected to the deletion of several base pairs. Deletion of 3N base pairs (bp) from a gene by CRISPR-KO may not completely abrogate its function but may decrease or increase its function, suggesting that CRISPR-KO could provide some unique information during screening. In addition, our combined technology has obvious advantages compared to CRISPRi and Tn-seq or their combination: (i) It would be convenient for a laboratory to use only CRISPR screening instead of two different methods, Tn-seq and CRISPRi. (ii) Compared to that of CRISPR-KO, the data collection for Tn-seq is much more complicated. The sgRNAs of CRISPR could easily be amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for NGS, while the genomic DNA for Tn-seq needs to be carefully digested and ligated before PCR amplification for NGS (51). (iii) The sgRNAs for CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO could be identical, which may reduce the cost to construct the sgRNA libraries. We predicted the essential genes in Mtb using this combined CRISPR screen, and the results showed high similarity with previous findings (27, 32), indicating its high performance. The combination of CRISPR-KO and CRISPRi screening can overcome the shortcomings of each and thus provide a powerful functional genomics tool for scalable and multiple investigations of biological processes in Mtb.

Although the current TB chemotherapies are effective, they require treatment for several months and have high rates of treatment failure. To improve TB chemotherapy, it is critical to identify more potent drug combinations by leveraging drug synergies. Combined CRISPR screens can generate more precise and complementary results for chemical-genetic profiling, as demonstrated by drawing a BDQ genetic map in Mtb. This map identified 142 genes that could influence the efficacy of BDQ (table S5). Recently, CRISPRi chemical genetics and comparative genomics identified more than 200 genes that could affect the potency of BDQ in Mtb (21). Only 44 of these genes were observed in both studies, whereas approximately 100 and 200 unique genes affecting BDQ efficacy, respectively, were identified (table S5) (21). In the study using CRISPRi screening, a sublethal concentration of BDQ was added to pre-log phase culture to quantify bacterial fitness (21), whereas, in the present study, high concentrations of BDQ (approximately 5× and 20× MIC50) were added to late-log phase culture to assess the bactericidal activities of BDQ (Fig. 3A). Thus, the present study could identify genes affecting the killing efficacy of BDQ at the late-log phase, whereas the previous study could identify genes affecting bacterial growth at log phase in the presence of BDQ. Depletion of topA only slightly decreased MIC but resulted in bacteria becoming strongly susceptible to BDQ in killing assays (Fig. 4, A and D), which might explain the reason that topA was identified in our screening but not in the previous study (table S5). Chemical-genetic screening under different conditions had provided unique and previously unidentified findings on drug-gene interactions in Mtb in previous studies (19, 52). Nevertheless, the BDQ genetic map based on our screening can provide a unique resource to investigate the molecular mechanisms that govern BDQ efficacy.

The resistance and susceptibility of BDQ might be affected by the following pathways (Fig. 5G): (i) F–adenosine triphosphatase, (ii) influx of BDQ, (iii) efflux of BDQ, (iv) cellular processes affecting ATP levels, and (v) ATP-dependent essential cellular pathways. Our results confirmed the previous finding that the efflux of BDQ is mainly dependent on the efflux pump MmpS5-MmpL5 (38). In addition, we genetically and chemically confirmed that lprG and topA, two of the screened genes, might modulate BDQ efficacy by regulation of cell permissibility and ATP homeostasis, respectively. Topoisomerase I, encoded by topA, acts to relax negative supercoils in DNA (53). TopA deficiency results in hypernegative DNA supercoiling, leading to formation of transcription-associated RNA-DNA hybrids (R-loops), which, in turn, causes aberrant constitutive stable DNA replication (cSDR) (53). cSDR or elimination of R-loops needs hydrolysis of ATP (54), which might explain why the mutation of topA affects ATP metabolism. Furthermore, screening in this study also identified several ATP-dependent enzymes, the depletion of which potentiated the efficacy of BDQ (table S5). These enzymes might be the secondary targets of BDQ due to the depleted ATP levels (55). The results of this study also confirmed that the cell envelope functions as a barrier to drug penetration in Mtb (41, 42). Thus, addition of a drug disrupting cell envelope to increase drug permeability might be used a general route to optimize TB treatment regimen. Last, many other previously unidentified genes were identified in this screen (table S5). Characterization of their mechanisms involved in affecting BDQ efficacy might help us to develop a combined treatment of drug-resistant TB with BDQ.

Similar to other pooled screening techniques, the CRISPR screening method described in this study had several limitations. First, this screening method could not assess effects in which the phenotype can be complemented in trans. For example, although the genes involved in the production of mycobactin are required for the growth of Mtb (56), they were not identified as essential genes in this or previous screenings. Second, the deletion or depletion of a target was not the same as its inhibition by a small molecule (57). For example, although the depletion of embA potentiated the efficacy of BDQ, EMB does not synergize with BDQ, suggesting the need to validate chemical-genetic interactions using specific inhibitors. Last, because of facility limitations, our screening was performed using the Mtb strain H37Ra. Screening results may differ in the Mtb strain H37Rv or in clinical strains. Validation of the screening results in the Mtb strain H37Rv yielded results similar to those in H37Ra, suggesting that screening results would be similar in H37Rv strain. Furthermore, the CRISPR screen method described in the present study could be easily performed in other Mtb strains.

In summary, this study used genome-scale CRISPR-KO and CRISPRi screening in the functional analysis of the Mtb genome. It demonstrates the power and feasibility of genome-wide CRISPR-KO screening and combined CRISPR screening in prokaryotes. This approach might be applicable to other bacteria, enabling the utilization of combined CRISPR screening as a powerful tool in bacterial genomics. CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO can yield complementary results and, when combined, can help to understand the molecular bases of fundamental biological questions in bacteria, as well as help to develop innovative drugs targeting bacterial pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and growth conditions

Mtb strains H37Ra and H37Rv and their derivatives used in this study were grown at 37°C in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco) supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80, 0.2% glycerol, and oleic acid–albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC; Becton Dickinson) or on 7H10 plates supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics, 0.5% glycerol, and OADC (Becton Dickinson). Where indicated, kanamycin (25 μg/ml), hygromycin (50 μg/ml), zeocin (50 μg/ml), and ATc (100 ng/ml) were added to the medium. Individual CRISPRi knockdown and CRISPR-KO strains were constructed as described previously (16, 23). Primers and sgRNAs used in this study are listed in table S7.

Library design and construction

The sgRNA library was designed to target random positions along the genome of Mtb strain H37Ra (NC_009525.1) with an appropriate PAM sequence. The scope of the PAM sequences of Cas9sth1 was extended to a cutoff score of greater than 6.7-fold repression listed in the previous study (16) to increase the frequency of possible targets throughout the H37Ra genome. The sgRNAs were chosen to target the nontemplate and template strands of open reading frames (ORFs), ribosomal RNAs, transfer RNAs, and noncoding RNAs. When targeting ORFs, the sgRNAs were designed within the first 50% of the coding sequence as much as possible. All sgRNAs had at least four mismatches with any other locus of the Mtb genome, and sgRNAs that contained ≥4-bp homopolymeric stretches of T and A nucleotides were removed. Each sgRNA sequence was designed to be 21 nucleotides (nt) in length. If the 5′ transcription initiating nucleotide was a “T” or “C,” it was replaced with an “A” nucleotide. A total of 79,863 sgRNAs were ultimately synthesized through on-chip oligo synthesis (EdiGene Inc.). The oligonucleotide library was then amplified and purified by gel extraction. The PCR products were cloned into Bsm BI–digested pLJR965 and pYC1446 by golden gate assembly to generate the CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO plasmid libraries, respectively (EdiGene Inc.).

CRISPRi library construction

The sgRNA library was independently transformed three times, providing three biological replicates. Competent cells were prepared and transformed as described previously (23). Briefly, H37Ra cells were grown in roller bottles (Greiner Bio-One, #681072) containing 200 ml of 7H9 medium at 37°C for 5 to 7 days. When the culture reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ~0.8, 20 ml of 15% sterilized glycine stock solution was added, yielding a final concentration of 1.5%, and the cultures were incubated in roller bottles at 37°C for an additional 20 to 24 hours. The cells were collected by centrifugation, washed three times at room temperature in 10% glycerol, and resuspended in 10 ml of 10% glycerol. The prepared competent cells were mixed with 200 ng of library plasmid per milliliter of competent cells, divided into 200-μl aliquots, and transferred to a 0.2-cm electrode gap electroporation cuvette (Bio-Rad, #1652082). Cells were electroporated using a Gene Pulser Xcell electroporation system (Bio-Rad, #1652660) at an optimized setting of 2.5 kV, 25 μF, and 1 kilohm. The cells were subsequently recovered in 50 ml of 7H9 broth supplemented with OADC and incubated for 24 hours. The recovered cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3000g for 10 min, resuspended in 10 ml of 7H9 medium, and spread onto 7H10 agar plates (15 cm by 15 cm) supplemented with kanamycin. After 18 days of outgrowth on plates, ~3 million colonies were collected each time and resuspended in 7H9 medium.

CRISPRi screening for essential genes

Approximately 3 × 108 cells were inoculated into 40 ml of 7H9 medium in a 75-cm2 flask (Corning #CLS430641) and grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 1.0. A 10-ml aliquot of culture, defined as generation 0, was collected for extraction of genomic DNA. Simultaneously, 3 ml of culture was added to 189 ml of 7H9 medium, with or without ATc, in roller bottles and cultured at 37°C with rolling (70 rpm). When the culture reached an OD600 of 1.0, 3 ml of culture was back-diluted and expanded for six generations. Bacterial pellets of generation 18 were harvested, and genomic DNA was extracted for subsequent analysis.

CRISPR-KO library construction and screening

Cells harboring pNHEJ-recX-sacB were grown in 400 ml of 7H9 medium supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80, 0.2% glycerol, OADC, and kanamycin (25 μg/ml) in roller bottles at 37°C for 5 to 7 days. Competent cells were prepared and transformed as described, with slight modifications (27). The recovered cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3000g for 10 min and spread onto 7H10 agar plates (15 cm by 15 cm) supplemented with kanamycin, zeocin, and ATc (100 ng/ml). After 21 days of growth, colonies were scraped from each plate with 7H9 medium and gently vortexed. Three independent KO libraries, each containing ~1 million transformants, were obtained. Aliquots containing 3 × 109 cells were collected each time for genomic DNA extraction and subsequent PCR and sequencing analyses. In CRISPR-KO screening to predict gene essentiality, sgRNA abundance was compared in transformants and in the KO plasmid library to define the fitness score. The quality of the KO library was tested by randomly picking 74 colonies on the plate; analyses detected 69 sgRNAs in the sgRNA library, with 63 sgRNAs targeting the H37Ra genome and six being nontargeting control sgRNAs. Of the 63 colonies with Mtb genome-targeting sgRNA, 54 were confirmed by PCR and sequencing analysis to be genome edited.

Machine learning approach for choosing good sgRNAs

Good sgRNAs of CRISPRi were screened using a machine learning approach with predefined features to predict the log2FCs of sgRNAs. Four single features of each sgRNA were chosen as machine learning input: sgRNA sequence, PAM, position, and orientation. The sgRNA targeting sequences were designed to be 21 nt, with the first nucleotide of each PAM distal being an “A” or “G,” making the initiation of transcription more efficient. Therefore, each sgRNA sequence had two predefined features, its first nucleotide and the other sequence. During preprocessing, the first nucleotide consisted of three situations, with C or T set to “A,” and “A” and “G” each remaining unchanged. PAM was a subsequence of 7 nt. Position referred to the three relative positions of each sgRNA in relation to its targeted gene in the genome; these positions included the front and rear halves of the gene and a sequence within 30 nt of the upstream region of the gene. Orientation indicated that the nontemplate or template strand was targeted. Each feature was represented by one-hot encoding as a matrix or array. In addition, after flattening a matrix to an array to improve the prediction performance, several single features were merged. The log2FCs of sgRNAs were predicted by applying eight well-established traditional machine learning regression models, such as linear regression, decision tree, support vector machine, k-nearest neighbors, random forest, AdaBoost, GBRT, and extremely randomized tree, to these features. All these methods were performed by fivefold cross-validation and evaluated by mean squared error (MSE) (Eq. 1), mean absolute error (MAE) (Eq. 2), and R2 (Eq. 3). The reported performance was averaged over the results of five implementations. Algorithms were implemented using the scikit-learn package (0.23.2) in Python 3.6.10 with default hyperparameters (loss: least squares regression, learning_rate: 0.1, n_estimators: 100, min_samples_split: 2, min_samples_leaf: 1, and max_depth: 3).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where n is the number of sgRNAs, yi is the true fitness of the ith sgRNA, is the predicted fitness of the ith sgRNA, and is the mean fitness of all sgRNAs.

BDQ selection of CRISPR libraries

Each CRISPRi or CRISPR-KO library stock containing ~3 × 108 cells was incubated in Middlebrook 7H9 medium for 5 days at 37°C to allow the library to recover. These recovered cultures were further diluted into 100 ml of 7H9 medium at a starting OD600 of 0.1, with ATc (100 ng/ml) added to the CRISPRi culture, and the cultures were grown to an OD600 of 1.0. Cultures were divided into three roller bottles, with one bottle each cultured with BDQ (250 ng/ml), BDQ (1000 ng/ml), or vehicle [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] for another 6 days. After selection, the cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80 and then grown for 16 population doublings. Each experiment was performed with two replicates.

Genomic DNA extraction and library preparation for Illumina sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from each sample using EZ-10 Spin Column Bacterial Genomic DNA Isolation kits (Sangon, #B610423) with a few modifications. Briefly, Mtb pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of GTE buffer [50 mM glucose, 25 mM tris-HCl (pH 8), and 10 mM EDTA] containing lysozyme (20 mg/ml) and incubated at 37°C overnight. To each sample was added 100 μl of SDS and 50 μl of proteinase K (10 mg/ml), and the samples were incubated at 55°C for 40 min. Each isolated genomic DNA sample was resuspended in ribonuclease-free water, and a ∼2-μl aliquot of each gDNA was electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels; its concentration was measured by NanoDrop and EtBr staining. Genomic DNA was used as a template for PCR amplification of the sgRNA-encoding region. Each 50 μl of reaction solution contained 50 ng of template and I-5 2X Hi-Fi PCR Master Mix (MCLAB), with eight reactions tested per library. The amplification conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 98°C for 2 min, followed by 18 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 10 s, annealing at 64°C for 15 s, extension at 72°C for 15 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The CRISPR-KO library was subjected to two-step PCR to amplify the sgRNA barcodes, as most escapers in genome editing were found to carry large fragment deletions in Sth1 Cas9. The first PCR amplified a 5000-bp fragment containing the most commonly retained Cas9 sequence and the sgRNA region. Each 25 μl of reaction solution contained 50 ng of template and DreamTaq Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #K1081), with eight reactions tested per library. The PCR cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, 25 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 62°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 3 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were subjected to 0.7% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction kits (QIAGEN, # 28706). In the second PCR amplification, the region of library sgRNAs was amplified. Each 50 μl of reaction solution contained 50 ng of DNA from the first PCR amplification and I-5 2X Hi-Fi PCR Master Mix (MCLAB), with eight reactions tested per PCR sample. The amplification conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 98°C for 2 min, 10 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 10 s, annealing at 64°C for 15 s, extension at 72°C for 15 s, and final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

The resulting 242-bp PCR fragments were sent to GENEWIZ Inc. (Suzhou, China) for amplicon sequencing. Briefly, the purified PCR fragments were treated with End Prep Mix for end repair, 5′ phosphorylation, and dA tailing in one reaction, followed by T-A ligation to add adaptors to both ends. The adaptor-ligated DNAs were purified using sample purification beads (SPBs) and PCR-amplified for eight cycles using P5 and P7 primers. The PCR products were cleaned up using SPBs, validated by Qsep100 (Bioptic, Taiwan, China), and quantified by Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Libraries with different indexes were multiplexed and loaded onto an Illumina NovaSeq instrument in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Sequencing was performed using a 2 × 150 paired-end configuration; image analysis and base calling were performed with HiSeq Control Software + OLB + GA Pipeline-1.6 (Illumina) on the HiSeq instrument. Approximately 10 to 20 million reads per library were collected.

NGS data analysis

Sequencing results were analyzed using the MAGeCK robust rank analysis method (version 0.5.9.4) (31). During CRISPRi screening to identify essential genes and during CRISPRi and CRISPR-KO screenings for BDQ selection, read counts were normalized relative to the reads of nontargeting control sgRNAs in each sample. During CRISPR-KO screening to identify essential genes, the sequence data were normalized relative to the total numbers of reads rather than to nontargeting sgRNAs, because the transformation process of sgRNAs targeting DNA sequences impedes cell growth due to the formation of on-target DSBs, regardless of the gene KO effects (58). For comparisons of enrichment or depletion, sgRNAs with fewer than 10 read counts in each control sample replicate were filtered out of the analysis. The MAGeCK gene summary output results can be found in tables S2 and S3.

ROC-AUC comparison of the performance of different methods

To compare the performance of different methods of identifying the essential genes, an optimized strategy (4) was applied, with each gene assigned a prediction score to indicate its essentiality. Equation 4 was applied to the raw CRISPRi data to determine the prediction score

| (4) |

where fitnessgene represents the median sgRNA fitness of each gene. Equation 5 was applied to the CRISPRi screening data after machine learning to convert the screening results into prediction scores for each gene

| (5) |

where FDRgene represents the output of MAGeCK. Two binary classifiers were trained on these three datasets, and ROC-AUC analysis was applied on the basis of the scikit-learn Python package, with essential genes determined by Tn-seq (27) regarded as the standard method.

MIC50 determination

The MICs of compounds against various Mtb strains were determined using the broth microdilution technique. Compounds dissolved in 90% DMSO were serially diluted twofold in 96-well clear plates (Falcon, #3072). An equal volume (100 μl) of Mtb culture (final OD600 of 0.025) was added to each well, and the assay plates were incubated at 37°C for 7 days. OD600 values were recorded using an EnVision multimode microplate reader (PerkinElmer), and MIC50 curves were plotted using GraphPad Prism 9 software. CRISPRi strains were growth-synchronized and predepleted in the presence of ATc (100 ng/ml) for 4 days before MIC analysis. For checkerboard assays, the drug interaction was quantified by the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) (59) using the equation

where CA is the concentration of drug A when combined with drug B yielding an isoeffective inhibition comparable with the MIC and CB is the concentration of drug B when combined with drug A yielding an isoeffective inhibition. Each MIC and checkerboard experiment was performed twice independently, with triplicate sample per experiment.

Quantitation of cellular ATP levels

The ATP content of bacterial cultures was quantified using BacTiter-Glo Microbial Cell Viability Assays (Promega, #G8230). Bacterial density was adjusted to an OD600 of 0.05, and drugs were subsequently added to the desired concentrations. After incubation for 24 hours, samples were mixed with a twofold volume of tris-EDTA reagent [100 mM tris and 4 mM EDTA (pH 7.75)] and incubated at 100°C for 5 min. The samples were centrifuged, and the supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes. Fifty microliters of each supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of BacTiter-Glo reagent for 5 min in the dark. Luminescence was measured using an EnVision multimode microplate reader (PerkinElmer).

Permeability assay

Cell envelope permeability was determined using the EtBr uptake assay as previously described (22). Briefly, Mtb strains were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 medium at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.6 to 0.8. The cultures were centrifuged at 3000g for 10 min, and the supernatants were discarded. The pellets were washed once in PBS with 0.05% Tween 80 and adjusted to an OD600 of 0.8 in PBS supplemented with 0.4% glucose. Aliquots of 100 μl of bacterial suspension were added to each well of a black 96-well plate (Costar), and an equal volume of EtBr (2 μg/ml) in PBS containing 0.4% glucose was added to each well. EtBr fluorescence was measured every 90 s for 60 min at 37°C in a multifunctional microplate reader (Tecan Infinite 200 PRO) at an excitation wavelength of 530 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm.

Bacterial killing assays

Two types of bacterial killing assays were performed. In the first method, bacterial cultures were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.05 and aliquoted into Erlenmeyer shaker flasks (Corning, #431143). Test compounds were dispensed into each flask. At the indicated time points, aliquots were withdrawn and plated on agar plates, which were incubated at 37°C for 3 weeks. Bacterial viability was determined by counting the numbers of colony-forming units. In the second method, the wild-type, CRISPRi, and CRISPR-KO mutant strains were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 medium at 37°C to an OD600 of 1.0. CRISPRi strains were pretreated with ATc (100 ng/ml) before drug exposure. BDQ was added to the cultures at a concentration of 1000 ng/ml, unless otherwise noted. At the indicated time points, samples were washed twice in PBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80, resuspended in 7H9 medium, and incubated for 4 days for recovery. Cultures were serially diluted and plated on 7H10 agar plates. The plates were incubated for 3 weeks at 37°C, and the numbers of colonies were counted.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by funding from the National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFA0907202), the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS2021-I2M-1-043), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82002179), the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (no. SZSM201911009), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7212070), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (3332021092), and the Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2020-RW310-001 and 2021-PT310-004).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Y.-C.S., M.-Y.Y., J.Y., and Q.J. Methodology: M.-Y.Y., S.-S.L., X.-P.G., and L.Z. Investigation: M.-Y.Y., S.-S.L., X.-Y.D., and C.-L.W. Visualization: M.-Y.Y. and D.Z. Supervision: Y.-C.S., J.Y., L.Z., and Q.J. Writing: Y.-C.S., M.-Y.Y., and D.Z.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Raw sequencing reads from CRISPR screens in this study have been deposited at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive with the accession code PRJNA803051.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S7

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Tables S1 to S7

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Shalem O., Sanjana N. E., Zhang F., High-throughput functional genomics using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16, 299–311 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rousset F., Bikard D., CRISPR screens in the era of microbiomes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 57, 70–77 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters J. M., Colavin A., Shi H., Czarny T. L., Larson M. H., Wong S., Hawkins J. S., Lu C. H. S., Koo B. M., Marta E., Shiver A. L., Whitehead E. H., Weissman J. S., Brown E. D., Qi L. S., Huang K. C., Gross C. A., A comprehensive, CRISPR-based functional analysis of essential genes in bacteria. Cell 165, 1493–1506 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang T., Guan C., Guo J., Liu B., Wu Y., Xie Z., Zhang C., Xing X. H., Pooled CRISPR interference screening enables genome-scale functional genomics study in bacteria with superior performance. Nat. Commun. 9, 2475 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rousset F., Cui L., Siouve E., Becavin C., Depardieu F., Bikard D., Genome-wide CRISPR-dCas9 screens in E. coli identify essential genes and phage host factors. PLOS Genet. 14, e1007749 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee H. H., Ostrov N., Wong B. G., Gold M. A., Khalil A. S., Church G. M., Functional genomics of the rapidly replicating bacterium Vibrio natriegens by CRISPRi. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1105–1113 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Wet T. J., Winkler K. R., Mhlanga M., Mizrahi V., Warner D. F., Arrayed CRISPRi and quantitative imaging describe the morphotypic landscape of essential mycobacterial genes. eLife 9, e60083 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X., Kimmey J. M., Matarazzo L., de Bakker V., Van Maele L., Sirard J. C., Nizet V., Veening J. W., Exploration of bacterial bottlenecks and Streptococcus pneumoniae pathogenesis by CRISPRi-Seq. Cell Host Microbe 29, 107–120.e6 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Todor H., Silvis M. R., Osadnik H., Gross C. A., Bacterial CRISPR screens for gene function. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 59, 102–109 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babunovic G. H., DeJesus M. A., Bosch B., Chase M. R., Barbier T., Dickey A. K., Bryson B. D., Rock J. M., Fortune S. M., CRISPR interference reveals that all- trans-retinoic acid promotes macrophage control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by limiting bacterial access to cholesterol and propionyl coenzyme A. mBio 13, e0368321 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shalem O., Sanjana N. E., Hartenian E., Shi X., Scott D. A., Mikkelson T., Heckl D., Ebert B. L., Root D. E., Doench J. G., Zhang F., Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science 343, 84–87 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization, Global Tuberculosis Report 2021 (World Health Organization, 2021); https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2021.

- 13.World Health Organization, Global Tuberculosis Report 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020); https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240013131.

- 14.Kim J. H., Wei J. R., Wallach J. B., Robbins R. S., Rubin E. J., Schnappinger D., Protein inactivation in mycobacteria by controlled proteolysis and its application to deplete the beta subunit of RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 2210–2220 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rustad T. R., Minch K. J., Ma S., Winkler J. K., Hobbs S., Hickey M., Brabant W., Turkarslan S., Price N. D., Baliga N. S., Sherman D. R., Mapping and manipulating the Mycobacterium tuberculosis transcriptome using a transcription factor overexpression-derived regulatory network. Genome Biol. 15, 502 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rock J. M., Hopkins F. F., Chavez A., Diallo M., Chase M. R., Gerrick E. R., Pritchard J. R., Church G. M., Rubin E. J., Sassetti C. M., Schnappinger D., Fortune S. M., Programmable transcriptional repression in mycobacteria using an orthogonal CRISPR interference platform. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16274 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sassetti C. M., Boyd D. H., Rubin E. J., Comprehensive identification of conditionally essential genes in mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12712–12717 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson E. O., LaVerriere E., Office E., Stanley M., Meyer E., Kawate T., Gomez J. E., Audette R. E., Bandyopadhyay N., Betancourt N., Delano K., Da Silva I., Davis J., Gallo C., Gardner M., Golas A. J., Guinn K. M., Kennedy S., Korn R., McConnell J. A., Moss C. E., Murphy K. C., Nietupski R. M., Papavinasasundaram K. G., Pinkham J. T., Pino P. A., Proulx M. K., Ruecker N., Song N., Thompson M., Trujillo C., Wakabayashi S., Wallach J. B., Watson C., Ioerger T. R., Lander E. S., Hubbard B. K., Serrano-Wu M. H., Ehrt S., Fitzgerald M., Rubin E. J., Sassetti C. M., Schnappinger D., Hung D. T., Large-scale chemical-genetics yields new M. tuberculosis inhibitor classes. Nature 571, 72–78 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh E. I., Oluoch P. O., Ruecker N., Proulx M. K., Soni V., Murphy K. C., Papavinasasundaram K., Reames C. J., Trujillo C., Zaveri A., Zimmerman M. D., Aslebagh R., Baker R. E., Shaffer S. A., Guinn K. M., Fitzgerald M., Dartois V., Ehrt S., Hung D. T., Ioerger T. R., Rubin E. J., Rhee K. Y., Schnappinger D., Sassetti C. M., Chemical-genetic interaction mapping links carbon metabolism and cell wall structure to tuberculosis drug efficacy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2201632119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma S., Morrison R., Hobbs S. J., Soni V., Farrow-Johnson J., Frando A., Fleck N., Grundner C., Rhee K. Y., Rustad T. R., Sherman D. R., Transcriptional regulator-induced phenotype screen reveals drug potentiators in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 44–50 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li S., Poulton N. C., Chang J. S., Azadian Z. A., DeJesus M. A., Ruecker N., Zimmerman M. D., Eckartt K. A., Bosch B., Engelhart C. A., Sullivan D. F., Gengenbacher M., Dartois V. A., Schnappinger D., Rock J. M., CRISPRi chemical genetics and comparative genomics identify genes mediating drug potency in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 766–779 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu W., DeJesus M. A., Rucker N., Engelhart C. A., Wright M. G., Healy C., Lin K., Wang R., Park S. W., Ioerger T. R., Schnappinger D., Ehrt S., Chemical genetic interaction profiling reveals determinants of intrinsic antibiotic resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan M. Y., Li S. S., Ding X. Y., Guo X. P., Jin Q., Sun Y. C., A CRISPR-assisted nonhomologous end-joining strategy for efficient genome editing in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. mBio 11, e02364-19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng H., Lu L., Wang B., Pu S., Zhang X., Zhu G., Shi W., Zhang L., Wang H., Wang S., Zhao G., Zhang Y., Genetic basis of virulence attenuation revealed by comparative genomic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Ra versus H37Rv. PLOS ONE 3, e2375 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qi L. S., Larson M. H., Gilbert L. A., Doudna J. A., Weissman J. S., Arkin A. P., Lim W. A., Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell 152, 1173–1183 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffin J. E., Gawronski J. D., DeJesus M. A., Ioerger T. R., Akerley B. J., Sassetti C. M., High-resolution phenotypic profiling defines genes essential for mycobacterial growth and cholesterol catabolism. PLOS Pathog. 7, e1002251 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeJesus M. A., Gerrick E. R., Xu W., Park S. W., Long J. E., Boutte C. C., Rubin E. J., Schnappinger D., Ehrt S., Fortune S. M., Sassetti C. M., Ioerger T. R., Comprehensive essentiality analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome via saturating transposon mutagenesis. mBio 8, e02133-16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minato Y., Gohl D. M., Thiede J. M., Chacon J. M., Harcombe W. R., Maruyama F., Baughn A. D., Genomewide assessment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis conditionally essential metabolic pathways. mSystems 4, e00070-19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo J., Wang T., Guan C., Liu B., Luo C., Xie Z., Zhang C., Xing X. H., Improved sgRNA design in bacteria via genome-wide activity profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 7052–7069 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodswen S. J., Barratt J. L. N., Kennedy P. J., Kaufer A., Calarco L., Ellis J. T., Machine learning and applications in microbiology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 45, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li W., Xu H., Xiao T., Cong L., Love M. I., Zhang F., Irizarry R. A., Liu J. S., Brown M., Liu X. S., MAGeCK enables robust identification of essential genes from genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens. Genome Biol. 15, 554 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bosch B., DeJesus M. A., Poulton N. C., Zhang W., Engelhart C. A., Zaveri A., Lavalette S., Ruecker N., Trujillo C., Wallach J. B., Li S., Ehrt S., Chait B. T., Schnappinger D., Rock J. M., Genome-wide gene expression tuning reveals diverse vulnerabilities of M. tuberculosis. Cell 184, 4579–4592.e24 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forti F., Mauri V., Deho G., Ghisotti D., Isolation of conditional expression mutants in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by transposon mutagenesis. Tuberculosis 91, 569–578 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sassetti C. M., Boyd D. H., Rubin E. J., Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 77–84 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andries K., Verhasselt P., Guillemont J., Gohlmann H. W., Neefs J. M., Winkler H., Van Gestel J., Timmerman P., Zhu M., Lee E., Williams P., de Chaffoy D., Huitric E., Hoffner S., Cambau E., Truffot-Pernot C., Lounis N., Jarlier V., A diarylquinoline drug active on the ATP synthase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 307, 223–227 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchison D. A., Coates A. R., Predictive in vitro models of the sterilizing activity of anti-tuberculosis drugs. Curr. Pharm. Des. 10, 3285–3295 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarathy J., Dartois V., Dick T., Gengenbacher M., Reduced drug uptake in phenotypically resistant nutrient-starved nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 1648–1653 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hartkoorn R. C., Uplekar S., Cole S. T., Cross-resistance between clofazimine and bedaquiline through upregulation of MmpL5 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemoter. 58, 2979–2981 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aggarwal A., Parai M. K., Shetty N., Wallis D., Woolhiser L., Hastings C., Dutta N. K., Galaviz S., Dhakal R. C., Shrestha R., Wakabayashi S., Walpole C., Matthews D., Floyd D., Scullion P., Riley J., Epemolu O., Norval S., Snavely T., Robertson G. T., Rubin E. J., Ioerger T. R., Sirgel F. A., van der Merwe R., van Helden P. D., Keller P., Bottger E. C., Karakousis P. C., Lenaerts A. J., Sacchettini J. C., Development of a novel lead that targets M. tuberculosis Polyketide Synthase 13. Cell 170, 249–259.e25 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaur R. L., Ren K., Blumenthal A., Bhamidi S., Gonzalez-Nilo F. D., Jackson M., Zare R. N., Ehrt S., Ernst J. D., Banaei N., LprG-mediated surface expression of lipoarabinomannan is essential for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLOS Pathog. 10, e1004376 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nasiri M. J., Haeili M., Ghazi M., Goudarzi H., Pormohammad A., Imani Fooladi A. A., Feizabadi M. M., New insights in to the intrinsic and acquired drug resistance mechanisms in Mycobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 8, 681 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dulberger C. L., Rubin E. J., Boutte C. C., The mycobacterial cell envelope—A moving target. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 47–59 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao S. P. S., Alonso S., Rand L., Dick T., Pethe K., The protonmotive force is required for maintaining ATP homeostasis and viability of hypoxic, nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 11945–11950 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bai L., Parkin L. A., Zhang H., Shum R., Previti M. L., Seeliger J. C., Dimethylaminophenyl hydrazides as inhibitors of the lipid transport protein LprG in Mycobacteria. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 637–648 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang L., Zhao Y., Gao Y., Wu L. J., Gao R. G., Zhang Q., Wang Y. N., Wu C. Y., Wu F. Y., Gurcha S. S., Veerapen N., Batt S. M., Zhao W., Qin L., Yang X. N., Wang M. F., Zhu Y., Zhang B., Bi L. J., Zhang X. E., Yang H. T., Guddat L. W., Xu W. Q., Wang Q., Li J., Besra G. S., Rao Z. H., Structures of cell wall arabinosyltransferases with the anti-tuberculosis drug ethambutol. Science 368, 1211–1219 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Godbole A. A., Ahmed W., Bhat R. S., Bradley E. K., Ekins S., Nagaraja V., Inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis topoisomerase I by m-AMSA, a eukaryotic type II topoisomerase poison. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 446, 916–920 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szafran M. J., Kolodziej M., Skut P., Medapi B., Domagala A., Trojanowski D., Zakrzewska-Czerwinska J., Sriram D., Jakimowicz D., Amsacrine derivatives selectively inhibit mycobacterial topoisomerase I (TopA), impair M. smegmatis growth and disturb chromosome replication. Front Microbiol. 9, 1592 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conradie F., Diacon A. H., Ngubane N., Howell P., Everitt D., Crook A. M., Mendel C. M., Egizi E., Moreira J., Timm J., McHugh T. D., Wills G. H., Bateson A., Hunt R., Van Niekerk C., Li M., Olugbosi M., Spigelman M.; Nix-TB Trial Team , Treatment of highly drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 893–902 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsumoto M., Hashizume H., Tomishige T., Kawasaki M., Tsubouchi H., Sasaki H., Shimokawa Y., Komatsu M., OPC-67683, a nitro-dihydro-imidazooxazole derivative with promising action against tuberculosis in vitro and in mice. PLoS Med. 3, e466 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh R., Manjunatha U., Boshoff H. I. M., Ha Y. H., Niyomrattanakit P., Ledwidge R., Dowd C. S., Lee I. Y., Kim P., Zhang L., Kang S., Keller T. H., Jiricek J., Barry C. E. III, PA-824 kills nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis by intracellular NO release. Science 322, 1392–1395 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cain A. K., Barquist L., Goodman A. L., Paulsen I. T., Parkhill J., van Opijnen T., A decade of advances in transposon-insertion sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 526–540 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kreutzfeldt K. M., Jansen R. S., Hartman T. E., Gouzy A., Wang R., Krieger I. V., Zimmerman M. D., Gengenbacher M., Sarathy J. P., Xie M., Dartois V., Sacchettini J. C., Rhee K. Y., Schnappinger D., Ehrt S., CinA mediates multidrug tolerance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 13, 2203 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen S. H., Chan N. L., Hsieh T. S., New mechanistic and functional insights into DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 139–170 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fukuoh A., Iwasaki H., Ishioka K., Shinagawa H., ATP-dependent resolution of R-loops at the ColE1 replication origin by Escherichia coli recG protein, a Holliday junction-specific helicase. EMBO J. 16, 203–209 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Z., Soni V., Marriner G., Kaneko T., Boshoff H. I. M., Barry C. E. III, Rhee K. Y., Mode-of-action profiling reveals glutamine synthetase as a collateral metabolic vulnerability of M. tuberculosis to bedaquiline. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 19646–19651 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reddy P. V., Puri R. V., Chauhan P., Kar R., Rohilla A., Khera A., Tyagi A. K., Disruption of mycobactin biosynthesis leads to attenuation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for growth and virulence. J. Infect. Dis. 208, 1255–1265 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Knight Z. A., Shokat K. M., Chemical genetics: Where genetics and pharmacology meet. Cell 128, 425–430 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen C. H., Xiao T., Xu H., Jiang P., Meyer C. A., Li W., Brown M., Liu X. S., Improved design and analysis of CRISPR knockout screens. Bioinformatics 34, 4095–4101 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ma S., Jaipalli S., Larkins-Ford J., Lohmiller J., Aldridge B. B., Sherman D. R., Chandrasekaran S., Transcriptomic signatures predict regulators of drug synergy and clinical regimen efficacy against tuberculosis. mBio 10, e02627–19 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lew J. M., Kapopoulou A., Jones L. M., Cole S. T., TubercuList—10 years after. Tuberculosis 91, 1–7 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S7

Tables S1 to S7