Abstract

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) occurs in up to 10%–30% of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. AKI patients who require renal replacement therapy (RRT) often have concurrent respiratory failure and represent a high-mortality-risk population. The authors sought to describe outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients with AKI requiring RRT and determine factors associated with poor outcomes.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study of hospitalized COVID-19 patients with AKI requiring RRT during the period from March 14, 2020, to September 30, 2020, was performed at Kaiser Permanente Southern California. RRT was defined as conventional hemodialysis and/or continuous renal replacement therapy. The primary outcome was hospitalization mortality, and secondary outcomes were mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support, and dialysis dependence among discharged patients. Hospitalization mortality risk ratios were estimated up to 30 days from RRT initiation.

Results

A total of 167 hospitalized COVID-19 patients were identified with AKI requiring RRT. The study population had a mean age of 60.7 years and included 71.3% male patients and 60.5% Hispanic patients. Overall, 114 (68.3%) patients died during their hospitalization. Among patients with baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) values of ≥ 60, 30–59, and < 30 mL/min, the mortality rates were 76.8%, 78.1%, and 50.0%, respectively. Among the 53 patients who survived to hospital discharge, 29 (54.7%) continued to require RRT. Compared to patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min, the adjusted 30-day hospitalization mortality risk ratios (95% CI) were 1.38 (0.90–2.12) and 1.54 (1.06–2.25) for eGFR values of 30–59 and ≥ 60, respectively.

Conclusion

Among a diverse cohort of hospitalized COVID-19 patients with AKI requiring RRT, survival to discharge was low. Greater mortality was observed among patients with higher baseline kidney function. Most of the patients discharged alive continued to be dialysis-dependent.

Keywords: COVID-19, acute kidney injury, mortality, dialysis/renal replacement therapy

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) and renal complications are highly prevalent in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with rates ranging from 10% to 28%. 1–3 Among COVID-19 patients who develop AKI, one in three patients require renal replacement therapy (RRT). 2,4

The pathophysiology of COVID-19–induced AKI is multifactorial, with direct and indirect effects on the kidney. 1,5 Direct kidney insults can result from renal tropism leading to collapsing glomerulopathy, endothelial damage, coagulopathy, and complement activation. More commonly, kidney injury in the form of acute tubular necrosis occurs more indirectly as a result of organ crosstalk from respiratory distress/hypoxia or cardiovascular compromise. Additionally, systemic processes resulting from systemic inflammatory response syndrome and volume depletion contribute to kidney injury.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also placed an enormous amount of stress on health care systems. 6 During COVID-19 surges, nephrologists were challenged into triaging and allocating RRT resources, including, at times, needing to limit dialysis prescriptions or contemplating whether to offer dialysis. Determining optimal management strategies for AKI patients and RRT approaches has been an evolving process. Identifying means to prognosticate and determine factors associated with poor outcomes would provide important insights into managing this resource-intensive population during a pandemic.

In this study, the authors sought to characterize the clinical characteristics and outcomes of a diverse cohort of hospitalized COVID-19 patients with AKI requiring RRT within a population in Southern California.

Methods

Study design and setting

A retrospective cohort study was performed within Kaiser Permanente Southern California. Kaiser Permanente Southern California is an integrated health care system with 15 medical centers and a large, racially and ethnically diverse membership population. 7

Study population

The study included adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) hospitalized with COVID-19 who developed AKI requiring RRT during the period from March 14, 2020, through September 30, 2020. COVID-19 was defined as a laboratory-confirmed reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction positive test that resulted 1 week prior to or within 1 week of hospitalization. RRT was defined as conventional hemodialysis, continuous RRT, or both. Patients with no documented laboratory confirmation of COVID-19 and patients who had end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) were excluded. ESKD was defined as those who were on RRT or had had a renal transplant prior to hospitalization as captured from the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Renal Business Group registry. This study was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California institutional review board and exempted from informed consent (IRB #036591).

Data collection and outcomes

Kaiser Permanente Southern California has a comprehensive electronic health records system from which all sociodemographic and clinical information was extracted. All data for this study were collected as part of routine clinical practice. The baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) for each patient was calculated from the most recent creatinine value within 7 days to 2 years prior to hospitalization using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. 8 The 2009 CKD-EPI equation has been used to report eGFR values at Kaiser Permanente Southern California since 2017 because of its better accuracy compared to the modification of diet in renal disease formula. 9

The primary outcome was all-cause hospitalization mortality, defined as death that occurred during the hospitalization course after initiation of RRT. Patients who were alive at discharge were considered as alive for all analyses. Secondary outcomes were need for mechanical ventilation, need for vasopressor support, and dependence on RRT for patients who survived to discharge. Additional secondary outcomes included hospitalization mortality at 14 and 30 days after initiation of RRT.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to compare characteristics of the cohort by mortality status during hospitalization. Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies (n) and percentages (%). Rates of hospitalization mortality, ventilator and vasopressor requirement, and RRT dependency among discharged survivors were determined. Subgroup analysis of hospitalization mortality by baseline eGFR was performed. To assess the association between hospitalization mortality and baseline eGFR, analyses were performed to estimate risk ratios (RRs) and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for 14- and 30-day hospitalization mortality using a Poisson regression model with a robust error variance after adjusting for age, sex, race, and ethnicity.

Results

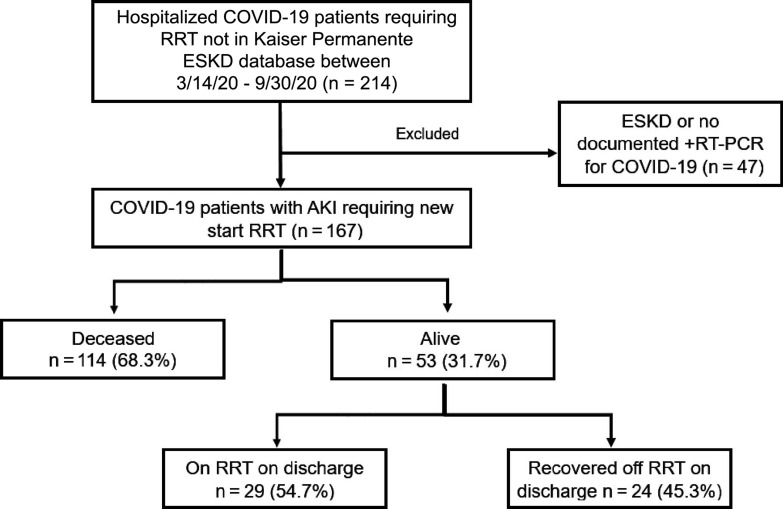

A total of 167 hospitalized COVID-19 patients with AKI requiring RRT were identified for our study (Figure 1). The population had a mean age of 60.7 years and included 71.3% male patients and 60.5% Hispanic patients (Table 1). The mean body mass index (BMI) was 34 ± 9.4 kg/m2, with hypertension (73.7%) and diabetes (54.5%) being the most frequent comorbidities (Table 1). A total of 114 (68%) patients died during hospitalization (Figure 1). Mechanical ventilation and vasopressor support were required in 152 (91%) patients and 147 (88%) patients, respectively. Among the 53 patients who were discharged alive, 29 (54.7%) continued to require outpatient RRT. Compared to the survivors, those who died during hospitalization were older (mean age: 61.7 vs 58.5 years) and had higher rates of coronary artery disease (9.6% vs 1.9%) and chronic liver disease (16.7% vs 5.7%).

Figure 1:

A total of 167 patients (age ≥ 18 years) hospitalized with COVID-19 who developed acute kidney injury (AKI) requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT) were identified during the period from March 14, 2020, through September 30, 2020. ESKD = end-stage kidney disease; RT-PCR = reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of COVID-19 patients with acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy

| Characteristic | All (N = 167) | Living (n = 53) | Deceased (n = 114) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60.7 (± 13.6) | 58.5 (± 13.2) | 61.7 (± 13.7) |

| Female sex | 48 (28.7%) | 15 (28.3%) | 33 (28.9%) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| White | 12 (7.2%) | 3 (5.7%) | 9 (7.9%) |

| Black | 23 (13.8%) | 9 (17%) | 14 (12.3%) |

| Hispanic | 101 (60.5%) | 32 (60.4%) | 69 (60.5%) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 22 (13.2%) | 7 (13.2%) | 15 (13.2%) |

| Other | 9 (5.4%) | 2 (3.8%) | 7 (6.1%) |

| Weight (kg) | 99.2 (± 31.4) | 101.2 (± 28.6) | 98.3 (± 32.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34 (± 9.4) | 33.3 (± 8.0) | 34.3 (± 10.0) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| None | 19 (11.4%) | 5 (9.4%) | 14 (12.3%) |

| Hypertension | 123 (73.7%) | 43 (81.1%) | 80 (70.2%) |

| Diabetes | 91 (54.5%) | 28 (52.8%) | 63 (55.3%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 12 (7.2%) | 1 (1.9%) | 11 (9.6%) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 9 (5.4%) | 2 (3.8%) | 7 (6.1%) |

| Lung disease | 22 (13.2%) | 3 (5.7%) | 19 (16.7%) |

| Liver disease | 5 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (4.4%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 10 (6%) | 3 (5.7%) | 7 (6.1%) |

| Smoking | 35 (21%) | 10 (18.9%) | 25 (21.9%) |

| Baseline eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | |||

| eGFR ≥ 60 | 56 (33.5%) | 13 (24.5%) | 43 (37.7%) |

| eGFR 30–59 | 32 (19.2%) | 7 (13.2%) | 25 (21.9%) |

| eGFR < 30 | 36 (21.6%) | 18 (34.0%) | 18 (15.8%) |

| Unknown | 43 (25.7%) | 15 (28.3%) | 28 (24.6%) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 152 (91%) | 38 (71.7%) | 114 (100%) |

| Vasopressor | 147 (88%) | 35 (66%) | 112 (98.2%) |

BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

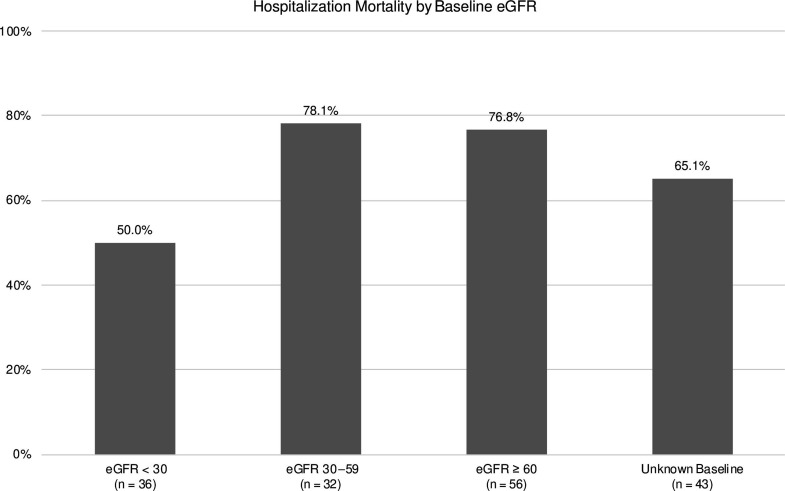

We compared outcomes among patients who had eGFR information available prior to hospitalization. Among those with available baseline eGFR values, 56 (33.5%), 32 (19.2%), and 36 (21.6%) patients had baseline eGFR values of ≥ 60, 30–59, and < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. The corresponding hospitalization mortality rates were 76.8%, 78.1%, and 50%, respectively (Figure 2). Among the 56 patients with eGFR≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, 56 (100%) required mechanical ventilation, and 53 (94.6%) required vasopressor support. Of the 32 patients with eGFR values of 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2, 32 (100%) required both mechanical support and vasopressor support. Among the 36 patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, 23 (63.9%) required mechanical ventilation and vasopressor support.

Figure 2:

Among COVID-19 patients who developed acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy for whom baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) information was available, hospitalization mortality rates were 76.8%, 78.1%, and 50% for patients with baseline eGFR values of ≥ 60, 30–59, and < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively.

Compared to patients with eGFR values of < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, the 14-day hospitalization mortality RRs were 1.76 (95% CI ,1.01–3.08) and 1.82 (95% CI, 1.11–3.05) for patients with baseline eGFR values of 30–59 and ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively, after adjusting for age, sex, race, and ethnicity. Similarly, the 30-day hospitalization mortality RRs were 1.38 (0.90–2.12) and 1.54 (95% CI, 1.06–2.25) for patients with baseline eGFR values of 30–59 and ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively, when compared to those with eGFR values of < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Table 2).

Table 2:

Hospitalization mortality risk ratios by baseline eGFR

| Baseline eGFR | Total | Mortality in 14 d | Mortality in 30 d | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events | RR (95% CI) | RR adjusted a | No. of events | RR (95% CI) | RR adjusted a | ||

| < 30 | 36 | 12 (33.3%) | Reference | 17 (47.2%) | Reference | ||

| 30–59 | 32 | 19 (59.4%) | 1.78 (1.03–3.07) | 1.76 (1.01–3.08) | 22 (68.8%) | 1.46 (0.96–2.21) | 1.38 (0.90–2.12) |

| ≥ 60 | 56 | 32 (57.1%) | 1.71 (1.02–2.87) | 1.84 (1.11–3.05) | 39 (69.6%) | 1.47 (1.00–2.17) | 1.54 (1.06–2.25) |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, and ethnicity.

CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; RR, risk ratio.

Discussion

Among a diverse cohort of hospitalized COVID-19 patients with AKI requiring RRT, we observed a high rate of inpatient mortality, which was consistent with previous observations. 1 The mortality rate among COVID-19 patients with AKI requiring RRT was even greater than that of hospitalized ESKD patients with COVID-19, for whom mortality rates up to 33% have been reported. 10 Overall, hospitalization mortality rates in COVID-19 patients with AKI requiring RRT are much greater than those in non-COVID patients with AKI requiring RRT, for whom rates up to 42% have been described. 11 Our findings suggest that COVID-19 patients who require RRT represent a severely ill population with overall poor prognosis.

Our study is one of the first to compare mortality using baseline eGFR values. In our study, we observed the lowest mortality rates among patients with baseline eGFR values of < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. This finding was surprising given that a recent meta-analysis found CKD, among other comorbidities, to result in an increased risk of hospitalization and mortality. 12 We believe that there is a plausible explanation. Rather than CKD being protective against mortality, we suspect that those with advanced kidney disease were progressed into dialsysis dependent ESKD after COVID-19 infection and may not necessarily reflect a high COVID-19 disease burden. An illustration of this effect is that, among the 18 patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 who survived to discharge, 15 patients remained on hemodialysis. Conversely, only 3 of the 24 patients who were off dialysis at discharge had baseline eGFR values of < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. This would mean that those who had higher baseline eGFR values had a greater likelihood to recover toward their own baseline, so that they would be further removed from dialysis dependence. On the other hand, those with closer-to-normal baseline kidney function likely had severe illness from COVID-19, which resulted in a larger decline in kidney function requiring RRT. Notably, more than half of patients discharged alive remained on outpatient RRT, which points toward the resource-intensive nature of the disease even beyond the immediate hospitalization. Further studies may be helpful to better understand long COVID outcomes in AKI dialysis patients .

Our study adds to the existing literature on the natural history of COVID-19. More importantly, our results lend important insights to better inform health care practitioners and patients in terms of prognostication and the role of therapies including support with RRT. Hospitalized COVID-19 patients have high mortality already given the high frequency of respiratory compromise and organ cross talk resulting in other organ failures. The majority (more than 70%) of our study population was male, which was consistent with previous observations demonstrating that male patients with COVID-19 fared more poorly than female patients. 13 We hope that these considerations can lead to better shared decision making discussions between health care practitioners and families, including difficult decisions such as not offering nonbeneficial care. Even in resource-rich countries, resources such as dialysis nurses, machines, and hours on dialysis may be better allocated toward patients with increased chances of survival during an unprecedented pandemic.

Potential limitations that may confound the interpretations of the findings include the fact that the study involved a modest sample size that captured outcomes early in the pandemic. The total mortality rate may have been undercaptured, as the authors evaluated hospitalization mortality only and did not further follow the patients discharged alive. For example, patients who were discharged alive but died outside the hospital would not have been included in the 30-day hospitalization mortality outcome. A previous study from Kaiser Permanente Southern California did demonstrate an extremely low rate of mortality (< 1%) among those who survived COVID-19 to discharge. 14 This study was also primarily descriptive and exploratory in nature. Thus, the authors were unable to account for heterogeneity in practice patterns by individual health care professionals. There may also be selection biases as a result of advanced kidney disease patients or sicker patients foregoing RRT and not being included in our cohort. By considering only patients who went on to RRT, the study cohort may may have represented patients who were deemed "salvageable" at the time of RRT initiation. The authors did not have information on patients who may have been deemed poor RRT candidates and were offered comfort measures only instead of RRT. Overall, the current study does not include enough analyses or a sufficient sample size to make firm determinations about resource allocations. Additional analysis to compare the cohort to a matched cohort without AKI and additional analysis to control for other markers of severe COVID-19 disease could have been helpful to support this discussion about resource allocation.

The strengths of this study include its use of a racially and ethnically diverse population within an integrated health care system allowing for comprehensive ascertainment of patient information including baseline characteristics and clinical follow-up.

Conclusion

Among COVID-19 patients hospitalized with AKI requiring RRT, hospitalization mortality was high (68.3%). The lowest mortality was observed among those who had baseline eGFR values of < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Patients with baseline eGFR values of ≥ 60 mL/min had a 50% greater 30-day hospitalization mortality risk. Among patients who survived to discharge, more than half continued to be dependent on dialysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Mark Rutkowski, Paul Saario, Noel Pascual, and the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Renal Business Group for their help and support with data acquisition and analysis.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Kevin C Kin, DO, participated in the study design, acquisition and analysis of data, and drafting and submission of the final manuscript. Madeleine Gysi, MD, participated in the study design, acquisition and analysis of data, and critical review and revision of the manuscript. Hui Zhou, PhD, participated in the data acquisition, analysis of data, and drafting of the final manuscript. Cheng-Wei Huang, MD, participated in the analysis of data and critical review and revision of the manuscript. David C Selevan, PMP, participated in the study design and acquisition of data. John J Sim, MD, participated in the study design, data analyses, and drafting of the final manuscript. All authors have given final approval to the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared

Funding: This study was funded by Kaiser Permanente Southern California Regional Research. This study was also supported by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Clinician Investigator Award (JJS).

References

- 1.Nadim MK,Forni LG,Mehta RL,et al. COVID-19-associated acute kidney injury: Consensus report of the 25th acute disease quality initiative (ADQI) workgroup.Nat Rev Nephrol.2020;16(12):747–764. 10.1038/s41581-020-00356-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silver SA,Beaubien-Souligny W,Shah PS,et al. The prevalence of acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis.Kidney Med.2021;3(1):83–98. 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu Z,Tang Y,Huang Q,et al. Systematic review and subgroup analysis of the incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients with COVID-19.BMC Nephrol.2021;22(1):52. 10.1186/s12882-021-02244-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X,Tian S,Guo H.Acute kidney injury and renal replacement therapy in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis.Int Immunopharmacol.2021;90:107159. 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Legrand M,Bell S,Forni L,et al. Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated acute kidney injury.Nat Rev Nephrol.2021;17(11):751–764. 10.1038/s41581-021-00452-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. World Health Organization Web site.Accessed 4 October 2021.https://covid19.who.int/

- 7.Koebnick C,Langer-Gould AM,Gould MK,et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: Comparison with US Census Bureau data.Perm J.2012;16(3):37–41. 10.7812/TPP/12-031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levey AS,Stevens LA,Schmid CH,et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate.Ann Intern Med.2009;150(9):604–612. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sim JJ,Batech M,Danforth KN,Rutkowski MP,Jacobsen SJ,Kanter MH. End-stage renal disease outcomes among the Kaiser Permanente Southern California creatinine safety program (Creatinine SureNet): Opportunities to reflect and improve.Perm J.2017;21:16–143. 10.7812/TPP/16-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sim JJ,Huang CW,Selevan DC,Chung J,Rutkowski MP,Zhou H. COVID-19 and survival in maintenance dialysis.Kidney Med.2021;3(1):132–135. 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lo LJ,Go AS,Chertow GM,et al. Dialysis-requiring acute renal failure increases the risk of progressive chronic kidney disease.Kidney Int.2009;76(8):893–899. 10.1038/ki.2009.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández Villalobos NV,Ott JJ,Klett-Tammen CJ,et al. Effect modification of the association between comorbidities and severe course of COVID-19 disease by age of study participants: A systematic review and meta-analysis.Syst Rev.2021;10(1):194. 10.1186/s13643-021-01732-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pradhan A,Olsson PE. Sex differences in severity and mortality from COVID-19: Are males more vulnerable? Biol Sex Differ.2020;11(1):53. 10.1186/s13293-020-00330-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang C-W,Desai PP,Wei KK,Liu I-LA,Lee JS,Nguyen HQ. Characteristics of patients discharged and readmitted after COVID-19 hospitalisation within a large integrated health system in the United States.Infect Dis (Lond).2021;53(10):800–804. 10.1080/23744235.2021.1924398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]