Abstract

Cutaneous lesions of the human sexually transmitted genital ulcer disease chancroid are characterized by the presence of intraepidermal pustules, keratinocyte cytopathology, and epidermal and dermal erosion. These lesions are replete with neutrophils, macrophages, and CD4+ T cells and contain very low numbers of cells of Haemophilus ducreyi, the bacterial agent of chancroid. We examined lesion formation by H. ducreyi in a pig model by using cyclophosphamide (CPA)-induced immune cell deficiency to distinguish between host and bacterial contributions to chancroid ulcer formation. Histologic presentation of H. ducreyi-induced lesions in CPA-treated pigs differed from ulcers that developed in immune-competent animals in that pustules did not form and surface epithelia remained intact. However, these lesions had significant suprabasal keratinocyte cytotoxicity. These results demonstrate that the host immune response was required for chancroid ulceration, while bacterial products were at least partially responsible for the keratinocyte cytopathology associated with chancroid lesions in the pig. The low numbers of H. ducreyi present in lesions in humans and immune-competent pigs have prevented localization of these organisms within skin. However, H. ducreyi organisms were readily visualized in lesion biopsies from infected CPA-treated pigs by immunoelectron microscopy. These bacteria were extracellular and associated with necrotic host cells in the epidermis and dermis. The relative abundance of H. ducreyi in inoculated CPA-treated pig skin suggests control of bacterial replication by host immune cells during natural human infection.

Chancroid is a sexually transmitted cutaneous genital ulcer disease caused by Haemophilus ducreyi (reviewed in references 6, 10, and 17). This disease is a serious public health concern in many tropical developing nations, where genital ulcerating diseases contribute significantly to the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (18).

Chancroid ulcers are characterized by surface pustules composed of neutrophils and necrotic debris, keratinocyte cytopathology, and dense dermal inflammatory infiltrates (2, 7, 14). Neutrophils, macrophages, and CD4+ T cells migrate to the site of H. ducreyi infection in a delayed-type hypersensitivity response involving predominantly Th1-type cytokines (7, 12, 13). Bacterial products that might play a role in chancroid ulceration include factors that cause cell damage in vitro, such as cytotoxin (1) and hemolysin (11), and factors that enable bacterial survival in chancroid animal models, including a hemoglobin-binding protein (15) and a periplasmic superoxide dismutase (our unpublished data). However, the unique interactions of bacterial molecules and elements of the host immune response that result in the characteristic histopathology of chancroid ulceration are not known.

Our laboratory has developed a juvenile pig model of chancroid that mimics human infection. H. ducreyi infection of pigs results in disease that resembles human chancroid from the development of ulcers histologically similar to chancroid in humans, with an immune cell infiltrate of neutrophils, macrophages, and T cells, to the lack of protective immunity (4). To determine the role of the host immune response in the histopathology and progression of chancroid, we examined the effect of immune cell deficiency on ulceration induced by H. ducreyi in the pig model of chancroid.

Histopathology of lesions induced by H. ducreyi in immune-competent and immune cell-deficient pigs.

To define the role of the host immune cells in chancroid pathology, we determined the effect of induced immune cell deficiency on ulcer formation caused by H. ducreyi in the pig model. Pigs were rendered immune cell deficient by intravenous administration of cyclophosphamide (CPA) (Mead Johnson, Princeton, N.J.) at 50 mg per kg 4 days preinoculation and 20 mg per kg every other day thereafter until the day of biopsy (8). Pigs treated with CPA showed a 76% reduction in total leukocyte numbers by the day of infection. Numbers of circulating polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils), lymphocytes, and monocytes all significantly decreased after administration of CPA (Table 1) [all P < 0.05 by t test]).

TABLE 1.

Effect of CPA on peripheral blood leukocyte numbers in pigs

| Circulating leukocyte type | No. of cells/mm3a

|

Mean % reductionb | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | +CPA | |||

| Neutrophils | 8,079 ± 1,518 | 1,101 ± 1,013 | 87 | 0.009 |

| Monocytes | 678 ± 179 | 6 ± 6 | 99 | 0.029 |

| Lymphocytes | 6,498 ± 941 | 3,360 ± 607 | 49 | 0.031 |

| Total | 15,425 ± 1,587 | 3,650 ± 777 | 76 | <0.001 |

Leukocyte numbers are presented as the mean ± standard error for four pigs. Baseline values were determined before treatment with CPA and 4 days prior to infection with H. ducreyi. Values for post-CPA administration were determined on the day of infection with H. ducreyi and 4 days after beginning CPA treatment.

% reduction = [(baseline − CPA)/baseline] × 100.

Pigs were inoculated on the ears with an estimated delivered dose of 104 CFU of H. ducreyi 35000 by using an allergen delivery device as previously described (4). H. ducreyi-infected sites and control sites inoculated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were biopsied on days 2 and 7 by using 6-mm skin punches (Acuderm, Ft. Lauderdale, Fla.). Samples for bright-field microscopy were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4°C, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Histopathology Reference Laboratory, Richmond, Calif.).

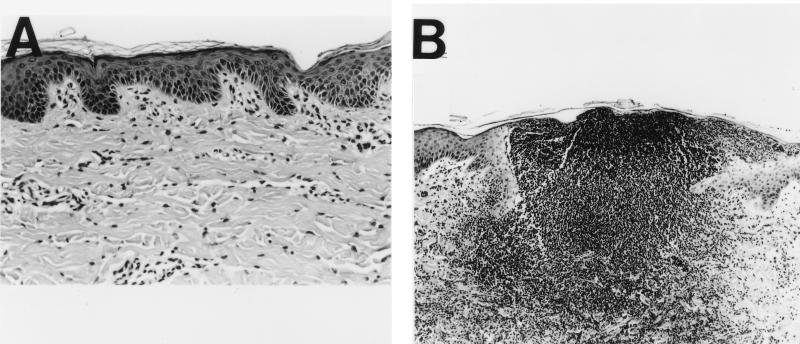

In response to H. ducreyi infection, immune-competent pigs developed skin lesions with the characteristic features of chancroid disease. In immune-competent pigs 2 and 7 days after inoculation, most H. ducreyi-infected sites showed surface micropustules consisting of neutrophils and tissue debris, complete erosion of the epidermis, ballooning and cytopathology of keratinocytes surrounding the micropustule, and near confluence of inflammatory cells in the dermis below the micropustule (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Hematoxylin-eosin-stained cross-sections of H. ducreyi-infected skin from immune-competent pigs. (A) Uninfected skin (actual magnification, ×105). (B) Day 2 after infection with H. ducreyi (×53). Cells in the ulcer with darkly staining nuclei are neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes.

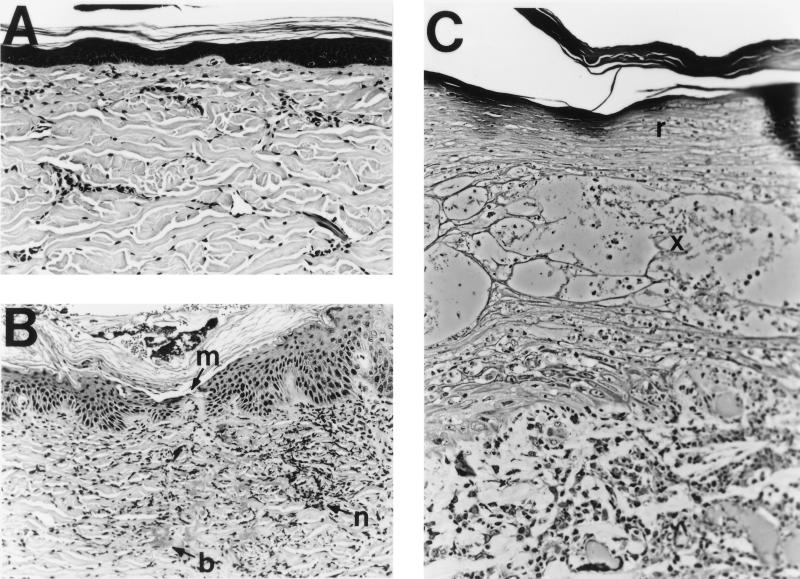

In contrast, a typical day 2 lesion from a CPA-treated pig had a mildly acanthotic but intact epidermis with a microbreak at the site of inoculation bordered by regenerative keratinocytes beginning to repair the microbreak. The dermis had large clumps of bacteria and degenerating neutrophils with pycnotic nuclei (Fig. 2B). Day 7 lesions were similar to day 2 lesions in that surface epithelia were fully intact (Fig. 2C). Epidermal erosion, a requirement for the transmission of HIV and H. ducreyi itself (5, 9, 18), did not develop in immune cell-deficient animals, suggesting that the host immune response is required for ulceration and, consequently, that host immune responses may play a role in the spread of chancroid, as well as HIV. The participation of the immune response in tissue injury has been observed in many other disease models. In one study, the elimination of circulating neutrophils in a guinea pig model of Pseudomonas-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome significantly diminished lung injury while stimulation with recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor significantly decreased survival (16).

FIG. 2.

Hematoxylin-eosin (A and B)- and toluidine blue (C)-stained cross-sections of ear skin from cyclophosphamide-treated pigs. (A) Uninfected skin (×53). (B) Day 2 after infection with H. ducreyi (×53). m, epidermal microbreak; n, degenerating neutrophils with pycnotic nuclei; b, bacterial colonies in the dermis. (C) Day 7 after infection with H. ducreyi (×105). r, regenerated surface layers of the epidermis; x, area wherein cell debris and edema replace the orderly strata of epidermal cells.

Death of epidermal keratinocytes in the spinous layer was evident in H. ducreyi-infected skin of CPA-treated pigs 7 days after inoculation (Fig. 2C), suggesting that some tissue damage may occur in the absence of a normal host immune response and as a direct result of the action of specific bacterial factors. H. ducreyi has been shown to cause cell death in vitro (3), through the actions of a secreted cytolethal distending toxin (1) and a surface-associated hemolysin (11).

Localization of H. ducreyi in infected pig skin.

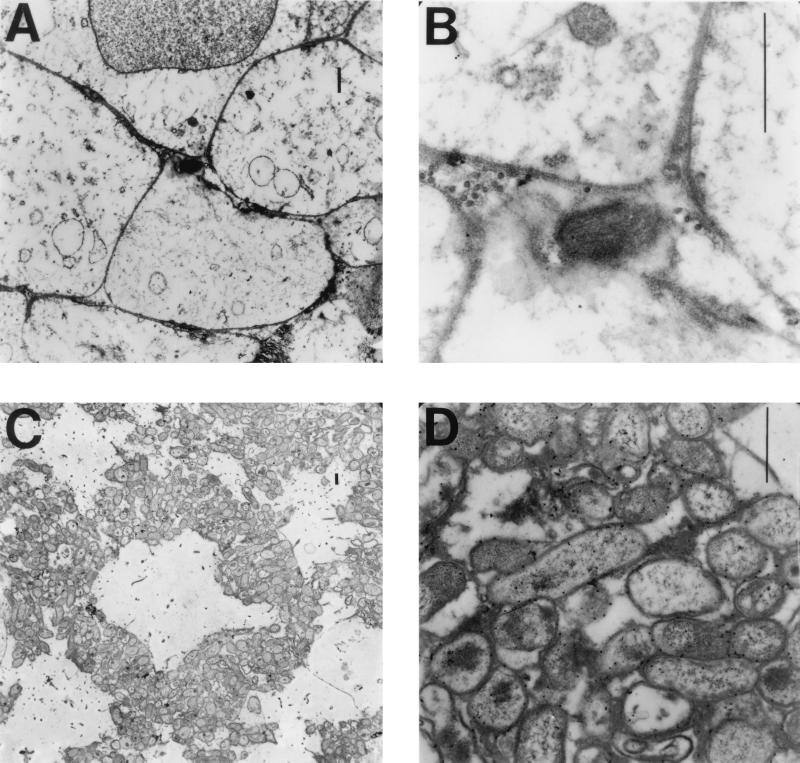

Although we consistently recovered viable H. ducreyi from infected immune-competent pigs, our attempts to localize bacteria in skin biopsies by using various stains and bright-field microscopy were unsuccessful. Other groups have experienced the same difficulty (12–14). Consequently, to localize H. ducreyi within infected pig skin, we used transmission electron microscopy (TEM). We surveyed ultrathin sections embedded in LR white on pioloform-treated nickel grids (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, Calif.) probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-H. ducreyi antiserum and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to 15-nm-diameter gold particles (3).

Visible H. ducreyi organisms were rare in immune-competent pigs, appearing as single cells within necrotic macrophages and granulocytes, amidst collagen fibers in the dermis, or between necrotic keratinocytes (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, H. ducreyi cells were readily visible by TEM in skin of infected immune cell-deficient pigs. Clumps of bacteria were visible predominantly in the dermis amidst host cell debris and extracellular matrix components and often surrounding or adjacent to host cell ghosts (Fig. 3C and D).

FIG. 3.

Electron micrographs of pig skin showing H. ducreyi labeled with gold particles. (A and B) H. ducreyi in the middle of necrotic pig skin cells at low magnification (A) and high magnification (B). (C and D) H. ducreyi microcolony surrounding a necrotic pig cell in a section from an infected neutropenic pig seen at low magnification (C) and at high magnification (D). Each bar = 1 μM.

We have determined that H. ducreyi numbers at an inoculated site 2 days postinoculation of a CPA-treated pig can be as much as 1 order of magnitude greater than the number in a similarly-infected site on an immune-competent pig (our unpublished data). The abundance of H. ducreyi cells in infected CPA-treated pigs and their relative rarity in immune-competent pigs provide evidence that neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages may control H. ducreyi growth and that the host immune response may play a role in the clearance of chancroid.

The immune cell-deficient pig model promises to be a valuable tool with which to study bacterial and host factors involved in chancroid pathogenesis. Engineered H. ducreyi variants with mutations in genes putatively involved in immune evasion and survival of host bactericidal mechanisms can be compared in immune-competent and CPA-treated pigs. The increased ability to visualize the infected site in CPA-treated pigs due to the absence of overwhelming numbers of immune cells could also be exploited for the analysis of cytopathic or cytotoxic effects of specific H. ducreyi gene products. The increasing availability of monoclonal antibodies to pig immune cells will also allow future studies involving the selective depletion of entire classes of immune cells or molecules to define the contributions of these factors to chancroid pathology and H. ducreyi clearance.

In summary, we have provided evidence that the host immune response to H. ducreyi infection is required for the development of chancroid ulcers and the associated loss of epidermal integrity necessary for H. ducreyi transmission. We have also observed keratinocyte cytopathology occurring largely in the absence of immune cells, suggesting that H. ducreyi may contribute to the tissue damage associated with chancroid. The immune cell-deficient pig model can be further used to dissect bacterial and host contributions to disease progression in chancroid.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants NIAID AI42824 (T.H.K.) and NRSA 1 F31 AI09565-01 (L.R.S.M.).

We gratefully acknowledge our collaborator, Glen Almond, for valuable advice on pigs; Patty Routh, John Horton, and Re Bai for technical assistance with the pigs; Stephen Knight for help with light micrography; Victoria Madden and Robert Bagnell for help with electron microscopy; John Woosley for help with dermatohistopathology; Janne Cannon for helpful discussions; and past and present members of the Kawula laboratory, particularly Marcia Hobbs, Franca Zaretzky, and Gina Donato, for practical and moral support. We are especially grateful to Myron Cohen for his idea to use induced neutropenia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cope L D, Lumbley S, Latimer J L, Klesney-Tait J, Stevens M K, Johnson L S, Purven M, Munson R S, Jr, Lagergard T, Radolf J D, Hansen E J. A diffusible cytotoxin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4056–4061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freinkel A L. Histological aspects of sexually transmitted genital lesions. Histopathology. 1987;11:819–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1987.tb01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobbs M M, Paul T R, Wyrick P B, Kawula T H. Haemophilus ducreyi infection causes basal keratinocyte cytotoxicity and elicits a unique cytokine induction pattern in an in vitro human skin model. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2914–2921. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2914-2921.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hobbs M M, San Mateo L R, Orndorff P E, Almond G, Kawula T H. Swine model of Haemophilus ducreyi infection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3094–3100. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3094-3100.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jessamine P G, Ronald A R. Chancroid and the role of genital ulcer disease in the spread of human retrovirus. Med Clin North Am. 1990;74:1417–1431. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30488-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordan W C. Chancroid: a review for the family practitioner. J Natl Med Assoc. 1991;83:724–726. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King R, Gough J, Ronald A, Nasio J, Ndinya-Achola J O, Plummer F, Wilkins J A. An immunohistochemical analysis of naturally occurring chancroid. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:427–430. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackie E J. Immunosuppressive effects of cyclophosphamide in pigs. Am J Vet Res. 1981;42:189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magro C M, Crowson A N, Alfa M, Nath A, Ronald A, Ndinya-Achola J O, Nasio J. A morphological study of penile chancroid lesions in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and -negative African men with a hypothesis concerning the role of chancroid in HIV transmission. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:1066–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90285-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morse S A. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:137–157. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmer K L, Goldman W E, Munson R S., Jr An isogenic haemolysin-deficient mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi lacks the ability to produce cytotoxic effects on human foreskin fibroblasts. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:13–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer K L, Schnizlein-Bick C T, Orazi A, John K, Chen C-Y, Hood A F, Spinola S M. The immune response to Haemophilus ducreyi resembles a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction throughout experimental infection of human subjects. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1688–1697. doi: 10.1086/314489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spinola S M, Orazi A, Arno J N, Fortney K, Kotylo P, Chen C-Y, Campagnari A A, Hood A F. Haemophilus ducreyi elicits a cutaneous infiltrate of CD4+ cells during experimental human infection. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:394–402. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spinola S M, Wild L M, Apicella M A, Gaspari A A, Campagnari A A. Experimental human infection with Haemophilus ducreyi. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1146–1150. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens M K, Porcella S, Klesney-Tait J, Lumbley S R, Thomas S E, Norgard M V, Radolf J D, Hansen E J. A hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein is involved in virulence expression by Haemophilus ducreyi in an animal model. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1724–1735. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1724-1735.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terashima T, Kanazawa M, Sayema K, Urano T, Sakamaki F, Nakamura H, Waki Y, Soejima K, Tasaka S, Ishizaka A. Neutrophil-induced lung protection and injury are dependent on the amount of Pseudomonas aeruginosa administered via airways in guinea pigs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:2150–2156. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trees D L, Morse S A. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi: an update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:357–375. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.3.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wasserheit J N. Epidemiological synergy. Interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]