Highlights

-

•

Most of the plans demonstrated political will, and described stakeholder involvement in the preparedness and response process.

-

•

No plan presented a clear description of the priority setting process, neither included a formal priority setting framework or criteria.

-

•

All plans described the need for key resources such as health human resources; medical equipment and supplies; laboratory equipment; and healthcare facilities.

-

•

There is room for incorporating lessons learnt in the SEARO planning for future public health emergencies.

Keywords: Priority setting, COVID, WHO- SEARO, Preparedness and response

Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization- South-East Asia Region (WHO-SEARO) accounted for almost 17% of all the confirmed cases and deaths of COVID-19 worldwide. While the literature has documented a weak COVID-19 response in the WHO-SEARO, there has been no discussion of the degree to which this could have been influenced/ mitigated with the integration of priority setting (PS) in the region’s COVID-19 response. The purpose of this paper is to describe the degree to which the COVID-19 plans from a sample of WHO-SEARO countries included priority setting.

Methods

The study was based on an analysis of national COVID-19 pandemic response and preparedness planning documents from a sample of seven (of the eleven) countries in WHO-SEARO. We described the degree to which the documented priority setting processes adhered to twenty established quality indicators of effective PS and conducted a cross-country comparison.

Results

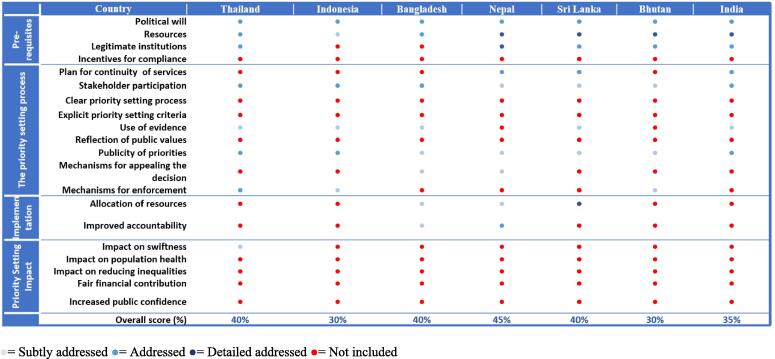

All of the reviewed plans described the required resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most, but not all of the plans demonstrated political will, and described stakeholder involvement. However, none of the plans presented a clear description of the PS process including a formal PS framework, and PS criteria. Overall, most of the plans included only a limited number of quality indicators for effective PS.

Discussion and conclusion

There was wide variation in the parameters of effective PS in the reviewed plans. However, there were no systematic variations between the parameters presented in the plans and the country’s economic, health system and pandemic and PS context and experiences. The political nature of the pandemic, and its high resource demands could have influenced the inclusion of the parameters that were apparent in all the plans. The finding that the plans did not include most of the evidence-based parameters of effective PS highlights the need for further research on how countries operationalize priority setting in their respective contexts as well as deeper understanding of the parameters that are deemed relevant. Further research should explore and describe the experiences of implementing defined priorities and the impact of this decision-making on the pandemic outcomes in each country.

1. Introduction

By July 18th, 2022, the World Health Organization- South-East Asia Region (WHO-SEARO1) accounted for 11.2 % of all the confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 11.9 % of the deaths worldwide [1]. This could in part be attributed to a couple of contextual factors. First, this region, which includes India, the country with the second largest population in the world, is very populous and accounts for one-fourth of the world́s population. Second, despite decades of economic growth and development in the region, most of the countries are still faced with high poverty levels, and a double burden of non-communicable (accounting for 29 % of Disability-adjusted life years -DALYs) and communicable diseases (accounting for 30 % of DALYs), having failed to eradicate vaccine-preventable diseases over the last several decades [2]. The region has been prone to emerging and re-emerging diseases such as avian flu, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and chikungunya [2]. Initial estimates placed South Asia2 at higher risk than observed for deaths and disaster because of the high population density, socio-economic vulnerabilities, high frequency of comorbidities, combined with a weaker health system infrastructure including limited human resources to support optimally effective responses [2], [3], [4], [5].

Several countries in the region have been recognized as being inadequately prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the Global Health Security Index (an indicator of the countries’ pandemic preparedness levels with the highest score at 100), India, with a score of 46.5, was deemed the best prepared country in the region [3]; however, this score is low compared to other countries outside the region, for example Australia or the USA (with a score of 71,1 and 75,9, respectively) [6]. The low global health security scores in the region have been attributed to various factors. These include a lack of robust national pandemic preparedness plans, guidelines or laws to support surveillance activities, and testing and control for diseases of public health concern [3]. However, it is becoming clear that this index was not very helpful in predicting COVID-19 pandemic preparedness [7], [8]. Various macro-level and national factors also influenced national pandemic preparedness [7]. Limited allocation of resources to health security in several countries [9]; shortage of health workers and field epidemiologists, and pre-existing social inequalities also influenced national COVID-19 preparedness [3], [10]. To make matters worse, the COVID-19 pandemic raised poverty levels in a region already plagued with high levels of inequities, a large informal economy, and low levels of social protections to offset interruptions to income generating activities [2], [3], [11], [12]. The complex disease burden, poverty and weak health infrastructure may have also influenced the quality of the COVID-19 response.

While the literature has documented a relatively “weak” COVID-19 pandemic response in SEARO [12], [13], [14], there has been limited discussion of how the countries planned to respond to the pandemic. Of specific interest to this paper, it is unclear if and how priority setting was included in the region’s COVID-19 response plans. Since systematic priority setting is thought to contribute to improving the quality of the resource allocation decisions, making them more evidence based, participatory and equitable. Understanding the role and use of PS in the planning process will support a richer understanding of the impact of the pandemic and pandemic control measures in each country,[15]. The purpose of this paper is to describe and assess the degree to which a sample of SEARO countries included priority setting in the national COVID-19 pandemic plans and glean insights for future pandemic planning in the region.

2. Methods

This paper reports from one strand of a study that sought to assess the degree to which countries from the six WHO regions included parameters of effective priority setting,(based on Kapiriri & Martin’s framework) in their COVID-19 pandemic planning process as evidenced in the pandemic plans, methods [15], [16].

For this study, we sampled seven of the eleven countries in WHO-SEARO. We sampled for maximum variation with respect to regional representation (South Asia and East Asia subregions), economic status (World Bank 2020–2021 country classification), type of political system (presidential republic, parliamentary republic, or monarchy), type of health system (public, private, mixed; with or without universal health coverage) and experiences with disease outbreaks and systematic priority setting.

We developed a search strategy to identify COVID-19 pandemic preparedness and response plans. Searches were carried out between August 2020 and July 2021 by two members of the research team. Since the retrieved COVID-19 plans did not describe the contexts in detail, the government webpages and the literature were used to obtain the additional information on the political, social and economic contexts of the sampled countries. Documents that were not written in English were reviewed by native language speakers to screen for relevant content, then relevant content was translated to English. Two researchers performed a preliminary scan of the translated documents to confirm their relevance and then extracted relevant data guided by an adapted version of Kapiriri and Martin’s framework [15], [16], [17]. This framework has five domains: the priority setting context; pre-requisites; the priority setting process; implementation; and outcomes and impact [15], [16], [17], [18]. Each of these five domains includes a varying number of parameters (the adapted version has a total of 20 across all domains) for determining the quality of priority setting for health. The final list of the quality parameters and a short explanation of how they were assessed in the retrieved plans is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Kapiriri & Martin’s Framework for assessing the quality of priority setting.

| Domain | Parameter | Short definition |

|---|---|---|

| Contextual Factors | Conducive Political, Economic, Social and cultural context | 1 Relevant contextual factors that may impact priority setting |

| Pre-requisites | Political will | Degree to which the government manifested support to tackle the pandemic e.g by assuming leadership in convening the COVID-19 response committees, supporting the development of the plans e.t.c. |

| Resources | Availability of a budget in the COVID plan, and clear description of resources available or required (including human resources, ICU beds and equipment, PPE, and other resources) | |

| Legitimate and credible institutions | Degree to which the priority setting institutions can set priorities, public confidence in the institution | |

| Incentives for compliance | Explicit description of material and financial incentives to comply with the pandemic plan | |

| The Priority setting process | Planning for continuity of care across the health systems | 2 Explicit mentions of the continuity of healthcare services during the pandemic |

| Stakeholder participation | Description of stakeholders participating in the development and implementation of the COVID plan | |

| Use of clear priority setting process/tool/methods | Documented priority setting process and/or use of priority setting framework | |

| Use of explicit relevant priority setting criteria | Documented/articulated criteria for the priority setting in the COVID plan | |

| Use of evidence | Explicit mention of the use of evidence to understand the context, the epidemiological situation, or to identify and assess possible interventions to be implemented | |

| Reflection of public values | Explicit mention that the public is represented, or that public values have been considered for the development or implementation of the plan | |

| Publicity of priorities and criteria | Evidence that the plan and criteria for priority-setting have been publicized and documents are openly accessible | |

| Functional mechanisms for appealing the decision | Description of mechanisms for appealing decisions related to the COVID plan, or evidence that the plan has been revised | |

| Functional mechanisms for enforcement the decision | Description of mechanisms for enforcing decisions related to the COVID plan | |

| Efficiency of the priority-setting process | 3 Proportion of meeting time spent on priority setting; number of decisions made on time | |

| Decreased dissentions | 3 Number of complaints from Stakeholder | |

| Implementation | Allocation of resources according to priorities | Degree of alignment of resource allocation and agreed upon priorities |

| Decreased resource wastage / misallocation | 3 Proportion of budget unused, drug stock-outs | |

| Improved internal accountability/reduced corruption | Description of mechanisms for improving the internal accountability or reduce corruption | |

| Increased stakeholder understanding, satisfaction and compliance with the Priority setting process | 3 Number of SH attending meetings, number of complaints from stakeholder, % stakeholder that can articulate the concepts used in priority setting and appreciate the need for priority setting | |

| Strengthening of the PS institution | 3 Indicators relating to increased efficiency, use of data, quality of decisions and appropriate resource allocation, % stakeholders with the capacity to set priorities | |

| Impact on institutional goals and objectives | 3 % of institutional objectives met that are attributed to the priority setting process | |

| Outcome/ Impact | Impact on swiftness of health policy and practice | Changes in health policy to reflect identified priorities, and swiftness of the pandemic response |

| Impact on population health | Description of the expected impact of the COVID plan on the population health | |

| Impact on reducing inequalities | Description of the expected impact of the COVID plan on reducing inequalities | |

| Fair financial contribution | Description of the expected impact of the COVID plan on fair financial contributions | |

| Increased public confidence in the health sector | Description of the expected impact of the COVID plan for increasing public confidence in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic | |

| Responsive health care system | 3 % reduction in DALYs, % reduction of the gap between the lower and upper quintiles, % of poor populations spending more than 50 % of their income on health care, % users who report satisfaction with the healthcare system | |

| Improved financial and political accountability | 3 Number of publicized financial resource allocation decisions, number of corruption instances reported, % of the public reporting satisfaction with the process | |

| Increased investment in the health sector and strengthening of the health care system | 3 Proportion increase in the health budget, proportion increase in the retention of health workers, % of the public reporting satisfaction with the health care system |

Following a pre-established approach [15], [16], [17], [18], the information extracted for each parameter was summarised by country. Further analysis involved synthesizing and comparing the findings by parameters across the sampled countries and a more detailed assessment of the content of each of the parameters was provided where the data were available (e.g. description of the stakeholder engagement process). Any similarities and differences across the countries were identified and described.

3. Results

Plans from seven (63 %) of the WHO-SEARO countries were retrieved and reviewed. Documents ranged from 32 to 89 pages (Indonesia and Bhutan, respectively) in length. The study sample included five countries defined as lower-middle-income countries by World Bank criteria, all of which were in the South Asia region (Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, India), and two countries defined as upper-middle-income in East Asia region (Thailand and Indonesia). All of the COVID-19 response and preparedness plans were retrieved from public websites and published between February and August 2020.

The rest of the results section is organized according to the five domains of priority setting, as identified in Kapiriri & Martin’s framework (see Fig. 1 for details of the assessment of each parameter in WHHO-SEARO plans).

Fig. 1.

Country performance on priority setting parameters according to the plans accessed.

3.1. Priority setting context

The political, social and economic context of the sampled countries is summarised in Table 2. Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal and Sri Lanka have parliamentary governments, Thailand is a constitutional monarchy, while India and Indonesia are presidential republics. The GINI index all the countries sampled is relatively high (over 37), but is higher in Bangladesh (51.4), India (47.9), and Thailand (43.7).3 All of the countries sampled have health systems with a mix of public and private financing, and an increasing participation of the private sector [19], [20]; only Nepal and Thailand are considered to have universal health coverage. Only Thailand has a long history of a systematic PS process [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24].

Table 2.

Priority setting context by country.

| Country | Economic System | Geographical Region | Political System | Health system Financing (Public, private, mixed) | Universal Health Coverage | UHC Service Coverage Index | GINI Index (2018) | Previous pandemic influenza plans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thailand | Upper middle | East Asia | Constitutional monarchy | Mixed | UHC | 80 | 43.7 | Yes |

| Indonesia | Upper middle | East Asia | Presidential republic | Mixed | No UHC | 72 | 38.1 | Yes |

| Bangladesh | Lower middle | South Asia | Parliamentary republic | Mixed | No UHC | 48 | 39.5 | Yes |

| Nepal | Lower middle | South Asia | Parliamentary republic | Mixed | UHC | 62 | 39.5 | Yes |

| Sri Lanka | Lower middle | South Asia | Federal parliamentary republic | Mixed | No UHC | 55 | 51.4 | Yes |

| Bhutan | Lower middle | South Asia | Federal parliamentary republic | Mixed | No UHC | 48 | 37.4 | Yes |

| India | Lower middle | South Asia | Presidential republic | Mixed | No UHC | 66 | 47.9 | Yes |

3.2. Pre-requisites

This domain has four parameters namely political will, availability of resources, (dis) incentives for compliance, and human and financial resources. Political will refers to the degree to which there is evidence in the plans that the government supported the pandemic response. This was determined based on documentation of who commissioned the report and the stakeholders involved in the process. There was evidence of political will in all the reviewed pandemic plans, since the Ministries of health (political office) either led or were key stakeholders in their development. Five country plans (i.e., Thailand, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and India) discussed the important role played by various types of national and subnational institutions in the development of the COVID-19 response plans. For instance, the Nepal plan described the participation of different committees, task teams. The plan also described processes that were developed to support appropriate representation of technical experts (e.g. public health experts, virologist, immunologist, epidemiologist, infectious disease specialist, pulmonologist, emergency medicine specialist, critical care specialist, researchers etc.).

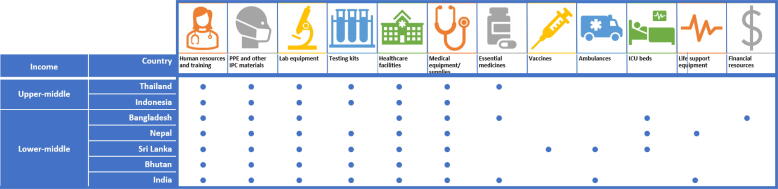

All of the national plans described various resources that were required during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Fig. 2). All plans described the need for key resources: health human resources; their training; Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and other Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) materials; medical equipment and supplies; laboratory equipment; and healthcare facilities. All country plans with the exception of Bangladesh also described the necessity of testing kits. Furthermore, Sri Lanka and India identified the need for ambulances; and, Bangladesh, India and Thailand identified the need for essential medicines. However, only Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka identified the need for ICU beds and explicitly identified the need for financial resources to support the implementation of the pandemic plan and included a budget. Other resources were identified in only one nation plan, for instance, life support equipment (Nepal), vaccines (Sri Lanka), telemedicine infrastructure (Thailand), and hotels for accommodating patients (Nepal).

Fig. 2.

Resource gaps identified.

None of the reviewed plans described any (dis) incentives for compliance.

3.3. The priority setting process

This domain includes nine parameters which we discuss in detail below, namely: planning for continuity of care across the health systems, stakeholder participation, use of clear priority setting process, explicit relevant priority setting criteria, and evidence; reflection of public values, publicity of priorities and criteria, functional mechanisms for appealing the decision; and functional mechanisms for enforcement the decision.

3.4. Stakeholder involvement

Various stakeholders were involved in developing the COVID-19 pandemic plans (Table 3). All the plans were led by Ministries of Health and most explicitly identified additional stakeholders, including representatives from government non– health sectors, international development partners, non– government organizations, community groups and various academics and technical experts in various medical disciplines. While a commitment to participatory processes of plan development was stated in all plans, only India’s plan explicitly provided the names of all stakeholders involved, including representatives of specific Non-Government Organizations(NGO), community groups, and religious leaders.

Table 3.

Stakeholders involved in the COVID-19 pandemic plan.

| Country | Stakeholders involved |

|---|---|

| Thailand | Plan mentions the conformation of a Multi-Sectoral Integrated Response Plan Cabinet lead by the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH), with participation of Public Health Emergency Division and Government Pharmaceutical Organization, besides academics [33] |

| Indonesia | Plan mentions the participation of special staff of the Minister of Health for Governance Sector, Director of Health Promotion and Community Empowerment, Directorate General of Public Health, Head of BTDK Research and Development Center, representatives of Directorate of Primary Health Care, Directorate General of Health Services, and the Health Crisis Center; representatives of several provinces, different hospitals, as well as representatives of the Indonesian Doctors Association (IDI), the Indonesian Lung Doctors Association (PDPI), the Association of Internal Medicine Specialists (PAPDI), the Indonesian Midwives Association (IBI), the Indonesian National Nurses Association (PPNI), the Indonesian Association of Epidemiologists (PAEI), the Association of Indonesian Health Services (ADINKES), and representatives of the Institute for Molecular Biology (Eijkman) [34] |

| Bangladesh | Ministries of health, finance, international affairs, social welfare, and environment, had started their own initiatives and suggested actions to combat the spread of COVID-19 [35] |

| Nepal | The plan stated that different stakeholders participated in giving feedback to the plan; however, the document does not provide a list of people or institutions [36] |

| Sri Lanka | This plan is developed by the Ministry of Health in consultation with the relevant stakeholders. No specification of who the stakeholders are other than to identify the various committee involved in COVID response: Disaster Preparedness and Response Division (DPRD) of the MoH and Presidential Task Force (PTF); The Director General of Health Services has appointed three committees, namely, National committee, Technical committee, and an Action committee |

| Bhutan | The plan is published by the Royal Government of Bhutan's MOH. There is also a statement that the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) for COVID-19, Ministry of Health formed several committees integrated by different stakeholders from different institutions and organizations [37] |

| India | Pandemic plan identified international development partners including the WHO, the World Bank, United Nations, NGOs, community groups and religious leaders [38] |

3.5. Use of evidence

Five country plans (Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Indonesia, and India) had clear indication that their plans were informed by evidence. All five plans explicitly indicated that the WHO guidelines informed their development. These plans also incorporated evidence such as [country-specific] epidemiological data on COVID-19 related mortality, morbidity, and testing. Two plans (Bhutan and Nepal) did not explicitly make reference to any evidence that informed the areas defined in the plans.

3.6. Explicit criteria and equity considerations

This parameter assesses the degree to which explicit priority setting criteria, including equity were included in the pandemic plans. While none of the plans neither explicitly identified any priority setting criteria nor explicitly identified equity as a guiding criterion, several populations were identified as priority populations based on their perceived and experienced vulnerability within the health system. This suggests efforts to integrate the equity criterion. For example, the plans from Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Thailand, and India explicitly prioritized the elderly based on their higher risk for infection and severe disease. In addition to the elderly, the Bangladesh and Nepal plans prioritized people with disabilities while the Bangladesh and India plans prioritized immigrants (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of prioritized population groups within the country plans.

| Population prioritized | Thailand | Indonesia | Bangladesh | Nepal | Sri Lanka | Bhutan | India | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prioritized for continuity of services | Pregnant women | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Young infants | ● | |||||||

| People in need of sexual and reproductive services | ● | |||||||

| People with pre-existing illnesses | ||||||||

| People with HIV | ||||||||

| Prioritized for other activities in the plan |

Immigrants | ● | ● | |||||

| Ethnic groups | ||||||||

| Population in rural areas | ||||||||

| Refugees/ internal displaced | ● | |||||||

| Sexual and gender minorities | ||||||||

| People with disabilities | ● | ● | ||||||

| Homeless population | ||||||||

| Inmates | ||||||||

| Institutionalized | ||||||||

| Mentally ill | ● | |||||||

| Travellers | ● | ● | ||||||

| Healthcare workers | ● | ● | ||||||

| Elderly | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| People immune-compromised | ● | ● | ||||||

| People with comorbidities | ● | ● |

3.7. Publicity

This parameter requires that both priorities and the rationales for priority setting be publicly communicated. Since all the plans were available on the websites of national governments, this parameter was in part, addressed. Furthermore, all the plans included communication strategies which focused on measures for mitigate the pandemic. For example, Indiás plan explicitly mentioned risk communication to mitigate psycho-social issues and stigma, while Thailand’s plan included appropriate communication strategies for disseminating public health and COVID-19 information to different audiences.

While the reviewed plans included several communication strategies targeting different audiences, the content was clearly not about priority setting decisions.

3.8. Appeals and revisions

According to this parameter, there should be explicit mechanisms foe appealing and revising the priorities based on new evidence. Three plans (Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan) identified explicit mechanisms for revising the plans. For example, the Bangladesh plan identified mechanisms for revising and updating the national IPC guidelines and standard operating procedures, when necessary; while the Nepal and Bhutan plans mentioned regular updates based on the evolving scenario. While some plans identified explicit mechanisms for updating and revising the decisions, none articulated any appeals mechanisms.

3.9. Planning for continuity of services

We examined the national pandemic preparedness and response plans to understand whether these included strategies to maintain a continuity of services across the health system in the face of the pandemic. Only India, Nepal and Sri Lanka national plans included such strategies. These explicitly described plans to maintain a continuity of reproductive, maternal, neonatal, child health and immunization programmes, and the management and provision of medicines for different communicable and non-communicable conditions (see Table 4). Notably, only the Nepal plan prioritized the continuity of post-rape management services including access to emergency contraceptive pills and psychosocial support services.

Four parameters within this domain: clear priority setting process/tools, explicit priority setting criteria reflection of public values, and appeals and enforcement mechanisms; were not addressed in any of the reviewed pandemic preparedness and response plans.

3.10. Implementation of priorities and priority setting impact

The implementation domain includes two parameters associated with the allocation of resources according to priorities and if implementation of priorities improved internal accountability. Since the study was based on reviewing the pandemic plans, the assessment of the implementation parameters was limited to identifying whether the plans included an implementation plan and/or a budget. The plans from Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka were the only ones that provided budgets with clear resource allocation process and decisions.

Furthermore, the plans from Bangladesh and Nepal described the establishment of committees and strategies for monitoring and coordinating COVID-19 information and activities- which activities could promote transparency, improve internal accountability and reduce corruption.

The domain priority setting impact includes five parameters, namely: impact on health policy and practice, on population health, and on reducing inequalities; fair financial contribution and increased public confidence in the health sector. These parameters were not discussed explicitly in the reviewed documents given the focus of the study was on the initial plans developed at the outset of the pandemic to guide the response.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the degree to which the parameters of effective priority setting were included in the national COVID-19 pandemic plans from a sample of seven countries from the WHO-SEA region. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically assess the inclusion of priority setting in the pandemic plans in this region.

Our analysis indicates that some of the quality parameters of the Kapiriri & Martińs priority setting framework were adequately addressed in those plans. Particularly parameters related to the degree to which the plans reflected political support, credible decision-making institutions, clear description of resources available or required, and the description of stakeholders participating in the development and implementation of the COVID-19 plans were present in all the reviewed plans.

Although not explicitly articulated, we assumed that there was government support and political will since the government commissioned the response committees and government officers led the development of the plans. This may not be surprising, based on prior studies in the region [3]. The literature notes that South-East Asian countries have faced tremendous challenges during the pandemic since some of the countries in the region have underdeveloped public health infrastructure and insufficient human resources [3], [13], [14]. The stress of the pandemic, the public and global outcry and pandemic panic as well as the global declaration of a pandemic (rather than isolated epidemics as typically experienced in the region) may have galvanized political will and support; and the swift convening of institutions to support pandemic planning within the sampled countries.

All of the country plans reviewed in this study described the resources required during the COVID-19 pandemic, including the necessity of human resources and their training, PPE and other IPC materials, medical equipment and supplies, and laboratory equipment, though a minority of countries pre-specified the financial implications and resource allocation requirements. These findings are corroborated by findings from the other WHO regions such as WHO- AFRO and those from Latin America and the Caribbean islands [15], [16] as well as those by other authors; for example two studies mentioned the inadequate surgical masks supply and insufficient personal protective equipment among Thai workers during the pandemic [14], [21]; and another described the need for healthcare equipment and other essential goods and services in India [3]. In response to the critical need for human resources, a need identified in other contexts [15], the Indonesian government, in addition to mobilizing test kits, budgeted Rp 23.3 trillion for monetary incentives for healthcare workers and the non-health sector to sustain services [14]. This recognition of the need for and mobilization of services in a region whose public healthcare system has been known to be fragmented highlights the additional challenges that a pandemic such as COVID-19 may present to health systems [14].

Strong priority setting institutions are critical to the effectiveness of the prioritization processes [22], [23], [24]. The reviewed plans identified several technical stakeholders such as the health ministry, and other stakeholders with technical knowledge (e.g., medical providers) who were involved in their development. The technical expertise may have contributed to the legitimacy of these stakeholders. However, the legitimacy and quality of the response decisions made by these committees may have further been strengthened by their having involved various actors. Pandemic responses in the region are reported to have comprised public–private and co-governance partnerships between medical service providers, government agencies, private and corporate financiers and civil society organizations [14]. Although critical, it was not possible to assess the capacity of these committees to set priority setting based on the reviewed plans.

Furthermore, since we reviewed only the national level plans, it was impossible to conduct sub-national assessments, which would have provided additional understanding especially for expansive countries such as India, which are also decentralized. It is not clear, based on the reviewed plans, the extent to which countries that are highly centralized, were able to prioritize advice from units that were are already traditionally close to decision-makers, compared to those further away or performing scrutiny functions that could potentially slow down decision making. It is possible that, by way of their independence and mandates, other decentralized entities within these countries continued to make regulatory decisions without necessarily coordinating with the central units of the government [13]. Assessing the legitimacy and capacity of these entities was beyond the scope of this study.

Since priority setting is both a technical and a political process, the literature recommends that priority setting should be guided by an explicit framework, and explicit criteria [23], [25]. However, none of the reviewed plans identified any priority setting framework or criteria. Lack of explicit technical and political process may lead to inconsistences in the decision-making, and, in some cases, introduce other influences and values [26]. A notable exception would be Thailand, which has a rich history of systematic priority setting in their healthcare system and have been pioneers among the middle-income countries in advancing the use of health technology assessment frameworks to guide priority setting in the country as well as the region. Thailand has debated critical health system priority setting challenges such as PS for patients for kidney transplants and developing an explicit health care package [21]. Despite this experience with HTA frameworks more specifically, the plan from Thailand was not explicit in its description of process or criteria used to make decisions for the initial response to the pandemic. The need for a rapid response to the pandemic might have made it impossible for the PS institutions to ensure that the philosophical underpinnings of priority setting were integrated into the response plans. Conversely, it as in several other countries, the traditional PS institution may not have been involved in the pandemic planning. It is also possible that PS was described in another document which we could not access online.

The literature on criteria for priority setting supports its use because criteria help to ensure consistent decision making and to limit the role of self interest and political actors. Fair priority setting requires, in particular, that equity is a central criterion to identify priority populations. For example, the Guidance on priority setting in health care (GPS-Health) proposes that:

“….criteria related to the disease an intervention targets (severity of disease, capacity to benefit, and past health loss); characteristics of social groups an intervention targets (socioeconomic status, area of living, gender; race, ethnicity, religion and sexual orientation); and non-health consequences of an intervention (financial protection, economic productivity, and care for others), are considered.” [27]

The need to consider the equity criterion was highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic which exposed the challenges that vulnerable groups face. Prior to the pandemic, these populations lacked access to health services and were left out of formal policy and social protection measures—these were exacerbated by the pandemic [17], [18], [21], [28], [29], [30]. The United Nations identified vulnerable groups including migrants, refugees, stateless persons and displaced persons, indigenous populations, people living in poverty, those without access to water and sanitation or adequate housing, persons with disabilities, women, older persons, LGBTI people, children, and people in detention or other institutions [12]. Ideally, these should have been prioritised in the national pandemic plans.

While six plans explicitly identified priority populations, the groups identified varied tremendously on which populations and communities to prioritize. For instance, while all countries in WHO-SEARO have refugees and immigrants [31], only the Bangladesh plan explicitly prioritised refugees. Bangladesh hosts more than 800,000 Rohingya refugees [12], so it may be that the concentration of, and the special global attention that has been given to the Rohingya refugees influenced their inclusion. Many illegal immigrants lack health insurance coverage, and most work and live in conditions where they are highly likely to be exposed to COVID-19 infection and transmission [12], [21], [32].

Our study has several limitations. First, since this was part of a global comparative study involving the six WHO regions, for feasibility purposes, we sampled at least 40 % of the countries from each region. This meant that for WHO-SEARO, seven of the eleven countries in this region, hence the findings may not be generalizable to all the countries in the region. Second, we purposively identified COVID-19 preparedness and response plans that were published during the initial stages of the pandemic. It is highly likely that with the progression of the pandemic, countries revised/ amended their plans to reflect the priority setting parameters. Furthermore, we were unable to assess the parameters (e.g. those associated with implementation and impact), since the study was based on a review of the plans. Furthermore, it is not possible to assess if the plans were implemented as stipulated. This would require conducting interviews, which was beyond the scope of the study.

5. Conclusion

Based on the analysis using the parameters for effective priority setting in Kapiriri and Martin’s (2017) framework. Overall, most of the plans included specific committees that were designated to set priorities, the participation of civil society actors. However, none of the plans presented clear priority setting process, or used a formal priority setting framework and several lacked explicit guiding criteria or principles for priority setting.

Systematic priority setting is critical to improving the quality of COVID-19 (and future) pandemic preparedness and response, WHO-SEARO should be supported to integrate evaluation of actual priority setting in order to understand the actual impact of the prioritization process on population health, but more specifically on the most vulnerable populations in this region.

Since systematic priority setting is decisive for strengthening the quality of pandemic preparedness and response, there should be synchronized efforts to integrate evaluation of actual priority setting to understand the concrete impact of the prioritization process on population health, but more specifically on the most vulnerable populations in WHO-SEARO.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Claudia-Marcela Vélez: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Lydia Kapiriri: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Elysee Nouvet: Writing – review & editing. Susan Goold: Writing – review & editing. Bernardo Aguilera: Writing – review & editing. Iestyn Williams: Writing – review & editing. Marion Danis: Writing – review & editing. Beverley M. Essue: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

GP-Set Research Collaborative.

Footnotes

WHO-SEARO countries: Bangladesh, Bhutan, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, India, Indonesia, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Timor-Leste.

South Asia countries: Brunei, Myanmar, Cambodia, Timor-Leste, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). SEAR COVID-19 - Dashboard [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Mar 4]. Available from: https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/56d2642cb379485ebf78371e744b8c6a.

- 2.Gupta I., Guin P. Communicable diseases in the South-East Asia Region of the World Health Organization: Towards a more effective response. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(3):199–205. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.065540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babu G.R., Khetrapal S., John D.A., Deepa R., Narayan K.M.V. Pandemic preparedness and response to COVID-19 in South Asian countries. Int J Infect Dis [Internet] 2021;104 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.048. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO South-East Asia Region. Blood Pressure, Take control. Reg Heal Forum, WHO South-East Asia Reg [Internet]. 2013;17(1):1–83. Available from: WHO_regional-health-Forum_BP.pdf.

- 5.Bezbaruah S., Wallace P., Zakoji M., Padmini Perera W.S., Kato M. Roles of community health workers in advancing health security and resilient health systems: emerging lessons from the COVID-19 response in the South-East Asia Region. WHO South-East Asia J Public Heal. 2021;10(3):41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.GHS Index. GHS Index [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.ghsindex.org/.

- 7.Ahmad R., Atun R.A., Birgand G., Castro-Sánchez E., Charani E., Ferlie E.B., et al. Macro level influences on strategic responses to the COVID-19 pandemic - an international survey and tool for national assessments. J Glob Health. 2021;11:1–11. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.05011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.GHS Index. The U.S. and COVID-19: Leading the World by GHS Index Score, not by Response - GHS Index [Internet]. GHSI Index News. [cited 2022 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.ghsindex.org/news/the-us-and-covid-19-leading-the-world-by-ghs-index-score-not-by-response/.

- 9.Counahan M., Khetrapal S., Parry J., Servais G., Roth S. Investing in Health Security for Sustainable Development in Asia and the Pacific: Managing Health Threats Through Regional and Intersectoral Cooperation. Work Pap. 2018;56 [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for South-East Asia Region. Improving retention of health workers in rural and remote areas: Case studies from WHO South-East Asia Region. India; 2020. 255 p.

- 11.Panthi B., Khanal P., Dahal M., Maharjan S., Nepal S. An urgent call to address the nutritional status of women and children in Nepal during COVID-19 crises. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):4–6. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01210-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UN United Nations. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on South-East Asia. 2021.

- 13.OECD. Regulatory responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Southeast Asia [Internet]. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). 2021. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b9587458-en.

- 14.Djalante R, Nurhidayah L, Van Minh H, Phuong NTN, Mahendradhata Y, Trias A, et al. COVID-19 and ASEAN responses: Comparative policy analysis. Prog Disaster Sci [Internet]. 2020 Dec 1 [cited 2021 Dec 9];8:100129. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7577870/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Kapiriri L, Kiwanuka S, Biemba G, Velez C, Razavi SD, Abelson J, et al. Priority setting and equity in COVID-19 pandemic plans: a comparative analysis of 18 African countries. Health Policy Plan [Internet]. 2021 Oct 7 [cited 2021 Dec 9];00:1–13. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8500007/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Vélez C.-M., Aguilera B., Kapiriri L., Essue B.M., Nouvet E., Sandman L., et al. An analysis of how health systems integrated priority-setting in the pandemic planning in a sample of Latin America and the Caribbean countries. Heal Res Policy Syst [Internet] 2022;20(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12961-022-00861-y. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapiriri L., Martin D.K. Successful priority setting in low and middle income countries: A framework for evaluation. Heal Care Anal. 2010;18(2):129–147. doi: 10.1007/s10728-009-0115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapiriri L. International validation of quality indicators for evaluating priority setting in low income countries: process and key lessons. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2017 Jun 19 [cited 2021 Aug 25];17(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28629347/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Siraj M.S., Dewey R.S., Hassan A.S.M.F.U. The infectious diseases act and resource allocation during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. Asian Bioeth Rev. 2020;12(4):491–502. doi: 10.1007/s41649-020-00149-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prinja S., Pandav C.S. Economics of COVID-19: challenges and the way forward for health policy during and after the pandemic. Indian J Public Health. 2020;64:S231–S233. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_524_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shadmi E., Chen Y., Dourado I., Faran-Perach I., Furler J., Hangoma P., et al. Health equity and COVID-19: global perspectives. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(104):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01218-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitton C., Donaldson C., Dionne F., Peacock S. Addressing prioritization in healthcare amidst a global pandemic. Healthc Manag. Forum. 2021:5–8. doi: 10.1177/08404704211002539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Razavi S.D., Kapiriri L., Wilson M., Abelson J. Applying priority-setting frameworks: a review of public and vulnerable populations’ participation in health-system priority setting. Health Policy (New York) 2020;124(2):133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapiriri L., Abelson J., Wilson M. Barriers to equitable public participation in health-system priority setting within the context of decentralization: the case of vulnerable women in a Ugandan District. Int J Heal Policy Manag. 2020;0(x):1–11 doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terwindt F, Rajan D, Soucat A. Priority-setting for national health policies, strategies and plans. In: Schmets G, Rajan D, Kadandale S, editors. Strategizing national health in the 21st century: a handbook [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. p. 84. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/publications/nhpsp-handbook-ch4/en/.

- 26.Miljeteig I., Forthun I., Hufthammer K.O., Engelund I.E., Schanche E., Schaufel M., et al. Priority-setting dilemmas, moral distress and support experienced by nurses and physicians in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Nurs Ethics. 2021;28(1):66–81. doi: 10.1177/0969733020981748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norheim OF, Baltussen R, Johri M, Chisholm D, Nord E, Brock DW, et al. Guidance on priority setting in health care (GPS-Health): the inclusion of equity criteria not captured by cost-effectiveness analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc [Internet]. 2014 Aug 29 [cited 2022 Jan 28];12(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25246855/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Emanuel E, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, et al. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2020 May 21 [cited 2021 Jul 26];382(21):2049–55. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32202722/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Wasserman D., Persad G., Millum J. Setting priorities fairly in response to Covid-19: Identifying overlapping consensus and reasonable disagreement. J Law Biosci. 2020;7(1):1–12. doi: 10.1093/jlb/lsaa044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosam A., Goldstein S., Erzse A., Tugendhaft A., Hofman K. Building trust during COVID 19: Value-driven and ethical priority-setting. South African Med J. 2020;110(6):443–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.United Nations High Commission for Refugees, UNHCR. Trends at a glance: Global trends forced displacement in 2019. UNHCR [Internet]. 2020;1–84. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/5ee200e37.pdf.

- 32.World Bank. Potential Responses to the COVID-19 Outbreak in Support of Migrant Workers. Vol. 8, Potential Responses to the COVID-19 Outbreak in Support of Migrant Workers. 2020.

- 33.Sirilak S. Thailand́s Experience in the COVID-19 Response. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2020;6(11):951–952. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Republik I.K.K. Pedoman Kesiapsiagaan Menghadapi Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Direkorat Jenderal Pencegahan dan Pengendalian Penyakit. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Government of the People’s Republic of National Bangladesh. National Preparedness and Response Plan for COVID-19, Bangladesh. Mohakhali; 2020.

- 36.Government of Nepal. Health Sector Emergency Response Plan COVID-19 pandemic. Nepal; 2020.

- 37.Bhutan Ministry of Health. National Preparedness and Response Plan for Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) [Internet]. Vol. 4th Editio. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/covid-19-strategy-update-13-april-2020%0Ahttps://www.who.int/publications-detail/strategic-preparedness-and-response-plan-for-the-new-coronavirus.

- 38.Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Preparedness and response to COVID-19 in Urban Settlements-India. India; 2020.