Abstract

The gene (pomA) encoding PomA, an OmpA-like major outer membrane protein of the bovine respiratory pathogen Pasteurella haemolytica, was cloned, and its nucleotide sequence was determined. The deduced amino acid sequence of PomA has significant identity with the sequences of other OmpA family proteins. Absorption of three different bovine immune sera with whole P. haemolytica cells resulted in a reduction of bovine immunoglobulin G reactivity with recombinant PomA in Western immunoblots, suggesting the presence of antibodies against PomA surface domains.

Pasteurella haemolytica serotype 1 (S1) is responsible for an often fatal fibrinous bronchopneumonia in feedlot beef cattle (13). P. haemolytica-induced pneumonia results from physical and immunologic stresses associated with weaning, shipping, and viral infections. The interaction of these predisposing factors and respiratory pathogens is referred to as the bovine respiratory disease complex. Bovine respiratory disease accounts for significant economic losses to the beef cattle industry in North America, estimated to be $600 million to $1 billion annually (15).

Numerous studies with experimental vaccines suggest that antibodies against a secreted cytolytic toxin (leukotoxin, Lkt) (7, 31) and antibodies against P. haemolytica surface antigens contribute to protective immunity in cattle. Purified P. haemolytica outer membranes alone are effective in enhancing protection against P. haemolytica (23). The surface antigens that are likely to be most important in eliciting protective immunity are outer membrane proteins (OMPs) (reviewed in reference 5). Bovine antibody responses against P. haemolytica surface extract proteins correlate with resistance to pneumonia (6, 33). We and others have measured bovine antibodies, present in immune sera, against several individual P. haemolytica OMPs, including the heat-modifiable OmpA-like protein, PomA, that migrates at 30 and 38 kDa on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gels (21), a 38-kDa surface-exposed lipoprotein (Lpp38) (29), a 45-kDa surface-exposed lipoprotein (PlpE) (28), a 94-kDa OMP (27), and several 28- to 30-kDa membrane lipoproteins (9).

Bovine antibodies that are directed against surface-exposed epitopes of P. haemolytica OMPs likely play a significant role in host defense mechanisms like complement-mediated killing (20) and Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis by neutrophils and macrophages (3, 8). Therefore, our work has focused on identifying and characterizing P. haemolytica OMPs with surface domains that are targets of antibodies present in sera from immune cattle (30). We found that the 45-kDa lipoprotein (PlpE) elicits bovine antibodies that effect complement-mediated killing of P. haemolytica (28). Our previous studies with PomA revealed that it is recognized by antibodies from cattle immune to P. haemolytica challenge and that it possesses surface-exposed regions (21). However, it is not known if those antibodies are directed against surface regions of PomA. Here, as part of our continuing studies on the role of anti-PomA antibodies in protective immunity against P. haemolytica, we have cloned and sequenced the complete pomA gene and expressed and purified recombinant PomA (rPomA). We used purified rPomA to determine if anti-PomA antibodies, present in bovine immune sera, are directed against surface-exposed regions of the protein.

Bacteria and culture conditions.

P. haemolytica (89010807N) S1 was grown in brain heart infusion broth or on brain heart infusion agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) as previously described (26). Escherichia coli DH5α (16) and JM109 (38) were used as host strains for gene cloning and protein expression.

Cloning and characterization of P. haemolytica pomA.

For cloning pomA, we synthesized two degenerate oligonucleotides, 503 (5′-CCRCAAGCNAATACNTTTTA-3′) and 504 (5′-GGYGCNAAAGCNGGYTGGGC-3′), based on the sequence of the 16 N-terminal residues (APQANTFYAGAKAGWA) of PomA (21). We used radiolabeled oligonucleotides 503 and 504 to probe Southern blots of restriction enzyme-digested chromosomal DNA from P. haemolytica and to construct a map of the chromosomal region harboring pomA. The results indicated that pomA is present in a single copy on the P. haemolytica genome (data not shown). We were unable to clone a chromosomal DNA fragment containing the complete pomA locus. Therefore, the gene was cloned as two separate fragments, using the vector pGEM-3Z (Promega, Madison, Wis.). A 1.5-kbp EcoRV/BamHI fragment, containing 5′ flanking DNA and the first 156 nucleotides (nt) of pomA, was amplified by PCR with a high-fidelity enzyme, Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and cloned. Next, a 2.5-kbp BamHI/EcoRI fragment, containing the remainder of pomA and 3′ flanking DNA, was cloned from genomic DNA. Both DNA strands spanning pomA and flanking regions were sequenced at the Oklahoma State University Recombinant DNA/Protein Resource Facility, on an Applied Biosystems 373A automated DNA sequencer (Foster City, Calif.).

Expression and purification of rPomA.

The complete pomA gene was assembled in a low-copy-number vector (pWKS30) (35) and transformed into E. coli DH 5α, and rPomA was expressed. rPomA was also expressed with the pRSET Express Protein Purification System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). The region of pomA encoding the mature form of the protein was amplified by PCR and cloned into the vector pRSETB (Invitrogen), downstream of and in-frame with sequences encoding an N-terminal fusion peptide with a metal binding domain. DNA sequencing of fusion protein coding regions was performed to verify that no errors occurred during amplification. rPomA was purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen).

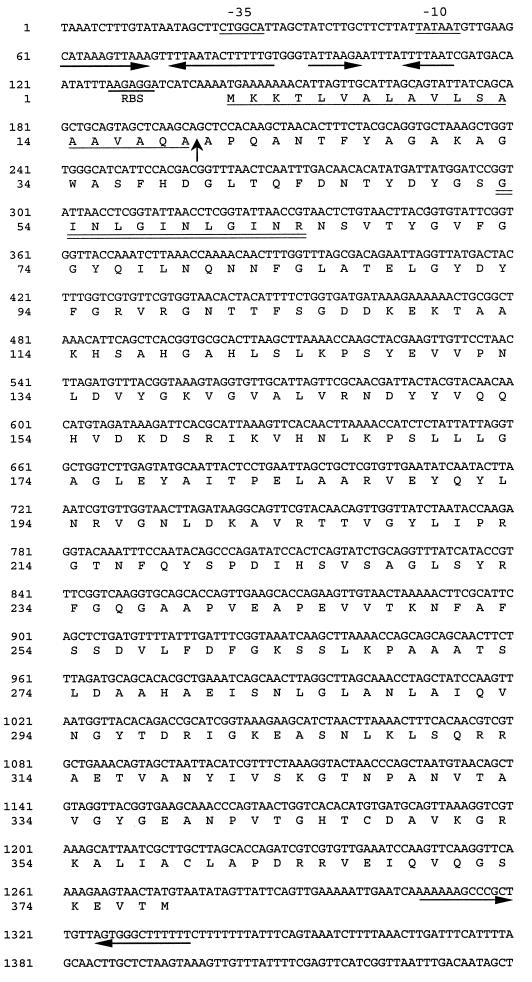

Analyses of the pomA nucleotide sequence revealed the presence of a long open reading frame with two potential ATG start codons (nt 115 to 117 and 142 to 144) (Fig. 1). The codon at nt 142 is preceded by a consensus ribosome binding site (RBS) (AAGAGG), whereas the codon at nt 115 is not. Hydrophilicity plots for the peptides encoded by the regions spanning nt 115 to 198 and 142 to 198 suggest that the peptide encoded by the latter region more closely matches a consensus signal peptide (data not shown). The first four residues, MKKT, are conserved in the deduced amino acid sequences of E. coli OmpA (2) and the OmpA-like proteins (P5 and fimbrin) from Haemophilus influenzae type b (24, 32) and Haemophilus ducreyi (MOMP and OmpA2) (18). These data suggest that the ATG codon at nt 142 of pomA likely functions as the start codon. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that translation may also initiate at nt 115.

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence of P. haemolytica pomA and the deduced amino acid sequence of PomA. Putative −35 and −10 regions and a potential RBS are underlined. Two inverted repeat sequences are present 5′ of the RBS and are indicated by the arrows. Another inverted repeat with characteristics of a rho-independent transcription terminator is indicated by arrows in the region 3′ of pomA. The putative signal peptide sequence is underlined, and the cleavage site is indicated with an arrow. The 20 amino acid residues to the right of that arrow are identical to those previously determined by N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis of purified PomA (21). The tetrapeptide repeats (GINLGINLGINR) are indicated with a double underline.

The DNA sequence 5′ of pomA includes a potential −35/−10 promoter region and two inverted repeats that may form stem-loop structures (Fig. 1). In E. coli, ompA mRNA contains two similar but longer inverted repeats, followed by a single-stranded segment containing an RBS (4). Those structures are found in the 130 bp immediately preceding the ompA start codon and are part of the untranslated portion of ompA mRNA. Formation of a stem-loop structure by the more 5′ of the two inverted repeats is responsible for increased half-life of the ompA message (12). Here at the pomA locus, the two inverted repeats more closely resemble those observed 5′ of the H. ducreyi momp gene (18). A role, if there is one, for the inverted repeats in regulation of pomA or momp has not been determined.

PomA analysis and immunologic detection of rPomA.

The deduced amino acid sequence of PomA, starting with the methionine encoded at nt 142 to 144, is a protein with a predicted molecular mass of 40.5 kDa. The sequence beginning with the alanine encoded at nt 198 to 200 matches exactly the N-terminal amino acid sequence previously determined for mature PomA (21). The putative mature form of PomA, starting from this alanine, has a predicted molecular mass of 38.6 kDa.

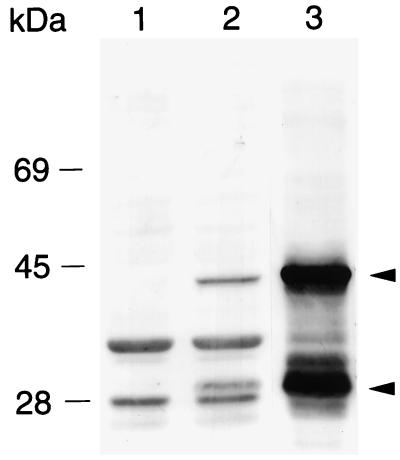

On SDS-polyacrylamide gels, protein bands migrating at 30 and 38 kDa and present in whole-cell lysates from P. haemolytica and from E. coli expressing PomA are recognized by mouse polyclonal antibodies raised against gel-purified PomA (Fig. 2). The murine anti-PomA antibodies also recognize bands in lysates from E. coli that likely correspond to the heat-modifiable forms of OmpA (Fig. 2). In a previous study (21), anti-OmpA murine polyclonal antiserum was used to detect protease-susceptible PomA bands (30 and 38 kDa) in P. haemolytica whole-cell lysates. Heat modifiability is a characteristic of OmpA family proteins and is believed to result from a conformational change in the protein. Upon solubilization for SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), incompletely denatured OmpA family proteins have significant β-structure (14, 17). Generally, when OmpA family proteins are solubilized at lower temperatures (37°C) for SDS-PAGE, the partially folded form of the protein migrates at the lower relative molecular mass (Mr) and the unfolded form migrates at the higher Mr. Extended heating at 95°C before SDS-PAGE may convert all of the protein so that only the higher-Mr form is seen. We have observed that complete denaturation of PomA to the higher-Mr form is dependent on the amount of protein in the sample, the time of heating at 95°C, and the composition of the SDS-PAGE solubilization buffer (25).

FIG. 2.

Western immunoblot demonstrating expression of rPomA by E. coli from a complete pomA gene cloned into the low-copy-number vector pWKS30 (35) and by P. haemolytica. Lanes contain whole-cell lysates of E. coli DH5α (lane 1), E. coli DH5α (pWKS30pomA+) (lane 2), and P. haemolytica (lane 3). Blots were probed as previously described (29) with murine polyclonal antibodies raised against PomA that had been eluted from preparative SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The arrowheads indicate the heat-modifiable forms of PomA that migrate at 30 and 38 kDa.

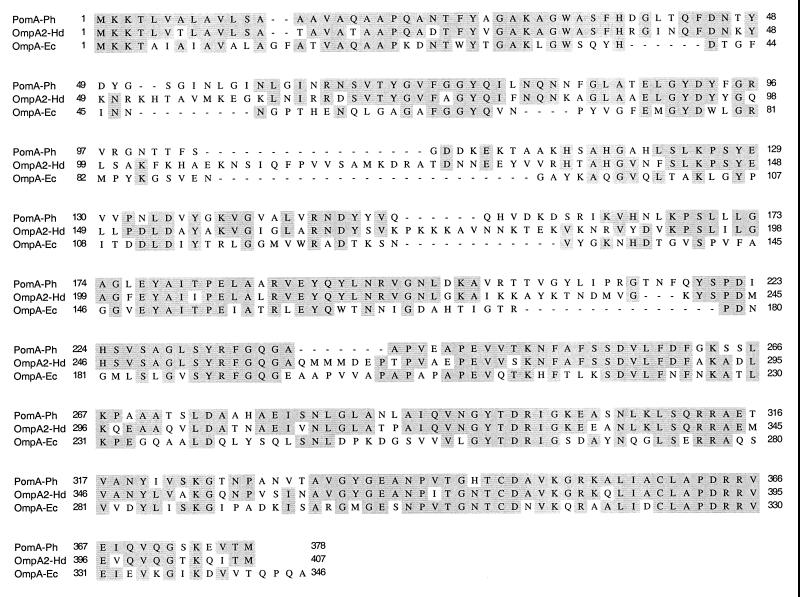

Comparison and alignment of the deduced PomA sequence with sequences of other OmpA family proteins revealed that PomA is most similar to the H. ducreyi proteins OmpA2 (66.7% amino acid identity) and MOMP (64.8% identity) (18). PomA also exhibits 59.5% identity with Omp34 of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (36), 57.8% identity with P5 of H. influenzae (24), and 43.4% identity with E. coli OmpA (2).

An amino acid sequence alignment of PomA with OmpA2 and OmpA reveals that several regions that differ among these proteins correspond to four predicted extracellular loops in OmpA (22). The predicted extracellular domains of OmpA span amino acids (aa) 41 to 55, 81 to 96, 124 to 137, and 166 to 180 (Fig. 3). The corresponding regions in PomA and OmpA2 differ in both amino acid sequence and number of residues. A short repeated tetrapeptide (aa 53 to 64) is present in the first predicted loop region of PomA (Fig. 3). The C-terminal regions of all three proteins contain a peptide motif (NX2LSX2RAX2VX3I/L) that is highly conserved among OmpA family proteins and likely interacts with peptidoglycan (Fig. 3) (11, 19).

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of P. haemolytica PomA (PomA-Ph), H. ducreyi OmpA2 (OmpA2-Hd) (18) (GenBank accession no. U60646), and E. coli OmpA (OmpA-Ec) (2) (GenBank accession no. J01654). Amino acids that are identical in all these proteins are shaded. Hyphens have been inserted to allow for optimal alignment. The putative peptidoglycan interaction domain (NX2LSX2RAX2VX3I/L) that is conserved among OmpA family proteins spans aa 306 to 321 of PomA.

Antibodies against PomA surface domains in bovine immune sera.

A previous study demonstrated that PomA was recognized by antibodies from immune cattle that had been vaccinated with live or killed P. haemolytica cells (21). However, it is unknown if those antibodies are directed against surface-exposed domains of PomA. In addition, we were interested in determining if PomA elicits antibodies against its surface domains following natural exposure of cattle to P. haemolytica. Antibodies against PomA surface epitopes could contribute to bovine defense mechanisms such as complement-mediated killing (20) or antibody-dependent phagocytosis and killing by neutrophils and macrophages (3, 8).

Therefore, we examined three immune sera from cattle for the presence of antibodies against surface domains of PomA. The sera were from cattle that were resistant to experimental P. haemolytica challenge after natural exposure to the bacterium or after vaccination with live P. haemolytica or with P. haemolytica OMPs (30). Sera were absorbed with intact P. haemolytica cells as previously described (28). Absorbed and unabsorbed sera, diluted 1:100 in Tris-saline-nonfat dry milk (TSM) (10mM Tris [pH 7.4], 0.9% [wt/vol] NaCl, 1% nonfat dry milk), were used to probe Western immunoblots of purified rPomA and P. haemolytica whole-cell lysates (Fig. 4). Bovine immunoglobulin (IgG) antibody reactivities of the sera with rPomA were compared by densitometry, using the Multi-Analyst image analysis system and a model GS-700 Imaging Densitometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). For densitometry, an equal volume of each band was measured and expressed as band area multiplied by optical density. For each band, we subtracted the volume of an equal area of background from a region, on the same blot, that had no bands. To account for any differences that may have occurred in serum dilutions and to rule out nonspecific absorption, we also measured antibody reactivities of absorbed and unabsorbed sera with a 55-kDa non-surface-exposed antigen.

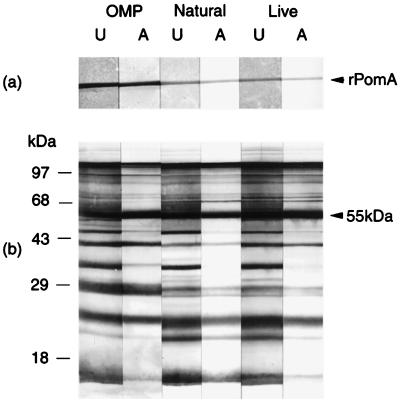

FIG. 4.

Western immunoblot analysis of rPomA (a) and P. haemolytica whole-cell lysates (b) with absorbed and unabsorbed bovine immune sera. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose as described previously (9, 29). Blots were probed with unabsorbed (U) or absorbed (A) bovine immune sera from a calf vaccinated with P. haemolytica OMPs (OMP), a calf naturally exposed to P. haemolytica (Natural), and a calf vaccinated with live P. haemolytica (Live). Immunoblot analysis and bovine IgG detection were performed as previously described (29). The arrowhead in panel b indicates the 55-kDa antigen that served as a control non-surface-exposed antigen for densitometry.

The IgG antibody reactivities of all three immune sera with rPomA were reduced after absorption of sera with whole P. haemolytica cells. Reactivities were reduced by ∼34% after absorption of serum from the naturally exposed calf, by ∼37% after absorption of serum from the calf vaccinated with live bacteria, and by ∼21% after absorption of serum from the calf vaccinated with OMPs (Fig. 4a). In contrast, antibody reactivities with the control 55-kDa protein were not reduced by whole-cell absorption (Fig. 4b). These data suggest that antibodies against surface-exposed domains of PomA may be elicited by natural exposure to P. haemolytica and by vaccination and that antibodies against non-surface-exposed regions of the protein are elicited as well.

OmpA family proteins from several pathogens elicit host antibodies following natural or experimental infections in their typical hosts. Omp34, the OmpA-like protein of the human periodontal pathogen A. actinomycetemcomitans, was shown to be a target for IgG antibodies in sera from patients with periodontitis (37). A 37-kDa OMP that is produced by the bovine respiratory pathogen Haemophilus somnus and has N-terminal amino acid sequence similarity with OmpA may also be a target for bovine antibodies in response to an experimental challenge (34). The nontypeable H. influenzae fimbrin protein, which is very similar to H. influenzae P5, is the target of antibodies in sera from children with chronic otitis media (1, 10). To our knowledge, the occurrence of antibodies against surface domains of an OmpA family protein following infection of a natural host has not been reported.

Our study suggests that further evaluation of the antibody response to P. haemolytica PomA is warranted. As mentioned earlier, complement-mediated killing is believed to play a major role in controlling P. haemolytica pneumonia and occurs primarily by the classical pathway, requiring presensitization of cells with antibody (20). Antibodies directed against epitopes exposed on the bacterial cell surface are necessary for killing by this mechanism. Our future work is designed to evaluate the role of antibodies against surface regions of PomA in complement-mediated killing of P. haemolytica.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of pomA has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF133259.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grant 95-37204-1999 from the National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program of the USDA, the Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station (project OKL02179), and the Oklahoma State University College of Veterinary Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bakaletz L O, Hoepf T, Hoskins T F, DeMaria T F, Lim D J. Abstracts of the Fifth International Symposium on Recent Advances in Otitis Media. 1991. Serological relatedness of fimbriae expressed by NTHi isolates recovered from children with chronic otitis media, abstr. 77; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck E, Bremer E. Nucleotide sequence of the gene ompA coding the outer membrane protein II of Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:3011–3027. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.13.3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chae C H, Gentry M J, Confer A W, Anderson G A. Resistance to host immune defense mechanisms afforded by capsular material of Pasteurella haemolytica, serotype 1. Vet Microbiol. 1990;25:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(90)90081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L H, Emory S A, Bricker A L, Bouvet P, Belasco J G. Structure and function of a bacterial mRNA stabilizer: analysis of the 5′ untranslated region of ompA mRNA. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4578–4586. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4578-4586.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Confer A W. Immunogens of Pasteurella. Vet Microbiol. 1993;37:353–368. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Confer A W, Simons K R, Panciera R J, Mort A J, Mosier D A. Serum antibody response to carbohydrate antigens of Pasteurella haemolytica serotype 1: relation to experimentally induced bovine pneumonic pasteurellosis. Am J Vet Res. 1989;50:98–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conlon J A, Shewen P E, Lo R Y. Efficacy of recombinant leukotoxin in protection against pneumonic challenge with live Pasteurella haemolytica A1. Infect Immun. 1991;59:587–591. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.2.587-591.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czuprynski C J, Hamilton H L, Noel E J. Ingestion and killing of Pasteurella haemolytica A1 by bovine neutrophils in vitro. Vet Microbiol. 1987;14:61–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(87)90053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dabo S M, Styre D, Confer A W, Murphy G L. Expression, purification, and immunologic analysis of Pasteurella haemolytica A1 28-30 kDa lipoproteins. Microb Pathog. 1994;17:149–158. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeMaria T E, McPherson C, Bakaletz L O, Holmes K A. Abstracts of the Fifth International Symposium on Recent Advances in Otitis Media. 1991. Isotype specific antibody response against OMPs and fimbriae of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae isolated from patients with chronic otitis media, abstr. 134; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Mot R, Vanderleyden J. The C-terminal sequence conservation between OmpA-related outer membrane proteins and MotB suggests a common function in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, possibly in the interaction of these domains with peptidoglycan. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:333–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emory S A, Bouvet P, Belasco J G. A 5′-terminal stem-loop structure can stabilize mRNA in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1992;6:135–148. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank G H. Pasteurellosis of Cattle. In: Adlam C, Rutter J M, editors. Pasteurella and pasteurellosis. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press Limited; 1989. pp. 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freudl R, Schwarz H, Stierhof Y D, Gamon K, Hindennach I, Henning U. An outer membrane protein (OmpA) of Escherichia coli K-12 undergoes a conformational change during export. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:11355–11361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffin D. Economic impact associated with respiratory disease in beef cattle. In: Vestweber J, St. Jean G, editors. Veterinary clinics of North America: food animal practice. Vol. 13. Philadelphia, Pa: W. B. Saunders Co.; 1997. pp. 367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heller K B. Apparent molecular weights of a heat-modifiable protein from the outer membrane of Escherichia coli in gels with different acrylamide concentrations. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1181–1183. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1181-1183.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klesney-Tait J, Hiltke T J, Maciver I, Spinola S M, Radolf J D, Hansen E J. The major outer membrane protein of Haemophilus ducreyi consists of two OmpA homologs. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1764–1773. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1764-1773.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koebnik R. Proposal for a peptidoglycan-associating alpha-helical motif in the C-terminal regions of some bacterial cell-surface proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:1269–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDonald J T, Maheswaran S K, Opuda-Asibo J, Townsend E L, Thies E S. Susceptibility of Pasteurella haemolytica to the bactericidal effects of serum, nasal secretions, and bronchoalveolar washings from cattle. Vet Microbiol. 1983;8:585–599. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(83)90007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahasreshti P J, Murphy G L, Wyckoff J H, Confer A W. Purification and partial characterization of the OmpA family of proteins of Pasteurella haemolytica. Infect Immun. 1996;65:211–218. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.211-218.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morona R, Klose M, Henning U. Escherichia coli K-12 outer membrane protein (OmpA) as a bacteriophage receptor: analysis of mutant genes expressing altered proteins. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:570–578. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.2.570-578.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morton R J, Panciera R J, Fulton R W, Ewing G H, Homer J T, Confer A W. Vaccination of cattle with OMP-enriched fractions of Pasteurella haemolytica and resistance against experimental challenge exposure. Am J Vet Res. 1995;56:875–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munson R S, Jr, Grass S, West R. Molecular cloning and sequence of the gene for outer membrane protein P5 of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4017–4020. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.4017-4020.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy, G. L. 1999. Unpublished observations.

- 26.Murphy G L, Whitworth L C. Construction of isogenic mutants of Pasteurella haemolytica by allelic replacement. Gene. 1994;148:101–105. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson S L, Frank G H. Purification and characterization of a 94-kDa Pasteurella haemolytica antigen. Vet Microbiol. 1989;21:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(89)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pandher K, Confer A W, Murphy G L. Genetic and immunologic analyses of PlpE, a lipoprotein important in complement-mediated killing of Pasteurella haemolytica serotype 1. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5613–5619. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5613-5619.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pandher K, Murphy G L. Genetic and immunologic analyses of a 38 kDa surface-exposed lipoprotein of Pasteurella haemolytica A1. Vet Microbiol. 1996;51:331–341. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(96)00029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandher K, Murphy G L, Confer A W. Identification of immunogenic, surface-exposed outer membrane proteins of Pasteurella haemolytica serotype 1. Vet Microbiol. 1999;65:215–226. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(98)00293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shewen P E, Wilkie B N. Vaccination of calves with leukotoxic culture supernatant from Pasteurella haemolytica. Can J Vet Res. 1988;52:30–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sirakova T, Kolattukudy P E, Murwin D, Billy J, Leake E, Lim D, DeMaria T, Bakaletz L. Role of fimbriae expressed by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in pathogenesis of and protection against otitis media and relatedness of the fimbrin subunit to outer membrane protein A. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2002–2020. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.2002-2020.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sreevatsan S, Ames T R, Werdin R E, Yoo H S, Maheswaran S K. Evaluation of three experimental subunit vaccines against pneumonic pasteurellosis in cattle. Vaccine. 1996;14:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00138-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tagawa Y, Haritani M, Ishikawa H, Yuasa N. Characterization of a heat-modifiable outer membrane protein of Haemophilus somnus. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1750–1755. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1750-1755.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang R F, Kushner S R. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing, and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White P A, Nair S P, Kim M J, Wilson M, Henderson B. Molecular characterization of an outer membrane protein of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans belonging to the OmpA family. Infect Immun. 1998;66:369–372. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.369-372.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson M E. IgG antibody response of localized juvenile periodontitis patients to the 29 kilodalton outer membrane protein of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Periodontol. 1991;62:211–218. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]