SUMMARY

OBJECTIVE:

The objective of this systematic review with meta-analysis was to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and short- and long-term tolerability of cannabidiol (CBD), as an adjunct treatment, in children and adults with Dravet syndrome (SD), Lennox-Gataut syndrome (LGS), or tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), with inadequate control of seizures.

METHODS:

This systematic review was conducted through a search for scientific evidence in the Mediline/PubMed, Central Cochrane, and ClinicalTrials.gov databases until April 2022. Selected randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that presented the outcomes: reduction in the frequency of seizures and total seizures (all types), number of patients with a response greater than or equal to 50%, change in caregiver global impression of change (CGIC) (improvement ≥1 category on the initial scale), adverse events (AEs), and tolerability to treatment. This review followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses.

RESULTS:

Notably, six RCTs were included, with a total of 1,034 patients with SD, LGS, and TSC, of which 3 were open-label extension RCTs. The meta-analysis of the studies showed that the use of CBD as compared with placebo, in patients with convulsive seizures refractory to the use of medications, reduces the frequency of seizures by 33%; increases the number of patients with a reduction ≥50% in the frequency of seizures by 20%; increases the number of patients with absence of seizures by 3%; improves the clinical impression evaluated by the caregiver or patient (S/CGIC) in 21%; increases total AEs by 12%; increases serious AE by 16%; increases the risk of treatment abandonment by 12%; and increases the number of patients with transaminase elevation (≥3 times the referral) by 15%.

CONCLUSIONS:

This systematic review, with meta-analysis, supports the use of CBD in the treatment of patients with seizures, originated in DS, LGS, and TSC, who are resistant to the common medications, presenting satisfactory benefits in reducing seizures and tolerable toxicity.

KEYWORDS: Dravet syndrome, Lennox Gastaut syndrome, Tuberous sclerosis complex, Cannabidiol, Seizures, Seizures refractory

INTRODUCTION

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders 1 . About one-third of all patients with epilepsy have drug-resistant seizures. The International League Against Epilepsy defines drug-resistant epilepsy as the “failure of ≥2 appropriate and tolerated antiepileptic drugs (either as monotherapy or in combination) to achieve the sustained freedom of seizures” 2 . Inadequate seizure control significantly affects the quality of life and cognitive function of these patients. Drug-resistant epileptic syndromes are associated with significant comorbidity and high rates of cognitive impairment, as well as psychiatric and physical disability. Currently, cannabidiol (CBD) is being used for three epileptic syndromes: Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS), Dravet syndrome (DS), and tuberous sclerosis complex (CST). Both LGS and DS are early-onset encephalopathic epileptics with poor prognosis and associated with comorbidities.

LGS is a severe epileptic encephalopathy of varying presentation and is associated with high rates of seizure-related injury and cognitive impairment 3–5 . LGS has an incidence of approximately 1:4,000 births; estimates of uncertain prevalence, possibly around 15/100,000. LGS is believed to account for 1–4% of all infant epileptics 3–5 .

DS is rare, intractable, occurs in early childhood and is characterized by prolonged and recurrent partial crises at onset, with progression to generalized polymorphic seizures resulting in developmental delay, cognitive impairment, and increased mortality. SD has an incidence of approximately 1:20,000 births; estimates of uncertain prevalence, possibly around 3/100,000. SD is believed to account for approximately 7% of all severe epileptics initiated before 3 years of age 6–8 .

CBD was also evaluated under conditions with mainly focal seizures, such as TSC. TSC is a genetic disease that can present in any part of the body. The most common manifestations include benign tumors in the skin, brain, kidneys, lung, and heart that cause organic dysfunction 9 . The reported incidence ranges from 1 per 5,800 to 10,000 live births 9 and the prevalence of 1/20,000 people in the UK 9 .

Cannabis has been used to treat epilepsy since antiquity, and interest in cannabis-based therapies has increased in the past decade. CBD, which is one of the main constituents of the Cannabis sativa plant, has anticonvulsant properties and does not produce euphoric or intrusive side effects 10 . The lack of regulation and standardization in the medicinal cannabis industry, however, raises concerns about the composition and consistency of the products that are dispensed 11 . Pharmaceutical grade oral CBD solution is the first product made directly from the cannabis plant, rather than created synthetically, to be authorized by regulatory agencies and the first of a new class of anticonvulsant drugs.

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy, safety, and short- and long-term tolerability of CBD, as an adjuvant treatment in children and adults with inadequately controlled DS, LGS, or TSC.

METHODS

This systematic review will be carried out in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 12 .

A clinical doubt arises: what is the impact of CBD use on outcomes reducing the frequency of seizures and total seizures (all types), number of patients with a response equal to or greater than 50%, impression of clinical improvement by the patient or caregiver, adverse events (AEs), and tolerability to treatment?

The eligibility criteria of the studies are as follows:

Patients with DS, LGS, and TSC;

Treatment with CBD plus usual therapy compared to placebo plus usual therapy;

Outcomes – reduction in the frequency of seizures and total seizures (all types), number of patients with a response greater than or equal to 50%, change in caregiver global impression of change (CGIC) (improvement of ≥1 category in the initial scale), AEs, and tolerability to treat;

Excluding outcomes − intermediaries;

Phase III RCT or observational cohort studies;

No period or language limit;

Text complete available for access; and

Follow-up: minimum of 16 weeks.

The search for evidence will be carried out in the Virtual Scientific Information Base Medline using the search strategy — (Cannabis OR Tetrahydrocannabinol OR Cannabinoids OR Cannabinol OR Cannabidiol) AND (Epilepsy OR infantile spasms OR Epilepsies, Myoclonic OR Tuberous Sclerosis OR Lennox Gastaut Syndrome OR Dravet Syndrome OR Sturge-Weber Syndrome OR Drug Resistant Epilepsy) AND Random*; CENTRAL/Cochrane with the search strategy — (Cannabis OR Tetrahydrocannabinol OR Cannabinoids OR Cannabinol OR Cannabidiol) AND (Epilepsy OR infantile spasms OR Epilepsies, Myoclonic OR Tuberous Sclerosis OR Lennox Gastaut Syndrome OR Dravet Syndrome OR Sturge-Weber Syndrome OR Drug Resistant Epilepsy) and ClinicalTrials.gov with the search — (Cannabinol OR Cannabidiol) AND (Tuberous Sclerosis OR Lennox Gastaut Syndrome OR Dravet Syndrome OR Sturge-Weber Syndrome). The search in these databases will be carried out until April 2022.

The following data were extracted from the studies: author name and year of publication, population studied, methods of intervention and comparison, absolute number of events reductions in the frequency of seizures and total seizures (all types), number of patients with response equal to or greater than 50%, impression of clinical improvement by the patient or caregiver (CGIC), AEs, in addition to follow-up time. The results of the median percentage change (minimum – maximum) in relation to baseline in the monthly frequency of seizures were also extracted.

The risk of bias scans for RCTs will be assessed using the rob 2 tool items 13 , plus other key elements, and expressed as low, moderate, serious or critical risk of bias, and no information. For cohort studies, the tool currently recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration will be used to assess the risk of bias in estimates of effectiveness and safety in nonrandomized Risk of Bias In Non-Randomized Studies — of Interventions (ROBINS-I) intervention studies 13 . ROBINS-I evaluates seven domains of bias, classified by moment of occurrence. The bias risk assessment will be conducted by two independent reviewers (AS and IF), and in case of disagreements, a third reviewer (WB) can deliberate on the evaluation. The quality of evidence will be extrapolated from the risk of bias obtained from the study(s) (if there is no meta-analysis) using the TERMINOLOGY GRADE 14 in very low, low, and high, and through the software GRADE pro 15 (if there is meta-analysis) in very low, low, moderate, and high.

The results for categorical outcomes will be expressed by the difference in risk (DR) between CBD therapy and placebo treatment. If the DR between groups is significant (95% confidence), this will be expressed with the 95% confidence interval (95%CI) and a number needed to treat (NNT) or to produce a Harm (NNH). In continuous measures, the results are expressed as mean difference or median difference with 95%CIs. Data from observational studies are reported as the percentage of participants who experienced a result.

If there is more than one study included with common outcomes, this will be aggregated through meta-analysis, using the RevMan 5.4 software 16 , with the overall risk difference with 95%CIs being the final measure used to support the synthesis of evidence, which will answer the clinical doubt of this assessment. The estimated size of the combined effects was performed by a fixed or random effect model after the evaluation of heterogeneity results. Heterogeneity was also calculated using the value I 2 . The results will be evaluated by study design (RCTs and observational cohorts) and presented individually.

Included studies

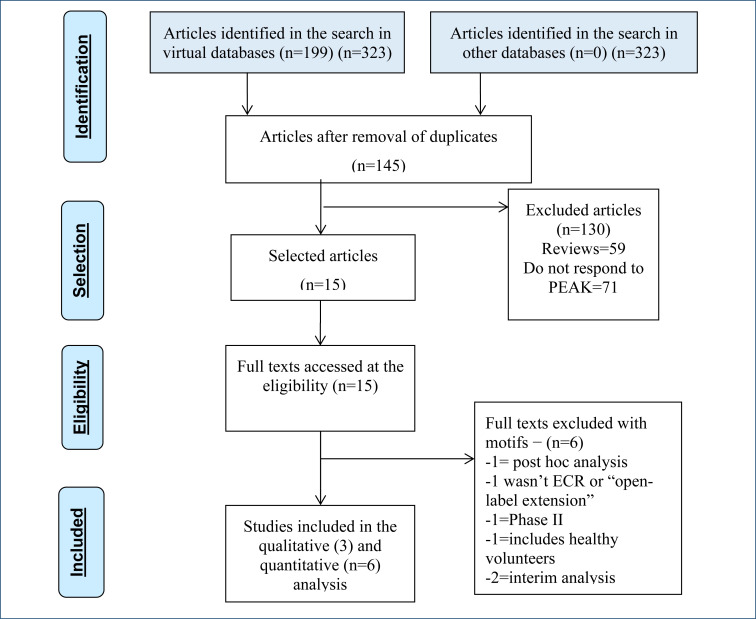

In the search for evidence, 145 articles were retrieved, and 15 studies evaluated the use of CBD plus usual therapy as compared with placebo in the treatment of patients with DS, LGS, and TCS or were observational cohort studies “open-label extension” (OLE). The 15 studies were assessed because they met the eligibility criteria for analysis of the full text. Of these 15 studies, 6 17–22 ECRs and 3 23–25 OLE studies were included to support this evaluation, whose characteristics are described in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The excluded list and the reasons are available in the references and are shown in Figure 1 26 .

Table 1. Characteristics of clinical studies evaluating the use of cannabidiol in patients with Dravet syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis complex.

| Study | Drawing | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Denouement | Follow-up time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devinsky et al. 17 | RCT | Pivotal phase 3 study; patients (n=120) diagnosed with Dravet syndrome; 2–18 years; with uncontrolled epileptic seizures, using more than one anticonvulsant drug, for more than 4 weeks. Multicenter (USA, UK, and Poland) | Staggered dose 5.10–20 mg/kg/day divided into two times a day. Maintenance doses for 12 weeks: 20 mg/kg/day | Placebo | Primary: reduction in the median monthly frequency of convulsions. Secondary: change in the overall impression of caregivers and patients (S/CGIC); reduction in percentage of the number of seizures (25, 50, 75, and 100%); adverse events (number, type and severity) | 14 weeks |

| Miller et al. 19 | RCT | Pivotal phase 3 study; patients (n=199) diagnosed with Dravet Syndrome; 2–18 years; more than one anticonvulsant drug for more than 4 weeks. Multicenter (USA, Spain, Poland, the Netherlands, Australia, and Israel) | Staggered dose 5.10–20 mg/kg/day, divided into two times a day. Maintenance doses for 12 weeks: 10 or 20 mg/kg/day | Placebo | Primary: reduction in the frequency of the number of convulsions. Secondary: change in the overall impression of caregivers and patients (S/CGIC); reduction in percentage of the number of seizures (25, 50, 75, and 100%); adverse events (number, type, and severity) | 14 weeks |

| Devinsky et al. 18 | RCT | Patients (n=34); age between 4 and 10 years; with DS. Evaluation of pharmacokinetics and safety of cannabidiol | Staggered dose 5.10 or 20 mg/kg/day divided into two times a day; treatment maintained for 3 weeks | Placebo | Dose titration and adverse events | 4 weeks |

| Devinsky et al. 20 | RCT | Pivotal phase 3 study; patients (n=225) with LGS; age 2–55 years; diagnosed by electroencephalographic alterations; anticonvulsants drugs for more than 4 weeks, without seizure control | Staggered dose 5.10–20 mg/kg/day divided into two times a day. Maintenance doses for 12 weeks: 10 or 20 mg/kg/day | Placebo | Primary: median reduction in the number of drop seizures and total monthly seizures. Secondary: change in overall impression by caregivers and patients (S/CGIC); reduction in percentage of the number of seizures (25, 50, 75, and 100%); adverse events (number, type, and severity) | 14 weeks |

| Thiele et al. 21 | RCT | Pivotal phase 3 study; patients (n=171) with LGS; age 2–55 years; clinically diagnosed by electroencephalogram (including documented history of slow electroencephalograms [<3.0 Hz]), associated with more than one type of generalized seizure, including falls, for at least 6 previous months; on use of anticonvulsant drugs for more than 4 weeks | Staggered dose 5.10–20 mg/kg/day divided into two times a day. Maintenance doses for 12 weeks: 20 mg/kg/day | Placebo | Primary: median reduction in the number of drop seizures and total monthly seizures. Secondary: change in the overall impression of caregivers ant patients (S/CGIC); reduction in percentage of the number of seizures (25, 50, 75, and 100%); adverse events (number, type and severity) | 14 weeks |

| Thiele et al. 22 | RCT | Pivotal phase 3 study; patients (n=255) with diagnostic tuberous sclerosis complex; age between 1 and 65 years; using more than one anticonvulsant drug, for more than 4 weeks. (Poland, Australia, Spain, the Netherlands, UK, and USA) | Staggered dose, with an increase of 5 mg, up to 25 or 50 mg/kg/day, divided into two doses per day. Maintenance doses for 12 weeks: 25 or 50 mg/kg/day | Placebo | Primary: reduction in the number of seizures. Secondary: proportion of patients with a 50% reduction in the number of seizures, change in the overall impression of patients and caregivers (S/CGIC) and adverse events | 14 weeks |

DS: Dravet syndrome; LGS: Lennox-Gastaut syndrome; RCT: randomized controlled trial.

Table 2. Quality of evidence (GRADE).

| Cannabidiol compared to placebo for seizures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Outcomes | Number of participants (studies) follow-up | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95%CI) | Potential absolute effects | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk difference with cannabidiol | ||||

| Absolute reduction in seizures follow-up: range 12–16 weeks | 726 (5 ECRs) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderatea | not priceless | 188 per 1,000 | 188 less per 1,000 (188 less for 188 less) |

| Number of patients with a reduction equal to or greater than 50% in seizures follow-up: range 12–16 weeks | 726 (5 ECRs) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | RR 1.88 (1.50 to 2.35) | 224 per 1,000 | 197 more per 1,000 (112 more to 303 more) |

| Number of patients without seizures follow-up: range 12–16 weeks | 726 (5 ECRs) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderateb | RR 4.29 (1.24 to 14.87) | 6 per 1,000 | 18 more per 1,000 (1 more to 77 more) |

| Improvement of clinical impression evaluated by patient or caregiver (S/CGIC) follow-up: range from 12–16 weeks | 726 (5 ECRs) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | RR 1.54 (1.32 to 1.80) | 385 per 1,000 | 208 more per 1,000 (123 more to 308 more) |

| Total adverse events follow-up: range 4–16 weeks | 733 (5 ECRs) | ⨁'very Lowb,c | RR 1.15 (1.00 to 1.32) | 801 per 1,000 | 120 more per 1,000 (0 less for 256 more) |

| Severe adverse events follow-up: range 12–16 weeks | 727 (5 ECRs) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderated | RR 3.25 (1.56 to 6.74) | 72 per 1,000 | 162 more per 1,000 (40 more to 413 more) |

| Risk of treatment abandonment follow-up: range 4–16 weeks | 741 (6 ECRs) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | RR 8.70 (3.80 to 19.89) | 14 per 1,000 | 105 more per 1,000 (38 more to 257 more) |

| Number of patients with transaminase elevation equal to or greater three times the follow-up reference: range 4–16 weeks | 721 (6 ECRs) | ⨁⨁’ Low | RR 11.20 (4.03 to 31.16) | 5 per 1,000 | 55 more per 1,000 (16 more to 164 more) |

| The risk in the intervention group (and its 95%CI) is based on the risk assumed from the comparator group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95%CI). RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| |||||

Explanations

Heterogeneity equal to 77%.

Wide confidence interval.

Heterogeneity equal to 83%.

Heterogeneity equal to 72%.

e. Heterogeneity equal to 85%.

Figure 1. Evidence retrieval and selection diagram 26 .

The six RCTs enrolled 1,034 patients with DS, LGS, and TSC, with 485 patients undergoing treatment with CBD (all dosages) compared to 325 placebo patients. This population was followed to measure the outcomes of reduction in the frequency of seizures and total seizures (all types), number of patients with response greater than or equal to 50%, change in CGIC, AEs, and tolerability to treatment. The follow-up was 14–16 weeks after the start of treatment (Table 3).

Table 3. Risk of biases from randomized clinical trials studies included.

| Study | Random | Blind folded allocation | Double-blind | Blinding of the evaluator | Losses <20% | Characteristic prognostic | Outcome | Simple size calculation | Early interruption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devinsky et al. 17 | |||||||||

| Devinsky et al. 18 | |||||||||

| Miller et al. 19 | |||||||||

| Devinsky et al. 20 | |||||||||

| Thiele et al. 21 | |||||||||

| Thiele et al. 22 |

Red: presence; green: absence; yellow: risk of unclear bias.

These patients who had previously participated in the RCTs were allowed to continue in an OLE study for each pivotal study (Table 1), evaluating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of CBD in the long term (median on days ranging from 267 to 1,090; n=880).

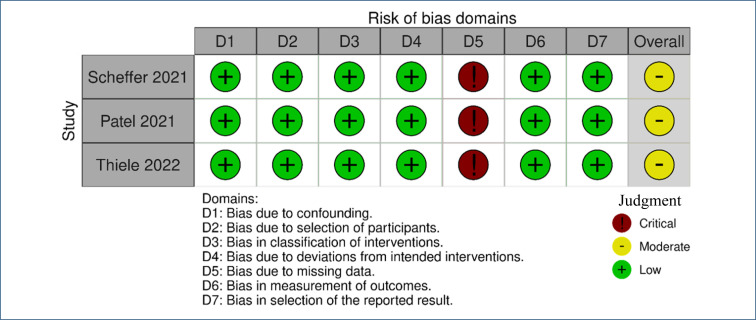

Risk of bias in included studies

For this update of the review, a combination of two out of three review authors (from AS, IF, and WB) independently re-assessed the risk of bias in each included trial according to predefined criteria stated in the Methods section (Table 3 and Figure 2) 27 .

Figure 2. Risk-of-bias plot – result of the risk assessment of bias of the observational cohort studies (“open-label extension”) included 27 .

Regarding the risk of bias of the six RCTs included 13–17,27 , none of them were blinded by the evaluator and one did not perform a sample calculation, and the overall risk of the studies may be considered nonsevere (Table 3).

The assessment of the risk of bias in the observational cohort OLE studies was made with the use of the ROBINS-I tool. The three studies included 23–25 presented a risk of critical bias to the loss domain (bias due to missing data), while all other domains presented a low risk of bias. Therefore, the overall risk of bias can be considered moderate (Figure 2).

Results of randomized clinical trials

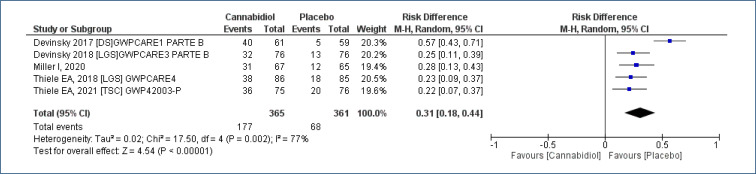

Five studies18-22, assessing 726 participants, allowed the evaluation of the outcome “absolute reduction in seizures” treated with CBD as compared to placebo, with a follow-up time of 12–16 weeks. This analysis demonstrated increase in the number of patients who obtained absolute reduction in the frequency of seizures [risk difference (RD)=0.31 (95%CI 0.18–0.44; I2=77%)], NNT=3. Moderate evidence quality (Analysis 1.1; Figure 3 and Table 2).

Figure 3. Meta-analysis of the results of absolute reduction in seizures with cannabidiol 17,18,21,22 .

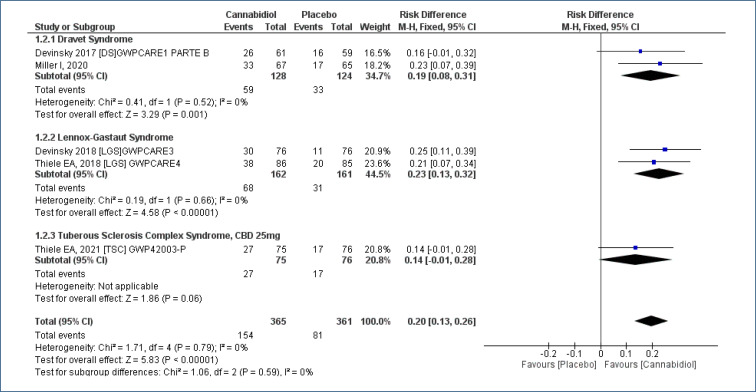

Meta-analysis of five studies18-22, assessing 726 participants, found there was an increased in the “number of patients with ≥50% reduction in seizures” for treatment with CBD as compared to placebo, and the follow-up time was 12–16 weeks [RD=0.20 (95%CI 0.13–0.26; I2=0%)], NNT=5. High evidence quality (Analysis 1.2; Figure 4 and Table 2).

Figure 4. Meta-analysis of the results of reduction equal to or greater than 50% in seizures 17–19,21,22 .

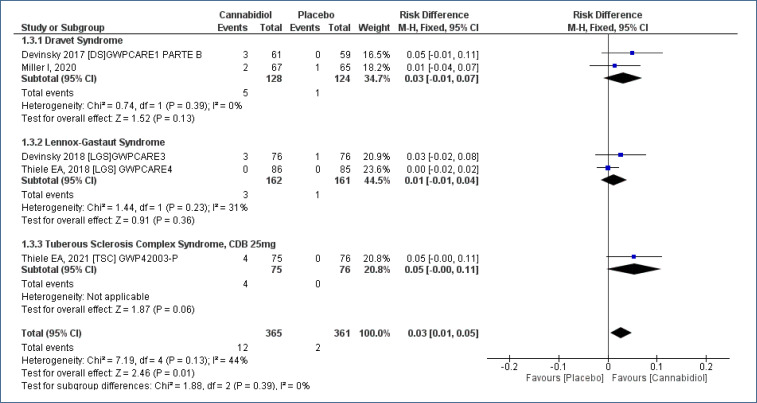

Five studies18-22, assessing 726 participants, have been submitted for a meta-analysis and demonstrated a less difference in the outcome “number of patients with absence of seizures” comparing treatment CBD as to placebo, with a follow-up time of 12–16 weeks [RD=0.03 (95%CI 0.01–0.03; I2=44%)]. Moderate evidence quality (Analysis 1.3; Figure 5 and Table 2).

Figure 5. Meta-analysis of the results of patients with absence of seizures and use of cannabidiol 17–19,21,22 .

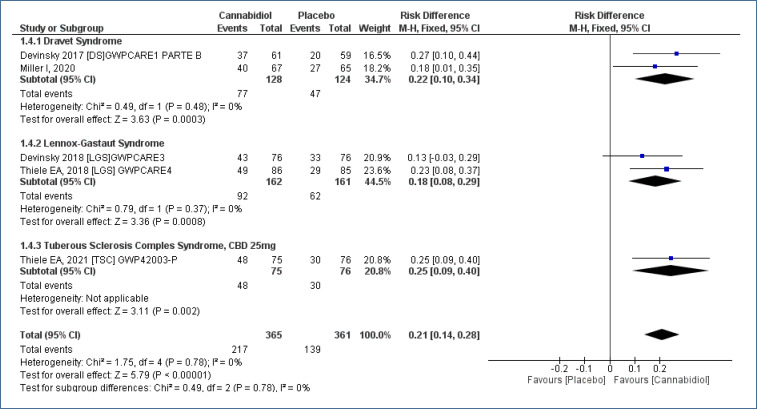

The CGIC (7-point Subject/Caregiver Global Impression of Change, S/CGIC), evaluated through a questionnaire with seven items [improvement (mild, moderate, or intense), worsening (mild, moderate, or intense), and without change] was applied to caregivers and patients. Five studies18-22, assessing 726 participants, with a follow-up time of 12–16 weeks, demonstrated improved in S/CGIC. In the patients who received CBD as compared to placebo [RD=0.21 (95%CI 0.14–0.28; I2=0%)], NNT=5. High evidence quality (Analysis 1.4; Figure 6 and Table 2).

Figure 6. Meta-analysis of the results of caregiver global impression of change 17–19,21,22 .

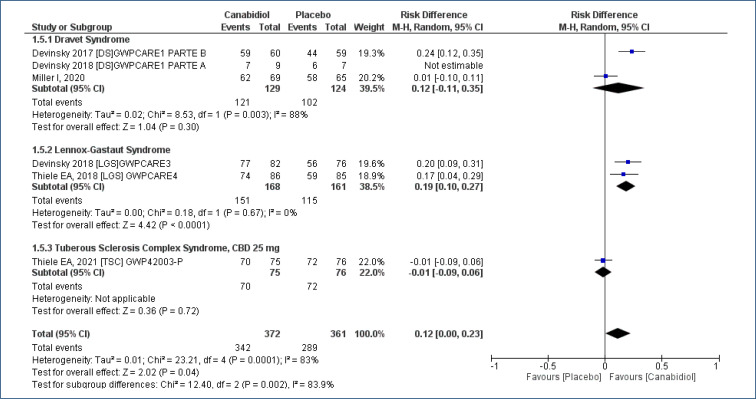

AEs, six studies17-22, assessing 733 participants, evaluated the “frequency of total adverse events” (any), with a follow-up time of 4–16 weeks, comparing the use of CBD to placebo. This analysis demonstrated an increase in the risk of AEs with the use of CBD in the treatment of DS, LGS, and TSC [RD=0.21 (95%CI 0.14–0.28; I2=83%)], NNT=8. Very low evidence quality (Analysis 1.5; Figure 7 and Table 2).

Figure 7. Meta-analysis of the results of total adverse events 17–19,21,22 .

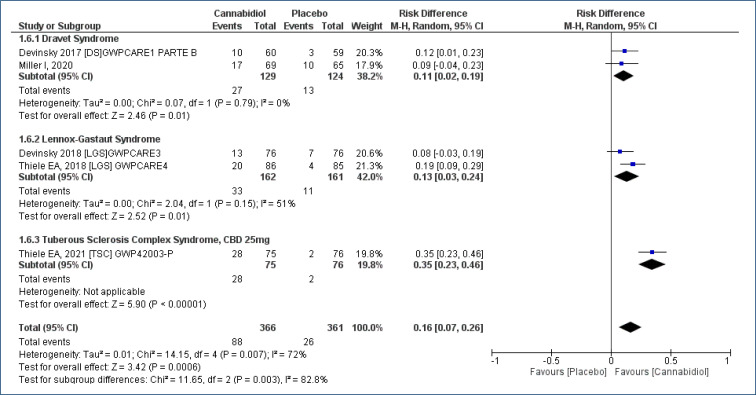

The frequency of “severe adverse events” was evaluated in five studies18-22, assessing 727 participants, and the follow-up time was 12–16 weeks. This analysis demonstrated an increased risk of serious AEs with the use of CBD when compared to placebo [RD=0.16 (95%CI 0.07–0.26; I2=72%)], NNT=6. Moderate evidence quality (Analysis 1.6; Figure 8 and Table 2).

Figure 8. Meta-analysis of the results of severe adverse events with cannabidiol 17–19,21,22 .

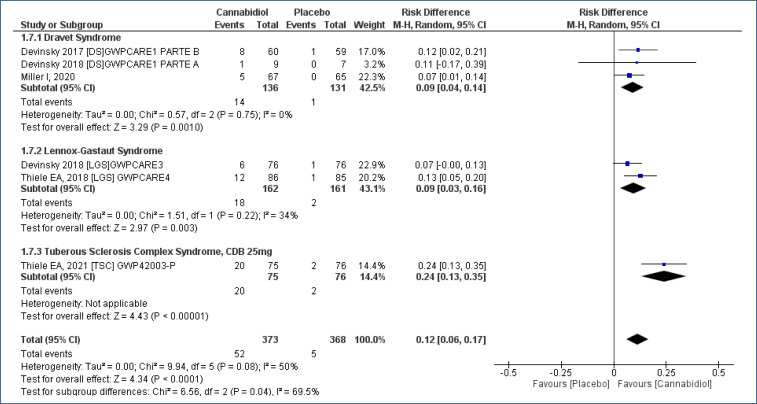

The “risk of treatment abandonment” was evaluated in six studies17-22, assessing 741 participants, and the follow-up time was 4–16 weeks. CBD increased the risk of treatment abandonment in the patients who received CBD as compared to placebo [RD=0.12 (95%CI 0.06–0.17; I2=50%)], NNH=8. High evidence quality (Analysis 1.7; Figure 9 and Table 2).

Figure 9. Meta-analysis of the results of the risk of abandonment to cannabidiol treatment 17–19,21,22 .

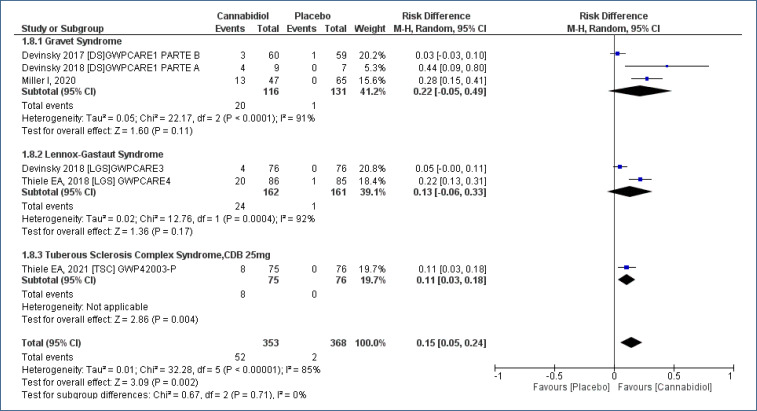

Meta-analysis of studies17-22, assessing 721 participants, with a follow-up time of 4–16 weeks, evaluated the number of patients with “transaminase elevation (≥3 times the reference)” comparing the use of CBD to placebo. This analysis demonstrated an increased risk of transaminase elevation ≥3 times the reference value in patients who received CBD, as compared to placebo [RD=0.15 (95%CI 0.05–0.24; I2=85%)], NNH=6. Low evidence quality (Analysis 1.8; Figure 10 and Table 2).

Figure 10. Meta-analysis of the results of the elevation of transaminases ≥3 times the reference 17–19,21,22 .

RESULTS OF THE “OPEN-LABEL EXTENSION”

Safety and tolerability

Three OLE studies 23–25 allow the evaluation of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) in the use of CBD, in different types of primary seizures, and in the long term (median treatment time between 267 and 1,090 days). AEs for LGS, DS, and CTS groups are summarized by pathology in Table 4.

Table 4. Summary of adverse events emerging from cannabidiol treatment for grouped (open-label extension) Lennox-Gataut syndrome, Dravet syndrome, and tuberous sclerosis complex, with median follow-up time of 267–1,090 days.

| Emerging adverse events of treatment during OLE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of adverse event | Dravet syndrome (n=315) n (%) | Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (n=366) n (%) | Tuberous sclerosis complex (n=199) n (%) | Total (n=880) n (%) |

| All TEAEs | 306 (97) | 353 (96.4) | 184 (92) | 843 (95.8) |

| Graves TEAEs | 132 (42) | 155 (42.3) | 29 (15) | 316 (36) |

| Abandonment due to adverse events | 28 (9) | 43 (11.7) | 12 (6) | 83 (9.4%) |

| Elevated hepatic transaminases* (ALT or AST) >3 × higher | 69 (22%); 58 of which (84%) had concomitant use of valproic acid. | 55 (15%); 40 of which (73%) with concomitant use of valproic acid. | 17 (9%); 12 of which (71 %) with concomitant use of valproic acid | 141 (16) |

OLE: open-label extension; TEAE: treatment-emergent adverse event.

Elevations of liver enzymes include only those reported as adverse events.

The majority (95.8%) of all patients had at least one TEAE during follow-up; there was no significant difference between disease groups (97% in DS, 96.4% in LGS, and 92% in TSC).

The incidence of severe AEs was much lower in the TSC group (29 [15%]) compared to that in DS (132 [42%]) and LGS (155 [42.3%]) groups; a similar result occurred with the elevation of transaminases (>70% had associated valproic acid). However, we should consider that the follow-up time for CST group [median of 267 (range 18–910) days] was shorter compared to that in DS [444 (18–1,535)] and LGS [1,090 (3–1,421)] groups.

The most commonly reported TEAEs were pyrexia and others related to the gastrointestinal tract, including diarrhea, vomiting, and reduced appetite, but also neurological issues including drowsiness.

Overall, the reported TEAEs, including the observed frequencies and severity, are comparable with previous observations of pivotal assays.

The percentage of patients who permanently discontinued treatment with CBD was 9.4% (n=83). The most common reasons were seizures and increased liver enzymes. Both are events known to cause the discontinuation of CBD treatment.

Summary of evidence

Randomized clinical trials

The use of CBD in patients with DS, LGS, and TSC as compared to placebo, follow-up time of 12–16 weeks:

Shows an absolute reduction in the frequency of seizures of 33%; three patients for one benefit (NNT=3) are needed. Moderate evidence quality.

Increases the number of patients with a 50% reduction in the frequency of seizures by 20%; NNT=5. High evidence quality.

Increases the number of patients with absence of seizures by 3%; NNT=33. Moderate evidence quality.

Improves the change in S/CGIC by 21%; NNT=5. High evidence quality.

Increases all AEs by 12%, and it is necessary to treat eight patients to obtain damage (NNH=8). Very low evidence quality.

Increases serious AEs by 16%; NNH=6. Quality of evidence was moderate.

Increases the risk of treatment abandonment by 12%; NNH=8. High evidence quality.

Increases the number of patients with transaminase elevation (≥3 times the reference) by 15%; NNH=6. Low evidence quality.

Observational studies’ cohort “open-label extension”

In treatment with CBD of different types of primary seizure, in the long term (follow-up median 1–3 years):

95.8% of all patients have at least one TEAE with CBD;

The rate of severe TEAEs can be up to 36%;

Transaminase levels (ALT, AST), ≥3 times the reference, may occur in 16% of patients;

The most commonly reported TEAEs are pyrexia, diarrhea, vomiting, reduced appetite, and drowsiness;

The percentage of patients who can permanently discontinue treatment with CBD is 9.4%. The most common reasons are seizures and increased liver enzymes.

These results have a very low evidence quality.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review, with meta-analysis, supports the use of CBD in the treatment of patients with seizures, originating in DS, LGS, and TSC, who are resistant to the common medications, satisfactory benefits in reducing seizures, and tolerable toxicity.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received funding from the Unimed Regional da Baixa Mogiana.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wężyk K, Słowik A, Bosak M. Predictors of remission in patients with epilepsy. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2020;54(5):434–439. doi: 10.5603/PJNNS.a2020.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, Brodie MJ, Hauser WA, Mathern G, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2010;51(6):1069–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resnick T, Sheth RD. Early diagnosis and treatment of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2017;32(11):947–955. doi: 10.1177/0883073817714394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourgeois BFD, Douglass LM, Sankar R. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: a consensus approach to differential diagnosis. Epilepsia. 2014;55(Suppl 4):4–9. doi: 10.1111/epi.12567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montouris GD, Wheless JW, Glauser TA. The efficacy and tolerability of pharmacologic treatment options for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 2014;55(Suppl 4):10–20. doi: 10.1111/epi.12732. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12732. Erratum in: Epilepsia. 2015;56(6):984. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12958 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wirrell E. Infantile, childhood, and adolescent epilepsies. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(1 Epilepsy):60–93. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dravet C, Oguni H. Dravet syndrome (severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy) Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;111:627–633. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52891-9.00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace A, Wirrell E, Kenney-Jung DL. Pharmacotherapy for Dravet syndrome. Paediatr Drugs. 2016;18(3):197–208. doi: 10.1007/s40272-016-0171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Northrup H, Krueger DA, International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49(4):243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devinsky O, Cilio MR, Cross H, Fernandez-Ruiz J, French J, Hill C, et al. Cannabidiol: pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia. 2014;55(6):791–802. doi: 10.1111/epi.12631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cilio MR, Thiele EA, Devinsky O. The case for assessing cannabidiol in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55(6):787–790. doi: 10.1111/epi.12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372(71) doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898–l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.GRADE What is GRADE? [[cited on Aug. 20, 2021]]. Available from: https://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/

- 15.GRADEpro GDT. GRADEpro for UKRAINE GRADE your evidence and improve your guideline development in health care. [[cited on May 20, 2022]]. Available from: https://www.gradepro.org/

- 16.Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program] Version 5.4. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2020. [[cited on May 1, 2022]]. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/system/files/uploads/protected_file/RevMan5.4_user_guide.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devinsky O, Cross JH, Wright S. Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the Dravet syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(7):699–700. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1708349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devinsky O, Patel AD, Thiele EA, Wong MH, Appleton R, Harden CL, et al. Randomized, dose-ranging safety trial of cannabidiol in Dravet syndrome. Neurology. 2018;90(14):e1204–e1211. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller I, Scheffer IE, Gunning B, Sanchez-Carpintero R, Gil-Nagel A, Perry MS, et al. Dose-ranging effect of adjunctive oral cannabidiol vs placebo on convulsive seizure frequency in Dravet syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(5):613–621. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.0073. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.0073. Erratum in: JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(5):655. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.0749 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devinsky O, Patel AD, Cross JH, Villanueva V, Wirrell EC, Privitera M, et al. Effect of cannabidiol on drop seizures in the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1888–1897. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiele EA, Marsh ED, French JA, Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska M, Benbadis SR, Joshi C, et al. Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (GWPCARE4): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1085–1096. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thiele EA, Bebin EM, Bhathal H, Jansen FE, Kotulska K, Lawson JA, et al. Add-on cannabidiol treatment for drug-resistant seizures in tuberous sclerosis complex: a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(3):285–292. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheffer IE, Halford JJ, Miller I, Nabbout R, Sanchez-Carpintero R, Shiloh-Malawsky Y, et al. Add-on cannabidiol in patients with Dravet syndrome: results of a long-term open-label extension trial. Epilepsia. 2021;62(10):2505–2517. doi: 10.1111/epi.17036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel AD, Mazurkiewicz-Bełdzińska M, Chin RF, Gil-Nagel A, Gunning B, Halford JJ, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of add-on cannabidiol in patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: results of a long-term open-label extension trial. Epilepsia. 2021;62(9):2228–2239. doi: 10.1111/epi.17000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thiele EA, Bebin EM, Filloux F, Kwan P, Loftus R, Sahebkar F, et al. Long-term cannabidiol treatment for seizures in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: an open-label extension trial. Epilepsia. 2022;63(2):426–439. doi: 10.1111/epi.17150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919–i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]