Abstract

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) as a devastating neurological disorder is closely related to heightened oxidative insults and neuroinflammatory injury. Pinocembrin, a bioflavonoid, exhibits different biological functions, such as immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and cerebroprotective activities. Herein, we examined the protective effects and molecular mechanisms of pinocembrin in a murine model of SAH. Using an endovascular perforation model in rats, pinocembrin significantly mitigated SAH-induced neuronal tissue damage, including inflammatory injury and free-radical insults. Meanwhile, pinocembrin improved behavior function and reduced neuronal apoptosis. We also revealed that sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) activation was significantly enhanced by pinocembrin. In addition, pinocembrin treatment evidently enhanced peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator expression and suppressed ac-nuclear factor-kappa B levels. In contrast, EX-527, a selective SIRT1 inhibitor, blunted the protective effects of pinocembrin against SAH by suppressing SIRT1-mediated signaling. These results suggested that the cerebroprotective actions of pinocembrin after SAH were through SIRT1-dependent pathway, suggesting the potential application of pinocembrin for the treatment of SAH.

1. Introduction

The outcome of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in clinical practice is still very poor [1–3]. SAH occurs when a cerebral aneurysm ruptures and involves a variety of pathogenic mechanisms. A great deal of preclinical and clinical researches has observed that a deteriorated inflammatory injury and heightened free-radical damage exacerbated cerebrovascular injury and might explain the poor outcome after SAH [4–6]. In addition, cerebral vasospasm and the delayed cerebral ischemia contribute to the long-term neurological deficits. Diminishing neuroinflammation and oxidative stress could also ameliorate cerebral vasospasm as well as the delayed cerebral ischemia after SAH [7, 8]. Thus, targeting cerebral inflammatory injury and free-radical insults would improve brain recovery after SAH, but effective therapies are lacking.

Increasing evidence has indicated that medicinal plants and their active ingredients may help to find new promising therapeutic drugs for central nervous system (CNS) diseases. Pinocembrin, a natural compound distributed in propolis, shows immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, antifree radical, and anticytotoxicity properties [9]. A great deal of research has demonstrated the promising effects of pinocembrin against various CNS diseases including ischemic brain injury, hemorrhagic brain injury, traumatic brain injury, psychiatric disorders, and neurodegenerative disorders [9–12]. In a model of intracerebral hemorrhage, pinocembrin significantly mitigated hemorrhagic brain injury by suppressing toll-like receptor 4 and reducing M1 microglia [9]. In another study, pinocembrin reduced neuronal damage in hippocampus and improved cognitive function by inhibiting autophagy in a cerebral ischemia/reperfusion model [13]. Meanwhile, numerous studies have indicated that pinocembrin could pass the blood-brain barrier [9, 14]. Due to its different pharmacological functions and no associated toxicities, pinocembrin has great potential for treating neurovascular diseases. However, much less is known about the efficacy of pinocembrin in SAH and its implicated mechanisms.

Sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) is a histone deacetylase that is widely distributed in cerebral cortex. Accumulating preclinical evidence has indicated that SIRT1 is a promising molecular candidate for SAH [15–17]. By deacetylating a variety of intracellular targets such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator (Pgc-1α) and ac-nuclear factor-kappa B (ac-NF-κB), SIRT1 provides protection in reduction of inflammatory injury, free radical damage, and cell death [18, 19]. Intriguingly, pinocembrin is able to modulate SIRT1 signaling in many diseases [20, 21]. However, it remains unknown the effects of pinocembrin on brain tissue damage caused by SAH and whether pinocembrin can activate SIRT1 and its downstream targets. Therefore, we examined whether pinocembrin protects against SAH insults and focused on SIRT1-depdent pathway.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and In Vivo Model

All experimental studies were conformed to the ARRIVE guidelines [22]. Adult male-SD rats (weighing 250-300 g) were acquired from the Animal Center of Fujian University. Rat model of endovascular perforation SAH was built in accordance with previous protocols [16, 23]. Before SAH, 1% sodium pentobarbital was administered by intraperitoneal injection. A marked 4-0 filament was employed to puncture the origin of the left middle cerebral artery from the left internal carotid artery. Sham-treated animals received a similar procedure without vessel perforation. Following surgery, all rats were administered with buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg) to relieve the pain. A total of 253 rats (33 rats died and 6 rats were excluded) were used. Animal groups and mortality rates can be seen in Supplementary table 1.

2.2. Drug Administration

Pinocembrin (Sigma-Aldrich) was resolved in 20% hydroxypropyl-b-cyclodextrin before use. Pinocembrin (10, 20, and 40 mg/kg) or vehicle was administered by oral gavage at 2 h after surgery and then once a day [24]. Resveratrol (RSV, Sigma-Aldrich), a positive SIRT1 activator, was used as a positive control drug. RSV (60 mg/kg) was resolved in 1% DMSO and administered intraperitoneally at 2 h after surgery and then once a day. The dose of RSV and injection route were based on previous studies [25]. Ex-527 (10 mg/kg) (Sigma-Aldrich) or vehicle (1% DMSO) was administered intraperitoneally for 3 days before surgery [26]. Experiment design can be seen in Supplementary Figure 1.

2.3. Determination of Oxidative Stress-Related Markers

The lipid peroxidation in the brain tissue was evaluated by estimation malondialdehyde (MDA). The absorbance at 532 nm was used to determine MDA content. The endogenous antioxidants including glutathione (GSH), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT) were determined in line with the manufacturers' instructions (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute).

2.4. ELISA Assay

Supernatants from rat brains were assayed for rat IL-1β, rat IL-6, and rat ICAM-1 by specific ELISA kits. The exact protocols were conducted in line with the manufacturer's instructions. The total protein levels in each sample were assessed with BCA method.

2.5. Immunoblotting Analysis

The same mass of supernatants were loaded onto SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocking and then hatched with specific Abs overnight at 4°C. After that, the secondary Abs were hatched with these membranes. ECL kits were used to reveal the protein bands. Abs used can be seen in Supplementary material.

2.6. Immunofluorescence Staining

Brain sections were treated following the standard procedures [5, 27]. Briefly, brain sections were fixed with 4% PFA and subsequently with 5% BSA. After that, slides were stained with primary Abs and appropriate secondary Abs. The nuclei were shown by 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining. Abs used for this experiment can be seen in Supplementary table 2.

2.7. TUNEL Assay

TUNEL assay (Beyotime Biotechnology) was used to determine neuronal apoptosis. Frozen brain sections were treated following the standard procedures by the manufacturer. The nuclei were revealed by staining with DAPI. The apoptotic cells were captured using a fluorescence microscope.

2.8. Nissl Staining and H&E Staining

Nissl staining and H&E staining were used to determine post-SAH brain tissue pathological changes. In accordance with the standard protocols [28], brain sections were stained with cresol violet or hematoxylin and then cover-slipped in Permount. The surviving neurons were observed with a light microscope.

2.9. Behavior Function

The neurologic deficits of SAH rats were determined by using the mNSS method [29]. The rotarod test was conducted to evaluate post-SAH motor deficits [30]. Before surgery, animals needed training for 3 days. The average time to fall off was recorded. Beam walking test was conducted blindly according to a previous study by Zhang et al. [28]. Before the normal beam walking test, rats were pretrained for 3 days.

2.10. Brain Water Content Analysis

As previous studies reported [31], the intact brains were quickly divided into two parts including contralateral and ipsilateral hemispheres. Each part was weighed immediately (WW) and then dried in an oven. After that, each part was weighted again (DW). Brain edema ratio = (WW − DW)/WW × 100%.

2.11. Statistics

Data was expressed as mean ± s.d. Student's t-test was used when comparing two groups. For beam walking test, two-way analysis of variance with Tukey post hoc test was conducted. One-way analysis of variance with Tukey post hoc test was conducted for other data. The GraphPad Prism was employed for statistics. Probability value < 0.05 was considered significantly different.

3. Results

3.1. Pinocembrin Mitigated Brain Edema and Neurological Impairment and Enhanced SIRT1 Expression following SAH

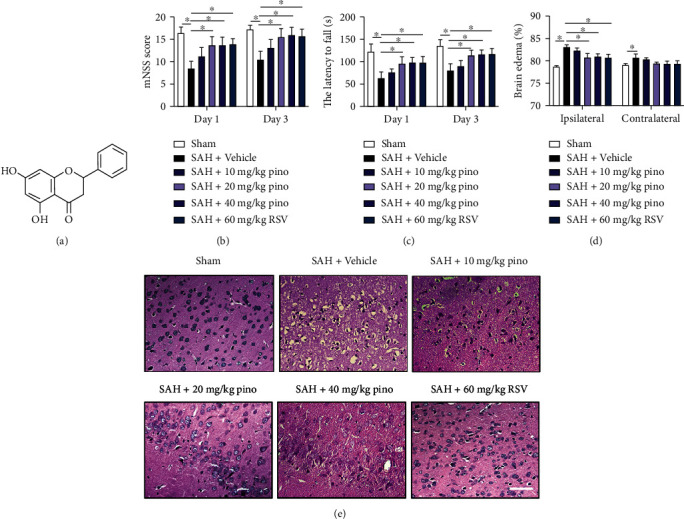

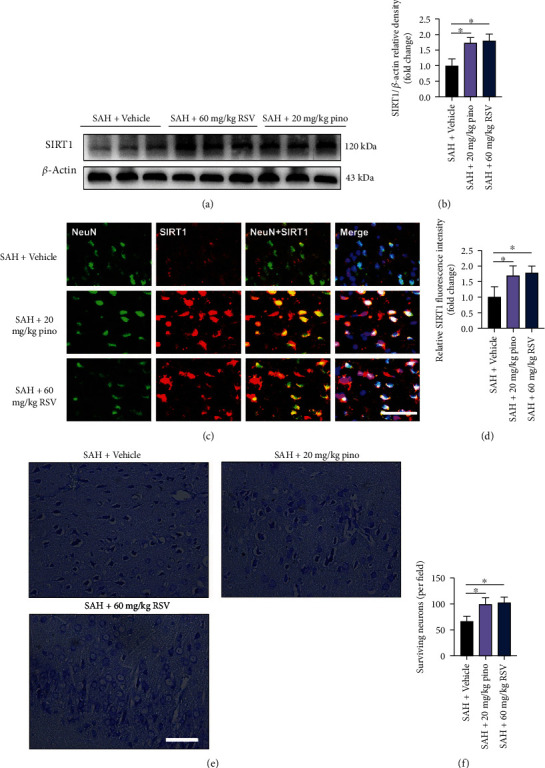

Accumulating evidence has indicated that RSV could significantly reduce EBI and improve neurological outcome after SAH; RSV was employed as a positive control drug. Figure 1(a) shows the chemical structure of pinocembrin. It indicated that RSV and pinocembrin at doses of 20 and 40 mg/kg evidently decreased post-SAH neurological deficient scores and motor impairment (P < 0.05) (Figures 1(b) and 1(c)). But 10 mg/kg pinocembrin failed to improve post-SAH neurological outcome. Additionally, RSV and pinocembrin administration at 20 and 40 mg/kg markedly mitigated post-SAH brain edema as well as histopathological impairment (P < 0.05) (Figures 1(d) and 1(e)). Our data indicated that 20 mg/kg was the optimal dose after SAH. We then evaluated the effects of pinocembrin on SIRT1 expression after SAH. Western blotting data and immunofluorescence staining results showed that both RSV and pinocembrin significantly enhanced SIRT1 levels in the brain tissue following SAH (P < 0.05) (Figures 2(a)–2(d)). Meanwhile, Nissl staining indicated that both RSV and pinocembrin improved post-SAH neuronal survival (P < 0.05) (Figures 2(e) and 2(f)).

Figure 1.

Pinocembrin improved neurological function and reduced brain edema after SAH. (a) The chemical structure of pinocembrin. The mNSS score (b) and rotarod tests (c) were analyzed at 24 and 72 h post-SAH. (d) The brain water content in all experimental groups was analyzed at 24 h post-SAH. (e) Representative photomicrographs of HE-stained images. Scale bar = 50 μm. Values were presented as mean ± SD, n = 6-10 per group. ∗P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Pinocembrin upregulated SIRT1 activation and improved histological outcomes after SAH. (a) Western blotting was used to analyze SIRT1 expression. (b) Pinocembrin increased SIRT1 expression after SAH. (c) Representative photomicrographs of SIRT1 staining in brain tissue at 24 h post-SAH. (d) Pinocembrin resulted in enhanced SIRT1 staining at 24 h post-SAH. (e) Representative photomicrographs of cresyl violet-stained images. (f) Pinocembrin improved neuronal survival at 72 h post-SAH. Scale bar = 50 μm. Values were presented as mean ± SD, n = 6 per group. ∗P < 0.05.

3.2. Pinocembrin Activated SIRT1-Mediated Signaling after SAH

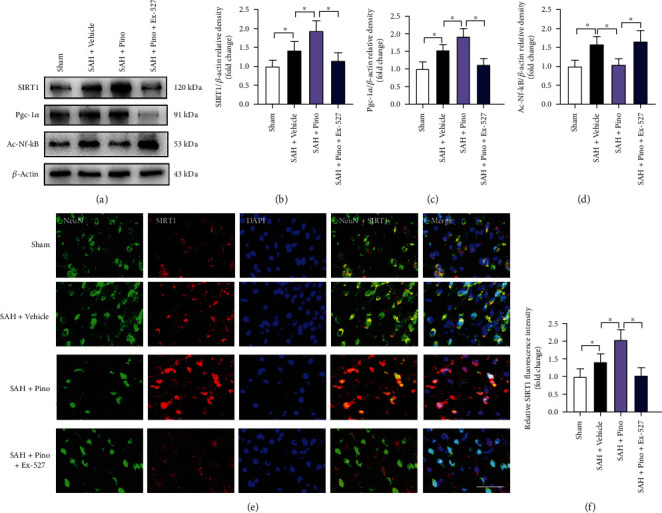

Pgc-1α, the downstream target of SIRT1, plays a crucial in regulating oxidative metabolism and cell survival. In addition, SIRT1 can deacetylate RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB to suppress inflammatory injury. As shown, our data revealed that pinocembrin evidently enhanced the expressions of SIRT1 and Pgc1-α and decreased the protein levels of ac-NF-κB after SAH (P < 0.05) (Figures 3(a)–3(d)). Ex-527 treatment validated the interaction between pinocembrin and SIRT1 signaling. It showed that Ex-527 suppressed the enhanced SIRT1 and Pgc1-α by pinocembrin and further aggravated post-SAH ac-NF-κB expression (P < 0.05) (Figures 3(a)–3(d)). Similarly, immunofluorescence staining results indicated that pinocembrin enhanced post-SAH SIRT1 activation, which could be reversed by Ex-527 (P < 0.05) (Figures 3(e) and 3(f)).

Figure 3.

Pinocembrin activated SIRT1-mediated signaling following SAH. (a) Protein bands of SIRT1, Pgc-1a, and ac-NF-κB after pinocembrin treatment. Pinocembrin upregulated SIRT1 (b) and Pgc-1a (c) levels and suppressed ac-NF-κB (d) expression after SAH. (e) Representative photomicrographs of SIRT1 staining in brain tissue at 24 h post-SAH. (f) Pinocembrin resulted in enhanced SIRT1 staining at 24 h post-SAH. Scale bar = 50 μm. Values were presented as mean ± SD, n = 6 per group. ∗P < 0.05.

3.3. Pinocembrin Inhibited Free Radical Damage after SAH

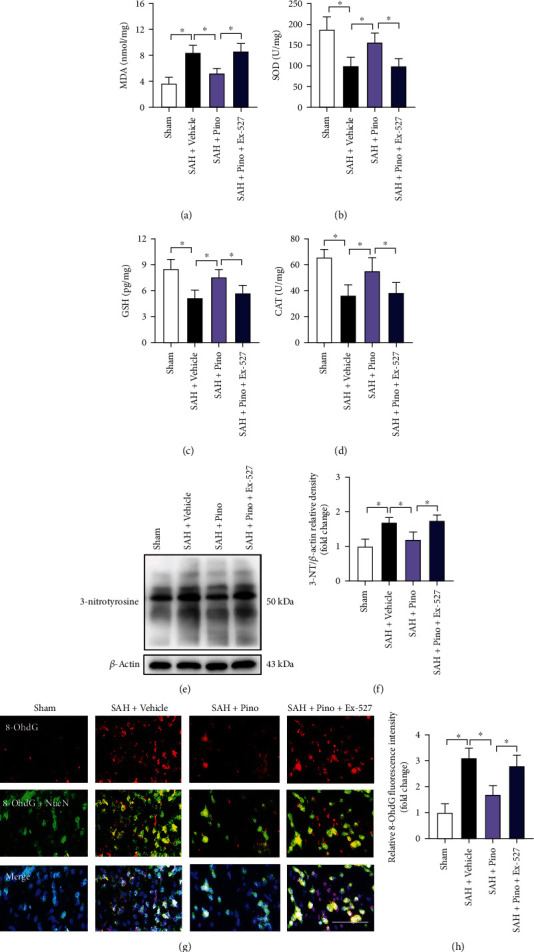

Free radical insults contribute greatly to SAH-induced brain injury. As shown, SAH insults aggravated lipid peroxidation and decreased the endogenous antioxidant enzyme activities. On the contrary, pinocembrin exhibited decreased levels of MDA and high intracellular endogenous antioxidant enzyme activities (P < 0.05) (Figures 4(a)–4(d)). Western blot and immunofluorescence staining results further showed that SAH significantly increased the formation of nitrotyrosine and 8-OhdG immunity, which could be abated by pinocembrin (P < 0.05) (Figures 4(e)–4(h)). In contrast, the specific inhibitor of SIRT1, Ex-527, significantly abrogated the antifree radical insults of pinocembrin after SAH (P < 0.05) (Figures 4(a)–4(h)).

Figure 4.

Pinocembrin alleviated free radical injury after SAH. Measurement of intracellular MDA (a), SOD (b), GSH (c), and CAT (d) after pinocembrin treatment. (e) Protein bands of 3-nitrotyrosine after pinocembrin treatment. (f) Pinocembrin suppressed 3-nitrotyrosine expression after SAH. (g) Representative images of 8-OhdG staining in brain tissue. (h) Pinocembrin resulted in decreased 8-OhdG staining at 24 h post-SAH. In contrast, Ex-527 abrogated the antifree radical effects of pinocembrin. Scale bar = 50 μm. Values were presented as mean ± SD, n = 6 per group. ∗P < 0.05.

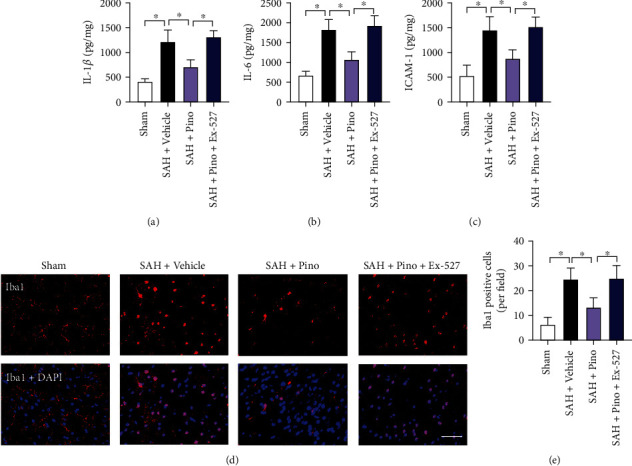

3.4. Pinocembrin Inhibited Post-SAH Inflammatory Injury

Neuroinflammation is also essential to how SAH develops. As shown, SAH markedly triggered microglia activation in the brain as well as the inflammatory cytokine secretion. In contrast, pinocembrin evidently suppressed the acute inflammatory injury after SAH (P < 0.05) (Figures 5(a)–5(e)). Ex-527 was administered before SAH induction. As expected, animals pretreated with Ex-527 blunted the anti-inflammatory effects of pinocembrin on SAH (P < 0.05) (Figures 5(a)–5(e)).

Figure 5.

Pinocembrin mitigated post-SAH inflammatory injury. ELISA was used to detect proinflammatory cytokine release. Pinocembrin decreased the levels of IL-1β (a), IL-6 (b), and ICAM-1 (c) after SAH damage. (d) Representative photomicrographs of Iba1 staining in brain tissue at 24 h post-SAH. (e) Pinocembrin resulted in decreased microglia activation at 24 h post-SAH. In contrast, Ex-527 abrogated the anti-inflammatory effects of pinocembrin. Scale bar = 50 μm. Values were presented as mean ± SD, n = 6 per group. ∗P < 0.05.

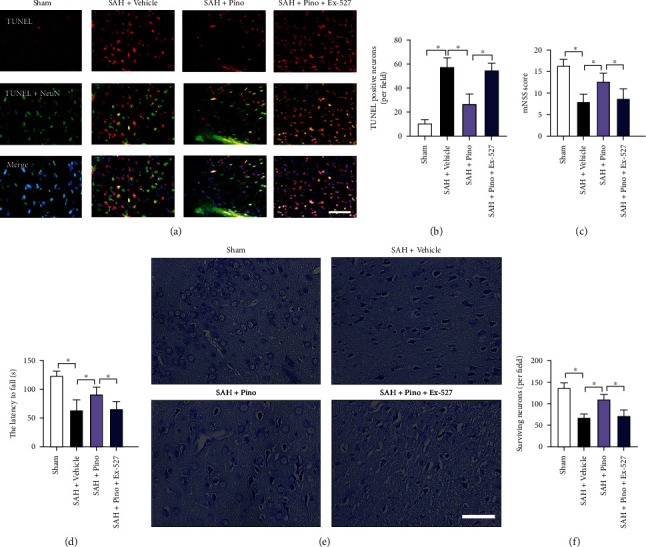

3.5. Pinocembrin Ameliorated Neuronal Death and Behavior Impairment after SAH

Neuronal death is closely associated with poor outcome after SAH. Both free radical insults and inflammatory injury could aggravate post-SAH neuronal apoptosis. We suspected that pinocembrin could also reduce neuronal apoptosis and improve neurological function by inhibiting oxidative and inflammatory-related damage. TUNEL staining showed that SAH dramatically aggravated neuronal apoptosis in the brain cortex, which could be statistically suppressed by pinocembrin (P < 0.05) (Figures 6(a) and 6(b)). Meanwhile, the aggravated neurological deficits and motor impairment by SAH could be blunted by pinocembrin (P < 0.05) (Figures 6(c) and 6(d)). However, all these changes were counteracted by Ex-527 pretreatment (P < 0.05). Nissl staining further indicated that pinocembrin improved neuronal survival subjected to SAH insults, which could be abrogated by Ex-527 (P < 0.05) (Figures 6(e) and 6(f)).

Figure 6.

Pinocembrin reduced neuronal apoptosis and improved neurological outcomes after SAH. (a) Representative photomicrographs of TUNEL staining in brain tissue at 24 h post-SAH. (b) Pinocembrin decreased neuronal apoptosis at 24 h post-SAH. Pinocembrin improved mNSS score (c) and motor behavior (d) after SAH. Ex-527 abated the cerebroprotective effects of pinocembrin after SAH. (e) Representative photomicrographs of cresyl violet-stained images. (f) Pinocembrin improved neuronal survival at 72 h post-SAH, which could be reversed by Ex-527 pretreatment. Scale bar = 50 μm. Values were presented as mean ± SD, n = 6-10 per group. ∗P < 0.05.

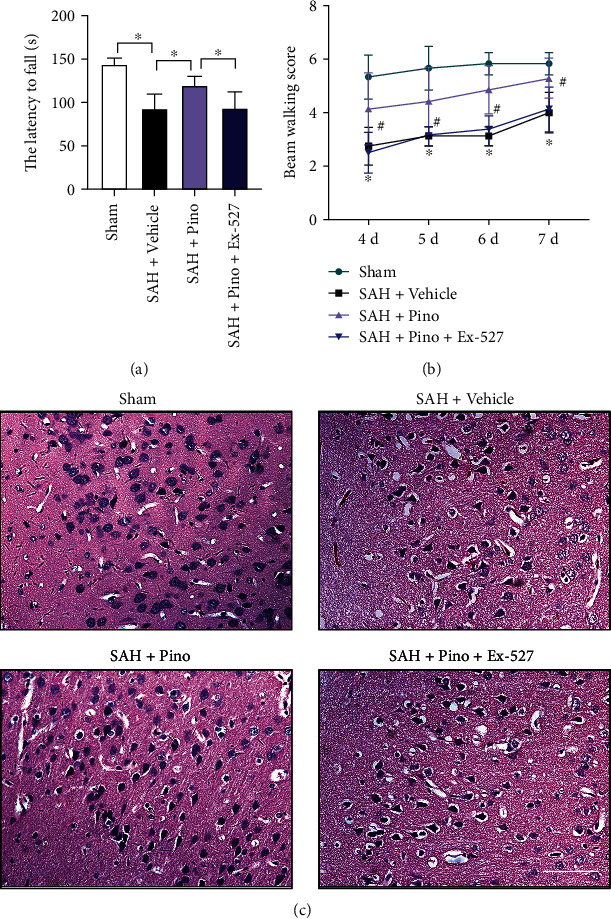

3.6. Pinocembrin Provided Long-Term Beneficial Effects after SAH

We further evaluated the long-term beneficial effects of pinocembrin after SAH. It showed that SAH insults induced significant neurological impairments at day 7 after SAH. Pinocembrin treatment significantly improved long-term neurobehavior function accessed by rotarod test and beam walking test (P < 0.05) (Figures 7(a) and 7(b)). In contrast, Ex-527 abated the long-term beneficial effects of pinocembrin against SAH (P < 0.05) (Figures 7(a) and 7(b)). H&E staining further indicated that pinocembrin reduced neuronal degeneration subjected to SAH insults, which could be abrogated by Ex-527 (P < 0.05) (Figure 7(c)).

Figure 7.

Pinocembrin improved the long-term outcome after SAH. Pinocembrin improved long-term neurobehavior function accessed by rotarod test (a) and beam walking test (b) at day 7 after SAH. In contrast, Ex-527 abated the cerebroprotective effects of pinocembrin after SAH. (c) Representative photomicrographs of H&E staining in brain tissue at day 7 post-SAH. Scale bar = 50 μm. Values were presented as mean ± SD, n = 6-8 per group. ∗P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

This study unraveled the efficacy of pinocembrin in a rat model of SAH. Our data showed that pinocembrin significantly mitigated behavior deterioration and brain tissue impairment after SAH as indicated by the decreased free radical insults, reduced inflammatory injury, and improved neuronal survival. Pinocembrin treatment also dramatically upregulated the concentrations of SIRT1 and Pgc-1α levels and suppressed ac-NF-κB expression. Conversely, inhibition of SIRT1 by Ex-527 abolished the neuroprotective effects of pinocembrin and the positive effects on SIRT1-dependent pathway (Supplementary figure 2). These novel findings suggest that pinocembrin alleviated early brain damage following SAH by modulation of SIRT1-dependent pathway.

The heightened free radical insults and cerebral inflammatory response play key roles in the pathological cascade of brain damage after SAH [32–35]. The CNS is particularly vulnerability to free radical insults. One reason is that the brain tissue is rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids. Further, free radicals are verified as the elemental triggers of neurotoxicity. After SAH, the microglia are also rapidly activated to amplify the inflammatory insults. The stimulated microglia and free radicals further deteriorate neuronal damage after SAH [36]. Therefore, targeting the free radical damage and inflammatory insults might counteract early brain damage after SAH.

Pinocembrin has numerous therapeutic properties such as immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, antifree radical, and anticytotoxicity functions [37]. Evidence from preclinical studies has verified the cerebroprotective action of pinocembrin on different CNS diseases. For example, Lan et al. reported that pinocembrin effectively inhibited postintracerebral hemorrhage neuroinflammation via reduction of M1 microglia and inhibition of NF-κB translocation [9]. Tao et al. have demonstrated that pinocembrin decreased ischemic insult-induced neuronal damage in cerebral ischemia by activation of autophagy [13]. However, little is known about the efficacy of pinocembrin in SAH model. In line with previous researches, rats treated with pinocembrin alleviated post-SAH inflammatory injury and free radical insults. Further, pinocembrin mitigated histological damages and behavior deterioration after SAH. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying pinocembrin's actions remain unknown.

Many researches have indicated that SIRT1 is a key target for treating SAH. SIRT1 plays an essential role in inflammatory and redox homeostasis [38–40]. Enhanced expression of SIRT1 could inhibit brain damage and prevent delayed cerebral ischemia in experimental SAH [41, 42]. By suppression of free radical damage, inflammatory insults, and microthrombi, SIRT1 prevents cerebral vasospasm and ameliorates neurological deficits after SAH. For example, RSV, a powerful SIRT1 activator, has been shown to prevent EBI, cerebral vasospasm, and delayed cerebral ischemia after SAH [41, 43]. In addition, a new study by Yuan et al. has demonstrated that RSV could ameliorate SAH-induced ferroptosis by activation of SIRT1 [44]. In view of these backgrounds, we used RSV as a positive control drug. Similarly, our data indicated that RSV significantly enhanced SIRT1 expression and provided protection against EBI after SAH. Intriguingly, pinocembrin is also able to modulate SIRT1-mediated signaling in other diseases. Cao et al. reported that pinocembrin ameliorated hepatocyte dysfunction-induced inflammatory response and oxidative damage through SIRT1/PPARα [20]. Another observation study by Guo et al. revealed that pinocembrin protected against hepatic steatosis through SIRT1/AMPK signaling [21]. Interestingly, our experiments also revealed that pinocembrin significantly enhanced SIRT1 after SAH.

Pgc-1α, a downstream target of SIRT1, plays a crucial in regulating oxidative metabolism [45, 46]. Pgc-1α could scavenge free radical overproduction by inducing the endogenous antioxidant enzymes [47]. Additionally, Pgc-1α could reduce neuronal apoptosis, improve neuronal survival, and maintain the integrity of blood-brain barrier [48, 49]. However, Pgc1-α requires SIRT1 deacetylation to be fully activated [17].NF-κB is a master regulator of neuroinflammatory injury in cerebrovascular diseases. In addition to phosphorylation, acetylation of NF-κB is also involved in the inflammatory response. It reported that SIRT1 can deacetylate RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB to suppress inflammatory injury [19]. Zhao et al. also indicated that SIRT1 activation with melatonin ameliorated EBI after SAH by decreasing the acetylation of NF-κB [50]. We then assessed the levels of Pgc1-α and ac-NF-κB after pinocembrin administration. Our data indicated that pinocembrin dramatically induced Pgc1-α expression and inhibited ac-NF-κB levels. More direct evidence validated the interaction between SIRT1 and pinocembrin. The specific inhibitor of SIRT1, Ex-527, successfully suppressed the enhanced expression of SIRT1 and Pgc1-α levels and decreased expression of ac-NF-κB by pinocembrin. Meanwhile, the evident cerebroprotective effects of pinocembrin were also abrogated when treated with Ex-527. Together with our data, these observations indicated that by interacting with SIRT1, pinocembrin protected post-SAH inflammatory injury, free radical insults, and neuronal damage.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, recent studies have indicated that SIRT1 could modulate microglia polarization, including inhibiting M1 microglia and promoting M2 microglia. In our study, pinocembrin inhibited microglia activation. However, the exact role of pinocembrin on different microglia phenotypes remains unknown. Secondly, a sterile neurogenic inflammation was also involved in the pathophysiology of SAH [51, 52]. It can induce mast cell activation and promote neurogenic inflammation [53]. Whether pinocembrin affect this sterile neurogenic inflammation remains unknown. Thirdly, in the present study, we mainly investigated the role of pinocembrin on SIRT1-mediated signaling pathway. In addition to SIRT1, other signaling targets might be involved in the protective effects of pinocembrin. Thus, additional preclinical experiments are still needed to clarify these issues.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we postulated that pinocembrin effectively mitigated early brain damage after SAH. By interacting with SIRT1, pinocembrin suppressed post-SAH inflammatory injury, free radical insults, and neuronal damage. Pinocembrin might be a promising therapeutic drug for human SAH.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the funds for Quanzhou City Science and Technology Program of China (2021N23S) from Dr. Yile Zeng, Young and Middle-Aged Backbone Talent Foundation of Fujian Provincial Commission of Health Construction (2020GGA058), and Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian Province (2020Y9033) from Dr. Xiangrong Chen.

Contributor Information

Xieli Guo, Email: 15960795588@139.com.

Xiangrong Chen, Email: xiangrong_chen281@126.com.

Data Availability

The data sets used in this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Yile Zeng, Xieli Guo, and Xiangrong Chen were responsible for the conceptualization. Yile Zeng, Zhongning Fang, Jinqing Lai, Zhe Wu, Weibin Lin, Hao Yao, Weipeng Hu, and Junyan Chen were responsible for the experiment conduction and formal analysis. Yile Zeng, Zhongning Fang, Xieli Guo, and Xiangrong Chen were responsible for the writing—review. Yile Zeng, Zhongning Fang, and Jinqing Lai contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: animal groups and mortality rates. Supplementary Table 2: the antibodies used in the study. Supplementary Figure 1: schematic illustration of experimental design. Supplementary Figure 2: the graphic abstract. Pinocembrin attenuated free radical insults, reduced inflammatory injury, and improved neuronal survival via the activation of SIRT1-dependent pathway after SAH.

References

- 1.Fang Y., Shi H., Huang L., et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide attenuates mitochondria- mediated oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Free Radical Biology & Medicine . 2021;174:236–248. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macdonald R. L., Schweizer T. A. Spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet . 2017;389(10069):655–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30668-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macdonald R. L. Age and outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry . 2021;92(11):p. 1143. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2021-326920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen T., Zhu J., Wang Y. H. RNF216 mediates neuronal injury following experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage through the Arc/Arg3.1-AMPAR pathway. The FASEB Journal . 2020;34(11):15080–15092. doi: 10.1096/fj.201903151RRRR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu G. J., Tao T., Zhang X. S., et al. Resolvin d1 attenuates innate immune reactions in experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage rat model. Molecular Neurobiology . 2021;58(5):1963–1977. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-02237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu Y., Zhang X. S., Zhou X. M., et al. Peroxiredoxin 1/2 protects brain against H2O2-induced apoptosis after subarachnoid hemorrhage. The FASEB Journal . 2019;33(2):3051–3062. doi: 10.1096/fj.201801150R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macdonald R. L. Origins of the concept of vasospasm. Stroke . 2016;47(1):e11–e15. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korja M., Kaprio J. Controversies in epidemiology of intracranial aneurysms and SAH. Nature Reviews. Neurology . 2016;12(1):50–55. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lan X., Han X., Li Q., et al. Pinocembrin protects hemorrhagic brain primarily by inhibiting toll-like receptor 4 and reducing M1 phenotype microglia. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity . 2017;61:326–339. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kong L. L., Gao L., Wang K. X., et al. Pinocembrin attenuates hemorrhagic transformation after delayed t-PA treatment in thromboembolic stroke rats by regulating endogenous metabolites. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica . 2021;42(8):1223–1234. doi: 10.1038/s41401-021-00664-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brasil F. B., de Almeida F. J. S., Luckachaki M. D., Dall'Oglio E. L., de Oliveira M. R. Pinocembrin pretreatment counteracts the chlorpyrifos-induced HO-1 downregulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation in the SH-SY5Y cells. Metabolic Brain Disease . 2021;36(8):2377–2391. doi: 10.1007/s11011-021-00803-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang W., Zhang H., Lee D. H., et al. Using functional and molecular MRI techniques to detect neuroinflammation and neuroprotection after traumatic brain injury. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity . 2017;64:344–353. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tao J., Shen C., Sun Y., Chen W., Yan G. Neuroprotective effects of pinocembrin on ischemia/reperfusion-induced brain injury by inhibiting autophagy. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy . 2018;106:1003–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma Y., Li L., Kong L., et al. Pinocembrin protects blood-brain barrier function and expands the therapeutic time window for tissue-type plasminogen activator treatment in a rat thromboembolic stroke model. BioMed Research International . 2018;2018:13. doi: 10.1155/2018/8943210.8943210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X. S., Lu Y., Li W., et al. Cerebroprotection by dioscin after experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome through SIRT1-dependent pathway. British Journal of Pharmacology . 2021;178(18):3648–3666. doi: 10.1111/bph.15507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang X. S., Lu Y., Tao T., et al. Fucoxanthin mitigates subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced oxidative damage via sirtuin 1-dependent pathway. Molecular Neurobiology . 2020;57(12):5286–5298. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-02095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu W., Yan J., Ocak U., et al. Melanocortin 1 receptor attenuates early brain injury following subarachnoid hemorrhage by controlling mitochondrial metabolism via AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1alpha pathway in rats. Theranostics . 2021;11(2):522–539. doi: 10.7150/thno.49426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang F., Wang S., Gan L., et al. Protective effects and mechanisms of sirtuins in the nervous system. Progress in Neurobiology . 2011;95(3):373–395. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X. S., Wu Q., Wu L. Y., et al. Sirtuin 1 activation protects against early brain injury after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Cell Death & Disease . 2016;7(10, article e2416) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao P., Chen Q., Shi C., Pei M., Wang L., Gong Z. Pinocembrin ameliorates acute liver failure via activating the Sirt1/PPAR α pathway in vitro and in vivo. European Journal of Pharmacology . 2022;915, article 174610 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo W. W., Wang X., Chen X. Q., et al. Flavonones from Penthorum chinense ameliorate hepatic steatosis by activating the SIRT1/AMPK pathway in HepG2 cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2018;19(9):p. 2555. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilkenny C., Browne W., Cuthill I. C., Emerson M., Altman D. G. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the arrive guidelines. British Journal of Pharmacology . 2010;160(7):1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X., Wu Q., Lu Y., et al. Cerebroprotection by salvianolic acid b after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage occurs via Nrf2- and SIRT1-dependent pathways. Free Radical Biology & Medicine . 2018;124:504–516. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong L. J., Wang X. Y., Gu W. Y., Wu X. Pinocembrin ameliorates intermittent hypoxia-induced neuroinflammation through BNIP3-dependent mitophagy in a murine model of sleep apnea. Journal of Neuroinflammation . 2020;17(1):p. 337. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-02014-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X., Wu Q., Zhang Q., et al. Resveratrol attenuates early brain injury after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage via inhibition of nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Frontiers in Neuroscience . 2017;11:p. 611. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia D. Y., Yuan J. L., Jiang X. C., et al. SIRT1 promotes M2 microglia polarization via reducing ROS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome signaling after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Frontiers in Immunology . 2021;12, article 770744 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.770744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander S. P. H., Roberts R. E., Broughton B. R. S., et al. Goals and practicalities of immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry: a guide for submission to the British Journal of Pharmacology. British Journal of Pharmacology . 2018;175(3):407–411. doi: 10.1111/bph.14112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X. S., Lu Y., Li W., et al. Astaxanthin ameliorates oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis via SIRT1/NRF2/Prx2/ASK1/p38 after traumatic brain injury in mice. British Journal of Pharmacology . 2021;178(5):1114–1132. doi: 10.1111/bph.15346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugawara T., Ayer R., Jadhav V., Zhang J. H. A new grading system evaluating bleeding scale in filament perforation subarachnoid hemorrhage rat model. Journal of Neuroscience Methods . 2008;167(2):327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X., Lu Y., Wu Q., et al. Astaxanthin mitigates subarachnoid hemorrhage injury primarily by increasing sirtuin 1 and inhibiting the toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway. The FASEB Journal . 2019;33(1):722–737. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800642RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tao T., Liu G. J., Shi X., et al. DHEA attenuates microglial activation via induction of jmjd3 in experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage. Journal of Neuroinflammation . 2019;16(1):p. 243. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1641-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng H., Fu X., Cai J., et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps may be a potential target for treating early brain injury in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Translational Stroke Research . 2022;13(1):112–131. doi: 10.1007/s12975-021-00909-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang Y., Guo Y., Huang L., et al. Kisspeptin-54 attenuates oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis in early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats via GPR54/ARRB2/AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway. Free Radical Biology & Medicine . 2021;171:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao L., Shi H., Sherchan P., et al. Inhibition of lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 attenuates neuroinflammation via PGE2/EP2/NOX2 signalling and improves the outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage in mice. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity . 2021;91:615–626. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Z. H., Liu J. Q., Hu C. D., et al. Luteolin confers cerebroprotection after subarachnoid hemorrhage by suppression of NLPR3 inflammasome activation through Nrf2-dependent pathway. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity . 2021;2021:18. doi: 10.1155/2021/5838101.5838101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu F., Liu Z., Li G., et al. Inflammation and oxidative stress: potential targets for improving prognosis after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience . 2021;15, article 739506 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.739506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menezes da Silveira C. C. S., Luz D. A., da Silva C. C. S., et al. Propolis: a useful agent on psychiatric and neurological disorders? A focus on CAPE and pinocembrin components. Medicinal Research Reviews . 2021;41(2):1195–1215. doi: 10.1002/med.21757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hwang J. S., Kim E., Hur J., Yoon T. J., Seo H. G. Ring finger protein 219 regulates inflammatory responses by stabilizing sirtuin 1. British Journal of Pharmacology . 2020;177(20):4601–4614. doi: 10.1111/bph.15060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bendale D. S., Karpe P. A., Chhabra R., Shete S. P., Shah H., Tikoo K. 17-β Oestradiol prevents cardiovascular dysfunction in post-menopausal metabolic syndrome by affecting SIRT1/AMPK/H3 acetylation. British Journal of Pharmacology . 2013;170(4):779–795. doi: 10.1111/bph.12290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen X., Pan Z., Fang Z., et al. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid attenuates traumatic brain injury-induced neuronal apoptosis by inducing autophagy through the upregulation of SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of beclin-1. Journal of Neuroinflammation . 2018;15(1):p. 310. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1345-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vellimana A. K., Aum D. J., Diwan D., et al. SIRT1 mediates hypoxic preconditioning induced attenuation of neurovascular dysfunction following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Experimental Neurology . 2020;334, article 113484 doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vellimana A. K., Diwan D., Clarke J., Gidday J. M., Zipfel G. J. SIRT1 activation: a potential strategy for harnessing endogenous protection against delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery . 2018;65(CN_supplement 1):1–5. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyy201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diwan D., Vellimana A. K., Aum D. J., et al. Sirtuin 1 mediates protection against delayed cerebral ischemia in subarachnoid hemorrhage in response to hypoxic postconditioning. Journal of the American Heart Association . 2021;10(20, article e021113) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.021113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan B., Zhao X. D., Shen J. D., et al. Activation of SIRT1 alleviates ferroptosis in the early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity . 2022;2022:19. doi: 10.1155/2022/9069825.9069825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu L., Mo W., Feng J., et al. Astaxanthin attenuates hepatic damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in non- alcoholic fatty liver disease by up-regulating the FGF21/PGC-1α pathway. British Journal of Pharmacology . 2020;177(16):3760–3777. doi: 10.1111/bph.15099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qin X., Jiang M., Zhao Y., et al. Berberine protects against diabetic kidney disease via promoting PGC-1alpha-regulated mitochondrial energy homeostasis. British Journal of Pharmacology . 2020;177:3646–3661. doi: 10.1111/bph.14935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li F., Wang X., Deng Z., Zhang X., Gao P., Liu H. Dexmedetomidine reduces oxidative stress and provides neuroprotection in a model of traumatic brain injury via the PGC-1α signaling pathway. Neuropeptides . 2018;72:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie W., Zhu T., Zhou P., et al. Notoginseng leaf triterpenes ameliorates OGD/R-induced neuronal injury via SIRT1/2/3-Foxo3a-MnSOD/PGC-1alpha signaling pathways mediated by the NAMPT-NAD pathway. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity . 2020;2020:15. doi: 10.1155/2020/7308386.7308386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rius-Perez S., Torres-Cuevas I., Millan I., Ortega A. L., Perez S. PGC-1α, inflammation, and oxidative stress: an integrative view in metabolism. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity . 2020;2020:20. doi: 10.1155/2020/1452696.1452696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao L., Liu H., Yue L., et al. Melatonin attenuates early brain injury via the melatonin receptor/Sirt1/NF-κB signaling pathway following subarachnoid hemorrhage in mice. Molecular Neurobiology . 2017;54(3):1612–1621. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9776-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lucke-Wold B. P., Logsdon A. F., Manoranjan B., et al. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and neuroinflammation: a comprehensive review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2016;17(4):p. 497. doi: 10.3390/ijms17040497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Oliveira Manoel A. L., Macdonald R. L. Neuroinflammation as a target for intervention in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Frontiers in Neurology . 2018;9:p. 292. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dagistan Y., Kilinc E., Balci C. N. Cervical sympathectomy modulates the neurogenic inflammatory neuropeptides following experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Brain Research . 2019;1722, article 146366 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.146366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: animal groups and mortality rates. Supplementary Table 2: the antibodies used in the study. Supplementary Figure 1: schematic illustration of experimental design. Supplementary Figure 2: the graphic abstract. Pinocembrin attenuated free radical insults, reduced inflammatory injury, and improved neuronal survival via the activation of SIRT1-dependent pathway after SAH.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used in this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.