Summary

Electrolysis at intermediate temperatures (100–600°C) is promising because high reaction rates and high product selectivity can be achieved simultaneously during CO2 reduction. However, intermediate temperature electrolysis has rarely been reported owing to electrolyte limitations. Here, solid acid electrolysis cells (SAECs) were adopted for electrochemically reducing CO2. Carbon monoxide, methane, methanol, ethane, ethylene, ethanol, acetaldehyde and propylene were produced from CO2 and steam, using Cu-containing composite cathodes at 220°C and atmospheric pressure. The results demonstrate the potential of SAECs for producing valuable chemical feedstocks. At the SAEC cathode, CO2 was electrochemically reduced by protons and electrons. The product selectivity and reaction rate were considerably different from those of thermochemical reactions with gaseous hydrogen. Based on the differences, plausible reaction pathways were proposed.

Subject areas: Chemistry, Electrochemistry, Chemical Engineering, Process Engineering

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Solid acid electrolysis cells were used to electrochemically reduce CO2

-

•

CsH2PO4/SiP2O7 electrolyte and Cu-based composite cathodes were employed

-

•

CO, CH4, CH3OH, C2H6, C2H4, C2H5OH, CH3CHO, and C3H6 were produced at 220°C

-

•

Plausible H+/e−-based mechanisms were proposed for electrochemical CO2 reduction

Chemistry; Electrochemistry; Chemical Engineering; Process Engineering

Introduction

The electrochemical synthesis of valuable chemical feedstocks from carbon dioxide (CO2) and water has recently attracted considerable attention. Such technologies can contribute not only to CO2 utilization but also to decreasing the power load fluctuation observed with renewable energy. The major electrolysis cells operate at either low temperature (< 100°C) or high temperature (> 600°C). Low temperature cells typically utilize ion-conducting polymer membranes and aqueous electrolytes. Various chemicals can be synthesized depending on the choice of cathode material (Lu and Jiao, 2016). Major products include carbon monoxide (CO), formate (formic acid), formaldehyde, methanol, methane, and ethylene (Merino-Garcia et al., 2016). Because low temperature cells can exhibit sluggish CO2 diffusion in aqueous catholytes (Lu and Jiao, 2016), recent research has focused on utilizing gas diffusion electrodes to enhance current density (Higgins et al., 2019; Weekes et al., 2018). High temperature cells are fabricated based on ion-conducting ceramic materials and are operable at high current densities (ca. 1 A cm−2) (Küngas, 2020; Song et al., 2019). However, the products are limited to CO or syngas. The production of hydrocarbons and oxygenates (alcohols, aldehydes, acids, etc.) are thermodynamically hindered at high temperatures (Fujiwara et al., 2020). Accordingly, the direct electrochemical production of hydrocarbons and oxygenates at high rates remains a challenge.

A potential solution to this problem is the development of solid acid electrolysis cells (SAECs)—an emerging technology based on solid acid fuel cells (Goñi-Urtiaga et al., 2012; Haile et al., 2007; Otomo et al., 2005; Qing et al., 2014). Proton-conducting solid acids are employed as electrolytes, and the cells are operated at intermediate temperatures in the range 150–250°C, which is favorable for catalytically synthesizing hydrocarbons and oxygenates (Din et al., 2019; Rönsch et al., 2016). Gaseous CO2 can be introduced to the cathode, leading to high current densities. The electrolysis heat should be abundant because most global waste heat is released below 300°C (Firth et al., 2019; Forman et al., 2016). SAECs have recently been applied to various electrochemical reactions including steam electrolysis (Fujiwara et al., 2021; Navarrete et al., 2019; Prag, 2014), ammonia synthesis (Imamura and Kubota, 2018; Kishira et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2021), ammonia-derived hydrogen production (Lim et al., 2020), and partial ethane oxidation (Honda et al., 2020). However, only three reports are available in the literature for CO2 electrolysis (Christensen et al., 2020; Kubota et al., 2022; Kubota and Okumura, 2021), and all the reports are about methane production. Therefore, SAECs suitable for electrochemically synthesizing other hydrocarbons and oxygenates should be developed.

In the present work, CO2 was electrolyzed using SAECs at 220°C and atmospheric pressure. A solid phosphate composite (CsH2PO4/SiP2O7) was used as the electrolyte. Physical mixtures of metal powders (Cu, Cu–Ru, or Cu–Pd; 5 wt.% noble metal) and oxide powders (ZrO2 or SiO2) were applied as cathodes. The metal particles could interconnect, thereby forming electron-conducting pathways without requiring carbonaceous additives. Cu-based electrodes are widely used in low temperature electrolysis to synthesize various C1–C3 hydrocarbons and oxygenates (Albo and Irabien, 2016; Lv et al., 2018; Manthiram et al., 2014; Rahaman et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). Furthermore, Cu and ZrO2 are often combined as heterogeneous catalysts to reduce CO2 to methanol (Din et al., 2019; Tada et al., 2018a,2018b). Cu–Ru and Cu–Pd powders were investigated to determine whether noble metal additives enhanced CO2 reduction reactions (CO2RRs). Figure 1 shows an overview of CO2 electrolysis. During the cell operation, part of the electrolyte became viscous and migrated into the porous cathode composite. The resultant cathode structure enabled the formation of different electrochemical reaction pathways to produce various hydrocarbons and oxygenates.

Figure 1.

Overview of SAEC developed for CO2 electrolysis

CO2 is electrochemically reduced at the SAEC cathode by protons and electrons under an applied current. The reaction produces various gases such as CO, methane, methanol, ethane, ethylene, ethanol, acetaldehyde, and propylene.

Results and discussion

Characterization of cathode materials

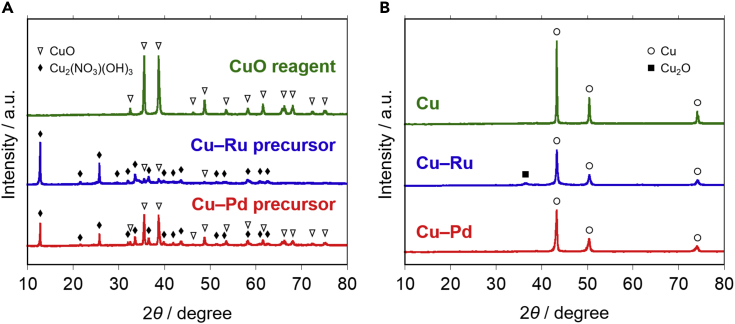

Cu-based metal powders and their precursors were measured using an X-ray diffractometer. Figure 2A shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the CuO reagent and the Cu–Ru and Cu–Pd powder precursors. In the XRD patterns of the precursors, peaks were attributed to the CuO and Cu2(NO3)(OH)3 phases. Figure 2B shows the XRD patterns of the reduced materials. In all the patterns, peaks corresponding to the Cu metal phase were observed. The positions of the Cu metal peaks were not shifted in the Cu–Ru and Cu–Pd XRD patterns. Peaks related to metallic Ru and Pd and their derivatives did not appear. These results suggest that neither Ru nor Pd atoms had dissolved in the Cu phase but existed as small crystals undetectable by XRD measurements. Only the XRD pattern of the Cu–Ru powder exhibited a small peak attributable to the Cu2O phase. The Cu–Ru powder was prepared by reducing the precursor under hydrogen flowing at 330°C for 1 h. Figure S1A shows the temperature programmed reduction (TPR) profile of the Cu–Ru precursor. The positive peak corresponded to the decomposition and reduction of the precursor, and the negative signals were ascribed to the desorption of hydrogen which had adsorbed on the Cu–Ru metal surface. This indicates that the precursor can be fully reduced at 330°C. Thus, the Cu2O phase found in Figure 2B was attributed to the surface oxide layer, which was formed after the reduction because of the exposure to air. Figure S1B shows the TPR profile of the Cu–Ru metal powder. The positive peak indicates that the metal powder had been partially oxidized and the oxide phase was removed by the reduction treatment. Based on this characterization result, we pre-reduced the SAEC cathodes at 220°C before conducting CO2 electrolysis.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of cathode materials

(A) Patterns of CuO reagent, Cu–Ru precursor, and Cu–Pd precursor.

(B) Patterns of Cu, Cu–Ru, and Cu–Pd reduced metal powders.

Figure S2 shows the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger electron spectroscopy (AES) results of the Cu, Cu–Ru, and Cu–Pd powders. Existence of Cu metal in all samples was confirmed by Cu 2p3/2 XPS peaks (932.5 eV (deCrescenzi et al., 1986), Figure S2B) and Cu L3M45M45 AES peaks (918.9 eV for the main peak (Antonides et al., 1977; deCrescenzi et al., 1986), Figure S2C). Ru 3d3/2 and 3d5/2 XPS peaks were found in the Cu–Ru spectrum (Figure S2A) at 284.1 eV and 279.9 eV, respectively (Morgan, 2015), indicating the presence of Ru metal. The Pd 3d3/2 XPS peak (340.9 eV (Liu et al., 1999,2022,2021), Figure S2C) shows that the Cu–Pd powder contained Pd metal.

The morphology of the cathode material powders was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As shown in Figure 3, the secondary Cu, Cu–Ru, and Cu–Pd particles consisted of primary particles ranging from ca. 100 nm for Cu–Ru to ca. 500 nm for Cu and Cu–Pd. The ZrO2 secondary particles were relatively large (10–100 μm), and each secondary particle was composed of minute primary particles not clearly observable by SEM (probably ca. 10 nm). The SiO2 reagent consisted of small particles (< 50 nm). Particle size distribution of the metal powders was examined using the SEM images. The sizes of more than 350 secondary particles were measured for each powder. Figure S3 shows the histograms and the corresponding Gaussian distribution curves. The average size of the secondary Cu, Cu–Ru, and Cu–Pd particles were 4.6, 6.3, and 5.6 μm, respectively. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was also performed. Figure S4 shows the SEM–EDX results of Cu, Cu–Ru, and Cu–Pd powders. The elemental mappings revealed that the distribution of Ru and Pd in Cu–Ru and Cu–Pd particles, respectively, was almost identical to that of Cu, suggesting that the noble metals were not segregated as large crystals.

Figure 3.

Morphology of cathode material powders

SEM images of (A) Cu, (B) Cu–Ru, and (C) Cu–Pd powders and (D) ZrO2 and (E) SiO2 reagents.

CO2 electrolysis performance of SAECs

SAECs can produce hydrogen while exhibiting Faraday efficiencies (FEs) of approximately 90% in the steam electrolysis mode at 220°C (Figure S5). No carbon-containing products were observed, indicating that the carbon paper adjacent to the cathode does not decompose under the examined polarization conditions. CO2 was electrolyzed with different cathodes at 220°C. Under open circuit conditions, no products were detected. By applying a constant current load of 50 mA cm−2, several carbon-containing species were produced besides hydrogen: CO, methane, methanol, ethane, ethylene, ethanol, acetaldehyde, and propylene. Acetaldehyde was detected only with the (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of the production of methanol, ethane, ethylene, ethanol, acetaldehyde, and propylene in CO2 electrolysis using SAECs. The results indicate that novel electrochemical reactions had occurred. Figure S6A shows an overview of the FEs, and Figure S6B details the products formed other than hydrogen and CO. The total FEs were in the range 40–65%, which can be attributed to the products reoxidizing to H2O and CO2 owing to gas crossover. Because the cathode feed gas was not humidified, the electrolyte may have been partially dehydrated, thereby decreasing the gas tightness.

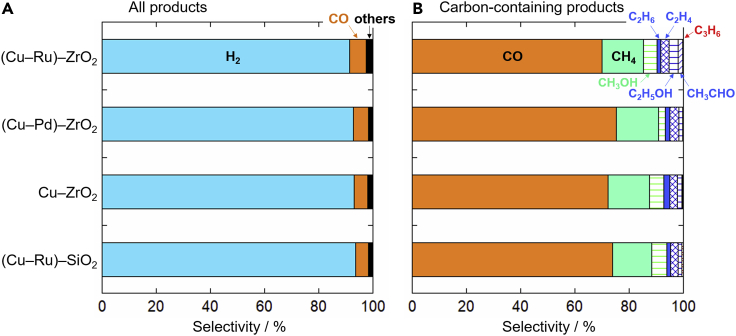

Figure 4A shows the product selectivity, which reflects the competition between the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and the CO2RR. The hydrogen selectivity was almost the same for all the cathodes. The hydrogen selectivities higher than 90% indicate that most of the protons and electrons supplied to the cathodes were used for the HER. Figure 4B shows the selectivity among the carbon-containing products (CO, hydrocarbons, and oxygenates). The (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode exhibited the highest selectivity for multicarbon products, whereas the (Cu–Pd)–ZrO2 cathode exhibited the highest CO selectivity. These results can be ascribed to the properties of the noble metal additives. The details will be discussed later with a focus on the binding energy of surface reaction intermediates.

Figure 4.

Product selectivities recorded using different cathodes

(A) Selectivities among all products.

(B) Selectivities among carbon-containing products. A cathode inlet gas mixture of CO2 and N2 was used, with a flow rate of 5 mL min−1 per gas. The temperature was 220°C, and the current density was fixed at 50 mA cm−2 (H+/CO2 = 0.12).

The CO2RR performance of the (Cu–Ru)–SiO2 cathode was slightly inferior to those of the ZrO2-containing cathodes, yet still comparable (Figure 4), suggesting that the oxide phase had negligible impact on the CO2RR. Therefore, CO2 activation on the oxide surface may not be an essential CO2RR step in this study.

Thermocatalytic activity of the cathode composites

The thermocatalytic activity of the cathode composites was tested using a fixed-bed flow reactor. Figure 5 shows the catalytic activities measured for the metal–oxide composites [Cu–ZrO2, (Cu–Pd)–ZrO2, and (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2] at atmospheric pressure and different temperatures. Although the (Cu–Ru)–SiO2 composite was also tested, no products were detected under the examined conditions. The basicity of ZrO2 was necessary to facilitate CO2 activation. CO and methanol were produced using the Cu–ZrO2, (Cu–Pd)–ZrO2, and (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 composites (Figures 5A, 5B, and 5C1, respectively). CO and methanol production rates decreased in the order (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 > (Cu–Pd)–ZrO2 > Cu–ZrO2. The increased production rates recorded with noble-metal-modified composites can be explained by increased CO2 conversion and methanol selectivity. The roles of the noble metals are discussed below. When (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 was used, traces of methane and ethane were also detected (Figure 5C2), which was ascribed to the Ru activity. Ru is known to be active for CO2 methanation (Nagase et al., 2020; Tada and Kikuchi, 2015). None of the cathodes thermocatalytically synthesized ethylene, ethanol, acetaldehyde, or propylene.

Figure 5.

Thermocatalytic activities measured for various metal–oxide composites at atmospheric pressure and different temperatures

(A) Cu–ZrO2, (B) (Cu–Pd)–ZrO2, and (C1) (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 composites. (C2) Magnified plot of (C1) for methane and ethane. The feed gas comprised CO2/H2/N2 flowing at 4/12/4 mL min−1, respectively (H2/CO2 = 3).

Figure S7 shows CO2 conversion rates and methanol selectivities. Adding noble metals (Ru and Pd) to Cu enhanced both the CO2 conversion and methanol selectivity. The increased CO2 conversion may be attributed to hydrogen spillover. Hydrogen adsorbed on Ru or Pd surfaces can migrate to adjacent particles, which can facilitate the supply of hydrogen to the main reaction sites (i.e., the boundary between Cu and ZrO2) to promote CO2 conversion. According to the literature (Tada et al., 2018a,2018b), CO2 hydrogenation with Cu/ZrO2 catalysts is a successive reaction of the methanol formation from CO2 and the methanol decomposition to CO. Therefore, methanol decomposition must be suppressed to achieve high methanol selectivity. In the present experiments, methanol formation was enhanced by adding noble metals. The noble metals did not promote methanol decomposition as much as methanol formation, which could explain the increased methanol selectivity. (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 exhibited higher catalytic activity than (Cu–Pd)–ZrO2. The difference between the catalytic activities may be related to the metal particle morphology. As shown in Figure 3, the Cu–Ru powder primary particles were smaller than the Cu–Pd powder ones. Thus, (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 could have exhibited more metal–ZrO2 interparticle contacts. Furthermore, the noble metals may have altered the electronic state of the adjacent Cu atoms, thereby leading to different catalytic activities.

Table S1 lists the catalytic activities measured for the different cathode materials at a low H/CO2 ratio of 0.1. CO and methanol were produced even when the hydrogen partial pressure was low. No other products were detected. The catalytic activity decreased in the order (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 > (Cu–Pd)–ZrO2 > Cu–ZrO2 > (Cu–Ru)–SiO2, which is the same order as the counterpart catalytic activities measured when the feed gas was composed of H2/CO2 = 3.

Comparison of electrochemical and thermochemical CO2 hydrogenation

The proton and hydrogen gas reactivities were compared using the SAEC setup. The same number of H atoms was supplied to the (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode as protons or hydrogen gas molecules. When gaseous hydrogen was supplied with CO2 to the cathode under open-circuit conditions (experimental conditions #1 and #3 in Table S2), no carbon-containing products were detected, being contradictory to the thermocatalytic activity test results described above. This was possibly because of the short gas contact time in the SAEC setup. In addition, the acidic electrolyte material may have decreased the thermocatalytic activity of the (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 composite. In contrast, when constant current densities of 50 and 25 mA cm−2 were applied to the cell (experimental conditions #2 and #4 in Table S2, respectively), hydrogen, CO, methane, methanol, ethane, and ethylene were detected in the cathode outlet gas. The difference between the reactivities and product selectivities in the electrochemical and thermocatalytic systems suggests that the systems exhibited different reaction pathways.

Figure 6 compares the methanol production rates measured under the different experimental conditions listed in Table S2. The red diamonds indicate the methanol production rates measured in thermochemical reactions under the conditions #1 and #3, whereas the black circles show the rates measured in electrochemical reactions under the conditions #2 and #4. The thermochemical rates (red diamonds) were zero regardless of the number of supplied H atoms. The blue squares indicate the theoretical methanol production rates calculated based on thermodynamic equilibrium. CO2 and gaseous H2 were considered as the reactants, and the following equilibria were calculated:

| (Equation 1) |

| (Equation 2) |

| (Equation 3) |

Figure 6.

Comparison of methanol production rates measured using (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode at 220°C

[circles] Experimental data recorded at constant current densities (#2 and #4 in Table S2). The cathode feed gas was a mixture consisting of CO2/inert gas flowing at 8/12 mL min−1, respectively. [diamonds] Experimental data obtained under open-circuit conditions with gaseous hydrogen in the cathode feed (#1 and #3 in Table S2). The cathode gas comprised CO2/inert gas/H2 flowing at 8/12/x mL min−1, respectively, and x was determined so that the number of supplied H atoms was the same as in the electrochemical tests. [triangles] Theoretical methanol production rates calculated assuming thermodynamic equilibrium without CO in the equilibrium gas mixture. [squares] Theoretical methanol production rates calculated assuming thermodynamic equilibrium with CO in the equilibrium gas mixture.

The calculation corresponds to the situation where all the above thermochemical reactions reach the equilibrium. The resultant low methanol production rates (< 1.0×10−13 mol s−1 cm−2) indicate that methanol production was not thermodynamically favored. The green triangles indicate the theoretical methanol production rates calculated by excluding CO from the equilibrium gas compositions, that is, considering only Equation 1. These rates correspond to methanol synthesized thermocatalytically from CO2 and H2 without forming CO wherein methanol decomposition is perfectly suppressed. Despite the ideal conditions, the calculated rates were lower than the corresponding measured CO2 electrolysis rates (black circles). If reactions in the SAEC cathode under polarized conditions had proceeded by the serial combination of the electrochemical hydrogen evolution (2H+ + 2e− → H2) and the thermochemical CO2 hydrogenation (Equations 1, 2, and 3), the methanol production rates (black circles) should have been lower than the calculated values (green triangles). However, that was not the case. This means that a certain part of the protons and electrons did not form H2 but directly reduced CO2 or CO2-derived intermediate species to form methanol. Such an electrochemical reaction can be nominally expressed as Equation 4.

| (Equation 4) |

The reaction of Equation 4 is driven by the electrical energy. In other words, the required energy to proceed with the reaction is supplied externally. Thus, the reaction rate is not limited by the thermochemical equilibrium of CO2 hydrogenation (Equations 1, 2, and 3).

SEM observation

Figure S8 shows cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the electrolyte and the (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode before and after the galvanostatic CO2 electrolysis test at 50 mA cm−2 and 220°C. Grains smaller than 1 μm were observed in the electrolyte before the test (Figure S8a1). After the test, a smooth structure comprising ∼10-μm grains appeared (Figure S8a2). These grains are likely to be CsH2PO4 or CsH5(PO4)2. CsH5(PO4)2 can be formed by the chemical reaction of CsH2PO4 and SiP2O7, and exists as liquid at 220°C (Fujiwara et al., 2021; Matsui et al., 2005). It is reasonable that the molten CsH5(PO4)2 was cooled and solidified after the test to form the smooth structure in Figure S8a2. Before the electrolysis test, 100–500-nm grains were observed in the cathode (Figure S8b1). After the test, the grains were covered by a smooth layer (Figure S8b2), which can be attributed to the migrated electrolyte. The hypothesis that part of the electrolyte had migrated to the cathode layer is supported by the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) measurements. Figure 7 shows cross-sectional SEM images of different cathodes and corresponding EDX mappings. The cathode location can be identified by the Cu and noble metal distributions. Before the test, Cs was hardly detectable in the (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode (Figure 7A). In contrast, Cs was detected in the cathode layer after the test (Figure 7B). The (Cu–Pd)–ZrO2, Cu–ZrO2, and (Cu–Ru)–SiO2 cathodes (Figures 7C–7E, respectively) all exhibited the same trend, indicating that the Cs-containing electrolyte materials had migrated to the cathode during the electrolysis tests. The migrated electrolyte might have directly supplied protons to the reaction sites during the cell operation. We consider that the migration was mainly caused by the capillary action. According to the cross-sectional SEM image of the as-prepared (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode (Figure S8b1), the cathode material particles were closely packed. The secondary particles of Cu–Ru (ca. 6.3 μm) were crushed into primary particles (ca. 100 nm). The size of pores in the as-prepared (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode was assumed to be ca. 100 nm or smaller. Such small pores induced the capillary action, leading to the migration of molten CsH5(PO4)2. It is also possible that CsH5(PO4)2 and CsH2PO4 were dissolved in condensed water in the cathode pores. Because the oxides in cathodes (ZrO2 and SiO2) were hydrophilic, steam can be condensed and retained in the cathode small pores. Steam was supplied to the cathode during the cell pretreatment and was also generated at the cathode by CO2 electrolysis reactions. The feeble EDX signals of Cu, Ru, and Pd found in the electrolyte layers of the tested cells (Figures 7B–7E) can be attributed to the noise of the measurements, but it might be also possible that the cathode metal particles inversely migrate to the electrolyte layer through the paths of the migrated electrolyte materials.

Figure 7.

SEM–EDX analysis of different cathodes

(A) As-prepared (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode.

(B–E) Cathodes after galvanostatic CO2 electrolysis tests at 50 mA cm−2 and 220°C. Cross-sectional SEM image and corresponding EDX mappings are shown for each cathode.

Reaction pathways

Based on the experimental results, possible reaction pathways were hypothesized by referring to previously reported reaction mechanisms of thermocatalytic CO2 hydrogenation (Álvarez et al., 2017; Fisher and Bell, 1997; Tada and Kikuchi, 2015) and electrochemical CO2 reduction in aqueous electrolytes (Albo et al., 2015; Kortlever et al., 2015; Kuhl et al., 2012; Rahaman et al., 2017). Figure 8 illustrates the plausible pathways of the CO2RR in SAECs. Steps indicated by light-blue arrows are characteristic of electrochemical hydrogenation by protons and electrons. CO2 adsorbed on the Cu-based metal surface can form surface carboxyl groups (∗COOH). Hereafter, an asterisk (∗) is used to indicate surface species. Carboxyl groups are further reduced to form carbonyl species (∗CO). This mechanism has reported in low-temperature CO2 electrolysis systems (Kortlever et al., 2015). CO2 adsorbed on the oxide (ZrO2 or SiO2) surface, on the other hand, is converted into bicarbonate (∗HCO3) and formate (∗HCOO), and the formate is further reduced to form carbonyl or methoxy (∗OCH3) groups. The direct conversion of formate into methoxy groups, which is characteristic of the thermocatalytic CO2-to-methanol reaction with Cu/ZrO2 catalysts (Larmier et al., 2017), should be a minor reaction during CO2 electrolysis. Instead, methoxy groups may be formed mainly by carbonyl hydrogenation. This is supported by the fact that methanol was formed during CO2 electrolysis using the (Cu–Ru)–SiO2 cathode, which showed no thermocatalytic activity (Figure 4). Furthermore, no methane was produced in the Cu–ZrO2 thermocatalytic activity test (Figure 5), meaning that C–O bonds are difficult to thermocatalytically cleave on the Cu surface. However, a considerable amount of methane was produced in the electrolysis tests. C–O cleavage may be accelerated under cathodic polarization conditions because electrons are fed to the cathode. C–C bonds may form from two carbonyl species or CH2 species.

Figure 8.

Plausible reaction pathways in SAEC cathodes

Carbonyl (∗CO) is formed by electrochemical reduction of carboxyl (∗COOH) or formate (∗HCOO). Methoxy (∗OCH3) is formed mainly by carbonyl hydrogenation. C–O cleavage is accelerated under cathodic polarization, leading to methane formation. C–C bonding occurs between two carbonyl or CH2 species.

Effects of noble metals on the electrochemical CO2RR product selectivity

The (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode and the (Cu–Pd)–ZrO2 cathode showed higher multicarbon-species selectivity and CO selectivity, respectively, than the Cu–ZrO2 cathode (Figure 4). The effects of noble metals on the product selectivity can be understood as follows. As illustrated in Figure 8, surface carbonyl species is a key intermediate in the CO2RR of the present study. Thus, the binding energy of the carbonyl should be a good descriptor for the product selectivity, as is the case with low-temperature CO2RR (Feng et al., 2020; Peterson and Nørskov, 2012). In low-temperature CO2 electrolysis studies, Ru coating on Cu nanoparticles facilitated the formation of C2 species (Billy and Co, 2018), and a Pd cathode preferentially produced CO (Hori et al., 1994). Ru and Pd show larger CO binding energy than Cu (Feng et al., 2020; Peterson and Nørskov, 2012; Toyoshima and Somorjai, 1979), so the carbonyl species formed on the noble metals may be more stable than those formed on the Cu metal. In addition, the noble metals have larger electronegativity than Cu, so they may attract electrons of Cu. The electron-poor Cu holds the surface carbonyl species more strongly than the Cu of normal electronic state. When the carbonyl intermediate is stabilized, the carbonyl population increases, leading to the C–C bond formation. Also, stabilization of the carbonyl may restrain the C–O bond cleavage, enhancing the CO production. We consider that the noble metals played the same role in the present CO2RR in SAEC cathodes.

Change in product selectivity over time

Figure 9 shows the time courses of the production rates of hydrogen, CO, and other highly reduced products during CO2 electrolysis with the (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode at a constant current load of 50 mA cm−2. Methanol, ethanol, and acetaldehyde were detected using GC–FID, and three data points are available. Ethanol and acetaldehyde were undetectable in the second and the third measurements. The other products were detected using GC–TCD, and 24 data points are available. The hydrogen production rate remained approximately constant during the galvanostatic cell operation at 50 mA cm−2. However, the production rates of carbon-containing species did not remain constant: the rates increased sharply and then decreased, which can be related to the cathode catalyst surface coverage. Under open-circuit conditions, CO2 molecules are adsorbed on the catalyst surface. Once the current is applied, those molecules may react with protons to form CO or other products. Because hydrogen is evolved more easily than CO2 is hydrogenated, increasingly more reaction sites (e.g., the metal surface or the boundary between metal and oxide) will be used for hydrogen evolution over time. Therefore, the hydrogen species surface coverage will increase, and fewer sites will be available for CO2 adsorption. The decreased surface coverage of CO2-derived species will prevent them from meeting, thereby suppressing C–C bond formation. Figure S9 shows the time courses of the (rC2H6 + rC2H4)/rCH4 ratio for different cathodes, where rC2H6, rC2H4, and rCH4 are the ethane, ethylene, and methane production rates, respectively. For all the tested cathodes, the ratio decreased over time, indicating that C2 species selectivity had declined. The (rC2H6 + rC2H4)/rCH4 ratio decreased moderately for the Cu–ZrO2 cathode compared to the other cathodes, which can be explained by noble-metal-induced hydrogen spillover. When Ru or Pd was used, hydrogen was supplied from the noble metal to the adjacent Cu and oxides, thereby increasing the hydrogen species surface coverage. Because noble metals were absent in the Cu–ZrO2 cathode, the increase in the population of surface hydrogen species was suppressed, and C2 species selectivity was maintained.

Figure 9.

Time courses of hydrogen, CO, methane, methanol, ethane, ethylene, ethanol, acetaldehyde, and propylene production rates for (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode

(A) Overview. (B) Magnified plot without hydrogen. (C) Magnified plot without hydrogen and CO. A constant current load of 50 mA cm−2 was applied (H+/CO2 = 0.12). The cell operation temperature was 220°C.

Conclusions

CO2 was electrolyzed using SAECs at 220°C and atmospheric pressure. Cu–ZrO2, (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2, (Cu–Pd)–ZrO2, and (Cu–Ru)–SiO2 composites were examined for application to cathode materials. At a constant current load of 50 mA cm−2, CO, methane, methanol, ethane, ethylene, ethanol, acetaldehyde, and propylene were produced. Notably, methanol, ethane, ethylene, ethanol, acetaldehyde, and propylene were produced using SAECs for the first time. The various products showed the potential of using SAECs to directly produce valuable chemicals from CO2 and steam. The addition of noble metals to copper in the cathode material affected the CO2RR product selectivity: Ru and Pd enhanced the formation of multicarbon species and CO, respectively. Also, the C2 species selectivity rapidly decreased with the noble-metal-containing cathodes possibly because of the hydrogen spillover. Plausible reaction pathways were presented based on the experimental results. Understanding the reaction pathways will facilitate the strategic design of cathode reaction sites, which should be the key for achieving highly selective CO2RRs in SAECs.

Limitations of the study

Although multiple plausible reaction pathways have been proposed in Figure 8, more information is required to verify the mechanism. The present reactor setup is not suitable for the use of reference electrodes, so the cathode potential could not be measured. The relationship between the cathode potential and the electrochemical reaction characteristics should be investigated by redesigning the reactor and introducing reference electrodes. Application of spectroscopic techniques is also desirable to fully elucidate electrochemical CO2 reduction. Understanding the reaction mechanism will enable cathode reaction sites to be adequately designed to optimize hydrocarbon and oxygenate selectivities. The binding energy of the surface carbonyl species is an important factor to control the selectivity because it affects both the population of the carbonyl and strength of the C–O bond. It is promising to develop cathode materials by focusing on the carbonyl binding energy. Possible strategies include alloying and addition of promoters (Peterson and Nørskov, 2012). The cathode structure is also important. The migrated electrolyte can clog the cathode pores and suppress the gas diffusion, leading to low CO2 conversions. Hydrophobic additives may be effective to control the electrolyte migration.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3) | FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation | CAS# 534-17-8 |

| Phosphoric acid (H3PO4) | Sigma-Aldrich | CAS# 7664-38-2, 85 wt.% in water |

| Silicon dioxide (SiO2) | FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation | CAS# 7631-86-9 |

| Copper(II) oxide (CuO) | FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation | CAS# 1317-38-0 |

| Ruthenium nitrate (Ru(NO3)3) nitric acid solution | Tanaka Kikinzoku Kogyo | CAS# 15825-24-8 |

| Palladium nitrate (Pd(NO3)2) nitric acid solution | Tanaka Kikinzoku Kogyo | CAS# 10102-05-3 |

| Amorphous zirconia (ZrO2) | Daiichi Kigenso Kagaku Kogyo | NND |

| Carbon paper | Toray Industries | TGP-H-120 |

| Platinum mesh | Nilaco Corporation | 100 mesh, 70 μm thick |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Aspen Plus | Aspen Technology | Version 8.8 |

| Other | ||

| Gas chromatograph equipped with a flame-ionization detector | Shimadzu Corporation | GC-2014 |

| Micro-gas chromatograph equipped with a thermal-conductivity detector | Varian | CP-4900 |

| Micro-gas chromatograph equipped with a thermal-conductivity detector | Agilent Technologies | Agilent 490 |

| Potentio-galvanostat | Solartron Analytical | 1287A |

| Frequency response analyzer | Solartron Analytical | 1255B |

| X-ray diffractometer | Rigaku | SmartLab |

| Scanning electron microscope | Hitachi | S-4700 |

| Scanning electron microscope | Hitachi | SU5000 |

| Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy detector | Horiba | Super Xerophy |

| Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy detector | Bruker | XFlash 6–60 |

| X-ray photoelectron spectrometer | JEOL | JPS-9010TR |

| Ar+ etching ion gun | JEOL | XP-HSIG |

| Chemisorption Analyzer | Quantachrome | ChemBET-3000 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and materials should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Ryuji Kikuchi (rkikuchi8@eng.hokudai.ac.jp).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique materials.

Method details

Materials preparation

Electrolyte materials, CsH2PO4 and SiP2O7, were prepared as described in our previous paper (Fujiwara et al., 2021). CsH2PO4 was prepared by dissolving stoichiometric amounts of Cs2CO3 and H3PO4 in distilled water and sequentially drying the solution at 100 and 120°C for 24 and 15 h, respectively. SiP2O7 was synthesized as follows. First, SiO2 and H3PO4 were mixed at a molar ratio of 1:2.5, and the mixture was successively dried at 200, 100, and 120°C for 3, 24, and 24 h, respectively. Finally, the sample was calcined at 700°C for 3 h to obtain SiP2O7. The synthesized materials were physically mixed at a molar ratio of 1:2 to obtain the CsH2PO4/SiP2O7 composite.

Cu powder was prepared by reducing CuO powder at 350°C for 1 h. Cu–M powders (M = Ru or Pd, 5 wt.%) were synthesized from CuO and M(NO3)x nitric acid solutions, respectively. The reagents were mixed and then the water content was evaporated at 80°C. The resultant precursors were pelletized and reduced under hydrogen flowing at 330°C for 1 h. The reduction temperatures were determined by temperature-programmed reduction measurements. Metal–oxide composites were prepared by mixing metal powders (Cu, Cu–Ru, or Cu–Pd) and oxide powders (ZrO2 or SiO2) at a weight ratio of 1:1.

Cell fabrication

Metal–oxide composite powders were pressed in a ⌀10 mm uniaxial die at 20 MPa for 10 min to form a cathode disk. The metal loading was set to 10 mg cm−2. The cathode disk and 0.44 g of electrolyte powder were co-pressed in a ⌀20 mm uniaxial die at 20 MPa for 10 min to form a cell. The cell, the cathode current collector (carbon paper), and the anode (⌀10 mm platinum mesh) were fitted into polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) sheets and were subsequently hot-pressed at 120°C and 6 MPa for 10 min (Figure S10a). PTFE tape was employed to fill the gaps between the cell and the PTFE sheet. The resultant structure was set in a stainless-steel reactor (Figure S10b). The orange and green areas in Figure S10b indicate anode and cathode gas channels, respectively.

Electrochemical reactions

Figure S11 illustrates an overview of the experimental apparatus. Dry or humidified CO2, N2, and H2 gasses can be introduced to the cathode while dry or humidified N2 gas is introduced to the anode. The inlet gases were humidified by bubbling the gases in distilled water. The steam partial pressure was controlled by varying the bubbler temperature. The cathode outlet gas was analyzed using gas chromatographs. First, the gas was analyzed using a gas chromatograph equipped with a flame-ionization detector (GC–FID). Then, the gas was dehumidified in a cold trap and was further analyzed using a micro-gas chromatograph equipped with a thermal-conductivity detector (GC–TCD). GC–FID was used to quantify the methanol, ethanol, and acetaldehyde concentrations, and GC–TCD was used to monitor the concentrations of the other gases (H2, N2, CH4, CO, C2H4, C2H6, and C3H6). Peaks were assigned based on the retention times determined before the electrolysis tests by injecting reagents of possible products. The quantification of each chemical species was done by using N2 as the internal standard. The molar production rate of a certain species k was calculated from the molar flow rate of N2, the concentration of N2, and the concentration of species k.

Figure S12 summarizes the experimental procedure. After the temperature was raised to 220°C, cathodes were reduced for 1 h using a gas mixture of H2/N2/H2O with a flow rate of 25, 10, and 15 mL min−1, respectively. During the electrochemical reactions, the anode gas composition was fixed to H2O/N2, with a flow rate of 15 and 35 mL min−1, respectively. First, the hydrogen-production performance of the cells was evaluated at a constant current load of 50 mA cm−2 by supplying N2 (10 mL min−1) to the cathode. Then, for CO2 electrolysis, the cathode gas was switched to CO2/N2 with a flow rate of 5 mL min−1 per gas. To facilitate CO2 conversion, the cathode gas was not humidified. The cathode outlet gas compositions were analyzed under open-circuit and galvanostatic conditions at 50 mA cm−2.

Calculation of Faraday efficiency and selectivity

The Faraday efficiency of product k (EF,k) was calculated using Equation 5.

| (Equation 5) |

F, rk, i, and S are the Faraday constant, the molar production rate of species k, the current density, and the electrode area, respectively, and nk is the number of electrons used to produce one molecule of species k. The nk values are summarized in Table S3. rk values were obtained based on the gas chromatograph data corresponding to the averaged cathode outlet gas composition 5–20 min after the start of the galvanostatic cell operation.

The product selectivity for species k (Sk) was calculated as follows:

| (Equation 6) |

To calculate the selectivities among all products, nj and rj values of H2, CO, CH4, CH3OH, C2H6, C2H4, C2H5OH, CH3CHO, and C3H6 were considered. The selectivities among carbon-containing products were calculated by excluding H2.

Thermocatalytic activity tests

The thermocatalytic activity of the metal–oxide composites [Cu–ZrO2, (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2, (Cu–Pd)–ZrO2, and (Cu–Ru)–SiO2] was examined at atmospheric pressure. The composites were pelletized into ca. 1.5-mm grains. The pellets (200 mg) were put in a ⌀8 mm quartz tube. The temperature was raised from room temperature (ca. 25°C) to 220°C in a nitrogen atmosphere. The catalyst was reduced using dry hydrogen (i.e., a gas mixture of H2 and N2 with a flow rate of 25 mL min−1 per gas) at 220°C for 30 min to remove the surface oxide layer formed on the metal particles. The catalytic activity was measured using a CO2/H2/N2 gas mixture with a flow rate of 4, 12, and 4 mL min−1, respectively (H2/CO2 = 3). The temperature was changed as follows: 220°C → 230°C → 250°C → 240°C. At each temperature, the outlet gas composition was analyzed. At 250°C, an additional experiment was performed using a feed gas of CO2/(5% H2/Ar)/N2 with a flow rate of 4, 4, and 12 mL min−1, respectively, to determine the catalytic activity at a low H/CO2 ratio (0.1). CO2 conversion () and methanol selectivity () were calculated using Equations 7 and 8, respectively, where Fi,out is the cathode outlet molar flow rate of species i.

| (Equation 7) |

| (Equation 8) |

Comparison of proton and hydrogen gas reactivities

A SAEC with the (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode was used for this experiment. After the same cell pretreatment as described in electrochemical reactions section, the cathode inlet gas composition and current density were both changed based on the conditions listed in Table S2, and the cathode outlet gas was analyzed.

The theoretical methanol production rates were calculated using Aspen Plus software. The equilibrium gas compositions were determined by minimizing the Gibbs-free energy of the gas mixture.

Temperature programmed reduction

The reducibility of the cathode precursors and the metal powders were tested by TPR. Samples were set in a chemisorption analyzer (Quantachrome ChemBET-3000), and 5% H2/Ar gas was introduced. The temperature was raised from the room temperature (ca. 25°C) to 1000°C at a rate of 10°C min−1. The outlet gas was monitored by a thermal conductivity detector.

X-ray diffraction

Cu-based metal powders (Cu, Cu–Ru, and Cu–Pd) and their precursors (CuO, Cu–Ru precursor, and Cu–Pd precursor) were measured using an X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku SmartLab). The samples were exposed to air before the measurements.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

The electronic states of Cu, Pd, and Ru species were examined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (JEOL JPS-9010TR operating with MgKα radiation). The C 1s peak (284.6 eV) was used to correct the binding energies. To remove the surface oxide layer of the sample, we used an Ar+ etching ion gun (JEOL XP-HSIG, 600 V, 12 mA, 60 s).

SEM–EDX measurements

The morphology of the cathode material powders (Cu, Cu–Ru, Cu–Pd, ZrO2, and SiO2) was examined with a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi S-4700). The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analysis of the Cu, Cu–Ru, and Cu–Pd powders was performed with a SEM (Hitachi SU5000) and an EDX detector (Bruker XFlash 6–60).

Cross-sections of the CsH2PO4/SiP2O7 electrolyte and the (Cu–Ru)–ZrO2 cathode before and after the galvanostatic CO2 electrolysis test at 50 mA cm−2 and 220°C were observed with the SEM (Hitachi S-4700). Cross-sections of the (Cu–Pd)–ZrO2, Cu–ZrO2, and (Cu–Ru)–SiO2 cathodes after the CO2 electrolysis tests were also observed. Elemental mappings were recorded with an EDX detector (Horiba Super Xerophy).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Our study does not include statistical analysis or quantification.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number JP20J14232. N.F. acknowledges support from the Materials Education Program for the Future Leaders in Research, Industry, and Technology, The University of Tokyo. S.T. acknowledges support from the Ogasawara Toshiaki Memorial Foundation. The XRD measurement was conducted at Advanced Characterization Nanotechnology Platform of the University of Tokyo, supported by “Nanotechnology Platform” of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. The XPS measurement and a part of the SEM–EDX measurements were supported by Center for Instrumental Analysis, Ibaraki University, Japan.

Author contributions

N.F.: Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, resources, visualization, formal analysis, writing – original draft. S.T.: Methodology, resources, formal analysis, writing – review and editing. R.K.: Supervision, writing – review and editing.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: November 9, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.105381.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

The data generated and analyzed in this study will be shared by the lead contact upon reasonable request.

-

•

This article does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this article is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- Albo J., Alvarez-Guerra M., Castaño P., Irabien A. Towards the electrochemical conversion of carbon dioxide into methanol. Green Chem. 2015;17:2304–2324. doi: 10.1039/C4GC02453B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albo J., Irabien A. Cu2O-loaded gas diffusion electrodes for the continuous electrochemical reduction of CO2 to methanol. J. Catal. 2016;343:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2015.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez A., Bansode A., Urakawa A., Bavykina A.V., Wezendonk T.A., Makkee M., Gascon J., Kapteijn F. Challenges in the greener production of formates/formic acid, methanol, and DME by heterogeneously catalyzed CO2 hydrogenation processes. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:9804–9838. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonides E., Janse E.C., Sawatzky G.A. LMM Auger spectra of Cu, Zn, Ga, and Ge. I. Transition probabilities, term splittings, and effective Coulomb interaction. Phys. Rev. B. 1977;15:1669–1679. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.15.1669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Billy J.T., Co A.C. Reducing the onset potential of CO2 electroreduction on CuRu bimetallic particles. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018;237:911–918. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.06.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen E., Petrushina I.M., Nikiforov A.V., Berg R.W., Bjerrum N.J. CsH2PO4 as electrolyte for the formation of CH4 by electrochemical reduction of CO2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020;167:044511. doi: 10.1149/1945-7111/ab75fa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Crescenzi M., Diociaiuti M., Lozzi L., Picozzi P., Santucci S., Battistoni C., Mattogno G. Size effects on the linewidths of the Auger spectra of Cu clusters. Surf. Sci. 1986;178:282–289. doi: 10.1016/0039-6028(86)90304-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Din I.U., Shaharun M.S., Alotaibi M.A., Alharthi A.I., Naeem A. Recent developments on heterogeneous catalytic CO2 reduction to methanol. J. CO2 Util. 2019;34:20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jcou.2019.05.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., An W., Wang Z., Wang Y., Men Y., Du Y. Electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction on M@Cu(211) bimetallic single-atom surface alloys: mechanism, kinetics, and catalyst screening. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020;8:210–222. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b05183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Firth A., Zhang B., Yang A. Quantification of global waste heat and its environmental effects. Appl. Energy. 2019;235:1314–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.10.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher I.A., Bell A.T. In-situ infrared study of methanol synthesis from H2/CO2 over Cu/SiO2 and Cu/ZrO2/SiO2. J. Catal. 1997;172:222–237. doi: 10.1006/jcat.1997.1870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forman C., Muritala I.K., Pardemann R., Meyer B. Estimating the global waste heat potential. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016;57:1568–1579. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara N., Nagase H., Tada S., Kikuchi R. Hydrogen production by steam electrolysis in solid acid electrolysis cells. ChemSusChem. 2021;14:417–427. doi: 10.1002/cssc.202002281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara N., Tada S., Kikuchi R. Power-to-gas systems utilizing methanation reaction in solid oxide electrolysis cell cathodes: a model-based study. Sustain. Energy Fuels. 2020;4:2691–2706. doi: 10.1039/C9SE00835G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goñi-Urtiaga A., Presvytes D., Scott K. Solid acids as electrolyte materials for proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolysis: Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2012;37:3358–3372. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.09.152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haile S.M., Chisholm C.R.I., Sasaki K., Boysen D.A., Uda T. Solid acid proton conductors: from laboratory curiosities to fuel cell electrolytes. Faraday Discuss. 2007;134:17–39. doi: 10.1039/b604311a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D., Hahn C., Xiang C., Jaramillo T.F., Weber A.Z. Gas-diffusion electrodes for carbon dioxide reduction: a new paradigm. ACS Energy Lett. 2019;4:317–324. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b02035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Honda Y., Fujiwara N., Tada S., Kobayashi Y., Oyama S.T., Kikuchi R. Direct electrochemical synthesis of oxygenates from ethane using phosphate-based electrolysis cells. Chem. Commun. 2020;56:11199–11202. doi: 10.1039/D0CC05111J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori Y., Wakebe H., Tsukamoto T., Koga O. Electrocatalytic process of CO selectivity in electrochemical reduction of CO2 at metal electrodes in aqueous media. Electrochim. Acta. 1994;39:1833–1839. doi: 10.1016/0013-4686(94)85172-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura K., Kubota J. Electrochemical membrane cell for NH3 synthesis from N2 and H2O by electrolysis at 200 to 250 °C using a Ru catalyst, hydrogen-permeable Pd membrane and phosphate-based electrolyte. Sustain. Energy Fuels. 2018;2:1278–1286. doi: 10.1039/c8se00054a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kishira S., Qing G., Suzu S., Kikuchi R., Takagaki A., Oyama S.T. Ammonia synthesis at intermediate temperatures in solid-state electrochemical cells using cesium hydrogen phosphate based electrolytes and noble metal catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42:26843–26854. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.09.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kortlever R., Shen J., Schouten K.J.P., Calle-Vallejo F., Koper M.T.M. Catalysts and reaction pathways for the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:4073–4082. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota J., Okumura T. Methane synthesis from CO2 and H2O with electricity using H-permeable membrane electrochemical cells with Ru catalyst and phosphate electrolyte. Sustain. Energy Fuels. 2021;5:935–940. doi: 10.1039/D0SE01896A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota J., Okumura T., Hayashi R. Methane synthesis from CO2 and H2O using a phosphate-based electrochemical cell at 210–270 °C with oxide-supported Ru catalysts. Sustain. Energy Fuels. 2022;6:1362–1372. doi: 10.1039/D1SE02029C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl K.P., Cave E.R., Abram D.N., Jaramillo T.F. New insights into the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide on metallic copper surfaces. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012;5:7050–7059. doi: 10.1039/c2ee21234j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Küngas R. Review—electrochemical CO2 reduction for CO production: comparison of low- and high-temperature electrolysis technologies. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020;167:044508. doi: 10.1149/1945-7111/ab7099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larmier K., Liao W.-C., Tada S., Lam E., Verel R., Bansode A., Urakawa A., Comas-Vives A., Copéret C. CO2-to-Methanol hydrogenation on zirconia-supported copper nanoparticles: reaction intermediates and the role of the metal-support interface. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017;56:2318–2323. doi: 10.1002/anie.201610166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim D.-K., Plymill A.B., Paik H., Qian X., Zecevic S., Chisholm C.R., Haile S.M. Solid acid electrochemical cell for the production of hydrogen from ammonia. Joule. 2020;4:2338–2347. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2020.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., St Clair T.P., Goodman D.W. An XPS study of the interaction of ultrathin Cu films with Pd(111) J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:8578–8582. doi: 10.1021/jp991843j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Chen W., Wang W., Jiang Y., Cao K. PdZn alloys decorated 3D hierarchical porous carbon networks for highly efficient and stable hydrogen production from aldehyde solution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46:33429–33437. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.07.193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Chen W., Zhang X. Bimetallic Pd–Bi nanocatalysts derived from NaBH4 reduction of BiOCl and Pd2+ and exhibit highly efficient hydrogen production over formaldehyde solution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2022;47:32425–32435. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.07.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q., Jiao F. Electrochemical CO2 reduction: electrocatalyst, reaction mechanism, and process engineering. Nano Energy. 2016;29:439–456. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lv J.-J., Jouny M., Luc W., Zhu W., Zhu J.-J., Jiao F. A highly porous copper electrocatalyst for carbon dioxide reduction. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1803111. doi: 10.1002/adma.201803111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthiram K., Beberwyck B.J., Alivisatos A.P. Enhanced electrochemical methanation of carbon dioxide with a dispersible nanoscale copper catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13319–13325. doi: 10.1021/ja5065284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T., Kukino T., Kikuchi R., Eguchi K. An intermediate temperature proton-conducting electrolyte based on a CsH2PO4/SiP2O7 composite. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 2005;8:A256–A258. doi: 10.1149/1.1883906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merino-Garcia I., Alvarez-Guerra E., Albo J., Irabien A. Electrochemical membrane reactors for the utilisation of carbon dioxide. Chem. Eng. J. 2016;305:104–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2016.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D.J. Resolving ruthenium: XPS studies of common ruthenium materials. Surf. Interface Anal. 2015;47:1072–1079. doi: 10.1002/sia.5852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H., Naito R., Tada S., Kikuchi R., Fujiwara K., Nishijima M., Honma T. Ru nanoparticles supported on amorphous ZrO2 for CO2 methanation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020;10:4522–4531. doi: 10.1039/d0cy00233j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete L., Andrio A., Escolástico S., Moya S., Compañ V., Serra J.M. Protonic conduction of partially-substituted CsH2PO4 and the applicability in electrochemical devices. Membranes. 2019;9:49. doi: 10.3390/membranes9040049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otomo J., Tamaki T., Nishida S., Wang S., Ogura M., Kobayashi T., Wen C.J., Nagamoto H., Takahashi H. Effect of water vapor on proton conduction of cesium dihydrogen phosphate and application to intermediate temperature fuel cells. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2005;35:865–870. doi: 10.1007/s10800-005-4727-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson A.A., Nørskov J.K. Activity descriptors for CO2 electroreduction to methane on transition-metal catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:251–258. doi: 10.1021/jz201461p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prag C.B. Technical University of Denmark; 2014. Intermediate Temperature Steam Electrolysis with Phosphate-Based Electrolytes. [Google Scholar]

- Qing G., Kikuchi R., Takagaki A., Sugawara T., Oyama S.T. CsH5(PO4)2 doped glass membranes for intermediate temperature fuel cells. J. Power Sources. 2014;272:1018–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman M., Dutta A., Zanetti A., Broekmann P. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 into multicarbon alcohols on activated Cu mesh catalysts: an identical location (IL) study. ACS Catal. 2017;7:7946–7956. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b02234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rönsch S., Schneider J., Matthischke S., Schlüter M., Götz M., Lefebvre J., Prabhakaran P., Bajohr S. Review on methanation – from fundamentals to current projects. Fuel. 2016;166:276–296. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2015.10.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Zhang X., Xie K., Wang G., Bao X. High-temperature CO2 electrolysis in solid oxide electrolysis cells: developments, challenges, and prospects. Adv. Mater. 2019;31:1902033. doi: 10.1002/adma.201902033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada S., Katagiri A., Kiyota K., Honma T., Kamei H., Nariyuki A., Uchida S., Satokawa S. Cu species incorporated into amorphous ZrO2 with high activity and selectivity in CO2-to-Methanol hydrogenation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2018;122:5430–5442. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b11284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tada S., Kayamori S., Honma T., Kamei H., Nariyuki A., Kon K., Toyao T., Shimizu K.i., Satokawa S. Design of interfacial sites between Cu and amorphous ZrO2dedicated to CO2-to-Methanol hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 2018;8:7809–7819. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b01396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tada S., Kikuchi R. Mechanistic study and catalyst development for selective carbon monoxide methanation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015;5:3061–3070. doi: 10.1039/c5cy00150a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima I., Somorjai G.A. Heats of chemisorption of O2, H2, CO, CO2, and N2 on polycrystalline and single crystal transition metal surfaces. Catal. Rev. 1979;19:105–159. doi: 10.1080/03602457908065102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Chen Z., Han P., Du Y., Gu Z., Xu X., Zheng G. Single-atomic Cu with multiple oxygen vacancies on ceria for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to CH4. ACS Catal. 2018;8:7113–7119. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b01014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weekes D.M., Salvatore D.A., Reyes A., Huang A., Berlinguette C.P. Electrolytic CO2 reduction in a flow cell. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018;51:910–918. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Tada S., Kikuchi R. Ammonia synthesis using Fe/BZY–RuO2 catalysts and a caesium dihydrogen phosphate-based electrolyte at intermediate temperatures. Mater. Adv. 2021;2:793–803. doi: 10.1039/d0ma00905a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

The data generated and analyzed in this study will be shared by the lead contact upon reasonable request.

-

•

This article does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this article is available from the lead contact upon request.